>meta name="googlebot" content="noindex, nofollow, noarchive" />

12

Framing the debate: an analysis of the Australian Government’s 2006 nuclear energy campaign

Abstract

Nuclear energy has recently experienced a global renaissance. It is considered by many as one possible way to reduce the human contribution to climate change. Australia, with its lengthy anti-nuclear history, has seen revived debate during the years 2006 and 2007, on whether the country should embrace nuclear power given its vast uranium reserves and the significant greenhouse gas emissions by existing fossil fuel energy sources. This chapter examines the issue of nuclear energy in Australia from a public relations perspective and within a framework of political communication theory. From research conducted in 2006, we argue that, well before announcing a potential PR campaign on nuclear energy in May 2007, the federal government was already conducting such a campaign, with a view to presenting a nuclear energy policy proposal to the Australian electorate.

Introduction

On 30 May 2007, the following exchange took place during question time in the Australian Commonwealth Parliament’s House of Representatives: 394

Mr Rudd: Can the Prime Minister… confirm that the government is now also planning a taxpayer-funded public education campaign to increase community support for an Australian nuclear industry?

Mr Howard: We think that providing information to the Australian public about the energy challenges of this country is important … If it does go ahead, it would be entirely appropriate and defensible.1

A strategic communication campaign on the nuclear issue was, in fact, underway a year before this interchange. In 2006, the Australian Government created and commenced a political public relations campaign around the issue of nuclear energy, with a view to presenting a nuclear energy policy proposal to the Australian electorate. This chapter investigates the public relations strategies used by the federal government during its campaign and is based around the specific timeframe of the Uranium Mining, Processing and Nuclear Energy taskforce. The taskforce was established by Cabinet on 6 June 2006, and released its findings in December 2006, in a report entitled, Uranium mining, processing and nuclear energy – opportunities for Australia?

Nuclear energy is a controversial issue and because of Australia’s lengthy anti-nuclear history, it is a significantly risky policy to pursue. Wherever it has been introduced, from the United States to South Africa, from Argentina to Germany, it has ignited numerous activities calling for its abandonment. Earlier attempts to introduce nuclear energy in Australia have proved unsuccessful and the contentious2 nature of this issue demands particular attention to all aspects of political communication.

This study analyses a representative selection of publicly available government documents and media reports, within a framework of political communication theory. The primary research and analysis was conducted between July and October 2006, with consideration given to some later events.

395Political communication is strategic and campaigning is structured into discrete stages and tactics, which build upon and inform each other. The public phase of this campaign began in May 2006 when the Prime Minister, John Howard, returned home after travelling to Ottawa and Washington announcing plans to investigate both nuclear energy and uranium. During the campaign, Mr Howard continued to assert he was facilitating an open-minded public debate of the issue.

History of nuclear energy

An Australian perspective

Nuclear energy is a multi-faceted issue with historic implications. The issue has become increasingly contentious in a contemporary international environment. This is due to the dichotomous fears of nuclear proliferation and the need for sustainable energy alternatives in the face of the growing awareness of the detrimental effects of global warming. Nuclear energy is not a new concept in Australia. Current investigation into the potential value of nuclear energy has roots in historical debates.

In 1975, amid growing public concern regarding the implications of expanding the nuclear industry in Australia, the federal Labor Government established The Fox Inquiry or Ranger Uranium Inquiry – a public federal investigation into aspects of the nuclear industry. Prior to publication of the results of the inquiry, the Labor Government lost office and was replaced by the Coalition Government led by Malcolm Fraser with the current Prime Minister, John Howard, as Treasurer.3

The Fox Report concluded that placement of stringent regulation and controls were sufficient to override the hazards of uranium mining, milling and the routine operations of nuclear power reactors. In addition, all export recipients of uranium must have ratified the Nuclear

396Non-Proliferation Treaty.4 In 1976, on the basis of the report’s findings, the government gave conditional approval for the Ranger, Olympic Dam/Roxby Downs and Narbarlek uranium mines to proceed. The Labour Party resumed office in 1983 and enacted the Three Named Uranium Mines policy, with a view to the eventual cessation of uranium mining. Thirteen years later, the Coalition won government and discarded the three mines policy.5

The discovery and exploitation of large reserves of domestic fossil fuels in the 20th century6 has enabled Australia to be less pragmatic about the use of nuclear energy than other countries. The damage resulting from the melting of nuclear fuel rods at the Three Mile Island Reactor in 1979 and the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl seven years later cultivated the Australian public’s view that nuclear energy is dirty, dangerous and avoidable. In 1998, the media obtained a leaked proposal by Pangea Resources to establish a nuclear waste facility in Western Australia to store one fifth of global spent fuel and weapons. The proposal was publicly condemned and abandoned.7

Contemporary developments

Turmoil in the Middle East, the rapidly expanding and energy ravenous economies of China and India and the robust scientific evidence of carbon’s significant contribution to global warming have intensified Australia’s concerns and opportunities regarding energy security in the 21st century and reopened the debate on nuclear energy.

397In May 2006, Mr Howard announced plans to investigate both nuclear energy and uranium mining. The nuclear debate is of paramount interest for Australia as the nation holds close to 40 per cent of the world’s known uranium reserves, but has yet to embrace nuclear power. The Prime Minister appointed Dr. Ziggy Switkowski, nuclear physicist and former head of Telstra, as chairperson of a ministerial taskforce to research nuclear power and the role it could have in Australia’s future. Debate and criticism followed the announcement of the taskforce, as Mr Howard was labelled pro-nuclear, calling into question the objectivity of his goals.8 The six taskforce officials – particularly the appointment to the chair of Dr Switkowski, who was himself seen to be pro-nuclear – compounded this criticism.9 We will return later to the importance of the nuclear energy taskforce and its appointed members.

Several factors influence current government decisions to revive the nuclear debate. First is the Australian mining industry’s recognition of the potential for increased profit and global status because of increasing world energy demands. The Australian mining industry was guaranteed these things when the Labor party overturned its 23-year-old Three Named Uranium Mines Policy at its national conference in April 2007, allowing Australia to increase uranium exports worldwide.10 Second, global concerns over pollution and climate change have brought energy debates to the forefront of international talks.

Greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels such as coal – which accounts for nearly 80 per cent of energy in Australia – are on the rise.11 Nuclear energy could provide a viable alternative to coal-burning power plants and would bring Australia into the same arena as Europe, the United States and many other nations. There are, according to the

398International Atomic Energy Agency, approximately 435 nuclear power reactors in operation in 31 countries around the world.12

The recent surge of interest in nuclear energy has been propelled by US President G W Bush’s announcement of a ‘nuclear renaissance’, which presents benefits to political and business agencies throughout Australia. ‘Nuclear renaissance’ combines two polar ideals, one of destruction and one of rebirth, the irony of which has not been lost. As part of President Bush’s Advanced Energy Initiative, the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership (GNEP) seeks to develop worldwide consensus on enabling expanded use of economical, carbon-free nuclear energy to meet growing electricity demand. It will use a nuclear fuel cycle that enhances energy security, while promoting non-proliferation.13 President Bush is adamant that his new energy plan incorporates the global market – inviting all nations to participate.

