8

Food in bottles

What they can tell us

Introduction

The art of preserving food dates back millennia. It enabled our ancestors – Indigenous and settlers alike – to take advantage of seasonal surges in production and times of plenty to plan for leaner periods, but it also allowed travellers to take food with them to sustain them on their journeys. By the time non-Indigenous settlers landed on Australian soil, they were well-versed in preserving methods and they brought these cultures and technologies with them. By the early nineteenth century, colonial communities in Australia were regularly supplied with familiar foods from their homelands. These new foodstuffs, introduced from around the world, relied on preservation and so there is a need to understand storage technologies as a critical component of early colonial food and foodways.

Importantly though, by analysing bottles from artefact assemblages closely, we can also understand the complexity of colonial Australians’ food and dining experiences. Food and food experiences were shaped by a range of factors such as ethnicity, socio-economic status, change over time and location. Looking closely at bottle collections helps us to understand the food and food cultures across colonial Australia. In order to interrogate artefact collections fully, however, it is necessary to understand key issues around food preservation, change over time, emerging technologies and other cultural influences such as class and ethnicity. This chapter provides an outline of the range of issues that historical archaeologists should be aware of in order to meaningfully analyse bottle collections and optimise our understanding of food cultures in colonial Australia.

Central to understanding the role of bottles in food and foodways is to understand the importance of food preservation in the past. Food preservation technologies are varied, including smoking, salting, pickling, dehydration and a range of other techniques. Each of these techniques has its own associated range of tools and utensils. This chapter focuses on the use of bottles in food preservation and explores the range of types and uses in colonial Australia.

Colonial Australian dietary patterns ultimately had their roots in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European cuisine and, in particular, traditions of Britain and Ireland. Goody (2019, 263) has argued that the British diet “went straight from medieval barbarity to industrial decadence during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries”. While the reality of this transition was more nuanced and phased than Goody implies, the rapid development of industrial preservation technologies and the role they played in colonisation and expansion of the Empire is undeniable. Critical factors in this transition were improvements in the mechanisation of preserving techniques, marketing and transportation. In Britain, commercially preserved foods did not reach the market until the 1830s due to their high price, but they soon became a critical part of the diet – and remain so to the present. By extension, these products also became an important part of colonial dietary patterns, where the tyranny of distance and a much warmer climate only served to increase their value and necessity.

It is also important to note that colonial Australian assemblages include a range of goods connected to Asian diaspora communities and their trade networks. The diverse range of preservation techniques represented by assemblages associated with Asian, and more specifically Chinese, communities will be explored in some detail below. These goods highlight the diversity of both the colonial Australian community and our food cultures from an early chapter post-colonisation.

Presented here is not a case study of food bottles from selected sites for comparative analysis. Rather, the aim is to provide a background of preserving technologies that contributed to the improved supply, quality and variety of foods available in the colonial market. Furthermore, this chapter gives the reader the tools needed to identify bottle forms and product content, and demonstrates how the interpretation of foodways contributes to identifying patterns in the colonial diet.

Glass and ceramic bottles represent the most durable packaging for many foodstuffs and are the primary commercial packaging found in the archaeological record. Archaeologists meticulously record data on the bottles recovered from excavations. They identify their form and function, manufacturing technologies and physical attributes. In most collections, alcohol bottles (wine, beer, whisky, gin/schnapps and other spirits) and soft drink bottles (aerated water, cordial and mineral water) represent most recovered glass and ceramic bottles. The results of artefact analyses often include beverage preferences, market access and socio-economic factors. However, beyond identifying the original contents of food bottles, little analysis of Australian collections generally addresses the interpretation of the cultural affiliation, lifestyles and dietary patterns of the people who used and discarded these bottles. Providing background on preserving technologies for food in bottles, identification of basic bottle forms and colonial dietary patterns serves as a foundation for archaeologists to build their interpretive analysis of foodways in a colonial setting.

Food storage and preservation in Australia

Refrigeration of foods was not available in Australia until 1839, when the shipment of iceblocks from North America (Canada and the United States) first arrived. This trade of natural ice continued until the 1860s, when James Harrison of Geelong developed a prototype based on an 1834 British design for vapour-compression refrigeration, which he patented in 1856 (Selinger 2013, 20; Roberts n.d., 11). In 1860, he formed The Sydney Ice Company, which brought patented ice to Sydney for the first time (Roberts n.d., 3). While the domestic refrigerator was yet to come, people in metropolitan areas could now have regular visits from the iceman, and ice chests became a fixture in many suburban homes. The first iceboxes were insulated wooden boxes lined with tin or zinc and used to hold iceblocks to keep the food cool (see also Chapter 7). A drip pan collected the meltwater – and had to be emptied daily.

In the absence of widespread refrigeration, colonial Australians needed to rely on a range of preservation techniques – some ancient in origin, while others harnessed the advantages of scientific and technological innovations of the nineteenth century. The preservation of foods has taken many forms over time. Preservation methods include drying, smoking, salting, fermenting, pickling in vinegar, dehydration, canning and freezing. When commercially packaged, evidence of these preservation methods is found within Australian contexts, but their representation at different points in time and in different regions was influenced by a range of factors, including demographics, cultural preference and tradition, and economic and technological developments. This section will briefly outline some of the major developments and influences on food preservation in the colonial period.

Perhaps the richest spread of preservation techniques is found within collections associated with Asian communities in Australia. Preservation methods for Asian foodstuffs in colonial contexts include pickling, drying, smoking, salting, sugaring, steeping and fermentation. All these preserving methods aim to remove the air and create an anaerobic environment for the storage of foods (Drummond and Wilbraham 1994, 313). Drying and smoking, two of the earliest methods, involved removing the moisture from vegetables and meats to limit microbial growth and spoilage (Metheny and Beaudry 2015, 7). Salt was also used as part of most preservation, including drying, smoking, dehydrating and pickling, by drawing the liquid out of food (Shephard 2000, 54). Chinese traditions incorporated elements of Chinese herbal medicines as antimicrobial agents into food preservation methods as well. Most common of these agents are spices – cinnamon, mustard, vanilla, clove and allspice – and some herbs – specifically oregano, rosemary, thyme, sage and basil – which all confer strong antimicrobial activity (Hintz et al. 2015, 1–2).

