8

Employees’ views on quality

Introduction

The results from a national survey of almost 600 long day care staff, carried out by the Australia Institute in late 2005, show that in most cases staff believe that the quality of care offered in their centre is quite high.

However, when the results are reported by provider type, consistent patterns become evident. Across a range of aspects of quality care, corporate chain childcare centres appear to provide poorer quality care than community-based and independent private childcare centres.

The staff survey included questions about:

- time to develop relationships with individual children

- programming to accommodate children’s individual needs and interests

- the variety of the equipment provided

- the quality and quantity of the food provided

- the staff-to-child ratios

- whether the respondent would send their own child, aged under two, to the centre they were employed at, or one offering comparable quality of care.

Why survey long day care staff?

Long day care is the dominant type of formal care for Australian children aged under five

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, in 2005, a total of almost 303 000 Australian children aged under five attended long day care. The proportion of children attending long day care rises by age group. In 2005, long day care centres provided care for: 155

- 4.5 per cent of babies aged under one

- 21 per cent of one year old children

- almost 30 per cent of two year old children

- almost 38 per cent of three year old children

- almost 28 cent of four year old children (ABS 2006, p. 14).1

Of all children aged under five, just over 24 per cent attend long day care for some proportion of the week – almost one in every four children (ABS 2006, p. 14).

Most children do not attend long day care full time. In 2004, only 10 per cent of children attended for 40 hours a week or more, and 24 per cent attended for less than 10 hours a week. The remaining 66 per cent attended between 10 and 39 hours per week (FACS 2004, pp. 33, 55).

The trend over time is for an increasing proportion of young children to attend long day care

During the period 1999 to 2005, the proportion of young children attending long day care rose in all of the above age groups, and the total number of children attending rose almost 41 per cent (ABS 2000, p. 12; ABS 2006, p. 14).

As the demand for workforce participation of parents increases due to demographic change, the pressure to place young children in long day care is likely to continue to increase.

The provision of long day care has undergone rapid change in the last five years

Prior to 2001, almost all long day care in Australia was provided by community-based (not-for-profit) or independent private (small owner operator) centres. In the last five years, however, corporate childcare chains have expanded rapidly into long day care

156provision. Corporate childcare chains are listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX), and as such, are subject to governance structures that legally oblige the directors of the corporation to act in the best interests of the company – which roughly equates to maximising the financial value of the entity.

Two of the corporate childcare chains which have listed on the ASX since 2001 currently operate in Australia. ABC Learning Centres Limited (hereafter referred to as ABC Learning) first incorporated as a public company in 1997, listed on the stock exchange in 2001, and took over its major rival Peppercorn in 2004 (Fraser 2005), another smaller corporate chain, Kids Campus Limited, in March 2006 (Fraser 2006), and the remaining large corporate chain, Hutchison’s Child Care Services, in October 2006 (ACCC 2006). Childs Family Kindergartens, a small chain, incorporated as a public company in 2002 and then listed on the stock exchange in 2005 (ASIC 2006).2

The federal government does not report on corporate chains as a separate category of childcare centres, but the available information suggests that in early 2006 approximately 57 700 long day care places were provided by the three main corporate chains then operating.3 This was close to 25 per cent of all long day care places in Australia.4

157

Critics say the child care quality accreditation process has serious limitations

The federal government established the National Childcare Accreditation Council (NCAC) in 1993 to administer an accreditation system that aims to continuously improve the quality of child care (NCAC 2006). Although most agree that the accreditation system has improved the quality of care offered to children, it nonetheless has some significant limitations, both structural and procedural.

The national accreditation framework is structurally limited in that it is silent on a number of matters that research tells us are crucial contributors to high quality care. Staff-to-child ratios, which are set by the state and territory governments, are in most cases well below internationally recommended levels. Staff turnover is very high, with around 25 per cent of staff leaving the industry each year, and almost a quarter of long day care staff hold no formal qualifications relevant to child care (AIHW 2005, p. 417). Accreditation cannot reflect any of these concerns.158

The process by which accreditation is carried out also suffers from a number of limitations.

