I

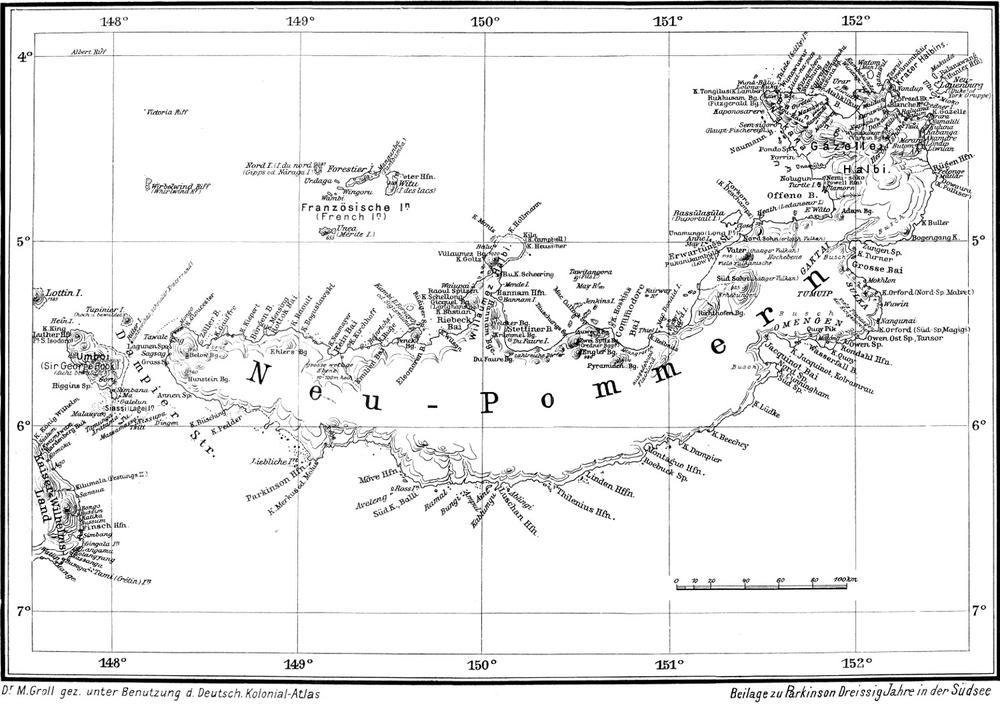

New Britain with the French Islands and the Duke of Yorks

1. The Land

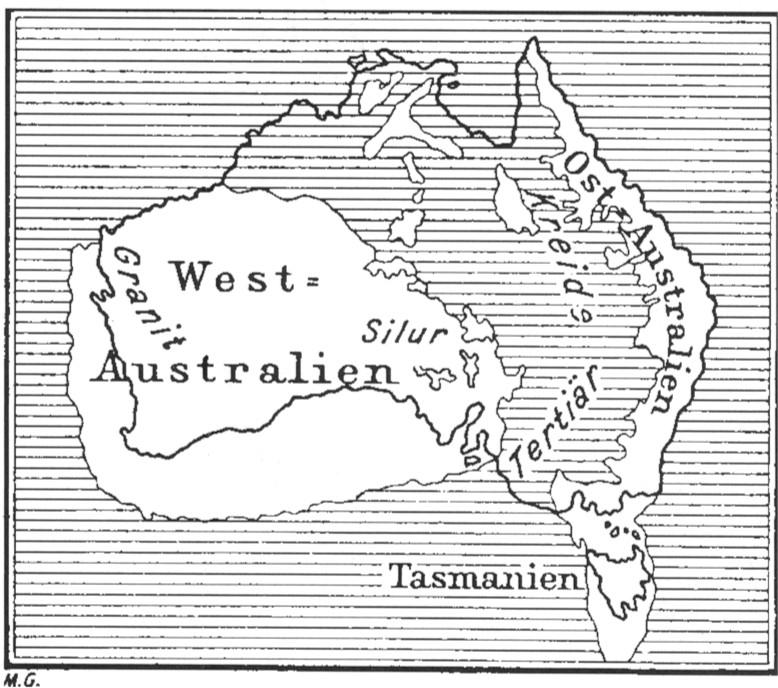

The main island of the Bismarck Archipelago is unquestionably the island of New Britain. From its northernmost point, Cape Stephens, it stretches first in a southerly direction about 100 kilometres to the isthmus that joins this northern part, the Gazelle Peninsula, to the main island. Then the land extends about 200 kilometres to the southwest to a second constriction between Jacquinot Bay to the south and Commodore Bay to the north. From there the rest of the island runs mainly westward, a distance of about 270 kilometres, the broad Willaumez Peninsula jutting out towards the north. The total length of the island is about 560 kilometres. The breadth is quite variable; from Cape Lambert in the north-west as far as Cape Gazelle in the north-east the breadth is about 90 kilometres, while the isthmus that joins the peninsula to the main island would not be much more than 20 kilometres. The greatest breadth of the island occurs between the northernmost point of Willaumez Peninsula and South Cape, approximately 145 kilometres; a narrower part is found further on, between Jacquinot Bay and the north coast, about 50 kilometres. The surface area of the island and the small neighbouring groups is approximately 34,000 square kilometres; that is, about as much as the Grand Duchy of Baden and the Kingdom of Württemburg put together. The preceding measurements make no claim to absolute accuracy. A precise survey of the island was undertaken by the Imperial Navy a few years ago, and at the conclusion other values were most probably provided, since the earlier measurements and cartographical representations which form the basis of the values given here are admittedly very superficial and imperfect.

As far as we know, two main geological formations appear to predominate in the island’s structure, namely volcanic lava and coral formations; the latter raised high above sea level by the strength of the volcanic activity. Volcanic action continues today, although compared with earlier times it has undoubtedly declined significantly. Along the entire line from Cape Gloucester in the west to Cape Stephens in the north-west, there stretches a number of active volcanoes arranged in groups, and numerous extinct craters bear witness to the strength of the subterranean fire. Earthquakes are not infrequent today, although they cause less trouble; they are, however, still strong enough to arouse feelings of anxiety at their onset, and to be a reminder that one day they could bring about an unexpected, calamitous catastrophe, against which people are powerless. Several of the earthquakes that I have experienced during my many years’ stay in the archipelago would have been, in spite of their short duration, strong enough to devastate a European town thoroughly; the solid stone buildings at home would have collapsed inwards, while out here the natives’ huts and the settlers’ houses built of wood indeed creak and groan in truly every joint, and thus shake so severely that standing upright actually becomes extremely difficult, yet because of their style of construction, they do not collapse.

The most well-known area up to now is the northern part of the island, the Gazelle Peninsula; that is, we know fairly thoroughly only the region lying east, north and north-west from Vunakokor (Varzinberg). In recent years the high mountain range forming the western edge of the peninsula, usually called the Baining Mountains, is starting to become better known to us, thanks to the Catholic mission that has been established there. Beyond Vunakokor the area really is still completely unexplored, and for the remainder of the island our total knowledge shrinks to the coastal strip and the offshore islands, and here too we must regretfully concede that our knowledge is only sketchy.

However, every excursion, no matter how small, into these unknown regions, steadily brings us new and unexpected discoveries and experiences. For later travellers and explorers there will still remain much to do, and a series of interesting surprises certainly lies ahead of them. Over the years the basic survey of the island by the Imperial Navy will also bring us much information about the inhabitants. 2

As the mail steamer from Australia approaches the coast of New Britain, the eye picks up, chiefly far to the north-west and west, hazy blue mountains whose peaks are frequently covered in thick cloud. Gradually the outlines become sharper; the high Cape Orford with the mountain range behind stands out clearly, and also to the north-east the outlines of high mountains stand out against the skyline – the highlands of southern New Ireland. Soon St George’s Channel is clearly marked by the high land of New Britain in the west and New Ireland to the east. The direction of this inlet, roughly 35 kilometres wide at the middle, is approximately along a north-south line. On pre-1890 charts navigators were warned of unknown dangers there; we have known for a very long time now that the navigable waters of St George’s Channel are deep and without any hindrance to navigation, although from time to time, depending on the prevailing wind, a strong current sets through the strait, alternating between northerly and southerly, against which sailing ships are almost powerless.

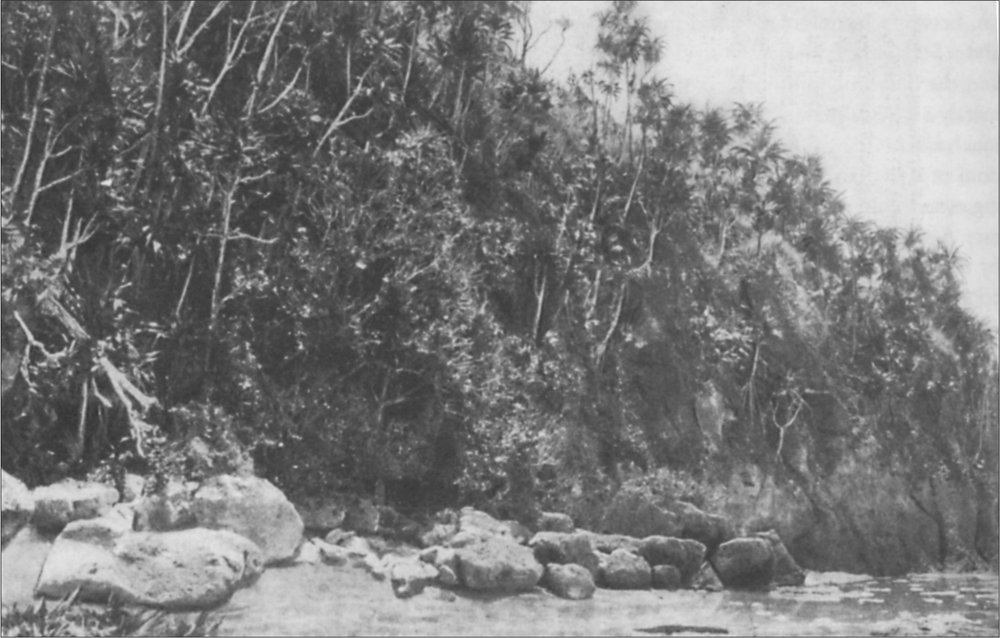

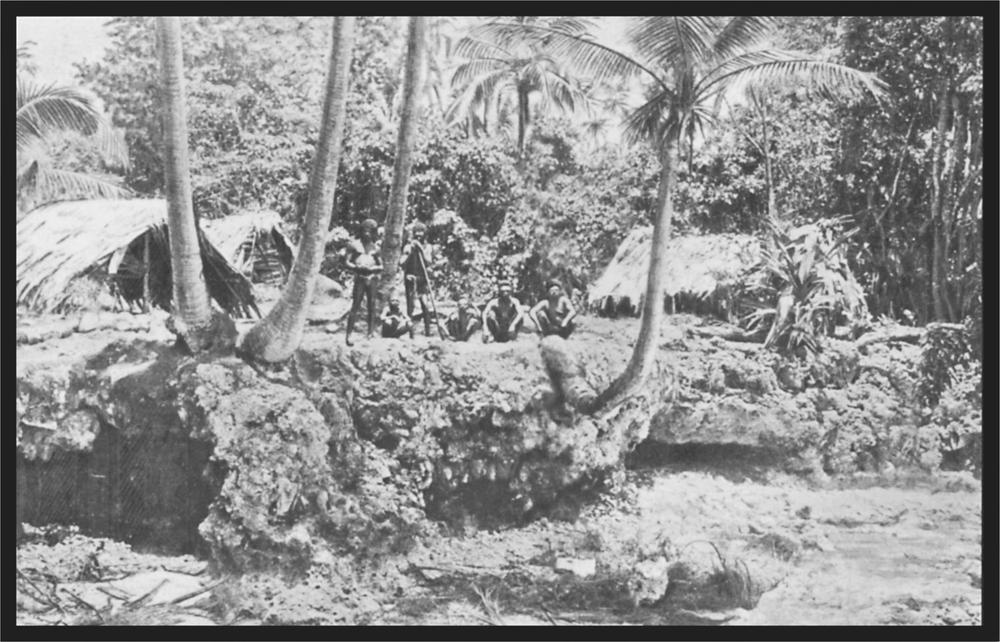

Fig. 1 Coral limestone rock, coast of St George’s Channel

The east coast of the Gazelle Peninsula presents itself to the beholder from St George’s Channel as a high, mountainous land. The isthmus that forms the connection with the main island is significantly lower; it is formed from raised coral limestone. The same formation predominates on the east coast of the main island, with outcrops of volcanic rock inland. The mountains in the south of the peninsula are wooded throughout, rounded in form, with not very steep slopes, so that they seem well suited for establishing plantations. Numerous streams, large and small, furrow through the valleys, several of which cut deeply into the land. Into the small, Henry Reid Bay in the south of the peninsula flows quite a large stream, navigable by boats for a fair distance upstream from the mouth. The sea depth increases rapidly off the beach, and good anchorages are not available here. Henry Reid Bay is an exception, but even it offers a secure mooring only during a north-west wind.

As soon as Cape Palliser is passed, the scenery changes. To begin with, the mountains retreat somewhat and the slopes become more gentle; the uniform dark green of the tropical forest is interrupted by larger or smaller, grassy, pale-green shimmering fields, and the further north we go, the more these fields increase in extent, interrupted by patches of forest and traversed by deep, wooded ravines.

