17

RETHINKING PARAMETERS

THE ISLAND

Design Studios are an essential learning experience for architecture students. Their traditions and proceedings are well established. The studio is informed and supplemented by events, the city and the built environment, all of which contribute to participants’ learning. This in turn expands the learning environment and contributes to society in general. Hitherto there has been a gap between skill training and the application of knowledge to the cultural context of society. The Urban Islands Studio1 went beyond simple skill training and required reflection and the creation of knowledge to flow back into the larger society. In other words, the studio was to the discourse of urban design, what Cockatoo Island is to the rest of the city.

The gap between expertise and the application of knowledge often becomes apparent in relation to urban design studios, where on one hand the underlying concepts of architectural design and philosophies of urban development are presented, and on the other hand, students must be taught the technical skills of the field.2 The integration of both within a single design studio often fails because the compound acquisition of skills can prevent a deeper exploration of design and its theoretical aspects. Only long after participants have gained proficiency are they able to tackle design. Yet by then, these skills may no longer be valid because of the complexity of urban design problems. The knowledge and the skills students gain quickly becomes inactive because the learning foci of the urban design problem shift to other aims.186

The Urban Islands Studio addressed these issues by integrating the training and designing modes right from the outset, through a series of compact workshops, seminars and lectures. This allowed the participants to draw from their own experiences and expertise and apply this deep into the project and beyond, as documented in this volume. Participants were inspired by their rich and informative experiences of Cockatoo Island from the first day, and from there expanded the development and communication of their understanding. The idea builds upon design studios held in the past that have allowed participants to explore design beyond its original definition and perceived limits.3 This kind of urban design studio explores and addresses the evolving dimensions of cities, whereas conventional master plans do not reflect the fluid relationship between a city and its inhabitants.

THE TOWER OF BABEL

The exploration of the relationship between human beings and the natural world and the subsequent implications for their interaction has deep roots in the social-cultural understanding of a society. A city is a direct reflection of its inhabitants, whereas design directly influences the living conditions of the people. In recent practice, cities have been designed and described by master plans that depict a picture-perfect, complete city in which change does not appear. A few have tried different approaches.