Many of the innovations in food preservation were also achieved out of the necessities of the times. For example, prior to the development of refrigeration, meat preservation was a major concern. This was true for all people, but the long distances, climate and distribution networks meant that meat preservation was particularly important for travellers, explorers and armed forces on the move in colonial Australia. In the 1840s, the fall in the price of meat from sheep produced a glut of freshly butchered meat in the Australian market. This prompted Sizar Elliot’s rediscovery of tinned meat production, and the market for Australian tinned meats gained much success during the 1860s cattle plague in England (Shephard 2000, 243). Connected to this, commercial packaging of beef extract also began in the late 1840s, with Baron Justus von Liebig’s portable soups. Von Liebig established his company in Uruguay, where vast quantities of Uruguayan and Argentinian beef were a by-product of the hide and leather industries (Shephard 2000, 173–5), selling the product under the name Bovril. The product became popular amongst travellers and explorers, such as Henry Morton Stanley, who reportedly took Bovril’s meat extract on his 1865 African exploration and subsequently endorsed the product (Driver 1991, 134). However, the real commercial success of meat extracts was due to its successful promotion as a soup concentrate to the generals in the Franco-Prussian war (1870–1871) who were looking for a way to nourish the army while on the move (Shephard 2000, 173–5).

Over the course of the nineteenth century, ongoing improvement in food science also had an impact on preservation and, by extension, the categories of material culture that archaeologists find on sites. New and enhanced methods to store foods in sealed containers (bottles and tins) improved the anaerobic conditions needed for preservation and in turn changed the range of types and wares available. Preserving in glass bottles was first achieved in the late eighteenth century when Nicholas Appert successfully developed a method that involved the exposure of food-filled glass bottles to a heated water bath or under steam pressure at temperatures of 116–121°C (240–250°F) (Drummond and Wilbraham 1994, 317; Gruetzmacher et al. 1948, 4; Shephard 2000, 229). Appert’s development was in response to the need to supply wholesome foods to the French armed forces in battle; however, its application ultimately led to increased domestic and commercial food storage in bottles (Milner 2004, 30). Preserving foodstuffs in bottles in the home, also known as “canning”, gained popularity by the mid-nineteenth century when improved closure methods were developed. The two most successful closures were the porcelain-lined zinc lid or the glass lid jointed by a rubber ring gasket (Arnold 1983, 6).

Bottle forms and materiality

Identifying common food-related bottle forms, their contents and their use in food preparation is the first step in analysing bottles as indicators of foodways. The majority of bottle forms identified as glass food containers are of European origin. Wooden casks and ceramic food containers found on colonial sites can be of both European and Chinese origins, again highlighting the diversity of both colonial communities and their distribution networks. This section charts the development of some of the main container forms found.

Global glassmaking history

Glass has been manufactured and used to make vessels for many thousands of years, and glass bottles are one of the most common objects found on historical archaeological sites (Smith 2008, 16–17). The use of glass for storage of everyday products accelerated from the seventeenth century as more shapes were created and standardisation of storage sizing occurred (Jones and Sullivan 1989, 2; Lerk 1971, 4). The prosperity triggered by the Industrial Revolution in England, and the relative affordability of increasingly mass-produced glass, had an impact on the increase in the presence of glass vessels in assemblages throughout the modern period (Vader and Murray 1975, 1).

Glass blowing was originally a highly skilled trade, where boys as young as 12 were taken on as apprentices to learn the skill over years (Handford Henderson 2016; Schulz 2016). Bottle and container making for food storage and other products remained a primarily handmade process into the late eighteenth century. Soon, advances in glass moulding methods took over the handmade process, eventually followed by semi-automatic and fully automatic bottle-making machines. These advancements increased the production capacity of factories, from one team making up to 200 dozen (2,400) bottles per day by hand (Handford Henderson 2016, 81) to at least double that with the introduction of the semi-automatic machine. The production rate increased a further 180 per cent with the introduction of the fully automatic machine (Miller and Sullivan 2016, 189). These advancements lowered the price of manufacturing as less-skilled workers were hired to run machines. The fully automatic system employed by bottle makers today finds its roots in the methods of the semi-automatic machines of the late nineteenth century and the fully automatic machines of the early 1900s.

Glassmaking in Australia

Before the late nineteenth century, very few glassmaking factories existed in Australia. Most often, bottles were ordered from overseas factories and shipped to the colonies empty, to be filled upon arrival (Smith 2008, 19). The first glass factory in Sydney is believed to be a short-lived one owned by Simeon Lord and Francis Williams, which opened in Pyrmont in 1812. The factory closed in 1813 due to clashes in staffing between workers and management (Jones 1979, 35). The first successful bottle manufacturer in Australia was J. Ross of Sydney (1867–1919). The first successful bottle manufacturer in Melbourne was Melbourne Glass Bottle Works Company, a firm owned by Felton and Grimwade. They were an established pharmaceutical and importer company (1866), but they opened the glassworks in 1872 due to supply and cost issues that were having an impact on the primary business. By the 1910s, Felton and Grimwade acquired and amalgamated several bottle works companies and formed the now well-known Australian Glass Manufacturers Company (Moloney 2012; Vader and Murray 197, 14).

Ceramic containers

As well as glass bottles and containers, commercial commodities were packaged in ceramic containers, pots and bottles made mainly from stoneware and earthenware. Plain brown utilitarian ceramics of Chinese origin are generally characterised as brown-glazed stoneware (CBGS). The vessels contained preserved foods and liquids from the southern areas of China, particularly from the Guangdong province, which is inland to the west of Hong Kong. Foodstuffs contained within these vessels were mainly vegetables, meats, sauces, oils, condiments and alcohol.

The different forms of the CBGS were indicative of their contents; the four most common types are wide-mouthed, shouldered jars (Fut How Nga Peng) for non-viscous foodstuffs; “tiger whiskey” (Ng-Ka-Py liquor) bottles (Mao-Tai or Tsao Tsun); spouted jars (Nga Hu) for liquids; and globular jars (Ching) for bulk shipment of liquids and preserved items (Figures 8.1 and 8.2).

Figure 8.1 Chinese utilitarian vessels: (L) wide-mouthed shouldered jar, (M) spouted jar, (R) liquor jar. Photo: authors.

Figure 8.2 Large globular jar. Photo: authors.

Wide-mouthed shouldered jars were wheel formed, made of coarse grainy stoneware, usually 130 to 150 cm in height with unglazed bases.

Liquor bottles were made from finer clay, formed in moulds in three separate pieces, then joined together; they are 155 to 160 mm in height. Spouted jars are 130 to 140 mm in height with wheel-formed bases joined to mould-formed top sections and unglazed bases. Globular jars vary in height from 280 to 360 mm. They were probably completely wheel formed; they have lugs on the shoulders for securing capping pieces (Muir, 2003).

There is a high degree of standardisation in the forms of these CBGS, suggesting that their manufacture was to a basic design for each form, repeated across large numbers of independent potters. The firing of the ceramic containers was predominantly done in large “Dragon” kilns. The size of the containers ranged from 10 cm to over 1 m in height, with corresponding variations in their diameters and wall thicknesses. Correct placement in the kilns was critical to ensure proper firing temperatures of between 1100 and 1300 degrees Celsius was achieved to produce a stoneware ceramic.