Until very recently, the main criticism of the accreditation process was that there were no random inspections or ‘spot-checks’. Centres usually had several months advance warning of accreditation, so it was hardly surprising that most of them put on a good show for the validator on the day. In April 2006, the Federal Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs made a commitment to introduce spot-checks for the quality of care provided by a centre (Farouque 2006). This appears to be a step in the right direction but it may yet falter as a result of other procedural limitations, which appear to continue to apply. These include the fact that centres do not have to pass all 33 principles (of quality care) to be accredited and the fact that a lenient attitude is taken to centres that don’t meet the NCAC requirements.

Persistent media reports about poor quality care

Consistent with the alleged shortcomings of the national accreditation process, ‘horror stories’ about poor quality long day care centres regularly appear in the print media, as well as in radio and television programs.

Long day care staff are a relatively reliable source of information about quality

We could have surveyed parents of children enrolled in long day care, but parents often have only a limited capacity to gauge the standard of care provided at childcare centres. Even in those cases where parents can spend significant time in the centre in order to assess the quality of care offered, there are a number of other factors that can make it difficult for them. These include:

- staff may change their behaviour in the presence of parents

- parents may not have a centre of high quality for comparison

- parents simply may not be able to admit that they have chosen an inappropriate placement for their child 159(Goodfellow 2005, p. 60, citing Cost, Quality and Child Outcomes Study Team 1995; Cryer and Burchinal 1997; Dahlberg et al. 1999).

Moreover, in 2004, 76 per cent of long day care staff either held a relevant qualification or were studying for one (AIHW 2005, p. 417). Formal training in child development should assist them to judge what constitutes quality care.

The absence of the voice of long day care staff in the public debate

As far as we know, the 2005 Australia Institute survey was the first national survey of long day care staff focusing specifically on their perceptions of the quality of care offered in their centre.

How was the survey carried out?

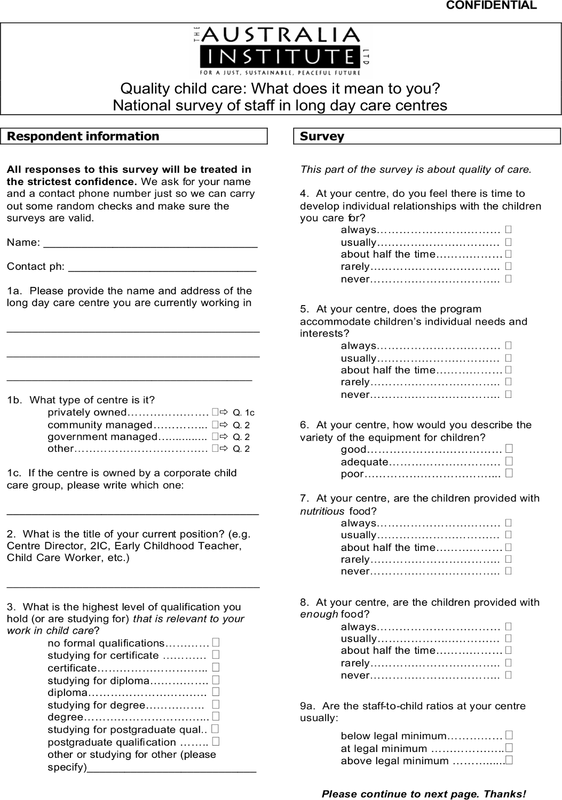

In consultation with childcare experts, and keeping in mind the various state regulations and the national accreditation system which currently govern the provision of child care, we developed a questionnaire for staff working in long day care centres around Australia (see p. 177–180).

Questionnaires were sent to a stratified random sample of 482 long day care centres across Australia (approximately 10 per cent of centres Australia wide). Researchers made follow-up telephone calls to centres surveyed in order to answer any questions from childcare staff about the questionnaire. Valid responses were received from 217 centres (almost 45 per cent of those surveyed and almost five per cent of centres Australia wide).

