Chapter 5

Metal, Stone and Bone

METAL

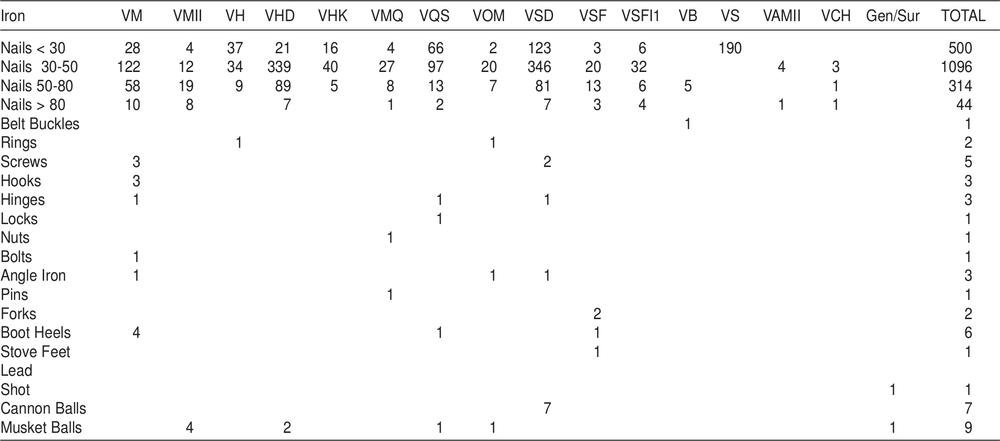

A wide range of metal artefacts was recovered from the excavations and these are presented in Tables 91, 92 and 93, according to the nature of the metal. In addition to these tables, a large quantity of unidentified iron, mainly hoop-iron, and unidentified scrap lead and copper, was recovered. These have been presented in the individual reports by weight and are not discussed further here.

Iron and lead

Apart from the hoop-iron, nails are the most predominant iron artefacts in the deposit. In general they are badly decayed and fragile and the exact measurements of all but a few items were impossible. Instead, they have been grouped into ranges. For example, as Table 91 indicates, of the 1,954 iron nails in the collection, 81.7% are less than 50 mm (2 inches) in length. The application of machinery to nail manufacture was first made in the United States at the end of the eighteenth century, and 120 American patents were taken out on machines that cut nails between 1790 and 1825 (Fontana and Greenleaf 1962:45; Fontana 1965). In contrast, machine made nails in England appear not to have been made until their production was begun in Birmingham in 1811 (Martineau 1866:613).

Table 91. Distribution by number of all identified iron and lead artefacts for the whole site. Nail measurements in mm.

Fontana and Greenleaf present a number of useful criteria based on technological improvements in the industry which help to date the nails in question. All the nails from the Port Essington collection are cut nails, and may be most easily recognised by the manner in which two sides of the shank run parallel while the two opposite sides taper away from the head. In the early American and English machines this taper was achieved by turning the nail plate upside down at each stroke so as to continue the taper by reversing the cut. This produced nails with a particular cross-section (Fontana and Greenleaf 1962:fig. 11q). Between 1810 and 1825 machinery was developed which obviated the need to reverse the plate and which produced a nail with a different cross-section (Fontana and Greenleaf 1962:fig. 11r). Martineau (1866:614) however, still describes this turning operation in use at about the mid-1850s in England, so that this dating criterion may not be effective in Australia (where imported English nails as well as locally made nails were used), at least in time equatable to the American situation. Because of the eroded nature of the nails in the present collection, it is impossible to record the cross-sections of many nails.

Figure 96. Nails from Port Essington: a-d) iron cut nails with square crowned heads; e) iron tufting nail; f) copper rivet; g-h) square shanked countersunk copper nails.

Although a large number of nail shapes and sizes were in existence in the nineteenth century, the nails from Port Essington are almost all ‘common cut nails with a square crowned head’ (Figure 96-a-d), similar to the fencing nails illustrated in an 1876 catalogue published by Fontana (1965:92). The major exceptions are nails less than 30 mm in length excavated in large numbers from VS, which have large 98mushroom heads (Figure 96-e) and are called tufting nails in the 1876 catalogue (Fontana 1965:92). At least some nails were manufactured at Port Essington (Anon.1843a:29, see McArthur to Bremer, 3.11.1841).

