7

Parents as consumers of early childhood education and care: the feasibility of demand-led improvements to quality

The quality of early childhood education and care (ECEC) is important for children, their parents and society more broadly. Positive outcomes for children in centre-based ECEC, particularly those from socially and economically disadvantaged backgrounds, are largely dependent on centre quality (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network 2002; Sylva et al. 2003). Parents’ decisions about labour force participation are influenced by the quality of available care, and this is especially the case for mothers (Duncan et al. 2004; Hand 2005). Moreover, high quality ECEC contributes to the development of social capital by enhancing family and community networks (Press 2006).

Yet, in Australia, over the last decade and a half, the policy emphasis on ECEC, particularly long day care, as a competitive service best provided by the market (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2006), has led to a greater focus on availability rather than sustained attention to quality. With the notable exception of the introduction of a national accreditation system for long day care centres in 1994, quality, for the most part, has been framed as a natural outcome of the efficient operation of market forces. Faith in market rationality as a basis for quality ECEC provision is, at best, naïve given well-rehearsed arguments concerning the market’s limitations in providing universally high quality ECEC (see, for example, Cleveland & Krashinsky 2002; Folbre 2006; Helburn & Howes 1996). 168

Since its election in November 2007, the Rudd Labor Government has consistently reiterated its commitment to the provision of high quality ECEC (Gillard 2008a). At the same time, it has indicated that market competition will continue to play an important role in ECEC policy, while foreshadowing the possible introduction of strategies to deter ‘unfair profiteering’ by for-profit providers (Gillard 2008b). To what extent and in what ways market forces will play out under the Rudd Government remains unclear. This chapter is premised on the assumption, however, that market forces will continue to play a significant role in Australian ECEC policy and provision. Accordingly, we appropriate the market discourses of supply and demand as a framework for analysis and speculation.

The intent of the chapter is to canvass the feasibility of parents, as consumers of ECEC services, driving demand-led improvements to quality. Our investigation is conceptual and tentative, rather than empirical and conclusive, and focuses primarily on parent knowledge, agency and motives, as well as power relations between parents, service providers and government. In using the term ‘parents’ instead of ‘family’, our intent is not to exclude families with diverse structures and caring arrangements, but rather to remain consistent with the terminology used in much of the literature and most of the websites upon which we have drawn. The chapter consists of two main sections. In the first section, we briefly discuss the constructs of market rationality, market imperfections and intervention mechanisms as they apply to the Australian market-oriented system of ECEC provision, in part to identify challenges Australian parents may face as consumers of ECEC services. In the second and larger section, we draw on research focusing on parents as ECEC consumers, and on websites aimed at assisting them to make informed choices, to develop a preliminary typology of perspectives on parents as ECEC consumers. We see the typology as a tool for differentiating ways in which parents are positioned as consumers and for considering possible consequences of these positionings. We also envisage that it may provide a useful springboard for subsequent empirical 169investigations of parent capacity to drive demand-led improvements to ECEC quality.

Market rationality, imperfections and intervention mechanisms

Proponents of competition argue that it leads to high quality and cost-efficient ECEC because, in theory, ‘parents can shop around’ and punish providers that do not deliver high-quality services at a competitive price by taking their children elsewhere (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2002, p. 39). Moreover, in a rational market that operates according to the laws of supply and demand, ECEC providers are assumed to have inbuilt incentives to continually monitor quality and efficiency, or risk financial collapse. Government intervention, market proponents argue, can be justified only when the market fails to function as it should. Yet in the Australian ECEC market, where market malfunctions and imperfections abound, intervention mechanisms designed to address the consequent imbalances of demand and supply have been of questionable effectiveness. In a context such as this, there are substantial barriers to parent-led demand for quality improvement. We highlight these below.

We focus first on barriers related to demand-side imperfections (associated with consumer demand for ECEC) and second, on supply-side imperfections (associated with the provision of ECEC). We then outline limitations of current market interventions designed to counter the negative effects of these imperfections. In doing so, we foreshadow three dimensions for conceptualising parents’ capacity to bring about demand-led improvements to quality. These dimensions relate to how knowledgeable and perceptive (or informed and discerning) parents might be about quality; their focus on, and/or motivations for, improving quality; and the agency or power they are able to bring to their efforts to realise their goals in relation to quality. 170

Demand- and supply-side imperfections

Demand-side imperfections arise when consumers have difficulty judging and monitoring the quality of what they are purchasing (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2002; Helburn & Howes 1996; Stanley et al. 2006), perhaps because they are uninformed or undiscerning about the product or service. Conversely, they may be quite knowledgeable and discerning about the quality of the product or service but, for a variety of reasons, not in a position to act on that knowledge. Parents can find it difficult to evaluate the quality of long day care centres for a range of well-documented reasons (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2002; Meyers & Jordan 2006). In brief, they may not have purchased long day care before and may not be knowledgeable about what constitutes high quality. By the time they become experienced—and possibly more informed and discerning—consumers of long day care, their children are likely to be beyond the age where they require care, thus making it difficult to put their experience to good use. Because parents generally spend relatively little time in centres and because many aspects of quality provision are not readily observable, parents who are informed and discerning consumers may still struggle to monitor quality on an ongoing basis. A further complication is that parents are not direct consumers; they purchase long day care on behalf of their children, who are likely to ‘have difficulty evaluating the quality of what they are consuming and communicating that evaluation’ to their parents (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2005, p. 4). Moreover, the quality of a centre can also be unstable, and may vary markedly with staff turnover and even from day to day, with events on one day not necessarily indicative of those on other days.

The difficulties of evaluating and monitoring quality can be compounded by the emotional nature of the long day care transaction for many parents. Gendered social expectations about parenthood and paid employment, competing family and work demands, and concern for their children’s wellbeing can create an array of antipathies and tensions for parents that can further ‘distort’ their consumer 171decisions (Vincent & Ball 2006). For example, in convincing themselves that they have acted in their child’s best interests, parents may overestimate the quality of the long day care they purchase. Or having settled their child into a centre and formed relationships with staff, they may be reluctant to face the upheaval of moving to a different centre in search of higher quality, if indeed a place were available elsewhere. They might also refrain from raising concerns about quality because of fears that they or their child may be marginalised by centre staff (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2002).

Even in those arguably rare circumstances where parents are able to evaluate and monitor quality, choose their provider, and make decisions unencumbered by emotional constraints, quality may not be their overriding criterion. Given the high relative cost of child care, parents may opt for a lower quality, lower cost centre in preference to one of higher quality and higher cost, for even low or mediocre quality long day care has high utility value to parents if it permits them to work (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2005). Moreover, lack of awareness by many parents of the long-term benefits of high quality long day care (Sylva et al. 2003) may lead them to underestimate the importance of quality, and thus to ‘under-invest’ in quality in their purchasing decisions (Stanley et al. 2006, p. 27). The effect can be to perpetuate and exacerbate market imperfections.

Demand-side imperfections in the ECEC market such as those outlined above are compounded by supply-side imperfections. Despite growing pockets of oversupply, the overall shortfall of long day care places in Australia, in conjunction with significant levels of market concentration achieved by former corporate giant ABC Learning (see Press & Woodrow 2009) puts providers in a more powerful position than consumers, particularly in locations where parents, in effect, have no real choice of service. Even where parents have choices, supply-side imperfections are endemic. Currently, in Australia, for example, providers have no financial incentive to further improve quality after accreditation has been achieved. Opportunistic providers, therefore, may have an incentive to provide 172‘superficial evidence’ of quality, such as new furnishings or staff uniforms, while engaging in practices that undermine it (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2005, p. 2). They may be able to cut costs, for instance, through dubious staffing practices and hence under-price, and eventually drive out of business, more principled providers that have a stronger commitment to quality.

Additional supply-side imperfections are created by the absence of safeguards against distortions arising from the differential lobbying strengths of providers; hence the possibility of privileged access for some providers to politicians and policy-makers. During the incumbency of the Howard Government (1996–2007), for example, the appointment by ABC Learning of a former Howard Government minister to its board of directors shortly after his 2004 electoral loss highlighted the potential for privileged access, given that the Minister, while in office, had responsibility for child care and the administration of the Child Care Benefit, which, at the time, constituted approximately 50 per cent of ABC Learning’s income (Jokovich 2005). Documents obtained under freedom of information laws revealed that the same former minister met with senior government officials to discuss child care provision less than eight weeks after taking up his directorship with ABC Learning (Walsh 2006). Brennan (2007) documents several other similarly close links between former Liberal and National Party ministers and ABC Learning. It is not our intent to tie the likelihood of events such as these to any particular government. Rather, we suggest that they may well be symptomatic of corporatised provision and of the powerful vested interests that parents may face in any attempt to lobby for changes in ECEC policy directions that, for example, might include a greater focus on non-profit provision as a community and broader social good.