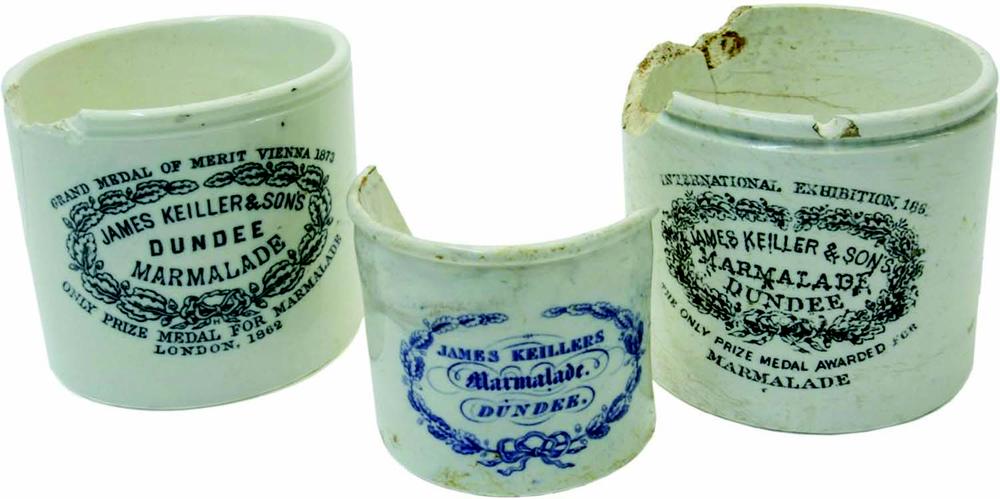

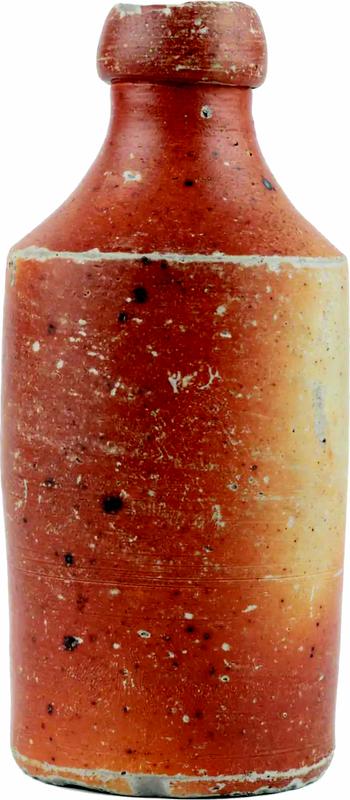

The primary commercial use for ceramic bottles of European origin was for the stoneware packaging of beverages; however, foods, such as condiments, were also packaged in earthenware pots and jars for shipment to Australia from European sources (Figure 8.3). Most ceramic storage vessels recovered in Australia are either salt-glazed or Bristol-glazed stoneware (Brooks 2005b, 33). While the Bristol-glazed bottles and jars were mostly imported from Britain, salt-glazed containers were made in the colonies from the early nineteenth century. During the 1820s, the introduction and instant popularity of locally manufactured ginger beer and spruce beer led to an increased demand for bottles (Figure 8.4). As there were no successful glass bottle manufacturers in Australia, the increased demand for bottles was filled by local potters (Ford 1995, 27). Prior to this, potters had been mainly producing utilitarian wares. The first successful stoneware bottle manufacturer is regarded as Sydney’s Jonathan Leak, who started a stoneware bottle tradition that was followed by other Sydney potters, including Thomas Field (1846–1880) and Enoch Fowler (Ford 1995).

Figure 8.3 Ceramic marmalade pots. Photo: authors.

Figure 8.4 Stoneware ginger beer bottle. Photo: authors.

Wooden casks

It is important to note that other materials were used to store foods and beverages. Certain products manufactured overseas were often transported to Australia in bulk containers such as wooden barrels and casks. Sizing produced by coopers ranged from the largest, called a “tun” (252 gallons = 954 litres) to the smallest, called a “pin” (4 gallons = 15 litres). All types of foods were transported in these large containers, from salted meats to beverages and dry foods like grains. Once these commodities arrived in Australia, the bulk products were often decanted into smaller volumes or, in the case of alcohol, were transported to the venue at which they would be sold.

Bottle availability and reuse

In the eighteenth early to mid-nineteenth centuries, bottles were seen as a product and commodity themselves, rather than simply packaging as they are seen today. Australian-based product manufacturers ordered bottles from overseas bottle manufacturers, however, high transport costs and long wait times for bottles to arrive made it difficult to acquire new bottles (Woff 2014; 2019). The few Australian-made bottles were a poorer quality product than those manufactured overseas, and product manufacturers preferred not to use them. This changed in the late nineteenth century, with the decrease in the number of imports received from Britain due in part to what is known as “The Long Depression” (1870s–1890s).

In the 1890s, glass factories in Melbourne and Sydney were working around the clock to keep up with the demand (Graham and Graham 1981, 56; Lucas 2002, 10).

As bottles were seen as owned by the product manufacturer who bought them, they were expected to be returned after being emptied to be washed and reused (Ellis and Woff 2017; 2014, 11–26; 2019). However, this did not always occur and caused enough stress to product manufacturers that in The Australian Brewers’ Journal, they labelled this issue “The Bottle Question”. Brewers in this journal discussed instances of loss, breakages and use by other manufacturers, and attempted to seek solutions (Australian Brewers’ Journal 1887, 8; Ellis and Woff 2017). Despite this system increasing the use-life of bottles up to decades (Adams 2003; Busch 1987, 68), the quantities of bottles available in the Australian colonies were still less than the demand required by product manufacturers (Graham and Graham 1981, 56; Lucas 2002, 10).

Adding to this problem was the issue of ownership, with embossing not becoming popular worldwide until the 1840s (Boow 1991, 1), although this continued to be prohibitively expensive into the late nineteenth century. Often, manufacturers could not justify adding this cost to the already high price of bottles (Woff 2014, 44; 2019). They used paper labels pasted to bottles to denote their ownership and advertise their product; however, once these were removed, it was impossible to tell who the un-embossed bottles belonged to (Woff 2014; 2019).

Additionally, product manufacturers were using whichever bottles they could acquire, and consequently, bottles were being used for products other than those they were intended for. Archaeological examples include case bottles usually used for gin and schnapps being used to hold medicines (Crook and Murray 2006), sarsaparilla and rum (Carney 1998), paint tint and cordial (Carney 1998) (Figures 8.5 and 8.6). These documented cases of bottles reused for other products highlight the need for reuse to be considered when analysing historical and archaeological collections (Boow 1991, 24; Woff 2014; 2019).