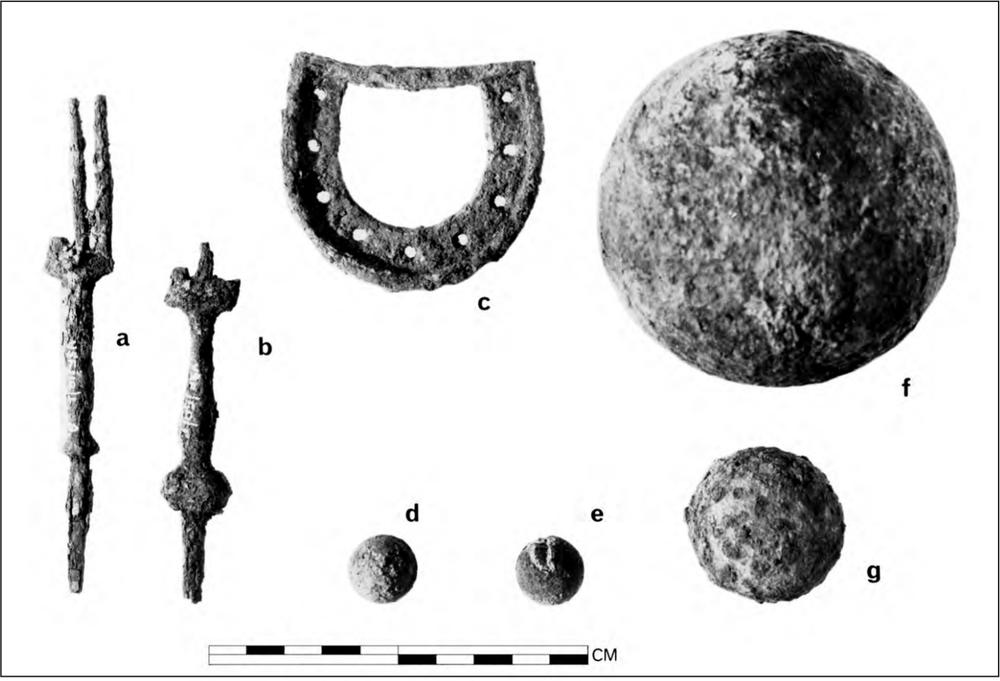

Figure 97. Iron and lead artefacts from Port Essington: a-b) three-tined forks from VSF I; c) boot heel from VM/12/1; d-e) musket balls from VM II/1/1; cannon ball from the collection of J. Calaby, Canberra; g) canister shot from VSD.

A number of the other iron artefacts from the collection fall into a general architectural category. Iron screws appear not to have been in general use in the settlement and those in the collection probably were used in furniture. Two iron forks were excavated in the shell floor of VSFI (Figure 97-a-b). Each of these forks has three prongs, an iron shank, and a tang which was probably set into a bone handle. A similar piece of cutlery from Raffles Bay still has the bone handle intact. It resides in the collection of the Historical Society of the Northern Territory.

A number of iron boot heels were also recovered (Figure 97-c). Seven pieces of canister shot were recovered from the floor of VSD where they had presumably been stored. All are of a similar size (Figure 97-g) and give an average weight of 217 gm, that is, they are almost exactly half-pounders. In addition two larger cannon balls were collected in 1965 by John Calaby, C.S.I.R.O. Division of Wildlife Research. Mr Calaby generously given the objects to be included in the present collection. These items weigh 2,583 gm (5.69 lb) (Figure 97-f) and 2,375 gm (5.24 lb) respectively and were interpreted as being originally six-pounders.

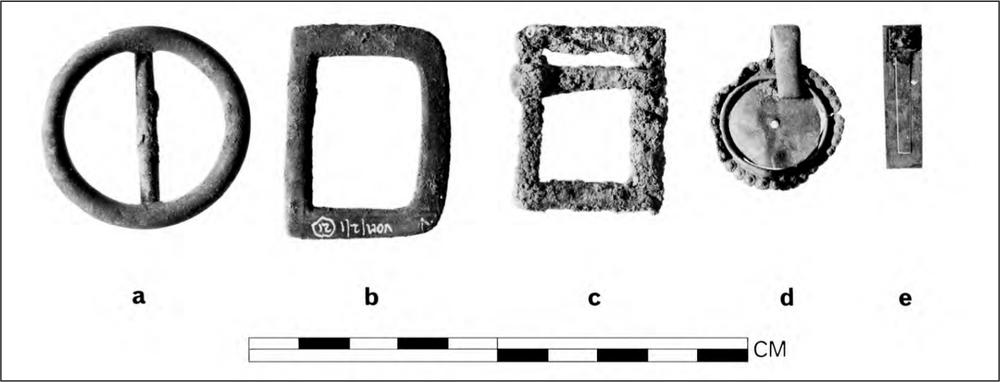

Of the lead recovered at Port Essington, the only recognisable objects were nine musket balls, which weigh 30.6 gms each (Figure 97-d-e). One four hole iron button was recovered. Its diameter is 19 mm. An iron belt buckle (Figure 102-c) was also recovered near the bakery.