Demand- and supply-side intervention mechanisms

In attempting to address the demand- and supply-side imperfections described above, the Hawke-Keating (1983–1996) and the Howard 173(1996-2007) governments implemented a range of measures. Individually and collectively, these measures have been less than optimally effective in countering distortions in the ECEC market. Demand-side interventions include the Child Care Benefit fee subsidy, a progressive benefit that favours low-income families, and the Child Care Tax Rebate, a regressive benefit favouring high-income families (Brennan 2007). Given the tendency for some providers to increase their fees in line with increases in the Child Care Benefit and the Child Care Tax rebate (Mayne 2008), these interventions appear unlikely to allow parents the scope for nuanced consumer decisions of the kind presumably required to support demand-led improvements to quality. Less direct demand-side interventions include government-funded parent education initiatives to improve parent knowledge about quality long day care and to inform decisions concerning parents’ choice of service.1 The potential effectiveness of such initiatives is discussed later in the chapter.

Perhaps the most significant supply-side intervention with respect to quality has been the establishment in 1994 of the national accreditation system administered by the National Childcare Accreditation Council (NCAC) to complement state-based licensing regulations. This two-tiered regulatory framework is tied to government funding, and as Brennan (2007) points out, has been widely credited with guaranteeing an acceptable level of quality. Yet very few centres that seek accreditation fail to gain it. An analysis of the NCAC’s Quality Trends reports for long day care services for the three years from July 2004–July 2007 indicates that the failure rate averaged less than 5 per cent (National Childcare Accreditation Council 2008). Anecdotal evidence suggests similarly low failure rates for state-based licensing. The consistently and implausibly low failure rate has attracted considerable scepticism about the rigour of accreditation and licensing processes (Pryor 2006), and contrary to original intentions, so far appears to have offered limited traction for demand-led

174improvements to quality. The Rudd Government’s initial plans were to replace the satisfactory/unsatisfactory rating currently used in the NCAC’s accreditation process with a five-point rating scale (ranging from A for ‘excellence’ to E for ‘unsatisfactory’) (Gillard 2008a). These plans have since been shelved, but the proposed five-point scale may have enhanced parent’s knowledge of centre quality and thus assisted parent-led demand for quality improvement.

Other supply-side interventions introduced by the former Howard Government included the implementation of several targeted policy initiatives2 aimed at extending long day care provision for communities with high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage that are unlikely to attract for-profit providers. While each initiative targets different kinds of programs and organisational structures, they all reflect a focus on addressing disadvantage and facilitating community capacity building. Whether parents in the communities served by these initiatives have sufficient cultural and political capital to drive demands for improved quality is, as yet, for the most part unknown.

Apart from some tightening of the national accreditation system, the Howard Government appeared to have no plans to retreat from its strong market orientation. Prior to its electoral defeat it had ruled out further supply-side interventions, such as re-introducing operational funding for services, investing in publicly-funded long day care infrastructure, regulating ownership of long day care centres, engaging in service provision planning, or reducing the funding that goes directly to parents, despite well-reasoned arguments (for example, Cox 2007) in favour of such measures. In contrast, the Rudd Government’s plans to boost the ECEC workforce by creating additional university places in early childhood teacher education programs and abolishing fees for diploma-level ECEC, and to increase available long day care places by establishing 260 additional ECEC centres (Gillard 2008a) suggest that it intends to make more use than the

175previous government of supply-side interventions. The implementation of these plans, and particularly decisions about whether the 260 new centres, to be located on school sites and community land, will operate on a non-profit basis, will provide insight into whether new possibilities are likely to emerge for demand-led improvements to quality, despite the continuing presence of demand- and supply-side imperfections outlined in this section.

The feasibility of demand-led improvements to quality

Among researchers and policy analysts, there is little consensus about the feasibility of demand-led improvements to quality. In their analysis of the impact of privatisation and corporatisation in Australian ECEC provision, Press and Woodrow (2005) conclude that consumers are unlikely to manage to ‘exert an upward pressure’ on the quality of child care provided by market forces, because of ‘the complex interplay of factors associated with availability, affordability, quality and the imperfect information upon which parents base their decisions’ (p. 282). In the United States of America, Emlen (1998) is considerably more optimistic. He contends that debates about how to achieve consistently high-quality child care have been limited by their bias towards improving supply-side interventions. Possibilities for addressing quality through improving demand-side factors, he argues, have been either prematurely overlooked or dismissed.

Canadian researchers Cleveland and Krashinsky (2005) are more circumspect than either Press and Woodrow (2005) or Emlen (1998). They differentiate between ‘thick’ markets with many potential long day care consumers, including those in middle- and higher-income levels; and ‘thin’ markets with relatively few potential consumers and a higher proportion of lower-income families.3 Demand-led

176improvements to quality are more feasible in thick markets, they argue, because higher-income consumers are more able and likely than lower-income consumers to demand and obtain quality care. They leave unanswered, however, some key questions. For example, do consumers in thick markets who are relatively well-placed to use their consumer power to demand quality long day care, seek the kind of child care that is commensurate with experts’ views of quality? Do they tend to act primarily on the basis of self-interest; and if they do, does their self-interest serve to improve quality across the board to the benefit of the community and of the wider society?

In the remainder of this section, we draw eclectically from research in early childhood education, social policy, educational policy, and feminist economics, as well as parent information and related websites, to develop a conceptual typology of five perspectives on the possibilities of parent-led demands for improved quality in ECEC. Our intent is to identify possible associations between ways in which parents as ECEC consumers are positioned in the literature and the feasibility of demand-led improvements to quality. Before proceeding, however, we outline the processes used to develop the typology.

Developing the typology: an explanatory note

We began by examining a collection of early childhood education research studies reporting on parents’ reasons for choosing child care, their perspectives/views on child care, their perceptions of child care quality, and/or their experiences of/satisfaction with child care. Reports of these studies were sourced from four peer-reviewed journals4 that have a wide readership amongst early childhood education researchers (from issues published between 1997 and 2007). From the references cited in the articles sourced through these journals

177we located a further four relevant studies, making a total of thirteen studies. We then turned to parent education materials, identified by the Google search engine, from Australian websites providing advice to parents on ‘choosing long day care centres’. Ten relevant and reputable websites were identified. In addition, we referred to publicly available online summary reports of high-profile studies5 of the quality and impact of ECEC likely to be of interest to parents seeking research-based information about ECEC. An analysis of Australia’s National Childcare Accreditation Council’s child care quality assurance system as an example of service user evaluation followed.

Next, we considered recent critiques and empirical studies of ECEC consumer-provider dynamics in market-oriented contexts, taken from early childhood and/or educational research publications identified through our working knowledge of the literature. The critical perspectives underpinning this body of research distinguish this category from the first group of early childhood education research studies outlined above. Finally, we drew on a small sample of research on active citizenship and participatory democracy. Central to this work was an understanding of ‘consumer’ as a politicised concept that ‘may be appropriated at different times for particular purposes’ (Henderson & Petersen 2002, p. 5), rather than one with either inherently positive or negative connotations that cause it to ‘be either welcomed or resisted depending on one’s political persuasion or professional view’ (Newman & Vidler 2006, p. 207).

Following processes outlined by Ozga (2000), we inductively analysed the different bodies of literature and web-based materials outlined above to ascertain the language, categories and themes used to construct and position parents as consumers. We also identified emphases, silences and visions of what might be possible concerning parent-led demands for improved quality. From this analysis, we

