Chapter 8

Life at Port Essington

Archaeologists have established that the Aborigines had occupied the immediate area of the Cobourg Peninsula upwards of 24,000 years before the British first tried to settle there (White 1967). During that time they had come to terms with their environment, modifying it to some degree by the use of fire, but probably not altering the face of the country as much as hunters and gatherers in more temperate climates may have (Jones forthcoming [1971]). The region appears to have provided plentifully for the subsistence needs of its human occupants, who in turn bowed gracefully to the will of the seasons, perhaps moving with the wet and the dry seasons to places best able to support their semi-sedentary existence. Then perhaps for the last thousand years on the basis of new radiocarbon dates (Macknight pers. comm.) the north coast became the scene of a new activity, the seasonal visits of the Macassans. These people were also in tune with nature, utilising the monsoons for travel, and the natural resources for profit.

The British however brought with them a mentality based on the lush meadows of England and the genteel society of London, and with an arrogance backed by an empire which spanned the world, met the problems of planting the flag in north Australia head on. The pomp and circumstance of the parade ground might have little application in Port Essington but since it was considered necessary for discipline, the marines paraded while the white ants unceremoniously attacked the sofa in Sir Gordon Bremer’s tent, although he caused it to be moved every day (HDL In Letters B.798: Bremer to Beaufort 7.12.1838).

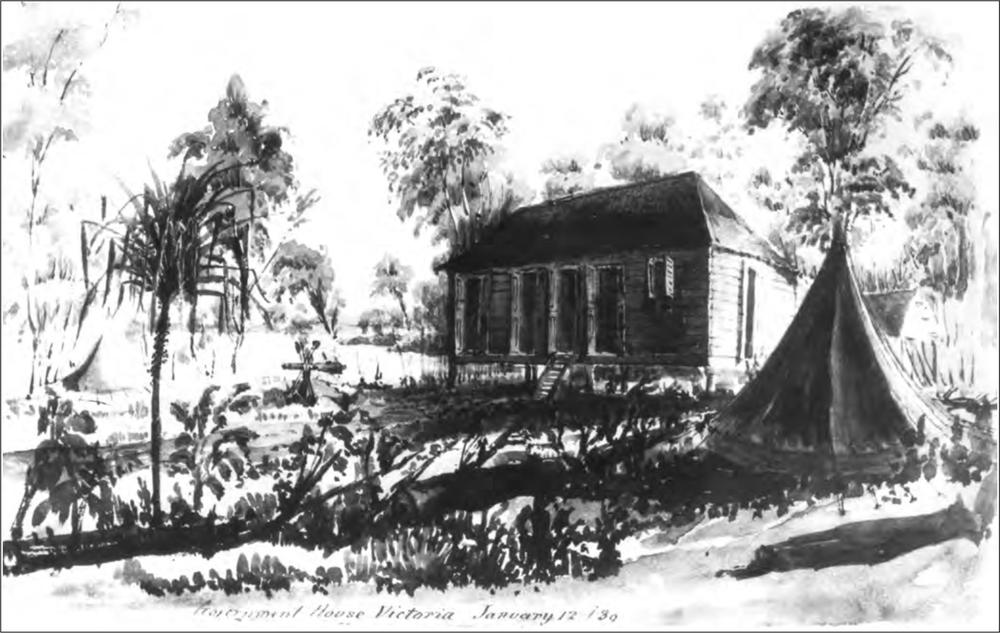

Figure 105. The prefabricated Government House, shortly after it was erected. Watercolour by Owen Stanley, entitled Government House Victoria January 12 /39. Mitchell Library GPO 1 25200. Published with permission of the Mitchell Library.

The first garrison 1838–1844: getting started

Forty marines disembarked to form the garrison, a captain, a lieutenant, and 38 enlisted men (RMAP Port Essington personnel list). While Earl reported that the men had little interest in the success of the venture, their own despondency at such a posting can be imagined. They were a motley group whose trades ill-fitted the challenges they were to face. They comprised 18 labourers, four carpenters, two wheelwrights, two shoemakers, a carter, a gardener, a clerk, a blacksmith, a whitesmith, a tailor, a brass-founder, a stonemason, a cabinet-maker, a miner and a butcher. The fifer was listed as having no trade and may still have been a boy. The archaeology suggests that the five married quarters dated to the beginning of the settlement imply that five men brought their wives with them, although these are not listed, nor the number of children in the settlement.

With the Britomart, the Alligator and the Orontes in port, the ships’ crews were employed to assist the garrison and the beginnings of the settlement progressed at a favourable pace. Prefabricated buildings brought from Sydney were erected, including Government House (Figure 105). Bremer had been instructed to erect such defensive earthworks as might be necessary (Adm. 2/1965: Adam and Parker to Stanley 30.1.1838) and this appears to have been done, from the remains of a square area enclosed by a ditch and bank, on the high ground on Minto Head. This is shown as foundations for a blockhouse on the McArthur map (Figure 4) but it is uncertain whether there was ever a building here. If the 118purpose of this was to protect the settlement from Aboriginal hostility, such fears were short-lived. The intelligent handling of Aboriginal and British interactions by Collet Barker at Raffles Bay was reflected in the mostly amicable relations between the garrison and Aborigines throughout the lifetime of the settlement at Port Essington.

As well as the marine listed as a gardener, a civilian gardener had been employed for the settlement (Adm. 2/1965: Adam and Parker to Stanley 30.1.1838) and gardens were begun, land cleared and the erection of the prefabricated buildings was commenced. Bremer’s complaint that the timber of the country defied the saws and tools which they had brought (Anon. 1843a:9–10) was reminiscent of the beginnings of Port Jackson fifty years before, and indeed the tiny settlement must have emulated the first few months in Sydney as improvisation and invention were brought to bear on understanding and using what local resources were available. The successful early voyages of the Essington and Britomart heightened the general optimism and Bremer wrote of the beauty of the place in ecstatic terms (HDL In Letters B.798: Bremer to Beaufort 7.12.1838). He felt assured of the fertility of the soil for growing spices, pepper, cotton and rice; stated that the harbour might contain the whole navy in perfect security; and noted that the country was providing kangaroos, geese, ducks, curlews, snipe, partridges, quail and pigeons, as well as plentiful supplies of fish when time permitted the hauling of the seine (a fishing net). Permanent water was found several miles to the west (Earl 1846:37), and in May 1839, after completing the jetty, Lieutenant Stewart of the Alligator spent seven days exploring the Cobourg Peninsula. He reported an abundance of water on the peninsula, with fine fertile land on the southern side, and good building timber (RGSA Stewart journal). He encountered the buffaloes which had already strayed below the neck of the peninsula after having been released from Raffles Bay and which formed the nucleus of the large herds at present in this part of the Northern Territory.

Figure 106. The French vessels Astrolabe and Zelée at anchor in Port Essington, April 1839. Lithograph by L. Le Breton. In d’Urville (1841-55: Atlas Pittoresque, plate 118).

The arrival of the French

At the beginning of April the Aborigines reported a European vessel in Raffles Bay, and soon after the arrival of five Macassar praus confirmed the information. Stewart was dispatched to investigate and found the Astrolabe and the Zelée commanded by Dumont d’Urville, at anchor, with the ‘French tricolour flying over two or three tents upon the shore’ (Earl 1846:56). Bremer expressed his ‘great mortification’ (HDL In Letters B.803: Bremer to Beaufort 5.4.1839) but sent Stewart to invite the French to visit them before they left the coast. On 6 April the French vessels anchored in Port Essington where they remained for three days (Figure 106). The visit was extremely cordial and d’Urville related that they were invited to dine on shore and supplemented the meagre British fare with, amongst other things, wines from the Bordeaux region of France (d’Urville 1841–55 (VI):280 n.19). The conviviality of that dinner was made strikingly real during excavations, by the recovery of the seals of bottles of Château Margaux and Château Ychem from the rubbish area behind Government House, together with the seal of a bottle of vintage French brandy which has been attributed to the same source.

