6

Pigs, temples and feasts

Australian Chinese pig ovens

Introduction

In the 1970s, historical archaeologists began questioning the function of large cylindrical, stone structures on nineteenth-century Australian-Chinese mining camps. Their possible use as forges or ovens was canvassed widely. By piecing together the physical evidence, oral histories and documentary records, it gradually emerged that many were used to roast whole pigs for elaborate feasts and celebrations. Mouth-watering slices of roast pork and chunks of crispy crackling are popular among many societies and were no less so among the many Chinese who migrated to Australia in the 1800s.

In this chapter I examine the diversity of “pig ovens”, a generic term that is, admittedly, challenged by the existence of some smaller structures which were more likely associated with cooking smaller joints of meat. It describes their form and distribution, considering their social importance and role in religious festivals among one of Australia’s largest migrant groups and how contemporary use of similar ovens has enabled archaeologists to better understand their importance. First, however, attention focuses on the significance of the pig in Chinese history and culture.

Pigs have long played an important role in Chinese heritage not only for their nutritional values, but in relation to religious rituals, astrology and social events. The pig is considered to be a symbol of virility, is the last of the 12 Chinese zodiac signs and is included in the list of the “six domestic animals” – along with the horse, ox, sheep, dog and chicken (Eberhard 1993, 236). As a further indication of the pig’s importance in Chinese culture, there was a “God of the Pigsty” whose origins are lost in the mists of time, but whose role was to ensure a farmer’s stock grew fat and healthy (Wang 2004,130).

As far back as the Chinese Neolithic period (10,000–2,000 BP) archaeological and historical records indicate that pigs were not only domesticated but also held important roles in the socio-cultural environment of that period. Pig skulls associated with Neolithic burials indicate a close association with this important domesticate (Seung 1994, 124). Pictographs from Wei Jin Dynasty (c. 221–317 AD) burial sites near Jiayuguan, Gansu Province, China, include one of a pig being prepared for cooking (Figure 6.1), offering archaeological evidence of the importance of pork in that period.

Figure 6.1 Wei Jin Dynasty (c. 221–317 AD) pictograph showing a pig being prepared for cooking. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2012.

It is probable that the role of pigs in folk religion gradually evolved to manifest into a central role in ritual feasts. Chinese religion is a rich amalgam derived from Daoism, Buddhism and Confucian philosophy into which folk religion is inextricably interwoven (Grimwade 2024, 4). In the process, the practical attributes of pork as a nutritional source has been integrated into religious festivities.

Quite how humans discovered the delights of eating roast pork is lost to antiquity, and, although it is avoided by Muslims and Jews, no one can dispute its widespread popularity in regions as far apart as China, New Guinea and Europe. Nineteenth-century essayist Charles Lamb’s fanciful A Dissertation upon Roast Pig jestingly suggests that accidental pyrotechnics led to the discovery of roast pork. This folkloric presentation suggests Bo-bo, a Chinese youth, burnt down the family home along with the pigsty and its occupants. Bo-bo was attracted by the aroma of roasted pork and sampled the meat, which hitherto had always been eaten raw. He was gorging himself when his irate father, Ho-ti, returned home but whose furore turned to pleasure when he too sampled the roasted flesh. Subsequent dwellings met with similar conflagrations each time the sow farrowed, resulting in father and son being brought before the court. Officials sampled the meat, agreed that “burnt meat” was indeed a new-found delicacy and discharged the duo. In time, it was decided that it was not essential to destroy the family home each time and, eventually, more acceptable cooking methods were adopted. Perhaps roasting meat was indeed an accidental discovery but there is no argument with the well validated claim that pork is one of the most popular foods in Chinese cuisine.

Chinese migrants flocked to Australia in the nineteenth century and, whilst most sought gold, others saw opportunities in commerce and horticulture. They brought many important aspects of their culture to Australia, and inevitably, this extended to their food and foodways. Rice was a staple commodity and was imported along with preserved spices, ginger, teas, soy sauce and pickled vegetables packaged in a diverse range of ceramic jars and crates, the remains of which are frequently encountered during archaeological excavations. Fresh vegetables, including spinach, cabbages, carrots and celery, were essential to maintaining good health and their production led to market gardening becoming a major source of employment. In many cases, pigs and chickens were also reared to provide both essential protein-rich food and manure for fertilising the crops.

Chinese culture and world views differed markedly from those of both Aboriginal peoples and European migrants which, inevitably, led to discrimination, vilification and the development of what we now refer to as “Chinatowns”, segregated settlements in which Chinese people were the dominant occupants. English language newspapers frequently reported on Chinese festivities and celebrations in which roast pork featured. Those reports were often derogatory, but tinged with curiosity, as they highlighted events and customs that were alien to contemporaneous British Australian practices.

In parts of China, full-grown pigs were roasted in a preheated woodfired oven to produce wonderfully flavoursome meat and crunchy crackling. This was enjoyed by revellers at religious festivals and special events – highlighting the cultural significance of pork in feasting. Archaeological and historical evidence demonstrates that Chinese migrants took this technique with them when they migrated around the Pacific Rim during the nineteenth century. The ovens they built have, in some cases, remained near intact (Figure 6.2), subsequently puzzling late twentieth-century archaeologists who first contemplated their use. In order to better understand their purpose, researchers have been fortunate in being able to document and analyse contemporary cooking practices and to interview older Chinese people and their descendants who could recall how their forebears used the ovens.

Figure 6.2 The remains of a ramped oven in the Palmer Goldfield, Queensland. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2007.

Stone pig ovens once featured in the Australian landscape from north-east Tasmania, east to Perth and north to Pine Creek, Northern Territory, and across to Cape York, indicating a widespread association between pig roasting and Chinese colonial settlements. The human and physical resources needed to construct ovens capable of roasting an entire pig are as important as the knowledge of how and why they were used. In simplistic terms, stone ovens are just man-made structures, but when considered in association with their morphological diversity, tools, cooking processes and the allied rituals, they take on a much greater role within the Chinese diaspora.

Pigs in history

Charles Darwin (1868) classified pigs as either Sus scrofa or Sus indicus. More recent genetic research suggests that there are in fact upwards of sixteen subspecies (Ruvinsky and Rothschild 1998 quoted in Giuffra et al. 2000). Modern pigs are descended from the Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa) and have been domesticated for some 9,000 years; a practice that probably evolved in the Near East (Giuffra et al. 2000, 1785). The domestication process is closely related to the early evolution of humans from hunter and gatherer to horticultural and agricultural societies. While Chinese pigs developed their own characteristics, there is little evidence to suggest Chinese migrants experienced any significant challenges in adapting to locally-available domesticates when they arrived in Australia.