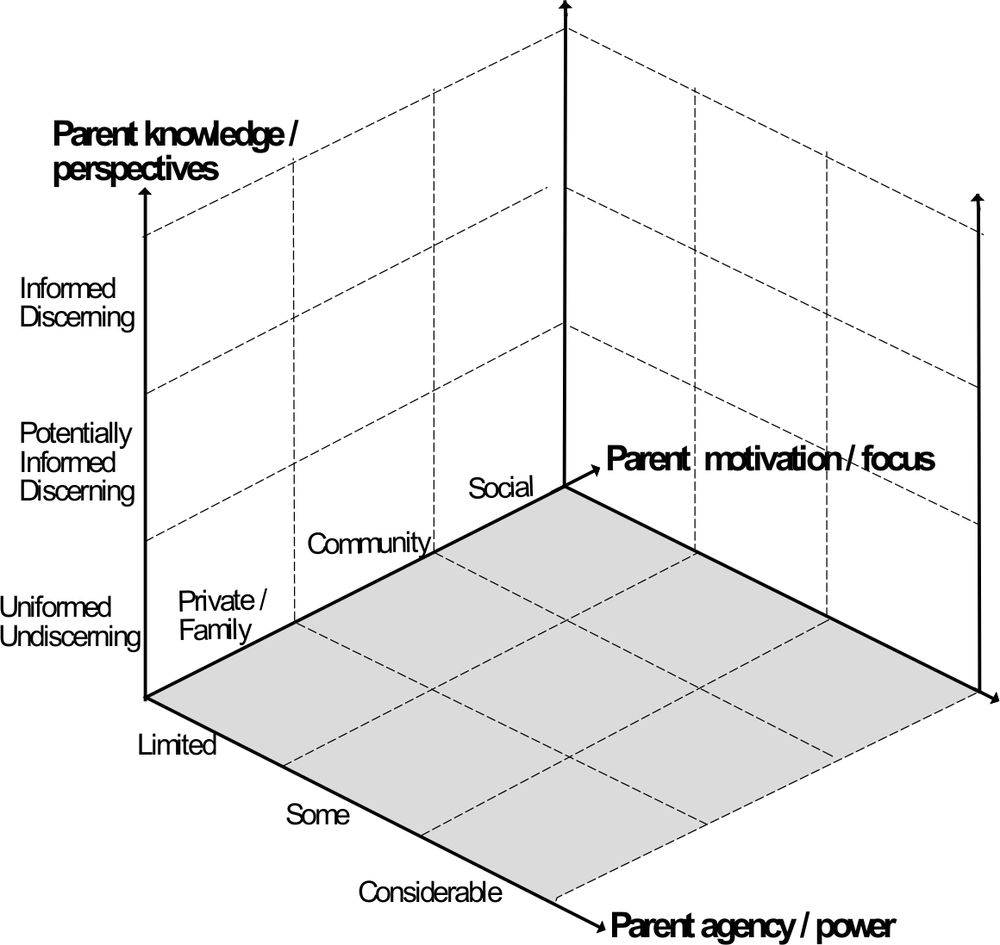

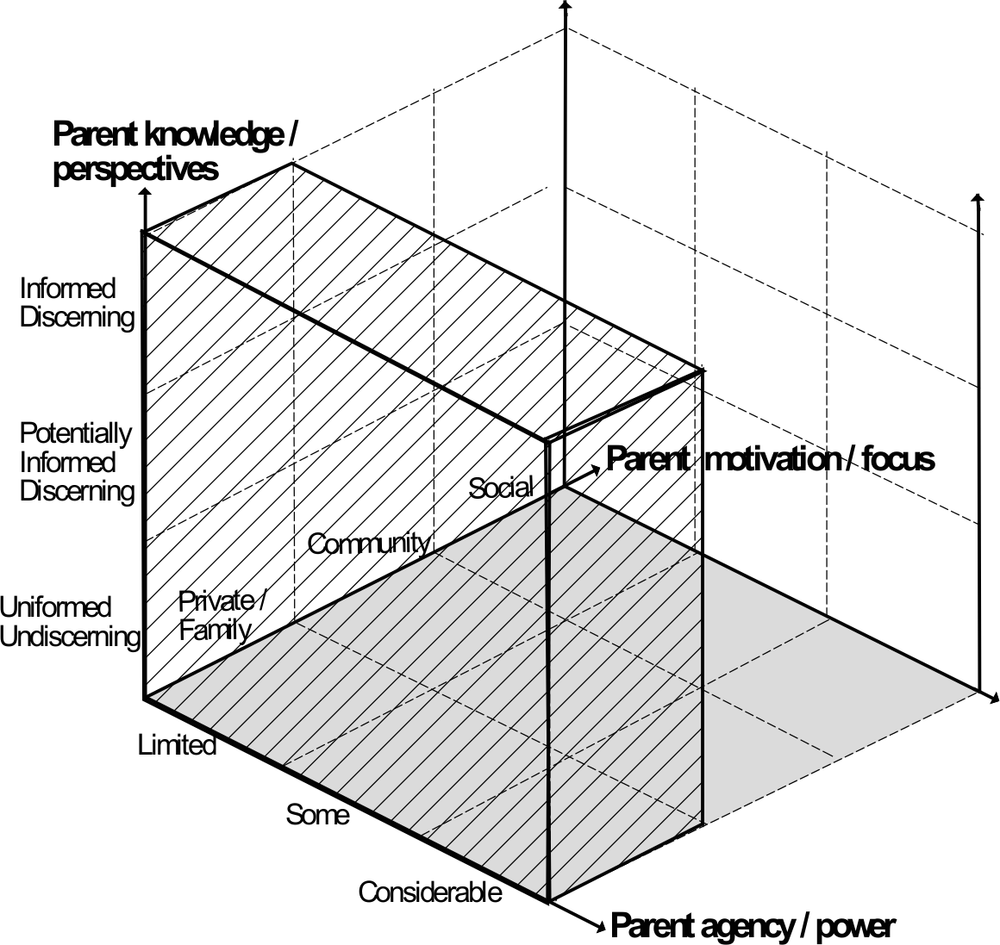

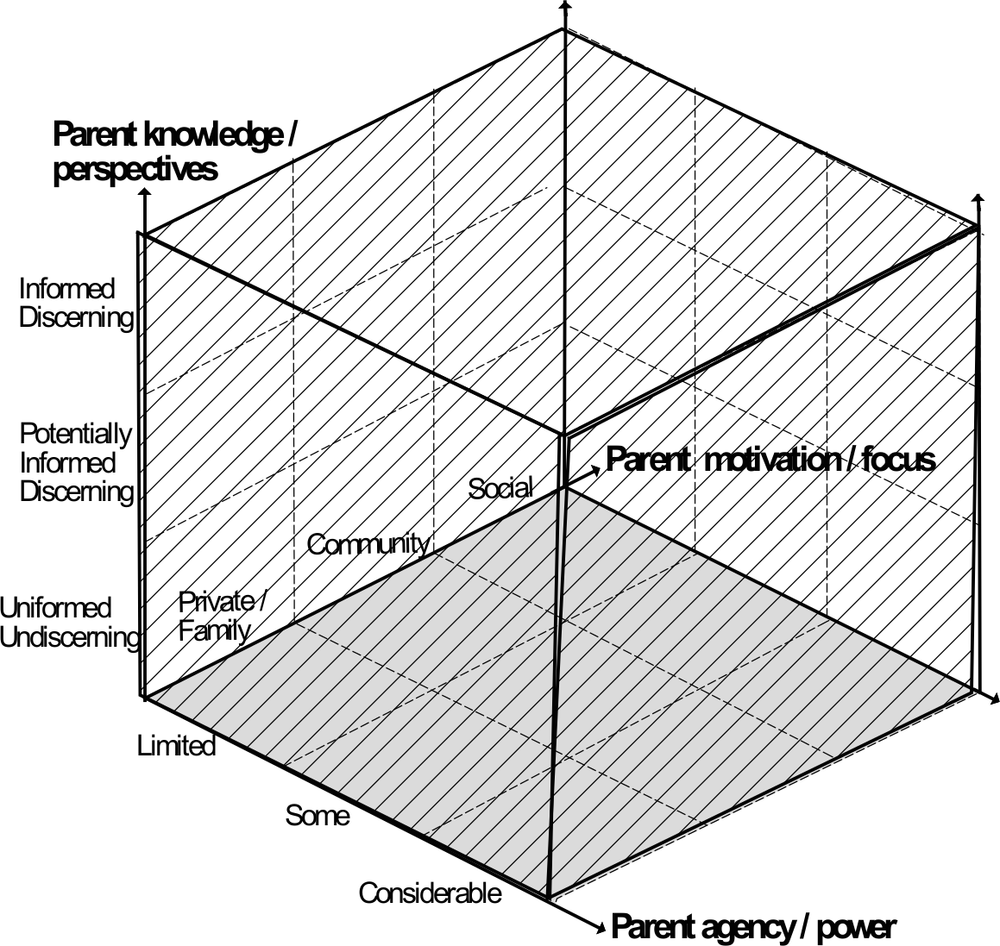

178developed a typology of perspectives on parents as ECEC consumers. As mentioned previously, we see the typology offering a tentative and partial, rather than a conclusive and comprehensive, categorisation; and for ease of discussion, have used a three-dimensional matrix for conceptualising parents’ capacity to bring about demand-led quality improvements to represent categories in the typology (see Figure 7.1). These dimensions were arrived at inductively and are represented by the axes in the matrix. As can be seen in Figure 7.1, the first axis is parent knowledge/perceptiveness, the second axis is parent motivation/focus and the third axis is parent agency/power.

Figure 7.1: Conceptualising parents’ capacity to bring about demand-led quality improvements

179By parent knowledge/perceptiveness, we mean parents’ familiarity with the determinants of quality ECEC generally agreed upon in the research literature; their understanding of how these determinants can and do play out in practice; their awareness that many aspects of quality are intangible and therefore not readily measurable; and their recognition and appreciation of those less tangible aspects. For the purpose of the matrix, we have identified three variations of this dimension: uninformed and undiscerning; potentially informed and discerning; and well informed and discerning. We acknowledge that we have conflated two scales, knowledge and perceptiveness, and the possibility that some parents may lack formal knowledge but be highly perceptive (discerning), or conversely, have considerable formal knowledge but have difficulty applying it to a child care centre. Given the tentative nature of the matrix, however, we do not address that limitation further.

