VIII

Secret Societies, Totemism, Masks and Mask Dances

It is typical of almost all Melanesians that they form societies and cloak them with secrets which are withheld from non-members and especially women. We know of such secret societies in New Guinea, New Caledonia and the New Hebrides, and we find it again, in the most varied forms, on the islands of the Solomon group and the Bismarck Archipelago.

It is difficult to establish the reason for these institutions. I regard it as fruitless to discover the origin from the natives themselves, when the institution goes back a number of generations. Here as in so many other cases the only response you would get would be: ‘Our forefathers did it this way, and since we have learnt it from them we do it too.’

We have a quite significant number of more or less ingenious speculations about the origin of these customs. However, they all suffer from the authors all giving their fantasies too much free rein, fastening onto single events that apparently support their theories and suppressing others because they stand in contradiction. Futhermore, it is common to all these fantastic imaginings, that they revolve around a train of thought that is so far removed from a people of nature as the philosophical system of a Kant or Schopenhauer is from the comprehension of a budding sexton.

To put oneself into the train of thought of a Melanesian is not easy. Intellectually, he is at a low level; logical thought is in most cases an impossibility for him. What he does not grasp directly through observation by his senses, is witchcraft and magical art, about which further laborious investigation is a completely useless task. Most probably the explanation of many secret societies and the institutions connected with them lies in customs that have their origins in sorcery, either to prevent the evil consequences of magic or to help produce more favourable living conditions for the participants.

Not infrequently, ancestor worship and totemic notions are broadly or narrowly connected with the secret societies, but here too the reason can probably be found in sorcery and belief in the supernatural, and it is therefore little wonder that the natives gather together all customs founded on these sources, and over the course of time build up a certain system of practising them.

It is not my intention to examine the spiritual core of the secret societies as far back as their origin; I will endeavour in the following to describe individual connections of this nature in the Bismarck Archipelago and the German Solomon Islands, as they present themselves to the observer today. Many customs have, in spite of apparently diverse external form, arisen nonetheless from basically the same universal concepts, although having become so modified over the course of time in different regions and under different circumstances that the original basic idea and the original form can only be recognised with difficulty today. Also, it does not seem impossible either that, once in a while, a direct transposition took place in such a way that the institution was transplanted to other districts and, by virtue of the universal reliance of all Melanesians on mystery, found fertile soil. Otherwise it might not satisfactorily explain how in districts far apart small details in the ceremonies or external features of the masking correspond perfectly.

When I use the words ‘secret society’ here, I must add at the outset that I do not want to imply the associations of the natives in the sense that we use the word in Europe. A ‘secret society’ in the civilised world is an association of individuals known to one another, often only in restricted numbers, but always remaining unknown to all non-members of the society; indeed often the very existence of such a society is a deep secret. The secret societies of the natives can evoke this name only in so far as their customs and aims are known only to the members of the society; the members themselves are known to the community, and this circumstance in itself gives them an advantage over non-members in their daily life, and provides impetus to the latter to gain the privileges from being in this society.

Thus, on the Gazelle Peninsula, for example, every wife and every non-initiate knows who belongs to the society of the duk-duk; and in northern Bougainville every villager knows who is 248a matasesén and thereby initiated into the secrets of the ruk-ruk or burru; but the uninitiated have not the slightest knowledge of the ceremonies connected with them, partaken on rigorously separated sites; at the most they are told stories about ghostly apparitions and about sinister actions and behaviour.

Also, the customs of the secret society are not always a secret to the uninitiated. As soon as the secret society members deem it appropriate to present themselves publicly for any particular purpose that serves their society, they do it, although preserving secrecy by the active members appearing masked. Thus on the Gazelle Peninsula the tubuan and the duk-duk display themselves to the non-members, wandering from village to village in their characteristic masks. We find the same on Buka, where the kokorra present themselves masked in public. But always the real ceremonial site or assembly place remains strictly isolated from the uninitiated, and encroachment on it is punished with a heavy fine, often loss of life.

The initiated keep strictly quiet about the secrets of the society with regard to the uninitiated, and it is also very difficult for Europeans to penetrate the secrecy. First, one has to win the trust of the natives before one can contemplate talking on this theme or posing questions about it. Even then, one can be fairly certain that the most wondrous things will be told to the questioner and lies will be told; only numerous conversations with a wide variety of members, chance comments by individuals, or a fortunately chosen glance allow the wheat to be differentiated from the chaff.

Visiting the assembly places, or more accurately the ceremonial sites, is not difficult for the European after closer acquaintance with the natives; but he seldom sees very much that can give him clarification on the purpose or customs of the society. Either he is presented with an improvised hocus-pocus, or something completely irrelevant that bears little connection to what the society emphasises as the main element.

We find secret societies on the various islands of the Bismarck Archipelago: on New Hanover and New Ireland where they are partially connected with ancestor worship; on the north-eastern part of the Gazelle Peninsula in the form of the duk-duk; on the islands of Nissan and Buka in the form of the kokorra; on Bougainville as the association of matasesén. We find quite similar societies also, further to the south and south-east, throughout the German part of the Solomon Islands: the matambala on the island of Florida, the tamate on the Banks Islands, the qatu in the northern New Hebrides. We find them still further on New Caledonia and also in the Fiji Islands, although in reduced form and of lesser importance. Furthermore, in German New Guinea at Asa on Astrolabe Bay and in the societies that hold their assemblies at Parak (on the coast in the east and west of Berlinhafen), we recognise a related institution; it is the same with the mask dances on isolated islands of the Torres Strait and on the coast of British New Guinea opposite. On the continent of Australia, too, there are secret societies of various types, and in Dutch New Guinea and on the neighbouring islands at least vestiges are known to us.

From what we know of the secret societies today we still cannot form a totally clear picture of their aims and purposes; we are, I believe, tending too much to look for higher significance or a deeper meaning, and draw parallels and conclusions that are hardly sustainable. Over the years I have slowly come to the conclusion that basically every deeper significance is missing in all these secret societies, and that they simply serve the totally materialistic purpose of creating a higher standing of the members above women and non-members, that membership accords not only certain social advantages but also material pleasures, better food, the opportunity for laziness, for unfettered relations with the female sex, as well as the possibility of acquiring property at the expense of non-members. In some places, the secret societies even replace the organising and jurisdictive headman, when one is missing, and look after the maintenance of order within the tribe and the sustaining of the usual customs, while of course having their own interests and well-being foremost in their eyes.

In almost all cases, the uninitiated are told a number of horror stories of apparitions and relations with spirits, and all manner of strange noises are produced as further proof, ostensibly the voices of the feared spirits; however, introduction into the secret society consists of a longer or shorter isolation of the candidates, an admission fee payment to members of the society, and participation in certain ceremonies and feasts. Nothing really new is learnt by the initiate; the advantages that membership offers are bestowed on him from henceforth, and in his turn he regales the uninitiated with the same horror stories that were told to him earlier; he runs with the pack and enjoys the luxury of membership. Whether any of the initiates ever feel that they have been deluded in their expectation, of having relations with spirits or seeing spirits appear, is hard to say; however, I do not believe that this is the case. As a rule a native is not plagued with great thirst for knowledge; dealing with ghosts is a tricky business in his opinion. In any case it is better to keep out of their way. When perhaps in fear and trembling he makes the apparently fateful step and allows himself to be admitted to the society, he secretly rejoices that the frightful spirits and apparitions do not exist in reality.

Modern times have brought many enemies to the secret societies. The first of them is the white 249settler; he does not fear spirits and ghostly voices, he does not care about the traditions and customs of the natives, he does not respect the secret assembly places, and the more the native cloaks himself in secret affairs and silence, the more he sees it as his mission to solve the mystery. Many times evil befalls him through this; for example, I knew a trader who secretly took a duk-duk mask years ago. His somewhat airy home, a hut made from bamboo canes and coconut matting, was, however, not a suitable hiding place; the natives discovered the mask, broke into the house, pulled out the duk-duk and only my fortuitous intervention saved the trader from a sound thrashing, if not worse. Since this affair the natives avoided the place and took their products to neighbouring traders. Entering ceremonial sites and attending ceremonies is often permitted to white people, but the natives regard themselves as recompensed by the visitor’s falling for the most outrageous stories and subsequently passing them on to the world as guaranteed truth, reported by an eyewitness, and causing the utmost confusion.

Most especially, the Christian missionary is an enemy of secret societies; he suspects the devil’s work and is jealous of the influence of the members on society in general, an influence that he often erroneously regards as hostile to his efforts. A few missionaries have succeeded in restricting the power of the secret societies in the vicinity of their dwellings, or totally destroying them. However, among the missionaries there are also those who tolerate the secret societies, after they have recognised their significance and convinced themselves that they are basically of a harmless nature.

Also, the worldly authorities occasionally come into conflict with the secret societies when the latter inflict punishments and penances that do not always coincide with the clauses of the Penal Code; such proceedings are then forbidden and the reputation of the society falls.

I believe that both the Christian missionaries and the administration could, for their own purposes, mould and use these secret societies to the greatest advantage. So many a non-Christian institution had been skilfully adapted by the heathen converts of the previous centuries to fit the purposes of Christianity, at a time when many of the prospective converts certainly were no higher spiritually than many of the present South Sea tribes. The Protestant mission in particular shows how very intolerant it is of the customs of the natives. It seems to be inspired by the view that all the trappings of the natives, all their traditions and customs, have to be uprooted completely to give place to true Christianity, and extending out of this view they forbid anything and everything, unfortunately without giving the natives anything better, or any replacement whatsoever.

The consequence often is that slackness and indolence appear in place of the earlier daily life interrupted by celebrations and joyful gatherings, and lead to lip-service and hypocrisy, coupled with all manner of vices perpetrated in secret, which stand in far greater conflict with true Christianity than the original unchristian trappings. Of course there are also missionaries who, with a true understanding of the essence of Christianity, respect the harmless customs of the natives where these are not in direct conflict to Christian teaching, and this then leads to the peculiar spectacle that Christian natives in one district are still in possession of their old secret societies and their old customs still exist, while these are regarded as works of the devil in the neighbouring district. In the Duke of York group missionaries have succeeded in totally suppressing the duk-duk in many districts, while in Blanche Bay the teachers brought in from Samoa, Tonga and Fiji not only tolerate the duk-duk but also take part in ceremonies connected with it. Indeed I know of several cases where the teachers allowed themselves to join the duk-duk society and participated with their society brothers in the inherent advantages. A native from Makada in the Duke of Yorks, who for many years has been a keen and, as I believe, also quite an upright adherent of Christianity but is not permitted to belong to the duk-duk society there, has for long years taken part in all the ceremonies of the society in a district not far from my dwelling. When I occasionally made pretence of rebuking him, he explained that the customs of the society contained nothing that contravened the teachings of the Holy Scripture that he had read, and he therefore did not regard it as a sin to belong to the society and to take part in its ceremonies.

The duk-duk society of the north-eastern Gazelle Peninsula belongs among the most well-known secret societies of the Bismarck Archipelago. We come across it at St George’s Channel, from Blanche Bay to Kambair (Weberhafen), and inland as far as the tribes of Vunakokor. Men exclusively belong to the duk-duk society, but several old women (tubuan) are occasionally permitted to join the society, in so far as they are allowed to participate in its dances outside the taraiu.

