X

Languages

It was only in recent times that a little light was shed onto the involved linguistic relationships of the archipelago. The Wesleyan missionary Dr G. Brown was the first to study the language of the Duke of York Islands, and his Dictionary and Grammar of the Duke of York Islands (Sydney 1883) published in only a small number of autotyped copies, provided the first information on one of the languages of the archipelago. This was followed a number of years later by the far more detailed and more extensive work of the Wesleyan missionary R. Rickard, published as an autotype in 1889 under the title, A Dictionary of the New Britain Dialect and English, and of English and New Britain, also a Grammar. Both works showed the intimate connection of the two languages, and the Wesleyan mission soon found that in southern New Ireland the language was so closely related to both these languages, that the north-eastern Gazelle Peninsula language could be used without difficulty in their schools. Meanwhile the Catholic missionaries, whose settlements on the Gazelle Peninsula had spread extraordinarily rapidly over a large part of the Gazelle Peninsula since 1890, under the leadership of the extremely capable and hard-working Bishop L. Couppé, had also undertaken a study of languages, and in 1897 there appeared in volume 2 of the third annual edition of the Zeitschrift für afrikanische und ozeanische Sprachen, an extensive grammar of the language of the north-eastern Gazelle Peninsula by Father B. Bley, which he followed up in 1900 with a language dictionary, published in Münster by the mission press. I would also like to mention that in this work, for some unknown reason, the chapter on adverbs, that Father Bley had covered in detail, has been significantly curtailed. Both works complement and expand the earlier publication by missionary Rickard. Then, in 1903, the autotype publication of a grammar of the Baining language by Father M. Rascher appeared, in which is given a further valuable contribution to the study of the languages of the archipelago. An updated edition of this valuable work followed in 1904, in the Mitteilungen des Seminars für Orientalische Sprachen zu Berlin, annual volume VII, section I.

For the following information I am grateful to fathers B. Bley and M. Rascher who, in spite of the great workload resting on them, very kindly obliged me by preparing a short summary of their earlier investigations. From this a presentation of the languages of the Gazelle Peninsula is given in a rounded form, with the addition of studies on the related southern languages of the Sulka and the Nakanai, and the language of the Duke of York group in the north.

Although the darkness previously hanging over the interrelationship of the Bismarck Archipelago languages is, through these studies, beginning to lift, there is still infinitely more in this area to be investigated and defined, but the eager enthusiasm directed at this situation by the missions’ guarantees that this area of research will not be neglected.

1. The Languages of the Coastal Dwellers of the Northern Gazelle Peninsula

An homogeneous language exists among the coastal natives along virtually the entire northern coast of the Gazelle Peninsula, from Cape Birara to Massawa, including the island of Massikonápuka. Although these coastal dwellers are undoubtedly of common origin, and, according to currently accepted opinion, have crossed from the southern end of New Ireland to the north coast of the Gazelle Peninsula as plundering tribes; pushing the original inhabitants – the Butam, Taulil and Baining – into the interior, or occupying the coastal strips that the latter had forsaken on account of volcanic eruptions, these coastal dwellers still feel little affinity towards one another. More often, hostilities have reigned between most districts and villages on the coast since time immemorial, and fear of being attacked and captured, or of being eaten, hinders any approach between them. This favours maintenance of purity and further development of the various dialects that were probably brought in with immigration from New Ireland, 312and which all represent only different idioms of the language family held in common with the inhabitants of southern New Ireland. For these coastal dwellers, related by origin, traditions and customs, there is no common tribal name that we can assign to their language, in the way we speak of the Taulil language, or the Nakanai, Baining or Sulka languages, but they must be known simply as the languages of the coastal inhabitants of the northern Gazelle Peninsula.

According to a rough estimation by the former imperial magistrate, Dr Schnee, the total number of natives, heavily decimated by war and epidemics, who speak these languages today is only 20,000, or at most 30,000.

The greatest majority of these speak the melodious so-called Matupi or north coastal dialect, whose boundary actually begins about the middle of Blanche Bay near the villages of Dawaun and Kararoia, and extends along the coast to include Matupi Island, then stretches along the entire north coast from the village of Nonga to the middle of Weberhafen. From Weberhafen this dialect moves inland on the Gazelle Peninsula, extending over the entire area south of the Varzinberg, incorporating the districts of Napapar, Tombaul and Tamaneiriki.

On the coast of Blanche Bay, from Schulze Point to Kabakaul and inland as far as the Varzinberg, the so-called Blanche Bay dialect is spoken. This differs from the previous dialect both in the pure and harder consonants, b, d, g, compared with the gentler sounding mb, nd, and ng, of the former, and through several not-exactly beautiful-sounding variations in word form. Apart from the more uneven pronunciation, which sounds as though the people had blocked their noses while having their mouths half-open, a simple comparison of several words (Table 1) shows which part has the greater euphony.

We meet a further dialect in the villages at the foot of Mother and North Daughter; in Bai, Nodup, Korere and Tavui, towards Cape Stephens. This has the hard b, d, and g in common with the Blanche Bay dialect, but differs from it and the other dialects in many word forms, and sounds very broad, while adding an i to many word forms; for example, see Table 2.

This dialect prevails also on the north coast of the island of Uatom; moreover it is pronounced in almost a singing tone, and the hard terminal p changes mostly into a v. For example:

| north coast | northern Uatom | ||

| hedge | a liplip | a livilivi | |

| yam | a up | a uvu | |

| fire | a iap | a iavi |

Finally, from the middle of Weberhafen in the districts of Ramandu, Massawa, and on the island of Massikonápuka, we have the so-called Baining shore dialect, or s–dialect. It has the latter name because, as well as having deviating word forms it differs from the other dialects particularly in the frequently occurring s-sound, again demonstrating a great affinity with the language of southern New Ireland.

A few examples:

| north coast | Baining coast | ||

| stone | a vat | a vas | |

| earth | a pia | a pissa | |

| knife | a via | a vissa | |

| to sit | kiki | kiskis | |

| to go out | irop | siropo | |

| little | ikilik | sikilik | |

| to deceive | vaogo | vassere |

On the boundaries of both dialects, at Cape Livuan and on the island of Urar, both the north coastal and Baining shore dialects are spoken.

Seventeen letters suffice for writing the language: a, b, d, e, g, i, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, t, u, v (= w), to which the letter s must be added, because of the Baining dialect and essential foreign borrowings.

Table 1

| Blanche Bay dialect | north coast dialect | |

|---|---|---|

| canoe | a wagga | a oanga |

| my child | kaugu bul | kaningu mbul |

| banana | a wuddu | a wundu |

| thing | a maggit | a mangit |

| to give | tăbar | tambar |

| women | a wadān | a warenden |

Table 2

| north coast dialect | Nodup dialect | |

|---|---|---|

| sea | a ta | a tai |

| path | a ga | a gai |

| no | pata | no pata patai |

| where from? | mamāve? | memēvei? |

313The sounds c, h, f, z, x and ch are foreign to this language. The s, c, z and tz in foreign words and also sch, are, as in the Baining shore dialect, pronounced as t by the natives; thus ‘Jesus’, ‘Moses’, ‘sacrament’ become Jetut, Motet, and takrament. In the Baining shore dialect the s- sound is not pure, but is strongly mixed with the h- sound.

F and pf in foreign words become p in the mouth of the natives (for example, Jotep instead of Joseph); and ch becomes k (for example, Achab to Akap).

The sounds b, d, and g at Matupi and on the north coast are always mb, nd, and ng, and whereas q in the Blanche Bay dialect designates the pure hard g, it is only a more intensive ng in the north coast dialect – almost nk.

Among the vowels, a is by far the dominant one, and is almost as common as all the others put together. But although a certain monotony is created, the other vowels are fortunately distributed in such a way that the speech in general – assuming naturally that it is well pronounced – must be regarded as melodious, and one might with some justification be astonished that such a primitive people can possess such a fine language.

One becomes even more astonished in studying the grammar, both by its richness in form and by the clever manner in which missing forms are circumvented or substituted.

This language shares with all the Melanesian languages the article a for all genders, for the definite article ‘the’ and also the indefinite ‘a’ (while ta indicates ‘any’). Also, the personal article to in front of men’s names and ia in front of women’s names, is a common occurrence in the Melanesian languages, in similar form.

A surprise is the triple genitive form of the substantive, formed by the particles kai, na, and i; the first expressing actual ownership, the second determination or subject, the third belonging to the whole or family property.

Examples:

a pal kai ra tutane, the man’s house;

a pal na tutan, the men’s house;

a pal na kāpa, the tin house;

tama i ra tutan, the man’s father.

The dative is formed by the prepositions, ta, in, an; and the accusative, apart from the mostly euphonically essential form of the article, ra, is the same as the nominative.

The triple form of multiples: dual, triple and plural, provides no difficulty in the substantive, because they are formed simply by prefixing the numerals two and three and the plural particles a lavur and a umana (the former being the absolute plural: all of their kind; the latter the relative plural: representing several in speech).