Table 92. Distribution by number of all identified copper artefacts for the whole site. Nail measurements in mm.

Copper

Apart from pieces of scrap copper, the only artefacts of this metal are three coins, two items of uniform insignia and nails that are, as one might expect, less frequent than iron nails (Table 92). Again these have been placed in size ranges. The main type is the square-shanked cut nail with large counter-sunk flat head which is found in a number of sizes (Figure 96-g-i). The second type is a form of copper rivet with small flattened head and square blunt shank with diamond-shaped washer (Figure 96-f). Most of these nails were collected behind the beach, and presumably come from a broken-up boat. However the 40 copper nails less than 30 mm in length from the hospital kitchen are of this variety. Their use in the construction of this building is obscure, unless they were used to attach the shingles in the absence of shingle clouts. This seems a laborious method of attaching shingles, but no other explanation of these rivets presents itself. Two small copper ‘scales’ (Figure 100-a-b) each with three holes in the ‘top’ straight edge of the ‘scale’ were recovered and seem almost certain to be scales from either an epaulette or a shako chin-strap. The two examples here are of different size, the smaller measuring 20 mm along the straight edge; the larger, 30 mm.

Copper coins

Three almost identical coins of Southeast Asian origin were recovered. These were identified for me by Dr N. Barnard, Department of Far Eastern History, A.N.U., as ‘supikas’. According to Dr Barnard they are probably counterfeit coins of which many similar examples flooded into entrepôts such as Singapore during the nineteenth century (Schjöth 1929: plate 89). Schjöth has illustrated similar coins, from which it is possible to make identifications as follows:

V/Gen. Sur/Town square (37) (Figure 98-a)

Obverse: Schjöth No 1464, Plate 89

Reverse: Schjöth No 1480, Plate 89

VCH/2 (40) (Figure 98-b)

Obverse: Schjöth No 1463, Plate 89

Reverse: Schjöth No 1484, Plate 89

VHK/2/1 (63) (Figure 98-c)

Obverse: Schjöth No 1489, Plate 90

Reverse: Schjöth No 1501, Plate 90 99

Figure 98. Supikas, coins of Southeast Asian origin, showing obverse and reverse: a) V/Gen. Sur./ Town Square (37); b) VCH/2 (40); c) VHK/2/1 (63).

The first two coins relate to the reign of Ch’ien lung (1736–1795), and the third to the reign of Chia-ch’ing (1796–1820). The various obverse designs relate to provincial mints. Schjöth No 1480 refers to Yünnan province; No 1484 to Szechuan province; No 1501 to the Chihli mint.