The 578 valid responses received accounted for approximately one per cent of long day care staff Australia-wide (FACS 2004, pp. 45, 65).5 These responses were tested for sample bias, with the

160following results. Respondents were highly representative of the total Australian population of long day care workers in terms of geographic distribution (by state). They were adequately representative in terms of centre type (community-based, independent private, or corporate chain) and in terms of qualifications held. However, proportionally respondents had more experience working in long day care centres than did the total population of long day care staff in Australia. That the survey attracted a high proportion of experienced respondents is probably due to the fact that staff who have a long-term commitment to child care as a profession are those who are more likely to complete and return a voluntary questionnaire.

There was also potential for the responses we received to be biased due to the possibility that directors of poor quality centres may have failed to pass the questionnaires on to staff, whether for their own reasons, or because they were told not to do so by managers higher up in the corporate structure. For example, during the follow-up telephone calls made to centres after the questionnaires had been mailed out, a staff member at one corporate chain centre reported to us that staff had been told not to fill out the questionnaires by the corporation’s state office. At a couple of other corporate chain centres, staff said that they had asked higher levels of management if they could fill the questionnaires out, and at the time we spoke to them, they were still waiting for a response.

The results of an independent sample of questionnaires sent to Children’s Services students at TAFE colleges showed that long day care staff surveyed by this means assessed their centres as providing slightly lower quality of care than those surveyed by direct mail-out to centre directors. This difference may have resulted from directors of poor quality centres failing to pass the questionnaires onto their staff. If anything, then, survey results may underestimate the quality problems in long day care centres.

In our judgement, the results of the 2005 survey provide a reasonably accurate reflection of staff perceptions of the quality of care provided in long day care centres around Australia.161

Survey results by question

The results of the seven questions most directly related to quality of care are reported below (a full report on the survey is available in Rush 2006). The survey data is presented in table form, for the purposes of detailed comparisons.

Note that the number of respondents changes slightly from question to question because of the 578 valid respondents, some did not answer some questions, and where a respondent ticked in between the available options, their response was coded invalid. The number of respondents reported on in each table is reported as a note to each table, with responses from community-based, independent private and corporate chain centres shown in parentheses. Where applicable, we have tested whether the responses for the corporate chains and independent private centres differ significantly (at the 95 per cent level) from the responses for community-based centres. Where the difference is significant, it is marked with an asterisk (*).

Quotations from respondents are used to illustrate the data (these quotations were drawn from responses to the open-ended questions in the survey). These are identified by centre type and by state in parentheses immediately following the quotation.

At your centre, do you feel there is time to develop individual relationships with the children you care for? Always/Usually/About half the time/Rarely/Never

The results are shown in Table 8.1.

We would expect that in high quality child care, staff would say that they ‘always’ or ‘usually’ had time to develop individual relationships with the children they cared for. Individual relationships between carers and the children are extremely important, because they promote secure attachment, reduce children’s stress and aid childhood development (NSCDC 2004). Long day care staff recognise the importance of developing these individual relationships.

[I would like] more time for staff to spend with individuals, as well as [children with] special needs… (Corporate chain, NSW). 162

[I would like] less paperwork, more one-on-one time with children (Independent private, NSW).

The responses to this question about the development of relationships with individual children suggest one of the biggest differences between the different centre types that provide long day care in Australia. A significantly lower proportion of respondents from corporate chains said they ‘always’ had time to develop individual relationships with the children they cared for than from community-based or independent private centres (25 per cent compared with 54 and 49 per cent respectively).

Table 8.1 Staff have time to develop relationships with individual children, staff perceptions by centre type

| Centre type | % of respondents | ||||

| Always | Usually | About half the time | Rarely | Total | |

| Community-based | 54 | 36 | 8 | 1 | 99 |

| Independent private | 49 | 39 | 11 | 2 | 101 |

| Corporate chain | 25* | 48* | 25* | 3 | 101 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

* Percentages marked with an asterisk are significantly different at the 95 per cent level from the figure for community-based centres. n = 570 (Community-based 226, Independent private 243, Corporate chain 101)

At your centre, does the program accommodate children’s individual needs and interests? Always/Usually/About half the time/Rarely/Never

The results are shown in Table 8.2.

