18

EMANCIPATION OF THE SURFACE

ARCHITECTURE OF SPATIAL DISLOCATION

The modern fear of the dark emaciated the architectural surface to a veil of transparency in the name of absolute visibility and reality. It was an architectural principle that enjoyed Vitruvian origins, whereby architecture was the product of a triple essence, utilitas, firmitas, venustas,1 its public edifice imbued with the symbolic manifestation of order and truth. Sharing the visionary attitudes of Taut towards glass as the ultimate destination for an apolitical architecture, Modernists regarded “… construction itself as the primitive cell of architecture.”2 Form could thus be idealised the moment it shed its extraneous and artificial mask, the moment it undressed, or exposed itself to the public eye. For Mies Van der Rohe, the idea of stripping architecture to its essence culminated in his glass skyscraper entry to the Friedrichstrasse Competition of 1921,3 where the office tower became a monument of transparency. The transparency of glass freed the structure from the exclusivity of its optical barriers, privileging neither the interior nor exterior in the revelation of its inner material truth. Contemporary architecture, while exploiting technical innovation and experimental digital techniques often buttresses the neo-classical stronghold that has both navigated and steadied architectural truths since the architecture of the ancient Greeks. Many intelligent facades and invisible sheaths still operate to filter, reveal or conceal their tectonic basis, forming a polarised relationship on a symbolic level between surface and substrate. The result? We find structures in costume dress. Gottfried Semper, a nineteenth century Viennese born architect and theorist, overturned 197the architectural surface’s representational function by rejecting the historically accepted belief that truth was located in the substratum. He offered instead the decorative woven essence of the architectural surface. Semper asserted that the ritual of primitive space production was that of dressing rather than undressing. He developed this theory following the discovery of traces of paint on the facades of ancient Greek monumental architecture. Theorists had interpreted the naked marble forms of antiquity as architectural paradigms, alluding specifically to their tectonic revelation. Semper insisted that the marble’s power lay in its potential to conceal, not reveal. The material’s smooth and dense qualities realised its potential as antique stucco.4 The surface, until then understood as an extraneous outer layer, offered a decorative essence that denied the materiality of its tectonic basis. Semper regarded it as: “…the subtlest, most bodiless coating…the most perfect means to do away with reality, for while it dressed the material it was itself immaterial.”5 Semper’s book The Four Elements of Architecture overturned not only the wall’s tectonic origins, but the location of architecture’s essential truth. Architecture was no longer the act of dressing the naked form. It begins with masking or dressing; load bearing is a secondary function:

Hanging carpets remained the true walls, the visible boundaries of space. The often solid walls behind them were necessary for reasons that had nothing to do with the creation of space; they were needed for security, for supporting a load, for their permanence, and so on. Wherever the need for these secondary functions did not arise, the carpets remained the original means of separating space.6

If architecture begins with the ‘creation of space’ and the textured surface is the ‘true’ and legitimate wall, it follows that spatial delineation has primacy over and precedes the requirements for load bearing. The textiles or enclosures provide space with a visible limit, which operate to define the space of the interior and distinguish it from the exterior. They elucidate a twofold truth: that spatial division, the delineation of “… inner….(and) outer life”7 was an effect or function of the enclosing membrane, and that such spatial demarcation was primordial. Semper’s interpretation of the surface as at once decorative and functional resists all symbolic reading associated with the wall. The Semperian surface is not an extraneous outer layer with inherent symbolic meaning but architecture itself. If 198the mask, or the “… visible boundaries of space”8 fashion the domestic realm, then the masquerade produces the public realm. For Semper, the masquerade is the “… motive of the permanent monument.”9 Social space is an explicit fabrication produced by festival apparatus10 or the stage-set upon which hangs the optical barrier that defines it. Public space begins with the ritual of the theatre, the “… haze of carnival candles,”11 presenting an artifice and denial of reality that is entirely visual. Telluric mass is de-materialised and subordinated behind an optical barrier. Public space operates as a function of the destruction of matter. In his paper Untitled: the Housing of Gender, Mark Wigley distils the emaciation of architecture that has occurred as a product of Semper’s subversion:

Architecture is literally in the layer of paint which sustains the masquerade.12

The RE Studio’s13 Soft Inversions installation in the Turbine Hall emerges as something of a paradigm for Semper’s theory outlining architecture’s essence. For the last ten years the Tokyo based Responsive Environment art group14 have gained renown for their experiments with spatial expression and responsive environments using media, music, digital techniques and light. Adopting the term ‘Soft Architecture/Soft Urbanism’15 they seek to disturb the historic formal ritual of architecture and planning by exploring the potential of software and thereby “… increasing the proportion of (architecture’s) intangible aspects,”16 realising the possibility of dissolving architecture within the urban network. In their studio’s site-specific installation at Cockatoo Island they used these methods to blur the distinction between inside and out, reality and illusion, using the entire expanse of the Turbine Hall. Walking into the site-specific installation at sunset, one finds a scene whose centre of gravity consists of candles lining the ground in the innermost part of the space. The candles cast their dim light no further than the radius of a metre, leaving the perimeter of the Hall in obscurity. The presence of a lean layer of water covering the entire surface of the Hall creates the visual illusion of doubled-space and renders invisible the horizontal ground plane. The walls and roof recede beyond the relief of coloured beams of light projected onto them from a peripheral source of illumination. These interventions into the existing body (of the building) culminate into one identifiable act of architecture that simultaneously unfolds and unifies space.199