The GNEP ensures that stable governments produce energy using nuclear technologies and store the waste by-product of nuclear power plants.14 Australia is in a unique position as a supplier country – a nation that mines uranium but is not an active user of nuclear energy technologies. Apart from the Lucas Heights research reactor in Sydney, Australia does not currently have an operational nuclear power plant. The GNEP inferred that Australia might have to accept nuclear waste from other countries, reprocess the nuclear waste in accordance with non-proliferation guidelines and store the reprocessed nuclear waste for an indeterminate amount of time. 399

The NPT is a landmark international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote co-operation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament. The Treaty represents the only binding commitment in a multilateral treaty to the goal of disarmament by the nuclearweapon States. Opened for signature in 1968, the Treaty entered into force in 1970. A total of 187 parties have joined the Treaty, including the five nuclear-weapon States. More countries have ratified the NPT than any other arms limitation and disarmament agreement, a testament to the Treaty’s significance.

Figure 12.1 UN Non-Proliferation Treaty

Source: UN Department for Disarmament Affairs

The GNEP will persuade countries that are not signatory members of the UN Non-Proliferation Treaty (see Figure 12.1) into signing, by providing them with safe and secure methods of disposing of their nuclear waste. Also, by having countries like Australia, and possibly Canada, accept and process nuclear waste, it ensures the potential for proliferation is kept at a minimum. GNEP is an initiative by the United States and President Bush to press other nations to increase their civilian nuclear technologies, and perhaps, in the process, decrease the availability of non-civilian nuclear supplies, such as plutonium.15

India and China are poised to control the fate of global nuclear energy campaigns. China is set to increase its nuclear power five-fold by 2020, and India is planning twenty to thirty new reactors by 2020.16 The globalisation of nuclear energy technologies – through a mechanism such as the GNEP – facilitates China and India’s expansion of nuclear

400energy reactors. Without uranium to power the new reactors, China and India will have sought the technology in vain, which is why the decisions about nuclear energy in Australia become so crucial.

A Newspoll conducted in May 2006 found that 51 per cent of Australians were against “nuclear power stations being built in Australia” and 38 per cent were in favour.17 One month later a Roy Morgan poll found that that 49 per cent of participants approved of the introduction of “nuclear power plants replacing coal, oil, and gas power plants to reduce greenhouse gas emissions” and 37 per cent disapproved.18

Influence and strategic communication

Communication often involves the transfer of information in a one-way flow. Information can then be presented strategically to persuade the audience toward certain beliefs or actions. The normative model for communication in Australian politics is the information model, which stipulates a one-way flow of communication from the government and disseminated to the public through the media.19 The Australian Government, during this campaign, employed informative and persuasive strategies. Due to the framing of the issues, however, much of the information represented as informative and facilitating an unbiased public debate on the issue, actually operated more persuasively, integrating the public within a defined worldview.

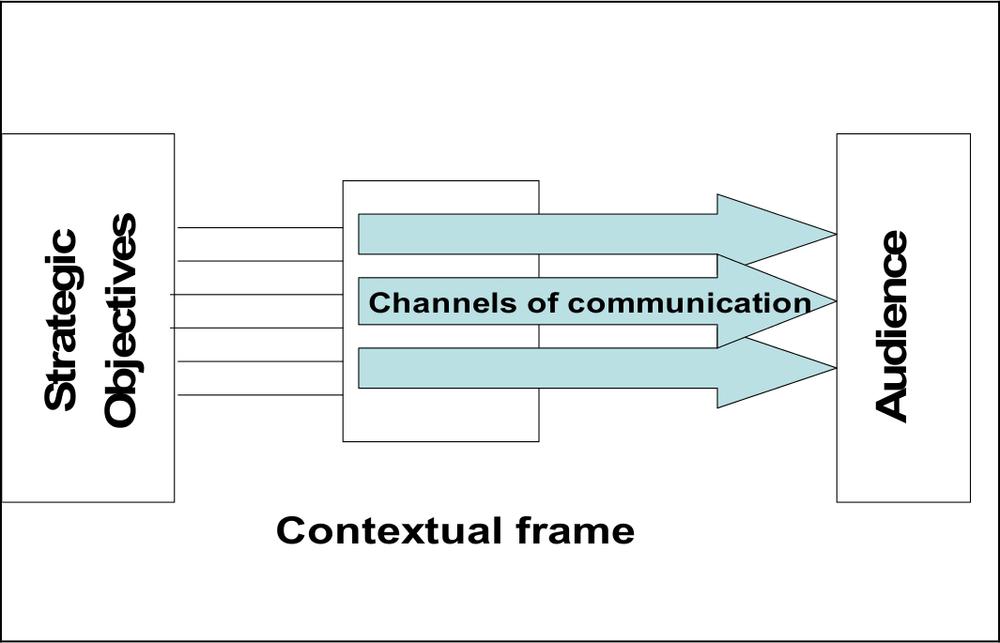

By creating a worldview and interpolating themselves into it, politicians create a framework for their communication with the public. Their goal is to have the public accept the framework presented as reality. Several frameworks were constructed for the nuclear campaign until a strategic fit was found (refer to Figure 12.2 for an illustration of strategic communication).

401To understand the process of political communication, it is necessary to comprehend the environment in which it operates and the ways in which political information is presented and processed. Democracy requires that people have access to information on which to base their political choices. Governments’ require the consent of people to legitimise their offices and successfully implement policy.

Figure 12.2 The contextual frame

Political communication is designed to produce an effect on the actions and beliefs of individual citizens and the society as a whole.20 In the dual processes of decision-making and legitimation there are: ‘insiders’ who are privy to policy debates and involved in decision-making; ‘semiinsiders’, who are aware of the decision-making going on by the elites, but are observers, rather than participants; and ‘political outsiders’, the public who consume the mass media disseminated hype.21 Two political spheres emerge in this process; the sphere of elite politics, with an emphasis on policy making and the sphere of mass politics, with an emphasis on ‘steering voters’.22 The Australian Government’s nuclear

402campaign can be seen as operating in both spheres. In the elite politics sphere, the campaign developed earlier than in the campaign being undertaken in the sphere of mass politics.

As policy goals are established, persuasive methods are employed to steer public opinion. This is a form of hegemony building. Hegemony involves developing consent and legitimacy, so that the population accepts as ‘natural’ the decisions and discourses of the dominant. It also involves organising alliances amongst the elite.23 The shaping of public opinion can be described as manufacturing consent, which can be achieved by strategic planning in a political public relations campaign. The increase in mediated politics has necessitated the incorporation of professional communicators into the political process. A symbiotic relationship has developed between politicians, communicators and the media. Politicians rely on publicity and journalists often rely on information supplied from political communicators.