The crossbreeding of Asian and European pigs increased during and after the eighteenth century, no doubt associated with expanding trade and mobility. It is well established that pigs were carried on both merchant and some naval vessels, released in remote locations and allowed to colonise regions as feral animals (see, for example, Clarke and Dzieciolowski 1991). Their proliferation as breeding stock to sustain mariners has led to widespread detrimental environmental impacts (Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities 2011, 1). Pigs were introduced to Australia with the arrival of the First Fleet; escapees from that and subsequent importations are blamed for their proliferation in the wild, while there are suggestions that feral pigs may have been introduced to Cape Yorke via Papua New Guinea (Baldwin 1986) and that domestic pigs were released when the Coburg Peninsula, Northern Territory settlement was abandoned in 1849 (Bengsen et al. 2017). Market gardeners often kept pigs and chickens not only for food but for fertilising their crops. There is no evidence to indicate the Chinese sourced feral animals for cooking given that domesticates were widely stocked.

Along with the spread of pigs, a fascinating divergence of cooking techniques has evolved among those who now regard pork as a staple food (Brown 2017). Modern Chinese pork dishes reflect diverse cooking styles. Shih Tzu Tou from the Shanghai region blends lean pork, water chestnuts and ginger, along with spinach. Belly pork, black beans, tomato and ginger are core ingredients for twice cooked pork, Hui Kwo Juo, in Szechuan, while barbecued spare ribs, Kao P’ai Ku with an enticing mix of sauces, is a popular Cantonese dish (Morris 1984). Ground ovens (hangi [Maori], kup marri [Torres Strait]) are common among Pacific nations. Meat, yam, sweet potato and other vegetables are wrapped in banana leaves or – nowadays – aluminium foil, placed in shallow pits lined with pre-heated rocks, covered with damp sacks and sealed with earth to retain the heat – producing a mouthwatering meal within a few hours. In western societies, the rotisserie, or spit roast, is a popular method of roasting a suckling pig while others resort to the time-honoured oven-roasted joint of pork.

Almost every part of the pig was used, highlighting its economic significance beyond just food. As Ka Bo Tsang (1996, 53) has noted, not only was pork a source of protein, but the fat could be “burned in lamps; pig bristles could be made into brushes; pig skin provided raw materials for shoes and garments and its manure could be used as fertilizer”.

In colonial Australasia, pork was the most favoured protein source for Chinese communities (Ritchie 1986, 600; Adamson and Bader 2013). There are colourful accounts of Chinese feasts and religious festivals in which whole roast pigs loom large. Few, however, detail the method by which the pigs were actually cooked. Festivities at Peters, Barnard and Co, Launceston, Tasmania (importers and general storekeepers), included “a pig roasted, and placed upon the table whole in a large trough made specially for the purpose” (Weekly Examiner 1872, 10). A few months later, at Omeo in the Victorian highlands, a spring celebration included a banquet which was considered “recherché (exotic) in the extreme [where] there were pigs and fowls done to a turn, sufficient to appease the appetite of a fair score of famished bullock drivers” (Ovens and Murray Advertiser 1872, 1). Not to be outdone, festivities in “a building adjoining [the Ararat temple] some dozen more of pigs, several goats, and fowls by the score were undergoing the process of cooking at the hand of professed cooks, who evidently understood their business” (Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser 1873, 4). Feasting reached the dizzy heights of gastronomic indulgence at Emmavale, NSW, in 1887 with “some twenty pigs roasted whole being placed on the floor before the god” (Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser 1887, 959). Some news reports are marginally more informative. The opening of the new temple at Breakfast Creek, Brisbane, Queensland, in January 1886 noted:

Outside [the temple] a number of Chinese butchers were slaughtering and cooking pigs and fowls. There were about a dozen pigs slain, and the bodies were cooked in a large brick oven erected for the purpose in one corner of the ground (Queenslander 1886, 186).

Far to the north, in Cairns, the description of an 1896 feast at the Lit Sung Goong offers further clues about the cooking process:

At the banquet itself fifty-six tables had been laid out, all of which were occupied by eight guests, making a total of 448. In addition to all this, some twenty Europeans, representing the leading men of Cairns, put in an appearance. In order to feed this multitude it was, of course, necessary to make great preparations, and we are informed that thirty cooks were employed in the holocaust of the young spring chicken and the succulent duck; while the great brick oven of the Joss House was laid under tribute in order to roast good sized pigs and other dainties on a wholesale scale (Queenslander 1896, 347).

Pig ovens were capable of processing large amounts of meat relatively quickly so were clearly associated with larger concentrations of population. Cuff (1992) reports swine weights in the United States during the nineteenth century with a 200 lb (90 kg) dressed weight pig being in the upper weight range. There is a subsequent loss of weight with further cutting resulting in a “take home” yield of around 59 kg (based on Hollis 2002). Assuming an average serve of pork per person of around 250 gm, there is thus enough for about 300 people per pig; however, average consumption figures can vary markedly, and such calculations must be considered only as broad indicators. It is interesting to note that it has been separately argued, by “Hum Lee (1960, 58), that 390 people was the critical mass for a viable Chinatown; below this, essential services, such as temples, could not be sustained” (Burke and Grimwade 2013, 124). Pig ovens are therefore likely to be associated with a population of similar size to that necessary to sustain a “Chinatown” settlement.

Feasts attracted large crowds, and it was common for several pigs to be roasted for large events. Social gatherings of this nature, particularly among migrant communities, were not only based on the desire to respect the ancestors but also to draw residents together as a unifying act. The role of the clan or extended family was important, and little expense was spared for many events. The proliferation of food was a source of pride among those who could afford it.

There is no archaeological evidence to indicate what might have happened to any uneaten pork produced for festivals and other celebrations. In the absence of refrigeration, salting or smoking offered the only realistic options for retaining leftovers. Popular modern sources certainly suggest meat preservation techniques were well established in Chinese culture:

Pork is the most common base of preserved meat in China. The legs of the pig are reserved for the more expensive whole hams, and high-quality belly meat is used in making strips of la rou. Fatty and lean meat can be minced and made into sausages, and even the pig’s head can be cured as a whole (Visit Beijing 2023).

Preservation of meat may well have been a practical outcome in areas of greater population, but in remote mining camps frugality and carefully considered outcomes from producing a large roast probably ranked highly.

Pig oven sites in Australia

During the late twentieth century, historians and historical archaeologists were beginning to look more closely at Australia’s cultural diversity and Australian Chinese history in particular. In 1977, Owen Tomlin recorded two “ceremonial ovens’”, one extant and one destroyed; on the Jordan Goldfield, Victoria (Tomlin 1979, 100). Historian Noreen Kirkman (1984, 193) recorded an oven at Byerstown on the Palmer Goldfield (Figure 6.3) in the same year; and, in 1982, Ian Jack and others noted an unusual but “substantial rectangular stone oven” near Lone Star Creek on the Palmer (Jack et al. 1984, 53). Howard Pearce’s 1982 study of the Pine Creek, NT, area was the earliest to describe oven-like structures in that region, and soon after Helen Vivian (1985) noted similar structures in north-east Tasmania.

Figure 6.3 The remains of an oven at Byerstown on the Palmer Goldfield, Queensland. Photo: Noreen Kirkman 1979.

