10

The wider context: some key implications of generational change in Asia

Introduction

Asia is undergoing a tremendous change impelled by the rise of a new political and economic leadership, and the emergence of new social formations. After independence and during the Cold War, leaders of countries in the Asia Pacific region emerged from the ranks of military, bureaucratic and political elites. During this era of relative stability and fast paced economic development, at least two factors were certain: the views of the leadership and their political inclination. In the next few years this is set to change. A new generation (35–50 years old) is now coming into positions of political, economic and military influence and leadership. Within the region’s social dynamics, rapid transformation driven by the growing influence of the 20- and 30-year-olds is beginning to exert political and economic influence over their country’s development. They’re young, cosmopolitan, mostly Western educated, globalised in their thinking and high spenders. Asia’s generational transition and social transformation raises new questions about how the region will develop in the next five to 10 years and its implications for Australia. For Australia it will be increasingly important to track, understand and act on these changes as we continue to identify more strongly with the region.

As a conclusion to this book this chapter will widen the perspective beyond two key nations and explore some of the changes taking place in Asia as the geographical and social context that brings Australia and Korea together. This chapter will focus on the social and political aspects of generational change in Asia, particularly on the emergence of new leadership and the inextricably intertwined changing social formations that 207have emerged. There are some clear messages that can be taken from the work of the researchers from Australia and Korea whose work has been presented in the previous chapters. These messages relate primarily to challenges of generational change within the countries and some of the key social issues that have emerged, challenging both their governments and broader societies. The way these changes are addressed will rely on the stability and capacities of leaders in government throughout the Asian region, thus highlighting the importance of how the region more broadly is affected by generational change. The issues of generational change affecting the governance and political direction of the region are the same generational issues discussed in the previous chapters – the digital generation, the sandwich generation and the ageing population are making demands on leadership and government and are crucial issues for political and economic stability in the region.

Leadership in transition

In Korea, the 2002 election of outsider, President Roh Moohyun, marked the completion of Kim Dae Jung's presidency and the end of a political generation. Roh represented the first post-war generation politician to head the nation. He symbolised liberals, favouring economic equality and a more autonomous foreign policy, while his rival, Lee Hoi-chang, stood for the ruling political elites who tended to be traditional and conservatives in their thinking. Roh’s rise, on the one hand was viewed as a victory of reform, post-cold war sentiment and anti-regionalism (Hoon Juang, 2003). Others attribute the victory also to the use of the Internet as a powerful media in mobilising a younger generation in support.

At the core of this generational shift in Korean politics is the emergence of what is dubbed the ‘386’ generation. About 20 of President Roh’s top advisers are 386ers. (Lee, 2006) The number three represents those in their late 30s; young and hungry for power and influence. The number eight represents the 1980s when they attended University during a tumultuous 208period in Korean history, the shift from dictatorship to democracy, and the number six represents the 1960s, when they were born during the era of rapid Korean industrialisation. They are highly educated, digitally adept, entrepreneurial and form the backbone and the policy force in Rho's administration. The 386 generation is more conspicuously cautious about embracing the dictates of the United States, especially in relation to their belligerent northern neighbour, North Korea. They are idealistically determined to root out corruption and are seeking to develop closer relations with China and Japan (Sunhyuk & Wonhyuk, 2007).

In China, the ‘fourth generation’ of leaders has formally assumed power. The first generation of leaders was represented by Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, leaders that started the People’s Republic of China. A common characteristic of the first generation leaders is that they tended to be both political and military leaders, educated in China and involved in the Long March, Chinese Civil War and the Second Sino-Japanese War. The second generation was represented by leaders involved in the Chinese revolution but in junior roles such as Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yu, Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang. Unlike the first generation many of the second generation were educated overseas. The third generation however were leaders born before the revolution, educated overseas, mostly in the Soviet Union, and were either political or military leaders. The third generation included Jiang Zemin, Li Peng, Zhu Rongji and Liu Ruihuan.

The current crop of leaders, known as the ‘fourth generation’ or the ‘republican generation’ are aged in their late 50s and early 60s, are much younger than their elders who assumed leadership positions in their late 60s and early 70s. The republican generation includes current president, Hu Jintao, Wen Jiabao, Zeng Qinhong and Wu Bangguo. Cheng Li suggests that collectively the fourth generation of leaders is less dogmatic, more capable and more diversified (2001:17). The majority of 209the leaders grew up during the Cultural Revolution, many acquiring their first political experience during the revolution.