A little north of Cape Palliser lies a small bay, protected by an offshore coral reef with two small islets, and forming a good harbour even if only for small vessels. The natives call the place Mutlar and visit it occasionally to hunt turtles. A little north lies a small, concealed harbour, Rügenhafen (Putput to the natives), that I discovered in 1884 on a boat trip along the coast. The entrance is narrow, so that only one ship at a time can pass through; branches of the mighty forest trees, which extend from both sides over the narrow channel, brush the ship’s sides here and there with their foliage. Yet nowhere in the entrance is the water depth less than 13 metres, and in the basin which opens beyond this pass, a great number of vessels find room to anchor in depths of 11 to 12 metres. Vessels lie absolutely securely here, and since Rügenhafen and Mutlarhafen are the only safe harbours on the eastern side of the Gazelle Peninsula, they are certain to become of no lesser importance over the course of years when the establishment of plantations has opened up the hinterland. At present the shoreline still consists of a thick, tropical forest flora; nothing stirs on the surface of the crystal-clear basin, 3screeching cockatoos greet the visitor, and flocks of pigeons inhabit the treetops. Far and wide, deep, silent, forest tranquillity reigns, for the entire region is uninhabited; from time to time natives come from far away to exploit the abundance of fish in the harbour here.

About 4 kilometres north of Rügenhafen, a broad, deep valley cuts far into the land. Here is the mouth of one of the largest waterways of the peninsula, the Warangoi, which is named Karawat further inland. The fall is steep and the amount of water during the dry period of the year is not significant; in the rainy season it is transformed into a foaming, rushing, mountain torrent which can only be navigated with great difficulty upstream as well as downstream. Years ago, in the company of Bishop Couppé and the surveyor Herr Rocholl, I travelled the river by boat from the mouth to a point just south of Vunakokor. We covered this distance in a four-day journey, not without great exertion. From time to time the boats had to be dragged over shallow sandbanks, then fallen, mighty forest trees barred the way, from bank to bank, forming a barrier over which the pent-up water rushed, foaming and thundering; here and there were open stretches with deeper water so that paddles could be used, but even here we proceeded only slowly and with the utmost effort, for the current was a very strong one. The river ran in a bed that, with many bends, twined itself sometimes between steep banks that jutted out like bastions, and sometimes through reedy lowlands. Here and there mighty trees arched a leafy canopy over the surface of the water, or slender bamboo canes, united into mighty stands, stretched their fine, delicate foliage far over the banks, and between them shone the pale, columnar trunks of the imposing eucalyptus trees (Eucalyptus naudiniana), characteristic of the vegetation of New Britain.

The scenery is quite magnificent, and changes at each of the numerous bends, so that the four days during which we advanced upstream seemed to us to pass rapidly. But even more rapid was the return journey, for the distance that we had covered upstream in four days of hard work, we accomplished downstream in a four-hour journey. In a headlong rush our three boats raced downstream, driven solely by the strong current which was further enhanced by a torrential downpour that caught us unawares at our last camp site. The paddlers sat there helplessly; the entire effort fell on the helmsman, who had to maintain a steady eye and powerful arms to dodge huge boulders or tree stumps and skirt steep rocky banks, in guiding our fragile craft safely downstream during the raging journey. To be sure, every one of us was relieved when the thundering of the breakers proclaimed that the mouth of the Warangoi was nearby and our wild journey was at an end.

At the river mouth the New Guinea Company had set up a sawmill a few years ago, to exploit the abundant stands of timber, especially the valuable stand of eucalyptus.

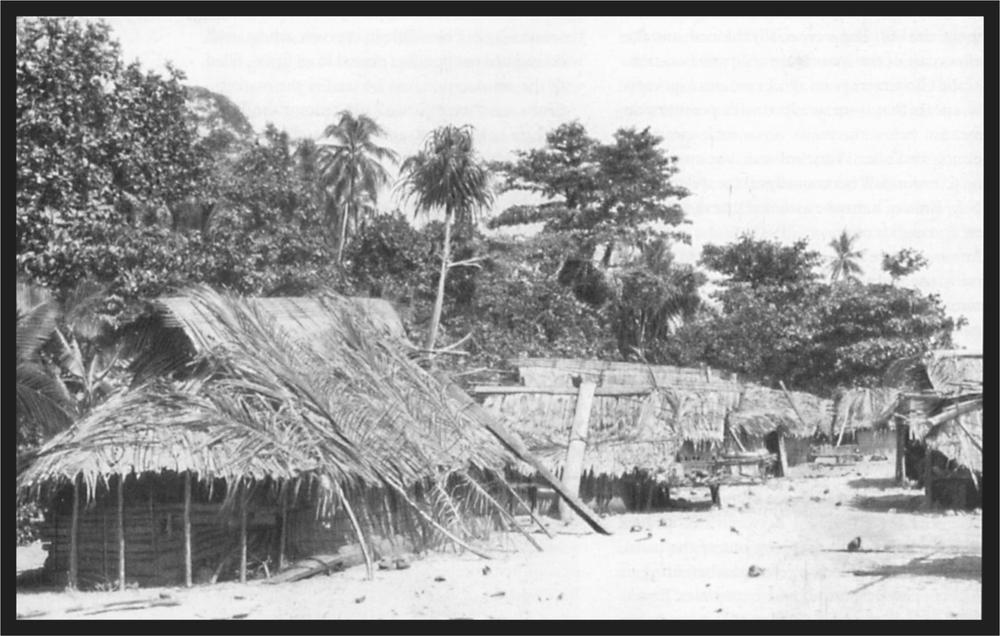

Onward from the mouth of the Warangoi the landscape creates an increasingly pleasing and agreeable impression. The coconut groves become thicker, in places forming a dense border to the beach, and on the hills their tops project above the forest; extensive cultivated fields reveal the presence of people, whose grass-covered huts peep out of the greenery on the beach, and also on the high plateau and its slopes.

Inland the peak of Vunakokor, or Varzinberg, rises approximately 600 metres above the land, and ascending clouds of smoke, large clearings, as well as other signs, proclaim that population numbers cannot be small.

As we penetrate further northwards into the channel, initially we notice individual treetops looming like small black mounds on the northern horizon; they increase rapidly, and form a seemingly low, continuous wall; soon, however, we distinguish tree trunks and treetops, and then the white sandy beach and the shining foam of the surf on the coral reef; nearer still we recognise individual islands, the islands of the Duke of York group.

We round a low, wooded spur, Cape Gazelle, and there extending before us is a portion of the north coast of the Gazelle Peninsula; in the background the deep Blanche Bay towered over by the mountains of the Mother peninsula. On the right, lie two small islets, the Credner Islands; they are thickly wooded, and rise only a few metres above sea level. As a consequence of their isolated position, they were proposed by the administration as a quarantine station, and one could only with great difficulty find a more suitable site.

In the channel, signs of white settlement are sparse, but from Cape Gazelle onwards they increase rapidly. A few kilometres westward, at the small bay of Kabakaul, brightly shining, corrugated iron-roofed dwellings and warehouses become visible, and around about, extensive clearings and the beginnings of plantations betray the presence of white settlers. A little further on still, the number of buildings grows quickly; from the shore far inland stretch palm plantations; dead straight and at regular intervals, the rows of planted coconut palms march over mountains and through valleys; the virgin forest and grassy plains have long disappeared, and far along the shore, as inland, the eye perceives palm top upon palm top. The stately settlement of the Catholic Mission of the Sacred Heart with a twin-towered chapel and a number of single- and multi-storey large dwellings and school buildings comes next into view. The settlement, which was named Vunapope (foundation or root of the papacy) by the missionaries, is at the same time the seat of the Catholic bishop of the Diocese of New Britain. 45

Map 1 The Bismarck Archipelago

6A little beyond the mission station, actually bordering it, is the Herbertshöhe plantation of the New Guinea Company with the settlement of the same name, and here also is the seat of the imperial administration. The stately home of the imperial governor, on a dominating hill, towers over a large number of dwellings, offices and warehouses that belong partly to the New Guinea Company and partly to the imperial administration, and following this are the extensive areas of the great Ralum plantation, which stretch along the beach towards Schulze Point, with their various annexes and plantation buildings.

Off Herbertshöhe one almost always finds a larger or smaller assembly of ships; beside stately German warships and the packet boats of Norddeutsche Lloyd, lie larger and smaller vessels belonging to the colony’s merchant and plantation firms, which maintain settlements on the various islands of the archipelago. A suitable harbour is not, however, available, yet the spacious roadstead is fairly protected and offers excellent anchor ground with moderate depth.

If we go ashore, we find broad, well-maintained roads which have been constructed, not without great cost, in part by the imperial administration and in part by the plantation owners. These roads lead inland from Herbertshöhe, and connect the individual plantation stations with their central bases and with one another; however, they also lead out over the plantation region, and year by year the roading system is further improved and extended. The young colony stands in other ways on the path of progress, as is revealed by a stately, two-storey courthouse, spacious hotels, narrow gauge railways, telephone wires, and so on.

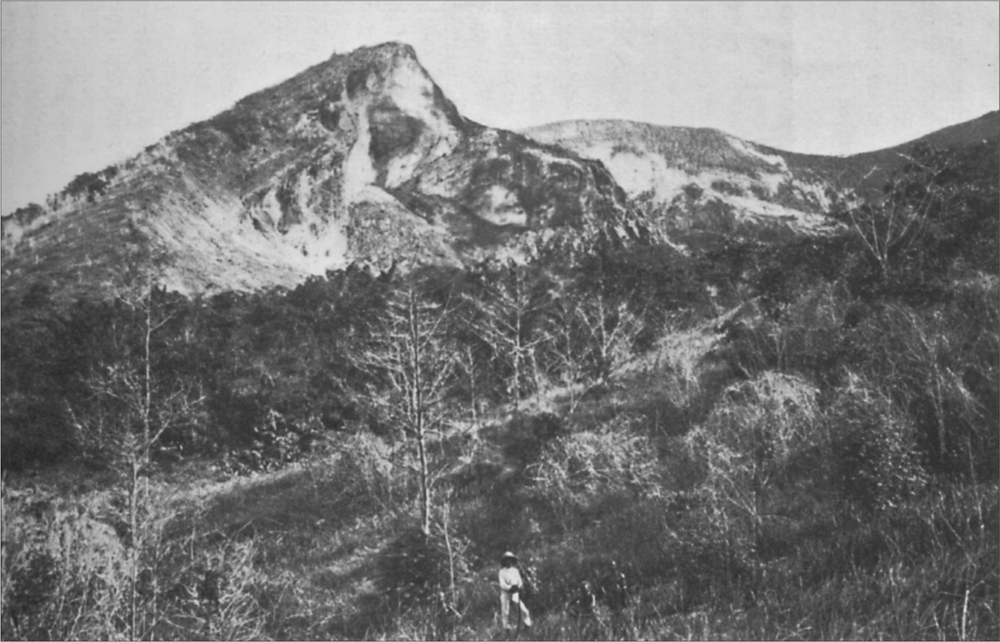

Blanche Bay itself begins about 8 kilometres west of Herbertshöhe. It is bounded to the west and south by a high plateau that slopes steeply to the beach; in the north and north-east the boundary is the volcanic peninsula with the three extinct volcanoes North Daughter (Tavanumbattir or Balnatoman), Mother (Kombiu) and South Daughter (Turanguna). At the foot of Mother rise a further two low craters, the more northerly of which is extinct and covered with vegetation right to the floor, while the southern one with its adjacent crater Kaije is still mildly active. The inwardly collapsed crater rim allows a view right inside; in a ditch-like depression in its floor is a ponding of water, and on the sides, rising sulphur vapour has covered the stones here and there with yellow sulphur crystals. Kaije is a smaller crater on the rim of the above-mentioned one, and in 1878 was still in full activity; since then a quiet period has set in, and it is apparently becoming extinct, although in odd places hot sulphur vapour wells up between the lava blocks and the rocks feel hot. When I settled in the Bismarck Archipelago in 1882, one of my first trips was to the peak, or more precisely to the crater rim, of Kaije. At that time, numerous traces of the most recent eruption were still evident. Scorched tree trunks surrounded the foot and the lower half of the mountain, nowhere was there a green stalk visible, the volcano loomed black and barren over its surroundings. Only with the greatest care could one walk on the inner slope of the crater, the intense heat of the rock, and the rising, foulsmelling hydrogen sulphide gas quickly drove the visitor back to the windward crater wall. Today the sides of the mountain are almost entirely covered with vegetation, even the inner walls of the crater are beginning to be covered with pale green, and the rock has already cooled to the extent that one can walk about inside the crater without burning the soles of one’s boots. In the depths the volcanic hearth is still not yet extinguished, as demonstrated among other things by the numerous hot sulphur springs that pour from the foot of the volcano into Blanche Bay. One of these, situated beside the Hernsheim farm, Rabaul, has recently been used successfully for treating rheumatic pains.

From the peak of Mother, approximately 770 metres, which can be reached in a climb of about three hours from the beach, the visitor is offered a vista of incomparable beauty. Within a narrow field of view lie the sides of the mountain with the huge, deep gullies to the north, and with the maze of forested ravines and precipices. The highest peak itself, with the slight depression, the remains of the former crater, is overgrown with rank grass. To the south we peer into the smaller craters described above, and gaze upon the wooded South Daughter, approximately 530 metres tall.

