>meta name="googlebot" content="noindex, nofollow, noarchive" />

3

State of the environment reporting by local government: Australian evidence on compliance and content

Abstract

This chapter explores State of the Environment (SoE) reporting by local governments. SoE reporting is an integral part of local government strategic planning and management processes and, in the state of New South Wales (NSW) in Australia, SoE reporting is mandatory. A study was conducted to analyse the content of 2003 supplementary SoE reports and their compliance with reporting guidelines. A sample of 136 SoE reports was analysed using the NSW Department of Local Government State of the Environment (SoE) Reporting Guidelines as a framework for content analysis. The results revealed significant variability in the SoE reporting practices. This variability was encountered, not only in volume of information reported, but also in the nature of the issues addressed, the indicators employed and in compliance with the guidelines. Further, while SoE reports are intended to provide data integral to the development of strategic management plans and processes, on average across all environmental sectors, only half of the councils surveyed provided information in sufficient specificity to address the environmental issues identified in SoE reports. In conclusion, we argue that councils are experiencing difficulties in implementing the requirements of the Local Government Act in relation to SoE reporting. 71

Introduction

Local and regional communities rely on local government to provide a number of essential services and to manage and protect the natural environment in which they live (DLG, 2000). In line with the increasing global focus on environmental management, the provisions of the New South Wales Local Government Act 1993 (hereinafter referred to as the Act) have sought to integrate environmental issues into the strategic planning and performance of principal activities of NSW councils. The Act introduced pioneering requirements for local governments in NSW to prepare a number of reports to be included with annual reports (part 4, s. 428). These legislative requirements include comparative information on actual and projected performance of principal activities during that year, a State of the Environment (SoE) report, a report on the condition of infrastructure over which the council has responsibility and a report on access and equity activities of the council.1 The intent of these requirements is to provide key information as inputs into strategic planning processes and as a mechanism for the subsequent evaluation of council performance. The reforms introduced by the Act are consistent with the ‘New Public Management’ trend in the public sector worldwide to achieve greater efficiency, quantification of achievements and accountability (Lapsley 1999).

Councils have a critical role at the micro-level in activities as diverse as social development through to environmental management. Examples of local government functions and services include: construction and maintenance of roads, waste collection and management, recreation, protection and conservation of heritage (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous), health, community services, building, planning and development approval (e. g. land development and use which has consequences for water resources, soil degradation, biodiversity and

72climate change), administration, and in some cases water and sewerage (DTRS 2003).

Examining and understanding the planning, management, accountability and reporting processes of local councils is essential. Unlike the corporation, where there is a financial and physical separation between the majority of key stakeholders and the operations of the organisation, a much more immediate financial and geographical relationship exists between the activities of local government and its major stakeholders. This increases the need for transparent planning and management, as well as an extension of traditional notions of accountability, particularly in relation to the natural environment.

This chapter seeks to provide insights into the extent of reporting and the information content of SoE reports prepared by NSW local government through an examination of the compliance of local government authorities with the applicable legislation.

State of the Environment Reporting

In 1999, the NSW Department of Local Government (DLG) issued NSW State of the Environment (SoE) Reporting Guidelines, to assist local governments to satisfy their reporting requirements. These guidelines assert that the local SoE report is primarily a management tool of council and has the potential to influence virtually all of the functions of council, given most of those functions have environmental implications (DLG 1999). Indeed, SoE reports are considered so integral to local government planning and management that they are included as part of the annual report2 and SoE reports must be submitted to the NSW Department of Local Government (DLG).

Furthermore, the Act mandates that councils undertake strategic planning. A council’s management plan is the strategic mechanism within which planning, policy making and management may take place. “Councils play a major role in creating the environment within which

73the local and regional community pursue their objectives” (DLG 2000, p. 5), and the SoE report provides critical information for the development and evaluation of strategic planning and council activities.

Despite the prescriptive approach taken by the NSW DLG in issuing comprehensive SoE reporting guidelines and the legislative mandate to report, the current study finds that SoE reporting by NSW local councils is extremely variable. Further, in many cases, SoE reports do not provide information in sufficient specificity to be useful for developing management plans. These results suggest that issues in relation to usefulness, consistency and comparability of SoE reports are important areas requiring further investigation.

This chapter is structured as follows. The next two sections provide background information on the preparation and use of SoE reports, including a review of the extant literature, and outline the significance of the research undertaken in the present study. This is followed by a discussion of the research methods employed to gather and analyse the data. The final two sections present the results of the research, a discussion of the findings, preliminary conclusions and some suggestions for future research.

Economic significance of local government environmental activities

SoE reporting is important both as an accountability mechanism and an input into strategic planning by councils. Local government is a major player in protecting Australia’s environment and in managing its natural resources (ABS 2002). Environmental activities are those that prevent, reduce or eliminate pressures on the environment arising from social and economic activities. They also encompass environmental repair and restoration activities. Australia wide, significant amounts of economic resources are managed and controlled by local government for environmental activities.

