Chapter 3

Pottery

In essence, pottery from the nineteenth century is no different to prehistoric pottery in regard to its archaeological potential. It is of little intrinsic value, fragile, subject to fashion and hence change, and because of its durable nature it remains in the archaeological record.

Working from these premises it is therefore possible to use pottery from historic sites in much the same way as pottery is used in prehistoric sites. Classifications can be evolved in order to use pottery as space/time markers, for inferring basic economics, inferring standards of technical development, and so on up the inferential scale. Some (for example Deetz 1965) have argued that social organisation may be reflected in pottery because it is a material reflection of culturally patterned behaviour, but whether this would be true in a small, closed society like the marine garrison at Port Essington is problematic.

In attempting to classify the Port Essington pottery the purposes of such a classification should be understood. While the analysis was not needed to date the site or identify the inhabitants, the short life of the site provided a good situation for testing the ability of the collection to do these things. A second test of this kind was to examine the distribution of pottery within the settlement to see what inferences might be made about the various house sites, whose nature was known from the historical record. The analysis was also designed to determine the origins of manufacture of the ceramics. The implications of these origins provide insight into the processes of daily life at Port Essington. For example, the large majority of wares were made in England. Thus for everyday utensils the settlement was dependent upon manufacture from the other side of the world, a nineteenth century reflection of an emerging global economy, even if the pottery was consigned via merchants from Sydney. This also has implications for the level of self-sufficiency of the marines at Port Essington (and also for the settlers at Sydney).

The pottery and other remains from Port Essington also serve as indicators of the rate and volume of diffusion of English manufactures into this area, and of the time lag of this diffusion.

The major difficulty in establishing an effective typology was the lack of comparative material with which to assess the present assemblage. While there are a number of works relating to the pottery industry in England at this period, for example Godden (1963, 1964) and the extensive reference lists he cites, almost all are written from the point of view of the antique collector, and scant attention is paid to the utilitarian pottery that comprises the present collection. The vast number of patterns and variety of styles has deterred any systematic study in this direction. As a result, authors freely admit the difficulty of identifying unstamped examples in more than a general way. During 1967, I visited potteries and specialist pottery museums in England to gather information relating to the Port Essington collection, but detailed work needs to be done over a number of years.

Archaeologists in America and Canada have worked on sites comparable in time to Port Essington but no reports I could obtain have attempted detailed analyses of the ceramics. One detailed unpublished report has been used (Pilling nd) and from other reports, types similar to the Port Essington collection have been identified from the illustrations and an attempt has been made to follow what terminology is already in use (Gjessing et al. 1962; Jury and Jury 1959; Pierson 1962; Poc 1963; Shenkell and Westbury 1965; Smith 1962, 1963). However, in many instances this has proved unsatisfactory and I have been left to invent my own procedures and terminology.

ARNOLD PILLING’S CLASSIFICATION

Pilling (nd) has set up a taxonomic system which divides his ceramics initially into two Classes, porcelain and earthenware, on the basis of translucence. Class is subdivided into Ware. Neither of these divisions is meant to imply any historical unity, this being claimed for the next subdivision, labelled Type. Where specific wares can be isolated within a type, such as ‘Willow Pattern’ within ‘Transfer Printed Type’, this he terms a Sub-Type. Afurther division into Item or Group allows Pilling to discuss specific pieces. Finally, he uses motif to mean a specific design unit, and pattern is a combination of specific units.

This is a useful taxonomy which I have modified and adopted. With the present assemblage however, there appears to be as much confusion as validity in attempting to differentiate the collection on the basis of hardness of fabric, which is the criterion Pilling uses at the Ware level of his classification. The majority of the Port Essington collection consists of what is commonly called ‘china’. The distinction between this and ‘stoneware’ is technically one of firing temperature and it is more practical to describe differences in fabric at the Type level.

Finally, Pilling analysed his collection (which consisted of 185 sherds compared to 1561 from Port Essington) in terms of:

• Fabric, which he confusingly refers to as biscuit. Here he describes colour, hardness, fracture, presence of bubbles, and homogeneity; and

• Glaze, again describing hardness, fracture, presence of bubbles, crackle, colour, and pattern colour. Some attention was also given to decoration pattern and vessel form.

THE PORT ESSINGTON POTTERY CLASSIFICATION

While Pilling’s analysis may point the way to significant factors in analysing nineteenth century ceramics in the future, the factors he has chosen do not present ways for making meaningful divisions for an archaeological taxonomy at present. The significance of crackle, for example, which may be deliberate or accidental, and can occur during or after firing, needs to be validated by examination of numbers of comparative collections, so that it is understood just what the significance of different types of crackle is. Similarly the Mohs scale of hardness test, which he employs, is at best inexact (Shepard 1963:115-6).

Given the present state of knowledge, decoration and vessel form suggest themselves as the best indicators of cultural and temporal change in nineteenth century ceramics. Pottery in this period was no longer a craft but rather a mass-produced manufacture, which resulted in a general conformity in shapes and standards of wares, as well as a great increase in individual designs, which nevertheless fall into general broad 58categories of decoration. This is particularly true of the transfer printed wares which make up almost half of this collection. The point is made at greater length in the discussion (below). Decoration colour appears to be a further valid indicator which has to be taken into account. It is on these factors that the present analysis is based.

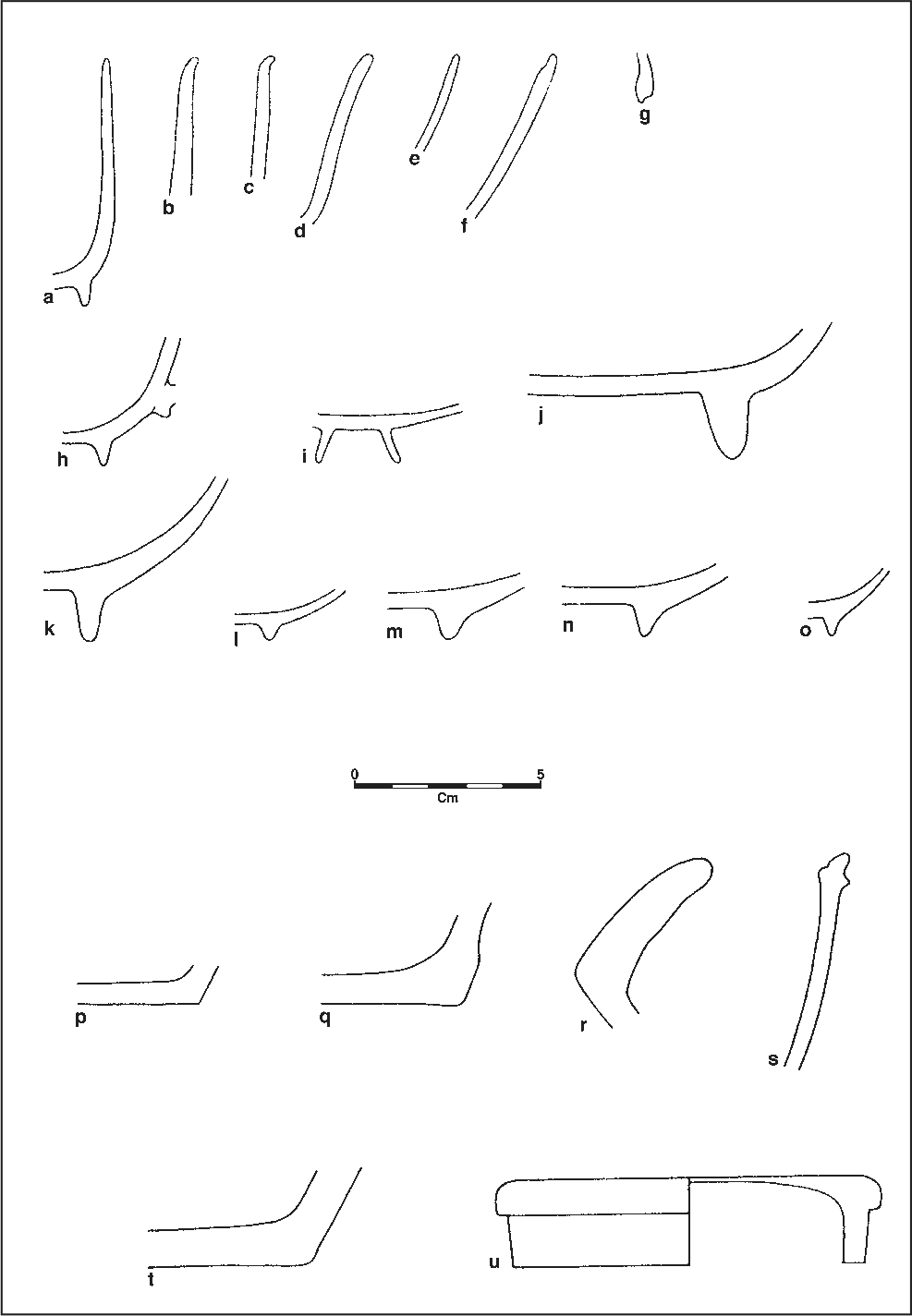

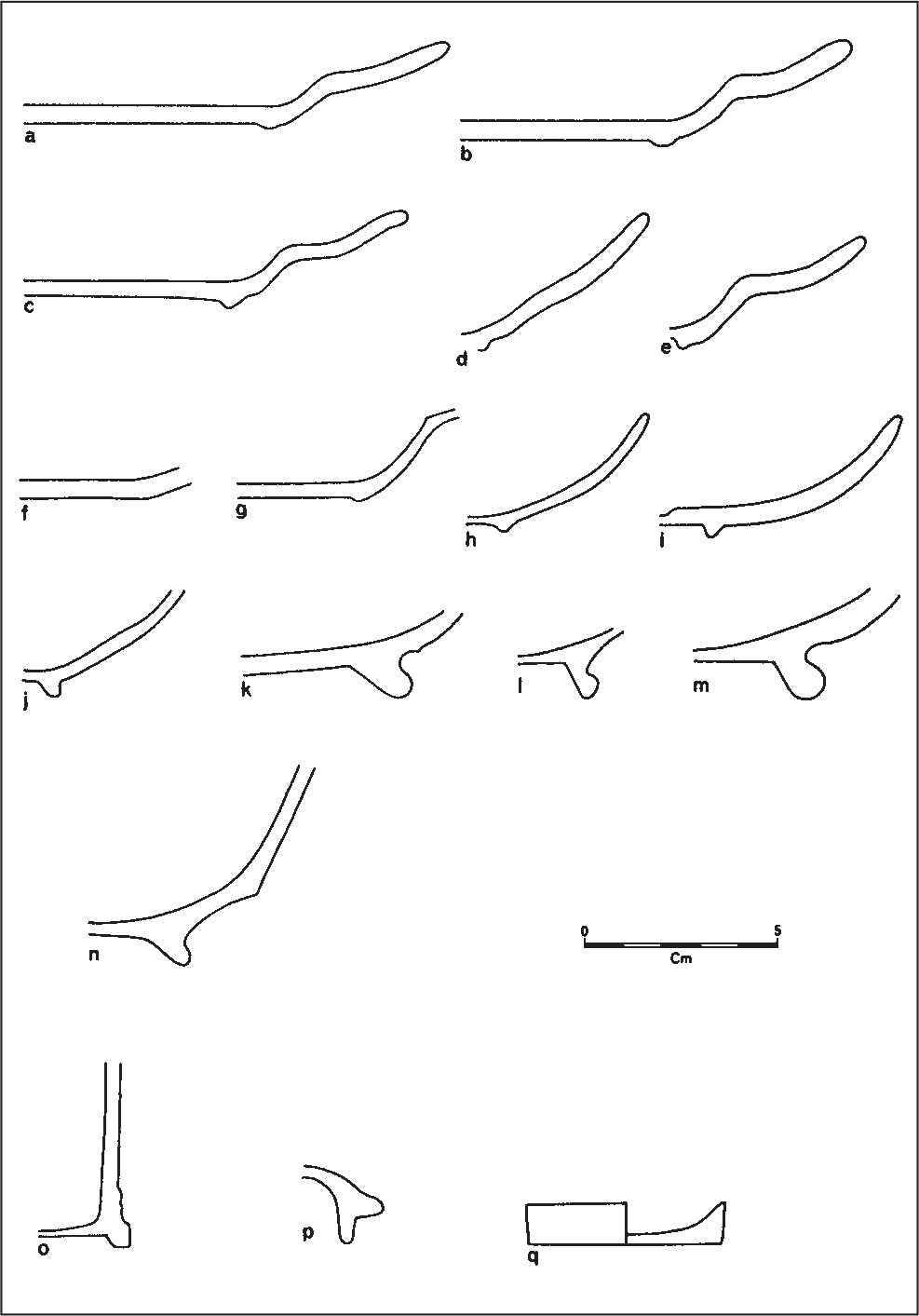

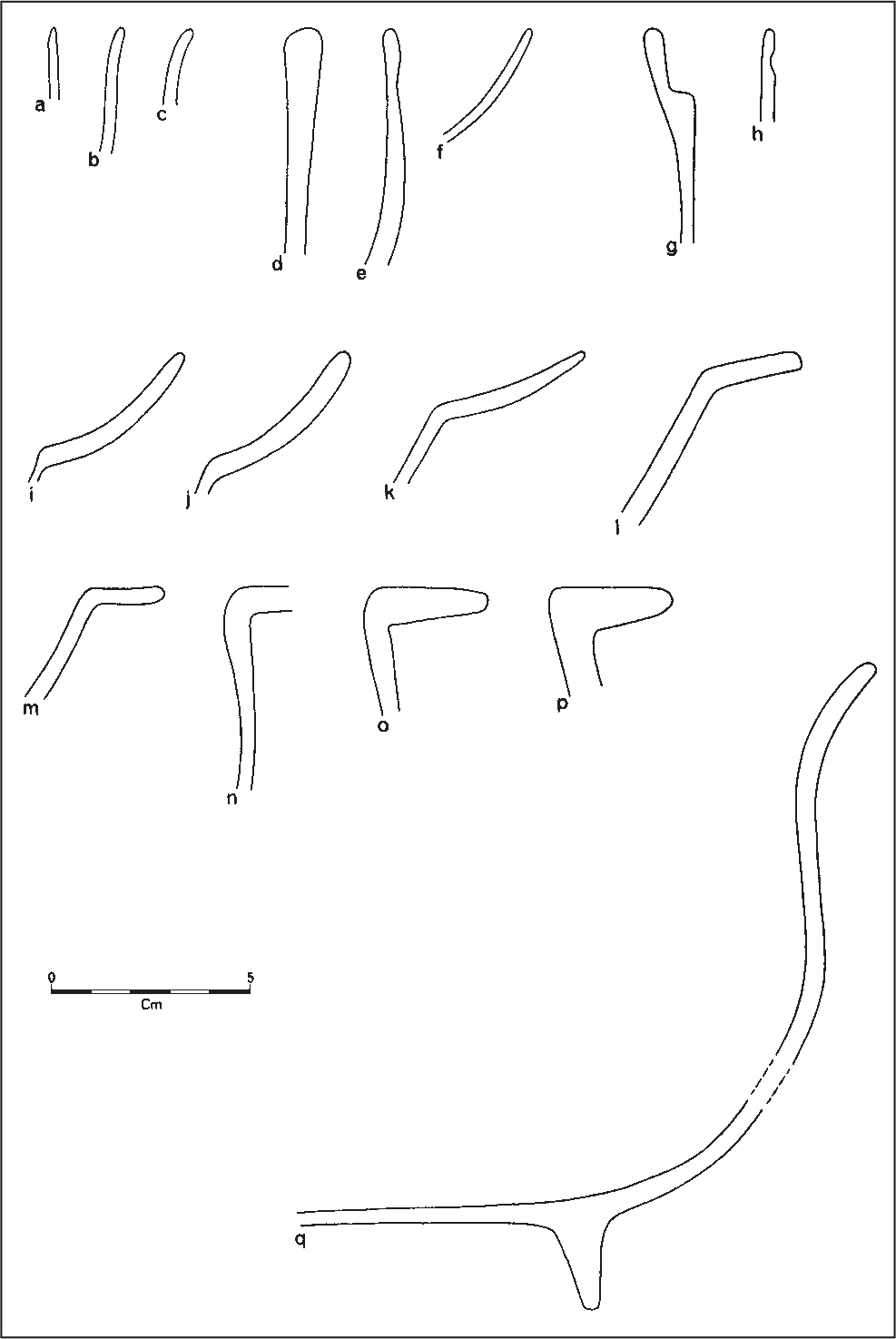

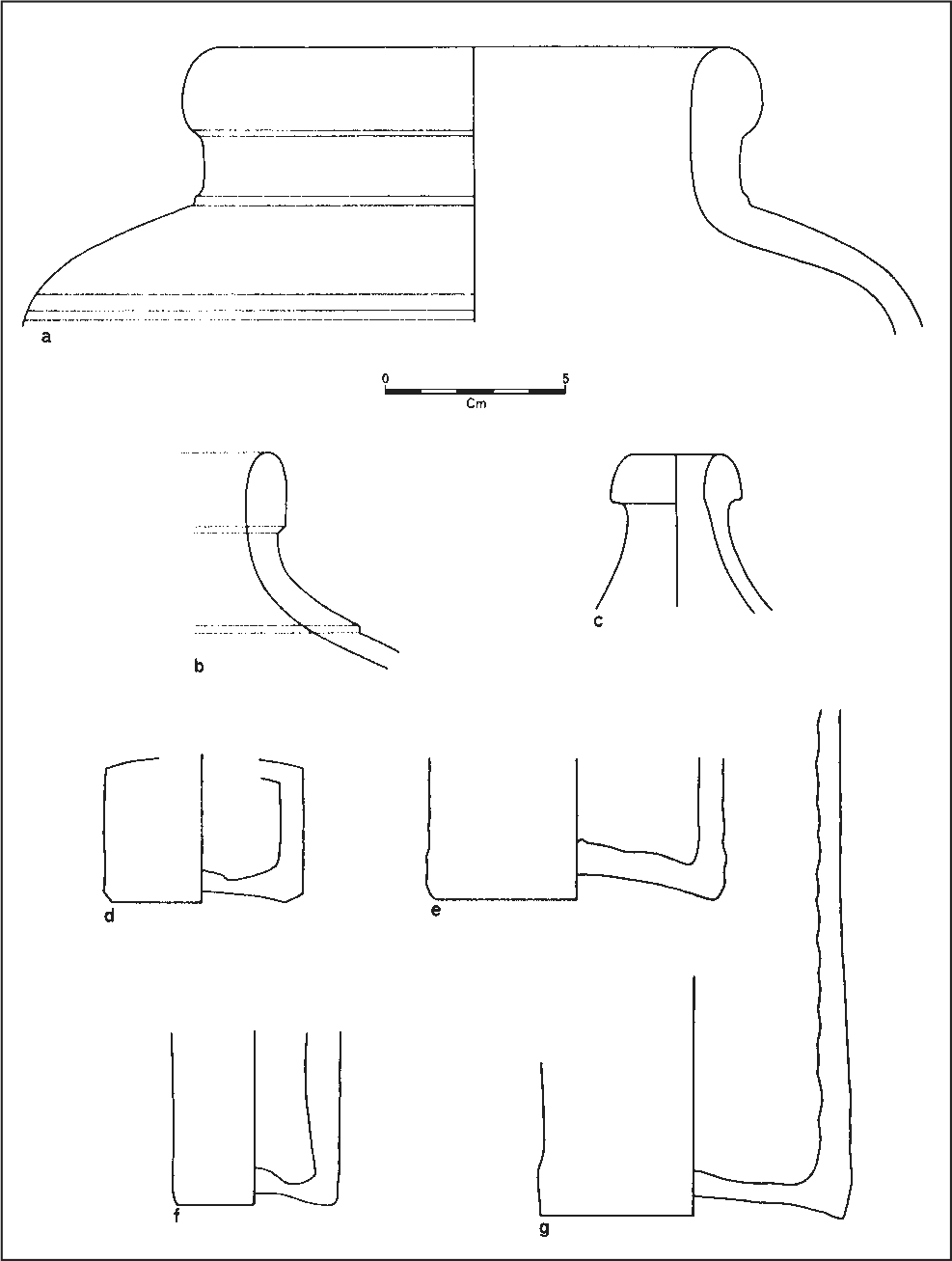

The pottery is divided into two Classes, porcelain and earthenware. The earthenwares are divided into two Groups, the white clay wares and the coloured clay wares. Both classes are divided Into Types, the first level at which any historical unity is implied. In the case of Transfer Printed Ware, this type is divided into Sub-Types. Within each type or sub-type specific Items are described. Ascending numbers are ascribed to each item to facilitate cross-reference with the plates and text. Each item is analysed according to form (the original total form of the object), thickness, base and rim diameter, decoration colour, and decoration. Rim and base diameters have been measured on a ‘Ceramicule’, a set of concentric circles designed by Colin Smart (Department of Anthropology ANU) to measure prehistoric pottery and the bracketed percentage for each type artefact described here indicates the amount of rim or base remaining. It was found that a fairly accurate diameter could be estimated on 10% of the rim or base; however in most cases this is reported to the nearest centimetre. To standardise the colours, the British Colour Council Dictionary of Colour Standards (British Colour Council 1934) is used in the abbreviated form, BCC, plus the appropriate number. Table 69 presents a key to the colours represented in the Port Essington collection.