Out of the clear waters of Blanche Bay rises the small, flat island of Matupi, and between the greenery of the coconut palms peep the corrugated iron roofs of the Hernsheim trading settlement. The ships that lie at anchor in the small safe harbour of Matupi look like miniatures. Beyond Matupi opens the broad basin of Blanche Bay with its dark blue water, above which tower two isolated masses of rock which, because of their shape, have been given the name the Beehives. Not far from the opposite shore, in the southern half of the basin, we notice a flat island about as large as the island of Matupi; this is Vulcan Island which in 1878, at the same time as the eruption of Kaije, rose from the depths of the sea, and is today already covered with vegetation. Seen from our vantage point, Blanche Bay gives the overall impression of being an earlier mighty crater, with an opening to the east through which the sea has broken. Around it the shore slopes steeply, in many places almost vertically, to the sea; especially in the southern half of the bay where the sea floor also drops steeply into the 7depths, and consequently no anchor grounds are available here. The shores of the inner, northern part of the bay, Simpson Harbour, are less steep. There is also a lesser depth of water, and because of its spaciousness and sheltered position, as well as on account of the totally safe entrance, this would appear to be suitable as a fleet station, the more so as on its shores extensive flat land is available for the erection of coal depots, buildings and other installations. The Bremen Norddeutsche Lloyd has recently established a large installation here, which will serve as the main base for the company’s steamers travelling in the archipelago.

Fig. 2 Kaije volcano overlooking Blanche Bay

Wandering further south, the eye then glimpses the broad, high plateau of the northern Gazelle Peninsula from which Vunakokor rises like an isolated cone. This part of the peninsula especially, when seen from our high vantage point, gives the perfect impression of an English park, with green lawns, isolated trees, small and large copses, and extensive woodlands. In the south and west this giant park is enclosed by high, shimmering blue mountains, the Baining Mountains.

Yet the scenic beauties are still not exhausted. If we turn to the east, before us lie both small Credner Islands (Balakuwor and Nanuk), also named the big and the little Pigeon Islands because of the pigeons that occasionally roost there. A little further on we espy the entire Duke of York group in a bird’s eye view; we can clearly distinguish the narrow arms of the sea that separate the individual islands, and wind like irridescent silver strips through the dark portions of land. Away over on the far side of St George’s Channel, like a spectacular backdrop to a magnificent landscape, rise the mighty mountains of New Ireland, to disappear as far to the south as to the north, in the bluish haze.

Once more, the picture changes when we gaze towards the west. The entire north coast of the peninsula lies at our feet with its offshore islands, the most significant of which is the extinct, wildly rugged crater Uatom or Watom (Man Island). Extensive coconut stands stretch from the beach up to the plateau, and between these, rising columns of smoke reveal the presence of dense population. Regular plantation establishment is just developing in this area, and only merchants and missionaries dwell at short distances along the shore. Actual harbours are not available here, and the anchorages, which according to the site offer greater or lesser security, are inferior. The broad bay which cuts into the land further westwards is Weberhafen; adjoining it, a splendid, wooded, well watered plain, running to the south and south-east, extends right behind Vunakokor, bordered in the west and south by the gently rising foothills of the Baining Mountains. This plain is expected in time to become of high economic significance, for the soil is deeper and better here than on the pumice plateau north of Vunakokor, where only coconut palms will be able to be cultivated successfully. The imperial 8administration is also endeavouring to connect this part of the peninsula by a road system with the seat of government in Herbertshöhe and the main landing place of ships there, since Weberhafen too offers no absolute protection.

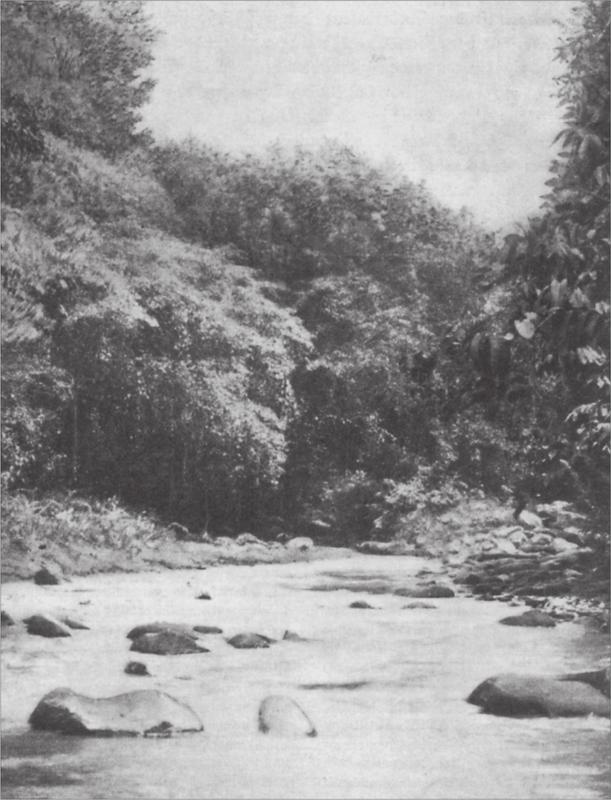

Fig. 3 River valley of the Karo, Baining Mountains

Beyond the plain the high, rugged Baining Mountains cut off the view.

The preceding description offers only a slight impression of the magnificent view. In the wonderful combination of land and sea I know of only one view that can compare, that from the peak of Vesuvius. However, when the image that is offered to the eye from the crater rim of Vesuvius is compared with a landscape sketched in bold strokes, I would similarly compare the view from the peak of Mother with one of those prize exhibits in which the artist has reproduced each small detail with love and care. This is conveyed by the wonderful transparency of the air: at a distance where objects seen from Vesuvius are already disappearing into indefinite outlines, from Mother in a favourable light we can still perceive very clearly the feathery crowns of the palms on distant heights, or the trunks of forest trees on the steeply sloping mountain sides.

To the west of Weberhafen the Baining Mountains approach the beach ever more closely, and the flat shore margin becomes narrower, finally disappearing completely after the small island of Masava. This islet lies on a coral reef, and with this 9and the coast of the peninsula it forms a small, fairly safe harbour for smaller vessels. Close by lies a second small island called Masikonápuka, today still densely populated. Both islets were, right up until a short time ago, a type of stronghold from which the inhabitants made their raids, especially on the Baining Mountains, partly to capture slaves who were then traded on further to the east, and partly to seize virua; that is, human flesh. These events are now understood to be dying out as a result of the influence of the Catholic mission and the imperial administration.

Plate 2 Robert Koch Spring on the Willaumez Peninsula

From both previously mentioned islands onwards, the Baining Mountains come right down to the shore and rapidly rise to a significant height. Fertile valleys, through which foaming brooks flow, lie scattered among the mountains; for example, the valley of the Karo stream with its cascades and waterfalls. Inland about 8 kilometres from the beach the Catholic mission station of St Paul lies as a temporary, forward post, in a charming hollow surrounded by high, forest-crowned mountains.1

The character of the coastline does not change until Cape Lambert (Tongilus), the north-western corner of the Gazelle Peninsula. Before we reach here, however, we pass a group of small, uninhabited islands, the Scilly Islands (Talele). Once past the cape, we notice that the Baining Mountains, falling steeply right to the shore, appear as a coastal range that continues in a south-easterly direction. The mountains, soaring to a height of about 1,500 metres are wooded right up to the peaks. Out of the leafy green, waterfalls shimmer, and fairly full streams pour into the sea. The most significant of these watercourses, the Toriu (Holmes River) runs into the sea about 55 kilometres south-east of Cape Lambert. Here in recent years, the Catholic mission has established a steam sawmill which is at the forefront as quite the furthest advanced outpost of colonisation on the Gazelle Peninsula.

From the mouth of the Toriu onwards, the mountains gradually retreat, and the direction of the range which was, up until now southeasterly, alters and takes a more easterly course. This eastwards-extending range is apparently split from the mountain block in the north-west by a deep valley basin. From the peak of Vunakokor, and from Open Bay, this depression is clearly visible. Our knowledge of this mountainous district, although it lies not even 30 kilometres south of Herbertshöhe, is, however, still totally nonexistent; we do not even know whether the population of this mountain range is identical with the people of the north-western range, or whether one tribe differs significantly from the other.

From Weberhafen on to Cape Lambert and further along the coast from there, the sea voyage is quite dangerous, because of the many offshore coral reefs and sandbanks. However, the excellent annual surveys by HIMS Möwe are eliminating a great proportion of the dangers; however, coastal voyaging here still requires the greatest care and attention. Anchorages are available here and there along the coast, but only one single good harbour offers excellent protection. This is Powell Harbour (Tava na tangir), somewhat north of the isthmus.

10It is deep and spacious, and protected against all winds; in the inner corner flows a quite significant stream which is navigable by boat for a distance inland. The shores of the harbour, however, are swampy and covered with extensive mangrove forest, but with increasing cultivation of the extensive hinterland, this problem too might be overcome.

Fig. 4 Waterfall in a neighbouring valley of the Karo, Baining Mountains

If I have described the Gazelle Peninsula in some detail in the preceding pages, it is because this part of New Britain is by far the most important on the island; I would even go so far as to say the most important part of the entire Bismarck Archipelago. The Gazelle Peninsula flourishes economically year by year, and will maintain its importance in this direction for many years to come. Through its central position, it is eminently suitable for serving as a starting point for cultural undertakings in other parts of the archipelago, and its harbours form important support bases for sea travel. The significance of the roadstead at Herbertshöhe and the small harbour of Matupi, as well as Simpson Harbour, has been growing for years. Imaginary dangers for shipping, designated on earlier charts of this region, caused navigators to give it a wide berth. Through the Imperial Navy’s reconnoitering, however, it has turned out that the greatest part of the alleged dangers do not exist, and since the archipelago is situated on the direct route between Australia and East Asia, each year more and more ships decide to take this closer route rather than going through the dangerous Torres Strait, full of reefs and other obstacles to shipping. Coal depots on the island of Matupi form an important supply point for steam traffic on this leg. This traffic has risen from year to year, in proportion to the expansion of the colony and with the growth of the young Australian confederation. From the recent population census one may assume that in about 100 years Australia will have a population of around 30 million people. This combined with the enormous traffic with East Asia, which is likewise constantly increasing in significance, must definitely have a beneficial effect on the Bismarck Archipelago. New, easily accessible trading areas for tropical products will be created, and the archipelago, within a few days’ travel of Australia, will be in a position to cover a great part of these requirements.

Today, all this still lies in the distant future, but from one decade to another conditions change for the better. In 1882 traffic with the outside world was limited to the voyages of several small sailing ships, which the resident firms retained for their trading undertakings; from time to time, at long intervals a larger sailing ship also appeared, to ship out the assembled products; warships occasionally called in and were only too happy when they could steam out again. Postal connections with Australia occurred three or four times a year. All of this has already changed. Regularly voyaging saloon steamers of Bremen Lloyd and an Australian line take the mail and freight between the archipelago, Sydney, Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan; settlers and settlements increase, and the import of wares, like the export of 11colonial products, yield higher values year by year.

In spite of this, the German spirit of enterprise which at other times turned eagerly towards all newly opened-up regions of the world, has so far denied the islands of the Bismarck Archipelago the attention that they merit so highly, in spite of all the favourable circumstances. The reason for this is in part the superficial and inaccurate knowledge of the archipelago, which prevails in all circles of German society, and partly the bad experiences that the Berlin New Guinea Company had gone through years ago in Kaiser Wilhelmsland. The Protectorate of the New Guinea Company had almost always been mentioned in conjunction with sad and disheartening news, and even rosecoloured portrayals like those of Dr Finsch and more especially those of Herr Hugo Zöller, were unable to blot out the painful impression induced by the incessant bad news from the protectorate. Since the Bismarck Archipelago was included in the encompassing title, ‘Protectorate of the New Guinea Company’, the evil reputation of the German part of New Guinea had consequently extended to the island region as well, an inference as illogical as it was unfounded, although certainly excusable in view of the superficial knowledge of our most important South Sea colony.

The plantations of the Gazelle Peninsula consist almost exclusively of coconut palms. The long-fibre, silky type of cotton was produced as a by-product years ago and still is to a limited extent today, appearing on the market as Sea Island Cotton; however, since cotton prices have fallen, this secondary cultivation is dying out. In the area where the larger plantations are currently found, on the high plateau stretching southwards from the shore up to Vunakokor, other products would scarcely yield a remunerative profit. The thin layer of humus which covers the pumice layers from earlier volcanic eruptions is insufficient for other cultivation requiring a deep, heavy soil; for example, cocoa and coffee. These have found a soil suitable to them on the eastern and southern slopes and in the valleys of the Baining Mountains, and in the extensive region that stretches from Weberhafen to Vunakokor and beyond. In these regions there await many thousands of hectares of profitable cultivation; stretches just as extensive are accessible for coconut cultivation. Beyond Vunakokor the population is sparse, and one does not run the risk of troubling or restricting the natives in their settlements.

The southern part of New Britain adjacent to the Gazelle Peninsula appears to be of lesser significance, at least as far as our current acquaintance with this region justifies an opinion of it. This part, having the same surface area as the Gazelle Peninsula, to which it is connected by a hilly isthmus, forms roughly a square with sides of 80 kilometres, including Duportail Island on the north-west corner. In the south-west a second constriction links this part of the island with the western part of New Britain. The entire eastern, northern and southern flanks slope steeply to the sea and have no absolutely safe anchorage. In Jacquinot Bay in the south, good anchorage is found during the season of the nor’-westers, whereas the harbour is only partially protected during the period of the south-east wind.