We would expect that in high quality child care, staff would say that the centre program ‘always’ or ‘usually’ accommodates children’s individual needs and interests. It is now widely recognised that high quality programs in early childhood include ‘child-initiative and 163involvement’ to a significant degree (Bennett 2004, p. 11; see also Shonkoff and Phillips 2000, p. 315; NSCDC 2004, p. 1).

Corporate chain centres had a lower percentage of respondents who said their centre program ‘always’ accommodated children’s individual needs and interests.

No one to one time. Outside ‘til 11.00 am then back outdoors at 1.30 pm ‘til 5–6 pm. Sad kids but parents are desperate and director glosses everything over (Corporate chain, NSW).

[I would like] less need for group supervision and more expansion of play in small/individual groups (Independent private, Qld).

Table 8.2 Centre program accommodates children’s individual needs and interests, staff perceptions by centre type

| Centre type | % of respondents | ||||

| Always | Usually | About half the time | Rarely | Total | |

| Community-based | 68 | 29 | 2 | 1 | 100 |

| Independent private | 66 | 28 | 6 | 0 | 100 |

| Corporate chain | 54* | 37 | 9* | 1 | 101 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

* Percentages marked with an asterisk are significantly different at the 95 per cent level from the figure for community-based centres. n = 570 (Community-based 226, Independent private 243, Corporate chain 101)

At your centre, how would you describe the variety of the equipment for children? Good/Adequate/Poor

The results are shown in Table 8.3.

We would expect that in high quality child care, staff would say that the variety of equipment provided for the children was ‘good’, or at 164least ‘adequate’. Such variety is important for staff to be able to deliver a varied and balanced program for the children.

It is often assumed that corporate chain centres bring financial capital to the childcare industry (see for example Romeril 2004, p. 4). We therefore expected that responses to this question would reflect this assumption, and that the data would reveal that corporate chain centres provide better equipment for the children than other centre types. However, only 34 per cent of corporate chain staff said the variety of equipment provided at their centre was ‘good’, compared with 66 per cent of staff from communitybased centres.

[T]he grounds are dismal, and outside is such a small area (Corporate chain, Qld).

I don’t think my centre provides high quality care due to low budget, unqualified staff and poor equipment (Corporate chain, Qld).

Table 8.3 Centre provides a variety of equipment for children, staff perceptions by centre type

| Centre type | % of respondents | |||

| Good | Adequate | Poor | Total | |

| Community-based | 66 | 29 | 5 | 100 |

| Independent private | 59 | 35 | 6 | 100 |

| Corporate chain | 34* | 54* | 12* | 100 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

* Percentages marked with an asterisk are significantly different at the 95 per cent level from the figure for community-based centres. n = 567 (Community-based 226, Independent private 239, Corporate chain 102)

Results for the next two questions (about the quality and quantity of food provided to children) must be interpreted with caution. At some centres, the children bring food from home, and this option was not available on the questionnaire. However, 85 respondents (almost 15 per cent of valid responses) wrote on the questionnaire ‘parents provide food’ or ‘children bring own lunch’. These responses have been removed from 165the figures given for the next two questions, since they do not reflect anything about the quality of the centre. However, we do not know how many respondents answered with respect to the food provided by parents, but failed to write this on the questionnaire.

At your centre, are the children provided with nutritious food? Always/Usually/About half the time/Rarely/Never

The results are shown in Table 8.4.

Respondents from corporate chain centres were significantly less likely than independent private and community-based centre respondents to say that their centre always provided nutritious food (46 per cent compared with 73 and 74 per cent respectively). Moreover, 20 per cent of respondents from corporate chains said that nutritious food was only provided ‘about half of the time’, compared with five per cent of independent private centre respondents and four per cent of community-based centre respondents.

[One change I would make is to] provide more … nutritious meals for the children which are varied, and enough food is offered including alternatives (Independent private, NT).