Opportunities arise for communicators to present information in a particular frame, which can direct the public’s attention and affect the way issues are considered. The mass media, therefore, becomes implicit in the strategic construction of publics and public opinions. The outcome is a public that perceives that it participates in the decision making process, however, in reality it is distanced and obstructed from substantive politics.24 The incorporation of modern media techniques appropriated from the public relations industry is argued to have deemphasised party ideology, causing the decision making process to move away from party level and the public space of parliament to the private offices of the leader and senior ministers.25

Political players remain extremely influential in deciding which worldviews “become hegemonic,” as politicians endorse certain ideologies, while rejecting others. The popularisation of worldviews is not an issue of simple production of “appropriate knowledge”, but an

403issue of information dissemination26 – indicative of a symbiotic relationship between the media, professional communicators and politicians.27

Campaign staging and development

Analysis of political communication has concentrated on the process of election campaigning. While various stakeholders may be peculiar to a particular campaign, the principle groups involved in election campaigning – politicians, media and citizens – remain the same in an issue campaign. Election and issue campaigns are about informing, persuading and mobilising stakeholder groups and the broad strategies used to develop and direct an effective election campaign are similar to those involved in an issue campaign. It is important to remember that a government’s primary goal, regardless of any other campaign being conducted, is the retention of an electoral majority.28

A political campaign like any public relations campaign has a distinct starting and finishing point. A successful campaign will have a clearly defined goal, well-formulated and measurable objectives with aligned tactics. Campaign objectives are designed to provide information and to effect attitudinal and behavioural change. Objectives are directed towards specific stakeholder groups, while tactics are the visible elements devised and implemented to achieve the objectives.

There are different models for structuring a campaign. While a campaign should have a linear direction, the strategy may require modification to ensure achievement of the goal. Strategy can be defined in terms of gaining a competitive advantage over an opponent and is influenced by the skill of the political player and the available financial and technological resources. Most models emphasise the importance of preliminary and continuing research, setting objectives, enacting tactics and evaluating the results. The importance of a well-calculated strategy and the employment of reasonable tactics is the foremost task for

404political campaign teams and a well-constructed campaign will have an alignment of all these elements.

The model used in this chapter to analyse the Australian Government’s nuclear energy campaign has been adapted from a model that originated to evaluate political campaigning in US elections.29 There are five stages in the adapted model: (1) preliminary, (2) nomination, (3) attack, (4) regroup, and (5) deliver.

Although the stages are discrete and contain particular communicative functions, each stage informs the other and any analysis of the effectiveness of the campaign must include all stages and the relationships that exist between them, which will be discussed below. Because the campaign had not reached a conclusion during the course of our research, our analysis focuses on the first three stages – preliminary, nomination, and attack.

The government’s nuclear energy campaign

The prelude

In March 2005, the Australian Government announced an inquiry into the uranium industry and a possible expansion of the country’s three mines.30 Three months later the Prime Minister was reported as saying that many would think it odd, given the vast supplies of uranium that we would not allow a debate on nuclear power.31 In August 2005, the Federal Government exercised its Commonwealth powers and assumed control of the Northern Territory’s uranium mining to guarantee certainty to the industry and ensure the expansion of exports.32

405In November 2005, Federal Science Minister, Brendan Nelson and Federal Industry Minister, Ian MacFarlane lodged a submission with the Prime Minister for an inquiry into the benefits and impact of Australia developing a domestic nuclear power industry. Dr Nelson was careful to state that a possible inquiry was a matter for the Prime Minister and the Government.33

The preliminary stage

Developing the platform

Speaking in Ottawa on 19 May 2006 ahead of meetings with the Canadian Government and the US Government, the Prime Minister told Southern Cross Radio that nuclear power was closer “than some people would have thought a short while ago” and he hoped “that we have an intense debate on the subject over the months ahead”.34 Three months earlier, the Prime Minister had told Southern Cross Radio, “If the economics of energy lead us to embracing nuclear power, then we should be willing to do so”.35 In the 19 May interview, he restated the governing economic considerations; however, he extended the frame of the issue to include the “environmental advantages of nuclear power”.36 Indeed, the Prime Minister’s language regarding nuclear energy on the trip to North America marked a overtly positive stance on the issue. The following week on 26 May 2006, the government’s Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) released a report to the Federal Science Minister, Julie Bishop, concluding that electricity generation from nuclear power would be competitive with coal.37

With these comments and the release of the ANSTO report, the Prime Minister was developing the platform of the campaign and framing the issue of nuclear energy as one with possible economic and

406environmental advantages. Economic considerations are at the core of the predictive model of political communication and are powerful determinants of voting patterns.38 The Prime Minister’s success in retaining office has been attributed to the economic prosperity of Australia over the last decade.39 If stakeholders perceive the Prime Minister as a responsible and successful economic manager and trust his economic qualifications, then a contentious issue such as nuclear power may become acceptable within an economic frame because, “Without trust there is no persuasion”.40 The leader of any campaign, and in our case the Prime Minister, is an integral part of the process. As a campaign gains momentum, a complex network of communication and perception is woven together intricately by the media and the government.

Researching the issue and modifying models

A function of the preliminary stage, research, was realised when the Prime Minister announced on 6 June 2006 that Cabinet had approved the establishment of a Prime Ministerial taskforce – the Uranium Mining Processing and Nuclear Energy Review (UMPNER) – to examine uranium mining, processing and nuclear energy in Australia.41 As mentioned previously, Dr Switkowski, a nuclear physicist and former CEO of Telstra, was appointed as chairperson. Some weeks later, Dr Switkowski resigned as a director of ANSTO amidst accusations of a conflict of interest.42

The taskforce invited submissions and a draft report was released publicly in November 2006. Inviting the public to participate in the process fulfils a function of the nomination stage and is bound to the ideology of democracy. The invitation was not widely publicised;

407however, it is the appearance of inviting participation that is, perhaps, more important in political communication. Public participation can be troublesome for governments because it disrupts the business of governing, implementing policy, directing resources and creating legislation.43 Additionally, perceived time and resource constraints may have restricted the mass public’s ability to lodge submissions. The taskforce, however, did identify supportive and oppositional stakeholders, with the intention of inviting their submissions.44

Campaigning for an issue such as nuclear energy requires the issue be deemed fit for political consideration so it can be placed within the popular political dialogue. The Prime Minister successfully integrated the issue of nuclear energy into the political dialogue and validated the reasoning behind its inclusion by creating a taskforce. The introduction of the taskforce established the seriousness of the issue, confirmed that nuclear energy was a viable competitor to other energy sources, such as fossil fuels, and placed the debate in the public forum. For an issue to gain traction, it must gain visibility, particularly in the media.45 The establishment of the taskforce was the Prime Minister’s way of declaring the beginning of the campaign.

Appointing independent experts to the taskforce46 in the fields of nuclear science, economics and the energy sector, allowed the government to be perceived as being concerned and seeking the ‘truth’ and providing an objective assessment of the issue. In fact, the Department of Prime Minster and Cabinet conceived of the terms of reference, which would direct the inquiry’s review and the Prime Minister chose the taskforce members on advice from the Department.47

408In seeking to control communication flows, the government instructed the taskforce members to route any requests for interviews through the review’s secretariat.48 The issues paper,49 provided by the government and attached to the review, reinforced the predominant economic frame. The paper contained 86 questions regarding economic issues, nine questions regarding environmental issues and 23 questions regarding health, safety and proliferation issues.

It is significant for the analysis of the campaign that the Prime Minister himself appeared to be the person who initiated dialogue surrounding the issue. The taskforce was established in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and only in rare instances did ministers other than Mr Howard discuss the issue in the media. There is, therefore, a centralised information system for prime-ministerial public relations.50 The fact that Dr Switkowski, a well-known and high-profile business personality, headed the taskforce is another important element of the campaign. Both these circumstances lead to the question as to what extent celebrity plays a role in the current campaign.