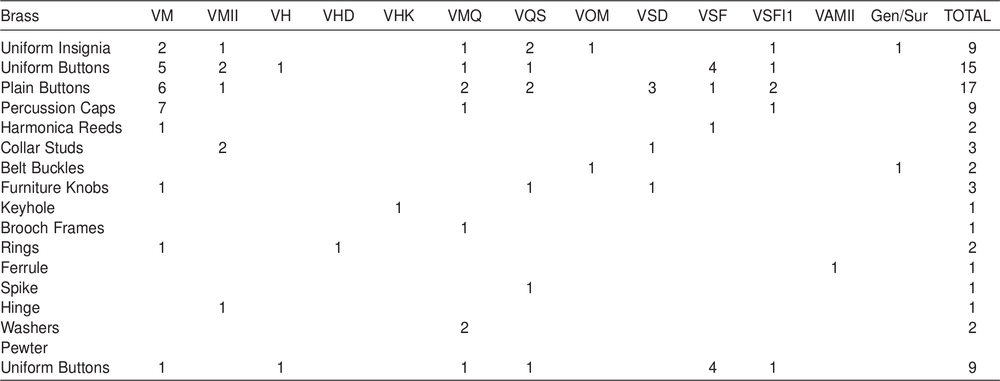

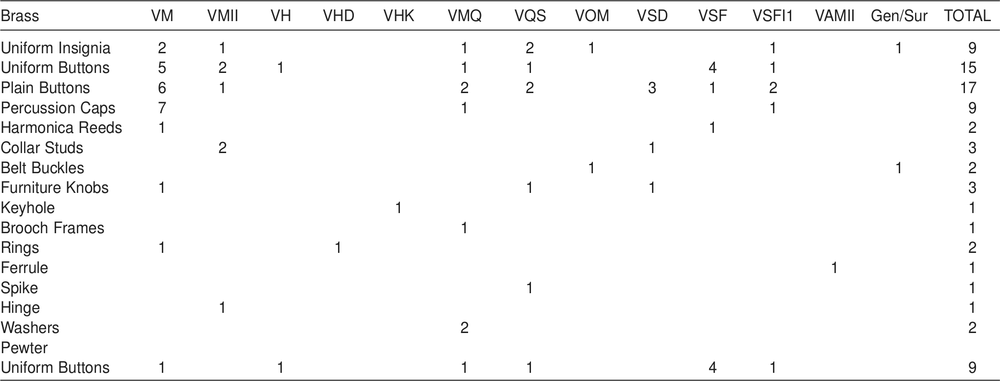

Brass

A number of different brass artefacts (Table 93) were recovered from the excavations which can be grouped as follows.

Figure 99. Royal Marines officer’s shako plate

from officers’ mess excavations.

Uniform Insignia

From the floor of the Officers’ Mess four pieces of a Royal Marines shako plate (Figure 99) were recovered during the excavations. This consists of an irregular shaped shield of radiating lines, topped by a crown and bearing in the centre an anchor. Above the anchor is the legend ‘GIBRALTER’ and below, the motto of the Royal Marines ‘PER MARE [PER TERRAM]’. The last fragment was not recovered. From the excavations in VQS, a medallion bearing the ‘Royal Crest’ (crowned lion standing astride a crown) was recovered (Figure 100-d). This measured 45 mm in diameter, and has been identified as a shako chinstrap terminal, although it is similar to a harness ornament in the collection of Professor A.C. Thomas of the University of Leicester (pers. comm. 11.11.1966). Professor Thomas’ example comes from the Military Train in the Crimea (1859-1865). My identification is based on an example examined in the Royal Marines Barracks Museum, Portsmouth.

• Two brass wreaths (Figure 100-e-f) were recovered, one each from VMQ and VQS. Each has two eye hooks on the back. They are part of the insignia worn by other ranks of the Royal Marines on the glengarry, the ‘pork-pie’ or ‘pill-box’ cap. Complete, these wreaths enclosed a small brass half-hemisphere of the globe, separated from the wreath, and with a separate bugle above.

• A free-standing crown and anchor (Figure 100-c) was excavated from VM/9/1, measuring 62 mm in length. One fluke of the anchor was missing, but this was recovered from the adjoining square, VM/10/1. There appears no way of indicating whether this was a marine or naval insignia. (But see uniform buttons below).

All these insignia would originally have been gilded.

Table 93. Distribution by number of all identified brass and pewter artefacts for the whole site.

100

Figure 100. Uniform insignia from Port Essington: a-b) copper ‘scales’ from epaulettes or shako chin straps (VM, VSF I); c) crown and anchor naval insignia (VM); d) royal crest shako chin strap terminal (VQS); e-f) other ranks Marine cap insignia (VMQ, VQS).

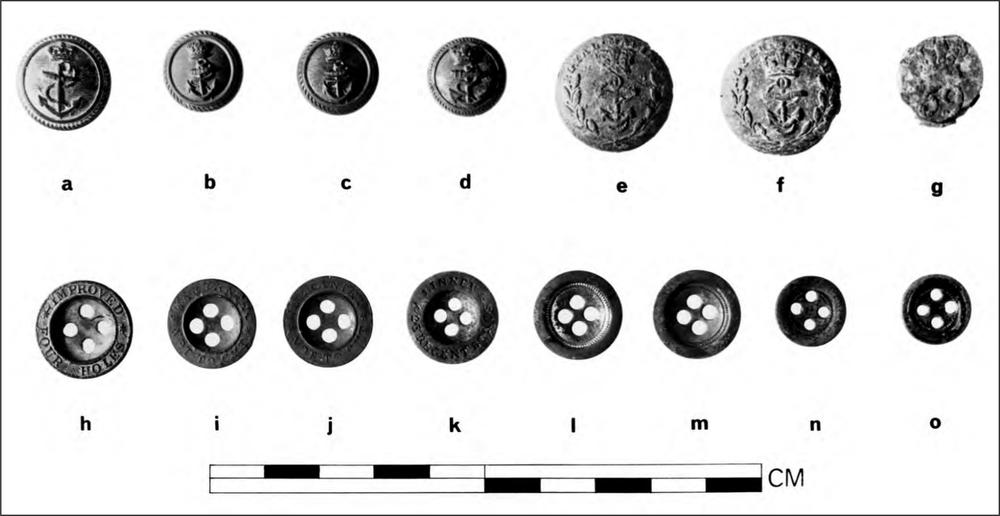

Uniform Buttons

An extensive typology of naval buttons has been set up by Michael Lewis (1945) where he lists a number of datable innovations in the evolution of these buttons. Four brass buttons were excavated, all from VM (Figure 101-a-d). All are identical in design. Each consists of a raised anchor and cable, with crown above, against a lined background; the whole surrounded by a raised circle, with the outer rim decorated with large indentations, which is the precursor of the true ‘rope-rim’ which appears on naval buttons at the end of the nineteenth century. In shape, these buttons have a flat base and a convex face. They are made in two pieces, with a single eye hook. Of the present examples, one has a diameter of 17 mm, the others diameters of 15 mm. Gilt is still present on the larger example, and it may be assumed that all were gilt buttons.