They grew up in a political environment characterised by idealism, collectivism, moralism and radicalism. They were taught to sacrifice themselves for socialism. But as time passed, their faith was eroded and their dreams shattered (2001: 18).

The fourth generation leaders, suggests Cheng Li, are more diversified than previous generations in terms of political solidarity and occupational backgrounds. Cheng Li’s study of 522 high-ranking leaders in the fourth generation shows that about half of them joined the Party during the decade of the Cultural Revolution. Another 35 per cent joined the Party before, and 15 per cent joined after the Cultural Revolution. (There is roughly a 15-year span between the oldest and youngest members of the fourth generation.) Unlike the previous generation that shared strong bonding experiences such as the Long March and the Anti-Japanese War, the fourth generation of leaders lack political solidarity and a willingness to commit to the existing political system (2001: 18).

This new power cohort has shed its ideological baggage, is better educated than its predecessors and more supportive of economic and political reform. While in previous years the most important posts in China’s financial system were usually occupied by Soviet-trained engineers, today’s leaders are technocrats. There are more financial experts and lawyers in the fourth generation than in previous generations. At their heels are the ‘fifth generation’, in their 30s to 40s. Educated in elite universities in the European Union and the United States, they are reputedly liberal in their outlook and are already attaining ministerial status.

In Japan, in September 2006, 51-year-old Shinzo Abe was elected by a special session of Japan’s National Diet to replace retiring Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. In a country where power is based on seniority and rank, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is 210Japan’s youngest post-World War II prime minister and the first born after the war. His ascension to power is owed largely to three factors: his family pedigree: his father served as foreign minister in the 1980s and his grandfather was prime minister in the 1950s; his hawkish position on Japan foreign policy, particularly his nationalist stance on North Korea and Japan’s broader military activism in East Asia; and his youthful appeal and energy needed to reignite Japan’s reform.

Under Prime Minister Abe, Japan is becoming more ‘muscular in its rhetoric and posture’. Under this rising regional assertive tendency is a new generation of political leadership. A new political generation called the Heisei generation is now on the road to political ascension. Heisei is used to describe the current era name in Japan. The Heisei, which refers to seeking peace at home and abroad, emerged at the end of the Cold War in 1989 and after the death of Emperor Hirohito the same year. His successor, Emperor Akihito chose the name ‘Heisei’ to symbolise his reign. Under the Heisei era, a new generation of leaders emerged, who strongly supported Koizumi’s reform. Kenneth Pyle observes Koizumi’s unusual decision to make his cabinet appointments irrespective of factional politics and to reach policy decisions more independent of the LDP party council reflected the predilection of younger party members (Pyle, 2006: 26). Young Japanese coming to maturity in the Heisei years, adds Pyle (2006), are experiencing the kind of decisive change that gives rise to a new political generation.

The rest of Asia is not far behind this type of generational change in political leadership. In the past couple of years, Singapore has allocated key cabinet posts such as finance, defence and information technology to younger ministerial candidates. The prime ministerial succession is already in place for 2007. In Indonesia, the ‘cowboys’ that brought down Abdurrahman Wahid are moving into key political positions. These young and affluent players claim to hate corruption and are seen by many as the ‘new hope’ for dismantling the Suhartoera structures.211

The young leaders of Asia share a range of characteristics regardless of their political affiliation. They grew up in a peaceful and prosperous region and have no living memory of the Second World War and its aftermath. Ito Joichi, a young Internet entrepreneur and venture capitalist, born in 1966, wrote in 2005 on the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombings: The bombings don’t really matter to me, or, for that matter, to most Japanese of my generation. My peers and I have little hatred or blame in our hearts for the Americans…My grandparents’ generation remembers the suffering, but tries to forget it. My parents’ generation still does not trust the military. The pacifist stance of that generation comes in great part from the mistrust of the Japanese military…For my generation, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings and the war in general now represent the equivalent of a cultural ‘game over’ or ‘reset’ button. Through a combination of conscious policy and unconscious culture, the painful memories and images of the war have lost their context, surfacing only as twisted echoes in our subculture. The result, for better and worse, is that 60 years after Hiroshima, we dwell more on the future than the past (as cited in Pyle, 2006: 29).

