Chapter 1

Introduction: The Problem Defined

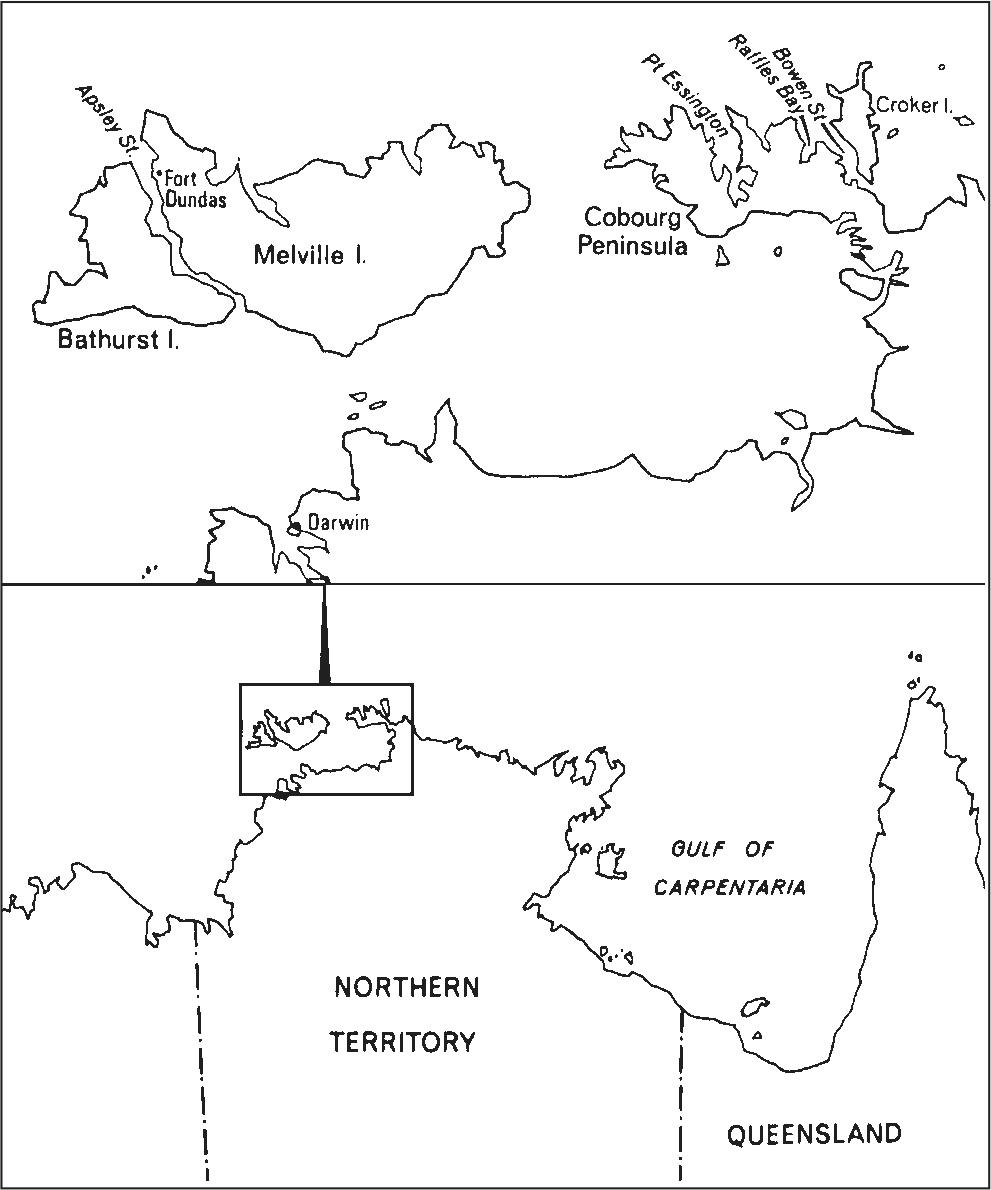

Prior to 1966 no professional enquiry had been made into the potential of archaeology as a technique for historical research in Australia. In that year the possibilities of excavating the remains of the British settlement of Victoria, in Port Essington in tropical northern Australia (Figures 1 and 2) were investigated by me and my supervisor, D.J. Mulvaney. This thesis presents the results of the project which grew from those investigations.

