Chapter 2

Excavations and Architecture

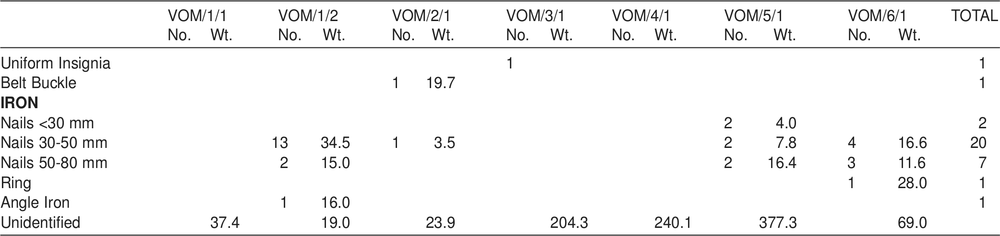

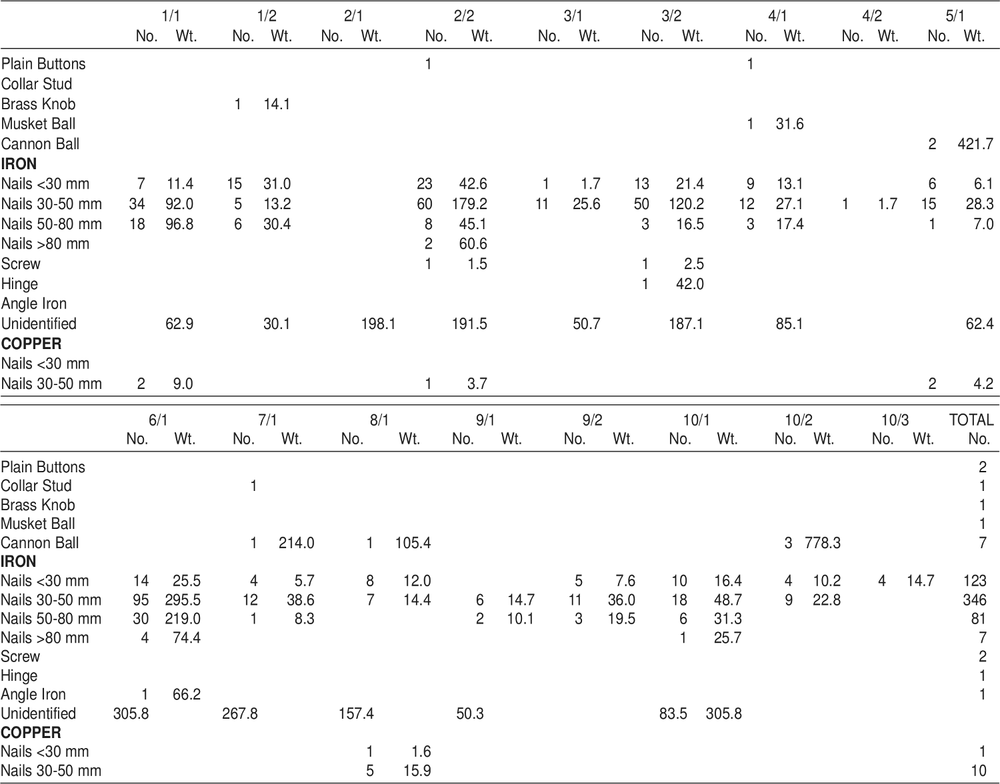

This chapter describes the excavations and architecture of each site-unit. Any relevant discussion is included at this juncture and the finds from each site-unit are recorded in tabulated form at the end of each section; mostly these are not directly referred to in the text. General discussions of the artefacts follow in the subsequent chapters.

Each site-unit has been dealt with separately and has been given a code prefix listed at the beginning of each section. All weights are given in grams, and measurements in metres, or millimetres as appropriate. The glass in the tables in this chapter is divided into three types. Type A includes all pieces thought to be possible Aboriginal artefacts, Type B includes all pieces of identifiable shape and Type C includes all pieces of glass not identifiable as Types A or B (see Chapter 4).

VICTORIA RUBBISH DUMP (Code prefix VM)

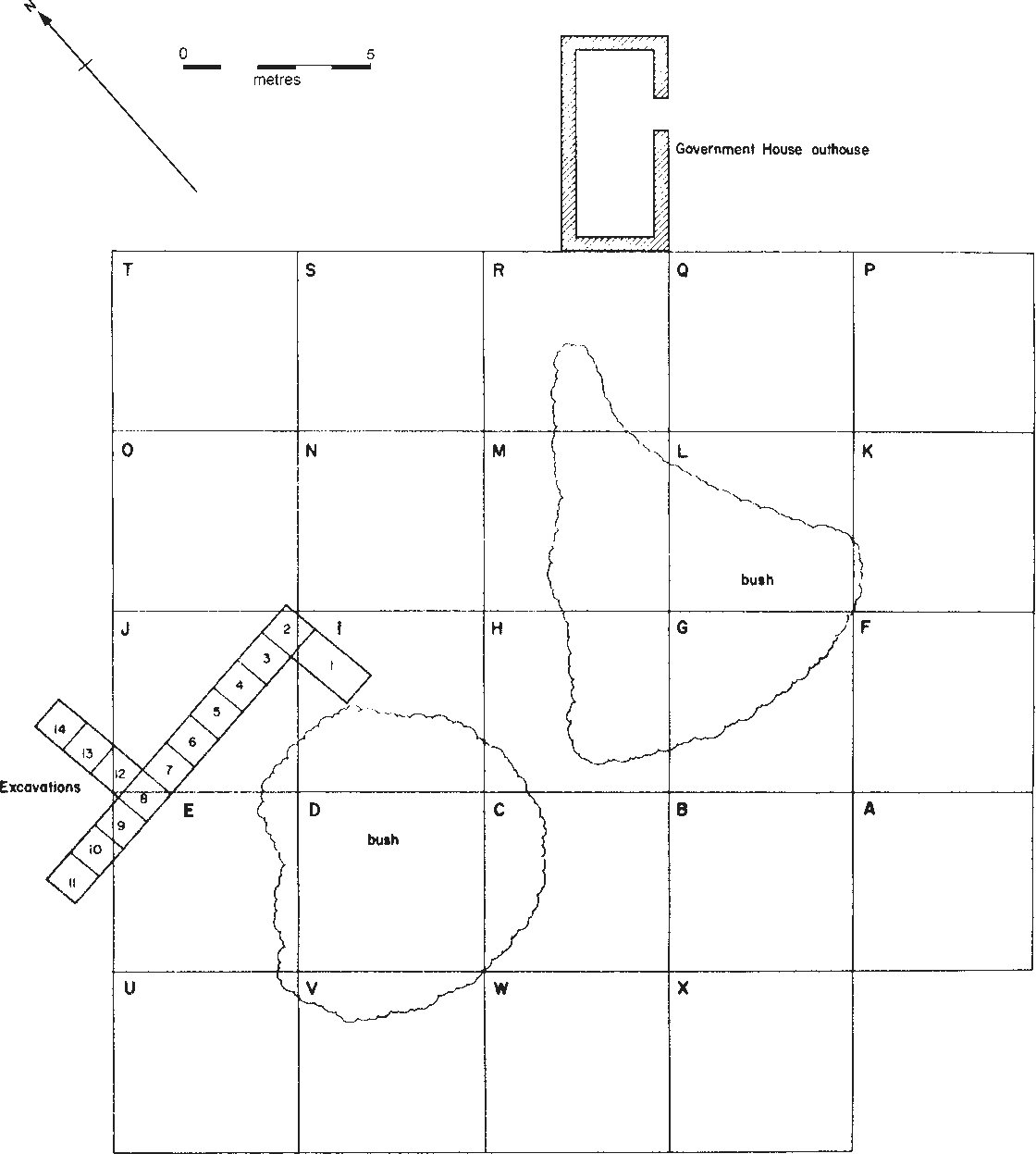

During the initial survey an area was located immediately to the south of the outhouse belonging government house which subsequently proved to be the largest rubbish dump in the settlement. The area was flat and heavily grassed, and was covered with two large clumps of an unidentified green bramble, about 2.5 m in height and particularly thorny. Between these two clumps an animal path had kept the grass down and pieces of glass and pottery were noticed. Since it was almost impossible to delineate the area of rubbish distribution without a thorough clearing of the area, an area twenty metres by twenty-five metres was measured out, taking the animal path as roughly the centre, and this area was cleared to allow a complete surface collection to be made.

VM surface collection

Twenty-five squares, lettered A to T, and each measuring 5 m by 5 m, were completely collected of all cultural material with the exception of a few bricks, and pieces of local ironstone which may have been roughly hewn as a building material. As elsewhere, glass was by far the most common artefact recovered and its distribution gives a good indication of the density of cultural deposit. Most of the area of the heaviest deposit is that covered by the bramble.

The results obtained indicated that the grid had perhaps been set too far to the east. An examination to the west of the grid suggested more deposit, but few actual finds were visible on the surface and it was judged unimportant to extend the grid in that direction. Instead four more squares (U–X) were added to the southern side where another concentration of material was located.

This collection proved to be the most concentrated one found at the settlement. A total of 2,231 pieces of glass and 263 pieces of pottery were recovered, as well as fragments of metal, and an Aboriginal stone implement (a core) in creamy quartzite, a material foreign to the area. As the collection continued it became apparent that even allowing for accidental fracture, some of the glass represented deliberate utilisation by Aborigines.

Because of the density of surface artefacts I decided to excavate this site-unit during the first season to provide the nucleus of the site’s type collection.

VM excavations

The distribution of the surface material suggested that the main concentration was lying roughly along the east-west diagonal of the surface grid and I decided to excavate along this line at the point where the slightly raised ground level promised the maximum depth of deposit. At the same time the trench was situated so as to avoid the bramble areas where the roots would interfere with the excavations.

An initial trench VM/1, measuring 2 m by 1 m, was excavated in two spits, the first to a uniform depth of 100 mm, the second to sterile soil, at an average depth of 160 mm. This trench produced an inordinate amount of cultural material, particularly glass. Since no difference could be ascertained between the upper and lower spits, and since the main object of the excavation was to obtain as large a sample of artefacts as possible, it was decided to abandon the stratigraphic differentiation to increase the speed of the excavation, but at the same time to maintain some horizontal control by excavating metre squares. Subsequently in the laboratory the two stratigraphic units of VM/1 were amalgamated for analysis.

Figure 5. Rubbish dump behind Government House showing foundations of its outhouse, the area of its surface collection and the location of excavation VM.

The excavations were continued towards the west in a line of adjoining metre squares (Figure 5). Squares VM/10 and VM/11 took the excavations beyond the surface grid to 6demonstrate that the area rich in cultural material extended further than had at first been estimated, although VM/11 showed a rapid decrease in finds to the west. Three additional squares were dug to the north of VM/8 to increase the sample.

Figure 6. VM excavation looking west.

As the main trench moved to the west, the deposit became deeper, reaching a maximum depth of 300 mm in squares VM/7, VM/8, and VM/9, and lessening to 180 mm on the western side of VM/11 (Figure 6). Thus, 15 square metres comprising less than four cubic metres of deposit produced 6,275 pieces of glass and 475 pieces of pottery. In addition 11 metal buttons, a free standing crown and anchor insignia, several percussion caps and other metal objects, mainly nails, were recovered. A single gunflint, in bluish-grey flint was also recovered.

The surface collection had indicated the possibility that some of the glass had been utilised by the Aborigines. Of the glass excavated 827 pieces were isolated as possible implements. In addition three fragments of chert and another unworked flake of quartzite were excavated. Finally the number of marine food shells in the deposit suggested that this European rubbish dump might also have been camped on by Aborigines, and that the glass had represented a source of raw material for them.

An additional surface collection of this site-unit was made at the end of the 1966 season, and again in 1967. The totals of these collections are listed under VM/S/GENERAL SURFACE, and are included in the overall totals for glass and pottery.

Finally these excavations yielded 480 gm of bone representing food remains. These have not been tabulated. Among the identifiable bones the following animals were represented; cow/buffalo, sheep/goat, pig, wallaby, fish.

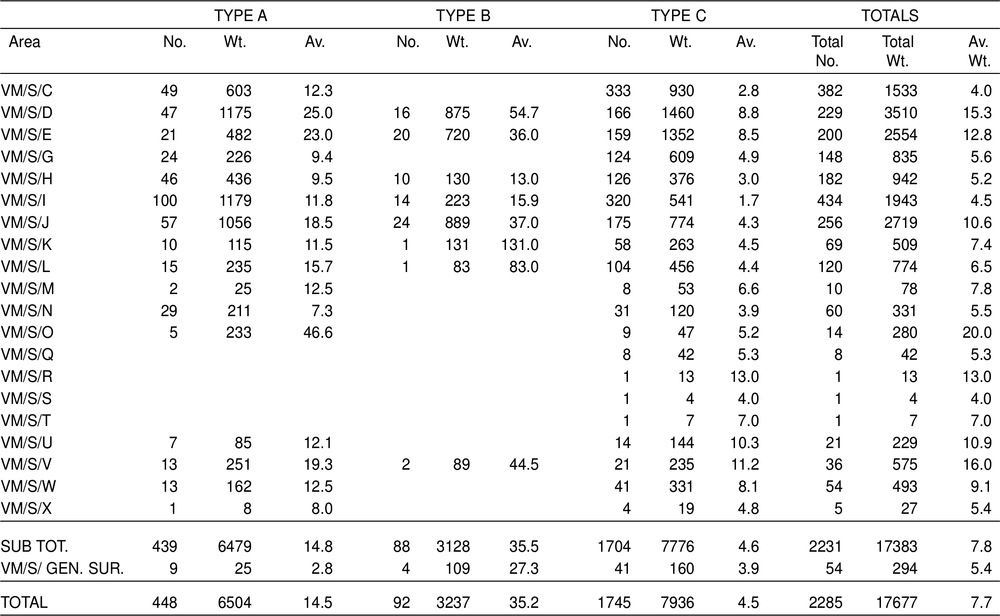

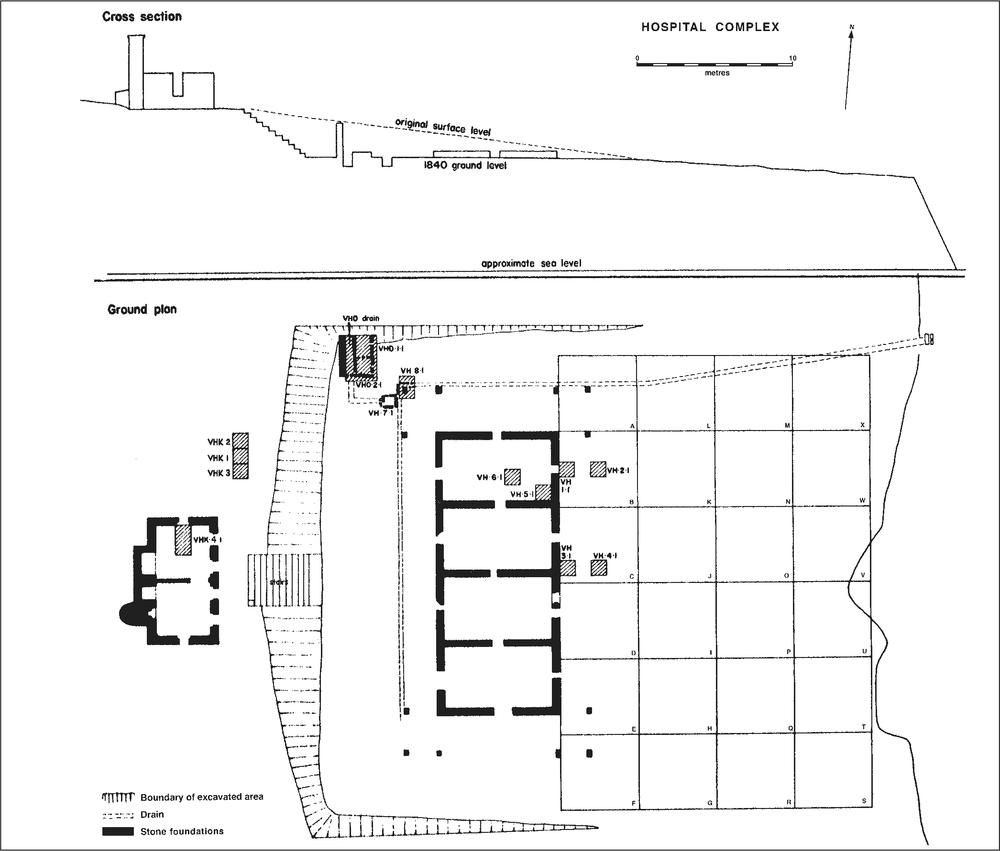

Table 1. Glass from VM surface collections according to type: number, weight in grams, average weight.

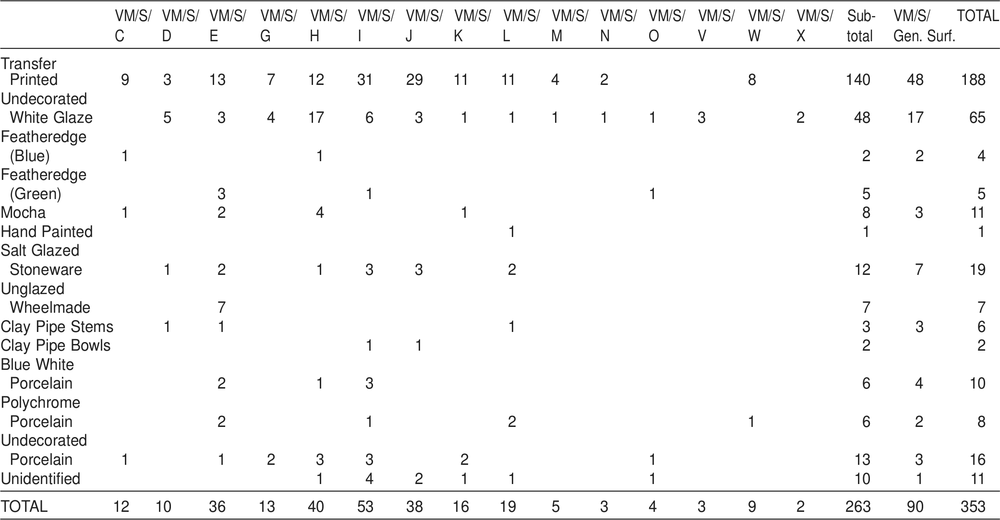

Table 2. Glass from VM excavations according to type: number weight in grams, average weight. Surface collection data have been added to give total numbers.

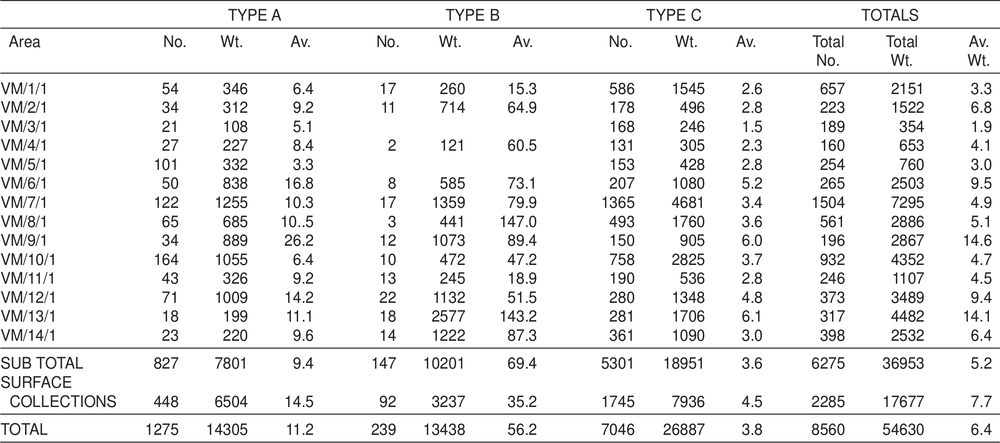

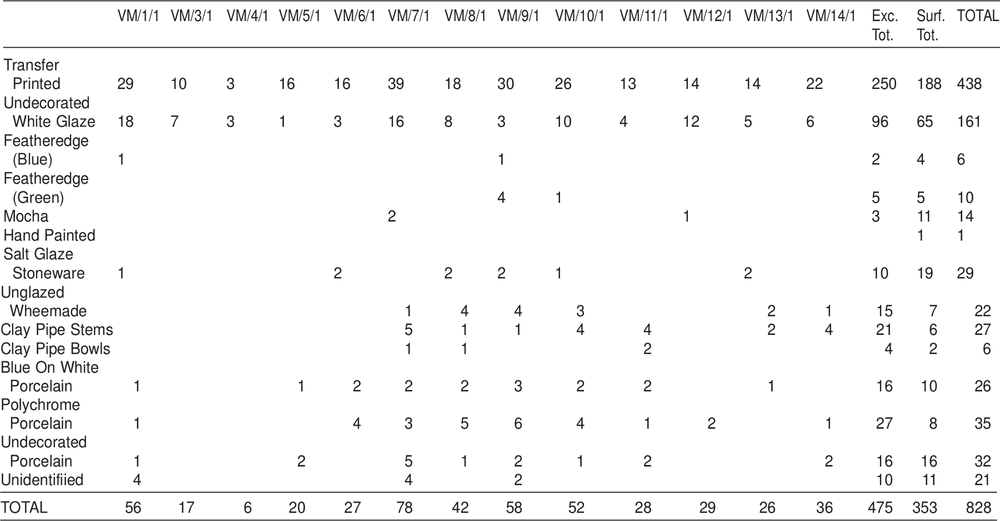

Table 3. Pottery counts from VM surface collections according to type.

Table 4. Pottery counts from VM excavations according to type. Surface collection data have been added to give total numbers.