74In 2002–03 local government in Australia received over $2.6 billion for environment protection activities3 through state and Commonwealth government contributions, as well as rate revenue which amounted to 13 per cent of total revenue for councils. In 2002–03 current expenditure by local councils on natural resource management activities (including the management, allocation and efficient use of natural resources and recreational management of parks, beaches and reserves) totaled $1.5 billion with natural resource management capital expenditure of $422 million. This amounted to 8 per cent and 9 per cent, respectively of councils’ total current and capital expenditure. State governments contributed $105 million ($29m Commonwealth) to local government for environmental protection activities and $46 million ($11m Commonwealth) for resource management activities. The majority of funding was for waste-water management activities ($70m or 53% of government contributed environment protection funding) and water supply activities ($33m or 58% of natural resource management funding) (ABS 2004).

These figures highlight the economic significance of environmental expenditure at the local government level and the importance of conducting research in this area. Given the magnitude of local government expenditure on the environment, the importance of the SoE report as an accountability mechanism and its central role in local government strategic planning and management, this research investigates compliance of NSW local government SoE reports with the DLG guidelines (described below) and provides insights into the nature, scope and content of such reports based on the analysis of 2003 SoE reports. 75

Literature

New Public Management

The ideas behind New Public Management (NPM)4 focus on removing or minimising differences between the public and private sector and shifting the emphasis to results-driven accountability rather than process accountability (Guthrie, Olsen & Humphrey 1999, Hood 1991). The NPM trend has been characterised by, amongst other things, “the displacement of old-style public administration with a new management focus in public services … [and] quantification as a means of demonstrating achievements (efficiency gains, new levels of performance) and of holding responsible persons accountable” (Lapsley 1999, p. 201).

The emphasis in the use of public sector resources [has] changed from a concern with legalistic conceptions of stewardship to the need to ensure that services [are] provided in the most efficient and effective manner. At the heart of these reforms has been a move away from an obsessive concern with accountability for inputs to a keener focus on outputs and outcomes (Funnell & Cooper 1998, p. 81).

SoE reporting in NSW local government can be seen as embedding these NPM style concepts in mandatory legislative requirements. While no market-based jurisdiction has yet imposed extensive mandatory environmental reporting requirements in annual reporting in the private sector, reporting is required in other forms5 for organisations with significant environmental impacts and accountabilities. In this respect, the inclusion of environmental information as part of the annual reporting regime could be regarded as ‘revolutionary’. In terms of accountability, the guidelines under which the SoE reports are

76produced reinforce the primacy of accountability in terms of results. The framework for reporting, the ‘Pressure-State-Response’ model, as well as recommending the incorporation of comparative information as best practice, support the notion of ‘results driven’ accountabilities for local government.

State of the environment reporting

There is an extensive literature on the preparation of SoE reports, from both international and domestic sources, however, there is little academic research on SoE reporting and little is known about the content and usefulness of these reports for their intended aims. This research aims to address this lacuna.

Much of the existing literature focuses on report preparation and emanates from government agencies, non-government organisations (NGOs) and professional bodies (see for e.g. Boshier 2002; CSIRO 1998; EEA 1999; NETCAB 2000). The focus on report preparation implies that SoE reports are a potentially powerful tool for communicating environmental information to policy-makers and stakeholders. Hence, this literature focuses on the identification, selection and implementation of appropriate reporting indicators and providing guidelines for reporting.

The extant academic literature on SoE reporting is predominantly descriptive. A Canadian study by Campbell and Maclaren (1995) examining municipal SoE reporting in that jurisdiction criticised the lack of common indicators, organising frameworks and data accessibility. It suggested that these factors impede the utility of SoE reporting. These findings were echoed in an Australian study (Lloyd 1996) on early efforts at state and national SoE reporting which called for the strengthening of quantitative measures and the employment of an agreed set of environmental indicators. Another Australian study (Anderson 1997), reviewed the Australian national State of the Environment report. This study outlined both the positive aspects and shortcomings of the report, and provided comprehensive suggestions for improving future reports.

Gibson and Guthrie (1995) conducted a survey examining the quantity of environmental disclosures in annual reports in Australia of both 77public and private sector entities, and concluded that “we are still a long way from any useful common meaningful and systematic reporting practice by organisations” (p. 123). In an attempt to provide meaningful information, the introduction of SoE reporting and associated reporting guidelines for NSW local government could be regarded as a systematic framework to address this issue.

Burritt and Welch (1997) analysed a sample of Commonwealth public sector entities over a ten-year period in an attempt to address the lack of research on environmental disclosures in the public sector. Their exploratory study concluded that disclosure levels increased over the period examined. However, concerns were raised regarding the lack of comparability of information and the “dampening effect of a commercial orientation on environmental disclosures” (p. 15).