This classification represents a first faltering step towards presenting a workable taxonomy for archaeologists in this field, which will need greater definition as work progresses in historical archaeology. It has obvious shortcomings. In a number of instances sherds from a single vessel will fall into different types, where, for example, different design elements are represented. Thus, comparisons of the numbers of different types are suspect. Only where all the motifs of a design can be recognised and placed within a single type can this difficulty be overcome. This would require much fuller documentation of designs than exists at present. What the classification does attempt is to present ranges of decorative motifs which were employed in pottery making in this period. It was decided as a conscious policy to present as large and detailed a description as possible, hoping that this would prove of most value to future workers. An attribute analysis was considered as the best alternative, as this would have overcome some of the limitations discussed above. It was discarded for three reasons

Table 69. Key to BCC colours present in the Port Essington collection.

• the motifs do not recur often enough to indicate quantitative trends at this close level;

• the number of attributes was too great to analyse without extensive use of a computer; and

• the final product would not have been as useful for future workers.

CLASS 1 – PORCELAIN

All porcelain represented in this collection is of the true hard paste variety. Difficulty was experienced in distinguishing between British and Asian porcelains in terms of fabric and glaze, and only the pieces decorated with the Willow Pattern can positively be identified as British. Of the others, the group represented by Items 4 and 5, below, are attributed to Asian manufacture in terms of shape rather than decoration, and the large remainder may safely be assumed to be Asian in origin.

TYPE A – UNDECORATED PORCELAIN – 39 sherds (Items 1–3)

Note: Although these items are listed here as a separate category they may only represent undecorated fragments of vessels which were originally decorated.

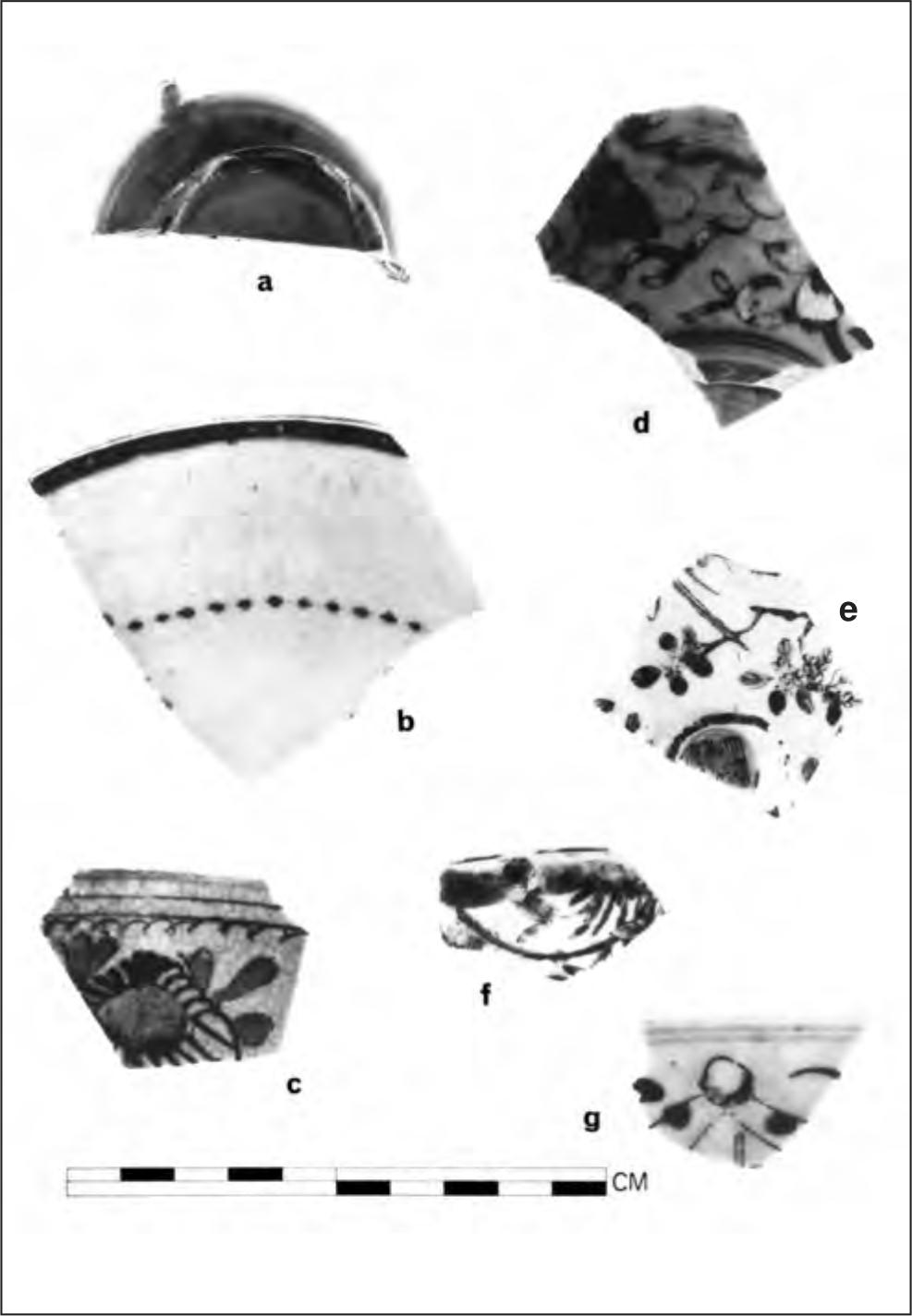

Distribution: VM, VCC, VMQ. Forms: footed bowls or cups. Of the six base sherds represented, the bottom of the foot is unglazed in each case. Thickness: 15 mm to 55 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: between BCC 1 and BCC 7.

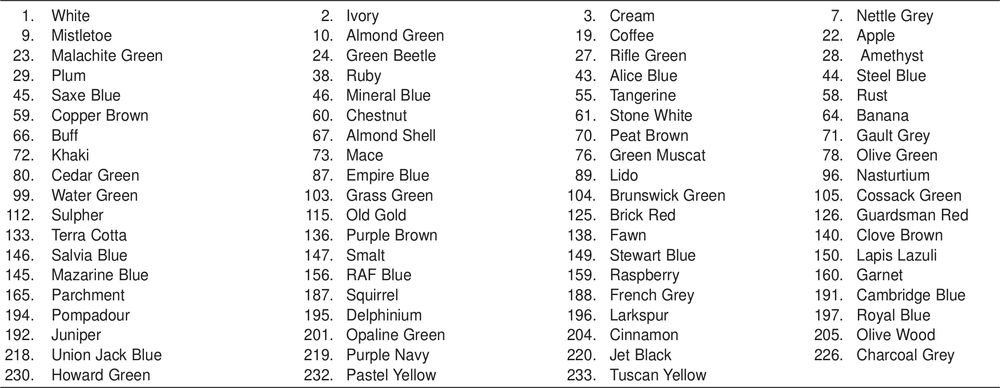

Item 1 VM/5/1 (5), Figure 59-a, 60-h.

Form: cup with handle. Thickness: 35 mm. Base diameter: 40 mm (50%).

Item 2 VM/9/1 (37), Figure 60-o.

Form: cup or bowl. Thickness: 3 mm to 55 mm. Base diameter: 60 mm (estimated).

Item 3 VM/5/1 (14), Figure 60-l

Form: bowl. Thickness: 3 mm. Base diameter: 140 mm (9%).

TYPE B – OVERGLAZE POLYCHROME PORCELAIN – 78 sherds (Items 4–11)

Distribution: VM; VMI1, VHK, VCC. Forms: cups, straightsided bowls, plates, lids. Thickness: 15 mm to 85 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1 to BCC 7. Glaze colour: BCC 1 to BCC 7. 59Decoration colour: a wide range of which the following are predominant; yellow (BCC 112), green (BCC 9, BCC 23, BCC 99), red (BCC 96, BCC 125, BCC 126, BCC 159), gilt (BCC 115), and blue (BCC 45, BCC 219). Decoration: all motifs above the glaze are hand painted. The most predominant motif is a floral one. In addition some underglaze blue decoration is present. This takes the form of a double blue line running horizontally around either the interior or exterior of the rim, or around the foot of the vessel. In one instance a similar line runs internally around the base of a bowl.

Item 4 VM/GEN SUR (1), Figure 59-b

Form: curved lid with unglazed edge. Thickness: 4.5 mm. Rim diameter: 220 mm (10%). Decoration colour: BCC 219, BCC 125, BCC 115. Decoration: the border is decorated with a band of dark blue overlain with gilt asterisks. An additional line of dark blue dots lies within the border, joined with gilt and red.

Remarks: This piece, together with Item 5, represents a group of 24 sherds with similar decoration. The decorative motif is unusual in this collection and within this type. However, in terms of shape it seems reasonable to ascribe this group to Asian manufacture.

Item 5 VM/9/1 (36), Figure 60-a

Form: cup. Rim diameter: 75 mm (15%). Base diameter: 60 mm (8%). Decoration: see Item 4.

Item 6 VCC/GEN SUR (88), Figures 59-c, 60-c.

Form: straight-sided bowl with everted rim. Thickness: 4 mm.

Rim diameter: approx. 160 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 23, BCC 159. Decoration: external only, a floral motif.

Remarks: In contrast to the other items within this type, the glaze is dark (BCC 7) and heavily crackled.

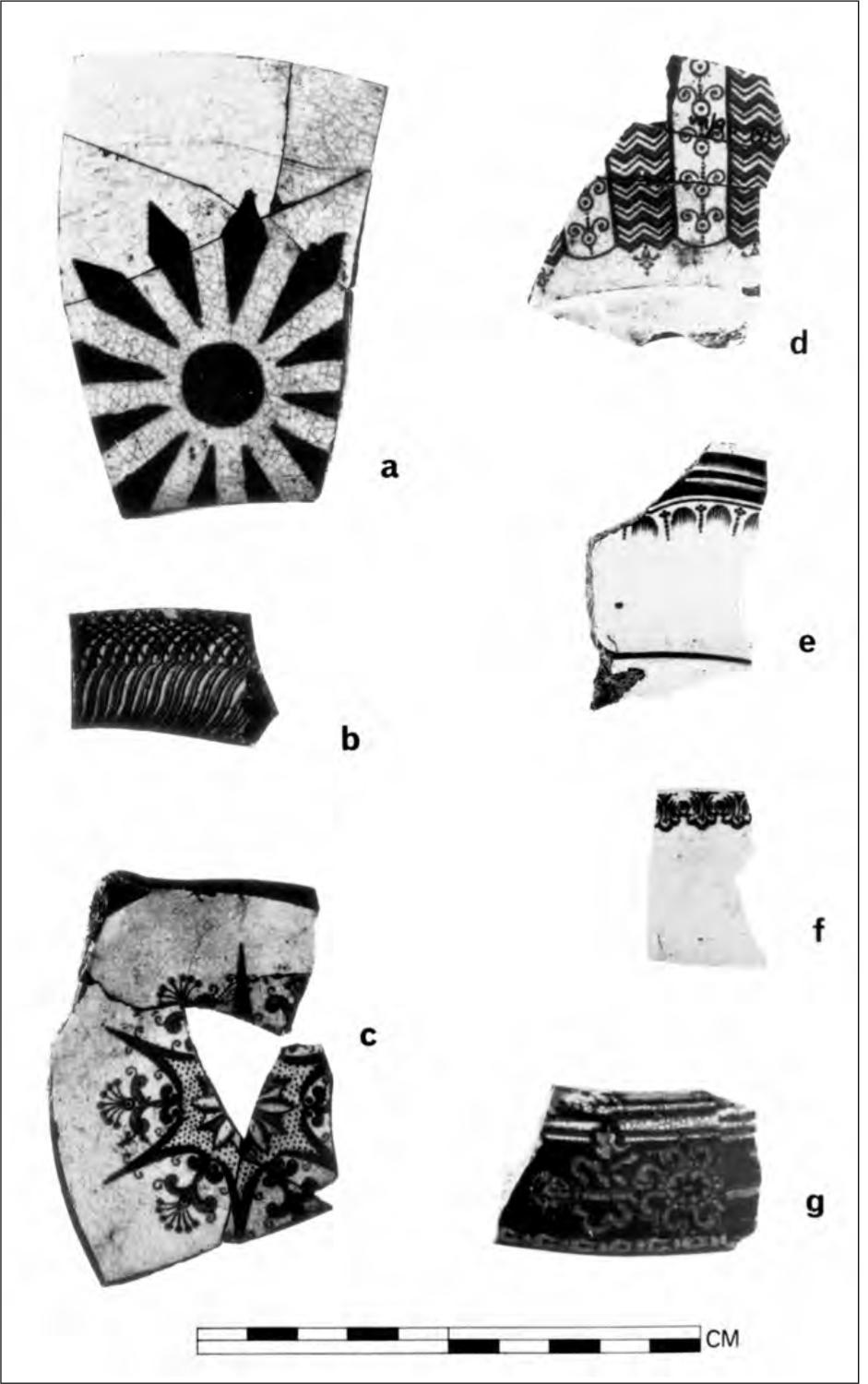

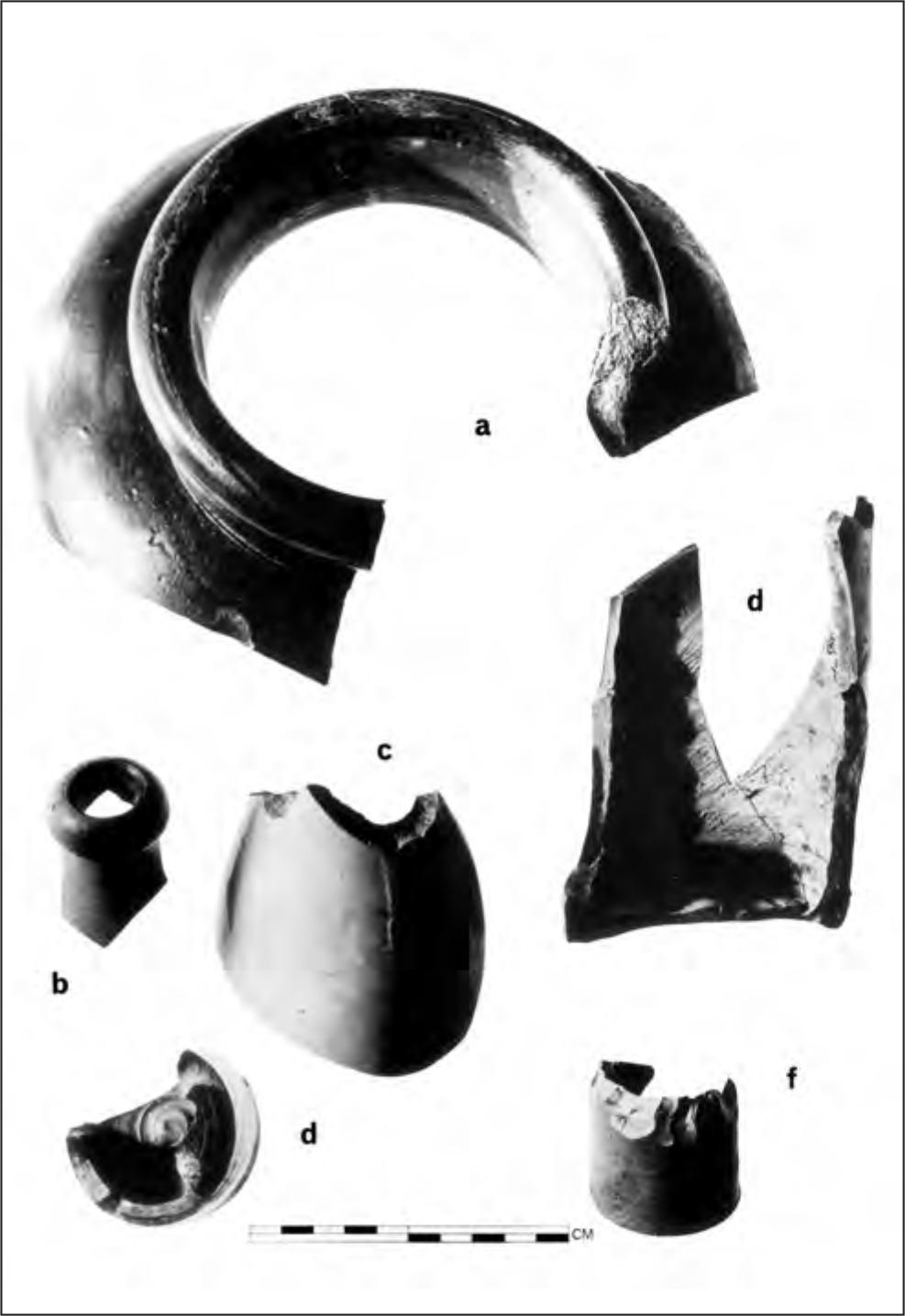

Figure 59. Port Essington pottery: Undecorated Porcelain (a); Overglaze Polychrome Porcelain (b-g).