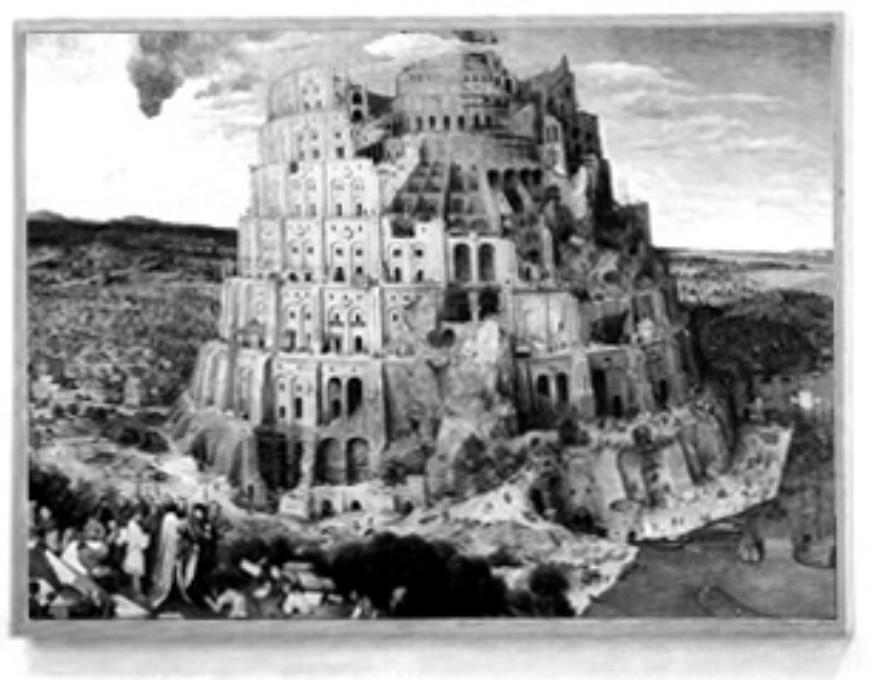

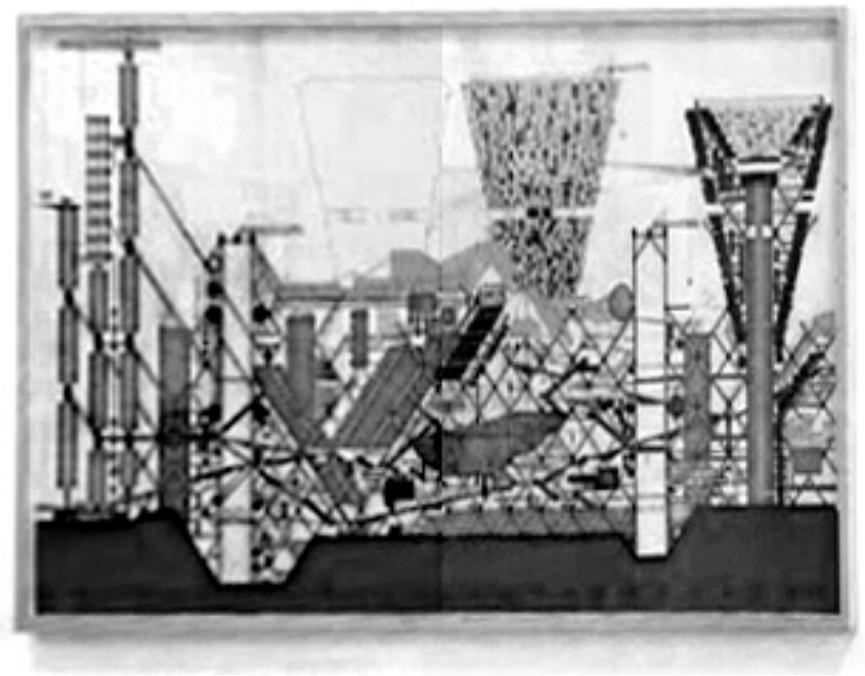

In the sixteenth century, Pieter Bruegel painted the Tower of Babel represented as a miniature city (Figure 1). A tower piercing the clouds represents the entire problem of cities and city life. It is not an ideal depiction, but one of a city crumbling and rebuilding at the same time. This city is constantly changing. In the sixties and early seventies, Archigram Architects proposed a similar idea. Reacting against the permanence of the house in their ‘Plug-in City’ (Figure 2), they proposed ever-changing units adaptable to different social and economic conditions.4 Nevertheless, these examples never became the norm in thinking about the city. Instead, what has been practiced for centuries is much closer to Le Corbusier’s idea of the city as a machine. A description based on an organism or an ever-evolving system for generating desirable outcomes is much closer to reality.187

FIGURE 1

PIETER BRUEGEL (1525/30-1569) TOWER OF BABEL 5

FIGURE 2

ARCHIGRAM’S PLUG-IN CITY 1962-1964

188A building, an urban situation or architecture in general can be expressed and specified in a variety of ways. Commonly, geometric properties are described with drawings. Thus, a building or a street can be explained, depicted and constructed. Alternatively, observed behaviours can be described, as found in performance specifications. It is also possible to represent properties in terms of relationships between entities. For instance, in a spreadsheet, the value of a cell can be specified as the result of the calculation of other cell entries.

These calculations or descriptions need not be explicit. Responsive materials change their properties in reaction to the conditions around them. A thermostat will sense air temperature and control the flow of electric current and hence the temperature of the air. Using such techniques, artists have created reactive sculptures and architects have made sentient spaces; that is, spaces that react to the occupant or other factors: lights turn on if lux levels fall below a certain threshold, traffic flow is regulated according to need, walls move as users change location.