They’re mostly western educated, appeal to a young constituency, and are more assertive and less dedicated to the status quo. They are more concerned about the future and pay less attention to the past. They appear to be increasingly nationalistic but are in fact more assertive about their nation’s self identity and the need to pursue its own interest even if it means dissenting from greater global powers.

Asia’s next generation of leaders will face four defining policy challenges. They need to respond to social forces unleashed by the economic reforms of the past decade; creatively accommodate and cope with an acutely organised, complex and robust society; innovatively respond to the dilemmas of the new economy driven by technology and communications; address the 212needs of changing demographics, particularly the ageing of their populations and; navigate the challenges of global ‘terrorism’ and global economic volatility.

Social and political transformation

When discussing issues around generational changes in Asia, three themes seem to emerge: the contrast between traditionalism and modernisation stemming from the increasing global awareness of the younger generation and the consequent widening gap between the younger and older generations; the transformation in value systems and political attitudes; and a shift in consumption and the increasing influence of new technologies (Song, 2003; Beech, 2004; Marshall, 2003; Nhu-Ngoc Ong, 2004: 1–4; Fahey, 2003: 82–5).

Tradition and modernity

Generational change across Asia has brought about a situation of contrast and confrontation between tradition and modernity. As younger generations move into positions of social, political and economic significance, a major issue they face is the role tradition has in an increasingly modern Asia (Fahey, 2003: 82–5; Nhu-Ngoc Ong, 2004:1; Song, 2003). Many Asian youth are becoming disillusioned with the older generations’ inability to solve social problems and the inherent cronyism and corruption within governments. Such disillusionment widens the gap between the young and the old leading to social and political repercussions.

As mentioned above, what is interesting about Roh’s propulsion to Korea’s highest office is that it was driven in large part by the mobilisation of a younger generation. Young voters between the ages of 20-39 came to account for more than half of the whole electorate for the first time in South Korean history. This age group outnumbered Roh’s opponent by more then 20 per cent and occupied almost half (48 per cent) of the entire vote, helping Roh secure a victory by 2.3 per cent of the vote. This so-called 213 ‘20/30 generation’, suggests Hoon Juang (2003), constituted the majority of ‘red devils’ who frenziedly rooted for their team during its 2002 World Cup victories. Half a million ‘red devils’ filled the squares in front of the Seoul City Hall and Gwangwhamoon every time the home team took the field. When a United States military court delivered a not guilty verdict to US soldiers who were driving vehicles that killed two Korean schoolgirls, the 20/30 generation spearheaded nationwide anti-American protests that have continued since November 2002. “Soccer fans and anti-American protesters both represent the national pride, self-determination, and self-expression of a new generation” (Hoon Jaung, 2003: 4).

The election of a political outsider in Korea seems to reflect a revolt against tradition and the elite political establishment. The preference for leadership change is driven, in part, by two important variables: the aspiration of the younger generation determined to escape from old customs and old fashioned habits in an era of fast pace economic growth; and the discontentment with the older generation’s perceived ‘passive and conservative actions’ in dealing with social problems. In his observation of the Korean election, Ho Keun Song (2003) suggested that the youth push for Roh was merely to remove tradition and the ‘gentlemen’s club’ in ‘revolt against achievement and legacy of the old generation’. The tendency was instead to mobilise and promote what he refers to as the ‘commoner-oriented sentiment in politics and society’, a sentiment that emphasises human rights, equality and justice.

A similar changing attitude is occurring within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as a result of generational change. Freeman (2003) for example, argues that while major policy departures are unlikely, ‘incremental, orderly change’ has begun to take place in the hope of improving the government’s ability to handle social issues. Freeman (2003) discussed the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) crisis as an example of the government’s failure to handle an emergency due to its reversion to traditional ways of controlling information. During 214the crisis, the Chinese government attempted to cover up the severity of the situation announcing that the number of cases was 1500 with only 67 fatalities. However, China’s health ministry later reported that the nationwide death toll from SARS stood at 79, with 1807 confirmed cases (Gittings, 2003). The younger generation are realising the need to adopt more modern processes within government and in relation to the control and diffusion of information.