The situation is more difficult with the pronoun, in which the inclusive and exclusive form must be differentiated in the dual, triple and plural, depending on whether the people spoken to are incorporated or not. An outline might illustrate this more easily.

|

Singular |

Dual | |

|

I. iau, I |

I. (inclus.) dor, we two (you and I) | |

|

(exclus.) amir, we two (another and I) | ||

|

II. u, you |

II. amur, you two | |

|

III. i, he, she, it |

III. amutal, the two | |

|

Triple |

Plural | |

|

I. (inclus.) datal, we three (you two and I) |

I. (inclus.) dat, we all (you and we) | |

|

(exclus.) amital, we three (two others and I) |

(exclus.) avet, we without you | |

|

II. amutal, you three |

II. avat, you all | |

|

III. dital, the three |

III. diat, they all |

We have an abundance of forms here, far exceeding that of European languages, but also establishing a brevity and precision of expression that is scarcely possible in another language. Equally numerous are the forms of the reflexive pronoun:

iau mule, I myself,

dor mule, we two ourselves,

datal mule, we three ourselves,

and so on, and of the possessive pronoun. In the latter, in all numbers and persons, besides the objective and substantive forms, a special form for determination or personal use is differentiated from possession. Here too we provide a plan, for the sake of clarity and brevity:

| Singular | ||||||

|

Possession |

Determination | |||||

|

I. kaniqu, mine |

I. aqu, for me | |||||

|

II. kou (koum), yours |

II. amu, for you | |||||

|

III. kana (kaina), his |

III. ana, for him | |||||

| Dual | ||||||

| I. | kador | I. | Ador | |||

| komamir | amamir | |||||

| II. | komamur | II. | Amamur | |||

| III. | kadir | III. | adir | |||

| Triple | ||||||

| I. | kadatal | I. | Adatal | |||

| komamital | amamital | |||||

| II. | komamutal | II. | amamutal | |||

| III. | kadital | III. | adital | |||

| Plural | ||||||

| Possession | Determination | |||||

| I. | kada (kadat) | I. | ada (adat) | |||

| komave (komavet) | amave (amavet) | |||||

| II. | komava (komavat) | II. | amava (amavat) | |||

| III. | kadia (kadiat) | III. | adia (adiat) | |||

The forms in brackets are the variations of the substantive form from the adjectival; where no 314special form is given, both are the same. For illustration of possession-indicating and determinationindicating pronouns, several illustrations follow:

They say: kaiqu pal, my house, but aqu nian, the food meant for me; komave boroi, our pig (possession), but amave boroi, pork meant for us; kou paip, your pipe (possession), but amu tapeka, tobacco for you, destined for your use; kana rumu, his spear (possession), but ana rumu, spear destined for him, by which he might be killed; kana market, his weapon, but ana bol, the bullet meant for him.

It is interesting, and in accordance with most Melanesian and several Micronesian (Gilbert Island) and Papuan languages, that in designations of relationship, body parts and several prepositions, the possessive pronoun is added as a suffix. For example:

|

tamaqu, my father |

tama i dor, our two fathers | |

|

tamam, your father |

tamamamir, etc. | |

|

tamana, his father |

amamamur | |

|

naqu, my mother |

naqu i dor | |

|

nam, your mother |

nam a mamir | |

|

nana, his mother, etc. |

nan a mamur | |

|

turaqu, my brother |

a limaqu, my hand | |

|

turam, your brother |

a limam, your hand | |

|

turana, his brother, etc. |

a limana, his hand, etc. | |

|

piraqu, near me |

taqu, in me | |

|

piram, near you |

tam, in you | |

|

pirana, near him, etc. |

tana, in him, etc. |

The relative pronoun is replaced sometimes by the personal pronoun, sometimes by the indicating nam or ni, sometimes by the particle ba.

The indefinite pronouns di and da for ‘one’ are probably abbreviations of the personal diat, ‘she’ and dat, ‘we’, while the indefinite ‘it’ is reproduced by the personal pronoun third person singular i; for example, i bata, ‘it is raining’.

The adjective can stand either before or after the substantive, and in the former case is connected to it by na, and in the latter by a, and takes the substantive form.

Examples:

|

a gala na pal |

a big house | |

|

a pal a gala |

a big house | |

|

a bo na tutan |

the good man | |

|

a tutan a boina |

the good man | |

|

a lalovi na davai |

a tall tree | |

|

a davai a lalovina |

a tall tree |

An actual gradation of the adjective does not occur, but there is a substitution for it, sometimes by juxtaposition, such as: qo i boina, nam i kaina, ‘this is good, that is bad’ (that is, this is better than that); or in the form: i boina ta dir, ‘he is the good one of the two’ (that is, the better); or: i gala taun diat par, ‘he is big above them all’ (that is, the biggest), or in similar circumlocutions.

Numerals, as almost throughout the South Seas, are based on the five or ten system. ‘Five’, a ilima, comes from lima, the hand. From 5 onwards the basic numerals are repeated with the prefix lap or lav, and from 10 on they are put together:

|

1 tikai |

6 a laptikai | |

|

2 a urua (or evut) |

7 a lavurua | |

|

3 a utul |

8 a lavutul | |

|

4 a ivat |

9 a lavuvat | |

|

5 a ilima |

10 a vinun (or arip) | |

|

11 a vinun ma tikai |

40 a ivat na vinvinun | |

|

12 a vinun ma evut |

50 a ilima na vinvinun | |

|

13 a vinun ma utul |

etc. | |

|

14 a vinun ma ivat |

100 a mar | |

| etc. |

200 a ura mar | |

|

300 a utul a mar | ||

|

20 a ura vinun |

400 a ivat na marmar | |

|

21 a ura vinun ma tikai |

1000 a mar na limana, | |

|

22 a ura vinun ma urua | ||

| etc. | ||

|

30 u utul a vinun |

2000, a tutan ot; that is, a whole man, or so many times 100 as there are fingers and toes on an intact man (assuming that the latter still has all his limbs, which is quite often not the case).

The scheme shows how impractically long these numbers are (for example, 948 = a lavuvat na marmar ma ra ivat na vinvinun ma ra lavutul), and how little they are suited to rapid usage in trade and commerce. In actual fact, the natives need few dealings with numbers in their life. Where they have not been educated in schools and taught to count, they have so little numerical skill that in counting up to 5 or 10 they have to use the fingers of one or both hands to help them to form and retain a number picture. The larger numbers: tens, hundreds and thousands, are used only when counting strings of shell money, which occasionally run into the hundreds and thousands. This is carried out extraordinarily slowly and carefully, with fingers and toes used as aids.

Wherever in life more rapid counting is required, unique counting methods are available. For eggs, a brood of young birds, pigs or dogs, the native uses a keva instead of ivat for 4, a ura keva for 8, and a utul a keva for 12; similarly for 5, a vinar instead of ilima, for 10 a ura vinar, for 15 a utul a vinar, for 20 a ivat na vinavinar, and so on.

For fruits that are bound into bundles, he calls a bundle of 4 a varivi, 8 a ura varivi, and so on; a bundle of 6 a kurene; 12 aura kurene, or a naquvan, a dozen; 120 a pakaruot. 315

He counts smaller shell money after nireit – that is, every six shells; he names larger ones after that part of the body up to which they reach.

Every eight slender strips of bamboo used for making fish baskets are called a kilak, and accordingly sixteen are a ura kilak, twenty-four a utul a kilak, and so on.

By doubling the cardinal numbers, the distributive numbers are obtained, such as tikatikai, each one; a evaevut, every two; a ututul, every three; a ivaivat, every four; a ililima, every five; a laplaptikai, every six, and so on.

By placing the causative particle va in front of the cardinal numbers, the ordinal numbers are formed; for example, a vaevut, the second –that is, ‘that which makes it become two’; a vautul, ‘that which makes it become three’ – that is, the third; a vaivat, a vailima, and so on.

The substitution of numeric adverbs is characteristic. Since there are actually almost no real numeric adverbs, so-called numerating adverbs are formed by prefixing the causative va, in the sense of, ‘to do something once’, ‘to do it twice’, and so on; for example, i vautul me means ‘he has tripled it’ – that is, he has done it three times. I vailima me, ‘he has quintupled it’, and so on.

The natives lack all understanding of precise fractions and thus lack precise names.

With verbs, as well as the transitive and intransitive there is often a third form as well, in which the object, when it is a third person singular personal pronoun, is already included, and thus does not need to be specifically expressed. For example, oro (intransitive) to call, ora to call him or it; virit to fish, virite to fish for him or it; qire to see, qure- to see him or it.

Another feature of the verbs that is a characteristic of most South Sea languages consists of doubling them. They are either partially or completely doubled, be it to indicate the intensity of treatment or of frequent occurrence, or to make transitive intransitive.

Time and mode of the verb are not expressed by verb alteration but by particles, and often do not coincide with those of European languages, as the following scheme shows.

| I. Present | ||

|

Singular |

Dual | |

|

iau vana, I am going |

dor (amir) vana | |

|

u vana, you are going |

amur vana | |

|

i vana, he is going |

dir vana | |

|

Triple |

Plural | |

|

datal (amital) vana |

da (ave) vana | |

|

amutal vana |

ava vana | |

|

dital vana |

dia vana | |

| II. Completed Present | ||

|

iau ter vana, I have (already) gone |

||

|

dor ter vana, |

||

|

dital ter vana, etc. |

||

| III. Just begun Past | ||

|

iau bur vana, I have just left |

||

|

dor bur vana, etc. |

||

| IV. Narrative Past | ||

|

iau qa vana, I went |

||

|

dor qa vana, etc. |

||

| V. Pluperfect | ||

|

iau qa ter vana, I had gone, have already been gone a long time | ||

|

dor qa ter vana, etc. |

||

| VI. Future | ||

|

Singular |

Dual | |

|

ina vana, I shall go |

dor (amir) a vana | |

|

una vana, you will go |

amur a vana | |

|

na vana, he will go |

dir a vana | |

|

Triple |

Plural | |

|

datal (amital) a vana |

dat (avet) a vana | |

|

amutal a vana |

avat a vana | |

|

dital a vana |

diat a vana | |

| VII. Future Anterior | ||

|

ina qa vana, I shall have gone, or will certainly go | ||

|

dor a qa vana, etc. |

||

| VIII. Future Presumptive | ||

|

na ter vana, he will probably have gone | ||

|

dir a ter vana, etc. |

||

Through the particle vala, a so-called habitual form is obtained. For example:

iau vala vana, I often go, have the habit of going

iau ter vala vana, I have often gone, etc.