Progress

During the first six months of the settlement considerable progress was made and the optimism of Bremer’s despatches was not unfounded. By April he was able to report the completion of the pier, the hospital and the officers’ quarters together with progress on the batteries and a victualling storehouse, in addition to ‘24 cottages and gardens, all comfortable’ (Anon. 1843a:11). In point of fact these cottages can hardly have been anything other than uncomfortable. The excavation of the floor mound VSF I, identified from its position and the evidence recovered, as a single men’s hut, indicates a 3 m by 3 m floor plan. This building and presumably all the single men’s quarters, was either completely bark covered, or had reed walls with a thatched roof (HRA 1 xxvi:373–4). McArthur records that these huts lasted two to three years, by which time the framework would be completely destroyed by white ants, and the evidence from the excavation of VSFII (a similar hut) suggests they were probably burnt to kill the termites and new ones rebuilt on the same sites. Red clay appears to have been first employed for flooring, but possibly after the first wet season fine beach shell was used and the stratigraphy of these mounds reflects the successive layers of this flooring which became traditional in many parts of the settlement. During the wet seasons these huts were supplied with fire baskets for burning charcoal (ML A.501–3: Brierly journal entry 14.11.1848) and in the case of VSFI, this basket apparently stood on the floor stones located archaeologically in the centre of that structure. In 1848, Brierly noted ten such huts for the use of the men which 119suggests that each hut must have housed, conservatively, at least three men. Sweatman, in his journal (ML A.1725 II:256) lists the number as four.

The married quarters were of similar materials with the addition of a stone fireplace at the southern end. From Brierly’s description (ML A.501–3: Brierly journal entry 14.11.1848) these houses were constructed of rushes attached to a light wooden frame by bamboo strips on the outside; ‘they had little square holes for light and air, with little raised shutters like the ports of a vessel’. Today only the chimneys remain as a testimonial to the ingenuity of the Cornish marine who must have volunteered his knowledge in the absence of any more accomplished builder. His own work was not accomplished, as the detailed analysis of these structures has demonstrated, but he unwittingly left evidence of the improvisation which took place at Port Essington. He may also have been among the marines picked up in South Australia by the Alligator. James Wallace was aboard that ship and kept a diary (NLA MS.179) that contains a watercolour that shows a similar round chimney in South Australia. Of interest, the Australian examples provide the best dating for this type of chimney in western Cornwall, where some 60 similar chimneys have been recorded by archaeologists (Anon. 1964:107).

Captain John McArthur, acting comandant and commandant 1839–1849

When Bremer left Port Essington in June 1839, Captain John McArthur was appointed Acting Commandant, a position he held until 1844 when he was made Commandant (AONSW 4783 Lambrick letter books In Letters no. 29: Admiralty to McArthur). McArthur was a nephew of John Macarthur of Camden, being the ninth child and third son of James and Catherine (Burke 1891–5 I:227). Born 16 March 1791, McArthur joined the Royal Marines in 1809 and appears to have had an undistinguished career before his arrival at Port Essington, attaining the rank of captain in 1837 at the age of 46, although he eventually became a major general in 1857, the year in which he appears to have retired, since he is omitted from the New Annual Army List from1858 onwards. (Here I have adopted the spelling McArthur used on his despatches rather than that of his more famous uncle.)

No journal and few personal letters are extant which might give information as to McArthur’s personality. Brierly described him as a tall thin old man (ML A.501–3: Brierly journal entry 14.11.1848). Leichhardt said that he was proud to count McArthur as one of his friends: ‘A man of so various knowledge and of so sound information is rare anywhere, but uniting it with such an amiable disposition, such willingness of communication, and if I could use the term, of conversational bartering (ready to give and to take) becomes a rara avis than most’. Added to this he was a good and careful observer of nature (ML C155: Leichhardt Journal 1845:440).

McArthur’s skill as a watercolour artist can be judged from the frontispiece to this volume. Slightly right of centre, the distant building with the bell-tower can be identified as the church and the more distant building to the left is Government house. The contemporary map of the settlement (Figure 4) confirms these identifications. The church location is merely marked on this 1847 map with dots because this church was destroyed in 1839 by a hurricane and never rebuilt (see below). This dates this painting to sometime during 1839.

According to the Melbourne Argus (16.5.1931) McArthur also possessed some musical ability and these skills reflect the cultural side of his character. Several of his personal letters indicate that he felt his destiny was guided by his Maker and in prayer he gained solace for the depression of his long banishment. More than Barker, he was guided by the Book of Regulations, and less than Barker did he possess the instinctual flair for seeing around problems in an environment that demanded improvisation. This led to conflict with a number of his men. Earl, who spoke warmly of McArthur on a number of occasions, observed nevertheless that the settlement was retarded by the fact that he was ‘disinclined to do anything of consequence out of the routine’ (RGSA Earl Correspondence: Earl to Washington 13.7.1840). One can appreciate the clash of personalities which caused the young, brilliant, but unhappy T.H. Huxley to write that ‘the respected Captain MacArthur is with all reverence one of the most pragmatical old fogeys I ever met with’, adding that ‘the commandant is very economical and unless some ship is there to divide the spoil he won’t have a cow killed because it is too much and a good deal spoils!! – so the oxen live and the men die’ (Huxley 1935:149). Elsewhere he observed that Port Essington was ‘about the most useless, miserable, ill-managed hole in Her Majesty’s dominions’ (Huxley 1935:fn 1). Thus for want of any greater vision McArthur ruled by strict authority. He put down those who sought temporal relief in gambling and rum. He opposed settling the men’s accounts at a pay-table, a procedure instituted by the acting pay- and quartermaster on his arrival in 1844, on the grounds that this was offering incentive and temptation to these ‘desperate and ungovernable vices’. ‘I need not observe’, he wrote, ‘that after the working hours the time must be spent in much listlessness, there are few external circumstances of excitement as in a camp, or a garrison with an enemy in front, which of itself demands and ever induces voluntary and free action – yet if these occupied men may be seen still strong in purpose to obtain liquor and will even find means to accomplish that purpose (I believe this is not overcharged) what shall we suppose may not be done in a position like this. Surely the reply is unnecessary – it is not the hours of occupation, but those of idleness which are difficult to regulate and I feel that every means which can be placed in my hands as preventives, will but barely suffice’ (RMAP: undated letter (1844) McArthur to Owen).

The tropical environment and the 1839 hurricane

But while McArthur might strive to control his men, all were controlled by the environment which they tried to tame. During 1840 the maximum temperatures ranged between 31.7° C and 36.1° C and the minimums between 17.2° C and 26.1° C (CO 201/313: McArthur to Admiralty 16.7.1840 in Barrow to Stephen 2.7.1841). From more complete records maintained on board the Alligator between October 1838 and May 1839 the lowest minimum temperature recorded was 25.0° C and the highest maximum temperature 35.0° C (PLV MS. H16559: Tyers’ Meteorological Record). In general it appears that the shore temperatures were usually hotter and that any breezes on the water were quickly dissipated by the tree cover on shore. No records of humidity are extant but for much of the year this would have been high. During this early period there was no major sickness in the garrison, and the various despatches reflect a general optimism on this point. ‘I am extremely glad’, wrote Earl, ‘to find that Europeans do not lose their energies here, as I scarcely dared to expect otherwise’ (RGSA Earl Correspondence: Earl to Washington 17.3.1840).

In June 1840, and again in May 1841, earth tremors were experienced in the settlement (CO 201/313 McArthur to Admiralty 16.7.1840 in Barrow to Stephen, 2.7.1841; C.O. 201/323: McArthur to Gipps, 3.11.1841 in Gipps to Stanley, 3.11.1842) but these did little damage and were inconsequential compared with the hurricane which had struck the settlement on 25 November 1839. The settlement had 120experienced unsettled weather on the previous day, and gradually as the evening progressed the winds increased and the rain fell until at 11 p.m. the full fury of the storm unleashed itself upon the frail settlement. With the daylight came calm, but the scenes of devastation which greeted the garrison must have awed even the staunch McArthur. Trees and gardens were completely uprooted. The hospital, officers’ mess and one store house had survived, but the improvised huts of the men were laid waste. Government house had been hurled from the piles on which it stood, the church destroyed (Figure 107), the jetty and storehouses on the beach washed away (Sydney Gazette 2.5.1840). The work of twelve months had been nullified in twelve hours.

Figure 107. Remains of the church following the 1839 hurricane. Watercolour by Owen Stanley, entitled Ruins of Church. Mitchell Library PXC 279 f.50. Published with permission of the Mitchell Library.

The Britomart and the Pelorus had been at anchor some distance east of the jetty. While the anchors of the former had held, the Pelorus was less fortunate. At 10 p.m. she began to ship heavy seas and an hour later she broke from her moorings. In desperation the crew fired distress guns and rockets, as they worked to keep the ship from running aground, but to no avail. At midnight she went aground on the eastern side of Minto Head where she was battered by the huge waves (Figure 108). When daylight came the Britomart sent a boat to help take off the crew, and it was found that eight men had drowned (Adm. 53/972: Pelorus’ log entry 25.11.1839). The ship was not re-floated until the following February (Figure 109) and was eventually sold out of the Service. It thus became the second shipping disaster at Port Essington, the Orontes having been wrecked on an uncharted reef at the harbour mouth in December 1838.