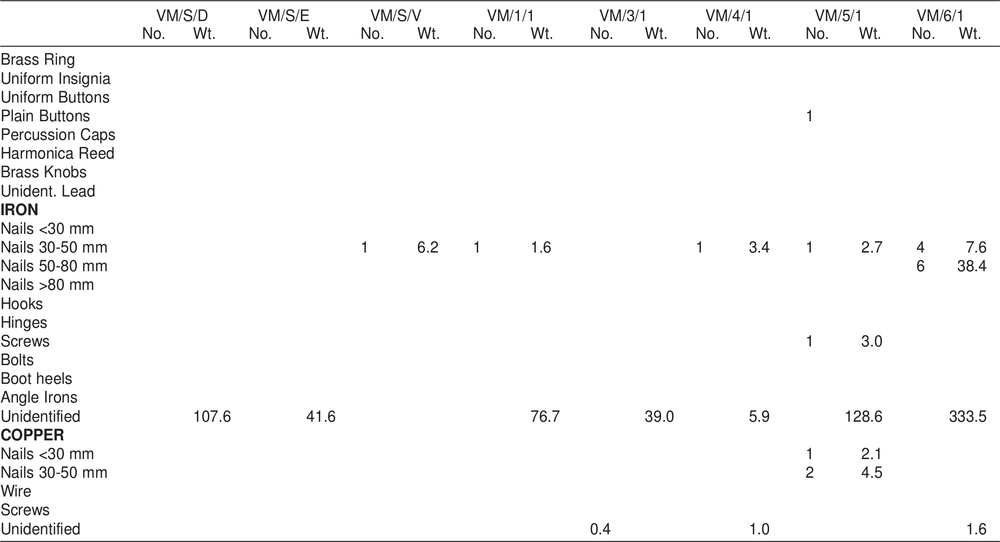

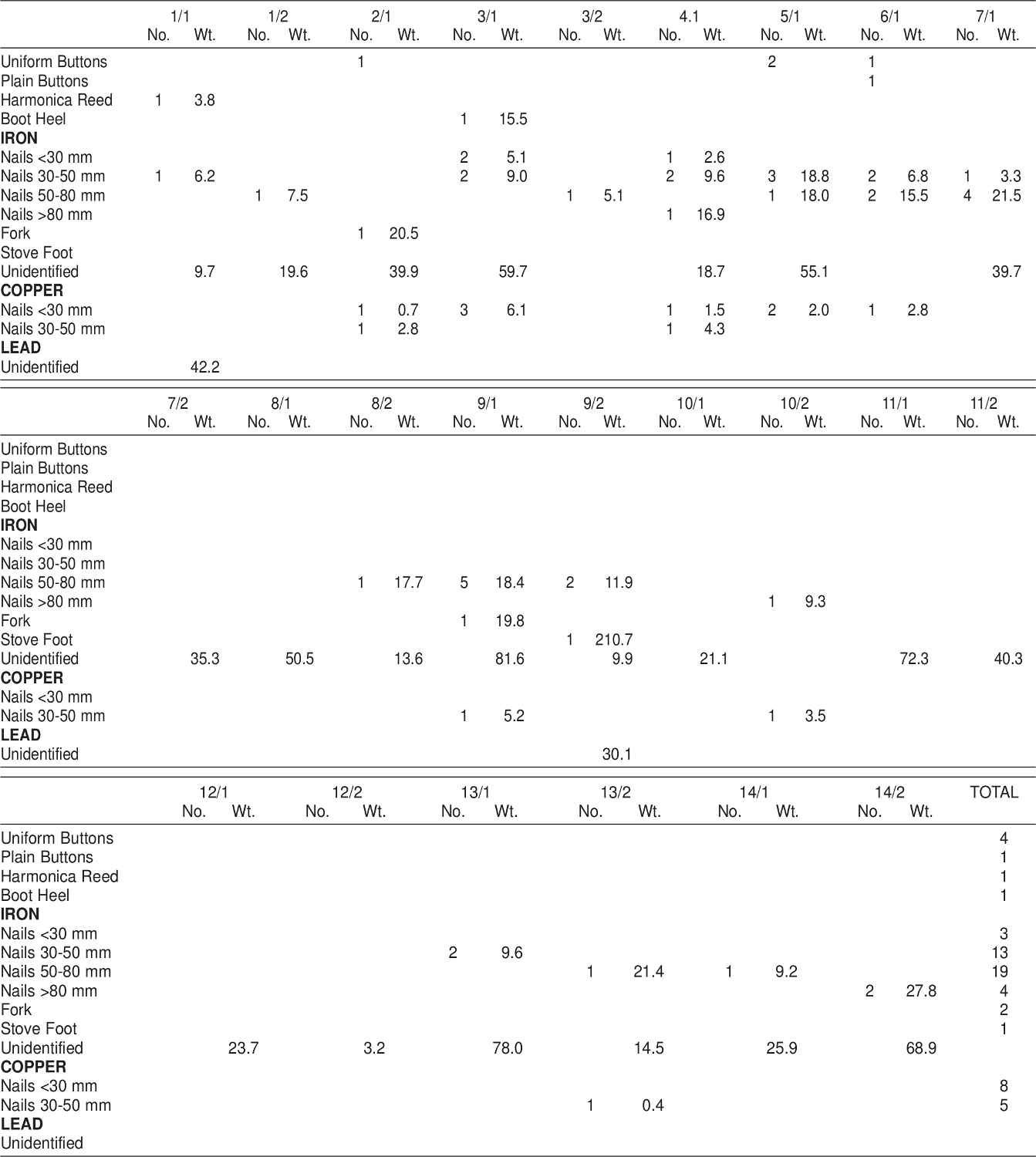

Table 5. Metal from VM surface collections and excavations combined. Weight in grams. Because of an error in processing, VM/7/1 and VM/8/1 were inadvertently mixed prior to labelling. For that reason they have been dealt with here as a single group, VM/7/1.

Table 6. Aboriginal and European stone from VM. Weight in grams.

| VM/S/1 | VM/4/1 | VM/8/1 | VM/14/1 | TOTAL | |||||

| No | Wt | No | Wt | No | Wt | No | Wt | ||

| Cores | 1 | 54.1 | 1 | ||||||

| Flakes | 2 | 3.2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 0.8 | 4 | ||

| Gunflints | 1 | 10.6 | 1 | ||||||

VICTORIA RUBBISH DUMP No. 2 (Code prefix VMII)

A second area of concentrated refuse was located 10 metres west of a shell floor (VSFII) and was assumed to be associated with it. No specific surface collection was made here; surface finds from this locality are incorporated into the general site surface collection. However two square metres were excavated and produced quantities of glass, pottery, metal, and some bone and stone. The total depth of deposit was 200 mm and no further excavations were undertaken at this site-unit.

In general the finds parallel those from VM, illustrating that the dump was associated with the nearby houses, but indications of Aboriginal activity on this site-unit are also apparent.

Table 7. Glass from VMII excavations according to type: number, weight in grams.

| Type A | Type B | Type C | Total | |||||

| Square | No | Wt | No | Wt | No | Wt | No | Wt |

| VMII/1/1 | 22 | 183.8 | 8 | 183.0 | 192 | 553.4 | 222 | 920.2 |

| VMII/2/1 | 10 | 228.5 | 6 | 186.4 | 80 | 428.1 | 96 | 843.0 |

| TOTAL | 32 | 412.3 | 14 | 369.4 | 272 | 981.5 | 318 | 1763.2 |

In addition to glass, pottery and metal (see Tables 7–9) one unworked struck flake of grey chert was recovered from VM11/1/1 and 991 gm of bone were recovered from the excavations, from which the following animals were identified: cow/buffalo, sheep/goat, pig, kangaroo, fish and crab.

THE HOSPITAL COMPLEX

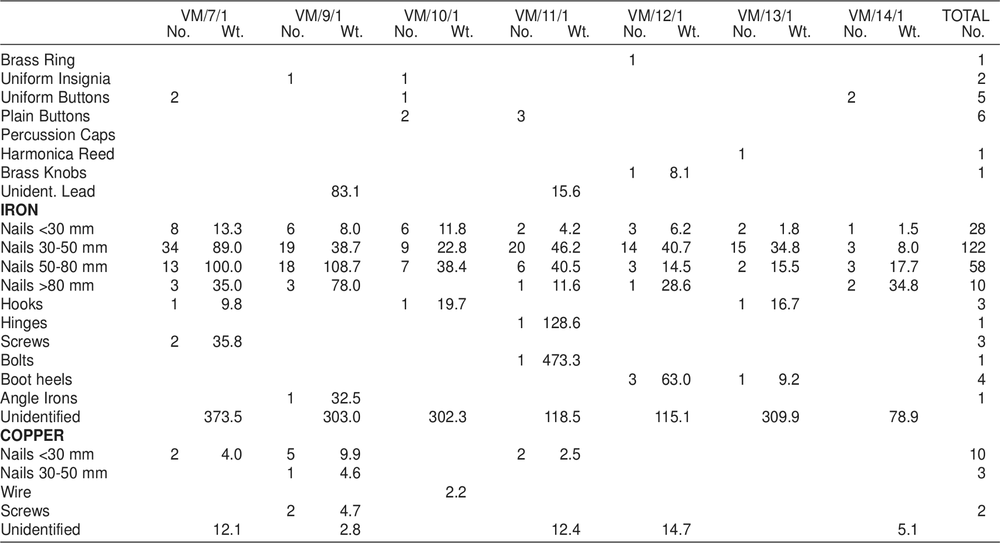

The remains of a group of three buildings were located at the northern end of the settlement (Figure 7). These could be immediately identified from the historical record as comprising the hospital complex. The hospital itself, a wooden building, had been brought from Sydney in prefabricated form and the stone foundations are now all that remain. An area of approximately 30 m by 20 m had been excavated to provide a level surface on which to erect the building. On the rise behind the hospital, the remains of the hospital kitchen were located, heavily overgrown with vines and trees, but with the stone walls still standing to roof height. In the north-western corner of the levelled area the collapsed stone wall of a smaller building was noted, and nearby, the top of a stone-lined pit suggested some form of drainage. The whole area had regenerated to monsoonal forest containing, as well, eucalypt species. The hospital had been set back about 20 m from the top of the cliff. As a number of pieces of glass were noticed in the area between the cliff top and the buildings, it was decided to make a surface collection.

Table 8. Pottery counts from VMII excavations according to type.

| VMII/1/1 | VMII/2/1 | TOTAL | |

| Transfer Printed | 36 | 3 | 39 |

| Undecorated White Glaze | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Featheredge (Green) | 1 | 1 | |

| Hand Painted | 4 | 4 | |

| Salt Glaze Stoneware | 6 | 6 | |

| Polychrome Porcelain | 27 | 1 | 28 |

| Blue On White Porcelain | 2 | 2 | |

| Macassan | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Pipe Stems | 7 | 7 | |

| Pipe Bowls | 2 | 2 | |

| TOTAL | 81 | 21 | 102 |

The Hospital Surface Collection (Code Prefix VH/S)

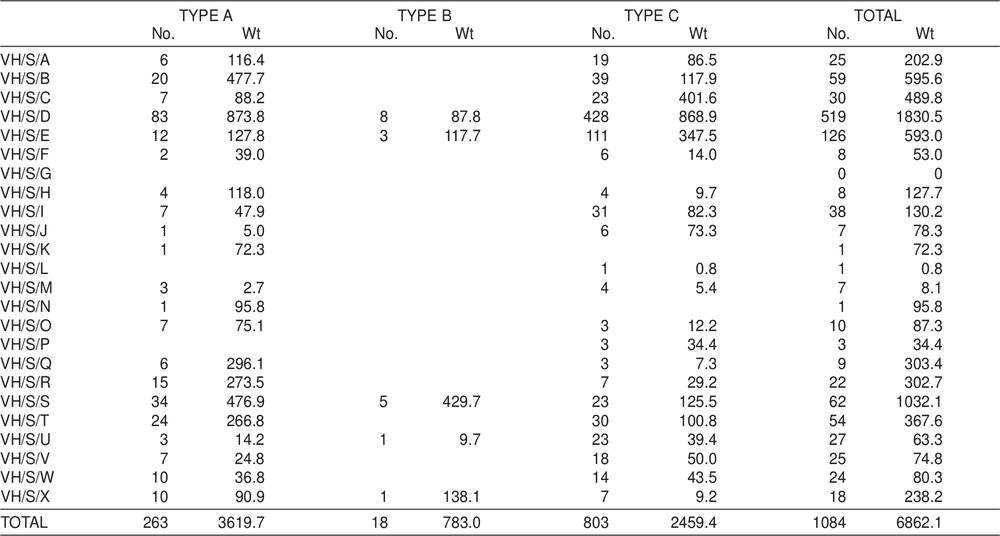

A grid of 24 squares each 5 m by 5 m, and lettered A–X was laid down and all surface material was collected (see Figure 7). The collection yielded 1,084 pieces of glass, 84 pieces of pottery, an iron nail, an unidentified piece of lead, an iron boot heel and a single fragment of flaked slate. As can be seen from the distribution of the material the finds divide into two areas, the squares immediately adjacent to the hospital building and the squares along the cliff line. (Much more debris was visible down the cliff face and a general collection was made of this material, which is described later in this chapter in the section on the general surface collection.) There appears to be no apparent reason why 47.1% of the glass and 35.7% of the pottery should have been located in square VH/S/D, unless the room immediately behind it was the source of most breakages and empty bottles. In general however it would seem that the rubbish was merely thrown immediately outside, or towards and over the cliff.

Table 9. Metal from VMII excavations. Weight in grams.

| VMII/1/1 | VMII/2/1 | TOTAL | |||

| No | Wt | No | Wt | ||

| Uniform Insignia | 1 | 1 | |||

| Uniform Buttons | 2 | 2 | |||

| Collar Studs | 2 | 2 | |||

| Lead Musket Balls | 4 | 25.2 | 4 | ||

| Iron Nails | |||||

| <30 mm | 4 | 5.4 | 1 | 2.5 | 5 |

| 30—50 mm | 12 | 27.2 | 1 | 1.7 | 13 |

| 50-80 mm | 19 | 51.3 | 1 | 5.5 | 20 |

| >80 mm | 8 | 101.4 | 1 | 12.3 | 9 |

| Unidentified Iron | 52.8 | ||||

| Copper Nails | |||||

| 30-50 mm | 5 | 23.5 | 5 | ||

| Unidentified Copper | 3.0 | 3.2 | |||

| Brass Hinge | 1 | 6.0 | 1 | ||

| Unidentified Lead | 28.1 | ||||

As with the VM rubbish dump south of government house, a large proportion (20.6%) of the glass appears to have been utilised by the Aborigines, and two pieces of a large flat base, heavily retouched along one edge to form a scraper, were found, which fitted together (see Chapter 4). These pieces were found in squares VH/S/A and VH/S/0, and were therefore separated by at least 7 metres. This suggests that the implement was manufactured and/or used on the site, and was discarded when broken, or the two pieces were used separately. Given the amount of glass in this collection, few bases of bottles were recovered; this would also support the idea of Aboriginal exploitation of the source of this raw material, since this portion of the bottle provided the thickest glass and therefore the best for making implements.

A number of pieces of glass from the squares adjacent to the hospital were vitrified, suggesting that on its final abandonment the hospital was destroyed by fire. 10

Figure 7. Ground plan of hospital complex showing areas of surface collection and excavation.

Table 10. Glass from VH/S (surface collection) according to type: number and weight in grams.

Table 11. Pottery counts from VH/S (surface collection) according to type.

THE HOSPITAL (Code prefix VH)

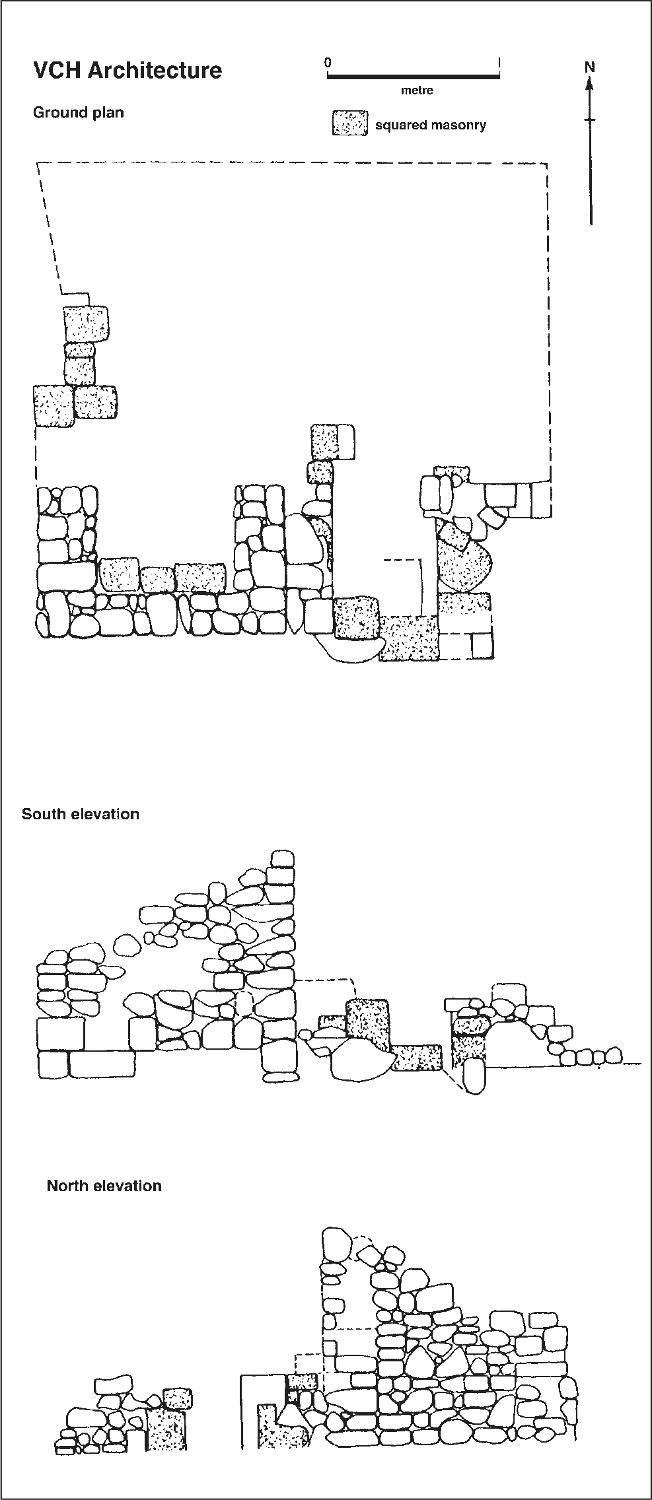

VH architecture

As noted, the only remains of the hospital building are the stone foundations on which it originally stood (Figure 8). The foundations were made of a double wall of rough-hewn ironstone with rubble fill, standing to an average height of 400 mm above the ground surface, and varying between 450 and 500 mm wide. There is no reason to suppose these walls ever stood higher, and it seems that the prefabricated wooden frame was erected on them. The foundation walls provide an exact ground-plan of the building which was divided into four rectangular rooms with a narrow entrance in each of the connecting and external walls (see Figure 7). These appear to be rather narrow for doorways, and were probably for ventilation under the building. From a contemporary painting (Sweatman ML A1725: plate 64) it can be discerned that the hospital was bounded on the south and east sides by a verandah and this was confirmed in the archaeological record by the presence of three squared stone post supports set in the ground at each of the four corners of the building, demonstrating that the verandah extended around the entire perimeter of the building, being slightly wider on the north and south sides than on the east and west sides. From the painting it was noted that each of the corners was enclosed to provide an additional room. Along the western and northern sides a narrow, open, stone-lined drain or gutter was constructed to carry off the water which must otherwise have accumulated in this levelled area. Unfortunately, time did not permit excavations to determine whether this gutter extended along the southern side, but this assumed likely. At some point along the northern edge of the building the drain was apparently taken underground, since the outlet was located in the cliff (see Figure 7) approximately 1 m below the ground surface, and there is no evidence that there has been any natural soil deposition above it since its construction.

Figure 8. Foundations of the hospital (VH) in foreground, looking north-west towards the remains of the dispensary (VHD).

VH excavations

Traces of shell flooring were apparent at the southern end of the eastern face, but not elsewhere around the building. A metre square (VH/1/1) was begun outside the entrance to the northern room on the eastern side to see if this shell flooring extended around the perimeter, but after passing through 120 mm of dark grey topsoil the deposit immediately gave way to small ironstone pebbles overlying sterile sand and clay. Finds consisted of fragments of glass, and nails.

A second metre square (VH/2/1) was begun two metres to the east, taking the square outside the line of the verandah. Here the stratigraphy was identical to that in VH/1/1 but many more glass fragments were recovered. Two more squares (VH/3/1), (VH/4/1) were excavated on the eastern side. The first of these was dug in a similar position to VH/1/1, but 5.5 m south of it, so as to encounter the shell flooring noticed on the surface. Here the shell ran through the deposit layer (although never thick) until the sterile layer was encountered at a depth of 80 mm. Finds in this square were similar to those in VH/1/1, with the addition of a worn gunflint. VH/4/1 was excavated opposite VH/2/1 and 5.5 m south of it. The stratigraphy was the same as that in VH/2/1 but contained few finds, apart from a pewter button.

Two more metre squares (VH/5/1, VH/6/1) were excavated within the northern room of the hospital. In both cases, after passing through the topsoil layer, the same sterile layer was encountered at a depth of 60 mm. This presumably was the floor when the building was occupied. Finds were again few, consisting mainly of nails and several pieces of glass. Ideas of further excavation in this area were abandoned 12because of the paucity of material remains. Instead the stone lined pit in the north-western corner of the levelled area (designated VH/7/1) was cleared out to a depth of 620 mm, where a clay floor was encountered. At the base of the western wall of this pit, an opening 390 mm high and 200 mm wide was located. The pit is constructed of rough hewn masonry cemented with a mixture of lime and clay. The purpose of this sullage pit is unclear.

Figure 9. Excavation showing stone lined open drain running along border of hospital. Sullage pit on extreme right. Large block is north-west corner of verandah.

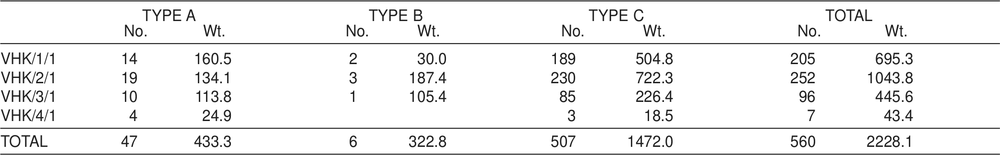

Table 12. Glass from VH excavations according to type: number and weight in grams.

| TYPE A | TYPE B | TYPE C | TOTAL | |||||

| No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | |

| VH/1/1 | 6 | 158.0 | 1 | 18.2 | 13 | 26.2 | 20 | 202.4 |

| VH/2/1 | 11 | 104.7 | 6 | 94.1 | 182 | 530.5 | 199 | 729.3 |

| VH/3/1 | 20 | 59.9 | 20 | 59.9 | ||||

| VH/4/1 | 3 | 4.1 | 5 | 6.6 | 8 | 10.7 | ||

| VH/5/1 | 1 | 6.0 | 1 | 6.0 | ||||

| VH/6/1 | 1 | 21.0 | 1 | 21.0 | ||||

| VH/7/1 | 2 | 8.0 | 2 | 8.0 | ||||

| VH/8/1 | 7 | 137.8 | 44 | 214.2 | 51 | 352.0 | ||

| TOTAL | 20 | 266.8 | 14 | 250.1 | 268 | 872.4 | 302 | 1389.3 |

Immediately to the north of the pit several of the gutter stones were visible and an area 1 m by 1.5 m (VH/8/1) was excavated to reveal the gutter (Figure 9). A large stone block was also uncovered which proved to be the corner of the verandah of the hospital. The gutter on the western side meets the gutter on the northern side at this corner, and is unconnected with the pit, flowing between it and the verandah line. The gutter proved to be 150 mm deep at this point, lined on the bottom and both sides by uncemented stones. Here the sterile layer outside the gutter is higher than inside (in the north-western corner room) and possibly this room had loose stone flooring. Several flat stones were removed from this area before this possibility was realised. Finds consisted of several nails and some glass.

Table 13. Pottery counts from VH excavations according to type.

| VH/1/1 | VH/2/1 | VH/3/1 | VH/4/1 | VH/8/1 | TOTAL | |

| Salt Glaze Stoneware | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Undecorated White Glaze | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Pipe Stems | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Pipe Bowls | 1 | 1 | ||||

| TOTAL | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

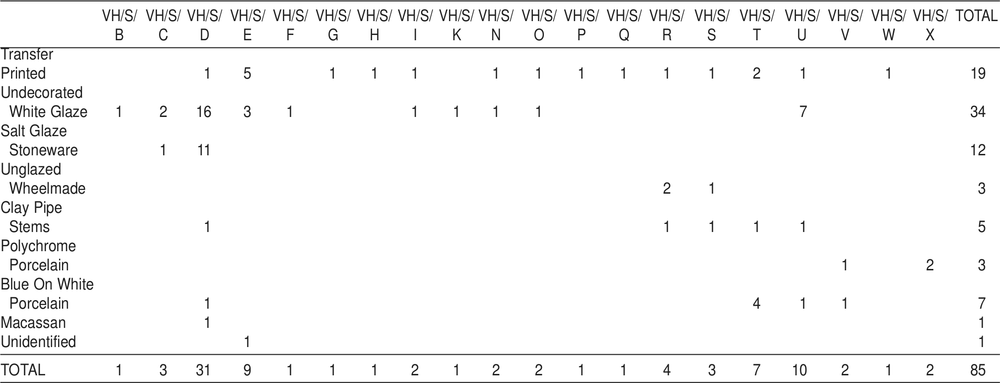

Table 14. Metal from VH excavations. Weight in grams.