Table 8.4 Centre provides nutritious food for children, staff perceptions by centre type

| Centre type | % of respondents | |||

| Always | Usually | About half the time | Total | |

| Community-based | 74 | 22 | 4 | 100 |

| Independent private | 73 | 22 | 5 | 100 |

| Corporate chain | 46* | 34 | 20* | 100 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

* Percentages marked with an asterisk are significantly different at the 95 per cent level from the figure for community-based centres. n = 488 (Community-based 195, Independent private 211, Corporate chain 82)166

At your centre, are the children provided with enough food? Always/Usually/About half the time/Rarely/Never

The results are shown in Table 8.5.

The responses show a similar pattern to the previous question, with the corporate chains scoring markedly worse. Staff at communitybased centres are much more likely than staff at corporate chain centres to say that children are always provided with enough food (80 per cent as opposed to 54 per cent). At the same time, one in 10 respondents from corporate chains said that children receive enough food only about half the time.

[I would not send my child to the centre I work at due to] lack of food (not enough allocated per child) and untidiness (centre never cleaned properly due to lack of staff) and lack of good quality equipment (Independent private, Qld).

Table 8.5 Centre provides enough food for children, staff perceptions by centre type

| Centre type | % of respondents | ||||

| Always | Usually | About half the time | Rarely | Total | |

| Community-based | 80 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 100 |

| Independent private | 75 | 20 | 4 | 1 | 100 |

| Corporate chain | 54* | 36* | 10* | 0 | 100 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

* Percentages marked with an asterisk are significantly different at the 95 per cent level from the figure for community-based centres. n = 487 (Community-based 195, Independent private 211, Corporate chain 81)

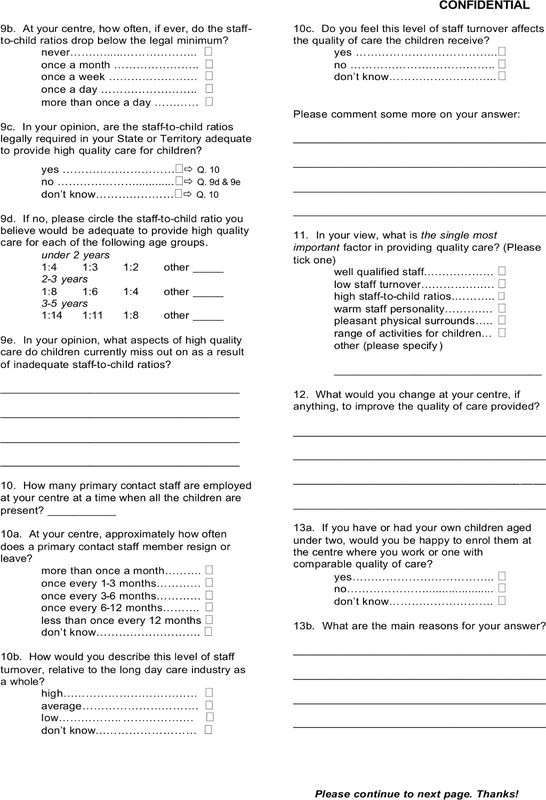

Are the staff-to-child ratios at your centre usually … Below legal minimum/At legal minimum/Above legal minimum.

The results are shown in Table 8.6.

167The responses indicate that centres rarely operate below the legal minimum staff-to-child ratio as their usual practice, and this holds true for all three types of centre. However, as the table shows, community-based and independent private centres are much more likely to operate with more than the legally required number of staff.

Table 8.6 Standard staff-to-child ratios, staff perceptions by centre type

| Centre type | % of respondents | |||

| Below legal minimum | At legal minimum | Above legal minimum | Total | |

| Community-based | 4 | 57 | 40 | 101 |

| Independent private | 2 | 62 | 37 | 101 |

| Corporate chain | 5 | 81* | 14* | 100 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

* Percentages marked with an asterisk are significantly different at the 95 per cent level from the figure for community-based centres. n = 555 (Community-based 222, Independent private 234, Corporate chain 99)

If you have or had your own children aged under two, would you be happy to enrol them at the centre where you work or one with comparable quality of care? Why/Why not?

The results are shown in Table 8.7.