Figure 108. Wreck of the Pelorus during the 1839 hurricane. Watercolour by Owen Stanley, entitled Situation of H.M.S. Pelorus 1839. Mitchell Library PXC 279 f.55. Published with permission of the Mitchell Library.

Tropical predators

North Australia possessed no large terrestrial animals which the garrison might fear. Although several species of poisonous snakes inhabit the region there is no record of anyone from the settlement being bitten, and only one story of an encounter with a crocodile, which was shot after having carried off Sir Gordon Bremer’s favourite dog (HDL In Letters B.798: Bremer to Beaufort 7.12.1838). Nonetheless those creatures that did inhabit the region proved formidable opponents for the Europeans. Rats and other animals attacked the gardens and cockroaches and flies continuously spoiled stores and food. The ever-present sand flies and mosquitoes were sufficiently irritating to cause Bremer to mention them and the painful ulcers they induced in an official despatch (Anon. 1843a:9) and amongst the mosquito population, at least one of the approximately 30 species of the Anopheles genus that 121transmit the parasite Plasmodium that causes malaria, was present when a carrier came into the settlement. The green tree ants in their millions made clearing a slow and often painful business.

Figure 109. H.M.S. Pelorus was not re-floated for 3 months after the hurricane. Watercolour by Owen Stanley, entitled H.M.S Pelorus at low water. Mitchell Library PXC 279 f.56. Published with permission of the Mitchell Library.

It was, however, the white ants which provided the most concerted opposition to the British settling Port Essington, and even in the lifetime of the garrison they were victorious.

In 1848 Brierly observed that both the blockhouse and the storehouse (VQS) that Lieutenant Lambrick, the acting pay- and quartermaster, and his family had occupied on his arrival in 1844, were both so decrepit because of the depredations of the white ants that neither could be used any longer, and had been abandoned (ML A.501–3: Brierly journal entry 14.11.1848). McArthur had reported that the men’s huts had to be replaced every two to three years for the same reason; Bremer had noted early success against these predators by using coal-tar, but the lack of lasting success was reflected by Owen Stanley who in a report on the settlement in 1849 to the Colonial Secretary, recommended that should the Government decide to retain Port Essington, ‘iron frame-work should be sent out, as it has been found impossible to guard against the inroads of the white ants by any means that experience could suggest or ingenuity devise’ (HDL SL.15f: Stanley to Deas Thomson 17.4.1849).

This was not quite true, however. Accidentally the garrison had discovered a technique which aided the fight against the termites, and which, when rediscovered, was to become the most distinctive hallmark of tropical architecture in Australia – the use of piling. Including the church, seven prefabricated buildings were shipped to the settlement from Sydney and rather than excavate level areas it was found more convenient to set these buildings on piles.

The largest of these prefabricated buildings was Government House (HRA 1 xxvi:373) described by Earl (1846:88) as being 18 feet by 40 feet, with a roof of split shingles. The building usually referred to as the hospital was in fact the second hospital and was a much larger building, but it was not yet built. The first hospital was a prefabricated building which later became a store house (VSD). This, together with the ordinance store, was set on dwarf piles several feet from the ground, but the remaining prefabricated buildings were raised eight feet from the ground on wooden piles. Whether or not this was done deliberately to increase storage space is unclear, but its effectiveness for controlling the white ants soon became apparent. McArthur observed that ‘this temporary method of piling in order to raise the buildings has proved very useful. Had they been fixed on the ground in the usual manner they must have been destroyed long since by vermin’ (HRA 1 xxvi:373–4). The technique was later rediscovered and employed, particularly in Queensland (Freeland 1968:207).

The archaeological evidence, where it can be defined, suggests that after the hurricane, houses were rebuilt on the sites that they had previously occupied and that certain alterations and adaptations were made to them. The church however was never rebuilt, and the timber was re-used in other buildings (HRA 1 xxvi:373).

Vernacular architecture

Throughout the whole period of the settlement the housing of the men remained as described. Projected barracks were never built. During the earlier period the prefabricated buildings were erected on temporary piling and huts were thrown up from materials at hand. The local ironstone was quarried on the spot into rough blocks and mortar was made by burning shells for lime and mixing it with clay, as demonstrated in the archaeology. The chimneys of the married men’s quarters are the only remaining structural evidence of the earliest period of the settlement, apart from the few ironstone pillars that mark the site of Government House. Roofing materials appear always to have been split shingles probably made from casuarina trees, or bark, or thatch made from rushes.

In general, the technology of the architecture at Port Essington reflects the traditions of the men who built the buildings and adapted them to a strange environment. Apart from the prefabricated buildings which had timber floors, the use of beach shell flooring reflects the common use of mixed sand and lime ashes for this purpose in Britain at this time (Allen 1849-50:41; Smith 1834:22). The shells from which lime was made were burnt in kilns, of which three were recorded in the settlement. All three are of similar design, being built of stone in the shape of a beehive. The kiln to the south of the settlement is freestanding and may have been used for charring timber for charcoal (CO 201/323: McArthur to Gipps 3.11.1841 in Gipps to Stanley 3.11.1842). The example immediately north of the jetty is badly deteriorated, but could not have stood higher than 2 m. An earth platform was built behind it and excavation demonstrated that it was used to produce lime. However it appears to have been only a prototype for the third kiln, also used to produce lime, built into the cliff-face to the west of the settlement and standing to a height of 4 m. Both these kilns functioned in the same way. The large kiln had a flue as well as a larger opening at the base and in the top. It was loaded from the top with successive layers of shell and fuel and fired from beneath. When the firing had taken place the lime was shovelled out from below (Feacham 1956-7:50). This kiln remains a classic example of a pre-1850 British lime-kiln (Hudson 1965:138) and its building reflects an excellence of construction that suggests that it was probably the work of the convict masons who were at Port Essington in 1845 (see below).

The wreck of the Pelorus in many ways proved a blessing for the settlement, for it remained there through all of 1840, and its crew provided an important additional labour supply. One of its crew was a brick maker by trade and was able to fill an important gap in the skills of the garrison. McArthur had reported the discovery of a fine bed of clay at the head of Wanji-Wanji Cove to the south of the settlement, but experiments had failed to produce suitable bricks for want of an experienced man to burn them (CO 201/313: McArthur to Admiralty 3.11.1840 in Barrow to Stephen 10.5.1841). Private Handy, a marine serving on board the Pelorus, was enlisted to make bricks to be employed in enclosing the area beneath the first hospital (VSD).

The bricks that Handy produced were made the way they had been traditionally made in England and Europe for several 122hundred years and essentially as they would be made in Australia until about 1870. The pug was pushed into an open topped wooden mould with a removable base. When formed, the brick would be slipped from the mould and dried for several days before firing (Freeland 1968:13-14). The Port Essington bricks were, by modern standards, extremely poor quality. They comprised c. 20% clay and 80% sand, bonded with ironstone nodules. They were not highly fired and consequently porous and soft. They were not frogged and were irregular in size, but they were a technological achievement in the tiny settlement and McArthur was elated with their possibilities (Anon 1843a:29). However, Captain Chambers of the Pelorus when he sailed from Port Essington in March 1841, would not allow the brick maker to stay, despite the fact that the man volunteered (Anon 1843a:21) and although McArthur reported that Private Handy’s assistant from the garrison was attempting to continue production, the archaeological evidence suggests that he failed, since no other buildings apart from VSD were constructed in this material.

During the period 1840-1841 the settlement was the scene of much activity, restoring the damage of the hurricane and developing the settlement. A primitive saw-pit was excavated in the cliff to the north of the jetty and wanting any experienced sawyer, the garrison learnt to produce planking and battens for the buildings. The blacksmiths made nails, pointed the mason’s tools, and constructed iron-work for the buildings, which McArthur deemed necessary following the destruction caused by the hurricane (Anon 1843a:29). It was probably the memory of that experience which determined a change in style of the buildings constructed in this period. The old hospital was dismantled and the ground excavated to provide a level surface into which solid stone and brick foundations were sunk. The ground floor was then constructed of bricks and the prefabricated wooden structure replaced to form a second storey above, entered by external stairs from the western end. The store which was later to house Lieutenant Lambrick and his family (VQS) was also enclosed below with rough-hewn masonry which was built directly around the wooden piles (Figure 110). These were eventually eaten away by the white ants leaving gaps in the masonry. McArthur noted that much additional storage space was thus achieved (HRA 1 xxvi:374) but the walls aided the progress of the white ants and Earl Grey remarked that the later destruction of the buildings was probably thus accelerated a good deal for the sake of some additional accommodation (HRA 1 xxvi:373). The progress of Port Essington had taken one pace forward and two paces back.