Celebrity has been described as a phenomenon “tied to the rise of visual mass media”, invented by the Hollywood studios’ system to promote their actors through images and “a powerful tool for steering mass publics”.51 In terms of political communication, John Howard has been identified as one of the leaders whose character has been scripted by spin-doctors to create a celebrity politician “with the sorts of ‘ordinary’ features voters could identify with”.52 For the purposes of the campaign, the appointment of Dr Switkowski appears to be as close as one could get to celebrity-status without losing credibility. He has a very useful mix of qualities, which includes expert knowledge on the science of nuclear energy, knowledge of political processes and extensive media experience.

409The taskforce creation can be seen as a primary instrument of the routine processes of politics and can thereby legitimise possible further action. In this sense, it can be interpreted as a pseudo-event, whose creation is another strategy of incumbents.53 If one assumes the decision to extend uranium mining and introduce nuclear power was made before the campaign commenced, the taskforce would only serve to add more credibility to this decision. Indeed, shortly before the taskforce reported, the Prime Minister endorsed the development of a nuclear industry in Australia.

Another function of the preliminary stage is the modification of conflicting existing models. The Government’s 2004 white paper on energy policy, Securing Australia’s energy future, stated that fossil fuels will “meet the bulk of the nation’s energy needs”.54 Nuclear energy was tabled as a “reserve” energy technology – one where Australia has less of a strategic interest – behind Australia’s market leading and fast-following technologies such as coal, hot dry rocks, natural gas and wind. Even hydrogen – another reserve energy technology – was considered more likely than nuclear to potentially deliver low-emissions energy.55 The policy was updated in July 2006 and states, “There is significant potential for Australia to increase and add value to our uranium extraction and exports”56 and “[to invest] in leading-edge, clean energy technology while being pragmatic about what technologies help Australia achieve its economic, energy and environmental goals”.57 The use of the word pragmatic is interesting and one could infer from its use that nuclear energy, while perhaps not the most popular choice for clean energy technology, is nonetheless, the most practical. 410

Rhetoric and Persuasion

The employment of rhetorical devices serves to reinforce existing beliefs and values and to introduce and embed an issue within a framework of those beliefs and values, thereby legitimising and popularising the issue. The Prime Minister has steered the debate on nuclear energy by employing the rhetorical device of comparing our failure to exploit uranium processing as analogous to Australia’s historical experience of having our wool processed overseas to the country’s economic disadvantage.58

In his address to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia on 18 July 2006, the Prime Minister said Australia has “global responsibilities including environmental stewardship” and “a growing number of environmentalists now recognise that nuclear energy has significant environmental advantages”. In the same address, the Prime Minster claimed Australia has “the makings of an energy superpower”, if we grasp the opportunities that globalisation offers by exporting to an expanding energy market.59 The symbol of Australia as a ‘superpower’ is a powerful instrument of persuasion. He concluded the nuclear component of his speech by saying, “…if we sacrifice rational discussion on the altar of anti-nuclear theology and political opportunism, we will pay a price. Maybe not today or tomorrow, but in 10, 15 or 20 years Australia will surely pay a price”.

Both the Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister have suggested there has been a shift in attitudes towards nuclear energy. During the press conference to announce the establishment of the taskforce, the Prime Minister said, “My mind remains open. I am not persuaded as yet, although in my bones I think there has been a fundamental change.”60 The Foreign Minister told The Advertiser, “My take on where the public is at is that there has been a quantum shift in public opinion on this issue

411in the last ten years”.61 These types of agenda-setting comments can create a “spiral of silence”,62 where people whose views diverge from the perceived norm refrain from debating issues that exclude them from the popular majority.

The Nomination Stage

Nurturing the Stakeholders63

Fulfilling one of the central functions of the nomination stage – to nurture stakeholder groups – can entail making promises. The issue of storing spent nuclear fuel rods was raised early in the campaign when the government confirmed Australia would store France’s spent fuel from its uranium exports.64 Following private discussions between the Prime Minister and US officials in May 2006 regarding Australia’s potential role in the US created GNEP, speculation ensued regarding the possibility of Australia becoming a global repository for spent fuel if an enrichment industry was to proceed.65

The Prime Minister told the Nine Network in July 2006, that Australia has a responsibility to dispose of nuclear waste from its exports and that it is a “Nimby head in the sand attitude”, to export uranium and refuse to store the waste.66 The unsavoury image of Australia as a radioactive waste dump, however, prompted the Prime Minister to alleviate public concern and tell ABC Radio less than one month later, “I am not going to have this country used as some kind of repository for other people’s

412nuclear problems … waste problems”.67 But within the Australian Parliament, policy changes had already been implemented. The ANSTO Amendment Bill 2006 was passed on 20 June 2006 to provide more flexibility – particularly in terms of nuclear waste storage – by allowing the incorporation of waste “not exclusively from ANSTO’s reactors”.68

Dr John White chairs the Australian waste company, Global Renewables and the federal government’s Uranium Industry Framework steering committee: a committee that has been meeting since August 2005 to advise the Government on uranium policy. While visiting the US in November 2006, White discussed with New Matilda, his and Australia’s potential leadership role in nuclear fuel leasing, which includes the return to Australia and storage of nuclear waste. Apart from the considerable economic benefits, White stressed the diplomatic benefits in a display of demagoguery:

If we agree to do this for America, we will never again have to put young Australians in the line of fire. We will never have to prove our loyalty to the US by sending our soldiers to fight in their wars, because a project like this would settle the question of our loyalty once and for all.69

This demonstrates that the operation of the Australian Government’s nuclear campaign has been progressing strategically in very different ways at the elite and mass levels.

The major existing fossil fuel energy providers – the coal and gas industries – have received some reassurance from the government that they will continue to provide base-load energy to the electricity grid. The Industry, Tourism and Resources Minister Ian Macfarlane said on 16 October 2006, “We will not turn our backs on Australia’s traditional

143energy sources – like coal and gas”.70 In an address to the Energy Networks Association (ENA) on 11 September 2006, the Minister spoke of the gas industry as “one of the foundation stones of the Australian economy”71 and of the solid prospects for its future growth.

Changing the frame – the need for a strategic shift

One of the difficulties the campaign has encountered is public assertions, by important business leaders in the uranium industry, which question the economic viability of developing uranium processing and a domestic fuel cycle. These statements implicitly refute the Prime Minister’s positive economic framing of the issue. Rio Tinto and the French company, AREVA, argued that developing uranium processing in Australia has no demonstrated economic benefits, due to the current and immediate future market saturation.72 In its submission to the taskforce, BHP Billiton stated its belief that uranium conversion, enrichment and fuel leasing is economically unviable, as is nuclear power in the absence of significant carbon taxing.73 However, Dr Switkowski told ABC Radio on 5 October 2006 that nuclear power generation could be competitive with conventional sources.74

414For the past two decades, nuclear energy has been the most heavily subsidised energy industry in the world.75 During this campaign, the Prime Minister refused to confirm whether the government would subsidise the industry and remained staunchly opposed to carbon trading.76 During the press conference to announce the taskforce he stated, “[sic] Our general policy is that we don’t normally start an industry up with government support that is our general policy”.77 As the Prime Minister has continued to frame the issue as one with great economic benefits, it may have been damaging to admit to the need for government subsidies. Between May and October 2006, the Finance Minister, Nick Minchin, repeated his belief that a domestic nuclear industry in Australia is economically unfeasible in the short-term.78 These are interesting comments from a Cabinet minister. At the time, it could have been questioned whether he was asserting an independent view or if it was a strategic manoeuvre to prime the public for the possibility of government subsidies or carbon pricing to assist the development of a nuclear industry.