Another recent study in the Australian context, Frost and Seamer (2002), analysed NSW public sector entities’ adoption of environmental reporting practices in their annual reporting, finding an association between disclosures and the level of environmental ‘sensitivity’ of the entity’s operations. This paper also called for more research to be conducted on the information content of environmental disclosures and whether such disclosures are used to educate and inform or change/manipulate the reader’s perspective of the environmental performance of the entity.

The studies summarised above focus on the extent and nature of environmental disclosures in the public sector. A number of recent studies (e.g. see Ball 2002, 2004; Marcuccio & Steccolini 2003) have a different focus, namely the exploration of the theoretical motivations for local government (social and) environmental reporting or the lack of it.

From the above review of the literature it is evident that significant gaps exist in contemporary environmental reporting research in the public sector, in particular in relation to the nature of and usefulness of environmental reporting. The present research aims to add to our understanding of environmental reporting in an Australian context. This is particularly relevant as prior research has not examined scope, content and compliance in a mandatory reporting environment. 78

Research Method

Nature and size of sample

SoE reports were collected from the population of NSW local councils. “Councils must produce a comprehensive SoE report every four years, and at least a supplementary report every other year” (DLG 1999, p. 10). Data were collected in 2004 and as such, this study examines 2003 supplementary SoE reports, as the next comprehensive reports were not due to be submitted to the DLG until 30 November 2004 (DLG 2004b).

Table 3.1 Local councils and SoE reports: population and sample information

| Population: | Number |

| 2003 NSW local councils | 174 |

| Number | % of population | |

| Sample of 2003 SoE reports: | ||

| Report accessed and analysed | 136 | 78 |

| Council did not prepare a SoE report | 6 | 4 |

| Council does not prepare a SoE report – council data are included as part of a regional report | 11 | 6 |

| Council sent an incorrect report | 6 | 4 |

| No SoE report received despite repeated requests | 13 | 8 |

| TOTAL | 174 | 100 |

SoE reports are submitted and are accessible from the NSW DLG. However, given that stakeholders are likely to approach the specific council for environmental information, we chose to obtain the reports from each of the local councils to explore the accessibility of these data. Many SoE reports were easily accessed on council websites, however, 79where reports could not be found on websites, councils were contacted by email and/or telephone. The population of local councils in NSW was determined from the Report on the Operation of the Local Government (NOLG 2003). In 2003, there were 174 councils in NSW, however, this number has since declined to 152 following a series of mergers. Of the 174 councils, 157 councils produced a SoE report and we obtained 136 reports (86% of the 157 available reports) as listed in Table 3.1 Reports were collected over the period June to December 2004. Table 3.1 summarises the sample data obtained and provides explanations for the missing information.

Methodology

The SoE reports were analysed employing content analysis. Content analysis involves the systematic analysis of documents through the development and use of coding systems to identify and quantify information in documents (Cozby 1997). This is an appropriate research technique for the current study as it can be used to “objectively and systematically make inferences about intentions, attitudes and values of individuals by identifying specified characteristics in textual message. The unobtrusive nature of content analysis makes it well suited for strategic management research” (Morris 1994 p. 903). The documents were human-coded. Morris (1994) compares human-coded content analysis to computerised coding of the same text communications and her results suggest that the two methods may be equally effective.

To investigate local council compliance with legislative requirements and reporting guidelines, a coding system was developed based on the NSW State of the Environment (SoE) Reporting Guidelines (DLG 1999). SoE reports are expected to address the eight environmental sectors of land, air, water, biodiversity, waste, noise, Aboriginal heritage and non-Aboriginal heritage. Councils are encouraged to provide regional data as necessary and prepare their reports using the Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model (OECD 2003), that is:

![]() Pressure – identification of issues

Pressure – identification of issues

![]() State – reporting on the current status (including the provision of comparative data and community involvement in the collection of data to monitor the environment) 80

State – reporting on the current status (including the provision of comparative data and community involvement in the collection of data to monitor the environment) 80

![]() Response – description of the council’s strategic management plan to respond to the issues identified (DLG 1999).

Response – description of the council’s strategic management plan to respond to the issues identified (DLG 1999).

The sample of NSW SoE reports was analysed by two coders. The researchers developed the classification scheme and trained two coders to complete the data analysis. Training involved the development of a template and detailed explanations for the coding of each of the items in the template. The coders independently classified the data based on the classification scheme. A comparison of the results of their initial analysis revealed some differences and these were resolved by the two researchers by re-examining all of the cases with discrepancies between the coders. It is important to note that a textual analysis employing a classification scheme requires some level of subjective judgement. In some cases, classification discrepancies between the coders were not easily resolved and the researchers worked together to make a final decision in each of these cases.

Research findings

The findings are reported in two broad categories consistent with the research objectives of investigating the compliance and content of SoE reports. The first category explores councils’ compliance with the legislation implemented and their consistency with the DLG guidelines for preparing SoE reports. The second category provides insights into the scope and content of the SoE reports and general observations about reporting practices adopted by local councils.