We asked this question because if a worker would not place their own young child in a centre of comparable quality to the one where they work, and they specify quality concerns as the reason for this, then this raises serious questions about the overall quality of care offered by the centre.

Overall, the responses indicate that the majority of respondents would be happy to enrol their own child aged under two in the centre where they worked. Indeed, many staff described the overall quality of care at their centre in very positive terms.

The staff are warm and friendly. The aesthetic of the centre is colourful and welcoming and toys are 168rotated well. Staff work well together (Independent private, ACT).

The staff genuinely care for all the children and families equally. They put the children and their beliefs, likes and interests first (Community-based, NSW).

Table 8.7 Responses to ‘If you have or had your own children aged under two, would you be happy to enrol them at the centre where you work or one with comparable quality of care’, by centre type

| Centre type | % of respondents | ||||

| Yes | No – quality concerns | No – other reasons | Don’t know | Total | |

| Community-based | 80 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 100 |

| Independent private | 75 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 100 |

| Corporate chain | 69* | 21* | 4 | 6 | 100 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

* Percentages marked with an asterisk are significantly different at the 95 per cent level from the figure for community-based centres. n = 556 (Community-based 218, Independent private 238, Corporate chain 100)

However, despite the fact that all respondents worked at accredited centres, a minority said that they would not be happy to enrol their own child aged under two in the centre where they worked, due to quality concerns. This minority was far more significant in corporate chain centres: 21 per cent said they would not send their own child to the centre where they worked, or one with comparable quality of care, because they had concerns about the quality of care provided at their centre, compared with only four and six per cent of community-based and independent private centre respondents respectively.

Those respondents who would not be happy to send their own child to the centre where they worked because they had quality concerns cited a number of different reasons. Some respondents 169made comments about inadequate state regulations, in particular what they felt were unacceptably low staff-to-child ratios.

As good as it is, in the under 2s the children are managed and the good quality care that I want for my baby is just not possible – but the staff do their best (Community-based, Vic).

I believe under 2 with these ratios is unfair (Corporate chain, NSW).

Other respondents commented on matters that fall more within the responsibility of the national accreditation system. Some felt that routines within the centre, including staff cleaning and paperwork responsibilities, did not allow for adequate time with children.

Not enough time spent with children, staff always cleaning or doing paperwork (Corporate chain, NSW).

Others commented on the lack of resources necessary to provide a good quality program for children.

Not enough resources for children – most toys have been donated or bought by staff (Corporate chain, Qld).

Place dirty, broken resources (Corporate chain, Vic).

Many commented on staffing issues. Such comments implicitly point to the need for government policy to address the undersupply of quality childcare staff, which is directly linked to the extremely high rates at which childcare staff leave the industry: in the three years prior to 2004, approximately 25 per cent of long day care staff left the industry each year (AIHW 2005, p. 100).

High staff turnover, low staff morale, traineeship-trained staff … (Corporate chain, Vic).

… immaturity and lack of experience of staff (not lack of qualifications) (Community-based, Vic).

Some respondents articulated concerns that appeared to be specific to corporate chains (similar comments were not received for the other centre types).170

[C]are … is adequate, but the child’s development is secondary to keeping up appearances … The director is primarily a money collector and whip cracker … (Corporate chain, NSW).

[Corporate chain] took over and now it’s a money making business and not a family one. Too much paperwork means not enough time spent with children (Corporate chain, Vic).

Others were concerned about the rigidity of the centre routines, in comments that appear to confirm Goodfellow’s identification of a ‘business orientation’ that focuses on ‘efficiency and production of measurable outputs’ (Goodfellow 2005, p. 54).

… regimented and rigid programs where the children have to fit in with the centre program style whether it suits their personality or not! (Corporate chain, Qld)

[Centre] does not meet emotional needs, [children must] follow centre’s routine (Corporate chain, NSW).

Importance of results

The results from the survey are of concern given that at present approximately 25 per cent of children attending long day care attend a corporate chain centre. Of all Australian children under five, this amounts to approximately six per cent, or about one in every 20 Australian children aged under five.