Western colonialism and numerous civil wars throughout the region have had a tremendous impact on Asian politics and social institutions. The process of modernisation has been particularly fast paced, leaving people in the region very little time to adjust (Nhu-Ngoc Ong, 2004:1). Despite the absence of wars and conflicts, Asia’s younger generation has experienced transitions from a ‘traditional society to a post-industrial society in a single generation’ (Fahey, 2003: 82). “Unprecedented economic and technological change throughout Asia has made it difficult for Asian culture and politics to ‘keep up’, this having a deep impact on younger generations who are attempting to forge a sense of national and person identity” (2003: 82). As such, the question of tradition versus modernisation is particularly significant to the phenomenon of generational change.

Song (2003:5) has attempted to address the compatibility of tradition and modernity in his observations of the election of President Roh. He argues that what is occurring in Korea is a situation of ‘cultural strife’, a ‘generational mission against the legacy of high-speed growth’ through which the younger generation is trying to construct a form of ‘symbolic power’ for their generation. He argues that fast-paced change implemented by his generation has resulted in a younger generation that are directly opposed to fast paced change and all things associated with it (including ‘traditional’ processes of government) (Song, 2003:19). He states that:215

The main purpose of cultural strife is to overthrow all inheritance from authoritarian, cold war, and growth-first ideology as shackle of free imagination and uncurbed exploration to future utilizing information technology (Song, 2003:8).

Thus, while Song (2003:10–12) describes ‘cultural strife’ as a form of rebellion against the older generation, he also provides numerous points that legitimise the younger generation’s changing attitudes to tradition and modernisation. Song’s analysis is useful as it highlights one reaction to generational change from within Asia, thus providing insight into how generational change in politics is having an impact on the region.

At another level, Hutzler (2002) discusses the influence of globalisation and Westernisation on generational change in China, posing the question of the extent to which traditional Chinese institutions and values are compatible with Western values and institutions. Hutzler suggests that a prominent issue facing the new generation of leaders in China will be how they handle dealing with the West, and govern ‘China’s increasingly complex and close relationship with the rest of the world’. Similarly, some observers look at the possibility of a ‘hybrid’ solution as younger generations become more globally aware – the notion that Asian youth wish to remain ‘a little bit East, a little bit West’ when looking at issues of society and politics (Hill, 2003; Nhu-Ngoc Ong, 2004: 1).

What indeed seems to be the consensus is that generational change in Asia is resulting in the development of a younger generation that is much more globally aware, and much more sensitive to the possibility of merging modern Western ways of doing things with more traditional customs and institutions. However, there are many questions surrounding the implications of tradition and modernity and the widening distance between generations for the phenomenon of generational change in Asia. ‘Will the next generation lead their 216countries toward political pluralism or increased nationalism? Will growing anti-Americanism among the young in Korea and Japan give rise to a more politically powerful China globally? How will young peoples’ dissatisfaction with authoritarian governments as well as corrupt political parties in the new democracies play out?’ Generational change (particularly in terms of the relationship between tradition and modernity) as it affects international economic and security architecture, is so significant that it is relevant to ask what impact this will have on Australia. Will it be easier to do business if Asia is more open to Western economic structures? As it is still uncertain how the changing role of tradition and modernity within Asia will affect Australia, this area requires further research.

Transformations in value systems and political attitudes

Fewsmith (2002) suggests that generational succession is always important, because different generations have different formative experiences, different expectations about the world, and different types of training on which to draw when dealing with problems. Generational change in Asia is characterised by a significant alteration of value systems that are reflected in the political attitudes of the younger generation. The process of democratisation and globalisation taking place throughout the region are having a vast impact on how the younger generation view themselves. Asian youth are becoming more aware of Asia’s growing relationship with the rest of the world. An increasingly high percentage of the younger generation are benefiting from the opportunity of studying overseas in Western institutions. They are becoming more open-minded and adaptive, post-material, increasingly individualistic and much more concerned with issues of social welfare (Marshall, 2003; Nhu-Ngoc Ong, 2004: 1). In Japan for example, the transforming value system is represented by young people who are less driven by the all-consuming work ethic characteristic of their parents’ fears of poverty. They are much more concerned with personal 217fulfilment and share distaste for hierarchy and convention in the workplace (Marshall, 2003).