FIGURE 1

CANDLES ALIGNED ON A GRID IN THE ‘SOFT INVERSIONS’ INSTALLATION

The installation celebrates the discipline and scale of spiritual observation marked by the visual metaphor of the cathedral. The hundreds of candles lining the ground plane are disciplined into a grid of rows and columns (Figure 1). The light itself is subdued and regulated, and this together with the encroaching darkness focus the eye toward the centre of the space, to the central and rhythmic source of illumination. The abundance of the ordered candles coupled with the magnitude of the Hall conjures a striking image of a religious spectacle. Even at close range other people are seen as dark silhouettes against the warm glow of the candles. The expansive volume and the intermittent darkness and flickering light revoke the static nature of enclosed space and in its place conjure the masterly illusion of a fluid environment. The flooded surface of the entire Hall locates the site of performance at the horizontal ground plane, transforming the cathedral into a carnival. The water conceals the materiality of the concrete slab and the visual illusion of doubled-space causes it to disappear altogether. The sanctified scene is submerged and upturned, as the observer and candlelight float in space. While the viewer is subconsciously aware of the explicit fabrication afforded by the ‘festival apparatus,’17 or structural slab beneath the water, the artistic atmosphere is not spoiled. The surface mechanism creates a view of the entire ritual beyond 200reach and thereby cultivates the act of looking. The casual observer is transformed into a spectator or voyeur watching the performance (Figure 2). The denial of reality constructed by the scene’s ‘carnival haze’18 resonates with Semper’s theory that the public realm is made possible by the fabricated surface, and that social space begins with the theatre.