HOSPITAL DISPENSARY (Code prefix VHD)

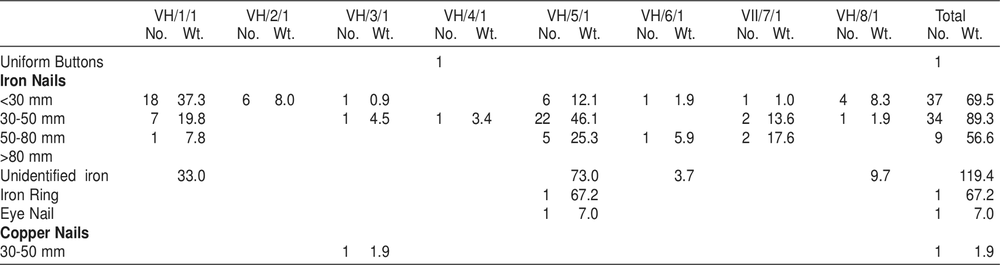

VHD architecture

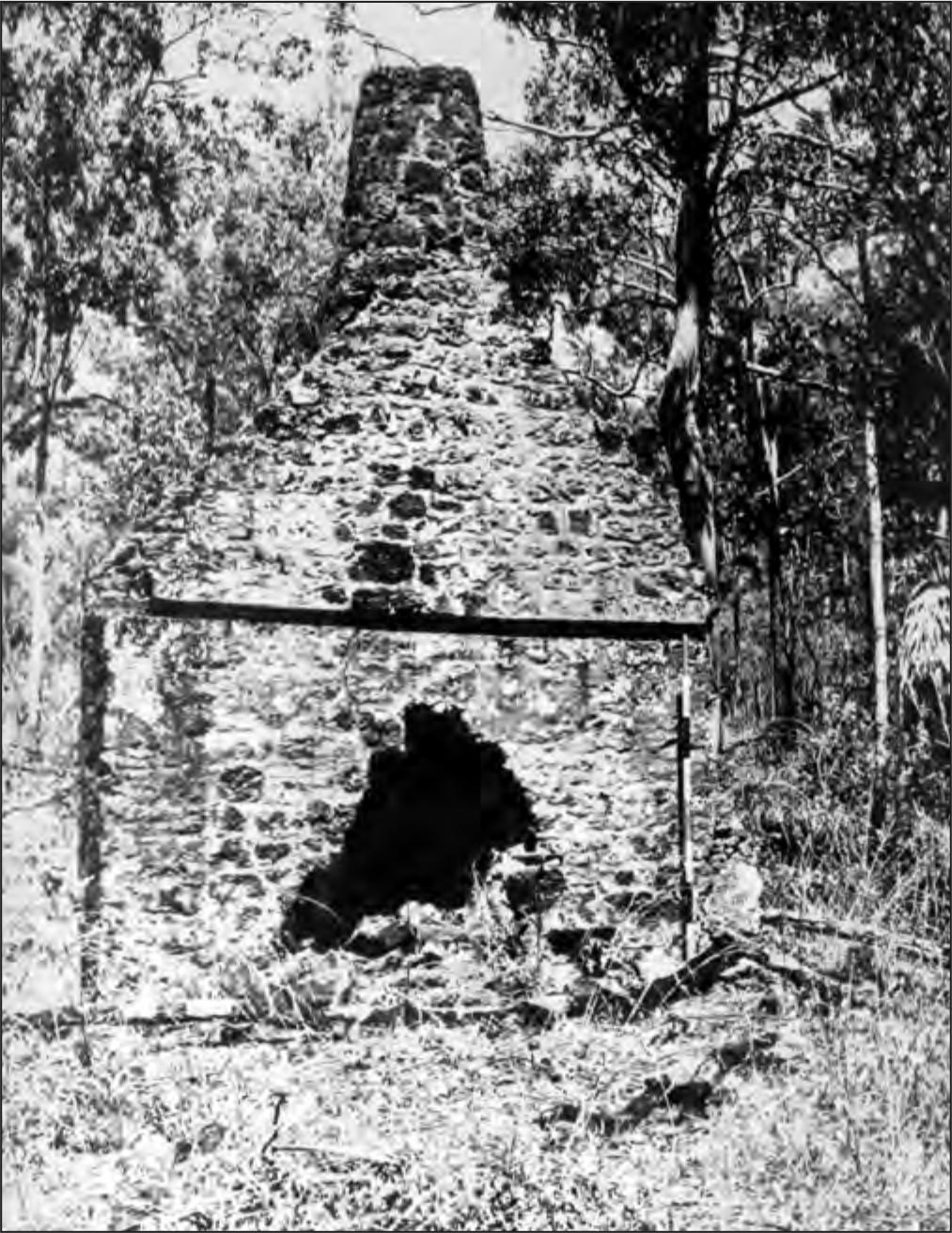

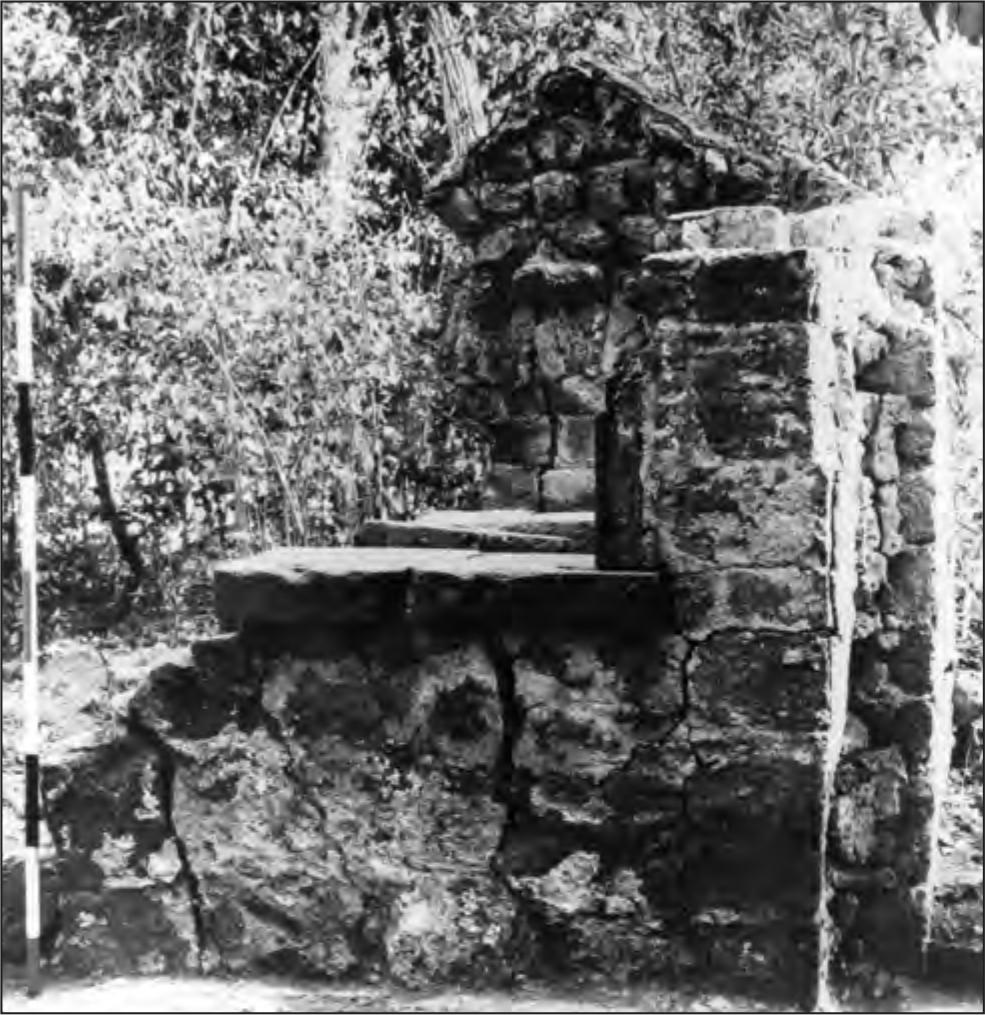

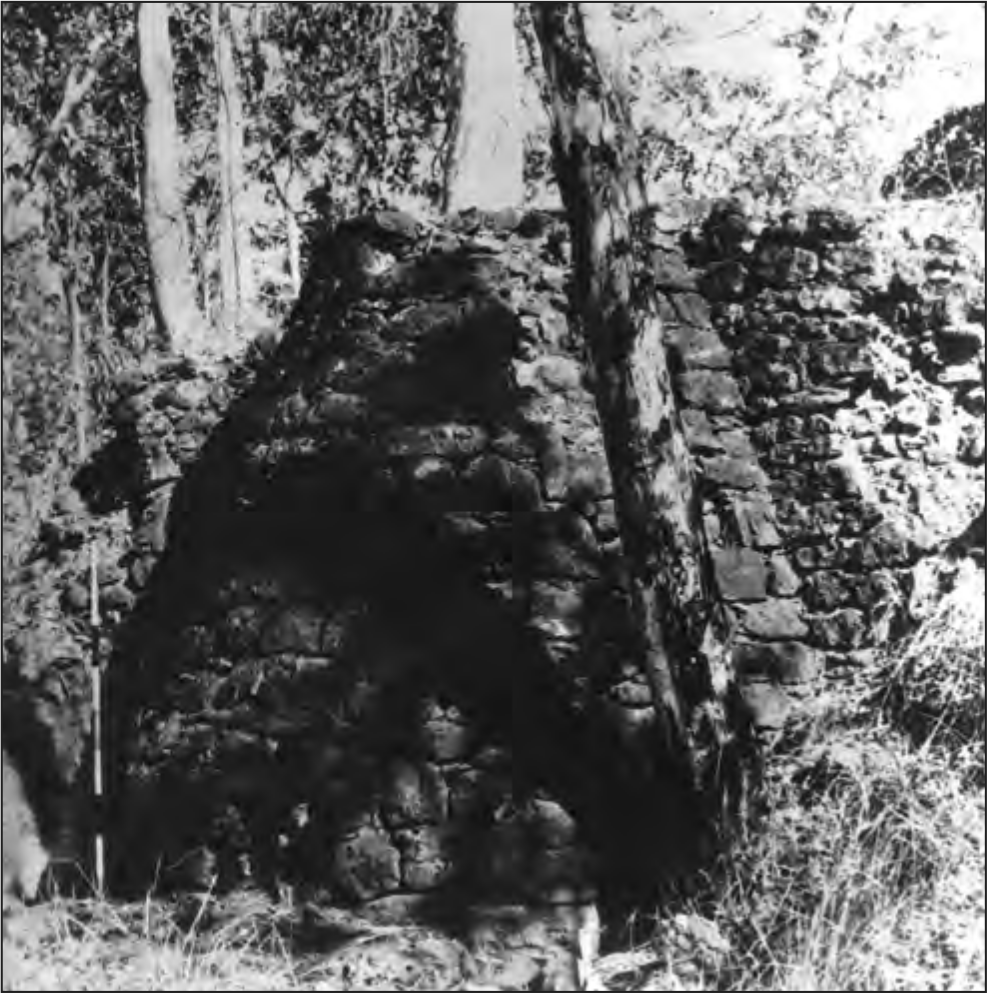

In the extreme north-western corner of the levelled area the single (western) stone wall of a building was located (Figure 10). From the area of rubble the building appeared to be small, and from the standing wall certain observations could be made. The wall appeared to have originally had two windows, between which a vertical row of bricks standing from the wall suggested a dividing wall across the east-west axis of the building. Apart from this row of bricks the wall was constructed of rough-hewn ironstone. In the northern and southern faces of the central pillar two square holes suggested the places where beams had been placed to form the tops of the windows.

Figure 10. Two elevations of the remains of the dispensary. See text for discussion.

VHD excavations

A 2 m by 2 m square (VHD/1) was excavated adjacent to the standing wall on the eastern side. After passing through 500 mm of rubble (mainly bricks), shell flooring was encountered, divided by a single row of bricks which coincided with the line of bricks tied into the upright wall. This horizontal row of bricks did not extend right to the wall however, stopping 580 mm from it, where it coincided with a row of square stones running parallel to the standing wall. Between this row of stones and the wall the shell flooring gave way to dark grey soil, and this area was interpreted as a drain. At the eastern end of the row of bricks another line of squared stones was uncovered, running parallel to the first, and this marked the eastern side of the building. Adjacent to the easternmost brick in the row, a 4 centimetre square post hole had been carved into the stone block on which the brick stood.

The square was extended (VHD/2) a further 50 mm 14towards the south, and the southern wall of the building was uncovered, again built of roughly shaped stone. Outside the wall line the excavations were taken down 250 mm at which point the rubble footings were encountered, extending out 250 mm beyond the perimeter of the building. The finds in this square were of a similar nature to those from VHD/1/1, nails and glass, but beyond the building line the glass immediately increased in quantity.

Figure 11. Hospital dispensary looking south, showing half excavated stone drain. Note remains of brick dividing wall tied into standing stone wall and continuing across the floor of the structure.

Finally excavations were commenced to clear out the drain (VHD/Drain) at the southern end (Figure 11). This proved much deeper than anticipated and the nature of the deposit (decayed bricks and mortar which had solidified, probably through water action) hindered progress, and the drain clearance was continued only to a point immediately beyond the line of bricks, demonstrating that this dividing wall did not continue below the floor line. At a depth of 890 mm a clay floor was encountered with an opening at the southern end 320 mm by 250 mm, apparently connecting this drain with the stone-lined pit (VH/7/1) described above. The walls of this drain were constructed of well cut ironstone blocks cemented in courses, and of considerably better workmanship than the same wall above ground level.

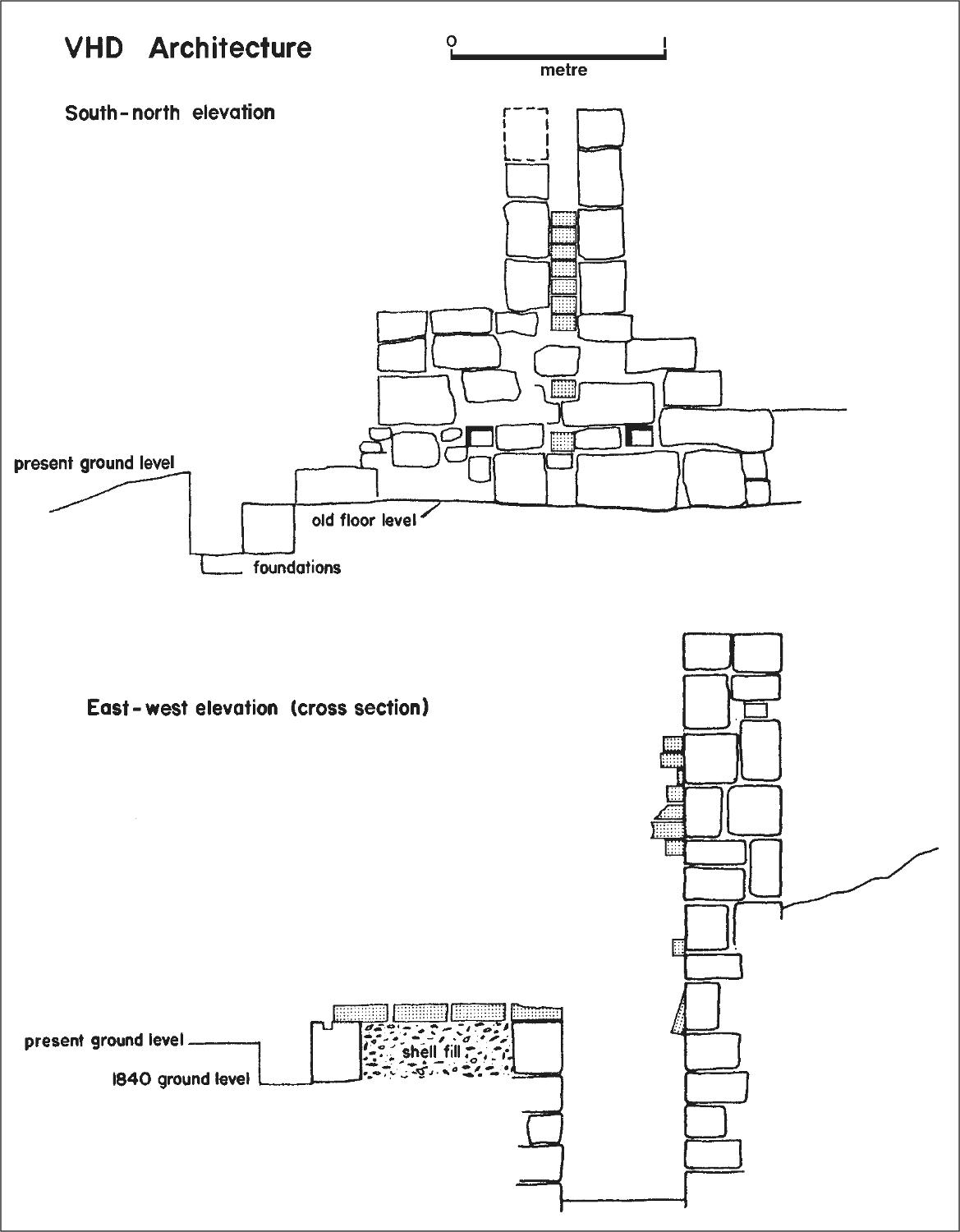

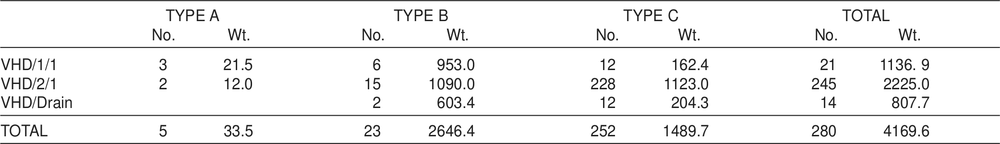

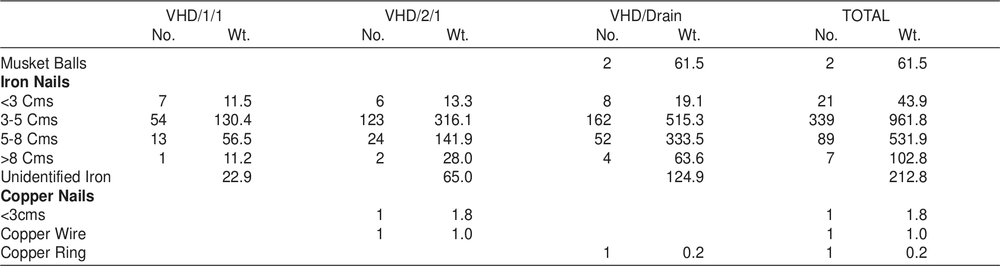

Table 15. Glass from VHD excavations according to type: number and weight in grams.

As anticipated the only finds came at the very bottom of this drain – many nails, glass, a complete but broken clay pipe and the pieces of a small ceramic palette.

Immediately above the floor a 25 mm layer of dark soil and many pieces of charcoal suggested the destruction of the building by fire.

The excavations gave no indication as to the construction of the southern, eastern and northern walls of this building. These were certainly not made of stone, and the number of bricks recovered from the excavation could be accounted for by the central dividing wall. Even if these three outer walls were of brick, and had been completely dismantled one might well assume traces of mortar on the stone perimeter. Alternatively no indications of post supports, except for that in the centre of the eastern wall, were located. One or more of these walls may well have been open. The second point of interest is the function of this building. Given its size, neither room could have had more than one occupant at any one time. Two beam holes in the eastern face of the standing wall suggest some form of table or stand above the drain in each compartment. One suggestion is that the building was a primitive ablution block. Alternatively there is one brief historical reference to the hospital dispensary (Sweatman ML A1725:257) and the broken palette excavated in VHD/Drain tends to confirm the interpretation of this building as the dispensary. The purpose of the connection between the drain in this building and the stone-lined pit remains unclear and neither the pit itself nor its contents offer any indication of the function of the building.

Table 16. Pottery counts from VHD excavations according to type.

| VHD/Drain | |

| Undecorated White Glaze | 3 |

| Pipe Stems | 1 |

| Pipe Bowls | 2 |

| TOTAL | 6 |

Table 17. Metal from VHD excavations. Weight in grams.

