7

Baked, boiled, roasted, steamed and stewed

Kitchens and cooking appliances as artefacts of domestic life in colonial Australia

Introduction

The art of cookery – generally accepted as the practice of heating or treating organic substances to turn them into “food”, that is, safely edible and palatable substances – has evolved through time, and with it, the development of different techniques and subsequently, cooking appliances. Shaped by geographical and environmental factors, and cultural transmission, each culture has its own culinary particularities, influencing what and how foods are grown, processed, cooked, eaten and consumed. From the first arrival of colonists from England in 1788, Australian culinary culture was by-and-large transferred from Britain, and in many instances, adapted to local conditions (see Newling 2021; for British context see Pennell 2016 and Lehmann 2003.)

It is rare, however, to find historic kitchens intact. Kitchens tend to be upgraded more than any other part of a house, with new technology and changing lifestyles. Kitchens altered significantly from the mid-nineteenth century. Open hearth fires, where the majority of cooking once took place, were modified or replaced with safer and more fuel-efficient iron “ranges” (open, enclosed and semi-enclosed) fired with wood, manufactured coal (which emitted highly noxious fumes) or preferably, cleaner-burning charcoal. These solid-fuel appliances were gradually eclipsed in urban settings after gas was piped into homes from the late 1800s, and later, electric “cookers”, which did not begin to dominate until after the Second World War (Delroy 1990, 268–70). Gas lighting and artificial refrigeration became available during this time but were not always affordable, and piped hot water cannot be assumed until the 1950s; even later in some households. And yet, as the hundreds of recipes in nineteenth-century cookery books demonstrate, a vast array of dishes could be produced without what are now regarded as basic essentials.

This chapter explores the cooking methods employed in Australian households before gas and electric appliances came into common use in the early twentieth century. It is by no means a comprehensive history of nineteenth-century kitchens, cookery or culinary technology. Instead, it approaches the kitchen as an artefact, or more-so an assemblage of artefacts, with an aim to providing an understanding of cooking facilities and the types of apparatus, vessels and implements used in domestic settings, and the practices involved in using them. Sources of information include extant kitchens (original or reinstated) in heritage sites and house museums, trade catalogues, household manuals and cookbooks, and depictions of domestic kitchen technology in artworks. By illuminating the less tangible aspects of colonial cookery this chapter aims to add dimension to these material objects and built environments so they can be recognised in relational terms, in contexts of both food production and social activity.

The chapter is in two parts. The first looks at kitchen facilities in both large estate-style houses and humbler cottage dwellings, offering surviving examples that are publicly accessible where possible. The examples are by no means exhaustive and are limited to my own encounters, predominantly in Sydney, Canberra and Tasmania. The second part of the chapter looks more closely at the types of cookery performed in these spaces.

Part one: the kitchen

Today we think of kitchens as one room with multiple fittings and appliances, from the simple toaster and electric kettle to a sink and fridge. The functions of these culinary conveniences were once (and still are in some cultures) the responsibility of the cook, as necessary components of household management. Access to water was integral, and temperature, light and moisture needed to be carefully managed. The general principles of their management were based on longstanding European practices, as was domestic architecture, including the placement of the kitchen (Sambrook and Brears 1993). Conditions in Australia were often more extreme than those experienced in cooler climes, and although houses ostensibly followed northern hemisphere design conventions, these practical considerations were often incorporated into, or indeed, dictated, the design of food preparation and storage areas in colonial dwellings.

Many large estates produced much of their own meat, milk, bread, garden and orchard produce, requiring a slaughterhouse and butchery, and possibly a smokehouse, a dairy, bakery and fruit stores. Closer to townships and urban areas these foods could be purchased from local markets and providores. Even so, many households maintained vegetable gardens and fruit trees, and some kept goats for fresh milk and made their own bread. Houses of all kinds needed some kind of pantry store for dry goods, cool spaces for perishables, a scullery or washing up area, in addition to the main cooking facilities. We will look first at these facilities in large and affluent houses, and then how their functions were addressed in smaller households.

Expansive kitchens

It was not uncommon for kitchens of large affluent houses, especially if they were once some distance from towns and markets or supported an estate or farm, to feature a series of inter-related apartments or offices, each with its own function, as part of the kitchen (Sambrook and Brears 1993; Pennell 1998). Easily accessible metropolitan examples include Vaucluse House and Lindesay in Sydney, Rippon Lea in Melbourne, Ayers House in Adelaide, Newstead House in Brisbane, and Lanyon near Canberra.

Scullery

The principal function of a scullery was for washing up and other activities involving water such as scrubbing vegetables. The scullery was usually in close or immediate proximity to the main kitchen, but might also service the larder and dairy (discussed shortly). If not plumbed, the scullery needed to be in easy access to a water source. Some sculleries had a fire or cooking range to heat water for culinary use, and prior to plumbed washrooms, might also provide hot water for other household requirements, including personal ablutions in bedrooms.

Dry-store

Dry goods needed to be close at hand to the kitchen, but positioned away from light, heat and damp to prevent them becoming musty, stale or rancid, and minimise pest infestations. Houses in remote areas kept bulk stores and drew from them in smaller amounts according to weekly or daily needs, keeping the ready supply in bags, wooden tubs and ceramic crocks in a well-ventilated pantry or cupboard in the kitchen. Bottled preserves and condiments could also be kept in a pantry store.

Larder and dairy

Meat and milk products were traditionally stored separately and needed to be kept as cold as possible. The larder, or meat-locker, and dairy, or milk room, were usually located in the coolest parts of the kitchen complex, ideally in a southern location. They were often dug into the ground or in a basement or cellar, screened from sunlight, and well-ventilated to encourage airflow and allow warm air to escape (Beeton 1861, 1006). Surviving sunken or below ground larders and dairies can be seen at Vaucluse House museum and Government House in Sydney, and at Parramatta, the archaeological remains of the dairy that once served Old Government House.

The larder housed processed and preserved meats and animal products for use in the short-term, such as flitches of bacon and ham, either hanging from hooks in the ceiling or kept in ventilated cabinets. The latter was also used to store potted meat, fish and cheese preparations preserved in clarified butter; and sweet and savoury jellies such as brawn. Glazed vats or tubs were used for brine-pickled pork, corned beef and tongue. Cured meats that required little intervention could also be stored in cellars for longer periods of time. Eggs would also be stored in the larder in boxes lined with straw.