Item 7 VMII/1/1 (5), Figures 59-d, 60-k.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 3 mm to 9 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 9, BCC 45, BCC 156. Decoration: internal and external underglaze decoration with the double line motif, together with external floral decoration.

Item 8 VM/9/1 (35), Figures 59-e, 60-I, 78-a.

Form: bowl with small pedestal foot. Thickness: 2.5 mm (body) to 4.5 mm (base). Base diameter: 25 mm (50%). Decoration colours: BCC 9, BCC 126, BCC 115. Decoration: external in blossom tree motif.

Remarks: painted on the underside of the base is a date mark of the Emperor Tao Kuang (1821–1850).

Item 9 VM/9/1 (39), Figure 60-f.

Form: bowl described in Item 8. Rim diameter: 100 mm (13%).

Remarks: Part of Item 8? Interior of lip unglazed suggesting that the bowl was lidded (see Item 10).

Item 10 VM/9/1 (45), Figures 59-f, 60-g.

Form: flanged lid. Thickness: 25 mm. Rim diameter: (at flange) 100 mm (11%). Decoration colours: BCC 9, BCC 126, BCC 115. Decoration: external floral motif.

Remarks: Despite the difference in decoration, this lid perhaps belongs to the vessel described in Items 8-9. Note that the rim diameters match.

Item 11 VMII/1/1 (11), Figures 59-g, 60-e.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 2 mm to 3 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 96, BCC 126. Decoration: underglaze, double line internally and externally at rim. Overglaze decoration externally in abstract motif.

Figure 60. Port Essington pottery: pottery profiles (1). 60

TYPE C – BLUE ON WHITE. PORCELAIN – 100 sherds (Items 12–21)

Distribution: VM, VMII, VCC, VQS, VSD, VH, VHK, VMQ, VSF. Forms: mainly footed bowls, some plates. Thickness: 2 mm to 10 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1 to BCC 7. Glaze colour: BCC 7 to BCC 71. Decoration colour: mainly blues (BCC 43, BCC 45, BCC 150) merging to green (BCC 78) and grey (nearest BCC 226). Decoration: consists of hand-painted underglaze designs of floral, geometric and figurative motifs. The double line motif used internally and externally at the rim is common and also occurs around the foot.

Remarks: the foot is always unglazed on the bottom; in one item the base is unglazed; in two items a section of the internal wall is unglazed. Glaze crackle occurs frequently but not predominantly.

Item 12 VCC/GEN SUR (117), Figure 61-a.

Form: plate or dish with unglazed base. Thickness: 6.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: solid geometric pattern unusual in this collection.

Item 13 VQS/4/1 (26), Figures 61-b, 60-m. Form: footed bowl with base and internal face of foot unglazed. Thickness: 5 mm (base) to 8 mm (lower body). Base diameter: approximately 220 mm (5%). Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: double line motif on foot; on the interior similar lines running around the circumference of the bowl, together with registers of parallel short lines running at right-angles to the circumference of the vessel.

Item 14 VCG/GEN SUR (125), Figures 61-c, 60-n.

Form: footed bowl. Thickness: 4.5 mm to 6.5 mm. Base diameter: 140 mm (13%). Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: externally around the foot with three parallel lines; internally in a free floral motif.

Item 15 VM/S/1 (11), Figure 61-d.

Form: plate. Thickness: 6 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 195. Decoration: a continuous fern motif around the border.

Remarks: the internal face below the border is unglazed.

Item 16 VCC/GEN SUR (63), Figure 61-e.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 145. Decoration: on one side (external?) only, a complex figurative pattern.

Item 17 VM/10/1 (26), Figures 61-f, 60-b.

Form: straight-sided bowl with slightly everted rim. Thick-ness: 3 mm to 5 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 197, BCC 78. Decoration: internal and external undefined figure pattern.

Item 18 VCC/GEN SUR (64) Figure 61-g.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 5 mm to 8 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 45 to BCC 230. Decoration: floral/figurative motif applied internally and externally.

Item 19 VCC/GEN SUR (36), Figures 61-h, 60-d.

Form: bowl with slightly sloping and everted rim. Thickness: 4 mm. Rim diameter: 160 mm (10%). Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: continuous leaf motif internally on lip, and externally.

Item 20 VCC/GEN SUR (211), Figure 61-i

Form: bowl. Thickness: 6 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 45. Decoration: external figurative motif.

Item 21 VMS/E (17) + VM1911 (46), Figures 61-j, 60-j.

Form: footed bowl. Thickness: 5 mm to 9 mm. Base diameter: 190 mm (13%). Decoration colours: BCC 43 to BCC 230. Decoration: indeterminate splotches and lines internally and externally. Internal base decorated with large spiral motif.

Remarks: unidentifiable mark on bottom of base.

TYPE D – TRANSFER PRINTED PORCELAIN – 3 sherds (Item 22)

Distribution: VCC. Form: plate. Thickness: 3.5 mm to 7 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 7. Glaze colour: BCC 7. Decoration colour: BCC 87. Decoration: underglaze transfer decoration of the less common ‘mosquito’ variation of the Willow Pattern.

Remarks: all three items comprising this type can be attributed to a single plate.

Item 22 VCC/GEN SUR (201) Figure 61-k, 67-e.

Form: plate with indented edge. Thickness: 7 mm. Rim diameter: 240 mm (11%). Base diameter: Approx. 130 mm (5%).

Figure 61. Port Essington pottery: Blue on White Porcelain (a-j); Transfer Printed Porcelain (k). 61

CLASS 2 – EARTHENWARE

GROUP 1 – THE WHITE CLAYWARES

All wares in this group are of the hard paste variety. Since hardness tests appear a dubious way to distinguish between the utilitarian wares of this period, no scale of differentiation on this basis can be applied to distinguish and isolate what are called ‘stone china’ wares from slightly softer white clay wares. Although some technical differences may occur, it is more useful to regard all the white clay wares of this period as hard paste.

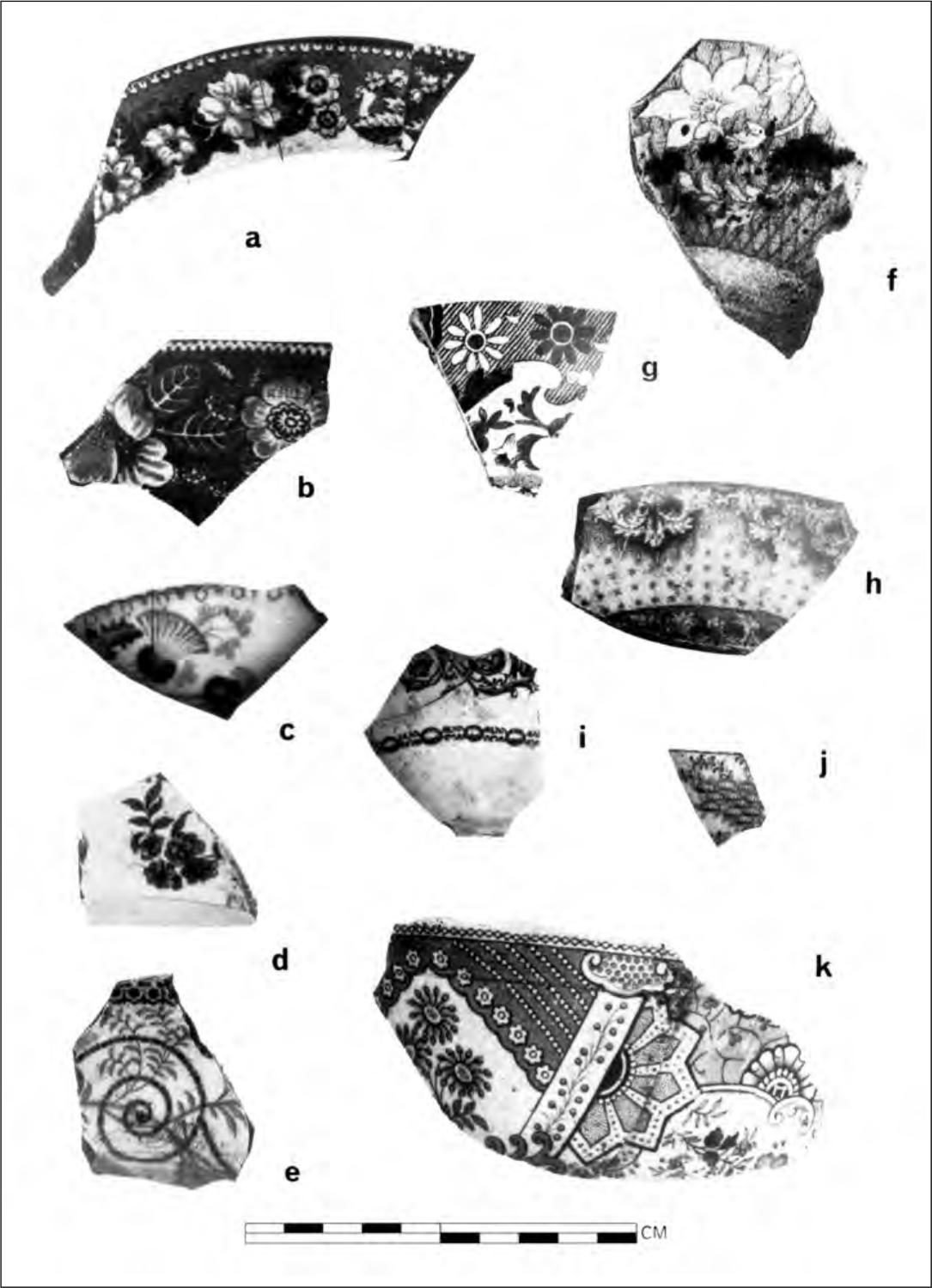

TYPE A – TRANSFER PRINTED WARE

Of the total collection, 46.7% falls into this type and meaningful sub-types can be established. The divisions are made initially in terms of decoration colour, and secondly on the basis of decoration subject matter.

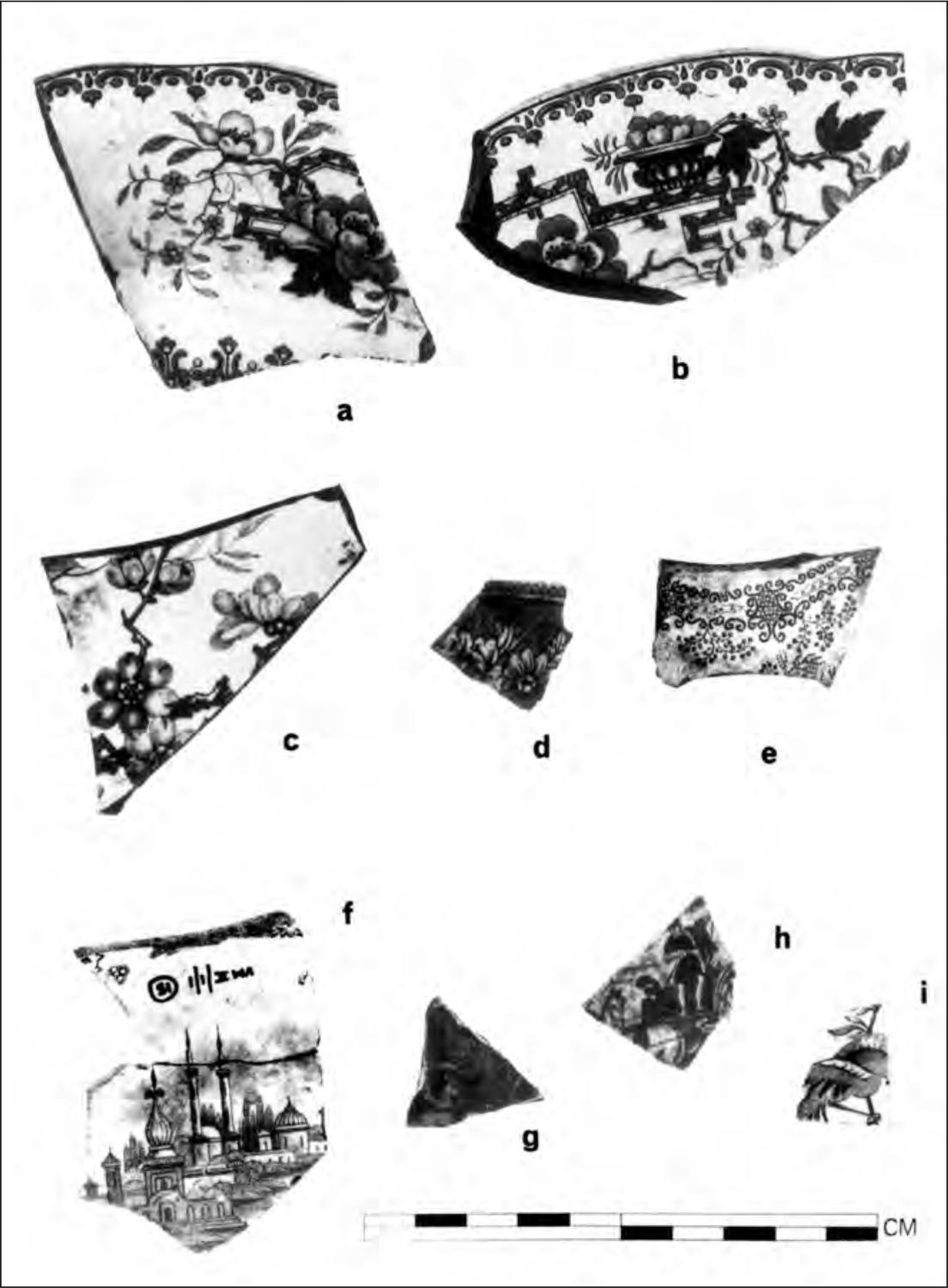

SUB-TYPE AA – GREEN FLORAL TRANSFER WAR – 23 sherds (Items 23-27)

Distribution: VM, VMII VCC, VQS. Thickness: 3 mm to 6 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1, BCC 2. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colours: BCC 10, BCC 80, BCC 191, BCC 192. Decoration: 11 sherds are decorated with a similar pattern (see Item 23). The floral patterns are predominantly executed against an open background in this sub-type. Item 26 is the exception.

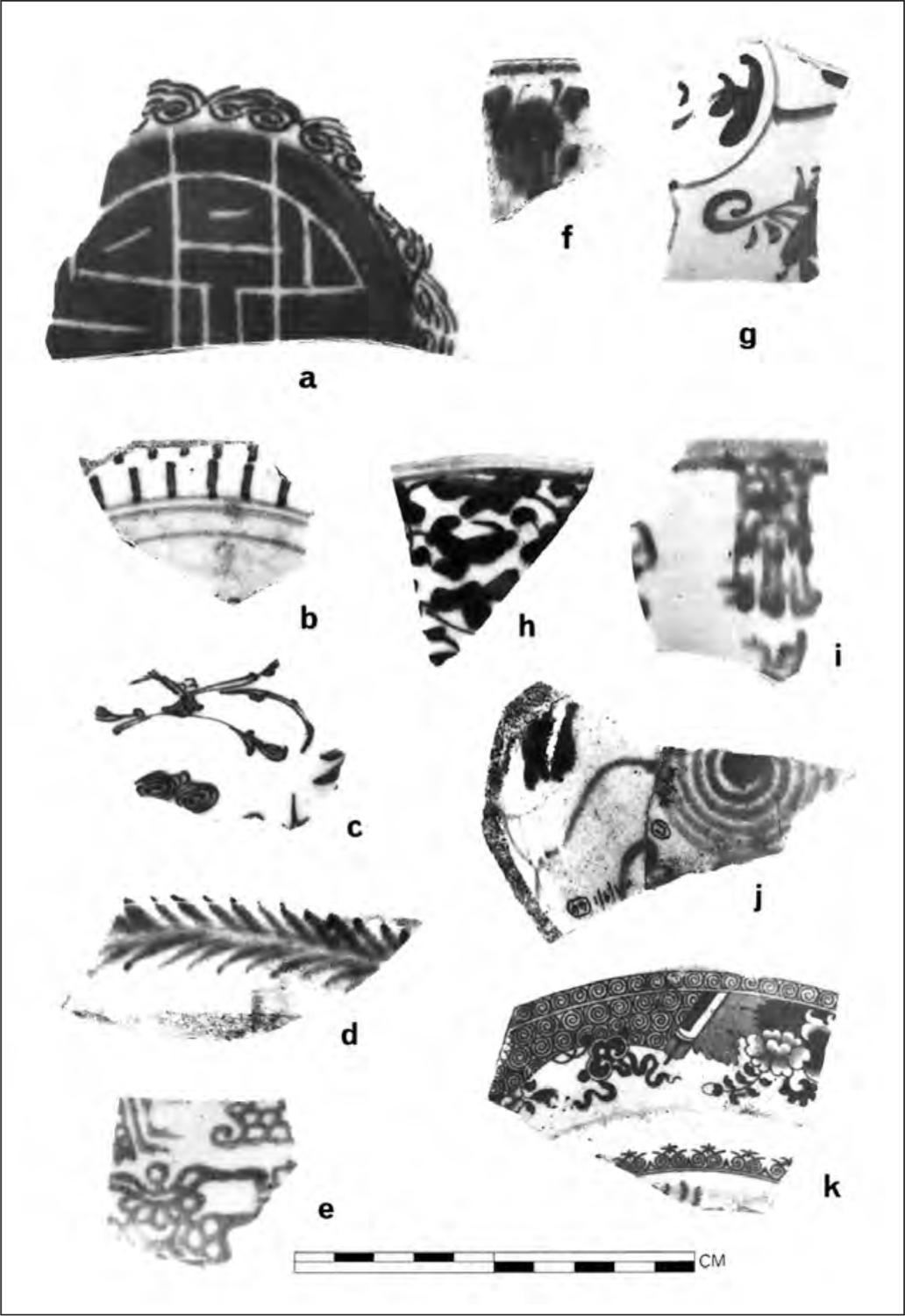

Item 23 VM/14/1 (3), Figures 62-a, 68-k.

Form: deep plate or bowl. Thickness: 5 mm. Rim diameter: 140 mm (13%). Decoration colour: BCC 80. Decoration: register of floral motifs contained in minor geometric motifs.

Item 24 VM/S/L (1), Figure 62-b.

Form: vessel described in Item 23. Item 25 VM/GEN SUR (8), Figures 62-c, 78-b.

Form: plate. Thickness: 5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 80. Decoration: see Item 23.

Remarks: this sherd probably belongs to the vessel described in Items 23-24. Mark on the base is a flower decorated plaque inscribed ‘—OWERET’ (probably ‘FLOWERET’). Below is the letter ‘M’. This single letter was used extensively by the Minton pottery, and its use is equated in time to the period c. 1822-36 (Godden 1964:439).

Item 26 VMII/1/1 (35), Figure 62-d.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 191, BCC 192. Decoration: floral motif set against a ‘closed’ (stippled) background.

Item 27 VCC/GEN SUR (28), Figure 62-e.

Form: plate. Thickness: 3.5 mm. Base diameter: approx. 100 mm (9%). Decoration colour: BCC 10. Decoration: combined floral and geometric motifs executed in a fine stipple.

