Editor’s Foreword

This book would not have required an editor had not the great distance of the author from his homeland made it impossible for him to undertake the tasks involved with the printing. The manuscript that Herr Parkinson submitted was ready for press; it certainly appeared, as one may still perceive in the text, that it was not written in one piece but originated piecemeal as the investigations of the author progressed and expanded. It might have been more convenient to arrange the material more pertinently and systematically; but the editor too could not justify what the author had not deemed necessary. Thus everything has remained essentially as the author wrote it; only stylistic unevenness and repetitions, explicable by the nature of the origin of the book, have been removed, as far as possible. Nowhere have I undertaken factual changes, not even in those instances where I have not been in agreement with the author. This is particularly so in theoretical discussions. Situations have another perspective when one is personally confronted with them in real life, rather than when one critically examines them in one’s study. Advantages and disadvantages are found on both sides. Whoever lives in the open among the children of nature knows the conditions better than the scholar at home; but he judges the origin and development of these conditions one-sidedly, because the possibility of comparison with related phenomena is lacking, which only an extensive knowledge of the literature would provide. Thus Herr Parkinson’s theories – for example, on the origin of the secret societies – do not find overall agreement with the experts. Despite this, I have let everything remain unaltered, even the daring hypothesis that argues its way back to a manifesto of anthropological similarities between the inhabitants of New Britain and the Australians, from an apparent connection of both regions at the beginning of the Tertiary Period. One can at the very least call the hypothesis courageous, since until now even the most highly fanciful anthropologist has not once attempted to date the existence of mankind generally, not to mention a mankind already differentiated into races, further back than the beginning of the Tertiary Period. Whether mankind existed even at the end of this period is still disputed by the experts.

However, such hypotheses should not form an absolute in knowledge; they are only there to bring together for the first time an entangled mass of evidence into a provisional form. By their subjective nature they have more value to their authors than to others, and like all hypotheses, are judged accordingly, to be cast off by others as knowledge progresses. Similarly, in this book also, they are only non-essential parts, the chief value lying in the large amount of factual material that it contains, which forms a veritable mine of information for ethnologists. Certainly the book is not intended to give a scientific, exhaustive presentation of the ethnology of the Bismarck Archipelago – specialist works of the author published earlier contain more details on their defined areas – it is not directed exclusively to scholars but predominantly to a broader circle that has an interest in our colonies and their inhabitants. We have only few such books; the earlier, vigorous interest in land and ethnological reading has sunk markedly since the end of the period of the great journeys of discovery, and only arises anew in direct connection with colonial politics.

The new colonial-political era has not been without influence on the character of this literature. With the now completed partitioning of the earth among the civilised states of Europe and America, the scientific investigation of the earth also has become more and more nationalised, so to speak. The states had primarily the intention only of securing the economic exploitation of certain regions; but after the division of economic and commercial zones there soon followed the division of scientific work. It was, of course, also natural that the scholars whose interests had previously indiscriminately covered the entire earth, now turned in preference to the overseas colonies of their own fatherlands. The time of great world journeys, the traversing of entire continents – the crossings of Africa have already been reduced to sports – have passed, on the one hand because the earth is largely xxxviknown, and there is no longer anything major to discover, but also because each of the great civilised nations have secured a portion of the earth’s surface for themselves and confined themselves to it. They are beginning to look around their property and establish themselves domestically.

In the process, the scientific study of land and people has remained firmly in the background; practical needs, the demands of merchants and planters had to be considered first. Above all, the security and convenience of commerce, improvement of sanitary conditions, the supply of a labour force, and so on, had to be taken care of. Naturally, there was much profit for science in this. Good maps were a first requirement, and we know how excellently many officers of our protectorate forces have performed in this area; no less important were the exploration of the soil and mineral treasures, and the knowledge of useful plants. These investigations have brought rich gains to geography, geology and botany. However, this scientific exploitation resulted more fortuitously and incidentally; the dominant feature was immediate, practical usefulness. Thus it came about that the sciences that promised no direct benefit were neglected, primarily the science of mankind and his culture, anthropology and ethnology.