The dairy or milk room was both a storage space and processing area. Generally fitted out with stone benches, freshly drawn milk could cool in wide open dishes on the top of the bench without conducting heat to the storage bays below. Cream that naturally rose to the top of the milk as it cooled would be churned into butter, and the skimmed milk used for other purposes. Several nineteenth-century cookery texts offer detailed instructions on the care and management of the dairy and the domestic production of butter and cheese (e.g. Rundell 2009 [1816], 259–69; Beeton 1861, 1006–8).

Although it was imperative that the dairy and larder be kept cool, ideally there would be access to water and a cooking stove nearby. The science behind pasteurisation was not identified until the late 1800s but it was understood that scalded – not boiled – milk would stay “sweet” for longer (Rundell 2009 [1816], 267–8). Milk also needs to be heated to certain temperatures to make different cheeses and yoghurt-style curd, and pickling solutions for meat preparations, such as corned beef, needed to be replaced or refreshed by re-boiling. It was also understood that equipment and utensils must be immaculately cleaned after and before use to prevent food spoilage. Drainage channels along the floor were a common feature of milk rooms, used to conduct away waste products such as whey (though this was often saved for animals) therefore indicating the liberal use of water for cleaning in these rooms.

Produce stores

Various techniques were used to keep fruit and vegetables beyond their natural seasons. Soft leafy greens would not store well but root vegetables, hardy greens (such as cabbage) and some kinds of fruit (especially if picked unripe) could be kept for extended periods in tubs of sand in a cellar or other cool space. Fruit could also be sundried, preserved as jam or in sugar syrup, or made into chutney. Apples and flavourless “jam melons” were popular fillers for jams of expensive and exotic fruit such as stem ginger and pineapples, while apples, marrows (giant zucchinis), and chokos (from the late 1800s) were used to add bulk to chutneys and relishes, or fruit pie fillings that were preserved in jars for later use. Beans and cauliflower were made into Indian piccalilli or mustard pickles, and from the mid-1800s, tomatoes were combined with fruit for various savoury sauces and condiments. Vegetables were also pickled in brine or vinegar, or fermented as sauerkraut in earthenware jars or later, in glass bottles. English cookery author Maria Rundell (1816) advises that vinegar be boiled in a jar, as acids dissolve the lead in the tin lining of saucepans, and similarly, that unglazed jars be used to store pickles “as salt and vinegar penetrates the glaze, which is poisonous” (Rundell 2009 [1816], 178). The vessels could be sealed with cork or parchment, perhaps with a coat of wax or whipped egg white, and kept in a cool and dry cupboard or pantry-store (see Shepherd 2000, 187–91). Glass mason jars with porcelain screw caps were advertised from the early 1880s. These shelf-stable preserves were generally kept in a pantry in or near the kitchen, or in a cellar for longer-term or bulk storage.

Household management

These rooms and spaces were tended by kitchen staff under the direction of the cook, who followed in turn, the instructions of the mistress of the house, or in a very well-staffed household, a housekeeper. The relationship between their various functions is important on both practical and social terms, requiring careful administration of staff and resources or in nineteenth-century vernacular, domestic economy. Good household management involved knowledge and skills in a range of culinary arts and practical sciences now largely lost in domestic settings, to ensure the supply of particular foods and minimise waste by taking advantage of seasonal produce and climatic conditions to maximise fuel efficiency, time, energy and cost of labour.

Social interactions between the people who worked in these spaces, and the ways they interacted with different members of the household, whether servants or family, are equally important as the material functions of these areas. Television series such as Downton Abbey highlight the social hierarchy of servants, from lowly scullery maid to housekeeper or butler, and lines of communication with the master and mistress of the house. They, and their duties, were all part of the rhythm of a household, and some employers formed close and caring relationships with their staff.

With the rise of the middle class in the 1800s, many of the nouveau riche had to learn these systems (including the art of social dining and entertaining) and the proliferation of published household manuals, menu books and cookery texts subsequently produced are useful sources for researchers today (e.g. Anon. 1857; Beeton 1861; Pierce 1857).

Colonial development grew rapidly in New South Wales and Victoria after the discovery of gold in the 1850s. New townships were established and roadways and rail networks expanded, and once-remote properties became better connected to supply services, lessening the need to be self-supporting. Artificial refrigeration meant fewer people needed to salt down large quantities of meat or make bread, butter and cheese. These, along with fresh meat, could be purchased on regular trips to town or delivered on regular bases, meaning that householders could manage with pantries, food-safes and, in warmer months, ice chests. The reduction in the number of servants in households was another contributing factor in these service rooms and the work performed in them becoming redundant. As a result, many service wings and outbuildings were demolished or repurposed, and kitchens were integrated into the main part of the house, offering more convenient access to dining areas and allowing closer connection and interaction with social and family activity. This had been standard practice in smaller and more modest houses that operated without dedicated service rooms and in many cases, without household staff. In many historic houses that are now museums, surviving kitchens and servants’ spaces are used as reception areas, administrative offices, refreshment rooms, and, less-so, as bathroom facilities (Shanahan, personal communication, 2022). This indicates how little value these working spaces have been given when interpreting historic houses, compared with the often grander living areas.

Simple kitchens

In smaller and more modest households (which does not necessarily mean small numbers of residents) equivalent procedures to those outlined above took place in modified forms and at reduced scales, the duties generally performed by family members rather than servants. A “tuckerbox” and a mesh-sided food-safe set against a south-facing wall in the kitchen or veranda may be all that was necessary for protecting dry-goods and perishable foods from heat, light, insects and vermin. Tin boxes with perforated sides, hung from a hook to catch the breeze, acted as a mini larder for small households.

