>meta name="googlebot" content="noindex, nofollow, noarchive" />

4

Framing responsibility: global firms’ environmental motivations

Abstract

A recurring theme in international political economy is that responsibility for regulation is moving from the public to the private sphere, particularly from states to globally integrated markets. One of the clearest cases of this is multinational corporations (MNCs) increasingly adopting codes of conduct for the impact of their activities, including environmental impacts. MNCs also produce reports in which they present their environmental credentials. However, by analysing the reports of the most global MNCs, this chapter finds that the institutional basis of capitalist relations in firms’ home states is a key determiner of their environmental motivations. This reflects, and supports, the insights of the Varieties of Capitalism Approach. It suggests that, rather than conceiving of firms’ environmental motivations as global, even the most global firms view their environmental responsibilities through national lenses that reflect, and support, certain national institutional preferences over others.

Introduction

Multinational corporations (MNCs) are perhaps the most important economic actors shaping the contemporary global economy. Their dominance of world production, trade and investment is such that 50 per cent of the world’s largest economic units are MNCs (measured by sales revenues), and the other 50 per cent are nation states (measured by gross national product) (Dicken 2003 p. 274). As MNCs rival states in their command of material resources, there is no shortage of 96commentary asserting that globally integrated markets, in which MNCs are the main players, are increasingly more powerful than nation states. Nobody has made the case more clearly, or colourfully, since Strange declared that markets are now “the masters over the governments of states” (Strange 1996, p. 4), with states themselves increasingly “merely the handmaidens of firms” (Strange 1997, p. 184). This point was so obvious to her that she said everyone knew it to be the case except academics, declaring that “the common sense of common people is a better guide to understanding than most of the academic theories being taught in universities” (Strange 1996, p. 3). As the rhetoric of globalisation began to take hold in the 1990s, commentators analysing the implications began to see it as unavoidable that business, as the “most powerful institution on the planet” and therefore the “dominant institution in society” must “take responsibility” for its actions (Korten quoted in Lawrence, Weber & Post 2005, p. 47).

Against this backdrop, the OECD (2001b) has noted a growing profusion of corporate codes of conduct since the 1990s, with MNCs the primary source. This phenomenon is characterised by many authors as a rise in the importance of private authority, because it is MNCs themselves that are establishing the rules by which they face their public obligations, rather than nation states or international organisations regulating to impose these obligations on them (e.g. see the contributions in Cutler, Haufler & Porter 1999). This raises the question: just what is it that is motivating firms in the commitments they are making? The claim made in this chapter is that rather than global convergence, significant motivational differences for codes of conduct exist between firms. That different firms should be driven by different imperatives is not surprising. However, the analysis presented in this chapter demonstrates two important points. First, the differences between firms are based on the location of their home state, not the markets they dominate, nor where they make most of their sales, and not even necessarily where most of their assets and employees are located. Secondly, even highly global firms demonstrate this trend. This points to the enduring importance of national interests in MNCs’ codes of conduct, or more accurately, the enduring importance of firms’ nationality even when their operations and material interests are global.

97To focus the analysis, this chapter examines firms’ statements with respect to environmental responsibility. However, the intention is not to analyse the environmental initiatives of MNCs. This is done, most accessibly on a sector-by-sector basis, by others (e.g. with respect to the auto industry see Austin et al 2003; OECD 2004; UNEP & ACEA 2000). The question of whether such initiatives represent real commitments or merely ‘greenwashing’ is not a debate entered into either. It too is considered elsewhere, such as in Mikler (2005)1. Instead, the purpose here is to focus on what MNCs themselves say is driving them to take environmental initiatives, and therefore how they themselves perceive the environmental impact of their products and their role in ameliorating this impact. The contention is that the home states of MNCs are, from an institutional perspective, particularly central to how they approach the question of addressing the environmental impacts of their activities.

The analysis proceeds as follows. First, the case is made for focusing specifically on firm’s motivations with respect to the environment. Corporate responsibility is too large a ‘playing field’ on which to consider the questions, so environmental responsibility is the focus of empirical analysis. The increasing relevance of environmental responsibility to public, as well as private actors is highlighted. Secondly, the case is made for why an institutional approach to the question of environmental responsibility is warranted, as opposed to the mainstream rationalist liberal economic approach. Thirdly, the enduring institutional importance of firms’ home states is outlined, as suggested by the Varieties of Capitalism (VOC) approach (e.g. see Hall & Soskice 2001). Finally, the results of a content analysis of the top five global German, US and Japanese MNCs’ environmental/sustainability or corporate citizenship reports is presented. These firms are the most global in the sense they have the highest transnationality indexes (TNIs) – i.e. they have high proportions of their total assets, sales and employment located outside their home state.

98The analysis highlights the enduring importance of national institutional variations in capitalist relations for firms’ motivations. This is despite the firms chosen being the most global in their operations and interests. The US firms remain most focused on the material drivers of market forces. However, other modes of coordinating activity are of greater importance for the German and Japanese firms. The German firms display a predisposition for a partnership approach with the state which incorporates a desire to proactively promote regulations and regulatory targets. The Japanese firms are driven by a concern for a broader range of stakeholders and a deep sense of their responsibility to society. They are greatly concerned about their social standing, or their place in society, that goes well beyond instrumental material goals. The German firms share this predisposition, albeit to a lesser extent.

While there may be ongoing debate about ensuring that the commitments of firms are real, the debate about nationally appropriate and conducive paths to environmental commitments must therefore also be a key consideration. Even as business becomes more global, national institutions affect the manner in which firms of different nationalities perceive their interests in addressing environmental problems. Rather than a universal, global solution to the environmental impact of business, or visions of global codes of conduct, a variety of approaches depending on firms’ nationalities is appropriate: market forces and market mechanisms for US firms; close state–business cooperation and coordination for German firms, with society as a key stakeholder in the process; and strategies through which business and society drive the process for Japanese firms reflecting firms’ deep awareness of their social obligations.

Environmental responsibility

Firms’ claims concerning their responsibilities extend across a broad landscape, encompassing a diverse range of areas. This makes understanding firms’ motivations for their codes of conduct problematic. Inevitably, one confronts the notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR), which exacerbates the problem because of a lack of definitional clarity. ‘CSR’ is often used interchangeably with other terms, such as ‘corporate sustainability’, ‘corporate responsibility’ or ‘corporate 99citizenship’. Although the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has stated that environmental sustainability and CSR are separate fields (UNEP 2002), they are regarded as inseparable in much of the literature and by firms themselves (e.g. see Florini 2003a, 2003b; OECD 2001a). In particular, the OECD says environmental sustainability is a sub-category of CSR along with labour standards, human rights, disclosure of information, corporate governance, public safety, privacy protection and consumer protection (OECD, 2001a).2 The business case for CSR is put by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) which agrees with a broader definition that encompasses human rights, employee rights, supplier relations, community involvement and environmental protection (Holliday, Schmidheiny & Watts 2002; WBCSD 1998, 2000).

Why focus on the environmental aspects of CSR – i.e. a small sub-set of the whole? Apart from tractability for the sake of analysis, the first reason is the growing international significance of environmental issues. International organisations have significantly raised the profile of environmental concerns since the early 1990s. For example, the UNEP views the 1992 Rio Earth Summit3 as a watershed in the discussion of environmental sustainability from which sustainable development initiatives have sprung, such as the high profile Kyoto Protocol signed in 1997 and subsequently ratified by nearly all its signatories.4 Even the World Trade Organization (WTO) recognises that “environment, gender and labour concerns are on the agenda in ways that would have been deemed illegitimate in the 1970s” (O’Brien et al, 2000, p. 231). The WTO therefore established its Committee on Trade and Environment in 1995 at its inception. At the same time, throughout the 1990s a series of international agreements with business also emerged. One of these is the Global Compact, announced in 1999, which brings companies together with UN agencies, labour and civil society to support nine principles in

100the areas of human rights, labour and the environment. Another agreement is the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), started in 1997 by the Coalition of Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES) and now an official collaborating centre of the UNEP that works in cooperation with the UN’s Global Compact (GRI 2002; UN, n. d. b).

Secondly, commentators such as Florini (2003a, 2003b) identify CSR as having come to the fore as an ideological shift that started in the 1990s. Indeed, there is a growing body of research that shows environmental sustainability, along with other socially responsible behaviour on the part of MNCs, to be driven by voluntary initiatives. Such initiatives are further identified as being a global phenomenon. In the area of environmental responsibility, the WBCSD was established at the same time as the 1992 Rio Earth Summit and has been working ever since to be at the forefront of the business response to sustainable development. It is a coalition of 165 companies drawn from 30 countries and 20 industry sectors. It also links a network of 43 national and regional business councils and partner organisations in 39 countries. Thus, it may be said to be a manifestation of a broader acceptance by corporations of the importance of environmental issues as a key component of CSR that commenced in the 1990s (Florini 2003a, 2003b; Holliday, Schmidheiny & Watts 2002; Karliner 1997; OECD 2001a, 2001b).5

Thirdly, outspoken critics of international capitalism, regarding the environment, suggest that we are actually witnessing a fundamental change in how firms do business worldwide as they incorporate environmental sustainability concerns in their operations. For example, before the mid-1990s any action to address environmental concerns was a response to social activism or government regulations, rather than the industry taking action proactively (Hawken, Lovins & Lovins 1999 p. 24). Indeed, in 1993 David Suzuki, a strident critic of capitalism, globalisation and the environmental degradation in which it results worldwide, declared: 101

Environmentally responsible corporations may seem like an oxymoron. But as pressure by ecologically aware consumers and activists increases, more and more businesses are cloaking themselves in green rhetoric. How genuine is it or can it be? (Suzuki 1993, p. 135)