The largest building complex of the settlement, the hospital, dispensary and hospital kitchen was begun in this period. A flat area 20 m by 35 m was excavated into the slope on the eastern side of Minto Head by the seamen on board the Pelorus (Anon. 1843a:20). At its deepest point this excavation was several metres deep and in the rocky soil the task must have been laborious with the inefficient tools at their disposal. In this level area the hospital was built upon ironstone footings c. 400 mm above the ground. Upon this was erected the pre-fabricated wooden structure that had been sent from Sydney in 1840 (HRA 1 xxvi:373). The stone foundations were divided into four compartments and it is reasonable to assume that the four wards in the building followed the pattern of these foundations (ML A.1725: Sweatman’s journal II:257). From a watercolour of the hospital in Sweatman’s journal, probably painted by Brierly, it appears that the building was surrounded by a verandah and that the four corners were enclosed to form additional rooms. Since, according to Sweatman, the doctor lived at the hospital, he may have occupied one of these rooms.

Figure 110. Quartermaster’s Store, looking east. Note the original piles had been encased in stonework when this drawing was done, dating it before 1843. Watercolour by Owen Stanley, entitled Storehouse Port Essington. Mitchell Library PXC 281 f.63b. Published with permission of the Mitchell Library.

123In external appearance the hospital had the classic features of the primitive Australian farmhouse of which the earliest example, Elizabeth Farm at Parramatta in New South Wales, had been built in 1793. The enclosed rooms at each corner were a distinctive feature, and because of the verandah, the roof line which began at the normal pitch necessarily became shallower to allow head-room, resulting in the broken-backed appearance of the roof, which was also hipped at both ends. The verandah seems certainly to have been intended to provide external access rather than shade and in this it again echoed the earliest use of the verandah in Australian architecture (Freeland 1968:22, 45–7). From the illustration by Brierly the hospital appears to have been roofed with thatch.

Although only one brief mention occurs of the hospital dispensary (ML A.1725: Sweatman’s Journal II:257) this has been recorded archaeologically and was situated adjacent to the hospital in the north-west corner of the excavated area. It was a small building with the western wall built of rough masonry. The remaining walls were probably of thatch and the structure was divided into two compartments by a brick wall, where the few bricks remaining from the storehouse were utilised, thus equating it in time with the building of the hospital proper, which was reported almost complete in September 1841 (Anon. 1843a:29).

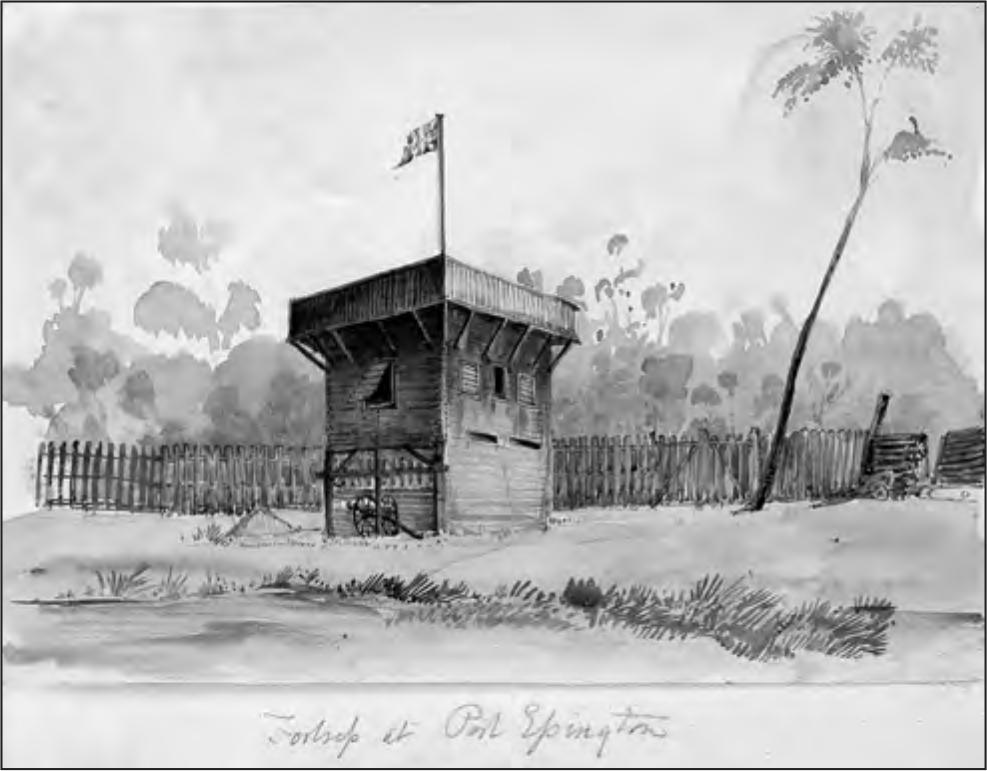

By this time also work was almost complete on the magazine and blockhouse on Adam Head (Figure 111). The magazine was built completely with masonry and set 1.5 m into the ground to minimise damage from an accidental explosion. The blockhouse, breastworks, and 2.75 m high palisades were all of timber and have disappeared without trace, but from Owen Stanley’s sketch (ML C281a) the blockhouse must have stood about 9 m high. It was probably at this time that the ditch and bank fortification to the south-west of Adam Head was constructed.

The jetty had been completed in April 1839 under the direction of Lieutenant Stewart of the Alligator and he recorded that it was 100 yards long and 24 feet wide and 10 feet high at its outer end, built entirely of stone. ‘I flatter myself’, he wrote ‘that it is the best job in the Coloney … it will answer for this port for some years to come’ (RGSA Stewart journal). Less than seven months later it had been completely destroyed by the hurricane. It was rebuilt by the men of the Pelorus but McArthur recorded that it was not as strong as before (Anon. 1843a:29).

Figure 111. Blockhouse and breastworks on Adam Head. Note magazine to the left of the structure. Watercolour by Owen Stanley, entitled The Fortress at Port Essington. Mitchell Library PXC 281 f.119. Published with permission of the Mitchell Library.

By the end of 1841 the settlement had developed sufficiently to meet the needs of the tiny garrison. Until a decision could be reached on the opening up of Port Essington, little could be done, or needed to be done in expanding the post. All the public buildings had been erected, the men were housed, and the modest technological needs of the garrison catered for. There were sufficient storehouses, and kilns, a smithy and a primitive but effective bake house for baking bread.

Professional architecture

The second phase of architectural expansion was brief but recognisable from the structures which arose. In January 1844 20 picked convicts, all masons and quarrymen, sailed from Sydney to construct a beacon at Raine Island in the Barrier Reef (Ritchie 1967:300). Completing the work there in September they embarked in the Fly for Port Essington, where Captain Blackwood deposited the convicts while he went to Sourabaya (ML A1531-3 Deas Thomson papers III: Blackwood to Deas Thomson 18.4.1845). Their arrival at the settlement was opportune, for a week earlier McArthur had reported the re-commencement of work on the beacon at Smith Point at the mouth of the port. The work had been begun by the ship’s crew of the Chamelion, but proved unsatisfactory and what had been constructed had been condemned and removed (RMAP Port Essington Correspondence: McArthur to Owen 18.4.1845). From the remains at Smith Point it would appear that the newly arrived convict masons took over the work and the beacon became a solid round tower of blocks of coral conglomerate quarried on the spot. One dislodged block is inscribed ‘E CRI’ and one ingenious suggestion is that this is part of ‘LUCE CRISTI’ and thus probably associated with a Catholic missionary who lived in the area several years later. However the fine gothic lettering would suggest that it was the work of a qualified tradesman. The beacon was finished at the end of 1845 (ML A.501-3: Brierly journal entry 14.11.1848).

The finest piece of architecture in the settlement, the hospital kitchen, has to be associated with the four months the convict masons spent at Port Essington. In striking contrast to the other architecture in the settlement, this building has all the aspects of professionalism. The Georgian symmetry, reflected in the ground-plan, is apparent, and the design was almost certainly a stock pattern. Smith (1934:38 and passim) gives a number of standard designs, of which his No.1 is very similar to the Port Essington hospital kitchen. In the detailing of the building professional expertise is also apparent. Wide footings were sunk into the ground and the floor level raised above the surrounding ground level. The doorways and windows were rebated to take timber frames and sills, all corners were quoined with finely chiselled blocks, and the elaborate chimney, since it served two fire places, was constructed with two flues which were parged.