During the early 1990s, additional ovens were recorded across north-east Australia (Alfredson 1988; Bell 1983; Comber 1991; Grimwade 1988, 1990; McCarthy 1986, 1989; Van Kempen 1987) while Ian Jack noted three ovens in New South Wales (Bell 1995, 213). Interest in better understanding the purpose of these unusual structures was clearly increasing. Papers presented at the Conference on the History of the Chinese in Australasia and the South Pacific in Melbourne in October 1993 by Peter Bell, Justin McCarthy and Denise Gaughwin were the first to publicly discuss these reports and to contemplate their function (Bell 1995, Gaughwin 1995, McCarthy 1995).

Bell set about synthesising data that emerged from that conference regarding the existence, primarily on Australian Chinese mine sites, of 46 large domed stone ovens: 19 in the Northern Territory, 16 in Queensland, seven in Tasmania, three in New South Wales and one in Victoria. He noted, “the oddest aspect of the oven’s geographical distribution in Australia is not where they are, but where they are not” (Bell 1995, 223). What was surprising was that the areas where Chinese settlement had been the greatest – Victoria and New South Wales – were underrepresented in the initial inventory. The obvious question, “Why?” was postulated by Bell, who suggested that the use of ovens came after the south-east Australian gold rushes of the 1850s. By 1996, he wrote that ovens were confined to “relatively large numbers on the Palmer and Pine Creek Goldfields, a small cluster on the north-east Tasmanian tinfields, and hardly anywhere else in the country”, further noting that “this is a reasonably complete and certainly representative sample of most of the ovens in Australia, and that the data is not a product of the research methods” (Bell 1996, 15). Since then, however, a wider distribution of oven sites has become apparent.

Several ovens have been identified with links to temples. A single photograph of an oven at Hou Wang Temple, Atherton, Queensland (Figure 6.4) emerged during unrelated research and in 1999, the author recorded another alongside the temple foundations in Croydon in Queensland’s Gulf Country (Figure 6.5) (Grimwade 2003). Soon after, further Queensland ovens had been noted at Ravenswood, near Charters Towers, and there were reports of a long-abandoned oven at Darwin’s temple site. Ovens at Thornborough, on the Hodgkinson Goldfield, Queensland and Woods Point, Jordan Goldfield, Victoria also have possible associations with temples. A decade later Burke and Grimwade indicated ovens were once integral to other regional temples including Etheridge (Georgetown), Innisfail and Port Douglas (Burke and Grimwade 2013, 125). Evaluation of how many of the approximately 150 other former temple sites across the country may have had ovens attached is ongoing, with at least 15 being credibly identified as having ovens.

Figure 6.4 Two European visitors standing at the top of the ramp alongside the Atherton oven circa 1920. Photo: collection of Gordon Grimwade.

Figure 6.5 Croydon pig oven adjacent to temple site. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2001.

Bjornskov (2001, 121) discussed 10 oven sites in the Pine Creek, NT, area including several recorded previously by Bell and McCarthy, also claiming, incorrectly as further research has shown, that ovens are “only found in association with sites where Chinese undertook mining.” Other ovens, particularly in south-east Australia, extending from a relatively small structure at Mitta Mitta in north-east Victoria to Cape York have been noted in ensuing years, to the point where there are now over 80 known nationwide, although information on several remains limited.

The late Professor R. Ian Jack (1935–2019) photographed a collapsed oven at Mookerawa, NSW, in the late twentieth century (possibly the Stuart Town oven recorded in Bell 1995, 227). Juanita Kwok and the late Barry McGowan (1945–2018) reported an oven on a former market garden in nearby Wellington (Juanita Kwok, email, 15 June 2017). A photograph of Chinese gardeners in Bathurst (n.d.), supplied to Kwok by Tony Bouffler, shows a rectangular brick oven in the background. These, along with two ovens at Windeyer (RNE Place No 468 and Bell 1995, 227), form a distinct geographical cluster.

Early in 2021, a large oven near Mt Misery, Victoria, was reported by Richard McNeil (Richard McNeil, email, 19 March 2021). In 2023, four more ovens were noted by the author near Uhrstown and two at Doughboy Creek on the Palmer Goldfield in north-east Queensland. Michael Williams noted references to another at Nerrigundah, NSW (Michael Williams, email, 18 Dec 2023), and Kwok (2023, 107) has noted 12 locations in New South Wales including Bell’s original three. At Timbarra, Kwok notes that three ovens possibly existed (Kwok 2023, 104). It is clearly premature to state that all Australian ovens have now been identified.

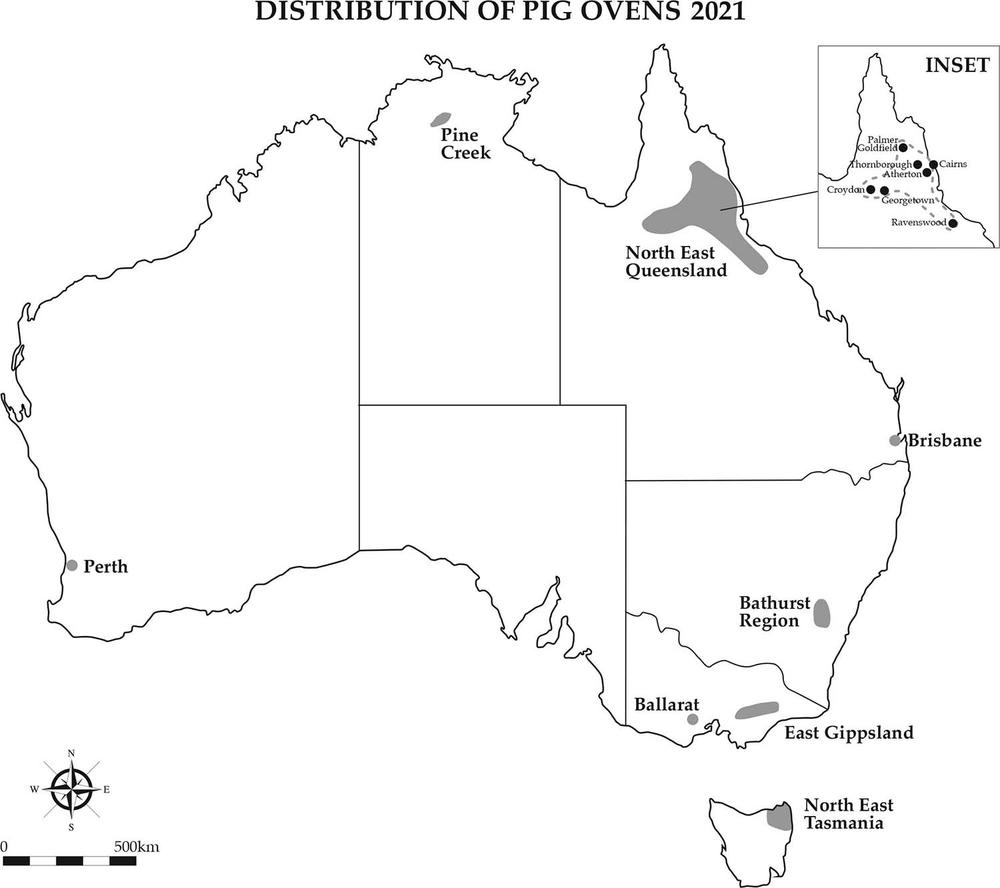

Historical records, particularly early newspapers, provide invaluable evidence of pig ovens, again helping us to understand the scale of their spread and density. Looking across sources and evidence, the distribution remains skewed in favour of Queensland and the Northern Territory, with Tasmania having the third greatest number of ovens (Table 6.1 and Figure 6.6). These results are biased to some extent as they reflect the intensity of research rather than any cultural factors.