Figure 8.5 Late eighteenth to twentieth century gin/schnapps bottles. Illustration: E. Jeanne Harris.

Figure 8.6 Late eighteenth to early nineteenth century British types.

Illustration: E. Jeanne Harris.

Eventually, manufacturers offered to pay for returned bottles and in response, began charging for bottles sold with their product inside. During the early 1800s, empty wine bottles were sold for as much as six shillings per dozen, and by the 1850s were still being sold for four shillings per dozen (Boow 1991, 24). In comparison, an average labourer’s weekly wage in the early 1800s was five shillings (Boow 1991, 24), preserved fruit and pickles cost as much as five shillings per bottle (Boow 1991, 18), and in the 1850s, eggs were seen as a luxury item, costing about four shillings per dozen (Biagi 2019; Argus 1856, 4).

Similarly, secondary and adaptive reuse of Chinese, brown-glazed stoneware (CBGS) frequently occurred. According to oral histories collected in the USA in the early years of the twentieth century (Hellman and Yang 1997), jars were reused for storage, cooking and rainwater collection – they were the Chinese equivalent of the traditional “Mason” preserving jar or, more recently, disposable containers that are reused for storage purposes. The final disposal of a CBGS jar could have been immediate or occurred years after its functional utility had been exhausted. The standardisation of glaze, form and sizes over many centuries in China makes it difficult to date CBGS by typology or evolution of a form.

Bottle forms and functions

Over time, archaeologists have created an association between bottle shapes and their uses, and these relationships are applied to artefacts from historical archaeology collections. Within archaeology, such associations began in North American archaeological discussions (Brooks 2005a). These associations have been and continue to be influenced and informed by the language of bottle collectors and other interested parties (Vader and Murray 1975, 2).

At its most basic level, form refers to what the object is, i.e. “bottle”. Categorisation of bottle forms may be recorded using descriptors for shape such as “beer bottle”. Function refers to the use of the bottle, such as “food storage” (Brooks 2005a).

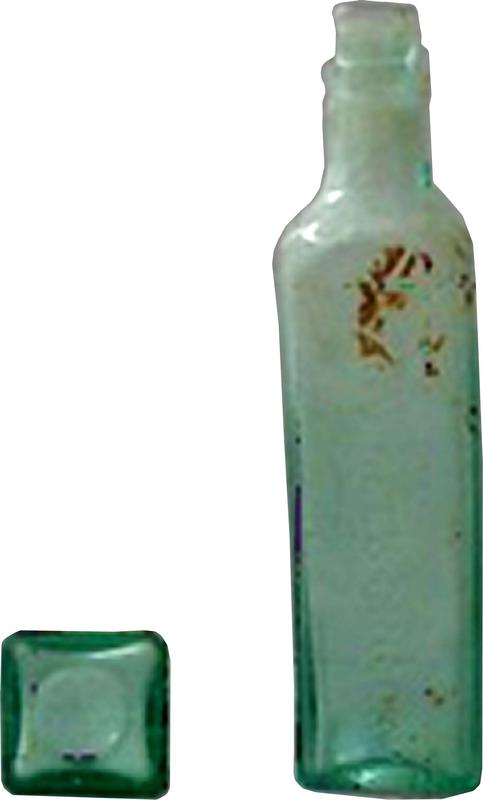

It is important to note that some forms existed that were used for a range of things, especially panelled light green and light blue bottles, which were used for foods, medicines and a range of other domestic and personal products, and so cannot be ascribed to a specific function (Woff 2014; 2019). Archaeologists and artefact specialists use form and function as interconnected ways to identify, describe, record, interpret and assign meaning to objects within historical archaeology collections. Form and function are ascribed by identifying particular profiles and characteristics of bottles, such as the colour, shape, style or decoration. These are used to identify and characterise a collection so that the information we record can be further interrogated, analysed and interpreted. Although form and function seem like straightforward ways to classify bottles, issues arise where these methods are solely used to identify objects (Brooks 2005a), including bottles. Due to the multitude of options for products contained within bottles, understanding the ways in which humans use and reuse objects along with further context about the excavation site and the people who interacted with this place are required to ensure that the interpretation of a collection of bottles or a broader archaeological collection can be as correct as possible. This approach can be seen in Carney’s 1998 article “A Cordial Factory in Parramatta, New South Wales”.

Dietary patterns

Whether free settlers or transported convicts, European immigrants in colonial Australia were predominately from Britain and Ireland. Throughout Europe, each of the distinct nations, cultures and regions had their own food traditions and practices, although there were also shared tenets and common staples that underpinned food and foodways. Many of these traditions came with these immigrant communities to Australia, although once here, the availability of foodstuffs, supply, climate and shared experience meant that some food practices were maintained (and remain part of Australian food cultures today), while others ceased in a new environment and context. Gradually, the diet of immigrant communities expanded and adapted to include locally available foodstuffs, such as Smilax glycophylla plant, whose leaves were brewed for “sweet tea” and whose red berries provided much-needed vitamin C to cure scurvy (Davey et al. 1977, 32–3), and meat obtained from local fauna such as kangaroo. According to Newling (2021, 150), “Some local resources were adopted more readily than others, for reasons including familiarity, taste, perceived health benefits, availability and accessibility and compatibility with culinary and cultural practices, or habitus”. There was also variability in habits for how foods were stored, prepared, and consumed (Wood 1977, xi).

The food patterns of the colonists were also reflected in the condiments and foods they used in the preparation and consumption of meals. Evidence of commercially packaged food products is found in the bottle assemblages recovered from archaeological sites. Some condiments (i.e. salt and oil) have such wide-ranging use in cuisines of all cultures that they contribute little to the interpretation of dietary patterns. Other condiments and foods (vinegar, sauces, potted meats, meat drinks, coffee, milk) provide an opportunity to understand how these foods were used in Australian cuisine and provide insight into dietary habits during colonial times. The following products represent some of the main foods and condiments found in glass bottles from archaeological contexts. They are discussed in relation to how they were made and how they were used in the preparation, service and consumption of foods, and other day-to-day uses.

Vinegar

Vinegar was ubiquitous in colonial cuisine. It was one of the staples in the First Fleet’s weekly ration, with each convict receiving 1/4 pint of vinegar, which was thought to prevent scurvy (Davey et al. 1977, 25). Early colonists also brought with them the preferences for foodstuffs preserved in vinegar. Preserving in vinegar gained prominence in Britain during the sixteenth century, replacing salting as a preservative, initially to meet the need for more nutritious foods for sea travel. As the population moved towards urban centres, the need to preserve foodstuffs for transport increased.