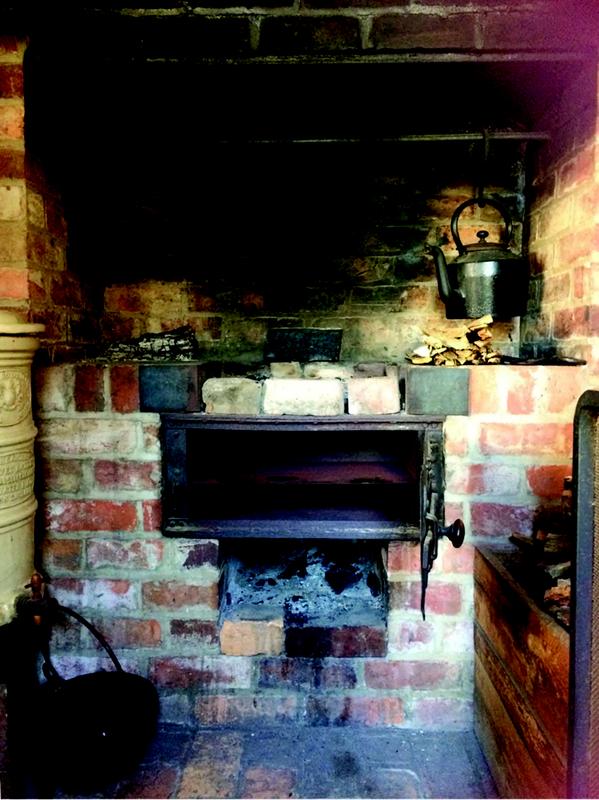

Even humble cottages sported fireplaces and sometimes bread ovens made of brick or stone, clad inside and out with mud or clay – for example, Calthorpes House and Mugga-Mugga Cottage, both in Canberra (see also Baglin and Baglin 1979). Alternatively, small bread loaves, buns and biscuits could be cooked in a portable “American” oven. Essentially an open-faced, three-sided box made of reflective tin with a tray shelf or two within, which could be set in front of the hearth-fire at the appropriate distance for the job (see Acton 1855, 164; 1857). Bread could also be made in a “Dutch” oven, an iron pot distinguished by a closely fitted flat lid with raised sides upon which coals could be piled, while the body of the pot was nestled into the coals of the hearth fire to bake. In urban areas, bakeries not only supplied bread, but following an age-old tradition, also baked pies, pastries and meat that customers brought in ready-prepared for cooking, for a small service fee. Households could therefore manage without an oven and/or avoid the discomfort of using a hot oven in the summertime.

Some householders, even when living in towns where milk could be bought, kept a milch-goat. They were hardy animals that were cheaper and easier to feed and required less space than a cow. Goat-milk could be processed into cottage-style cheese but is not ideal for butter making. Butter might therefore be bought in, or homemade from purchased dairy cream.

Other daily needs – dry-goods, meat, fresh fruit and vegetables (if not grown at home) – could also be purchased from local grocers, butchers and street vendors. Buying small quantities at regular intervals eliminated the need for extensive storage space. Some houses had a basement and/or cellar store, however they were often used to store coal rather than food.

Perishables (and drinks) could be kept cool for short periods of time in lead-lined “sarcophagi” or cheaper tin-lined “refrigerator boxes”, insulated with tightly packed straw or sawdust. A predecessor to today’s chillybin or esky, they were cooled by filling with cold water drawn from a deep well. It was also common practice to chill drinks, set jellies and moulded creams by suspending them in a bucket just above the waterline in the well, where it was coldest. Commercial manufacture of ice began in the 1850s but it took some time for the industry to benefit householders. Domestic ice chests were available from the 1860s but they were costly to buy and only useful for those who could access and afford regular deliveries of ice, which remained a concern for decades (Muskett 1893, 59). The obvious benefits of domestic refrigeration saw the rapid development of icemaking technology. Iceworks were quickly established in regional towns, and newspapers featured instructions for making homemade iceboxes for food storage. Rural households were clearly disadvantaged until kerosene-powered refrigerators became available in the late 1920s. For many householders, a refrigerator was a significant purchase, and ice chests were still in demand in the 1940s.

Artificial lighting

Improvements in artificial lighting changed the way people ate and cooked. Due to the cost of clean-burning candles or whale oil, only wealthy people could afford to light their dining rooms at night. Their kitchens were often lit with cheaper tallow, which was greasy and smoky. For the majority of people, the main meal of the day took place at lunchtime, to make practical use of daylight as an economic measure, and to take advantage of the cooler hours of the morning for hot and laborious work. Supper, or “tea” as it was known in some households (not to be confused with the beverage, though tea may be served with the meal) was a quickly-cooked affair, perhaps leftovers from the day’s main meal, or for some, bread and cheese. Even the middling or leisure classes who had staff to cook for them took dinner during the day, and a simpler, though similarly styled, evening meal of fewer courses (for detailed study on mealtimes and social status see Lehmann 2003).

Gas lighting was increasingly adopted in private homes from the 1870s (in metropolitan areas), and evening dining became prevalent for “white collar” workers whose workdays followed set operating hours. Their children may have eaten at an earlier hour. For those who did not have money to burn either candles or gas, workday meals were taken according to the demands of the day. Factory or retail workers might come home for lunch if practicable, as might schoolchildren, but for many, the hot meal of the day, which may be relatively simple, was now taken in the early evening. Stories abound of the lights going out mid-meal in homes that used coin-operated gas meters in the early 1900s, and the scramble to find pennies to reactivate the service. Sunday was often reserved for a more formal family meal, often a lunchtime or evening roast, when the meal could be prepared in daylight hours if necessary, and the family could spend more time at the table.

Local adaptation

If not within the living area of a dwelling, the kitchen was almost invariably at the rear of the house or beneath the house in the basement. Quite often, kitchens in the colony were in a detached building. Risk of fire spreading into formal areas is the common tropos, but as Clara Aspinall explained, “Kitchens are detached from the houses, to keep the latter as cool as possible” (Aspinall 1862, 102). A separate kitchen also minimised the likelihood of noise, cooking smells, greasy smoke and steam permeating the living areas. For basic hearth-side cookery, a chimney that functioned properly would draw heat and smoke up from the fire, the constant draught preventing the kitchen from overheating (Baglin and Baglin 1976, 7). However, enclosed iron ranges and ovens were designed to hold heat and would almost certainly raise the ambient temperature of the kitchen. As warm air rises, they would also warm the room/s above.