Figure 101. Buttons from Port Essington: a-d) brass naval buttons (VM); e-f) Royal Marines pewter buttons (VSF I); g) other ranks pewter button of the 59th Foot (2nd Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment) (VSF I); h-o) four hole brass buttons from various site-units.

All four buttons are inscribed on the reverse side. The large example (VM/8/1 (43)) (Figure 101-a) is stamped ‘TREBLE GILT STANDARD’; two of the smaller buttons (VM/14/1 (39) and VM/10/1 (56)) (Figure 101-b-c) are identical and are stamped ‘EXTRA STANDARD’; and the third small example (Figure 101-d) is stamped ‘& S FIRM’, i.e. Firmin and Son(s), button makers.

Referring to Lewis’ classification the buttons are almost identical to that author’s type D.2 (Lewis 1945:plate 3), which came into use in 1827 and was worn by commissioned officers, master’s mates, and midshipmen. The slight difference which occurs is that on the present buttons the cable ring lies to the right of the shank instead of on the shank as in Lewis’s example. However, on Lewis’s type D.1 the ring lies to the right, although this button has the addition of a laurel wreath and was worn only by flag-officers.

On the Firmin button, and VM/8/1 (43) the anchor stock slopes down on the right. On the other two examples it is horizontal.

It is reasonable to identify these buttons as naval rather than marine in origin, and may well have come from a discarded garment which also may have been the source of the free-standing crown and anchor described above. According to Parkyn (1956:4) the precise designation ‘FIRMIN & SONS’ was used only in the period 1824-1826. However, specimens in Professor Thomas’s collection make it reasonably certain that this designation can occur up until about 1850.

At this point it is expedient to include uniform buttons made of pewter (Figure 101-e-g). Altogether nine of these buttons were recovered, four from VSF I, and one each from VM, VH, VMQ, VQS and VSFII. All are convex shaped with a single iron eye hook set in the back. Eight are identical in design, bearing a raised crown and anchor, surrounded by a laurel wreath, with the legend ‘ROYAL MARINES’ above. Each of these carry the maker’s name on the reverse. Seven are inscribed ‘NUTTING LONDON’, the eighth ‘M GOWAN LONDON’. The ninth button in this group has a crown above ‘59’ and has been identified as the other ranks button of the 59th Foot (2nd Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment) of the type worn between 1840 and 1859. No maker’s name is discernible. The marine buttons are a normal early pattern of other ranks coatee button. Professor Thomas states that these pewter buttons went out of use in 1855, and that an example of a similar button in his collection is dated to 1830. Little is known of the makers recorded here, although Nutting is an early nineteenth century manufacturer. The Royal Marines contracted for the manufacture of their buttons to a number of firms, so that no very close date can be obtained from this 101source of information. However taking into account the buttons and insignia, Professor Thomas (pers. comm.) was able to conclude, without knowing the date of the settlement: ‘I would guess that none of these items are earlier than c. 1830 and probably refer to military occupation between 1830 and 1860. If one had to pin it down, the earlier half of this period might be preferred.’

Figure 102. Brass and iron artefacts from Port Essington: a-b) brass belt buckles (VOM and general surface collection); c) iron belt buckle, surface collection near VB; brass brooch or cameo holder from VMQ; e) harmonica or accordion reed (VSF I).

Fourteen plain brass buttons were recovered from the excavations (Figure 101-h-o). Nine have a diameter of 16 mm, the others a diameter of 13 mm. The smaller ones are only slightly concave, with four holes, and bear traces of black enamel. None of these are inscribed. Of the larger ones, all have four holes, and have flat rims with concave centres. Four are unmarked and bear traces of gilt. Of the others, three are identical and are inscribed on the front ‘GUARANTEED NOT TO CUT’. These examples also have traces of gilt. Another is inscribed ‘IMPROVED FOUR HOLES’. The final example is inscribed ‘A. LINNEY & SON. 23 REGENT ST’. All the buttons in this group can be regarded as shirt, coat, or fly buttons typical of the period.