The entire central part of this section consists of a high mountain range which comes right to the shore almost everywhere, showing several flat or gently rising plateaux predominantly in the northeast. The western flank consists of a series of moderately high volcanoes whose three highest peaks are found on the north-west corner: the volcanoes North Son (Golau) about 600 metres high, Father (Ulavun) some 2,000 metres high, and South Son (Bamus) about 1,600 metres high. The offshore island, Duportail (Namisoko or Lolobau), is also volcanic. Golau is extinct; on the other hand Ulavun and Bamus, and one crater on Namisoko are still active. From time to time powerful eruptions occur; their glow is visible at night over a wide area. In 1898 I was able to witness such an eruption quite clearly, south-west of Sandwich Island;2 that is, at a distance of about 210 kilometres from the eruption site. The following year, as a result of an eruption by Ulavun, a broad strip of mud was visible, extending from the peak to beach level; in the lower, wooded zone of the mountain the devastation from this eruption was seen most clearly; here the vegetation had been totally ravaged by the hot mud: barren, dead tree trunks protruded from the already dried-up bed of mud, and in amongst this, huge lumps of rock debris, broken-off tree trunks, and so on, had piled up into insurmountable barriers. In 1896 [sic] no trace of this eruption remained. Further south of Bamus still other craters rise up along the coast, some active, others extinct, but of far smaller size and significance. This series of volcanoes, which takes up the entire western shore of Cape Quass, is separated from the central range by a deep depression which can be clearly observed from Open Bay to the north, and cuts deeply inland to the south-south-west. This depression receives the runoff from the series of volcanoes in the west and from the high mountain chain to the east; its confluence forms a rushing mountain torrent flowing into the so-called Hixon Bay, named Langalanga by the natives.

Of this part of the island too, we still really know very little. Seen from Wide Bay, the land seems to be well-populated from the beach to the mountain range, if we can draw any conclusion on the population size from the number and extent of the cultivations laid out everywhere, and from the rising columns of smoke. The steep plunge to the Langalanga valley in the west seems less populated.

12On the beach flats at the foot of the western side of the series of volcanoes, quite a large number of villages have been established; their inhabitants were, however, decimated by smallpox in 1897.

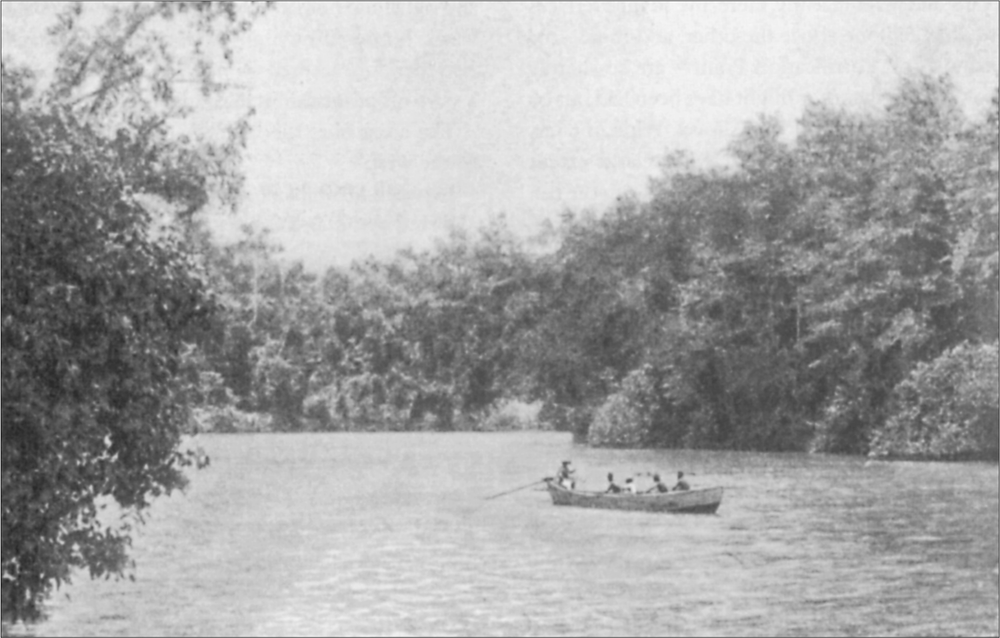

Fig. 5 Möwehafen

The northern shore towards Open Bay is named Nakanai by the inhabitants of the north of the Gazelle Peninsula. Years ago there were a few pitiful villages here, but these had disappeared by 1900. The coastline at the foot of the volcano is apparently called Wittau.

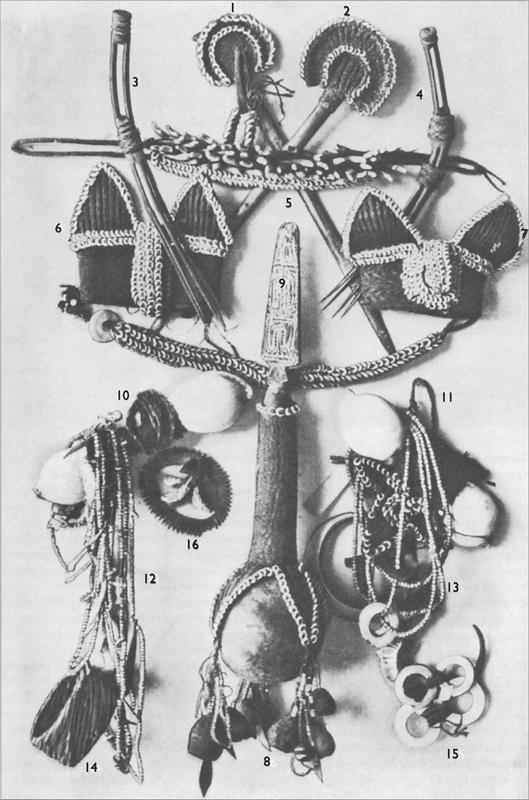

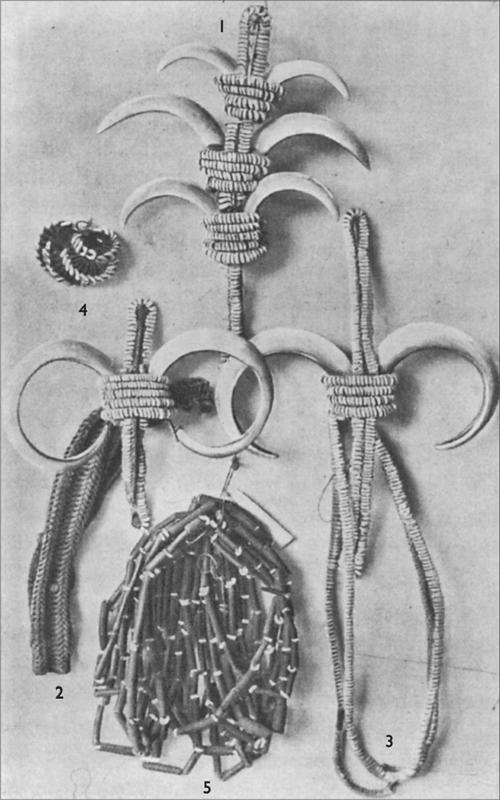

The only venture into the interior was undertaken in 1897 by Dr Hahl, Dr Danneil and Father Rascher. These three set out into the hinterland from the then-existing village of Watu on Open Bay, and after an arduous six-hour trek reached a village in the mountains. They were successful in establishing amicable relations with the natives, and, from their accounts and from the ethnographic articles brought back, which are the same as those that I have seen or bartered for on the eastern side, I have come to the conclusion that this population belongs to the same tribe that inhabits the eastern and southern coasts and the high mountain ranges, while the Nakanai and Wittau people belong to another tribe. The mountain inhabitants with whom the above-mentioned gentlemen came into contact were called Paleawe by the Nakanai people.

Economically, it seems that not a lot can be expected from this part of the island. It may be then that the Langalanga valley and the plains at the foot of the volcanoes should be given over to cultivation. In recent years there has been some success in establishing friendly exchanges with the natives of the northern and eastern coasts, with the result that a number of them were recruited as plantation workers. From the dense population there, one might anticipate obtaining a portion of the workers employed on the Gazelle Peninsula plantations in future. The Catholic mission is planning to set up a station there very shortly, and we may then hope to get to know these, in many ways highly interesting people, more closely.

The subsequent part of the island, between Jacquinot and Montague bays in the south and Cape Quass and Commodore Bay in the north, is on average about 50 kilometres wide. Here too the land is mountainous, and only on the northern side are larger, flat and gently rising stretches of outstanding soil condition available, mostly on the shore, enclosed by a border of mangrove trees.

We have now reached the large part of the island stretching to the west, with the Willaumez Peninsula extending northwards. The interior of this significant and interesting stretch of land is as good as totally unknown to us. The coasts have not yet been fully visited, but in the stretches explored thus far, a whole series of harbours have been identified on the southern side; a number of these must be designated as quite superb. On the stretch between the flat Cape Roebuck in the east and South Cape to the west, are, first of all, a number of smaller, sheltered harbours and anchorages, which form outstanding departure points for the cultivation of the stretches of land lying next to them as well as beyond. The latter exhibit overall the features of a gradually rising tableland upon which is based the not very high mountain range inland.

Offshore lie a number of small islands that show a terraced structure almost throughout. They are formed from coral limestone. Similar terraces are also to be observed on the coast of the main island, but these are frequently interrupted by watercourses and valleys, so that they do not appear so clearly here as on the small islands. Much further to the west, on the coast of Kaiser Wilhelmsland, this terrace formation comes into view particularly 13clearly and magnificently. Here, five to nine terraces are arranged one above the other, and these – for example, on Fortification Point – are so sharply pronounced that they might have been laid out by human hand with pick and shovel. While the terraces on Kaiser Wilhelmsland are to a large extent overgrown with grass, in New Britain both the terraces and their steeply sloping walls carry a lush forest vegetation.

Many of the islands are inhabited, and here, as on the coast of the main island, numerous, if not large, settlements are to be found. In the interior a more dense population seems to dwell, but we do not know much about that either.

A little westwards of the so-called South Cape (Cape Balli), north of the two small Ross Islands (Aveleng), lies a splendid harbour with several entrances, which was closely examined years ago by HIMS Möwe and has since then borne the name Möwehafen. It is formed from a series of three terraced islands which skirt the coast in such a way that, between coast and islands with the fringing coral reefs, a large basin is formed, offering ships of all sizes a totally safe anchorage, protected from all winds. Möwehafen is of paramount importance for the south coast of this part of the island: in future it will undoubtedly become the main trading centre for the western part of the island, as Blanche Bay is for the northern part of the island. A stream running into Möwehafen supplies superb drinking water throughout the year.

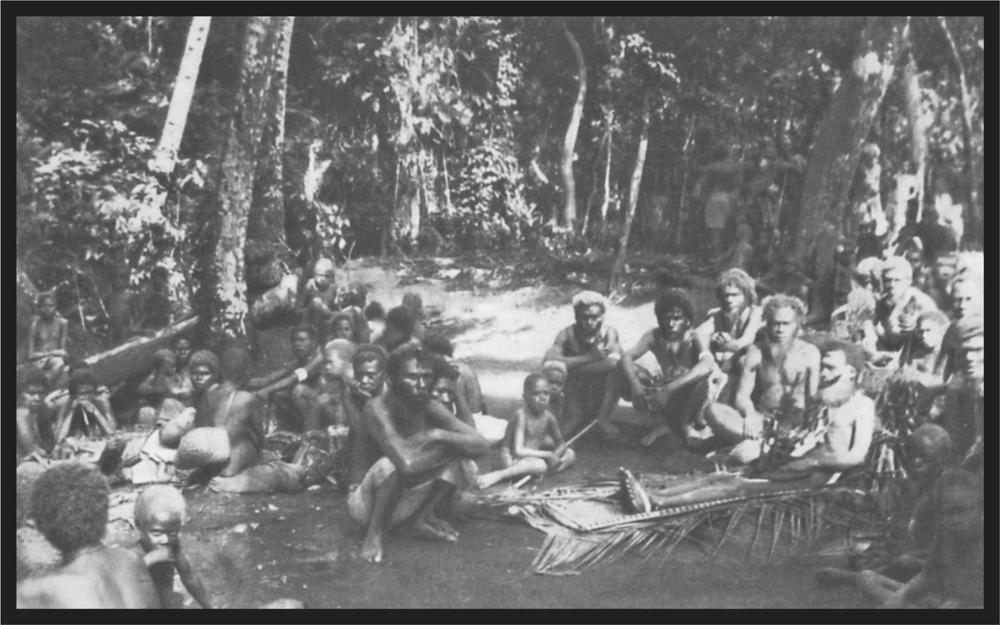

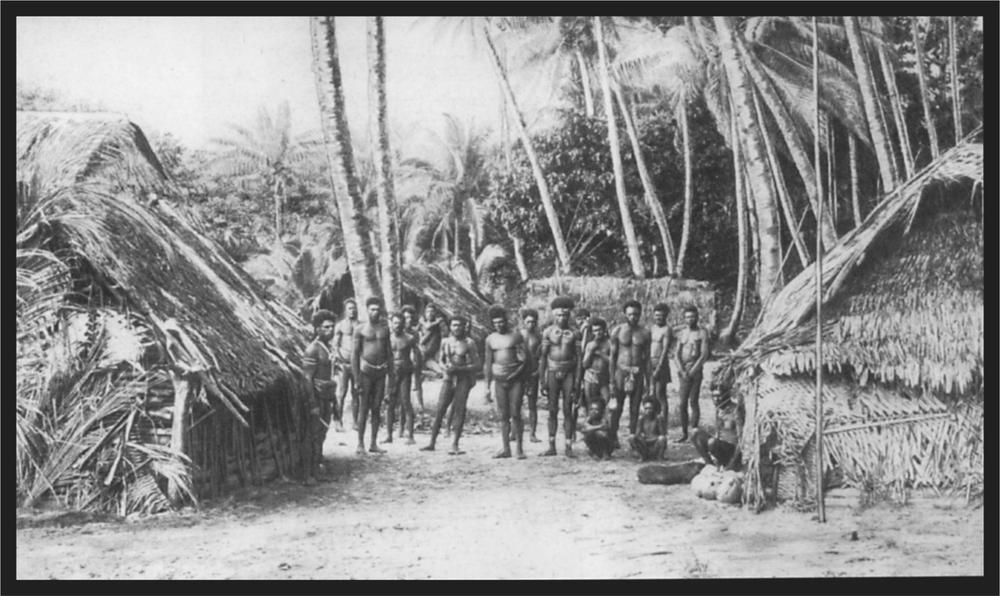

In 1896 I undertook a small excursion from Möwehafen that led me several kilometres inland. On a somewhat steeply rising path at an altitude of about 75 metres I and my companions came to a tableland, which bore signs of extensive, old, native cultivations. A well-trodden, broad path led inland, and following this we soon encountered great taro patches. The natives working on the cultivations promptly fled hastily into the protecting thickets at the sight of us; however, after several efforts we were able to entice the most stout-hearted out of their concealment. After initial communications had been established, still more natives joined us, until we were surrounded by about twenty of them, apparently the men working in the gardens. They led us to a small compound, comprising two huts, surrounded by a double palisade wall made of tree trunks. They indicated to us that they dwelt partly on the islands in the harbour and partly on the tableland, and after a while we heard drum signals from inland, a sign that there was a settlement there. We did not succeed in reaching it, however, although we followed the path leading there for a time and stumbled upon natives working. The soil was superb throughout, to which the large taro tubers grown in the cultivations bore ample witness. At several places I had a view over the tableland which apparently extended far to left and right, and only at a considerable distance inland was it bordered by high mountains. Möwehafen also therefore seemed to me to be very suitable as a start-off point for establishing agriculture.