In a similar way, through tiga a daily form is obtained: iau tiga na vartovo = I come every day for lessons.

In all its forms the imperative coincides with the future: una vana! go! avat a vana! go (plural)!, and so on.

Unfortunately, a real conditional is lacking, as well as the entire passive voice. In the former, one is aided by the particle ba in front of the indicative form, and in the latter by circumlocution with the active; for example, instead of ‘I am hit’, one says, dia kita iau, they hit me or, i kita iau, he hits me, or similar.

The above scheme has already shown how the conjugation particles form complete replacements for our auxiliary verbs, ‘to be’, ‘to have’, ‘to become’, ‘may’, and so on, in so far as these serve for the construction of time and manner. For ‘to be’, when it designates the relation of the predicate to the subject, a corresponding personal pronoun serves each time. For example:

a bul i gala, the boy, he big;

a ura bul dir gala, the two boys, the two big;

a utul a bul dital gala, the three boys, the three big;

a umana bul dia gala, the boys, all big.

316In spite of the apparent lack, in reality this language deviates so little that it almost never lacks a substitute form.

Still with the verb, besides the causative prefix va mentioned above, which signifies ‘to allow’ or ‘to make’ what the action of the verb does, we want to mention the prefix var in the formation of the reciprocal, occurring in similar form in a whole series of Melanesian, Polynesian and Papuan languages.

Examples:

tur, to stand; vatur to permit, or to cause to stand;

gala, to be big; vagala, to enlarge;

ubu, to strike; varubu, to strike one another, to fight;

vul, to insult; varvul, to insult one another.

Of the remaining word forms, adverbs of place deserve special mention, as much for their individuality as on account of their frequent use. In them, rest and motion must be precisely differentiated, as well as direction to the speaker, whether on the shore or forest edge (or conversely on the open sea), whether straight over the person addressed, whether over yonder, up above or down below is intended. Thus:

|

uro, outwards |

ura, downwards | |

|

aro, yonder |

ara, under | |

|

maro, from outwards |

mara, from below | |

|

urie, to the edge of the forest |

urike, towards the shore | |

|

arie, on the edge of the forest |

arike, on the shoreline | |

|

marie, from the edge of the forest |

marike, from the shore | |

|

urama, upwards |

ubara, downwards to you | |

|

arama, up above |

abara, down below near you | |

|

marama, from above |

mabara, from below near you |

The adverbs of place often replace prepositions, such as:

arama ra balanabakut, in the sky;

ara ra pia, on the earth;

aria ra pui, in the forest;

uria ra pui, to the forest.

They are usually also used where the indication of place has been done using a substantive with a preposition or in some other way. For example, arama raul a davai, ‘on the tree’; abara piram, ‘near you’.

As far as the real prepositions are concerned, their small numbers can be explained as due both to their replacement by adverbs, and the significance and manner of construction of many verbs that require no preposition. Thus, here too, the lack is only ostensible.

In the numerous interjections for the expression of astonishment and wonder, like aipua! ua! gaki!; of pain, like vele!; of compassion, like rabiavui!; of joy over the new moon or the presence of a lot of fish in the basket, like kuo! kuo! kuo! and other sentiments, this language can indeed measure up against others.

On the other hand, it is very modest in sentence construction. In simple sentences, the sentence parts can indeed be partially inverted and placed at the head for emphasis, but for longer sentence structures, or for coordinating or subordinating composition of sentences, both precise particles and the actual conditional form of the verb are missing.

If we compare the vocabulary of this language with that of European languages we must be amazed on the one hand by its great wealth and on the other hand by its great poverty. This language is uncommonly rich in names and designations for objects and processes, and in technical expressions from the daily life of the natives. Every plant, every forest tree, each one of over a hundred varieties of banana, each one of the numerous species of taro and creeper, every bird, every type of fish, every minute part of their huts, their canoes, their fishing baskets, has a special name. Every technique in house construction, fishing, and so on, has a short, precise technical expression that, because of its absence in our languages, we can reproduce only by a circumlocution of varying length. Often words coincide in a certain sense with European ones, but the slightest nuance, another situation, another object, requires yet another totally different verb.

On the other hand, the dearth of expressions from the area of the abstract, of spiritual life, morals, and above all from everything that passes beyond the horizon of notions in the natives’ daily lives, is very great. Above all, many general concepts, such as ‘plants’, ‘animal’, ‘human’, ‘person’, are missing. Others indeed exist, but do not correspond generally with ours, as, for example, bird, a beo, which also encompasses everything that flies, like beetles and butterflies. Mental powers and activities like comprehension, thought, volition, belief, are idiomatically never expressed in the abstract by the substantive, but always concretely by verbs: matoto, to understand; nuk-vake, to remember; meige, to desire; nurnur, to believe. However, in this area the language is still capable of modification, and permits – for example, by doubling the verbs – many new word constructions for abstract concepts. However, it will be necessary for the young people to become accustomed to the use of the abstract. The same applies to the area of morality.

It is obvious that the natives can have no expression for totally unknown or only unclearly felt ideas, such as gratitude, chastity, humility, modesty, and so on, but, here too, many a new word can be formed grammatically correctly, corresponding to 317the meaning of the word in European languages, while transposing it from the concrete into the figurative sense. But where this is not possible, one ought not to shy away from enriching and complementing such a beautiful language by introducing the simplest possible foreign words. One would fervently hope that in our German colonies German words would be introduced for missing words, rather than English, which has unfortunately occurred too often up till now.

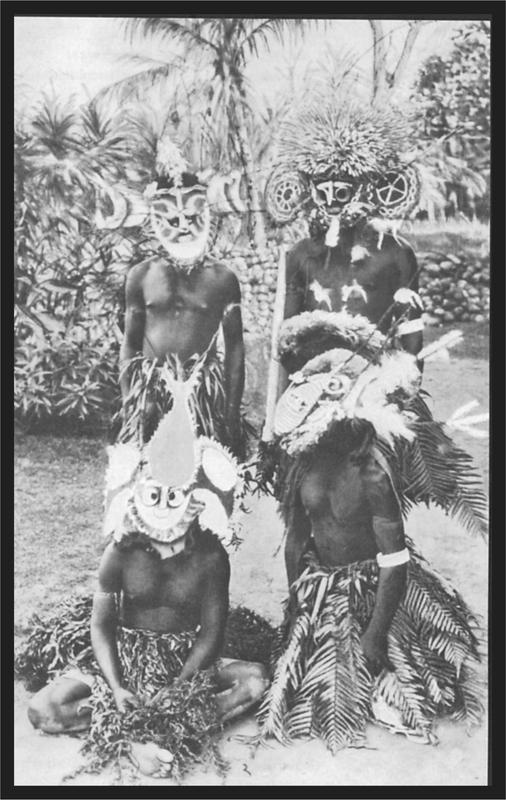

Plate 47 Dance at a circumcision ceremony. South coast of New Britain

For comparison with other South Sea languages, a list of a few common words follow, and as an example of speech, a translation of the Lord’s Prayer.

|

a tutan, the man a vavin, the woman tamana, his father moki! (address) my father! nana, his mother gaki! (address) my mother! a limana, his hand a matana, his eye a taligana, his ear a ta, the sea a tava, the water a oaga, the canoe a en, the fish a vat, the stone a davai, the wood, the tree a tabaran, the soul of the dead a balanabakut, the belly, the firmament, the heavens boina, good kaina, bad mat, dead ogor, strong laun, to live tur, to stand ki, to sit |

a mal, the clothing a luluai, the headman a pal, the house a vudu, the banana a lama, coconut tree and coconut a kian, the egg a vuaina, his fruit a pap, the dog a boroi, the pig vua, to lie vana, to go kakaile, to sing malagene, to dance pil, to leap ean, to eat kita, to strike kul, to buy log, to steal qori, today nabug, yesterday karaqam (ieri), tomorrow narie, the day before yesterday oarie, the day after tomorrow dari, so a kapiaka, the breadfruit tree |

The Lord’s Prayer

Tamamavet nam u ki arama ra balanabakut. Boina da ru ra iagim. Boina na vut kou varkurai. Boina di torom tam ara ra pia, veder di torom tam arama ra balanabakut.

Qori una tabari avet ma ra amave nian na bugbug par. Una nukue komave magamagana kaina ta nidiat, dia ter vakaine avet. Qaliak u beni avet ta ra varlam. Ma una valauni avet ka ra kaina. Amen.