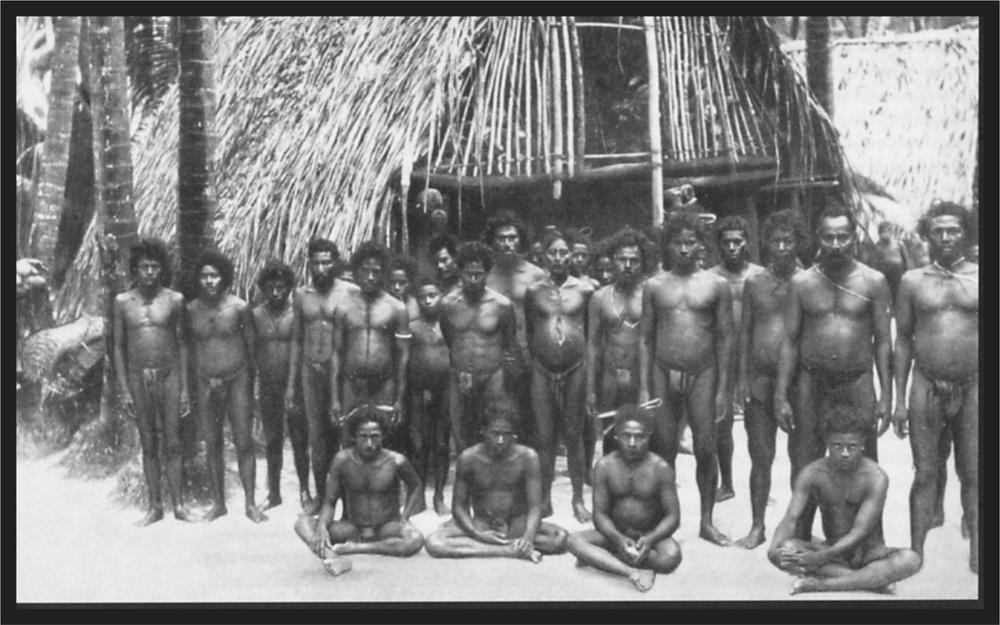

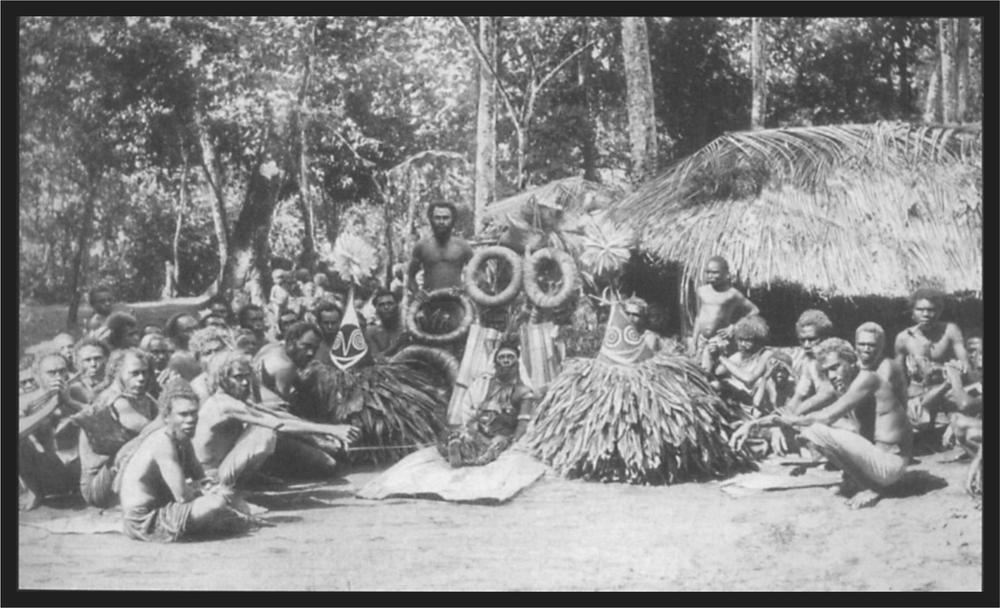

Fig. 103 The duk-duk assembled for a public dance250

Fig. 104 The duk‑duk on the taraiu

As a rule the ceremonial sites, taraiu, are entered only by members; however, an exception is always made for foreigners, especially whites; even my wife was finally permitted entry, not without murmurs from several old mystery-mongers. The location of a taraiu is known to all non-initiates, and they take great care not to set foot there because there is a heavy penalty. Should uninitiated relatives of a member intentionally or unwittingly have entered the taraiu the member must, for good or evil, pay the usual recompense to the society; how he recoups his outlay is his business. I remember such a case that occurred a few years ago. A man from Raluana, west of my home, had an understanding with a woman from Karawia; she left her relatives and met her lover on the beach at night to go with him to his home compound. However, the flight was noticed; the relatives rushed after them, and to get his prize to safety quickly the native had to cross the taraiu. The second transgression was far greater than the elopement in the eyes of the pursuers. They broke off the pursuit that was in any case only a type of formality, and the following day they reported what they had seen.

For the man, who belonged to the duk-duk society himself, there remained nothing but to pay the society the usual penance, in this case 30 fathoms of tabu.

A second case went as follows. A wealthy native had put on a duk-duk ceremony (Meyer and Parkinson, Papua Album, vol. I, plate 16 shows the ceremonial site for this occasion) to honour dead relatives at Raluana, during which there was dancing and feasting day and night on the taraiu, and members streamed in from all sides. The organiser of the ceremony, through forgetfulness, allowed a not yet fully initiated boy to enter the taraiu, for which he had to pay out 20 fathoms of tabu to the society; the boy came out of it with a sound thrashing. Understandably on these grounds the uninitiated avoid the taraiu and the members impress the ban on them even further, since it is they, as a rule, who have to pay for a native the always very high penance in tabu on behalf of the transgressor. In earlier times it has happened that women who entered the taraiu were killed by the members of the duk-duk. I recollect two such instances during the first years of my stay. Today, the offence is no longer so severely punished, out of fear of the punishing hand of the administration.

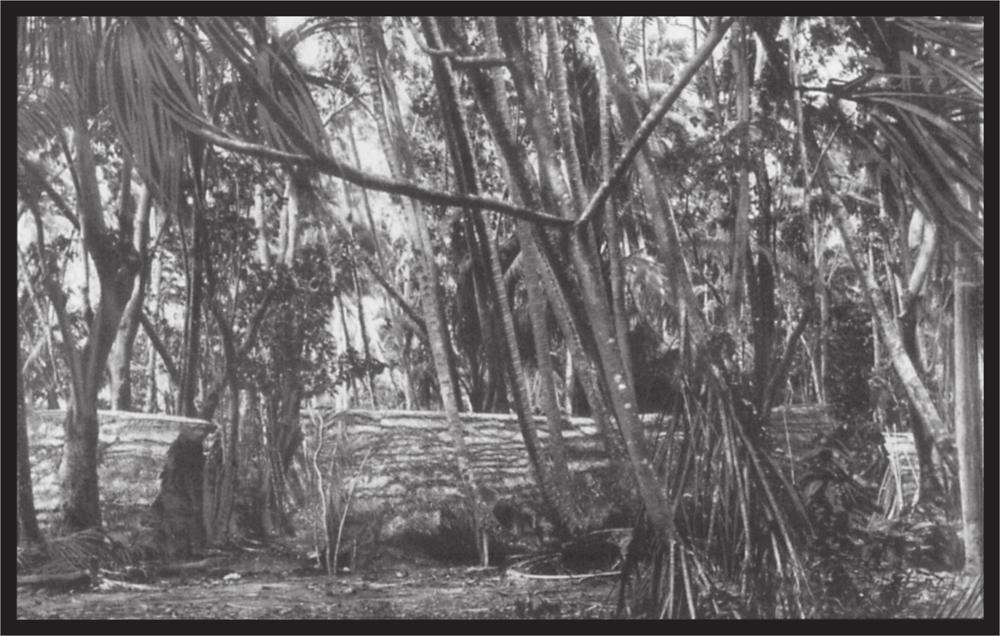

The taraiu is situated in such a way that activities on it are not visible to any non-initiate; it is situated in the forest under tall trees and bordered by bushes and shrubs with dense foliage. At the time of ceremonies it is fenced in, where necessary for further protection from curious glances, by a high fence of coconut matting. On the site there are either one or two huts which serve as a hideout for the members and also probably as a storage for the masks and leaf costumes of the duk-duk. Since numerous duk-duk masks from neighbouring districts often come together on a taraiu and the erected huts are not able to accommodate everything, posts, tagor, about 1 metre high are dug into the ground as well. On these they hang the rings of leaves that form the costumes, and the characteristic headdresses. The taraiu is kept clean and tidy by the members; also, at those times when there are no ceremonies, the old men gather here, to take a little nap undisturbed, or to discuss the events of the day.

The taraiu is the official assembly point for the members of the society. On the other hand, whenever dances and ceremonies are organised outside the taraiu by the society, an enclosed space is set up on the temporary ceremonial site to enable the masked members to transfer their costume from one wearer to another, unseen by the crowd. Usually the isolated site is densely enclosed with coconut palm leaves so that those sitting in front cannot see what is going on behind it. These temporary places of refuge are erected only for special purposes and bear the significance of the taraiu only for a moment. They are also given a special name, manamanaung.