Recent discussions on generational change in the region examined the development of post-materialism, focusing on the situation of ‘cultural strife’ in South Korea. Song (2003:10–12) for example, describes rapid economic development and social differentiation as major contributing factors to changing value systems, as political freedom and market competition have become central to the younger generation. Song (2003:11) highlights the desire to shift from ‘hard politics’ to ‘soft politics’, as the younger generation is increasingly concerned with issues of human rights, peace, gender equality, and environmental protection. The election of President Roh is symbolic of this change in values, reflecting the shift of policy weight to distribution and social welfare for lower classes:

It is apparent that the Roh government’s utmost goal is to promote social integration and remedy social displacement by improving distributive justice and fulfilling essential aspects of post-material values (Song, 2003:15).

Fahey (2003) also discusses the influence of changing value systems on political attitudes, describing the younger generation’s political agenda as being concerned with challenges to obligation and patriarchy within the family and workplace; engagement with and responses to globalisation; and tendencies towards nationalism, anti-Americanism and democracy (Fahey, 2003: 85).

A study conducted by The Centre for Strategic and International Studies in 2002 on the implications for the United States of generational change in Japan provides a very detailed investigation of the phenomenon of generational change. According to the study, young leaders in Japan share common characteristics regardless of their political affiliation: they grew up in a relatively peaceful and prosperous period, having no living memory of the Second World War or its aftermath. They 218are arguably more assertive and less committed to the status quo. They are more concerned with the future and less concerned with the past. They are increasingly nationalistic, attempting to forge a Japanese identity and greater international role. They are, however, unable to clearly articulate Japanese national interests and goals, or provide a clear blueprint for political and economic reform. In contrast to previous generations, they do not feel burdened by Japanese history, believing instead that Japan should come to terms with its past and move forward (The Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 2002: 3).

According to Fahey, the Post-Tiananmen square generation in China has become more nationalistic, expressing dissatisfaction with their government for not protecting them against international humiliation (2003: 92). Post World War II tensions still exist within China in younger generations, however they are manifested differently than in previous generations (Fahey, 2003: 84; Sutter, 2002). According to Sutter, current negativity in the Sino-Japanese relationship has developed due to ‘strong and often growing areas of mutual interest’ (Sutter, 2002). Relative weakening of Japanese economic performance and political leadership has ‘coincided’ with an increase in Chinese power and influence in Asian affairs. Within China, these tensions have evolved from Chinese leaders’ focus on Japan as having victimised China in the past, thus linking it to the recent promotion of nationalism within China (Sutter, 2002).

Another issue related to changing value systems stems from the increasing role of international education. According to current literature, a common experience shared by the younger generation across Asia is that of overseas education in Western institutions (Fahey, 2003: 83; Sebastian, 2003; Song, 2003; The Economist, 2004). As a result, this generation has been increasingly exposed to Western economic and political procedures and social institutions. A significant question that must be asked is what impact this will have on Australia. Does culture in terms of international business become less important or less of a barrier?219