| STATE / TERRITORY | Bell 1995 | Current | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 3 | 12–14 | Predominantly in Bathurst/Wellington area |

| Northern Territory | 19 | 19 | Pine Creek area |

| Queensland | 16 | 31 | Predominantly in North Queensland (Palmer, Atherton, Ravenswood and Gulf) |

| South Australia | 0 | 0 | |

| Tasmania | 7 | 10 | North-east Tasmania. Two known destroyed |

| Victoria | 1 | 8 | Widespread. Limited data on several |

| Western Australia | 0 | 1 | Perth |

| Total | 46 | 81–83 |

Table 6.1 Number of pig ovens identified by state and territory.

Figure 6.6 Map showing main areas of pig oven sites in Australia. Map: Gordon Grimwade.

Global context

In any discussion of the Australian experience of pig oven sites, it is also appropriate to consider the use of pig ovens overseas. In New Zealand, three oven sites are known in the South Island: Lawrence (Ng, personal communication, 2007), Ashburton (Grimwade, personal observation, 2007) (Figure 6.7) and Alma (2 ovens) (Bauchop, 2019). In the North Island, Bell noted the presence of ovens in Lower Hutt and Whangarei (Bell 1995, 225), although the latter appears to have been destroyed sometime before 2007 (Grimwade, personal observation, 2007). There is one operational oven at Riverhead, north of Auckland, and at least 12 in the Pukekohe area south of Auckland, some of which are still used infrequently (Ginny Sue, personal communication, 2019). The original Lawrence oven (post-1867) is believed to be the oldest but was destroyed during the twentieth century and since rebuilt. No clear construction dates are available for the other South Island ovens, but most appear to date from a resurgence in pig roasting in New Zealand during the 1950s–1970s (Bernie Lim, Ted Young and Ginny Sue personal communication, 2019). Notably, Neville Ritchie reported no ovens during his extensive study of the Clutha Valley, Otago (Ritchie 1986). With the possible exception of the original Lawrence oven, the known New Zealand ovens, therefore, postdate the gold rushes of the 1870s.

Figure 6.7 Pig oven with gantry and side steps, Ashburton, New Zealand. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2007.

Examples of ovens have also been identified in North America. Wegars (1991, 55) concluded that many so-called “Chinese ovens” on the United States railway network were actually erected by Italians and Greeks for baking bread. Maniery (2001) and others have since, however, identified oven sites, particularly in California, that do have clearly identifiable Chinese origins.

It is critical of course to look beyond diaspora sites and consider pig ovens in countries of origin. In many historical archaeological research projects opportunities may also exist to examine contemporary practices and even to undertake experimental projects not only to validate assumptions but to also test feasibility – together these elements strengthen the validity of excavations, informant interviews and documentary research. During a research visit by the author to Guangdong, China, in 2006, enquiries were made about the use of pig ovens among several archaeologists, none of whom were aware of their use. Social media, however, has since indicated anecdotal and factual evidence about contemporary practice does, in fact, confirm historic and contemporary uses of pig ovens in China and Southeast Asia. For example, YouTube has intermittently, provided video examples of operational ovens in Vietnam, Hong Kong and in an unspecified Central Asian city. Similarly, in Islamic Central Asia, tandir style clay ovens are used to bake bread, cook plov and roast joints (other than pork) in a manner reminiscent of the larger Chinese pig ovens.

The possibility of technological adaptation and transfer is beyond the scope of this chapter, but worthy of further research.

Oven construction and typologies

Ovens were the product of communal activity for community benefit. Not only was there the need for skilled stonemasons to ensure physical integrity, but the acquisition of raw material would have required significant labour over several days.

Physically, five oven variants have been defined in Australasia:

- ramped access to the oven top (Atherton, Croydon, Qld)

- a free-standing oven accessed by a gantry sometimes with steps up for access (Ashburton, NZ and possibly the Palmer Goldfield, Qld and Pine Creek, NT)

- an oven built into a steep bank with ground level top opening (Thornborough and Uhrstown, Qld and Riverhead, NZ)

- “mini-ovens”, possibly used for roasting smaller joints of meat (Mitta Mitta, Vic)

- rectangular ovens (Lone Star Creek, Palmer Goldfield, Qld, and Bathurst, NSW).

Structurally, pig ovens must meet the following key criteria:

- built of stone capable of retaining heat for several hours

- built of stone that will not crack or explode when heated

- large enough to hold a substantial fire capable of heating the walls for the entire cooking time

- fitted with a bottom vent to generate draft and from which ashes could be raked easily with minimal heat loss and which could be plugged during cooking

- provided with a top access wide enough to feed in firewood and to lower in at least one pig

- fitted with a heat-retaining lid for the top access vent.

Topography and geology played significant roles in determining the style of oven and its structure. For example, it would be a foolhardy group that would risk using stone that might explode and embed fragments in the roasting pig. Carefully selected local stone sources were thus important considerations. Sloping terrain, such as creek banks, was an obvious prerequisite for the ground level access ovens. Although early examples of ovens were built using available unworked rock, many later structures used kiln fired clay bricks. In some cases, like Thornborough, Queensland, brick was used in the lower internal courses and stone near the top (Figure 6.8). Access to refractory (fire) bricks was relatively difficult in nineteenth-century Australia. Their superior ability to retain heat made them favoured for later structures as is evident in the numerous mid-twentieth-century North Island New Zealand ovens (personal observation, 2019). This tendency was also favoured in California (Maniery 2001, 3).

Figure 6.8 Pig oven constructed on sloping terrain, Thornborough, far north Queensland. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2013.

The archaeological evidence of most Australian ovens indicates they were usually circular, built of unmodified locally sourced rock and, in northern regions at least, mortared with ant bed: pulverised termite mounds mixed with water. Elsewhere, clay soils were preferred which, when mixed as slurry and allowed to dry, formed a hard, almost impervious, bond – particularly after being subjected to intense heat. It is generally considered that the oven “cores” – the (almost) cylindrical stone structures that are all that now remain at many early oven sites – were probably covered with a generous outer coating of clay or concrete plaster to assist with heat retention. Over the years, this has eroded, leaving only the core (Wegars 1991, 37). This is consistent with the concrete mortar rendered Ashburton oven and the Vietnamese example noted previously.

