II

New Ireland and New Hanover and their Offshore Islands

1. The Land

The island of New Ireland (Carteret’s ‘Nova Hibernia’) is long and narrow, separated in the south-west from the Gazelle Peninsula by St George’s Channel.

The southern tip of the island, Cape St George, lies at 4º51’S, and 152º52’E. The mountains over 2,000 metres high, on the southern part of the island, are visible from a great distance. On closer approach, the eye perceives a seemingly unbroken forest from the beach up to the highest mountain peaks, interspersed here and there with green grassy meadows on the eastern side. Deep valleys divide various mountain chains stretching from south to north, of which the central chain, the Rossel Range, is the highest. Both to east and west the mountains extend almost directly into the sea; a narrow foreshore exists only here and there. Streams large and small pour into the sea from the numerous gorges; there are no navigable rivers. In the dry season these streams are to a large extent harmless rills; after heavy tropical rain, especially during the rainy season of north-westers, they suddenly transform into mountain torrents which float mighty forest trees into the sea and carry huge boulders and much rubble along with them. Especially on the eastern side, in the Siara district south of Cape Santa Maria, these watercourses are particularly large, and when one is sailing past the stream beds they appear as though they were broad causeways leading inland.

On the maps part of the island still bears the name Tombara, a designation that the natives do not know, and is derived from the word tanbar (south-east wind or south-easterly direction). It is high time for this name to disappear from the maps.

The high, southern part of the island stretches mainly from south to north, with a small mountainous projection pointing north-west. The greatest breadth of the island here reaches about 30 nautical miles, the north-south length about 60 nautical miles. The continuation of the highlands stretches a further 25 nautical miles north-west, and then drops off fairly steeply into a depression connecting this part of the island with the main part, which is traversed by the Schleinitz Range. This depression, between the villages of Kurumut in the west and Nabutu Bay in the Bo district to the east, is not much more than 5 nautical miles wide. Stretching to the north-west, the Schleinitz Range forms the backbone of the island and then gradually becomes lower to end finally on the flat North Cape.

The total length of the island from Cape St George to North Cape is about 200 nautical miles.

In the east a number of small islands lie offshore. Coming from the south we first encounter the small St John group (named Wuneram by the Solomon people, and Aneri by the inhabitants of the New Ireland coast opposite), consisting of a larger mountainous island and a smaller hilly one. As far as I could ascertain the larger island is called Ambitlé by its inhabitants, and the smaller Bábase. North-west of St John lies the small group of the Caen Islands. This consists of a southern island, Malenaput, off which the smaller islands of Malelif, Maletafa and Bit stretch out to the south-east, separated by narrow sea channels, and a northern island, Tanga, separated from the southern island by an arm of the sea about 6 nautical miles wide.

About 45 miles north-west of the Caen Islands is the bigger island of Gerrit Denys, Lir or Lihir, and then in a northerly direction the small islands, San Bruno (Mali), San Joseph (Massait), and San Francisco or Maur. About 30 nautical miles west of Gerrit Denys lie the two Gardner Islands, and separated from the northern one by an arm of the sea is Fischer Island or Simberi. I am still unclear as to the names of the two Gardner Islands. Although I visited them quite often and made various inquiries, I never succeeded in gaining satisfactory results. Other new names were always given me, so that I finally came to the conclusion that I was being given the names of individual districts. On current maps the strait that separates both Gardner Islands is depicted incorrectly; it lies rather further north, and separates the islands in such a way that the northern one is the smaller and the southern one the larger. On New Ireland opposite, both Gardner Islands are called Tabar.112113

