IX

Stories and Fables

The treasury of stories and fables among the natives varies greatly in range on the various islands. Fantasy has not developed equally in all places: here, the luxuriant twigs and blossoms flourish; there, they are stunted and barely recognisable.

The most impoverished are probably the Baining. They plant their taro and otherwise care little about the way things are. The Solomon Islanders, too, appear to be far behind the inhabitants of the Gazelle Peninsula in this aspect.

However, on New Ireland stories and fables flourish luxuriantly and, with the exception of the Baining, this is so throughout New Britain. Of course, our knowledge is small; white people have not yet come into closer contact with very many of the tribes, and do not know their language, both of which factors are essential for gathering the storehouse of fables.

I regard any classification of these native tales according to content as premature, because of the paucity of material available, and accordingly, I lay them before the reader in all their bright array.

The natives of the north-eastern Gazelle Peninsula believe that the world and everything in the world were originally created beautiful and good by To Kabanana (To Kabinana). Then there came an evil spirit that spoiled everything that To Kabanana had created, including humans. His name differs in the various districts, the most common being To Karavo or To Korvuvu; however, he is also designated as Puruqo, To Poruqo and To Purukelel.

One day, To Kabanana sent out a boy to fetch a firebrand for the workers. The boy did not want to go, and To Kabanana asked him, ‘Why don’t you want to go?’ However, the boy did not answer.

Then the snake said, ‘Well then, I shall go and fetch the firebrand!’ And the snake hurried away and brought the firebrand to To Kabanana.

He then said to the snake, ‘You, snake, will always live, but you, shore people, will die!’ Then he added, ‘You, snake, eat fruit, birds, wallabies and mice in the forest, and you will live on those (eternally); they (shore people), on the other hand, will become ill and die.’

One day, To Korvuvu wanted to eat a man. He killed him at night, cut him up, and ate him. When the people heard that To Korvuvu had eaten a man, they said to one another, ‘To Korvuvu is destroying the people, he strikes them dead, and eats them.’ But they did not dare to attack him because he was far greater in strength than they. He continued doing evil. One day he was catching lice on a boy’s head; suddenly, he bent towards the boy’s ear, cut it off, and ate it on the spot. The boy asked To Korvuvu, ‘What are you eating?’ To Korvuvu said, ‘A kubika na moramoro’ after which he confessed that he had cut off his ear and eaten it, and, bursting out laughing, he added, ‘It tastes marvellous!’

The boy then ran crying to To Kabanana and complained about To Korvuvu. To Kabanana, however, only said angrily, ‘Why did you go to that savage?’

To Kabanana’s wife gave birth to a son. When he got bigger she sent him to a small island with a sling to kill pigeons. He went immediately, sat in his boat and rowed with his hands since there were yet no paddles. In the evening he paddled back to the mainland. On the way a shark came, struck the canoe, and ate the boy. To Kabanana and his wife wailed and lamented night and day over the death of their son, having looked in vain for him everywhere. However, the shark had eaten only the body of the boy, and one day the uneaten head was washed up by the waves. To Kabanana spotted it, brought it ashore and buried it. The mother stayed constantly by the grave, weeping and wailing. One day she noticed that something was growing up from the grave. When the soil was carefully shovelled aside, they clearly saw the eyes, nose and mouth of the skull which had put out roots. To Kabanana said to his wife, ‘Let us watch, we will see what happens!’ Over time the shoot turned into a tree which bore fruit. One day a ripe fruit fell; somebody opened it and ate it. More fruit continued to fall; all were eaten and found to be good and tasty. The tree that 296grew in such a wondrous way out of the boy’s skull was the coconut palm.

One day To Kabanana, To Korvuvu and a small boy went to the sea with nets to catch turtles. To Kabanana and To Korvuvu held the net while the boy was supposed to drive turtles into it. As they drew the net together in order to see their catch, they spotted a piece of pit (unopened bud of a species of Saccharum) in it. They removed it and said, ‘What a stupid thing!’ The net was lowered into the water again, and the boy made a noise to drive turtles into the net, but again they found the piece of pit in the net. Again they threw it far away. When they had positioned their net a third time and the piece of pit was still the only catch, they marvelled and said to one another, ‘This is a completely mysterious catch!’ This time they did not throw it away but took it home and planted it. Soon the pit grew up into a large bush. One day To Kabanana, To Korvuvu and the small boy were going for a walk. Suddenly they saw a woman emerge from the pit, sweep the yard, make fire and prepare food. The three were very astonished at this, and said to one another, ‘Who is that, who sweeps, fans the fire and cooks?’ When the woman heard the whispering, she disappeared immediately back into the pit. The three then went into the yard and ate the meal prepared by the woman. Days later, they saw the woman again, and when she had swept the yard and done the cooking they rushed her and held her fast. To Korvuvu said, ‘This is my wife!’ To Kabanana said that she was his sister, and the boy called her mother. Finally To Korvuvu took her as his wife; she bore him many children, boys and girls who then populated all the land.

Simolo, a Nakanai woman, was working one day in her garden and while she was pulling out the weeds a man from Ulavun approached her. He stood behind a bush and smoked a suk (tobacco wrapped in a leaf). The Nakanai woman, who did not know about smoking tobacco, marvelled at it, and asked what it was. The stranger smoked on and, astonished, the woman went up to him, saw how the smoke came out of his mouth and asked if he would give her the suk. Her wish was granted, and the woman tried to smoke. When the smoke appeared she was very happy and said to the man, ‘Let us get married.’ Then they both went to Ulavun (the volcano, The Father) and sat up there smoking and stamping, so that the ground shook and the mountain spewed fire. The Nakanai people living at the foot of the mountain saw this and were very surprised. They looked in vain for the missing Simolo. One evening Simolo and her husband came down from the mountain and entered the village. Simolo was smoking, and when the villagers saw this they asked her, ‘Who gave you this wonderful thing?’ and she pointed to the stranger. But the people said to one another, ‘Let us do it too!’ and they ate (smoked) the suk and enjoyed it. The man climbed up the mountain again with Simolo, but sent her back with tobacco seeds so that her people could cultivate the plant. The seeds grew, and since then tobacco has been grown in all gardens. The man, To Ulavun, fetched Simolo again, and led her as his wife to the top of the mountain where they have remained, smoking, ever since.

Simolo, who was a real woman, had a son by the snake To Ulavun. When he had grown, his parents said to him, ‘Leave here and seek another mountain for your home.’ He went away and chose as his dwelling another mountain, to which he gave his name, Bamus (South Son). He remained up there, smoking and spitting out fire and rocks so that villages in the valley were devastated and people were killed. Only a few escaped to Wittau and Tiwongo.

On one occasion all the volcanoes, Langulangu, Kaije, Vunakikiu, Koponawat, Matalaka and Kokomba went to Nakanai to attend the dance of Bamus and Ulavun. When they had reached Sambai they bathed and adorned themselves, then floated further on their rafts. Having arrived at Nakanai they attended the dances. First, they watched Ulavun’s dance and, when it had finished they said that it was no good. Nor did they think that the dance of Bamus was any good. Afterwards, To Ulavun and To Bamus gave the foreign volcanoes gifts of Areca, betel and shell money. They did not favour Vunakikiu, on the pretext that he was a bad man. To Vunakikiu was very angry, and said to the favoured volcanoes, ‘Go home, off you go, I will follow you.’ And so they went away. The angry To Vunakikiu bored his tail into the mountain Likuruanga (North Son) and the mountain swayed and shook, fell into the sea and smoked no more. The Nakanai people then hurried up there, held Vunakikiu fast and gave him gifts of Areca, betel and shell money, whereupon the earthquake stopped and he went home.

