9

The health, economic, and policy implications of the ageing Korean society

Introduction

The Korean population is changing rapidly in two respects. First, as the ‘baby boomers’ grow older, Korean society is ageing faster than any other country. Korea is expected to turn into an ‘aged society’ only 18 years after it became an ‘ageing society’. In addition, rapid ageing in Korea is coupled with an unprecedented low fertility rate. Until two decades ago, Korea had propagated policies for lowering the fertility rate however now increasing the fertility rate is on top of the national policy agenda.

From a health perspective, rapid ageing means that the population’s health is likely to get worse than in the past, as older people tend to spend a greater proportion on health care than other sectors of the population, and will continue to be high spending for their health care needs This implies that the Korean health care system needs to be reformed to provide sufficient care for the elderly.

In this chapter the dynamic changes in Korea’s population as well as some of the efforts the government is making to deal with these changes will be addressed. It is hoped that this chapter will lead to active open discussions between Australia and Korea on the shared challenge of an ageing population.193

Socio-economic characteristics of the Korean elderly

The proportion of elderly people in Korea in 2000 was 7.2 per cent, which is lower than in many developed countries.1 However, the speed of ageing in Korea is striking. Table 9.1 shows that Korea will go from an ‘ageing society’ to an ‘aged society’ in only 18 years, and from an ‘aged society’ to a ‘super-aged society’ in only eight years. Coupled with the low fertility rate since the early 1990s, the old-age dependency ratio is expected to increase sharply.

Table 9.1. The age distributions and ageing indices of Korea

| 1980 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2018 | 2026 | |

| % | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 0~14 | 34.0 | 23.4 | 21.1 | 19.1 | 16.3 | 13.0 | 11.6 |

| 15~64 | 62.2 | 70.7 | 71.7 | 71.8 | 72.8 | 72.6 | 67.5 |

| 65 + | 3.8 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 10.9 | 14.3 | 20.8 |

| Old-age dependency ratio2 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 10.1 | 12.6 | 14.9 | 19.7 | 30.8 |

| Ageing index3 | 11.2 | 25.2 | 34.3 | 47.4 | 66.8 | 110.3 | 178.7 |

Source: KNSO, 1996

Labour force participation of the elderly is high in Korea compared to many developed countries. In 2004, 29.8 per cent of persons aged 65 and over were engaged in economic activities (Korea National Statistical Office, 2004). In comparison, in 2001

194the labour force participation rate of persons aged 65 and over in developed countries such as the US, UK, Canada and Australia was less than 10 per cent (UN, 2001). The high participation rate of Korea’s elderly reflects the weakness of the old-age income support system (including pensions and retirement programs).

The illiteracy rate of Korea’s elderly was estimated to be 7.8 per cent among 65–69 year-olds and 12.5 per cent among 70 year-olds and over (UN, 2001). These estimates fare better than similar statistics in China or Singapore. The education level of the Korean elderly continues to improve.

Health status of the elderly in Korea

The average life expectancy increased from 70.8 in 1989 to 77.5 in 2003. As Table 9.2 illustrates, life expectancies at ages 65 and 80 are comparable to those of several OECD countries.

Table 9.2. Life expectancies at age 65 and 80

| Life expectancy at age 65 | Life expectancy at age 80 | |||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Australia | 17.6 | 21.0 | 7.9 | 9.7 |