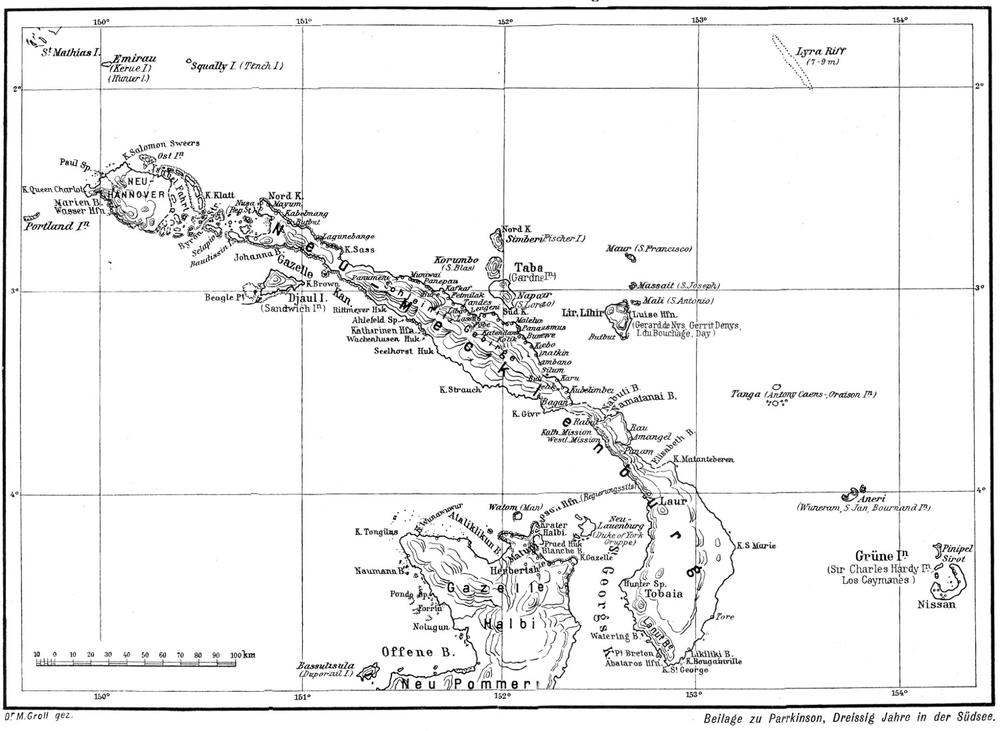

Map 3 New Ireland

114All these islands are high and mountainous, and for the most part volcanic. On Gerrit Denys and St John numerous hot springs rise here and there from the ground, and the earlier craters are still clearly visible. Besides the volcanic rock, raised coral formations also occur, and island groups are more or less surrounded by coral reefs.

South of the north-western end of the island of New Ireland lies triangular Sandwich Island (Djaule) with a small island at the northern end. This island consists totally of raised coral banks.

Between New Ireland and New Hanover which is situated about 25 nautical miles further west, there are numerous large and small islands and islets which belong ethnographically partly to New Ireland and partly to New Hanover. Two straits navigable by the largest ships, Steffen Strait and Byron Strait, run through this maze of islands from north to south. All the islands consist of coral limestone.

The island of New Hanover itself measures about 25 nautical miles from east to west and about 20 nautical miles from north to south. In the north and north-east a few small raised coral islands lie on coral reefs, forming relatively good anchorages, with their reefs and the larger island opposite. About 4 nautical miles south-west of the westernmost point of New Hanover, Cape Queen Charlotte, lie the small, low Portland Islands on a common reef. The principal island, New Hanover, consists in part of raised coral formations; however, the higher part of the island reveals other rock, although a geological investigation has not yet established what it is.

The surface area of all the above-mentioned islands totals approximately 13,500 square kilometres, that is, about the size of the grand-duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and the extent of the islands from Cape St George in the south to Cape Queen Charlotte in the extreme north-west is 247 nautical miles or 470 kilometres.

