8

Improving quality in Australian child care: the role of the media and non-profit providers

It is widely acknowledged that the quality of centre-based care for young children is a critical determinant of a range of positive social, education and health-related outcomes (Barnett & Ackerman 2006; Vandell et al. 1988; Schweinhart et al. 1993). Yet in 2001, Australia ranked at near the bottom of an OECD league table measuring how much countries invest in children’s earliest years (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2001). Further, Australia’s quality assurance regime for child care has been criticised, particularly for its failure to make reliable or comparable information on the quality of child care services readily available to parents (Radich 2002; Hill, Pocock & Elliott 2007; Rush 2006).

In this relative information vacuum, parental choices about child care can be particularly affected by dominant constructions of what constitutes ‘quality child care’ in the public sphere. One key component of the public sphere is the mass media. Through its interpretation of events, the media can influence the way an issue is discussed and evaluated and so influence individual perceptions (Krippendorff 2004; Meyrowitz 1985; Gamson 1988). In this chapter we analyse recent media coverage of child care in Australia. We argue that media attention to issues such as the affordability and availability of centre-based child care and the physical environment in child care centres far outweighs the attention given to the quality of care provided. This has provided an opportunity for large corporate players with mass marketing strategies to further shape parents’ expectations. 204

So how can smaller, generally non-profit, child care centres play a role in the establishment of a well-functioning quality assurance regime? The public sphere is not just inhabited by the mass media or dominated by the marketing messages of large companies. There are other important sites where ideas are expressed and contested. In the case of parents forming judgements about child care, a key site is their own local child care centre, and among these centres, non-profit providers are particularly well-placed to play a significant role in shaping how parents understand and interpret child care. Further, through advocacy, non-profits can have an impact on child care policy. Thus, we discuss communication strategies available to non-profit child care providers to become an effective voice for parents and children, and so a legitimate and influential interlocutor in child care debates.

Evaluating child care: quality versus quantity measures

In Australia, child care centres provide a major part of the care given to young children. According to the child care survey undertaken in 2005 by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), centre-based long day care is the most commonly used type of formal child care among the 21 per cent of Australians aged twelve years and under attending formal child care in any given school week. Formal child care use has increased from 19 per cent in 2002 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, p. 3). According to 2007 figures, Australia has more than 8,500 child care services listed on the Australian Child Care Index and more than 10,000 child care services estimated across the country (The Australian Child Care Index 2007). It is therefore crucial that we understand how centre-based care can deliver positive outcomes for children and, by extension, for the broader community.

There is a growing body of research evidence indicating that positive outcomes for young children in centre-based care, particularly those from socially and economically disadvantaged backgrounds, are largely dependent on the quality of care provided (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network 2002; Sylva et al. 2003; Wylie 205et al. 2006). As a result, a significant body of research focuses on how quality child care can be evaluated (see Sakai et al. 2003 for an overview). Within the broad quality measures category there are two distinct but related concepts: structural quality and process quality.

Structural quality measures relate to the child care environment and include variables such as the child-staff ratio, environmental health and safety, classroom size, the average education level of the staff, and staff turnover. The concept of structural quality also includes measures more peripheral to the actual service experience, or at least the child’s experience of child care, such as location, affordability, and availability of child care services (Blau & Mocan 2002; Ghazvini & Mullis 2002; Helbum & Howes 1996).

Structural measures of quality are thought to be inputs to the production of ‘process quality’, which focuses on the nature of the interactions between the care provider and the child, and of the activities to which the child is exposed. Thus, process quality measures are those that relate directly to the nature of service provision and that affect the child’s experience of care. According to child development theorists, like Vygotsky and Bronnfenbrenner, the quality of these ‘process’ interactions within care drives child development. In a similar vein, Howes and colleagues (2008) point out that structural quality measures like the teacher-child ratio and teacher qualifications appear to have a negligible impact upon children’s developmental outcomes, whereas process quality is more strongly associated with children’s social and academic development (Howes et al. 2008).

The child care quality assurance regime in Australia

Research has clearly established that high quality, particularly process quality, is critically important for a range of positive outcomes in child care. Researchers have also developed robust means of measuring quality and proposed strategies for enhancing it. Despite these developments, Australia is yet to establish an effective quality 206assurance regime. One reason is that quality assurance measures have not been supported with government resources, as demonstrated by Australia’s low ranking in the OECD league table we mentioned in our introduction. In particular, the OECD draws attention to the lack of Australian research in early childhood education and reports that, although early childhood educational professionals implement innovative services, there are considerable gaps between research findings, existing service provision, and the policy directions of government (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2001; 2006).

As a consequence, Australia has a relatively under-developed and under-resourced quality assessment regime. Despite the fact that structural quality measures, like adult-child ratios, have been shown to be poorly predictive of positive outcomes in children (Howes et al. 2008), all the Australian state regulatory practices are based upon them. Further, state government licensing arrangements and the Child Care Quality Assurance (CCQA) framework of the federal government’s Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs rely heavily on self-regulation. They do not represent a consistently monitored and enforceable compliance regime, and tend to rely on spot checks and punitive measures rather than providing operators with incentives to aspire to clearly articulated quality standards. Nor are these regulatory frameworks well integrated. In Hill’s (2007) words, they are a ‘fragmented mess’. For example, centres can breach aspects of state licensing requirements but still operate and receive federal funding (Rush 2006).