Technology and consumption

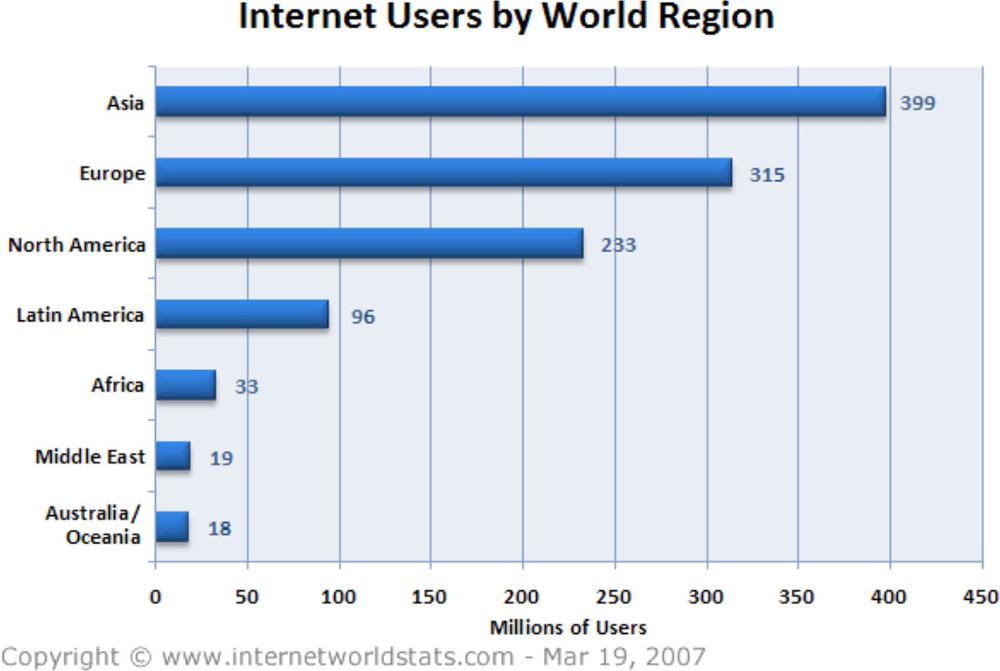

Figure 10.1. Internet users by world region

Source: Internet World Stats 2007

The role of technology and consumption is the third significant theme in a discussion about generational change in Asia. In the latest data on Internet usage, Asia has the highest number of Internet users with nearly 400 million users compared with Europe with 315 million and North America with 233 million users. Throughout Asia, more people are gaining access to the Internet and are buying mobile phones. This is resulting in a revolution in the way people (in particular younger generations) communicate and relate to their society, as these new technologies are providing a new space for interaction (Fahey 2003; McMahon, 2004; Song, 2003). As previously discussed, Asian youth are very much engaged with politics (Fahey, 2003: 83) and are now beginning to challenge issues in a new public sphere – cyberspace. The Internet and mobile phones (text 220messaging) are increasingly being used to discuss social and political issues and even to influence elections. New technologies make communication between large numbers of people across long distances relatively easy and fast, providing greater freedom of information (Song, 2003). Asia’s new generation has been described as ‘technologically savvy’ due to their propensity for this new technology. Approximately two thirds of the South Korean population utilise the Internet, and across Asia in general, new jobs in digital technology are being created, making the ideal of lifelong employment old-fashioned.

Fahey (2003) in her study, ‘Generational Change and Cyberpolitics in Asia’ provides a detailed introduction to the profusion of new technology in Asia and the impact this is having on society and politics. Fahey proposes that new technology, the Internet (especially chat rooms) and text messaging are providing a new social forum that is separate from both government regulation and the older generation. Younger generations are using new technology to express opinions, launch campaigns, report on events, et cetera (Fahey 2003: 105). Fahey sees this new public sphere are being central to generational change as for the first time transnational communication is easily accessible, thus altering the dimensions and structure of public space (2003: 90–91). Fahey describes the Internet as significant as it involves “costless reproduction, is decentralised, and [allows] instantaneous dissemination of information” and, as such, has revolutionised political activity throughout Asia (2003: 104). As stated above, the election of President Roh, exemplifies the use of new technology and political participation. Song argues that the Internet provides a ‘generational voice’ for younger generations, stating that the use of the Internet and text messaging to assist with the election of Roh was aimed at ‘mobilising generational solidarity’ (2003:9). Internet demonstrations in South Korea were so powerful that they assisted with the fall of the ‘gentleman’s club’ from the centre of politics and society. The use of text messaging, ‘blogging’, online campaign audio/videos are increasingly 221becoming a norm during elections. Similarly, the Internet and text messaging have been used in Indonesia and China to challenge various points of authority and to affect political activity. Whether the Internet creates a new form of democracy in Asia remains to be seen. There have been numerous attempts by governments to cordon off and limit the use of the Internet in political mobilisation.

The rapid infiltration and use of new technology has also resulted in a transformation within consumerism in Asia. This in itself is significant as it illustrates the impact of younger generations on the larger economic sphere. Younger generations are gaining increasingly wider access to new technology and as a result desire greater control over what they buy and the services they use. As recently reported in The Korea Times (2005) there is a new generation of consumers, labelled ‘prosumers’ due to their increasing tendency to be involved in the consumption process. This reflects an analysis of the changing behaviour of young consumers in Korea, calling them ‘generation C ers’ due to their creativity and changing consumption habits (The Korea Times, 2005). There is apparently a current shift away from passive, straightforward consumption within younger generations to customisation or even co-production of products (The Korea Times, 2005). As such, generation ‘C’ has ‘transformed marketing into a two-way conversation’ between corporations and consumers, as consumption becomes all about ‘you’ (The Korea Times, 2005). This transformation of consumerism will have an increasing impact on the economic sphere as newer technologies become available. An important question arises for Australia: how will this transformation affect Australia in terms of Australia’s import and export markets with Asia?