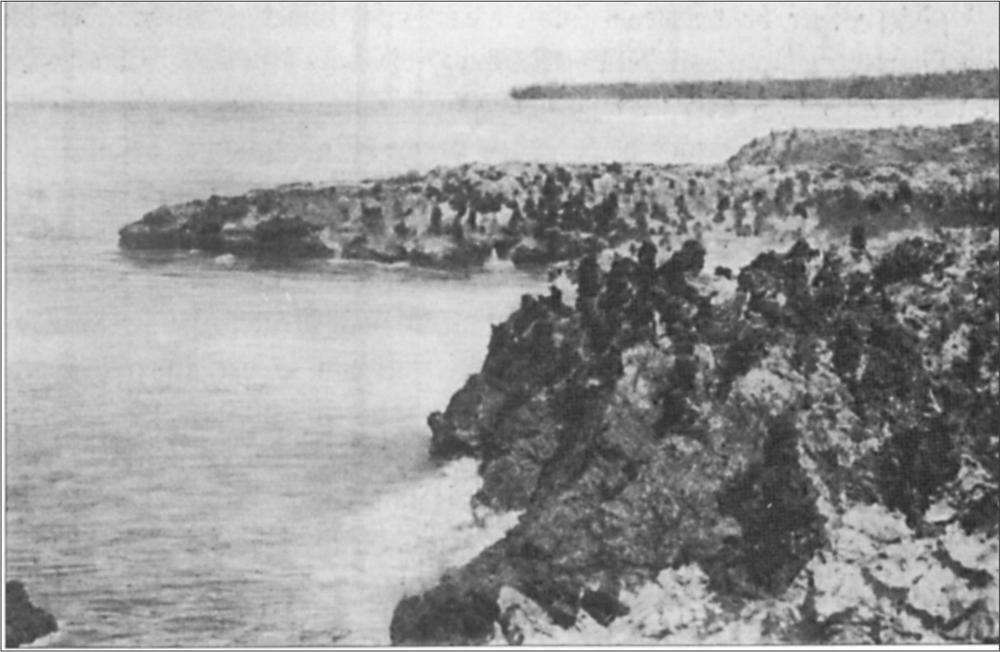

Fig. 42 Northern tip of the island of Nusa. Raised coral reefs

I will now attempt to give a detailed description of New Ireland as I have come to know it from numerous journeys. The coasts are especially wellknown; exploration of the interior has only been undertaken in most recent times. The southern highlands with the mighty Rossel Mountains make a great impression by the steepness of the mountains and the multitudinous transections of them by deep gorges and valleys through which the mountain streams seek to make their way, foaming and roaring, to the sea. The east coast drops steeply into the sea everywhere, and only in the northern part, south of Nabutu Bay, does the land flatten. The west coast has the same character, except that several small harbours, known to us since the time of Dampier and Carteret, lie a little north of Cape St George. The first of these harbours, Port Praslin, lies beyond the small island of Latau, between it and the main island; however, it is of minor importance as an anchorage. Somewhat better is the small harbour lying about 2 kilometres north, formed by the small island of Lambon (Wallis Island) and the main island. As a consequence of the high mountains of the main island and the equally impressive height of the island of Lambon, it is to some extent sheltered from the prevailing winds, but it will never be of importance as a harbour since the surrounding land is steep and rocky, and unsuitable either for building houses or for establishing plantations. It was here that the famed expedition of the Marquis de Ray eked out its existence for a while at the beginning of the 1880s. The harbour is named Port Breton on the maps. About 5 nautical miles further north, another harbour, Carteret Harbour, is formed by the small island of Lamassa (Coconut Island) and the main island. This, although somewhat more spacious than the previous two, is of little value for the same reason. The harbours would only be of value if mineral wealth of any kind were found in the interior of the island, and it could be transported overland to them. It is not improbable that the mountains of this part of the island contain minerals. Even by the end of the 1870s, Australian geological authorities had announced the possibility of finding minerals, after examination of rock samples submitted to them; recently coal has been found at one site, although indications are that it is of poor quality; but since only the most superficial layers have been examined, it is not impossible that further investigations of deeper layers will produce a better result. Neither on the east nor on the west coast of this part of the island is there a completely secure anchorage; the steep shoreline drops just as quickly below the surface into the depths, and depths of several hundred metres are found close inshore.

The Rossel Mountains extend a ridge about 1,000 metres high to the north-west, gradually lowering towards the village of Kure. Towards St George’s Channel this extension of the mountain 115range drops steeply away; to the east, from Cape Matantéberen to the inlet indicated on the maps as ‘Grosse Bucht’ [Deep Bay], the mountain is fronted by a not insignificant flat of excellent fertility, and east of the cape is an anchorage (Elizabeth Harbour), which is well protected at times. The plain is particularly well inhabited, and village follows after village. The opposite coast is quite heavily populated as well, as is the Siara district south of Cape Santa Maria on the east coast and the districts of Topaia and Laur on the west coast. Inland, in the valleys and on the mountain slopes, dwells a population which is usually on a war-footing with the shore dwellers. However, as far as we know, the mountains are on the whole only sparsely settled.

The previously described southern part of the island, to a certain extent, forms one main division of New Ireland, geologically differing from the part stretching further to the north-west.

Between Kure and Deep Bay (Nabutu Bay) is a depression that reaches no more than 200 metres tall and is about 5 nautical miles wide from shore to shore. The part of the island beyond, connected with the southern mountain region by this depression, is raised coral limestone throughout, forming a long ridge stretching to the north-west, the Schleinitz Mountains. Certainly in external appearance this mountain chain differs from the southern highlands. The mountains are broad, rounded domes, and the valleys are less steep and deep; the height too is less and barely reaches 1,000 metres. This part of the island has its greatest breadth, about 21 nautical miles or 40 kilometres, in the region opposite the Gardner Islands. The Schleinitz Mountains gradually flatten towards the north-west, and finally terminate in a gentle ridge which runs out into the north-west plain.

That this part of the island has been raised up at different periods of eruption is clearly evident on the north-eastern coast. The coast here often forms steep, coral limestone walls which stretch like a frequently interrupted embankment from the Gardner Islands to North Cape. Inland this wall does not fall steeply away, but passes gradually into a plain that is very swampy in places. This plain is of varying breadth, and is particularly prized by the natives because of its fertility. After traversing it one is suddenly confronted by the steeply falling coral limestone walls of the mountains, which still in places show the earlier shoreline clearly, where heavy, pounding swells have produced grottoes with broad, overhanging roofs. The swampy plain has undoubtedly been a lagoon in prehistoric times, bordered by a barrier reef which was interrupted by passes, and now forms the outer wall of the shore. This structure appears very clearly at Nusa Harbour on the north-western tip of the island. On the partially deforested former barrier reef, which drops quite steeply to the present shoreline, lie the administration centre of Kavieng and the houses of various traders. Beyond is an extensive lowland plain, the former lagoon, which is now covered to a great extent with coconut plantations and native settlements. The deep undercuts which now lie at least 10 metres above sea level demonstrate that this former barrier reef too has been subjected to repeated uplifting. A further example of this is given by the Dietertberg (220 metres) and above all by Mausoleum Island (Salapio) between Steffen and Byron straits, which have a pronounced terrace structure, and in which the various stages of uplift are clearly recognisable.