At any rate, with the public’s escalating and widespread concern about the consequences of global warming,79 opportunities arose for a strategic shift in focus to the environmental advantages of nuclear power. It was evident that climate change would probably become an important election issue and the government has been criticized about its late

415acknowledgement of climate change and its refusal to seriously address the issue.80

The government had grasped opportunities to align itself with credible environmental prolocutors – spokespeople – to promote the ‘environmental advantages’ of nuclear energy and to allay concerns regarding waste disposal and reactor safety. There was the last-minute and failed attempt to procure Greg Bourne – former president of BP Australia and current CEO of conservation group WWF Australia – as a member of the taskforce.81 In early May 2006, Bourne publicly accepted that Australia would continue mining and exporting uranium to an increasing world market.82 In June 2006, the Prime Minister enlisted the credentials of Tim Flannery, scientist, environmentalist and 2006 Australian of The Year in an ABC Radio interview. Flannery had given circumspect endorsement to nuclear power as an option for addressing global climate change.83 On 8 May 2006, the environmental movement in Australia united and released a joint media statement opposing all aspects of the nuclear industry.

The media’s role

The nuclear debate remained relevant throughout July and August 2006 in the media, with stories of nuclear controversy; everything from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty to the anniversary of the Hiroshima bombings entered the public domain. Coverage, however, was limited until the submissions made to the taskforce were released in September 2006. Furthermore, the Prime Minister provided fewer spectacles and speeches, which lessened the number of tangible events on which to report. Tim Flannery, however, became a target amidst scrutiny for his perceived endorsement of nuclear power. Flannery countered with an interview with WWF Australia.84 In the interview, he includes uranium

416as an energy alternative. However, he also indicts Australia as “the most backward nation on the planet” in terms of how political and industry leaders address both global warming and the debate surrounding alternative energies.

An article in The Age on 26 August 2006 entitled ‘Forget about left or right, I’m just the weatherman’, asserts that Flannery’s “position on nuclear energy has been misrepresented”.85 The article depicts Flannery as not anti-nuclear power; however, Flannery argues against the use of ‘dirty’ fuels, such as coal and gas. He instead points to alternative renewables, such as solar and wind power, which he argued appeared to be less of a priority for the federal government. He described the government as “the worst of the worst”, with regard to seriously addressing climate change and was “incredulous” at being made a target of “the far left and far right”.

On Enough rope with Andrew Denton on 11 September 2006, former US Vice-President Al Gore called the United States and Australia the “Bonnie and Clyde of the global community” for their continued resistance to the Kyoto protocol. He furthermore pointed to Mr Howard’s policy as in need of change. The Australian ran two stories on the same day. First, an article entitled ‘Australia could show China the way: Gore’,86 offered commentary with specific reference to Mr Gore, who voiced concern regarding proliferation. Mr Gore was also quoted as saying, “It’s no secret that the Prime Minister and I disagree on the issue, but I think he’s a smart man with a generally open mind when new evidence is available”. Second, The Australian published an interview with the Prime Minister under the headline ‘Documentary films don’t guide my environment policy’.87 In the interview, Mr Howard once again rejected the Kyoto protocol as acting against the economic interests of the country and presented accusations of ‘alarmist’ views specifically regarding global warming, which ironically he employs as a backdrop for the ‘rational debate’ on nuclear energy. 417

Steering the debate: a tactical bid for control

The Foreign Minister stated in a speech on 11 October 2006 that the main reason for Australia to commence generating nuclear power would be to reduce greenhouse emissions and not for energy security and “we don’t need Al Gore to tell us that the growth in carbon emissions from fossil fuels is a major global challenge that must be confronted”.88 Six days later in an address to the 15th Pacific Basin Nuclear Conference in Sydney, Ian MacFarlane asserted that nuclear energy could be “a major part of the global strategy to curb greenhouse emissions” and “the issue of uranium and nuclear power is as much about lowering greenhouse gas emissions as it is about the supply of energy”.89 On the same day, the Prime Minister asserted, “I believe very strongly that nuclear power is part of the response to global warming, it is clean green”.90 Statements of belief such as this are more difficult to counter than statements of fact because beliefs tend to exist as ‘givens’91 and are less subject to scrutiny than policies.

The day after the 15th Pacific Basin Nuclear Conference, the Prime Minister publicly endorsed the domestic use of nuclear power for the first time. He stated, “I just think that if we’re serious about having a debate about global warming, particularly as the holder of some of the largest uranium reserves in the world, we have got to be willing to consider the nuclear option”. His promotion of nuclear power came almost a month before the results of the taskforce’s inquiry were to be released and just over a week after the effects of North Korea’s nuclear detonation were being considered both domestically and internationally.

418In response, the then federal Opposition leader, Kim Beazley, contended that Australia’s future is, “renewables not reactors” and “there will be no nuclear power in Australia under a Beazley Labor Government”.92 Martin Ferguson, the federal Opposition’s energy spokesperson, accused the government of “diversion”93 by promoting the nuclear debate ahead of the pressing need to act on clean coal technology and renewable energy sources.

The following week the Federal Treasurer, Peter Costello and Ian MacFarlane announced a $75 million grant to build a large-scale solar concentrator in Victoria and $50 million for a brown coal drying and post-combustion carbon dioxide capture and storage project. Further announcements regarding the Government’s $500 million Low Emissions Technology Demonstration Fund (LETDF) followed in the ensuing weeks.94 While the fund was established in July 2006, the timing of this announcement appeared to be a strategically placed response to Mr Beazley’s and Mr Ferguson’s comments.

The attack stage

The appropriation of funds for grants is a powerful, pragmatic strategy of the incumbent as is the establishment of taskforces to investigate issues of public concern.95 By allocating grants, the government sought to develop and maintain mutually beneficial relationships with the renewable energy and fossil fuel industries, while at the same time appearing to be genuinely concerned about and responsive to the issue of global warming. The announcement partially countered criticism that the government was deliberately neglecting, and perhaps even sabotaging, the renewable energy sector by refusing to increase Australia’s Mandatory Renewable Energy Target (MRET), thereby

419dissuading investment.96 The promise of further grant allocations provided opportunities for pseudo-events to attract media attention and to capitalise on that attention by directing the issue.

Aside from shifting attention from the economic focus of the nuclear debate, it also enabled the Government to attack vigorously opponents of nuclear energy. The Prime Minister declared people who oppose nuclear energy, but demand solutions to climate change to be “unreal” and that many “rabid environmentalists”97 have realised the benefits of nuclear energy. The converging issues of climate change and nuclear energy may benefit the Government’s election strategy by dividing the federal opposition, which remains ideologically opposed to the domestic use of nuclear energy and uranium enrichment, but was at that time considering amending the Three Named Uranium Mines policy in the presence of the nuclear debate.98 The Prime Minister warned that the Opposition would attempt to run a ‘fear campaign’, but the public was ready for a mature debate.99 The implication was that the Labor Party was attempting to manipulate the Australian public with emotive appeals.