Vinegar making is a culinary process that is probably as old as brewing alcoholic beverages, and is a powerful preservative commonly used to promote fermentation (Shephard 2000, 85). Fermentation is “a natural process by which yeast or bacteria feed off sugars to produce alcohol or lactic acid” (Metheny and Beaudry 2015, 208). Fermentation as a process for food preservation has been used since before recorded times. This fermentation process, typically called “pickling”, preserved various foods, such as vegetables, fruits, meats and eggs in liquid-tight vessels such as stoneware and glass containers. Vinegar also figured prominently in colonial dishes. Recipes in The English and Australian Cookery Book, considered the first Australian cookbook, often included vinegar as an ingredient in the preparation of savoury pies and puddings, sauces and gravies (Abbott 1864). Popular in many Victorian Era British and Australian households was The Book of Household Management (Beeton 1861). It included an extensive recipe section, and besides the use of vinegar for pickling (preservation), vinegar was often an ingredient used in the preparation of meats, salads, sauces and flavoured vinegars used to enhance taste. Therefore, it is not unusual that vinegar is an oft-found ingredient in Australian cookery.

Medicinal uses of vinegar were numerous and varied. Doses of vinegar were used to treat scurvy cases, especially on ships during the voyage to the colonies (Clements 1986, 30). It also figures prominently in concoctions to counteract poisons (Beeton 1861, 1080). Topically, vinegar was used as an eyewash, in poultices and diluted in baths to reduce fever.

Non-corrosive and heat-resistant properties make glass bottles the ideal receptacles for storing vinegar and foodstuffs preserved in vinegar (Shephard 2000, 189) (Figure 8.7). Once the colonies were stably established, settlers began to process their own vinegar for the preservation of foods. However, an 1885 article in the South Australian Register (1885, 6) entitled “Colonial and Imported Vinegars” was a comparative assessment of the quality of colonial vinegar in relation to those imported from Great Britain. Colonial vinegars used in this assessment were mainly those from South Australia, including Seppelts, Lomes, Barton and Co, and Waverley Vinegar Works. Imported vinegars include those made by Champion, Crosse and Blackwell, Potts, and Hill, Evans and Co. The author’s findings suggest that colonial vinegars, except those made by Seppelts, were all inferior to British vinegars and too weak to be used for pickling. Furthermore, vinegar for pickling is only about half the strength of ordinary vinegar. This weakness of colonial vinegars may account for the continued popularity of imported vinegars in the colonial market throughout much of the nineteenth century.

Figure 8.7 Champion vinegar bottle. Photo: authors.

Chutneys

The term chutney is applied to anything preserved in sugar and vinegar and generally includes fruits, vegetables and/or herbs (Figure 8.8). English chutney is a strong-tasting condiment based on Indian cuisine, used to enhance the flavour of dishes. First introduced into the British diet by eighteenth-century officials returning from postings in India, chutney was gradually adapted to the British palette and had peak popularity during the mid-nineteenth century (Rolfson 2017, 3–4). Evidence of this popularity is demonstrated by the variety of chutney recipes listed in cookery books of the time (Abbott 1864; Beeton 1861).

Figure 8.8 Pickle/chutney jar. Photo: authors.

Sauces

During the nineteenth century, Australian dietary patterns were characterised by a preponderance of meat (Clements 1986, 34) due to an abundance of fresh and inexpensive meat as a by-product of the wool industry and increasing numbers of cattle ranches in the 1850s (Ashcroft 1977, 14). In British culinary tradition of the period, sauces accompanied most meat dishes, so they naturally became a significant part of Australian colonial cuisine. This traditional dietary pattern dates back to the British cuisine of the Middle Ages when meats were never eaten dry (Beeton 1861, 118). Most prominent by the colonial period was the “one sauce of England” (Acton 1859, 105), which consisted of melted butter thickened with egg yolks or cream (Freeman 1989, 124). Fish sauce was also a favourite, with its own long history in English cuisine. Initially, fish sauces were a culinary solution to preserving fish in hot, humid climates (Smith 1998, 299). In the colonial period “English ketchup” (also, catsup) was not a tomato-based condiment but a homemade spiced vinegar and anchovy sauce (Sydney Living Museum, n.d.). The English first encountered this condiment during their seventeenth-century settlement in Sumatra (today known as Indonesia) (Smith 1998, 302). This condiment’s first successful commercial development was Lee and Perrin’s Worcestershire sauce during the nineteenth century. At the time, the main ingredient of Worcestershire sauce was soy sauce with other ingredients including anchovies, shallots, garlic, tamarind, salt and vinegar (Shurtleff and Aoyagi 2012, 5). Worcestershire sauce was served with fish, hot and cold meats, steaks, gravies, soup, etc. By the 1850s, Lee and Perrin’s sauce was distributed worldwide and was eventually imitated by others, such as English firm Holbrooks from 1872 and Australian firm Neumans from 1909 – who also imitated the Lee and Perrin’s bottle shape (Figure 8.9). Bottled sauces, such as Worcestershire sauce, were a staple condiment in Australian households, with many consuming more than a bottle of sauce each week (Walker and Roberts 1988, 64).

Figure 8.9 Worcestershire sauce bottle. Photo: authors.

Potted meats/spreads

Meats and fish are kept longer if mashed into a paste and/or potted. The concept of potted meats evolved from the ever-popular pastry pie-cased dish of the seventeenth century. As a mainstay of “pocket foods”, the meat pie had one shortcoming – the lack of preservation. Consequently, by the mid-1600s, the pastry crust gave way to the earthenware pot. Earthenware pots could be sealed by a layer of oil, butter or fat, making them airtight and watertight, resulting in potted meats becoming a viable foodstuff for seasonal preservation, travellers and transported military (Shephard 2000, 182). This method is still used in modern preservation and commercial packaging of meats and fish, generally sold in metal or glass containers.

The process of potting meats was often an in-home activity. This is especially true in colonial Australia, where there was an abundance of meat. Potted meats were also sold by the local grocer and while they did not publish advertisements for the sale of potted meats, there are numerous accounts of theft and/or shoplifting noted in newspapers throughout the colonies (Tasmanian and Austral-Asiatic Review 1845, 3). Imported potted meats from European companies, such as in England and France, were also sold and advertised (Sydney Morning Herald 1847, 4; Argus 1853, 5); most advertised of these was Strasbourg paté de foie gras (Figure 8.10).

Figure 8.10 Strasbourg paté de foie gras pot lid from the University of South Australia’s City West Learning Centre Site, Adelaide (Harris 2013, 38).