The entire archipelago filling the gap between New Ireland and New Hanover is a result of these uplifts.

Before I turn to an account of these islands, I want to describe the most recent part of the island of New Ireland in rather more detail. Both the north-eastern and the south-western coasts have no harbours; in places there is a shoreline reef, against which the sea breaks with great force; where the reef is absent, the ocean rolls its waves directly against the rocks onshore. The north-eastern coast is well populated as far as North Cape, where there are quite considerable stands of coconut palm whose produce is sold by the natives to the traders settled here and there. The south-west coast is less rich in coconut palm stands and settlements, but is nevertheless fairly well populated; here the villages lie at greater or lesser distances from the shore and the natives concentrate mainly on taro and sago for food. South of the north-western corner lies the small island of Djaule (Sandwich Island) which plays a major role in the mythology of the northern New Ireland people. It is somewhat triangular with a westerly directed baseline about 4.5 nautical miles long; the other sides are both about 7 and 6 nautical miles long. Both this island and Archway Island to the west, and small Angriffs Island offshore from the coast of New Ireland opposite, consist of raised coral formations. Mount Bendemann (200 metres) on Djaule is the highest uplifted feature. Between the islands off the north-western end of New Ireland there is good anchorage for ships; the most well-known is tiny Nusa Harbour, a little south of North Cape. Here ships up to medium size find a safe, spacious haven, bordered to the east by the main island, and to the west by the small islands of Nusa, Nusalik and Nago. As a consequence, the various agencies of the island trading firms are also located here, and it is also the site of the imperial administration for this part of the island.

Cultivations have been undertaken on New Ireland only recently. Several of the small islands on Steffen Strait have been planted out in coconut palms by whites, and the imperial administration has set up extensive coconut palm plantations at Nusa harbour near the Kavieng administration 116station. Trade with the natives has been going on since the beginning of the 1880s, when the firm of Hernsheim & Co. founded the first settlement on the small island of Nusa, and a second soon after on Kapsu, about 20 nautical miles south-east of North Cape. Both these settlements experienced a very precarious existence for a time; first they were attacked by the natives and the traders killed, then they were occupied once more by enterprising people who kept the business going. Today, when relations can be considered relatively under control, a large number of such trading stations have been established on the north-eastern coast.

Missionaries were in the field before the traders, for in 1875 the Wesleyan mission founded the first stations on the New Ireland coast opposite the Duke of York Islands. They have made good progress here and currently support a larger number of missions under the leadership of Samoan or Viti teachers who are under the control of a white missionary. Since 1902 the Catholic mission, which has its main base in New Britain, has also settled on this coast.

The archipelago between New Ireland and the island of New Hanover consists, as already mentioned, exclusively of raised coral banks and depositional islands, which over the course of time have become overgrown with luxuriant vegetation. They are separated by numerous straits and arms of the sea, navigable in some places by larger ships, and in other places not even passable by small boats. The most significant are the two passes leading from north to south, known as Steffen Strait and Byron Strait. Straits that are less deep, but still navigable by medium-sized ships, are Albatross Channel between Baudissen Island and the Kabien Peninsula on the main island, and Ysabel Strait between the east coast of New Hanover and the series of smaller islands offshore. Some of these islands are inhabited; the majority, however, are unpopulated, probably because, until quite recently, first the New Hanover people then the New Ireland people (depending on whether or not the island inhabitants were tribally related to them), attacked and killed them. Recently, with the development of more peaceful relations, settlements on the islands have increased, and enterprising whites have acquired a portion of them in order to transform them gradually into coconut plantations.

The island of New Hanover is mountainous and rugged in its south-western half; the mountains gradually flatten towards the north-east and form an extensive, fissured plain which is enclosed by a border of mangrove swamps on the shore. The mountain range is not yet sufficiently well known, but does not consist exclusively of raised coral banks, although these do exist on the coasts. The mountains are distinguished by their steepness and several of them, like the approximately 400-metrehigh Stoschberg, bear the greatest similarity to a gigantic sugar loaf. The soil of New Hanover is extremely fertile, and since there are enough safe anchorages in the north and east, the entire northeastern half of the island is eminently suitable for tropical plantations.