By parent motivation/focus, we mean an amalgam of parents’ hopes, desires, interests and concerns in relation to the quality of ECEC, and where they direct their energies in efforts to realise and address them. We distinguish between a family focus concerned with ECEC as a primarily private benefit centred on the wellbeing of one’s own children/family; a community focus that may encompass but extends beyond a concern for private benefits to include a commitment to enhancing community wellbeing; and a broader social focus that may include a private/family and a community focus but extends beyond these to an explicit concern for the contribution ECEC might make to society more generally.

By parent agency/power, we mean the capacity to bring about the outcomes that one desires and hopes for. This capacity might come primarily from positional advantages and the cultural and economic resources that can assist parents negotiate the complexities and imperfections of ECEC markets, that is, those resources generally associated with middle to high socioeconomic status. Alternatively, the capacity might come from parents, individually or collectively 180initiating and using a mix of creative tactics and strategies to secure the best possible outcomes, given their particular circumstances and regardless of their socioeconomic means. At the risk of obscuring and/or conflating different ways in and purposes for which agency and power can be exercised, we have used the terms ‘limited’, ‘some’ and ‘considerable’ to differentiate between varying degrees of agency and power.6

In the remainder of the chapter, we identify five categories of ways in which parents are positioned as consumers of ECEC in the bodies of literature and websites outlined above. We use the three-dimensional matrix to represent these categorisations. We also consider the feasibility of parent-led improvements to the quality of ECEC reflected in each of these categorisations.

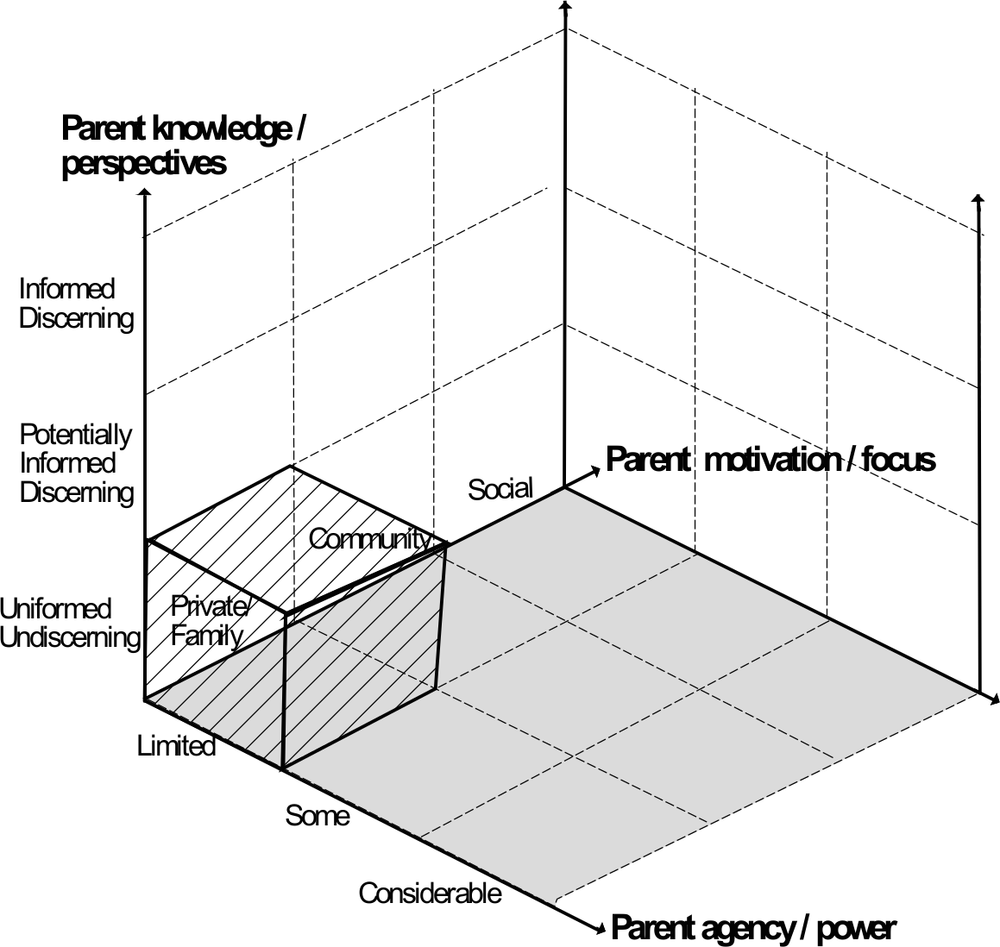

A. Parents as uninformed, undiscerning consumers, focused on private benefits with limited agency/power

Within the early childhood education research field, there have been many investigations of parents’ experiences of ECEC services, their perceptions of the quality of these services and their satisfaction with them (see, for example, Cryer & Burchinal 1997; Cryer et al. 2002; da Silva & Wise 2006; Elliott 2003; Fantuzzo et al. 2006; Knoche et al. 2006; Li-Grining & Coley 2006; Peyton et al. 2001; Ridley-May 2007; Robson 2006; Shlay et al. 2005). Many of these studies dichotomise expert professionals and uninformed, undiscerning service users. For the most part, they emphasise the ‘information asymmetry’ between parents and service providers arising from the difficulties inherent in monitoring quality in imperfect markets that we referred to above. In general, they also accord professional and scientific knowledge greater legitimacy than parent knowledge

181and, for the most part, position parents as naïve consumers with an emotional investment in overestimating, relative to ‘objective’ researcher assessment, the quality of the service attended by their child. With some notable exceptions (for example, da Silva & Wise 2006; Emlen 1998), researchers have demonstrated relatively little interest in participatory approaches that acknowledge the possibility of parent agency, for example, through joint constructions of quality by professionals, service providers and parents. Nor is there much attention to the possibility that parents may see ECEC as more than a private benefit. Two decades ago, Fuqua and Labensohn (1986, p. 295) concluded that ‘parents … in reality did not have the skills of assistance to them to function as wise consumers of child care’, a view echoed in many contemporary studies. For many ECEC researchers, then, the likelihood of demand-led improvements to quality would seem remote. These perspectives of parents, as uninformed and undiscerning consumers who are focused on private benefits but able to exercise little agency or power, are encapsulated in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2: Parents as uninformed, undiscerning consumers, focused on private benefits, with limited agency/power

182

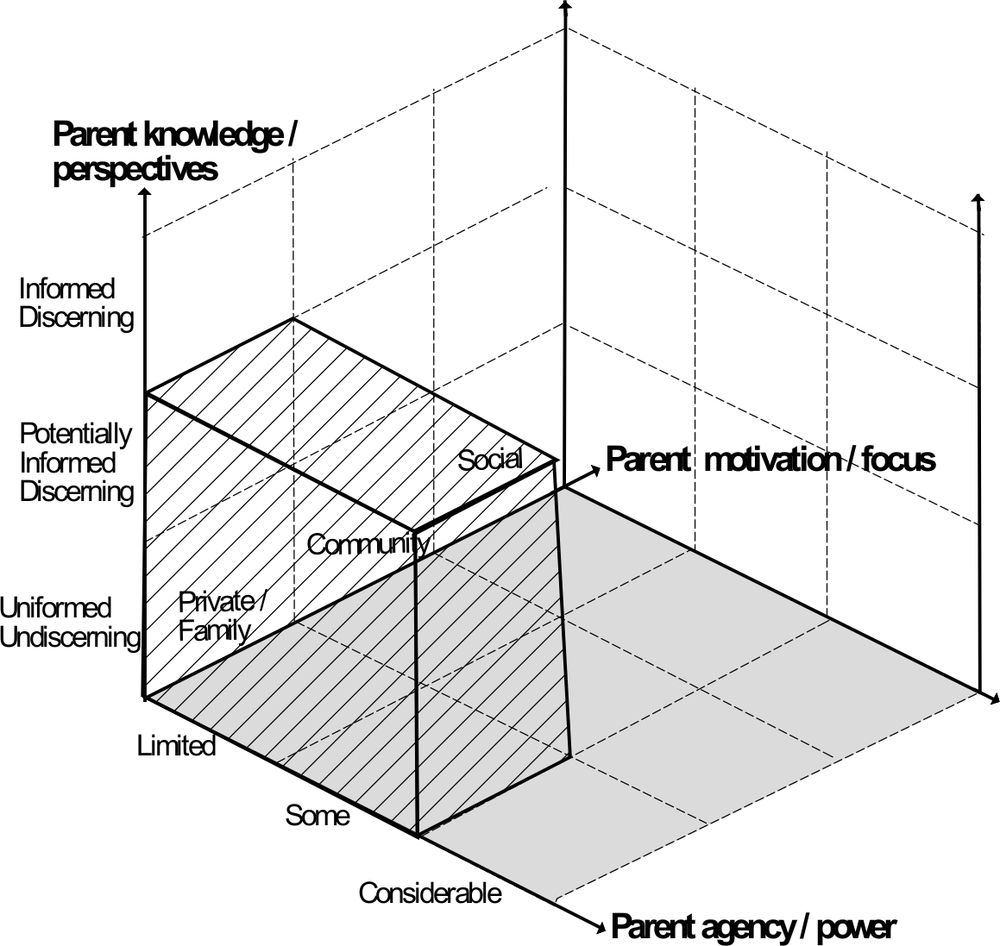

B. Parents as potentially informed and discerning consumers, focused on private benefits with some agency/power

Framed in terms of parents’ obligations as consumers to make responsible and appropriate choices, parent education literature aims to counter the information asymmetries that preoccupied researchers in many of the studies referred to above. As Henderson and Petersen (2002) caution, however, consumer education literature—grounded in the naïve and implausible assumptions that consumer behaviour is always fully informed and logical, which underpin rational choice theory—can itself be limited and naïve. The proliferation of parent information websites, for example, reflects assumptions that parents will have the means to readily access internet facilities, which may not necessarily be the case, especially in marginalised communities.