SUB-TYPE AB – GREEN SCENIC TRANSFER WARE – 14 sherds (Items 28-31)

Distribution: VMII, VSD, VH. Thickness: 3 mm to 7.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colours: BCC 22, BCC 104, BCC 191, BCC 192. Decoration: various exotic scenes. The main motifs are architectural, human and animal representations.

Item 28 VMII/1/1 (8) + (15), Figure 62-f.

Form: deep plate. Thickness: 4 mm. Base diameter: 100 mm (19%). Decoration colour: BCC 191. Decoration: Eastern townscape with minarets and towers.

Remarks: this scene is a common one in this collection, being also found on the blue printed wares. Miss Sue Davis (London Museum, pers. comm. January 1967) identified it as part of the ‘Bosphorus’ pattern, which enjoyed popularity during the relevant period, being made by several Staffordshire potteries, such as Samuel Alcock of Burslem and Davenport of Longport.

Item 29 VH/S/0 (1), Figure 62-g.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 7.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 192. Decoration: head and shield of a man in armour.

Item 30 VMII/1/1 (17), Figures 62-h, 78-c.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 3 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 191. Decoration: carriage drawn by two horses and driven by a bare-footed boy wearing a smock and cloak.

Figure 62. Port Essington pottery: Green Floral Transfer Printed Ware (a-e); Green Scenic Transfer Printed Ware (f-i).

62Remarks: impressed asterisk on base. Identified by Miss S. Davis (London Museum) as part of a pattern called ‘Venice’, used by Copeland and Garrett 1833-1847.

Item 31 VMII/1/1 (41), Figures 62-i.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 3 mm. Decoration colour: Between BCC 22 and BCC 104. Decoration: a cock standing on a branch. Background ‘open’.

Remarks: a copy of this motif in a similar colour was noted on sherd VSD/6/1 (3). This latter example comes from a different vessel.

SUB-TYPE AC – GREEN GEOMETRIC TRANSFER WARE – 10 sherds

Distribution: VM, VMII, VCC, VOM. Thickness: 2 mm to 4 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colour: BCC 104, BCC 191. Decoration: the decoration on these items is generally sparse; the most common motifs being horizontal lines, vertical chevrons and dotted connecting arcs.

SUB-TYPE AD – GREEN AND RED FLORAL TRANSFER WARE – 1 sherd (Item 31)

Item 31a VMII/1/1 (60).

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 3.5 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 160, BCC 201. Decoration: internal, a small leaf pattern in green; external, a floral motif in red, bounded by a scroll motif.

SUB-TYPE AE – RED FLORAL TRANSFER WARE – 20 sherds (Items 32–36)

Distribution: VM, VCC, VSF. Thickness: 2 mm to 7 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colours: BCC 1, BCC 61. Decoration colours: BCC 28, BCC 29, BCC 58. Decoration: 11 sherds in this sub-type have an identical distinctive floral motif against an open background. The other floral examples employ both open and closed backgrounds.

Item 32 VM/10/1 (8), Figures 63-a, 68-f.

Form: thin-walled bowl. Thickness: 3 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 29. Decoration: bunched ferns and flowers.

Item 33 VM/S/0 (4), Figure 68-c.

Form: bowl with everted rim. Thickness: 3.5 mm. Rim diameter: approx. 180 mm (7%). For decoration colour and decoration: see Item 32.

Item 34 VM/GEN SUR (23), Figure 63-b.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 3.5 mm. Rim diameter: very approx. 140 mm (4%). Decoration colour: BCC 28, BCC 58. Decoration: floral motif against open background with scroll motif along border. The petals of one flower have been hand coloured beneath the glaze.

Remarks: this is the only example of hand colouring a transfer in this collection.

Item 35 VM/S/L (15), Figure 68-a.

Form: cup. Thickness: 2 mm to 2.5 mm. Decoration colour and decoration: identical to Item 34, but decorated internally and externally.

Item 36 VCC/GEN SUR (162), Figure 63-c.

Form: plate. Thickness: 5.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 28. Decoration: leaf motif against a closed (stippled) background.

SUB-TYPE AF – RED SCENIC TRANSFER WARE – 6 sherds (Item 37)

Note: the six sherds in this sub-type belong to a single vessel.

Item 37 VOM/5/1 and VOM/2/1 (8, 9, 10, 11, 12), Figure 63-d.

Form: wavy-rimmed bowl. Thickness: 5 mm (rim) to 7 mm (body). Rim diameter: 220 mm (15%). Decoration colour: Between BCC 28 and BCC 29. Decoration: external geometric motifs; internal border of combined floral and geometric motifs with an architectural motif of a towered building surrounded by trees.

SUB-TYPE AG – BROWN FLORAL TRANSFER WARE – 6 sherds (Item 38)

Distribution: VM, VMII, VOC, VMQ. Thick-ness: 2.5 mm to 4.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1, BCC 2. Decoration colour: BCC 19. Decoration: various floral motifs; all examples employ a closed background.

Item 38 VM/GEN SUR (14, 15, 53) Figures 63-e, 67-h

Form: shallow bowl (total height 30 mm). Thickness: 3 mm. Rim diameter: approximately 160 mm (7%). Base diameter: 80 mm (17%). Decoration colour: BCC 19. Decoration: internal flower and vine motif on semi-closed background.

Figure 63. Port Essington pottery: Red Floral Transfer Printed Ware (a-c); Red Scenic Transfer Printed Ware (d); Brown Floral Transfer Printed Ware (e). 63

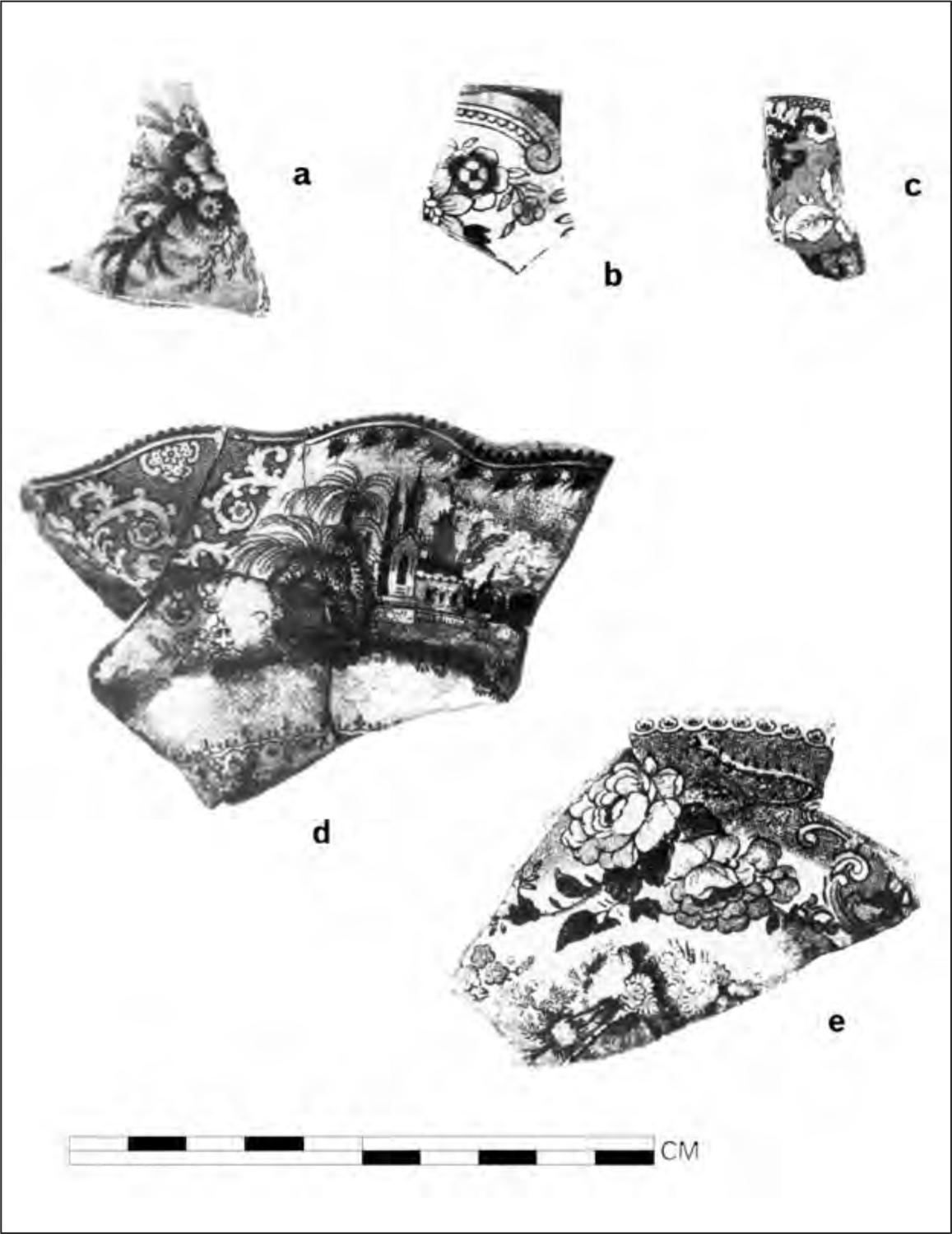

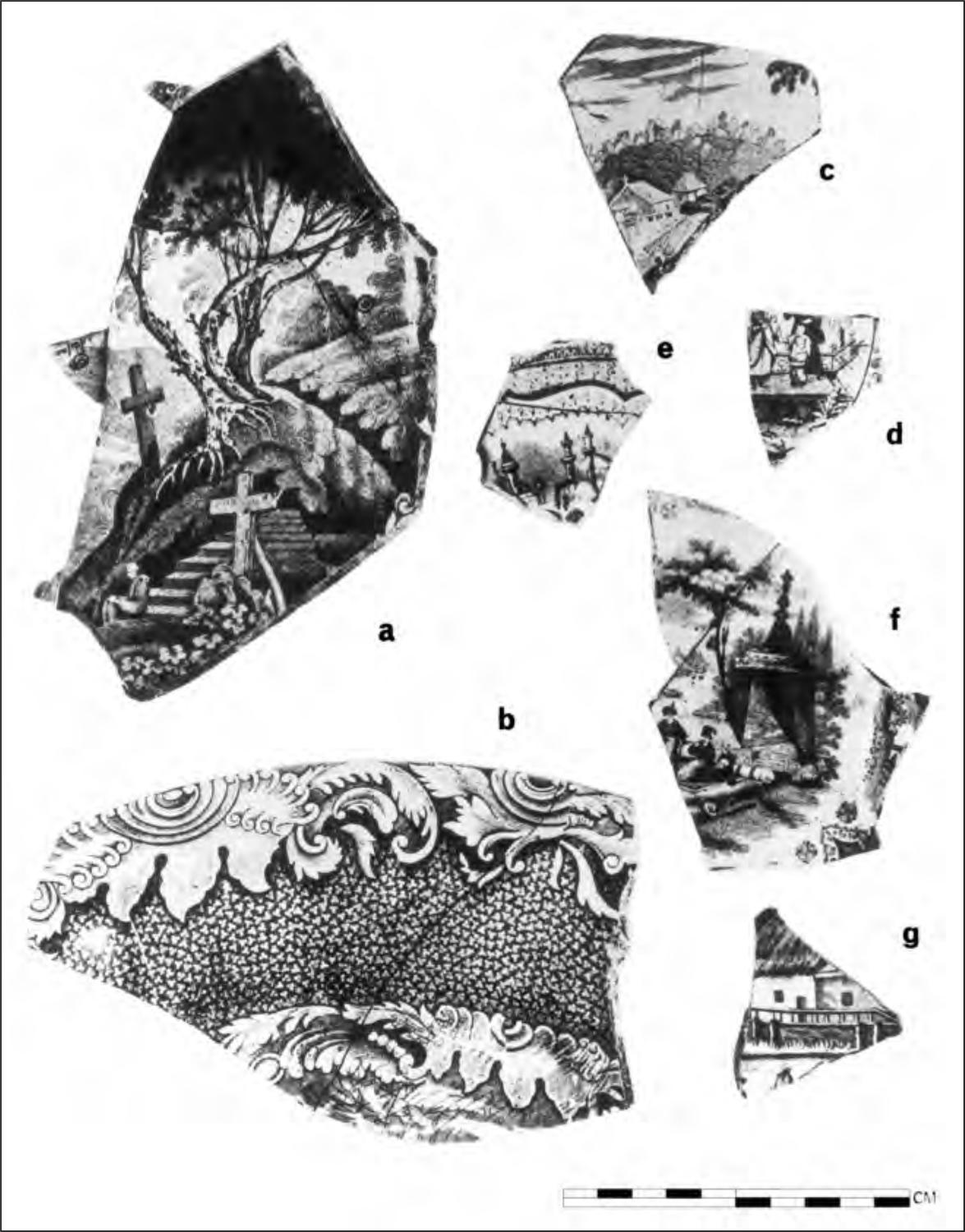

SUB-TYPE AH – BLUE SCENIC TRANSFER WARE – 104 sherds (Items 39–45)

Note: although items decorated with the Willow Pattern belong to this sub-type, they are treated in a separate category below. Distribution: VM, VMII, VCC, VMQ. Thickness: 2.5 mm to.10 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colours: BCC 89, BCC 145, BCC 146, BCC 149, BCC 150, BCC 194, BCC 197, BCC 218. Decoration: the scenes employed in this sub-type are most commonly architectural, pastoral and aquatic. The ‘Bosphorus’ pattern observed in green (above, Item 28) occurs on 15 sherds in this sub-type, which represents at least three and possibly five vessels. In addition 47 sherds have been isolated as belonging to a single large bowl or ewer (Item 39). Most patterns are bordered with either geometric or floral motifs, or a combination of both.

Item 39 VM/GEN SUR (8, 99) and VM/9/1 (6) and VM/10/1 (55) and VM/14/1 (1, 14, 29), Figures 64-a, b, 68-q, 78-d.

Form: large bowl or ewer. Thickness: 5 mm. Rim diameter 320 mm (17%). Base diameter: 150 mm (45%). Decoration colour: BCC 197. Decoration: external stylised leaf motif, which is also used internally around upper walls. The internal base carries a monastery scene, with a monk sitting on steps leading up a hill. Crosses stand on either side of the steps. On other sherds of this piece (not illustrated, but see Item 40) can be seen a distant convent or monastery.

Remarks: on the base is a printed stamp of the firm Copeland and Garrett, similar to Godden’s example no. 1092 (1964:173). The pattern design is ‘CONVENT’. The pattern appears to be a common one; it was also used by William Wridgway, Son and Co. of Hanley between 1838 and 1848 (Miss S. Davis, London Museum).

Item 40 VM/9/1 (43), Figures 64-c, 78-e.

Form: plate. Thickness: 3 mm to 4.5 mm. Decoration colour BCC 145. Decoration: the same pattern as Item 39. This sherd shows the distant convent (see Item 39).

Remarks: this sherd bears an impressed stamp of the Copeland and Garrett firm, with the number ‘18’ below it. Elsewhere on the base there are an impressed ‘6’ and a printed ‘D’.

Item 41 VMQ/8/1, Figure 64-d.

Form: plate or dish. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 150. Decoration: Oriental family group.

Remarks: apart from the Willow Pattern, this is the only sherd in the collection which illustrates directly the earlier Oriental influence on British blue decorated earthenwares.

Item 42 VM/S/W (1 and 9), Figures 64-e, 68-j.

Form: deep plate or dish. Thickness: 4.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 218. Decoration: part of the ‘Bosphorus’ pattern discussed above, showing the domes and towers and part of the mounted horseman. The scene is surrounded by a geometric motif.

Remarks: this pattern is repeated on a number of sherds in this sub-type.

Item 43 VM/9/1 (2) and VM/13/1 (9), Figures 64-f, 78-f.

Form: plate. Thickness: 4 mm. Base diameter: 110 mm (20%). Decoration colour: Between BCC 146 and BCC 218. Decoration: the scene is representative of the exotic nature of many of the scenes used; it shows three figures reclining in front of an elaborate canopy. A river, boats, mountains and trees form the background.

Remarks: this item has the printed pattern name ‘PALESTINE’ on the reverse. Of interest, on the extreme right of the present example, is the geometric motif and the feet of a horse and man, both of which are recurring motifs of the ‘Bosphorus’ pattern. Thus it appears that some of the examples of this latter pattern in the present collection probably represent border motifs on other patterns.

Item 44 VM/S/K (3), Figures 64-g, 67-f.

Form: plate. Thickness: 5 mm. Decoration colour: between BCC 89 and BCC 194. Decoration: river scene.

Remarks: this sherd is the only plate base of this ware which does not have a ring-foot. It is also unusual in decoration, which is less exotic and more realistic, and presented in more intense colours.

Item 45 VCC/GEN SUR (61), Figure 67-o.

Form: straight-sided mug. Thickness: 2 mm (base) to 4.5 mm (wall). Base diameter: 80 mm (40%). Decoration colour: BCC 145. Decoration: external, pastoral scene.