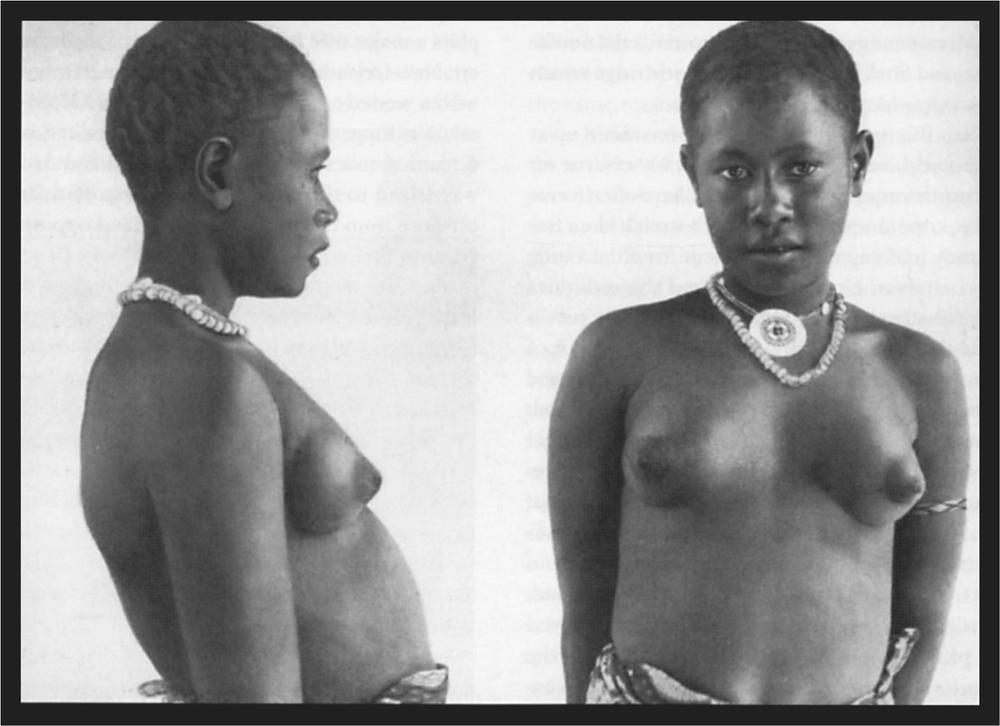

Plate 17 Girl from northern New Ireland

New Ireland is of lesser significance in this regard. True, there are larger and smaller stretches excellently suited to the cultivation of tropical products, 117but rapid development of this island will always be hindered because of difficulties arising from sea transport due to the lack of good, safe anchorages. After setting up administration stations the imperial administration with great energy undertook road construction. Already, good roads lead from the northern end of New Ireland along both the east and west coasts, and with crossroads linking both coasts of the island in several places, this has improved into a road system that encourages trade.

2. The Natives

Now let us turn to the population: here, just as in New Britain, we can distinguish several main tribes spreading over the countryside from certain centres. Just as the mountainous southern part of the island is significantly different geologically from the less hilly north-western part, so too do the inhabitants of each part of the island differ significantly from each other in many aspects. The inhabitants of the southern part (as I have established in greater detail on New Britain), are closely related to the inhabitants of the Duke of York Islands and of the north-eastern Gazelle Peninsula. The population of the north-western part is very different in speech and in ethnography from their southern neighbours, although a blending and a gradual transition from one to the other is clearly recognisable. The original border between the two tribes was certainly the narrow tie between Kure and the east coast, where the last projections of the Rossel Range fall away to the north. The southern tribe, crossing this border, has mixed with the north-western tribe. Further settlement of the north-western part of the island appears to have taken place from New Hanover. Above all, on closer examination of the population we find strongly pronounced differences, which indicate that a mixing of very different elements has taken place. This is not quite so striking in the southern part of the island as in the north-western part. In the latter, besides dark-brown or blackbrown people, who are barely distinguishable from someone from Buka or Bougainville, we find pale individuals whose skin colour is no darker than that of the Samoans or Tongans. The paler skin colour is particularly prevalent among the women, and many of them, in spite of the curly hair, surprisingly call to mind Polynesians. Some of the merchants who settled here married native girls, and the children born of such unions quite often have smooth, fair hair, and blue or grey eyes; in Europe they would not stand out in a pure-blooded crowd of children. I feel it would be an interesting proposition to study in more detail the various mixtures that are now encountered in such great numbers in the South Sea islands. Through this tribal cross-breeding there arise many strange forms that might be able to give us a hint about the origins of tribes that are today regarded as a uniform type, but which might possibly be the result of interbreeding of different races. I know, for example, a girl of about fourteen whose father is Chinese and whose mother is a full-blooded native of the Gazelle Peninsula. If one were to send the girl to Wuwulu or to Aua, one would without doubt regard her as a native of that place; skin colour, the lightly wavy hair, the characteristic, yet less slanted, mongoloid eyes: everything fits the traits on those islands perfectly.