Of particular relevance to this study is that current government controls over child care do not mandate regular and standardised reporting and thus fail to generate statistically reliable and verifiable data sets. In the absence of agreed, evidence-based, and transparent quality measures, and incentives to meet quality standards, parents’ interpretations of what constitutes ‘quality’ care are relatively more open to being shaped by a range of other influences. 207

Factors influencing parental decisions about child care

Meyers and Jordan argue that discrete choice events of parents are best understood within a social context, because perceptions are ‘developed through repeated interactions within a social environment’ (2006, p. 61). Other studies have understood child care choices as socially constrained and have identified factors influencing parental decisions around child care (Walzer 1997; Meyers & Jordan 2006; Vincent & Ball 2006; Cleveland & Krashinsky 2002). Within these broad framing ideas about decision-making, a range of material and interpretive factors that affect parents’ decisions have been identified by previous researchers.

For many parents cost can become an overriding concern when choosing child care. Some US econometric work finds that research about the influence of child care costs on employment decisions among all mothers underestimates the barriers that fees pose for low income mothers specifically (for a review, see Baum 2002, pp. 140–41). According to the ABS, the cost of child care rose 10 per cent in 2005 and 62 per cent in the four years to 2005 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006).

Access can also be an important factor. Gornick and Meyers (2003) compared child care in 14 industrialised countries and found that Australia rated relatively low on scales of availability and affordability for children aged less than three years, and in the middle for older preschool-aged children. These findings are contradicted by a recent Australian government Treasury report. According to this report ‘The available evidence indicates that in recent years, the supply of formal child care (which includes long day, family, after school and occasional care) has generally kept pace with demand’ (Davidoff 2007, p. 68), although the author also considered evidence on spatial variation in the supply of formal child care places (Davidoff 2007, pp. 72–73). According to the 2005 ABS child care survey, between June 2002 and June 2005 there was a decrease in the number of children for whom additional family day care was required (down 208from 29,100 to 17,700), and no significant change in demand for other types of formal care (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, p. 8).

Research has also found that interpretations of quality can be affected by a range of parent characteristics including education, race/ethnicity, and place of birth. Then there is the significant variation in individual beliefs and tastes. Further, social networks are a source of information for parents, providing normative cues for specific choices which can, over time, crystallise an option into a taken-for-granted pattern of action.

A range of external factors also affects parents’ choice sets and behaviour, from the influence of opinions of those in parents’ social circle, to the subliminal effects of marketing messages, to the appeal of the physical environment of centres or the way centre staff interact with parents. Meyers and Jordan (2006) describe these factors as decision-making shortcuts upon which parents rely when making their decisions relating to child care. They argue that these shortcuts assist parents to both simplify and rationalise their choices. According to Meyers and Jordan:

Parents’ assessment of the costs and benefits of alternative arrangements will reflect not only the observable features of care, such as price, but also the congruence of the arrangement with socially-constructed norms—from beliefs about gender roles to perceptions of quality in child care (Meyers & Jordan 2006, pp. 59–60).

Indeed, Sylva and colleagues argue that ‘quality is not a universal concept but depends on national curricula and cultural priorities’ (2003, p. 46).

Research has also found that the appeal of environmental factors in child care centres can shape parent choices. Mocan, who analyses data from a study of 400 centres across three US states, found that

parents are weakly rational … parents do not utilise all available information in forming their assessment of quality … 209There is some limited evidence for moral hazard as non-profit centres with very clean reception areas tend to produce lower level of quality for unobservable items (2007, p. 743).

Cleveland and Krashinsky (2005, p. 2) comment on the use of ‘superficial evidence’ of quality, such as new furnishings or staff uniforms, and observe that this may be the limit of owners’ investment in the absence of financial incentives for child care centres to further improve quality after accreditation has been achieved. In this context there is a clear incentive for centres to invest in attractive buildings and grounds over less observable aspects of quality.

Related to this, marketing messages also play a role in shaping parental choices. The marketing practices of child care providers with well-resourced infrastructure and sophisticated brand management techniques may, at least subliminally, conflate non-quality and quality measures. At worst these practices may promote quantity/market attributes as true signs of quality care that can either distract or in other ways convince parents of the superior quality of their service, without the added expense of having to make any substantial change in service practice.

For various reasons quality can also often be overestimated by parents. Cleveland and Krashinsky (2002) discuss how, in entrusting their small children to others, parents must then manage how they relate to those carers, who have considerable autonomy vis-à-vis their child. Some parents may feel that to question centre staff on the quality of their practice may have negative repercussions for the way those staff treat their child. Cleveland and Krashinsky also point out that in this context many parents convince themselves that they have acted in their child’s best interests, which in turn leads them to overestimate the quality of the long day care they select (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2002).

Some parents may not appreciate the importance of quality compared to other factors and ‘under-invest’ in care services. Blau and Mocan (2002), for example, argue that parents are relatively insensitive to quality differences in their selection of child care, based on estimates 210of the elasticity of their demand for structural quality features such as group size, adult-child ratios, and provider education. They conclude that, although parents appear willing to pay a little more for higher quality care, their demand for these quality features does not increase with a decrease in price or an increase in maternal wages, and increases only modestly with family income.

In summary, when conceptualising the complexity of decision-making around child care, it is fruitful to adopt a framework that places ‘choice’ in the context of financial, market, and social constraints. This approach draws on research in economics about the relationship between discrete choice and social interactions (for a review of this literature see Brock & Durlauf 2001). Pescosolido (1992) describes this approach as integrating assumptions about rational choice—including action and utility maximisation—with theories of bounded rationality and attention to the ‘the primacy of social interaction’ and ‘social structures as defining the bounds of the possible’ in individual decision making (p. 1098). We argue that, like social networks, a key shortcut to rationalising choice for parents is via the consumption of the mass media.