The work was begun in total ignorance of the amount of historical archaeology which had been carried on in the United States of America and also in Canada and with only the vaguest ideas about industrial archaeology in Britain. The latter discipline proved to have less relevance to the Australian situation than the former, and many aspects of the organisation and analysis of the present work reflect the influence of American historical archaeologists. The cultural affinities of the materials recovered were British, however, and research into these was necessarily directed towards Britain. Terminologies in use have been maintained wherever possible and reflect both American and British influences.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Anumber of themes presented themselves as potential lines of enquiry. The first and major objective was to assess the degree to which archaeology, both in fieldwork and laboratory analysis, might be of value in providing new insights and evidence for Australian colonial history. In the immediate situation this meant demonstrating that archaeology might be able to say something beyond the available documents for the history of Port Essington. These documents were known to be available, although in what quantities was still to be ascertained, and documentary research was assumed to be an integral part of the project from the beginning. This led to a further consideration, the degree to which two vastly different kinds of evidence might interact and be integrated into history. From the vantage point of hindsight this has emerged as the major problem confronting not only this project but historical archaeology in general.

Figure 1. Location map showing Port Essington and other places mentioned in the text.

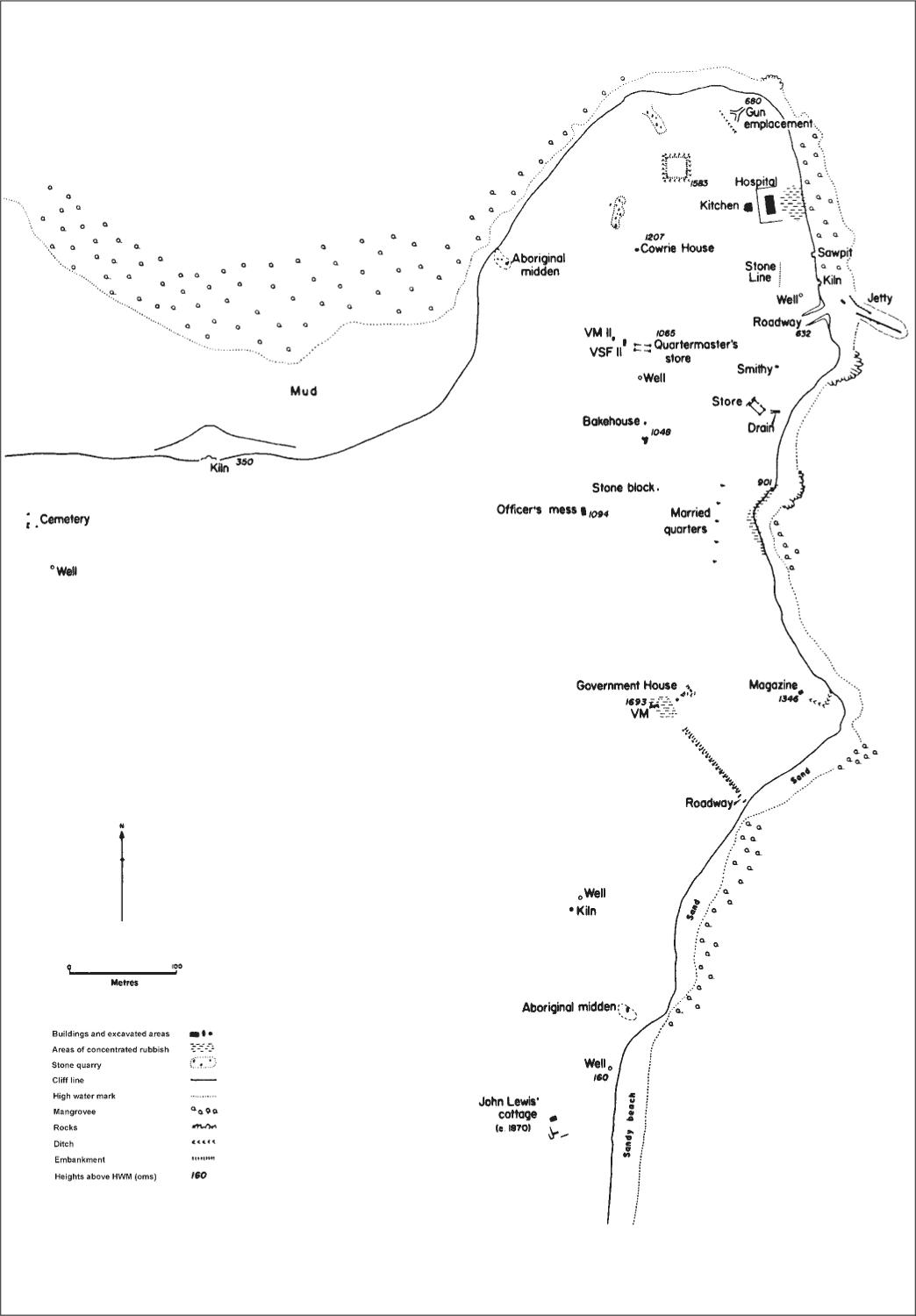

The second aim of the thesis – to begin compiling a well-dated reference collection of mid-nineteenth century artefacts – both influenced and was influenced by the selection of the site. The settlement at Port Essington was made in 1838 and abandoned in 1849. From that time the area has remained almost totally free from contamination by later European occupation. The exception was in the 1870s when cattle ranchers occupied the area for a brief time, but as reference to the site map (Figure 3) shows, this was not in the settlement proper, nor was it of sufficient intensity to disturb the original occupation debris to any noticeable degree. Today the area is a flora and fauna reserve, superintended by a ranger living at Black Point, 24 km from the settlement. Access to the settlement by land requires a major expedition (see below) and the attendant difficulties of sea or air access limit visitors to the settlement to one or two per year.

Thus the site presented an almost unique opportunity to test the potential for the future analysis of historic sites elsewhere in Australia – the excavation of an uncontaminated site of single phase occupation whose occupation dates were known historically, and which was of sufficient duration to provide a meaningful collection of artefacts and architectural information. At the same time the duration of the settlement was not of an extended time range, and it was expected that the artefacts recovered might therefore constitute a type collection for this period of Australian history. This could then be used in the same manner as types anywhere in archaeology, for working from the known to the unknown. Following the first season’s excavations an immediate example of this process was at hand. The Chinese porcelain excavated in the settlement showed similarities with that being excavated in historically undated Macassan (Malayan) trepanging campsites on the Arnhem Land coast, and a comparison of these wares is at present being conducted (Macknight 1969).