In the opinion of the Nakanai people, the inhabitants of Ulavun are ugly and deformed. They talk about them in the following way:

The inhabitants of Ulavun and Imbane one day caught a wengi (a mythical sea monster) and roasted the flesh. A woman ate it first and immediately her mouth convulsed, the lips swelled and the mouth remained open. The nose grew larger, broad and flat. All children born to the woman resembled their mother, and, since all the women had eaten the wengi, all their offspring were deformed. Since that time they have been ashamed, and no longer come down to the shore. 297

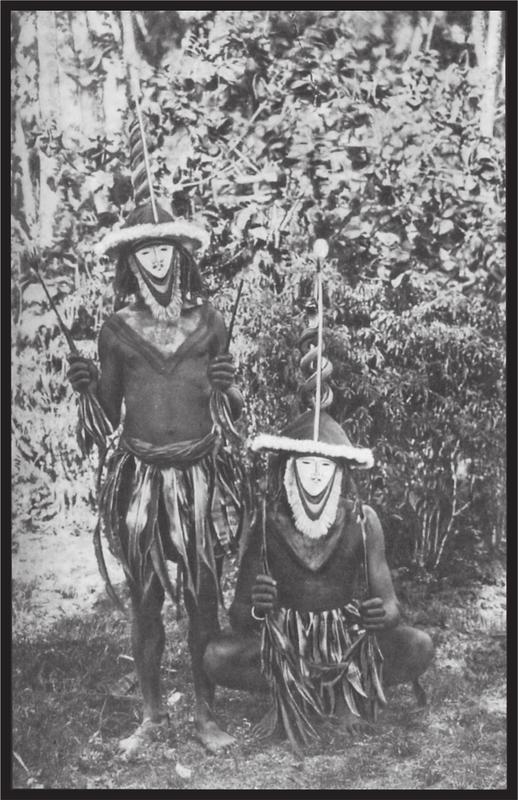

Plate 44 Dancers, representing spirits

One day Tolangabuturu saw a pigeon. He followed it from tree to tree and tried to catch it, but always it evaded his grasp. Finally it flew over the sea and Tolangabuturu got into his canoe and followed it. After a long journey, he reached an island and discovered that it was inhabited only by women. This seemed uncanny to him, and he climbed a tree to hide. But the shadow of the tree fell on a spring, and when one of the women came to it she saw the silhouette of Tolangabuturu and discovered his hiding place. He pleased her at first sight and, to keep him for herself, she collected water in empty containers for the other women, so that they would not have the opportunity of discovering the treasure. When 298all the women went away to amuse themselves on the beach with the turtles, the woman crept to the tree and called to Tolangabuturu to come down. She took him to her hut and concealed him there, but eventually the other women discovered his presence and everybody wanted to have the new arrival. This was an occasion for great quarrelling and strife, for the initial discoverer regarded Tolangabuturu as her exclusive property; but finally they came to an agreement and he became the common property of all the women, who looked after him most solicitously to the end of his days.

One day Tokadol found a boy and a small girl in the forest. They had run away from their mother because she was angry that the children had eaten her mangoes. Tokadol took compassion on the little ones and took them to his hut, but his wife, Limlimanavin, was not in agreement, for the little girl aroused her jealousy; and she threatened to eat the boy. Tokadol, however, prevented this, but while he was away one day the wife carried out her plan and ate the boy. She hid his head in the bush, where it was found by Tokadol. He was very angry, ran home and torched his hut, so that his wife would burn with it. Tokadol had thrown the boy’s head into a waterhole, where the spirit of the burnt woman visited it. Tokadol now felt very lonely and forsaken, and pined for the boy. The spirit of Limlimanavin awakened the head to life, and brought the boy to Tokadol, who was overjoyed, and forgave his wife because he regarded her innocence as proven.

Ja Dapal had an evil, jealous husband from whom she finally ran away to find safety on a rock in the sea. But the tide rose; soon the water reached her waist, then her neck, and gradually rose higher and higher. Her husband stood on the beach and called to her to come back to shore, but, although the water had already risen so high that she had to jump up from the rock from time to time to keep her head above water, she called back that she would come only if he fetched her. Since the husband did not wish to do this, she finally had to die.

To Kabanana is the inventor of the big fish-trap. He also taught To Poruqo how to make it. One day To Kabanana had to go off to a compound, and left To Poruqo behind to continue working on the basket while he was away. After a short time this got boring, and for recreation he began to throw his spear at different objects. In the end he threw it at the fish-trap as well, and when To Kabanana returned he found it partially destroyed. Indeed he scolded To Poruqo but he had to prepare the trap himself.

Then he showed his companion how to use it, and also taught him how the fish should be prepared and baked. Then he went into the forest. To Poruqo prepared the fish he caught, as he had been told, ate some of them and packed the rest into a basket to take to To Kabanana in the forest. On the way, he spotted a beautiful bird, and tried to knock it out of the tree by throwing stones. When there were no more stones available, he threw the baked fish at the bird, but of course in vain. Thus, through his thoughtless activity, he ruined what his companion with thought and care had planned.

To Kabanana and To Poruqo noticed that, in the mornings when they went outside their huts, somebody had already laid prepared food outside. When this continued, To Kabanana lay in hiding and discovered that it was a woman who made them this gift. Each of them wanted to acquire the benefactor, and To Poruqo was loud in his demands; but To Kabanana finally succeeded in persuading him that he alone had a right to the woman, and she became his wife. Over time the couple had many children, and finally To Poruqo married one of the daughters. Based on this, there are always useful and useless men in the world, and both must see how they can get along together.

One day, the wallabies went onto the reef to fish. As the tide rose, most of them went back to shore, but one hopped from stone to stone and jeered at the fish swimming by. It did not notice that the water was rising higher and higher until, finally, surrounded by the sea on all sides, it was marooned on an isolated rock far from shore. Then it began to wail, and implored the fish to carry it to shore, but the fish said, ‘Earlier you ridiculed and insulted us; now see how you can get to land without us.’ Luckily the turtle came by, and was touched by the pleas of the wallaby. The wallaby settled on the turtle’s broad back and entwined its front legs round its neck to get a better grip. The turtle swam to the beach; but on the way the wallaby gnawed at its saviour’s shell, where it covered the neck between head and trunk. When the turtle noticed this, it began in turn to gnaw at the front legs of the wallaby, so that they became shorter and shorter. When they reached the beach the wallaby sprang down from the turtle’s back and called to it, ‘Look at your neck! How ugly and wrinkled it has become!’ The turtle replied, ‘Look at your front legs; how short they have become.’ Since that time the turtle has no shell between head and trunk and draws his head back to protect this region; ever since then the wallabies have had short front legs.

Long ago the kau (Philemon cockerelli Kl.) had the bright plumage of the mallip (Lorius hypoenochrous H. R. Gr., a species of parrot), which had the simple grey plumage of the other. One day the kau went to bathe, and laid his bright garment carefully on the shore. The mallip came along, and laid his grey 299costume down before he stepped in to bathe. He saw the bright plumage and crept towards it to admire the splendid decoration. Unobserved, he adorned his own body with the iridescent feathers, and when he was ready he called to the kau, ‘See how beautiful I am!’ The kau was very angry and called upon him to put the costume back, but the mallip laughed and flew away. Incensed at this, the kau grabbed a lump of earth and threw it after the mallip. The clod hit the mallip on the head, and ever since then he has a grey-black fleck on his beautiful red head. The kau then had to slip into the dull garment of the mallip, and he has not yet succeeded in retrieving his stolen property.

The following legendary tales date from more recent times:

When the volcanic eruption occurred in Blanche Bay in 1878 and the small, flat Vulcan Island was formed, people in the village of Karavia opposite claimed to have seen spirits in human form on the island, going to and fro in the rising steam. After the eruption of the small undersea crater to which the island owes its existence, they disappeared as quickly as they had come. Old people still alive will not let this story die, and are firmly convinced that those who appeared on that occasion were the children of Kaije.

In 1901 the Bremen Lloyd steamer München ran onto a sandbank in the harbour when putting to sea from Matupi, and was refloated only after several hours. It so happened that on that evening there occurred a quite severe earthquake, and the Matupi people declared that the steamer had run up onto the tail of Kaije, who was lying on the sea floor in the form of a crocodile. Angered by this, Kaije had swung his tail to and fro thus causing the earthquake.

The Sulka folk, through their extraordinarily developed fantasy which sees spirits and spirit activities everywhere, understandably have a great number of tales, of which we know only the smallest fraction. For the following, I am grateful to Brother Hermann Müller of the Catholic mission, who has recorded them from the accounts of his Sulka pupils.