In another case, where the mother is a native of New Ireland with pronounced Melanesian features and the father is a European of Semitic origin, the daughter has a darker coloured skin with strongly curly hair and a pronounced Semitic nose. Again, the child from the marriage of a fair-haired Norwegian and a pale New Ireland woman is of pronounced European, almost Nordic features; the child has smooth, flaxen, lightly wavy hair and skin colour which has only a quite imperceptible tinge of yellow. The daughter of a Frenchman from southern France and a New Ireland mother could be regarded in all her features as an Italian from the Rome region.

Mixes between New Ireland women and Solomon Island men, natives from Buka or Bougainville, have shown the paternal features most sharply as a rule; similarly, children of New Britain women and Solomon Island men show the type of the latter. The son of a Buka islander and a woman from Nauru has the dark skin colour of the father and the smooth, bristly hair of the mother. Children whose mother was a woman from New Hanover and whose father was a native of Buka with clear intermixing from a paler race, show traits that in some are closer to that of the father, and in others closer to that of the mother; the male children have a more pronounced Solomon Island character than the female children.

The people of the smaller offshore islands and island groups on the eastern side (which are, as already mentioned, of earlier, volcanic origin), have founded colonies on the main island whose members even today differ in habits, customs and speech from their neighbours. Tanga and Aneri founded a colony on the eastern side of southern New Ireland many years ago, in present-day Siara, beginning about 8 nautical miles south of Cape Santa Maria and including a number of quite well-populated villages along a coastal strip of about 10 nautical miles. Both island groups still conduct an active, friendly trade with Siara, while standing more or less on a war footing with all their neighbours. Furthermore Tanga and Aneri form the bridge across which there is a steady connection for commerce and trade with the Nissan group, and thereby with Buka and the Solomon Islands generally. In this way traits of one population have passed to the other, 118in part to be taken up as an exact copy, and partly to be more or less modified, without, however, disowning their origin completely. I will return to this in the ethnographical description.

Similarly, Tabar and Lihir have founded colonies on the main island of New Ireland opposite, with which they are still in friendly-neighbour communication. About twenty years ago there was no such friendly relationship between these colonies. This has changed a lot since then; in particular labour recruitment, which has introduced the people of different districts to one another, has torn down the barriers restricting communication; thus through power of authority the vestiges of enmity have been removed by the administration.

The character of the people in the north and in the south is very different. In the south we find a great similarity to the inhabitants of the Gazelle Peninsula. The people there have the same closed, almost sullen character, tending only a little toward communicativeness. This is also demonstrated in the layout of the villages, which almost universally consist of separate, enclosed compounds, within which the inhabitants are not exposed to the peering gaze of their neighbours. They have a dislike of strangers and foreigners, and where occasion arises this is expressed in raids and attacks. Since the founding of the missions and, through the influence of the imperial administration, hostilities against whites have diminished significantly, and traders can settle down anywhere unmolested.

The population of northern New Ireland is considerably more lively, and has on the whole a higher intelligence than that of the southerners. Dancing and singing and extensive festivities with great feasting are the order of the day here, and work is pushed aside to the best of their ability. Nevertheless the northern New Ireland person is a sought-after worker in the plantations, since as a result of his greater intellect he grasps things easily and, after a brief introduction, understands the work he is to do. When he knows that he is being watched he works to the best of his ability, but when one’s back is turned he lays his hands in his lap and loafs about. On his own territory, circumstances permitting, he is quite importunate and insolent, when he knows that he can get away with it. However, he willingly submits to authority and after a short time becomes a useful subject. Since a human life is of not much value to him, in earlier years attacks on whites, and unfortunately murders, occurred quite frequently. However, since a police station has been set up in northern New Ireland this has stopped, and the earlier infamous coast today belongs among the safest regions of the archipelago. The natives have connected their villages by broad highways that are maintained in good order, they have bridged rivers and watercourses with solid bridges, and taken pride in carrying out the work carefully. From the northern point of New Ireland one can now undertake a journey of 200 kilometres along the east coast on good roads, equipped only with a stick and a little tobacco to give as reward to bearers or for well-performed courtesies. In northern New Ireland the missions still have no notable success to show, and only in the most recent times, after the imperial administration set up secure, ordered conditions, have individual stations begun to instruct the natives in Christianity.

Cannibalism was practised throughout New Ireland and New Hanover until not long ago. Through the influence of both the missions and the imperial administration this custom has been restricted at the present day to isolated parts. In the Rossel Mountains, for example, it is still flourishing, and in those areas where the European influence is felt it is often practised in secret.

As a rule it was the bodies of those slain in battle that were eaten by the opposing party, when they could get their hands on them. Yet not only in open warfare did one capture the highly prized roast meat, but rather more by cunning, sudden attacks. All who were slain were dragged away: men, women and children, both old and young. Often expeditions were undertaken to far distant regions to obtain human flesh. On such occasions several districts united for a communal raid. As a rule attacks took place at night, and they rubbed their bodies with black dye to disguise themselves. The captured corpses were removed as quickly as possible and taken to their destinations.