Some houses, such as Elizabeth Bay House (now a museum) in Sydney, had two kitchens – one in a detached wing at the rear of the house and the other in the basement, conveniently installed underneath the family room, which would benefit from passive heat emanating from cooking activity below. The skeletal remains of the basement kitchen and other service rooms survive in the house; however, the detached wing was demolished to make way for a road and building development in the 1930s.

At Susannah Place, a row of four “two up, two down” terrace houses built in 1844 in The Rocks in inner-Sydney (now also a museum), the original kitchens were in the east-facing basements. In three of the four houses, the kitchens were relocated to the ground floor, providing easier access to living areas and better light. In two of the houses, enclosed balconies added later in the century became make-shift kitchens. This was made possible with the advent of free-standing gas or electric cookers in the early 1900s, thus freeing up the original back room for living space. In the wintertime, however, some tenants chose to cook with the iron range that remained in the back room fireplace, which warmed the house as well as producing a hot meal. These examples demonstrate the ways that residents adapted British-designed houses to suit the local environment for comfort and convenience.

The uses of and necessity for the spaces outlined above evolved quite rapidly through the second half of the nineteenth century. Technological breakthroughs can be dated to particular decades, but by no means were they uniformly available or adopted. Whether and when traditional methods were replaced by new, more industrial ones depended on location, financial means and personal preference, however most were obsolete by the mid-twentieth century. Many of the products and processes these spaces facilitated have been outsourced to commercial and usually industrialised providers. Some of the foods produced in these spaces have become all but lost. Domestic freezers have made ice cream a household staple but chilled desserts such as blancmange and sago pudding have disappeared from family menus. Similarly, deli-bought charcuterie has replaced home-cured meat. While timesaving for cooks, these changes have altered our relationship with food by distancing us from our food sources and the knowledge and skills involved in food production and preservation. More familiar might be basic cooking methods suggested in the title of this chapter, that were employed primarily in the main part of the kitchen, which centred around the fire or stove.

Part two: cooking methods

The transference of heat is recognised as the principal cooking medium, and is the main focus of this second part of the chapter, which moves from open hearth cookery to manufactured iron ranges. There are three basic means of heating food – radiation, convection and conduction – which manipulate the molecular composition of the food. Their reactions are often facilitated by added water or fats. Grilling, broiling and roasting expose food to radiant heat. Boiling, simmering and steaming are forms of convection using heat conducted through water or vapour. Deep-frying also uses convection by immersing food in oil, while pan-frying or sautéing use conducted heat from an oiled pan. Baking uses both air convection and radiated heat (McGee 2004, 780–7).

Open hearth cookery

The vacant cavities so often seen in historic houses and museums, perhaps displayed with an inchoate array of old cooking implements, belie the versatility the original hearth fire offered. In the hands of a competent cook, and with the right equipment, all forms of cookery (grilling, roasting, steaming, frying, etc.) could be achieved with this single facility – regardless of whether it was part of the living area or in a designated kitchen. A variety of pots, pans, griddles, plates and grid-irons could be placed in, on or in front of the fire, or over it, suspended from an iron bar fitted across the inside of the fireplace beneath the chimney. Some fireplaces featured a safer and more convenient crane attached to the side wall. A hinge allowed the jib-arm to swing out so that cooks could tend pots suspended from it, without reaching over the fire. Cooking temperatures were controlled by manipulating exposure to the heat. This could be achieved by adjusting the number of hooks or length of chain that held the cooking vessels, changing their distance above the fire. Many recipes instructed that food should be cooked “before the fire”, that is, in front of the fire itself, to cook from the radiant heat rather than directly over a flame. Pots could be placed directly on the hearth or raised up on a stand or trivet.

Frying and sauteeing

A secondary cooking area could be created for delicate dishes by scooping some coals from the fire onto the outer hearth or kitchen floor, over which a grid-iron would be placed to support a pot, sauté pan or earthenware chafing dish. Better equipped kitchens featured a separate structure with cavities in which small fires could be set. These “stewing stoves” had been used in England since the early sixteenth century. By the 1800s, they were fitted with iron fire baskets to hold the hot burning coals, over which trivets were placed, acting as hobs. When not connected to a flued chimney system, these stoves would ideally be positioned near a window or well ventilated part of the kitchen to minimise the risk of toxic fumes being emitted, especially when manufactured coal came into use. These small, fuel efficient hobs had the benefit of individual heat control and could be lit for small or delicate quick-cooking dishes such as omelettes or sautéed offal – ideal for breakfast or light suppers. With the use of a grid-iron, fish or steaks could also be grilled without the need for the main fuel-hungry fire. Expansive banks of hobs can be seen in kitchens at Kew Palace near London and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Virginia, USA (Figure 7.1), and a smaller example with three hobs remains in the basement kitchen at Elizabeth Bay House in Sydney.

Figure 7.1 The kitchen at Monticello, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA, showing clockwise from left: a bank of stewing stoves, set kettle, fireplace with crane, roasting jack on the wall above, and beehive baking oven (closed). Photo: Jacqueline Newling 2018.