Our analysis of the websites of ten reputable Australian organisations or government-sponsored bodies offering parent education resources leads us to concur with Henderson and Petersen that, with some notable exceptions, much of the available literature seems to take little account of cross-cultural differences, including differences in values or views about what might constitute appropriate choice. Moreover, it rarely engages with the possibility of restricted choice and frequently ignores relations of knowledge and power between service providers and parents. Much of the parent education literature seems more focused on assisting parents to negotiate, rather than to endeavour to change, the current landscape of ECEC provision. It may also inadvertently perpetuate what we suspect is a common 183assumption among parents and the broader public—that centres that receive government funding must be of reasonable quality. As represented in Figure 7.3, in general, then, parent education literature seems to position parents as potentially informed and discerning consumers, focused on private benefits and able to exercise some agency/power. We conclude, therefore, that although well-intentioned, this literature may have limited potential to inspire and support demand-led improvements to quality.

Figure 7.3: Parents as potentially informed and discerning consumers, focused on private benefits with some agency/power

A promising development is the recent emergence of freely available, non-specialist, plain language research reports (National Institute of 184Child Health and Human Development 2006) and summaries of accumulated research findings (Canadian Centre for Knowledge Mobilisation 2006) of investigations into quality in ECEC. These reports position parents—along with early childhood educators, policy-analysts, and researchers seeking an introduction to ECEC quality—as capable and critical consumers of research who seek empirical evidence as one of the bases for their decision-making. Although some of the criticisms of the more traditional type of parent education literature outlined above could still apply to these reports, they at least refer to the complexities and the contingencies of ‘political, social, national and theoretical contexts’ in the provision of quality care (Canadian Centre for Knowledge Mobilisation 2006, p. 7). It is feasible, therefore, that they could lead some parents to question the simplistic or superficial notions of quality conveyed by some service providers. These reports are notably silent, however, on key debates associated with market-oriented ECEC provision, including whether a profit motive, and in particular, joint responsibilities to shareholders and parents, are compatible with high-quality services. Their silence on such matters, in keeping with their seemingly apolitical intent, could limit their usefulness to parents seeking politicised strategies to procure high-quality care.

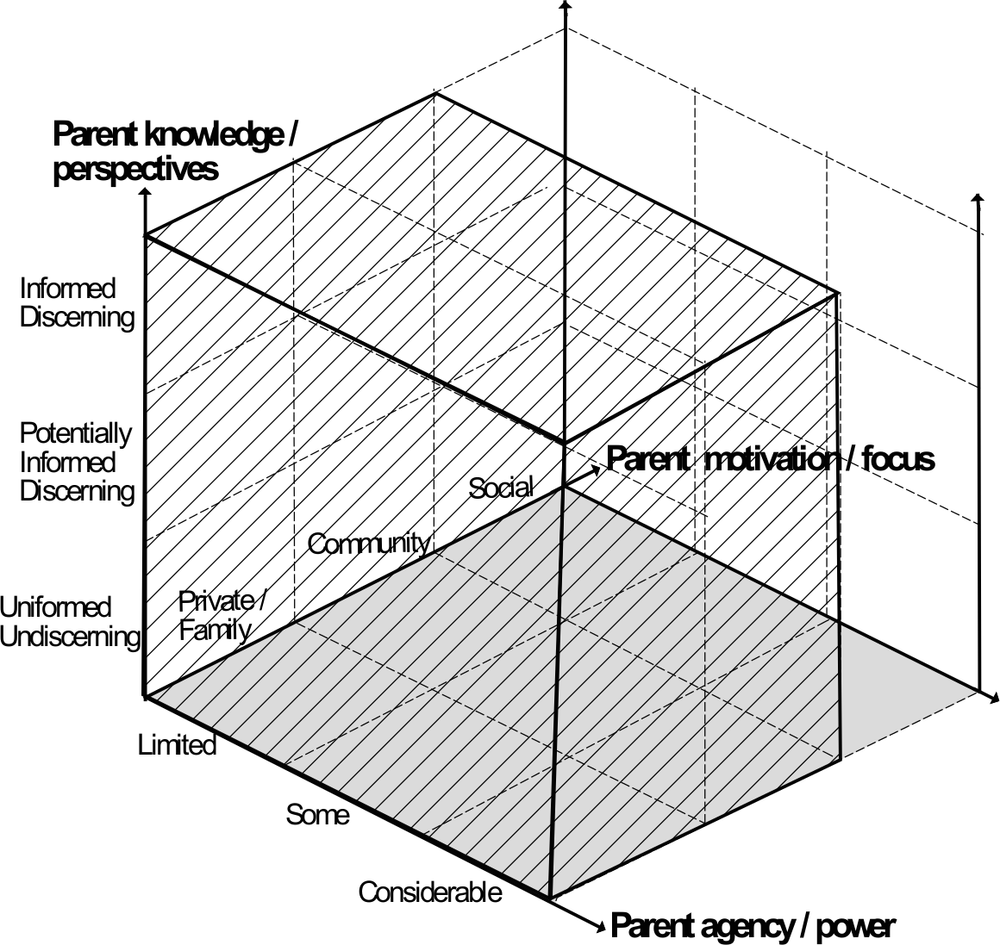

C. Parents as informed, discerning, community-focused consumers with considerable agency/power

Service user evaluation systems position consumers as knowledgeable and discerning, and therefore entitled and equipped to participate in evaluation processes (Newman & Vilder 2006). In Australia, the NCAC aims to encourage active and ongoing parent participation in the life and governance of the service as a means of improving the quality of the service. Accordingly, as part of the NCAC’s child care quality assurance (CCQA) systems, parents are asked to complete a survey that requires them to rate the quality of the service their child attends according to seven ‘quality areas’ and 18533 principles (National Childcare Accreditation Council 2005a).7 Parents’ ratings are assigned a weighting of 10 per cent in the overall evaluation of the service, if at least 40 per cent of parents complete the survey (National Childcare Accreditation Council 2005a). By constructing parents as consumers with considerable agency and power, ECEC service user evaluations, at face value, offer hope of differently constructed relationships between government, service provider and consumer to the kinds of relationships implicitly conveyed in much of the early childhood research and parent education literature. In contrast to the two previous categorisations, they position parents as informed, discerning, community-focused consumers who are able to exercise considerable agency and power. This positioning is represented in Figure 7.4.

Recent research findings (Fenech et al. 2008) and the National Childcare Accreditation Council’s own evaluations, however, highlight a variety of concerns expressed by ECEC staff about the appropriateness and usefulness of the parent surveys used in the CCQA. They range from staff and parent perceptions of user-unfriendly survey formats that leave parents with no space for comment (National Childcare Accreditation Council 2005b) to ECEC staff concerns that asking parents to rate service quality ‘de-professionalises’ ECEC staff (Fenech et al. 2008). These concerns appear to reflect deeply entrenched hierarchies that, perhaps unconsciously, privilege the interests of government agencies, such as NCAC, over those of ECEC staff and parents, and the interests of ECEC staff over the interests of parents—in this case presumably enabling NCAC to fulfil its responsibilities to obtain feedback without permitting the type of specific feedback that could necessitate it taking action, and enabling ECEC staff to use the construct of professionalism to shield them from unwanted parent criticism. More broadly, these concerns raise

186interesting questions about whether service user evaluations are largely symbolic and do little to disrupt traditional power relations between government, service provider and consumer. Indeed, Hodge (2005, p. 164) cautions that ultimately service user evaluations are often ‘little more than mechanisms by which state agencies give their decision-making processes legitimacy, in the process failing to address inherently problematic structural issues and excluding voices that are deemed not acceptable’. Service user evaluations may be superficially transparent and democratic. But if, in effect, they maintain ‘normative boundaries’ that tightly control issues that are allowed on to agendas (Hodge 2005, p. 177), then mechanisms like the NCAC’s quality assurance systems may be relatively ineffective vehicles for demand-led improvements to quality. Moreover, by encouraging parents to place their trust in regulatory systems, and thus presumably allaying parents’ concerns about quality, service user evaluations could be complicit in depoliticising parents and dissuading them of the need for policy activism in relation to ECEC provision.