Long ago the Sulka did not know about fire. They ate all their meals raw, as nature had presented them. Night, too, was unknown at that time, and crickets, which chirp at night, did not exist; neither did the kau bird, which greets the dawn with his cries and whistles.

One day a man by the name of E Makong (Emkong) was lopping boughs off a tree on the bank of the Makong River. His kienho (an item of jewellery) fell into the water, and he climbed down the tree, laid his stone axe and loincloth on the grass and leapt into the water to retrieve his lost ornament. When he reached the bottom of the river, to his astonishment he found himself in a compound, where many people ran up to see the stranger. A man approached him and asked his name. ‘E Makong is my name,’ he replied, whereupon the questioner answered, ‘Oh, then you are my namesake, for I too am called E Makong.’ Then he led him into his yard and offered him a new loincloth. Greater still was the astonishment of E Makong when he saw fire for the first time, and he was overcome with great fear. Cooked bananas and taro were set before him, but at first he did not want to eat anything. After a long hesitation he finally tasted it; the cooked food pleased him and he ate to his heart’s content.

Gradually evening approached and it began to get dark, and the crickets sang their little song. He was very frightened and believed that he was going to die. But his fear grew extreme when detonations sounded all round him and the people were transformed into snakes which curled up and lay down to sleep. His namesake soothed him and said that he should not be frightened since this was their normal custom. It would soon be day again and they would turn back into humans. As he said this he gave a loud report, turned into a snake and lay down to sleep. E Makong was now alone in the dark among a lot of snakes, and afraid; but finally weariness overcame him and he fell asleep.

When the kau began to pipe and whistle, he awoke and saw that day was gradually breaking. Loud reports began to sound around him and the snakes assumed human form.

Makong, the host, then wrapped the night, fire, several kau birds and crickets into a little pack, which he gave to his guest to take home with him. Then he led him along the way. Makong soon found himself on the surface, and climbed onto the bank. He laid the fire in a field of grass, and, as it began to burn and crackle and the flames flared high in the air, all the people ran up in fear. Makong, whom they believed had drowned, then stepped forward, recounted his experiences and explained the use of fire to his people. He unpacked everything else and let the crickets and kau birds fly away, but, gradually as it became pitch-black night, the fear of the people knew no bounds. However, he pacified them, and over time the people grew accustomed to the new state of affairs.

Earlier the moon shone and burned just like the sun. A small bird (a vit) came, took mud, flew with it to the moon and threw it in its face. Since then the moon has darkened and does not burn; the flecks of mud are still clearly visible.

The vong (cassowary) used to be able to fly, just like the other birds, but he lost this ability in the following way.

One day it rained heavily. The vong sat in a tree 300and let the raindrops run off. Along came the little bird a vit, and spoke to him as follows, ‘Grandfather, raise your wing in the air a little so that I can slip under and protect myself from the rain!’ The good-hearted vong granted the little one’s request straight away and the vit slipped nimbly under the wing. But he was a mischievous rogue and took needle and thread and sewed the upper wing of the vong firmly to its body. When he had finished he spoke again, ‘Grandfather, let me slip under your other wing, since it is dripping through here.’ The vong was quite happy and the vit hid under the other wing, which he fastened with needle and thread just like the other wing.

When the rain had stopped and the sun was shining again, the vit said to the vong, ‘Let’s fly away, for the weather is fine again!’ and he quickly slipped out of his shelter and flew away. When the vong wanted to follow he noticed to his horror what the vit had done; try as he might, he could not spread his wings and fly away. He fell to the ground, and since that time he has had to remain permanently on the ground.

The vong was very angry and called to the vit, ‘Just you wait, I will cast a spell on your droppings and then you will die.’

Now when the vit had to relieve himself he settled in the top of a tree so that his droppings could not fall on the ground to be bewitched by the vong, but would remain in the tree. But the droppings, hanging from a branch, gradually stretched into a long thread and transformed into a creeper, a gilengœi, with beautiful red flowers.

(This fable with slight variations is also known on the Gazelle Peninsula.)

The vukameak is a recluse among the birds, and he sits silently with his bill pinched together, alone in his hole in the rock. One day the other birds decided to do everything they could to make the vukameak laugh. They tried everything possible; the crow striped his whole body with charcoal, the gumbul ate earth, the gau made warts on his bill, but all was in vain, and nothing made the vukameak laugh. Without a change of expression he watched the crazy behaviour with bill tightly closed. Last came the green parrot; he had smeared his entire body with excrement, and presented himself in front of the vukameak. When the latter saw him, he finally had to laugh, opening his beak to do so. At the same moment something fell out, and the parrot was quickly on hand to catch and swallow it. When this had left the parrot through excretion and fell to the ground, a taro sprouted from it. The people found the plant, tended it and raised other taro plants from it. Thus, the taro gradually spread throughout the villages.

In two different neighbouring villages there lived two brothers of the same name. One, Nut vulau (Nut the elder), had two wives and many servants; the other, Nut sie (Nut the younger), was unmarried. He lived with his grandmother in a compound and had only ten servants.

One morning Nut sie got up, took his fishing spear, and went fishing. When he had caught three vulaupun he made his way home with them. On the way, his brother’s two wives met him, and when they saw the handsome young man they found him pleasing. They said to him, ‘Your brother’s taro are drying, he has sent us to catch crabs.’ He handed them his fish and said, ‘Take these fish and prepare them for your husband.’ They took the fish and went back home with them, but gave their husband only the crabs that they had caught, and ate the fish themselves.

Another day when Nut vulau was working with his people he sent his wives again to the sea to fetch salt water and catch crabs. Nut sie, who had gone fishing again, met them once more on the way home and again the women lusted after the handsome youth. He asked them, ‘Did you give my brother the fish?’ They answered in the affirmative, whereupon he again gave them fish for their husband. They met several times, and each time repeated the same routine as at their first meeting.

One day Nut vulau was again hard at work with his servants, and the women were sent to catch crabs as usual. Nut sie, who had also gone fishing, met the women again and, since they were now quite accustomed to him, they pestered him at length until he consented to have sexual relations with them. He painted the genitalia of his brother’s two wives with a coloured design. One day the elder brother noticed the drawing when one of the wives sprang over a fence, and his suspicion was immediately aroused. But to be more certain he set to and had a boat made, and, when it was ready, he ordered his wives and several of his people to go to sea in it. He remained on shore; as the women climbed into the boat he saw the designs clearly. Under the pretext that a storm was coming he called the boat crew back and made them land.

He then had whitish coconuts (a sil) brought down and new unpainted loincloths produced. He summoned all the people and gave them each a nut and a cloth so that they could make a design on both and then give them back to him. Nut sie received a nut and a garment also, but his designs were poor. When all the drawings had been returned Nut vulau inspected them, but none matched the pattern on the women. However, he had his suspicions about his brother, and had him draw another design. This time the pattern precisely matched those on the women, and now Nut vulau knew the perpetrator. Immediately he prepared for war, and his servants had to make weapons and shields. Nut sie and his servants also 301prepared for war. They made fine shields, painted them with bright colours and hemmed them round the edges; they also made handgrips on the reverse side. However, Nut vulau’s servants were very unskilled; their shields were ugly, and lacked hand-grips, so that they had to grasp them by the edges and hold them.

The grandmother, the old Tamus, wept and said, ‘Nut vulau will come with his servants and attack us!’ Nut sie replied, ‘Let them come, we will acquit ourselves well.’ Then the old woman made a spell from lime, which she smeared on the warriors. Nut sie spoke to his servants, ‘We will remain in our two houses and await the enemy; nobody will go outside. When the enemy arrives and I go outside, you will all follow me but we will stay close together, nobody will go off to the flanks.’

When the enemy arrived and drew nearer, Nut sie stepped out of the house and danced in front of the entrance swinging his shield. When Nut vulau saw his brother’s shield he was astonished at its beauty and said angrily to his servants, ‘You don’t understand anything; look at my brother’s shield, how beautiful it is.’ Meanwhile the servants of Nut sie all came out into the open, threw lime at the enemy and the battle began. As a result of the advice given, it ended with the total defeat of the attackers; all were killed, only Nut vulau survived. The victors looked at the shields of the slain and laughed; but Nut sie called to Nut vulau, ‘Go and get new warriors, we will do the same to them as we did to these.’