Compliance issues

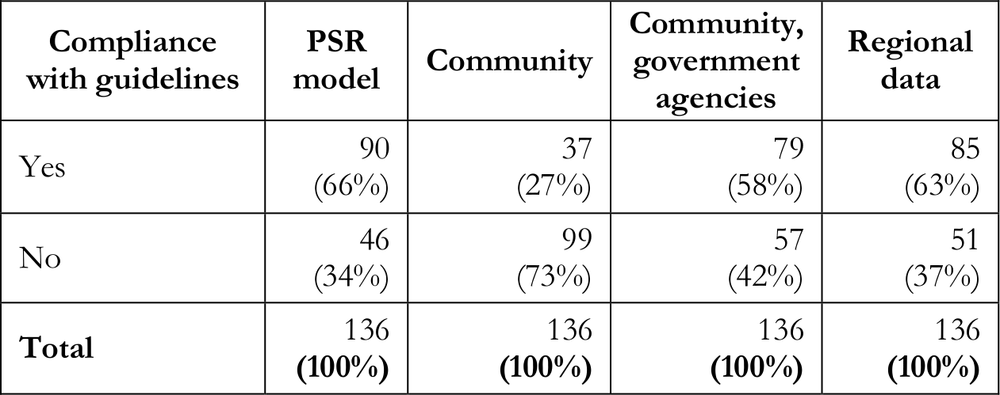

To assist local councils in the application of the legislative requirements and to provide guidance on the preparation and presentation of SoE reports, the NSW DLG produced an extensive document entitled ‘Environmental Guidelines – State of the Environment Reporting by Local Government – Promoting Ecologically Sustainable Development’ (DLG 1999). “The guidelines outline the various steps in preparing an SoE report: assessing the scope and content, identifying the issues, identifying environmental indicators, collecting and managing data, presenting results, submitting the report” (DLG, 1999, p. 3). The guidelines, therefore, provided the framework within which the reports 81were examined. The reports were scrutinised in relation to the preferred model, including the adoption of the Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model, reporting on a regional basis and community involvement in data collection and monitoring. The results are presented in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2 Compliance with SoE reporting guidelines

PSR model

Reporting guidelines recommend that councils adopt the PSR model for their SoE reporting: “For comprehensive SoE reports councils must identify and apply appropriate environmental indicators for each environmental sector, considering and applying the Pressure-State-Response (PSR) model” (DLG 1999, p. 13). SoE reports were examined for their adoption of the model. Of the sample of 136 reports examined, 66 per cent employed the PSR model.

Further, the prescribed PSR model was frequently inconsistently applied, for example: by omitting one of the three PSR elements; by posing elements as questions – for example, ‘what are the issues?’, ‘what is being done?’; and by substituting terms such as ‘indicators’ or ‘assessment’ for the PSR descriptors. In some cases the PSR model was presented in a table to summarise the main issues for each of the eight environmental sectors. These tables were used to report on the current state of the environmental sector and to highlight the key issues. However, in some cases the main PSR elements were only mentioned in these tables, as opposed to within the main body of the report. 82

Community

The Act mandates that “[f]or all SoE reports, councils must: involve the community (including environmental groups) in monitoring changes to the environment over time” (DLG 1999, p. 16). The key purpose of involving the local community is to assist the local government authority in the collection of data for the SoE report. For the purposes of our analysis the term ‘community’ was defined in two ways. First, community was defined as traditional community groups, such as landcare groups and non-government organisations e.g. Greenpeace. Second, it was defined more broadly to include both the traditional groups, as well as government agencies (e.g. Environment Protection Authority and National Parks and Wildlife Service).

Employing a traditional definition of community groups, the results reveal a low proportion of councils (27%) provide evidence of community involvement in data collection and monitoring in SoE reports in at least one of the eight environmental sectors. It appears that for the majority of councils, this directive is not followed. However, taking a broader definition of community to include other government agencies, the results show a higher level of compliance (58%) as evidenced in Table 3.2.

Regional

The guidelines state that “[r]eporting for local SoE reports on a regional rather than an individual council basis is encouraged” (DLG 1999, p. 11) and the sample of SoE reports were analysed for presence of regional data, such as catchment areas, as relevant. Table 3.2 shows that 63 per cent of councils provide regional data. The advantages of reporting on a regional basis include: many issues are regional in nature; cooperation among councils can reduce time and resources in the preparation of reports; and environmental information is often collected on a regional, rather than a council basis by external authorities (DLG 1999).

Scope and content of SoE reports

As well as the reporting guidelines outlining a model for councils to adopt for reporting, the Act also outlines appropriate indicators which councils should report against, essentially defining the environmental 83sectors for which local governments have some responsibility and concomitant accountability.

The Act requires:

[t]he first SoE report of a council for the financial year ending after each election of the councilors must be a comprehensive SoE, which:

Addresses the eight environmental sectors of land, air, water, biodiversity, waste, noise, Aboriginal heritage and non-Aboriginal heritage …

A supplementary SoE report must …

Update the trends in environmental indicators that are important to each environmental sector (DLG 1999, p. 10).