The coast bore the same characteristics further to the west.

Between Möwehafen and Cape Merkus (Mulus) assorted good anchorages are available. Also, a number of quite significant watercourses empty here; the Pulié River, which pours into the sea not far from Cape Merkus, is of special importance because, in contrast with the general rule with local rivers, it has no bar beyond its mouth; this yields a water depth of 5 to 6 metres. Inside the mouth the river is 7 to 10 metres deep, and can be navigated for at least 20 kilometres inland by steamers up to 300 tonnes. Even in rainy times the current is insignificant, and the water never seems to overflow its banks. The soil on both sides of the river is superb, and appears to form a river flat, extending far inland.

Herr von Schleinitz, who navigated this river years ago as the first European, says about it: ‘This river, besides the Augusta River (Kaiser Wilhelmsland), is the most significant of all the rivers discovered and explored up till now, and surpasses even the Ottilien River (Ramu) with regard to navigation.’ I agree wholeheartedly with this opinion.

The forest on both banks of the river is certainly dense, but cannot be compared with almost impenetrable virgin forest and its giant trees. Deforestation would incur neither great difficulty nor expense, and the soil must, in my opinion, be suitable for every kind of tropical agriculture. I saw great stretches, that by clearing of the forest could easily be transformed into cocoa plantations. Also, the river flats do not bear the character of an absolute, low-lying area, but are sprinkled with small hills and ranges of hills, which seem eminently suitable for the establishment of settlements. The necessary construction materials could be sawn on the spot using water power without costly outlay, and I would, without exaggeration, designate the bank of this river as the most suitable site for settlement in the entire Bismarck Archipelago.

South-west of Cape Merkus lies a small, inhabited island group, ‘Liebliche Inseln’ on the maps. They are fairly densely covered with palms, and a few years ago the firm of E.E. Forsayth set up a small station here for the purpose of planting, but more especially for establishing friendly relations with the local natives, and persuading them to hire themselves out as plantation labourers. Gradually this undertaking seems on the way to being crowned with success, for natives from Cape Merkus right up to South Cape have gradually lost their fear of white people, and already work in the Ralum plantation of the above-mentioned firm.

From Cape Merkus onwards, the coast is fringed 14with numerous islets, and, between these and the mainland, lies a splendid, protected harbour. Here too the coast offers numerous starting points for setting up cultivation, although the rivers are only of minor significance; for the most part they efficiently drain the system of high volcanic mountains, which start here and climb to imposing heights towards the west. The mountain range nears the coast the further westwards we go, and finally forms moderately wooded bluffs, 30 to 80 metres high.

Fig. 6 Party on the Pulié River, 10 kilometres from the mouth

The western tip of New Britain is surmounted by two high volcanoes, the mountains Below and Hunstein. Both of these volcanoes, the former of which is still active, together with a number of smaller volcanoes (some active, some extinct), form the nucleus of the entire western end of the island. Mount Below falls from its peak to its base in a continuous slope, and has the shape of an almost regular cone. The coast has various small bays which have more or less good anchorages according to the prevailing wind direction; proper harbours are lacking here.

On 18 March 1888, this region was the stage for a destructive natural event. In the early morning of that day, a tidal wave poured onto the shore and spread so rapidly along the coast that shortly after 7 a.m. its presence was felt in the far north of the island, in Blanche Bay on the Gazelle Peninsula. It was driven onto New Britain as far northwards as southwards; the north-running wave reached Blanche Bay first, the one running along the south coast not fully ten minutes later. In the inner corner of Blanche Bay the united waves reached 2 metres high, and for about two hours there was a continuous flooding and receding of the sea; at the western end of New Britain measurement established that the wave had reached 12 metres tall.

It was established later that the tidal wave had been caused by an explosion of volcanic Ritter Island in Dampier Strait.

The wave destroyed a large part of the low-lying coast of the island. Broad stretches were totally devastated; in places the coastline was completely razed and covered with trees tumbled over one another, broken coral limestone, sand and rotting sea creatures for up to a kilometre inland. Numerous native villages were swept away, and a great proportion of the population must have lost their lives through the suddenness of the catastrophe.

Two Europeans, von Below and Hunstein, together with a number of their coloured attendants, also met their deaths in this natural event. They were returning from an inland expedition, and were camping on the beach that morning, awaiting the arrival of the steamer that would take them back to Finschhafen. The steeply rising terrain behind the camp was probably brought down by the tidal wave, and the tumbling masses of earth and rock overwhelmed both the camp and its inhabitants. In spite of the most exhaustive searches the camp site could no longer be found.

From the western end of the island a broad flat stretches along the northern shore as far as the Willaumez Peninsula. The coastline has various deep bays, as well as several quite good harbours and numerous, more or less important rivers. The most significant of these flows into the sea not far from the Willaumez Peninsula, but even today its course is totally unexplored. Off the coast are extensive coral reefs, endangering shipping; several small islands also lie here but are of little significance. Extensive stretches of shoreline could with time 15be opened up for cultivation; yet today there is still not one single white settlement. Of course the rivers are all closed by bars to navigation by larger ships, although smaller vessels may go far upriver.

In several places the mountain range of the interior is of insignificant height, so that the northern and southern shores of the island could be connected by a road network without great difficulty or expense. Such a road system would extend out roughly from the lowlands of the river whose mouth is not far from Cape Merkus on the south side. It could traverse the entire length, across fertile stretches of land. The produce could then be transported to loading sites on the river bank.

Herr von Schleinitz, who explored this coast, incidentally expressed his opinion as follows:

What I considered particularly important, is the fact that I … came across larger low-lying areas, especially on New Britain. The low plain on New Britain, which is situated between the volcanic mountains of the western tip and those of the central part of the island, and runs from the north coast to the south coast, was estimated to cover an area of 4,000 square kilometres. It has, as far as I could examine, fertile soil watered by navigable streams, two of which I explored more closely by travelling 5 to 6 nautical miles upstream by boat. In fact they have an easily avoidable bar, about 1 metre deep off the mouth at low water, but beyond this they have navigable water to a depth of 4 to 12 metres for as far as I was able to travel upstream by rowboat. I thought it likely that these rivers had navigable waters of 4 to 5 metres for many miles still, further upstream.

The plain … has undoubtedly a great future, even if a portion of it should comprise swampy ground, indications of which were, however, not discernible.

So runs the account of Herr von Schleinitz in 1887 in the Nachrichten aus Kaiser Wilhelms-Land without so much as a single part of it having been adopted, so far, to take advantage of the indications given therein.

The reader will recognise from the above that I attribute the greatest significance to this western part of New Britain. Should the colony, as we might suppose and hope, develop further over the years, the western part of New Britain will rapidly outstrip the northern part, the Gazelle Peninsula – not only in consequence of the greater extent of the fertile stretches of land, but also because of easier access by means of navigable rivers and more secure harbours. Herr von Schleinitz estimated the flat land on the north coast at 4,000 square kilometres. However, by bringing the fertile land on the south coast into consideration as well, we would confidently estimate the total extent as double. The native population, as far as we could discover at present, is not exceedingly dense; in any case it is nowhere near as dense as on the Gazelle Peninsula where the administration is already experiencing difficulty in settling the natives on predetermined sites, so that areas of land surplus to their food requirements can be developed for efficient plantation enterprises by whites. The natives there cultivate mainly taro and to a very limited extent coconut palms. They can therefore be relocated to dwelling sites much more easily than those who grow mainly coconut palms, as on the Gazelle Peninsula, and who are naturally less inclined to give up their ownership of profitable resources and lay out new cultivations that would yield a profit only after a considerable number of years. For natives who cultivate taro it is all the same where their dwellings are moved to, provided they find suitable soil there, and the necessary protection against possible land-grabbing by colonial settlers.

The Willaumez Peninsula, a part of western New Britain connected with the main island to the south by a broad base, stretches northwards, with a north-south length of about 65 kilometres. Up to 1889 maps showed a number of raised volcanic islands here, separated from each other and the main island by broad arms of the sea. Herr von Schleinitz finally pointed out that what had previously been regarded as individual islands were actually high mountains connected by low-lying land. Exploration by HIMS Möwe, as well as expeditions by various private individuals, have recently established the precise shape of the peninsula. From not too far away it appears as if one is faced with an archipelago of volcanoes of varying heights. None of them is active today; however, if we imagine that all of these craters were actually active at one time, this must have been a sight, the like of which may scarcely be found on the rest of the earth’s surface.

On the eastern side of the peninsula the spacious Hannamhafen offers a safer anchorage. The extinct volcanoes form a broad semi-circle around it. In particular, the regular, cone-shaped peaks of the Pyramidenberg, Zweigipfelberg, du Faureberg, Giquelberg, Raoulberg and Willaumezberg rise above their numerous smaller volcanic colleagues. Today idyllic calm pervades; the flanks of the firebelchers have become overgrown with vegetation part-way up to the peaks over the years, but the fact that the subterranean fire is active even today is evident in the north-western corner of Hannamhafen.

On the occasion of a reconnoitre by HIMS Möwe in 1900, in which the author participated, together with Geheimrat Dr Koch, Governor von Bennigsen, and Dr Alex Pflüger from Bonn, white steam clouds were noticed towards evening in the inner corner of the harbour, rising at regular intervals above the treetops. Since general curiosity was aroused, an excursion to the spot was undertaken very early the following morning.

Right on the beach small streams of boiling water bubbled out of the sand, and beyond a narrow sand 16barrier a small swamp of hot mud and water had formed. On skirting this swamp, we reached a wall of piled-up sinter blocks about 10 metres tall, over which we clambered for about ten minutes, forcing our way through the undergrowth and thickets. On emerging from the bush we saw before us, in a basin-like hollow surrounded by forest, a sinter field roughly 250 metres long and 150 metres wide, free of vegetation, from which several geysers hurled their boiling water and their columns of steam into the air. We carefully worked our way forwards over the hot and, in many places, very porous and brittle surface, past bubbling mud pools and hot springs, up to the larger, active geyser situated roughly in the middle of the field. In the interval of approximately two minutes it erupted for about a minute and spouted considerable amounts of water up high. Not far from this larger geyser was a smaller one which gushed water about 1 metre high in the same period.

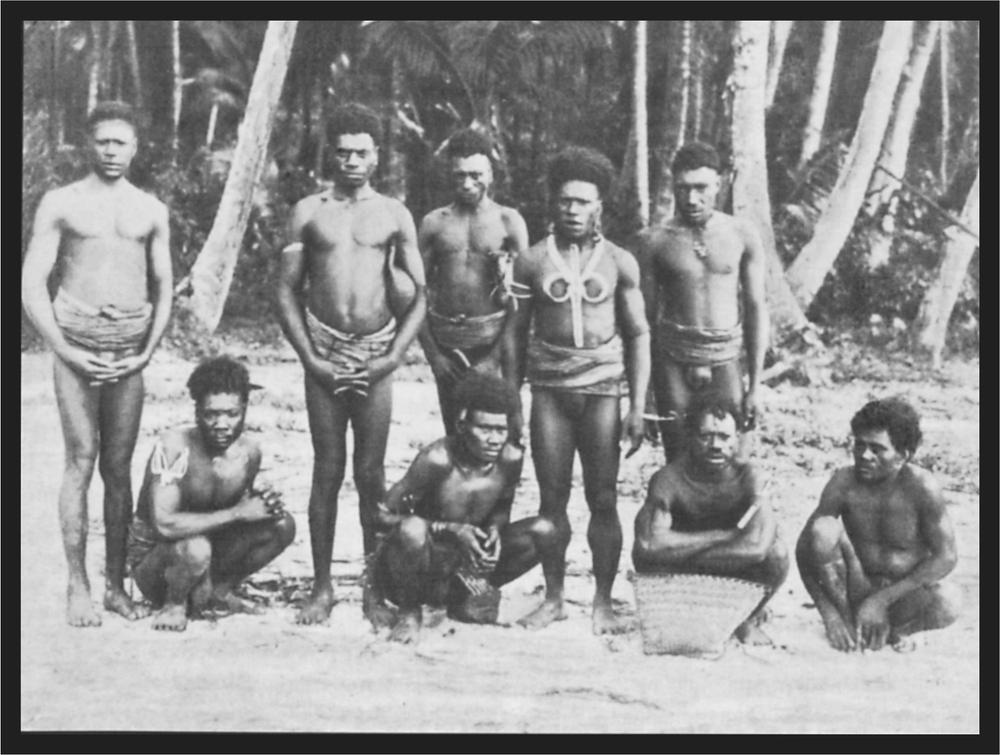

Plate 3 A group on the island of Aveleng. Raised coral banks

It was extremely interesting to peer down into the throat of the larger geyser. When the water jet was perceived to have collapsed, one could step right up to the rim of the irregular, broad opening. Water, like steam, disappeared just as suddenly as it had been flung up; in the end there still remained a small film of steam at the bottom of the throat, where boiling water fell foaming and seething over mighty sinter blocks. This lasted for a few seconds, then it suddenly gurgled and roared in the depths, boiling water again broke forth vigorously out of every fissure, steam columns raged up and veiled everything that was going on further inside the throat, and in the middle of the steam cloud rose a water jet about 1.5 metres wide, that soared to about 5 metres and then separated into countless droplets which were hurled as a fountain about 10 metres high.