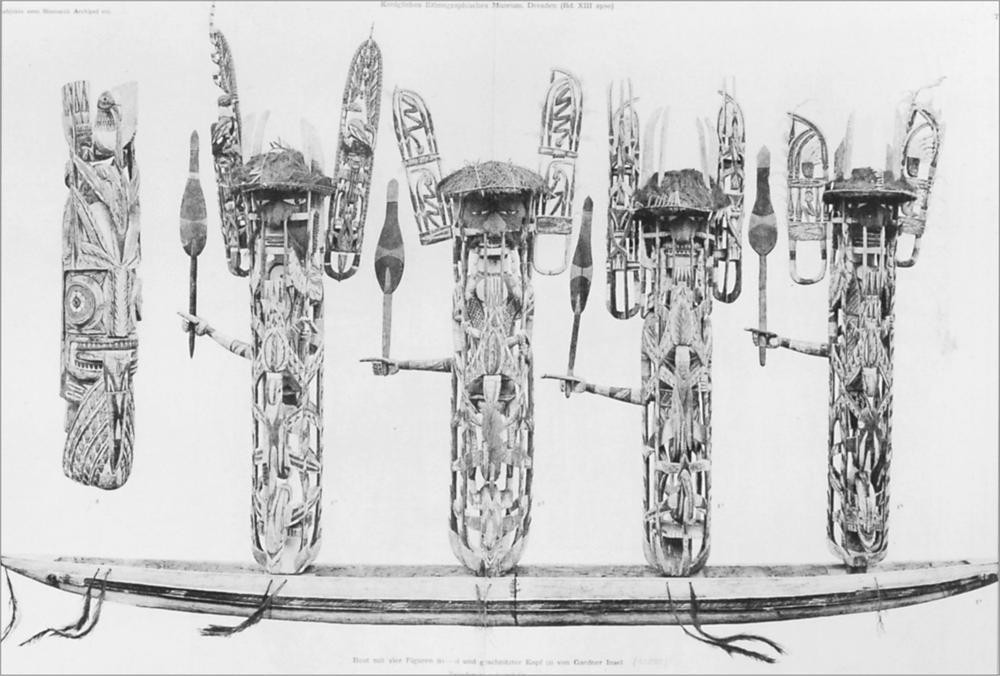

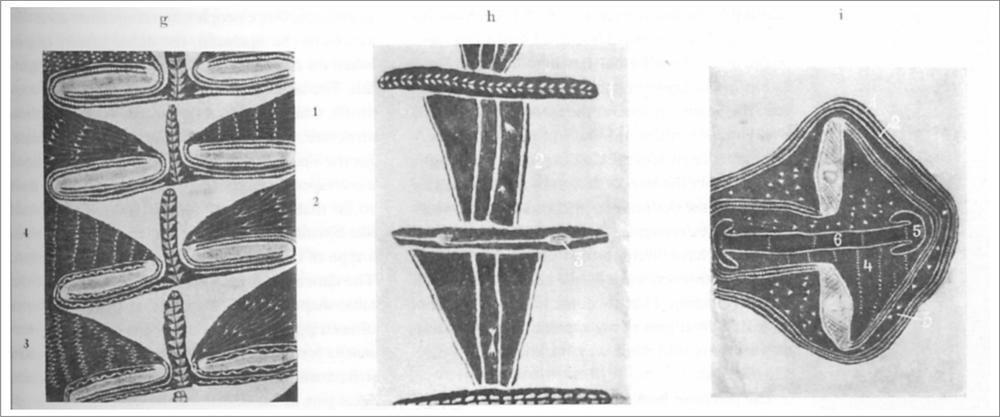

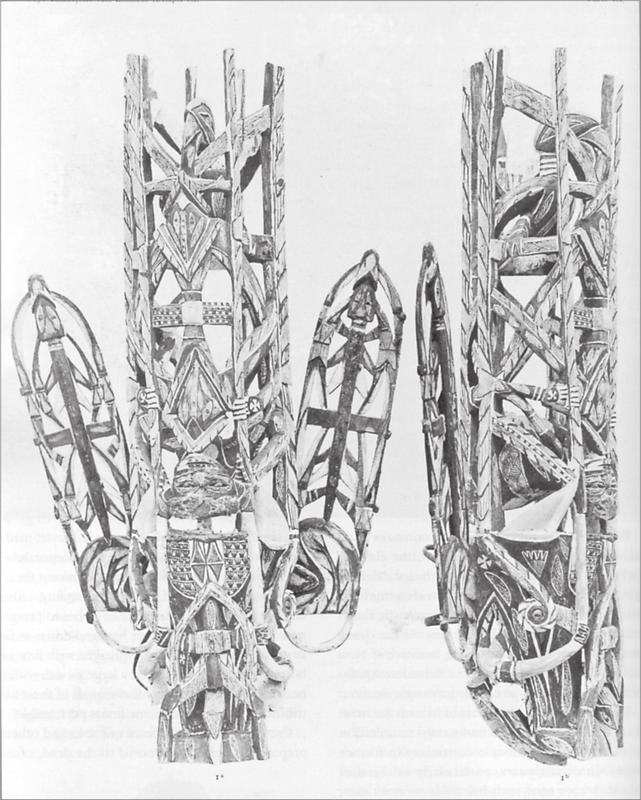

All preparations for a duk-duk ceremony are undertaken on the taraiu by the members; in particular the manufacture of mask costumes takes place here. These consist of two parts, a leaf wrapping for the upper body and a conical hat which, completely covering the head, rests on the shoulders. The masks produced are of two types depending on whether they represent a tubuan or a duk-duk. They differ in that the former’s head-mask forms a short cone crowned with a large bunch of cockatoo feathers, while that of the latter is long and tapers to a point often to a height of 2 metres, decorated with small brightly painted wooden carvings, crowns of feathers and bunches of brightly coloured plant fibres and the like. Figure 103 shows four tubuan on the left, followed by a duk-duk, then two more tubuan, two duk-duk, and so on. In figure 104 two duk-duk stand in the middle, and a duk-duk mask stands on the ground at right.

The basic framework of all the masks is a conical shape of thin strips of bamboo (aur). Over this 251they prepare a covering (pakara) out of dyed plant fibres, bast and similar material, which covers the entire head of the wearer of the mask while having extensive, wide holes to allow the wearer to see through, but sufficiently narrow on the outer side to avoid the wearer’s face being recognised. A broad leafy or fibrous crown is attached to the lower edge of the conical hat, completely covering the shoulders. The leafy costume (bongtagul) is made from the leaves of a certain species of rattan (bua). The broad, lance-shaped leaves (magu) are entwined into wreaths (qaqaina) so that the leaves hang outwards; a number of such wreaths wide enough for the upper body of an adult to pass through are attached above one another, and two shoulder bands (taltal) of twisted foliage are attached so that the wearer carries the leafy wrap on both shoulders; further wreaths are put on over the structure just described and completely cover the rest of the upper body and the arms. The mask (lor) with the attached leaf or fibrous crown, for its part covers the head, neck and shoulders.

The full costume, especially in a fresh condition, is heavy and uncomfortable. The wearers swap from time to time or slip into the bush to take the mask off; in such a case they are always guarded by other members to prevent the approach of non-members. During the duk-duk ceremony one often sees natives with severely flayed hips or shoulders, wounds caused by the weight of the heavy mask costume.

The low conical hat of the tubuan is always distinguished by two large eyes (kiok). The long, drawn-out tip (taukane) of the duk-duk mask is decorated in the most fantastic manner; each person tries to outdo the other, and the arrangement of the feather wreaths (pono) or the tiny wooden figures (tabataba) show endless variation.

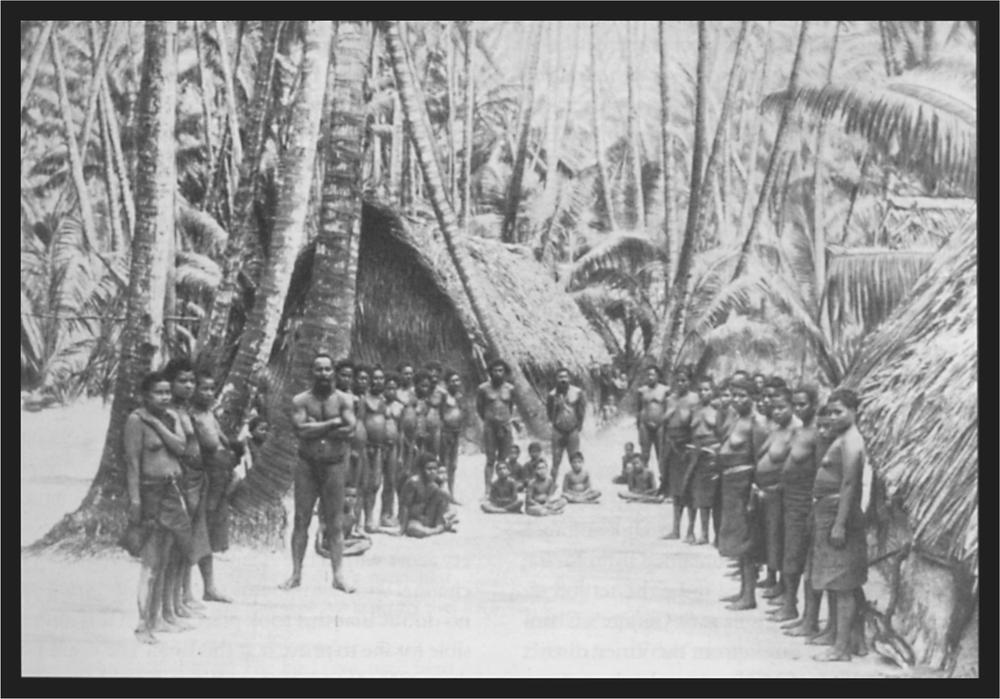

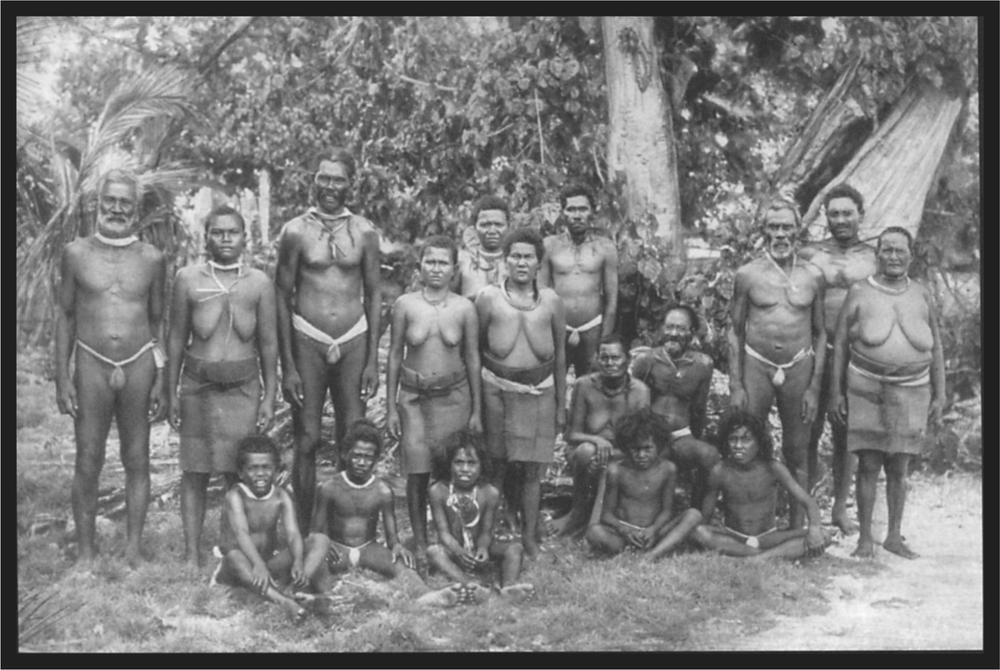

Plate 37 Village scene on Nukumanu

All members of the duk-duk are called a umana lele as opposed to the non-members, a umana mane; the initiation candidates may be young or old. During their novitiate they are known as a umana kalamana.

The tubuan, allegedly a female spirit, is the highest rank in the society. Only quite special natives who, through family inheritance, or through having attained the right of displaying a tubuan through purchase, own one. Every tubuan has its own special female name; for example:

the tubuan of the native Taibuk = ja livuan

the tubuan of the native Tokinkin = ja vagabuabua

the tubuan of the native Toreget = ja muruna

the tubuan of the native Tomararang = ja takin

the tubuan of the native Tangi = ja påk

the tubuan of the native Tendin = ja valval, and so on.