The large lime-kiln to the west of the settlement, already discussed, reflects similar expertise, and lacking any documentary evidence can be attributed to the same period on this basis. Finally, the smithy was rebuilt at this time and had a fine stone chimney standing approximately 6 m in height, which has fallen in the last twelve years. The base remains, however, to suggest the technology of the structure, and because it contains some blocks of coral conglomerate which were presumably brought back to the settlement from Smith Point, can be dated to 1846. This date is in accordance with a brief reference to the smithy by McArthur (HRA 1 xxvi:374).

No further building took place in the remaining years of the settlement, with the exception of several vaults in the cemetery, and the obscure structure named during field work 124as the Cowrie House. On archaeological grounds this can be dated late in the life of the settlement because of the re-use of stone blocks from other parts of the site. The cowries found in the deposit can best be explained as having some commercial value and may be associated with a man named Rae (or Ray) who is incidentally recorded as having established a trepanging camp in nearby Knocker Bay (ML A.1725: Sweatman’s journal II:273) and who may well have had some sort of storehouse at the settlement to facilitate the shipment of his goods.

The archaeological survey of the site recorded four wells around the settlement, although Brierly noted that only two were functioning in 1848 (ML A.501–3: Brierly journal entry 14.11.1848). The first of these was the well in the town square, which seems to have been able to maintain the settlement at all times. The second was some distance to the west, and presumably served the garden there.

Kitchen gardens and tropical horticulture

The gardens consumed much of the garrison’s time and many despatches and descriptions of the settlement were taken up with this aspect of life at Port Essington. Apart from the small private gardens which were planted around each hut, two main gardens were established; one to the south of the settlement behind the beach, the other to the west in the vicinity of the cemetery.

From the outset, Bremer’s despatches were full of optimism on the potential of the soil of the Cobourg Peninsula. In December 1838 he declared that every description of spice, together with sugar, rice and excellent cotton might be grown. In February 1839, despite light rains in the wet season, he reported the orange, lemon, banana, plantain and coconut trees in excellent order, and again in April he wrote, ‘The soils are exceedingly rich; plantains, bananas, orange, lemon and tamarind trees are flourishing’ (Anon. 1843a:9). In addition, sugar cane and cotton were succeeding and strong hopes were held for the potential of rice. Notwithstanding this, Bremer reported the want of vegetables as the major source of deprivation in the settlement.

In this, as in other aspects of the settlement, Bremer appears to have been swayed by success to the point of not acknowledging the difficulties involved. The seasons and climate were not understood, and although Armstrong had been appointed as official gardener, his practical ability appears to have been in doubt in so foreign an environment. In July 1840 McArthur reported that the winds had adversely affected the gardens. The pumpkin and maize crops had failed to produce to the extent anticipated, although the experience had led to the replanting of maize in the western garden where it improved. By the end of the year the gardens had produced c. 820 kg of vegetables, mainly pumpkins, and the melons and sweet potato were also thriving (Anon. 1843a: 14, 16–18).

This was in essence subsistence gardening. Of the agricultural potential of the area McArthur was more reticent, noting that a few people who professed some expertise were unanimous in saying that sugar, coffee, cotton, indigo and rice might all be grown successfully. Armstrong had failed with sugar cane, although McArthur, writing to Gipps at the end of 1840 (Anon. 1843a: 16-18) thought that perhaps this was due to his inexperience. McArthur noted that any success would require ‘skilful, practical men’, whereas in his own garrison there were not enough men to maintain the gardens in sufficient quantity to sustain themselves all the year around.

Gradually the settlement learnt by experience. In September 1841 McArthur’s report reflected the general successes and failures of the crops, together with the increasing dependence on the tropical crops with which they were slowly becoming acquainted. It is of value to quote this despatch at length:

The gardens have produced well; we have cut nine very fine pines; fifty-five bunches of bananas, some of them containing six dozen each, of excellent flavour. The cocoa-nuts do not seem to thrive. The orange has not yet bloomed; two lemons, of large size and well-flavoured, have been gathered, and there are many coming forward on two of the trees.

Melons decidedly degenerate, but having received some new seed from Sydney, I hope to improve them by giving some attention in selecting and reserving the fruit intended for seed. But I am told that this is an universal complaint of this plant.

Sugar-cane will doubtless answer well here, all visitors, who appear acquainted with its properties, speaking well of our grown specimens, and they have not been at all attended to.

Indigo, and the cotton, though totally neglected, have attracted much attention.

The soil appears to be peculiarly favourable to arrowroot. I have made some, and it proves to be of an admirable quality. We have more than sufficient, I hope, to supply our hospital, and the next year’s crop will be (if as successful), at least, tenfold more.

Two bread-fruit plants were brought here from the islands about 12 months since, and I have given much attention; but am very doubtful if they will spring. We have also two mangoe plants; but they do not grow, and the loquat has failed. I must remark that it has been a considerable disadvantage to the pursuits of gardening that I have not had time to devote, or the hands requite to apply to it. There are too many objects to be effected with so limited a detachment.

A few seeds of the Amboyna pea, discovered amongst some maize landed from a vessel, succeeded beyond all expectation. When served at table we generally deemed it quite equal to the common kinds of green peas; since its introduction all the species of island beans and calavances have been discarded, and only valued on account of their beautiful foliage and splendid appearance when in blossom, producing a large cone of flowers, in colour and form resembling the well-known may-duke. It is curious that none of the live stock will eat any of these productions, not even when intermixed with other food that is acceptable to them.

We have now, by supplying the ships’ crews, exhausted our stock of potatoes; it would have served the garrison very well until the next rains. This is decidedly our most profitable vegetable; it will always be cultivated with the least labour. We have not had a satisfactory trial of the yams, but are fully prepared for it on the approach of rains.

I regret having miserably failed with the potatoe onion, introduced also from the islands. I purchased and planted 80 pounds, and only saved a few for the sick, with about one pound reserved for seed. They were put (by advice) in the ground in December, and the continuous wet weather completely destroyed them.

I propose this season to extend the potatoe plantations. Indian corn and Amboyna peas will also merit attention.

I have only employed two men for the last three 125months as gardeners; their attention is now directed exclusively to watering the plants, and watching against depredations (Anon. 1843a:30).

The processes of learning by experience were thus often painful and slow. Earl reported, for example, that under cultivation the yam, sweet potato, and other root crops flourished too luxuriantly to produce (RGSA Earl Correspondence: Earl to Washington 9.6.1841) and Leichhardt noticed that melons and pumpkins although large were quite tasteless (ML C155: Leichhardt Journal 1845:433). Leichhardt noted the introduction of the cactus Opuntia ficusindica (‘prickly pear’) for the cultivation of cochineal insects, which had been suggested in his report by Captain Everard Home (Hodgkinson 1845:115-9). Prickly pear is one of the few introductions of this period which still thrives at Port Essington.

In 1849 Owen Stanley reported that the first garden (that to the south of the settlement) had been a complete failure, although the second was still supplying coconuts, pineapples, bananas, jack fruit, and oranges (HDL SL.15f: Stanley to Deas Thomson 17.4.1849). However Stanley viewed the settlement with disfavour throughout its existence, and in summary it would be fair to say that McArthur’s diligent application to the problem resulted in reasonable success in keeping the garrison supplied with fresh vegetables.

Earl noted that these efforts were supported by information and gifts of plants and seeds from the governors of Amboyna and Dili and especially from the consul-general of Portugal at Singapore (Earl 1846:105-14). Earl’s remarks on the gardens substantiate what has already been said. It is interesting to note however, that he maintained his belief in the agricultural potential of the region. Although admitting the failure of coffee, he claimed success for sugar cane and spices, and in particular for cotton. The first variety grown was the type common to the Archipelago, which, although it succeeded, was not of high quality. In April 1842 seeds of Bourbon and Pernambuco cotton were planted and Earl submitted the product to an English cotton broker who pronounced it of good quality. Since all such experiments were carried out on a limited scale, Earl felt that the potential of agriculture was not shown to be worthless. The history of Northern Territory agriculture since suggests however that Earl was overly optimistic.