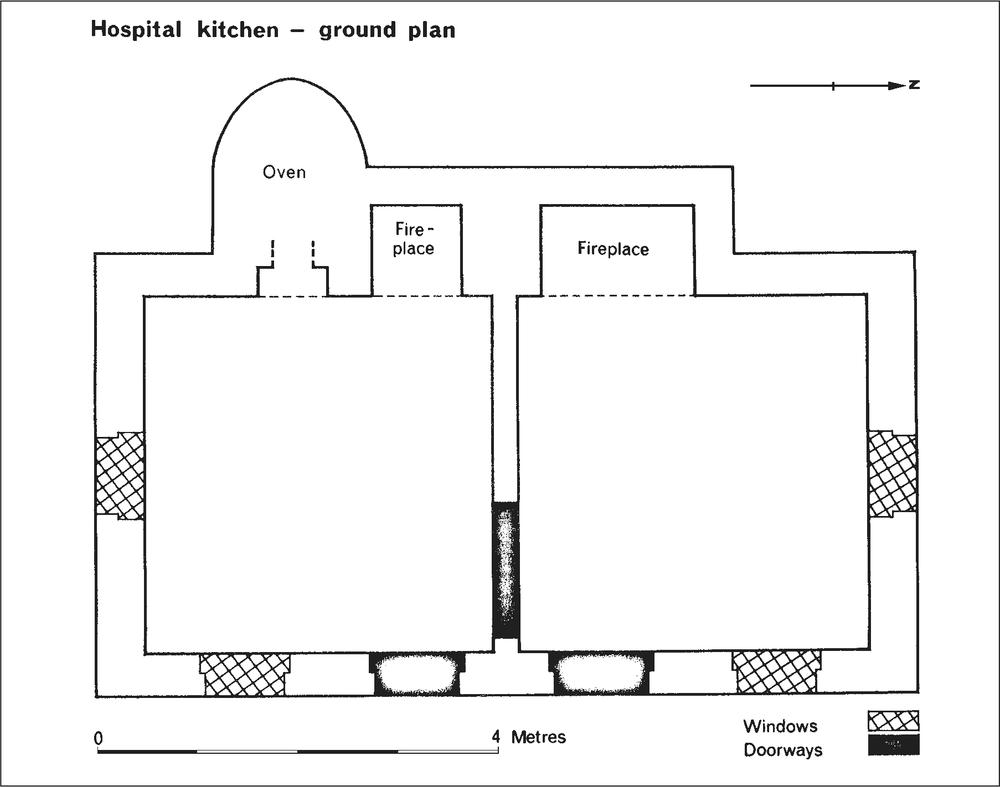

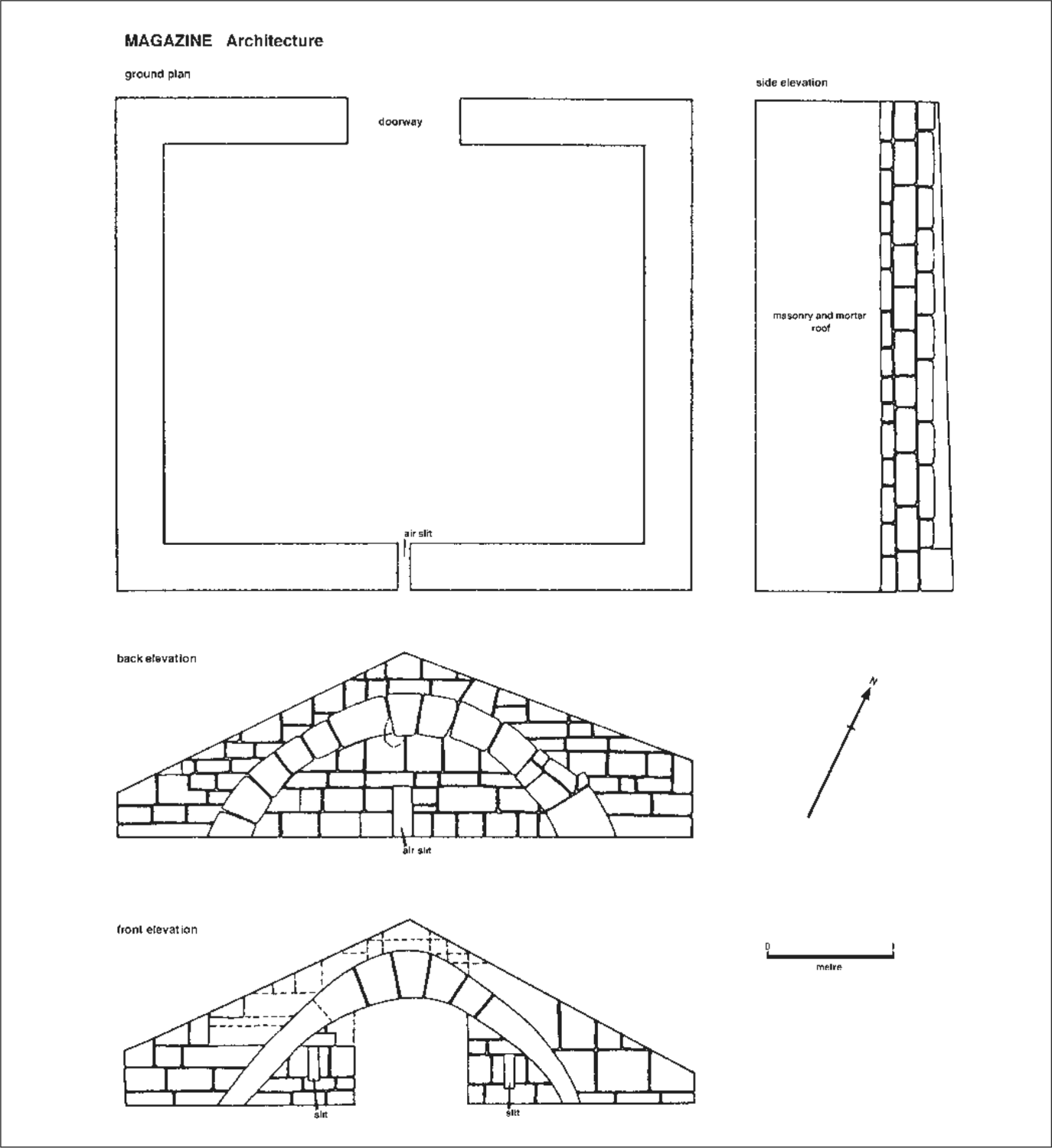

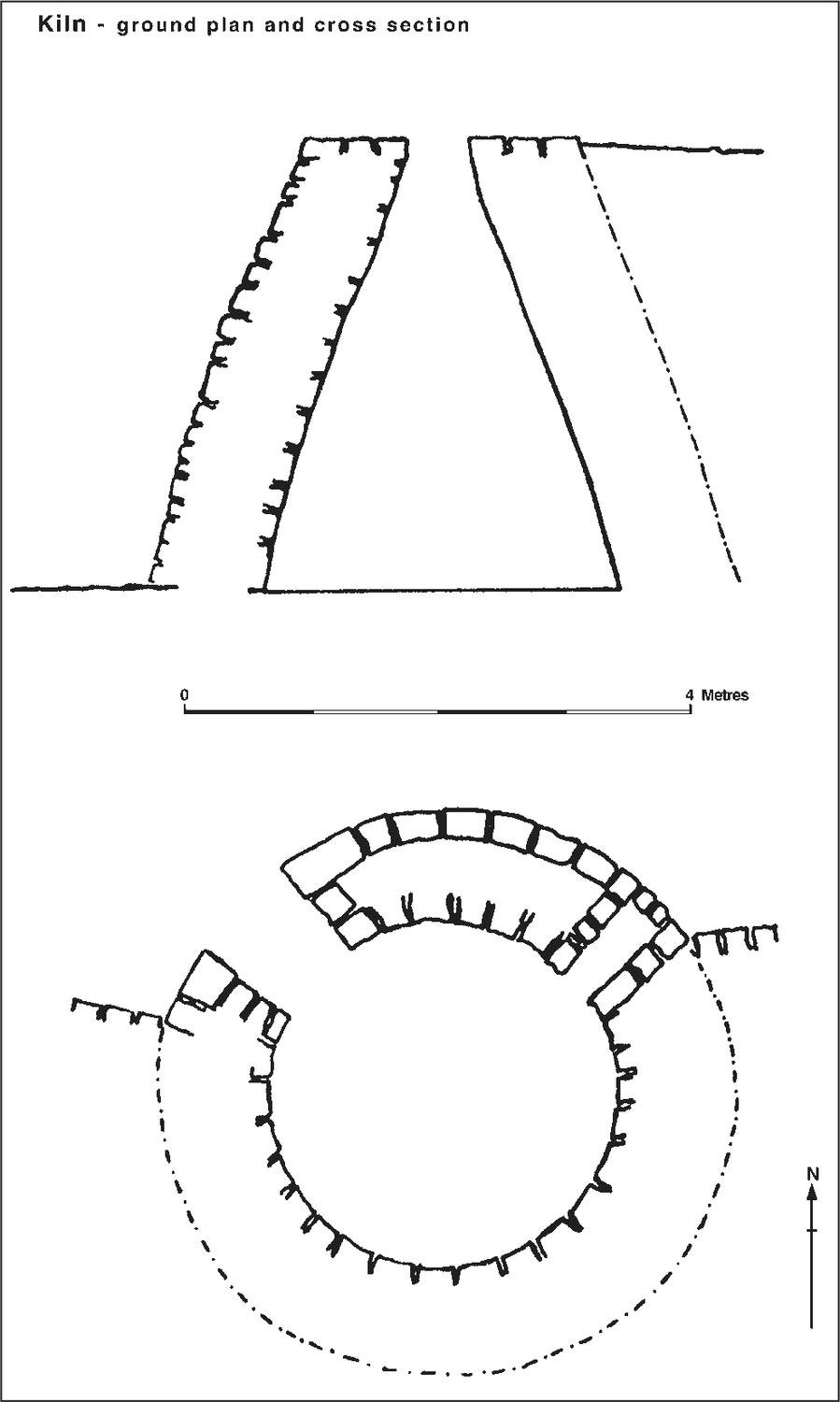

HOSPITAL KITCHEN (Code prefix VHK)

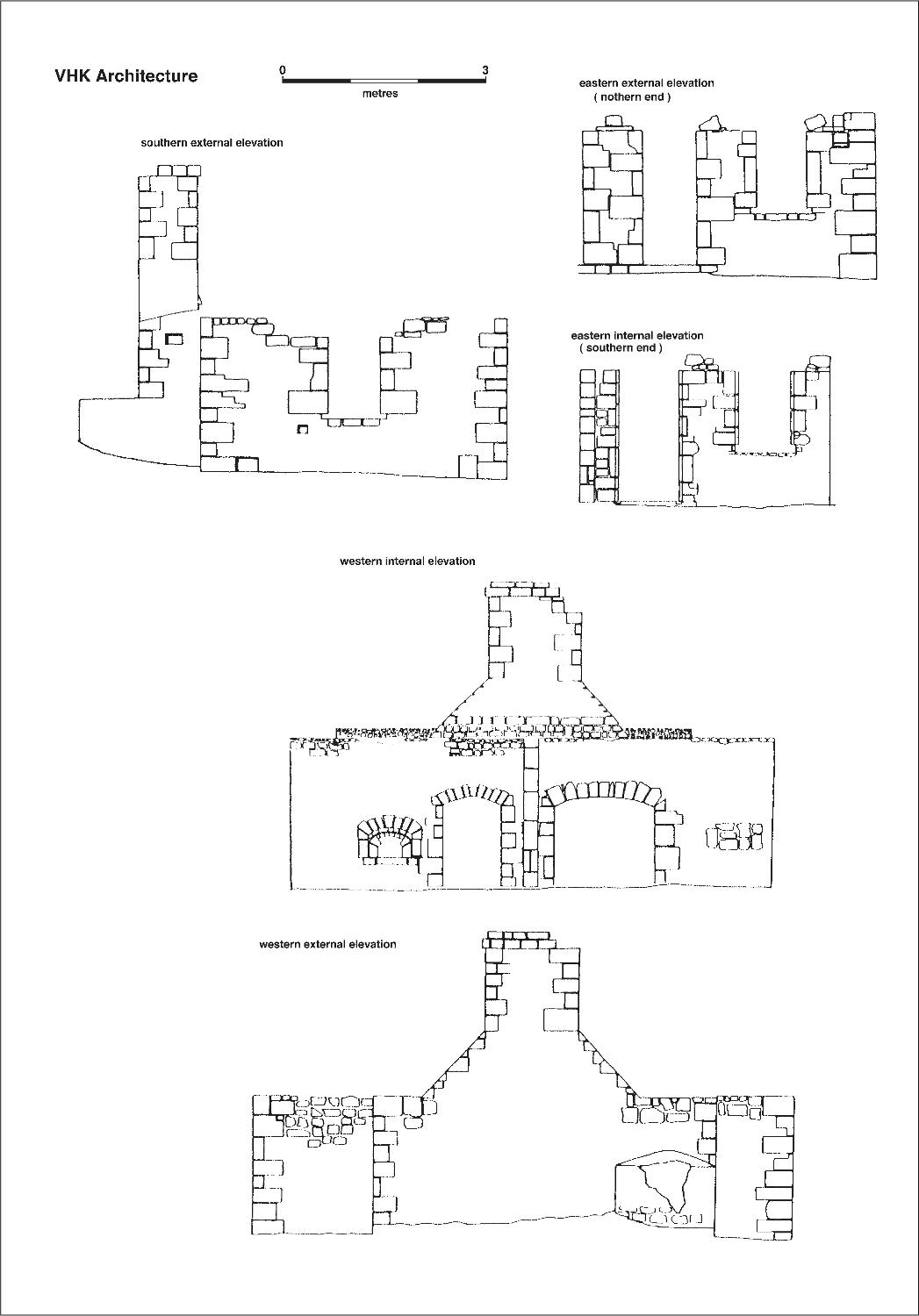

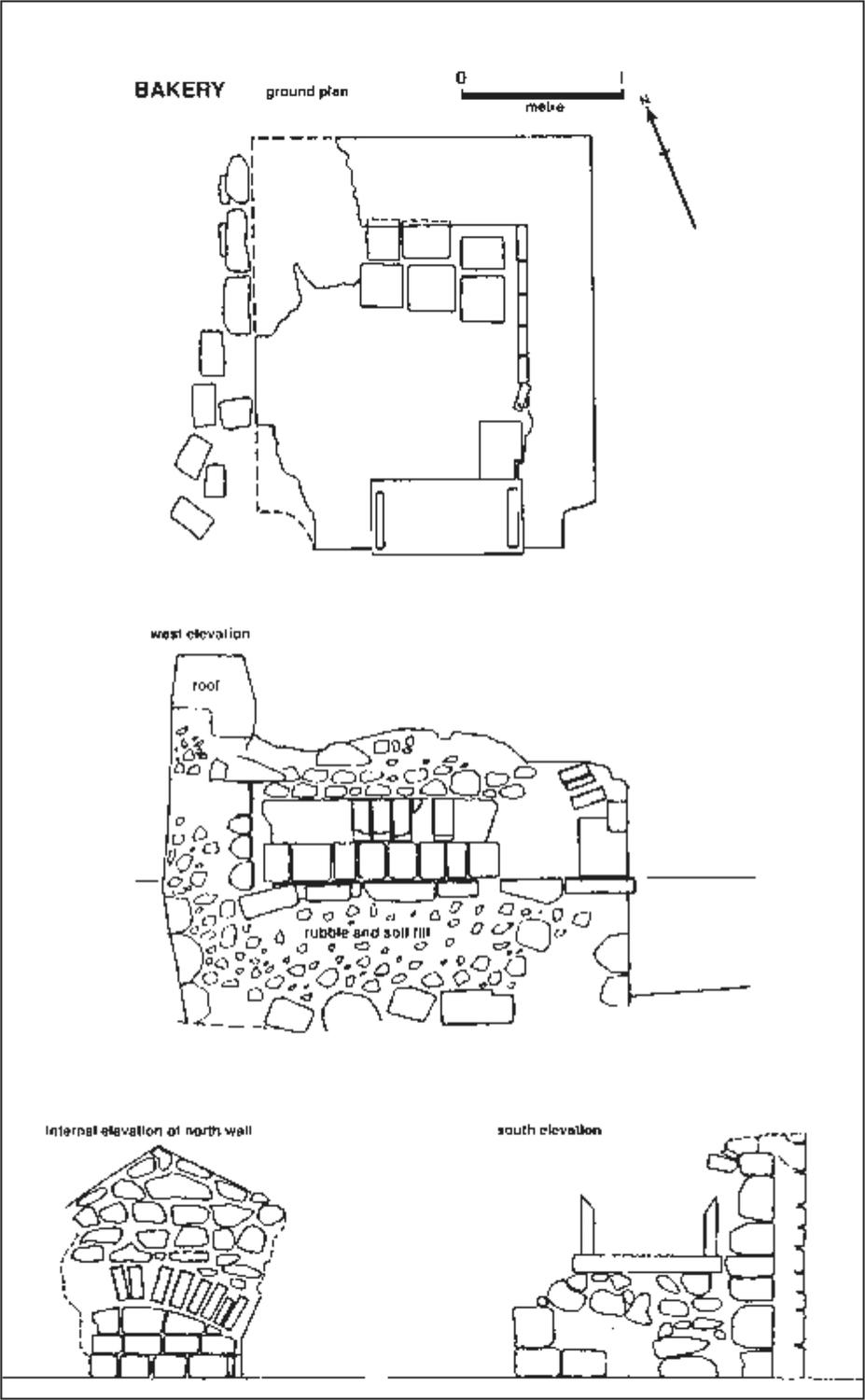

VHK architecture

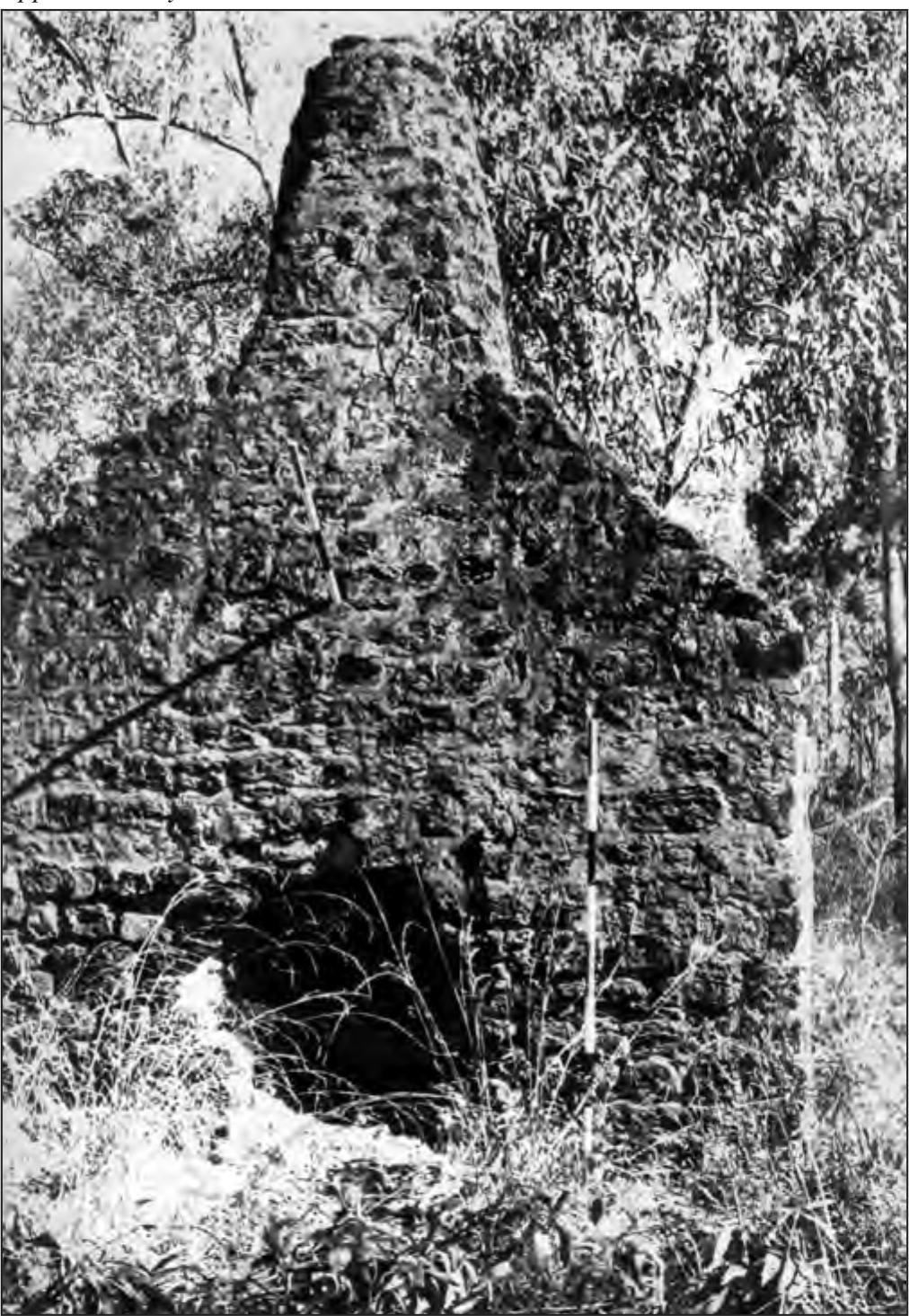

This building is the best constructed and one of the better preserved buildings in the settlement. Built entirely of the local ironstone, all the corners, entrances, windows and the chimney are quoined in excellent masonry and the building is to be attributed to the convict masons stationed at Port Essington in 1845–6 (see Chapter 8). The walls comprise a double row of stones, whose external faces are rough-hewn, with the gaps between being filled with rubble and cement. These stones are laid approximately in courses, with the joints rendered in cement to provide a reasonably smooth surface (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Remains of hospital kitchen (VHK) looking north-west (a) and south-east (b).

With the exception of the fireplace wall on the western side, the building is perfectly symmetrical, and presumably follows a stock design of the period (see Chapter 8). It consists of two rooms divided by a free-standing wall (i.e. not tied into the western wall) connected by an internal doorway (Figures 13 and 14). The floor level is raised above the outside ground level, using stone doorsteps and an internal flooring of shell. On the insides of the door uprights the remains of timber jambs measuring 60 by 100 mm, are reflected in the cement (Figure 15a) and slots were cut to receive them in the stone door steps. Cuttings in the stone also reflect the use of wooden lintels and window sills, which averaged 100 mm in thickness.

In the western wall of each room is a fireplace, that in the northern room being larger than that in the southern room, while this latter room also contains a baking oven. In ground 16plan the oven is oval, with an arched dome and a solid fill floor. This oven apparently worked on the same principle as that described for the bake house (below), with additional heat being supplied from the adjacent fireplace. The opening into the oven is recessed, and above the recess an air vent has been built leading into the southern chimney in order to draw off smoke during the firing. Although combined externally, the chimneys from each room have separate angled exits, with the internal faces pargetted.

Figure 13. Ground plan of hospital kitchen.

A close examination of the western wall indicates that the chimneys and oven were built separately and the thick section of the wall above the oven was added after (see western external and internal elevations and southern elevation Figure 14), presumably for added insulation. This section was built of solid rubble fill, and from the impressions remaining in the cement it had been roofed with wooden shingles, in a similar manner to the bake house (q.v.). Wooden shingles are inferred from the absence of slates or clay tiles near either baking oven. This section of the roof is pitched at an angle of 15º, but it is reasonable to suppose that the shingle or thatch roof over the main part of the building was pitched more steeply than this. That the main roof was pitched along the long axis of the building is suggested by the presence of a row of projecting stones in the eastern face of the chimney, under which the roofing material was butted (Figure 15b). This is reminiscent of similar rows of sloping projected stones on the towers of late medieval English churches, where the object was to carry rainwater off the face of the building. If the purpose of these stones was to prevent rainwater running between the thatch and the face of the chimney into the top of the wall some form of guttering must have been placed below the drip line and above the thatch. No indication of this remains.

The only use of brick in this building is the lining in the top of each of the chimneys.

VHK excavations

Some glass and pottery fragments had been noticed near the north-east corner of the kitchen, and one conjecture was that this was a rubbish disposal area for the kitchen. A 1 m by 1 m square (VHK/1/1) was excavated in what appeared to be the centre of this deposit (see Figure 7). After passing through a dark soil layer for 200 mm the deposit gave way to a sterile layer similar to that encountered in the previous excavations. The deposit produced quantities of oyster shells (but not other varieties), glass, pottery, metal, and bone food remains. Despite the fact that some of the pieces of glass appeared to be Aboriginal artefacts, the nature of the overall finds appeared equally to suggest that the deposit was as likely European as Aboriginal material laid down after the settlement was abandoned. The excavations were extended one metre to the north (VHK/2/1) and one metre to the south (VHK/3/1). Similar stratigraphy to VHK/1/1 was recorded for both squares, with the depth of deposit lessening at the northern end of VHD/2/1 and the southern end of VHK/3/1. Similar finds were also recorded in these squares, with the addition of a copper coin in VHK/2/1. Un-milled, circular and with a square hole in the centre, the coin was identified by Dr Noel Barnard (Department of Far Eastern History, A.N.U.) as a supika, an Indo-Chinese imitation of a Chinese coin, of small value, common in such commercial centres as Singapore at this period. This coin is identical to two others excavated in other parts of the site.

In order to examine the wall foundations and flooring of the kitchen, an area 2 m by 1 m was excavated immediately below the window in the northern room. The flooring proved to be the shell flooring traditional in the settlement. This was laid to a depth of 150 mm over sterile sand. Approximately 900 mm from the wall this sand changed to grey soil, this line demarcating the line of the foundation trench. The footings, of ironstone, were set in cement to a depth of 500 mm and on the internal side, 150 mm wider than the wall. The trench had been back filled with rubble and soil. Finds were extremely limited in this area, and it was decided not to extend this excavation.17

Figure 14. Hospital kitchen elevations.

18Only 615 grams of animal bones were recovered from the excavations of which the identifiable animals represented were as follows: two cow/buffalo, sheep/goat, two pigs, wallaby, bird, fish, crab and reptile.