Figure 64. Port Essington pottery: Blue Scenic Transfer Printed Ware (a-g). 64

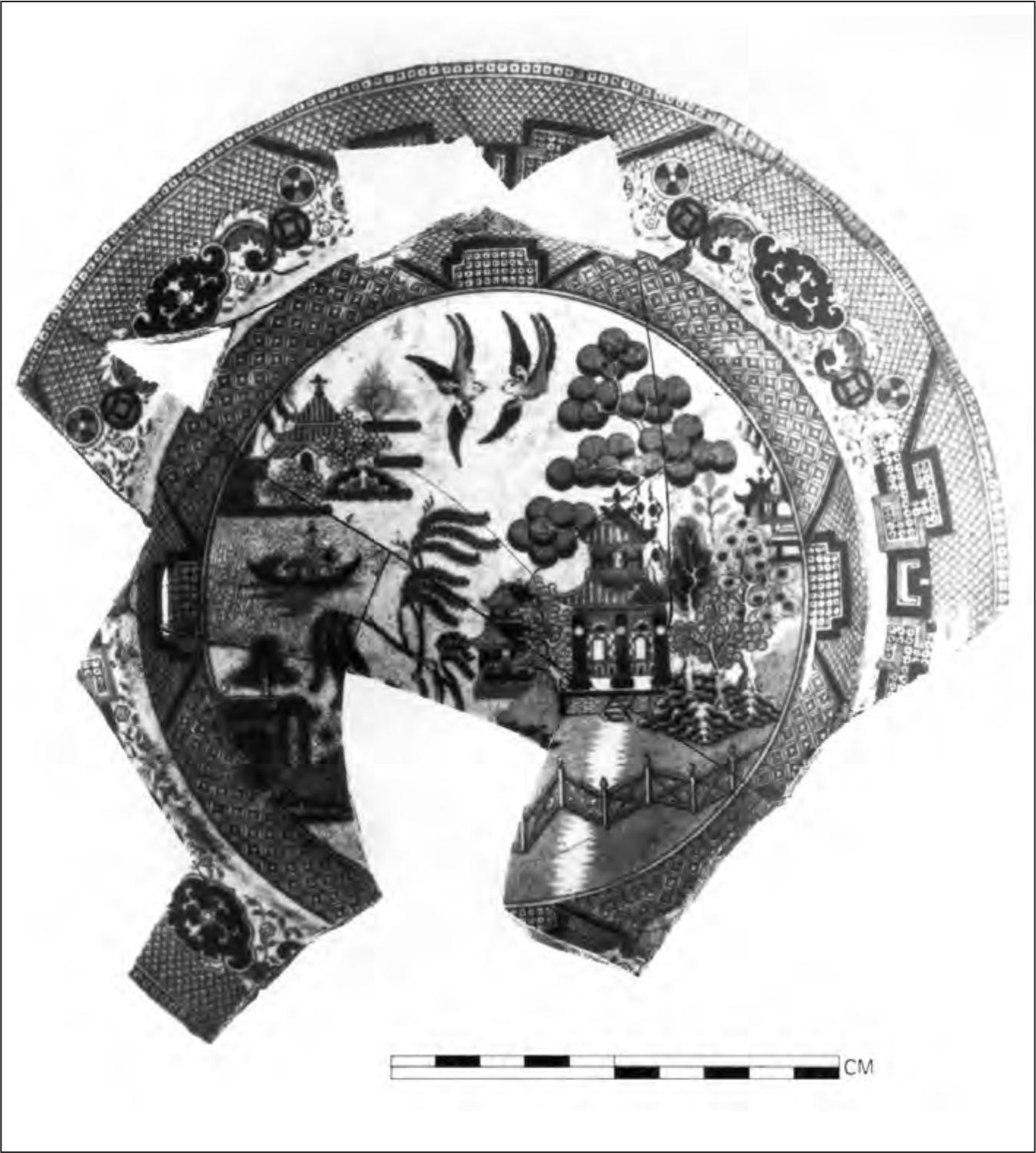

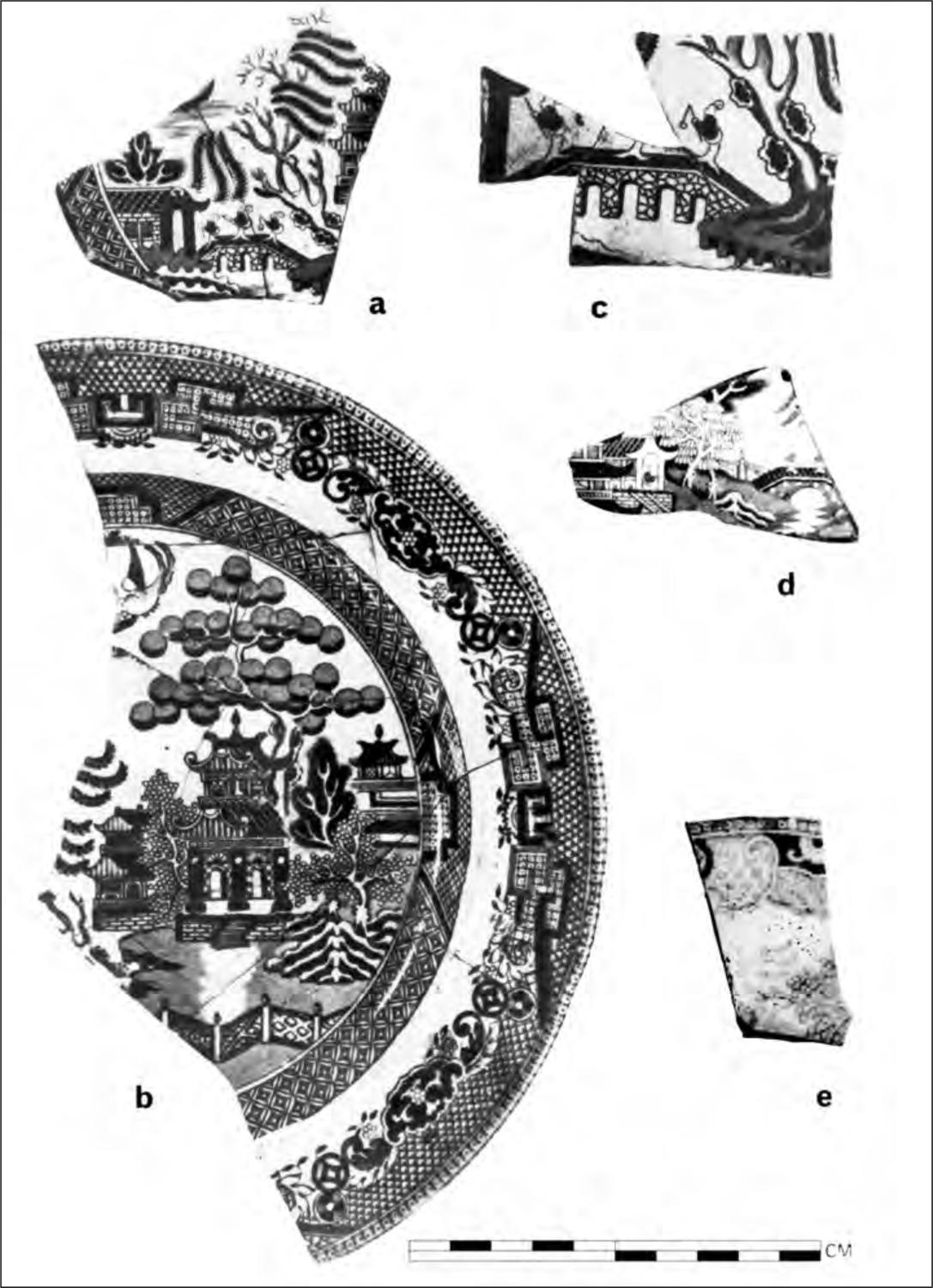

SUB-TYPE AI – BLUE SCENIC TRANSFER WARE (WILLOW PATTERN) – 306 sherds (Items 46–54)

Note: While the Willow Pattern belongs essentially to sub-type AH, it is extremely common in this collection, and since its component motifs are sufficiently distinct for all elements to be related to a single category, it is of more value to treat it separately.

Distribution: VM, VMII, VCC, VQS, VH, VHK, VMQ, VSD, VOM, VSF, VSFII, VCH, VB. Thickness: 3 mm to 6.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colours: BCC 89, BCC 145, BCC 146, BCC 195, BCC 218. Decoration: because of the symbolic and stylistic nature of the pattern, it lends itself to an examination of individual motifs which recur on all examples, and usually in the same place within the pattern. On plates and dishes the decoration can be divided into three registers. The border patterns of plates made during this period are of two main types, the essentially floral border called the ‘mosquito’ pattern, which was represented in the Port Essington collection on three porcelain sherds (see above, Porcelain Type D) and the less artistic and more common ‘Spode’ form which is the only one used on the earthenwares in this collection. It is also known as the ‘wheel’ or ‘wall’ border, and consists of conventional geometric motifs, cross-hatching, dotted circles, formalised floral design, ‘wheels’ and lines reminiscent of fortifications which give rise to the name ‘wall’ border. Within this border is another register of conventional geometric motifs – cross hatching enclosing diamond shapes divided into quarters by more ‘fortification’ patterns. Within these two borders, the legend of the Willow Pattern (Anon. 1963) is represented pictorially by a number of standard motifs: the mandarin’s house, with his wealth represented by the ornate buildings and fruit trees, the fence which separates the lovers, the bridge over which they escape, the house where they hide, the boat on which they escape again, the island where they prosper, again surrounded by fruit trees, and finally after they are again discovered and die, the birds into which they are transformed. While the standardisation of these motifs is extreme, minor differences in the rendition of them might allow future work to date changes in the pattern more effectively.

Figure 65. Port Essington pottery: Blue Scenic Transfer Printed Ware – Willow Pattern.

Item 46 VM/S/I (2) and VM/5/1 (1, 2, 4, 7, 9, 15) and VM/6/1 (3, 11, 20, 26) and VM/7/1 (33, 34) and VM/8/1 (7), Figures 65, 67-c.

Form: plate. Thickness: 4 mm. Rim diameter: 150 mm (100%). Decoration colours: BCC 145, BCC 218. Decoration: the conventional Willow Pattern.

Remarks: this is the most common pattern in the collection. The item is unmarked on the underside except for a small circle of dots with a central dot. This piece, although unmarked, is identical in its representation of motifs to the Spode examples. Apoint which might be of significance is the relationship of the outer and inner registers of geometric patterns. On all the examples in this collection, the lined ‘fortification’ motif in each register is adjacent, one to the other. In an illustrated example of the pattern (Anon. 1963: cover illustration) referred to as the ‘Spode’ pattern, the floral shield device of the outer register is placed opposite the ‘fortification’ motif of the inner register. On a later example examined by me, the two registers have been placed on the plate apparently without regard to each other. In the period of production of the Willow Pattern recovered from Port Essington, however, it is reasonable to assume that the alignment of the two geometric registers followed a conscious style.

Item 47 WK/3/1 (1, 2), Figure 66-a.

Form: plate. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colour: between BCC 89 and BCC 195. Decoration: the motif of the escaping lovers, missing from Item 46.

Remarks: the three figures are the daughter carrying a distaff, emblem of virginity, the clerk carrying the stolen jewels, and the mandarin who pursues them with a whip. This representation, with three figures on a three-arch stone bridge is the most usual representation, and is certainly the most common in the present collection (but see Items 49, 50). Note that while the design is a close imitation of Item 46, a comparison of the trees indicates that it comes from a different engraving.

Item 48 VQS/6/1 (9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19), Figures 66-b, 67-a, 78-g.

Form: plate. Thickness: 5 mm. Rim diameter: 230 mm (50%). Decoration colours: range between BCC 145 and BCC 218. Decoration: conventional Willow Pattern which differs in detail from Item 46. 65

Remarks: the decoration lacks the delicacy of Item 46 both in representation (e.g. compare the bird and the fence) and in the colour of decoration. This is caused by more intense definition of outlines together with a simplification of the pattern, for example the four species of trees about the mandarin’s house in Item 46 are here reduced to two. The peach blossom motif is reduced from a circle of radiating strokes around a central dot to a simple circle. Slight differences can be noted in the outer register of order decoration, where the floral elements are changed and the ‘wheels’ slightly overlap. This Item has a printed mark on the underside of the rim, being a pre-1837 version of the Royal arms with ‘Royal Stone China’ printed below. The piece is unusual (see discussion below) but is best attributed to Hicks, Meigh and Johnson, whose pottery at Shelton is dated 1822-1835.

Item 49 VM/7/1 (72) and VM/9/1 (31) and VM/10/1 (18), Figure 66-c.

Form: plate or platter. Thickness: 4.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 218. Decoration: variation of bridge motif which shows bridge with four (or probably five) arches. The overall pattern is large and the expanded bridge may have been used to fill the area more successfully.

Figure 66. Port Essington pottery: Blue Scenic Transfer Printed Ware – Willow Pattern (a-e).

Item 50 VM/14/1 (30), Figures 66-d, 78-h.

Form: plate. Thickness: 6 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 145 to BCC 146. Decoration: a variation of the Willow Pattern unique in this collection.

Remarks: many differences in the motifs are apparent. The bridge is a single arch, and the representation of it differs from the usual angular lines used to indicate the stones with which it is made. Only two figures are (apparently) represented on the bridge, but an additional figure (the faithful handmaid?) awaits in the lovers’ retreat across the river. In the normal pattern this house is austere in design and has no fruit trees around it, which is a symbolic representation of the story, where the lovers are forced to live in poverty in contrast to the ornate richness of the mandarin’s house and garden on the opposite side of the river. In the present item however the house is architecturally complex and large and a fruit tree is nearby. In general the pattern indicates a significant variation from the traditional pattern, with an attendant loss of meaning. This item has a printed stamp on the reverse side with the words ‘Semi China’ inside a double lined, diamond shaped frame. In the top corner of the diamond is a small rectangle, and in the bottom corner what appears to be a lower case printed ‘l’.

Item 51 VM/7/1 (7), Figures 66-e, 67-d.

Form: bowl or deep plate. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 145. Decoration: variation of the conventional border motif.

Remarks: this rim sherd possibly belongs with Item 50.

Item 52 VM/S/J (18), Figure 67-k.

Form: bowl. Thickness: between 4.5 mm (wall) and 6 mm (base). Base diameter: 80 mm (17%). Decoration colour: BCC 145. Decoration: internal and external Willow Pattern.

Remarks: printed stamp on underside of base similar to Item 50.

Item 53 VM/8/1 (5), Figure 68-l.

Form: large bowl with everted rim. Thickness: 5.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 218. Decoration: internally with the conventional geometric borders, externally with an ‘open’ (borderless) representation of the conventional pattern.

Item 54 VM/S/L (3), Figure 67-p

Form: flanged lid. Thickness: 3.5 mm. Rim diameter: approximately 100 mm (8%). Decoration colour: BCC 44. Decoration: conventional pattern.

Remarks: the colour of decoration of this item is unusual and is the only example in this collection. 66

Figure 67. Port Essington pottery: pottery profiles (2).

Figure 68. Port Essington pottery: pottery profiles (3).

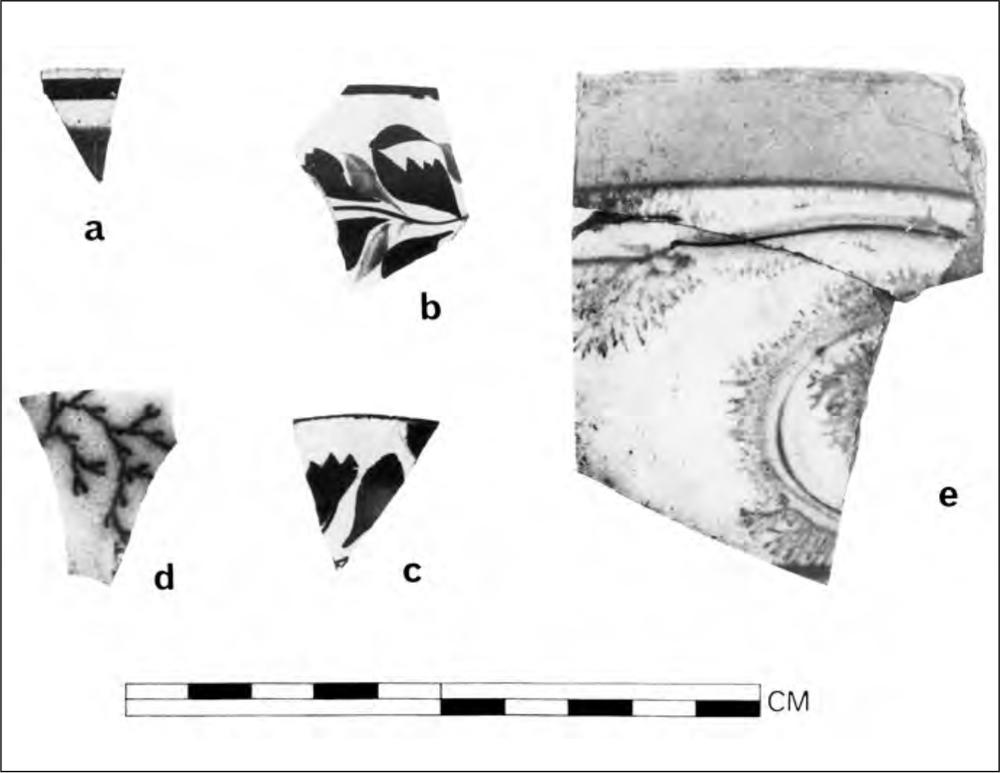

SUB TYPE AJ – BLUE FLORAL TRANSFER WARE – 163 sherds (Items 55-65)

Distribution: VM, VMII. VHK, VSF, VSD, VOM VCC. Thickness: ranges between 2 mm and 11 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colours: BCC 44, BCC 145, BCC 146, BCC 147, BCC149, BCC 194, BCC 196, BCC 197, BCC 218. Decoration: floral decoration includes so large a number of motifs that it is only possible to analyse this broad sub-type in terms of stylistic ranges. Several naturalistic representations on a grand scale (trees and flowering bushes) are possibly sherds from naturalistic scenic decoration. A second small group in the collection consists of the patterns which attempt to reproduce realistic representations of flowers and leaves, where the artist has not only faithfully reproduced the structural nature of the subjects but has also attempted to represent petal and leaf texture. This range of decoration is in every case associated with the ‘closed’ background technique and is in contrast to the largest range of decoration which may be called ‘representational’. Here sufficient detail is used to be able to identify the flower only on occasions. In this latter category an ‘open’ background is most often employed. The result is that despite the lack of detail in this group, its overall appearance is one of lightness, whereas the ‘realistic’ representations are often heavy and florid. This is accentuated by the use of darker blues in the ‘realistic’ group. Finally, this abstraction gradually results in the development of geometric shapes derived from floral inspiration; also such things as scroll leaf motifs are used as borders for more representational floral motifs, and these constitute a geometric/floral group.

The apparent pattern in the relationship between colour intensity and background technique (open versus closed) in these stylistic groups was tested in their percentage distributions, shown in Table 70. While three quarters of the collection comprise ‘open’ backgrounds, this table suggests a correlation between ‘open’ backgrounds and lighter colours and between closed backgrounds and darker colours.

Table 70. Distribution of blue floral decorative styles according to background style and decoration colour (%).

| Open Background | Light (BCC 145) | Medium (BCC146-BCC 195) | Dark (BCC 218) | TOTAL |

| Naturalistic | 1.9 | 3.7 | 5.6 | |

| Realistic | ||||

| Representational | 22.4 | 23.0 | 2.5 | 47.9 |

| Geometric/Floral | 3.1 | 17.4 | 2.5 | 23.0 |

| (subtotal) | (27.4) | (44.1) | (5.0) | (76.5) |

| Closed Background | ||||

| Naturalistic | 0.0 | |||

| Realistic | 0.6 | 5.0 | 5.6 | |

| Representational | 3.1 | 1.9 | 8.7 | 13.7 |

| Geometric/Floral | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 4.3 |

| TOTAL | 31.1 | 47.2 | 21.8 | 100.1 |

The percentage representations of these different styles present in this collection are Naturalistic 5.6%, Realistic 5.6%, Representational 61.5% and Geometric/Floral 27.3%.

Item 55 VCC/GEN SUR (100, 106), Figures 69-a, 68-o.

Form: bowl. Thickness: ranges between 3.5 mm (body) and 9.5 mm (rim). Rim diameter: 240 mm (11%). Decoration colours: BCC 146, BCC 218. Decoration: externally in conjunction with probable scenic motif; internally on rim in a ‘realistic’ motif against a closed background.

Item 56 VM/12/1 (4), Figures 69-b, 68-m.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 4.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: externally on wall and internally on wall and lip 67with a continuous ‘representational’ floral and leaf motif against a closed background.

Remarks: this exact pattern is represented on at least two other vessels in the collection.

Item 57 VMII/1/1 (3, 39), Figure 69-c.

Form: plate or dish. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 145, BCC 146. Decoration: ‘representational’ thistle pattern against an open background.

Item 58 VM/6/1 (1), Figure 69-d.

Form: steep angular vessel, possibly cup. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 145, BCC 146. Decoration: internal and external ‘representational’ flower and leaf pattern against an open background.

Item 59 VCC/GEN SUR (109), Figures 69-e, 68-i.

Form: deep plate or bowl. Thickness: between 2.5 mm (body) and 5.5 mm (rim).

Decoration colours: BCC 145, BCC 196.