While the protrusion of new technologies and the changing nature of consumerism have resulted in increased creativity, individualism and greater communication across Asia, there are also numerous negative implications within this facet of generational change. At present, access to the Internet and 222mobile phones is not equal throughout Asia or even within nations, this ‘digital divide’ being cause by differences in ‘income, age and gender’ (Fahey, 2003:97–8). Between different areas in China there is a formidable wealth-divide (Hill, 2003) resulting in certain groups being excluded from the benefits of new technology and social formations (McMahon, 2004). Similarly, there is a limited penetration of new technology within Southeast Asia, and as such the use of the Internet and mobile phone for political purposes is restricted to the urban elite (Fahey, 2003: 95). In Malaysia, while most youth enjoy a high level of affluence and tend to be ‘technologically savvy’, there is a large sector of rural youth whose basic needs are not being met (AASSREC Conference, 2003: 1). In addition, the Internet and mobile phones are largely inaccessible to older generations throughout the region, resulting in a division between younger and older generations. Here, Fahey acknowledges the potential social problems posed by the digital divide (2003: 98). If, as Fahey suggests, new technology (such as the Internet and mobile phones) becomes the major form of political engagement and democracy development (assuming democracy is the chosen path), groups excluded from access to new technologies may feel even further disenfranchised (2003: 98). The impact of the digital divide thus requires further investigation in terms of its social, political and economic repercussions, as well as its implications for Australia-Asia relations.

Conclusion

As a rounding off of the range of issues raised in this book on the impact of generational change in Australia and Korea, this chapter has mapped out a number of key discussions involved in a region in transition. It has also highlighted a number of research gaps in studies on the impact of generational change in Asia. For example, there is little to no research on how ‘generational change’ has affected the foreign policy of Asian countries. More research also needs to be conducted on how ‘generational change in Asia’ will affect Australia in terms of 223economic, political, and cultural relations. Further, more empirical data needs to be developed on trends in changes in attitudes to political and economic relations, and social problems that can be used to back up current conclusions. Finally, there is currently a significant imbalance in the amount of information on China and Japan compared to any other country, demonstrating a great need for research to be conducted on the causes and consequences of generational change in other Asian countries.

Within a specific context, this book examines the social policy challenges emerging as a result of demographic shifts taking place in Australia and Korea. It specifically considers some of the social and demographic changes in both countries with a particular focus on addressing their demographic make-up and the common challenges of decreasing fertility rates, the ageing population and the need for improved health care systems. It also addresses the issue of technology and its impact on the digital generation – those born between 1979 and 1994. This generation is the beneficiary of the economic boom of the late 80s and 90s and has been brought up in an era of excessive mobile phone use and of ubiquitous, fast and cheap access to Internet. This book has also examined the generation sandwiched between ageing parents who need care and their own children. ‘Chewed at both ends’, they struggle to support ageing parents and pay for the education of their children. There is indeed a need to rethink child care and family support schemes and the traditional role of women as homemaker. Finally, the book addresses how society will cope with the changing health and financial needs of an ageing population. How will economies increase productivity so that shrinking workforces can maintain expanding pool of retirees? What policy changes need to be made to adjust to these changing demographics?

Current debates and discussions on social policy tend to compare Australia with the United States and the United Kingdom. This book attempts to redress that imbalance by 224offering new perspectives of Australian society through a comparison with South Korea, in light of the importance of the relationship between the two nations. There still remain a great number of issues related to generational change that need to be examined hopefully this book has made that step towards addressing some of them.

225

References

Bates Gill J, Morrison S and Thompson D, 2004. Defusing China’s time bomb: Sustaining the momentum of China’s HIV/AIDS response [online], 13–18 April. Washington DC: Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Available from: http://www.csis.org/media/csis/pubs/040413_china_aids.pdf [accessed 6 January 2007].

Beech H, 2004. The new radicals, Time, January 26. Available from: http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,582466-2,00.html [accessed 14 December 2006].

Fahey S, 2005, Generational change and cyberpolitics in Asia, in Fay Gale and Stephanie Fahey (eds.), Youth in transition: The challenges of generational change in Asia, Proceedings of the 15th Biennial General Conference, Association of Asian Social Science Research Council & Academy of Social Science Australia, Canberra, pp 89–107.

Gale F & Fahey S (eds.), 2005. Youth in transition: The challenges of generational change in Asia, Proceedings of the 15th Biennial General Conference, Association of Asian Social Science Research Council & Academy of Social Science Australia, Canberra.