Two further areas of consideration presented themselves. The first of these was the possibility of exploring archaeologically for the first time in Australia the culture contact situation between Europeans and Aborigines, not only within the settlement itself, but also in Aboriginal sites in the general area.

The second consideration was that because of the unique possibilities of cross-checking archaeological evidence with historical documents it was thought that archaeology in the recent historical past might be well suited for examining concepts and techniques of fieldwork, analysis and interpretation current in prehistoric archaeological research.

Faced with no knowledge of any theoretical writing in the particular field of historical archaeology, the work was begun with a single basic premise: that the final objective of the fieldwork and analysis was to produce history. In the particular and practical aspect this meant the history of Port Essington constructed from all the available sources. In a more general aspect this meant contributing to the general history of nineteenth century technology and colonial expansion, again using both archaeological and historical data. 2

FIELDWORK

In June 1966 I carried out a preliminary survey, including some exploratory excavation, with the help of John Mulvaney. This had followed three months initial documentary research which yielded contemporary descriptions of the settlement, a large number of contemporary sketches and paintings and the descriptions of a few later visitors to the site. The survey confirmed the wealth of deposit and architectural remains and altogether more than 40 site-units (structures or contained areas within the site) were located, the majority of which could be identified as to function from the illustrations and descriptions available.

I returned to the site for six weeks in August and September of 1966 with a small team. We spent the time mapping, recording architecture and excavating various site-units. Of the six members who comprised the excavation team five were experienced excavators and all were efficient workers. This field season was so productive that the follow-up season in 1967 was limited to three weeks extending the excavations and checking results obtained in the previous year. In addition, short visits were made to two slightly earlier sites in the vicinity, Fort Dundas on Melville Island and Raffles Bay on the Cobourg Peninsula (see Chapter 6). Trial excavations at both these sites proved disappointing and given also the paucity of architectural remains at both, in comparison with Port Essington, it was decided to concentrate efforts on the latter.

A final visit to the site took place in August–September 1968. This was conducted in conjunction with a field exercise controlled by the Northern Command of the Australian Army and the primary purpose of the visit was to carry out conservation of the site. In addition, however, it afforded the opportunity of locating several convalescent stations which had been occupied by the original garrison in various parts of Port Essington. As an example of the difficulty of land access, it took the seven vehicles in the unit six days to reach the settlement from Oenpelli Mission, a distance of less than 160 km.