His answer in 1993 was that it was not genuine, and that “the ground rules of profit make it hard to be a friend to the environment” so that “amid…the suicidal demand for steady growth, happy stories are few” (Suzuki 1993, p. 135). But by 2002 he notes a philosophical shift within corporate hierarchies manifested in attitudinal changes, such as General Motors supporting a 50 per cent tax on petrol for environmental reasons (Suzuki & Dressel 2002, p. 289–290). He similarly applauds the attitudinal change within Ford, quoting its Chairman who said in his speech to a Greenpeace business conference on 5 October 2000:

We’re at a crucial point in the world’s history. Our oceans and forests are suffering; species are disappearing; the climate is changing…Enlightened corporations are beginning to…realise that they can no longer separate themselves from what is going on around them. That, ultimately, they can only be as successful as the communities and the world that they exist in … I personally believe that sustainability is the most important issue facing the automotive industry in general in the 21st century (Suzuki & Dressel 2002, p. 290–291)

Within the space of one decade, Suzuki’s attitude changed from pessimism to a decidedly more optimistic view of the possibilities for business environmental responsibility.6

Finally, environmental reporting by firms in many cases preceded reporting on CSR more generally.7 Starting in the late 1980s to early 1990s, an increasing number of large corporations, mostly MNCs, began producing such reports. These reports represent a desire by firms to represent themselves as environmentally concerned (whether in image or

102fact) suggesting an increase in the strategic importance of environmental considerations during this time period.

Given the increasing global visibility of environmental concerns, and the importance of environmental responsibility as a key sub-category within CSR more broadly, the question of how to conceptualise firms’ motivations to address their environmental impacts arises. The case for an institutional approach to answering this question is made in the following section.

Material ‘calculus’ versus institutional ‘culture’

The key assumption in mainstream liberal economic approaches is rationality, defined in terms of a priori assumed self-interest (Crane & Amawi 1997; Green & Shapiro 1994; Helleiner 2003; Ordeshook, 1993).8 They are seen as primarily employing “instrumental logics of calculation (calculus logics)” to achieve their material ends (Hay 2006a; see also Hay 2006b; March & Olsen 1989, 1998). The mainstream view is therefore fundamentally based on a materialist perspective in which firms act instrumentally to make profits in markets. They may also act to increase their power, but it is their material power in terms of market outcomes. This is the basis on which rationality is assumed: rational choice defined in terms of materialist profit and power maximising outcomes.

Environmental problems are usually characterised as cases of market failure due to externalities (the classic papers are Coase 1960; Hardin 1968).9 Environmental externalities cause market failure because the environment is often ignored by markets. Therefore, the price of goods and services does not reflect the environmental impacts of their production and consumption. This is because economic actors lack property rights over the environment, meaning they can ignore the

103negative environmental effects of their actions. The cost of environmental externalities is often borne by others who were not responsible for them. This is highly likely because the environment is often a public good in the sense that it may be jointly consumed by several agents at the same time. When the public good attribute of the environment is a global or transborder phenomenon, as is often the case, then the environment is said to be in the realm of the ‘global commons’. Far from market failure being the exception, “environmental externalities are pervasive” (Ekins et al 1994, p. 7). What then might motivate firms to address their environmental impacts? The standard answer to this question follows the logic of the firm conceived as a rational agent that employs an instrumental logic of material calculus in order to maximise returns.10 Therefore, the material factors of market forces and effective state regulation are to the fore.

The materialist perspective has proved to be a parsimonious way of explaining economic actors’ behaviour, including the behaviour of individuals, firms, states and international relations between states. However, it is challenged by analyses that are grounded more in institutional perspectives. Institutional perspectives have been promoted by scholars such as North (1990), March and Olsen (1989, 1998), and even Goldstein and Keohane (1993). The materialist, rational choice based approach has been modified (e.g. Denzau & North 1994) or attacked in the process (see Blyth 1997, 2003; Hay 2002, 2004; Green & Shapiro 1994). The body of literature on institutional theoretical approaches has now grown to the point where there are a variety of theoretical approaches embracing institutionalism, from those that emphasise the contextual or historically constructed nature of rationality, to those that virtually discard rationality altogether to focus on cultural and identity aspects – that is agency (Hay 2006b; Lowndes 2002).11 What they have in common is that, at the very least, they do not define actors’ rationality in terms of a priori assumptions ascribing actors’ motivations.

104Instead, their starting point is that actors are motivated by certain norms that prescribe and proscribe appropriate action. When such norms become institutionalised, they have a taken-for-‘grantedness’ about them so that behaving in a manner commensurate with them may be taken for ‘rational’ behaviour, but not necessarily rational behaviour in the liberal economic sense. In short, they apply “norm-driven logics of appropriateness (cultural logics)” (Hay 2006a; see also Hay 2006b; March & Olsen 1989, 1998).

Liberal economic versus institutional perspectives are therefore delineated by the manner in which rational choice is applied in the former, versus the role of norms of behaviour in the latter. Followers of the mainstream liberal economic perspective understand the world in terms of material interests, with actors acting as if applying a material calculus based on a logic of consequentialism (the outcomes of taking certain courses of action), whereas institutionalists accentuate the role of ideas and social behaviour (i.e. norms) based on a logic of appropriateness (i.e. that there is an appropriate way to act not necessarily contingent on the outcome of such behaviour) (March & Olsen 1989, 1998; Hasenclever Mayer & Rittberg 1997). The following section outlines how an institutional perspective may be applied to MNCs, and makes the case for why this should be done at a national rather than global level as argued by the VOC approach.

National perceptions of interests: the institutional importance of firms’ home states and the varieties of capitalism approach

Before discussing the implications of institutional perspectives, a simple and clear definition of the terms is required. North defines ‘norms’ as “shared common beliefs” that give rise to ‘institutions’ defined as “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally … the humanly devised constraints that shape interaction” (North 1990, p. 3 and p. 14). A more specific definition of the institutions to which norms give rise is provided by Hall and Soskice who say institutions are “a set of rules, formal or informal, that actors generally follow, whether for normative, cognitive, or material reasons” (Hall & Soskice 2001, p. 9). Institutional 105perspectives thus challenge the rational choice mechanism in the liberal economic model by seeing the role of ideas, beliefs and the resulting norms of behaviour – i.e. socially appropriate ways of behaving – as providing richer explanations of how decisions are made and institutions constructed.

In institutional, as well material terms, MNCs are not ‘placeless’ entities. As Dicken notes, they are “produced through an intricate process of embedding in which the cognitive, cultural, social, political and economic characteristics of the national home base play a dominant part” (Dicken 1998, p. 196). Although it would be an over-simplification to say that all MNCs from one home state are the same, firms from the same home state share certain national characteristics. In this light, the VOC approach is an institutional approach which observes that different capitalist states have different histories, cultures and structures that inform the nature of their capitalist relations, and that far from convergence on a single (liberal) global model, the persistence of different national institutional potentials gives rise to the persistence of different national capitalisms (Berger 1996; Boyer 1996; Coates 2005; Dore 2000; Dore, Lazonik & O’Sullivan 1999; Hall and Soskice, 2001).

Given their different institutional potentials, the VOC approach sees capitalist states as lying on a continuum between liberal market economies (LMEs) and coordinated market economies (CMEs). The United States is seen as the archetypal LME, while Germany and Japan are CMEs. While these are all capitalist countries, their institutions establish different ‘rules of the game’. This has implications for how environmental problems are addressed, and indeed the success or otherwise of strategies for addressing them, because of the underlying idea that “in any national economy, firms will gravitate towards the mode of coordination for which there is institutional support” (Hall & Soskice, 2001, p. 8–9).

Broadly speaking, firms in LMEs coordinate their activities via hierarchically organised firms competing in markets. In preferring market coordination of economic activity, they make their decisions based on market signals that define shorter-term profit levels. In regulatory terms, they therefore prefer deregulation over heavier state 106guidance and intervention. When they are subject to regulation, firms in LMEs will react more efficiently to clearly specified regulations, especially those aimed at altering market price signals.

Firms in CMEs are characterised by more non-market cooperative relationships to coordinate economic activity. It is not primarily the market and its price signals that determine their behaviour, but relationships based on cooperative networks. Firms in CMEs tend more towards consensus decision-making between a greater range of stakeholders internal and external to the firm based on long-established networks. They will react more efficiently to regulations based on negotiated and agreed rules and standards (Hall & Soskice 2001).

Obviously, the division between firms favouring deregulated market competition in LMEs versus cooperative coordination in CMEs is a very broad one. Underlying this divide are a myriad of aspects, the nuances of which are discussed by Hall and Soskice (2001) and others (e.g. Dore 2000; Doremus et al 1999; Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, 1993; Pauly & Reich 1997; Vitols 2001;).12 The ones most applicable to the analysis here relate to state–business relations and the role of markets. The major divide between LMEs and CMEs with respect to state–business relations is the extent to which the state and business cooperate to achieve mutual objectives. Firms in LMEs tend to pressure their governments for deregulation. They believe in free markets operating on laissez faire principles unless there is a clear case for state intervention due to market failure (the similarities with the liberal economic model are therefore obvious). By contrast, firms in CMEs expect the state to be an activist one, a partner in the market with them. As a result, in addition to being strategically coordinated by markets, firms in CMEs are to a large extent also state-coordinated.

The nature of state-business relations is related to the divide between LMEs and CMEs on the role of markets. A belief in minimal government intervention and laissez faire principles in LMEs leads to a preference for markets as organisers of economic activity. This is true in both the product (i.e. goods and services) and financial spheres. In CMEs, state-business cooperation and coordination to achieve mutual

107objectives is reflected in a view that markets are one among a variety of mechanisms for organising economic activity on a more relational, cooperative basis. This means that while firms in LMEs act on market signals to make profits in the short term and pay dividends to shareholders, firms in CMEs act to enhance their reputation through closer relational ties with external stakeholders (e.g. social groups and society more generally) and internal stakeholders (e.g. employees and other related firms) and thereby also become economically successful.