Nut vulau then assembled new warriors and attacked his brother again, but it turned out the same as the first attack, his people were killed and he alone survived.

Early next morning, at the cry of the kau, Nut sie got up and climbed a vanga tree. Calling in all directions he summoned the land and then went to inspect it. On returning home he said to his grandmother and his servants, ‘We will leave here and go to a new homeland.’ They made ready for the journey, took taro, bananas and other fruit, tied up their pigs and laid everything beneath the vanga tree. The following morning they set out, and soon came to a beautiful land where they settled.

Later, Nut sie cherished the hope of getting married, and he decided to carry off one of his brother’s wives. For this purpose he built a great bird, ngaininglaut, out of wood; it was hollow inside. When the bird was ready he slipped inside and flew away. The bird’s wingbeat was like the rushing of the wind and trees were uprooted. He climbed high in the air and from above he saw his brother’s gardens. Then he flew back home, went to his grandmother and said, ‘I looked down on my brother’s gardens, and I shall fly there to fetch one of his wives for myself.’ The grandmother gave good advice, saying, ‘Be careful! Do not fly close to the ground, and do not alight on low trees lest your brother kill you.’ Nut sie got into his bird and flew away.

Nut vulau was working with his servants when the bird came flying along. There was a roaring and blustering like a heavy gale and the banana plants were torn out of the ground and trees crashed down, so that the servants threw themselves on the ground in terror. Nut vulau, however, recognised his brother, and said, ‘I know you! I saw you in a dream! You have come to steal my wife.’ Nut sie flew to the wife, took her by the hand and flew away with her. She was very frightened but he calmed her and took her to his grandmother. At first the grandmother was not pleased, but she settled down over time. The woman bore Nut sie many children, and the tribe soon grew very large.

The grandmother, Tamus, created the sea and covered it with a stone to keep it hidden. Her two grandchildren soon noticed that their food tasted better because she had cooked it with salt water. One day they spied on the old lady as she went to the sea to moisten their food with sea water. When she had done this, to her horror she spotted her grandchildren and shouted to them, ‘Now the sea will destroy us all!’ Then the sea flowed out in all directions, forming islands and bays and straits, and so it stayed to this day.

The following story about obtaining salt, half fable, half true, probably belongs here.

On the shore one of the Tumuip tribe had a house, which was split in two by a dividing wall. Only boys and youths could enter the front part of the hut; not married people. Only the owner of the house could enter the rear part of the house. Here a large fire burned under a framework on which lay a big piece of tree bark. The women drew sea water from the ocean and poured it into bamboo tubes placed at the hut entrance. The owner of the house poured the sea water onto the bark above the fire; meanwhile he chewed ginger and spat this onto it. The fire was maintained until the tree bark was crusted with salt. Then the people came to buy the salt, ralminmin. Salt is regarded as a great delicacy; it is also given to the pigs because it makes them big and fat. However, people avoid touching the ralminmin with their fingers, because they believe that skin diseases can develop from it.

In a certain place lived two mokpelpel, Kanmameing and his wife Lelmul, who ate everybody. The surviving inhabitants therefore decided to move away, and got into their boats to seek a new home. At this place there was a woman called Tamus, who was in an advanced stage of pregnancy, and the voyagers did not want to take her with them. But she was 302resolutely determined to go, and clung to a boat with her hands at the departure. They pushed her back and yelled, ‘The time of your confinement is near and you would only be a burden to us on the journey.’ Tamus went sadly back to the shore and built a dwelling out of kejang (a tall type of grass). Here she gave birth to a son, and when he had grown somewhat she left him in the house while she worked nearby. However, she told him never to talk or laugh lest Kanmameing and Lelmul hear him and come to eat him up.

One day as she went to work, she gave her son a pûpál (a species of Dracaena) for him to play with in her absence. The boy looked at it and said to himself, ‘What shall I make out of this plant, a brother or a cousin? I know, I shall make a cousin!’ During these words he had held the plant behind him, and he suddenly felt as if somebody had scratched his hands. He looked round in amazement and saw a handsome boy standing behind him. At first the latter was shy and said nothing, but soon a casual conversation was in full swing. The mother heard it and, believing that her son was talking loudly to himself, she called to him, ‘Be quiet, or the two mokpelpel will come and devour us.’ The boy named his cousin Pupal, because he had been created from a pûpál; however, he did not share the event with his mother immediately, and decided to keep Pupal hidden from her for a while. He therefore went to her and said, ‘Mother, I want to erect a dividing wall in our hut, and then you can live in one part while I stay in the other.’ The mother agreed with this, and the boy divided the hut with a wall. Then Tamus’ son went to his mother again and said, ‘Mother I am hungry; bring me sugar cane and bananas!’ The mother brought them. Now, when the two boys were sucking out the sugar cane, the mother heard all the noisy eating and called, ‘My son, is anybody with you? I can hear a lot of noisy eating.’ – ‘I am alone, mother, and I alone am eating so noisily,’ answered her son. Then, when the pair drank water, the mother heard a lot of swallowing. However, in answer to her questioning, the boy protested once more that he was completely alone.

This went on for a while, and the mother had no idea of the presence of Pupal. At the son’s request, Tamus allowed him to lay out his own garden, and then both boys were able to work together and talk to their hearts’ content, joking and laughing without the mother hearing them. One day when the mother unexpectedly brought the son his food, she saw to her great astonishment the strange, handsome boy and, full of amazement, she said, ‘Who is this, and where does he come from?’ The son replied, ‘Mother, do you remember the pûpál that you gave me as a toy one day? This handsome boy came out of it!’ Now the mother knew the secret and from then on all the onerous barriers in their relationships could be brought down. However, she was concerned that the two mokpelpel could easily discover them, and warned the two boys, ‘Children, do not talk so loudly, otherwise the mokpelpel will find us and devour us.’ But the children answered, ‘Oh, we are not frightened! Let them come, we will destroy them.’ Tamus was astonished at this self-confidence in the two boys, and worried about it a lot when she was alone.

But the pair were very serious about killing Kanmameing and Lelmul. However, they kept their plans secret at the start, but made all the necessary preparations.

First they build a dwelling, a rik, for Tamus, and a men’s house, a ngaulu, for their own use. Then they made shields and spears, and practised throwing the spears. Their initial shields, however, were made from soft wood, and so they made fine new shields from the wood of the guip tree, and hung them up in the house. Next, they felled msa trees, and used the trunks to erect a barricade in front of the entrance to the compound. At this point they invoked very hot weather, so that the bark of the basika tree became very hard; they next invoked heavy rain so that the bark of the msa tree became very slippery. The mother, who did not know what all this was for, looked on in amazement, and finally asked what they actually intended to do. ‘We want to kill the two mokpelpel!’ answered Pupal. Tamus warned, ‘Children, do not annoy those two.’ But Pupal continued, ‘Just let them come, we will be ready for them.’

When all their preparations were complete, the two boys climbed into a swing that they had made in a tree on a slope not far from their compound. They swung here and called with loud voices, ‘Oh Kanmameing and Lelmul! Oh where are you hiding? Come and eat us!’ But in her hut Tamus shook with fear. Lelmul, who was outside while her husband was in the house sharpening his teeth, was first to hear the youths shouting. She went to her husband and said, ‘Can’t you hear? We are being called. Who can it be? Haven’t we eaten all the people around here?’ Kanmameing then took both his fangs, put them in his mouth, and set off in the direction from which the call came. Lelmul followed him. With his two fangs, he cut down the bushes on both sides, and made a wide path.