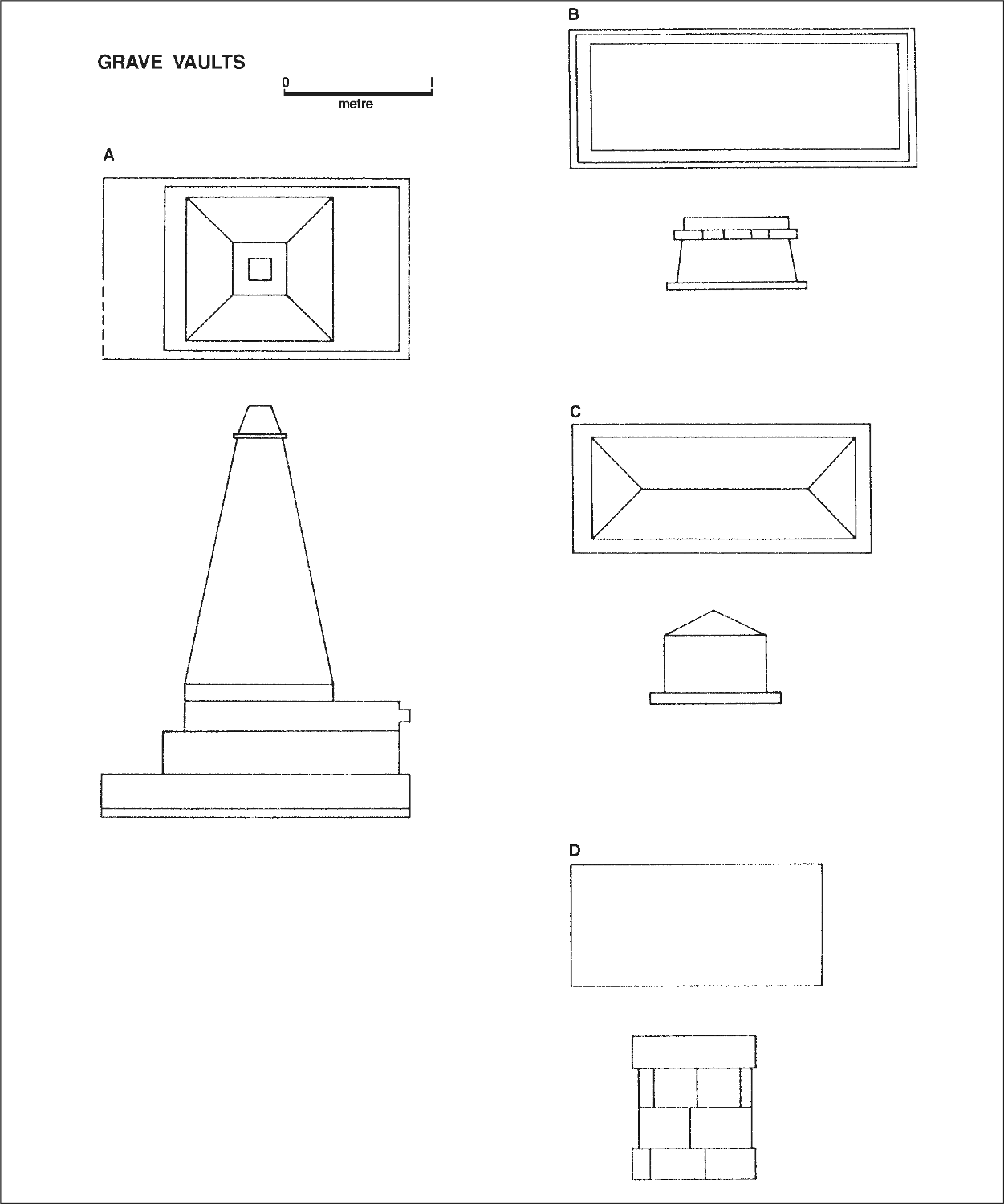

MARRIED QUARTERS (Code prefix VMQ)

VMQ architecture

North of Adam Head five semi-circular buttress stone chimneys set into the southern stone walls of the cottages which they served, were identified from the McArthur map (Figure 4) as the garrison’s married quarters. This map shows only four cottages at this location and while it is possible that only four existed when the map was drawn, it is equally likely that the map is in error, since other discrepancies in this map were identified in the field. These houses were oriented in a rough north-south line running parallel to the line of the cliff, and about 20 m from it (Figure 16). Only the southern walls with the fireplaces were built of masonry.

Figure 15. Hospital kitchen construction details. See text for discussion.

For convenience the structures have been numbered 1 to 5, from north to south. Chimney no.1 has been almost destroyed by falling trees, but a portion of the wall and chimney is still standing; the chimney of no. 5 has suffered similar damage, but still stands to an overall height of 2.5 m, so that the recording of many architectural features was possible. The remaining three structures are intact. The general dimensions of these chimneys and the design and size of the cottages are sufficiently similar to allow a single general description. However sufficient differences in detail and building technique exist to require some elaboration.

Preliminary appearances of the cottage floor mounds suggested that the dimensions of the cottages were similar. Excavation of the floor of no. 2 was carried out and is described below. This cottage had a clay floor, and possessed a stone doorstep in the western wall. However, no doorstep was visible in the floor mounds of the other cottages. No. 3 had visible indications that the floor had been cemented (at least in part) and no. 4 apparently possessed a shell floor, but 19no time was available to test these differences by excavation. Measurement of the five floors established the internal dimensions as 5.3 m long and 3.5 m wide.

Table 18. Glass from VHK excavations according to type: number and weight in grams.

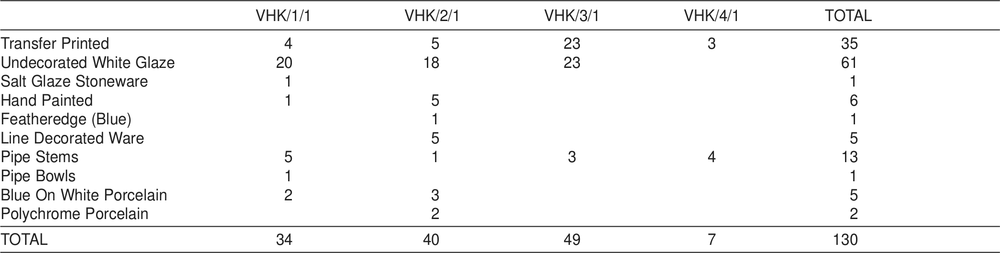

Table 19. Pottery counts from VHK excavations according to type.

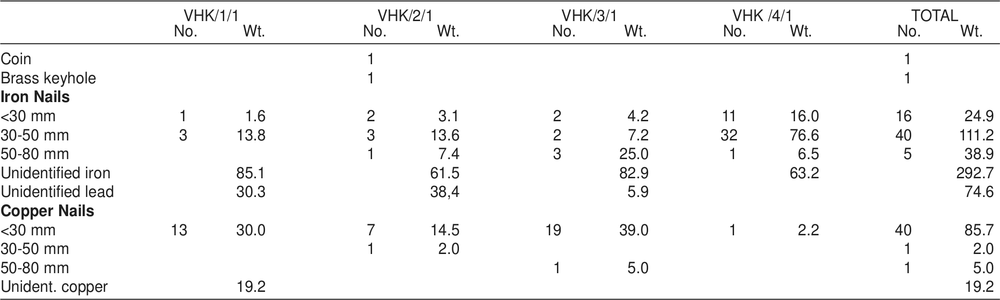

Table 20. Metal from VHK excavations. Weight in grams.

In each instance, the shape of the stone walls indicates a simple pitched roof, although this might have been hipped at the northern end. The materials used in the construction of the roof and the remaining three walls have disappeared completely. Fortunately, these particular cottages were described by a visitor to the settlement in 1848 as having grass thatched roofs and walls of bark or rushes. In the latter case the rushes were secured internally to a light framework of wood, and were held in place externally by thin strips of bamboo. The cottages had ‘1ittle square holes for light and air with little raised shutters like the ports of a Vessel’ (Brierly 1848 ML A501-4:14 November). This technique of shutters hinged at the top and propped outwards to open was used extensively in the settlement, as is evidenced by many of the contemporary sketches which have survived.

Figure 16. Married Quarters round chimneys: general view.

The southern walls and chimneys were built with ironstone blocks quarried within the settlement and cemented with lime mortar. In the cottage we excavated, the foundations were carried down two courses into the earth (430 mm) and were not set into wider footings, the dimensions paralleling those above ground-level. The stone was rough-hewn into 20blocks, rectangular but varying in size, although rarely exceeding 300 mm by 200 mm by 150 mm. Only the external faces were shaped, and the gap between the facings was filled with rubble and cement. In all the examples, the internal walls were coated with lime plaster. Bricks were used to construct the arch above the fireplace, which was in the shape of a basket arch.

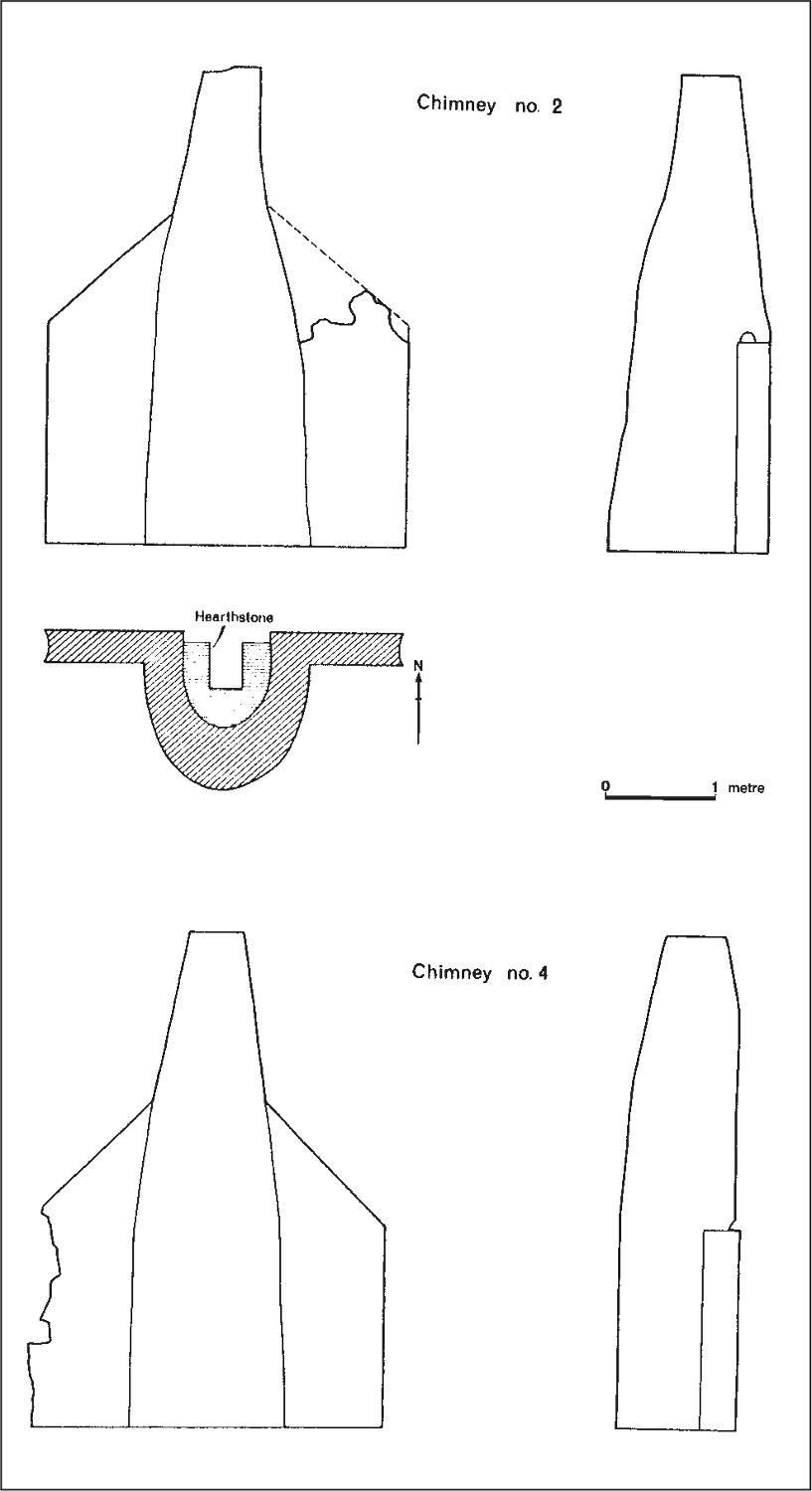

Figure 17. Married Quarters round chimneys: elevations of chimneys 2 and 4.

Despite the general similarity of design, significant variations do occur between chimneys, both in dimensions and in methods of construction. Figure 17 for example, illustrates the differences in size and shape of the chimneys of no. 2 and no. 4. Whereas no. 2 projects 1.15 m behind the wall into which it is built, no. 4 projects only 750 mm, despite the fact that they are of equal width across the base. A second variation in dimensions which should be noted is the difference in the thickness of the walls of each structure (Table 21):

Table 21. Wall thickness variations in the five married quarters.

| No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 3 | No. 4 | No.5 |

| 350 mm | 290 mm | 310 mm | 370 mm | 410 mm |

Variations in construction techniques have proved more interesting. Despite the disappearance of timbers, their original positions are indicated by holes in the stonework. On no. 1, no. 2 and no. 3, large circular posts were used at each end of the stone wall, and as the imprint of the mortar shows, the ends were abutted against these posts (Figure 18). These may have possessed a structural purpose for the masonry wall as well as acting as an upright on which to batten the side walls. At the point at which the walls begin to slope inwards a horizontal beam was laid along the entire length of the wall (Figure 19). In no. 4 and no. 5 this beam is visible on the internal face; on no. 3 it is visible on the external face; on no. 2 it is concealed, passing through the centre of the wall. On no. 3, no. 4 and no. 5, a principal rafter is set into the top of the upper, sloping, section of the wall (see Figure 18). It is difficult to define this feature on no. 2, because one side of the wall has fallen, but some indications do exist on the remaining side. Apparently it was not set into the chimney as in the other cottages. Instead, a vertical beam had been set into the front of the chimney which presumably carried the ridge beam (Figure 20). As Figure 17 shows, the chimney of no. 2 slopes back from the vertical. Thus the principal rafter could also have been tied into this vertical beam. A rafter was set into the internal face of the chimneys of no. 2 and no. 3 sloping to the ridge beam at approximately 45° (Figures 20 and 21). This feature was absent on no. 4 and impossible to define on no. 1 and no. 5 because they are now incomplete. On no. 4 and no. 5 the upper part of the wall was recessed 40 mm on the internal face.

Some of these variations are the product of one major constructional difference. On no. 1 and no. 2, the walls are not tied into the chimney. On no. 3 the wall and chimney are tied in up to the height of the horizontal beam (Figure 21). On no. 4 and no. 5 the wall and chimney are tied in from the bottom to the top. In the case of nos. 1–3 the triangular sloping sections were added after the completion of the horizontal beam (Figure 21). In the cases of no. 4 and no. 5 the chimneys and walls were built as a single unit (Figure 19). The evidence from no. 1 is uncertain because of its dilapidated condition. It is clear that in the case of no. 2, with its chimney sloping back from the vertical, and its ridge beam supported by a vertical beam set in the face of the chimney, that this posed the problem of keeping out the rain. The construction of no. 3 indicates an improvement. Building the chimney with a vertical flat surface on the northern side was a better solution, and this was further improved with no. 4 and no. 5 by building the entire wall and chimney as a single unit.

After returning from the field in 1966, the distribution of these differences was tabulated in the form of a sorted matrix. When represented diagrammatically in this fashion indications were that the structures fell into two groups, nos. 1–3 and nos. 4–5, with no. 3 being transitional. In other words, the chimneys could be seriated (Allen 1967:70). With this idea in mind, a further examination was carried out during the 1967 season, and the number of constructional traits was more closely scrutinised and increased. The tabulation of the traits in 1966 had been clumsy because no differentiation was made between the simple presence and absence of traits and the fact that some traits were mutually exclusive. With the 1967 elaboration it became necessary to divide these traits into two tables. In Table 22 the simple presence and absence of some of the traits is represented. Table 23 shows the distribution of mutually exclusive traits. Chimney no. 1 has been excluded from both these tables because of its dilapidation and is discussed separately below. With no. 5, a question mark has been inserted for Trait 6 because there is no direct evidence for this trait. However the probability that it existed is high. 21

Figure 18. Married Quarters round chimney no.3 looking east. The positions of the vertical post, the principal rafter and horizontal beam on the external face are all discernible.

Figure 19. Married Quarters round chimney no. 4 showing horizontal beam revealed on internal face.

Figure 20. Married Quarters round chimney no. 2 showing the position of the vertical beam in the chimney, the internal sloping rafter hole and the separate triangular section of the upper part of the wall on right, now lost on the left.

Figure 21. Married Quarters round chimney no. 3 showing internal sloping rafter hole and the separate triangular sections of the upper parts of the wall. A hole for the ridge beam is discernible in the upper chimney. 22

Table 22. Distribution of architectural traits on four married quarters’ chimneys. 1: vertical wall posts abutted to each end of standing wall. 2: rafter hole at 45º set into internal face of chimney. 3: vertical beam set in internal face of chimney. 4: ridge beam hole set in internal face of chimney. 5: sloping hearth stone at rear of fireplace. 6: internal face of chimney vertical to height of ridge beam. 7: upper section of wall recessed above horizontal beam.

| Trait | No. 2 | No. 3 | No. 4 | No. 5 |

| 1 | X | X | ||

| 2 | X | X | ||

| 3 | X | |||

| 4 | X | X | X | |

| 5 | X | X | X | |

| 6 | X | X | X? | |

| 7 | X | X |

Table 23. Distribution of mutually exclusive architectural traits on four married quarters’ chimneys. 1a: Chimney constructed before wall. 1b: Chimney constructed simultaneously with upper wall. 2a: Chimney at rear angled inwards from ground level. 2b: Chimney at rear vertical to height of horizontal beam then angled inwards. 3a: Chimney not tied into wall at any point. b: Chimney tied into wall to height of horizontal beam. 3c: Chimney tied into wall to the total height. 4a: Horizontal beam concealed. 4b: Horizontal beam visible on external face. 4c: Horizontal beam visible on internal face. 5a: Principal rafter in centre of top of wall not tied into chimney. 5b: Principal rafter in centre of top of wall, tied into chimney. 5c: Principal rafter in centre of wall, tied into chimney, with raised internal edge. 5d: Principal rafter at rear of wall, tied into chimney.

| Trait | No. 2 | No. 3 | No. 4 | No. 5 |

| 1a | X | X | ||

| 1b | X | X | ||

| 2a | X | X | ||

| 2b | X | X | ||

| 3a | X | |||

| 3b | X | |||

| 3c | X | X | ||

| 4a | X | |||

| 4b | X | |||

| 4c | X | X | ||

| 5a | X | |||

| 5b | X | |||

| 5c | X | |||

| 5d | X |

VMQ chimney no. 1

Although this structure had been virtually demolished by a falling tree, certain characteristics could be distinguished. As with no. 2 and no. 3, no. l was constructed with vertical wall posts; as with no. 2 the chimney was not tied into the wall. An apparent difference between no. 1 and all the other examples is that the chimney does not slope in at the rear (its present height exceeds the height at which the horizontal beam would have been employed). This variation, with the buttress chimney remaining vertical at the rear, while differing from the other examples is not atypical, as both types are recorded in Cornwall.

There is evidently a correlation in the positioning of the horizontal beam and the vertical side posts. On no. 2 the side post is in the centre and the horizontal beam passes through the centre of the wall; on no. 3 the side post is set at the rear edge of the wall while the horizontal beam is visible on the external face. On no. 1 the side post is also set at the rear of the wall, but evidence for the presence or absence of the horizontal beam is now lost. On no. 4 and no. 5 the horizontal beam is visible on the internal face and no evidence of side posts remains. Certainly they did not abut the wall as in the case of no. 1, no. 2 and no. 3.

The function of the horizontal beam is uncertain. However, in cottages no. 2 and no. 3 it may have helped stabilise the walls while the construction of the chimneys was completed. The beams projecting forward in no. 4 and no. 5 may have served as mantelpieces.

CONCLUSION

Represented diagrammatically in the form of a sorted matrix, the observed differences permit the division of the chimneys into two groups; nos. 1–3 and nos. 4–5. No. 3 appears to be a transitional example sharing the traits of both groups, but being more closely aligned with no. 1 and no. 2. Only two traits are universal, the horizontal beam and the principal rafter, which was needed to secure the purlins. However this trait suggests a continual improvement in technique from no. 2 to no. 5.

No. 3 has been grouped with no. 1 and no. 2 because its chimney was built before the upper walls, and this constitutes the most significant constructional difference. Yet no. 3 also stands somewhat apart from this group, because its builder had the foresight to keep the internal face of the chimney vertical and to insert the ridge beam into the chimney. The upper wall sections were added more efficiently and neatly in no. 3 than in no. 2, and in general the former structure is more regular and neatly built, and in this respect more closely resembles no. 4 and no. 5.

Several assumptions can be made on the basis of these observations. An obvious grading in constructional techniques and efficiency of building is demonstrated between nos. 1–2, no. 3, and nos. 4–5. While three different builders could have been responsible for these groups, the first garrison consisted of 40 marines, and as the building of these cottages would have formed part of official duties, it seems probable that if the project was a single enterprise, it would have been directed by one person rather than three (and much less five people). Thus the differences are best seen as a function of increasing expertise through time.

Even accepting this seriation it is impossible to demonstrate with certainty the priority of chimney construction. That said, since the settlement lasted only 11 years it is unlikely that there was a degeneration rather than an improvement in the efficiency of building techniques and construction. If all the chimneys are the work of a single builder, it is improbable that he became increasingly inefficient. More probable is that he was inexperienced to begin with and learned by experience. An unlikely alternative is that an experienced builder built no. 4 and no. 5 and that nos. 1–3 were imitations by someone less experienced. However it is likely that the explanation requiring the fewest assumptions is the correct one and that these chimneys reflect the sort of improvisation that attended this attempt at colonisation.

So far only one other example of this semi-circular buttress chimney has been located in Australia on Winnininnie Station in South Australia (pers. comm. Robert Edwards, South Australian Museum) although more might still exist in those areas which were extensively settled by Cornishmen in the nineteenth century. One pictorial representation of a round chimney at Glenelg in South Australia can be dated 1836–38 (Wallace NLA MS.179). It is possible that this chimney and the Port Essington examples reflect a common origin, for some of the marines used to establish Port Essington had been previously stationed in South Australia (Adm. 53/88: 23Alligator’s log 20.7.1837 to 13.2.1843; Pasco 1897:89). These cottages are mentioned by D’Urville (1841–55) who visited the settlement in April 1839, but no specific numbers of cottages or descriptions are recorded. The use of bricks indicates an earliest date of 1840 (see Chapter 8). However on the evidence available, both historical and archaeological, it seems likely that all these chimneys were completed before the first garrison was relieved in 1844.

VMQ excavations

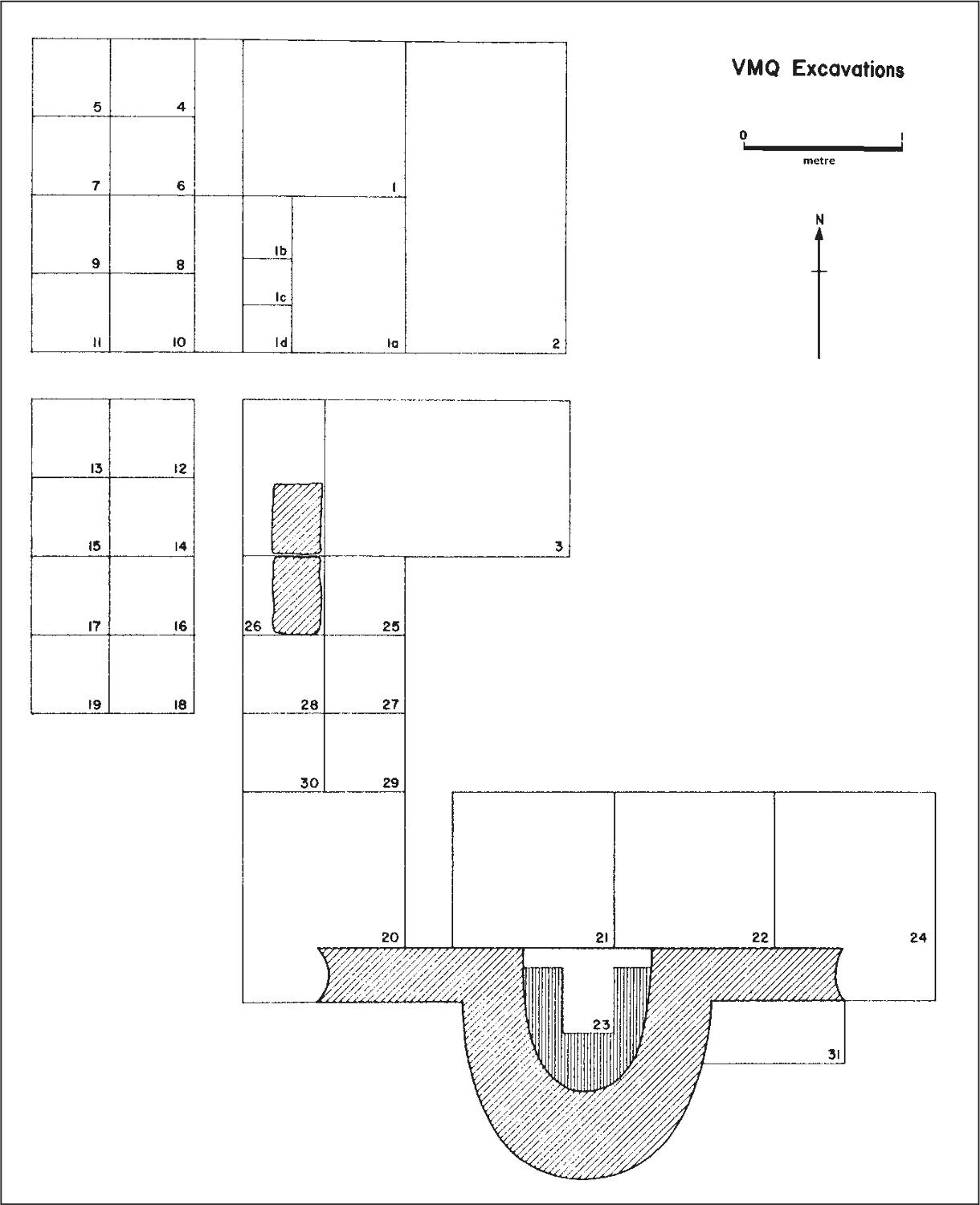

Excavations were begun in the house floor of chimney no. 2 to determine the structure of the floor and its precise measurements by locating post holes, and delineating the extent and composition of the flooring material (Figure 22). It was hoped further to contrast the finds from this type of dwelling with other house floors in the settlement. This particular floor was chosen because the chimney and the hearth were intact and because two squared stones, interpreted as a doorstep, were visible in the line of the western wall; this floor also appeared to be free of major tree root disturbance.