Other brass items recovered from the excavations include nine percussion caps, several belt buckles (Figure 102-a-b) two harmonica reeds (Figure 102-e) and a brooch frame from VMQ (Figure 102-d), together with other items listed in Table V-3.

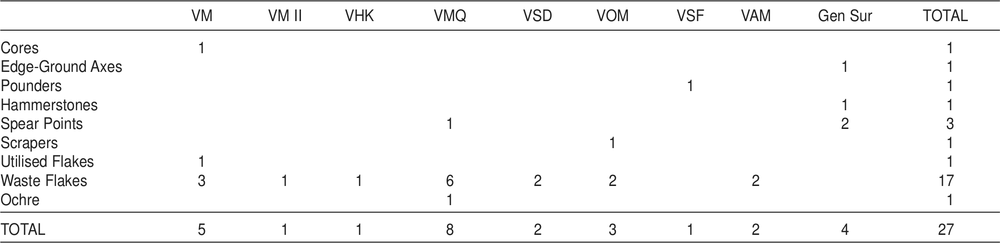

Table 94. Distribution of Aboriginal stone artefacts for whole site.

The metal collection as a whole reflects a number of aspects of life at Port Essington. The military nature of the settlement is reflected not only in the uniform insignia and buttons, but also in the various sorts of ammunition. Further aspects of the architecture have also been recorded in the nails recovered, and the finds in all cases support archaeologically the historical identifications of the various structures. For example the one feminine artefact, the brooch holder, was excavated from the floor of one of the married quarters; the officers’ shako plate came from the floor of the officers’ mess; the four other ranks’ coatee buttons were recovered from the floor of one of the single men’s houses. Nothing in the collection suggests a date other than that which is known historically. Apart from Professor Thomas’ extremely accurate assessment of the date of the buttons and insignia, the presence of the percussion caps (discussed below in relation to gunflints), machine cut nails and harmonica reeds all point to a mid-nineteenth century date for the settlement. The mouth organ or harmonica was invented in Berlin in 1821 by Friedrich Buschmann, who also invented the accordion in the following year. The reeds in this collection may come from either instrument (Sachs 1940:406).

STONE

Aboriginal stone artefacts

Twenty seven pieces of stone which could be associated with the Aboriginal occupation of the area were recovered from the excavations and surface collections. The artefacts are of a number of materials; creamy quartzite, hornblende gneiss, chert, porphrytic dolerite and slate, none of which stone types occur naturally in the Port Essington region. Table 94 gives the distribution of artefacts.