2. The Duke of York Language

Lying between New Britain and New Ireland, the Duke of York group forms a natural connection between these two islands. One therefore easily tends to believe that the earlier migrations from south-western New Ireland to New Britain, especially in view of the imperfect vessels, all followed their natural route through the Duke of York group, and 318that therefore this island group was again a starting point for the various migratory expeditions, and that the language there was virtually the mother of the various northern Gazelle Peninsula dialects, which had gradually evolved and branched from it. Only a more intensive study of the Duke of York language seems to demonstrate that this can hardly be the case.

In any analogy, such a number of basically different elements are brought to light, mainly in the word forms and less so in the grammatical constructions, that one has to accept a completely independent development of the Duke of York dialect. On the other hand, as far as grammatical construction is concerned, the main similarity is with that of the northern Gazelle language, and the rules of the latter can almost all be applied to the former, with little alteration. Thus, without doubt, the Duke of York language belongs to the same idiom as the various dialects of the north-eastern Gazelle Peninsula and the south-western coast of New Ireland.

Moreover, in the Duke of York group, from island to island and occasionally from village to village, variants exist, based more or less on neighbouring dialects. Thus in Nakukur, woman = a tebuan (according to G. Brown’s dictionary), while on the island of Mioko and on the northern Gazelle Peninsula it is a vavina; whereas on Nakukur the latter word signifies only the female of animal species. ‘Long’, iok, iokana on Nakukur, is tia, tiaina on Mioko. Likewise, divai ‘tree’ and make ‘sun’ are nai and kake on the latter island. A great many words are originally different from those of the northern Gazelle language, such as those in Table 3.

A very large number of totally similar words with the same meaning as those of the northern Gazelle Peninsula demonstrate the original relatedness of both dialects; see, for example, Table 4.

With other words the similarity is immediately apparent. For example, see Table 5.

In many words of course the relationship does not leap so easily to the eyes, and it is only discovered when one goes back to the root of the words; for example, make (‘sun’, ‘heat’) is called keake on the northern Gazelle. The root of them both is ke; in the latter case it is doubled to keake, and in the former case it is changed into the perfect participle by the prefix ma, and is found in similar forms in the Baining s-dialect in maqes (‘sun’), or as the adjective in maqe, and makeke, ‘dry’. It is the same with ninogon and nagnagonai, ‘laughter’; akaka and kaina, ‘bad’; veum and varubu (root um = ub), ‘to fight’; teglik and taiqu (root ta), ‘brother’; tunalik and matuana, ‘nephew’; vekankan and varqanai, ‘to agree’, ‘to be happy’, and others.

This dialect has the broad ai in several words like tai (sea) in common with the dialects of Nodup and Tavui at the foot of Mother volcano; likewise the word toto, instead of bebe (butterfly).

Table 3

| Duke of York | northern Gazelle Peninsula | |

|---|---|---|

| house | ruma1 | pal |

| six | nom | laptikai |

| ten | noina | vinun |

| breadfruit | bare | kapiaka |

| to eat | utna | kaikai (nian) |

| bird | pika | beo |

| long | iokana | lolovina |

| man | muana | tutan |

| thing | lig | maqit |

| shell money | divara | tabu |

| spirit, image, shadow | nio | tulugean |

| as | len | veder |

| the demonstrative | kumi | qo |

| kuma | nam |

Table 4

| ki, to sit | pia, earth | pidik, secret |

| tur, to stand | bug, day | aman, outrigger |

| laun, to live | vo, paddle | tamana, his father |

| mat, dead | kiau, egg | nana, his mother |

| gala, big | burut, alarmed | bata, to rain |

| vana, to go | daka, pepper | dur, dirty |

| pula, blind | liplip, fence | kalagar, parrot |

| lama, coconut | tutun, to cook | lagun, border |

| up, yam | barman, yout | vat, stone |

| via, knife | dodo, stiff |

Table 5

| Duke of York | northern Gazelle Peninsula | |

|---|---|---|

| wood | divai | davai |

| to sleep | inep | diep |

| wind | vūvū | vuvu |

| fishing net | bene | ubene |

| bath | nirariu | niiu |

| small | liklik | ikilik |

| seed | patikina | patina |

| to do | pet | pait |

| mango | kai | koai |

| to cough | kogo | kaogo |

| ripe | mo | mao |

| to sing | kelekele | kakaile |

| pig | boro | boroi |

| canoe | aka | oaqa |

| soul | tebaran | tabaran |

| for, on account of | kup, kupi | up, upi |

| louse | nanut | ut |

| close to | matiti | matatai |

Table 6

| Singular | Dual | Triple | Plural | |

| on Nakukur | on Mioko | |||

| iau, I | dar (inclus.) | datul (inclus.) | dat (inclus.) | det |

| u (ui), you | mir (exclus.) | mitul (exclus.) | meat (exclus.) | met |

| i, he, she, it | mur | mutul | muat | mot |

| diar | ditul | diat | diat | |

Several identical or similar words probably originally had the same meaning but gradually became shaded to more or less related concepts, such as:

|

Duke of York |

northern Gazelle Peninsula | |

|

taurara, virgin |

widow, quarrel because of adultery | |

|

vavin, female animal |

woman | |

|

tebuan, woman |

tubuan, old woman | |

|

vinun, ten men |

ten in general | |

|

utul, three pairs |

three individuals | |

|

kuren, four fruits |

kurene, half a dozen |

The word par (all) here has the reversed form rap, just as diradira (flying squirrel) is reversed into ridarida in other places.

A brief overview of grammatical forms will show us on the one hand the great relationship of the northern Gazelle dialects with those of the Duke of York group, but, on the other hand also their differences, occurring particularly in the particles of construction.

To begin with, as on the Gazelle Peninsula, seventeen letters suffice for written representation of the language, and the letter ‘s’ has had to be added because of introduced foreign words.

The article a for all genders, and the personal article to is again common to both. Also, a special article is available for female personal names, but here it is called ne instead of ia or ja; for example, Neling becomes Jaling on the Gazelle Peninsula.

Exactly as on the Gazelle Peninsula, besides the singular, they differentiate a triple multiple-form, dual, triple and plural, and the triple genitive with na, i, and kai deviates only insofar as the posses-sive genitive has a nu instead of kai. The preposition tai for forming the dative on the Gazelle Peninsula corresponds with karom here, and has the same meaning. The dual is formed with ru and the triple with tul instead of ura and utul on the Gazelle Peninsula. Also, the plural has two forms, with in or kum, as in a in ruma or a kum ruma, ‘the houses’.

With regard to the adjective, in both its formation and its placement to the substantive and the designation of differences in gradation, there is no difference in treatment from that on the northern Gazelle Peninsula.

The personal pronoun is almost the same as on the Gazelle Peninsula. Table 6 indicates variations.

Also, the reflexive pronouns are formed, as there, by doubling the preceding form or adding ut (Gazelle Peninsula iat). 320

The possessive pronoun is likewise differentiated by a doubling: indicating possession and indicating assignment. The former is indicated in Table 7, the latter in Table 8.

The possessive pronoun is added also to several prepositions as a suffix:

| tag, to (at) me | nag, near me (for me) | |

| tam, to (at) you | nam, near you (for you) | |

| tana, to (at) him | nana, near him (for him) |

Finally, it is added to certain substantives, but in a more extensive way than on the Gazelle Peninsula. As well as to those substantives indicating relationships, body parts or parts of a whole, like those in Table 9, the possessive pronoun can also be added as a suffix to a whole number of other words, such as those in Table 10, and:

a divaraig, my shell money, but also: a nug divara;

a marig, my body decoration;

a pinapamig, my garden;

a lamaig, my coconut;

a akaig, my canoe.

The relative pronouns are, as on the Gazelle Peninsula, replaced by personal pronouns, or by pronouns indicating ownership, or can be left out completely.

The interrogative ooi? ‘who’? and aua? ‘what’? correspond to toia and uva on the Gazelle Peninsula.

However, the demonstratives, kumi, kuma, kumia, and bi, are different.

|

on Nakukur |

on Mioko | |

|

1 ra |

1 ra | |

|

2 ruadi |

2 ruo | |

|

3 tuldi |

3 tul | |

|

4 vatdi |

4 vat | |

|

5 limadi |

5 lima | |

|

6 nomdi, or limadi ma ra |

6 nom2 | |

|

7 limadi ma ruadi |

7 talaqarua | |

|

8 limadi ma tuldi |

8 lakatul | |

|

9 limadi ma vatdi |

9 latakai | |

|

10 noina |

10 noina | |

|

20 ru noina |

20 ruo noina | |

|

50 a lima na noina |

50 a lima na noina | |

|

60 a nom na noina |

60 a nom na noina | |

|

100 a mar |

100 a mar | |

|

Ordinal numbers | ||

|

Nakukur |

Mioko | |

|

the first, a mukana |

a muqana | |

|

the second, ra i patap |

dina | |

|

the third, ru i patap |

dituina | |

|

the fourth, tuldi i patap |

datavavat | |

|

etc., etc. |

the fifth, datalalima | |

|

the sixth, datanonom | ||

|

the seventh, datalakarua | ||

|

the eighth, datalalima | ||

|

the ninth, datalakakai | ||

|

the tenth, nonodet | ||

Table 7: Indicating possession

| Singular | Dual | Triple | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| a nug, mine | a nudar | a nudatul | a nudat |