The guidelines also encourage the production of comparative data. The quality and value of environmental indicator data presented in local SoE reports can be enhanced by:

![]() Analysing trends …

Analysing trends …

![]() Placing current levels in context …

Placing current levels in context …

![]() Comparing measured values of the indicator to agreed standards or goals (DLG 1999, p. 19).

Comparing measured values of the indicator to agreed standards or goals (DLG 1999, p. 19).

Further, the SoE report is part of the council’s management planning and annual reporting.

For it to be effective, the management planning and the SoE reporting processes should be linked together in a manner that ensures that the relevant information and proposed directions fed from one into the other … The SoE report should report on the environmental issues identified in the management plan, as well as identifying other issues affecting the area, and may suggest tangible and achievable responses to those issues” (DLG 2000, p. 53).

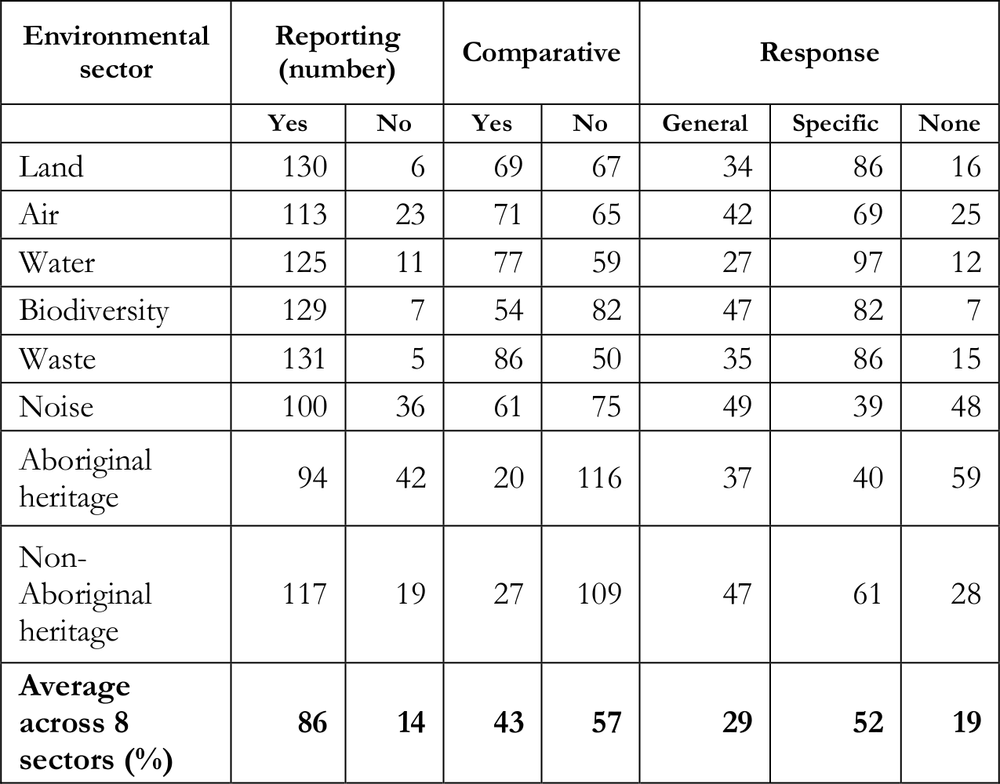

Table 3.3 reports the results of the analysis of the content of the SoE reports based on the guidelines outlined above. Each SoE report was analysed to ascertain whether: councils reported on all eight 84environmental sectors; comparative data were provided; and councils provided a ‘response’ (future actions, aims or objectives) to address the identified environmental issues for that sector.

Table 3.3 Scope and content of SoE reports for the eight environmental sectors. Number of SoE reports

Reporting

In the analysis (coding) employed for this research, reporting was defined as the provision of financial or other information on the current state of the environmental sector. The following statement was considered an example of reporting in the environmental sector ‘land’:

Table 4 summarises the number of DAs received and determined and the number of construction licenses issued 85by Council during 2002/03. (Wollongong City Council 2003, p. 20.

In contrast, the following statement was not considered an example of reporting as it is too general and does not provide data on the current state of the environmental sector:

Noise related complaints normally relate to vehicle noise in urban areas, domestic dogs barking in village areas and noise associated with industry. Noise issues have not been a problem in the shire community over the reporting period. (Severn Shire Council 2003, p. iv)

Discussion of Results

Table 3.3 reveals that on average, across the eight environmental sectors, 86 per cent of SoE reports contain information on the current state of the environment. It is important to note that sectors such as land and waste have many fewer examples of non-reporting than sectors such as noise and Aboriginal heritage. In some cases councils noted that they did not have sufficient resources or the appropriate equipment to monitor the environment or reported data gaps. Illustrative extracts in relation to the environmental sectors ‘air’ and ‘noise’ are provided below:

There is no routine monitoring outside of Canberra … Without a monitoring station in place it is not possible to know if local effects are causing pollutant accumulation. (Mulwaree Shire Council 2003 p. 1).