On the New Hanover coast years ago I surprised a number of such hunters, who were returning from a raid in four canoes, holding about fifty men. After a lively hunt we succeeded in cutting off one of the canoes from the shore; the crew sprang into the water with their weapons in order to reach the thick mangrove cover of the near shore, which they succeeded in doing. The captured canoe contained three corpses, two youths and a just-matured girl. All three had been killed by axe blows and pierced with spears; the lifeless bodies were tied fast to thick wooden stakes by lianas. I learned later that the canoes that escaped carried a similarly horrible cargo; sadly, we were not fortunate enough to chase the raiders from them. In the harbour about two hours distant we later met the remainder of the tribe that had been attacked, to whom we delivered the bodies.

Having arrived at their destination, the corpses are taken by the women with loud shrieks of joy, and preparation is begun immediately. This consists of first rubbing the body with sand at the beach and washing it. Butchery then takes place after the bodies have been laid out for several hours, and the neighbours have been summoned by drum signals to celebrate the tribe’s triumph and incidentally to pick up part of the roast. Chiefs have the right 119to reserve the best morsels for themselves, but must, however, give precedence to the host, and pay him in shell money for the portion offered. Everyone tries to get a small piece, for by partaking they believe that they will gain greater bravery or strength or cunning. Indeed, over the course of time, cannibalism becomes a passion for many natives. Certain members of a tribe as well as the corpses of those who have the same totem sign, are not eaten. How one determines this in the latter case, has still not been made clear to me, because membership of a totem is not made recognisable by outward features; yet it is an indisputable fact that these corpses are not eaten. In isolated cases prisoners are tortured to death, just as on the Gazelle Peninsula in earlier times. On the island of Lir, or Lihir, an act of cruelty is still prevalent which will hopefully soon belong to the past. Should the chief have a craving for human flesh, he assembles his entire tribe including the slaves who have been acquired during raids, having previously shared the name of the sacrificial victim with a number of his trusted friends. All sit down in a broad circle on the open ground of the village. At a signal from the chief the chosen few fall upon the victim, hold him fast and poke a hole in his body behind the collar bone. Small, glowing-hot stones are crammed into his body through this hole, and the unfortunate person is then released. He staggers about in appalling agony until death releases him. This horrible custom is said to have been common earlier in the greater part of New Ireland, and it is also known in the Duke of York group, but only through hearsay as a consequence of trade with the New Ireland coast opposite. On St John’s Island they are said to have scalded the still-living slaves in the hot springs there, a custom that several years ago appeared so abhorrent to a number of visiting natives from Nissan (Solomon Islands) that a serious skirmish almost broke out between them and their hosts. And yet the Nissan people are terrible anthropophagi also. Cannibalism and human torture do not always go together therefore, even though we have to acknowledge it for New Ireland and isolated parts of New Britain. In this connection I want to note that even though the consumption of human flesh is, or more correctly was, widespread among Melanesians, it cannot be said to be a universal practice. In many parts of New Britain we find the custom stigmatised as an atrocity which occurs only among the neighbours, who are despised as being on a lower level. Even in the Admiralty Islands, both among the Moánus and among the Matánkor, there are numerous individual tribes that abstain from the consumption of human flesh. It must indeed be a characteristic of humankind that one looks down on anthropophagi as on a lower, more degenerate and despicable level of the species. Nothing can appear more abhorrent to civilised people than cannibalism; however, if we observe that people look upon their cannibalistic neighbours with contempt, while they stand on the same level of development and share their views of right and wrong in all other things, we are forced to accept that even among the so-called savages there exists a feeling deep within their heart which shudders before these sorts of degenerate acts against their own people.

I want to mention here the behaviour of Melanesians towards murdered white people. In the course of many years here I have never been able to substantiate a case where slain whites were actually eaten by the Melanesians. The bodies of murder victims have certainly been dismembered from time to time and individual parts taken to remote districts, to some extent as evidence of the murder effected, yet nothing definite is known about consumption of these parts. It seems inconceivable that the cannibal who eats his own kind should spurn a white person. But remember the groundless superstitions of the Melanesian which, I believe, have also carried over into the consumption of human flesh where he expects a perfecting of himself from eating the body of the slain. It is therefore conceivable that he does not eat the body of a slain white person because in his opinion the spirit of the slain person would exert an influence over him that does not seem desirable. The late king Goroi in the Shortland Islands, on questioning and without guidance, gave me the same explanation, though with the not very flattering observation: ‘Spirit belong all white men, no good!’ Generally one receives the answer that the flesh of white people does not taste good! I regard this as an excuse behind which the crafty native hides his fear of the spirit of the slain. Corroboration of this comes from the fact that in some cases parts of the skeleton of slain whites are preserved by the natives because they ascribe special powers and characteristics to them. Thus the upper arm bone of a European slain at Kambaira on the Gazelle Peninsula was carried around in a little shoulder basket by a chief there, because he imagined that he was thereby procuring a part of the spiritual superiority of the murder victim.