Roasting

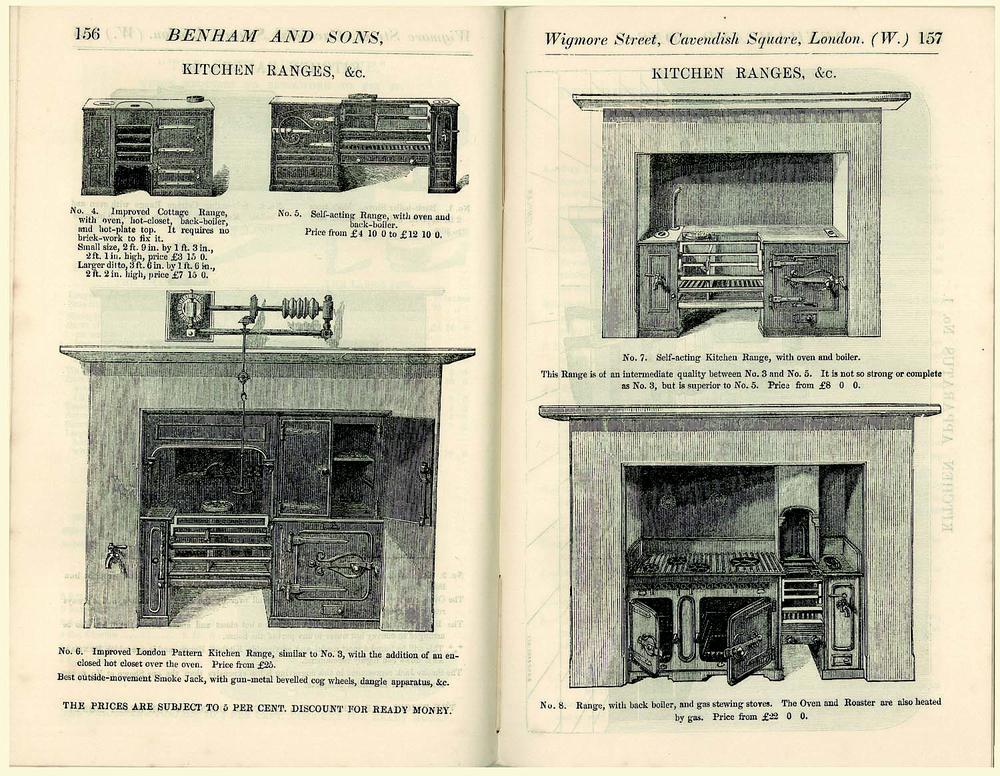

The traditional English-style roast dinner maintained in many Australian households today is not typical of the roast enjoyed by our forebears before the mid-nineteenth century. True roasting is a form of radiant heat, transferred to food by direct exposure to the fire. A spit positioned across the front of the fire, from which large cuts and “joints” of meat or whole birds were roasted, could be turned manually to ensure even cooking. In more sophisticated setups, spits were driven by mechanical means using a “smoke-jack” generated by hot air drawn up into the chimney that worked gears which rotated the spit-bars (an early mechanical spit can be seen in Figure 7.1, and a more sophisticated example in illustration “No. 6” in Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Benham and Sons (1868), illustrated catalogue. London: Benham and Sons.

Caroline Simpson Library Collection, Museums of History NSW.

Even without these fittings, meat could be roasted in front of the fire using a “dangle spit” formed by cords or chain suspended from the mantle above the fireplace. The cords would be twisted and tensioned periodically by the cook, allowing the meat attached to spin around as the cord unfurled. Brass and japanned tin “bottle jacks”, advertised for sale in the colony from at least 1816, automated the process somewhat by means of an internal key-wound mechanism that turned a spool which the meat hung from. A bottle jack is one of the implements recommended in Isabella Beeton’s Book of Household Management in 1861 (Beeton 1861, 31). A depiction of an “Australian kitchen” in 1880s editions of Beeton’s tome shows a cook tending a roast suspended from a bottle jack with a drippings tray below (Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Australian kitchen, Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (c. 1888, 1256). London: Ward, Lock and Co. Rouse Hill Estate Collection, Museums of History NSW.

A pan positioned beneath the joint caught rendered fat and meat juices, which could be used to baste the meat, or to cook roast potatoes or Yorkshire-type puddings in the drippings. Additional economy could be achieved by a freestanding “tin kitchen” or “tin roaster” positioned in front of the fireplace, its reflective tin-plate providing extra radiant heat as the jack rotated. These could be homemade or manufactured (see for example, Benham and Sons 1852, 74). Bottle jacks appear in household auction lists in the 1860s, but an 1868 article in a regional newspaper suggests that the apparatus was by then quite novel for Australians living outside the metropole, if not more broadly, “as it is an almost universal custom … to bake [meat] in an oven” (J.P. 1878, 18). It appears, therefore, that the 1880s edition Mrs Beeton was wryly mocking life in the Antipodes, suggesting that people were using antiquated technology.

Boiling

Many Australians would be aghast at the thought of boiling a leg of mutton, even more-so a calf’s or pig’s head or ox-tongue, but these were popular dishes even in early twentieth-century Australia. Tongue and calves’ heads were quite prestigious, sheep derived alternatives less-so. Pigs’ heads were also boiled to make brawn. Boiling of such food items was done in large oval-shaped iron cooking pots which are now often seen in museums and antique shops.

Boiling, which in historical cookbooks could also mean lower temperature simmering, was available to anyone with access to a heat source and a watertight vessel that could withstand direct exposure to heat. Lightweight and versatile, the now iconic Australian “billy” or tin “kettle” was ubiquitous for more than a century before Banjo Patterson wrote “Waltzing Matilda” in the 1890s. Synonymous with camp fire cookery, they could be nestled in hot coals, and when fitted with handles could be lifted from the fire with a stout stick, or suspended from a tripod or a rod supported by a frame. Heavier and more durable was the round-based cauldron-style iron pot, usually equipped with three small feet so it could stand on the ground without rolling about.

A great variety of dishes can be made in such kettles and pots, including soups, stews and grain-based gruels (often maligned but porridge and congee are still readily consumed today). Nutrients are retained in the cooking liquid, which could be served as broth, or thickened with rice, barley, stale bread or biscuit.

Cloth-boiling

Cloths were used to bundle up a variety of sweet and savoury foods to boil for puddings. Christmas plum pudding is probably the best known survivor of this style of cooking in Australia, but pease pudding was made with dried split-peas, and hasty puddings were made with flour and suet, sometimes enriched with fruit (“spotted dick” style). The technique was popularised in the late eighteenth century and almost exclusively limited to the British culinary diaspora, including Australia (see Leach 2008). A savoury pudding could be boiled in the pot with the meat and vegetables with which it would be served, adding flavour to the pudding and to the cooking broth, which might be served as soup. A miniature form of flour-and-suet pudding remained in the repertoire as dumplings, which were boiled without a cloth in stews towards the end of cooking. This was an economical way to add substance and texture, thickening the broth and making the dish more filling. Savoury puddings were gradually eclipsed with the increasing use of potatoes as accompaniments to meat dishes, as they were easier and quicker to cook, and more versatile (Wilson 1973, 217–18).