Using these ideas, connections to a variety of data or atmospheres can be established that serve as a basis for generating innovative urban forms and living environments. When designing urban space, it is usual to collect data on the type of urban qualities desired. These are then, for example, translated into master plans, which are themselves specific spatial descriptions. One can also define performance requirements for urban places, linking the description of the urban space to historical, experiential, financial, social, environmental or other factors.6

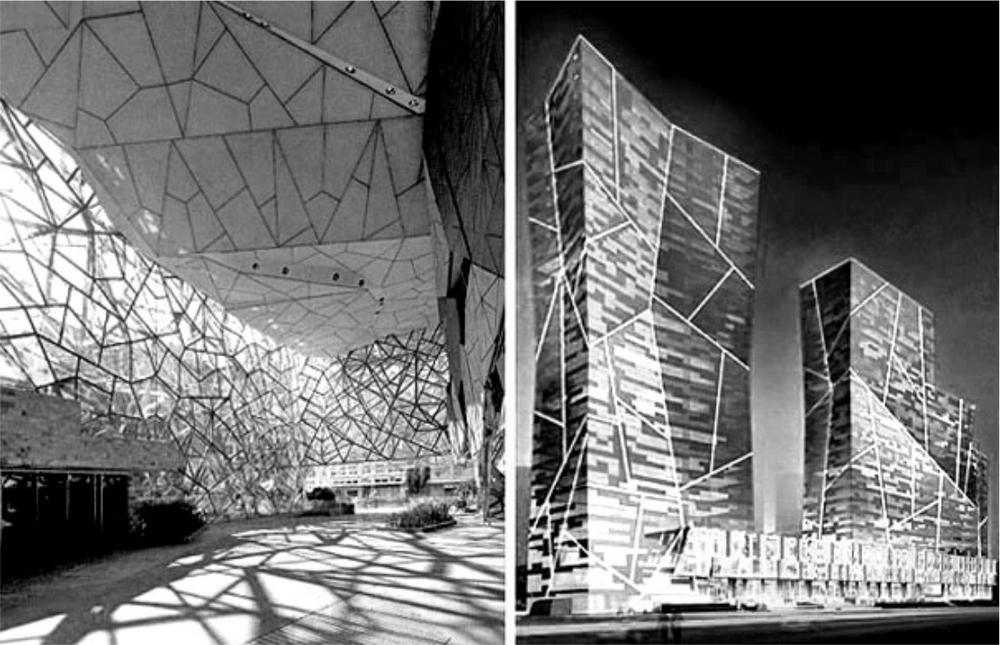

For the design of Federation Square in Melbourne, Australia (Figure 3, left), LAB Architecture Studio developed analogical building facades through the interactive application of sequential rules describing their visual characteristics both quantitatively and qualitatively.7 Their more recent designs of Beijing’s urban master plans at ‘SOHO Shang Du’ extend this idea even further (Figure 3, right). Rather than producing a master plan, LAB translated planning codes into a series of parametric design rules. The outcome both complies with and confounds the rigid regulations of traditional urban planning. As seen in the ‘favela’ neighbourhoods in Sao Paulo, Brazil, architects try to respond to the 189influence of functionalism and economics by rethinking urban parameters.8 They derive their parameters from the social context of the neighbourhood and its relationship to the urban context in order to create a model that embodies the constant change inherent within the favela.

FIGURE 3

LAB ARCHITECTS: FEDERATION SQUARE [LEFT], SOHO SHANG DU, BEIJING [RIGHT]

The Urban Islands Studio used this same thinking to explore and reconsider a distinctive site within Sydney’s urban context. Cockatoo Island is an ideal candidate for a parametric rethinking of its earlier development, which failed to anticipate changes that arose over the years, thereby excluding the island from the city.

As the basis of the investigation, the studio explored a distinctive abandoned land within the Sydney urban context. On this island, a variety of facilities and settings lie idle, awaiting redevelopment and integration into the urban context. Sydney’s pace of urbanisation, as well as its rate of growth, has had a strong impact on both its sense of place and sense of community. Urban planning in general does not foresee the real changes that occur over years of habitation. The Urban Islands 190Studio explored these issues, creating a new urban identity for the site and the city itself.9

URBAN PARAMETERS

The Urban Islands Studio was one of the Master Classes offered in the architecture program at the University of Sydney. Forty-five students elected to join the studio guided by international architects and held in August 2006. Its aim was to establish an architectural discourse with Cockatoo Island, the harbour and the city, and their historical and cultural context, and to communicate visions for reintegrating the island within the city’s fabric to a broader audience.