The trend of corporate chain expansion looks set to continue, with the only apparent limit being the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) requirement that one chain cannot own more than 40 per cent of the centres in a given area. However, it is possible that between them, three different chains could own all of the centres in a given area without contravening this requirement.

What might be done to improve the quality of care?

The responses of long day care staff to the Australia Institute survey are consistent with the following policy recommendations.171

1. Improve staff-to-child ratios

In most states in Australia these are below the levels recommended by experts, and a majority of childcare staff surveyed felt they were inadequate to provide quality care.

1a. Take steps to maintain and increase the supply of qualified and experienced childcare staff

The issue of raising staff-to-child ratios has sometimes been dismissed on the grounds that in the context of existing childcare staff shortages, to raise staff-to-child ratios would cause a loss of childcare places (Pryor 2006). To minimise this risk, steps should be taken both to reduce the high numbers of staff leaving the industry (see AIHW 2005, p. 100), and to increase the supply of qualified childcare workers.

Many of the childcare staff we surveyed made plain their views about problems with pay and conditions, despite the fact that none of our questions were specifically directed at these issues. We therefore repeat the recommendation made by the Child Care Workforce Think Tank in 2003 but rejected by the Coalition government: governments must ‘address the costs of improving the pay and conditions of the early childhood workforce while ensuring that the cost to families is affordable’ (FACS 2003, p. 6).

2. Monitor the quality provided by different provider types

The survey results imply a need for the three different types of long day care provider to be reported on separately in government data collection if such reporting is to accurately reflect the diversity of care provided by the industry. At present, the federal government, through FACS, monitors long day care centres as either being ‘community based’ or ‘private for-profit’. Survey results suggest that the current ‘private for-profit’ category might best be separated into ‘corporate chain’ and ‘independent private’ for data collection and reporting purposes.

NCAC is in the ideal position to undertake comparative quality monitoring, but at present, it does not hold information on centre provider types. There is therefore no way for it to report on the relative quality outcomes, as assessed during the accreditation 172process, of the three different types of provider present in the long day care industry. If NCAC could be given access to the relevant data, it would be a relatively simple matter for them to report on quality provision by provider type as an additional outcome of the accreditation process.

3. Fund the establishment of new community-based centres

Survey results suggest that further unchecked expansion of corporate chains will risk lowering the overall level of the quality of care at long day care centres in Australia. To avoid this, the federal government could increase funding for the establishment of community-based centres, especially in areas of demonstrated work-related need. This would be consistent with government intentions to promote both the workplace participation of parents and parental choice.

173

174

174

175

175

176

176

177

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2000, Child Care, Australia, June 1999, cat. no. 4402.0, ABS, Canberra.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Child care, Australia, June 2005, cat. no. 4402.0, ABS, Canberra.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2003, Australia’s Welfare 2003, AIHW, Canberra.

ASIC 2006, Australian Securities and Investment Commission website, Search of ‘National Names Index’, viewed 8 March 2006, www.asics.gov.au.

Bennett, J 2004, Curriculum issues in national policy making, presentation to the European Early Childhood Education Research Association, OECD, Paris.

CFK 2007, Childs Family Kindergartens website, corporate page, viewed 12 February 2007, www.cfk.com.au/aboutus_page.htm.

CFK 2006, Childs Family Kindergartens website, corporate page, viewed 8 March 2006, www.cfk.com.au/aboutus_page.htm.

Family and Community Services 2003, Australian Government Report on the April 2003 Child Care Workforce Think Tank, Department of Family and Community Services, Canberra.

Family and Community Services 2004, 2004 Census of Child Care Services Department of Family and Community Services, Canberra, viewed 25 March 2006 www.facs.gov.au/internet/facsinternet.nsf/childcare/04_census.htm.

Farouque, F 2006, ‘Workers give chain child-care centres the thumbs-down’ The Age, 1 April, p. 3.178

Fraser, A 2005. Childcare magnate in $218m US coup. The Australian, 17 November, p. 5.