Figure 22. Married Quarters round chimney no 2 ground plan, showing excavation units in relationship to the chimney.

An area measuring 1 m by 2 m was excavated at the north-western corner, and was located so that a visible mound that reflected the corner of the floor fell within it. This excavation was designated VMQ/1. Two further areas, VMQ/2 and VMQ/3 were also opened (see Figure 21). In VMQ/1 and VMQ/2 a hard clay floor, sloping upwards towards the south was encountered 500 mm from the north edge of the excavations. Some small glass flakes had been located on the western side of VMQ/1 (as far as had been excavated) and similar flakes had appeared in the western extreme of VMQ/3, so it was decided to divide the remaining square metre of VMQ/1 and excavate the section on the western extreme, which appeared to be outside the building line, in smaller units and in two spits, and contrast this with the remaining section of VMQ/1 also excavated in two spits. These areas were designated VMQ/1a, /1b, /1c and /1d as shown on the ground plan. VMQ/1b became 400 mm by 300 mm, while VMQ/1c and VMQ/ 1d were each 300 mm by 300 mm. Table 24 shows the numbers of pieces of glass for these areas.

This distribution demonstrated that the heavy concentration of glass occurred outside the building line. As well, the combined area of /1b, /1c and /1d is less than half that of 1/a, making the distinction between deposition inside the house and that outside the house even stronger.

While the northern edge of the clay was quite distinct, the western edge, both in VMQ/1 and VMQ/3, was more indistinct, grading in colour from the red clay on the eastern side, to black soil on the western side. No definite post holes were discernible in the areas uncovered, with the possible exception of a discontinuity in the horizontal section of VMQ/1 at the western extreme of the northern floor line (that is, the point that probably marks the north-west corner of the building). However as this was also associated with major root disturbance it could not positively be identified as a posthole.

An examination of the glass from VMQ/1b, /1c and /1d indicated that much of it could be classified as probably having been utilised by Aborigines. The initial field sorting of the material put 57.4% of the glass from this area in this category. This immediately posed a new possibility that the area outside the building represented a flaking floor, an area for the manufacture of glass implements by the Aborigines. In order to test this hypothesis an area 2 m by 1 m was excavated to the west of VMQ/1 and separated from it by a 300 mm baulk. To gain maximum control of the material this area was excavated in 500 mm squares (VMQ/4 to VMQ/11) and in two spits down to sterile sand. The maximum depth of deposit above the sterile sand in these squares was 210 mm, the minimum, 140 mm. Cultural material was recovered throughout the deposit. A total of 256 pieces of glass was recovered from these eight squares, of which 52.8% was initially sorted as probably utilised by Aborigines. A further area consisting of eight 500 mm squares was excavated (VMQ/12 VMQ/19) and produced significantly less glass (87 pieces) of which 56.3% was classified as probably utilised by Aborigines. In addition two pieces of ground ochre, three stone flakes, and one stone implement were recovered from these areas. The stone implement was reconstructed from five pieces of slate and appears to be the heavily step-flaked butt of a broken spear point. This type has not been recorded before in excavations or collections from Arnhem Land, where the predominant form of 24stone spearhead is the Leilira blade. The only parallels are two similar implements in the Port Essington collection, described below (Chapter 5).

Following this diversion it was decided to excavate series of squares across the hearth area in front of the standing southern wall of the building. The first of these squares, VMQ/20 was begun outside the supposed line of the building and was extended to the foot of the western end of this wall where traces of plaster and tooled stones indicated the presence of a post. Again however, no indications of a posthole were discernible from colour change in the soil, although from traces of wall plaster below ground level, it was apparent that the post had been set in the ground. Twenty-two pieces of glass were recovered at the western end of this square. Inside the line of the house the clay floor proved to be much better defined, covered by a thin charcoal layer presumed to be the reflection of the destruction of the house at the time the settlement was abandoned. The floor in this area consisted of packed clay with criss-cross wear lines running through it, and this continued through VMQ/21 and VMQ/22. The nature of the topsoil in VMQ/20 had changed from the northern end of the building and here contained shells amongst the loose black soil. A 300 mm baulk was left between VMQ/20 and VMQ/21. Here again a loose black deposit containing shell, iron, glass and pottery was found above the clay floor, being deeper at the southern end and extending into the fireplace. A similar deposit, but decreasing in depth, was found in VMQ/22 above the clay floor, and also in VMQ/23, in the fireplace above the hearth-stones. VMQ/24 extended the excavation beyond the building line and was extended to investigate the eastern end of the stone wall, but again no colour change indicated where the post had stood. Finds in this area were few.

The stratigraphic evidence in the hearth area established that almost all the finds related to occupation by Aborigines after the European evacuation. Because of the sharp division of finds of glass on the western side of the building it is reasonable to infer however, that this latter deposit was laid down at a time when the western wall was still standing, i.e. while the settlement was occupied by Europeans. Apparently the Aborigines began to use the remaining southern stone wall and chimney as a form of rock shelter after the abandonment and destruction of the house, and at this time the midden deposit grew in front of it.

Six 500 mm by 500 mm squares (VMQ/25-VMQ/30) were excavated to join the western end of VMQ/3 and VMQ/20 in order to investigate further the relationship of the areas within and outside the supposed line of the building. Results in terms of finds and stratigraphy paralleled the earlier results.

VMQ/31 was excavated to investigate the foundations of the standing wall. These extended 430 mm (two courses of cemented stone) below present ground level and were of the same width as the wall above ground level. The only find in this area was a single nail.

Finally the baulk separating VMQ/1 and VMQ/4 to VMQ/11 was excavated in the hope of increasing the sample of glass. Indeed, the area proved extremely rich, producing 100 pieces of glass, 25 pieces of pottery, and one European gun-flint.

Finds which definitely could be associated stratigraphically with the European occupation of the house were extremely rare and perhaps this reflects the tidiness of the family who lived there. The use of a broom appears to be the best explanation of the criss-cross lines which were found in the area of the hearth. The metal frame of a brooch from this site-unit was the only clearly feminine artefact excavated in the entire settlement, so that it was satisfying that it was found in a building designated as married quarters. The recovery of pottery and glass from the cliff top and slope opposite these houses suggests that most of the refuse from these houses was dumped in this area. No suggestion of internal walls or partitions was recognised in the excavated house floor.

Table 24. Distribution of glass in selected squares inside and outside of married quarters house no. 2.

| Spit | VMQ/1A | VMQ/1B | VMQ/1C | VMQ/1D |

| 1 | 33 | 16 | 22 | |

| 2 | 4 | 10 | 20 | |

| TOTAL | 4 | 43 | 36 | 22 |

Table 25. Glass from VMQ excavations according to type: number and weight in grams.

| TYPE A | TYPE B | TYPE C | TOTAL | |||||

| No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | |

| VMQ/1/1 | 20 | 214.0 | 17 | 87.3 | 37 | 301.3 | ||

| VMQ/1A/2 | 4 | 7.3 | 4 | 7.3 | ||||

| VMQ/1B/1 | 21 | 69.4 | 12 | 35.1 | 33 | 104.5 | ||

| VMQ/1C/1 | 13 | 21.3 | 3 | 5.0 | l 6 | 26.3 | ||

| VMQ/1B/2 | 5 | 22.6 | 5 | 21.1 | 10 | 43.7 | ||

| VMQ/1C/2 | 15 | 19.5 | 5 | 15.0 | 20 | 34.5 | ||

| VMQ/1D/1 | 4 | 11.5 | 18 | 16.5 | 22 | 28.0 | ||

| VMQ/2/2 | 2 | 2.3 | 2 | 2.1 | 4 | 4.4 | ||

| VMQ/3/1 | 18 | 49.0 | 22 | 30.1 | 40 | 79.1 | ||

| VMQ/4/1 | 4 | 13.9 | 7 | 12.1 | 11 | 26.0 | ||

| VMQ/4/2 | 4 | 28.8 | 13 | 20.5 | 17 | 49.3 | ||

| VMQ/5/1 | 3 | 9.5 | 4 | 5.0 | 7 | 14.5 | ||

| VMQ/5/2 | 5 | 8.9 | 7 | 4.5 | 12 | 13.4 | ||

| VMQ/6/1 | 9 | 65.8 | 13 | 17.1 | 22 | 82.9 | ||

| VMQ/6/2 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.0 | 2 | 2.9 | ||

| VMQ/7/1 | 3 | 6.1 | 4 | 5.9 | 7 | 12.0 | ||

| VMQ/7/2 | 4 | 11.5 | 7 | 17.5 | 11 | 29.0 | ||

| VMQ/8/1 | 47 | 116.9 | 26 | 47.1 | 73 | 164.0 | ||

| VMQ/8/2 | 4 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.9 | 5 | 5.1 | ||

| VMQ/9/2 | 7 | 85.4 | 3 | 0.9 | 10 | 86.3 | ||

| VMQ/10/1 | 28 | 54.5 | 19 | 41.6 | 47 | 96.1 | ||

| VMQ/10/2 | 1 | 3.4 | 1 | 3.4 | ||||

| VMQ/11/1 | 7 | 12.1 | 2 | 7.1 | 9 | 19.2 | ||

| VMQ/11/2 | 16 | 51.0 | 7 | 26.8 | 23 | 77.8 | ||

| VMQ/12/1 | 2 | 8.6 | 1 | 0.8 | 3 | 9.4 | ||

| VMQ/12/2 | 8 | 38.7 | 2 | 3.4 | 10 | 42.1 | ||

| VMQ/13/1 | 3 | 15.0 | 3 | 2.5 | 6 | 17.5 | ||

| VMQ/13/2 | 2 | 6.7 | 6 | 4.5 | 8 | 11.2 | ||

| VMQ/14/1 | 2 | 3.5 | 2 | 3.5 | ||||

| VMQ/14/2 | 1 | 1.5 | 3 | 3.0 | 4 | 4.5 | ||

| VMQ/15/1 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | ||||

| VMQ/15/2 | 3 | 15.8 | 4 | 7.8 | 7 | 23.6 | ||

| VMQ/16/1 | 2 | 61.0 | 4 | 5.0 | 6 | 66.0 | ||

| VMQ/17/1 | 5 | 9.6 | 6 | 7.5 | 11 | 17.1 | ||

| VMQ/17/2 | 5 | 16.4 | 5 | 16.4 | ||||

| VMQ/18/1 | 2 | 1.9 | 2 | 1.9 | ||||

| VMQ/18/2 | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.0 | ||||

| VMQ/19/1 | 15 | 126.5 | 6 | 9.2 | 21 | 135.7 | ||

| VMQ/20/1 | 14 | 146.7 | 8 | 38.9 | 22 | 185.6 | ||

| VMQ/21/1 | 10 | 121.3 | 60 | 269.9 | 70 | 391.2 | ||

| VMQ/22/1 | 9 | 31.3 | 1 | 13.1 | 16 | 23.2 | 26 | 67.6 |

| VMQ/23/2 | 2 | 11.2 | 2 | 23.8 | 4 | 35.0 | ||

| VMQ/24/1 | 1 | 3.0 | 2 | 5.3 | 3 | 8.3 | ||

| VMQ/25/1 | 2 | 38.4 | 2 | 15.8 | 4 | 54.2 | ||

| VMQ/26/1 | 2 | 14.2 | 11 | 32.9 | 13 | 47.1 | ||

| VMQ/28/1 | 4 | 58.6 | 6 | 64.8 | 10 | 123.4 | ||

| VMQ/29/1 | 1 | 10.7 | 2 | 2.3 | 3 | 13.0 | ||

| VMQ/30/1 | 2 | 9.8 | 2 | 9.8 | ||||

| VMQ/32/1 | 22 | 234.4 | 1 | 20.0 | 23 | 116.4 | 46 | 370.8 |

| VMQ/32/2 | 3 | 25.4 | 2 | 10.0 | 5 | 35.4 | ||

| VMQ/33/1 | 12 | 31.1 | 1 | 7.9 | 7 | 44.7 | 20 | 83.7 |

| VMQ/33/2 | 16 | 43.7 | 13 | 34.4 | 29 | 78.1 | ||

| Surface | 1 | 21.8 | 1 | 21.8 | ||||

| TOTAL | 388 | 1957.8 | 14 | 98.9 | 386 | 1130.8 | 788 | 3187.5 |

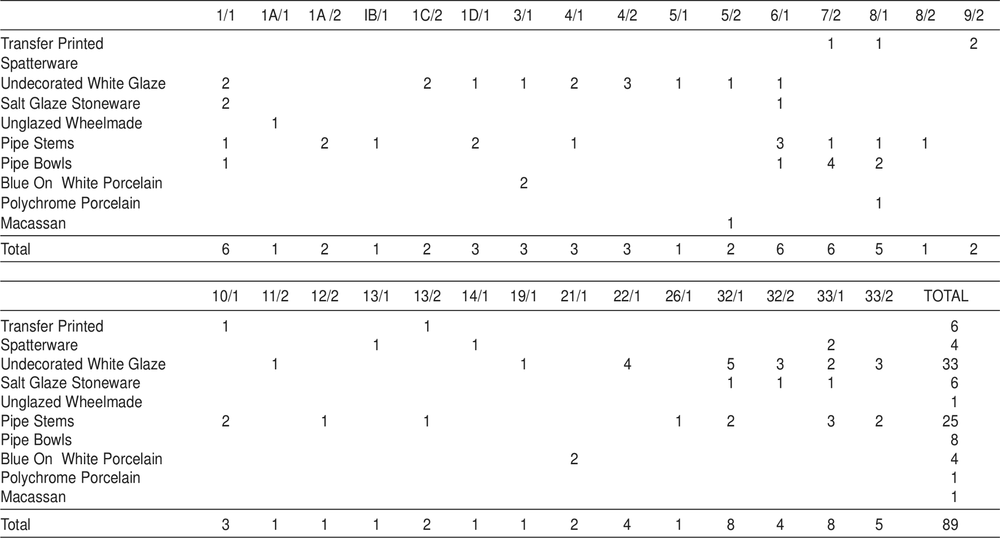

Table 26. Pottery counts from VMQ excavations according to type. Only squares/spits with pottery are shown in table.

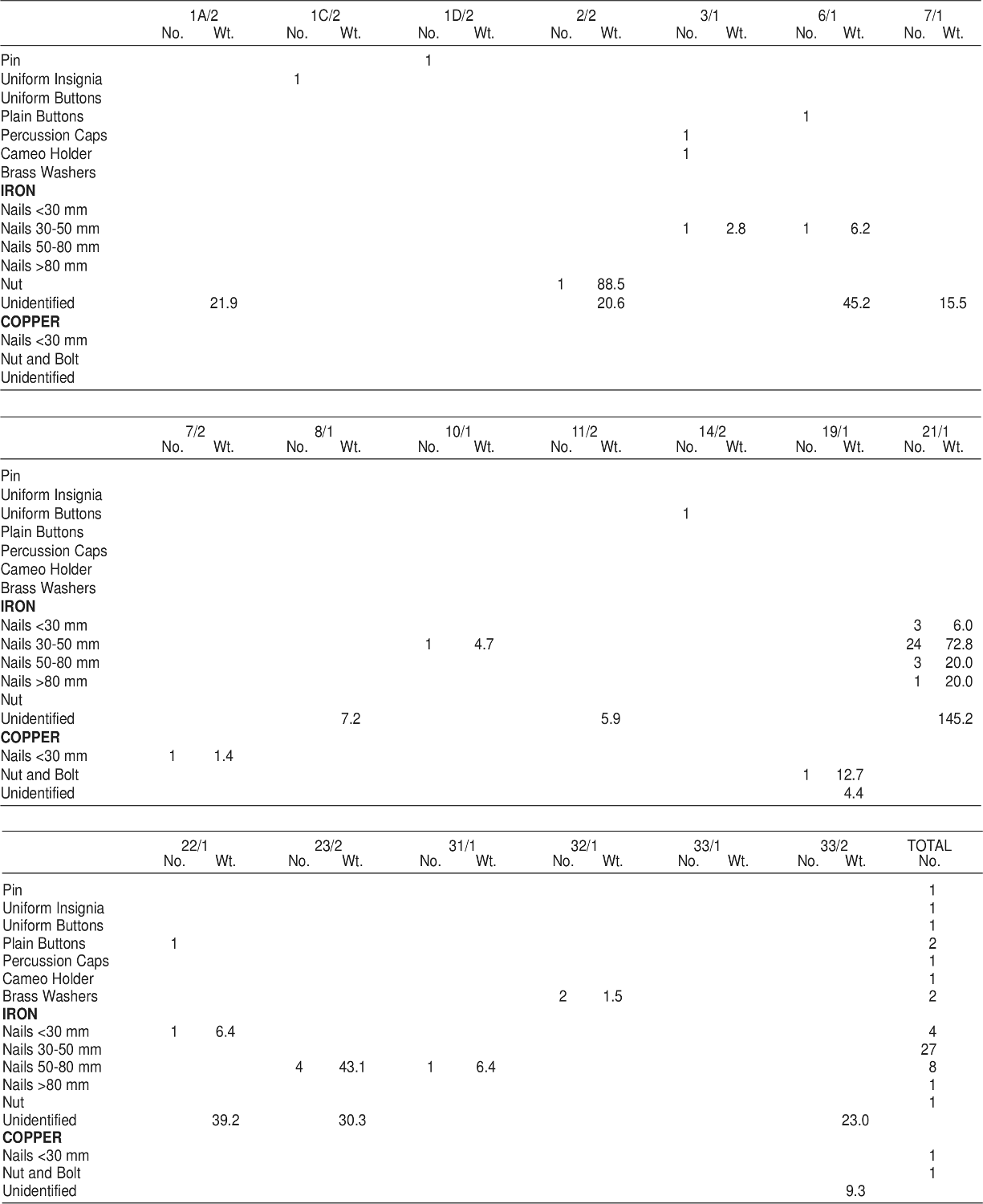

Table 27. Metal from VMQ excavations. Weight in grams. Only squares/spits with metal are shown in table.

Table 28. Aboriginal and European stone from VMQ. Weight in grams. Only squares/spits with pottery are shown in table.