The larger and most common Australasian ovens comprise a core burning chamber approximately 1.8 to 2.5 metres high (many are now significantly shorter due to deterioration). This is sufficient to enable a prepared carcass to be suspended from the top vent so that the snout is about 300 mm above the oven floor. In Perth, it was reported that “pigs are roasted, but in an oven ten feet [three metres] deep, and by way of variety, mutton occasionally meets with a similar fate”

(Sunday Times 1922, 17). Internally, the chambers are tubular, barrel-shaped or cone-shaped. A vent at the base – opposite the ramp or at right angles to the gantry steps depending on the construction style – enhances the draught and generates rapid combustion of the timber with which it is fuelled. Although there is currently no archaeological evidence to indicate the preferable species of fuel timber, personal experience suggests that small logs of eucalyptus species provide optimal heat in a relatively short period. Large logs burn too slowly to provide the desired rapid heat increase needed to achieve optimal cooking temperatures.

There is little evidence of metal grates being built into the ovens. Most are simple chambers into which fuel is dropped, ignited and burnt quickly to then retain the heat for as long as possible. Rules have their exceptions of course. The oven at Wellington, NSW, is the only known extant Australian oven where it has been established:

12 –15 inches (300–375 mm) up a round steel mesh laid between brick wall for holding fire logs up, sometimes unwanted steel pieces would also be (br)ought in, charcoal and ash from burnt log fall through (the) mesh, a camp oven would be put on the steel mesh after fire wood burnt down to catch the fat drippings (Sing Lee 2017).

The top vent opening is generally around 650 to 700 mm wide, which is sufficient to lower a pig carcass into the cooking chamber. Some have larger openings to accommodate two or more pigs at a time. As recently as 2019, the Red Season Aroma Restaurant, Hong Kong, could fit up to five pigs in one oven, with the cookhouse utilising several ovens at once. The ovens at both Lit Sung Goong, Cairns, and Holy Triad, Breakfast Creek, Brisbane, may also have been capable of cooking multiple pigs at once. The top vent, as noted earlier, remains fully open during the firing/heating period to maximise draft and to allow additional fuel to be added quickly. After the pig is lowered into position the top is covered to provide a rudimentary seal.

So-called “mini-ovens” have been recorded in several Australian locations; for example, at Mitta Mitta, Victoria, which, in 2004, was 550 mm high and 900 mm wide at the top vent and had a base diameter of 1200 mm (Kaufman and Swift 2004, 37). Bell (1995, 219) also notes the existence of several Queensland ovens around 800 mm high. Their function is less certain as they would only be capable of roasting joints of meat or small animals (rabbits, bandicoots or chickens) or to heat a large wok positioned over the top vent.

Figure 6.9 Spiked baton used to perforate skin before roasting as an aid in development of crackling. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2019.

Ancillary tools

Beyond the ovens themselves, it is important to recognise that a suite of artefacts was used, and continues to be used, in pig roasting. Tools associated with the cooking process include sharp knives to “butterfly” the carcass and a preparation table. The practice of forcefully striking the carcass with a baton, through which nails have been driven, is common in New Zealand and effectively pierces the skin to maximise fat discharge during cooking and develop the much sought after crackling. Various YouTube video clips indicate this is also considered important by present day Hong Kong chefs. Ray Chong (New Zealand) strikes the carcass with the baton before lowering the pig into the oven while chefs at the Red Seasons Aroma Restaurant cook the pig for a quarter hour, remove it, pierce the carcass and then return it to the oven (Grimwade 2008).

Present day operators, like their forebears, use long handled ash rakes that can be pushed into the bottom vent to scoop out the wood ash and charcoal once the oven has reached the required temperature. These rakes comprise a rectangle of steel plate, slightly smaller than the bottom vent, secured to a long rod about two metres long, to allow the operator to reach ash on the far side of the oven floor. Ash dispersal patterns observed at Atherton Chinatown’s original oven site suggest the practice has historical origins. Darwin resident Lily Ah Choy recounted in the early 1990s to historian Peter Bell, that “when the oven was very hot the coals were cleaned out” (Bell 1995, 220).

Before lowering the pig into the oven, a wok or camp oven, full of water, is lowered to the oven floor as a means to prevent dripping fat from catching fire and to generate moisture during cooking (Ray Chong, personal communication, 2007). Bell (1995, 22), however, notes in the historical context, “a tray was put in the bottom to catch the fat”, clearly demonstrating that there were wide ranging personal preferences at work within broad societal norms. Again, personal preferences are evident and there is no reason to suspect variations of this kind were uncommon.

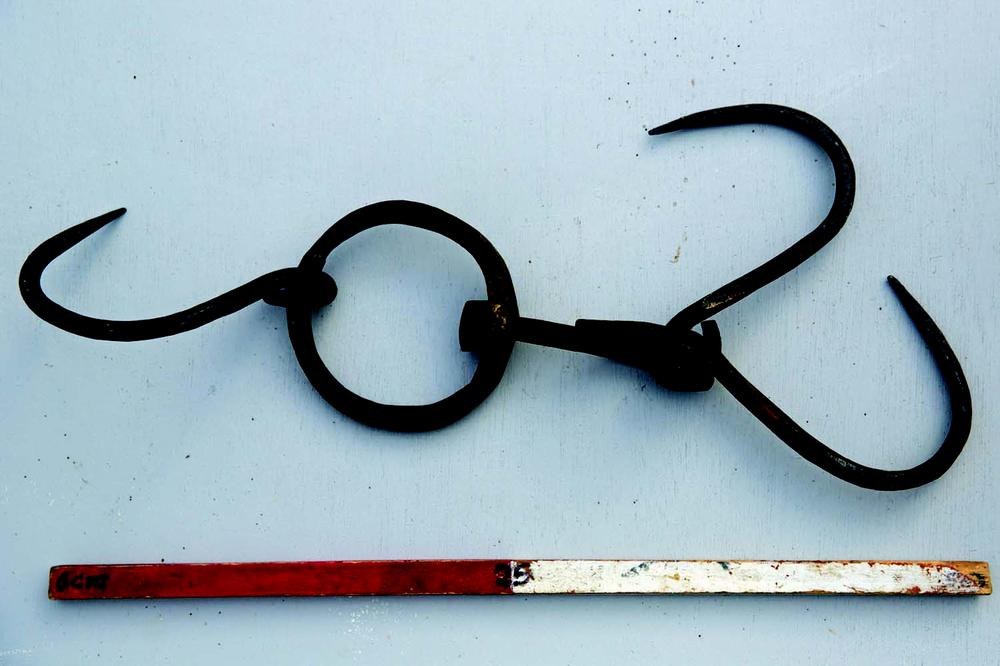

Elaborate multi-ring hooks have long been used to secure the hindquarters of the pig during cooking. Nineteenth-century examples are held in the collections of the former Lit Sung Goong (Cairns), the Cooktown Museum and at Wellington, NSW. They show some similarities to the stainless-steel hooks used by Red Seasons Aroma Restaurant, Hong Kong around 2023.

In an experiment using scale drawings and photographs, three blacksmiths produced a wrought iron replica of the Cairns example in approximately six hours (Figure 6.10). No doubt the production rate would have been faster in the past. The single top hook is hung over the metal pole, supporting the carcass during cooking, while the other two hooks secure the hindquarters.