Local game and introduced livestock

Amongst the land fauna the kangaroo and wallaby appear to have been the only species utilised for food by the Europeans. Earl (1863:7) notes that kangaroo hunting was a specific task in the garrison and the excavated food remains of the Europeans include kangaroo bones. Beyond this, fresh meat seems to have come mainly from livestock introduced into the settlement from the adjacent islands. Pigs, Timor ponies, buffalo and island cattle (bantang) had been released at Raffles Bay at the abandonment of that settlement. The buffalo had strayed off the peninsula by 1839 and had greatly increased in numbers. Earl noted that herds of 40 or 50 could be found at the neck of the peninsula (Earl 1846:103) and the introduction of the buffalo fly (Siphona exigua), the cattle tick (Boophilus microplus) and the cattle disease onchocerciasis have been associated with these introduced animals (Letts nd:23-4).

These livestock introductions continued throughout the lifetime of Port Essington and included – in addition to pigs, ponies, bantang and buffalo – sheep, goats, English cattle from Sydney, poultry purchased from the Macassans, and dogs to assist in the pursuit of the kangaroo. The livestock however required more handling than McArthur had men available to perform and they constantly strayed and became wild (Anon. 1843a:30).

Again, the lack of knowledge of the environment was apparent. Campbell had noted that the sheep taken to Melville Island never became fat or fit for food (Letts nd:25) but these animals continued to be imported into the settlement. Earl recorded that of more than one hundred sheep purchased by the Essington during her first voyage in 1838, nearly one half died before reaching Port Essington (Earl 1846:52). Stock losses from Sydney were equally great, and McArthur reported that of 45 buffaloes embarked on the schooner Lulworth only 14 were landed, of which two had died before he sent the despatch (Anon. 1843a:15).

Once arrived at Port Essington the stock had to be hand-fed, since some of the indigenous flora proved poisonous and many sheep and goats and to a lesser extent the cattle died from the effects of this (Anon. 1843a:30–31). Sheep particularly seemed to have suffered in the tropical climate, but their importation was continued until Port Essington was abandoned (AONSW 4783 Lambrick letter books In Letters no. 126: Sydney Commissariat to Lambrick 3.4.1849). This letter lists 51 sheep shipped to Port Essington in 1849.

Malaria: onset

Not only the animals but also the men gradually succumbed to the strange environment. For the first four years the garrison remained free of widespread sickness and in April 1839 Bremer had written to his wife that there had been no medical cases in the garrison and that the two men who had so far been buried in ‘the calm and peaceful spot’ chosen as a cemetery had been from amongst the ships’ crews (NLA G.743 Owen Stanley Papers: Lady Bremer to Mrs Edward Stanley 6.11.1839). But gradually the signs asserted themselves. In September 1841 McArthur reported two cases of intermittent fever and four cases of diarrhoea (Anon. 1843a:29) and twelve months later the assistant surgeon furnished a medical report for the period July to September 1842 which listed 19 cases of which five were of intermittent fever (Anon. 1843a:47). However health in the garrison was still generally good and Whipple attributed this to the good position of the settlement, the regular habits of the men, and their temperate way of life, noting the strict prohibition of liquor to any improper extent.

The wet season of 1842–43, was prolonged and severe, and with this came the first widespread outbreak of malaria. When the Fly visited the settlement in August 1843 Jukes found that all there had been attacked by the disease and that there had been several deaths (Jukes 1847 I: 350–1). Many were still hospitalised, and they had become a garrison of ‘yellow skeletons’ (Browne 1871:199). Without a labour force the little settlement was immediately paralysed and steps were hastily undertaken for the relief of the garrison.

The second garrison 1844–49: holding on

Home and McArthur both wrote to Parker, the commander-in-chief of the East India Station, who wrote to the Admiralty (RMAP Port Essington Correspondence: Parker to Admiralty 18.6.1843) and the formation of a relief detachment was begun. It was not until November 1844, seventeen months after Parker’s communication that the relief party reached Port Essington. The second detachment consisted of two lieutenants, an assistant surgeon, three sergeants, three corporals, a fifer and forty-seven privates (RMAP: Port Essington personnel list) men as ill-equipped to maintain the settlement as the first detachment had been to begin it. Although the details are incomplete, the majority of men had their civilian occupations listed as labourers, and the detachment contained no masons, brick makers or bricklayers (RMAP Port Essington Correspondence: Lawrence to Owen 5.3.1844). 126

Malaria: taking hold

By now malaria was established in the settlement and within twelve months every man in the new garrison had suffered from it, and in 1845 and 1846 there were nine deaths, in addition to the wife of Lieutenant Lambrick (RMAP: Port Essington personnel list). One of the two Lambrick children had died before reaching the settlement, the other died at the settlement. In May 1846 McArthur requested an additional medical officer and in October 1847 Surgeon Crawford, together with an additional lieutenant, corporal and five privates, arrived at the settlement (RMAP Port Essington Correspondence: McArthur to Owen 13.10.1847). During 1847 there appears to have been some improvement in the health of the men, but again in the wet season of 1848–49, malaria laid waste to the garrison in the worst epidemic experienced in the settlement. Crawford later recalled the situation in writing to Lambrick: ‘I cannot think of Port Essington without a shudder, what a fearful state we were in in 1849 when all but yourself and two others were attacked by fever. I believe but for your immunity from fever and your great exertions and intelligence on behalf of the sick, we should have lost many more men. Do you recollect during my lucid intervals your visits to my bedside for instructions on how to treat the sick? The care of the sick and dying lasted six weeks’ (RMAP typescript: ‘Services of General George Lambrick’).

The cause and transmission of malaria was unknown at this time. Earl (1846:90–8) discussed it at some length, and came to the conclusion that throughout the Indian Archipelago it was always the land-locked harbours which were affected most by malaria. He thus attributed the cause to the mangrove swamps and mud banks which were uncovered at low tides together with the effluvia produced by the effects of the hot sun on stagnant salt-water. In support of his case he referred to the early period of the settlement stating that the hurricane had sufficiently agitated the waters of the inner harbour to purify the shoreline, and thus there was little malaria in this period. Earl reflected the popular ideas on the disease at this time, and it is of interest to note that Leichhardt discussed the problem in an analytical fashion which says much about the man (ML C155: Leichhardt Journal 1845:438–9). Firstly he dispelled the ideas that after rain malaria rose into the atmosphere. ‘After heavy rain the air smells fresh and pure; no nasty offensive exhalation rises from standing pools filled with decomposed plants or from morasses in which either … gas, or sulphuretted hydrogen or the unknown agent which we call malaria might be engendered … I should therefore say that the air and the country have nothing whatsoever to do with the fever of Pt. Essington’. Leichhardt recorded that he was told by two members of the garrison that the fever ceased when the country around the settlement was on fire, and that the Aborigines had told them that they used fire to keep down disease as well as to facilitate travel around the country. Assuming this to be true, it is an intriguing additional explanation for Aboriginal dry season landscape firing that is rarely discussed.

Leichhardt felt that the diet of the men was sufficiently good to eliminate this as a cause, and he and McArthur in discussing the problem noted the coincidence of outbreaks of malaria with the arrival of trading ships from Timor which had happened on several occasions. Tantalising half-clues were at their disposal but the association of these conditions with the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito was not to be discovered for another 50 years, during the construction of the Panama Canal.

Leichhardt noted that the disease was treated with mercury until salivation took place, when the patient was considered safe. Quinine might also have been used as this was listed in medical supplies from Sydney (HRA I xxiii:554). McArthur, believing that the settlement was not sufficiently exposed to the sea breezes, accidentally hit upon the best practical solution available to him and sent patients to convalescent stations established at various places in the area and thus away from the established malarial habitat. Parsonson (1965) demonstrates that the anopholine mosquito lives in specific environmental conditions and that a sea breeze of c. 12 kph is sufficient to inhibit activity altogether. The average feeding flight for a female Anopheles mosquito is c. 180 m and by removing convalescing patients to other coastal areas, McArthur unwittingly took them away from the place where malaria might be reinforced by additional infections. These convalescent stations included Croker Island, Smith Point, Coral Bay, Observation Cliff and Spear Point (ML C155: Leichhardt Journal 1845:432; Earl 1846:91; ML A.501-3: Brierly journal entry 14.11.1848; Anon. 1843a:37). The remains of the stations at Coral Bay and Spear Point were located during fieldwork but were not excavated.