Much of an elected representative’s time is invested in providing educative mechanisms to the public. When the policies being promoted are in line with public opinion, a straightforward informational model of communication can be employed. When the public is likely to resist the elite policy decisions, more persuasive methods are needed. Hegemonically, this can be viewed as the policy elite maintaining the compliance of the masses.100

420Because communication is contextual, strategists need to be aware of the environment in which the communication will take place, when developing political campaigns. The matching of campaign to environment is known as the search for ‘strategic fit’.101

Taskforce findings and the continuing campaign

On 21 November 2006, the taskforce released its findings in a draft report that was followed by the final version on 12 December.102 Dr Switkowski, who was appointed chairperson of ANSTO in March 2007, and the other taskforce members asserted that under certain conditions it would be probable that Australia could introduce nuclear power in the medium-term. According to their estimations, the first plant could be operational in about ten years: “The review sees nuclear power as a practical option for part of Australia’s electricity production.”103

The findings of the report reflected the reframing that has taken place during the campaign – nuclear energy was again very much seen against the background of climate change. In fact, in an interview on ABC’s Lateline on the day of the draft report’s release, Dr Switkowski said that, at the beginning of the inquiry, climate change was an issue they had hoped to keep separate from their discussion. But fuelled by strong community interest in climate change the connection had to be made as to how the adoption of alternative energy sources could help the country lower its greenhouse gas emissions.104

While the taskforce emphasised that nuclear power would be around 30–50 per cent more costly than energy from coal-fuelled power plants, it was seen as a potential part of the solution to tackle climate change: 421

Nuclear power is an option that Australia would need to consider seriously among the range of practical options to meet its growing energy demand and to reduce its greenhouse gas signature.105

However, to make nuclear energy competitive a form of emission pricing would be required. Dr Switkowski made this clear when he said that investment in nuclear power could and should proceed only if a cost on carbon emissions be imposed.106

Two weeks after the findings of the taskforce were made public, Mr Howard announced that a joint government/business Prime Ministerial Task Group to investigate carbon trading would be formed. In his announcement he made no specific reference to the finding by Dr Switkowski that emissions pricing would be a condition to making nuclear energy competitive.

The task group presented its findings on 31 May 2007 and recommended that Australia establish a carbon trading system by the year 2012 with gradual emissions reductions through a cap and trade model. It did not name a specific target in its final report saying a “long-term aspirational goal”107 could be announced in 2008. The task group also suggested winding up the Mandatory Renewable Energy Target (MRET).108

While the task group on emission trading was still in the process of gathering relevant data, the Prime Minister made a further important decision on 28 April 2007. On the same day, during its national conference, the Labor party, against strong internal opposition, voted to overturn its 25-year-old ‘no new uranium mines’ policy, while emphasising its opposition to the domestic use of nuclear energy. Mr

422Howard in turn, in a speech to the Victorian Liberal Party conference announced further support for a possible nuclear future by announcing a “strategy to increase uranium exports and to prepare for a possible expansion of the nuclear industry in Australia”.109 Part of this effort would be the removal of legislative bans to construct nuclear power stations in Australia, namely the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act and the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Act.

According to the Prime Minister, the country would also apply for membership of the Generation IV International Forum, a group of 13 countries collaborating on the development of the fourth generation of nuclear reactors. In addition, four work maps in relation to nuclear energy are to be developed by the federal government with areas including: a nuclear energy regulatory regime; skills and technical training; enhanced research and development; and “communication strategies so that all Australians and other stakeholders can clearly understand what needs to be done and why”.110

Communication with the wider public is of particular importance – given what we have ascertained concerning the campaign between June and October 2006. In fact, the taskforce itself acknowledged this is a deciding factor for a possible nuclear future in Australia:

“Community acceptance would be the first requirement for nuclear power to operate successfully in Australia. This would require informed discussion of the issues involved, including the potential costs and benefits of nuclear power.”111

In a statement on the day of Mr Howard’s April 2007 announcement, Ian MacFarlane said funds would need to be allocated to educate the

423public about the value of nuclear power.112 A uranium industrycommissioned poll from May 2007 suggests a slight majority of 51 per cent is in favour of nuclear power generally,113 but two-thirds of Australians say they were opposed to nuclear power stations being built in their area.114

At the end of May 2007, The Sydney Morning Herald revealed that the federal government was planning to spend $23 million on a public information campaign on its climate change strategy. Proposed measures for the campaign include television, radio and newspaper advertising, as well as a booklet on energy saving that would be sent to seven million households.115 Whether this initiative would run parallel to a public awareness campaign on nuclear power or both issues would be integrated into one single climate change campaign frame was not yet clear.

Conclusion

Incredible amounts of time are spent planning campaigns by political communicators. Implementation, however, is a much more difficult and intimidating undertaking.116 As a result, communicative strategies are most often minimalist in nature and feature asymmetrical, or one-way flows of communication. This is apparent through tactics such as speeches, which are most effective when supported by other tactics also communicated asymmetrically, for example, media releases. Advances in technology have developed an increased ability to produce and disseminate these tactics, through vehicles like the internet and television. Visible tactics by the government were apparent, concluding the existence of an issues-based campaign surrounding nuclear energy. It

424must be assumed that because a campaign exists, the tactics comprise an element of an overall goal-oriented strategy.

Initially, the strategic frame adopted by the government was predominantly economic. The fact that this frame appeared to have receded in importance as the campaign progressed indicated that there was a search, in the preliminary stages, for a strategic fit. Acknowledging that the Australian public had a strong, historical negative reaction to the nuclear issue, meant that the government had to move carefully so as not to inflame existing negative opinions. The government used prolocutors, such as Tim Flannery, to present a ‘clean green’ image of nuclear energy.

Once the ‘clean green’ message had been established, the Prime Minister could interpellate117 himself in the established worldview, without the suspicion that the claim may have received if being communicated solely from a government position. With the linking of nuclear energy as a solution to global warming, the federal government has found a strong strategic fit that also frames itself as environmentally responsible, an important consideration given the priority the public is placing on environmental concerns in the lead up to the next federal election.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Richard Stanton (School of Letters, Art, and Media, the University of Sydney) whose work forms the basis of this study, for his guidance and support.

1 Commonwealth of Australia, House of Representatives, Votes and Proceedings, Hansard, Wednesday, 30 May 2007, p. 42. http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard/

reps/dailys/dr300507.pdf.

2 Refer to Appendix A for a list of stakeholders.

3 ‘Nuclear chronology’, Four Corners, ABC TV, 22 August 2005. Accessed: http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/content/2005/20050822_nuclear/nuclear-chronology.htm

4 The agreements, treaties and negotiated settlements, Ranger Uranium Environment Inquiry (1976–1977). Accessed: http://www.atns.net.au/biogs/A001270b.htm

5 ‘Nuclear chronology’, Four Corners, ABC TV, 22 August 2005. Accessed: http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/content/2005/20050822_nuclear/nuclearchronology.htm

6 ‘A chronology of Australian mining’, Ready-Ed Publications. Source: http://www.readyed.com.au/Sites/minehist.htm.