Decoration: ‘representational’ leaf pattern overlain by a geometric spiral of small oval dots, against an open background.

Item 60 VM/13/1 (4), Figures 69-f, 67-i.

Form: shallow bowl. Thickness: between 3.5 mm (base) and 5.5 mm (wall). Decoration colour: BCC 194. Decoration: negative floral design of the ‘representational’ type against a closed background of hatched diamonds which diminish in size from the rim inwards.

Item 61 VCC/GEN SUR (116), Figure 69-g.

Form: deep plate or bowl. Thickness: 5 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 147, BCC 194. Decoration: ‘representational’ floral motif on an open background with some areas closed. Several flowers are abstracted to a degree where they are represented as circles with radiating ovals as petals.

Remarks: this style is not common in the collection.

Item 62 VM/S/J (12), Figure 69-h.

Form: shallow bowl. Thickness: 5 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 145, BCC 149. Decoration: ‘geometric/floral’ leaf motif against a closed background together with a regular pattern of asterisks. Below this another register of the leaf motif begins.

Remarks: this pattern is common in the present collection.

Item 63 VMII/1/1 (14, 48), Figures 69-i, 67-j.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 2.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 44. Decoration: internal and external ‘geometric/floral’ motif against an open background.

Item 64 VM/9/1, Figure 69-j.

Form: cup. Thickness: 3.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 145. Decoration: internal and external motif of clusters of fruit or blossom against an open background.

Item 65 VHK/3/1 (17, 18), Figures 69-k, 68-e.

Form: steep-sided bowl. Thickness: between 3.5 mm (rim) and 5.5 mm (body). Rim diameter: 160 mm (15%). Decoration colours: BCC 145, BCC 197. Decoration: complex ‘geometric/floral’ motifs. The floral motifs are against an open background and are both of standard representational form and also in some instances stylised. The geometric motifs range from complex forms with obvious floral inspirations to simple cross-hatched diamonds.

Figure 69. Port Essington pottery: Blue Floral Transfer Printed Ware (a-k). 68

SUB-TYPE AK – BLUE GEOMETRIC TRANSFER WARE – 98 sherds (Items 66–71)

Distribution: VM, VMII, VQS, VOM, VCC. Thickness: 2.5 mm to 11 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colours: BCC 89, BCC 145, BCC 149, BCC 195, BCC 218. Decoration: the use of pure geometric design as decoration in this collection is relatively rare, and although 98 sherds are included in this category some of these undoubtedly belong to patterns of which the geometric motifs are only subsidiary. Of the designs in which the geometric elements form the dominant motif all are covered by the items listed below.

Item 66 VQS/3/1 (16, 18) and VQS/4/1 (31) and VQS/6/1 (21, 22), Figure 70-a.

Form: plate? Thickness: 5.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC149. Decoration: large central dot with twelve radiating irregular diamond shapes.

Remarks: Impressed asterisk on underside.

Item 67 VM/9/1 (13), Figure 70-b.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 3.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 195. Decoration: continuous curved lines with dotting and cross-hatching on the lip. A flower motif also occurs on this item, and others with similar decoration, which is common in this collection. However, the geometric motif makes this ware more easily recognisable.

Item 68 VM/7/1 (69) and VM/9/1 (9) and VM/10/l (46) and VM/12/1 (1) and VM/13/1 (14) and VM/14/1 (18, 28, 31), Figures 70-c, d, 67-w, 78-i.

Form: steep-sided bowl. Thickness: Between 0.35 mm (base) and 0.75 mm (wall). Base diameter: 8 mm (35%).Decoration colours: BCC 145, BCC 149. Decoration: internally on base with complex star pattern, and on internal and external walls with alternating vertical registers of multiple chevrons and a simple geometric motif of dotted circles and scrolls.

Remarks: on underside of base is a fragmentary printed mark consisting of a crown above a scroll on which is written ‘VIC….’ (possib1y ‘VICTORIA’).

Item 69 VMII/1/1 (10), Figure 70-e.

Form: plate. Thickness: 5.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: internally on rim, solid bands of colouring and immediately below this a register of dotted arches and crosses. Where the rim curves into the body a single line runs around the body.

Item 70 VMII/1/1 (19), Figures 70-f, 68-b.

Form: cup? Thickness: 2.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 89. Decoration: internally and externally on the rim with a continuous geometric leaf pattern.

Item 71 VCG/GEN SUR (118), Figures 70-g, 68-p.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 8 mm (body) to 11 mm (rim). Decoration colour: BCC 218. Decoration: on top surface of rim and internally complex ‘geometric/floral’ motif against a closed background.

Figure 70. Port Essington pottery: Blue Geometric Transfer Printed Ware (a-g).

TYPE B – GREEN FEATHEREDGE WARE – 11 sherds (Item 72)

Distribution: VM, VMII. Thickness: 4 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC.I. Decoration colour and Decoration: uniform for this type – see Item 72.

Remarks: the only shapes represented are wavy-edged plates.

Item 72 VM/10/1 Figure 71-a.

Form: plate. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 105. Decoration: irregular incised lines running from rim towards centre for a distance of 10 mm to 15 mm. The colour is applied under the glaze and is caught in the incised grooves. 69

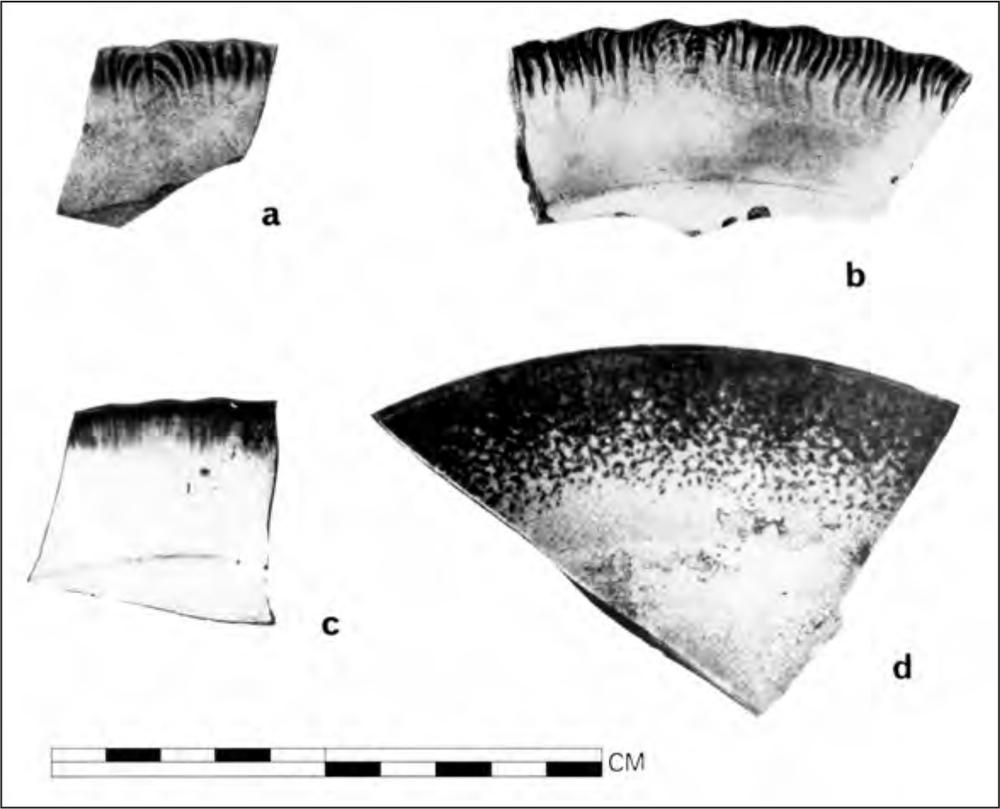

Figure 71. Port Essington pottery: Green Featheredge Ware (a); Blue Featheredge Ware (b-c); Blue Spatterware (d).

TYPE C – BLUE FEATHEREDGE WARE – 8 sherds (Items 73–74)

Distribution: VM, VHK, VSD, VCC. Thickness: 3.5 mm to 5.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: as in TYPE B, with blue instead of green. The exception is Item 74.

Remarks: wavy-edged plates only.

Item 73 VM/S/H (2), Figure 71-b.

Form: plate. Thickness: 5.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 149 Decoration: as in Item 72.

Item 74 VM/S/C (2), Figure 71-c.

Form: plate. Thickness: 4.5 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: variant of Item 73.

Remarks: the wavy edge is less pronounced and the incised lines are finer.

TYPE D – BLUE SPATTER WARE – 17 sherds (Item 75)

Distribution: VMQ, VQS, VCC. Thickness: 4 mm to 6 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colour: BCC 146. Decoration: a variant of the featheredge types, where the decoration is applied to the upper face of the rim only. No incision is used and the colour is ‘spattered’ or sponged on to the surface, producing a mottled effect.

Remarks: all items in this category are uniform. In contrast to the featheredge wares, all items are straight-edged plates.

Item 75 VCC/GEN SUR (33), Figure 71-d.

Form: plate. Thickness: 6 mm. Rim diameter: 240 mm (15%). Decoration colour and Decoration: as described in the general description for this type.

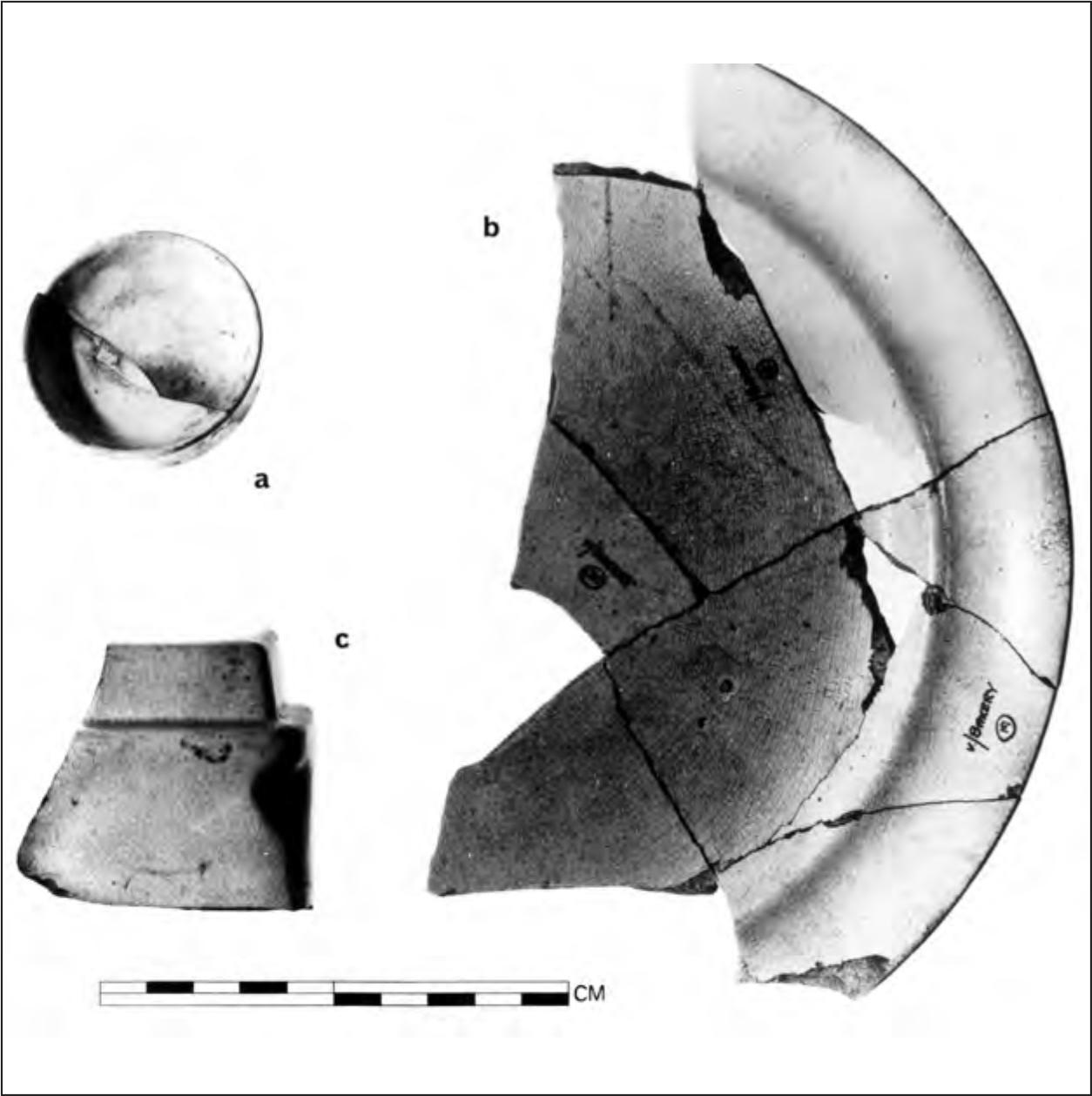

TYPE E – UNDECORATED WHITE GLAZE WARE – 380 sherds (Items 76–83)

Distribution: VM, VMII, VH, VHD, VHK, VMQ, VQS, VSD, VSF, VCC, VB, VCH, VAM. Thickness: 2 mm to 6 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1, BCC 2.

Item 76 VHD/DRAIN (1, 2, 3), Figure 72-a, 67-q.

Form: pestle or palette. Thickness: 2 mm (base). Diameter: 53 mm (100%).

Remarks: stands 10 mm high.

Item 77 VB/SUR (11, 12, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21), Figures 72-b, 67-b.

Form: plate. Thickness: 4.5 mm (base) to 5.5 mm (rim). Rim diameter: 240 mm (34%). Base diameter: 140 mm (50%).

Item 78 VHK/2/1 (9), Figure 78-j

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 4 mm.

Remarks: carries an impressed mark ‘HACKWOOD’, identified as William Hackwood of Hanley (1827–43). This is the only marked item in this category.

Item 79 VH/GEN SUR (1), Figures 72-c, 68-g.

Form: square canister. Thickness: 4.5 mm (body).

Remarks: internal flange to hold lid, and indentation at corner, apparently to facilitate holding the vessel. Height of flange above shoulder: 16.5 mm. This is a large example of a number of similarly shaped canisters in this collection.

Item 80 VM/7/1 (35), Figure 68-h.

Form: vertical vessel, possibly cup or mug. Thickness: 4 mm. Rim diameter: approximately 100 mm (5%).

Item 81 VCC/GEN SUR (III), Figure 67-g.

Form: dish or shallow bowl. Thickness: 4 mm.

Item 82 VCC/GEN SUR (11), Figure 68-w.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 3 mm (body) to 8.5 mm (rim).

Item 83 VMII/2/1 (4), Figure 67-l.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 2.5 mm (base) to 4 mm (wall). Base diameter: 80 mm (15%).

Figure 72. Port Essington pottery: Undecorated White Glaze Ware (a-c). 70

TYPE F – LINE DECORATED WARE – 6 sherds (Item 84)

Distribution: VHK, VCC. Thickness: 3.5 mm to 5.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colours: BCC 19, BCC 44, BCC 188. Decoration: horizontal bands of colour applied under the glaze.

Item 84 VHK/2/1, Figure 73-a.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colour and Decoration: as described in the general description for this type.

TYPE G – HAND PAINTED WARE – 12 sherds (Items 85–86)

Distribution: VM, VMII, VHK, VQS, VCC. Thickness: 2 mm to 3 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 1. Glaze colour: BCC 1. Decoration colours: BCC 24, BCC 38, BCC 46, BCC 103, BCC 149, BCC 220. Decoration: a floral motif is used on all items. Five items are painted in a single colour under the glaze, six items in two colours under the glaze, one item has three underglaze colours and the remaining item has one colour applied under the glaze, and a second above the glaze.

Item 85 VQS/4/1 (32), Figure 73-b

Form: cup? Thickness: 0.3 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 38, BCC 103, BCC 220. Decoration: a single black line internally and externally on the rim; externally, a floral motif.

Item 86 VMII/2/1 (10), Figure 73-c.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 3.5 mm. Decoration colours: BCC 24, BCC 149. Decoration: underglaze and overglaze floral motif.

TYPE H – FLOWING BLUE WARE – 1 sherd (Item 87)

Item 87 VCG/GEN SUR (67), Figure 73-d.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 4 mm. Decoration colour: BCC 149. Decoration: internal and external ‘tree’ motif executed in a single dotted line.

Remarks: the colour of the decoration has ‘flowed’ to the extent of discolouring the surrounding glaze.

Figure 73. Port Essington pottery: Line Decorated Ware (a); Hand Painted Ware (b-c); Flowing Blue Ware (d); Mocha Ware (e).

GROUP 2 – THE COLOURED CLAYWARES

This group includes all earthenwares represented in the collection not included in the white clay wares. Some, such as the salt glaze stoneware, are of a hard paste variety. Others are soft paste. Both British and Asian wares are included here.

TYPE A – MOCHA WARE – 14 sherds (Items 88–89)

Distribution: VM. Thickness: 3 mm to 9 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 165. Glaze colours: BCC 1, BCC 233. Decoration colour: BCC 45. Decoration: for a detailed description of the method see Godden (1963:142-4). Briefly, a tree-like effect is produced by the chemical reaction of an acid colourant on an alkaline slip.

Remarks: the 14 sherds of this type possibly belong to the same vessel. This ware, first produced in the eighteenth century, was in production at the Copeland Works in 1852, where it was noted by Charles Dickens (Godden 1963:143).

Item 88 VM/GEN SUR (3, 11), Figures 73-e, 68-d.

Form: bowl. Thickness: 5 mm (wall) to 9 mm (rim). Rim diameter: approx. 260 mm (6%). Decoration colour: BCC 45. Decoration: external only. The decoration is contained in a register around the wall of the vessel.

Item 89 VM/GEN SUR (6), Figure 67-m.

Form: base sherd of Item 88. Thickness: 3 mm (base) to 7.5 mm (lower wall). Base diameter: 140 mm. Decoration colour and Decoration: see Item 88.

TYPE B – UNGLAZED WHEELMADE WARE – 30 sherds (Items 90–91)

Distribution: VM, VMII, VH, VMQ. Thickness: 2.5 mm to 9 mm. Fabric colour: BCC55, BCC 133.

Remarks: all the sherds in this group are wheel-made and all except three are of a dark, thin, hard-fired nature, quite unlike the unglazed South East Asian wares. The remaining three sherds are of extremely porous, soft fabric and possibly relate to what were known as ‘water monkeys’ – containers through which the water could seep and evaporate on the external face thus keeping the water inside at a lower than surrounding air temperature. It is possible that this unglazed earthenware was not of English manufacture but no evidence exists to decide the point.

Item 90 VM/S/E (8, 13), Figure 60-p.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 5.5 mm. Base diameter: 120 mm (25%). Fabric colour: BCC 133.

Item 91 VH/S/R (3), Figure 60-q.

Form: indeterminate, possibly dish or bowl. Thickness: 7 mm (base) to 9 mm (wall). Base diameter: approx. 220 mm (6%). Fabric colour: BCC 133.