The key overall point is that, as the WBCSD notes, these institutional differences determine how environmental issues are addressed in different states, the extent to which corporations take the lead in encouraging change and the type of action they take (WBCSD 2004). Institutional differences suggest that, in addition to the material factors of market forces and state regulation, normative questions of social concerns and internal company beliefs should also be the subject of enquiry. The latter should be particularly relevant for CME-based firms.

Analysis of firms’ reports

Germany, the United States and Japan are the world’s largest economies. This is true in terms of gross national product, as well as manufacturing production, exports and imports. They are also the top three states for services imports and are ranked in the top five for services exports (Dicken, 2003). Furthermore, there is a significant established body of literature demonstrating the institutional importance of firms’ home states with respect to these three economically dominant states (e. g. see Doremus et. al. 1999; Pauly & Reich, 1997). With this in mind, five MNCs each from Germany, the United States and Japan were chosen and the contents of their latest reports as at November 2006 analysed.13

The aim of analysing firms’ environmental reports is to comparatively judge German, US and Japanese firms’ rationales for their environmental initiatives. Of course, firms’ environmental reports are not an objective representation of firms’ attitudes. By definition, objective measures of attitude are unachievable precisely because attitudes are always subjective

108phenomena. What these reports represent is the culmination of the efforts of teams of people qualified in, and responsible for, presenting information that casts their firm in the best possible light. There are therefore two important reasons for examining them. First, what is of interest here is what firms from different states, and indeed the same state, perceive as constituting ‘the best possible light’. These reports present firms’ understanding of how their environmental strategies should be ‘best’ presented. Secondly, because considerable effort goes into publishing a written report, it presents what each company believes to be its key messages. While it is true that all the firms examined have websites containing environmental information, these are updated regularly and change over time. However, a written report endures and presents, in one comprehensive document, the activities a firm believes are most important to communicate for the period it covers.

The firms chosen were selected on the basis of their TNIs. The TNI is used by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Environment (UNCTAD) as a measure of the extent to which firms are global in their operations. It is a simple composite average of foreign assets, sales and employment to total assets, sales and employment. The rationale for choosing firms with the highest TNIs was that the firms selected should be the least likely case to test the hypothesis that firms’ home states matter – i.e., that national institutional contexts predominate over global interests.14

The firms chosen produce a variety of reports. Some are more focused on environmental sustainability, while others include environmental initiatives within their broader corporate social responsibility/citizenship reporting. For the latter, sections outlining environmental responsibility were the focus. Three sections of the reports were analysed. First, executive statements presenting the view of the CEO and other board members that appear at the front of reports were examined because these ‘set the scene’ of the report by presenting the view of its contents by the highest office holder/s. Secondly, environmental ‘vision statements’ were examined. These relate to a section/s presenting the firm’s vision with respect to environmental performance. Thirdly, actual

109policy guidelines were examined, if included in the reports, or a web link provided for the reader. These sections implement the company’s vision by setting in concise form for its employees clear rules for action on environmental issues. Although these three sections account for a small proportion of the reports – and there was considerable variation in the level of detail firms presented – the aim of focusing on these sections was that they permit a comparative analysis on an as-near-as-equal basis between what are otherwise often stylistically dissimilar reports. While the variations are acknowledged, these sections are where rationales for action are found, rather than descriptions of the action undertaken. They present why the firm is taking environmental action, and what environmental responsibility means to it, as opposed to just a report of actions taken.

Statements in these sections were coded for the material factors of market forces and state regulation, and for the normative factors of social concerns and internal company beliefs. Sub-categories within these were also identified and coded. Detailed definitions of the categories and sub-categories, as well as the actual process of coding statements in these sections, are provided in the ‘Methodological Appendix’. The percentage of codes on material versus normative factors is considered first, followed by a quantitative and qualitative analysis of coding for the sub-categories below these. The analysis aims to highlight the actual proportional differences in codes between firms (i.e. relative emphasis), as well as the qualitative nature of the statements codes represent (i.e. motivations ascribed).

A complete list of the firms chosen is shown in Table 4.1, along with the proportion of sales, assets and employment outside their home state.15 What is immediately apparent is something that has been noted by other commentators: even for the most global of firms their TNI is, on average, not very high (see Dicken 1998, 2003; Rugman 2005; and, for a general overview of the arguments, Hay 2006c). The TNI of the top five firms from each state is no higher than around 70 per cent, with the majority in the range of 46–60 per cent. There are other factors that

110undermine the assertion that firms such as these are increasingly transnational in their operations, such as the extent to which firms are bi-national rather than transnational, or regional rather than global. These issues are not investigated here. It suffices to say that even a cursory glance at the data demonstrates that the most global MNCs are not as global as one might think.

Table 4.1 The Transnationality of the selected MNCs, 2004

| TNI (%) | Foreign assets as a proportion of total assets (%) | Foreign sales as a proportion of total sales (%) | Foreign employment as a proportion of total employment (%) | |

| Germany | ||||

| 1. BMW | 67 | 61 | 73 | 67 |

| 2. Bertelsmann | 63 | 56 | 70 | 64 |

| 3. Siemens | 62 | 61 | 63 | 62 |

| 4. Volkswagen | 56 | 49 | 72 | 48 |

| 5. BASF | 54 | 60 | 59 | 43 |

| Japan | ||||

| 1. Honda Motor | 69 | 73 | 77 | 56 |

| 2. Nissan Motor | 61 | 52 | 70 | 61 |

| 3. Sony Corp. | 57 | 41 | 70 | 60 |

| 4. Toyota Motor | 49 | 53 | 60 | 36 |

| 5. Mitsui and Co. | 46 | 49 | 43 | 45 |

| US | ||||

| 1. Coca Cola | 71 | 61 | 69 | 81 |

| 2. McDonald’s | 66 | 74 | 66 | 57 |

| 3. ExxonMobil | 63 | 69 | 70 | 50 |

| 4. Hewlett–Packard | 62 | 60 | 63 | 62 |

| 5.Procter & Gamble | 57 | 59 | 55 | 57 |

Source: UNCTAD 2006, World Investment Report 2006, United Nations, New York & Geneva.

111What is also noticeable is that for twelve of the firms, the proportion of foreign sales in total sales is the same or higher than their TNI. By contrast, the proportion of foreign assets in total assets is the same or lower for eight of them, and the proportion of foreign employment in total employment is the same or lower for twelve of them. Therefore, it is mostly sales, rather than the location of their assets or employment, that is the driver of their transnationality. Although adherents to the liberal economic view will say that sales are surely the most predominant of material interests for firms and that this will be their primary motivator, we shall see this is not the case.