It has certainly been stressed often enough that successful colonial politics, which are yet based to a great extent on a proper, purposeful treatment of the natives, are only possible on the basis of thorough ethnological knowledge. One must first of all get to know a people that one wishes to rule; one cannot expect that a primitive people become familiar with the complicated structures of our civilisation, with our fine understanding of completely foreign perceptions of justice or moral concepts, rather we must endeavour to understand their culture, their thoughts and their sentiments. However, despite the various activities that are often the ultimate cause of native revolts, through the violation of customs or perceptions that appear laughable or absurd to us but are sacred to them, one has mostly preached to deaf ears. Ethnology is still an unappreciated, but for the first time growing, science, which is studied neither in schools nor in universities, and therefore even among the educated only seldom finds real understanding. The ethnographic museums are still collections of curiosities to lay people; that the stored rarities might have another purpose than the pleasure of passing curiosity, comes least to mind.

This lack of interest and understanding can not, of course, be remedied overnight. However, nothing is more appropriate for dragging meaningful participation in ethnological problems out of the narrow circle of specialists into the broader popular circle than the universally understandable books of this present type. Nobody who is aware with what loving zeal he has studied the life of the natives during the entire thirty years of his stay in the South Seas is in any doubt that Herr Parkinson was the appropriate person to write such a book on the Bismarck Archipelago and its inhabitants. Witnesses to this are his numerous scientific essays, and no less so the many beautiful artifacts for which the German museums, particularly those of Dresden and Berlin, are obliged to his collecting zeal.

One can therefore only wish that the book finds its merited success with the German public, and that the opportunity will soon be given to the author to remove the deficiencies adherent to a first attempt, in a second edition.

The illustrations that adorn the book are for the most part taken from the author’s original photographs; some of them, however, are from photographs of objects in the Berliner Museum für Völkerkunde. These are illustrations numbers 61 to 64, 66, 70, 82, 102, 117 to 119, and 123 to 125.

The pen drawings in the Berlin Museum were similarly produced, partly from Parkinson’s pencil sketches, partly from illustrations in the author’s earlier publications, and partly from originals in the Berlin Museum.

Table 49 and the text illustrations numbers 120 to 122 are reproduced from the splendid tables in the Publikationen aus dem Königlichen Ethnographischen Museum zu Dresden, volumes 10 and 13, with kind permission of the publishers, von Stengel & Co. in Dresden, and of the editor, Geheimrat A.B. Meyer, to whom at this point I express my deep gratitude.

The maps were drawn by Dr M. Groll in Berlin, from the map of the Bismarck Archipelago in the Großer Deutscher kolonialatlas, which was provided by Herr Parkinson with amendments and modifications.

Finally I must state my thanks to the publishers, Herren Strecker & Schröder, for the willing cooperation they have given me in the editing, and particularly, in the production of the book.

Berlin, September 1907

B. Ankermann

xxxvii xxxviii

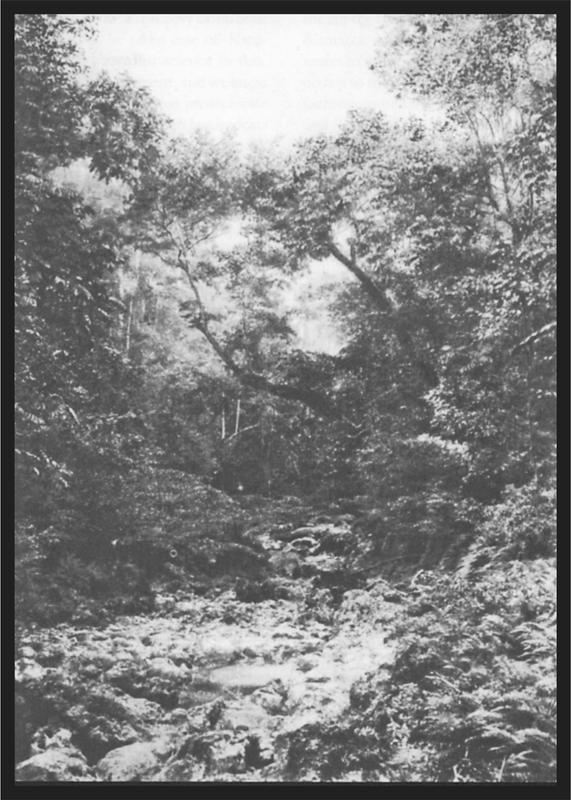

Plate 1 Gorge at Möwehafen. Fissure in a raised coral reef, widened by erosion