FIGURE 2

THE MIRRORED SURFACE OF THE FLOODED HALL REFLECTS THE SPACE OF THE TURBINE HALL AND SPECTATORS WITHIN IT

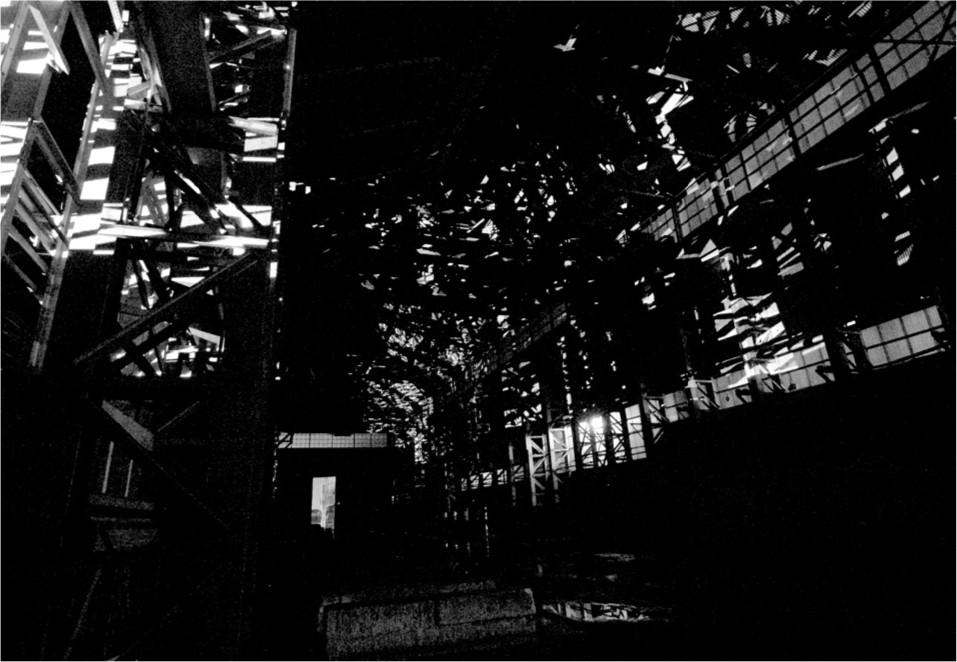

While the theatricality of the scene is a result of the watery mask, the same reflected view locates the spectator or voyeur within the scene (on stage). The mirror frames the delight and surprise of catching one’s reflection in passing, while instantly locating the viewer physically within the performance. The typical theatre dislocates the observer, who sits in a privileged position of obscurity outside the well-lit performance. The RE Studio group casts the observer as both actor and spectator. The spectator is unveiled in the double act of visual and physical intrusion, dissolving the notional proscenium. The act of looking is gently reverberated. The superimposition of the space of looking onto the scene of ritual reflection establishes the ground plane as a permeable and leaky surface. The horizontal surface thereby operates to distribute observation: the delicate 201exposure of the ritual and the seductive echo of observation itself. The installation in fact displaces the Semperian surface by denying the operation of the visible limit. The notional boundary instead creates moments of boundlessness. The performance knits light and space into each other, dematerialising the surface of the Turbine Hall into a support for the spatial illusion. Cool purplish light from a peripheral source is projected onto the roof and wall structures. The steel supports are made visible while the ceiling and walls remain invisible, receding beyond the relief of the truss members. The illumination conjures an animated foil to the tectonic basis of the architectural planes and offers in their place disembodied shafts of light dancing along the beams. Light infiltrates and defines the ceiling and walls, supplanting materiality and creating an atmosphere of surface depth that undermines the gravitas of the walls and roof by dissolving their purposes of shelter and barrier. This conception of light extends the potential of Semper’s ‘colourful paint’ as a limit without substance: the perfect means for enacting the deception of a masquerade (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

PROJECTED LIGHT BEAMS ILLUMINATE THE WALLS AND CEILING OF THE TURBINE HALL

If Semper establishes an architectural essence of boundaries, then the Turbine 202Hall project infuses these with a sense of transience. While Semper’s mask or coat of paint presents a limit that is entirely static, the flashing light transforms the constant planes into momentary sparks of colour. The dancing planes flicker in unrest along the trusses as light appears to unfold, bend and kink, keeping beat with the syncopated sounds of the musical accompaniment. Light exerts a temporal force on the building, which buckles under its weightless strength. Construction is no longer “… the primitive cell of architecture”19 but fleeting and malleable. The power and beauty of the scene comes from the transmutation of a static volume into an elastic shape that deforms in response to forces of light, then instantly recovers its original appearance when the force is removed. The spatial enclosure constantly fractures, as light itself carves into the beams allowing the darkness to erase the visible surface beyond, providing in its place a volatile visible limit. It becomes impossible to determine the demarcation where the hall ends and the sky begins. The effect is of the dramatic transformation of the material into the immaterial, making possible an experience of endlessness. At once dark, moist and disorienting, the ‘responsive environment’ creates architecture that is entirely sensuous and phenomenal - the ultimate expression of Semper’s non-representational surface. Instead of enclosing the space, the installation enhances the void and releases it, allowing light to infiltrate and define the building. In one instant, the viewer gazes down into the sky, at a thousand stars, as space and light are woven into each other in constant flux. Gravity itself feels overcome as one floats in a realm at once deep and shallow and spectacular, the creation of an emancipated suface.

1 Gwilt translates these elements as ‘strength, utility and aesthetic effect’, Vitruvius Pollio, M: 1826, The Architecture of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, Gwilt, J.(transl.), Priestly and Weale, London, Chapter 3, part 2.

2 Wagner, O: 1988, Modern Architecture, (transl.) Mallgrave, HF, Getty Center Publication, Santa Monica, pp.91-93.

3 Schulze, F: 1985, Mies Van Der Rohe, A Critical Biography, The University of Chicago press, Chicago, p.98.

4 Semper, G: 1989, Preliminary Remarks on Polychrome Architecture, in Semper, G: 1989, The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press, New York, p.60.203

5 Op. cit. ‘Der Stijl’, Vol. 1, 445 or Semper, “Introduction,” p. 39.

6 Semper, G: 1989, The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press, New York, p.104.

7 Semper, G: 1989, Style: The Textile Art, in The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press, New York. p.254.

8 Semper, G: 1989, The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press, New York, p.104.

9 Op. cit, p.256

10 Semper, G: 1989, The Four Elements of Architecture, in Semper, G: 1989, The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press, New York, p.255.

11 Op. cit, p.255

12 Wigley, M: 1992, Untitled: The Housing of Gender, in Sexuality and Space, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, p.370.

13 RE Studio participants: Katherine Eustace, Tran Sam, Nguyen Mai, Siddharth Mansukbani, Catherine Downie, Carlo Go and Lois Morgan; Tutors: Jin Hidaka and Satoru Yamashiro with Joanne Jakovich.

14 Responsive Environment art group, http://www.responsiveenvironment.com (accessed 6/11/2006)

15 Hidaka, J: 2004, ‘Soft Architecture/Soft Urbanism’, in J. Hidaka and H. Kamei (eds) Urban Dynamics, pp. 1-4, SlowMedia, Tokyo, p. 1.

16 Isozaki, A, ‘Soft Architecture as Responsive Environment’, cited by Hidaka, J: 2004, ‘Soft Architecture/ Soft Urbanism’, in J. Hidaka and H. Kamei (eds) Urban Dynamics, pp. 1-4, SlowMedia, Tokyo, p. 6.

17 Semper, G: 1989, The Four Elements of Architecture, in Semper, G: 1989, The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press, New York, p.255.

18 ‘Haze of Carnival candles’ Op. cit., p.255.

19 Wagner, O: 1988, Modern Architecture, (transl.) Mallgrave HF, Getty Center Publication, Santa Monica, pp.91-93.