Material versus normative factors

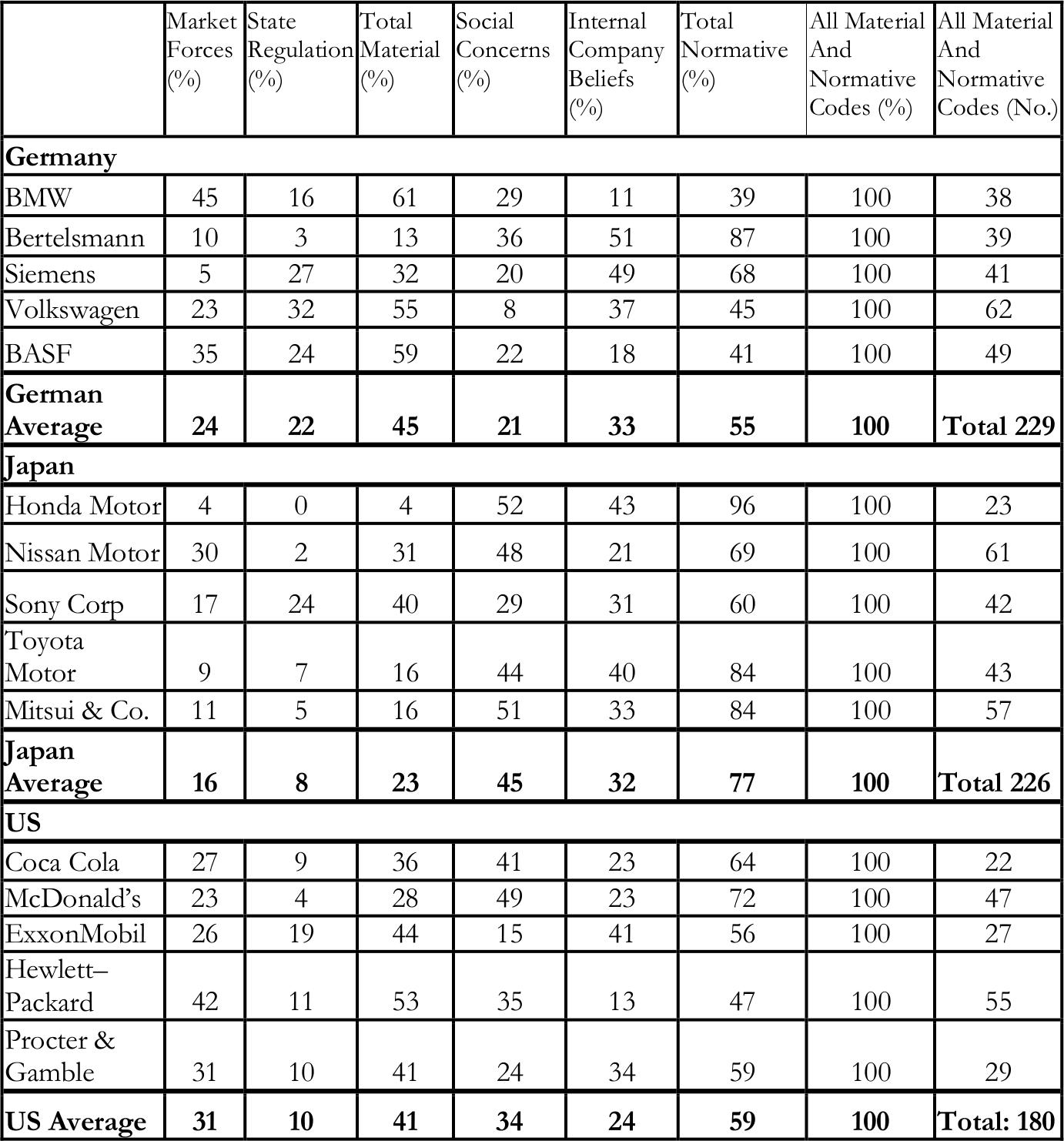

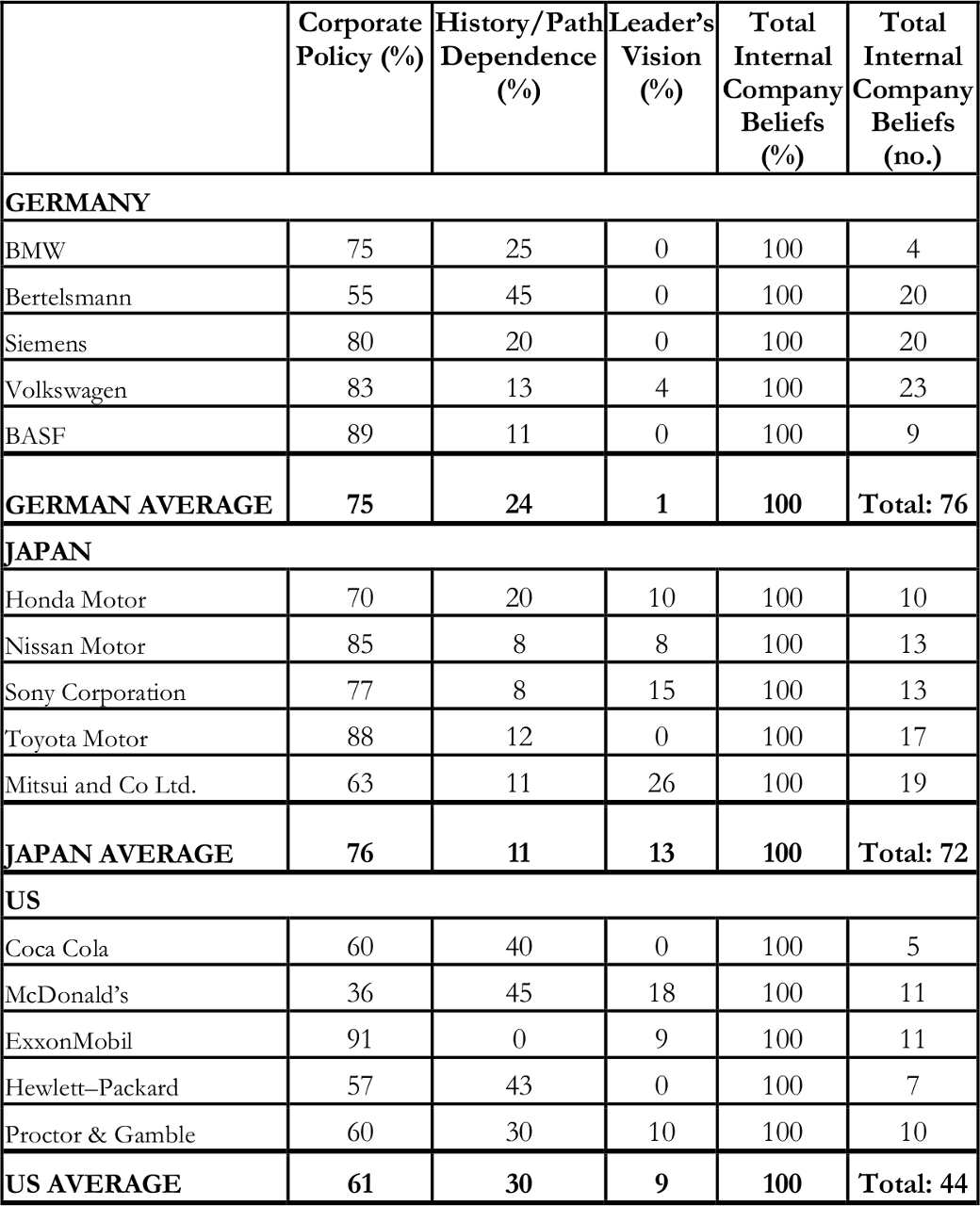

Table 4.2 summarises the results of coding the environmental reports. In proportional terms there is considerable variation in the coding results, although on average it is notable that more normative rationales for action were coded regardless of firms’ nationality.16 However, for the Japanese firms there is the clearest bias towards normative factors. On average, 77 per cent of Japanese firms’ codes are for normative factors, and Honda scores highest of all firms with 96 per cent of codes on normative factors.

The reason normative factors are important for the Japanese firms is mostly fairly evenly split between social concerns and internal company beliefs, but social concerns are more important to them than the German or US firms. Although there is considerable variation in the results for German and US firms, on average 45 per cent of codes applied to the Japanese firms’ reports relate to social concerns, versus just 21 per cent of codes for the German firms and 34 per cent for the US firms. 112

Table 4.2 Coding of Material versus Normative Factors

Source: Company Reports

In terms of material factors, the US firms have proportionally the most codes for market forces. On average, 31 per cent of codes applied to their reports relate to these, by comparison with 24 and 16 per cent for 113the German and Japanese firms respectively. Although there is considerable variation in the results for German and Japanese firms (from less than 10% to 45%), US firms are most consistent in having codes applied on market forces (23% to 42%). The German firms have a higher proportion of codes for state regulation than do the US and Japanese firms. On average, 22 per cent of the codes applied to German firms’ reports relate to state regulation, as opposed to 8 and 10 per cent for the Japanese and US firms, respectively.

There are firms that are exceptions. When they are excluded the national trends are more pronounced. For example, the coding on BMW’s report makes it look more like a US firm. Forty-five per cent of its codes are for market forces and only 16 per cent for state regulation. If it is excluded from the German average, German firms appear even more focused on state regulations than do Japanese or US firms. Similarly, Bertelsmann has far fewer codes on material factors than its German counterparts and Sony has noticeably more codes for state regulation than do the other Japanese firms. Exceptions such as these, and the subnational variations in the results generally, are worth bearing in mind. They probably reflect the small sample size.

Despite the variations in the results, one can say that, although normative factors are not unimportant for US firms, it is nevertheless clear that US firms are the most concerned with the material factor of market forces. This relates to LME firms’ preference for market coordination of economic activity. The German firms are most concerned with state regulation. The Japanese firms are most concerned with normative factors overall, plus they have the highest proportion of codes for social concerns. This reflects a CME preference for a more coordinated state–business approach to firm strategies in the case of Germany, and a broader perspective of firms’ interests beyond short-term material returns based on market forces in the case of Japan.

Unpacking these overall proportional averages is the purpose of Tables 4.3 to 4.6 which present the results of coding in the sub-categories within market forces, state regulation, social concerns and internal company beliefs. 114