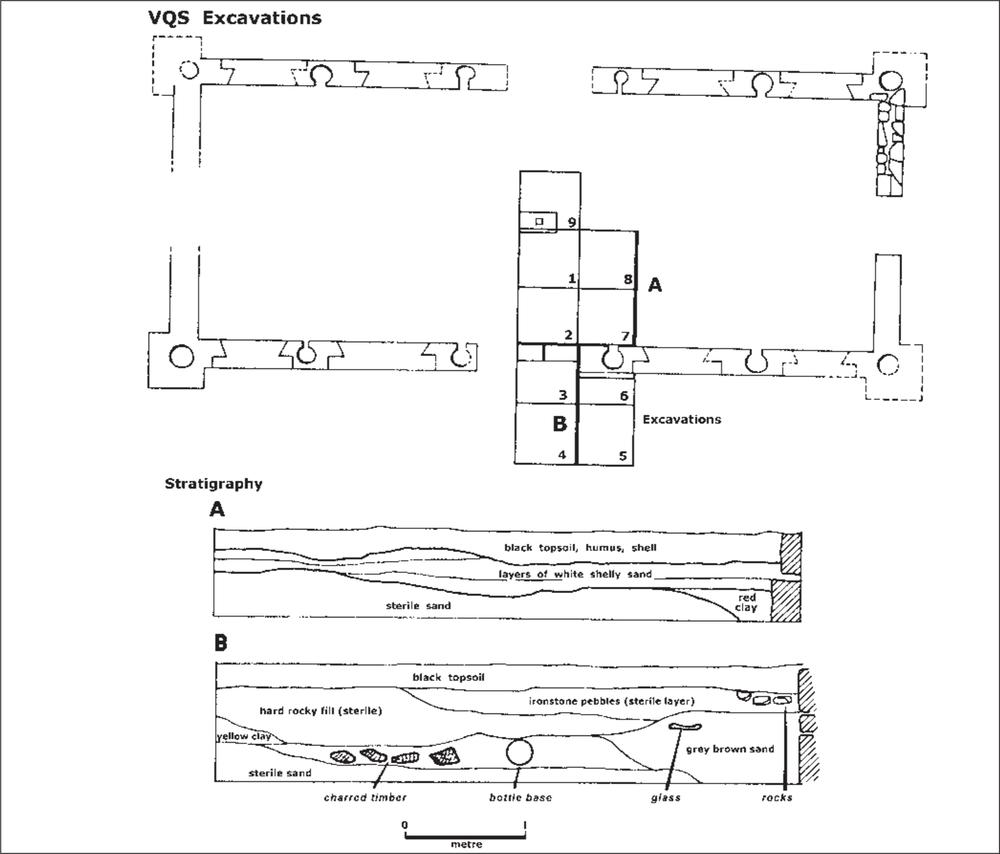

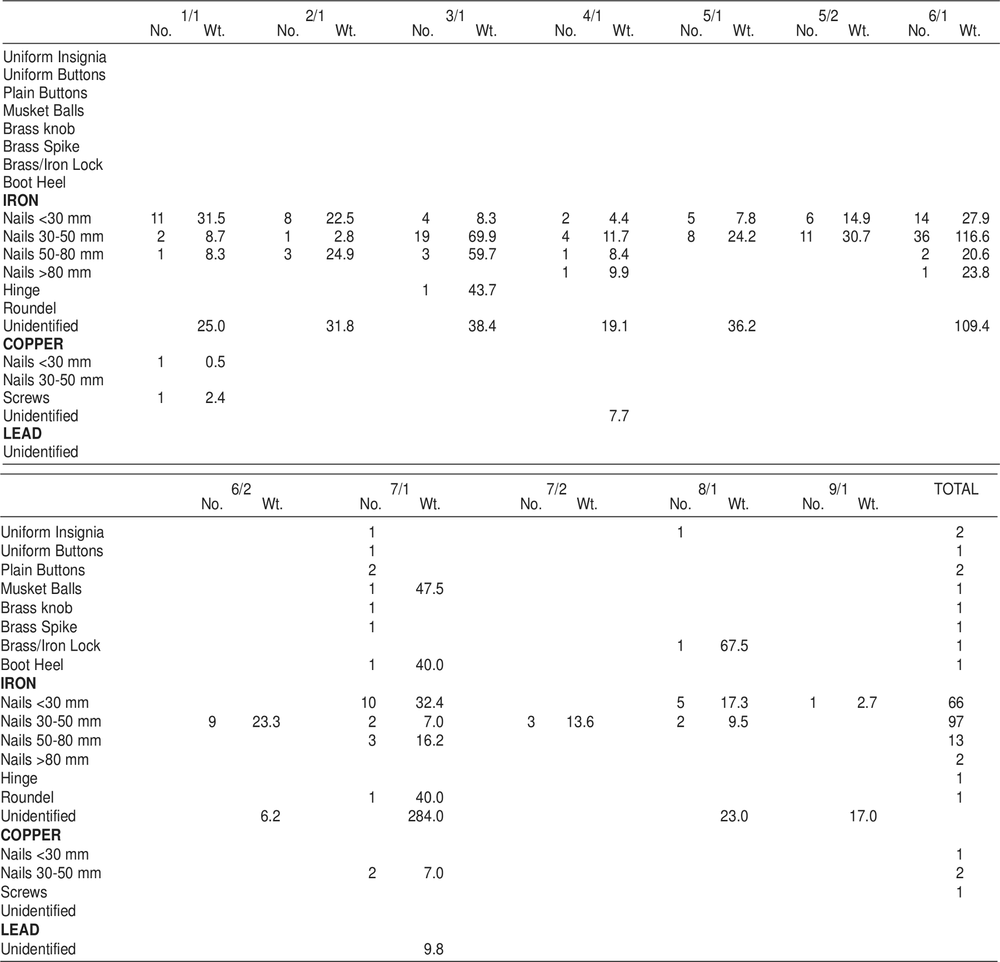

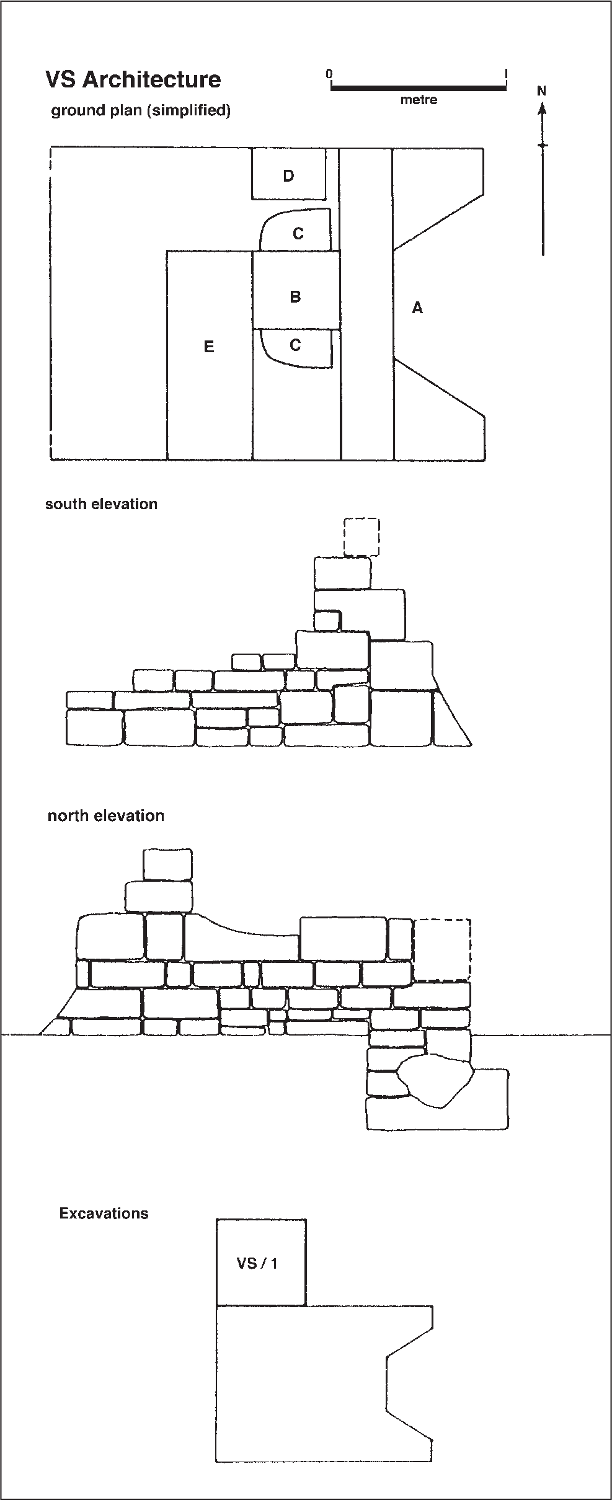

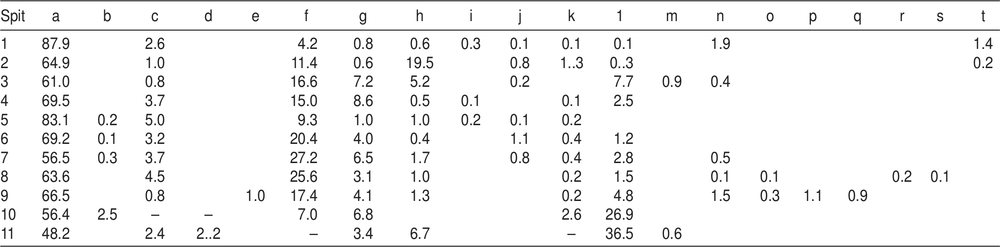

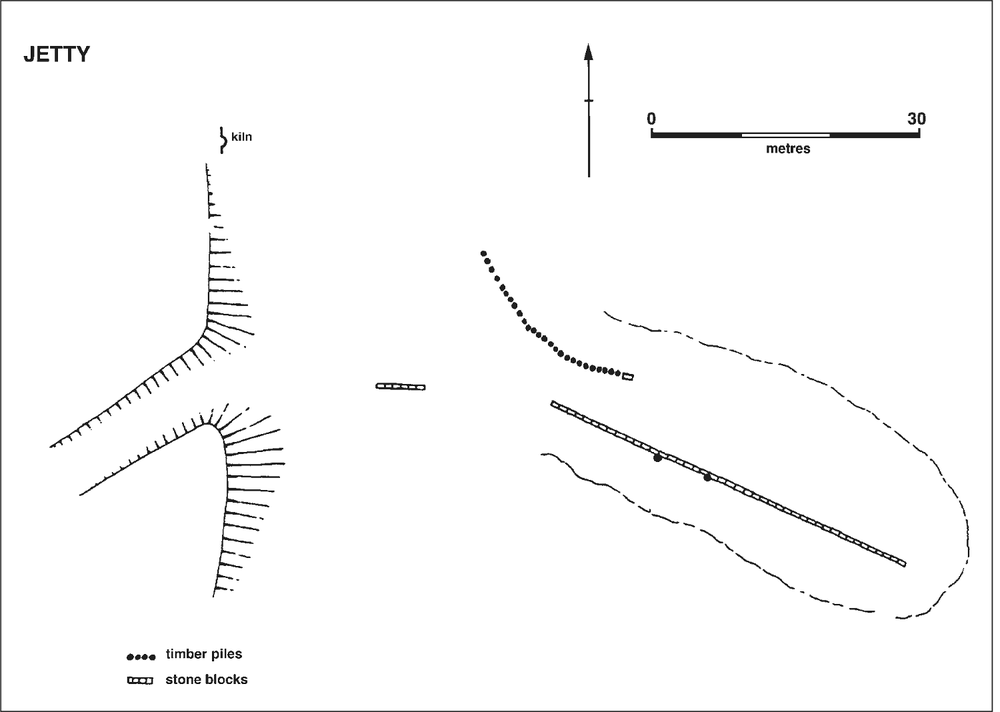

QUARTERMASTER’S STORE (Code prefix VQS)

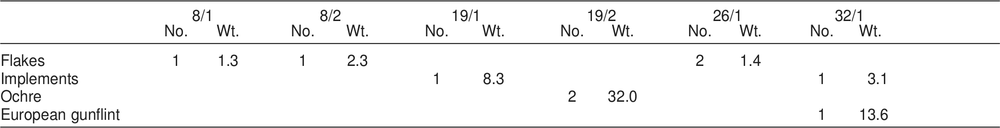

VQS architecture

The remains of the quartermaster’s store were located at the northern end of the square, which had regenerated into a forest of monsoonal vegetation. These consisted of the stone walls, standing to window height (approx. 1.2 metres), built in a rectangular shape with entrances in the centre of each wall (Figure 23).

Figure 23. Quartermaster’s Store (VQS): ground plan and elevations.

From contemporary paintings this building was identified as one of the prefabricated buildings which had been brought from Sydney. Originally it had been constructed on c. 2.5 m high wooden piles, which were afterwards enclosed in the stone foundations which now remain. When the enclosure took place the wall, consisting of a double thickness of rough-hewn blocks with rubble and cement fill, was built around the existing wooden piles, and although these have long since disappeared, the gaps in the stonework which they filled show their positioning and their variation in size (Figure 24). Except for the four corner posts, a gap was deliberately left on the internal face of the wall adjacent to each wooden pile, but the reason for this is uncertain.

Excavations revealed a stone post-support in the centre of the floor and it is supposed that this is the centre of the long axis of the building. In this respect this building is similar to Store D (see below). Also the external corners were buttressed as in Store D, and the flooring was again of layers of shell, although in places these were separated from the sterile sand by a layer of red clay. The excavations through the southern doorway revealed a stone doorstep. 27

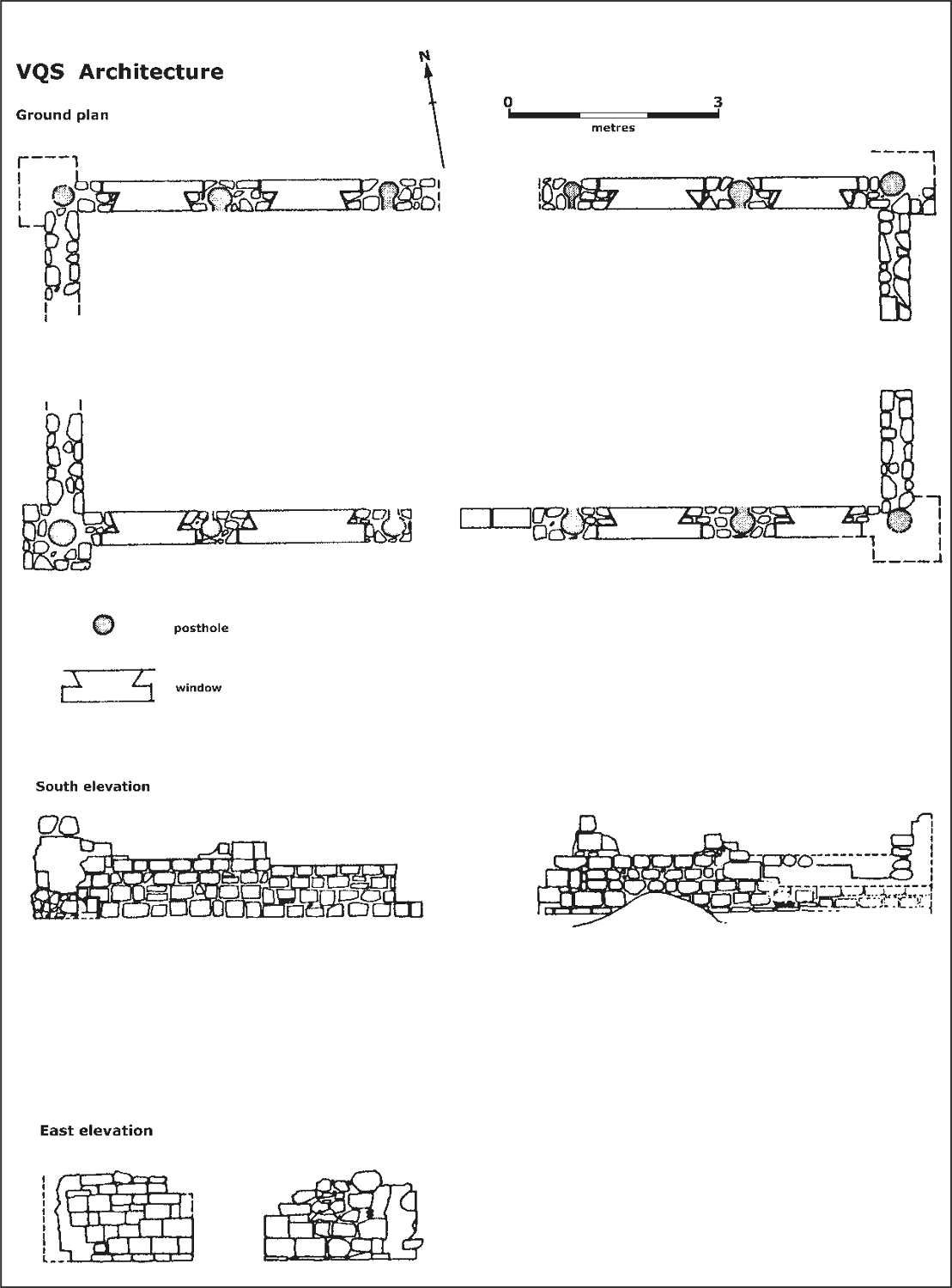

Figure 24. Part of the standing lower storey of VQS. The tree is growing in the space provided by the original wooden pile, later mostly enclosed by the stone wall.

Access to the upper storey was external, consisting of wooden steps at the eastern end; no evidence of internal stairs was revealed, although this may be the result of insufficient excavation.

The remains of four windows were discernible in each of the long walls of the lower storey (Figure 22). These were of an intricate shape and were probably provided with wooden sills.

VQS excavations

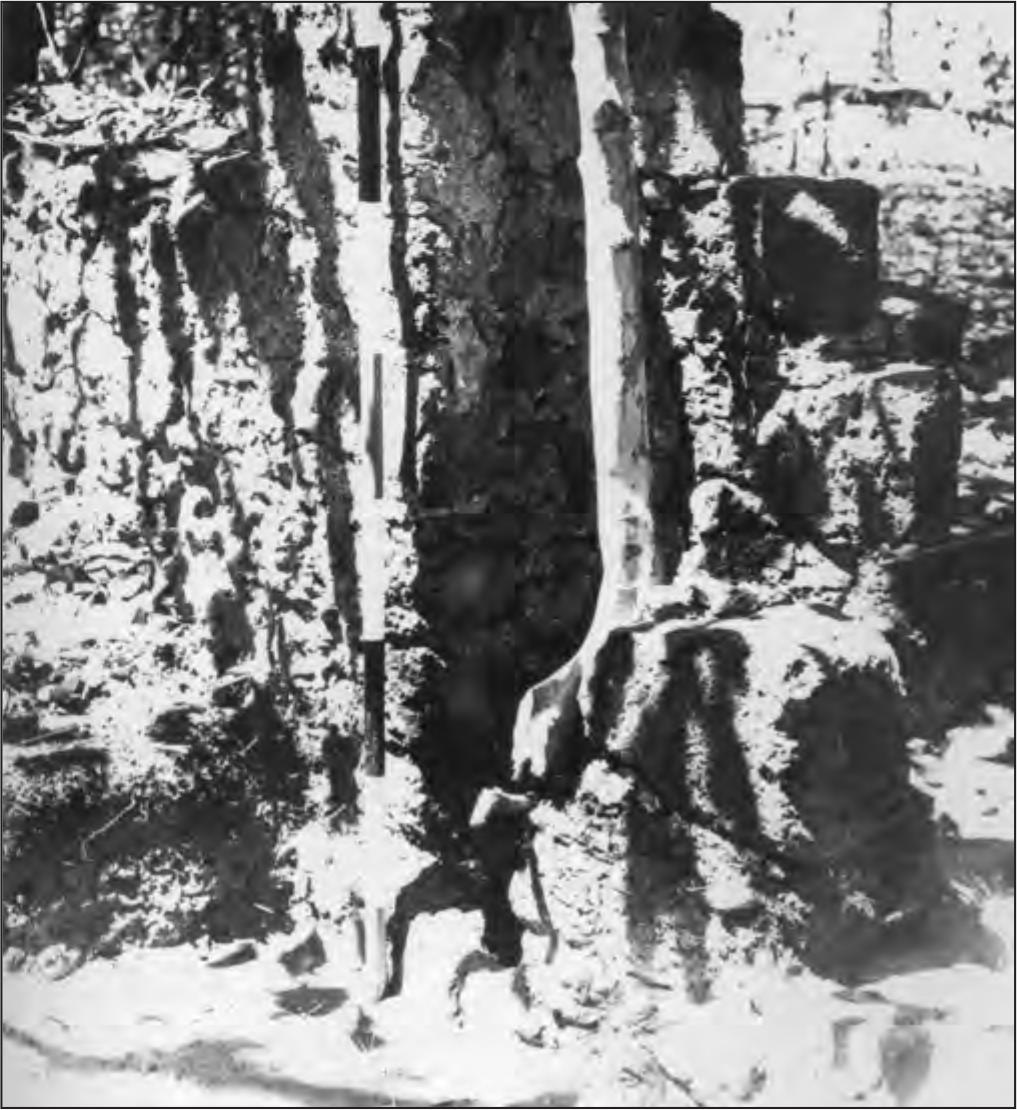

An area measuring 2 m by 4 m was excavated in metre squares (VQS/1–VQS/8), in order to reveal the doorway in the southern wall and to examine the deposit inside and outside the building (Figure 25). Excavations in VQS/1 revealed the edge of a stone block in the centre of the house floor, and an additional metre square, VQS/9 was excavated to uncover this block. The excavations in VQS/1 were divided into two spits, but since it appeared that no differentiation could be made in the deposit within the house, the remaining internal squares were excavated as single units with the exception of VQS/7 where a post hole in the wall was taken out as a separate spit. The squared stone in VQS/9 proved to be an internal post support similar to those found in Store D, measuring 600 mm by 400 mm with a 100 mm square notch cut in the top to a depth of 40 mm.

Figure 25. VQS ground plan showing position of the excavation and stratigraphic sections.

28The stratigraphy within the building was the same in each square and consisted, as in other buildings in the settlement, of a basal deposit of sterile sand over which red clay was lain down, followed by successive layers of fine beach shell. The post hole in the wall was excavated to a depth of 300 mm, at which point no more deposit could be removed because of the difficulty of excavation, although sterile sand had not been reached.

Excavations in VQS/3 and VQS/6 uncovered a stone doorstep made of hewn stone blocks cemented in two courses. Beyond this, in VQS/3, after passing through the topsoil deposit, a roughly level surface of small broken stones was encountered, which extended a metre from the building line. VQS/5 and VQS/6 were then excavated in two spits, the top spit uncovering the deposit above the ‘path’ and the second spit passing through the floor down to the sterile sand.

After passing through the ‘path’ deposit, which was sterile, it was found that the level underneath contained European cultural deposit for a further 150–200 mm before the basal sterile layer was encountered. Section VQS/5–VQS/6 west wall (Figure 25) indicates the stratigraphy, showing the base of a bottle, and burnt timbers in situ. Whether this constitutes an earlier building or an earlier phase of the present building is impossible to demonstrate archaeologically, but it is probably associated with the period before the lower section of the building was encased in stone. The stone doorstep appears to have been built with little or no excavation of the ground beneath it, and the interior filled with clay and shell flooring to the height of the step. At the same time, perhaps, the immediate surrounds of the building were levelled to the height of this stone ‘path’.

As in the case of other buildings in the settlement, rather more glass and pottery was recovered from the immediate exterior of the building than from within it. Metal was found throughout the excavation, but VQS/7 yielded the greatest amount of ‘exotic’ metal – uniform insignia, several buttons, a large brass spike and a brass knob. In VQS/8 a brass and iron door lock and the chin-strap terminal of an officer’s shako were recovered.

Of the glass recovered from the excavation, 13.6% was sorted primarily as possibly utilised by Aborigines, and this material was found throughout the deposit. In other areas this material was located predominantly outside houses. Its presence inside the quartermaster’s store might indicate that the Aborigines occupied the building while the settlement was still in existence, since it is known that the building fell into such disrepair that it was no longer occupied by the garrison before the settlement was abandoned (Brierly 1848 ML A501–4:14 November). Alternatively the area could have been used by the Aborigines before the lower section was enclosed.

Table 29. Glass from VQS excavations according to type: number and weight in grams.

| AREA | TYPE A | TYPE B | TYPE C | TOTAL | ||||

| No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | |

| VQS/1/1 | 1 | 3.2 | 13 | 19.4 | 14 | 22.6 | ||

| VQS/2/1 | 4 | 20.1 | 27 | 67.5 | 31 | 87.6 | ||

| VQS/3/1 | 16 | 85.4 | 38 | 59.3 | 54 | 144.7 | ||

| VQS/4/1 | 21 | 82.1 | 1 | 15.2 | 116 | 209.1 | 138 | 306.4 |

| VQS/5/1 | 10 | 57.0 | 48 | 110.0 | 58 | 167.0 | ||

| VQS/5/2 | 4 | 19.0 | 1 | 457.5 | 27 | 42.2 | 32 | 518.7 |

| VQS/6/1 | 9 | 52.3 | 80 | 229.5 | 89 | 281.8 | ||

| VQS /6/2 | 6 | 31.4 | 6 | 31.4 | ||||

| VQS/7/1 | 25 | 214.0 | 2 | 28.0 | 95 | 642.5 | 122 | 884.5 |

| VQS/7/2 | 12 | 26.8 | 23 | 138.4 | 35 | 165.2 | ||

| VQS/8/1 | 2 | 3.7 | 28 | 56.5 | 30 | 60.2 | ||

| VQS/9/1 | 3 | 3.5 | 22 | 67.0 | 25 | 70.5 | ||

| TOTAL | 107 | 567.1 | 4 | 500.7 | 523 | 1672.8 | 634 | 2740.6 |

Table 30. Pottery counts from VQS excavations according to type. Only squares/spits with pottery are shown in table.

| 1/1 | 2/1 | 3/1 | 4/1 | 5/1 | 6/1 | 7/1 | 9/1 | TOTAL | |

| Transfer Printed | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 26 | ||

| Featheredge (Blue) | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Saltglaze Stoneware | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Unglazed Wheelmade | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Undecorated White Glaze | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 11 | |||

| Hand Painted | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Pipe Stems | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 12 | |||

| Blue On White Porcelain | 2 | 14 | 4 | 20 | |||||

| TOTAL | 3 | 5 | 16 | 20 | 4 | 18 | 5 | 4 | 75 |

Table 31. Metal from VQS excavations. Weight in grams.