Transport noise would be the main type of noise pollution … No scientific studies have been undertaken on this issue … (Lockhart Shire Council 2003, p. 24).

The analysis of SoE reports provided clear evidence that councils experience difficulty in determining both what information, and how to measure that information, in discharging their SoE reporting responsibilities. For example, in relation to noise, reporting for most councils consisted of listing the number of noise complaints reported to council, as opposed to recording the output from a measurement device, 86such as a sound level metre. Measurement issues in relation to ‘air’ are echoed by Tumut Council (2003, p. 2) noting it is not clear ‘what’ the measurement unit is.

Air quality can be assessed on broad or fine scales: an entire region, an urban air shed, an individual valley or a room within a building … The careful siting and rigorous operation of measuring devices is essential to monitor air quality. However, this task is complex and needs regular updating. (Tumut Council 2003, p. 2)

In most cases, where councils reported on air quality, limited data was provided (e.g. number of Environmental Protection Authority Pollution Licenses issued) and was not comprehensive.

Comparative data

The SoE guidelines state that the quality and value of environmental indicator data presented in local SoE reports can be enhanced by the provision of comparative data. Comparative data can provide clear evidence of the impact of council activities and programs on the environment, both over time and across councils. For example, in the 2002–2003 SoE update, Hurstville City Council (p. 18) provides comparative figures on domestic waste for the period 1995–2002. The data provides evidence of the effectiveness of the council’s waste management initiatives to reduce waste going to landfill (21,413 tonnes in 1995 down to 16,052 tonnes in 2002). However, on average, across the eight environmental sectors, 43 per cent of councils provided comparative data in their reporting as evidenced in Table 3.3. One council stated: “comparisons to noise complaints from previous years are inconclusive because of recent updating of council’s records management system from manual to electronic records management” (Auburn Council 2002/2003, p. 56). Of the councils which provided comparative data, most provided ‘intra council’ data on the required eight sectors and there were fewer councils that provided comparisons to other councils, benchmarks or best practice figures. Consistent with NPM style reforms, benchmarking against best practice and accountability in terms of results is encouraged by the guidelines. 87

Response

A final area explored was whether councils provided suggested ‘responses’ (or aims or objectives) to environmental issues identified. This was considered relevant, given council management plans draw upon the information presented in the SoE and, under the PSR SoE reporting model, councils are required to provide a suggested response(s) to address issues identified. Responses were classified as: general, specific or none (no response).

A response was classified as ‘specific’, if a response to the issue/area/indicator to be addressed was clearly outlined or a specific action was articulated. Statements in SoE reports illustrating ‘specific’ responses include the following:

Undertake audit of herbicide use to identify if more environmentally friendly alternatives are available as part of the development of an organisation wide procurement policy. (Coffs Harbour City Council 2003, p. 39)

The strategy identifies four key areas where we must achieve outcomes: avoiding and preventing waste; increased use of renewable and recovered materials; reducing toxicity in products and materials; and reducing litter and illegal dumping. The strategy identifies broad targets for each outcome area …” (Cessnock City Council 2003, p. 25)

And, to addressing woodsmoke pollution:

When the new LEP (Local Environment Plan) is adopted council will require dwellings to have at least a 3.5 star rating under the House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS). (Bingarra Shire Council 2003, p. 13).

On the other hand, where a council’s response consisted of broad (motherhood-type) statements, these were classified as ‘general’. An example of a general statement is provided below:

Council and the community must continue to strive towards a reduction in waste to ensure more sustainable levels are reached. (Camden Council 2003, p. 50).

88Table 3.3 reveals that, on average, across all of the environmental sectors, 19 per cent of councils did not provide any response, 29 per cent provided a general ‘motherhood statement’ style responses and 52 per cent provided a specific response which could be integrated into the councils’ management plan. Once again, there is observed variability across the eight environmental sectors with councils providing more specific responses in the sectors of land, air, water, biodiversity and waste and significantly less suggested responses in the sectors of noise, Indigenous heritage and non-Indigenous heritage.

Further observations

NSW council supplementary SoE reports vary significantly. This result is consistent with findings of prior research reviewed earlier in this chapter (see, e.g. Campbell & Maclaren 1995; Lloyd 1996). Whilst the DLG acknowledges the necessity for autonomy of councils in identifying the issues relevant to their area (DLG 1999), the lack of data availability in some cases and overall consistency and comparability between reports needs to be considered. Extremes in length, detail and coverage were apparent, despite the prescriptive guidelines issued by the DLG.