Apart from malaria the garrison suffered continuously from a number of other ailments. Ophthalmia caused perpetual distress, and scurvy and diarrhoea occurred frequently. One case of cholera was recorded, and a number of other diseases reported. When the settlement was finally abandoned, one return showed that of the original garrison of 64, only 37 men were evacuated. Of the others, 14 had previously been relieved because of ill-health and 13 had died, a death rate of more than 20% in less than five years among mostly young men (McIntosh 1958:17).

Small group personality conflicts

In a garrison so small, personal disputes were inevitable and often grew out of all proportion to their causes. Nevertheless they had a disruptive effect on the administration of the settlement and occasionally impeded its progress.

In the first few months of the settlement hostilities flared between Bremer and John Armstrong, who had been appointed as botanist and gardener at Port Essington. Armstrong wished to pursue the scientific side of his appointment, but Bremer, naturally concerned with the immediate wants of his garrison, denied any knowledge of the botanical collecting aspect of Armstrong’s position, although it had been specifically stated in Bremer’s instructions (RBGK RICH 1171: Armstrong to Smith 23.11.1839). After Bremer left the settlement Armstrong’s dissatisfaction continued with McArthur, and in July 1840 he refused to continue working in the gardens (NMMA CHR/23 MS 63/017: McArthur to Chambers 20.7.1840) and eventually left the settlement in November 1840, going to Timor from whence he wrote complaining bitterly of the selfishness, pride and ignorance that were the predominating rules by which Port Essington was governed (RBGK RICH 1171: Armstrong to Aiton 7.12.1840).

When Bremer returned to Sydney in July 1839 the Sydney Morning Herald (10.7.39) and the Australian (20.7.39) printed long and flattering accounts of the settlement and its progress. In May the following year the Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser (4.5.1840) printed a 5,000 word letter purporting to come from residents at Port Essington who signed themselves Paul Pry and Quite Correct and who launched a bitter attack upon these earlier reports. ‘We cannot of course judge’, they wrote, ‘of the appearance Victoria presented to the admiring eyes of the Alligator’s [crew] as they were about quitting these ‘delightful shores’; but on a closer view we can safely answer that the idea of a village, and especially a considerable one would not, by many be easily conceived – ‘twenty four cottages!’ (kennels) ‘with gardens!’ 127and ‘all comfortable’; excessively so! particularly during the late hurricane, when they all came tumbling about the ears of their occupants’.

From here the dispute passed into the pages of the Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle (1842:86–8) which published an anonymous refutation of the adverse newspaper report which the writer attributed to officers of the Britomart. Owen Stanley, the captain of the Britomart privately accused the naturalist John Gilbert, who was at Port Essington at this time, of writing this article, which said Stanley, imputed neglect of duty on the part of himself and his officers (NLA G.743 Owen Stanley Papers: Gould to Gilbert 24.8.1844). In consequence, it was probably Stanley who wrote to the Nautical Magazine (1843:662-5) not denying that the Britomart’s officers had been responsible for the original newspaper letter, but giving total support for the sentiments expressed in it and reiterating them at some length, concluding that should the government wish to retain Port Essington then they should make it a penal settlement if severity of punishment were to be the object in view. This letter is signed ‘An Officer in H. M. Navy’, but can be attributed to Stanley with reasonable certainty.

Such publicity of course did the settlement great harm at a time when the government was attempting to open land leases there. Bremer, considerably upset, wrote to Chambers, captain of the Pelorus which was still at Port Essington, demanding that he swear that he had no knowledge of the letter (Adm. 50/262: Bremer to Chambers 2.12.1840). Chambers was likely innocent of the charge, but the basis for Bremer’s suspicions was another long feud which took place throughout the period the Pelorus was at Port Essington (late 1839 to March 1841).

When Bremer had been unable to return to Port Essington in 1839 he had ordered the Pelorus to go there with the supplies that were urgently required by the garrison, and that ship had been subsequently wrecked in the hurricane. This, reported Earl (RGSA Earl Correspondence: Earl to Washington 13.7.1840), was the cause of much discontent, as the ship had been about to return to England, and the officers held Bremer responsible for their misfortune. In another letter, Earl complained of the want of fixed government, stating that since Bremer’s departure, Kuper, Bremer’s son-in-law and then captain of the Pelorus had ‘taken the reins out of McArthur’s hands on the plea of being senior officer’ (RGSA Earl Correspondence: Earl to Washington 17.3.1840).

Earl may have been confused on this point, and it was likely Chambers rather than Kuper who usurped McArthur’s authority. In January 1840, Bremer despatched Captain Chambers in the Alligator to Port Essington from Trincomalee with orders to take command of the Pelorus after handing over his ship to Kuper, and to take his further orders from Kuper (NMMA CHR/23 MS 63/017: Bremer to Chambers 28.1.1840). These orders were quite explicit, instructing him that although the garrison was placed on the books of the Pelorus for purposes of victualling, he was not to interfere with the garrison under McArthur’s command, and was to offer every assistance to the settlement (NMMA CHR/23 MS 63/017: Kuper to Chambers 18.3.1840). This Chambers did not do, claiming that as senior officer at Port Essington he was the first authority in the place, and authority vested in McArthur by Gipps gave McArthur no authority over Chambers, nor the naval marines in the settlement. The long correspondence between the two (NMMA Chambers Papers CHR/23, CHR/24 passim) reflects this basic conflict over a number of extremely minor issues. But Chamber’s destructionist policy in conjunction with McArthur’s blind adherence to regulations seriously impeded the progress of the settlement and the repercussions of the tension between the two unsettled the whole garrison.

Eventually the dispute was laid before Sir Gordon Bremer, who in December 1840 wrote to Chambers reiterating the instructions he had been given and stating that McArthur was in complete command of the garrison ‘and must not be interfered with, but assisted in every way’ (Adm. 50/262: Bremer to Chambers 2.12.1840). It is possible that Chambers did not receive this letter, for on 17 March 1841 he sailed from Port Essington, refusing to leave behind the brick maker, and also refusing to disclose his destination to McArthur (CO 201/323: McArthur to Gipps 3.11.1841 in Gipps to Stanley 3.11.1842).

Although Chambers was in the wrong in this instance, McArthur’s intractable personality was unsuitable for the post he commanded. Nor was this instance isolated. In 1848 he called on Owen Stanley to adjudicate in a dispute between himself and Lambrick (HDL SL.15f: Stanley to McArthur 13, 14, 15.11.1848) and Huxley wrote that although there were only five officers in the settlement, ‘there is as much petty intrigue, caballing and mutual hatred as if it were the court of the Great Khan’ (Huxley 1935:149).

Such passions were not the sole prerogative of the officers however. Leichhardt recorded that on reaching Port Essington, and announcing that Gilbert had been speared to death on the journey, an unnamed marine broke down in despair, for he had volunteered to go to Port Essington with the explicit intention of killing Gilbert when the latter arrived there for having seduced the marine’s sister (ML C155: Leichhardt Journal 1845:431).

The tyranny of isolation

If the marine survived the rigors of the following years he must surely have expiated his guilt. The loneliness of the isolated settlement meant long hours of boredom, and Port Essington can be seen as a microcosmic example of the situation which was repeated a hundred times in the early history of Australia – those small, artificial, male-dominated societies that gave rise to the Australian legends of hard drinking and mateship. McArthur tried to curb drunkenness in the settlement, and felt no compunction at sentencing marines to seven days in irons on bread and water for being drunk and fighting (NMMA Chambers Papers CHR/23: McArthur to Chambers 10.3.1841) but the substitutes he offered for entertainment and relaxation – a theatrical performance (Christie nd: entry for 24.8.1839), a regatta, and athletics (CO 201/323: McArthur to Gipps 3.11.1841 in Gipps to Stanley 3.11.1842) were perhaps poor substitutes for those who wished to escape their banishment in a bottle of rum. The harmonica reeds recovered in the excavations bear testimony to the simple entertainments to be had living in the Australian bush, and the growth of Australian bush ballads from the traditional songs of England are readily understood in conditions such as those at Port Essington. There can have been little relevance in the news that the Bishop of York had been thrown from a horse, but was feeling better, or even that in France Ledru Rollin had been removed from office and that other members of the Republic were ‘tottering’ (ML A.501–3: Brierly journal entry 16.11.1848) in a settlement which years before had been so short of supplies that all the men were barefooted (Anon. 1843a:16), and dressed ‘almost entirely’ in cotton cloth purchased from the Macassans (RGSA Earl Correspondence: Earl to Washington 9.6.1841).