Meanwhile Pupal said to his companion, ‘Stay in the swing and call again!’ Meanwhile he climbed down, took several lances and lay in ambush. When the giants were close he called, ‘Come down quickly! They are here. You take the woman, I will attack the man.’ When the mokpelpel came, and tried to climb the barricade, they slid down and fell on the ground; a big piece of wood fell down on Kanmameing. Pupal then stepped forward, and Kanmameing sprang up and tried to catch him with his fangs to devour him. Pupal was agile, however, 303and slipped between the giant’s legs. Meanwhile Tamus’s son had thrown his lance at Lelmul and pierced her right through. While she was still struggling on the ground he wanted to finish her off, but Pupal called to him, ‘Leave her and come and help me!’ He hurried up quickly, and they both threw their well-aimed spears at Kanmameing, but only after he had been pierced many times did he fall to the ground. The two lying on the ground, were killed stone dead with much derision and many insults. Then Tamus was summoned, and the youths said, ‘Look, they are both dead.’ With great jubilation, a huge fire was made, and the dismembered corpses of the mokpelpel were burnt.

They cut off Lelmul’s breasts, laid them in a coconut shell which they floated in the sea, saying, ‘Go to the people who went away from here, and when they ask, “Have the mokpelpel slain Tamus, and are these her breasts?” continue floating on the water. But if they ask, “Did Tamus give birth to a son, and did he kill the mokpelpel, and are these the breasts of Lelmul?” sink immediately.’

The coconut shell floated away and came to the people who had left. They looked at the shell with the breasts and asked, ‘Has Tamus been killed by the mokpelpel and are these her breasts?’ The coconut shell made a sign of denial and remained afloat on the water. Then the people asked, ‘Did Tamus give birth to a son who killed the mokpelpel, and has he sent us the breasts of Lelmul?’ Immediately the shell sank, and the people then cried joyfully, ‘Now the two giants are dead! Let us go back to our old home!’ They immediately prepared for the voyage and set off in their canoes. When they reached their homeland, the two boys did not want to let them land. They threw stones at them and Tamus’s son called out, ‘You did not want to take my mother with you when her baby was due; when you fled from here you pushed her back. Now we do not accept you; go back where you came from.’ However, the people would not be intimidated, but landed and again lived happily in their homeland.

Two brothers lived together in a village. The younger was very clever, and could turn himself into a cockatoo by using a magic spell that he knew; the elder, on the other hand, was a braggart, did not understand sorcery, and knew no spells. Not far from this village, an old married mokpelpel couple had settled. Their hut stood beneath a coconut palm, and their property consisted of a large pig.

One day Blakas (as he was called, because of his skill,) turned himself into a cockatoo, and in his favourite form cried, ‘kah, kah, kah’, and flew into the coconut palm beneath which stood the mokpelpel’s hut. He bit off a nut and let it fall onto the hut; it fell through the roof into the hut. The elderly woman said to her husband, who could not see well because of his age, ‘A cockatoo is perched in the coconut palm; go outside and chase him away.’ The old man went outside, struck the trunk of the palm, clapped his hands, then came back inside, saying, ‘He has flown away.’ Then the cockatoo again bit off a nut, and it fell through the roof and into the hut. The elderly woman became angry, and again sent her husband out to chase away the cockatoo. The old man did exactly the same as before, then came back inside and said, ‘He has definitely gone away this time!’

But it did not last long, and again a coconut flew into the hut. The old woman sprang up enraged, scolded her husband and yelled, ‘You old fool, you can’t see anything any more; the cockatoo is indeed still there.’ With these words she rushed outside, but was very surprised when she looked up and spotted a man at the top of the palm tree, for Blakas had quickly assumed his human form. Amazed, the elderly woman called out, ‘That is no cockatoo; it is a man!’ and turning to her husband she ordered him, ‘Climb up and bring him down so that we can eat him.’ The old man then climbed up, but when he had reached Blakas and was in the process of grabbing him, the latter stepped on his head and knocked him down, calling to the woman, ‘There is one that you can eat.’ In her anger the woman immediately seized hold of the one that had fallen and devoured him, without first checking who it was. Then Blakas called to her, ‘You have eaten your own husband.’ Then he changed into a cockatoo again, cried, ‘kah, kah, kah,’ and flew away back to his garden, taking a number of coconuts with him. In the garden he assumed human form, scraped the coconuts into taro leaves and took them home. When he got there he began to eat, and his brother asked him what he had there. He gave some to his brother, who ate it with great pleasure, and asked where it came from. Blakas then told of his adventure and added, ‘Had it been you, they would have devoured you!’ The brother answered, ‘Who would be afraid of your mokpelpel?’ – ‘Good,’ said the other, ‘Go and try it.’ – ‘I will go first thing in the morning,’ replied the elder brother.

The following morning he set out along the path to the mokpelpel’s hut, crept to the coconut palm and climbed up it without being noticed. His brother, Blakas, who loved him very much and knew well that great danger threatened him, went meanwhile into the forest, and with his magic drum called the dogs, wild pigs, wallabies, biting ants and other animals together, and led them all in the direction of the mokpelpel’s hut where he hid with them. Meanwhile, the one up the tree had plucked off a coconut and thrown it down. The mokpelpel looked up, spotted him and called out, ‘Are you still there? I thought that you had gone. Just you wait, I will get you down and eat you.’ She thought that it was the same visitor as the previous day. The one up the tree answered, full of confidence, 304‘Climb up to me; I will knock you down.’ The old one climbed up, grasped his foot and pulled him down; his struggles were of no use, he could not free himself. Once down on the ground, a life and death struggle began. The mokpelpel fastened her fangs into his body, and threatened to devour him. Blakas, who was watching the struggle, realised that his brother was on the point of being overcome, and he began to beat his drum. The mokpelpel started up, but already all the beasts who had been summoned had fallen upon her, and she had to get away as quickly as possible.

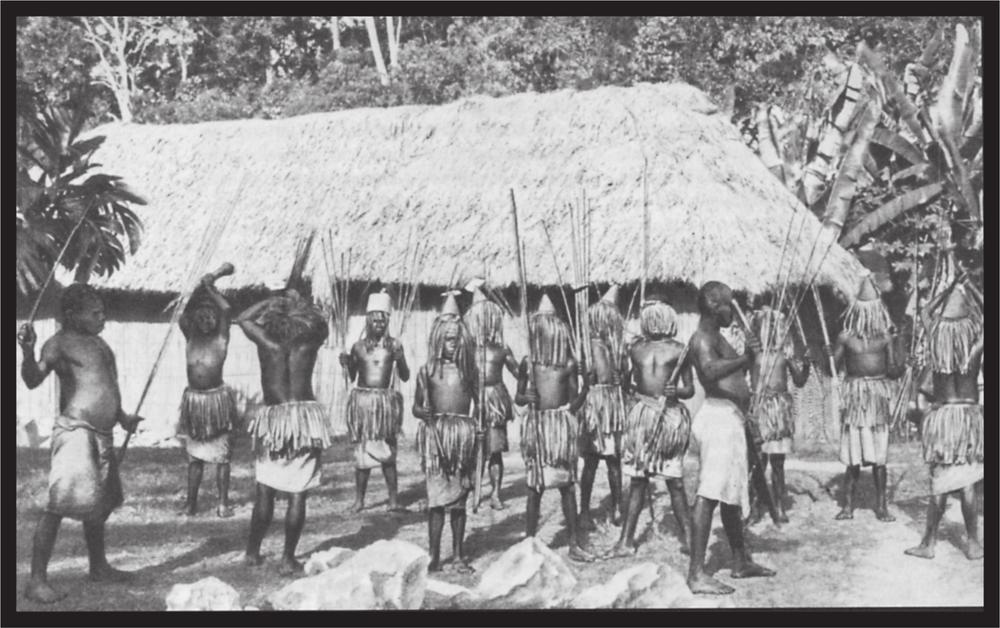

Plate 45 The mabucha dance of the Baining

‘You see,’ said Blakas to his brother, who was shaking all over, ‘if I had not come quickly, the mokpelpel would have eaten you.’ – ‘Oh,’ said the latter, ‘I would have finished her off. Didn’t you see what she did, out of fear?’ He meant, what he himself had done. But Blakas had seen everything, and did not believe a word. Then they tied the mokpelpel’s pig, took anything else of use from the hut and went home with their booty.

There was once a boy who suffered greatly; his name was Loel. His mother had died; he lived in the compound of his father, who had remarried. His father and stepmother were very miserly, and gave the poor boy nothing to eat; he had to look for his own food. Often when they were both eating, he would ask if they would give him something, but the request was always in vain. If he asked his father for something, he would refer him to his stepmother. If he asked her, she would refer him to his father, and so it went on every day, even though he begged and pleaded so pathetically.