Length

SoE reports varied in length from four pages (e.g. Coolah Shire Council) to several hundred pages (e.g. Great Lakes Shire Council’s report is 228 pages). The 2003 reports are supplementary SoE reports. A supplementary SoE report is only required to update trends in environmental indicators that are important to each environmental sector. However, in the vast majority of cases, the supplementary report could be considered as a ‘comprehensive’ report, given there was no reference to previous comprehensive reports.

Detail

Many SoE reports focused on plans to be prepared or plans already developed, but which are reported elsewhere, rather than identifying specific strategic actions to address problems. Stand-alone plans (such as environmental management plans), as sources of information about council plans or strategy in relation to environmental issues, were 89frequently referred to, but the detail of information relevant to the SoE report was not included.

Many SoE reports also contained significant background information on the local population and the local area including, in many cases, specific sections entitled ‘social’ or ‘cultural’ information. Interestingly, the Act requires a separate social and community plan.

Conclusions and suggestions for future research

The articulated purpose of SoE reporting in local government is twofold. Generation of these reports for internal users is to support planning and decision making processes. For external users these reports are meant to serve as an accountability mechanism to a broad range of stakeholders through the provision of reliable, relevant and comparable environmental information, as well as providing stakeholders with an indication of the environmental policy of council through articulated ‘responses’ to environmental pressures. In NSW, the DLG asserts that the SoE report is a primary management tool and has the potential to influence virtually all of the functions of council (DLG 1999), however our study provides little empirical evidence to support this contention.

This research examined local council compliance with SoE reporting guidelines and related legislation as well as providing insights into the scope and content of 2003 supplementary SoE reports. Considerable variability in local council reporting practices was found by analysing an extensive sample of 136 NSW SoE reports.

In terms of compliance, the results revealed that 66 per cent of councils employed the required Pressure-State-Response (PSR) reporting model; a low proportion of councils (27%) provided evidence of community involvement in data collection and monitoring in SoE reports; and 63 per cent of councils provided regional data. With respect to the scope and content, the analysis revealed that, of the required eight environmental sectors, most of the sectors were treated comprehensively with the exceptions of ‘noise’, ‘non-Aboriginal heritage’ and, in 90particular, ‘Aboriginal heritage’. Additional research is required to investigate the possible reasons for the lack of reporting in these areas.

The most significant finding of this study is that, while SoE reports are intended to provide critical data internally for the development of management plans, on average across all environmental sectors, half the councils (52%) provided tangible and achievable responses to address the issues identified in the SoE report. Further, 43 per cent of councils provided comparative data, which are valuable for identifying trends in the impact of councils’ activities on the environment over time. Given the magnitude of economic resources expended by local government on the local environment, the role of the SoE report as an accountability mechanism and its central role in local government strategic planning and management, further research is needed to better understand how SoE reporting could be improved and effectively integrated into council management planning processes.

Statutory requirements for the preparation of a SoE reports as a preliminary to the compilation of formal management plans, impose significant costs on the local government sector. An interesting question to be investigated is: whether these requirements are merely viewed as another reporting imposition from the state and prepared only as evidence of compliance, or whether they are relevant in strategic planning and management and the evaluation and management of local and regional environment issues. Further research to assess the extent to which these requirements are effective in achieving their intended objectives is critical.

The revolutionary requirements of the NSW Local Government Act for every council to produce extensive environmental information could be regarded as a manifestation of new public management. The guidelines directing the reporting process focus on results driven accountabilities and on the efficient effective provision of public services. However, consistent with prior research, NSW local councils experience difficulties in determining both what to report and how. More work is required for councils to be able to determine appropriate tools and metrics with which to report their environmental responsibilities and activities in ways that enable consistency, comparability and accountability. 91

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the University of Sydney, Faculty of Economics and Business Special Research Grant scheme, as well as the NSW Department of Local Government for their assistance with data collection. The authors would also like to thank James Guthrie, Bob Walker and the participants at the University of Sydney, Discipline of Accounting Seminar Series for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this work.92

References

Auburn Council, 2002/2003. Supplementary state of the environment report, Auburn Council.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2002. Environment expenditure, local government, Australia, 4611.0, ABS, Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2004, Environment expenditure, local government, Australia, 4611.0, ABS, Canberra.

Anderson E, (ed.), 1997. ‘State of the environment 1996’, Australian Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 4, pp. 157–184.

Ball A, 2002. Sustainability accounting in UK local government: an agenda for research, ACCA Research Report, no. 78, London.

Ball A, 2004. ‘A sustainability project for the UK local government sector? Testing the social theory mapping process and locating a frame of reference’, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, vol. 15, pp. 1009–35.

Bingarra Shire Council, Australia, 2003. State of the Environment Report, Bingarra Shire Council.

Boshier J, 2002. ‘Preparing the 2001 state of the environment report’, Australian Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 9, pp. 141–2.

Burritt R L & Welch S, 1997. ‘Australian commonwealth entities: an analysis of their environmental disclosures’, Abacus, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 1–15.

Camden Council, Australia, 2003. State of the environment supplementary report 2002–2003, Camden Council.