THE SITE

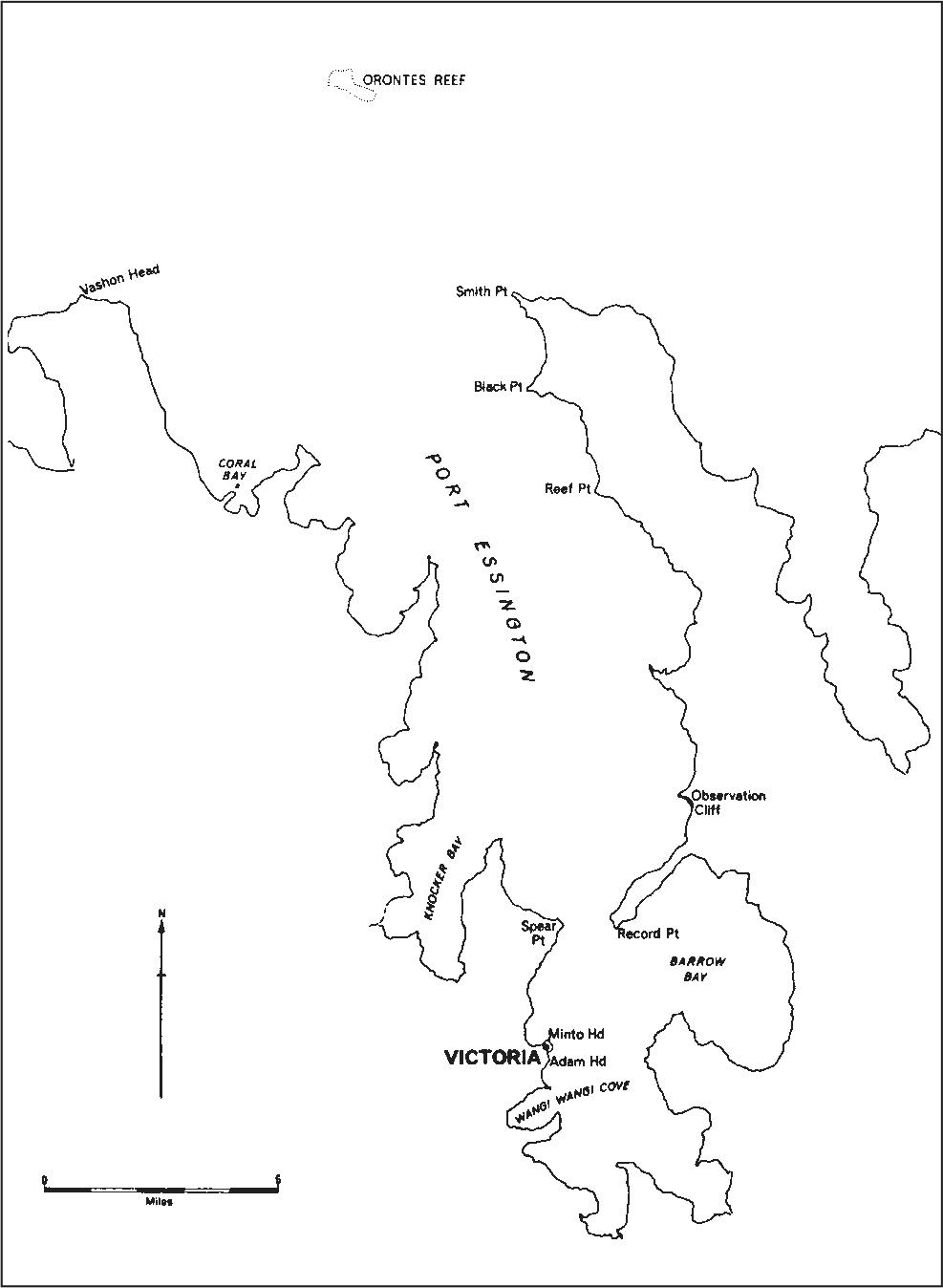

The Cobourg Peninsula is a small peninsula (approximately 1,500 square km in area) jutting into the Arafura Sea at the western end of Arnhem Land (Figures 1 and 2). It is a relatively flat piece of land whose outstanding topographical feature is the number of harbours and inlets which indent its coastline. The largest of these is Port Essington, which has a mouth c. 11 km wide and which extends approximately 32 km to its head. The harbour is divided naturally into inner and outer harbours by a narrow spit of land, Record Point. The shoreline consists for the most part of dunes screened by mangrove mudflats or sandy beaches. In places a low red cliff line reveals the hinterland as open schlerophyll forest with pockets of monsoonal jungle. Being well into the tropical zone the climate of the area is hot and humid. It receives c. 1,250 mm of rain each year, all of which falls in the wet season, October to April.