Steaming

With Christmas plum pudding perhaps the exception, basins have largely replaced cloths for steaming puddings, being easier to serve from and to clean. The basin could be lined with pastry, filled with meat and gravy and covered with a pastry top, sealed with a plate, and steamed, semi-immersed, in a pot of boiling water. A “sea pie” could also be made in a kettle or iron pot with or without a basin, by covering a prepared stew with a layer of dumpling dough which formed a scone-like crust as the pie simmered in a well-sealed pot.

Casserole-style dishes could also be made without an oven, by filling a glazed earthenware jar with prepared meat, vegetables and herbs, sealing it tightly with a “bung” of cork or leather and setting the jar in a pot of water to simmer for several hours. This technique was known in the nineteenth century as “jugging” but in Australia the term “steamer” was adopted, as the ingredients steamed in their own juices. The kangaroo or wallaby steamer, layered with salt-pork or bacon and flavoured with onions, aromatics and port wine, is a localised version of the older English jugged hare (Santich 2012, 39). In The English and Australian Cookery Book for the many as well as the upper ten thousand (1864), the name steamer was retained but the dish was cooked in a saucepan, in the same way as a stew. The book includes three versions of the kangaroo steamer, one which could be preserved “for twelve months or more” by packing the cooked steamer tightly into an “open-mouthed glass bottle; the bung … sealed down, and the outside of the bottle washed well with white of egg, beaten” (Abbott 1864, 83). When required for eating, the jar was boiled in a pot for half an hour to reheat. Glazed earthenware jars were also used to make more delicate melted butter sauces, egg dishes, milk puddings, custard and fruit “cheese” (lemon curd-style) in the way that we might use a double boiler. They were also used to reheat delicate dishes, to prevent them scorching or sticking to a metal pot.

Water “on tap”

Before clean potable water was plumbed into homes, water filters, coolers and “fountains” were common domestic features. Large hand-hewn limestone dripstones from the early–mid nineteenth century, through which water was poured to remove impurities, can be seen at Vaucluse House and Elizabeth Farm (also a museum, near Parramatta). Smaller, sometimes decoratively designed, ceramic water dispensers fitted with filters and a tap near the base (much like modern versions) also helped keep drinking water cool (see for example Anthony Hordern and Sons Ltd general catalogue, 1914, 636). For hot water, large iron kettles sealed with a lid and fitted with a brass tap near the base were almost permanently suspended over the hearth fire for a ready supply. These vessels eliminated the need for a “set kettle” which were once a fixture in kitchens that serviced large households (see Figure 7.1). Akin to the “copper” commonly associated with laundries, they were set into a mud-and-stone or bricked surround adjoining the main fireplace, so that the fire beneath the structure that heated the copper could be vented into the chimney. The presence of a set kettle can lead to confusion as to whether the room was a kitchen or laundry, as they were used in both facilities. The room the Swann family used as a laundry at Elizabeth Farm in the early 1900s also has a substantial open fireplace, and evidence of an oven cavity that was bricked over at an unknown time, suggesting that the room was previously a kitchen.

Bread baking

Bread ovens with domed or beehive (skep) shaped interiors were often installed next to the cook’s fire in the main kitchen, with the oven’s flue connecting into the chimney. Good examples remain in Culthorpe’s Cottage, the detached kitchen of Mugga-Mugga in Canberra, and 10 Quality Row at Kingston on Norfolk Island (all now museums). Archaeological remains have been reconstructed in the 1820s kitchen at Parbury Ruins, Millers Point, Sydney. At Rouse Hill House in north-western Sydney, the bread oven (c. 1855) is separate to the kitchen, built into a wall in the service wing, while some properties, such as Brickendon in Longford, Tasmania, have a dedicated bakery building – in this case adjoining a smokehouse (Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners 2008, 62, 67).

Beehive ovens work with radiant heat, held in the oven’s internal brick lining. To heat the oven, a fire is lit inside and the door is left open, for airflow and to draw away any smoke, which is generally conducted up through a flue positioned in front of the oven door. Once the oven has reached the desired temperature, the coals are raked out and the oven floor swept with a damp broom. Only then is the door closed, trapping the heat within. An experienced baker knew the temperature of the oven by how quickly a handful of flour browned when thrown onto the oven floor, or, less safely, by the length of time they could hold their forearm in the oven. It could take up to two hours to reach bread-baking temperature, but once heated, the oven could retain its heat for several hours, and a series of dishes of varying types, from pies to meringues and delicate custards, could be cooked in the residual heat (Nylander 1994, 197–8; for detailed explanation about bread baking and types of apparatus available in the mid-1800s, see Acton 1857). A nineteenth-century innovation was the “Scotch” oven, where heat was drawn from a firebox set into a smaller chamber next to the baking oven, eliminating the need to set a fire inside the brick oven and rake out the coals (Haden 2006, 61–73). This style of oven – several of which are still in use today in regional towns in New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria – was used for commercial baking rather than domestic situations.

Enclosed and semi-enclosed range cookery

Open hearth fires and beehive ovens are fuel hungry, and in places where wood was scarce, particularly in metropolitan areas, coal had to be purchased. Manufactured “ranges” for fireplaces were in use in England from the late 1700s, but became more commonplace and increasingly elaborate as the nineteenth century progressed (see for example, General Iron Foundry Company Limited catalogue, 1862).

A relatively simple cooking range may comprise two vertical side panels, often in the form of water tanks, which were heated by the fire set between. An iron fender or crossbars were positioned in front of the fire between the panels to prevent coals falling out, and adjustable “cheeks” – flat plates of iron – could be moved inwards to create smaller fire-beds. Swivelling trivets affixed to the vertical plates allowed vessels to be moved over or away from the fire. Open exposure to the central fire allowed for roasting from some form of jack, as discussed above.

The absence of an inbuilt oven in these type of ranges suggests that they serviced kitchens with separate baking ovens. These were not necessarily brick beehive ovens, more often small pastry ovens, in the form of an iron box set into a cavity in a wall beside the fireplace, with its own small fire space and ash-pit below. Such is consistent with the setup at Elizabeth Bay House. Heat could circulate around the oven and any smoke from the fire was drawn into a flue behind or to one side of the oven and vented into the main chimney. Though a poor substitute for a brick beehive bread oven, they were suitable for baking small “cottage” loaves and soda bread, tarts, pies, and small batches of rolls, buns, scones and biscuits.