The role of the media in influencing parental understandings of quality child care

In addition to the factors outlined above, the media plays a crucial role in shaping parental perceptions of child care quality. This is because the media, through its interpretation of events, influences the way an issue is discussed and evaluated in the public arena. Social movement scholar, William Gamson, has stressed how discourse in the mass media reflects wider symbolic struggles over meaning and interpretation. Gamson argues that the mass media plays a central role in modern societies because it is the most generally available forum for debates on meaning and it is the major site in which contests over meaning must succeed. In other words, the mass media 211not only indicates but also influences cultural changes (Gamson 1988). By employing a particular discourse, the media can promote certain perspectives while silencing others.

Of course not all parents will be affected by media in the same way, and moderating variables such as gender and family environment are likely to be significant (Krippendorff 2004; Meyrowitz 1985; Malamuth & Impett 2001; Milkie 1994). Nevertheless, given the widespread influence of the media, it is important to be aware of media constructions of child care as a way of understanding both wider discourse and how the media or other groups may distort this discourse in ways that influence individuals’ perceptions of their own interests.

Based on our analysis of a sample of media content in Australia, we argue that dominant media constructions of child care centre not on ‘quality’ but on availability and affordability—on ‘who gets it’ and ‘how much it costs’. The potential effect is that parents will conflate market and quality-related child care measures in ways that give pre-eminence to market issues as a measure of the quality of child care. We therefore argue that we can examine public discourse, and by extension parental perceptions of quality, through the analysis of how child care issues are dealt with by the mass media.

Content analysis of media coverage of child care

To examine the content and themes of Australian media reports relating to child care we undertook a content analysis of individual newspaper reports produced in one newspaper over the course of one year. Each report was coded and classified according to a series of categories relating to child care issues, including categories addressing quality issues (both structural and process), and categories addressing other non-quality issues like the cost of care and access to care. 212

Method

Our study of media treatment of child care related stories is based on reports in New South Wales’ highest circulating broadsheet newspaper, The Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), over twelve months to September 2007, as identified by the media search engine Factiva™. We used a variety of search words in different combinations to cover a range of topics relating to child care. These included the terms ‘child care’; ‘child centre’, ‘long day care’, ‘child minding’, and ‘nursery school(s)’. Some 256 articles included the key word terms listed above. Articles were sorted according to relevance by Factiva, based on the number of key word occurrences in each article, and only the first 40 were assessed as having child care as the primary focus of the article. We subjected these articles to inductive content analysis to determine their content and orientation.

Analysis

Inductive coding and refining of codes was conducted by the authors and a group of research methodology students. Inter-coder reliability was examined and met minimum requirements; however, training strategies were developed to further improve inter-coder reliability.

We began by coding articles for surface content at the full article level, because we believed that surface coding was sufficient to extract primary content themes. The framework for analysis and coding sheets was designed around the following:

- The primary focus of the article—did the report focus on market issues, quality issues, or other? This used mutually exclusive coding and forced the coder to determine the dominant focus of the whole article.

- Coding for the article orientation—did the whole article focus predominantly on parent issues or child issues?

- Coding for the type of care discussed—did the article discuss 213ABC Learning Ltd,1 other corporate, government, non-government community, other, or all types? Multiple types of care could be coded for each article.

- More detailed coding on content topics—these codes detailed subcategories relating to the primary focus of the article. For example, quality issues could be coded as structural and/or process. A single article could be coded as addressing several content topics.

Results

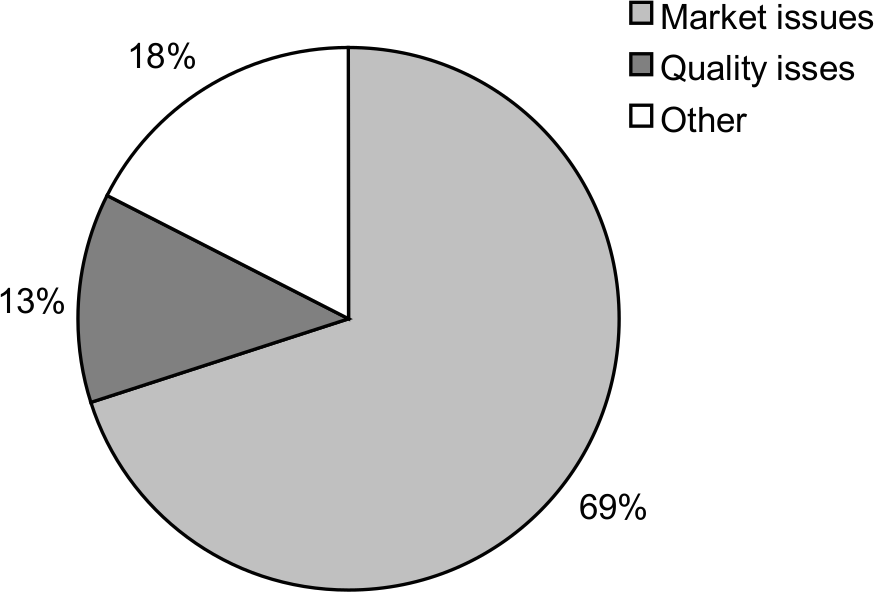

The primary focus of the SMH newspaper articles is reported in Figure 8.1, which clearly shows the dominance of market issues (including government subsidy arrangements, market demand, growth in the number of new centres, and market supply in general) in the paper’s coverage during the year to September 2007. Only 13 per cent of articles had child care quality as a dominant focus.