Beyond these two geysers, further back in the sinter field, lies a third, very large geyser. During our time there, this one sent no column of water skywards, and the intervals between the periods of activity could not be determined. However, there were indications that this geyser is active too, albeit at longer intervals. The sinter cone is very well preserved; we were able to go right to the edge of the throat, where we observed mighty volumes of boiling water bubbling wildly in the depths.

In the field there are also a number of small, hot springs, solfataras and mud volcanoes with masses of boiling, grey mud.

The boiling water thrown up had a strong salt content, with a pronounced acidic taste.

The subterranean hearth must lie very deep, as testified by the forest enclosing the sinter field. Mighty forest trees grew round about, right up to the edge of the field and stretched their green branches far out over it, indicating that soil temperature must be normal here, otherwise all vegetation would have died.

This geyser field is probably the remnant of once greater geyser activity, for round about, on later 17excursions into the virgin forest, we found sinter blocks of all sizes and stages of decomposition at altitudes up to 100 metres, and at one site a type of soil that Dr Pflüger identified as porcelain clay.

Although there are larger low-lying areas between the volcanoes, where cultivation might be very profitable, the peninsula can never be the stage for great undertakings because of its ground formation. Apart from that, the numerous volcanoes in their uneasy quiescence do not create an impression inspiring trust, and one involuntarily asks oneself the question: When will this place be the scene of a terrible catastrophe?

About 80 kilometres north-west of the outermost tip of the Willaumez Peninsula lies a small group of islands, indicated on maps as the Französische Inseln (French Islands). These comprise a northerly group, of which the island of Deslacs or Witu is the largest, the island of Forestier or Mundua the next largest, while about 50 kilometres to the south-west lies the isolated island of Mérite or Unea.

All of the islands consist in part of raised coral formations; however, the greatest part is volcanic rock. On the so-called North Island there are hot springs, and a not inconsiderable geyser, which develops significant activity right on the seashore, separated only by a sinter wall. This, however, does not appear to be regular. Right at the time I was there, the water fountain rose only about 1 metre; however, according to the natives’ comments, the geyser could from time to time hurl a jet of water up to 10 metres high, and from the signs around this seemed not unlikely. Moreover the natives have the boiling water from this bubbling spring at their disposal, using it for cooking their food; it is seen to be surrounded by natives virtually all day long.

The island of Deslacs has two harbours that should not remain unmentioned here. One, Johann Albrecht Hafen, is big and spacious but of little value, because of its considerable depth of water. On the other hand, the second, Peterhafen, although much smaller, is of decided importance for the island group. Both harbours are the remains of former craters, the walls of which have collapsed in places, so that the sea has poured in and filled the crater with water. The small one in particular, the really charming Peterhafen, demonstrates this most clearly. It forms an oblong with steeply falling slopes on the landward side, rising to a height of about 150 metres. To seaward a sand spit juts out, concealing the entire harbour from the sea, so that even ships sailing past close inshore would never suspect such a harbour. In front of this crater harbour an offshore coral reef with a wide, deep entrance forms a good, outer harbour. Peterhafen itself is not very spacious; on the other hand even during the strongest winds it is as calm and still as a millpond. From the high crater rim there is a splendid view over the little basin and the blue tides of the outer harbour, bordered with a white crown of foaming breakers that roll over the coral reef.

The island group, which is in part the property of the New Guinea Company, exports a fairly large quantity of copra and therefore the company maintains an agent here who exploits the coconut crop. When I visited these islands for the first time years ago, they were heavily populated; today only a small remnant of the population is left. Numerous natives were struck down by a smallpox epidemic which ravaged the New Guinea coast in 1897 and also extended to New Britain and several of the smaller islands. The epidemic was introduced to the French Islands from the Willaumez Peninsula and proceeded in a terrible way, particularly on Deslacs. The smaller islands suffered to a lesser degree, and only Mérite seems to have been spared.

About 60 nautical miles west of the French Islands lies an extensive coral reef, Whirlwind Reef, which in 1899 almost caused a disaster for the imperial cruiser Kormorant. En route from Kaiser Wilhelmsland to the Bismarck Archipelago the cruiser, because of a shift in the strong current, ran onto the coral reef. Although the ship had not been holed, the forward section had embedded so deeply into the reef that initially all attempts to float her off by steam power proved fruitless. They therefore proceeded to lighten ship; the major part of the coal supply was thrown overboard; then followed all heavier items that could be disposed of for the present: chains, part of the ballast, torpedoes, munitions, steam winches, and so on. The cannon were held back right till the last critical moment. Fortunately they were saved, for on the seventh day, due to never-failing presence of mind and prudence, the commanding officer Lieutenant-Commander Emsmann, and his officers, supported by an efficient crew who carried out the necessary steps for saving the ship with unflagging and exacting effort during the worrying time, finally succeeded in refloating the cruiser.

The heroic saving of the ship from going down is one of those deeds of our German navy which is acknowledged far too little at home. The attention of the greater public is only aroused when a tragic catastrophe occurs, like the sinking of a ship. If the good Germans at home were more familiar with the doings of our fleet, particularly overseas, they might perhaps be less inclined to deny expenditure on the navy. While every triviality at home is discussed as widely as possible, those events that are not accessible to the ordinary reporter are given only quite casual mention; at the most, a brief telegram announces the casualties.

The Neulauenburg group (previously Duke of York) is a group consisting of several smaller, and one larger, islands in St George’s Channel, about 188 nautical miles north of Cape Gazelle and 20 nautical miles west of the New Ireland coast. On modern maps the old, inconsistent names Amakata, and so on, once resplendent on older maps as island names, are gradually disappearing.

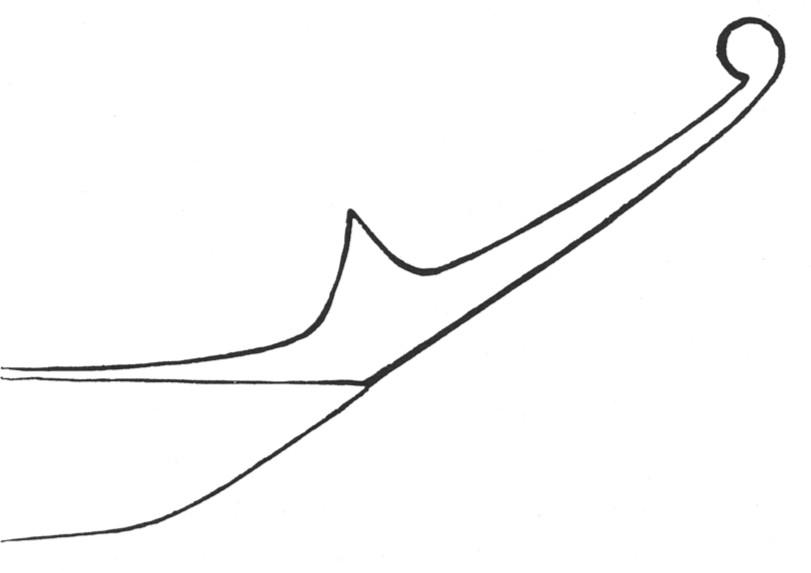

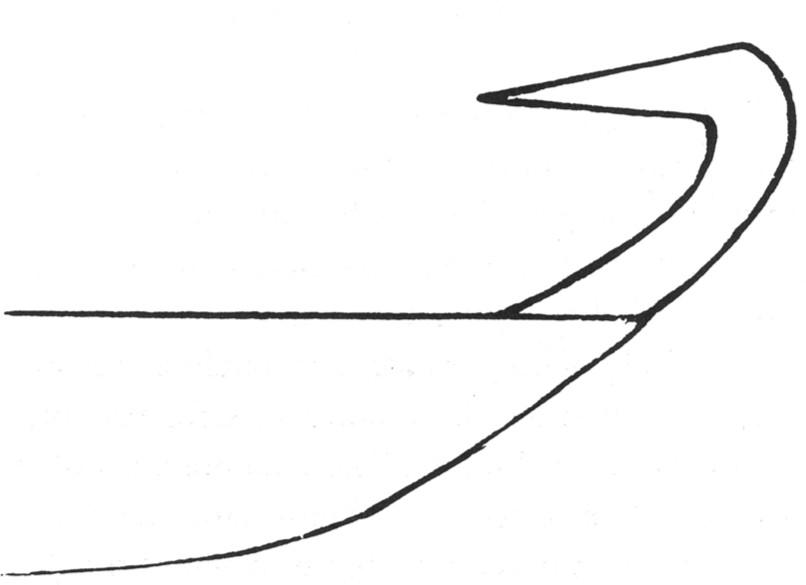

This brings me to the distressing question of geographical nomenclature. I am totally on the side of Herr von Luschan, the meritorious promoter of this question, when he turns against renaming, where good indigenous names exist. The Bismarck Archipelago and Kaiser Wilhelmsland in particular are brimming over with new-found names that hopefully over time will yield to the indigenous names, the more so since several of these are so ill-defined in position that it causes doubt for the traveller or seafarer where precisely the point in question lies. Thus, for example, it is extremely difficult to differentiate between the numerous points jutting out from the New Ireland coast: Kap Strauch, Ahlefeldspitze, Rittmeierhuk, and so on. The natives obviously do not know the names given by the Europeans, and the latter know the native designations just as little, and consequently it has come about that natives, adrift in their canoes, who finally arrived at a settlement, could not be sent back to their homeland because the name that they gave to their dwelling place was totally unknown. As a rule the origins of such natives have been determined from the type of construction of their canoes, from the weapons they carried, or from their decoration. Now, however, in a lot of cases it is quite difficult, even with the best will in the world, to discover the affiliations of the natives. With the tangle of languages predominating in Melanesia it is impossible for one individual to communicate with all the tribes; questions put forward are incorrectly comprehended by the natives and a false answer results, haunting the maps for further long years. The name Amakata, for example, certainly originated in this manner, by pointing, for clearer understanding. The native had understood that a name was wanted; he followed the direction of the outstretched hand with his eyes and gave the name of the particular island that had been directly pointed to. The answer accordingly ran a makata (a is the article), the name of one of the islands, and the inquirer made of this Amakata, as the principal designation of the entire group. This has no collective name at all, likewise the main island has no individual name. The earlier name of New Ireland, Tombara, arose similarly. It is an erroneous rendering of the word taubar, the direction from which the south-east wind comes, and therefore probably arose because someone indicated that direction with the hand. The number of similar examples can be multiplied without difficulty.

A further difficulty is that the natives have a particular name for a particular place or for a particular small island where they live, while distant natives know the place by a totally different name. During my brief stay on the islands of Durour and Matty I could not discover the local designations. A native of Ninigo who had lived there a long time designated them as Huen and Popolo. However, after we had got to know the natives of both small islands better, it turned out that the natives call their islands Aua and Wuwulu, and that Huen and Popolo are special designations of the Ninigo people. This example too can be multiplied ad infinitum.

As a rule, it can be defined thus: whole mountains and mountain ranges are given no collective names by the natives, but on the other hand individual peaks worthy of note have different designations in the various regions round about. Large islands that cannot be perceived or distinguished as such all at once, likewise have no designation; they are as a rule divided into individual districts or regions, whose names are also known to distant dwelling natives, and these are subdivided into villages or districts with unique names; the individual areas of the village on the other hand are recognised under special names by the residents. Inhabitants of neighbouring islands frequently have other designations for coasts, districts and villages of the islands nearby, that are never used by the locals. Parts of the sea, bays, harbours and straits have, as a rule, no special name, but are named for the nearest islands. Detached reefs seldom have a native designation. Characteristic foothills, prominences and mountain peaks, as well as rivers and streams have as a rule individual, independent names.

It can be seen from this that it is not always easy to establish the correct designation, apart from the difficulty that the written rendering of the name often provides for the European; and that in spite of the best intentions, we always come back to the embarrassing situation of inventing names and designations for localities that have none, and which nevertheless we perforce must name, because otherwise significant gaps would arise in the nomenclature, which might be regarded most disagreeably by travellers, seafarers and settlers.

Recently native place names have increased, which is as it should be, but it will still be a long time before we have done away with names like Herbertshöhe, Hannamhafen, and so on. Out of respect for the names and memories of old seafarers and discoverers, many of these names will still be retained, in spite of the natives’ designations ascertained in the meantime.

After this digression I will return to the Duke of York group.

It has a surface area of 75 square kilometres, and in 1900 the population numbers, from a census by the then Imperial Judge Dr Schnee, amounted to 3,373 individuals: 1,060 men, 935 women, 772 boys and 606 girls. The number of births came to 253, deaths 212. From this it would seem that the 19population is in a state of growth; however, this is not the case, for during my long stay in the archipelago the population has decreased markedly, and is being augmented continually by newcomers from New Ireland and the Gazelle Peninsula.