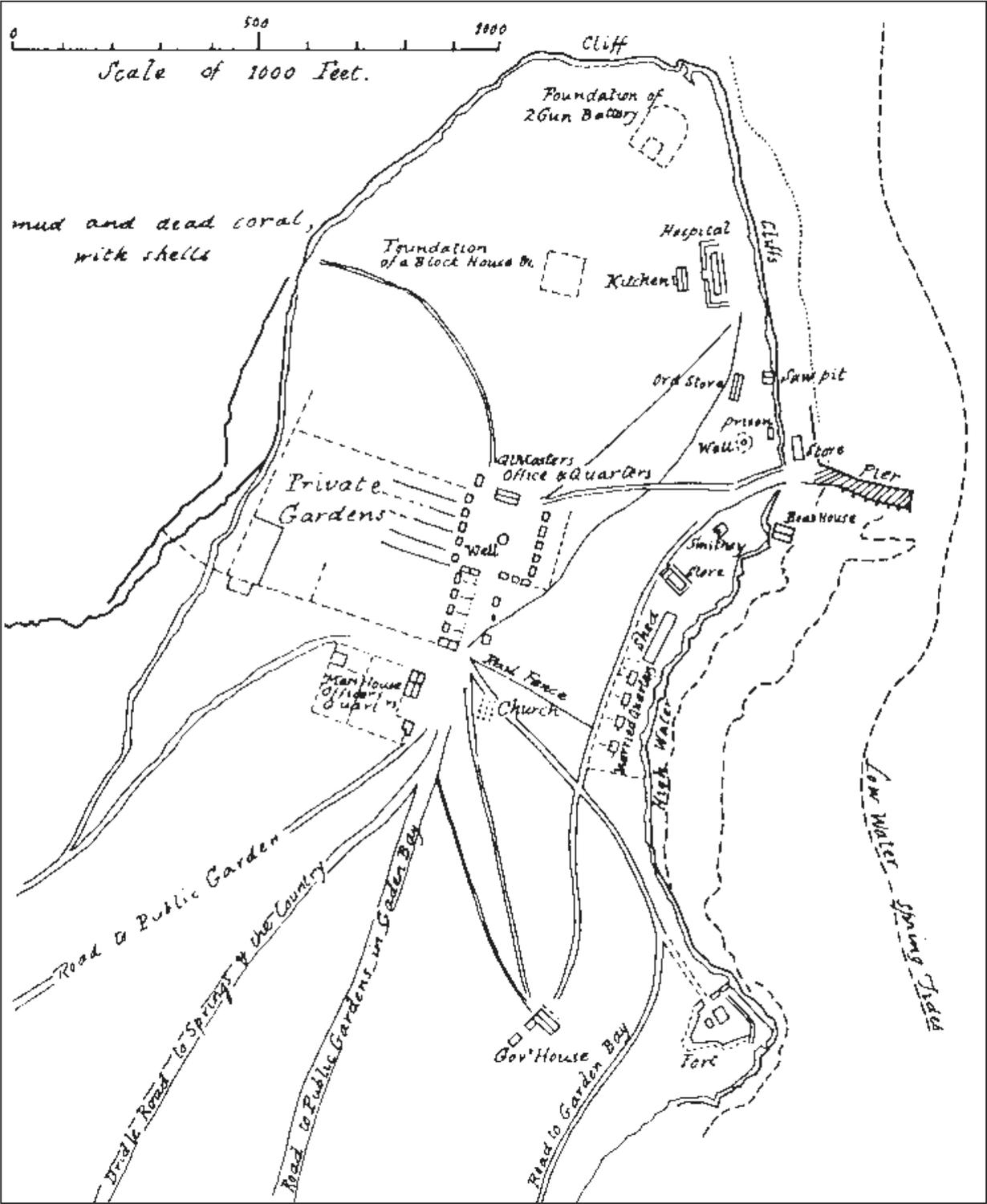

The site of the settlement, which was named Victoria (but universally referred to here and elsewhere as Port Essington), was situated on the western shore of the inner harbour where the white cliff of Adam Head forms a conspicuous landmark, rising about 15 m above the sea, and being possibly the highest point on the harbour shoreline (Figure 3). The settlement was placed on the plateau which extends from Adam Head to Minto Head and covered an area of some 36 hectares. Since its abandonment, the forest has regenerated strongly which made the location and mapping of site-units a difficult process. Between the initial survey and the first season of excavation Peter Spillett (Historical Society of the Northern Territory) supplied me with a contemporary sketch map of the settlement (HRA I xxvi:373), which in general verified the identifications made during the initial survey. This map (Figure 4) showed that the town square was in fact hatchet-shaped and conformed to the similarly shaped patch of monsoonal forest located west of the jetty. There appeared to be no reason why this area should have regenerated in monsoonal growth unless it had been similar vegetation originally, but this proved not to be the case. Excavations under house floors in two separate site-units within this vegetation zone revealed a thin charcoal layer (see Figure 25) containing pieces of charcoal identified as eucalypt (Stocker 1968) that demonstrated that the area contained these trees prior to clearing by fire. The regeneration of monsoonal rather than eucalypt forest is seen as a result of the introduction of shell used as flooring in the huts which bordered the square. Section 4 of Stocker’s report reads: ‘the broken shell material used for the flooring of the houses may be important. Perhaps after the abandonment of the settlement the ring of broken shell floors around the square prevented fire penetration and enabled the monsoon forest to become established. Another possibility which cannot be discounted is that the broken shell material inhibited growth of eucalypt forest species without affecting those of the monsoon forest. Monsoon forest is often on soils derived from shell material but eucalypt forests rarely, if ever, occur on these soils’.

Figure 2. Map of Port Essington showing Victoria and other places mentioned in the text.

The area of the settlement proper is an undulating plateau with the highest points being Adam Head and Minto Head. To the west beyond the square the ground falls gently, terminating in a paperbark (Melaleuca sp.) swamp some 400 m from the settlement, immediately beyond the cemetery. The ground to the south of Adam Head falls sharply to a fine sandy beach where the 1870s cattle ranch was located. 3

Figure 3. Map of Victoria settlement showing archaeological locations discussed in the text.

4

Figure 4. Contemporary map of Victoria settlement drawn in 1847 (HRA I xxvi:373), sometimes referred to as the McArthur map.

EXCAVATIONS