Figure 6.10 Hooks used to suspend the pig from its hindquarters during roasting process. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2007.

A plug inserted in the bottom vent helped control the draft and minimised heat loss during cooking. Present day plugs range from metal plates with welded handles to thick blocks of hardwood around 200 mm thick, suggesting, historically, such fittings were created opportunistically depending on locally available resources and skills. The top vent was, at least in more recent examples, covered with a variety of fireproof material with corrugated iron or steel caps and “sealed” with wet hessian sacks. There are inferences that large rocks may have been used opportunistically in lieu of metal caps, although firm evidence of this has yet to be found.

Cooking process

Early Australian investigators have suggested a cooking process similar to those used in ground ovens:

A fire would be lit in the base of the oven and fed from the opening at the base, then large stones would be lowered and allowed to become red hot. A whole pig would be lowered onto the stones and a brass or metal cover placed over the opening until the meat was thoroughly cooked (Victorian Heritage Database, n.d.).

Such a process would, in practice, have been unworkable. First, the bottom vents were intended to provide draft and were too small to insert fuel. Secondly, there would have been insufficient space for both the pig carcass and enough stones to provide adequate heat.

Contemporary practices of pig cookery using ovens of this nature, however, provide a more probable indication of past practices. Current methods involve the dressed pig being “butterflied”, to expose the fleshiest parts more evenly to the heat. Care is needed to avoid cutting too deeply and thus increase the risk of the pig disintegrating during cooking. The hooks are then secured into the hindquarters and, if it considered necessary, fencing wire added as extra security (Ray Chong, personal communication, 2007) (Figure 6.11). The widespread existence of the hooks, described above, suggest that they have been used for many years and are clearly designed to accommodate a butterflied carcass.

Figure 6.11 Butterflied pig carcass ready for oven. Note hooks in hindquarters, Riverhead, New Zealand. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2007.

The pig is then marinated, with many cooks having their own closely guarded recipe. Tim Sing Lee’s father used “a mix of five spice and soy sauce with a small amount of saltpetre to help colour the meat” (Tim Sing Lee, personal communication, 2017). It is worth noting that saltpetre also reduces the risk of botulism and has a long history of use as a meat preservative (Berk 2013, 591–606). Sing Lee further notes, “a trough would be cleaned and filled with a mixture of salt, water, spice of something, homemade sprite spirit] to marinate the pig for overnight, in the morning the pig would be hang up [sic] to dry before being lowered down to the oven”. Bell writes, “Frank Chin from Tasmania and Lily Ah Toy from Darwin both describe how the pig carcass was dressed and marinaded in sauces (soy sauce with garlic and ginger)” (Bell 1995, 220). In New Zealand, Ray Chong (personal communication, 2007) uses a “mix of Chinese ‘five spice’, soy sauce and Chinese whisky”. Chong states that some cooks added cochineal to get a red (lucky) colour to the meat, unlike Sing Lee who was adamant that cochineal was not used to develop a red colour to the pork (Grimwade 2008, 26; Sing Lee, personal communication, 2017). Other accounts are silent on the marinating process but there is good reason to believe it was, and is in its various incarnations, an essential part of the cooking process; although, in some instances, it was secondary to the delights of the final product. In pre-war Atherton, John Fong On (1915–2001) noted that for the Qing Ming festival, Hung Mun, a Chinese cook working at the nearby Lake Eacham Hotel, “would get a day off and barbecue a large pig at the barbecue pit [sic] at the rear of the Hou Wang temple. He was an expert at barbecuing and the pork would come out crackling. It was delicious, but we kids preferred the pork fillets” (Lee Long 1996, 30). Fong On’s reference to the “barbecue pit” is the original oven, indicating it was still operational during the late 1920s.

Several hours before the feast, a large fire would be started in the oven with the vent plug completely removed to maximise the draught. The fire was kept burning strongly until it was considered the oven chamber was hot enough. As soon as practical, the hot ash was raked out and the vent plug fully inserted. In line with present day practices, the water-filled wok and the pig were lowered into the oven so that the snout was just clear of the wok. The top vent was then covered and the contained heat left to do its all-important work.

Cooking takes from two and a half to four hours, depending on the size of the pig, the oven temperature and heat loss (Grimwade 2008, 26) (Figure 6.12). If poultry was also to be cooked it was lowered in later on in the cooking period and usually hung near the top to maximise use of available heat (Grimwade 2008, 26). Historical accounts infer a similar process was followed.

Figure 6.12 Ray Chong and assistant haul roast pig from oven, Riverhead, New

Zealand. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2007.

Several oral sources suggest that if the pig was not fully cooked it was removed, the fire rekindled and the pig returned to the oven once the bricks were reheated. Once cooked, the roast was carefully removed and carried on a rudimentary bier – a discarded door is ideal – to the feast, for carving and distribution.

The absence of pork bones in the vicinity of the original Atherton oven tends to confirm that the carving was not conducted near the oven and possibly had ceremonial relevance. In the past, a strict code of conduct ensured distribution of the meat was carefully controlled. This protocol has been modified through evolving cultural traditions. Mrs Sing Lee noted that the family, originally from the Loong Dhu region of Guangdong, would select portions by weight based on pre-sold tickets. She further noted, “Money raised went to the butcher for the slaughter and dress the pig. All work were [sic] done by men, women were not permitted to handle all those sacred things. The cost and size of portion differ each year” (Mrs Sing Lee, personal communication, 2017). Cairns resident, Bishop George Tung Yep (born 1927) recounts being punished when, as a lad, he “stole the tail of the roast pig before it could be offered in the temple and was punished severely for this misdemeanour” (Grimwade in press). Those practices and repercussions have mellowed over time. At a family reunion in Atherton in 2018, the meat was simply carved and portions handed out on a “first come, first served” basis (Grimwade, personal observation, 2018).

Oven reconstruction

In 2015, the opportunity was afforded to undertake both an excavation and a reconstruction of the Atherton oven, with funding provided by the National Trust and the Queensland Government’s Everyone’s Environment Grant scheme. The original oven had been bulldozed in the mid-twentieth century (John Fong On, personal communication, 1987). Its location was identifiable from a single photograph and ground truthed to where a patch of charcoal-stained soil and some rocks were identified, south-west of the temple.

While the original site was previously bulldozed, relict evidence indicated that the oven was about two metres wide at the base and had faced north. An extensive ash deposit covering about 15 metres square from near the lower vent confirmed that the ash had been raked out and spread, which was consistent with reported cooking practices (Grimwade 2016). Among the diverse and largely unrelated artefacts recorded there was only one piece of pig bone recovered. Machinery and other ferrous metal artefacts were concentrated adjacent to the ramp indicating that, as use of the oven waned, it became a convenient storage facility.