| Canada | 17.2 | 20.6 | 7.9 | 9.7 |

| Japan | 18.0 | 23.0 | 8.3 | 11.0 |

| Korea | 14.9 | 18.7 | 6.6 | 8.1 |

| United States | 16.6 | 19.5 | 7.8 | 9.4 |

Source: OECD Health Data 2005

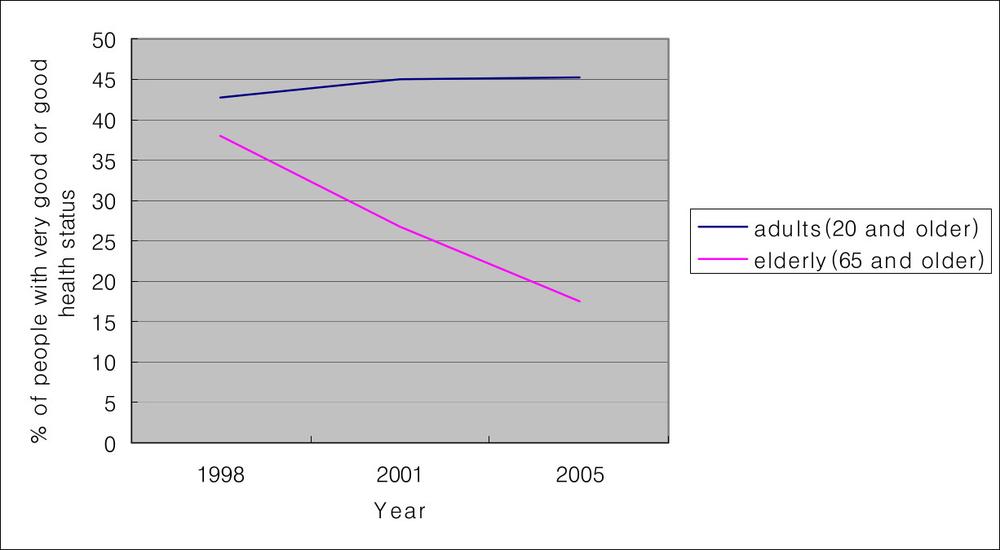

Even though general health continues to improve, improvements in the quality of health of older people is dubious. According to the National Health and Nutrition Survey (Figure 9.1 below), the subjective health status of adults overall has become better, but the subjective health status among the 195elderly has become worse. This is evident when the decline in the health status of the elderly is compared with the health status of young and middle-aged adults, which has improved substantially. Figure 9.1 (below) supports this analysis – it tells us that the subjective health status of the elderly needs more attention from policy makers and researchers.

Figure 9.1. Changes of subjective health status among the elderly

Data source: 1998, 2001, 2005 National Health and Nutrition Survey, Ministry of Health and Welfare

In many developed countries, including Australia, where the government has long intervened on behalf of the elderly, the health status of the elderly is now improving. In these countries, ageing does not necessarily mean higher medical expenditure or costs. However, if the Korean Government does not start to develop appropriate ways to improve the health condition of the elderly, ageing will place heavy economic burdens on current and future generations.

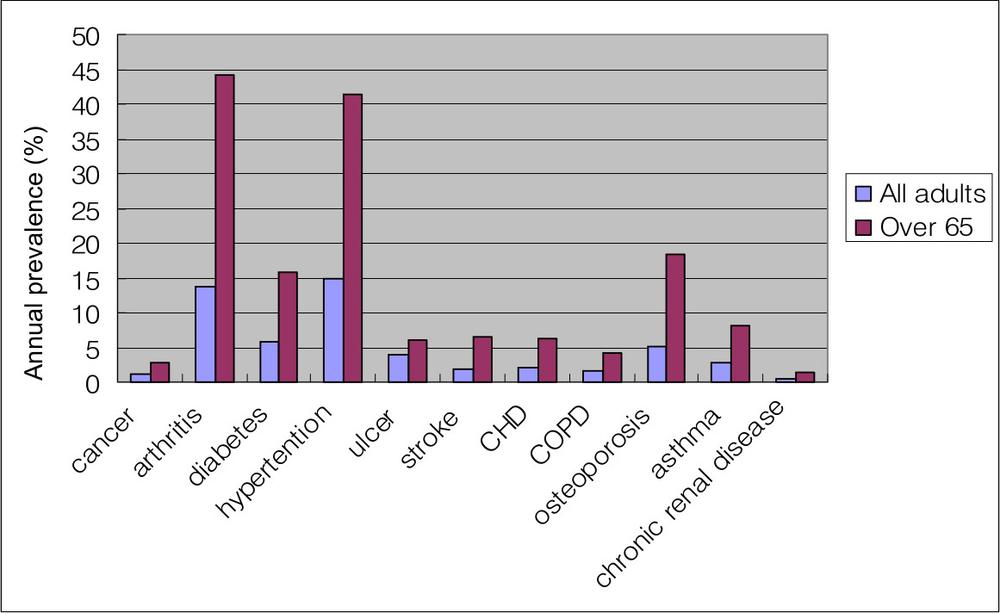

Given the lack of attention to the quality of health for older people as a core social policy issue in Korea, it is not surprising that Korea’s elderly have many chronic diseases, because chronic 196diseases are related to a lower subjective health status (Leinonen et al, 1998). Some of the most prevalent chronic diseases are arthritis, hypertension, osteoporosis, and diabetes (Figure 9.2 below). The pain suffered from arthritis negatively affects the overall quality of life and health care costs for hypertension and diabetes were ranked the first and the third highest among various diseases in Korea in 1999. Both the visible and invisible costs of such chronic diseases are largely borne by elderly themselves whereas society should also bear the cost. (Kim et al, 2003). In order to enhance elderly people’s quality of life and reduce the economic burden of managing disease, early interventions for preventing chronic diseases are required.