Given the time and resources at my disposal it was not possible to excavate the settlement completely, nor was this desirable, since we were conscious of preserving as much of the archaeological record there as possible. It was felt that since the potential importance of the site was so great, sections of original deposit of all site units should be maintained for future work when theoretical constructs of the discipline and techniques for exploring them were better understood.

It was thus decided not to excavate any site-unit totally, but rather to sample as many site-units as possible, despite deficiencies in this approach. The excavations become, as Dollar (1967:8) pointed out, a statistical sample of a statistical sample, with the attendant problems of generalising from misleading evidence. However, given the potential different nature of these deposits from the prehistoric sites with which we were familiar, we also had to develop appropriate excavation techniques in the field, building on our own immediate experience. More pragmatically we also wished to compare site-units to explore whether concepts as diverse as social class distinctions and technological functions could be determined from the archaeological evidence alone.

Astandard pattern of excavations was developed. The site-units were excavated in metre squares except where a closer horizontal check was thought necessary, in which case the units were reduced. The standard technique was to excavate these squares with trowels until whatever stratigraphy present was recognised. In most site-units stratigraphy was of little importance, being single-phase occupation, but wherever an apparent stratigraphic division occurred, the material was excavated separately, to be integrated or kept distinct at a later date in the laboratory. Once the general nature of deposition was understood, small spades were employed to hasten the excavations. In general excavations were made at right-angles to wall lines, so as to be able to identify builders’ trenches and other architectural features.

All material was passed through 5 mm mesh sieves and immediately bagged for transportation to the laboratory where it was washed and labelled. All architectural sections were drawn in the field and measurements were independently taken for later cross-checking. The site map was drawn with less than a 2% error.

DOCUMENTARY RESOURCES

The major difficulty of my documentary research has been my inability to locate in Australia reliable literature dealing specifically with the technology and products of nineteenth century England. By corresponding with a number of museums and libraries in Britain some information was gained and this correspondence also introduced me to historical archaeology in North America from whence I was able to acquire a number of site reports and other methodological and theoretical papers. Many site reports did not contain sufficient detail for comparisons with my excavations, nor were the methodologies employed sufficiently useful for my work. However they were of great assistance in clarifying my own approach. In the latter part of 1967 1 was fortunate in being able to spend four months in Britain, Canada and the United States, examining museum collections and talking to archaeologists interested in historical archaeology. This proved highly beneficial, not the least in that it enabled me to tap a number of documentary sources unavailable in Australia.