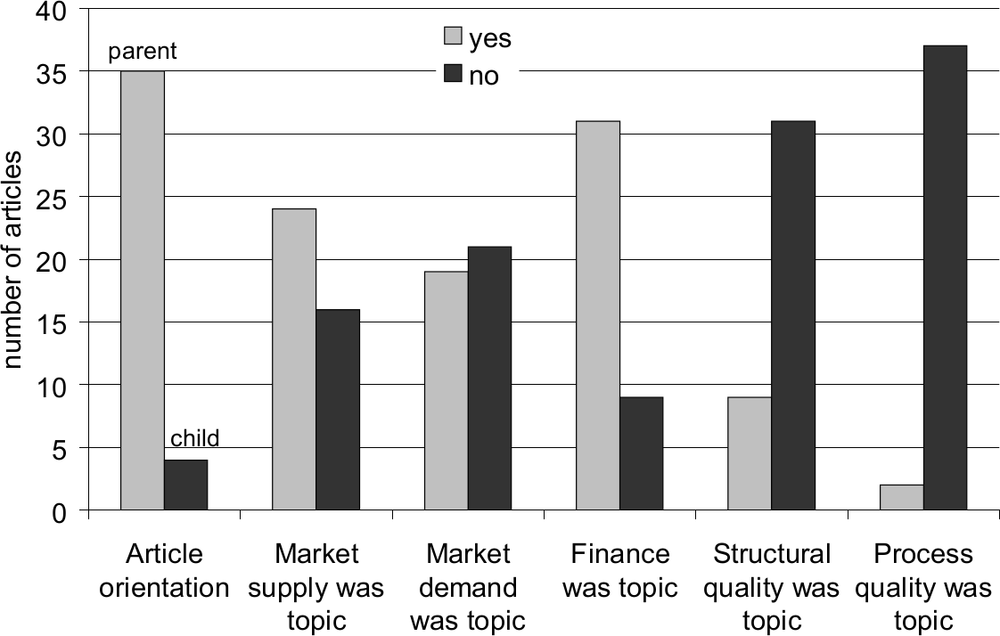

Figure 8.2 elaborates on the articles’ focus and shows topic subcategories by article orientation. The topic categorisations are not mutually exclusive and a single article can be coded as including several topics. It is apparent that the large majority of articles had a parent orientation and were concerned with issues that did not directly relate to children’s day-to-day experience in child care. Rather, the majority of articles commented on market issues relating to finance, supply and demand. Further analysis of articles showed that they focused on: finance and payment (100 per cent of market-focused articles addressed this), market demand (60 per cent), the opening/planning of new centres (55 per cent) and overall market growth (40 per cent).

214

Figure 8.1: Primary focus of SMH child care articles

Figure 8.2: SMH child care articles’ content and orientation

215A total of 13 per cent of articles addressed either structural or process quality issues. Of these articles, the majority focused on structural quality elements. Further subcategories for articles focusing on structural quality included: health and safety (100 per cent of quality-focused articles commented on this), staff qualifications and skills (50 per cent), adult-child ratios (25 per cent) and 25 per cent commented on market issues in addition to quality issues. Only two articles commented on process dimensions of quality like staff-child interaction, curriculum issues or learning opportunities.

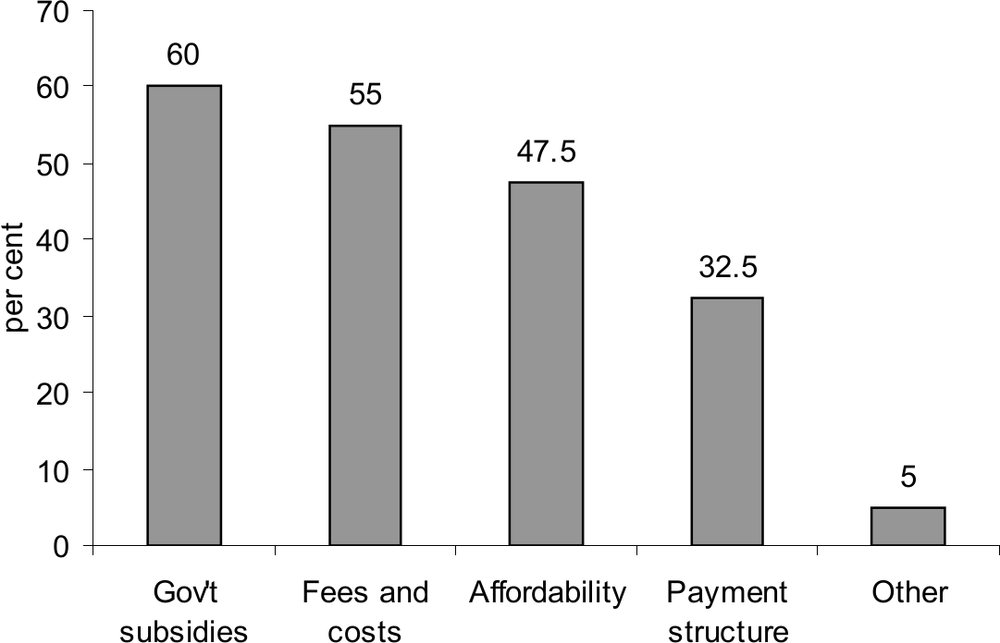

Finance issues (government subsidies, funds and costs, affordability, payment structure and options, other finance issues) were also coded in more detail as they became a strong emerging category and were analysed separately. Some 78 percent of articles commented on financial issues. Subcategories for these are shown in Figure 8.3. The dominant focus was on government subsidies, with substantial attention also paid to fee pricing, other child care costs and affordability.

Figure 8.3: SMH child care articles addressing finance topics

216As any individual article could cover several subcategories of topics, it is apparent that some reports focused on market issues also commented on quality issues and vice versa. Table 8.1 shows the percentage of articles addressing different topics under each primary focus. The most frequently addressed topics are, in order: government subsidies, child care fees and costs, affordability and access. Reporting on child care quality tended to focus on health and safety issues, which are addressed in 20 per cent of articles.