Aboriginal contact

Any fears that the Aborigines might be hostile towards the garrison were quickly dispelled and the two groups lived harmoniously throughout the lifetime of the settlement. This 128can be attributed partly to the work that Barker did at Raffles Bay, partly to the fact that the Aborigines were accustomed to the visiting Macassans (and the effects which that contact had had upon them) and partly to the deliberate policy of non-confrontation that was adopted by the British at Port Essington. Although the garrison hunted the kangaroo and wallaby, fished and ate shellfish, the Europeans were too few to threaten the economic basis of Aboriginal life. Indeed, to some extent the Aborigines appear to have supplied the settlement with foodstuffs, collecting shellfish, turtle and the hearts of the cabbage tree palm for the garrison (Sydney Morning Herald 21.6.1840) although they could never be induced to work in the settlement for more than several days at a time.

However the Aborigines were eager for the goods that the British brought with them, particularly metal, cloth and tobacco. Sweatman recorded that ‘every child that can walk has a pipe in his gills and I have seen men get absolutely intoxicated on smoke alone’ (MLA.1725: Sweatman’s journal II:272). Sweatman felt, however, that they had not adopted the European vices as much as might have been expected, and were not very fond of liquor. The prevailing attitude of those who wrote about the Aborigines at Port Essington was that they were naive, fun-loving curiosities and even McArthur, who was well-disposed towards them, on several occasions expressed amazement when they exhibited the human emotions of kindness, sympathy or humour (e.g. Anon. 1843a:31).

McArthur’s policy towards the Aborigines, as in other things, was governed by his instructions and regulations. A good deal of petty pilfering took place throughout the lifetime of the settlement and whenever offenders were located they were punished. Usually this took the form of solitary confinement for a night, which seems to have been considered greater punishment than flogging by the Aborigines. One point in McArthur’s conflict with Chambers was when the latter had an Aborigine flogged without first informing McArthur, who was distressed not by the act, but rather because it undermined the idea of authority vested in himself alone, by which the concepts of British justice might be inculcated in the indigenous people. To some degree McArthur succeeded in this policy and he recorded an incident where a wronged man came to him demanding justice (NMMA CHR/23 MS 63/017: McArthur to Chambers 27.1.1841). The clearest example of McArthur’s attitude to the task of bringing European law to the Aborigines came in 1847, when the single occurrence of bloodshed between the two groups took place. Two native men and a boy had stolen from the settlement, and Sergeant Masland was sent across the harbour in a boat to arrest them. The arrests were made, and the goods recovered, but returning to the settlement in the evening the prisoners freed their bonds and dived overboard. The boy was recaptured, but after vainly attempting to recapture the other two, and calling upon them to ‘halt in the name of the Queen’ one of the men was shot dead. McArthur sent Masland to Sydney to stand trial for murder, where he was exonerated (ML A.501–3: Brierly journal entry 4.11.1848). McArthur appears to have been less concerned with the loss of life than with his own personal record, and noted ‘It is to myself peculiarly painful as I have been want to look back with satisfaction on the years during which it has been my gratification to say ‘No blood has been shed’’ (RMAP Port Essington Correspondence: McArthur to Owen 13.10.1847).

The influences of each group upon the other remained superficial. Clothes were distributed to cover the nakedness of the Aborigines but McArthur reported that these always disappeared immediately (Anon. 1843a:18) presumably traded into the interior together with iron. On his trip to the interior of the Cobourg Peninsula in 1839, Stewart (RGSA Stewart journal) recorded Malay and European metal objects in a bark shelter. Metal was exchanged for stone weapons and implements for which few local materials were available on the coast. In this they were continuing a practice begun with goods obtained from the Macassans (Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle 1842:88).

From the archaeological evidence recovered from the excavation of the two Aboriginal middens near the settlement there is some evidence that the immediate region became a focus for the local tribe and that they became perhaps more sedentary during the life of the settlement. The analysis of glass implements illustrates the degree to which they became conversant with this new and ideal raw material for making implements, and a mention is made of the blacksmith making iron spikes with which to tip their fishing spears (NMMA CHR/23 MS 63/017: McArthur to Chambers 29.10.1840) replacing, presumably, wooden prototypes.

The lasting legacy of European contact, however, was as in other places, disease. Although no records are extant, it is reasonable to suppose that the Aborigines did not escape the malaria epidemics which beset the garrison. Previously both the habit of burning the bush, and a semi-nomadic life must have reduced to a minimum any malaria introduced by Macassans. There is some evidence of venereal disease (MacGillivray 1852 I:159) and it was also recorded in the garrison, so that it was very likely transmitted from this source to the Aborigines. Small-pox was known to the Aborigines when the Europeans arrived in 1838 (Adm. In Letters B.798: Bremer to Beaufort 7.12.1838) and may have been a result of Macassan contact. Later in the century this disease reduced an estimated 200 Aborigines on the peninsula to 28 (PC Howitt Correspondence: Robinson to Howitt 8.6.1880). McArthur reported in 1841 that the Aborigines had suffered severely from catarrh, chest complaints and ophthalmia (Anon. 1843a:31).

Interactions with Macassans

As might have been foreseen by the experience of Raffles Bay, any intended interception of the Malay trepang industry never took place. McArthur referred to this in 1842 (Anon. 1843a:38) by which time any real hope of establishing a commercial port via this avenue was gone. However the Macassans visited the settlement each year, partly for protection from the Aborigines, with whom there was occasional bloodshed (Anon. 1843a:13). and partly to carry on minor trading with the garrison. This consisted of some poultry, cloth, salted fish, rice, sugar, mats, baskets and Chinese earthenware (ML A.501-3: Brierly journal entry 4.11.1848; Anon. 1843a: 27, 32). From the amounts of this last item recovered in the excavations it is doubtful if all the Chinese pottery in the settlement came from this source, and it might equally be the archaeological expression of a reasonable (given the size of the garrison) trade carried on with the settlement by private traders with their bases either in the Dutch ports of the Archipelago or from Singapore or Hong Kong. Few precise details of these traders are extant and there appears to have been only one continuous visiting trader, Earl’s friend d’Almeida, who visited the settlement annually from Singapore from 1842 to 1848 (Earl 1846:67).

The overland route

Throughout the period of his tenure as Governor of N.S.W. Gipps remained strongly in favour of the retention of Port Essington, and as early as 1840 he put forward a proposal for exploration for a land route to the place (CO 201/299: Gipps to Darling 28.9.1840). The explorers Edward Eyre and 129Charles Sturt were interested in undertaking such an expedition and put forward a proposed scheme for the journey (HRA 1 xxiii:245–7) but since the estimated costs were £5,000 the proposal was not adopted. The idea was not forgotten, however, and in September 1843 the Legislative Council of N.S.W. set up a select committee to enquire into the feasibility of an expedition to find an overland route. Evidence was taken from a number of people, including Sir Thomas Mitchell and Earl, who was in Sydney at this time. Earl convinced the committee that Port Essington might yet become a flourishing entrepôt, and the Sydney Morning Herald (12.9.1843) came out in strong support for the scheme during the proceedings. The advantages to be derived from an overland route, said this newspaper, included obviating the dangerous sea passage through Torres Strait, opening up a ready supply of cheap labour from the north, and providing the means of exporting horses, cattle and possibly even sheep to India, particularly if the England-India steam route were to be extended to Port Essington.

The findings of the select committee were favourable to an attempt being made, and the Legislative Council asked for a vote of £1000 to put the plan into effect. However the depression of the early 1840s allowed no money for such expeditions and Gipps reluctantly refused, but immediately wrote to the Colonial Office asking their advice (HRA 1 xxiii:245-7). The reply was that the project might be approved when sufficient funds were available.

In October 1844, Gipps wrote to Stanley enclosing a second proposal for an expedition to Port Essington from Eyre, which created some conflict with Sir Thomas Mitchell, who had already offered (and virtually claimed the right) to lead any official expedition (HRA 1 xxiv:50-51). In passing, Gipps noted that a gentleman named Leichtardt [sic] was preparing to lead a small private expedition from Moreton Bay to Port Essington. The story of that epic of Australian exploration must be passed over here but the party left Moreton Bay in September 1844 and had been given up for lost when on 17 December 1845 McArthur was surprised by the arrival of ‘a thin, spare, weather-beaten and bent down man, wearing a long beard and well worn habitements’ (RMAP Port Essington Correspondence: McArthur to Owen 26.12.1845). Leichhardt wrote, ‘I was deeply moved at finding myself again in a civilised society, and could scarcely speak, the words growing big with tears and emotion. And even now, thinking that I have been enabled by a kind providence to perform such a journey with so small means, my heart sobs with gratitude within me’ (ML C155: Leichhardt Journal 1845:429).130