The owners of the tubuan are the wealthiest members of the society in influence and in shell money. Even today the owners of a tubuan can sell the right to other natives who do not yet have one. However, the sale of a tubuan is only possible to a rich man, since not only is the purchase price high but the celebrations connected with the transfer of the tubuan require large quantities of tabu, and it can happen that the buyer comes to recognise that the tubuan does not enrich him as he had hoped but has on the contrary cost him a lot of money. Whoever becomes the owner of a tubuan has taken on the duty of making it appear in a manner befitting its rank, and his neighbours watch that 252this happens. Should he neglect his duty then it can happen that his right is taken away from him.

In the Blanche Bay district as far as Cape Gazelle and the countryside inland, the tubuan and duk-duk institution is still not very old. In the area around Ralum, Tobata, who died a few years ago, first introduced the tubuan, having bought it from the native Tobavaliliu at Talvat on the slopes of South Daughter mountain. The latter in turn had acquired it in the Duke of York group. At Raluana and thereabouts the tubuan was bought at the same time from the island of Kerawara (Duke of York). At Kininigunan, and in the Cape Gazelle region, the tubuan had been introduced from the inland district of Kadakadai. In the Duke of York Islands the tubuan had been obtained from Birara; there, Birara was understood to be the settled region of the Gazelle Peninsula at St George’s Channel. A native named Tarok, from the Virien district on the small island of Mioko, bought the tubuan from the native Taltalut in the coastal village of Landip on St George’s Channel. From Virien on Mioko the duk-duk society has spread rapidly to the remaining islands and, as we have seen previously, from there to those parts of the Gazelle Peninsula which had contact with this group.

The introduction of the duk-duk to Virien on Mioko must have taken place in the first half of the 19th century. On Mioko there is an old man still alive, who, when a boy, knew the native Tarok who had introduced it there. The native Topile, on Kerawara, who died in 1901, told me that his grandfather had bought the tubuan from Tarok in Virien. Other old Duke of York people say, that when they were small boys, the institution was still regarded as a novelty. I can therefore assume with some justification that the duk-duk was introduced to the Duke of Yorks in 1820 to 1830 at the earliest, and from there in 1840 to 1850 to the Mother peninsula and the villages in and around the neighbourhood of Blanche Bay.

The original tubuan of Tarok from Virien was called ja marinair and is still called this today, as far as I know.

The society had also been transplanted from Virien to Laur. The Duke of York natives understood that to be the coast of New Ireland on the far side of St George’s Channel. In this district today they still have the tubuan and duk-duk. The institution seems to occur there only in a very limited district, since only two tubuan are known, bearing the names ja kabange and ja pitlaka.

The Landip natives acquired the duk-duk secrets originally from a place called Kottokotto. Primarily, the region inland from Kabange and Landip appears to be the place of origin of the society; certainly all my acounts from the tribes at the foot of the Varzin and in the Kadakadai region indicate this area. Natives there say that the institution of the tubuan is very old, but make the reservation that there was a time during which their ancestors did not know the secret society. The origin does not appear to lie more than five generations back.

South of the villages on Kabange Bay and south of the Landip district as far as the northern shore of the Warangoi River (Karawat) there is a totally uninhabited region. Also south of the river there is at present no settled population; this is first encountered in the mountains, where we come across the resident south-east Baining. The inhabitants north of the river have no connection with these people. The society therefore can hardly have arisen from direct influence from the southern neighbours.

It is, moreover, hardly acceptable that the society arose within the village communities along the channel without impetus from outside; and I have no doubt that this took place, even if it is not possible for me to prove it at this time. The correspondence of many customs of the duk-duk society with the customs of the secret societies on the Solomon Islands, as well as with the customs of the secret societies of the rest of New Britain, indicates that the initial stimulus came from one or other place. Natives were often driven involuntarily in their canoes by strong winds and currents to other areas, and it would be erroneous to assume that in every case they were slain on arrival in the new land. Such shipwreck victims from other regions may have introduced the secret society, partly to gain status, and partly through the need to preserve their customs. The new institution met with approval and, over the course of time, was then padded out with new additions, new ceremonies and celebrations that corresponded with the new surroundings.

The tubuan is still called turadawai (treetop) by a few old people; likewise one often hears the duk-duk designated as beo (bird). It has not been possible for me to find out anything about the origin and the real meaning of both these designations. Perhaps they are rudiments from a distant region where the duk-duk originally came from. Perhaps also they are only designations of the duk-duk and the tubuan that are used in the presence of nonmembers, since, for everything connected with the two masks, the society members have various names, the significance of which is unknown to outsiders. This naming occurs particularly in the songs which the duk-duk members sing at the masked dance ceremonies when they appear in public. Here words are rendered unrecognisable by special endings, the usual designations of items of daily use being replaced by others, and to the listener, who does not know all of this, the whole thing sounds quite foreign and horrible. Moreover, in these songs I have been unable to find any deeper meaning. Like all other songs, they are simply a stringing together of sentences seldom having any interconnection. In Raluana they have two songs 253that I will reproduce here in translation as examples of the duk-duk poetry. One goes:

Why don’t you stop digging pea (a type of soil)!

Chase away the dimai (a bird); the dimai is ashamed!

This is an old song originating from the time of introduction to Raluana. The following one is of more recent date; it had been bought from a writer in Kininigunan and enjoys great popularity.

Behold the kalangar (parrot)! I admire his head.

Javual (woman’s name, vual = the mist) there on the sea, go away!

Jaquria (woman’s name, quria = earthquake) must shake!

Janatatar (woman’s name, natatar = a particular type of painting of the duk-duk hat), go to the sea!

A storm is drawing near! The bird (beo; used here to designate the duk-duk) with the yellow tuft of feathers.

We want to dance; we want to weep out on the path. Stop! Both of you will hear it again.

The kalangar gets the headband, and all will sit down on the path!

These examples should suffice. All the other duk-duk songs are of the same style and just as unintelligible. When the song reaches the end they begin it over again and the same monotonous singing continues uninterrupted for many hours.

Normally in everyday life singing is kakaile, but the duk-duk society has a special name, tapialai, for its songs.

The initiation ceremonies in the Duke of York Islands and on the Gazelle Peninsula are generally the same. Here and there they have developed slight variations, according to whether the members of the society or the owner of the tubuan had more or less of a sense of the miraculous. In the districts round my dwelling the introduction proceeds as follows:

Should a male child, a boy or a youth, be accepted into the society, the father or the uncle of the person in question announces this to the owner of a tubuan. Usually the latter lets some time pass before announcing that the tubuan will appear at such and such a time; this appears to be out of regard for the members of the society who are planning to take in a novitiate, to give them sufficient time to make the necessary arrangements.

When the day of the appearance of the tubuan arrives, its loud calls on the taraiu are heard, and this is the sign to bring the novitiates. On the taraiu they lie down in a circle; the tubuan armed with a light stick dances in the middle of the circle yelling and gesticulating and strikes the novitiates with the stick; the members standing outside the circle do this too. They are very considerate in the distribution of blows; children and small boys receive gentle blows, bigger boys and youths, however, receive a rougher beating, which seems very similar to a severe thrashing, and this ceremony (bakatia) therefore seldom ends without yells of pain from the novices. The mother and female relatives sit at home in their huts during the proceedings, uttering cries of suffering.

After the bakatia, the sponsors, father or uncle, share small amounts of tabu about a span long among those present; obviously the tubuan receives a greater length, but never more than a metre long. Then the novices are given a meal specially prepared for this occasion (rang davai), consisting of fish, baked taro and the like.

When the meal is ended, the novices must again sit in a circle on the taraiu, and the tubuan steps into the centre, removes his conical head covering, then one of the wrapping rings of foliage, then another, and so on until he stands there totally bare. Pointing to the costume he then calls out: ‘What do you want to do with it? Put it on, put it on!’ But he has previously removed the straps of foliage, taltal, which pass over the shoulders holding the leafy wrap fast, so that the novitiates come to the conclusion that the entire costume, bongtagul, hangs from the body as a result of spiritual influence, without any other support.

After this small comedy, the men dance on the taraiu and the novitiates are taught how to make the leaps and steps of the duk-duk. The whole ceremony is called palatutane.

In the meantime it is impressed upon the newcomers that they are to say nothing about what happens on the taraiu, and the threatened punishment for violation is put before them. Then a sumptuous feast, aingir, prepared by the relatives of the novitiates, is consumed by all those present on the taraiu.

The initiation is then actually completed, although a series of further ceremonies follows. If the newcomers are still small boys, they must wait a number of years until they receive their own duk-duk, but if they are about twelve years old they obtain one immediately and go through all the ceremonies at the same time.

The conferring of a duk-duk ensues the day after the new birth by the tubuan. On the day of the actual birth of the duk-duk, väkua, the fathers or uncles bring the duk-duk costume, prepared meanwhile in secret, to the taraiu, from where the tubuan gives his loud cry, i puongo, accompanied by the loud din of the wooden drums, kuddu, announcing the birth, kinavai, of the duk-duk. The novitiates too gather at the taraiu where they remain throughout the night.

On the early morning of the following day, the tubuan with his newborn children, the duk-duk, presents himself to the public. If the taraiu is on the beach or close by, the tubuan and the duk-duk get into festively decorated canoes, and they are 254paddled along the beach by unmasked members, dancing and singing, accompanied by drumbeats. This is the matamatam (fig. 105). The appearance of the tubuan with his newborns is called a bung na kinavai, or tubuan i kakawa. Now and then it happens that the canoes in which the masked people have been paddled along the beach are wrecked. As soon as the masked people have left their canoes the duk-duk members pounce on these, smash them up and scatter the fragments in all directions.

Fig. 105 The duk-duk presents itself on the water

At such celebrations there is always only one birthing tubuan present; however, several of them are always seen at the feast. With the exception of the one, the others are mere participants in the feast, from neighbouring districts.

When this duk-duk performance is completed, all the feast participants – that is, the old members as well as those newly accepted – go onto the taraiu; from here the procession, consisting of all those wearing masks and all other members, sets out to the feast place of the owner of the tubuan. At the very front those tubuan present march and leap, then the duk-duk follow, usually in pairs. The whole crowd of members follows behind and alongside, yelling, singing, drumming and throwing burnt coral lime into the air with both hands. Dances are performed on the feast place by the masked people, and members and non-members, women, girls and young children, who have come from throughout the district, lie around watching the leaps.

After the dances, there again follows a small comedy to give the non-members an idea of the power and strict rules of the duk-duk within the society.

The tubuan present grip fairly thick banana trunks, and the unmasked members leap around, to receive a hefty loud-sounding blow on the back, a virua na pedik. This is not so dangerous as it seems, for the juicy banana stem cracks very loudly on the bare skin and the blow may be quite painful for an instant, but goes away in a few minutes leaving neither swellings nor skin grazes. Those struck hide the pain, laugh and make jokes, also grabbing the banana stems and dishing out friendly, neighbourly blows that are always reciprocated, everything giving the impression that they are immune to pain and make nothing of such small things. The wives and female dependants of the victims screech out loudly during this scene and for a while the din is deafening.

After this small comedy has ended, all the tubuan and duk-duk arrange themselves in a broad circle, and the owners of the active tubuan stand in the centre of the circle. Immediately, there is an absolute hush (Papua Album, vol. I, plate 15). Tabu is now brought out and handed to those standing in the centre. Immediately, the masked men sit down on the ground, and 3 to 4 metres of tabu are handed out to each of the newborn duk-duk. This is also a comedy piece for the benefit of the spectators, to show how advantageous it is to be a member of the society. This public display is called navolo or naolo. Afterwards everyone, including the new members, goes back to the taraiu, the masked men remove their costumes and, after the day’s activities, everyone fortifies himself with food that has been brought earlier by the relatives of the new members.