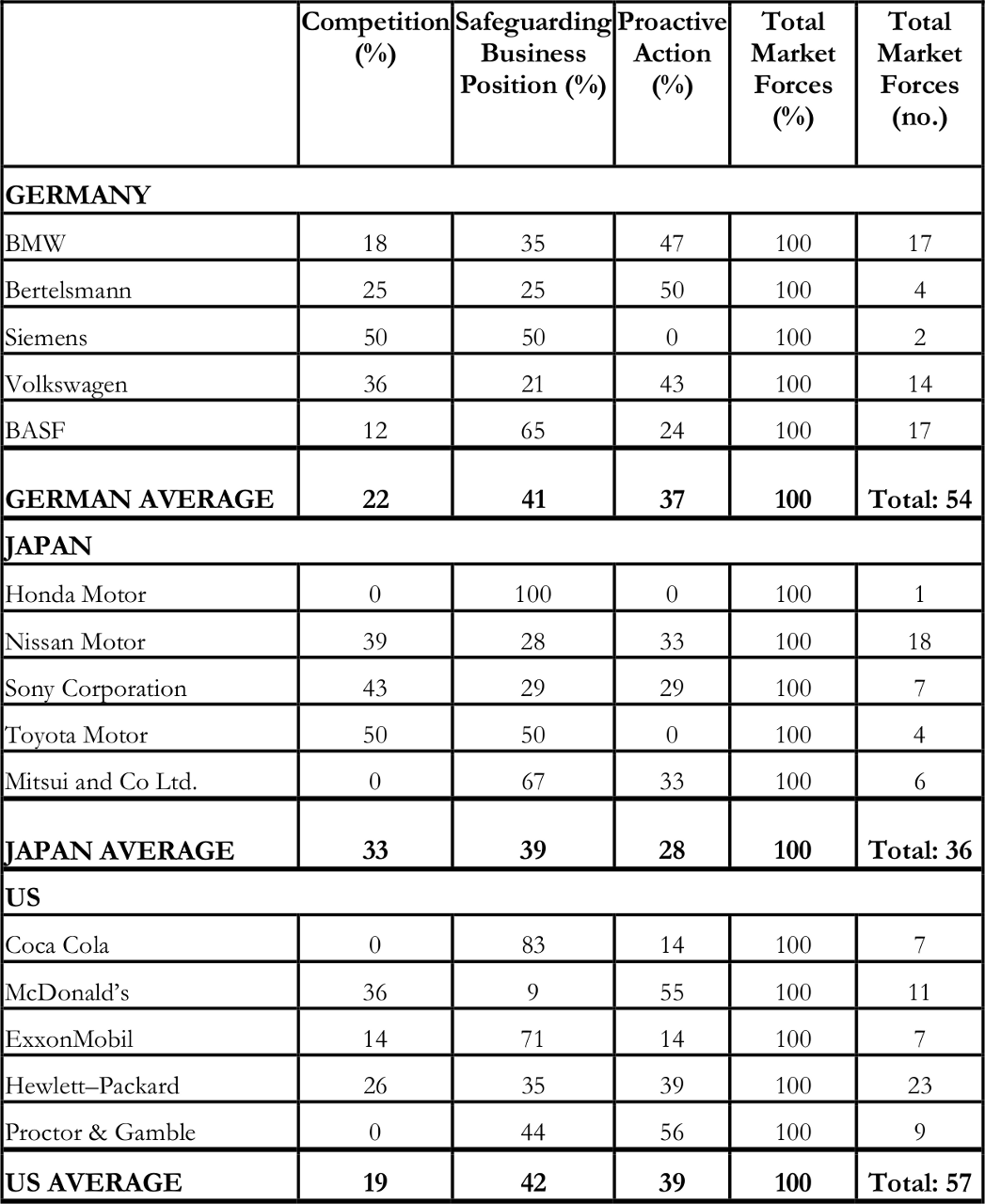

Material factors – market forces in detail

Turning first to market forces (Table 4.3), there are few clear national patterns in evidence. Individual firms’ preferences predominate on whether market forces are important in terms of responding to competitive pressures, safeguarding financial returns or proactively embracing opportunities. It is perhaps interesting to note that, excepting Siemens and Toyota, when firms make statements about market forces they are not overwhelmingly driven by competitive pressures from consumers and other firms, as standard liberal economic renderings of firms’ motivations assert. Beyond this, it is not possible to add to the overall observation that the US firms make proportionally more statements relating to market forces than do the German and Japanese firms.

There are also few discernable qualitative differences between the statements made by firms regarding competition and safeguarding or enhancing their business position. Regardless of their nationality, firms mention factors such as satisfying consumers, remaining competitive, ensuring they continue to grow, and that this will either drive or constrain their efforts with respect to environmental responsibility. But distinct national qualitative differences are discernable for proactive action. German and US firms are clearly more materialist, with statements about seizing opportunities to ensure they remain competitive, often couched in terms of market leadership, and an overarching belief that there is a link between environmental responsibility and economic success. For example, Coca Cola says that benefiting the environment is worthwhile because “it makes good business sense”, as does Hewlett-Packard when it says “good citizenship is good business”. Similarly, BMW undertakes environmental initiatives because “sustainable actions provide the basis for viable development”. However, the language used by two of the Japanese firms, Mitsui and Nissan, is less materialist. Mitsui talks of improving the firm’s corporate value via “engaging in conscientious activities giving full consideration to the social significance of [its] presence and a strong awareness of [its] ties with the environment”. Nissan declares: “we have to create sustainable value by enriching people’s lives”. Indeed, Nissan says that its social and environmental responsibilities are “very deeply tied to [its] 115business itself”. Therefore, the imperatives of market forces are seen in more normative than material terms for the Japanese companies.

Overall, regardless of the sub-category, market forces are most important for the US firms: their environmental initiatives are driven or constrained by market forces. This is consistent with the importance of market forces in the US LME variety of capitalism, as opposed to one factor among many, and more an underlying than primary concern in CMEs. However, it is interesting to note that German firms’ statements are similar. By contrast, two of the Japanese firms express their aspirations and identification of business opportunities in language that implies something more than market success and winning a competitive battle. In CME-style, broader strategic goals are the aim in which they identify environmental responsibility as being at the heart of their conceptualisation of what their business and its success are all about. They exhibit a more relational, societal basis to achieving their material goals.

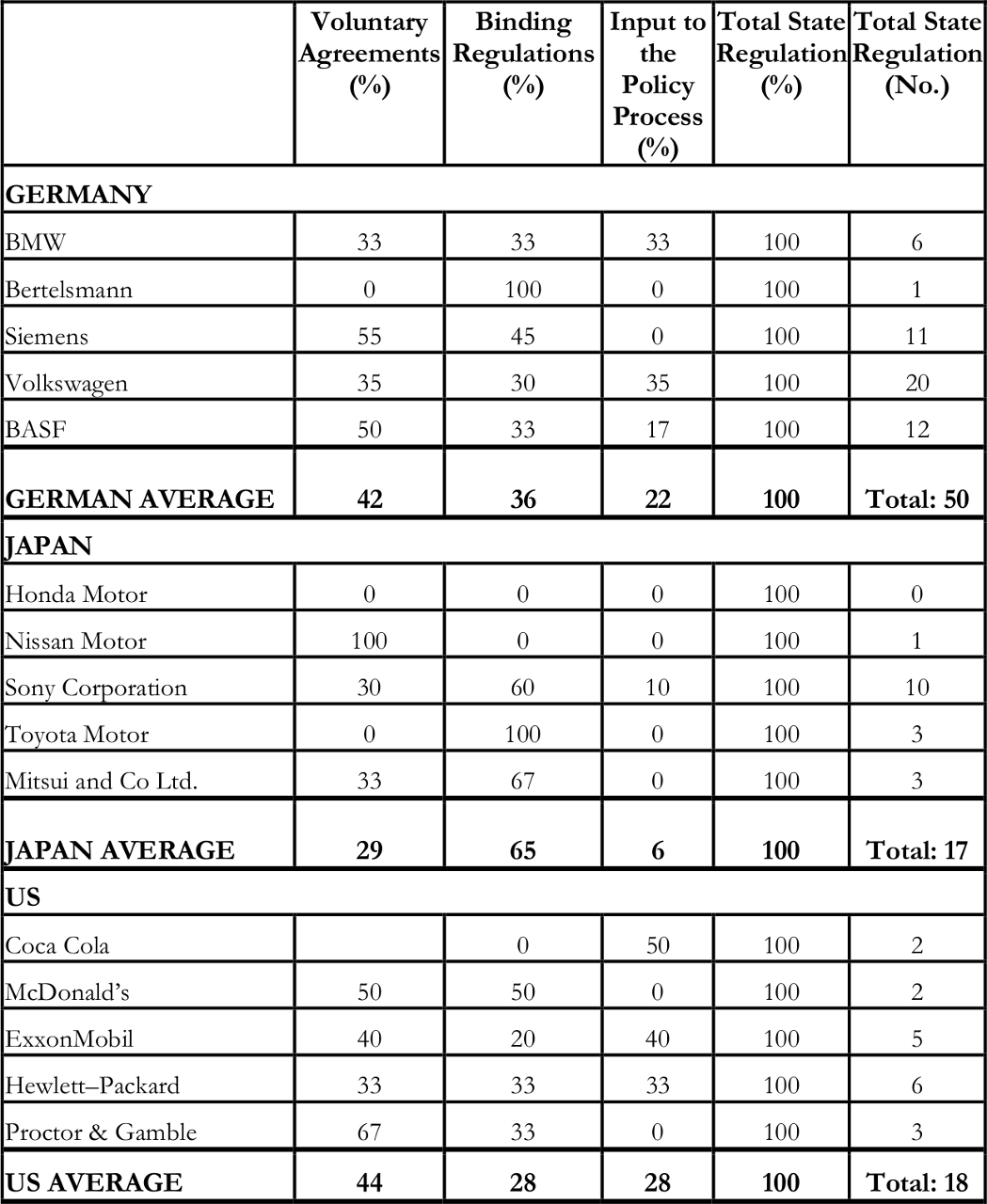

Material factors – state regulation in detail

Turning to state regulation (Table 4.4), a range of national and international agreements and regulations are mentioned by all the firms. The US and German firms (with the exception of Bertelsmann) have a greater proportion of their codes on voluntary agreements than do the Japanese firms (with the exception of Nissan). But there is considerable sub-national variation in the proportional coding for binding regulations. For example, one could say that when they do make statements about binding regulations, Japanese firms do so more often than firms of other nationalities. But it could equally be said that two of the Japanese firms make no statements regarding binding regulations at all. 116

Table 4.3 Material factors – market forces in detail

Source: Company reports. 117

Table 4.4 Material factors – state regulation in detail

Source: Company reports.

The clearest national differences are evident in the qualitative nature of the statements made. There is a clear difference between the US and Japanese firms versus the German ones. The US and Japanese firms primarily highlight compliance with regulations, although Procter and 118Gamble refers to the “letter and spirit of the law”, and Toyota to the “language and spirit of the law”. Thus, these two firms to some extent go beyond statements about simple compliance. However, all the German firms do this. BASF and BMW state that they support the goals, as well as the targets of the Kyoto Protocol, Bertelsmann talks of the “spirit and letter of the law”, Siemens repeatedly refers to going “above and beyond statutory requirements”, and Volkswagen states that it respects the law and exceeds what is legally prescribed. Therefore, while all the firms say they comply with regulations, the German firms appear to have the most affinity for regulations and aim to exceed regulatory requirements.