Fewsmith J, 2002. Generational Transition in China. The Washington Quarterly, 25 (4), p 23.

Freeman D, 2003. China’s new leaders face challenge. EurAsia, 7 (4).

Gittings J, 2003. China says SARS outbreak is 10 times worse than admitted, The Guardian. Available from:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/sars/story/0,13036,940372,00.html [accessed 14 November 2006].226

Hills S, 2003. Challenges for the fourth generation, Business Asia, April. Available from: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BJT/is_3_11/ai_102451313 [accessed 27 October 2006].

Hennock M, 2002. Inside China’s ‘Me’ generation. BBC News [online], 6 November. Available from:

http://news.bbc.uk/2/hi/business/2403661.stm [accessed 15 July 2006].

Hoon Jaung, 2003. President Roh Moo-hyun and the new politics of South Korea. Asia Society [online], February. http://www.asiasociety.org/publications/update_korea2.html [accessed 5 December 2006].

Hutzler C, 2002. China’s new generation of leaders keep a low profile as they push for reforms [online]. Available from: http://tin.le.org/vault/wireless/china.new.generation.html [accessed 21 October 2007].

In-Yong Rhee, 2003. The Korean election shows a shift in media power, Nileman Reports, International Journalism, Spring 2003. Available from:http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb3330/is_200303/ai_n8049115 [accessed 3 December 2006]

Jackson Richard, 2005. Preparing for China’s aging challenge [online], 1 May. Washington DC: Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Available from: http://www.csis.org/component/option,com_csis_pubs/task,view/id,885/type,1/ [accessed 15 November 2006].

Kim S and Lim W, 2007. How to deal with South Korea. The Washington Quarterly, 30 (2), pp 71–82.

Li Cheng, 2001. China’s political succession: Four misconceptions in the West, Asia Program Special Report, The Wilson Centre, No. 96, June, pp17–23. Available from: http://wwics.si.edu/topics/pubs/asiarpt_096.pdf [accessed 5 January 2007].227

Lee B J, 2006. South Korea: Too much activism, Newsweek International Edition [online], November 27. Available from: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15790420/site/newsweek/ [accessed 15 January 2007].

Marshall A, 2003. Can the Class of ’89 fix Japan? Time [online], 16 June. Available from: http://time.com/time/asia/2003/class89/story.html on 10/06/03] [accessed 15 January 2007].

McMahon D, 2004. Taming China’s Nationalist Tiger. Business Asia, April. Available from: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BJT/is_2_11/ai_99987078 [accessed 15 June 2006].

Nathan A J and Gilley B, 2002. The Fourth Generation. The Australian Financial Review, 11 October, pp 1–2, 11.

Nhu-Ngoc Ong, 2004. Changes in Attitudes toward Democracy among Asian Generations. Conference on Citizens, Democracy and Markets around the Pacific Rim, March 19–20. Honolulu, Center for the Study of Democracy, UC Irvine, the University of Missouri.

Pyle K B, 2006. Abe Shinzo and Japan’s change of course, NBR Analysis, 17 (4), p 26.

Sebastian E, 2003. Asia’s next generation – point of view. Business Asia, August. Available from: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0BJT/is_7_11/ai_109402858 [accessed 9 March 2004].

Song H K, 2003. Politics, generation and the making of new leadership in South Korea. Paper presented at conference Korea Re-examined: New Society, New Politics, New Economy? Research Institute for Asia and the Pacific, University of Sydney, Sydney, 23 February, pp 1–15 unpublished.

Sutter R, 2002. China and Japan: trouble ahead? The Washington Quarterly, 25:4, pp 37-49.

The Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 2002. Generational Change in Japan: its implications for US-Japan 228Relations, August. Available from: http://www.csis.org/media/csis/pubs/genchangejapan.pdf [accessed 15 March 2006].

The Economist, 2004. The end of tycoons. The Economist [online], 27 April. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb5037/is_200004/ai_n18276363 [accessed 25 March 2005].

Trendwatching.com, 2005. http://www.trendwatching.com/about/inmedia/articles/generation_c/digital_generation_leads_new_m.html [accessed 25 March 2005].

Author unknown, 2005. Digital Generation Leads New Marketing Patterns. The Korea Times, 25 January.