Figure 9.2. Prevalent chronic diseases among the elderly

Data source: 2005 Health and Nutrition Survey, Ministry of Health and Welfare

197Economic burdens from the health care services for the Korean elderly

Health care expenditure as a percentage of GDP in Korea is about six per cent, which is relatively small compared to that of other OECD countries. One of the mechanisms by which Korea has been able to control health care expenditure is via its national health insurance system whereby physician fee schedules and hospital reimbursement rates have been determined by the government.4 However, for older people macro-efficiency through government regulation is difficult to endure given the rapidly rising medical costs. One of the reasons for rapidly rising medical costs is the increase in the elderly population, which has greater medical needs than other age groups.

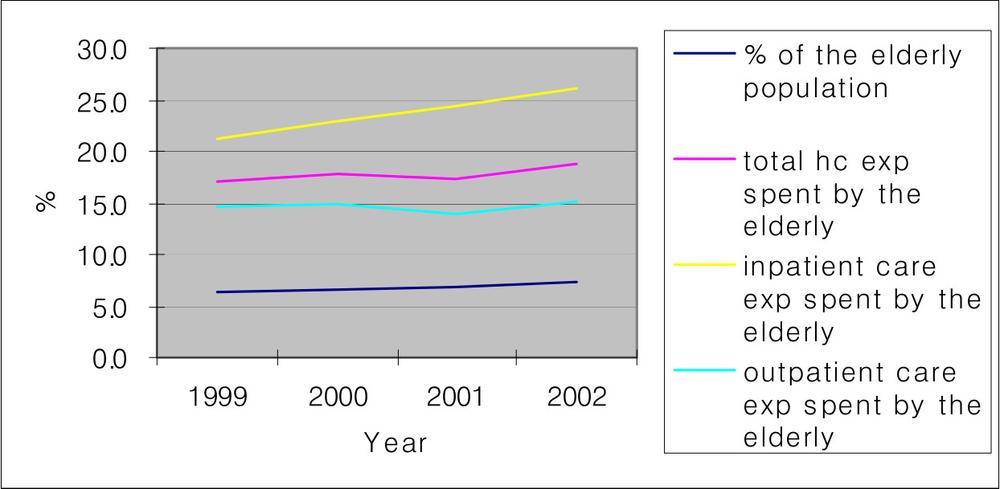

In 2002, although the proportion of the elderly was only about seven per cent, the proportion of health care expenditure on the elderly ranged from 15 to 26 per cent. In particular, expenditure on inpatient care for the elderly is increasing faster than the proportion of the older population. Rising inpatient costs may be due to both the provider’s practice fees and the higher demand for services brought on by the deteriorating health status of the elderly. Since about 80 per cent of health care providers are from the private sector, and physician fees are based on a fee-for-service principle, they are likely to provide unnecessary and/or expensive services. Assuming that the health care needs of the elderly will not decrease in the near future, strong governmental intervention is necessary if this trend in health care expenditure is to be reversed.

198

Figure 9.3. Total, inpatient, and outpatient health care expenditures of the elderly

Data source: Statistics of National Health Insurance, National Health Insurance Corporation, 2003.

The rapidly rising inpatient costs for the elderly are also related to a lack of long-term care facilities. Many chronically ill elderly patients, who otherwise would have been admitted to a less costly long-term care facility, are admitted to acute care hospitals. Existing long-term care facilities are mainly for the indigent. Only 0.2 per cent of the elderly in Korea received institutional services in 2000 (OECD, 2005). Although there is poor data on the amount of long-term care expenditure in Korea, the OECD has estimated that about 0.3 per cent of GDP goes to long-term care (OECD, 2005). Among OECD countries, long-term care expenditure on average is 1.25 per cent of GDP.

The lack of long-term care facilities means that long-term care is usually provided informally at home. Even though its true that many older people in Korea would prefer to stay at home rather than be admitted to a residential facility, they often do not have the choice to do anything but stay at home. Furthermore, relying on informal care can be problematic, especially for those 199who need help but live alone (Jeong et al, 2001). The number of elderly people living in a one-person household increased from 8.9 per cent in 1990 to 16.2 per cent in 2000 (Korea National Statistical Office, 2004). Over the same period, the number of elderly living in a three-generation household decreased from 49.6 per cent to 30.8 per cent, reflecting a widespread shift away from extended family living.