| a num, yours | a numir | a numitul | a numeat |

| a nuna, his | a numur | a numutul | a numuat |

| a nudiar | a nuditul | a nudiat |

Table 8: Indicating assignment

| Singular | Dual | Triple | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| agag, for me | amadar | amadatul | amadat |

| amam, for you | amamir | amamitul | amameat |

| ana, for him | amamur | amamutul | amamuat |

| amadiar | amaditul | amadiat |

Table 9

| tamag, my father | nakug, my mother | tug | ||

| tamam, your father | nam, your mother | or | my child | |

| tamana, his father | nana, his mother | natig | ||

| matag, my eye | limag, my hand | |||

| matam, your eye | kapig, my blood | |||

| matana, his eye | etc. |

Table 10

| rumaig, my | a nug ruma, my | ||||||

| rumaim, your | house, but also: | a num ruma, your | house | ||||

| rumaina, his | a nuna ruma, his |

| Distributive numbers | ||

| are formed by duplication of the cardinal number | ||

| Nakukur | Mioko | |

| every 1, rauravin | rara or lapara | |

| every 2, ruruvin | rurua or laparua | |

| every 3, tultulavin | tultul or lapatul | |

| every 4, vatvat na vin | vatvat or lapavat | |

| every 5, limlim na vin | limlimo or laplima | |

Variations here from the northern Gazelle language are a special kind of counting for pairs, where the first five numbers almost coincide with the cardinal numbers of the Gazelle Peninsula, but on the other hand they do not disown their pure Polynesian origin. Thus they are:

| 1 pair, kai | in Samoan, tasi | |

| 2 pairs, urua | in Samoan, lua | |

| 3 pairs, utul | in Samoan, tolu | |

| 4 pairs, luvat | in Samoan, fa | |

| 5 pairs, tilim | in Samoan, lima | |

| 6 pairs, ma nom | in Samoan, ono | |

| 7 pairs, ma vit | in Samoan, fitu | |

| 8 pairs, tival | in Samoan, valu | |

| 9 pairs, tiva | in Samoan, iva | |

| 10 pairs, tikina | in Samoan, sefulu |

Most of the other varying forms of numbering for fruit, shell money, eggs, animals and humans are quite different from equivalent numbering methods on the Gazelle Peninsula; thus, here, a inagava is a 200-shell piece of money; there, on the other hand, it is four eggs or youths.

In the verbs, the transitive suffixes tai and pai correspond with tar and pa on the Gazelle Peninsula. The ending tau is perhaps the similarsounding preposition: ‘on’, ‘over’. The causative prefix va also exists here, and ve corresponds with the prefix var in forming the reciprocal.

With regard to the partial or total doubling of the verbs, the same rules apply as on the northern Gazelle Peninsula.

In conjugation the verb remains unaltered. In the present tense only the pronoun precedes the unaltered verb (see Table 11).

According to the Reverend G. Brown, the perfect should be expressed by inserting a long a between pronoun and verb. This seems erroneous to me; I rather believe that it is the particle ta, as in the Nodup dialect, where ta is also used instead of tar or ter on the Gazelle Peninsula. As it seems, the particle of the perfect is used less often here, and narrates mostly in the present, if the past already stems from the rest of what is said.

The imperative coincides with the forms of the future tense (see Table 12), and the conditional is like the indicative, and is differentiated only by the particles ba, ‘so that’, ‘if’; duk, ‘perhaps’; kaduk, ‘lest’.

The entire passive voice, with the exception of a few perfect participles, is missing and, as on the Gazelle Peninsula, is replaced by circumlocution with the active voice.

The small number of prepositions is based both in the significance that no preamble is required and in the use of adverbs which often take the place of prepositions. The most essential real prepositions are ko, kon ‘from’; karom, ‘to’, ‘at’; ma, ‘with’, ‘from’, ‘through’; na, ‘by’, ‘for’; ta, tan, ‘in’, ‘at’.

Of all types of word, adverbs deviate the most from those of the northern Gazelle Peninsula; only very few are totally the same, like na bug, ‘yesterday’; na taman, ‘outside’. Yet others are not totally dissimilar in form, and are perhaps originally from the same stem, although no longer with the same meaning, like:

| Duke of York | Gazelle Peninsula | |

| urin, to this place | urie, to the shore | |

| urog, away, from | uro, over there | |

| unata, unaga, upwards | urama, upwards | |

| amaganate, above | arama, above | |

| una pia, on the ground | ura ra pia, to the ground | |

| ura bugbug rap, all day | ra bugbug pa, all day | |

| iu, ioi, maia, yes | maia, yes | |

| pate, my | pata, no |

The adverb nakono (on the shore) corresponds to the adverb with the same meaning on the island of Uatom: naono.

The following are totally different:

Table 11: Present

| Singular | Dual | Triple | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| ian van | dar van | datul van | dat van |

| ui van | mir van | mitul van | meat van |

| i van | etc. | etc. | etc. |

Table 12: Future

| Singular | Dual | Triple | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| ag van | dar a van | datul a van | dat a van |

| un van | mir a van | mitul a van | meat a van |

| in van | etc. | etc. | etc.322 |

|

Duke of York |

Gazelle Peninsula | |

|

kumari, today |

qori, ieri | |

|

kumi ut, nadirik, now |

qoko | |

|

unaburu, naboroa, tomorrow |

karaqam, nigene | |

|

umera, uragra, the day after tomorrow |

oarie | |

|

ulogra, three days ago |

naria liu | |

|

gen, igen, apart |

arirai | |

|

lelavai, leloa, why? how? how? |

dave? | |

|

lenkumi, lenkuma, lenma, so |

dari |

The conjunctions ma, bulug, kaduk, ba, correspond to the Gazelle Peninsula words: ma, ‘and’; bula, ‘also’; kan, ‘lest’; ba, ‘when’, ‘if’. Ku corresponds probably to the end-syllable ka, ‘only’. On the other hand, kuma, ‘because’, differs from taqo on the Gazelle Peninsula.

Since interjections often vary even from village to village, there are deviations from those on the Gazelle Peninsula, like au! instead of aipua; a peu! instead of ra biavi! and others of lesser significance for the comparison of both dialects.

In any event, this brief comparison shows that in spite of the great similarity of both languages, and the consequent original affinity, basically different elements are nevertheless present in the Duke of York language; searching for their origin would still be an interesting project in further language investigation.

3. The Baining Language

Just as the Baining is different from neighbouring tribes in his physiognomy, traditions and customs, he differs also in language. This deviates in many ways from the great Melanesian family of languages.

A general feature of Melanesian languages is the presence of a triple; the Baining language lacks this. It has merely three numbers: singular, dual and plural. Formation of the pronoun, which is so painfully precise in most Melanesian languages, is less advanced here. There are no inclusive and exclusive forms, and furthermore a proper possessive pronoun is missing for words that indicate relationships or body parts. The Baining language recognises no difference in possessive pronouns and does not append them to the substantive, but always places the possessive pronoun in front of the substantive.

A further, and probably the most significant feature of the Baining idiom consists, in my view, in that it is an inflected language. The word endings are altered to express the different numbers.

The vocabulary is totally divergent from that of the Melanesian languages known so far, right down to insignificant exceptions.

The grammatical outlines of the Baining language are as follows.

I. Phonetics

The Baining alphabet has 22 sounds:

1. vowels: a, e, i, o, ä, ö;

2. consonants: b, ch, d, g̃, g, h, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, u, v.

Vowels and umlauts are the same as those in German.

Note in regard to the pronunciation of consonants:

a) b must always be pronounced by sounding an m in front; for example, a bieska, is pronounced a mbieska, ‘the wound’.

b) ch sounds far more gentle than our ‘ch’; somewhat like the German ‘g’ as the terminal sound after ‘a’, ‘o’, ‘u’ in ‘Lug’ with the assonance of ‘ch’.

c) d has, like b, an epenthesis, n; for example, a dulka, is pronounced a ndulka, ‘the stone’.

d) g̃ corresponds to the ‘ng’ in ‘long’; for example, g̃oa, is pronounced ngoa, ‘I’.

e) combines the two sounds g̃g; for example a gunarka, is pronounced a nggunarka, ‘the pencil’.

Note: If the vowel following g̃g (=g) drops off, the pronunciation of the g becomes g̃ for example, a muga, ‘the tree’, a mug̃, ‘the trees’.

f) h is pronounced like our German ‘h’. But, it has the characteristic that at the beginning of a word and as a medial sound it can be replaced by an s; for example, a hur or a sur, ‘the fences’. h is never a terminal sound, except when a vowel follows; for example, ka tes, ‘he is eating’; ka te ut, ‘he is fighting against us’.

g) k does not have the hard palatal plosive sound as in German; it sounds almost like our ‘g’ at the beginning of a word.

k between two vowels changes to ‘ch’ in the third person singular personal pronoun; in other cases usage decides it. For example, a choátka cha mit, ‘the man he goes away’, but on the other hand goa aka, my friend.

h) p between two vowels must be changed into v; for example, g̃u tav a mug̃ instead of g̃u tap a mug̃ ‘I am felling trees’.

i) t between two vowels is usually changed into r; for example, g̃oa rar instead of g̃oa tar, ‘I am bathing’.

II. Lexicology

The Baining language is founded on the following five basic rules:

- The noun-substantives are divided into several groups distinguishable by suffixes.