The following day the duk-duk begin the gathering of tabu, ivane na dok-dok. The new member accompanies the duk-duk, together with several friends and relations, who must all be members, probably to monitor the income; if the bearer becomes tired he slips into the bush, rapidly removes the costume, and another immediately puts it on to continue leaping and to announce his arrival by his loud barking call. During this period the new member does not put the mask on, although he always accompanies his duk-duk and sleeps in his company at night on the taraiu. Day by day the various compounds in the neighbourhood are visited and everywhere a large or small gift of tabu is collected. As a rule this lasts for about a month, but under certain circumstances this can be twice as long.

Often a wealthy native provides a special feast on the taraiu for the duk-duk, then he leads them to his hut and hands them the usual gift of tabu, a tabu na duk-duk (in contrast to the tabu that has to be paid to the tubuan and is called a tabu na tubuan).

During this collecting time a good attendance predominates on the taraiu; the members are always here in great numbers, and the father, uncle and relatives of the new entrants must therefore ensure that there is always enough food available. Supposedly, this is destined solely for the tubuan 255and must consist of special morsels, fish, chickens, baked taro tubers over which grated coconut has been squeezed, all kinds of vegetables, and so on. This festive food is called kirip.

After the tabu collecting has gone on for one or two months, the owner of the tubuan announces the end of the festival. All members, both masked and unmasked then gather on the feast place of the owner of the tubuan where after a short dance they sit down on the ground. The father, the uncle and the other male relatives of the new members bring them, or more accurately their duk-duk, gifts of tabu. Father and uncle pay 1 to 2 metres of tabu, more distant relatives a shorter length, which is laid in front of the duk-duk, tied to a bright Dracaena branch. The women send great bundles of prepared morsels which are all taken to the taraiu later. This day is called a bung dok varvaki. After the distribution of presents, all go to the taraiu again; and then the duk-duk is dead. The tubuan on the other hand never dies, he is always there; he appears now and again on appropriate occasions where he has direct involvement; he is immortal.

On the taraiu the masks are now dismantled. Everything that has value in the eyes of the natives, such as bright feathers, wood carvings, and so on, is stored; the rest, particularly the leaves of the costume, the framework of the conical hat, and so on, is stacked in the huts under the rafters and elsewhere.

After the death of the duk-duk everyone goes home, but the event is not ended by a long way, for, several days later, there follows the actual settling up. On the third day after the death of the duk-duk all those who have assisted in the ceremonies gather in the home compound of the newly admitted member. Each person receives a gift, whose value depends on how much tabu the duk-duk collected. The costume-maker receives a piece of tabu 2 to 3 metres long; the people who have worn the masks during the assemblies receive a similar amount. This distribution is called war ma momoi. It goes without saying that a sumptuous feast, dodoroko, is also provided for.

The following day all the members assemble on the taraiu; both this day and the celebration taking place are called tar kulau. The celebration consists of the father or uncle of the newly inititated going up to him and handing him a certain number of young coconuts, kulau; each nut represents 10 fathoms of tabu. Therefore, if the uncle hands his nephew three nuts, it means that the latter has to reimburse him 30 fathoms of tabu for his outlay. Often the father or uncle takes one or more nuts back and silently drinks it; this signifies that the newcomer must indeed hand over the requisite number of fathoms of tabu, but the drinker will contribute as many times 10 fathoms as the nuts he has drunk. The more tabu the new member must pay, the higher his rank. On the settlement day, wealthy people present up to 100 fathoms of tabu; however, this is only boastfulness, for the shell money eventually goes back to them. The duk-duks, purchased for a large sum, are called kabin e rak-rak. They sit beside the tubuan at the feasting places and receive the best morsels of the feast. The rest, who deposit the usual payment of 20 to 30 fathoms, are called a ni koro.

Fig. 106 The duk-duk lands on the beach

As a rule, the new entrants have not gathered sufficient tabu to cover all the expenses of their sponsors. In this case they must then work to accumulate the necessary sum. If father or uncle have no money to afford a contribution, perhaps have even borrowed funds from wealthier natives, it may be two or three years before the person in question has gathered the full sum; he must therefore establish gardens, go fishing; in short he must gain money by any means. When, finally, after a lot of effort, he is the happy owner of the whole sum, there comes the great day of settlement, a bung anidok. Father or uncles prepare a great feast, which is brought to the taraiu. Here the members gather, and the full sum of tabu, bound together with a bright Dracaena leaf, is handed over by the entrant in question to his father or uncle. As mentioned above, father or uncle, to enhance the standing of the new entrant, often gives a large part of the abu, but accepts the whole amount for himself and stores it as tabu na duk-duk of the newcomer.

The feast on this occasion is so sumptuous that they can often eat for eight to ten days on the taraiu. During this period the tubuan also appears on the taraiu, gives his loud bellowing cry and receives a gift of a piece of tabu 1 to 2 fathoms long from each of the new entrants. The remains of the duk-duk masks, stored up till now in the huts, are then burned, va pulung or pulpulung, and the newcomer is now a fully fledged member of the society.

Now that we have learned about the full initiation customs in the preceding passage, many aspects of native behaviour that had earlier seemed unreasonable and unfair become clear to us. We now understand why the uncle or father hires out his nephew or son to strangers and later takes his pay; we also understand why the young people are not allowed to choose to go off here or there to 256avoid their duties; all this is to guarantee that the relatives recoup their outlay. The person accepted into the society can never be tossed out of it; he enjoys all the advantages of the society throughout his life, namely participation in numerous ceremonies that, with the obligatory feasting, would otherwise have been inaccessible to him. Also, in the event of need the tubuan and the whole band stand behind him, taking him under its powerful protection should the need arise. It cannot be overlooked that the society exercises a significant educative influence by compelling the young people to silence, obedience and work. In my opinion, this situation could be further expanded and valued by a prudent authority or by the missionary societies as an educational factor.

The position of a duk-duk in the society is clear from the preceding passage: he is a subordinate member to whom the membership accords certain prominence. His superior, to some extent the guiding principal in the society is, however, the tubuan. It remains for us to define more precisely the position and the significance of the tubuans to own a tubuan, then the owners must gain significant benefits, although they distribute tabu with apparent liberality and take other expenses upon themselves. Given the covetous nature of the natives, they would not do this if they did not have a view not only to covering their outlay but also to making a fine profit. The apparent largesse is based on the spender knowing full well that he will recoup the outlay with interest. During the initiation ceremonies as we have already seen, many pieces of tabu fall to the tubuan in respect of this ownership, but this amassing alone would not recoup the massive outlay. However, besides this, the tubuan has many ways and means of not only regaining his costs but of drawing pecuniary profit from the power bestowed on him by public opinion.

First, the tubuan has the right to exact punishment, which as a rule consists of the payment of tabu, collected by him in person. Should someone speak improperly about the tubuan or about members of the society, the tubuan is immediately on hand to collect tabu. In particular, women and non-members frequently feel his heavy hand. But members, too, who have transgressed in any way against the rules of the society are called to account and submit tacitly, as we have seen demonstrated, for behind the tubuan stand the duk-duk, forming a solid structure, to some extent representing public opinion, against which the influence of an individual is powerless.

In a district like, for example, the north-eastern corner of the Gazelle Peninsula, where no actual chief is recognised, the tubuan represents the principle of social order and conventional justice and looks after the maintenance of this. Now the native concepts of law and order are often very indeterminate, and are in many cases overcome by the feeling and consciousness of power and might, so that indeed nowhere else is the principle: ‘might is right!’ so conscientiously followed than in the exercise of the rights befitting the tubuan. This makes him feared, but everyone complies with his orders because resistance to the tubuan would lead to even more powerful repression, possibly even to loss of life. If the owner of a tubuan is a liberal man (that is, a native who is less covetous than his neighbours), then the rule of the tubuan is relatively mild. An acquisitive tubuan on the other hand conducts things terribly, and it can happen that the members themselves grumble about the heavy pressure brought to bear even on them, and finally tubuan from the neighbouring districts bring the situation back to normal. By and large, however, one could maintain that excesses by a tubuan are a rarity; the most recent was over 20 years ago. The influence of settlers, missionaries, and the administration has moderated the tubuan, and his activities must now be designated as very mild. Our concepts of right and wrong are so totally different from those of the natives that we often regard a punishment imposed by natives against natives as hard and unjust. In spite of this we hear no grumbles on the part of the one punished, because according to his concepts of justice he regards the punishment meted out to him as just and fair. In reverse, European justice appears to the native quite often as a shocking injustice, and he bows to it only because he knows that power is on the side of the magistrate. Thus, in most cases, the government of the natives is a covetous and hard-hearted tubuan against which nothing can prevail: at the end is open rebellion, and when it gets to this point the situation must be far gone.

To some extent, as the highest instance of jurisdiction, the tubuan has ways and means of protecting property. He guards taro, yam and banana plantations, protects individual trees and large stands of palms, and achieves all this merely by setting up a simple sign, consisting of a bundle of grass, a plaited coconut frond, several brightly painted coconut shells, and so on, on the item to be protected. This sign is the tabu sign of the tubuan and is rigorously respected out of fear of his vengeance. The owner of the item under protection pays the tubuan a certain sum of shell money for his efforts.

On the death of wealthy natives (plate 43) or at ceremonies to honour the ancestors (Papua Album, vol. I, plate 16) the tubuan can never be missed out; he exalts the ceremony or celebration with his dances, his mysterious disappearances and appearances evoke wonder and fear, but he makes sure that he is well paid for his efforts.

Although the tubuan primarily rakes in money for his owner, he still does not forget his children, the duk-duk; for the principle holds: ‘Live and 257let live!’ and, in addition to the feasts and dance entertainments, many remnants of shell money fall to the duk-duk, most especially in the initiation of new members, but also in the collecting of fines.

Previously, violent acts would also have occurred against women and girls. Such a case never came to my knowledge, and old members also deny it. Today, certainly such behaviour no longer occurs, although, in the districts round Vunakokor, the tubuan still appears domineering and violent, and the administrative authorities do not make much difference.

From the preceding paragraphs it is evident that in reality the duk-duk society does not impart secrets or extraordinary knowledge to the new members. It may be that the initiates have now come to the conclusion that all that happens on the taraiu and under the jurisdiction of the tubuan and duk-duk masks is not the work of spirits but of quite ordinary men, a revelation which of itself may appear astonishing enough to the newly initiated.

A peculiarity of the Gazelle Peninsula are the skull masks, about which a lot has been written in the ethnographic literature, related to hypotheses with which I cannot agree.

Because the masks are made of individual pieces of a human skull, and because the skulls of the dead play a special role among peoples of nature (and here and there among the Melanesians), these skull masks signify something absolutely special. Although the natives, the makers of these skull masks, know nothing of these kinds of deep meanings, they do not want this to be recognised, and support this by saying: ‘The present natives know nothing at all about the deeper meanings, but this is because, over the course of time, they have been forgotten!’