Campbell M E & Maclaren V W, 1995. ‘An overview of municipal state of the environment reporting in Canada’, Canadian Journal of Public Health, vol. 86, no. 6, pp. 408–413.

Cessnock City Council, Australia, 2003. State of the environment report 2002–2003, Cessnock City Council.

Coffs Harbour City Council (2003), Coffs Harbour State of the Environment Supplementary Report 2003.

Coolah Shire Council, Australia, 2003. Annual Report 2002/2003, Coolah Shire Council.

Cozby P, 1997. Methods in behavioural research, 6th ed., Mayfield.

CSIRO, 1998. A guidebook to environmental indicators, CSIRO, Australia. 93

Department of Local Government (DLG), 1999. Environmental guidelines – state of the environment reporting by local government – promoting ecologically sustainable development, DLG, Canberra.

Department of Local Government (DLG), 2000. Management planning for NSW local government – guidelines, DLG, Canberra.

Department of Local Government (DLG), 2004a. Strategic tasks 2004–2005, DLG, Canberra.

Department of Local Government (DLG), 2004b. Comparative information on NSW local government councils 2002–2003, DLG, Canberra.

Department of Transport and Regional Services (DTRS), 2003. Local government national report 2002–03 – Report on the operation of local government, DTRS, Canberra.

European Environment Agency (EEA), 1999. State of the environment reporting: institutional and legal arrangements in Europe, European Environment Agency, Copenhagen.

Frost G R & Seamer M, 2002. ‘Adoption of environmental reporting and management practices: an analysis of New South Wales public sector entities’, Financial Accountability & Management, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 103–127.

Funnell W & Cooper K, 1998. Public sector accounting and accountability, UNSW Press Ltd, Sydney.

Great Lakes Council, Australia, 2003. Supplementary state of the environment report 02/03, Great Lakes Council.

Gibson R & Guthrie J, 1995. ‘Recent environmental disclosures in annual reports of Australian public and private sector organisations’, Accounting Forum, vol. 19, no. 2/3, pp. 111–127.

Guthrie J, Olsen O & Humphrey C, 1999. ‘Debating developments in new financial management: the limits of global theorising and some new ways forward’, Financial Accountability & Management, vol. 15, no. 3 & 4, pp. 209–228.

Hood C, 1991. ‘A public management for all seasons?’, Public Administration, vol. 69, pp. 3–19.

Hurstville City Council, Australia (2002-2003) State of the Environment Update.

Lockhart Shire Council, Australia, 2003. State of the environment report, Lockhart Shire Council.

Lapsley I, 1999. ‘Accounting and the new public management: instruments of substantive efficiency or a rationalising modernity?’, 94Financial Accountability & Management, vol. 15, no. 3 & 4, pp. 201–07.

Lloyd B, 1996. ‘State of the environment reporting in Australia: a review’, Australian Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 3, pp. 151–162.

Marcuccio M & Steccolini I, 2003, ‘Social and environmental reporting in local government; a new Italian fashion?’ SDA Bocconi, Working Paper N. 105/03.

Morris R, 1994. ‘Computerised content analysis in management research: a demonstration of advantages and limitations’, Journal of Management, vol. 4, pp. 903–31.

Mulwaree Shire Council, Australia, 2003. State of the environment report, Mulwaree Shire Council.

National Office of Local Government (NOLG), 2003. 2002–2003 Report on the operation of the Local Government (Financial Assistance) Act 1995, NOLG, www.nolg.gov.au/publications

Networking and Capacity Building Programme (NETCAB), 2000. SoE Info, no.4.

NSW Local Government Act (NSW) 1993

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2003. OECD environmental indicators – development, measurement and use, reference paper, OECD.

Severn Shire Council, Australia, 2003. Supplementary state of the environment report, Severn Shire Council.

Tumut Council, Australia, 2003. State of the environment report, Tumut Council.

Wollongong City Council, Australia, 2003. State of the environment report, Wollongong City Council.

1 Infrastructure reports provide information, both financial and non-financial, on the physical condition and costs to repair council infrastructure (e.g. roads and buildings). Access and equity reports provide information, both financial and non-financial, on programs and plans that are aimed at improving services and access for particular groups (e.g. people with disabilities and the aged).

2 SoE reports must be included in the annual report. However, “the SoE report is often submitted as a separate document due to its size or because it has been prepared as a regional SoE report with other councils” (DLG 2004a, p. 117).

3 2002–03 data is reported as it is relevant to the time period of the SoE reports analysed in this chapter. Further, all dollar figures reported are in Australian dollars.

4 The term ‘New Public Management’ encompasses the idea of ‘New Public Financial Management’ which focuses on reforms to financial management and systems and therefore, inevitably, the role of accounting and accountants (Guthrie, Olsen & Humphrey 1999).

5 For example, in Australia, reporting to the relevant Environmental Protection Authority or producing return data for the National Greenhouse Inventory.