The US and German firms are most likely to make statements on input to the policy process. Of the Japanese firms, only Sony mentions providing such input, and makes one reference to so doing. Clearly, this is not a priority for the Japanese firms, as they do not choose to highlight it in their reports. However, there is a qualitative difference in how the US and German firms discuss policy input. The US firms stress their cooperation with government and related organisations to find solutions, performing an “active and constructive role” (ExxonMobil), or “helping to shape a broad array of policies” (Hewlett–Packard). Coca Cola stresses that it cooperates in order to “address global environmental challenges”. The German firms make similar statements, but they additionally highlight their role in proactively suggesting policy solutions. For example, BASF says it “actively contributed to alternative proposals” on regulations. Volkswagen sees itself as entering the “public debate”, and working “hand-in-hand … to shape a socially and ecologically sustainable development process” because it is “both legitimate and necessary to present [its] expert knowledge to politicians and authorities and contribute [its] experience to help shape socially responsible background conditions”. Therefore, while both the German and US highlight a constructive and cooperative approach, the German firms more clearly highlight the manner in which they proactively suggest regulatory solutions to environmental issues.

Overall, the following findings are evident on state regulation. As well as coding proportionally more for state regulation than the US and Japanese firms, the German firms share a preference with the US firms 119for a more voluntaristic approach to state regulation. In addition to preferring a voluntaristic approach, the German firms also stress exceeding regulatory requirements and providing input to government on regulations to drive the policy development process. In a qualitative sense, they do so more strongly than do the US firms. These observations fit with a more CME-style of regulation setting and implementation: a voluntaristic approach based on extensive state–firm discussion and consensus building, in the context of a belief that private firms have public responsibilities to fulfil above and beyond regulatory requirements.

By contrast, the LME-based US firms are supportive, but less ‘enamoured’ of regulations. Although the US firms seek to provide input to the policy process, this is less out of a desire to proactively shape regulations, than a matter of ensuring they have a say in the outcome of them. The distinction is subtle, but their statements suggest that the purpose of their involvement is to ensure that their material interests are not infringed, rather than reflect a commitment to developing regulations that successfully address environmental issues. Indeed, ExxonMobil’s desire for involvement is that it wants to help shape “our energy future” – that is, the material interests of the company. Viewed in this light, the US firms’ preference for voluntary agreements is related to an LME desire for minimal formal regulation. The Japanese firms stress compliance with regulations more than anything else, but sub-national variations in their coding proportions make clear conclusions problematic. However, they do make the weakest statements with respect to regulations. As with the coding of statements made by German firms for market forces, this is somewhat at odds with what the VOC approach suggests.

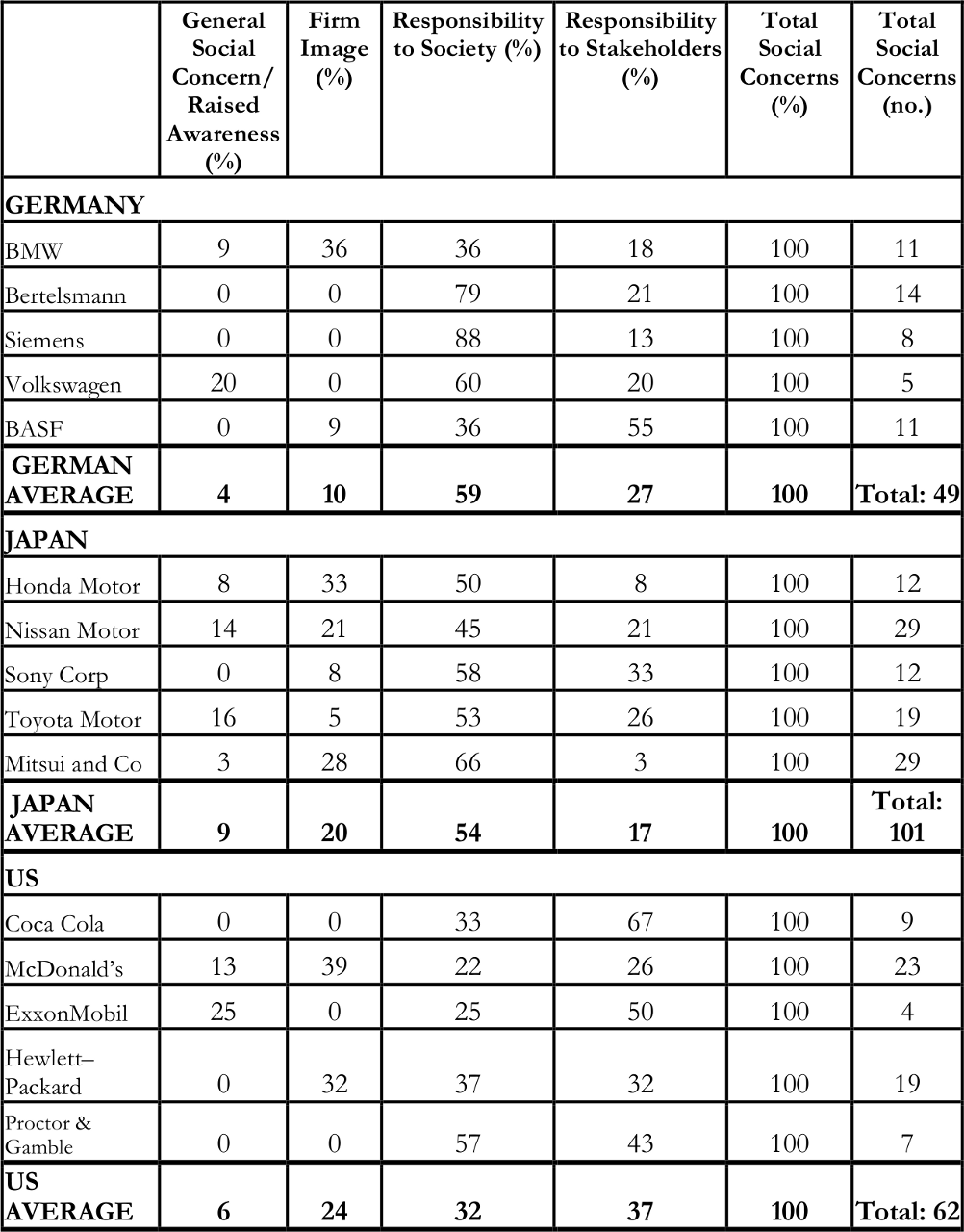

Normative Factors – Social Concerns in Detail

For social concerns (Table 4.5), it is interesting to note that none of the firms, regardless of their nationality, strongly cite responding to general social concern/ raised awareness of environmental issues. On average, less than 10 per cent of codes are on this aspect of social concern. Even so, despite there being a small number of statements, there are national qualitative differences in the statements made. The two US firms that make statements regarding social concerns relate these to material 120factors, i.e. they view social concern through a materialist ‘lens’. McDonald’s expresses a hope that firms’ socially responsible endeavours “will come to have more influence on consumers’ purchasing habits”, while ExxonMobil sees social concern for the environment in terms of causing “the public greater concern about the supply and cost of energy”. The German and Japanese firms do not draw such a clear materialist link in their rendering of social concerns. The two German firms that make statements in this regard note that there are always social concerns that must be faced, and not just for their impact on material outcomes. However, two of the Japanese firms, Nissan and Honda, go further to see increased social awareness of environmental problems as requiring a response in and of itself.17 For example, Nissan notes the emergence of a “passionate critique of modern consumer society” to the extent that social concern for the environment is so heightened that “not since the race to put a man on the moon in the 1960s has a community of engineers faced such a stark challenge”.

The material versus normative perspectives delineating the US firms from the German and Japanese firms is further borne out in the proportions of codes applied for statements regarding responsibility to society versus business stakeholders. German and Japanese express more a belief that they owe a responsibility to society in general (59% and 54% respectively on average), while for US firms the responsibility they highlight is skewed towards stakeholders more directly related to their business (37% for stakeholders, versus 32% for society). These national differences are commensurate with the LME-nature of US firms, in the sense that those associated with the material interests of the business, even indirectly, are referred to more than is the case for CMEbased German and Japanese firms that have a more holistic view of their responsibility to society. Thus, even if the German firms share a materialist predilection for market forces with the US firms, they do not do so for social concerns. For the US firms, greater business relevance for the responsibility they owe to those affected by their actions appears required than is the case for the German and Japanese firms. 121

Table 4.5 Normative Factors – Social Concerns in Detail

Source: Company reports.

122The material versus normative divide is also evident in qualitative terms. While all firms, regardless of nationality, discuss their responsibility to stakeholders, the US firms do so more in terms that this is important to their business interests: creating value for customers, meeting stakeholder expectations, addressing stakeholder concerns that are related to business operations or affect these, etc. For example, McDonalds states that its business depends on serving “the interest of [its] diverse stakeholders”, and Procter and Gamble states that “consumers reward [it] with leadership sales, profit and value creation” when it does the right thing. However, some of the German and Japanese firms go beyond such statements to exhibit a far deeper vision of their stakeholder relationships. They see acting responsibility to stakeholders as valuable in and of itself. For example, Bertelsmann states that “in the view of our shareholders, the possession of property creates an obligation to the community”. The difference is most pronounced for the Japanese firms. Nissan sees its relationship with stakeholders not just in terms of interests, but the creation of “trust”. Sony sees its responsibility to stakeholders as part of its “mission and passion”. Toyota says that stakeholder expectations are not just important for the material interests of the company, but that they go to the question of “the type of company that Toyota is”. As such, Toyota discusses stakeholder responsibility in terms of “harmony” and “respecting societal norms”.