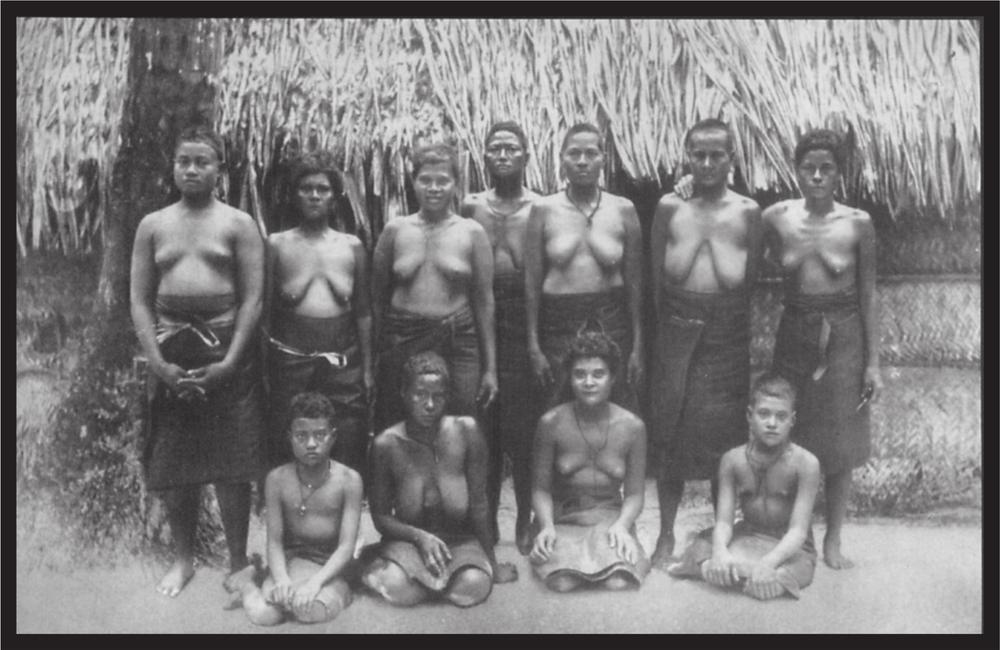

Plate 38 Women on Nukumanu

In volume X of the Publikationen aus dem Ethnographischen Museum zu Dresden, I have attempted to remove the enhanced significance of these masks, especially to disprove their connection with ancestor worship and honouring of the dead. However, new theories always emerge, finding apparent confirmation in some observation by a traveller or a missionary, who could have considered the matter only quite superficially. In volume XI of the Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, Herr L. Frobenius maintains the deeper significance. In volume XIII of the Dresdener Publikationen, Herr W. Foy introduces a comment by by Father Fromm, probably with the intention of connecting the skull masks to ancestor worship. Father Fromm says in a letter published in the Marien Monatsheften 1899 that a skull mask was shown to him by natives going to a dance, with the words, ‘Here, this is his father’, pointing to a young man who stood nearby; several were also offered for him to buy. It is quite possible that the mask in question was made out of the bony skull of the father of that young man. The natives have, I have observed on countless occasions, so little respect for the remains of their fathers and relatives that it is entirely possible that the young man himself or someone else among his compatriots had 258uplifted the skull and made a mask from it. I have obtained numerous skulls from natives and know that fathers sold the skulls of their sons, and sons the skulls of their fathers, laughing, for a pittance. The son scarcely regards his father as a relative, and would never store his skull as something special.

Certainly a kind of skull cult is known on the Gazelle Peninsula. Skulls of wealthy people who have left a lot of tabu, are exhumed after a certain time, placed on a frame and ceremonies take place. However, this has absolutely nothing to do with the skull masks. These are the products of a very specific district, and I have succeeded in localising it precisely.

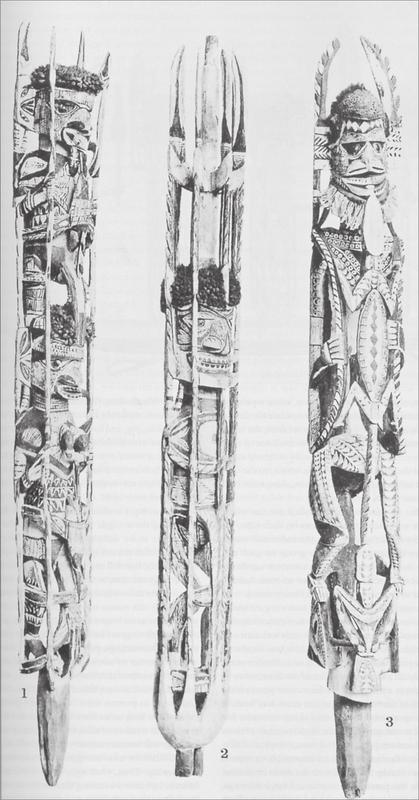

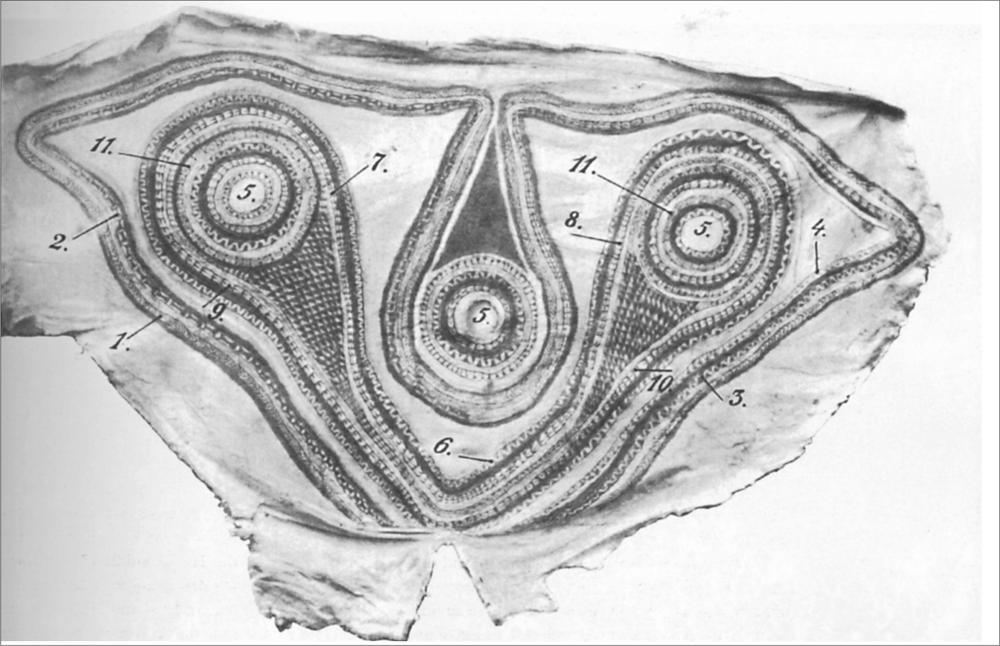

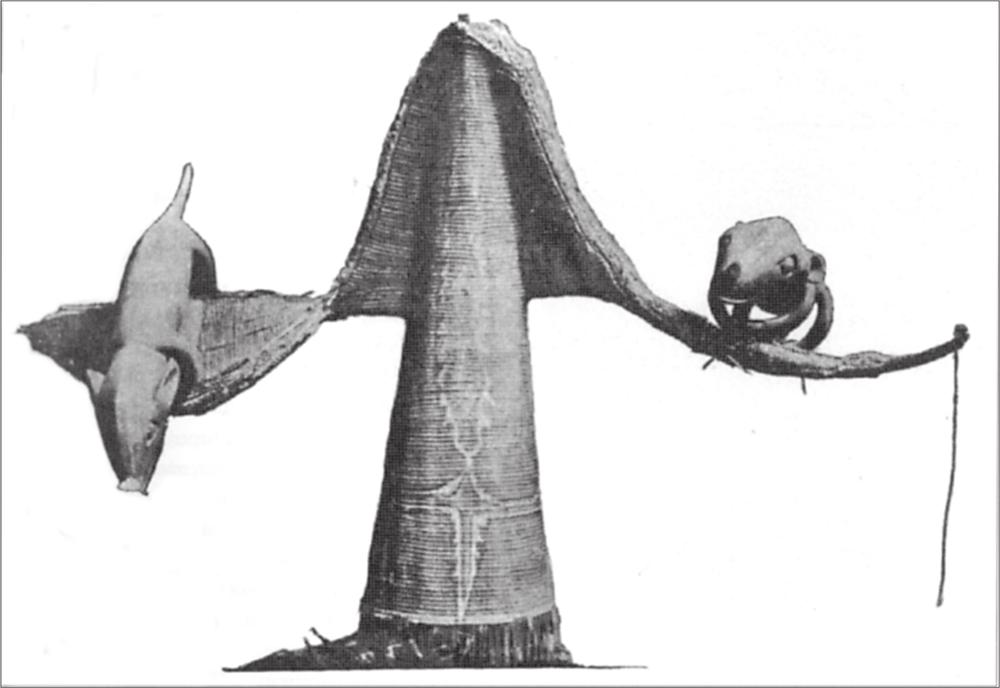

Fig. 107 Skull masks from the Gazelle Peninsula

The skull masks (fig. 107) are made from the frontal and facial bones and mandible of a human skull. In order to achieve the greatest possible similarity with the face of a living man, the outer surface is coated with the crushed pulp of the Parinarium laurinum nut and then painted. Often the face is framed with a beard either formed from Parinarium pulp and then represented by painting, or made from actual human hair; and frequently also from pig bristles or stiff plant fibres. The same applies to the hair of the head, either made from real human hair or from plant fibres. Occasionally a piece of bark material extends from the upper edge of the mask covering the wearer’s head. The mask is either held in one hand in front of the face, or a wooden cross-brace is fixed to the reverse side and gripped by the wearer’s teeth (see the middle mask in fig. 107). The older masks look very realistic and are difficult to obtain today. The more recent masks are prepared far more crudely. I am, to some extent, of the opinion that the masks are still used today. When I arrived here in 1882 I made inquiries, and found that the skull masks were already dying out. High prices of tabu brought me several beautiful old specimens, and, enticed by this, they resorted once more to manufacture in order to sell the product to warships and other visitors. The modern work is easily distinguished by an experienced person from the old genuine articles.

Use is manifold. When the shell money (tabu) is distributed at weddings the distributor holds the mask (lor) in front of his face during the distribution. After the distribution he puts it aside again. A further usage is that during feasts certain people, holding such a mask in front of their faces, make their way onto the feasting place and receive a portion of the food as a gift, to which, unmasked, they would not be entitled.

Earlier they are said to have worn the masks in dances; in spite of repeated assurances, this was not clear to me for a long time, for the natives always sing when dancing, and gesticulate with hands and arms, so that they would hardly be able to hold a mask in their teeth or keep it in position with their hand. Dancing with masks has been described to me by reliable sources as a slow, silent wandering round by the wearer while another part presented the usual noisy dance.