TYPE C – SALT GLAZE STONEWARE – 170 sherds (Items 92–99)

Distribution: VM, VH, VSD, VMQ, VSF, VOM, VCC, VB, VAM II. Thickness: 5 mm, to 15.5 mm. Fabric colours: BCC 2, BCC 3, BCC 187. Glaze colours: BCC 29, BCC 60, BCC 61, BCC 64, BCC 66, BCC 67, BCC 72, BCC 73, BCC 76, BCC 136, BCC 138, BCC 204, and BCC 205. Decoration: any decoration is found mainly on the jars 71and consists usually of one or more incised lines running horizontally around the shoulder of the pot, although similar lines can occur around the body in the centre and towards the base. It is common for the mouth, neck and shoulder to be glazed a darker colour than the body. Of the jars, all examples are glazed on the internal face; examples of both glazed and unglazed interior surfaces of bottles are present.

Remarks: vessel shapes are confined to inkwells, bottles and open mouthed jars.

Item 92 VM/S/E (4) and VM/8/1 (42), Figures 74-a, 75-a.

Form: jar. Thickness: 7.5 mm (body) to 15.5 mm (neck). Glaze colour: external BCC 73, BCC 136; internal BCC 66, BCC 76. Rim diameter: 150 mm (50%+) approx. body diameter: 250 mm. Decoration: three incised rings on shoulder.

Item 93 VM/S/E (3), Figure 75-b.

Form: jar. Thickness: 6 mm. Rim diameter: 150 mm (26%). Glaze colours: external BCC 60; internal BCC 204.Decoration: the shoulder line in this item has a distinct ridge.

Item 94 V/GEN SUR /67 (27), Figures 74-b, 75-c.

Form: bottle. Thickness: 4.5 mm. Rim diameter: 23 mm. Glaze colour: BCC 138.

Remarks: unglazed internally.

Item 95 VAMII/2/2 (1), Figure 74-c.

Form: bottle. Thickness: 0.75 mm. Glaze colour: BCC 61.

Remarks: this item has a high, even glaze. While it was in a sealed deposit in association with material associated with the 1840s settlement, the ware is much more similar to the salt glaze bottles of the later nineteenth century. Therefore the authenticity of this item is uncertain.

Figure 74. Port Essington pottery: Salt Glaze Stoneware (a-f).

Item 96 VMQ/1/1 (21 & 23) and VMQ/6/1 (11) and VMQ/32/1 (27) and VMQ/32/2 (4), Figures 74-d, 75-g.

Form: bottle. Thickness: 4 mm (base) to 8 mm (body). Base diameter: 90 mm (50%). Glaze colour: BCC 67.

Remarks: the surface is extremely uneven, and is unglazed internally.

Item 97 VCC/GEN SUR (1), Figures 75-d, 75-g

Form: bottle. Thickness: 6.5 mm. Base diameter: 90 mm (35%). Glaze colour: BCC 204.

Remarks: unglazed internally, external surface uneven.

Item 98 VCC/GEN SUR (3), Figures 74-e, 75-d.

Form: inkwell. Thickness: 4 mm (base) to 6 mm (body). Base diameter: 55 mm (50%). Height from base to shoulder: 40 mm. Glaze colour: BCC 205.

Remarks: unglazed internally.

Item 99 VOM/6/1 (7), Figures 74-f, 75-f.

Form: inkwell. Thickness: 3 mm.(base) to 10 mm (body). Base diameter: 45 mm (50%). Glaze colour: BCC 67.

Remarks: unglazed internally. The body has been flaked to form an Aboriginal artefact.

Figure 75. Port Essington pottery: Salt Glaze Stoneware profiles.

TYPE D – MACASSAN WARE – 8 sherds (Items 100–101)

Distribution: VMII, VH, VQS, VCC. Thickness: 3.5 mm to 15 mm. Fabric colours: BCC 58, BCC 59, BCC 72, BCC 204. Decoration: although formal decoration can occur on this pottery it is infrequent and is not present in this collection. Several items bear traces of slip and one rim (Item 100) has thumb impressions on the underside that does not reflect formal decoration.

Remarks: from work carried out on Macassan sites in north Australia by Campbell Macknight (1969), the most common 72shape in this ware appears to be a large globular pot with everted rim. The only recognisable vessel shapes in the present collection came from such globular pots.

Item 100 VCC/GEN SUR (202), Figures 76-a, 60-r.

Form: globular pot. Thickness: 9.5 mm to 15 mm. Rim diameter: 240 mm (10%). Fabric surface colour: BCC 59. Decoration: some traces of slip on surface. Underside of rim has thumb impressions.

Item 101 VMII/3/1 (16)

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 4.5 mm to 5.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 204.

Remarks: spectroscopic analysis (by C. Key, Dept. of Anthropology, ANU) of this item revealed that the filler consisted almost entirely of shell and coral particles. Although this particular type of ware occurs on Macassan sites in north Australia it is not common (Campbell Macknight pers. comm.).

TYPE E – RIM GLAZED STONEWARE – 7 sherds (Item 102)

Item 102 VSD/1/2 (3), Figures 76-b, 60-s.

Form: globular bowl. Thickness: 2.5 mm to 4.5 mm.

Rim diameter: 120 mm (10%). Fabric colour: BCC 133. Glaze colour: BCC 70. Decoration: band of salt glaze on lip and upper body.

Remarks: probably of S.E. Asian provenance.

TYPE F – NGA-KWUN WARE – 1 sherd (Item 103)

Item 103 VSF/10/1 (5).

Form: indeterminate, but possibly open-mouthed jar. Thickness: 5.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 7. Glaze colour: BCC 140. Decoration: glazed internally and externally.

Remarks: this ware is identical to that of two squat, flat-based jars, one an open-mouthed jar collected at Yam Creek, a Northern Territory goldfield dating to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the second an open-mouthed jar photographed at a deserted farm house site on the south coast of New South Wales, imprecisely dated from other finds to the beginning of this century. These jars are a common household ware used mainly to contain salted vegetables and are still in use in China and Taiwan (pers. comm. N. Barnard, Dept of Far Eastern History, ANU). The name used here is from the Cantonese name for the ware.

UNIDENTIFIED POTTERY – 25 sherds (Items 104–106)

Amongst the unidentified sherds, three items are worthy of note.

Item 104 VM/7/1 (70) and VM/9/1 (47, 48), Figures 76-c, 60-v.

Form: lid. Thickness: 2 mm (roof) to 8.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 165. Glaze colours: BCC 1, BOC 27.

Decoration: glazed on external surfaces only. The attempt to glaze has resulted in a thick, opaque surface coating which has not fused with the surface. Wheel made.

Item 105 VCC/GEN SUR (35), Figure 76-d.

Form: indeterminate. Thickness: 6.5 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 159. Internal glaze colour: BCC 232. External glaze colour: BCC 70.

Remarks: this item is unlike anything in the collection, being of finer quality than the usual stone wares. The glaze is very ‘glassy’ and is not unlike the so-called ‘Rockingham’ ware from England, although it does not have the unevenness of the glaze of that ware.

Item 106 VMQ/1A/1 (1), Figures 76-e, 60-t.

Form: dish or bowl. Thickness: 10 mm. Fabric colour: BCC 204. Base diameter: 160 mm (15%).

Remarks: spectrographic analysis of this item revealed the composition of the ware as fine-grained purified clay, fused material (glass), and some sand and quartz grains. The implication is that the technical level of manufacture precludes it from being labelled primitive pottery. However, the surface finish is very coarse. The interior of the vessel has been badly discoloured by containing pitch, which has permeated the fabric to a depth of 4 mm.

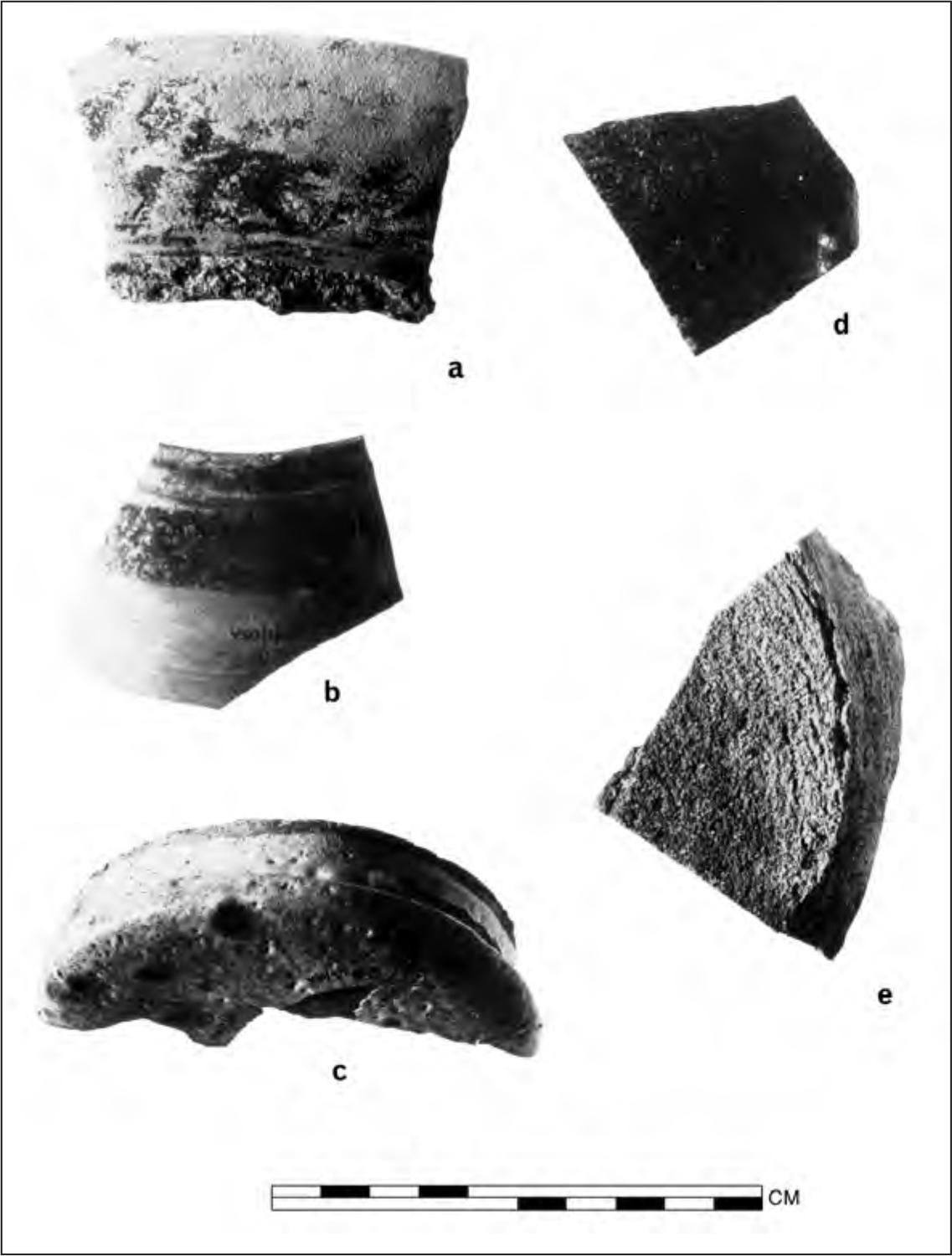

Figure 76. Port Essington pottery: Macassan Pottery (a); Rim Glazed Stoneware (b); Unidentified Pottery (c-e).

DISCUSSION

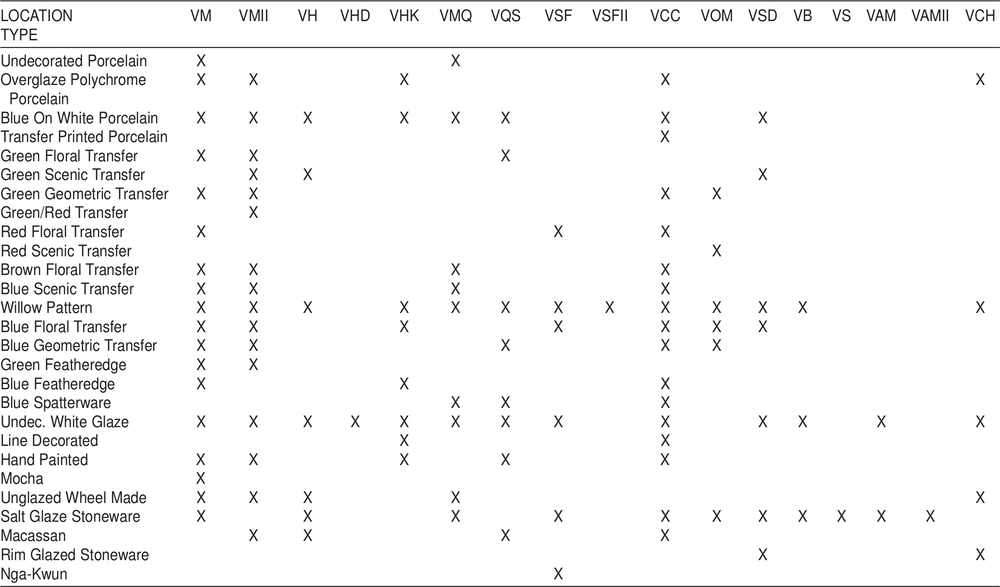

Table 71 shows the distribution of types throughout the settlement at Port Essington. As might be expected the areas where the greatest numbers of types are found together are also the areas which produced the greatest numbers of sherds. These are the three dump areas VM, VMII, and VCC. Apart from these areas the pottery appears to be distributed at random in the settlement and no valid inferences could be drawn from type distribution. Similarly, house function inferences drawn from pottery are possible only in terms of volume, and when taken in association with other artefacts. 73

Table 71. Distribution of pottery types at Port Essington. X = present.

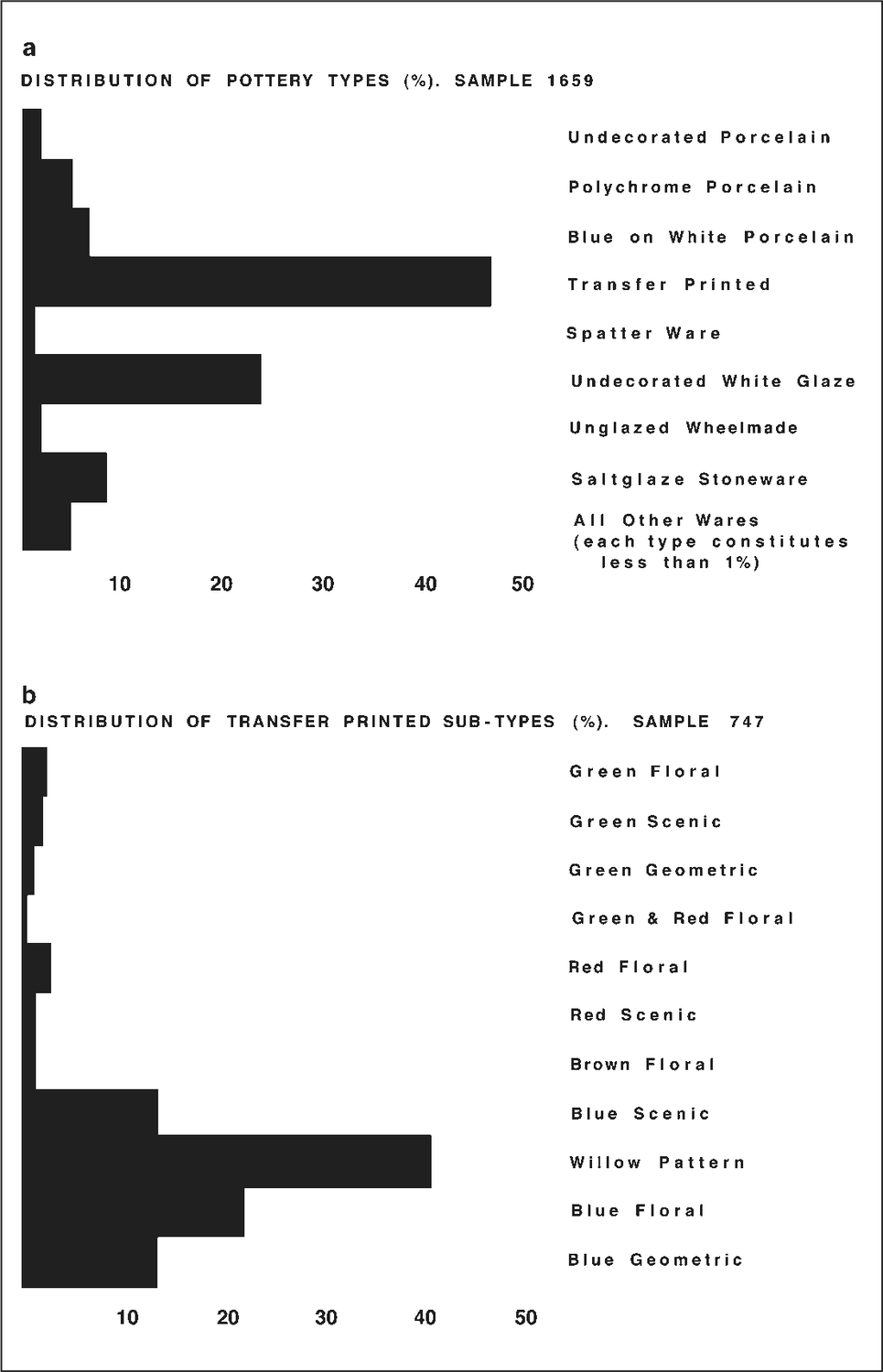

Figure 77a shows the relative proportions of types within the collection. The white clay wares constitute 73.9% of the collection, the porcelain 14.1%, and the remainder 12%. Almost all of the porcelain can be classed as being of mainland South East Asian and probably Chinese manufacture. Two sources of entry for Chinese wares into Port Essington were the Macassan trepang fishermen and traders from Singapore or Canton/Hong Kong. The latter source is more probable on several grounds. Firstly, porcelain on Macassan sites in Australia makes up only a small portion of the total pottery assemblages, and amongst the porcelain found on these sites, the overglaze polychrome decorated type is extremely rare, the bulk consisting of blue on white ware. Of the porcelain in the present collection both types are present in almost equal proportions and together they represent 178 sherds (as well as 39 pieces of undecorated porcelain), compared with only seven pieces of Macassan pottery. Secondly, brief mention is made in the historical records to traders coming from Asia (Earl 1846:67). The relevance of the archaeology is vividly demonstrated here, for the percentage of these wares is quite significant, and these are the archaeological expression of a trade that probably formed a significant part of the economy of the settlement. This fact is not apparent in the historical record.

Of the white clay wares, 63.2% are the transfer printed wares which form the single largest group (46.7%) of the total collection. Excluding the undecorated white glaze ware, the remaining white clay wares constitute less than 5% of this group. Referring to Figure 77b, it will be noted the blue transfer wares constitute 89.8% of this type and that a single pattern, the Willow Pattern, alone represents 40.9% of the transfer printed type. These appear to be the important type distribution patterns which emerge from the analysis.

Figure 77. a) Distribution of pottery types at Port Essington by percentage; b) distribution of transfer printed sub-types at Port Essington by percentage. 74

Shape

In addition to suggesting overall form, some attempt has been made in the classification to record both thickness ranges and shapes. Because of the complete lack of comparative literature this has been done in the hope of assisting future workers rather than contributing to the close analysis of the present collection. However, some general trends have been noted.