Figure 7.4: Parents as informed, discerning, community-focused consumers with considerable agency/power

187

D. Parents as informed, discerning consumers, focused on private benefits with considerable agency/power

Critical analyses of ECEC market dynamics, the commodification of ECEC, and implications for power relations between parents and service providers are now emerging (see, for example, Goodfellow 2005; Harris 2008; Vincent & Ball 2006; Woodrow & Press 2007). Some of these analyses (for example, Goodfellow 2005; Vincent & Ball 2006) offer a different way of positioning parents to the three perspectives outlined above—namely (some) parents as informed, discerning, but essentially self-interested consumers for whom ECEC is an ‘individualised calculation’ (Lupton 1997, p. 374, cited by Salter 2004, p. 45), as implied in Figure 7.5. The stakes in getting these calculations ‘right’ are high, argue Vincent and Ball (2006, p. 5), for choice of ECEC service plays an important role ‘in attaining social advantage and in maintaining social divisions’, at least in the largely white, middle-class, inner London context of their study.

Critical perspectives leave open the possibility that information asymmetry, which has featured so strongly in most previous analyses of market-oriented ECEC, does not necessarily equate with power asymmetry. Vincent and Ball contend that to negotiate the child care market successfully, parents need to be ‘energetic, inventive, persistent, flexible and resilient’ and able ‘to deploy the full range of capitals available to them, economic, cultural and social, to achieve their purposes in this market’ (2006, p. 162). Conceivably, the capacity of middle-class 188parents to draw on considerable reserves of capital might enable them to redress information asymmetries, and enable them to be more successful than parents with fewer capital resources in driving demand-led improvements to quality. But if, as Vincent and Ball (2006) argue, ECEC is a mechanism of social reproduction that perpetuates and entrenches middle-class advantage, then middle-class parents’ investments in ECEC in a market-oriented context may tend to focus more on personal advantage, than on enhancing social capital and community infrastructure more broadly. The end result of parent demands for quality in this scenario could lead simply to a more stratified system of ECEC provision, with high-quality services for those who can afford them and low-quality services for those who cannot.

Figure 7.5: Parents as informed, discerning consumers, focused on private benefits with considerable agency/power

189Similarly, where self-interest is a primary motivator, there is scope for collusion between service providers that want to attract what they see as ‘high value’ children, a term used by Kenway and Bullen (2001), and parents who want to avoid services that, in their view, accept ‘low value’ children. Take, for example, provision for children with special needs, which Cleveland and Krashinsky (2002, p. 40) refer to as a ‘little discussed, but potentially important, problem in relation to demand-side subsidies’. As they point out:

providing ECEC for special-needs children is resource-intensive and may therefore divert resources away from other children. Parents, concerned generally with the welfare of their own children, will tend to avoid centres that divert resources in this way. As parents self-select into centres without special-needs children, centres with them will be driven out of business (p. 40).

A related possibility is that parents may be well-informed about experts’ views about quality but, in locations where choice is possible, may actively select a service that is more aligned with parents’ own values and goals, perhaps for religious or cultural reasons, or as already discussed, for reasons of social advantage. None of these scenarios is conducive to broadly based demand-led improvements to service quality.

E. Parents as informed, discerning, activist citizen-consumers, focused on social benefits with considerable agency/power

This perspective represents a distinct shift from market discourses of consumerism based on consumption for private gain, to discourses of activist consumerism grounded in participatory democracy and active citizen involvement for the common good (see also Dalton & Wilson 2009). Casting children, and social policy provision for 190them, as a shared responsibility positions parents as politically astute consumers and citizens who, by acting collectively, can exert demand-side pressure to raise the overall quality of services, rather than simply being content to make informed but ultimately self-interested choices for their private benefit or that of their immediate community as represented in Figure 7.6. An underpinning assumption is that a collective sense of responsibility and concern, in this case for children’s wellbeing, can be a powerful force for change that goes beyond the level of the service and the community in which it is located through articulating new demands, challenging entrenched provider interests, and ultimately shaping ‘the discourses and practices of government’ (Herbert-Cheshire 2003, p. 468).

Whether those most affected by particular policies can successfully challenge, negotiate, and ultimately transform those policies (Herbert-Cheshire 2003) is contestable. According to Henderson and Petersen (2002), the selective appropriation of consumerist discourses by activist groups has proven a useful strategy:

the identity label “the consumer” and the language of consumerism have proved useful to numerous groups in their efforts to make visible their claims … and to protect and advance their interests. The strategic use of identity labels, or so-called “strategic essentialism” where groups assume a cohesive identity for specific political purposes, has been shown to be effective in feminist struggles and in advancing the position of minority groups (p. 4).

Similarly, but with a different focus, Itkonen (2007) analyses successful approaches to political activism by parents of children with special education needs in the United States. She documents in considerable detail specific strategies used by these parent activists to secure much improved provision for their children. The most effective strategies for gaining political traction in policy networks included highly strategic issues-framing and problem definition, and ‘sophisticated political storytelling’ (Itkonen 2007, p. 600). 191

Figure 7.6: Parents as informed, discerning, activist citizen-consumers, focused on social benefits with considerable agency/power

In contrast, Salter (2004, p. 66) counters that government and powerful providers ‘know that it is in their best interests to construct a consensus’ and hence are ‘disinclined to destabilise’ the status quo by admitting ‘new and unpredictable’ activist networks into policy decision-making in any meaningful way. Citing the relatively limited impact of consumer health movements in the United Kingdom, Salter warns that, at most, we might see ‘a reformulation of the relationships between the principal actors … but not a significant redistribution of power between them’ (2004, p. 187). Although there are parallels between what Salter sees as the somewhat limited 192outcomes achieved by United Kingdom consumer health activism movements and the outcomes achieved by Australian ECEC activists to date, contextual differences countenance hope. Unlike the United Kingdom medical establishment, ABC Learning, for example, while an indisputably powerful entity, does not and cannot claim to speak on behalf of the ECEC field. Despite concerns about the former Howard Government’s ECEC policy creating a mutual dependency between childcare corporations and the state (Sumsion 2006), ABC Learning particularly since its corporate collapse, remains more dependent on the Australian Government for its survival than the government is on it.8 Consequently, in terms of power relations between consumers, government and service providers, ABC Learning is comparatively less powerfully positioned than the United Kingdom medical establishment, as portrayed in Salter’s analysis, and therefore more vulnerable to shifts in power relations. If, as Salter suggests, these power relations are constantly changing, this vulnerability presumably provides openings for consumer activists to influence Australian ECEC policy decisions. As Salter (2004, p. 65) cautions, however, any ‘translation of consumer pressure into significant power shifts’ will be an inevitably uncertain and complex process.

To date, there appear to have been few formal, in-depth investigations specifically focused on shifting power relations between consumers, governments and ECEC providers in Australian ECEC policy networks. Notable exceptions include the historical and contemporary analyses undertaken by Brennan—see especially Brennan (1998) for a tracing of parent-led demands for quality improvement in the 1970s and the establishment of long day care services in Australia, through to the 1990s. Nor, indeed, has there been much attention

193to activist consumerism or citizenship as a theoretical lens or basis for empirical investigations of efforts to enhance quality in ECEC. Such investigations would constitute a distinct shift in thinking about the possibility of parents initiating demand-led improvements to quality because they would involve rejecting the commonly arrived at conclusion that, inevitably and necessarily, parents tailor their views about quality to accommodate the ‘social and economic realities that limit their range of feasible options’ (Meyers & Jordan 2006, p. 60). Rather, they would keep alive the possibility of parents collectively challenging, instead of acquiescing to and accepting, those ‘realities’, including the problems stemming from market imperfections. Empirical investigations would contribute to developing a much-needed knowledge base about effective citizen activism.