7 Parliament of Australia, Parliamentary Library, Politics and Public Administration Group, Chronology of radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel management in Australia, 1 January 2006. Accessed: http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/online/RadioactiveWaste.htm

8 Peake R., ‘Nuclear inquiry still biased, say detractors’, Canberra Times, 9 June 2006.

9 Murphy K Khadem N & Smiles S, ‘Nuclear body has trouble in fusion’, The Age, 8 June 2006.

10 Wilkinson M, ‘Power for the people’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 May 2007.

11 Australian Uranium Association, Sustainable Energy, Nuclear Issues Briefing Paper no. 54, November 2005. Accessed: http://www.uic.com.au/nip54.htm

12 International Atomic Energy Agency, Nuclear Power Plant Information, Number of Reactors in Operation Worldwide (as of 13 of June 2007). Accessed: http://www.iaea.org/cgi-bin/db.page.pl/pris.oprconst.htm

13 U.S. Department of Energy, The Global Nuclear Energy Partnership. Accessed: http://www.gnep.energy.gov/gnepprogram.html

14 Transcript of Clay Sell, Deputy Secretary of Energy; Robert Joseph, Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Foreign Press Center Briefing, Washington, DC, 16 February 2006. Source: http://fpc.state.gov/fpc/61808.htm.

15 Weitz R, Chinese-US Deals Opens Opportunities for Nuclear Cooperation, 4 January 2007. Source: http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/article.aspx?id=453.

16 World Nuclear Association, The nuclear renaissance, May 2007. www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf104.html

17 Newspoll, ‘Australian Attitude on Uranium and Nuclear Power’, May 2006. Source: http://www.newspoll.com.au/cgi-bin/polling/display_poll_data.pl

18 Roy Morgan poll, Finding 4032, 10 June 2006. Source: http://www.roymorgan.com/news/polls/2006/4032/

19 Stanton, R. (2006), Masters Program, Political Public Relations Seminar, 1 August, University of Sydney.

20 Graber D, ‘Political communication faces the 21st century’, Journal of Communication, September 2005, p. 479.

21 Louw E, The Media and Political Process, Sage Publications, London, 2005, pp. 17–18.

22 ibid, p. 22.

23 Gramsci A in Louw, p. 19.

24 Louw, op.cit., pp. 143–171.

25 Kavanagh, D, ‘New campaign communications: consequences for British political parties’, Press/Politics, vol. 1, no. 3, 1996, p. 73.

26 Louw, op. cit., pp. 202–203.

27 ibid, p. 1.

28 Stanton R, Masters Program, Political Public Relations Seminar, 22 August 2006, University of Sydney.

29 Trent J S & Friedenberg R V (2004), Political campaign communication: principles & practices 5th ed, Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., Oxford.

30 ABC News Online, ‘MacFarlane talks down uranium boom risks’, 18 March 2005. Accessed: http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200536/s1326711.htm

31 ABC News Online, ‘PM encourages nuclear power debate’, 9 June 2005. Source: http://www.abc.net.au/news/

newsitems/200506/s1388563.htm.

32 Wilson A & Murphy K, ‘Howard seizes NT uranium’, The Australian, 5 August 2005.

33 ABC News Online, ‘Nelson seeks Aust nuclear power inquiry’, 27 November 2005. Accessed: http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200511/s1517596.htm

34 ‘Nuclear power inevitable, says PM’, The Age, 19 May 2006.

35 ABC News Online, ‘Don’t rule out nuclear future: PM’, 24 February 2006. Accessed: http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/20060602/s1577452.htm

36 ‘Nuclear power inevitable, says PM’, The Age, 19 May 2006.

37 ABC News Online, ‘Nuclear power economically viable: ANSTO’, 26 May 2006. Source: http://www.abc.net.au/news/

newsitems/200605/s1648257.htm

38 Jamieson K H, Everything you think you know about politics: and why you’re wrong, Basic Books, London, 2000, p. 6.

39 O’Brien K, ‘John Howard: 10 years at the top’, The 7:30 report, ABCTV, 2 March 2006. Accessed: http://www.abc.net.au/7.30/content/2006/s1582730.htm

40 Lupia A & McCubbins M, cited in Graber D A op. cit, p. 490.

41 Transcript of the Prime Minister The Hon John Howard MP, press conference, Parliament House, Canberra, 6 June 2006. Source: http://www.pm.gov.au/news/interviews/

Interview1966.html.

42 ABC News Online, ‘Nuclear review chief quits ANSTO board’, 8 June 2006. Source: http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/

2006/06/08/1657943.htm.

43 Louw, op. cit., p. 145.

44 Murphy K, ‘Nuclear debate picks up with show of British energy’, The Age, 5 July 2006.

45 Trent & Friedenberg, op.cit., p. 27.

46 The six-member taskforce was chaired by former Telstra CEO and nuclear physicist, Ziggy Switkowski and included eminent economist, Warwick McKibbin, three additional nuclear physicists and a senior energy sector executive who replaced Sylvia Kidziak.

47 ‘Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Public Administration Estimates (Supplementary Budget Estimates)’, Proof Committee Hansard, Commonwealth of Australia, 30 October 2006, Canberra, p. 62.

48 Kerr J, ‘Green firm dumps N-probe expert’, The Australian, 16 June 2006.

49 Australian Government, ‘Issues paper’, Uranium mining, processing and nuclear energy review, June 2006. Accessed: http://www.dpmc.gov.au/umpner/paper.cfm

50 McNair B, An introduction to political communication, Routledge, London, 2003, p. 161.

51 Louw, op. cit., p. 174.

52 ibid, p. 176.

53 Trent & Friedenberg, op. cit., p. 82.

54 Australian Government, Securing Australia’s Energy Future, June 2004, p. 4. Source: http://www.pmc.gov.au/publications/

energy_future/docs/energy.pdf.

55 ibid, p. 32.

56 Australian Government, Securing Australia’s Energy Future: July 2006 Update, p. 5. Accessed: http://www.pmc.gov.au/energy_reform/docs/energy_update_july2006.rtf

57 ibid, p. 1.

58 Transcript of the Prime Minister The Hon John Howard MP, press conference, Parliament House, Canberra, 6 June 2006.

59 Howard J, Address to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia, Sydney Convention & Exhibition Centre, 18 July 2006.

60 Transcript of the Prime Minister The Hon John Howard MP, press conference, Parliament House, Canberra, 6 June 2006.

61 Russell C, Starick P & England E, ‘Cure or killer – the nuclear future’, The Advertiser, 29 August 2006.

62 Noelle-Neumann E, The spiral of silence: public opinion–our social skin, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1984.

63 Refer to Appendix A for a list of stakeholders.

64 Crowe D, ‘Spent nuclear fuel back in five years’, Australian Financial Review, 19 June 2006.

65 Baker R, ‘Secrecy on Howard’s nuclear trip’, The Age, 29 June 2006.

66 Howard J, Interview with Laurie Oakes on Sunday, Nine Network, 18 June 2006. Accessed: http://sunday.ninemsn.com.au/sunday/political_transcripts/article_2009.asp

67 Frew W, ‘PM blows cold on nuclear dumping’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July 2006.

68 Parliament of Australia, Department of Parliamentary Services, Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation Amendment Bill 2006, Parliamentary Library Bills Digest, 20 June 2006, no. 153, 2005–06, ISSN 1328-809.