1. Thickness varies considerably on individual items. While the Chinese wares are often thickest at the base with body walls thinning towards the rim, the English wares are often thinnest at the base, having thicker walls and rims.

2. Amongst the English white clay wares, the various categories of shapes show generally a high conformity. Thus featheredge plates all have wavy rims, and spatterware plates have straight rims. However, in profile (Figure 67-a-e) the plate shows a general standard form.

3. Of the English glazed wares, all plates, dishes and bowls have a ring foot with a single exception (Item 44, Figure 67-f). On shallow dishes and plates this foot is small, on bowls it is larger- and angled outwards. On the other hand, the ring foot on the Chinese bowls is more perpendicular. (Compare Figures 67-a-n and 60-h-o).

4. Bowl rims are either straight, or more commonly everted. On large bowls the everted right-angle rim is the most common, and this rim is often thick in comparison to the vessel wall.

5. The salt glaze wares are restricted to open-mouthed jars, bottles and ink-wells.

6. Angularity (Figure 67-m) and distortion of shape are not common characteristics in this collection.

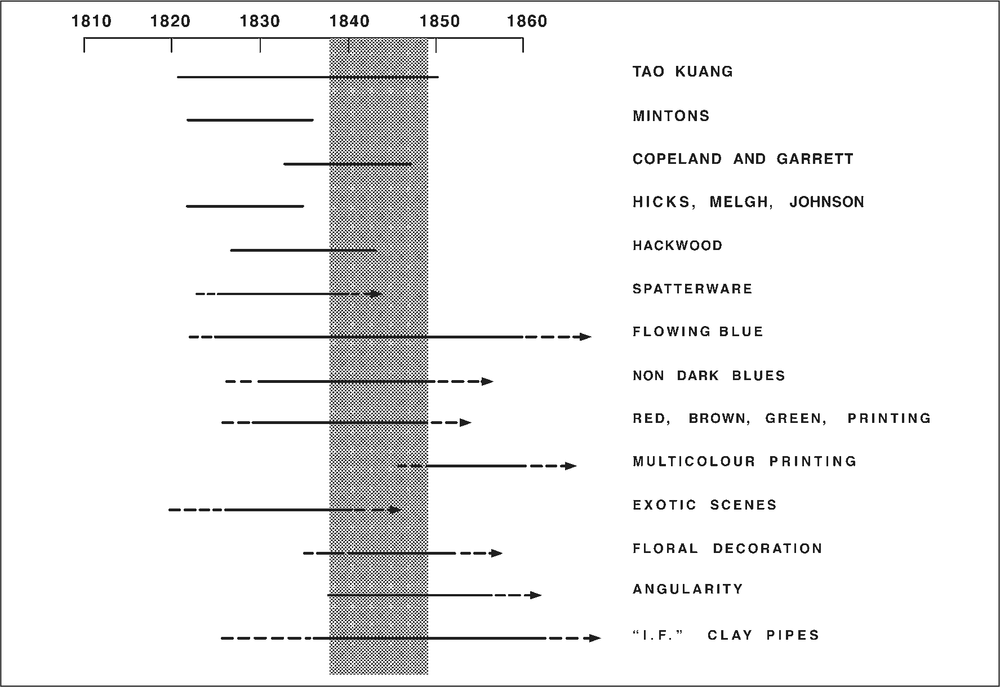

Dating the pottery

Several methods are available for prescribing date ranges for nineteenth century ceramics. Where specific marked items are present good information exists from trade directories giving the life spans of the manufacturing companies and their wares. In addition, potteries frequently altered their marks so that in some instances specific periods within a firm’s life can be isolated on this basis. Certain designs enjoyed only relatively brief popularity and these ranges can be estimated, while technical innovations were sometimes noted in the historical record, so that starting and end dates can be established. It can be expected that future research on the interaction of these aspects will result in the formulation of a closer chronology, which will necessarily result in changes to the basic classification attempted here. Pilling (nd:63, table 1) has already begun to explore along these lines.

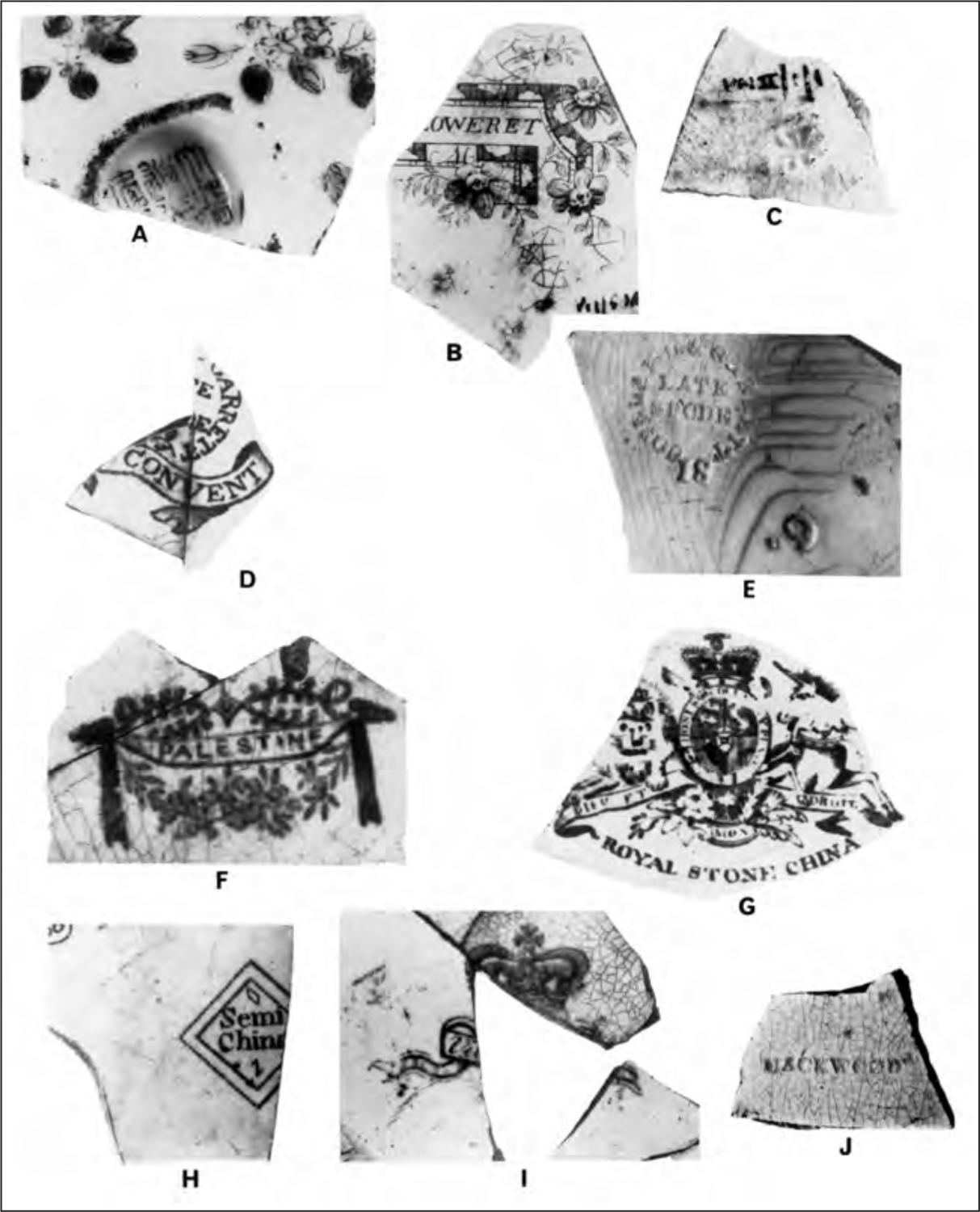

Marked Items (Figure 78)

Eleven marked items are present in the collection and general descriptions are contained in the typology. Of these, Items 30, 39 and 40 belong to the firm of Copeland and Garrett (c.1833–47). The marks closely resemble two marks recorded in the Stoke-on-Trent Museum (Anon. nd:58, nos. 1889, 1943) and are similar to Godden’s nos.1092 and 1093 (1964:173). Two patterns relating to this firm, ‘Venice’ and ‘------- Convent’ are recorded in the collection. In addition, Items 50 and 52 possibly relate to this firm. A similar printed mark, ‘semi china’ in a double-lined diamond is recorded at Stoke-on-Trent, and attributed to Spode and Copeland (Anon. nd:41, no. 272). It is possible that the use of this mark, with the additions recorded here, was carried on when Copeland and Garrett took over the factory.

Three other Staffordshire firms can be identified, William Hackwood of Hanley, 1827–43 (Item 78), Thomas Minton, 1822–36 (Item 25) and Hicks, Meigh and Johnson, 1822–35 (Item 48). The item relating to this latter firm bears a pre-Victorian Royal Arms mark with inescutcheon and crown (an indicator of the period 1814–1837) and is inscribed ‘Royal Stone China’. Godden (1964:11) suggests that the use of the word ‘Royal’ in the manufacturer’s title usually indicates a date after 1850, which of course is impossible in conjunction with this particular Royal Arms mark, and the terminal date for the settlement. Although no maker’s name appears, it is best attributed to Hicks, Meigh and Johnson, who manufactured ‘stone china’ under a Royal Arms Mark (see Godden 1964:323, no. 2022).

Of the Chinese porcelains, Item 8 bears the date mark of the Emperor Tao Kuang (1821–50).

Type Ranges

In the present collection, the transfer printed wares offer the best possibilities for demonstrating the dating value of technical innovations.

Figure 78. Pottery marks present at Port Essington: a) Item 8; b) Item 25; c) Item 30; d) Item 39; e) Item 40; f) Item 43; g) Item 48; h) Item 50; i) Item 68; j) Item 78.

75Shaw (nd) includes a description of the transfer printing technique taken from a manuscript written by W.R. Ball of Deptford Pottery:

First the copper plates are heated, then the colouring is smeared over the engraving with a palette-knife, after which it is scraped off; the plate then being rubbed with a pad made from corduroy so as to remove any surplus. Next, damp tissue paper is placed on the plate which is then run several times through a heavy metal rolling press (much the same in design as an oldfashioned mangle), the rollers being covered with two or three layers of very thick felt. Then the plate is again placed upon the hot stove. This dries the paper which is then removed, leaving the imprint from the copper plate on it, then placed on the pottery which is sometimes in the biscuit, but more often in the glazed state; next we require a rubber, this being made by rolling felt round and round until it is about 21 inches in diameter, and 6 inches long, this being used to transfer the design from the paper to the pottery by rubbing, after which they (the pieces) are placed in a bath of water, to soften the paper which is then easy to remove. Next we have to place the ware in a kiln or oven so as to remove all traces of oil from the print, and at the same time make it adhere firmly to the articles, after which it is often painted by hand, then again placed in the kiln. In the case of articles such as a glass rolling-pin they are printed, painted, then varnished.

Printing on pottery had been introduced in England in the 1750s, but the Staffordshire utilitarian transfer printed earthenwares did not become a major production until the period 1780–1820, during which patterns imitated the Chinese Nankin wares being imported into Europe in this period. The Willow Pattern is an example (although its popularity has lasted long past 1820). From about 1810 Staffordshire manufacturers began producing English subjects, views and events, and even special patterns (as did the Chinese on their export porcelain) for export to America.

Writing in 1829, Simeon Shaw noted the recent introduction of red, brown, and green colours for printed decoration (Godden 1964:149), but Honey (1965:224-5) places this later, in the 1830s. Multicoloured printing began in the late 1840s. Between 1820 and 1840 a whole ranges of romantic and exotic scenes were used as decoration, often bordered with floral shell and geometric motifs, but these appear to have gone out of fashion during the 1840s, when floral motifs became popular. Since only the major firms employed their own engravers, the smaller potters were mostly supplied with their engraved designs by the larger firms (Godden 1964:151-2). This fact provides perhaps the best reason for attempting to set up typologies in terms of patterns and motifs, but see Dollar (1967:41, fn 18) for a different view.

In the first half of the nineteenth century many Staffordshire manufacturers continued to experiment at producing durable wares for these utilitarian manufactures, which would serve as a cross between earthenware and porcelain. Josiah Spode produced his variety of ‘stone-china’ in 1805. An early famous ware of this type was Mason’s ‘ironstone’, patented in 1813. Numerous trade names of similar wares can be located such as ‘New Stone’, ‘Semi China, ‘Semi Porcelain’ et cetera. In general, these labels have little specific dating value unless directly associated with a particular manufacturer.

As mentioned, the Willow Pattern was created as an imitation of the Nankin wares. Honey (1933:190) credits ‘the young Thomas Minton’ with this creation. If correct, this would place its invention back into the eighteenth century, thus reducing its value as a datable type. However it is interesting to note that this type does not occur in the pottery collections from Fort Dundas or Raffles Bay, yet after a 10 year interval between 1829 and 1839 it is the predominant type at Port Essington. The implication that it may not have been an important export ware until after 1830 should be examined in future excavated collections. Information from American sites is too fragmentary to decide this point at present.

The proportional values of the scenic and floral types appear to support the historical trends suggested above.

The technical advances in coloured transfer printing appear to provide good dating evidence. Because cobalt was the surest colour to minimise firing failures in early mass produced pottery, this colour was predominant in transfer printing until 1840. This fact is reflected in the Port Essington collection, where blue represents 89.9% of the colour distribution in the transfer printed wares. A further refinement of this idea for dating is that the earlier pottery was predominantly dark blue (Pilling nd:11). Reference to figures quoted in the discussion of blue floral transfer ware (above) shows that only 26.7% of that type was represented in the dark range of blues, and a similar figure is obtained for the total collection.

In the Fort Dundas and Raffles Bay collections, although the sample is considerably smaller, the darker blues do predominate, and no other colours are present in the transfer printed wares from those sites. Therefore, the introduction of lighter blues may offer a tentative date marker of the second quarter of the nineteenth century.

The non-blue colours in the present collection also support the historical dates suggested for their introduction. Multicolour printing is totally absent, except for the single sherd decorated internally and externally in different colours (Item 31).

Amongst the other wares, several types appear to be of short duration and therefore of good dating value. Pilling (nd:39) suggests that spatterware (also called sponged ware by Godden) although made before 1800 was most common in the period 1825-1840. Godden (1963:147) says, however, that this form of decoration continued into the twentieth century. Flowing blue ware, although only represented by a single sherd in this collection, is dated by Pilling (nd:36) to 1825–1860. The featheredge ware, although not as yet a closely dated type is a common utilitarian ware found at Port Essington, Raffles Bay and Port Dundas in both blue and green. It is also common in a number of American sites of the mid-nineteenth century (e.g. Pierson 1962).

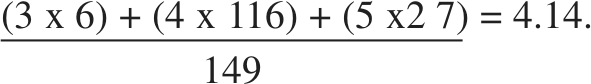

On the basis of the discussion above it is possible to construct a time range graph for the closely dated attributes associated with this pottery collection. From this graph (Figure 79) it is possible to arrive at an archaeological date which closely approximates the actual date of the settlement at Port Essington. This suggests that the dating of sites without extant historical records can follow this approach with some confidence. While it is difficult to estimate the time lag for pottery to reach Port Essington this does not appear very great and is probably only of the order of several years, which is what one might expect from historical knowledge of the transportation methods of the period. Almost all of the pottery appears to fit into a manufacturing time range 1830–1845, and possibly a shorter period still.

The English wares appear to be a typical collection of utilitarian wares of the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Few, if any, appear to have been made outside the Staffordshire potteries area. 76

Figure 79. Time range graph for dated items in collection (see text for discussion). Shaded area represents the time period the settlement was occupied.

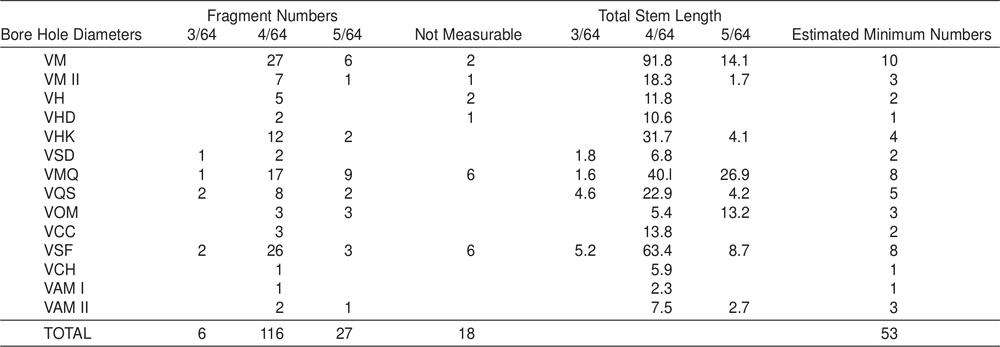

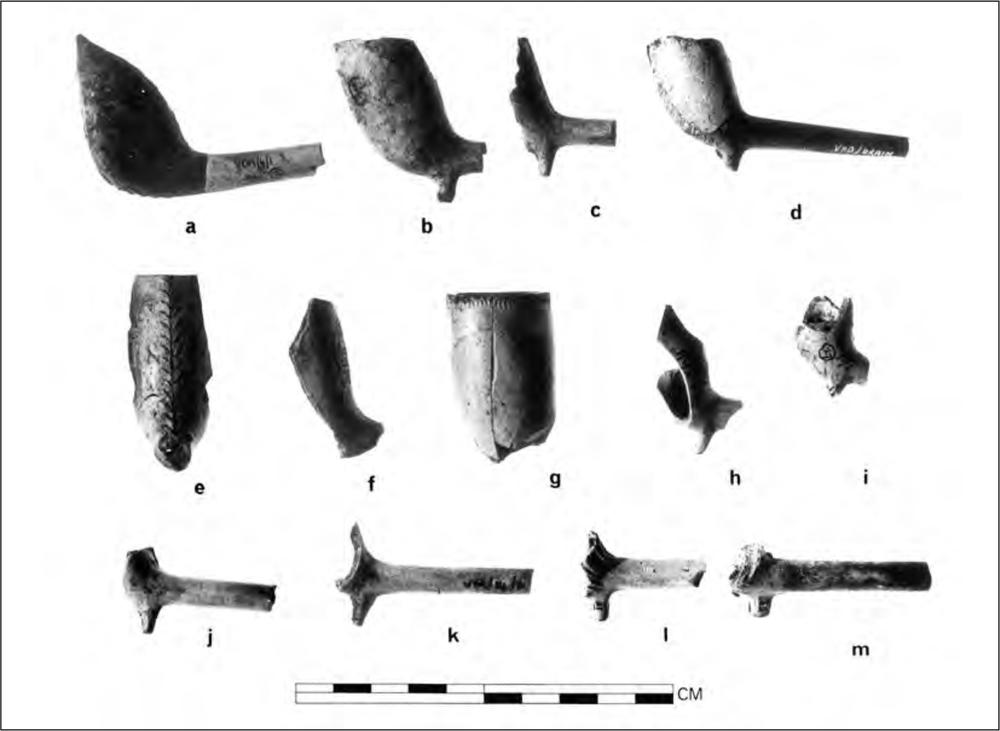

Clay Pipes