Women have greater responsibilities than men when it comes to providing informal care for the elderly. A national survey showed that 74.3 per cent of caregivers were females in Korea (Jeong et al, 2001) and they too have health and welfare needs Almost 60 per cent of caregivers reported that their health was not good, and 10 per cent even had health conditions that limited their care activities. Generally caregivers had received no help for their own health problems (31.4 per cent) nor for errands or shopping (41.3 per cent). Therefore, in addition to the need for more long-term care facilities, there is a great need for housekeeping services, day care, respite care, and bathing services for family caregivers as well as the elderly.

Korea’s strong family values play an important role in family care giving. Ninety-two percent of caregivers regarded caring for an older family member as their children’s responsibility, and 80 per cent of them thought that such a sacrifice contributed to the harmony of their family. However, as nuclear families and women’s economic participation increase, these strong family-oriented values are likely to be undermined (Jeong et al, 2001).5

Recent long-term care policies in Korea

The government has been making efforts to adapt to the rapidly ageing population, even though Korea is not an aged society yet.

200As mentioned above, the Korean Government recognises that we cannot rely on family caregivers any more, because of the increase in nuclear families and women’s economic activities. In response, the current administration is taking two major steps to develop a better long-term care policy.

The so-called ‘Elderly Care Act’ was proposed in 2006 and was subject to a period of public scrutiny. This law is expected to be enacted in 2007 and to be effective from 2008. The purpose of the ‘Elderly Care Act’ is to improve the quality of life of the elderly and to reduce the burden on families. The target group includes the elderly as well as those who are younger than 65 but have ‘geriatric diseases’ such as dementia and stroke.

To finance additional care services for the elderly, a separate health insurance premium will be levied from people who participate in the national health insurance scheme. Fifty per cent of the budget for elderly care will come from this premium, 30 per cent from general tax revenue, and 20 per cent from individuals’ out-of-pocket payments. Low-income families will be able to use elderly care services at a reduced out-of-pocket rate.

The National Health Insurance Corporation will be responsible for the management and operation of these elderly care services. Its responsibilities will include screening people who enrol in the scheme, collecting premiums, reviewing and subsidising fees, approving care facilities and disseminating information about them. The ‘Elderly Care Act’ supports the principle of ‘consumer choice’ in the selection of benefits and provides for as many kinds of benefits as possible. The services it covers include home care, institutional care, and care allowance.

A further issue is the need to maintain the quality of elderly care services. A national study is currently underway by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs that aims to develop appropriate tools for evaluating the quality of health of users of elderly care services. Another study is being planned to test the feasibility and acceptability of the tools in practice. However, it is not clear at this stage how to carry out monitoring the quality of 201care and to reflect the quality indicators to the reimbursement for providing services.

A second major step for improving long-term care for the elderly is an effort by the National Health Insurance Corporation to increase the number of long-term care facilities, which will be in great demand when the ‘Elderly Care Act’ becomes effective. Starting in 2005, the National Health Insurance Corporation has been increasing the number of long-term care facilities by 100 per year. In addition, homes support services such as home-visit caregivers, caregiver vouchers and monetary assistance for low-income long-term care users will be also provided. However, it has not been decided which professionals will provide which long-term care services; therefore it is not easy to predict what the demand for certain professionals will be.

Even though the government’s initiatives to improve long-term care for the elderly are promising, there remain many unresolved challenges that Korea will have to deal with in the near future. These challenges can be summarised as: continuity of care, quality control, and financial security.

The current Act fails to specify how medical care services and long-term care services will be seamlessly provided. Since long-term care insurance is separate from the health insurance, it is debatable which insurance covers ‘in-between’ services such as home-visit nursing prescribed by a doctor and nursing or medical observations at day care facilities or short-term care facilities.

Although quality of care is one of the key principles of long-term care in Korea, it is not clear how the National Health Insurance Corporation will manage and organise the quality control system. It is doubtful that a highly centralised organisation like the National Health Insurance Corporation will be able to effectively deliver local services such as screening participants in the scheme and monitoring the health condition of the beneficiaries of funds. There needs to be a focus on how to increase local governments’ responsibility for 202quality control as well as how they might provide corresponding financial support.