Table 8.1: SMH child care articles’ topics and subcategories

| Topic sub-categories | Count | % articles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market growth | 10 | 25 | |

| Market supply | New centres | 5 | 13 |

| Number of centres | 12 | 30 | |

| Market demand | Waiting lists | 6 | 15 |

| Access | 15 | 38 | |

| Child care costs | 22 | 55 | |

| Finance | Payment structure | 13 | 33 |

| Government subsidies | 24 | 60 | |

| Affordability | 19 | 48 | |

| Child/staff ratios | 3 | 8 | |

| Structural quality | Health & safety | 8 | 20 |

| Staff qualifications | 2 | 5 | |

| Staff skills | 2 | 5 | |

| Process quality | Staff/child interaction | 0 | 0 |

| Curricula | 1 | 3 | |

| Learning opportunities 217 | 2 | 5 |

Discussion of findings

Although this study is based on a limited sample, and further refinement of the content analysis coding procedures is possible with a larger selection of news reports, the set of SMH articles shows some interesting and robust trends. First, the reports are dominated by a focus on market issues and few articles focus on child care quality.

Second, and perhaps unsurprisingly, most articles focus on parents as customers and not on children’s experience of child care as consumers. Indeed, three out of four articles included comment on financial issues in child care. This imbalance may reflect—or indeed contribute to—the information asymmetry that parents experience in their quest to select and evaluate providers. If media reports do not highlight issues directly related to children’s day-to-day experience in child care, it seems unlikely that broad dimensions of child care quality will be scrutinised by either the wider public or, by extension, child care policy-makers.

Third, analysis of reports that do refer to child care quality, whether or not quality is the article’s primary focus, reveals that most refer to structural quality dimensions. The quality of a child’s experience and interaction—the ‘process’ quality which is most predictive of children’s education progress—is rarely addressed. Health and safety issues relating to physical environment and equipment are a more frequent topic. Although an important part of child care quality, and more readily assessed by parents choosing child care provision, health and safety and structural quality in general form only one dimension of quality. Studies outlined earlier have established the need for high quality care in a wide range of aspects and have shown how quality elements, including process quality, like the quality of child-adult interaction, are predictive of a child’s later developmental outcomes (Sylva et al. 2003).

The SMH content analysis provides evidence of media trends and reflects public discourse on child care. We conclude that this market dominated discourse, which neglects issues of quality, can serve to 218reinforce other messages about interpretations of quality in the public sphere. In particular it can reinforce the marketing messages of major corporate players, which make claims to quality but without actually having to invest seriously in quality improvements.

However, the public sphere is not just inhabited by the mass media nor dominated by the marketing messages of large companies. Ideas are expressed and contested in other important sites. In the case of parents forming judgements about child care, a key site is their own local child care centre. Among these centres, non-profit providers are particularly well-placed to play a significant role in influencing not only parental interpretations of quality but also potentially those of child care policy-makers.

Improving quality in Australian child care: the role of non-profit providers

In this section we examine the potential for non-profit providers of child care, not only to shape parental interpretations of quality, but also to garner widespread parental support to become key advocates for improvements to the current quality assurance regime. We argue that non-profits are well placed to realise this potential due to their position within the so-called third sector, their social mission, and their connections to local communities. However, to realise this potential, non-profit child care providers will need to re-examine their capacity to influence parent choices and behaviours and to act more broadly as advocates for the establishment of a more effective quality-assurance regime.

Many child care researchers have acknowledged the significance of activism, in particular feminist activism, where women’s organisations have participated in the construction of Australia’s welfare policies throughout the 20th century (Sawer & Groves 1994; Brennan 1998; O’Connor et al. 1999). More recently, researchers have begun to explore the role that parents, as consumers of child care 219services, can play in driving reform (Vincent & Ball 2006; Sumsion & Goodfellow 2009). These ‘parent power’ models represent an exciting and innovative approach to thinking about the politics of quality enhancement. We seek to build on the work of scholars such as Sumsion and Goodfellow and to link proposed parent-led quality improvements to the potential role and influence of non-profit child care providers as influential players in current child care debates.

The possibility that non-profit centres can readily transform parents into committed activists can seem somewhat remote. Like their decisions about child care, parents’ approaches to becoming involved in advocacy will be affected by a range of social interactions and constraints. A key finding of a study of parents and schools by Vincent and Martin (2002) was that ‘parental access to and deployment of a number of social resources significantly affected how often, how easily and over what range of issues they approached the school’ (p. 108). Schools have traditionally played a much more prominent role in involving and engaging parents.

However, there is scope for non-profit child care centres to further engage parents and mobilise their support. This is largely due to three characteristics non-profits can turn to their advantage, namely that they are legally constrained from distributing profits; that they outwardly endorse a social mission; and that they are embedded in local communities.

The first characteristic that distinguishes non-profit child care providers is that they are constrained from distributing profits and, as some economists have observed, without an apparent profit incentive to cut costs associated with quality, consumers are more likely to consider non-profit providers trustworthy when compared to for-profit providers (Hansmann 1987; Weisbrod 1978; 1988; 1989; Rose-Ackerman 1996). According to Hansmann’s ‘contract failure’ hypothesis, purchasers prefer non-profit service providers over for-profit counterparts in industries where there are high levels of information asymmetry. Hansmann (1980) argues that: 220

The nonprofit producer, like its for-profit counterpart, has the capacity to raise prices and cut quality in such cases [of informational asymmetries] without much fear of customer reprisal; however, it lacks the incentive to do so because those in charge are barred from taking home any resulting profits. In other words, the advantage of a nonprofit producer is that the discipline of the market is supplemented by the additional protection given the consumer by another, broader “contract”, the organization’s legal commitment to devote its entire earning to the production of services (Hansmann 1980, p. 844).