The division between the US versus German and Japanese firms is similarly evident for statements on responsibility to society more generally. This is evident in two respects. First, while all the firms refer to their responsibility to society, three of the German firms and one Japanese firm see themselves as part of society and enmeshed in it, as opposed to the US firms which see themselves as outside society with responsibility to it. Of the US firms, Coca Cola comes close in saying it wishes to be “a responsible global citizen who makes a difference”, and McDonald’s describes itself as “a responsible corporate citizen”, but BASF declares “we are part of society”, Bertelsmann says it is “a social player” and Volkswagen says it is “an active member of civil society”. Honda similarly defines itself as “a responsible member of society”. Therefore, their location with respect to society is different: the German and Japanese firms are more part of it, whereas the US 123firms are responsible to it, and their ‘citizenship’ is more explicitly corporate in nature.

Secondly, while the US firms accept that they bear responsibility to society for their actions, the German and Japanese firms have a more profound conception of their role. Bertelsmann states that “in a market economy a corporation derives its legitimacy by making a valuable contribution to society” and desires to “actively contribute to progress and the continuous evolution of social systems”. Similarly, Siemens hopes to “create a better world”. Such a social ‘mission’ is not highlighted as explicitly by the US firms. The Japanese firms go furthest, making statements that can only be described as messianic. They characterise themselves as on a ‘mission’ to do nothing less than save the world. Mitsui declares it “will contribute to the creation of a future where the dreams of the inhabitants of our irreplaceable Earth can be fulfilled”. Perhaps most tellingly, rather than seeking a balance between business material versus social objectives, Mitsui sees that “profits will naturally follow as long as we do good work – work that is valued by society”,18 and says that it aims “to save the world, to save people”. Mitsui is in good company with the other Japanese firms. Honda wishes to “create a sustainable society”, Sony sees itself as on a “societal mission” where “preserving the natural environment … helps humanity to attain the dream of a healthy and happy life”, and Toyota asserts its “passion” to “contribute to society” and “lead the times” through effort that will “contribute to the realisation of a sustainable society”.

This leaves us with comments regarding firm image. The proportional coding of statements for firm image suggests no clear national differences. There is a wide range of sub-national coding percentages in all cases. However, as one would expect of a concept such as ‘image’, qualitative differences reveal clearer national trends. What is noticeable, yet again, is that image is about material success in markets for the US firms, rather than a more normative vision in the case of the German and Japanese firms. The two US firms that mention aspects of firm image take the attitude that building trust and brand image is part of doing business, and strengthening the firm’s brand. Thus, Hewlett–Packard makes statements that it sees its efforts as promoting value for

124customers, and therefore its efforts are part of its imperative to “pursue customer loyalty, profit, market leadership and growth”. Similarly, McDonald’s sees its initiatives as important because they “could make a difference in a customer’s choice of whether to visit [its] restaurants or not”. The two German firms that had codes applied for firm image also make statements that show they are aware of the potential material benefits of more environmentally enlightened behaviour, but such statements are weaker. For example, BASF sees a good reputation as potentially contributing to “long term success”, and BMW notes that “trust is the basis for (its) success”. However, a good reputation appears to be worthy in and of itself for BMW as well. For example, the firm states that “in terms of sustainability, a company is particularly credible and effective when it takes responsibility for its products throughout their entire life cycle”. Japanese firms, once again, make the most emotive statements. They desire to be seen as social leaders commanding respect and standing in the community for what they do. The sense that they are part of society, already identified above, is once again to the fore. Mitsui makes the following pronouncement: “making it a principle to be fair and humble, we, with sincerity and in good faith, will strive to be worthy of the trust society places in us”. In a similar vein, Honda says it “will work to provide joy and excitement to people so that they will value Honda as a company” because the firm’s mission “is to become a company that people throughout the world will want to exist”. Similarly, Toyota seeks to be seen as a company which “emphasises fairness and good faith, acts with courage and determination, and displays abundant vitality and dignity”. It is fair to say that none of the US or German firms approach the same strongly normative basis with respect to their standing in society that is inherent in the statements made by the Japanese firms.

Coding within the sub-categories of social concerns therefore demonstrates one of the clearest material versus normative divisions in rationales for action between the US firms and the German and Japanese firms. The US firms have an LME focus on the material impact on their business, or those most closely related to it, rather than on society generally. They are also more materially focused in qualitative terms. There should be no mistake that US firms’ statements on their responsibility to society are strong. Their actions have an acknowledged 125effect on it, and this is where their rationale for action lies. There is nothing ‘weak’ about such sentiments. But the German and Japanese firms draw as strong, if not stronger links, and in some cases also bridge the gap between themselves and society. In addition to being environmentally responsible, German firms wish to make the world a better place, while Japanese firms wish to at least transform and preferably save it! Therefore, in addition to coding more strongly in proportional terms for responsibility to society, the German and Japanese firms make stronger qualitative statements than do their US counterparts. They are most likely to see changing social concerns as a cause for action, and they have a more holistic vision of social and stakeholder responsibility beyond their material interests. They are rather more proactive on social attitudes than reactive. This supports the idea that as CME-based firms they can substantially alter their behaviour on the basis of social concerns, not just on the basis of market forces, and may do so regardless of a direct demand from society for such behaviour.

Normative factors - internal company beliefs in detail

Finally, for internal company beliefs (Table 4.6), it is clear that all the firms, regardless of their nationality, cite corporate policies or guidelines. However, the US firms (with the exception of ExxonMobil) make proportionally more statements regarding path dependence (with the exception of Bertelsmann). Therefore, US firms’ internal motivations are more associated with a history of acting in a responsible manner than is the case for German and Japanese firms. Two alternative explanations are possible for this. One is that the German and Japanese firms are more inner-directed on environmental responsibility, because they cite firm-wide guidelines, corporate beliefs and strategies that are not contingent on the ‘stickiness’ of historical trends. Alternatively, it could indicate that corporate policy in respect of the environment is more entrenched in the US firms because of longer-standing commitments. No clear finding is possible. However, it is interesting to note that in all cases leaders’ visions are not so important in setting internal company beliefs. This further supports the thesis of the VOC approach, as the implication is that firms’ motivations are structural rather than a matter of agency, i.e. underlying institutions have greater explanatory weight than the role of individuals in senior positions. 126

Table 4.6 Normative Factors – Internal Company Beliefs in Detail

Source: Company Reports.

Qualitatively, it appears that statements on corporate policy fall into three categories: we do it because it is a good thing to do, or it is the “right thing” (i.e. no explicit reasons offered); we do it because it is good 127for us (i.e. instrumental material reasons); and we do it because of a higher vision or a matter of identity (i.e. a strong statement of belief that goes above and beyond material concerns). Regardless of nationality, when firms make statements indicating they have a corporate policy that underlies their drive for environmental responsibility, they fall into each of these categories. The variations seem to be more firm-specific than a matter of nationality. For example, of the US firms, ExxonMobil simply states that “we firmly believe that the way we achieve results is as important as the results themselves”. This is a statement falling in the first category. Coca Cola links its internal belief in sustainability to its desire for “growth”. This statement falls in the second category. McDonald’s makes statements that fall into the third category when it says that its commitments are a matter of identity: “this is about who we are”.

Therefore, the main observation remains that in quantitative terms, German and Japanese firms have proportionally more statements on average coded for internal company beliefs than do US firms. The more internally-driven nature of firm strategies under Japanese and German CME capitalism, as opposed to US LME capitalism, is exhibited. In all cases, leaders’ visions are less important, further supporting the VOC thesis in the sense that what is being observed are structural forces with an institutional basis rather than the agency of individuals. National qualitative differences are harder to discern. As a result, it could be concluded that national differences are not as strong as in other areas. But this author would contend that another conclusion is possible. This is because statements given with respect to market forces, state regulation and social concerns should be more the focus for identifying rationales, and national differences in them. Citing internal company beliefs indicates something else: the extent to which such rationales have been internalised by the companies. Therefore, for example, if one combines the national quantitative variations in coding for internal company beliefs with those for social concerns, the findings in regard to material versus normative rationales for action are further |strengthened. That is, German and Japanese firms are not only more normatively/holistically driven with respect to their conception of their social responsibilities; they have internalised this drive to a greater 128extent as a matter of corporate policy, and are doing so regardless of historical factors.

Conclusion

Two caveats are warranted before drawing conclusions. First, in many respects, this chapter represents a pilot study. The statistical significance of the results is open to question as only a handful of firms is considered. There is a need to extend the study, not just in terms of coverage, but also to see how firms’ motivations evolve over time. Secondly, in addition to the small number of observations, there are also considerable sub-national variations in the results that made it difficult to draw clear conclusions at times (e.g. with respect to the Japanese firms’ statements on state regulation). So, to some extent national similarities and points of difference have been emphasised over these sub-national variations. However, this is necessary in any comparative analysis. One wishes to tease out the similarities and differences within and between groups/categories, whether in terms of absolutes or degree, and the resulting implications.19 Despite these caveats, there are clear findings that reflect and support the insights of the VOC approach.

For anyone accustomed to applying an LME ‘lens’, the US firms’ rationales for action seem most ‘rational’ and ‘believable’. The rationales they present for environmental responsibility are couched more in material terms, particularly what the market dictates. The preference for market modes of economic coordination in LMEs is thus clearly evident in the statements they make. In adhering to regulations, they prefer voluntary to imposed regulation. They meet rather than exceed government regulations, and the purpose of being involved in the policy process is not so much to proactively address environmental issues, as to simply be involved per se. This reflects a preference for arms-length government involvement in markets in LMEs. Normative factors, such as social concerns, are also dealt with significantly for how they impact on, or relate to, material interests. Although social concerns are important to the US firms, these are seen more in terms of how they affect material outcomes, and the interests of stakeholders predominate

129(i.e. those with an interest in, and who are directly affected by, firms’ material interests). Again, the LME model, based as it is on market modes of economic coordination (including a concern for concepts such as shareholder value and profits in the shorter term) supports such a perspective. In LME fashion, internal company beliefs appear less important than for the CME-based firms.