More compact semi-enclosed “self-acting”, “cottage” or “cottager” ranges offered an open-faced fire for roasting, albeit of smaller scale, and retained features such as adjustable cheeks and swivelling trivet (Figure 7.2). A boiler or water tank was generally on one side of the fire, and on the other, a pastry oven. An early example dating to the mid-1840s survives at Vaucluse House. The oven can be lit from below as well as receiving heat from the central fire. Later models had the advantage of a flue system that conducted heat behind the oven, and by the 1860s, the ovens featured inbuilt plates that could be rotated to enable even cooking.

These multi-function appliances could be installed in existing fireplaces, replacing hearth-fire cookery. Publications from the 1860s indicate that this style of range remained in use for some time, even though more advanced models such as the Leamington Kitchener, which took the first prize and medal at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, were available on the market (General Iron c.1862, 18; Benham and Sons 1868, 146, 157, 160). Originally imported from Britain or America, they were costly for some householders, but an increasing number of local foundries made them more affordable.

Much simpler and less expensive was the basic iron box oven (Figure 7.4). Available from the 1840s, they were fully enclosed and easy to install. Colonial illustrations and museum reconstructions show the box oven variously heated from above and below, the chimney drawing away any smoke from behind the box.

A fire set on top of the oven provided a heat source for vessels hung directly over the fire, or an iron sheet could be positioned above the fire as a hotplate, supported by bricks on either side of the oven-top. Examples include S.T. Gill’s 1857 depiction of the kitchen in Monsieur Noufflard’s house in Sydney (Historic House Trust of NSW 1983), Frederick McCubbin’s (1896) Kitchen at the old King Street Bakery and Hardy Wilson’s (c. 1920) Kitchen and fireplace at Berrima. Similar setups can also be seen in the basement kitchen of 64 Gloucester Street at Susannah Place, The Rocks, Sydney; the Commandant’s House, Port Arthur, Tasmania; and as shown in Figure 7.4 at Sovereign Hill in Ballarat, Victoria.

Figure 7.4 Iron box oven in a recreated cottage kitchen at Sovereign Hill, Ballarat (hotplate not shown). Photo: Jacqueline Newling 2019.

Oven “roasting”

Today, a traditional “roast” dinner is generally baked in an oven rather than true roasting, where meat is directly exposed to a flame. Offering detailed advice on dressing and tending meat to assure the best possible outcomes and circumventing common mistakes when roasting, cookery authority Eliza Acton (1855) conceded that the technique “requires unremitting attention on the art of the cook rather than any great exertions of skill” (157–9). While suitable for cooking various types of fish, pork, ham and pickled beef if well-covered with a “course paste” or layers of buttered paper, she deemed oven-baking “both an unpalatable and an unprofitable mode of cooking joints of meat in general” (Acton 1855, 165). Nonetheless, she recommends that when oven-baking, meat should be raised from the baking dish by placing it “properly skewered, on a stand, so as to allow potatoes or batter pudding to be baked under it” (Acton 1855, 165).

Acton does, however, advocate other types of cooking in the domestic oven, generally of the more delicate kind, through “slow oven-cookery”. With enough cooking liquid, calf’s feet, rolled heads and soup bone reductions could be effectively made in the oven. Cooking in a jar (casserole-style) with its lid “well pasted down, and covered with a fold of thick paper” was deemed ideal for rice “slowly baked with a certain proportion of liquid, either by itself or mingled with meat, fish or fruit” (Acton 1855, 164). Similarly, oven-braising, where meat dishes prepared on the stovetop are transferred into the oven to finish cooking in a sealed dish, is offered as an alternative to stewing (Acton 1855, 165). In effect, these techniques could replace boiling, jugging, steaming and stewing on a stovetop, relieving the need for the cook to ensure their pots would not boil dry. For safety, comfort and fuel-economy, roasting before a fire eventually gave way to baking in fully enclosed ranges.

The range of techniques employed by a cook would depend on their taste and skills (often derived from their social background or habitus, training or work experience), available time and financial means for requisite ingredients and equipment. Trade catalogues and some cookery texts provide extensive lists of equipment, or batterie de cuisine, but a variety of dishes and meals could be produced with a relatively few implements. English chef Alexis Soyer advises in

A Shilling Cookery for the People (1854), that “nearly one half of the receipts” in the book could be “cooked to perfection” with a “[sauce]pan, grid-iron, and frying pan” (Soyer 1854, 174). A stove with oven and boiler was highly recommended. The lists of kitchen requisites in Beeton (1861, 31) and The Commonsense Cookery Book (NSW Cookery Teachers Association 1914) hardly vary in terms of pots, pans and basic utensils, but absent in the twentieth-century text is the need for a cinder-sifter, coal-shovel and bellows, which were necessary for hard-fuel cooking apparatus. Regardless, kitchens large and small provided numerous options for people to adapt their tastes and needs to the resources at hand, whether plentiful or constrained. As culinary artefacts, the scope and potential of historic kitchens can only be fully appreciated as the sum of their many parts, assemblages that include elements that are not materially evident.

Conclusion

Over time, kitchens have become safer and healthier spaces, and generally better integrated into the social areas in the home – coming the full circle if we consider small houses where the kitchen was part of the eating, working, recreational and sometimes sleeping area. Cooks continue to prove themselves resourceful and creative, adapting to changes in technology, and taking advantage of improved access to and affordability of an expanding variety of ingredients, education and health advice, and greater exposure to other cultures’ cuisines and cooking styles.