Trust in for-profits can grow if regulation becomes accepted as an adequate means to police producers. In Australia, though, in the absence of a well-functioning quality-assurance regime, non-profit providers may be able to capitalise on this tendency to be considered relatively trustworthy, or at least as less untrustworthy, translating this into relatively greater influence over parent perceptions of, and choice sets in, child care.

A second advantage of non-profit providers relates to their position within the third sector. A wide range of literature has highlighted how third sector organisations (TSOs) can act as vehicles for collective interests and drive social and economic change (Almond & Verba 1989; Lipset 1956; Hall 1995; Keane 1998; Tarrow 1994). One reason is that TSOs have a social mission. Evidence suggests that groups driven by altruistic or idealistic factors can motivate people to commit themselves to founding, funding, and striving to advance the goals of non-profit organisations (DiMaggio & Anheier 1990; Lyons 2001).

Third, non-profit child care centres are embedded within a community. With a grassroots constituency comes a mandate and legitimacy to seek to influence policy. The key is to develop the commitment and activist orientation of that grassroots constituency, and then the leadership to communicate the depth of the organisation’s 221support to decision-makers. That parents and centres are in regular contact and usually live locally are advantages supporting grassroots mobilisation.

Non-profit child care centres, then, can serve as a crucial context for the dissemination of political messages to parents and a place where parents are exposed to opportunities for involvement in advocacy to change policy. Whether they realise this political role depends on whether non-profits themselves have the will and capacity to engage in effective advocacy campaigns.

From service providers to advocates? Strategies for making an impact

Despite their potential advocacy role, to date the success of non-profit child care led campaigns has been mixed. However this patchy performance is not necessarily due to deficiencies of non-profits. It may also be due in part to distortions arising from the differential lobbying strengths of non-profit and for-profit providers. There is already some evidence of privileged access for some providers to politicians and policy-makers. Brennan and colleagues have reported that: ‘From the start, ABC Learning has been closely associated with influential Liberal party figures’ (2007, p. 6). They note how ABC Learning’s board of directors included the former Federal Minister for Children and Youth Affairs, Larry Anthony. Some have argued that this, and other connections and party donations, have influenced the size and flow of government subsidies (Birnbauer 2006).

So how can non-profits address this power differential between themselves and for-profits, and realise their potential as activists for quality improvements? We conclude by briefly discussing some strategies for developing non-profit child care centres’ strategic communication skills. 222

Strategic communication

It is important that non-profits understand the meanings and contestation that surround child care discourse in Australia if they are to respond effectively. They must understand the cultural settings within which they act, the institutional and discursive terrain, and use this understanding to inform their arguments and choice of political strategies. This depends on successfully refocusing/reframing debate to centre on quality by linking interpretations of quality to pre-existing norms and beliefs within society. This refocusing or reframing, in turn, involves strategic use of the media. Non-profits can conduct or sponsor research and then disseminate findings via the media—for example findings from early childhood research, risk assessment analyses, and industry quality audits. Other marketing and communication exercises can also send a message, from advertising campaigns through to public engagement activities. The ‘Parent Voices’ initiative sponsored by the Child Care Advocacy Association of Canada (2003) has some straightforward tips, such as ‘finding statistics and articles on request, providing ways to share community-based campaign strategies, helping with local information flyers and linking different parent groups with one another’.

Critical to success is finding the resources necessary to support this communication-based strategy. This is a major challenge for busy child care centres reliant on limited income from fees. One option is considering founding centre-based fighting funds—perhaps raised from levies or contributions drawn from parents—a fund modelled on that raised by some unions and clubs. Introducing membership dues could also provide another source of untied funds. Non-profits are also well placed to access the legal, financial and public relations expertise (for example) needed for a campaign, by drawing on board members or parents.

Realising advocacy potential effectively also depends on child care centres adopting a more politicised culture. But for some centres 223assuming this role will require some internal cultural readjustment. To date most non-profits have seen themselves as service providers. Reassessment of their role as advocates and not just service providers will involve a deeper appreciation and internal acceptance of themselves as legitimate actors in the political process, and a change in organisational culture where advocacy is considered core business.

Conclusion

We have attempted to provide insight into what the community, and parents in particular, understand to be ‘good’ child care and use this to inform a non-profit advocacy strategy to refocus public debate on child care quality. Our understanding of community perceptions is based on media analysis, which found that market/quantity issues (including government subsidy arrangements, market demand, growth in the number of new centres and market supply in general) appear most frequently in reports about child care. We also found that the majority of articles concentrated on issues relating to parents as customers and not on issues directly related to children’s experience of child care, particularly those articles that comment on financial issues in child care. Finally, our analysis of the small proportion of articles that do comment on child care quality, whether this formed the article’s primary focus or not, revealed that most referred to structural quality dimensions like health and safety of equipment and adult-child ratios.

We argue that these dominant media constructions of child care resonate with the fears and aspirations of parents—with the effect that they have shaped parental perceptions and given pre-eminence to market issues as a measure of quality in child care. We conclude that media constructions distract parents’ attention away from the important ‘process’ dimensions of child care quality that better reflect the child’s experience and have been shown to predict child outcomes. 224

In furthering the goal of establishing a more effective quality regime, we have also discussed the role that non-profit providers could play in driving policy change to address—and effectively regulate—child care quality, with a greater focus on the ‘process’ quality aspects, which research has identified as so important. We have noted how several economists argue that consumers, are likely to consider non-profit providers as more trustworthy than for-profit providers due to their non-distribution constraint. We have also referred to other political and social theory that emphasises non-profits’ roles as vehicles for social and political change. Given their unique characteristics, non-profit providers are well placed to garner widespread support and drive the future child care agenda. But, given the power of self-limiting beliefs, an identity shift from service provider to advocate could be difficult to achieve. Any such changes need to be supported with continuing efforts directed at non-profit advocacy capacity-building.