In her economic analysis of the potential of the paid care sector, including ECEC, to build political coalitions, Folbre (2006) emphasises the scope to build powerful strategic alliances between careworkers and care consumers because of the strong emotional and personal valency of their connections. In Australia, ECEC professionals have engaged parents in campaigns to improve quality, including the recently successful ‘1:4 Make it Law’ campaign in New South Wales for improved staff-child ratios for babies and toddlers in long day care. Conceivably, parent-initiated campaigns that engage ECEC professionals, as well as community and business leaders, could ratchet up demand-led pressure for quality improvement. Harris’ (2008) qualitative study of women’s reflections on choosing long day care in a regional community in Queensland highlights the importance the participants placed on high-quality ECEC; their dissatisfaction with the market model of ECEC provision; the lack of choice they perceived it offered them; and a deep scepticism about the compatibility of the pursuit of high-quality care and corporate profits. We argue that when proponents of market mechanisms ignore the impact of these mechanisms on people’s lives and people feel passionately about the aspects of their lives affected, as Harris (2008) maintains is so with ECEC, there is the potential for mobilisation—in this case for demand-led changes to ECEC policy and quality. 194

Admittedly, it would be easy to romanticise the notion of parents as activist consumers and citizens demanding and procuring universally high-quality ECEC. Prior to the 2007 Australian federal election, it would also have been easy to dismiss the prospect as remote, given the Howard Government’s seemingly entrenched market-oriented approach to social policy provision generally and its concomitant, concerted and arguably successful efforts to re-configure its citizens as self-interested and self-absorbed consumers (Pusey 2003). Yet in the light of the emergence of the albeit socially conservative Family First political party9 at the 2004 Australian federal election, perhaps it would be premature to discount the possibility of parents’ commitment to, and investment in, their children’s wellbeing providing a catalyst for a groundswell of community-wide repudiation of market-based policies in social services provision, including ECEC. The Rudd Government’s ‘Community Cabinet’ meetings offering citizens the opportunity to register for a chance to meet with a federal minister of their choice (O’Brien & MacDonald 2008) also holds new possibilities for influencing ECEC policy in participatory democratic ways. As an ad hoc political force, in a changing political environment, parents could conceivably bring about what the market has so far failed to deliver.

Concluding thoughts

As we have reiterated throughout, the five perspectives on parents as ECEC consumers outlined in this chapter are neither exhaustive

195nor mutually exclusive but simply a starting point for addressing the many ‘absences and silences’ (Vincent & Ball 2006, p. 134) concerning the feasibility of demand-led improvements to quality in market-oriented ECEC provision. In our view, these perspectives provide a tentative but potentially fruitful framework for conceptualising relations between governments, service providers and parents in the ECEC market place, and for considering how these relations might be reconfigured. They also invite consideration of how different policy contexts, market structures and interventions might create or make possible particular perspectives on, and positionings of, parents as consumers of ECEC, and render other perspectives and positionings irrelevant. For example, in a policy context where major decisions about ECEC policy directions required joint negotiation between government, communities and providers with an emphasis on ongoing collaboration to meet jointly agreed-upon goals, perspectives on parents as actively engaged citizens might become unremarkable. Likewise, if there were universal access to high-quality services, there would appear little need for self-interested pursuit of high-quality places for one’s children, and a stratum of self-interested consumers might not emerge. Empirical evidence of any relationships between policy contexts, market structure and interventions and the positioning of parents could add impetus and a new dimension to considerations of the real and opportunity costs and benefits of ECEC policy decisions, especially in relation to opportunities for social engagement and community building, as the marked difference between Figures 7.2 and 7.6 suggests.

Similarly, the perspectives identified in the typology invite consideration of how policy contexts might interact with local ECEC markets to position parents in particular ways. In ‘thick’ markets (Cleveland & Krashinsky 2005), for example, where parents have a choice of services, a wider range of positionings might be possible than in local contexts where demand for places far outstrips supply. If this were the case, then questions arise about implications of policy-market relations for urban, regional, and rural communities, 196especially about what might be possible for parent-led demands for improvements to quality.

The dimensions of variation in the typology, and corresponding axes in the matrix, identify some useful directions for further conceptual investigation and highlight areas where empirical evidence is needed. The ‘parent agency and power’ dimension, for example, raises questions about the kinds of activism and ‘parent power’ that it might take for the governments to want, or need, to forge new kinds of political alliances with parents that go beyond the somewhat tokenistic parent representation in ECEC policy in Australia, at least in the last decade or so. It also raises questions about what these political alliances might look like, whose interests they might serve, and how the voices of marginalised parents, and not just those of middle-class parents, could be heard. Further questions could focus on the scope for joint activism by parents and ECEC staff, and on processes of activism that tend to be most effective in particular kinds of contexts. Knowing more about processes by which consumer and citizen demands for change could be translated into new policies, at the level of service provider, and beyond, rather than merely accommodated in ways that maintain traditional power relations, would also be useful (Salter 2004); in other words, identifying how to bring about change at service provider and government policy level that goes deeper than rhetoric. Each dimension of variation in the typology has the scope to provide an equivalent set of questions.

Investigations of the kinds suggested here would focus much needed attention on some of the under-addressed dynamics of ECEC market forces and the relations underpinning them. In particular, they would render more complex current conceptualisations of parents as consumers of ECEC and hopefully identify new and alternative stances that parents as participants in ECEC market transactions might take up. Clearly, much work is needed before any conclusions can be drawn concerning the feasibility of parents driving demand-led improvements to quality. We believe, however, that there are 197grounds for cautious optimism, and that the possibilities raised in this chapter warrant further investigation.

References

Brennan, D. 1998, The Politics of Australian Child Care: Philanthropy to Feminism and Beyond, (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Brennan, D. 2007, ‘The ABC of child care politics’, Australian Journal of Social Issues, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 213–25.

Canadian Centre for Knowledge Mobilisation 2006, CCKM’s Research Guide to Child Care Decision Making [Online], Available: http://www.cckm.ca/ChildCare/home.htm [2006, Oct 11].

Cleveland, G. & Krashinsky, M. 2002, Financing ECEC Services in OECD Countries: OECD Occasional Papers [Online], Available: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/55/59/28123665.pdf#search=%22Financing%20ECEC%20services%20in%20OECD%20Countries%22 [2005, Mar 3].

Cleveland, G. & Krashinsky, M. 2005, The Nonprofit Advantage: Producing Quality in Thick and Thin Child Care Markets [Online], Available: http://childcarepolicy.net/pdf/non-profitadvantage.pdf [2006, Feb 4].

Cox, E. 2007, ‘Funding children’s services’, in Kids Count: Better Early Childhood Education and Care in Australia, eds E. Hill, B. Pocock & A. Elliott, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Cryer, D. & Burchinal, M. 1997, ‘Parents as child care consumers’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 35–58.

Cryer, D., Tietze, W. & Wessels, H. 2002, ‘Parents’ perceptions of their children’s child care: A cross-national comparison’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 259–77.

da Silva, L. & Wise, S. 2006, ‘Parent perspectives on childcare quality among a culturally diverse sample’, Australian Journal of Early Childhood, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 6–14.

Dalton, B. & Wilson, R. 2009, ‘Improving quality in Australian child care: The role of the media and non-profit providers’, in Paid Care in Australia: Politics, Profits, Practices, eds D. King & G. Meagher, Sydney University Press, Sydney. 198

Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs 2008, Stronger Families and Communities Strategy [Online], Accessed at: http://www.facsia.gov.au/internet/facsinternet.nsf/aboutfacs/programs/sfsc-sfcs.htm [2008, Aug 14]

Duncan, S., Edwards, R., Reynolds, T. & Alldred, P. 2004, ‘Mothers and child care: Policies, values and theories’, Children and Society, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 254–65.

Elliott, R. 2003, ‘Sharing care and education: Parents’ perspectives’, Australian Journal of Early Childhood, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 14–22.

Emlen, A. C. 1998, From a Parent’s Point of View: Flexibility, Income, and Quality of Child Care: Background Paper [Online], Available: http://www.ssw.pdx.edu/focus/emlen/documents/pdfBethesda1998.pdf#search=%22Emlen%20from%20a%20parent’s%20point%20of%20 view%22 [2006, Mar 3].

Fantuzzo J., Perry, M. A. & Childs, S. 2006, ‘Parent satisfaction with educational experiences scale: A multivariate examination of parent satisfaction with early childhood education programs’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 142–52.

Fenech M., Sumsion, J. & Goodfellow, J. 2008, ‘Regulation and risk: Early childhood education and care services as sites where “the laugh of Foucault” resounds’, Journal of Education Policy, vol. 23, no.1, pp. 35–48.

Folbre, N. 2006, ‘Demanding quality: Worker/consumer coalitions and “high road” strategies in the care sector’, Politics and Society, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 1–21.

Fuqua, R. W. & Labensohn, D. 1986, ‘Parents as consumers of child care’, Family Relations, vol. 35, no. 2. pp. 295–303.

Gillard, J. 2008a, Budget: The Education Revolution, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

Gillard, J. 2008b, Radio Interview ABC, 8.45am Wednesday, 4 June 2008 [Online], Accessed at http://mediacentre.dewr.gov.au/mediacentre/Gillard/Releases/ChildcarefeesFuelWatch.htm [2008, Dec 31].

Goodfellow, J. 2005, ‘Market childcare: Preliminary considerations of a “property view” of the child’, Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 54–65. 199

Harris, N. 2008, ‘Women’s reflections on choosing quality long day care in a regional community’, Australian Journal of Early Childhood, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 42–49.