In their initial exploration, the participants collected data from the location. This discovery went beyond the traditional ‘site analysis’ and required students to relate their own interests in the project to data that arose from the ‘genius loci’ or its urban context. These parameters were informed by the site, and allowed a description of the site based on dependencies and the interconnected relationships between relevant information. The outcomes of these investigations led to personal interpretations of the site as well as a rethinking of urban parameters as a whole. The studio successfully dismantled the boundaries between theoretical and practical realms by focusing on multiple rather than single interactions.

In the next stage of the studio, the participants concentrated on understanding their design concepts and acquiring the skills of design communication, which allowed their concepts and theories to be interpreted. These developments were tested for specific conditions on Cockatoo Island and placed into its architectural framework. The result was not only an academic discussion, but also the broad involvement of all stakeholders as well as the public.

The participants then developed their design creations, reflections and communications into a comprehensive urban proposal. Using the data, their understanding and their recently acquired skills, the participants were able to establish and visualise their design in a variety of descriptive and multidimensional forms to create spatial expressions of their findings and explorations. The outcomes 191are strikingly powerful because they describe form by creating both dependencies and parameters that define the urban spaces as well as the landscape. Normally, urban settings are the passive result of the forms of the buildings around them.10 This studio, however, described generators that created external spaces, which then defined the building forms, resulting in the subtraction of open space from the urban space.

The individual outcomes varied from large-scale installations that responded to various light conditions over a 24-hour cycle (Figure 4), to very small interventions as specific locations on the island (Figure 5). However, all participants carefully maintained most of the abandoned structures and buildings on the island. The interventions combined and redivided spaces and buildings. They re-established relationships with the surrounding water and neighbourhoods on the shorelines opposite the island, and allowed soft responses to hard places. This stands in contrast to Sydney’s typical urban development, where relationships across the harbour—density, artificial structures and function—are erased, and new developments are isolated from their immediate surroundings11.

FIGURE 4

‘SOFT INVERSIONS’ INSTALLATION: LIGHTS, REFLECTION & SOUND

192 The studio concluded with a public seminar that brought together the various aspects and results of all participants into one cluster design. After two weeks of daily studio work, the students merged their individual designs and dependencies of urban strategies, components and rules into a single large design concept and strategy. These highly complex representations, however, cannot be communicated using traditional urban planning methods or tools. The synthesis of the final seminar created layers of descriptions and dependencies that are highly complex and interrelated. This resulted in a rethinking of urban parameters, allowing a seamless communication with a larger audience. Urban planners, architects, stakeholders and the general public were invited to review and discuss the outcomes of the studio. The variety of innovative statements of urban habitation and the living environment allowed the participants to amplify the impact of their generated design proposals beyond the shores of the island and far into the city itself. The students were not limited to their own knowledge or level of skills in order to express their design. At the same time, the audience could engage in a complex discussion about urban planning and design. The proposals presented by the students allowed quick access to a variety of solutions as well as their synthesis within the overall context.

FIGURE 5

POROELASTICITY: PETER CHRISTENSEN, SHUI KWAN, JONATHAN SPICER

193The variety of individual design proposals, as well as the large multifaceted urban design cluster for Cockatoo Island, demonstrated a high level of thinking that ended in the generation of compound designs. Each participant in the seminar contributed to both the micro and macro scale in order to create and rethink urban strategies. This method allowed innovative urban design to emerge.

RETHINKING

The Urban Islands Studio addressed novel concepts in the creation of urban design that can influence recent developments in architectural production. This partly experimental, partly realistic studio explored innovative methods of architectural expression, form finding and communication, and developed unconventional solutions. It coupled the in-depth studio-learning environment with a creative real-case scenario in order to close the gap between the studio environment and the application of knowledge. Hence, the studio relates to and reshapes urban design in general, just as Cockatoo Island can relate to and reshape the city. Additionally, it explored novel processes for the integration of compound urban design issues. The rethinking of urban parameters allowed the participants to create an innovative urban design language based on social and cultural descriptions.