69 Macken J, ‘Nuclear Debate: Part One: The Plan’, New Matilda, 8 November 2006. Accessed: http://www.newmatilda.com./home/articledetailmagazine.asp?ArticleID=1913&HomepageID=168

70 Macfarlane I, Speech to the 15th Pacific Basin Nuclear Conference, 16 October 2006. Accessed: http://minister.industry.gov.au/index.cfm?event=object.showContent&objectID=4ECF4EE3-CDB6-D660-70446A89BBAA72ED

71 Macfarlane I, Address to the Energy Networks Association (ENA) Gas Speak Colloquium, 11 September 2006. Accessed: http://minister.industry.gov.au/index.cfm?event=object.showContent&objectID=9BC6946C-CFFD-463B8837B15F93C2A58E

72 AREVA, Submission to the uranium mining, processing and nuclear power review, September 2006. Source: http://www.pmc.gov.au/umpner/

submissions/72_lowres_sub_umpner.pdf. Rio Tinto, Submission to the uranium mining, processing and nuclear power review, September 2006. Source: http://www.pmc.gov.au/umpner/

submissions/197_sub_umpner.pdf. Kerin J, ‘Miners cool on enrichment’, Australian Financial Review, 1 September 2006.

73 BHP Billiton, Submission to the uranium mining, processing and nuclear power review, September 2006. Source: http://www.dpmc.gov.au/umpner/

submissions/223_sub_umpner.pdf.

74 ABC News Online, ‘Nuclear energy panel considers Chernobyl’, 5 October 2006. Source: www.abc.net.au/news/

newsitems/200610/s1755907.htm.

75 Energy Subsidies and External Costs, UIC Nuclear Issues Briefing Paper no. 71, February 2007, Uranium Information Centre. Accessed: http://www.uic.com.au/nip71.htm

76 Transcript of the Prime Minister The Hon John Howard MP, press conference with The Hon Peter McGauran MP, Minster for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Parliament House, Canberra, 17 October 2006. Accessed: http://www.pm.gov.au/news/interviews/Interview2184.html

77 Transcript of the Prime Minister The Hon John Howard MP, press conference, Parliament House, Canberra, 6 June 2006.

78 Crouch B & Farr M, ‘No nuke plant in 100 years Liberal leaders at odds’, Sunday Mail, 21 May 2006. ABC News Online, ‘Minchin downplays Macfarlane’s nuclear energy comments’, 17 October 2006 source: http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/

2006/10/17/1767227.htm.

79 The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, Global Views 2006, Source: http://www.lowyinstitute.org/Publication.asp?pid=470.

80 Silkstone D, ‘Forget about left or right, I’m just the weatherman’, The Age, 26 August 2006.

81 Murphy K, ‘Nuclear body has trouble in fusion’, The Age, 8 June 2006.

82 Hodge A, ‘Green group accepts U-mines’, The Australian, 4 May 2006.

83 Doherty B, ‘Nuclear way to go: Flannery’, The Age, 5 August 2006.

84 This was made available to the public in print on the organisation’s website in addition to a podcast available through Apple ITunes (Flannery, personal interview). Accessed: http://wwf.org.au/articles/interview-with-tim-flannery

85 Silkstone, op. cit.

86 Bodey M & Warren M, ‘Australia could show China the way: Gore’, The Australian, 12 September 2006.

87 ‘Documentary films don’t guide my environment policy’, The Australian, 12 September 2006.

88 Downer A, Speech to a symposium organised by the Australian Institute of International Affairs & the Australian Homeland Security Research, 11 October 2006. Source: http://www.foreignminister.gov.au/

speeches/2006/061011_es.html. Al Gore visited Australia in October 2006 to promote the film ‘An Inconvenient Truth’, about the consequences of global warming.

89 Macfarlane I, Speech to the 15th Pacific Basin Nuclear Conference, 16 October 2006.

90 Transcript of the Prime Minister The Hon John Howard MP, press conference with The Hon Peter McGauran MP, Minster for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Parliament House, Canberra, 17 October 2006.

91 Louw, op.cit., p. 207.

92 Warren M, ‘Nuclear plants in a decade’, The Australian, 17 October 2006.

93 ABC News Online, ‘Nuclear debate a diversionary tactic: ALP’, 17 October 2006. Accessed: http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200610/s1766287.htm

94 ‘$125M Towards a Lower Emission Future’, joint media release, Treasurer & The Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources, 25 October 2006. Accessed: http://minister.industry.gov.au/index.cfm?event=object.showContent&objectID=7CEB92AC-E9AA-9CC1-1B8D4EC6D15F0D4B

95 Trent & Friedenberg, op.cit., p. 82.

96 Rollins A, ‘Call to put more energy into renewables’, Australian Financial Review, 15 August 2006.

Frew W, ‘It’s an ill wind’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 May 2006.

97 Transcript of the Prime Minister The Hon John Howard MP, press conference with The Hon Peter McGauran MP, Minster for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Parliament House, Canberra, 17 October 2006.

98 Wilson N & Salusinszky I, ‘Beazley to win on uranium’, The Australian, 26 July 2006.

99 Transcript of the Prime Minister The Hon John Howard MP, press conference, Parliament House, Canberra, 6 June 2006.

100 Bennett W in Louw, op.cit., p. 257.

101 Stanton op.cit.

102 Australian Government, Uranium mining, processing and nuclear energy – opportunities for Australia, Report to the Prime Minister by the Uranium Mining, Processing and Nuclear Energy Review Taskforce, December 2006. Accessed: http://www.dpmc.gov.au/umpner/docs/nuclear_report.pdf

103 ibid, p. 5.

104 ‘Ziggy Switkowski discussed new nuclear report’, Lateline, ABCTV, 21 November 2006. Source: http://www.abc.net.au/

lateline/content/2006/s1794281.htm.

105 Australian Government, op.cit., p. 13.

106 Peatling S, ‘Build 25 nuclear reactors’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 November 2006.

107 Australian Government, Report of the Task Group on Emissions Trading, May 2007, p. 13. Source: http://www.dpmc.gov.au/publications/

emissions/docs/emissions_trading_report.pdf.

108 Australian Government, op.cit., p. 137.

109 Howard J, Media Release, ‘Uranium Mining and Nuclear Energy: A Way Forward for Australia’, 28 April 2007. Source: http://www.pm.gov.au/media/Release/

2007/Media_Release24284.cfm.

110 ibid.

111 Australian Government, op.cit., p. 13.

112 ABC News Online, ‘MacFarlane outlines Govt’s nuclear industry plans’, 28 April 2007. Accessed: http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/200704/s1908836.htm

113 Australian Uranium Association, ‘Australian’s Support Uranium Mining’, 14 May 2007. Accessed: http://aua.greenbanana.com.au/page.php?pid=14&category=1

114 Wilkinson M, ‘Power for the people’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 May 2007.

115 Wilkinson M, ‘$23m ad blitz to save planet – and the PM’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 May 2007.

116 Stanton, op.cit.

117 Althusser L, Lenin and philosophy, and other essays. Translated from the French by Ben Brewster. New York, Monthly Review Press, 1972.