Fish paste bottles are a commodity commonly found in the archaeological record. Fish paste was a common household condiment made by pounding fish and mixing with butter (or other fat) and various spices, including mace, cayenne and nutmeg (Beeton 1861, 226; Monro 1922, 202). Common fish pastes include anchovy, herring kippers, salmon and prawns. While often made in the home, commercially potted fish pastes, such as essence of anchovies, were available during the early 1800s. An early imported fish paste to Australia was Fine Yarmouth’s bloater paste, which was first advertised in Hobart in 1837 (The Hobart Town Courier 1837, 1). An often-found commercial fish paste jar in the Australian/New Zealand archaeological collection is Peck’s (Figure 8.11). Peck’s large-scale commercial packaging began in the 1890s and was a common commodity in an Australian pantry from the early 1900s (Australian Food History Timeline, n.d.).

Figure 8.11 Examples of common fish paste bottles: (L) Peck’s; (R) unspecified.

Photo: authors.

Meat drinks

Beef extract is a nineteenth-century food preservation innovation that served to advance food storage technology. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, Baron Justus von Liebig successfully developed commercially packaged beef extract in the 1860s, which was subsequently sold as “invalid soup” under the trademark Bovril (Shephard 2000, 175) (Figure 8.12). While advertised as a means to rebuild muscle strength in the infirm, twentieth-century research indicates that the only beneficial ingredients were the essential ingredients (B vitamins, riboflavin and nicotinic acid) that, in combination, served to stimulate the flow of gastric juices, promote appetite and be a digestive aid (Shephard 2000, 174).

Figure 8.12 Bovril’s beef extract bottle. Photo: authors.

Coffee

Coffee was introduced to Europe and North America about the same time as tea, however, coffee was far more affordable than tea (Ellis 2004, 123–4). The first British coffee house was opened in London in 1652 by a Turkish merchant and was an instant success. Soon after, coffee houses sprang up throughout the country (Drummon and Wilbraham 1994, 116). The last two decades of the nineteenth century saw Australian “Coffee Palaces” established. Modelled on the European and North American coffee house, these businesses were temperance hotels that served no alcohol (Denby 2002, 174).

Instant coffee for in-home consumption, in the form of a cordial concentrate, was available in the 1820s but was an imported luxury, so much so that the theft of two dozen bottles of expensive coffee essence was reported among the items taken from the household stores of Mr R. Howe’s Sydney residence (The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 1827, 3). The development of Symington’s Essence of Coffee and Chicory in 1882 provided a convenience food. Symington’s concentrate allowed for coffee in a minute by adding the product to boiling water (Figure 8.13).

Figure 8.13 Symington Essence of Coffee and Chicory bottle. Photo: authors.

Dairy

Milk and cream are both beverages and condiments used to prepare culinary dishes. The history of dairy in Australia began with the colonisation of New South Wales in 1788, which included plans to establish a dairy. These plans were thwarted shortly after landing when the four cows and one bull escaped and were not recovered until years later in 1795 (Clements 1986, 32). The first commercial dairies were established in the early 1800s, and included Dr John Harris’ Ultimo dairy (1805) and the Van Diemen’s Land Company dairy/factory (1820s). Hindered by the nineteenth century’s slow transport methods and the lack of refrigeration, “loose” milk was only sold locally. In the 1890s, the introduction of pasteurisation improved milk preservation; however, commercially bottled milk was not generally available until the 1920s (Farrer 2001, 100). Until the mid-1940s, milk was mainly served at the local shop from 20-gallon cans into household containers provided by the buyer (Kameny 2008, 20).

Chinese dietary patterns

Thus far, the discussion of dietary patterns has focused on foodstuffs consumed by the predominant Australian population of European heritage. The nineteenth-century migration of Chinese people throughout the Pacific Rim represents one of the world’s largest population movements (Voss and Allen 2008, 6). By the 1860s, there were approximately 40,000 Chinese immigrants in the Australian colonies, most of which had arrived to prospect in the goldfields, and comprised 3.8 per cent of the colonial population.

Spier’s study of shipping invoices identified more than 130 specific Chinese foodstuffs that were imported into the USA in the mid-nineteenth century. The list of items includes:

oranges, pumelos [sic], dry oyster, shrimps, cuttlefish, mushrooms, dry bean curd, bamboo shoots, narrow-leaved greens, yams, ginger, sugar rice, sweetmeats, sausage, dry duck, eggs, dry fruit, salt ginger, salt eggs . . . tea oil, dry turnips, beetle nut, orange skins, kumquat, duck liver, melon seed, dried duck kidneys, minced turnips, shrimp soy, chestnut flour, birds’ nests, fish fins, arrowroot, tamarind, dried persimmons, dried guts, bean sauce, lily seed, beche de mer, Salisburia seed, taro, and seaweed (Spier 1958, 80).

A similar range of food products likely made their way to Australia. The range of products provided diverse flavourful additions to colonial fare, while also supplementing vitamin and mineral intake.

CBGS vessels, discussed earlier in this chapter, are a type of consumer product that is an aspect of foodways evidencing “culturally distinctive performances of status and social relations” (Mullins 2011, 138). The sharing of food may also have drawn the Chinese diaspora community closer together in the face of marginalisation as the products were uniquely Chinese and reinforced significant elements of cultural identity. Chapter 6 outlines the importance of roast pork and feasting in diaspora identity, but it is important to recognise that assemblages associated with imported products may also have been a focal point for community and cultural practice. The foods in CBGS allowed the Chinese to maintain pre-existing foodways and dietary habits along cultural lines. For the Chinese, it was traditionally important to maintain a balance not only between fan (starch) and ts’ai (meat and vegetables) in their culinary practices but also by providing “hot” and “cold” humoured foods in balanced proportions (Chang 1977, 6–7). Adding preserved, fermented and pickled foods allowed the maintenance of the enduring principles necessary for constructing a healthy meal.

The importation of CBGS and their associated contents was part of a complex trade network that operated within and outside the primary European transportation networks in Australia, New Zealand, the USA and Canada. Originating as they did in mainland China, both the contents and the containers would have had a long journey to their recipients, passing through the hands of farmers, potters, manufacturers, merchants, cargo handlers, entrepreneurs and middlemen along routes that included traffic by foot, cart, wagon, ship, pack animal and railroad.

Discussion

Bottles and bottle fragments are common finds on historical archaeological sites. Archaeologists exert considerable energy to measure and date these, but it is critical to remember that they represent an important part of the food cultures of colonial Australia and so we need to understand them in this wider context. This chapter provides the background and tools needed for archaeologists to assess bottles in artefact collections more holistically and to understand their role in food culture. To do this, we need to understand contextual matters such as the background history of preserving methods, improved bottling technologies and an introduction to uses of package commodities. This context contributes to our understanding of the range of factors that influence dietary patterns, such as market access, ethnicity and socio-economic status of individuals, households and communities.