- All the other classes of words, with the exception of adverbs, prepositions, 323conjunctions, interjections, and sometimes verbs, when related attributively or predicatively to a noun, adopt the syllables corresponding to the noun, in all numbers.

- The words (substantive, adjective and pronoun) of the first and second groups, designating creatures endowed with intellect, have an unique pronoun for the third person plural (ta, ti, tu).

- All designations for creatures without intellect, in the plural, belonging to the first and second groups, and the singular and plural of words of the third group regardless of whether or not they concern rational beings, have just one pronoun (in the singular and plural), namely g̃a or g̃et (g̃eri).

- Words of the first group have a special possessive pronoun in the singular and plural (a – a ra).

The words of the second and third groups have the same possessive pronoun for singular and plural, namely at.

1. The Article

a) The definite and indefinite article is a (ama) in singular and plural, for all cases; for example, a ika, ‘the bird’, plural a ik; a muga ‘the tree’, plural a mug̃.

b) The article is placed in front of nouns, adjectives, numerals, the possessive pronouns, ‘ours’, ‘yours’, ‘theirs’, and the three persons of the dual. For example:

a nanki, the woman

a mer g̃oa, I am well (‘well I’)

a ratpes, we

a ur a luan, our clothes

a g̃en a luan, your clothes

a ra a ruis, their children

a un a chip, our two spears

a oan a lat, your two gardens

a ien a vrika, their two slingshots

c) A number of words, mostly those expressing a relationship or parts of the body, occur without articles, and only in conjunction with the possessive pronoun. For example:

gu mam, ‘my father’;

gu nan, ‘my mother’;

goa ren, ‘my body’.

2. The Substantive

a) The Baining language has three numbers: singular, dual and plural.

b) No unique suffix in the plural form corresponds to the suffixes of the singular of the first and second groups.

c) Only one special form of the dual suffix (iem) supports the various suffixes of the first group.

d) Similarly, only one special form of the dual suffix (im) supports the various suffixes of the second group.

e) Also one of the dual as well as the plural supports the various suffixes of the second group.

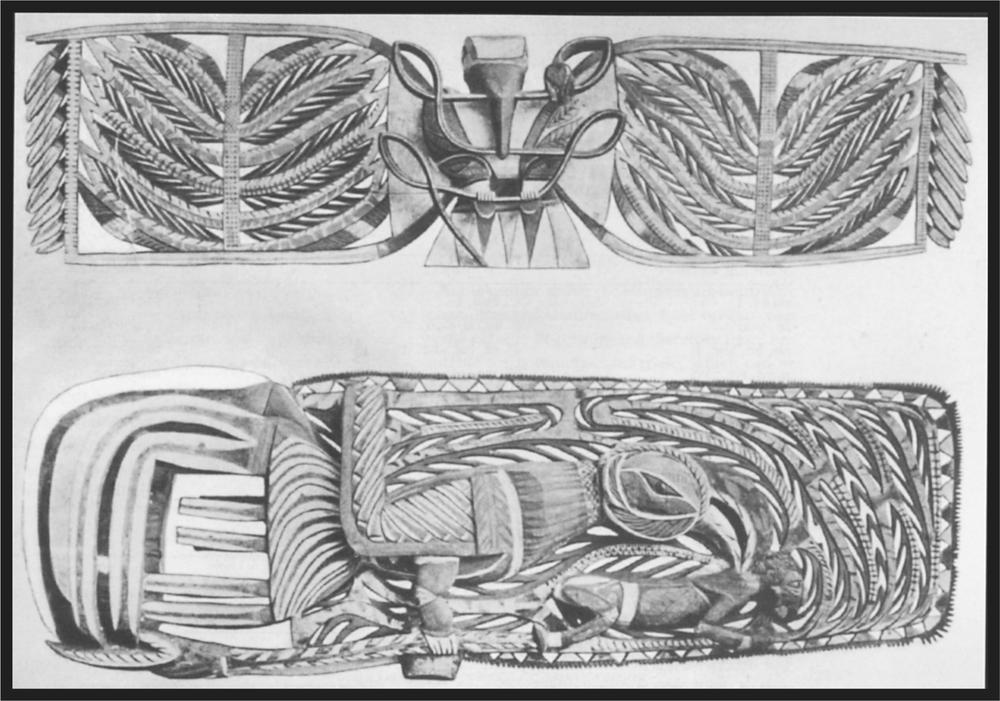

Plate 48 Mask house on New Ireland. In the lower row, ordinary dance masks (tatanua); in the upper row, totem masks (kepong)

324Annotations:

1. Suffixes of the first group in the singular: acha, cha, ka, ga

Suffixes of the second group in the singular: eichi, chi, ki, gi

Suffixes of the third group in the singular: ini, eit, bit, igl, um, em, bem, ar, as, us, es.

2. Most words of the first and second groups can take the derivative syllables (suffixes) of the third group.

Observations on the three numbers:

A. Singular

Mam, ‘father’; nan, ‘mother’, and several others have no singular ending.

B. Dual

1. The dual in the first two groups is formed by appending the ending iem or im to the stem, depending on the ending of the substantive, to its stem. For example, a igelka ‘the boy’, stem: a igel, dual: a igeliem; a igelki, ‘the girl’, dual: a igelim.

2. Each of the various suffixes of the third group, with the exception of as, has its own dual ending, which is appended to the stem of the word:

| ini | singular | iram | dual | |

| it, eit, bit | singular | ihim | dual | |

| igl | singular | igrim | dual | |

| ar | singular | isum | dual | |

| em (um, bem) | singular | am, bam | dual | |

| as (us) | singular | ihim | dual |

C. Plural

a) In the words of the first and second group:

Formation of the plural occurs by omitting the singular ending (suffix). For example:

| a vaska singular, ‘breadfruit tree’, | a vas plural | |

| a leichi singular, ‘the door’, | a lei plural |

b) In the words of the third group:

Each of the six classes is aided by an unique plural suffix, as evident from the summary in Table 13.

Examples: a larini, ‘the small garden’; a lariam, ‘two small gardens’; a larirag̃, ‘small gardens’.

Table 13

| ini | singular | iram | dual | irag̃ | plural |

| it, eit, bit | singular | ihim | dua | isig̃ | plural |

| igl | singular | igrim | dual | igrig̃ | plural |

| em, um, bem, | singular | am, bam | dual | ap, lap | plural |

| ar | singular | isum | dual | isug̃ (itnek) | plural |

| as, us | singular | isim | dual | isig̃ | plural |

Annotation:

The suffixes of the third group each have a specific meaning. For example:

a mug̃ini, ‘the sapling’;

a mug̃igl, ‘a small piece of wood’;

a mug̃em, ‘a piece of wood’, and so on.

Declension

a) Genitive

The subjective and objective genitive relationship is expressed by a corresponding possessive pronoun. For example:

| a | choatka | a | a | chipka |

| the | man | his | the | spear |

| a | choata (irregular plural) | a | ra | chip |

| the | men | theirs | the |

spears |

| a | choariem | a | ien | a | chiviem |

| the | two men | the | their both | the | spears |

| a | nanki | a | r | a | niska |

| the | woman | to | her | ki thelt |

| a | nankina | a | ra | a | nis |

| the | women | to | them | the | kilts. |

Annotation:

The corresponding possessive pronoun varies in form according to the different groups of the substantive.

b) Dative

There is no unique dative particle. The dative is expressed by circumlocution as in pronouns and prepositions. For example:

| Thu | tal | a | arepki | hair | Paskam |

| I | am carrying | the | axe | to | Paskam. |

| The | chur | a | savireicvhi | ra | ltigi |

| You | are giving | the | people | the gift | of fire. |

| Nemka | a | a |

hinki? |

Ka | goa | hinki |

| Who | owns | the | knife? | It is | my | knife. |

3. The Adjective

The attributive adjective can stand before or after the substantive.

In both cases it has ama or a as a joining particle.

a) Where the adjective is in front of the substantive, it is the unaltered determinative word with the preceding article, both in the singular and in the plural. For example:

a mrer a choatka, or, better,

a mrer ama choatka, ‘the good man’ 325

a mrer ama nanki, ‘the good woman’

a mrer ama nankina, ‘the good women’

b) Where it stands after, the substantive retains its article and the objective is bound to it by the simple article or its expanded form (ama); moreover the adjective itself undergoes certain further alterations, according to how it stands in relation to a substantive of the various groups. For example:

a choatka ama vucha, ‘the man the bad’

a nanki ama igelki, ‘the woman the small’

a choariem ama viem, ‘the both men the both angry’

a nanim ama igelim, ‘the both women the both small’

a lapki ama pelki, ‘the cockatoo the small’

a lavim ama plim, ‘the both cockatoos the both small’

a choata ama hlur ta, ‘the men the big they’

a nankina ama vu r a, ‘the women the angry they’

a lav ama pel g̃et, ‘the cockatoos the small they’

c) Where the subject is a pronoun and the predicate an adjective, the latter always stands in front of the pronoun. For example:

a vu g̃oa, ‘angry (am) I’

a vu cha, ‘angry he (is)’

4. The Numeral

The numerals up to and including 5 are simple; the rest are compound.

1 = a choanáska, a choanaski, etc.

a gig̃sacha, a gigsichi, etc.

2 = a rekmeneiem (first group)

a rekmeneiem (second group)

a odochim (second group)

a onpim (second group)

3 = a dopgues

4 = a ratpes or a bag̃eigi

5 = a g̃arichit

6 = a g̃arichit a demka, etc.