Hand, K. 2005, ‘Mothers’ views on using formal child care’, Family Matters, vol. 70, pp. 10–17.

Helburn, S. W. & Howes, C. 1996, ‘Child care cost and quality’, The Future of Children, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 62–82.

Henderson, S. & Petersen, A. 2002, ‘Introduction: Consumerism in health care’, in Consuming Health: The Commodification of Health Care, eds S. Henderson & A. Petersen, Routledge, London and New York, pp. 1–30.

Herbert-Cheshire, L. 2003, ‘Translating policy: Power and action in Australia’s country towns’, Sociologia Ruralis, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 454–73.

Hodge, S. 2005, ‘Participation, discourse and power: A case study in service user involvement’, Critical Social Policy, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 164–79.

Itkonen, T. 2007, ‘Politics of passion: Collective action from pain and loss’, American Journal of Education, vol. 113, no. 4, pp. 577–604.

Jokovich, E. 2005, ‘Family payment: About face muddies the waters’, Rattler, vol. 73, pp. 6–7.

Kenway, J. & Bullen, E. 2001, Consuming Children: Education-Entertainment-Advertising, Open University Press, Maidenhead and Philadelphia.

Knoche, L., Peterson, C. A., Edwards, C. P. & Hyun-Joo, J. 2006, ‘Child care for children with and without disabilities: The provider, observer, and parent perspectives’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 93–109.

Li-Grining, C. P. & Coley, R. L. 2006, ‘Child care experiences in low-income communities: Developmental quality and maternal views’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 125–41.

Mayne, S. 2008, Time to put ABC Learning out of its misery, Crikey Business [Online], Accessed at: http://www.crikey.com.au/Business/20080611-Time-to-put-ABC-Learning-out-of-its-misery.html [2008, Dec 31].

Meyers, M. K. & Jordan, L. P. 2006, ‘Choice and accommodation in parental child care’, Community Development, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 53–70. 200

National Childcare Accreditation Council 2005a, Quality Improvement and Accreditation System: Information about the Accreditation Decision [Online], Available: http://www.ncac.gov.au/support_documents/qias_decision_information.pdf [2006, Apr 4].

National Childcare Accreditation Council 2005b, Validation Evaluation Form Analysis: Validation visits conducted October/November 2005 [Online], Available: http://www.ncac.gov.au/report_documents/vef_analysis_2005.PDF [2006, Apr 4].

National Childcare Accreditation Council 2008, Quality Trends Reports [Online], Accessed at: http://www.ncac.gov.au/reports_statistics/reports_stats_index.html#papers [2008, Jan 21].

Newman, J. & Vidler, E. 2006, ‘Discriminating customers, responsible patients, empowered users: Consumerism and the modernisation of health care’, Journal of Social Policy, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 193–209.

NICHD (National Institute of Child Health and Development) and Network, Early Child Care Research 2002, ‘Early child care and children’s development prior to school entry: Results from the NICHD study of early child care’, American Educational Research Journal, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 133–64.

National Institute of Child Health and Development and Network 2006, The NICHD study of early child care and youth development: Findings for children up to age 4½ years [Online], Available: http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/upload/seccyd_051206.pdf [2006, Oct 10].

O’Brien, A. & MacDonald, J. 2008, ‘It’s the simple questions that count’, The Australian, January 21, pp. 1–2.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2006, Starting Strong 11: Early Childhood Education and Care, OECD, Paris.

Ozga, J. 2000, Policy Research in Educational Settings, Open University Press, Buckingham.

Peyton, V. Jacobs, A., O’Brien, M. & Roy, C. 2001, ‘Reasons for choosing child care: Associations with family factors, quality, and satisfaction’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 191–208.

Press, F. 2006, What about the kids? Policy directions for improving the experiences of infants and young children in a changing world, 201

Commissioned report to the NSW Commission for Children and Young People, Commission for Children and Young People, and Child Guardian, and the National Investment of the Early Years (NIFTeY) NSW Commission for Children and Young People, Sydney.

Press, F. & Woodrow, C. 2005, ‘Commodification, corporatisation and children’s spaces,’ Australian Journal of Education, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 278–91.

Press, F. & Woodrow, C. 2009, ‘The giant in the playground: Investigating the reach and implications of the corporatisation of childcare provision’, in Paid Care in Australia: Politics, Profits, Practices, eds D. King & G. Meagher, Sydney University Press, Sydney.

Pryor, L. 2006, ‘Child care horrors kept from parents’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 March, p. 1.

Pusey, M. 2003, The Experience of Middle Australia: The Dark Side of Economic Reform, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Raising Children Network 2008, Raising children network: The Australian Parenting Site [Online], Available: http://raisingchildren.net.au/ [2008, Aug 14].

Ridley-May, K. 2007, Sure Start Children’s Centres Parental Satisfaction Survey Report and Annexes 2007. Research Report RW108, Department for Education and Skills, [Online], Available: http://www.dfes.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/RW108.pdf [2008, Jan 14].

Robson, S. 2006, ‘Parent perspectives on services and relationships in two English early years centres’, Early Child Development and Care, vol. 176, no. 5, pp. 443–60.

Rudd, K. & Macklin, J. 2007, Labor’s plan for high quality care: Election 2007 policy document [Online], Accessed at http://www.alp.org.au/download/now/microsoft_word_071023_quality_child_care_policy_document_final.pdf [2008, Jan 21].

Salter, B. 2004, The New Politics of Medicine, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke and New York.

Shlay, A. B., Tran, H., Weinraub, M. & Harmon, M. 2005, ‘Teasing apart the child care conundrum: A factorial survey analysis of perceptions of 202child care quality, fair market price and willingness to pay by low-income, African American parents’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 393–416.

Stanley, K., Bellamy, K. & Cooke, G. 2006, Equal access: Appropriate and affordable childcare for every child [Online], Accessed at: http://www.ippr.org/members/download.asp?f=%2Fecomm%2Ffiles%2Fequal%5Faccess%2Epdf [2008, Dec 31].

Sumsion, J. 2006, ‘The corporatisation of Australian childcare: Towards an ethical audit and research agenda’, Journal of Early Childhood Research, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 99–120.

Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Simmons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, L., Taggart, B. & Elliot, K. 2003, The effective provision of pre-school education (EPPE) project: Findings from the pre-school period, Summary of findings [Online], Available: http://www.ioe.ac.uk/schools/ecpe/eppe/eppe/eppefindings.htm [2006, Oct 10].

Vincent, C. & Ball, S. 2006, Childcare, Choice and Class Practices: Middle-Class Parents and Their Children, Routledge, London and New York.

Walsh, L. 2006, ‘Job’s not as easy as ABC’, Courier Mail [Online], Accessed at: http://www.couriermail.news.com.au/story/0,20797,19401027-953,00.html [2006, Jun 8].

Woodrow, C. & Press, F. 2007, ‘Repositioning the child in the policy politics of early childhood’, Educational Philosophy and Theory, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 312–25.

1 See, for example, the Raising Children Network (2008).

2 See, for example, the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy (Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs 2008).

3 Cleveland and Krashinsky (2005) designated Canadian communities with at least 25,000 children aged from birth to four years, and with average annual earnings per employed person in 2001 of $31,500 or more, as ‘thick’ markets. ‘Thin’ markets comprised communities with fewer than 15,000 children aged birth to four years, and annual average earnings of less than $31,500.

4 We searched the North American-based journals Early Childhood Research Quarterly, the United Kingdom-based Early Child Development and Care, the European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, and the Australian Journal of Early Childhood.

5 These studies include The Effective Provision of Pre-School Education (EPPE) study (Sylva et al. 2003), the NICHD study (NICHD 2006) and several Canadian studies (Canadian Centre for Knowledge Mobilization 2006).

6 Agency and power might be exercised, for example, in selecting a centre, participating in the life and governance of the centre, participating in the community, participating in the community that the centre seeks to serve, and in policy participation at any of the jurisdictional levels concerned with ECEC.

7 There can be a tendency for parent evaluation surveys to become little more than ‘one-off’ events in each accreditation cycle, rather than simply a component of ongoing parent participation to improve quality, as envisaged by the NCAC.

8 This is not to imply that the Rudd Government would readily introduce policies that would disadvantage ABC Learning, but rather to note that a corporate collapse or withdrawal by ABC Learning from the ECEC market would not trigger the collapse of long day care provision. As such, ABC Learning would not have to be propped up by the government regardless of the cost involved in doing so.

9 The 2004 Australian Federal Election saw the emergence of the newly established, conservative Family First party as a new and influential political force, with sole elected representative, Steve Fielding holding the balance of power in the Senate. Senator Fielding remained in a strong bargaining position when the new Senate took effect in July, 2008. Family First promotes family values and the need for government policies to take account of the interests of families. As a formal political party, it differs from the ad hoc political action envisaged in this paper, but nevertheless demonstrates the potential political power that can come from mobilising parents’ interests and broader community support for families.