Also questionable is the financial security of the long-term care insurance system. Based on Japan’s experience, once the long-term care insurance system started, the demand for long-term care services unexpectedly increased. On the other hand, it is difficult to raise the premium rate to address the need for increased funds, after the inception of the insurance program. In the past, Korea has experienced financial crises in its national health insurance. In order to secure the ongoing financial viability of long-term care insurance, the proportion of the general tax revenue dedicated to this fund needs to increase.

Policy implications and conclusions

Korea is an ageing society. To cope with its ageing population, it must face many challenges, including rapidly rising health care expenditure, a weakening of family values, the economic participation of women, and so on. The introduction of long-term care insurance is, in this context, a promising action by the government. However, since Korea has little experience in delivering long-term care, the need for research into the affordability, accessibility, and quality of care of the new system is significant. The Korean Government has made a commitment to fine-tune the long-term care system to ensure continuous quality care and sustainable financing leading up to when the system begins in 2008.

Among many objectives that Korea wants to meet in addressing the needs of an ageing population, the improvement of the health of the elderly must be the ultimate goal. However, a substantial focus should also be placed on the quality of life of older people rather than on the quantity of life in order that older Koreans can live a longer and healthy life. The prevention of chronic diseases early in a person’s life, and rehabilitation through long-term care when a person suffers a disability, are two of the key principles for healthy ageing. Some initiatives 203have been taken in this regard, such as the introduction of ‘the Health Promotion Fund’ from levying tobacco tax in 2004, as a way of paying for the health costs of smoking. This has resulted in the provision of various health promotion programs in both private and public sectors.

Apart from the health care system, pensions and retirement programs should also be strengthened. Nearly 30 per cent of the elderly still work to derive an income. If this situation does not change dramatically, it may be necessary to engage economically active seniors in long-term care not as recipients but as service managers or providers. In this way, the issues of a lack of long-term care personnel and the increasing number of elderly people with insufficient incomes can be resolved at the same time.

In conclusion, Korea is changing rapidly, both in its demographic composition and in its health care policies. In 2008, one of the biggest experiments in Korean health care history will begin with the implementation of the Elderly Care Act, reflecting Korea’s ambition to overcome the challenges that lay ahead, with the ultimate goal of improving the health status of the whole population, but especially the aged.

204

References

Jeong K, Jo A, Oh, Y and Sunwoo D, 2001. Caregiving conditions and welfare needs of the elderly who are eligible for long-term care. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, Seoul.

Khoo S-E & McDonald P. The Transformation of Australia's Population, 1970-2030. UNSW Press, Sydney, pp 77–103.

Kim J, Bae S, Park I, Gu M and Hong S, 2003. Analysis of medical expenditure of the elderly by disease-focused on the 50 high cost diseases. National Health Insurance Corporation, Seoul.

Leinonen R, Heikkinen E and Jylhä M, 1998. Self-rated health and self-assessed change in health in elderly men and women-a five year longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 46, pp 591–7.

Ministry of Health and Welfare, 1999. 1998 National Health and Nutrition Survey Results. Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2002. 2001 National Health and Nutrition Survey Results, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

Ministry of Health and Welfare, unpublished. 2005 National Health and Nutrition Survey Results, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

OECD – see Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2005. Long-term Care for Older People.

The Elderly Care Act 2005, Ministry of Health and Welfare.

The National Health Insurance Corporation, 2003. Statistics of national health insurance, Seoul.205

Korea National Statistical Office, 2004. Yearbook of the Household Survey, Seoul.

Korea National Statistical Office, 1996. Future Estimated Population, Seoul.

UN – see United Nations.

United Nations, 2001. World Population Ageing 1950–2050, www.globalaging.org/ruralaging/world/ageingo.htm, accessed 20 August 2007.

1 According to World Population Ageing 1950–2050 (UN, 2001), the percentage of people 65 and over in 2000 was 15.8 in UK, 12.3 in US, 11.7 in New Zealand, 17.2 in Japan, 16.4 in Germany, 12.6 in Canada, and 12.3 in Australia.

2 Pop. 65 years old & over / 100 persons aged 15 to 64.

3 Pop. 60 years old & over/100 persons under age 15.

4 However, fee schedules are decided from 2001 by the negotiation between the government (National Health Insurance Corporation) and a group of medical and pharmaceutical representatives.

5 The current issue of the low fertility rate is evidence of this change in values.