Without a sustained and well-planned advocacy campaign, non-profits will not effectively engage with dominant constructions of child care quality, and so will fail to place quality of service on the political agenda. In the absence of such efforts, it is likely that corporatisation of the sector will increase, as rising fees and government payments will make for-profits’ forays into this market more lucrative. The potential costs of this scenario, where important dimensions of child care quality continue to be neglected, is difficult to overestimate. At best it means the opportunity to maximise the nurturing of our future generations is lost. At worst it may mean we subject our children to sub-optimal and potentially damaging care. Given the high stakes, it is critical that non-profits highlight these issues in a new public discourse on child care quality. 225

References

Almond, G. & Verba, S. 1989, The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations, Sage Publications, Newbury Park.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Child Care Australia, June 2005, Cat. No. 4402.0, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

Australian Government 2004, More Help For Families, 2004–05 Budget—Overview, AGPS, Canberra.

Barnett, W. S. & Ackerman, D. J. 2006, ‘Costs, benefits, and the long-term effects of preschool programs’, Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 86–100.

Baum, C. 2002, ‘A dynamic analysis of the effect of child care costs on the work decisions of low-income mothers with infants’, Demography, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 139–64.

Birnbauer, W. 2006, ‘Simple as ABC: Minister, you help us, we’ll help you’, Sunday Age, 6 August.

Blau, D. M. & Mocan, H. N. 2002, ‘The supply of quality in child care centers’, Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 84, no. 3, pp. 483–96.

Brennan, D. 1998, The Politics of Australian Child Care: Philanthropy, Feminism and Beyond, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Brennan, D., Newberry, S. & van der Laan, S. 2007, The corporatisation of Australian child care: As easy as ABC, paper presented at Symposium on For-Profit Providers of Paid Care, University of Sydney, Sydney, 29–30 November.

Brock, W. A. & Durlauf, S. N. 2001, ‘Discrete choice with social interactions, The Review of Economic Studies, vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 235–60.

Child Care Advocacy Association of Canada 2003, Parent Voices Resource Kit [Online], Accessed at: http://www.ccaac.ca/parent_voices/content/EN/pdf/pv_reskit_pt4.pdf [2008, Mar].

Cleveland, G. & Krashinsky, M. 2002, ‘Financing ECEC services in OECD Countries’, OECD Occasional Papers [Online], Available: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/55/59/28123665.pdf#search=%22Financing%20ECEC%2services%20in%20OECD%20Countries%22 [2007, Nov 25]. 226

Cleveland, G. & Krashinsky, M. 2004, ‘The quality gap: A study of nonprofit and commercial child care centres in Canada’, [Online] Available: http://childcarepolicy.net/pdf/NonprofitPaper.pdf [2008, Mar 22].

Cleveland, G. & Krashinsky, M. 2005, The nonprofit advantage: Producing quality in thick and thin child care markets, Department of Management, University of Toronto at Scarborough [Online], Available: http://childcarepolicy.net/pdf/non-profitadvantage.pdf [2008, Mar 22].

Davidoff, I. 2007, ‘Evidence on the child care market’, Economic Roundup Summer 2007, Department of Treasury, Canberra [Online], Available: http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/1221/PDF/04_child_care.pdf. [2007, Nov 15].

DiMaggio, P. J. & Anheier, H. K. 1990, ‘The sociology of nonprofit organizations and sectors’, Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 16, pp. 137–59.

Gamson, W. 1988, ‘Political discourse and collective action’, in From Structure to Action: Comparing Movement Participation Across Cultures—International Social Movement Research, vol. 1, eds B. Klandermans, H. Kriesei, & S. Tarrow, JAI Press, Greenwich, Conn., pp. 219–47.

Ghazvini, A. & Mullis, R. 2002, ‘Center-based care for young children: Examining predictors of quality’, Journal of Genetic Psychology, vol. 163, no. 1, pp. 112–25.

Gornick, J. & Meyers, M. 2003, Families That Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment, Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

Hall, J. (ed.) 1995, Civil Society: Theory, History, and Comparison, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Hansmann, H. B. 1980, ‘The role of nonprofit enterprise’, Yale Law Journal, vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 835–902.

Hansmann, H. B 1987, ‘Economic theories of nonprofit organization’, in The Nonprofit Handbook, ed. W. W. Powell, Yale University Press, New Haven, pp. 27–42.

Helburn, S. W. & Howes, C. 1996, ‘Child care cost and quality’, The Future of Children: Financing Child Care, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 62–82. 227

Hill, E. 2007, ‘Making child care count is not just about cost’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 November.

Hill, E., Pocock, B. & Elliott, A. (eds) 2007, Kids Count: Better Early Childhood Education and Care in Australia, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Pianta, R., Bryant, D., Early, D., Clifford, R. & Barabin, O. 2008, ‘Ready to learn? Children’s pre-academic achievement in pre-Kindergarten programs’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 27–50.

Keane, J. 1998, Civil Society: Old Images, New Visions, Stanford University Press, Stanford.

Krippendorff, K. 2004, Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd edition, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Lipset, S. M. 1956, Union Democracy, Anchor Books, Garden City.

Lyons, M. 2001, Third Sector: The Contribution of Nonprofit and Cooperative Enterprises in Australia, Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

Malamuth, N. & Impett, E. 2001, ‘Research on sex in the media: What do we know about effects on children and adolescents?’ in Handbook of Children and the Media, eds D. Singer & J. Singer, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 289–307.