7 = a g̃arichit dat demiem, etc.

8 = a g̃arichit dat demg̃er ama dopgues

9 = a g̃irichit dat demg̃er ama ratpes

10 = a garichigrim.

Annotation:

Numbers above 10 are not customary.

5. The Pronoun

a) Personal

See Table 14.

b) Possessive

See Table 15.

c) Indicative

1. a, ära, aiet, la, ‘that, this’

They always follow the substantive, without any alteration.

2. lucha, singular (first group), luicha, singular (second group), ‘this, that’

liema, dual (first group), lima, dual (second group)

lura, plural (first and second group) for persons

Table 14: Personal pronouns

|

g̃u, I |

un, we two, the both of us |

|

g̃oa, I, me, to me |

ut, we, us |

|

g̃i, yog̃, you, tg̃ you |

g̃en, you, you |

|

g̃ie, you |

ta, ti, tu, they, for persons (first and second groups) |

|

ka, ki, ku, he |

g̃a, g̃et, they, for persons (third group) and things |

|

kie, chie, she | |

|

chie, she (object) | |

|

g̃a, g̃et, ini, it |

Table 15: Possessive pronouns

| goa, mine | a ien, their two |

| gu, mine | a ut, our |

| gi, your | a g̃en, your |

| a, his | a ra (persons, first and second group) |

| a t, her |

a t, their (persons third group; and things, first, |

| a g̃et, his, her | |

| a un, our two | |

| a van, your two326 |

lugera, plural (first and second group) for non-rational beings

lina, lira, luma, etc., for the third group singular.

Annotation:

lucha can stand before or after the substantive. When it is in front, it is connected to the substantive by the expanded article ama; for example, lucha ama doelka, ‘this stone’.

Where it stands after, it follows the substantive without any connecting particle; for example, a doelka lucha, ‘this stone, the stone there’.

d) The interrogative

nemka? singular, first group, ‘who?’ nemiem? dual, first group; nemta? plural, first group

nemki? singular, second group ‘who?’ nebim? dual, second group; nemta? plural, second group

nemg̃et? plural, first, second and third groups, ‘who?’ in words designating non-rational beings.

Annotations:

1. nemka, used substantively, is always placed in front; for example, nemka cha rekmet nini? ‘Who did it?’ nemka, used adjectively in the sense: ‘what kind of..’ is always placed following; for example, a nanki nemki? ‘What kind of woman?’ a ik nemget? ‘What kind of bird?’

2. nemka also has all the derivative forms of the three groups.

a igacha? singular, ‘what?’ ‘what kind of? (first group)

a igichi? singular, ‘what?’ ‘what kind of? (second group)

a igiem? dual (first group)

a igim? dual (second group)

a igig̃et? plural for all three groups

Annotations:

a igacha, like nemka, can take all the derivatives of the three groups.

e) The indefinite

ta, ti, tu, ‘one’, actually ‘she’

sichik, tarak, ‘another’

bak, ‘anybody’

Annotation:

sichiak and tarak have definite suffixes for the second and third groups, as does the substantive.

6. The Verb

1. Various types of verb are differentiated in the Baining language:

a) those that have the personal pronoun in front

b) those that have the personal pronoun following

c) those that are formed from a substantive or adjective and a preposition. Prepositions and pronouns follow the substantive.

2. The Baining verb, like the noun-substantive, has three numbers: a) singular, b) dual and c) plural, and each one has three persons.

3. Also, the Baining verb has three tenses: present, future and perfect.

4. In the present and future tenses, the actual stem of the verb does not undergo any alteration, except for many abbreviations.

5. In the perfect, the stem sometimes remains unchanged, and sometimes is abbreviated, or undergoes changes of sounds.

6. Temporal difference (future and perfect) is expressed by the particles i, ik, ip, for the future, and sa for the past.

Paradigms of the verb

a) Verb with preceding pronoun

| Present | |||

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| g̃oa tes, I eat | un tes | u tes | |

| g̃ie tes | oan tes | g̃en tes | |

| ka tes | ien tes | ta tes | |

| kie tes | g̃a tes. | ||

| g̃a tes | |||

| Future | |||

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| ik g̃oa tes | iv un tes | iv u tes | |

| ik g̃ie tes | iv oan tes | ik g̃en tes | |

| i ka tes | iv ien tes | i ta tes. | |

| i kie tes | |||

| ina g̃a tes | |||

| Perfect | |||

| sa g̃oa tes | sa oan tes | ||

| sai g̃ie tes | sa ien tes | ||

| sa cha tes | sa u tes | ||

| sai chie tes | sa g̃en tes | ||

| sa un tes | sa ra tes | ||

| Imperative | |||

| g̃ie tes or sai g̃ie tes, ‘eat’ | |||

| g̃en tes or sa g̃en tes, ‘eat’ | |||

| u tes or sa u tes, ‘let us eat’ | |||

b) Verb with subsequent pronoun

|

kudas g̃oa, ‘I do not want to’ |

kudas uin | ||

| kudas g̃i | kudas iem or im | ||

| kudas ka | kudas ut | ||

| kudas ki | kudas g̃en | ||

| kudas ini | kudas ta | ||

| kudas un | kudas g̃et327 | ||

Future

i chudas g̃oa, etc.

Perfect

sa chudas g̃oa, etc.

c) Verb formed from a substantive and a preposition

Present

a chreika vra g̃oa, ‘I am fasting’, literally: ‘the fasting to me’

a chreika vrei g̃i

a chreika vra cha

a chreika vrei chi

a chreika vra un

a chreika vra uin

a chreika vre iem

a chreika vra ut

a chreika vra g̃en

a chreika vra ra

Future

i a chreika vra g̃oa

Perfect

sa a chreika vra g̃oa

7. The Preposition

Prepositions are:

| ba, bark, barak, for | ||||

| bedeg̃, up to | ||||

| da, in, on, at, near | ||||

| mar, met, at, on, in, through | ||||

| men, through | ||||

| mirk, about | ||||

| munkrup, in the middle | ||||

| pa chlichi, in the middle | ||||

| n, nama, in front of, with, out of | ||||

| nair, through, from | ||||

| namen, from, out of | ||||

| nanir, after, about | ||||

| narak, after, during | ||||

| nav, from, out of | ||||

| navr, from, out of | ||||

| gel | ||||

| gelem | ||||

| gelemna na | near, in the vicinity, during | |||

| gir | ||||

| girna | ||||

| p, pet, per, in, over, behind, with, to, after | ||||

| pr – rut, under | ||||

| t, tik, tichem, in front of | ||||

| tuar – tuar, this side, that side | ||||

| la, over, on account of, with | ||||

| sair, to | ||||

| sak, after, behind | ||||

| sar, sarem, after, at, to | ||||

8. The Adverb

1. Adverbs of time

|

lära, now |

nasat, afterwards | |

|

la, leip, today |

da arenkaris, at night | |

|

biga, tomorrow |

da a chorévetki, in the moonlight | |

|

biga d’oarik, early tomorrow |

||

|

sa unun, in the evening | ||

|

areip, one day |

||

|

a aber na aren, often |

da niracha, by day | |

|

mas, always |

da niracha a a ren, at noon | |

|

nauir, at first |

||

|

sies, mäka, again, once more |

2. Adverbs of place

|

a, ära, ti, here |

ámuk, there | |

|

na ri, from here |

d’eg̃erkig̃, on the beach | |

|

koa? koari? koaridi? where to? where? |

da rik, outside | |

|

da ra ren, inside | ||

|

na choari? where from? |

imak, below | |

|

pusup, above |

na imak, from below | |

|

men a evet, on the earth, on the ground |

ávano, over there | |

|

pa unes, in the shade | ||

|

pa chöol, in the bush |

3. Adverbs of manner

|

perhet, sa chap, enough, ready |

sa na? how? | |

|

pa, almost | ||

|

g̃u ikag̃, I am quick |

manep, deeply | |

|

mavik, bad |

duchup, useless, futile | |

|

tachorära, tachorá, so |

a chasna? how many? | |

|

meni, over, past |

malei, maden, very, strongly, firmly | |

|

ia? iva? eviva? why? |

||

|

neik, naka, only, merely |

4. Adverbs of negation

koasir, not, no

kuku, no, absolutely not

as koasir, as kuku, not yet

5. Adverbs of affirmation

|

e, echerer, yes |

lucha iet, that is it | |

|

kachoia, yes of course |

lura iet, those are they (people) | |

|

saka, all right |

6. Adverbs of possibility

ari, ani, perhaps

aekoa? koa? perchance?

ei, if

328

9. The Conjunction

|

ai – da, when i, because den – den, both – and tika, also kan, ‘and’, for combining persons and things in the singular (first group) chien, ‘and’ for combining persons and things in the singular (second group) |

i ari, that about i kurima, lest ten, ‘and’, for combining people (first and second groups) da, ‘and’, for combining verbs and substantives dat, dap, and, but koarik – koarik, either – or |