Engaging with the nature of the site also helps us to understand how and why certain preserves were being eaten in different locations and can shed light on the nuanced dining experiences of people in the past. Artefact collections show us that the patterns of meals consumed in a private residence varied considerably from those enjoyed in a public house or hotel. For example, a comparative study of condiment bottles from nineteenth-century Parramatta, NSW, households (Harris 2021) with a Penrith, NSW, hotel of the same period (Harris 2005, 4) indicates that while the types of condiments used in both settings were the same, there was a considerably higher relative frequency of sauces such as Worcestershire and tomato found in the hotel assemblage (Table 8.1). Combined with other data from these artefact collections, such as cuts of meats or table-service forms, these results may establish differences in dietary patterns between the two settings. This helps us to understand the varied experiences of dining during the nineteenth century, and with the benefit of historical records, we can more fully appreciate colonial food cultures in their entirety.

| Condiment | 8 Parramatta Households (%) | Red Cow Hotel (%) |

|---|---|---|

| oil/vinegar | 39.5 | 25 |

| pickle/chutney | 48.5 | 35.4 |

| sauce | 8.6 | 25 |

| soy sauce | 1.9 | 0 |

| fish paste | 1.5 | 4.2 |

Table 8.1 Relative frequencies of condiment bottles recovered from Parramatta households and the Red Cow Hotel.

There is a possibility of a multi-cultural household, perhaps with servants who dine separately and have a different dietary pattern than their employers. Additional research is essential before drawing any conclusions regarding the constituents of the household. For example, Chinese export porcelain tableware and CBGS food-storage bottles were in the artefact collection from a wealthy household on Hindley Street, Adelaide, SA (Harris 2013, 45–6). However, several factors led to inconclusive results as to whether the household included Chinese servants. First, from the eighteenth century, Chinese export porcelain was inexpensive utilitarian ware. The East India Company’s trade monopoly on the Indo-Pacific region and the colony’s rising needs for such commodities contributed to the increased presence of this ware in the colonial market (Staniforth and Nash 1998, 5). Therefore, Chinese export porcelain in the artefact collection was not necessarily indicative of a Chinese presence in the household. The association of the CBGS bottles was clouded by the fact that there was an early concentration of small Chinese businesses east of the project area, including a general importer and a tea importer. Whilst there are no documented Chinese residents within the project area, the presence of ceramics of Chinese origin suggests some interaction between European and Asian factions of the community (Harris 2013, 45–6).

Conclusions

The purpose of this chapter is to emphasise the importance of identifying food bottles and understanding foodways as foundational steps to further our understanding of dietary patterns. These tools, considered with historical documentation, contribute to an understanding of foodways and aid the interpretation of the complex nature of colonial Australia’s food and dining experiences.

One of the first steps presented is a discussion of common food bottles and their intended contents. Assigning a date to a bottle, which is achieved by researched data on documented manufacturing techniques, bottle manufacturers or products, follows bottle form and is useful as an aid in its placement in the documented timeline for a site. Once these steps have been achieved, analysis of a bottle collection can lead to an understanding of who the bottles belonged to and their food and dining habits. Food bottles can assist in the interpretation of dietary patterns, cultural affiliation and, to some extent, the status of the people associated with these bottles. A main use for data generated for a collection of bottles is that it can contribute to a comparative analysis with other collections. This includes comparison of similar site collections, such as the example of Parramatta and Penrith condiment bottles, or a comparison with historical documentation, such as the example of CBGS bottles and Chinese residents and business.

References

Abbott, E. (1864). The English and Australian cookery book. London: Sampson Low, Son and Marston.

Acton, E. (1859). Modern cookery. London: Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans.

Adams, W.H. (2003). Dating historical sites: the importance of understanding time lag in the acquisition, curation, use, and disposal of artifacts. Historical Archaeology 37(2): 38–64.

Argus (1856). The Melbourne produce market, 21 January, 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article4828753.

Arnold, K. (1983). Australian preserving and storage jars pre-1920. Bendigo,

VIC: D.G. Walker.

Arnold, K. (1990). A Victorian thirst. Bendigo, VIC: Crown Castleton.

Arnold, K. (1991). Australian glass, 1900–1950: valuation guide. Maiden Gully, VIC: Crown Castleton Publishers.

Ashcroft, E. (1977). Introduction. In B. Wood, ed. Tucker in Australia. Melbourne: Hill of Content.

Australian Food History Timeline (n.d.). Australian Food Timeline, accessed 8 February 2021. https://australianfoodtimeline.com.au/pecks-pastes-australia/.

Australian Brewers’ Journal 1887 (1882–1921), Melbourne.

Baugher-Perlin, S. (1982). Analysing glass bottles for chronology, function, and trade networks. In R.S. Dickens, Jr., ed. Archaeology of urban America: the search for pattern and process. New York: Academic Press.

Beeton, I. (1861). Beeton’s book of household management. London: S.O. Beeton.

Biagi, C. (2019). In for a penny, in for a pound: faunal analysis of the Jones Lane Archaeological Precinct, Honours thesis, Archaeology Department, La Trobe University, Bundoora.

Boow, J. (1991). Early Australian commercial glass: manufacturing processes. Sydney: The Heritage Council of NSW.

Brooks, A. (2005a). Observing formalities – the use of functional artefact categories in Australian historical archaeology. Australasian Historical Archaeology 23: 7–14.

Brooks, A. (2005b). An archaeological guide to British ceramics in Australia.

The Australasian Society for Historical Archaeology and La Trobe University Archaeology Program.

Busch, J. (1987). Second time around: a look at bottle reuse. Historical Archaeology 26: 67–80.

Carney, M. (1998). A cordial factory in Parramatta, New South Wales. Australasian Historical Archaeology 16: 80–93.

Chang, K.C., ed. (1977). Food in Chinese culture: anthropological and historical perspectives. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Clements, F. (1986). A history of human nutrition in Australia. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Crook, P. and T. Murray (2006). An archaeology of institutional refuge: the material culture of the Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney 1848–1886. Sydney: Historical Houses Trust of New South Wales.

Davey, L., M. MacPherson and F.W. Clements (1977). The hungry years 1788–1792. In B. Wood, ed. Tucker in Australia. Melbourne: Hill of Content.

Denby, E. (2002). Grand hotels: reality and illusion. London: Reaktion Books.

Drummond, J.C. and A. Wilbraham (1994). The Englishman’s food: a history of five centuries of English diet. London: Pimlico.

Ellis, A. and B. Woff (2017). bottle merchants at A’Beckett Street, Melbourne (1875–1914): new evidence for the light industrial trade of bottle washing. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 22(1): 6–26.

Ellis, M. (2004). The coffee house: a cultural history. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Farrer, K.T.H. (2001). Food technology. In Technology in Australia 1788–1988. Melbourne: Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering. https://www.austehc.unimelb.edu.au/tia/100.html.

Freeman, S. (1989). Mutton and oysters: the Victorians and their food. London: Victor Gollancz.