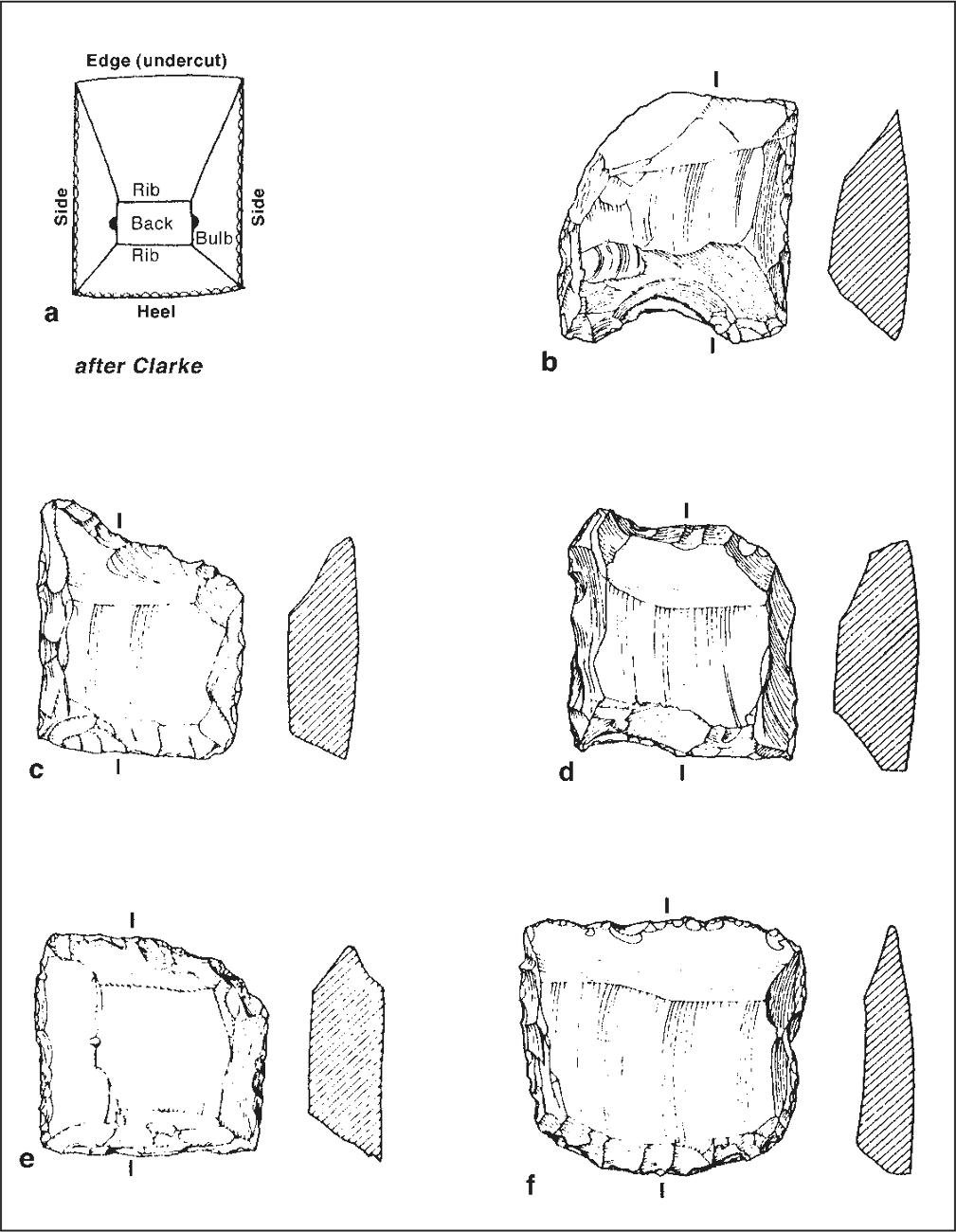

The single core in the collection (VM/S/1 (55)) is of creamy quartz and appears to have been a leilira blade which had previously been broken. From this piece indiscriminate flakes had been detached. One flake, possibly from this core, was recovered (VM/8/1 (143)) and bears snap-break usewear along the thin edge. It is reminiscent of the glass cutting flakes described in Chapter 4. The hammerstone (Figure 103-c) is a small water worn pebble with pecking on one end. The pounder (Figure 103-a) conforms in shape to the conical pounder of McCarthy’s et al. (1946:68) classification, although it is a small example standing only 77 mm high. Stratigraphically it is earlier than the house site VSF I, under which it was found. The scraper is of black chert with heavy step flaking along one edge that is concave in shape.

Amongst the implements the three spear points (Figure 103-d-f) appear to be of some interest in that they have no parallels in the literature. Five fragments of one were excavated in the area immediately outside VMQ where 102evidence of glass flaking was also recorded. When reconstructed the implement was a heavily step-flaked square butt of what was probably a spear point (Figure 103-f). The step-flaking is bifacial and continues around the entire perimeter. A second flaked piece of slate (Figure 103-e) was collected from a sandbank behind the mudflat to the west of the settlement (VWM), where it was found in association with a midden scatter containing shell and some glass artefacts. The third example (Figure 103-d) was collected from the beach to the south of the settlement by the ranger’s Aboriginal assistant, Sam. When Sam handed me the implement I asked him what it was, and he replied that it was a shovel-nosed spear. I commented that such spears were made only of metal but Sam shook his head and said that this was a shovel-nosed spear of ‘the old people’. If this identification is correct these implements represent a type not previously recorded. The source of the slate is unknown but an anonymous observer in the 1840s noted that slate implements were being traded in from the interior (Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle 1842:88). From extensive excavations in the settlement no suggestion of slate for roofing has been uncovered and writing slates can be discounted by the thickness of these implements.

Figure 103. Aboriginal artefacts from Port Essington: a) VSF I/10; b) VMQ/10/2; c) VMW surface collection; d) south beach surface collection; e) VMW surface collection; f) VMQ.

Also from VMQ, a piece of ground ochre was recovered. This piece has striations across the surface and the edges are ground (Figure 103-b).

The general lack of stone implements conforms to the wide range of ethnographic and archaeological evidence for the non-use of stone artefacts by people living on the Arnhem Land coast. White (1967) used this as evidence for the principal theme of her doctoral thesis, the dichotomy of the ‘plateau’ and ‘plain’ peoples in the Oenpelli region. While essentially true, during my fieldwork I located an axe quarry site at Reef Point on the eastern shore of Port Essington. This suggests that the use of stone by the coastal people depended on the availability of the material in the immediate environment. However the people living in the Victoria area of Port Essington do not appear to have used stone artefacts except those traded or carried into the area.