10. Exclamation

|

aria, get away, come on, at work |

achai, cry of amazement | ||

|

ai, ae, quite right |

sóka, finished, cry when job finished | ||

|

kové? is that so? | |||

|

vai, u, to call someone |

ave, yes, naturally |

Vocabulary

1. Substantive

| a ioska, ghost of thedead | a óveska, head | |

| a n’racha, sun, day | a lámsacha, coconut palm | |

| a váldagacha, star | a alimki, sugarcane | |

| a rmriki, rain | a vlemka, pig | |

| a évetki, earth | a dága, dog | |

| a lochúpki, village | a nevága, mouse | |

| a éska, path | a cháelka, wallaby | |

| a chavilki, island | a máracha, crocodile | |

| a doelka, stone | a lápki, cockatoo | |

| a chánki, ashes | a áneska, parrot | |

| a ltígi, fire | a chaivichi, bush fowl | |

| a eichí, water | a gárumki, cassowary | |

| a ruchanépka, sea | a husúpka, sky | |

| a moega, tree | a chorévetki, moon | |

| a chă lbă ga, bark, skin, hide | a arenki, night | |

| avípki, adder | ||

| a nat, taro | a líbicha, fish | |

| a áchavetka, banana | a choigoiga, butterfly | |

| a avesemka, betelnut palm | a étki, louse | |

| a chasig̃em, hair | ||

| a rlépka, flea | a sãkãncha, eye | |

| a choátka, man, husband | a chrimki, nose | |

| mam, father | a sdémki, ear | |

| nan, mother | a richit, arm | |

| a uémka, child | a richígl, hand | |

| a rǔ cha, brother | a rika, finger | |

| a nánki, woman | a éleig̃it, leg | |

| a lg̃iéska, headman | ag̃eleiÏígl, foot | |

| a rsavracha, slave | a avetki, house | |

| a cháchracha, Baining | a arepki, axe |

2. Adjective

| a hlur, big | a chloi, black | |

| a dlok, strong | a gilál, red | |

| a mer, good, beautiful | a uis, cold | |

| a haru, old | a vu, angry | |

| a igel, small | a miÏiés, rotten | |

| a chlak, weak | a bup, full | |

| a iámes, green, young | a balu, ripe | |

| a lua, white | a aretkína, wise | |

| a vlu, short |

3. Verb

| támen, táchen, tuchun, to speak | lu, to see | |

| teig̃, to sing | pin, to come | |

| nen, to request | nem, to send | |

| su, to teach | sep, to fall | |

| kal, to prohibit | máravit, to stand | |

| kak, to tell a lie | hap, to catch | |

| drem, to know (how to), to be able to | tap, to | |

| cause to fall, bring down | ||

| tit, to go | mig̃, plag̃, to kill | |

| iachu, to fear | rkur, to give | |

| mes, to eat | rbur, to be irritated, | |

| angered by | ||

| neig̃, to drink | knak, to weep | |

| breig̃, to sleep | nari, to hear | |

| tas, to lie | nin, to cook | |

| snes, to call | suau, to thieve | |

| main, to dance | sep, to fall | |

| a iámes, to live | tu, to set up | |

| sal, to give birth | tǎlǎk, to ruin | |

| rekmet, to make, to do | tǎněg, to hold | |

| tal, to fetch, to carry | rĭgǔs, to rub | |

| ig̃ip, to die | tat, to help | |

| túma, to laugh | tmǎtnǎ, to work |

Examples of speech

The Lord’s Prayer

See Table 16.

Conversation

See Table 17.

The Spider and the Fly

See Table 18.

4. The Sulka Language

At first glance, on skimming briefly over a vocabulary, the Sulka language appears to have a great affinity with the Gazelle Peninsula language, since you find a multitude of totally similar-sounding words, like mat, kagal, matmat, momo, mi, kor, lul, mama, taktak, kaur, and so on. But when one compares the meanings of these words, not the slightest similarity remains, and one must wonder how such a large group of words, quite independent from those of the Gazelle Peninsula, have retained the same phonation. Comparing only, see Table 19. 329

Table 16: The Lord’s Prayer

| A ut mam, lug̃ia va husup, i ti achu gi a arenki, i kie n | |

| You our Father, the you in the skies, that one fears your the name, that it comes | |

| gi a lg̃ichi, i ti nari gelem g̃i vra évetki, rachoar ti nari gelem g̃i va | |

| your the word, that one obeys to you on the earth, as one obeys to you in the | |

| husupka. Lei g̃ie vana ut ta ur a smeski, g̃ie reg̃ev a ur a | |

| sky. Today you present us with the to us the food, you discharge from us the | |

| vug̃et, tachoar u reg̃ev a ra a vug̃et, ti ralak sut; kurimai g̃ie | |

| evil things, as we discharge from them the evil things, they do evil to us; not may you | |

| rut naut savra vug̃et, dap g̃ie ra ut namena vug̃et. Amen. | |

| lead us into evil things, but you take away us from the evil things. |

Table 17

|

Goa ak, koa gie drem, ama eska samet ma Sankt Paul? |

My friend, do you know roughly the way to Saint Paul? | |

|

E, goa dremacha. |

Yes, I know it. | |

|

Gie ren da gie nagoa. |

Come, go with me (literally, ‘you to me’). | |

|

Kudas goa, mácha cha ruchun, ik gun nacha savra lat. |

I can’t, (my) father said, I had to (go) to the garden with him. | |

|

Gie n di iv lei ik gu chureigi rama suiki. |

Come, and I will give you a gift of tobacco today. | |

|

Ari gu mam ka hirin nagoa. |

Perhaps my father will be angry with me. | |

|

Ai iv uri ravlag, da un tit ságel mácha, ik goa ruchun |

When we both come back, we will go to (your) father, I | |

|

nacha, i gun neigi. |

will tell him that I (was) with you. | |

|

Kure du goa it nanir goa ga-teichi. |

Wait while I fetch my arm-basket. | |

|

Gie kag satmit, dav as goa ruchun mena mugaiet. |

Go quickly, and I will sit down (meanwhile) on this tree. | |

|

Sa lugoaiet. |

Here I am (again). | |

|

Gie tal goa luanigl, di gie uir. |

Wear my garment and go ahead. | |

|

Gu ruir. |

I am going in front. | |

|

Koa ama eska cha tit pit? |

Does the path climb high? | |

|

Luära cha tit meni da sa amá-mano cha tit pit. |

It is flat-going now, but later it climbs. | |

|

Koarich ama eska cha tit pra chöol, da choarik pa inim, |

Does the path go through the jungle, or through bush, | |

|

da choarik pra ratem? |

or through grass? | |

|

Echerer, ka tit pa chöol, da vra inim. |

Yes, it goes through jungle and bush. | |

|

Koar ama eichi chirna nama eska? |

Is there any water near the path? | |

|

E, ma Navi da ma Rivun. |

Yes, the Navi and the Rivun. | |

|

Navi ära gelemna, a leichi meneichi. |

Here is the Navi, a bridge crosses it. | |

|

Nemka cha rach a leichi ära? |

Who built this bridge? | |

|

A chavilkiruemka. |

The whites. | |

|

Koar ama lba ra mat navracha seichi? |

Did the coastal dwellers help them? | |

|

Kuku, mäitika ama chavilkiruemka. |

No, the whites alone (built it). | |

|

A muga nemka ära ama gaunipka? |

What kind of tree is this tall one, here? | |

|

Ka ama galipka. |

It is a galip. | |

|

Koa cha tu a gam? |

Does it bear fruit? | |

|

Echerer, ka cha tu. |

Yes, it does. | |

|

Koa gen tes get? |

Can you eat them? | |

|

Ka u tes get. |

We eat them. | |

|

Koar ama ich i choasir ga tes ama galip? |

Don’t the birds eat the galip? | |

|

Ka ama gaman gen ama marag ga tes get. |

The pigeons and the hornbills eat it. | |

|

Koar ama aber nama gaman gelemgen? |

Are there many pigeons where you are? | |

|

E, ka a malei naget. |

Yes, there are a lot of them. | |

|

Karak preigi, a ika nemka ära cha knak? |

Quiet (be silent), what bird is that, calling? | |

|

Ka ama barbaruoichi. |

It is the barbaruoichi. | |

|

J chie nana? |

What does it look like? | |

|

A chloigi. |

It is black. | |

|

Koa ama hlurki? |

Is it big? | |

|

Ka ama hlurki rachoar ama chaivichi. |

It is as big as the bush hen.330 |

Table 18

| A sinepki chien ama slageichi | |

| The Spider and the Fly | |

| A sinepki chie msem a r a his. Kie tuchun: Slag̃eihi, g̃ie dlu, i kurimai | |

| A spider she spun her strands. She said: Fly, you be careful, lest | |

| g̃ie tit savet g̃oa his. Ari dig̃ si g̃i a ichivaret prag̃et. Dav ama slag̃eichi chie | |

| you go into my web. Perchance entangle your wings in it. But the fly she | |

| tuma di chie tuchun: Naka ama dlok g̃oa, nach lei ik g̃oa ralak | |

| laughs and she says: Only (but) the strong I am, and only today, now shall I destroy | |

| sag̃et. Kie tit di dig̃ sa a r a ichivaret prag̃et. Kie prer | |

| it. She went (in) and they entangled themselves her wings in it. She defended (herself) | |

| malei, i kie chuvik, dai duchup. A sinepki chie g̃ag̃ sagelemki di chie | |

| fiercely, so that she would get free, but in vain. The spider she went to her and she | |

| pligi samra r a his. | |

| killed her in her strands. |

Table 19

| On the north coast | Among the Sulka | |

|---|---|---|