The home territory of the skull masks encompass the districts on the high plateau between Weberhafen and Blanche Bay, and the custom is restricted to this area. It is certainly not excluded that, in earlier times, the skull masks had been connected with a certain type of ancestor worship, but what one reads about this in various works is based exclusively on hypotheses that find no confirmation in statements by the natives. There is no item about which I have enquired more extensively over the last twenty years than these masks; and it would be incomprehensible if during this whole period not a single fact came to my ears indicating a higher significance, if one actually existed. Again and again from the most diverse quarters I heard the same details confirmed, and I believe that one can finally withdraw the skull masks from their attributed high significance without any damage to ethnology.

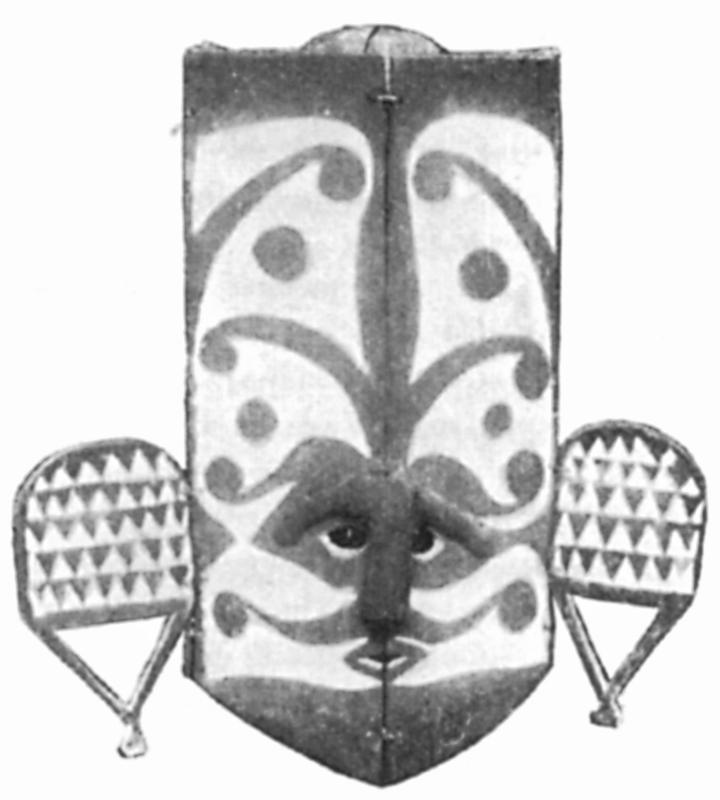

As well as the duk-duk masks and the skull masks, 259face masks are also familiar on the Gazelle Peninsula, all given the name lor; that is, skull. They are, as a rule, very simple, consisting of a curved board in the shape of a face with a carved nose, a slit for the mouth and round eye holes. The background painting is white, and black and red stripes mark the individual parts of the face. They are, as a rule, provided with a helmet-like frame densely covered with fibres, representing hair; the form strongly reminiscent of the helmet masks of New Ireland. Without doubt these masks are a remnant of earlier, now gradually disappearing, customs. Today they are used only for dances that are designated as malangene taberan (that is, spirit dances), but nobody now knows which spirits they represent. However, these dances also have the character of all other vulgar dances; they are presented publicly for the amusement of those present, be they men or women, and no special regard is given to the masks themselves. A carry-over from old times, which likewise points to New Ireland, is that the dancers cover themselves with a loincloth or skirt of ferns, extending from the waist to the knees, just as we see during dances to honour the dead on New Ireland. This last circumstance is, for me, overwhelming evidence that we have before us the rudiments of a very old custom, which the original immigrants brought with them from their homeland on the far side of St George Channel. In all other dances, the inhabitants of the Gazelle Peninsula, from the Duke of York Islands to New Ireland, are completely naked, with the exception of the bunch of bright leaves and flowers that serves as a headdress. In the great dances to honour the dead on New Ireland the dancer wraps himself in such a leaf garment. This custom has been retained as a peculiarity on the Gazelle Peninsula where otherwise the total nudity of both sexes was customary only a few years ago, although the significance of the dance and of the masks has passed a long time ago into oblivion.

They have another kind of mask in Kadakadai, an inland district of the Gazelle Peninsula. These are similar in construction to the previously described masks, but with the difference that the face has a grotesque appearance from a dense plastering of lime with bulges of vegetable resin laid on top. Crooked noses and oblique mouth or eye apertures, enormous eyebrows of plant fibre, fantastic beards and the like are characteristic of these masks. They are actually helmet masks, covering the entire head, and bearing a fibrous trim on the lower edge, falling over neck and shoulders. This mask too represents a spirit, but nobody today has more detailed information. It is not impossible that this mask is the forerunner of a tubuan mask with which it shows many similarities. Also Kadakadai is a district adjoining the region from which the tubuan and duk-duk seem originally to have come. A certain interdependence between these masks and the tubuan seems to have existed until not long ago, according to comments by several old natives, in that at the appearance of the tubuan such masks came running a short distance in front of him, with a lot of noise, announcing his arrival so that women, children and non-members could quickly take flight.

Masks from that area, of which about twenty years ago I caught a glimpse, were real masterpieces as caricatures of a man’s face. No two were alike; each one had a different aspect and small disfigurements or weaknesses were reproduced in such grotesque form and with such a sure feeling for the ridiculous and the exaggerated that it would be difficult, even for the most earnest, to look at them without smiling. The dances of the natives are, as a rule, quite monotonous and boring, but a dance by the Kadakadai people with these masks belongs among the most delightful that I can recall during the many years of my stay in the South Seas. What is made today is amateurish compared with the earlier items, and is at a much lower level both in presentation and in interpretation.

Of far greater significance to the population of the north-east of the Gazelle Peninsula than the duk-duk institution is the men’s secret society designated by the name marawot, or ingiet. The duk-duk society could be removed without any difficulty by an administration ban, although no small disturbance might arise in all the native social institutions based on, and connected to it, but in time these would subside and be overcome. Marawot and ingiet, however, are so deeply ingrained in the whole spiritual life of the natives that no official order by the administration and no persuasive powers of the Christian missionaries would manage to root out the institution. Like so many old heathen customs still flourishing in secret in Christian lands despite centuries of persecution and combat, the ingiet institution too would continue in New Britain and only cloak itself in even greater secrecy than is the case today.

Marawot and ingiet have nothing in common with the duk-duk and, while the first-mentioned is of fairly recent date, the second institution extends far back into the people’s past.

Marawot, in many places moramora as well, is the name of the site where the men gather; the site on which the dances, also called marawot, are performed is called balana marawot (balana = stomach, midpoint). Ingiet, or in other writings iniet or ingiat, is both the name for the dance of the initiated and, above all, for the society.

By far the largest number of male natives belong to the marawot or ingiet and call themselves ingiet. Boys are taken into the society even during childhood although they only learn and take part in the actual dances later.

The initiation seems to be without special ceremony; it is sufficient that the father or uncle of the 260native, who is in possession of the ingiet secrets, makes a small payment of tabu. The amount varies from a metre-long section to several fathoms. During the dance presentation the initiates squat in a hut where they are hosted by the older members. The real ceremonial place, the balana marawot, with the hut on it, is surrounded by a dense, high fence so that the uninitiated women and children cannot see the events going on there.

Only very special people can share the secrets of the ingiet. Each of these persons has their special ingiet which they own. Initiation into an ingiet permits entrance to all other ingiet societies. The dance, with slight variations, is virtually the same everywhere; on the other hand, the words of the accompanying song vary. It requires long intensive practice to dance the marawot correctly, and to learn the precision of the measured arm and body movements and the simultaneous stamping on the ground.

It is quite difficult to obtain reliable information about the institution but, by and large, one can characterise the society as one which gives the initiates the right to associate with the men, but more particularly introduces them to all kinds of sorcery, and acquaints them with numerous spells, including those which have the purpose of bestowing domestic happiness, family success, protection against illness, of conjuring up evil spirits, or of invoking sickness, death and ruin on neighbours.

The natives also distinguish several main types of ingiet, namely ingiet warawaququ (ququ = to be joyful, to be happy), or the spell to make happy and joyful, also known as moramora; and in contrast ingiet na matmat (mat = dead), or the death-bringing spell, also called winerang. Each of these main types has special gradations with corresponding names. A native who is initiated into all the different ingiet and has knowledge of all the magic formulae stands in high regard.

I have been present at numerous ingiet gatherings, and in the following section I want to describe several features in greater detail.

One such gathering was an ingiet warawaququ. A tall, dense fence of coconut and other palm leaves was erected in a clearing; the completely empty rectangular space within measured about 30 metres long by 10 metres wide. An open hut of the usual local construction stood at one end. The narrower end of the fence, opposite the hut, was neatly made from woven coconut matting; the mats were decorated with black, red and white paintings. These represented male figures with the characteristic legs bent at the knees and bent arms pointing upwards. Both longer walls were decorated with all kinds of bright leaf material, flowers and garlands of feathers, all producing quite a pleasant impression. Outside this enclosure, balana marawot, had gathered a large number of natives from the surrounding districts: ceremonially decorated men, youths and boys, as well as numerous women, who had brought large bundles of prepared food wrapped in banana leaves.

From the balana marawot there sounded a loud unintelligible song in the highest falsetto and the men and boys standing outside immediately went through the narrow entrance onto the site, which was soon filled to overflowing. The boys being admitted took their places with their male relatives in the little hut. Opposite the hut with their faces turned towards it, the decorated men gradually arranged themselves into several rows side by side, and on a given signal the dance began, with the wooden drums and a song providing the beat for the dancers. All the dancers joined in the song in the highest falsetto, which would have made great demands on the vocal chords. It ended suddenly, for the time being, and a single native then recited a number of sentences, also in a falsetto and with astonishing volubility, after which singing and dancing resumed as before. By and large, the dance did not differ from the other public dances, with the exception that from time to time all the dancers stamped their foot a tempo very hard on the ground several times, giving rise to a far-reaching droning sound. After each footstep a deep guttural sound was expressed in unison. This stamping was given the name rurua. The other movements and figures of the dance, warawaqira, the bending of the trunk, and the arm and hand movements were presented with astounding precision which indicated extensive practice, and could not have been executed better by a trained corps de ballet.

Another characteristic of the dance was that from time to time it showed a tendency toward obscenity, although this never degenerated but was always only hinted at; perhaps only in order not to arouse the displeasure of the European present.