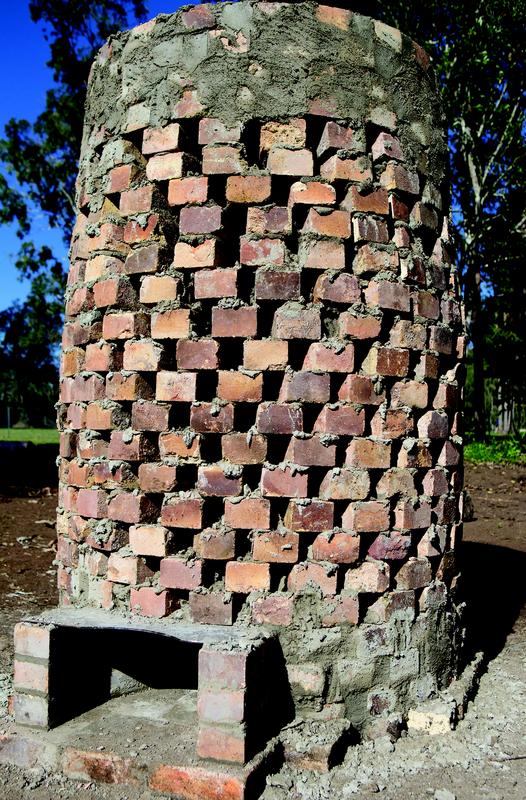

An archaeologically sterile area was identified nearby and a new, north facing, ramped oven was constructed. Given the minimal evidence of the original oven, the project team decided that the experimental oven would be ramped (consistent with the photographic evidence) and of similar proportions scaled from the original photograph. The ultimate design was based on field research of other ovens and the need to provide a more durable resource that the owners, the National Trust, could use for educational and entertainment purposes.

Given the annual rainfall of the region is around 1,200 mm, the ramp sides were protected with basalt rock walls to minimise erosion and improve longevity, instead of simply being left as a compacted soil ramp. A plywood template guided the stonemasons in the construction of the tapered cylinder for the actual cooking chamber.

The two-metre-high oven, with a 700 mm top opening, was constructed using second-hand firebricks to provide optimal heat retention and longevity (Figures 6.13–6.15). Initially, it had been intended to use local rock and to mortar the joints with crushed termite nests similar to that which had been used in ovens like Croydon, however this did not prove to be practical. The oven was subsequently cured by lighting a small fire in the base to reduce the risk of cracking and then fully heated. Volunteers were provided with meat from a “test fired” leg of pork.

Figure 6.13 Oven core of replica oven, Atherton, Queensland. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2016.

Figure 6.14 Oven completed with partially constructed ramp later filled with rock and

soil, Atherton, Queensland. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2016.

Figure 6.15 Completed replicated oven, Atherton, Queensland. Photo: Gordon Grimwade 2021.

Conclusions

Archaeological research is an ongoing process. Definitive outcomes are as dynamic as the environment in which archaeological sites exist. The ongoing research into the large stone ovens that started over 40 years ago has, fortuitously, enabled much to be learnt about the structures, their use and how they fitted into the cultural landscape. In the process, it has become clear they were often associated with temples and part of long-standing culinary cultural practices, and were not simply associated with large-scale mining settlements.

The technique of roasting whole pigs in a socio-religious setting is demonstrably a dying art. This historically important element of Chinese migrant life in Australia and elsewhere in Pacific Rim countries has, however, been progressively documented to show that the distribution of ovens and, by extension their significance, is far more widespread than was initially thought. In 1995, Bell (1995, 6) had hypothesised “the oddest aspect of the oven’s geographical distribution in Australia is not where they are, but where they are not”. Decades later, we have been able to demonstrate not only a wider spatial distribution – though still absent from South Australia – than initially envisaged but have also acquired a greater appreciation of how much work was involved in constructing ovens as well as the links to ceremony and celebration that they helped forge. Archaeological fieldwork combined with historical research, interviews and experimental archaeology have made it possible to correlate contemporary and past practices to produce a more definitive record reinforcing the value of multi-faceted research.

Chinese pig ovens have played important roles around the Pacific Rim as a component of both religious and secular activities. Current research suggests that, while the focus has moved from cooking at the rear of a temple to specialist kitchens supplying restaurants and private dwellings, this food still plays a significant role in modern Chinese culinary art. In the process, the move from religious ceremony to commercial exploitation demonstrates the dynamic forces that affect cultural change and development.

Acknowledgements

Inevitably when dealing with research that spans around four decades countless people have assisted in providing assistance. To list everyone is “mission impossible” and I apologise to those I have omitted; your contribution was no less important. My thanks to: my reviewers, Dr Peter Bell, Prof Heather Burke, Ray Chong, Melissa Dunk, Denise Gaughwin, Prof Martin Gibbs, Rev Christine Grimwade, Prof Manying Ip, Dr Juanita Kwok, Vicky and Max Lake, Prof Susan Lawrence, Paul Macgregor, Justin McCarthy, Dr Kevin Rains, Dr Sandi Robb, Dr Neville Ritchie, Martin Rowney, Dr Madeline Shanahan, Kym Stotter, Sherri du Toit, Dr Priscilla Wegars, Dr Michael Williams, Rhonda Micola and Friends of Atherton Chinese Temple Inc., Hans Pehl (blacksmith), John and Nola O’Boyle (stonemasons),Ginny Sue, Ted Young, Tim Sing Lee, Bernie Lim and Federation of NZ Chinese Commercial Growers Inc. and the late Mary Low and Henry Chan, John Fong On, Prof Ian Jack, Dr Barry McGowan and Dr James Ng.

References

Adamson, J. and H-D. Bader (2013). Gardening to prosperity: The history and archaeology of Chan Dah Chee and the Chinese market garden at Carlaw Park, Auckland. Finding our recent past: historical archaeology in New Zealand, 143–65. Auckland: NZ Archaeology Association.

Alfredson, G. (1988). Draft Report on the Initial Archaeological Survey of the Doughboy Creek Gold Project for Australian Groundwater Consultants. Chapel Hill: Alfredson Consulting Pty Ltd.

Associated Press (2019). Last remaining pig roaster busy ahead of Year of the Pig (2019) [video], YouTube, accessed 5 December 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKzZaU9pVy4.

Baldwin, J.A. (1986). Pre-Cookian Pigs in Australia? Journal of Cultural Geography 4(1): 17–27.

Bauchop, H. (2019). Heritage item summary report: Chinese pig roasting oven and gantry. 513 and 579 Fortification Road, Alma. Unpublished typescript, Oamaru, NZ.

Bell, P. (1996). Archaeology of the Chinese in Australia. Australasian Historical Archaeology 14: 13–18.

Bell, P. (1995). Chinese ovens on mining settlement sites in Australia. In P. McGregor, ed. Histories of the Chinese in Australasia and the South Pacific, 213–29. Melbourne: Museum of Chinese Australian History.

Bell, P. (1983). Pine Creek: report to the National Trust of Australia (Northern Territory) on an archaeological assessment of sites of historic significance in the Pine Creek district. Report to National Trust of Australia, Northern Territory.

Bengsen, A., P. West and C. Krull (2017). Feral pigs in Australia and New Zealand: range, trend, management, and impacts of an invasive species. In M. Melletti and E.R. Meijaard, eds. Ecology, conservation and management of wild pigs and peccaries, 325–38. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berk, Z. (2013). Food process engineering and technology. London: Academic Press.