Fraser, A 2006, ‘ABC marks up centres in Campus bid’, The Australian, 16 March, p. 23.

Hutchinson’s Child Care Services 2006, corporate page, viewed 21 February 2006, www.hutchisonschildcare.com.au/sites/hccs/Default.asp?Page=23 KDS 2006.

Kids Campus website, Company Profile page, viewed 25 March 2006, www.kidscampus.com.au/view.asp?a=1066&s=265.

Marriner, C 2006, ‘Child-care giant set to expand’, The Sydney Morning Herald, November 30.

NCAC 2006, NCAC website, History of the National Childcare Accreditation Council, viewed 9 March 2006, www.ncac.gov.au/about_ncac/history.htm.

NSCDC 2004, ‘Young children develop in an environment of relationships’, National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, working paper no. 1, viewed 25 March 2006, www.developingchild.net/reports.shtml.

Pryor, L 2006, ‘Caring for kids: the dollar beats dazzle’, The Sydney Morning Herald, March 13.

Romeril, B 2004, ‘Community ownership and quality: How do you know if a child care service is good quality?’, presentation to Glen Eira Residents Action Group forum, 1 June.

Rush, E 2006, Child care quality in Australia, The Australia Institute, Canberra.

Shonkoff, J & Phillips, D 2000, From Neurons to Neighbourhoods: The science of early childhood development, Academy Press, Washington.

1 Attendance at preschool instead of long day care is the probable reason for a decline in attendance at long day care from age 3 to age 4. Many 5-year-old children are attending school and are no longer in long day care.

2 Note that this paragraph was revised on 12 February 2006 to take into account ABC Learning Centres’ completed acquisitions of Kids Campus (17 July 2006) and Hutchison’s Child Care Services (31 October 2006). Note that Childs Family Kindergartens operated only 43 child care centres in metropolitan Sydney as at 12 February 2007, compared with the 930 centres owned by ABC Learning Centres across Australia and New Zealand in November 2006 (CFK 2007; Marriner 2006). The rest of the paper remains the same as presented at the ASSA workshop.

3 The number of child care places provided by ABC Learning is not obvious in the literature published by the company. The figure of approximately 20 per cent of the child care market is usually quoted in reference to ABC Learning (e.g. Fraser 2005), which would equate to approximately 46,000 places (using data in AIHW 2005, p. 416). Adding to this figure the approximately 6,100 places provided by Kids Campus (KDS 2006) in 85 centres, the 5,000 places provided by Hutchison’s Child Care Services (HCCS 2006) in 81 centres, and the approximately 2,600 places provided by Childs Family Kindergartens (CFK 2006) gives approximately 57,700 places provided by corporate chains.

Note that the Childs Family Kindergartens website states that the company ‘owns and operates 37 child care centres in metropolitan Sydney … and cares for over 4,000 children’ (CFK 2006). It is not obvious whether the latter refers to individual children (who may attend part time) or full-time places; if it were the former it would mean that CFK centres average 108 children per centre which is well above the Australia-wide average for private centres of 91 children per centre (FACS 2004, p. 10), and if it were the latter it would mean that CFK centres offer, on average, 108 places per centre, which is well above the averages for Kids Campus and Hutchison’s (averages of 71 and 61 places per centre respectively). Assuming that CFK’s 37 centres operate with an average capacity of 71 places per centre (comparable with Kids Campus) would give approximately 2,600 places in total.

4 Current figures for total long day care places in Australia are not available. The most recent figures are from Centrelink administrative data as at 27 September 2004, and show 229,603 long day care places available Australia wide (figures provided by the Child Care Branch, Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, 10 March 2006).

5 The FACS Child Care Census reports that 29,300 long day care centre staff are employed at the 85 per cent of private long day care centres that responded to the census, so we estimate that a total of 34,470 are employed overall in private long day care centres. The FACS Child Care Census reports that 18,973 long day care centre staff are employed at the 97 per cent of community-based long day care centres that responded to the census, so we estimate that a total of 19,374 are employed overall in community-based long day care centres. Our estimate of the total number of staff employed in long day care in Australia is therefore 53,844.