In true CME fashion, non-market modes of coordinating economic activity prevail for the Japanese firms. They emphasise normative factors over material considerations. They stress the importance of social concerns/attitudes as strategic motivators. Even on material factors, normative considerations come into play. Responsibility to society generally predominates as their rationale for action. Material interests flow from these (i.e. they are dependent on them), rather than material interests dominating strategic thinking. The German firms share their Japanese counterparts’ focus on society and social responsibility, and this balances their material motivations with respect to market forces. They like regulation, not just complying with regulatory requirements, but exceeding them. They work in partnership with government to proactively develop regulations that address environmental concerns. Like the Japanese firms, a CME predisposition is indicated for non-market modes of coordinating economic activity. This is true in terms of social attitudes, but even more so in terms of a desire for a partnership approach with regulators.

Not only does the analysis support the insights of the VOC approach, but given that the MNCs whose reports were analysed have the highest TNIs, it is clear that national institutional variations permeate the reporting of these most global firms, and therefore the motivations they cite for action with respect to environmental responsibility. They remain institutionally embedded in the home states where they have their headquarters and strategic decisions are made. Indeed, this is regardless of how they see themselves. For example, Nissan sees itself as a “global corporation” and Procter and Gamble states it is a “global company”. By contrast Volkswagen describes itself as “a global player with German roots” and Mitsui declares that “with companies like Mitsui that are engaged in business around the world, the emphasis of CSR differs depending on the region”. Whichever way they perceive themselves, the 130unavoidable conclusion is that in many ways they remain, at their core, national companies with global interests. Therefore, although ensuring firms make credible environmental commitments is an important consideration, and that these commitments effectively address environmental problems, the question of nationally conducive paths to so doing is no less important.

The findings undermine the mainstream liberal economic perspective on economic actors’ motivations that any concern for the environment must be the result of materially-driven instrumental ‘calculus’.20 As such, if firms are to take environmental concerns into account, it must be because it is in their interest to do so, with this interest defined in instrumental materialist terms. Although such a clear causal path is intuitively appealing and logically plausible, it has clear limitations. Constructing economic actors in this manner is overly simplistic because it suffers from what Katzenstein terms “vulgar rationalism” as it “infers the motives of actors from behaviourally revealed preferences” (Katzenstein 1996, p. 27). Instead, a deeper understanding of firms’ motivations is to be found in highlighting the importance of the institutional lenses through which firms perceive their material interests. Of course, it is not that material interests are irrelevant. It is simply that they may not be the issue. What is instead at issue is whether MNCs perceive their interests in more material or normative terms. Of course, in either case their interests are ‘material’ in the sense that they matter to firms, or are perceived by them as being important in how they convey their motivations. This is confusing and takes us potentially down another path covered by authors such as Hay (2006a, 2006b). It raises many questions of ontology and epistemology, covered rather well, again by Hay (2006d). In this chapter, the focus of the empirical analysis was instead simplified (hopefully not overly) to whether MNCs ascribe their motivations more to material versus normative factors.

It is also important to stress that there are no absolutes. Environmental issues are complex, firms are complex organisations, and the intersection

131of various factors and the forces they exert on firm strategies are not straightforward. Therefore, the conclusions reached need to be qualified by acknowledging that US firms are obviously concerned about their social responsibility, as are German and Japanese firms about making profits. The results of the analysis demonstrate this too (e.g. even if proportionally fewer of the codes applied to the Japanese firms’ reports relate to market forces than is the case for the US firms, there are still statements about market forces in their reports). There is also a complex mixture of national and specific firm traits bound up in these conclusions. Even so, there are clear points of national difference in emphasis between the firms considered. The US firms have a materialist predilection for reacting to market forces. Social attitudes are therefore unlikely to strongly influence their strategic thinking unless these translate into market outcomes. This is reflected in their viewing their responsibility to society primarily in business stakeholder terms. By contrast, German and, especially Japanese firms are more normatively driven via a belief that they bear a responsibility to society more generally. German firms regard regulations as not being imposed on them, so much as an important factor in their business strategies that they are proactively involved in setting to address their environmental responsibilities.

Implications for strategies to address environmental impacts emerge on the basis that these should reflect national institutional preferences. Markets and state regulations drive and constrain US firms. It would therefore probably be best if social groups focus their attentions on changing consumer preferences or lobbying government. However, close stakeholder consultation and cooperation for German firms in partnership with government is most appropriate. In the case of Japan, social concerns exert a strong influence, and a strategy that challenges firms to address the environmental impact of their actions via internally-driven corporate policies on the basis of these will work best. Thus, a one-size-fits-all approach to regulation on the basis that business is ‘global’ misses the point that, even for the most global MNCs, the institutional importance of their home states’ VOC remains predominant in how they perceive their interests and what motivates them to make environmentally responsible commitments.

132This finding therefore suggests that ‘global’ codes of conduct are problematic. Where they are proposed, they potentially represent an attempt to homogenise rules for markets in a manner that reflects, and supports, certain national institutional perspectives over others. Advocacy of global codes begs the question: whose codes? Based on which version of capitalism? It should be seen for what it represents: a political act that seeks to promote and internationally project one institutional version of capitalism rather than another, rather than a response to the inevitable economic imperatives of global markets. Alternatively, even if the codes themselves do not do this, the mechanisms through which they are put into effect and enforced should vary according to VOC variations. There is certainly an LME/CME divide for the firms examined here, and there are subdivisions within this divide (e.g. German firms’ coordination via state–business cooperation on regulation versus Japanese firms’ concern for their place in society). These variations impact on the motivations of firms themselves.

Methodological Appendix

Coding was applied for statements made by firms of rationales for action relating to material and normative factors. First, coding was applied to statements pertaining to the two material factors of market forces and state regulation. Coding for market forces was undertaken for statements identifying forces that affect the firm’s financial bottom line and its economic performance as a result of the products it sells. These included:

- Competition

![]() consumer demand – the need to take account of consumer preferences or demand (e.g. tying efforts on the environment to demand for these, or stating that market forces temper what can be done)

consumer demand – the need to take account of consumer preferences or demand (e.g. tying efforts on the environment to demand for these, or stating that market forces temper what can be done)

![]() competitive pressure from other firms – in markets or within the industry as a whole 133

competitive pressure from other firms – in markets or within the industry as a whole 133

- Safeguarding business position

![]() profits and sales – references to maintaining or increasing these generally

profits and sales – references to maintaining or increasing these generally

![]() shareholder value – providing value to shareholders, or stock performance generally

shareholder value – providing value to shareholders, or stock performance generally

![]() risk management – identification of the environmental as a business risk factor that must be addressed

risk management – identification of the environmental as a business risk factor that must be addressed

- Proactive action

![]() market share/leadership – having products on the market, or leading in their development, as a business strategy that drives environmental product development initiatives

market share/leadership – having products on the market, or leading in their development, as a business strategy that drives environmental product development initiatives

![]() grasping business opportunities – environmental responsibility and producing products that reflect this represents a business opportunity

grasping business opportunities – environmental responsibility and producing products that reflect this represents a business opportunity

State regulation relates to references to national and international voluntary agreements, as well as binding regulations, plus input to the policy process in the development of regulations. Therefore, coding was applied to statements in the following sub-categories:

- Voluntary agreements

![]() national voluntary agreements made and supported jointly between the industry and regulatory authorities

national voluntary agreements made and supported jointly between the industry and regulatory authorities

![]() international voluntary agreements (e.g. CERES and the GRI)

international voluntary agreements (e.g. CERES and the GRI)

- Binding regulations

![]() national regulations required by law

national regulations required by law

![]() international agreements ratified by states (e.g. the Montreal and Kyoto Protocols)

international agreements ratified by states (e.g. the Montreal and Kyoto Protocols)

- Input to the policy process

![]() input to/the provision of advice on national regulations and regulatory settings 134

input to/the provision of advice on national regulations and regulatory settings 134

![]() attendance at/input to meetings convened by international organisations such as the UNEP, or participation in international forums where environmental performance is addressed including meetings held by industry groups such as the WBCSD

attendance at/input to meetings convened by international organisations such as the UNEP, or participation in international forums where environmental performance is addressed including meetings held by industry groups such as the WBCSD

Secondly, coding was applied for the normative factors of social concerns and internal company beliefs. Codes in both these categories relate to normative motivators beyond material factors alone. Social concerns relate to statements highlighting non-market forces to do with social perceptions of environmental concerns. These included:

- General social concern

![]() a recognition of increased social concern/raised awareness with respect to the environment and the need to respond to this

a recognition of increased social concern/raised awareness with respect to the environment and the need to respond to this

- Firm image

![]() brand value – the value of the name of the company and what it represents, especially in terms of loyalty and price premiums that it can extract for its products

brand value – the value of the name of the company and what it represents, especially in terms of loyalty and price premiums that it can extract for its products

![]() building trust – references to trust, respect and generally high standing in a more general sense than brand value

building trust – references to trust, respect and generally high standing in a more general sense than brand value

- Responsibility to society

![]() a responsibility to society generally, nationally or globally

a responsibility to society generally, nationally or globally

- Responsibility to stakeholders

![]() a responsibility to those directly affected by the company’s operations, including customers, suppliers, employees and the government

a responsibility to those directly affected by the company’s operations, including customers, suppliers, employees and the government

Internal company beliefs relate to statements that demonstrate endogenous factors leading firms to take the environment seriously. These included:

- Corporate Policy 135

![]() a statement that environmental responsibility is a matter of corporate belief, including references to guiding principles, guidelines for operation, and policies that codify or implement company environmental strategies