One objective of the studio was to frame an intellectual research question linking to a variety of data to generate and integrate an urban form. A more interesting outcome derived from the ability to redefine and reframe the problem itself by stepping out from a preconception based on experience and exploring a set of unpredictable answers. These are higher levels of design problems. The framing of a problem at a higher level allows both a deeper investigation of the problem itself and a rethinking of the variables that contribute to a solution. The establishment of meta-rules creates a precise problem-framing that allows the reference of one problem or parameter to another one. As with our design studio, the outcomes illustrate how nonlinear design processes and re-representations of an idea can lead to successful and responsive design expressions that differ from conventional approaches to urban planning.194

Although the synthesis of all individual projects removed the students from individual ownership of their design, it also allowed them to reflect on their own as well as their colleagues’ designs as a whole cluster of contributions.12 This outcome relates to earlier research by design studios based on the same principle, whereby the design environment is applied outside the bounds of its normal prescribed purpose, and innovative design methods are deployed through the interplay of design with exploration.13

With the rethinking of urban design habitation, both culture and living experiences can act as generators of spatial dependencies and rules. The generated design can subsequently be linked to various ways of extracting or generating innovative urban forms and understandings (Figure 6). These descriptions can then be used directly in the communication and exploration of urban environments.14

FIGURE 6

RETHINKING URBAN PARAMETERS AS ABSTRACT DESCRIPTION

A holistic discussion about design, city, function and development allows its significance to be rephrased not only within architectural education, but also in all other dialogues involving spatial representations. This follows the tradition of artists and designers, who have always pushed creativity towards new definitions of creation itself and its cultural context. The Urban Islands Studio addressed and expressed important aspects of the urban development process. It marked the beginning of a rethinking of urban parameters in design processes, and it is to be continued.195

1 Urban Islands: Generating Tactics of Cultural Engagement, http://www.altogetherelsewhere.org/urbanislands, accessed 11/2006.

2 Kvan, T: 2004, Reasons to Stop Teaching CAAD, in ML Chiu (ed.), Digital Design Education, Garden City Publishing, Taipei, Taiwan.

3 Schnabel, MA: 2006, Architectural Parametric Designing, Communicating Space(s), 24th Conference Proceedings eCAADe Volos (Greece), pp. 216-221.

4 Karakiewicz, J: 2004, City as a Megastructure, in M. Jenks (ed.), Future Forms for Sustainable Cities, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

5 With permission from Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien.

6 Picon, A: 1997, Les Annales de la Recherche Urbaine, Le Temps du Cyborg dans la Ville Territoire, (77), pp. 72-77.

7 Davidson, P: 2006, The Regular Complex, NSK Wolfram Science Conference, Washington, DC, 16-18 June 2006, http://www.wolframscience.com/conference/2006/presentations/davidson.html.

8 Vanderfeesten, E: 2005, Confection for the Masses in a Parametric Design of a Modular Favela Structure, 8th International Conference on Design & Decision Support Systems in Architecture and Urban Planning, 4-7 July 2006, Eindhoven, The Netherlands.

9 Forrest, R, La Grange, A. and Yip, NM: 2002, Neighbourhood in a High Rise, High Density City: Some Observations on Contemporary Hong Kong, Centre for Neighbourhood Research, http://www.bristol.ac.uk/sps/cnrpaperspdf/cnr2pap.pdf.

10 Karakiewicz, J: 2004, Sustainable High-Density Environment, in Marchettini, N, CA Brebbia, E Tiezzi and LC Wdahwa (eds.), The Sustainable City III, WIT Press, Siena, pp. 21-30.

11 Toon, J and Falk, J (eds.): 2003, Sydney: Planning or Politics: Town Planning for Sydney Region since 1945, Planning Research Centre, University of Sydney, Sydney.

12 Kvan, T: 2000, Collaborative Design: What Is It?, Automation in Construction, 9 (4), pp. 409-415.

13 Schnabel, MA, Kvan, T, Kuan, S and Li, W: 2004, 3D Crossover: Exploring objets digitalisé, International Journal of Architectural Computing (IJAC), 2 (4), pp. 475-490.

14 Seichter, H and Schnabel, MA: 2005, Digital and Tangible Sensation: An Augmented Reality Urban Design Studio, in A Bhatt (ed.), Tenth International Conference on Computer Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Vol. 2, CAADRIA, New Delhi, India, pp. 193-202.