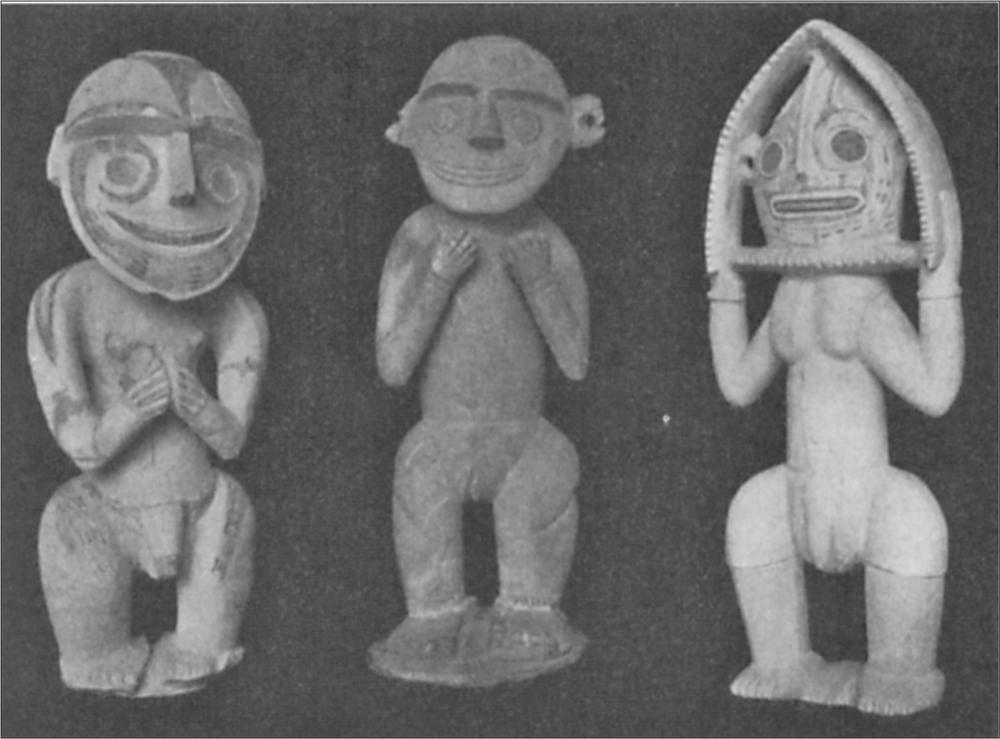

After a dance had ended, the dancers, streaming perspiration, walked off the arena, and new ones walked on. This went on for several hours until all the groups assembled had presented their songs and dances to the best of their ability. Then the new members came out of the hut with their relatives and laid down the novitiates’ entrance fee, ![]() at the opposite end of the enclosure. Several of the earlier dancers then approached those newly admitted, holding a carved wooden board, tabataba, in each hand; they made a movement with this as if they wanted to bore through the boys, while saying: jau tung tamam (jau = I, tung = to make a hole, tamam = your child). Others brought spears, little bunches of bright feathers, necklaces and headbands, which they handed over to the new members, with a view to receiving the usual sum for these items in shell money later, by way of a reciprocal gift from the parents or uncles. On the ceremonial site human figures are occasionally erected, also bearing the name tabataba. They can 261hardly be called idols, since nobody pays homage or worships them. They are figurative representations of the spirits of highly regarded members of the society intended to be honoured after death, and always have only transitory significance for special ceremonies. Previously they made grotesque figures out of a soft tufa for the same purpose, and several of these came into my possession. The present generation does not recognise such figures, and only a few old men were able to impart the actual significance of the figures to me.

at the opposite end of the enclosure. Several of the earlier dancers then approached those newly admitted, holding a carved wooden board, tabataba, in each hand; they made a movement with this as if they wanted to bore through the boys, while saying: jau tung tamam (jau = I, tung = to make a hole, tamam = your child). Others brought spears, little bunches of bright feathers, necklaces and headbands, which they handed over to the new members, with a view to receiving the usual sum for these items in shell money later, by way of a reciprocal gift from the parents or uncles. On the ceremonial site human figures are occasionally erected, also bearing the name tabataba. They can 261hardly be called idols, since nobody pays homage or worships them. They are figurative representations of the spirits of highly regarded members of the society intended to be honoured after death, and always have only transitory significance for special ceremonies. Previously they made grotesque figures out of a soft tufa for the same purpose, and several of these came into my possession. The present generation does not recognise such figures, and only a few old men were able to impart the actual significance of the figures to me.

The women gathered outside were meanwhile conducting a lively trade with the morsels they had brought, which the dancers made short work of, once their task was done.

These ceremonies often last for several days on end.

The new members are henceforth ingiet and cannot eat pork for the rest of their lives, since an evil spirit lives in the pig and is summoned for the purposes of sorcery at other ingiet gatherings. At later assemblies they learn the dance and various songs, and are at the same time initiated into the mysteries of certain magic spells.

In the instance previously described, the magic spell is of the utmost simplicity. It consists of the words: ‘A bul i manamana jau!’ It is a spell by which all evil spirits are supposed to be driven from the compounds and dwellings and, most importantly, from the family. It is performed by the person in question taking a branch of the Karongon bush in his hand and waving it to and fro with outstretched arm over the place to be protected, and touching it on the people and items to be protected while rapidly reciting the spell and repeating it many times.

Besides the previously described ingiet warawaququ there are a great number of similar spells for averting the influence of evil spirits and attracting favourable and gratifying living conditions. It is up to each person how many of these magic spells he wants to learn; after the initial introduction he has the right to take part in all other marawot and learn the special incantations and accompanying hocus-pocus there, paying the owner of the spell, of course.

All of these marawot or ingiet have different names; for example, balu (pigeon), qelep (species of palm), tagir (fruit of the Eugenia malaccensis), varpidak (the name of a certain native), läkeläke (to pass over something or to progress), and so on. It is not always obvious how these names are connected with the ingiet. In one case, varpidak is the name of the discoverer of a certain spell, and also its name. Läkeläke, to pass over something on the path, is a designation that is evoked by the way in which the charm works; the charm is laid on the path while murmuring the spell, and becomes effective as soon as the person to be charmed steps over it. I have never fully understood names like balu = pigeon, qelep = species of palm; it seems to me that they are words that the initiated men use to designate something special which is unknown to the women in the vicinity.

It was far more difficult for me to gain admission to the places where ingiet na matmat, the death-bringing spell, is taught.

Admission here is exactly the same as for the ingiet warawaququ or moramora, with the exception that women are kept strictly far away, and the participants, as well as the new members, must fast from early morning, and can take betel nut or food only after the conclusion of the marawot.

I was led by a member to a place in the forest, far away from villages and compounds. The site was set up temporarily for these special purposes; the paths leading there were barely recognisable. From far off we heard the high falsetto singing intermingled with the dull stamping of the men, repeated from time to time.

On the assembly place one is confronted first of all with the usual picture, the presence of numerous ceremonially decorated participants who performed their dance closely crowded together. All kinds of figures were carved into the bark of the trees round about, some easily recognisable as sharks, snakes, stingrays, lizards, and so on, but several required explanation before one understood that they represented ravens, dolphins, wallabies, and so on. These tree carvings were made to stand out more clearly with black, red and white paint.

In the middle of the site stood a tree trunk, which was buried with the stump end in the ground so that the roots with all their branchings and fibres soared about 2 metres above ground. The tree used for this is called kua. Decorated men, dancing and singing, moved in a circle around the tree stump, holding a small bundle of leaves that they laid on the ground around the upside down kua stump at the end of the dance. Then they chewed betel.

The assembly was, as I found out, a very special secret, and took place in such an isolated spot because a spell was taught which had the aim of killing an enemy at will by enchantment.

For this purpose the sorcerer must get possession of the puta of the person to be enchanted. Puta is anything that is or was connected with his body; a portion of his saliva, his excrement, his food, his hair or beard, even the earth in which his footsteps have left visible impressions. It is therefore no wonder that the natives conceal or destroy these items most carefully, or smudge any traces of them. After he has obtained the puta, the one who wishes evil wraps it in various leaves, the scraped bark of certain trees, soil, and so on, inside a betel leaf.

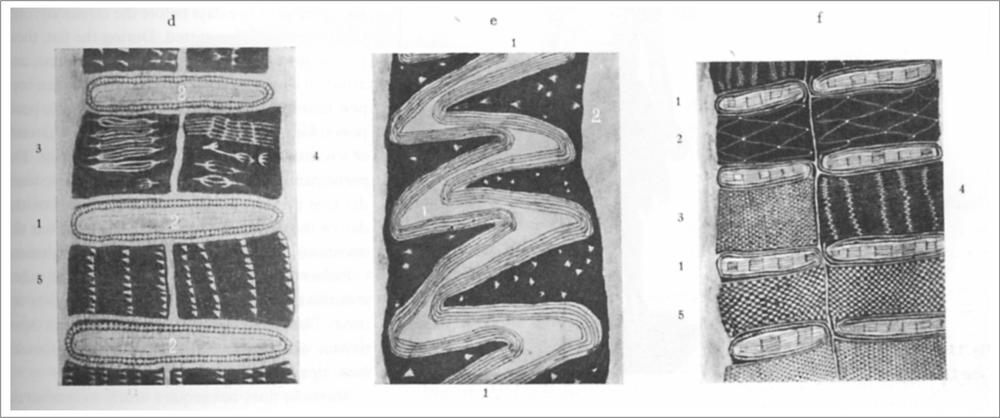

He then steps out in the line of dancers on the assembly place, holding the little bundle in one hand, and a carved and painted little board, the 262tabataba na kaiya in the other. All of those wooden figures depicted, for example, in the Dresdener Publikationen, volume X, plate 15, figure 3; plate 16, figures 1, 3 to 11; plate 18, figures 1, 3 to 5; volume XII, plate 7, figures 1 and 4, are tabataba. A tabataba na kaiya is a little wooden board on which the evil spirit kaiya is depicted either by painting or carving.

The little bundle with the puta is swung to and fro during the dance, and the tabataba na kaiya likewise. At the same time the name of the person to be charmed is uttered, and the whole series of evil spirits summoned, upon which the desired method of death is pronounced with the words: u na wirua pit na nga (may you die on the path)! or: u na wirua ra na ta (may you die at sea)! or: u na bura (may you crash down)! and so on.

The number of evil spirits summoned is very great for, according to the native’s concept, there is scarcely any object that is not pervaded by an evil spirit. Evil spirits dwell in the snake (wi), the iguana (palai), the crocodile (pukpuk), the shark (mong), the pig (boroi), the crow (kotkot), the brown hen-harrier (miniqulai), the stingray (wara), the dolphin (tokalama), the wallaby (dek), and in numerous other animals.

In the middle, between the moramora and the winerang, is a whole series of other ingiet that can be learned by the initiated members if they wish. A native who is initiated in all the ingiet and who knows how to administer them very effectively, is called a tena ingiet (tena = one who is skilful). As a result of his thorough knowledge he is able to perform many things that are impossible to the only superficially initiated. Thus, for example, he can transform himself into a wawina tabatabaran (spirit woman); that is, he can take on the form of any woman at will. The tena ingiet is paid a certain amount of tabu to entice a given man, an intended victim of evil, in the form of a particular woman. When this man falls victim to the temptations of the wawina tabatabaran, he dies from a bleeding penis.

The tena ingiet can also cause death or illness in a man by pricking the footsteps of a person with the spine of a stingray, in a certain way. This spell is called aqaqar, or raprapu, and the one performing the spell is also designated as tena aqaqar.

It is understandable that the native, who sees himself surrounded by evil magic at every step, is prudent enough to have counter-magic available. Many marawot and ingiet societies therefore have the aim of teaching such antidote spells and magic incantations. These consist of a certain word or a certain phrase being rapidly repeated, thus listing the evil spirits in order one by one, to persuade them to go away. At the same time burnt lime is held in the palm of the hand and the incantation is murmured over it. Betel is chewed at the same time, and from time to time the chewed-up mass is vigorously spat from the lips over the object or person to break the spell.