European stone

The six stone artefacts of European origin recovered from the site are five gunflints and a fragment of slate pencil. The latter artefact was excavated from outside the confines of VSD and is 36 mm in length.

The gunflints were distributed across VM, VH and VMQ, with the last two items surface collected along the cliff line near the married quarters. Four of the items are bluish-grey to almost black in colour and possibly are Brandon flints. The fifth example is honeycomb in colour and translucent.

The manufacture of English gunflints has been adequately described by Rainbird Clarke (1935) and Knowles and Barnes (1937). Figure 104-a shows the standard shape and gives the nomenclature used for gunflints. The bulb, called more correctly demi-cone of percussion by Knowles and Barnes makes the identification of flints simple, even on extremely worn pieces, or pieces which may have been re-used by Aborigines.

The gun flints from Port Essington fall into two groups. The four flints of similar material (Figure 104-b-e) are approximately the same size, ranging in heel width between 25 mm and 28 mm, approximately an inch in the imperial measure. In size they are comparable to Clarke’s musket size gunflint (1935:55 and fig. 2. See also Peterson 1956:229-50). The edge on each example is extremely worn and one example appears to have been re-flaked to form a concave scraper.

Figure 104. Gunflints from Port Essington: a) illustration by Clarke (1935) showing typical characteristics; b) VM/14/1; c) VMQ/32/1; d) VH/2/1; e-f) V/Gen. Sur./ VCC.

The fifth example (Figure 104-f), in honeycomb flint, differs in both size and manufacture as well as material. It is larger than the other examples, measuring 33 mm across the heel. The rib flake scar is wider and the heel is less square than the other examples. It Is also thinner than the other examples. 103The heel and sides of this example has been flaked completely so that the two diagonal ridges running from the heel to the rib flake scar are no longer definite. Both Clarke (1935:51) and Knowles and Barnes (1937:207) refer to French gunflints of this period having ‘gnawed heels’ so that this item may be of French origin.

The presence of both gunflints and percussion caps in a military settlement provides yet another avenue for dating the settlement by archaeological means. Clarke dates the introduction of percussion caps to 1832 and notes that the sale of the last consignment of gunflints to the British Government took place in 1838. It might be expected that the changeover took place rapidly, so that the presence of both types of firearm at Port Essington offers a time range which does in fact coincide quite closely with the known historical dates.

BONE

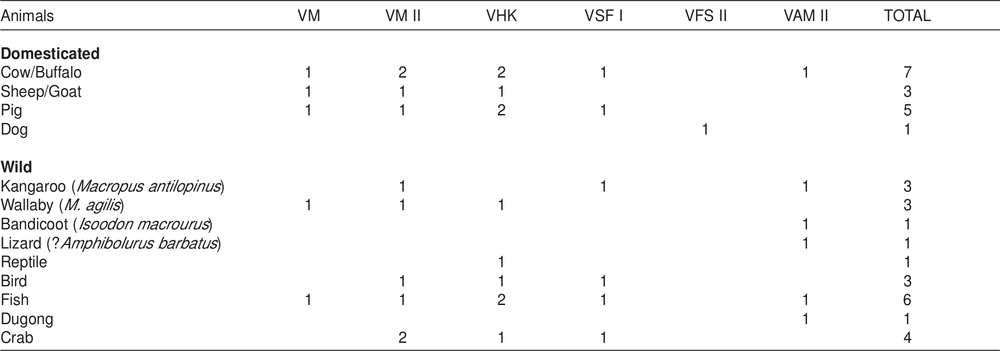

Table 95 gives the distribution of minimum numbers of identifiable animals from the bones excavated about the settlement.

Table 95. Distribution of bone for the whole site: minimum number per site-unit.

In general bone was not plentiful in the excavations and only two points of interest emerged from the analysis. Firstly the distribution of bone remains does to some extent reflect the functions of the structures excavated. The only habitation site-unit from which bones were recovered in numbers was VSF I, the shell floor of one of the enlisted men’s huts. The bones from the hospital kitchen were excavated outside the building in what was essentially a dump area, and the other two concentrations of bone came from rubbish dumps.

Secondly, the archaeology confirms the documentary record (see Chapter 8) of the sorts of animals being exploited for food by the garrison; it illustrates that hunting the native animals, birds and fish was perhaps not as important for supplementing the diet, as was the importation of domestic animals for food from outside the settlement.

Finally the evidence from the Aboriginal midden (VAM II) indicates that the Aborigines still caught and ate traditional food, and with the exception of the one cow/buffalo represented in the collection, they appear not to have eaten meat from animals imported for the European garrison. However this evidence is at best inconclusive. 104