Meyrowitz, J. 1985, No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior, Oxford University Press, New York.

Meyers, M. & Jordan, L. 2006, ‘Choice and accommodation in parental child care decisions’, Community Development: Journal of the Community Development Society, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 53–70.

Milkie, M. A. 1994, ‘Social world approach to cultural studies: Mass media and gender in the adolescent peer group’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 354–80.

Mocan, H. N. 2007, ‘Can consumers detect lemons? Information asymmetry in the market for child care’, Journal of Population Economics, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 743–80.

Mósesdóttir, L. 1999, ‘Breaking the boundaries: Women’s encounter with the state’, in Working Europe: Reshaping European Employment Systems, ed J. Christensen, P. Koistinen & A. Kovalainen, Ashgate, London, pp. 97–135. 228

National Institute of Child Health and Development Early Child Care Research Network 1999, ’Child care in the first year of life’, Merrill Palmer Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 340–60.

National Institute of Child Health and Development Early Child Care Research Network 2002, ‘Early child care and children’s development prior to school entry: Results from the NICHD study of early child care’, American Educational Research Journal, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 133–64.

O’Connor, J., Orloff, A & Shaver, S. 1999. States, Markets, Families: Gender, Liberalism and Social Policy in Australia, Canada, Great Britain and the United States, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2001, OECD Country Note: Early Childhood Education and Care Policy in Australia, OECD, Paris.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2006, Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care, OECD, Paris.

Pescosolido, B. M. 1992, ‘Beyond rational choice: The social dynamics of how people seek help,’ American Journal of Sociology, vol. 97, no. 4, pp. 1096–138.

Press, F. & Woodrow, C. 2009, ‘The giant in the playground: Investigating the reach and implications of the corporatisation of childcare provision’, in Paid Care in Australia: Politics, Profits, Practices, eds D. King & G. Meagher, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Radich, J. 2002, Confronting the realities—What next for the quality improvement and accreditation system? Contribution to the environmental scan undertaken by the National Childcare Accreditation Council to support its future strategic planning, September. [Online], Available: http://www.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/early_childhood_news/speeches/confronting_the_realities_what_next_for_the_quality_improvement_and_accreditation_system_sep_2002.html [2007, Nov 15].

Rose-Ackerman, S. 1996, ‘Altruism, nonprofits, and economic theory’, Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 701–28.

Rush, E. 2006, Child care quality in Australia, Discussion Paper No. 84, The Australia Institute, Canberra [Online], Available: http://www.tai.org.au/documents/downloads/DP84.pdf [2007, Nov 15]. 229

Sakai, L., Whitebrook, M., Wishard, A. & Hoews, C. 2003, ‘Evaluating the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale (ECERS): Assessing differences between the first and revised edition’ Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 427–45.

Sawer, M. & Groves, A. 1994, ‘The women’s lobby: Networks, coalition building and the women of middle Australia’, Australian Journal of Political Science, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 434–59.

Sumsion, J. & Goodfellow 2009, ‘Parents as consumers of early childhood education and care: The feasibility of demand-led improvements to quality’, in Paid Care in Australia: Politics, Profits, Practices, eds D. King & G. Meagher, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Simmons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, L., Taggart, B. & Elliot, K. 2003, The Effective Provision of Pre-School Education (EPPE) Project: Findings from the pre-school period, summary of findings [Online], Available: http://www.ioe.ac.uk/schools/ecpe/eppe/eppe/eppefindings.htm [2006, Oct 10].

Schweinhart, L., Barnes, H. V. & Weikart, D. P. 1993, Significant Benefits: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study through Age 27, High/Scope Press, Ypsilanti MI.

Tarrow, S. 1994, Power in Movement, Cambridge University Press, New York.

The Australian Child Care Index 2007, [Online], Available: http://www.echildcare.com.au/about/ [2007, Nov 22].

The University of Sydney 2007, ‘Children suffer when politicians put profit and populist policies first’, Media release, 12 November [Online], Available: http://www.sup.usyd.edu.au/MediaReleaseKidsCount12nov07.pdf [2008, Jul 10].

Vandell, D, Henderson, V. & Wilson, K. 1988, ‘A longitudinal study of children with day-care experiences of varying quality’, Child Development, vol. 59, no. 5, pp. 1286–92.

Vincent, C. & Ball, S. 2006, Childcare, Choice and Class Practices: Middle-class Parents and Their Children, Routledge, London.

Vincent, C. & Martin, J. 2002, ‘Class, culture and agency: Researching parental voice’, Discourse, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 109–28. 230

Walzer, S. 1997, ‘Contextualizing the employment decisions of new mothers’, Qualitative Sociology, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 211–27.

Weisbrod, B. 1978, ‘Problems of enhancing the public interest: Toward a model of government failures’, in Public Interest Law, eds B. Weisbrod, J. Handler & N. Komesar, California University Press, London, pp. 30–41.

Weisbrod, B. 1988, The Nonprofit Economy, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

Weisbrod, B. A. 1989, ‘Rewarding performance that is hard to measure: the private nonprofit sector’, Science, vol. 244, no. 4904, pp. 541–46.

Wylie, C., Hogden, E., Ferral, H. & Thompson, J. 2006, Contributions of early childhood education to age-14 performance: Evidence from the longitudinal competent children, competent learners study [Online], Available: http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/7716/cc-contributions-ece14.pdf [2006, Apr 1].

1 ABC Learning Ltd is a large corporate child care provider. For more information about its role and actions see Brennan and colleagues (2007) and Press and Woodrow (2009).