The islands consist entirely of raised coral formations that form steep shorelines, especially in the north and west. Repeated raising, interrupted by periods of sinking, can clearly be detected in places, and we can conclude from this that the same also occurred on the neighbouring islands. The highest elevations are the two hills on the island of Makada, 80 and 100 metres high. Otherwise, the islands are flat and covered with thick forest.

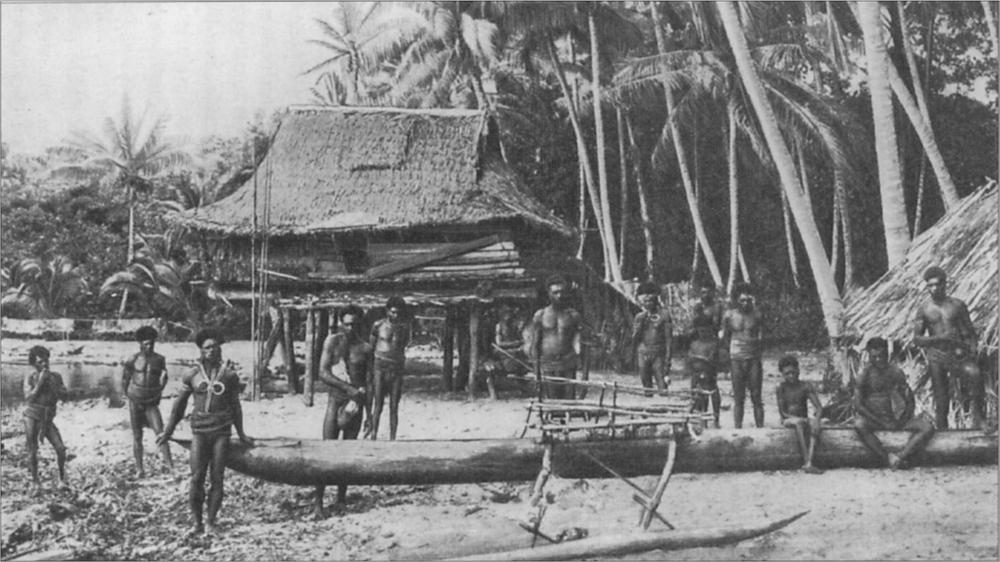

South of the main island of the Duke of Yorks lie a number of smaller islands, three of which, Ulu, Utuan and Mioko, form the splendid Miokohafen that provides a completely safe anchorage, protected against all winds. Two practicable entrances, the Levinson and the north-west passes, lead into the harbour and permit sailing ships to enter or leave the harbour by one or other pass, depending on the prevailing wind. South of Ulu the two small islands of Kabokon and Kerawara likewise form a harbour, but of lesser significance. At the north-west end of the group lies the island of Makada, separated from the main island by a strait which forms a somewhat protected anchorage. As a continuation of the big island to a certain extent, several small islets lacking particular importance lie off its extreme north-western corner. Also worthy of mention is the small Hunterhafen, close to the north-west corner, scarcely, however, of any consequence to shipping.

Although the harbour of Mioko must be regarded as quite outstanding, it is of little value for the future development of the archipelago because of its remote, insular position. In earlier years it had played a major role, and was for a time the starting-point for further commercial undertakings in the archipelago after the Hamburg firm of J.C. Godeffroy & Son established a station there in the mid-1870s. Also, the firm of Hernsheim & Co. founded their first settlement on Makada, relocating to Matupi in Blanche Bay a short time later. The original Godeffroy station on Mioko later passed into the hands of the Deutsche Handelsund Plantagengesellschaft which still runs it. It participated only to a limited extent in the commerce of the archipelago and has contributed little to its development over its many years of operation. The company’s main aim today is to recruit about 250 workers annually for its plantations in Samoa; thus creating markedly unpleasant competition for the archipelago, which annually requires an increasing number of workers for the inexorably expanding plantations, and coming very close to causing direct damage. Hopefully the administration in Samoa will gradually succeed in overcoming the laziness that has become second nature to the Samoans, to the point where that colony will be in a position to produce its own workers. The commercial undertakings of the company are taken care of by a staff of Chinese merchants, for whom one or two whites act as overseers on Mioko, as representatives of the parent company.

As in earlier times trade developed outwards from Mioko, so was Hunterhafen the startingpoint of the first Christian mission, having its main seat there until 1900. However, since then, it has withdrawn to the island of Ulu in Miokohafen and founded a secondary school under the guidance of a white missionary, for the education of native mission teachers.

In spite of early colonisation by whites, and in spite of a splendid harbour and a fertile soil, plantation agriculture only began to exploit this group of islands in 1901. The Catholic mission has acquired the southern end of the main island from the Deutsche Handels- und Plantagengesellschaft and set up a plantation there; the Methodist mission is cultivating Ulu, and the island of Kabokon belongs to a private citizen who has brought it into palm cultivation.

On the island of Kerawara the first station of the New Guinea Company in the Bismarck Archipelago vegetated for a while, setting its administrative apparatus in motion from here on outwards, in its own time. One could hardly have chosen a less favourable site, and accordingly in 1890 the company saw the need to transfer to the presentday Herbertshöhe.

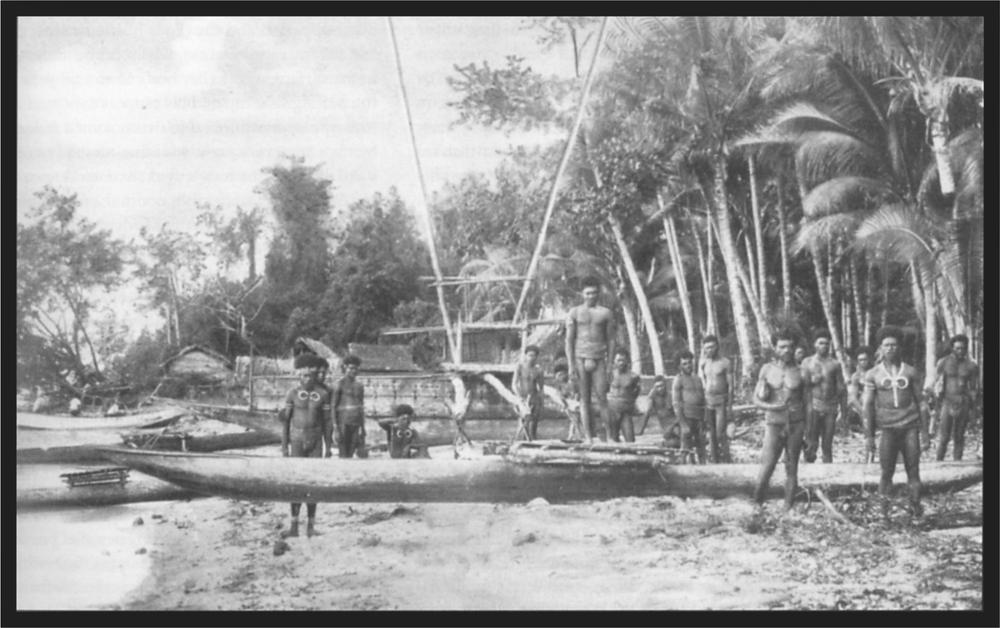

2. The Inhabitants

Just as the island of New Britain can be divided geographically into various main divisions, it may also be divided ethnographically into several provinces that exhibit only a superficial, loose connection with one another. It remains to be seen whether these ethnographical provinces coincide quite precisely with the principal geographical divisions, and whether one might establish beyond doubt an original connection. Wherever we go on the island, we come across the effect of volcanic forces that have taken an active part in the mighty accretions of loose rock, and in the uplifting and sinking of the earth. Because of this the surface of New Britain, like its outlines, must, from time to time, have undergone great changes, and these changes have affected the population: dispersed tribes, erected barriers between some, and linked others again by bridges. These changes have not taken place slowly and steadily, but in fits and starts, in some places suddenly, in the form of mighty volcanic eruptions. All of this has, over the course of millennia, left its mark on the population, and the most cursory observer will notice the difference immediately when, for example, he sees a native from the Herbertshöhe area alongside one from South Cape or from the western end of the island.2021

Map 2 New Britain

22The northern part of the island, the Gazelle Peninsula, comprises as I have already mentioned, two main parts: the Baining Mountains with their foothills, and the north-eastern plateau, separated from each other by a depression cutting deeply into the land from Weberhafen, frequently traversed by the rivulets and streams which pour out of the mountains. This land depression stretches through the entire Gazelle Peninsula, from Weberhafen, out beyond Vunakokor, right to St George’s Channel, in this latter part forming the sunken valley of the Karawat or Warangoi River. The north-eastern plateau comprises deposited volcanic material: pumice, ash, blocks of obsidian, lava debris, and so on. This deposition did not originate suddenly from a catastrophe, as is indicated by steep slopes where one can clearly observe the laying down of strata over different periods; moreover major uplifting and sinking must have taken place alternately, because many of the strata were unquestionably deposited beneath the sea, then, after an uplift, covered by erupted material from the volcanoes, before sinking back into the sea. The source of this great volcanic activity is probably to be found in present-day Blanche Bay with its still partially active volcanic system, as well as in the far older volcano, Vunakokor (Varzinberg).

Before this mighty catastrophe, which may have stretched over a long period of time, the Gazelle Peninsula was undoubtedly inhabited by the same tribe. The volcanic activity buried part of the then surface under huge eruptions or sank other parts under the sea. Those who didn’t lose their lives immediately took flight, and found sanctuary in those areas that lay beyond the range of the volcanic activity. One such region was the present-day Baining Mountains with their foothills.