One day Loel had set bird lime and caught several birds, which he prepared. When they were cooked, he began to eat them. Earlier, his parents had given the usual mealtime reply. As he was eating, they saw that it was something tasty and they went up to him. His father said, ‘Son I have worried myself to death about feeding you; give me a piece of your birds.’ Loel replied, ‘Get something from your wife!’ Then the stepmother came with the same request, but she was given the answer, ‘Get something from your husband!’

Then the parents became very angry, and went out to summon evil spirits to eat their son. Meanwhile Loel sat on his bench, expecting no harm. A bug crawled up and bit him. He turned round angrily, to see what had bitten him. How surprised he was to see a bug, which began to speak, ‘Why are you so angry, and why do you shower abuse on me? Listen to what I have to say to you. Your father and stepmother have gone to fetch evil spirits to eat you.’ Then the bug crawled away. Loel, however, was not very frightened, because he could turn into a grasshopper (loel = grasshopper). He quickly did so, chewed a hole in a piece of wood, and crawled inside.

Soon he heard his parents coming with the evil spirits, and, when they could not find him, they called out, ‘Loel, where are you?’ – ‘Here I am!’ he called from his hiding place. They searched the entire house but found nothing; during the search 305they had thrown out the piece of wood in which Loel was hiding. Again and again they called out, ‘Loel, where are you?’ and again and again came the answer, ‘Here I am!’ In time this became so boring for the evil spirits that they ate the father and the evil stepmother.

The following story has a lot in common with a previous one that talks about the origin of fire. It goes as follows: Mugowan was paddling in a canoe on the Mewlu with several of his friends. On the way he skewered a fish with his fish spear, but the fish swam away with the spear and disappeared in the flood. Then Mugowan sprang out of the canoe and dived under the water to retrieve his spear. When he reached the bottom he suddenly found himself among many spirits who were sweeping the bottom, and, when they saw him, they rushed up to see the stranger whom nobody knew, and they asked one another, ‘Who might this be?’ Among them, Mugowan recognised his uncle, Koutol, who, when he spotted his nephew, recognised him; but they both kept quiet until Koutol finally said, ‘Don’t you know him? This is Mugowan.’ The spirits asked him, ‘Are you dead, then?’ But Mugowan remained silent. Finally they said, ‘You are a living person!’ And Koutol added, ‘Go! When you are dead you will live here among us.’ Then the spirits guided him on the way back, and he climbed out. Meanwhile his friends had been looking for him. When they saw him climbing out they spoke joyfully to him, but he could not speak because he had been speaking with spirits. They laid him in the canoe, took him to the mouth of the river, chopped wood and made a big fire. They laid him beside it until he became warm. Then they said to one another, ‘If we stay here the Saktai will attack us and kill Mugowan; let us go to the island where we are safer.’ They did this, and when they arrived they prepared food, but Mugowan did not want to eat anything. The following morning they paddled back home in their canoe and called Mugowan’s wives and children. They were inconsolable and spoke reproachfully, ‘Why did you dive in after your spear!’ Mugowan began to speak again and said, ‘When we die, we go to the bottom of the Mewlu and live there. Whatever we say up above they can hear down below, while up above we can hear nothing of what they say down below. It is a splendid place, with many pigs, breadfruit, coconuts and betel nuts, bananas and all good things.’

From the Admiralty Islands we know, from the mouth of the native, Po Minis, a great number of stories which I will set down here.

The name, Tjaw’mu (not Tshebamu) is the designation for the high, universally visible mountain range occupying part of the main island north of the island of Ndruval. It is said of Tjaw’mu that, ages and ages ago, it was in the process of growing higher. Getting bigger and bigger, it would finally have grown into the sky, had a snake, which was lying on its crest not prevented it. The snake had noticed this secret growth and forbidden the mountain from doing it. Now that the mountain realised that his secret, which had remained undetected under cover of continuous night, was discovered, it suddenly became daylight and the mountain grew no further. Then the mountain spoke to the snake, ‘I wanted to climb into the sky, but you forbade me. Your language will now become different, and mine will become different, and our descendants will all speak different languages.’

They tell the following story about Mount P’unda in the Usiai region, not far from Tjaw’mu mountain: In early times two giants, the sons of Nimeï and Niwong, the progenitors of the islanders, wanted this mountain to tower up to the sky. They dragged huge boulders up to the top, and piled them one on another. However, a snake lived in the caves and crevices on the mountain. It was unnoticed by the giants, but the snake had noticed their intention, and decided to foil them. It slithered out of its hiding place, and ordered one of the giants from henceforth to work for it, but it allowed the other one to haul stones as before. However, he was annoyed that his friend had been taken away, and the following night he loaded himself up with a mighty boulder and went away with it. By daybreak he had reached the Papitálai region and decided to erect the boulder as a boundary marker. With great force he threw the boulder on the ground and called out, ‘Sea, divide the land! One part for those two (the snake and the other giant); one part for me!’ Immediately the sea rushed in from north and south, meeting at the foot of the boulder, which can still be seen today, in the region of Papitálai, and is called Tjaretánkor (= land cut).

The giant who had remained with the snake was frightened, and said to it, ‘Why have you banished my friend? You are a snake, not a man; you are not a companion of equal birth.’ The snake felt put down by these words, and wanted to demonstrate its superiority to the giant. It said, ‘Go, fetch your meal and cook it; I want to watch.’ The giant went away, took his net and began to catch fish, which he took back to the snake. Then the snake said, ‘Prepare your fish; I want to see how you start.’ The giant took a fish, laid it in the sun to let it dry, and then ate it half-raw. The snake laughed at this and said, ‘You are truly an evil spirit; you would even eat me.’ The giant became angry and replied, ‘My father is no evil spirit, I am a human child!’ But the snake replied in a tone inspiring trust, ‘Crawl into my stomach!’ And it opened its mouth wide. The giant summoned up his courage and crawled inside. 306He found firewood within, and pieces of wood for rubbing together. He saw taro, sugar cane and many good things, causing his heart to leap for joy. He dragged a little of everything into the daylight, rubbed the sticks to make fire, on which he roasted the taro, and sucked the juice of the sugar cane while he waited for the taro to cook. When the meal was ready, the giant and the snake tasted it, and the snake said, ‘Whose meal is better, yours or mine?’ And the giant had to admit that the snake’s meal was better.

Since the snake guarded the compound exclusively, all the work fell on the man, who had soon had enough, and reviled the snake. When the snake heard this, it asked, ‘Why are you insulting me? Had I not been here you would already have been dead. Through the good food that I have provided for you, you have grown strong. See, I will go away and you will remain on our land.’ Then the snake wriggled down to the shore and swam through the sea to a distant land.

The last part of the previous tale describes the appearance of produce and fire, and how the latter is used. The land and its inhabitants originate from Nimeï (husband) and Niwong (wife). They both came originally in a canoe from far across the sea. According to another, less widespread, tale the islanders trace their form to two parrots, Asa and Alu. They sat side by side in a tree, and it irked them to be so alone. They decided to make a man, and Asa sewed a human figure together out of leaves. When it was completed, he let it fall onto the ground, and immediately the figure changed into a living man. Asa told him to go inland, build a house, and create a woman out of leaves, the same way that he had done the man. He would then have many children with her.

The great spirit above the clouds was originally completely alone. Then he noticed on earth forty men from Laues, who were scuffling together and hurling insults back and forth. He plaited a large disc from rattan with a rope attached, and lowered the disc to the ground. During the night he climbed down the rope, laid the sleeping men on the disc, and climbed back up. He used the rope to pull up the disc and the sleeping men. He laid them on their beds and hid the disc in the top of a tree. Then he closed up his house, and went into the forest to prepare sago for the men. When he had prepared a sufficient quantity, he hid it in the forest and went back home. When he got there, he spoke to the forty men but they were very frightened. He tried to calm them down, and then went back into the forest. Meanwhile the group became hungry and sent one of their number out to get food. When he reached the forest he saw the prepared sago hanging from the trees, and hurried back. However, he said to his companions, ‘My brothers! This evil spirit is going to devour us; in the forest he is chopping up garnishes that he will eat as well as us.’ They were very frightened and wailed in grief. Then a dog said to them, ‘Why are you weeping?’ They replied, ‘We are frightened because your master is preparing side dishes in the forest and is going to eat us up.’ Then the dog took pity on them and said, ‘Look, there is the disc that you were pulled up in, and there is the door.’ The men pulled the disc out of the top of the tree, lowered it on the rope and slid one behind the other down to earth. Thirty-nine escaped, only the fortieth remained behind and said, ‘When you arrive, you must come to an agreement between our two groups, for we will certainly begin a fight among ourselves.’