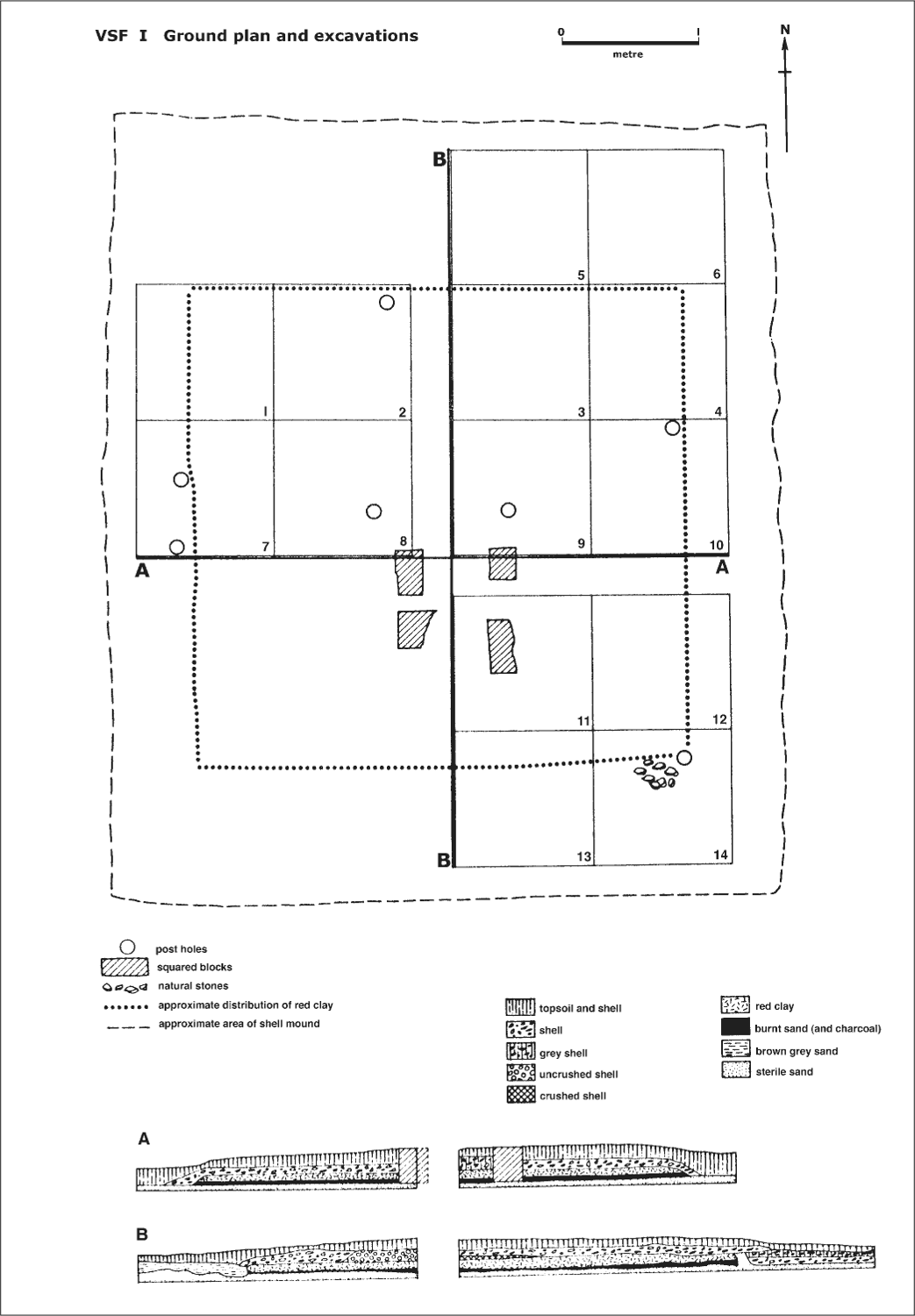

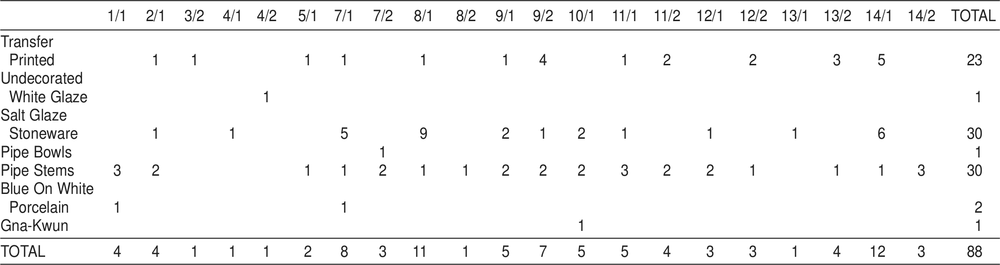

SHELL FLOOR No. 1 (Code prefix VSFI)

Within the pocket of monsoonal vegetation which marks the area of the town square, six mounds were located. These were mostly rectangular or square in plan, standing to a height of only a few centimetres above the surrounding ground level. Because of the dense vegetation, which reduced visibility to several yards, no detailed plan of the localities of these house floors could be drawn without major clearing.

The floor selected for excavation was located 12.6 m south of the bake house. This floor was chosen because it was free of major tree root disturbance and because in the centre of the mound, four squared stone blocks were visible on the surface. This feature was not apparent in any of the other floors located, although similar arrangements of stones may occur below the present ground level in these other examples. In all examples the mounds are flecked with small pieces of shell.

VSF excavations – structure

Fourteen square metres were excavated as shown on the ground plan (Figure 26). Originally it had been hoped to uncover the total area to obtain a complete ground plan of post holes, but time did not permit this.

VSFI/1 was excavated in an attempt to define the western edge of the building at its eastern end. After passing through a layer of topsoil and shell above a layer of shell flooring, a stratum of red clay was encountered at a depth of 180 mm. The material so far excavated was bagged as spit 1, and the remaining deposit excavated to sterile sand as spit 2. The remaining thirteen square metres were excavated in a similar two spit system. On the western side the exact delineation of the clay was unclear at the bottom of spit 1, merging into a grey shelly matrix, but with the removal of spit 2, the edge of the clay became more definite.

After the removal of the upper spit of VSFI/2, a possible post hole was revealed in the north-east corner. Because of the nature of the shell matrix it was impossible to determine post holes in this and subsequent squares in spit 1, but in the red clay deposit, or when contrasted with the sterile yellow sand these holes became obvious.

After leaving a 300 mm baulk, two further squares were excavated to the east to define the eastern edge of the clay, which was located in VSFI/4. VSFI/5 and VSFI/6 were excavated to delineate the northern extreme of the clay, which was found to follow almost exactly the northern face of VSFI/1 to VSFI/4.

Excavations in VSFI/7 revealed two further post holes immediately outside the line of red clay and 500 mm apart. Additional post holes were located in VSFI/8, VSFI/9 and VSFI/10 (Figure 27). In addition, in VSFI/8 and VSFI/9, and later in VSFI/11, three of the four central stone blocks were uncovered and were found to be sitting on the sterile basal deposit, while the subsequent occupation deposit had built up around them. In VSFI/11 a section of the quadrilateral area contained by the stones was excavated, where although the stratigraphy was identical to the other areas uncovered more whole shells were excavated.

In VSFI/14, the seventh and final post hole was located exactly at the junction of the southern and eastern limits of the red clay stratum. Immediately outside the line of the clay, resting on the sterile sand, a rough circle of small stones was uncovered.

VSFI excavations – artefacts

A variety of ceramic, glass and metal objects was recovered throughout the excavations, both within and outside the suggested area of the building floor. Cultural material was present in both the shell and clay deposits throughout the excavations, indicating that the red clay was not merely a base on which the shell was deposited. Among the more exotic finds recorded were two three pronged metal forks, a brass reed from a harmonica, and in VSFI/9 an iron foot, possibly from some sort of brazier. Beneath the red clay in VSFI/10 a stone, similar in shape to the conical pounder of McCarthy’s et al. (1946:68) classification was excavated. This object is made of granite, a material foreign to the region, and there is no reason to doubt that it is an Aboriginal artefact. Of the glass 13.7% was initially sorted as possibly having been utilised by Aborigines, but almost half of this came from the lower spit. Some of these pieces may reflect accidental breakage by shod feet on the compacted floor surface, but some appear to be genuine flaked artefacts. 30

Figure 26. Shell floor no.1. Ground plan showing excavation squares and stratigraphic sections.

Figure 27. VSF I excavations. Stakes indicate positions of postholes.

In addition to the glass, pottery and metal listed in Tables 32-34, one plain 4-hole bone button was recovered from VSFI/1/1 and 55.6 gm of bone. This included cow/buffalo, pig, kangaroo, bird, fish and crab.

Summary of VSFI

The general correlation of post holes and the red clay distribution suggests that the boundaries of the building have been well defined by excavation. That no post hole was discernible at the north-eastern corner is puzzling, and there appears to be no satisfactory explanation for this gap. That the indications were missed during excavation is possible, but in view of the distinctive appearance of the other post holes, this seems unlikely. The two post holes in the western wall are interpreted as an entrance.

The burnt layer between the sterile sand and the red clay may be equated with a similar layer in the officers’ mess (see below) and interpreted to represent the initial clearing of the area by fire (Figure 24, stratigraphy). This interpretation was strengthened by the present excavations. It appears that immediately following the burning off, the clay floor was laid down, sealing the burnt layer. Beyond the area of the clay the remains of the burning subsequently dispersed. If the burning had taken place any considerable time before the introduction of the clay, the stratigraphy could be expected to be the same outside the area of the clay.

The function of the four stones is uncertain, but they were possibly used as a firm base on which to stand some object. It is tempting to associate the iron leg excavated adjacent to these stones with this object. A brazier is perhaps the best suggestion (see Chapter 8) and although the excavations within the area of the stones did not recover any evidence of charcoal pieces, the shell here was largely unbroken, suggesting that this area was not walked upon.

The presence of the Aboriginal artefact beneath the red clay and the pieces of utilised glass in the lower spits indicates the possibility that Aborigines were in this area prior to the construction of the building, and it is tempting in this light to associate the circle of stones excavated in VSFI/14 with a hearth. However this suggestion is necessarily conjectural.

Table 32. Glass from VSFI excavations according to type: number and weight in grams.

| AREA | TYPE A | TYPE B | TYPE C | TOTAL | ||||

| No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | |

| VSF/1/1/1 | 4 | 86.1 | 13 | 24.4 | 17 | 110.5 | ||

| VSF/1/1/2 | 7 | 10.6 | 7 | 10.6 | ||||

| VSF/1/2/1 | 3 | 42.3 | 16 | 34.2 | 19 | 76.5 | ||

| VSF/1/2/2 | ||||||||

| VSF/1/3/1 | 15 | 10.9 | 15 | 10.9 | ||||

| VSF/1/3/2 | 4 | 4.4 | 10 | 20.5 | 14 | 24.9 | ||

| VSF/1/4/1 | 2 | 9.2 | 25 | 48.1 | 27 | 57.3 | ||

| VSF/1/4/2 | 3 | 1.3 | 2 | 2.5 | 5 | 3.8 | ||

| VSF/1/5/1 | 4 | 17.2 | 12 | 16.4 | 16 | 33.6 | ||

| VSF/1/5/2 | 2 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.6 | ||||

| VSF/1/6/1 | 12 | 43.0 | 12 | 43.0 | ||||

| VSF/1/6/2 | 4 | 6.5 | 4 | 6.5 | ||||

| VSF/1/7/1 | 5 | 8.5 | 5 | 8.5 | ||||

| VSF/1/7/2 | 1 | 0.4 | 2 | 9.5 | 3 | 9.9 | ||

| VSF/1/8/1 | 1 | 3.2 | 21 | 24.3 | 22 | 27.5 | ||

| VSF/1/8/2 | 1 | 1.4 | 8 | 11.5 | 9 | 12.9 | ||

| VSF/1/9/1 | 3 | 9.9 | 40 | 57.3 | 43 | 67.2 | ||

| VSF/1/9/2 | 7 | 12.5 | 20 | 41.9 | 27 | 54.4 | ||

| VSF/1/10/1 | 3 | 2.0 | 27 | 39.8 | 30 | 41.8 | ||

| VSF/1/10/2 | 2 | 11.7 | 2 | 11.7 | ||||

| VSF/1/11/1 | 5 | 8.2 | 5 | 8.2 | ||||

| VSF/1/11/2 | 7 | 27.9 | 7 | 9.5 | 14 | 37.4 | ||

| VSF/1/12/1 | 3 | 7.9 | 15 | 24.2 | 18 | 32.1 | ||

| VSF/1/12/2 | ||||||||

| VSF/1/13/1 | 6 | 89.2 | 2 | 58.5 | 13 | 50.5 | 21 | 198.2 |

| VSF/1/13/2 | 1 | 0.3 | 7 | 113.5 | 8 | 113.8 | ||

| VSF/1/14/1 | 4 | 10.3 | 2 | 52.5 | 63 | 58.4 | 69 | 121.2 |

| VSF/1/14/2 | 2 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.0 | ||||

| TOTAL | 57 | 325.5 | 4 | 111.0 | 355 | 688.5 | 416 | 1125.0 |

Table 33. Pottery counts from VSFI excavations according to type.

Table 34. Metal from VSFI excavations. Weight in grams. Only squares/spits with metal are shown in table.

Figure 28. Shell floor no. 2. Ground plan showing excavation and section.

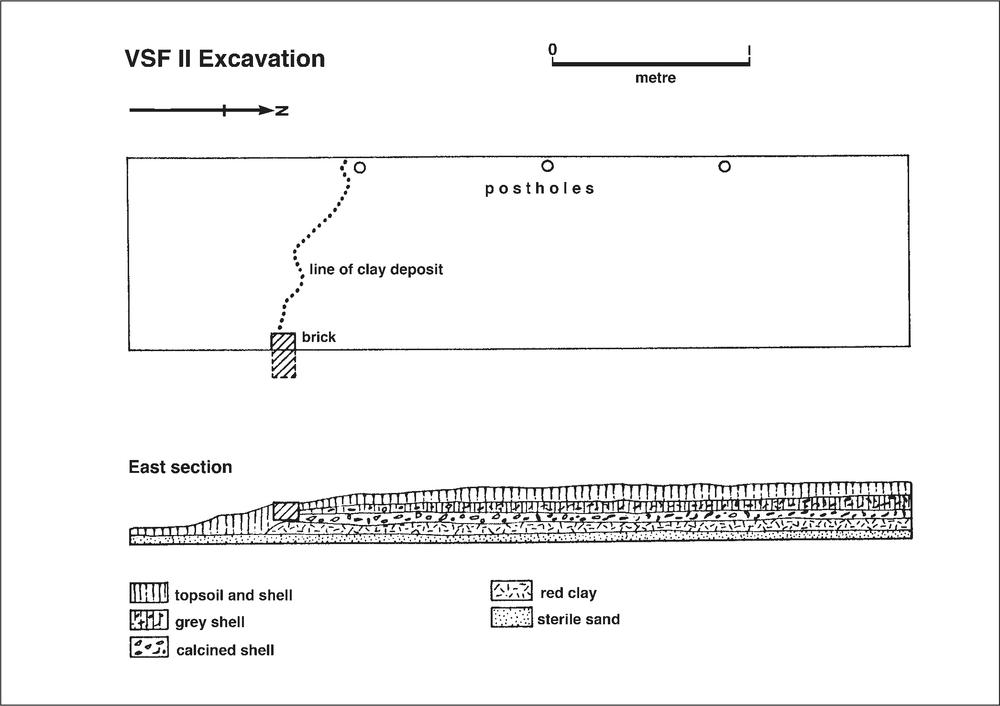

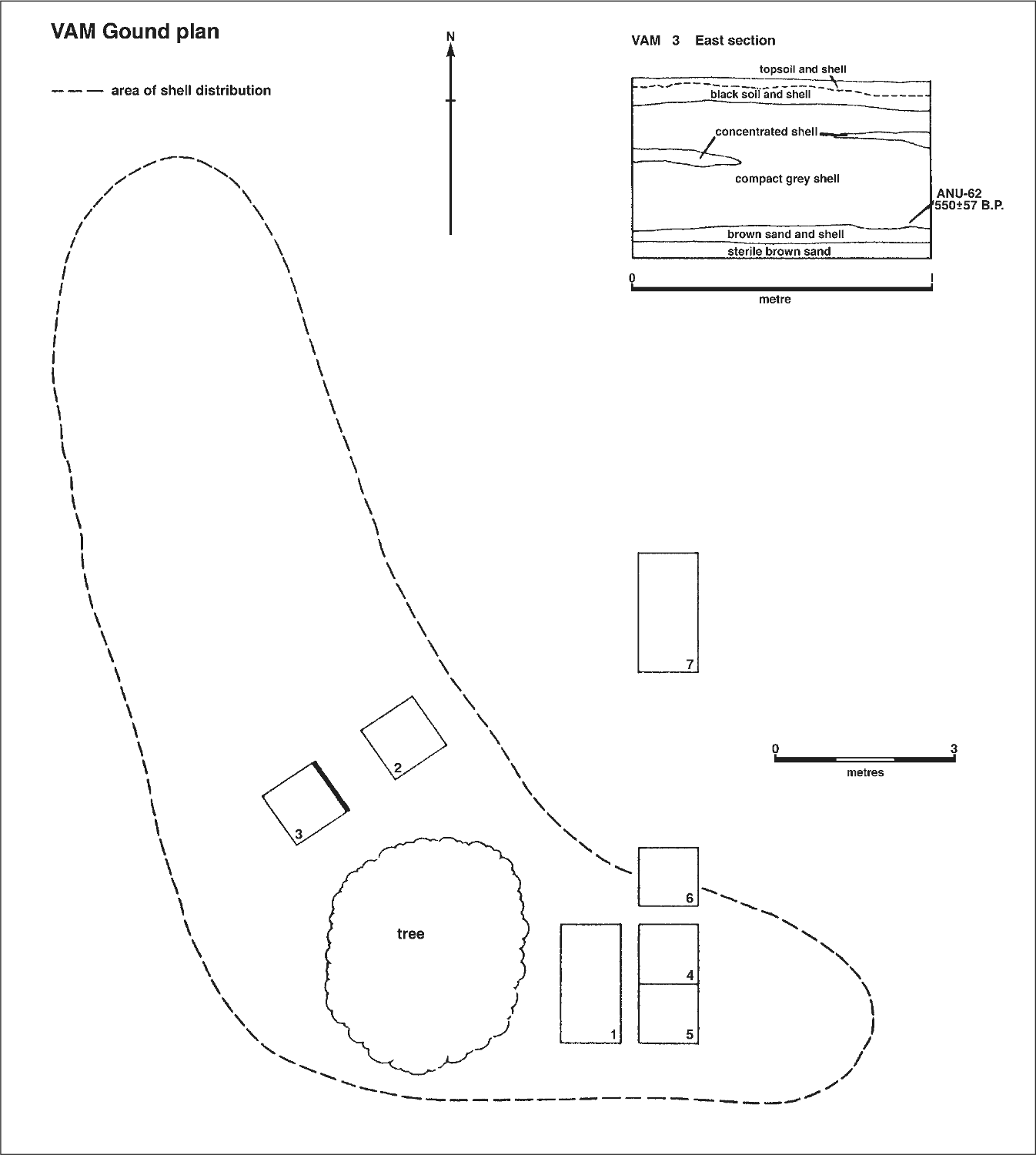

SHELL FLOOR No. 2 (Code prefix VSFII)

During the initial 1966 survey a trial trench was dug through a shell floor similar to the one just described. This was located at the northern end of the square approximately 6 m west of the quartermaster’s store (VQS). The shell mound covered an area of approximately 5 m by 7 m, oriented roughly east-west along the long axis.

Figure 29. VSF II stratigraphy. Two strata of shell flooring are visible, the lower one being heavily calcined.

VSFII excavation

The mound had suffered extensive damage from the re-growth of the vegetation in the area, but an area 4 m by 1 m was excavated across the mound (Figure 28). The results obtained were substantially the same as were to be obtained on the more extensive excavations of VSFI.

After passing through the topsoil layer two strata of shell flooring were encountered, the lower one being heavily calcined, and thus indicative of burning (Figure 29). This shell flooring rested on a stratum of red clay which overlaid the basal sand. Along the western edge, three post holes were uncovered which passed through the shelly and clay strata into the sand. These posts were not as substantial as those later excavated in the other shell floor, having a diameter of about 50 mm, but were in a straight line and probably indicate the western limit of the building. At the western end of the eastern edge a brick was uncovered in the section and this coincided with the southern extent of the red clay, which marks the southern edge of the building, although at this end it was eroded and irregular in outline.

VSFII finds

Finds occurred throughout the shell and clay deposits in plentiful fashion, consisting of pottery, glass and metal. In general, the stratigraphy and finds from this site can be equated with those from the other excavated shell floor. 34

Seven gm of bone fragments were recovered from the excavation, of which only the lower left molar of a large dog was recognisable.

Table 35. Glass from VSFII excavations according to type: number and weight in grams.

| TYPE A | TYPE B | TYPE C | Total | ||||

| No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. | No. | Wt. |

| 17 | 85.3 | 2 | 13.1 | 138 | 656.8 | 157 | 755.2 |

Table 36. Pottery counts from VSFII excavations according to type.

| Transfer Printed | 16 |

| Saltglaze Stoneware | 13 |

| Unglazed Wheelmade | 1 |

| Pipe Stems | 3 |

| Pipe Bowls | 1 |

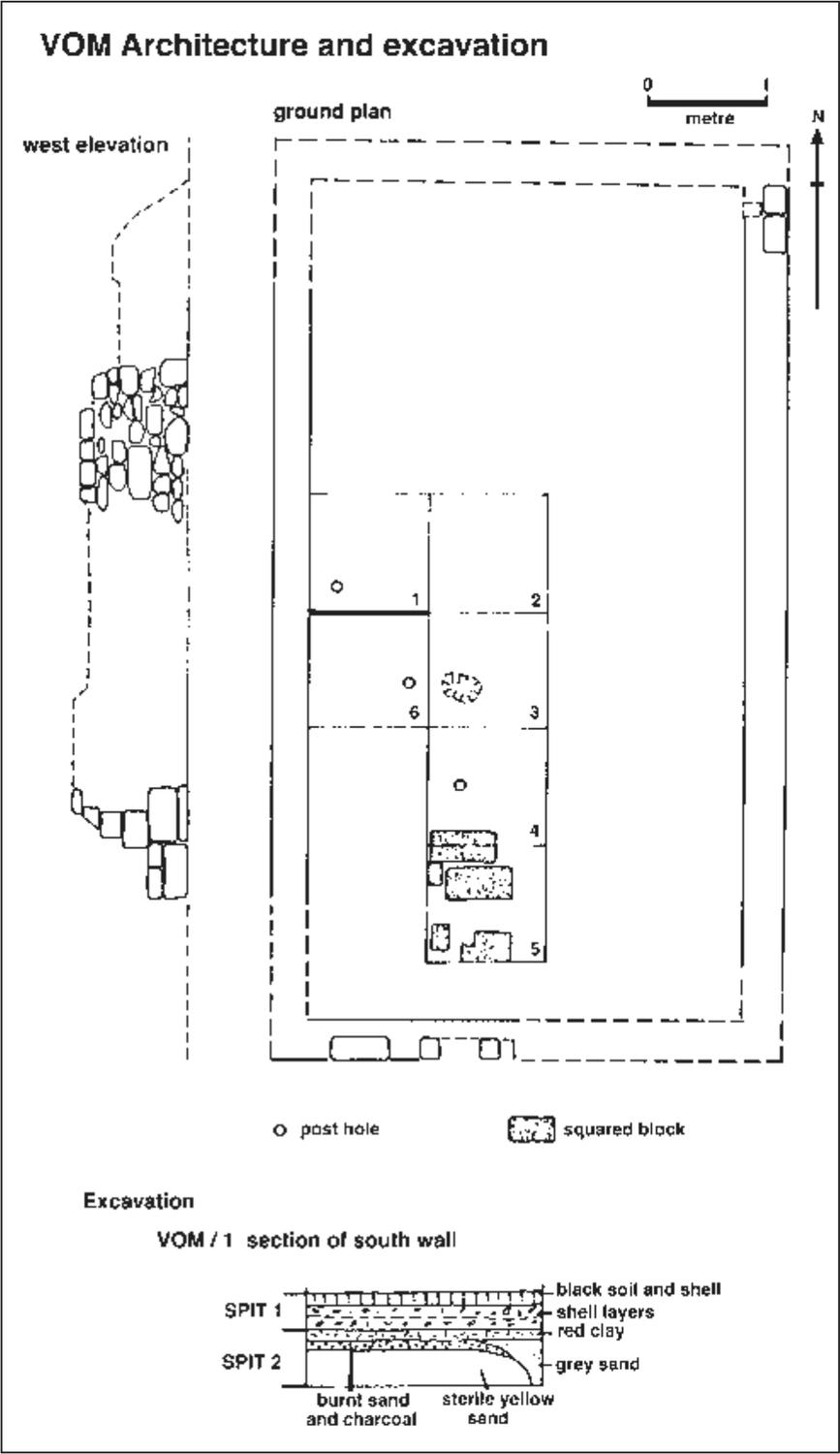

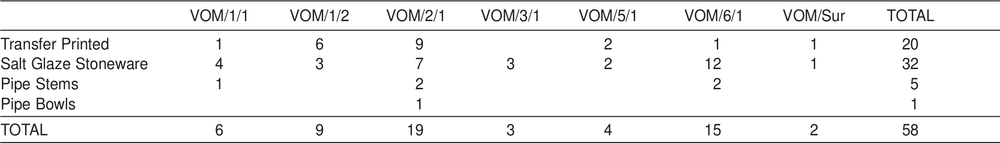

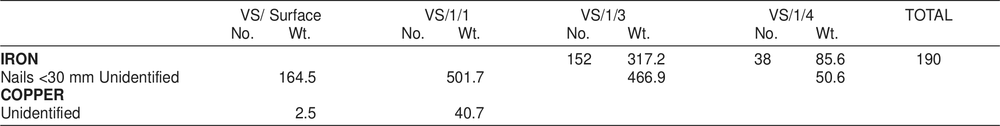

| Blue On White Porcelain | 1 |