Recalling the phrase, “the past is a foreign country: they do things differently there” (Hartley 1953), this chapter has attempted to fill in some of the gaps in reading and interpreting a colonial kitchen by illustrating some of the intangible aspects of large and small kitchens in culinary and social contexts. Much of the cooking we do today would be recognisable to colonial cooks – a baked dinner may have replaced the roast, but the barbeque is not a distant stretch from the grid-iron or spit, with direct exposure to a flame. Our forebears may be surprised that we are more likely to own a wok than a pudding cloth. We can assume they would envy the ease with which we can heat our stoves, and the relative speed at which we can prepare a meal. Even when we think we are cooking “from scratch”, the food we purchase is partly or fully processed – cleaned and gutted, free of feathers and scales, and increasingly, skinned, deboned and filleted, perhaps marinated. Cuts of meat are smaller, as are the pots and pans we use to cook them (which also reflects a reduction in the number of residents in many households). These conveniences have obscured these once-standard operations, diminished our understanding of the processes involved, and our appreciation of the (mostly unseen) labour required for us to eat well. It comes as little surprise that kitchens from the past hold so much mystery for modern cooks and consumers. While attempting to make sense of colonial kitchens as historical artefacts and assemblages, this work by no means reduces the wonder that can be can found in those that survive.

Acknowledgements

This work was prepared on Wangal Country upon which I am privileged to live and work. I acknowledge that this land has never been ceded by Australian First Nations and pay respects to Elders past and present.

Much of my knowledge has been developed during my long-standing tenure at Museums of History NSW (MHNSW), formerly Sydney Living Museums/Historic Houses Trust NSW, as a house museum guide and then curator. This chapter has been produced independently, however, and does not necessarily reflect or represent the views of the institution.

I am indebted to the University of Sydney for travel grants for research in England and Virginia, USA, and Sydney Living Museums for sponsoring further research in America funded by the Ruth Pope Bequest.

I extend my thanks to the anonymous peer reviewers whose advice and recommendations have greatly added to the quality of this work.

References

Abbott, E. (1864). The English and Australian cookery book, for the many as well as the upper ten thousand. London: Samson, Low, Son and Marston.

Acton, E. (2003 [1855]). Modern cookery for private families, facsimile edition.

East Sussex: Southover Press.

Acton, E. (1857). The English bread-book for domestic use. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts. https://archive.org/details/b21531006.

Anon. (1857). The home book of household economy: or, hints to persons of moderate income; containing useful directions for the proper labours of the kitchen, the house, the laundry, and the dairy; including the best receipts for pickling, preserving, home brewing, and also sick-room management and cookery. London: G. Routledge & Co.

Anthony Hordern and Sons Ltd (1914). General catalogue. Sydney: Anthony Hordern and Sons. https://archive.org/details/Hordern15027.

Aspinall, C. (1862). Three years in Melbourne. London: L. Booth. https://archive.org/details/threeyearsinmelb00aspirich/mode/2up.

Baglin, E. and D. Baglin (1979). Australian chimneys and cookhouses. Sydney: Murray Child and Company.

Beeton, I. (1861). Beeton’s book of household management. London: S.O. Beeton. https://archive.org/details/b20392758/mode/2up?

Beeton, I. (c. 1888). Mrs Beeton’s book of household management. London: Ward, Lock and Co.

Benham and Sons (1868). Illustrated catalogue. London: Benham and Sons. https://archive.org/details/Benham14191.

Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners, Pty. Ltd (2008). Brickendon Conservation Management Plan, for Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts.

Delroy, A. (1990). Domestic gas cooking appliances in metropolitan Perth, 1900–1950. Western Australia Museum Records and Supplements, 14(4): 461–81.

General Iron Foundry Company Limited (1862). Drawings of ranges, stoves, pipes, ornamental and general castings made by the General Iron Foundry Company Limited. London. https://archive.org/details/GenIron30636/page/n21/mode/2up.

McCubbin, F. (1896). Kitchen at the old King Street bakery accessed 6 March 2025. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frederick_McCubbin_-_Kitchen_at_the_old_King_Street_Bakery,_1884.jpg.

Hartley, L.P. (1953). The go-between. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Haden, R. (2006). Australian history in the baking: the rebirth of a Scotch Oven. Journal of Australian Studies, 30(87): 61–73. DOI: 10.1080/ 14443050609388051.

Historic Houses Trust of NSW; Shar Jones and Michel Reymond (1983). Monsieur Noufflard’s house: watercolours by S.T. Gill, 1857. https://first.mhnsw.au/#record/4742.

Leach, H. (2008). Translating the 18th century pudding. In F. Leach, G. Clark and S. O’Connor, eds. Islands of inquiry: colonization, seafaring and the archaeology of maritime landscapes, 29: 381–96. Canberra: ANU Press.

Lehmann, G. (2003). The British housewife, cookery books, cooking and society in eighteenth-century Britain. Totnes, UK: Prospect Books.

McGee, H. (2004). On food and cooking, an encyclopedia of kitchen science, history and culture. London: Hodden & Stoughten.

Muskett, P. (1893). The art of living in Australia. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode.

Newling, J. (2021). First Fleet fare: food and food security in the founding of colonial New South Wales, 1788–1790. Doctoral thesis, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW. https://hdl.handle.net/2123/24785.

NSW Cookery Teachers Association (1914). The commonsense cookery book. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

Nylander, J. (1994). Our own snug fireside: images of the New England home, 1760–1860. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

J.P. (1878). The ball at O’Squiffey’s. The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express, 18 May, 18.

Pennell, S. (1998). Pots and pans history: the material cultural of the kitchen in early modern England. Journal of Design History 11(3): 201–16. Oxford University Press on behalf of Design History Society.

Pennell, S. (2016). The Birth of the English Kitchen 1600–1850. London: Bloomsbury.

Pierce, C. (1857). The household manager: being a practical treatise upon the various duties in large or small establishments, from the drawing-room to the kitchen. London; New York: Geo. Routledge & Co.

Rundell, M. (2009 [1816]). A new system of domestic cookery, facsimile edition. Bath, UK: Persephone Books [London: John Murray].

Sambrook, P.A. and P. Brears, eds (1993). The country house kitchen. The National Trust (UK). Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd.

Santich, B. (2012). Bold palates. Kent Town, SA: Wakefield Press.

Shepherd, S. (2000). Pickled, potted and canned. London: Headline Book Publishing.

Soyer, A. (1854). A shilling cookery for the people, London: Geo. Routledge & Co.

Wilson, C.A. (1973). Food and drink in Britain. London: Cookery Book Club.

Wilson, H. (1920). Kitchen and fireplace at Berrima [artwork]. National Library of Australia call number PIC Drawer 10571 #PIC/11872/104. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147889358.