When the spirit returned and found only one man, Po Tjutju, he asked, ‘Where are our people?’ Po Tjutju replied, ‘They have gone into the forest.’ However, the spirit realised what had happened, and said, ‘Do not lie to me!’ Then he grabbed a stick and began to thrash Po Tjutju, who was sitting on a drum. Po Tjutju sprang onto a bamboo bed but there too the blows rained on his back. He sprang onto the fireplace, vainly seeking refuge, and finally he made a leap through the open door, constantly pursued by the angry spirit who thrashed away at him without stopping. Then Po Tjutju made a leap into the air where the wind caught him and carried him gently to the ground like a leaf. When his friends saw him coming, they ran to meet him. He said, ‘Brothers! The dog is kind, he has saved us. You had little to put up with, while I have endured a hard struggle. I sat on the drum and he beat me; the drum boomed. I leapt on to the bamboo bed and he beat me so that it rattled. He beat me at the fireplace, and it blazed; he beat me in the open doorway and shining light arose.’

The spirit was very angry, and plaited a new disc to let down to earth. Then the moon stood in front of the doorway and the shadow of the disc left an imprint on the moon’s shining disc.

Another story about the origin of the spots on the moon runs as follows: Two women were busy laying out a garden plot. When night fell they rested from their work, and roasted taro tubers on the embers. When they wanted to scrape the tubers, they found that they had forgotten to bring the shell fragments that they used for the purpose. Right at this moment the moon rose; they grabbed it and used it to scrape their roasted taro. However, after the work was done the moon followed its usual path. The following evening the two women did exactly the same as the previous evening, but this time the moon played a mean trick on them, and the women were very angry. As it went away they called out, ‘You are a miserable devil; your face is blackened. You have served as a shell scraper, the black from the charred taro is sticking to your 307face. You will never be able to wash away the stain of disgrace.’ Since then the moon has borne the indelible black spots on his disc.

Once a boy fashioned a female figure out of sand on the beach. A spirit entered the sand figure and it stood up. Whenever the boy came to the beach it lay down, but when he went home it stood up. Finally the boy was enticed to have sexual relations with the figure, and the spirit twisted his neck until he died.

On the island of Patuam, one of the Horne Islands, the sand figure is visible to this day.

An evil spirit entered a banana. Po Ueïe ate the banana and the spirit killed him. His arms and legs were convulsively pulled together; his liver and intestines hung from his belly.

Two women, one of whom was pregnant, went to catch crabs. When the hunt was over, they returned home, and on the way the pregnant one gave birth. When the evil spirit heard the baby crying, he went to the women and said, ‘Come with me to my cave.’ When they reached it, the spirit killed a pig and roasted taro tubers. When these were ready he ate them all up, but threw the entrails and taro remains to the women. They felt that they had been scorned by their host and said, ‘You are a scoundrel, to offer us such food.’ To which he replied, ‘I have already eaten pig and taro, it is your turn now!’ and he ate them up.

Once a person took a pig’s trotter, hid it in his carry basket and took it into the forest, where nobody lived and where there were no compounds. He threw the trotter on the ground and immediately a pig stood on the spot. He said to it, ‘Multiply!’ and immediately a second pig appeared. He continued the spell, and in the end he had a large number of pigs.

An evil spirit named Po Pékan lived in his compound called Káli. He had four eyes and ate all humans without exception. Two boys went along a winding path and got lost; finally they came to Po Pékan’s compound and stood half-hidden in a corner. Po Pékan was busy building a canoe. Two of his eyes were directed towards his work; the other two roved unceasingly in all directions. He noticed the two boys, laughed with joy at seeing them, and called, ‘Come out, do not be afraid. Sit down and be my guests.’ He set food before them, then suddenly fell on them, pressed their eyes out, killing them, and then ate them. When it was over he beat the death drum and the neighbours said, ‘The evil spirit of Káli has eaten a man again.’

An evil spirit from Péhëu lay hidden. Two men were returning at night from fishing. One lay down to sleep, the other carried the gear ashore and then wanted to relaunch the canoe. However, he pushed against one end in vain, for the evil spirit held fast to the other end. He renewed his effort fruitlessly, for the invisible evil spirit always foiled his attempts. The man flew into a great rage over this, seized an axe and destroyed the canoe. Then, when he wanted to go into his house the evil spirit attacked him. He cried loudly for help, but the spirit held his mouth closed and said, ‘Eat my h…!’ [Probably hoden: balls (Translator)]. The man answered, ‘Who would want to eat your h…? Your h… are stale.’ Then the spirit said again, ‘Eat my h… as a man eats a fish,’ but the man still refused. Then the spirit said, ‘If you won’t do as I tell you, I will eat you up. Come, follow me to my compound.’ The spirit lay down to sleep and commanded, ‘Look for lice!’ When he had fallen fast asleep the man bound him fast to the bed frame by the strands of his hair, and escaped, climbing Mount Ndr’tjun and singing, ‘The evil spirit from Péhëu wanted to eat a man. Where is the man that he wanted to eat? The spirit is bound fast by his hair!’

When the spirit awoke and tried to stand up, he had to drag his bed frame behind him, and since it was heavy he flew into a rage and cried, ‘I am a fool, blinded by stupidity; why did I not eat the man straight away. Oh, his tongue, what a morsel, my mouth waters at the thought!’ And, beside himself with rage, he crushed his h… and died.

An evil spirit from Ndritápat went to Loniu. Two women were night-fishing by torchlight and discovered the spirit in the form of a child, on the shore. Full of compassion, they took him to their huts, set food before him and killed a pig. They gave the entrails to the child and said, ‘Take them to the sea, slit them open and wash them.’ The child went off, assumed his real form on the beach, washed the entrails and ate them. Then he cut off a finger and returned to the huts in the child’s form. When he got there he said, ‘Mother, the fish stole the entrails from me and bit off one of my fingers.’ The two women answered, ‘Never mind, there is enough pork left for you.’ They set it in front of him, and while they were watching he ate slowly, like a normal man, but when their eyes were elsewhere he greedily swallowed large chunks. When a piece of pork fell on the ground, they sent the child out to wash the sand off in the sea. When he had gone the women said, ‘One of us should follow, to see what the child does.’ One of the women did so, and when she reached the beach unnoticed, she saw from her hiding place that the child had turned into a horrible devil whose hair hung down in long strands. Terrified, she hurried back to her friend and called, ‘Let’s flee, otherwise the evil spirit will eat us up. We thought that he was human, and raised him, but he is an evil spirit.’ They hurriedly ran 308away, and when the evil spirit returned, he looked around for them in vain. He grew very angry, slit his belly in rage, and died.

Ten fruit were in their husks, but when it grew dark they fell from their husks onto the ground, took on human form, bathed in the sea, sang and enjoyed themselves. A man came along, saw the swimming forms, whose bodies were as pale as albinos, and beckoned the young women. As they approached, they pleased him greatly, and he said to them that they should all be his wives and go back to his hut with him. Nine of the young women agreed, but the tenth refused, and when the man wanted to force her, she cried, ‘I am the wife of no man; I am a fruit!’ However, the man laughed and said, ‘Oh, you are not telling the truth. Follow me!’ But the young woman said, ‘Look, I will climb up the tree!’ and she did so. When she got up there, she slipped into her husk and turned back into a fruit.

Previously, the men of Háüm had breasts while the women had beards. One day they organised a race; the women came first, the men last. Then the spirit who ruled Háüm said, ‘This is not right. From now on the men will have beards and the women breasts.’ Had he not brought about this change, it is evident that up to the present day women would have given birth to children but the men would have raised them. However, everything turned out for the best.