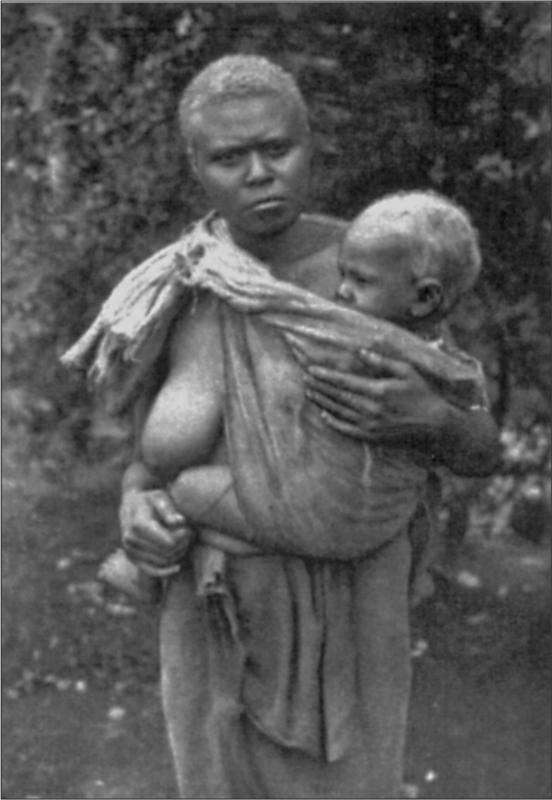

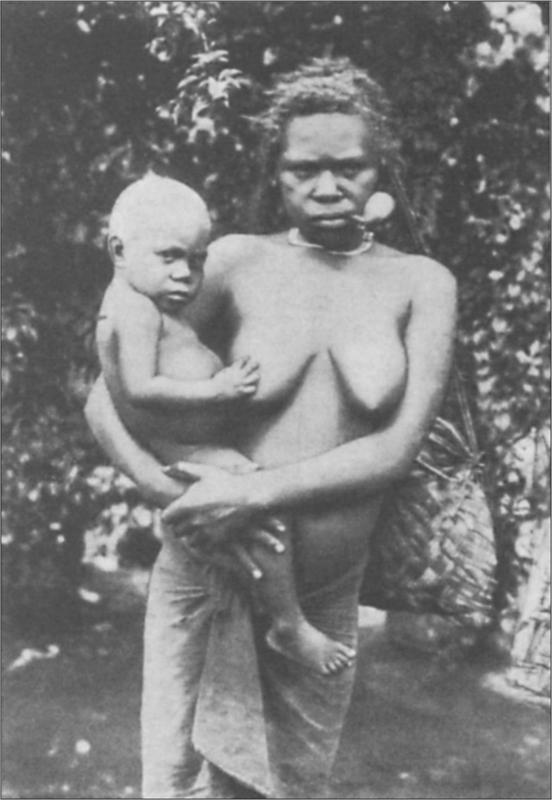

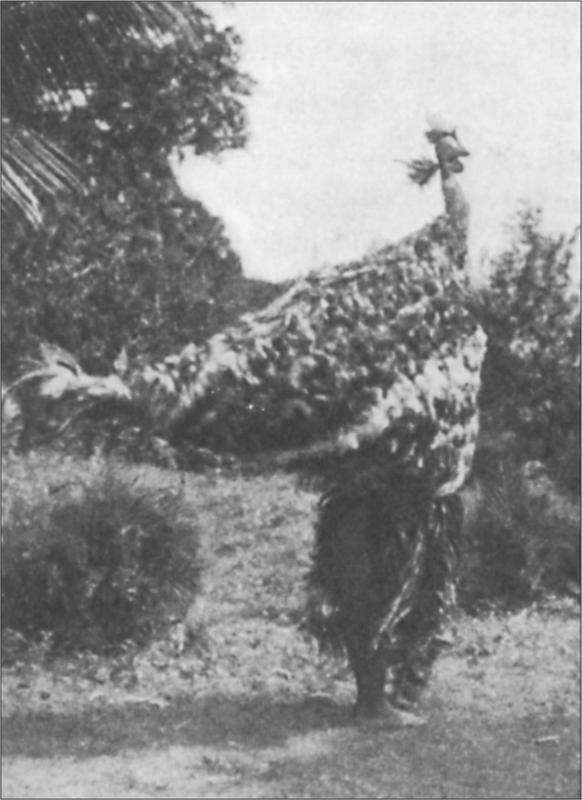

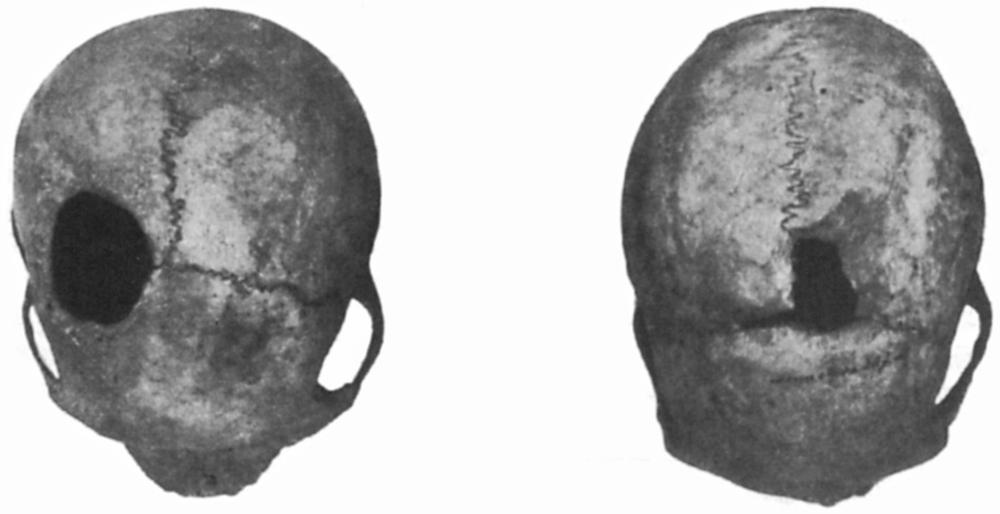

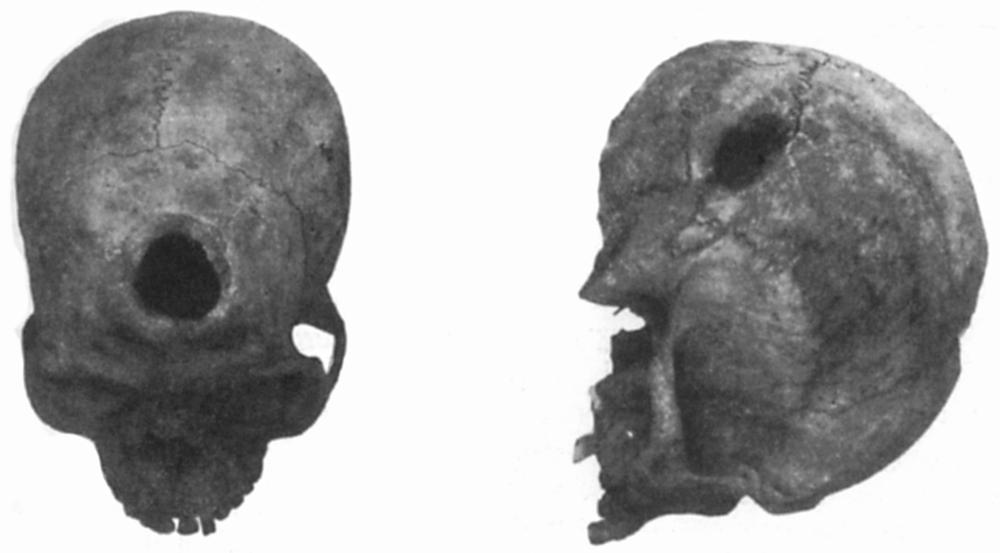

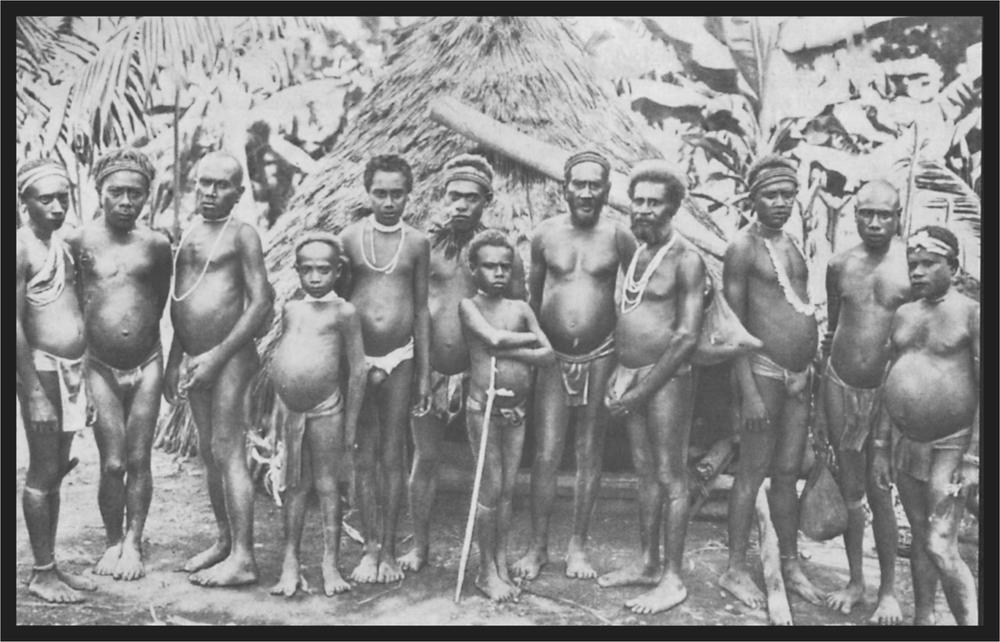

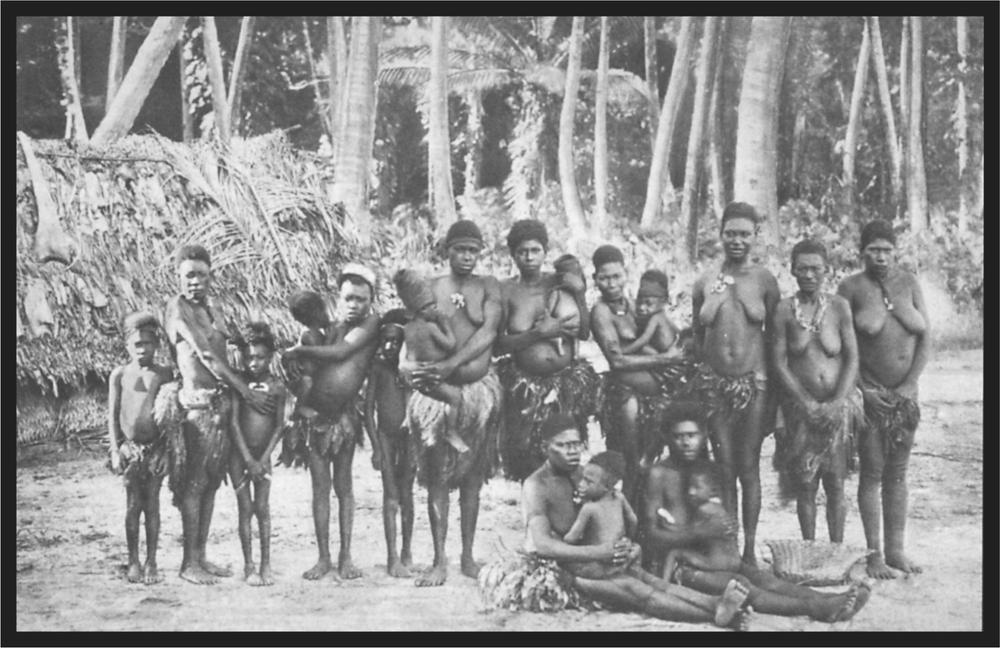

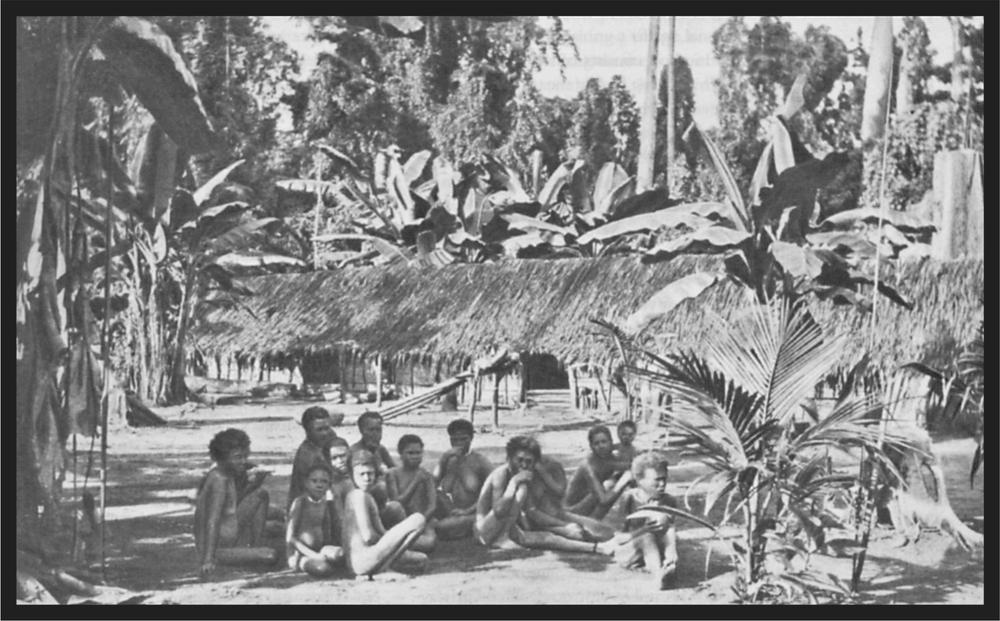

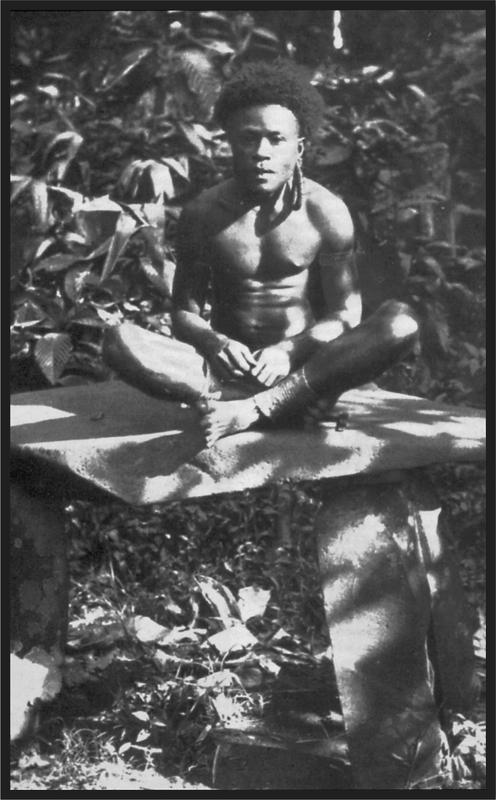

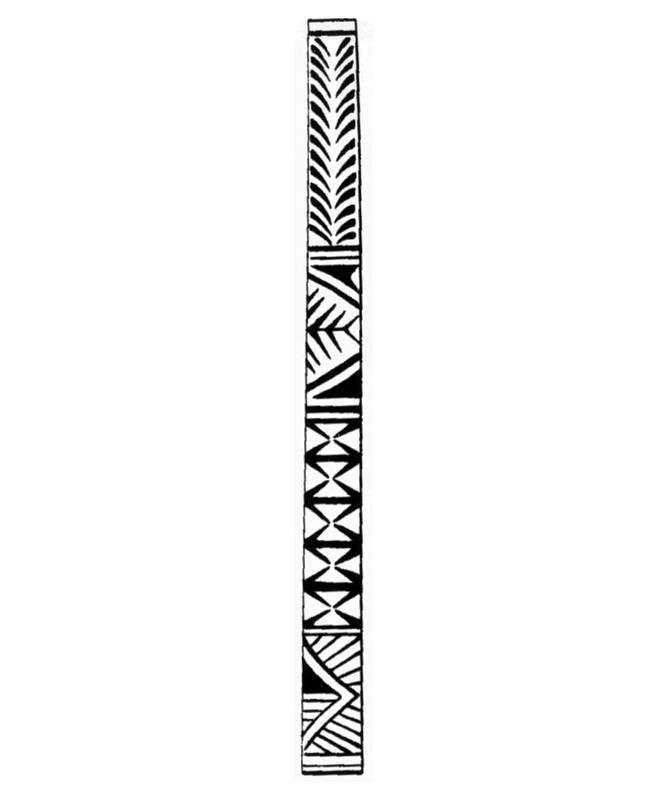

Even today therefore we find here the descendants of the original inhabitants of the Gazelle Peninsula, who by their isolation have indeed largely retained their original peculiar characteristics and their language. They were named Baining by their neighbours to the north-east. They know no tabu (shell money), have no duk-duks, and are not seafarers. They manufacture stone clubs with a heavy, perforated stone head, a skill that we find again only in a few areas of New Guinea. I have extensively discussed their characteristic dances, with curious, mask-like headgear, in another section. Physically too they differ from their neighbours in their solid physique; they are considerably inferior to them intellectually, and in this respect they probably belong among the most inferior tribes of the archipelago. Right up to the most recent times they were the objects of systematically organised slave raids with associated cannibal feasts.

Now where do the inhabitants of the north-eastern Gazelle Peninsula originate? It doesn’t seem difficult to answer this question with some certainty.