Ford, G. (1985). Australian pottery: the first 100 years. Wodonga, Victoria: Salt Glaze Press.

Goody, J. (2019). Industrial food: towards the development of a world cuisine. In A. Julier, C. Counihan and P. Van Esterik, eds. Food and culture, 263–82.

New York: Routledge.

Graham, M. and D. Graham (1981). Australian glass of the 19th and early 20th century. Sydney: David Ell Press.

Gruetzmacher, L.C., T. Onsdorff and M. Mack (1948). Canning for home food preservation. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State System of Higher Education, Federal Cooperative Extension Service, Oregon State College.

Handford Henderson, C. (2016). Glassmaking: III – The evolution of a glass bottle. In P. Schultz, R. Allen, B. Lindsey and J.K. Schulz, eds. Baffle marks and pontil scars: a reader on historic bottle identification, 71–89. Germantown, MD: Society for Historical Archaeology.

Harris, E.J. (2021). Cleanliness is next to Godliness: the influence of Victorian values on health concerns in nineteenth-century Parramatta, NSW. PhD thesis, University of New South Wales, Armidale.

Harris, E.J. (2013). UniSA City West Learning Centre Site, Adelaide, SA: Analysis of Artefacts. Report to Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd.

Harris, E.J. (2005). Specialist Glass Report: Red Cow Inn and Penrith Plaza, Penrith. Report to Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, Leichhardt.

Hellman, V.R. and J.K. Yang (2007). Previously undocumented Chinese artifacts. In M. Praetzellis and A. Praetzellis, eds. Historical archaeology of an overseas Chinese community in Sacramento, California; Volume 1: Archaeological Excavations. Rohnert Park, CA: Anthropological Studies Center Sonoma State University Academic Foundation, Inc.

Hintz, T., K.K. Matthews and R. Di (2015). The use of plant antimicrobial compounds for food preservation. BioMed Research International, 1–12.

DOI: 10.1155/2015/246264.

Hobart Town Courier (1837). Advertising, 8 September, 1.

Jones, D. (1979). One hundred thirsty years: Sydney aerated water manufacturers from 1830 to 1930. Deniliquin, NSW: Reliance Press.

Jones, O. and C. Sullivan (1989). The Parks Canada Glass Glossary for the description of containers, tableware, flat glass and closures. Ottawa: Environment Canada.

Kameny, R. (2008). Australian milk and cream bottles and dairy related items. Bendigo, VIC: Crown Castleton Publishers.

Lerk, J.A. (1971). Bottles in Australian collections. Bendigo, VIC: J.A. Lerk.

Lucas, L. (2002). Glass bottle recycling in Victoria. Honours thesis, Archaeology Program, La Trobe University, Melbourne.

Metheny, K.B. and M. Beaudry (2015). Archaeology of food: an encyclopedia.

New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Miller, G. and C. Sullivan (2016). Machine-made glass containers and the end of production for mouth-blown bottles. In P. Schultz, R. Allen, B. Lindsey and J.K. Schulz, eds. Baffle marks and pontil scars: a reader on historic bottle identification, 189–204. Germantown, MD: Society for Historical Archaeology.

Milner, M. (2004). Fruit jars…a history worth remembering. Bottles and Extras, winter(2): 30–3.

Moloney, D. (2012). A history of the Melbourne glass bottle works site including its industrial context: Spotswood, Victoria. Report to Museum Victoria.

Monro, A.M. (1922). The practical Australian cookery. Sydney: Dymock’s Book Arcade, Ltd.

Muir, A.L. (2003). Ceramics in the collection of the Museum of Chinese Australian History. Australasian Historical Archaeology 21: 42–9.

Mullins, P.R. (2011). The archaeology of consumption. Annual Review of Anthropology 40: 133–4.

Munsey, C. (1970). The illustrated guide to collecting bottles. New York: Hawthorne Books.

Roberts, B. (n.d.). James Harrison refrigeration pioneer. CIBSE Heritage Group online website, accessed January 2022. http://www.hevac-heritage.org/built_environment/pioneers_revisited/harrison.pdf.

Rolfson, T. (2017). Curries, chutneys, and Imperial Britain. Constellations 8(2): 1–9. DOI: 10.29173/cons29329.

Schulz, P. (2016). The American glass bottle industry – a brief history. In P. Schultz, R. Allen, B. Lindsey and J.K. Schulz, eds. Baffle marks and pontil scars: a reader on historic bottle identification, 11–23. Germantown, MD: Society for Historical Archaeology.

Selinger, B. (2013). Refrigeration: an Australian connection. Chemistry in Australia May: 20–21.

Shephard, S. (2000). Pickled, potted and canned: how the preservation of food changed civilisation. London: Headline Book Publishing.

Shurtleff, W. and A. Aoyagi (2012). History of Worcestershire Sauce (1837–2021); extensively annotated bibliography and sourcebook. Lafayette, CA: Soyinfo Center.

Smith, A.F. (1998) From garum to ketchup: a spicy tale of two fish sauces. In

H. Walker, ed. Fish: Food from the Waters: Proceedings from the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1997, 299–307. Devon, UK: Prospect Books.

Smith, F.H. (2008). The archaeology of alcohol and drinking. Gainesville,

FL: University Press of Florida.

Spier, R.F.G. (1958). Food habits of nineteenth-century California Chinese. California Historical Society Quarterly 38: 79–136.

Sydney Living Museums (2017). Let’s katchup sometime, accessed 1 February 2021. https://blogs.sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/cook/lets-katchup-sometime/.

Sydney Morning Herald (1847). Advertising, 7 June, 4.

Tasmanian and Austral-Asiatic Review (1845). Advertising, 19 June, 3.

Twiss, K. (2012). The archaeology of food and social diversity. Journal of Archaeological Research 20: 357–95. DOI: 10.1007/s10814-012-9058-5.

Vader, J. and B. Murray (1975). Antique bottle collecting in Australia. Sydney: Ure Smit.

Voss, B. and R. Allen (2008). Overseas Chinese archaeology: historical foundations, current reflections, and new directions. Historical Archaeology 42(3): 5–28.

Walker, R. and D. Roberts (1988). From scarcity to surfiet: a history of food and nutrition in New South Wales. Kensington, NSW: New South Wales University Press.

Woff, B. (2014). Bottle reuse and archaeology: evidenced from the site of a bottle merchants’ business. Honours thesis, Archaeology Department, La Trobe University, Bundoora.

Woff, B. (2019). The reliability of bottle form for ascertaining function: bottle reuse and archaeology. Australasian Historical Archaeology 37: 37–42.

Wood, B., ed. (1977). Tucker in Australia. Melbourne: Hill of Content.

Zumwalt, B. (1980). Ketchup pickles sauces: 19th century food in glass. Fulton,

CA: Mark West Publishers.