An old woman was already very old and wrinkled. Once both of her sons went fishing, while she went to bathe. While bathing she stripped off her skin and appeared as a young, smooth-skinned woman. She went home in this form, and soon her sons returned. They were very astonished, and one said, ‘Is this our mother?’ However, the other said, ‘Good, she will be your mother, and my wife.’ Their mother overheard this and said, ‘What did you say?’ and they replied, ‘Nothing! We said that you are our mother.’ But she answered, ‘Do not tell lies! One of you said that I was his mother, while the other said that I was his wife. Had it turned out the way I wanted, we would have grown up and become old and grey, then we would have stripped off our skins and become young men and women again. After your comment, we will grow old and grey, but then we will die.’ She took her skin, put it on again, and became once more the wrinkled old woman. From then on humans have grown old and died. Had the two sons spoken otherwise, humans would have become rejuvenated and lived forever.

The spirit entered a large fish, which stirred up the sea so that a great flood poured over the island of Lóniu. All the Lóniu people drowned in the flood, as punishment for their illicit sexual activity. In former times there was no fire on earth. A woman sent out the sea eagle and the starling, ordering them to bring fire down from heaven to the earth. They both flew into the sky and the sea eagle brought the fire down to earth. Halfway, however, he became tired and handed the fire over to the starling. The starling put it across the back of his neck, but the wind blew and fanned the fire so that the starling was scorched, and turned into a small black bird. The sea eagle, however, remained big. Had the fire not scorched the starling, then it would still be as large as the sea eagle today.

A man from Sauch (a place on the main island) went fishing. An evil spirit saw him and gave chase, to kill and eat him. However, the man fled into the bush. On his flight a tree opened in front of him and he slipped inside, upon which the tree closed round him. The pursuing spirit no longer saw the man and went away. When he had gone, the tree opened again and the man stepped out into the open. The tree said, ‘Go to Sauch and catch two white pigs for me.’ The man went away and caught one white pig and one black one, but striped the latter white with lime to deceive the tree. Then he brought the two pigs to the tree. However, on the way the lime coating had fallen off the black pig, and the tree realised that the man wanted to cheat him. He said, indignantly, ‘You are ungrateful! I sheltered you from the evil spirit, but you sought to deceive me. From now on when an evil spirit chases you I will not open up to protect you, and you will die. Had you done as I asked, then every time you were attacked by an evil spirit while going fishing, I would have opened up and sheltered you, but now I will never again open to protect you.’ And so the tree no longer offers protection to the man when he is pursued by an evil spirit.

A maiden named Nja Sa sat inside her house. Her parents had pierced her earlobes and had gone off into the garden. The evil spirit had seen them depart, slipped into the house and called out, ‘Come, Nja Sa, I am your suitor.’ Nja Sa peeped out through a hole and recognised him. She said, ‘You are the evil spirit.’ However, he kept up his assertion and called, ‘Let down the ladder!’ The maiden did not obey, and the spirit began to dig out the poles on which the house rested. Nja Sa screamed for help, and her parents rushed back to her cries. They saw the evil spirit, which had made himself as small as a child, and said, ‘It is only a game.’ However, Nja Sa told the truth. Her father grew very angry, grabbed a club and thrashed the evil spirit. However, the latter gave him a severe wound with one of his tusk-like teeth, so that the man had to cease the thrashing and the evil spirit was able to escape. 309

A woman cut off her finger while working, and caught the blood in a shell. Three days later the blood changed into two eggs, and a snake slithered from one and a bird from the other. The bird flew away and lay in wait for fish; the snake slithered into the forest and caught a possum. When the sun had gone down, they both came home; the bird brought fish to the woman, but the snake brought nothing. The bird said to the woman, ‘Let us go away!’ and he carried her up into a tall tree. He brought the hut up there as well. The snake searched for a long time in vain. He finally discovered their location and called out, ‘Mother, brother, how can I get up to you?’ The bird replied, ‘Climb up!’ The snake coiled upwards around the tree, but when it had climbed up the bird grabbed an axe and severed its head from the body, which fell down, but came to life again and resumed the ascent. However, up above, the bird raised the axe and cut up the snake into small pieces that fell down to the ground. Several became fish, others became snakes.

Hi Kalemuindr and Po Samitanpun paddled out to sea to catch turtles. The woman sat in the canoe while the man dived to the sea floor. He let himself down by a long rattan rope that he attached round his body, with the other end made fast to the canoe. While the man was below, the woman fell asleep, the rope broke and the canoe drifted out to sea. The chief Halives and his people noticed it. They paddled out to it, found the woman asleep and asked, ‘Where have you come from?’ She replied, ‘I have come from the west. My husband and I went fishing for turtles, but while he was diving I fell asleep and the west wind has driven me to you.’ Halives made her his wife and took her to Jap (Halives’ homeland).

When Po Samitanpun surfaced, he did not find his canoe, and swam ashore. He carved a bird out of wood and sent it off with the words, ‘Fly to Jap and search for your mother!’ The bird flew to Jap but did not find its mother but numerous crabs instead. It ate some and grew strong. Then it flew back and reported, ‘Father I did not find my mother.’ The father said, ‘Come closer to me,’ and when the bird obeyed the father sniffed his breath and cried angrily, ‘Yes, just as I thought, you have not found your mother; but you have eaten crabs.’ When the bird heard this reproach, it flew away enraged. Po Samitanpun then carved a sea eagle and said to it, ‘Fly away and find your mother! She is called Hi Kalemuindr, and when you see her, say to her that she should come to me.’ The sea eagle flew away to Jap and perched on a tree there. It shook the tree so that the fruit fell to the ground, and when the women heard it they ran to gather the fruit. When they returned to the village, laden, Hi Kalemuindr asked if someone would give her some of the fruit; but the women refused, and said, ‘Do you not have legs? Go yourself, and get fruit!’ She went to the tree with some other women. The sea eagle heard her name and immediately flew down to the ground, caught Hi Kalemuindr by the leg and flew away with her. On the way the sea eagle dropped down so that the water wet the leg of the woman, who cried out, ‘My son, my son, I am falling into the water!’ The sea eagle replied, ‘Do you trust the strength of my talons so little?’ It rose higher, and took the woman to Po Samitanpun. However, instead of being grateful he showered the sea eagle with reproaches, and said that it wanted to harm the woman at sea. The sea eagle was enraged at this and flew away.

Had injustice not been done to the sea eagle, it would have continued to bring back those shipwrecked on distant islands. However, Po Samitanpun had done so great a wrong that shipwreck victims nevermore returned, but had to remain wherever they had gone ashore.

Long ago on the island of Lou (St George Island) there was a great flock of tjauka (Philemon coquerelli). One day while the Lou people were at work, a man attempted to rape a woman, but a tjauka who witnessed this deed called out loudly, ‘A man of Lou is doing evil!’ and when the man realised that he was found out, he stopped his action and went home angrily. To get his revenge he distributed betel nuts throughout Lou as payment for wiping out all the tjauka. The Lou people caught all the tjauka in nets, and only one succeeded in hiding. It then sucked up all the water on Lou in its beak and carried it to Lom’ndrol on the main island. Since then Lou has been arid, while Lom’ndrol has an abundant water supply. Tjauka are no longer found on Lou, but they are numerous among the Moánus.

A number of Pitilu people went to Mbutmanda to catch turtles. The Papitálai people attacked and killed them all, except Po Toui, who hid. The canoes were taken away by the victors. Po Toui then decided to swim home. However, the sea sapped his strength, and he was close to drowning. He called to the spirit of his brother, and a shark came and carried him on his back to Pitilu. His brother’s spirit had entered the shark and hurried to the aid of Po Toui.

The Moánus believe that their spirit guardians occasionally enter sharks to come to the aid of those in trouble at sea. Likewise, the spirit can enter a sea eagle to give a prompt warning to a village threatened with danger. If a Moánus sees two sea eagles fighting or restlessly flying around, he does not continue his journey but goes back home.310

Plate 46 The gifu mask of the Sulka tribe