Bjornskov, M. (2001). Rock, mortar and traditions: an archaeological study of Chinese “ovens” in the Northern Territory. In C. Fredericksen and I. Walters, eds. Altered states: material culture transformations in the Arafura region, 121–47. Darwin: Northern Territory University.

Brown, A. (2017). Stoked: cooking with fire. Auckland: Random House.

Burke, H. and G. Grimwade (2013). The historical archaeology of the Chinese in Far North Queensland. Queensland Archaeological Research 16: 121–40.

Clarke, C.M.H. and R.M. Dzieciolowski (1991). Feral pigs in the northern South Island, New Zealand: origin, distribution, and density. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 21(3): 237–47.

Comber, J. (1991). Palmer Goldfield Heritage Sites Study (Stage 2). Report to Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage, Brisbane.

Cuff, T. (1992). A weighty issue revisited: new evidence on commercial swine weights and pork production in mid-nineteenth century America. Agricultural History, 66(4): 55–74.

Darwin, C. (1868). The variation of animals and plants under domestication. London: John Murray.

Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2011). The Feral Pig. Canberra: Australian Government.

Gaughwin, D. (1995). Chinese settlement sites in north east Tasmania: an archaeological view. In P. McGregor, ed. Histories of the Chinese in Australasia and the South Pacific, 230–48. Melbourne: Museum of Chinese Australian History.

Giuffra E., J.M.H. Kijas, V. Amarger, O. Carlborg, J.T. Jeon and L. Andersson (2000). The origin of the domestic pig: independent domestication and subsequent introgression. Genetics 154: 1785–91.

Grimwade, C. (in prep). Barrow boy to bishop.

Grimwade, G. (2024). Worshipping the North: early Chinese temples in mainland tropical Australia. International Journal of Historical Archaeology. DOI: 10.1007/s10761-024-00762-6.

Grimwade, G. (2016). Pig oven excavation and reconstruction, Atherton Chinatown. Report to Friends of the Atherton Chinese Temple Inc., Atherton.

Grimwade, G. (2008). Crispy roast pork: using Chinese Australian pig ovens. Australasian Historical Archaeology 26: 21–8.

Grimwade, G. (2003). Gold, gardens, temples and feasts: Chinese temple, Croydon, Queensland. Australasian Historical Archaeology 21: 1–8.

Grimwade, G. (1990). Palmer River Goldfields cultural resources [3 vols]. Report to Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage, Brisbane.

Grimwade, G. (1988). Historical site survey: Fortuna Pty Ltd, Palmer River, Qld. Report to Fortuna Pty Ltd, Cultural Resource Services Pty Ltd, Cairns.

Hollis, G. (2002). Swine [video], Livestock Trail by University of Illinois website, accessed 27 July 2021. http://livestocktrail.illinois.edu/porknet/questionDisplay.cfm?ContentID=4696.

Hum Lee, R. (1960). The Chinese in the United States of America. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Jack, R.I., K. Holmes and R. Kerr (1984). Ah Toy’s garden: A Chinese market garden on the Palmer River goldfield. Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology 2: 51–8.

Kaufman R. and Swift A. (2004). Historic mining sites survey: Mt Wills and Mitta Mitta area goldfields, unpublished report, LRGM Services.

Kirkman, N. (1984). The Palmer Goldfield 1873–1883. Honour’s thesis, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld.

Kim, S-O, C.M. Antonaccio, Y.K. Lee, S.M. Nelson, C. Pardoe, J. Quilter and A. Rosman (1994). Burials, pigs, and political prestige in Neolithic China [and comments and reply]. Current Anthropology 35(2): 119–41.

Kwok, J. (2023). A reassessment of Chinese pig ovens in Australia. Journal of Australasian Mining History 21: 95–113.

Lamb, C. (2013). A Dissertation upon Roast Pig, Project Gutenberg, accessed 7 May 2025. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43566/43566-h/43566-h.htm.

Lee Long, W. (1996). Recorded interview with John Fong On. Post-war Chinese Australians Oral History Project TRC 3447 [audio file], Oral History Section, National Library of Australia, accessed 24 May 2023.

Maniery, M.L. (2001). Fuel for the fire: Chinese cooking features in California. Paper presented to Society for Historical Archaeology, annual meeting, Long Beach.

McCarthy, J. (1995). Tales from the Empire City: Chinese miners in the Pine Creek region, Northern Territory, 1872–1915. In P. McGregor, ed. Histories of the Chinese in Australasia and the South Pacific, 191–202. Melbourne: Museum of Chinese Australian History.

McCarthy, J. (1989). Would be diggers and old travellers: the Chinese of Union Reefs and the Twelve Mile in the Northern Territory 1876–1910. Report to National Trust of Australia, Northern Territory.

McCarthy, J. and P. Kostoglou (1986). Pine Creek Heritage Zone Archaeological Survey. Report to National Trust of Australia, Northern Territory.

Morris, S. (1984). Oriental cooking. Sydney: Doubleday.

Raw Street Capture (2016). Vietnam street food – Crispy Roast BBQ Whole Pig Pork in Charcoal Oven – Street food in Vietnam 2016 [video], YouTube, accessed 5 December 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E0v8RGVD68Y.

Register of the National Estate (archived material), accessed December 2021. https://www.awe.gov.au/parks-heritage/heritage/places/register-national-estate.

Ritchie, N. (1986). Archaeology and History of the Chinese in Southern New Zealand during the Nineteenth Century, PhD thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin.

Ruvinsky, A. and M.F. Rothschild (1998). Systematics and evolution of the pig. In A. Ruvinsky and M.F. Rothschild, eds. The genetics of the pig, 1–16. Oxford: CAB International.

Tomlin, O. (1979). Gold for the finding: a pictorial history of Gippsland’s Jordan Goldfield. Melbourne: Hill of Content.

Tsang, K.B. (1996). Chinese pig tales. Archaeology 49(2): 52–7.

Van Kempen, E. (1985). Survey of historic Chinese sites in Queensland and the Northern Territory. Report to the Australian Heritage Commission, Canberra.

Victorian Heritage Database (n.d.) Chinese pig oven. Victorian Heritage Database Report. https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/10792/download-report.

Visit Beijing (2017). Cured meats are the preserve of Spring Festival. Visit Beijing website, accessed November 2023. https://english.visitbeijing.com.cn/article/47ONkGcUhWV.

Wang, S. (2004). Chinese Gods of Old Trades. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

Wegars, P. (1991). Who’s been working on the railroad? an examination of the construction, distribution, and ethnic origins of domed rock ovens on railroad related sites. Historical Archaeology 25(1): 37–65.

Newspapers

Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 5 December 1872.

Portland Guardian and Normanby General Advertiser, 14 April 1873.

Queenslander (Brisbane, Queensland), 30 January 1886.

Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 7 May 1887.

Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW), 5 March 1922.

Weekly Examiner (Launceston, Tasmania), 17 August 1872.