The view that the presence of skulls or human jaw bones in a hut is a sure sign of the cannibalism of the inhabitant, is completely erroneous. In isolated incidences this is certainly the case; often, however, these skeletal parts are memorials to the dead: parents, relatives or friends, and have as little to do with cannibalism as the locks of hair that people in Europe keep as remembrances of the dead. As a consequence of this piety towards the dead, many a native has been the victim of ill-considered punitive expeditions, since the presence of these human remains has been regarded as proof beyond doubt of his guilt.120

Equally erroneous is the notion that cannibalism is the main factor in the great decline in population numbers. Certainly in many areas the population of particular districts has been sharply decimated by headhunting, but overall the loss of human life as a result of cannibalism is proportionally barely greater than the enormous losses brought about by wars in civilised countries. In many peoples of the South Seas we find a rapid decline in population, in spite of their not subscribing to cannibalism. To count up or to discuss the individual factors in detail would take too long. It appears, however, that all the South Sea tribes possess a certain weariness of life that robs them of the energy essential for living and this had resulted in a general decline of population long before the arrival of the whites.

Marriage is significantly different in individual parts of the island. We find in the south, as on the Gazelle Peninsula, the purchase of women by the family elders, who then hand over the purchased girl to the younger members of the tribe. On New Hanover and in northern New Ireland this custom is also present in places, but not to the same degree as in the south. Young women there lead a far freer and unrestricted life until they finally choose a husband. In very many places it is not the young man who makes the first step but the young woman, who via female intermediaries makes known to the man in question that she wishes to favour him with her choice. If the chosen one agrees, they live together henceforth as man and wife. Gifts are exchanged and a festive meal is put on. But marriages are concluded exclusively between two individuals who have different totem or tribal signs. Marriages never take place within a totem group, and sexual intercourse between members of the same totem group is regarded as incest, and is punished by death.

In the north, the marriage is not one of great stability. Both parties may freely separate, and the woman then goes back to her clan, and any children born during the marriage go with her. Also, wife exchange frequently takes place, but only between members of the same totem group. Because of this very loose relationship the tribe and the population suffer to an especially great extent, for the women regard children as an inconvenient appendage and use the most varied methods of aborting the embryo, partly mechanical such as strong kneading of the abdomen, leaping from a high block of stone or a tree trunk, strongly binding the abdomen, and so on, and partly through medication, as represented by various familiar plants. Through this bad habit the women weaken themselves in such a way that they die early and do not contribute to an increase of the tribe, so that the latter always decreases in number. It can be accepted as a certainty that the number of women is half the number of men, and during the period of my stay in the archipelago the population of these regions has declined rapidly. Further decimation is brought about by the custom of entire villages or groups occasionally undertaking to have no children at all. I know two previously quite heavily populated districts which, as a result of such an agreement, have almost completely died out today. The motive for this practice is certainly in part the inborn indolence of the natives. A large family creates more work and increased effort, therefore they avoid this by destroying the offspring. Other grounds also contribute, particularly the essence of the totem which often makes the selection of a husband or a wife very difficult, because a large group is not in a position to obtain the necessary wives from a smaller group that has only a small number of marriageable girls at its disposal. The forbidden sexual intercourse within one’s own sib then gains ground in secret, and with it the abortion of the foetus. Now if one considers that the girl has already yielded to sexual intercourse by the eleventh or twelfth year and undergone foetal abortion by all kinds of barbaric means, then it is clear that after continuous repetition of this procedure the body becomes weakened to such an extent that at an early age the woman is infertile anyway, and a later, true marriage will remain childless. Girls of sixteen or seventeen make no secret of the fact that they have brought about an abortion three or four times already. Still other customs, as yet unfamiliar to us, contribute as well. In one of the above-named districts female infertility was the result of a prohibition or a vow that had been most strictly implemented since the death of a chief known to me by name. Whether the dead man had imposed the prohibition before his death or whether the vow had been made in his honour after his death, I have never been able to clarify despite all my efforts. However, I tend towards the opinion that we are dealing here with one of those customs that are incomprehensible to us, but that occur here and there from time to time, and have the purpose of honouring a dead person. By way of example, years ago on the Gardner Islands after the death of an influential chief, the honouring consisted of the whole sib speaking not a word for months, and all sib members passed by one another as silent as a post. What it takes to comply with such an obligation can be judged only by those who know the merry, bright natives of that island; and to those who submit willingly to this obligation, adding a bar to marriage would not matter either, the more so since other supportive motives are contributing as well.

No order of the authorities can combat these customs, no threat and no admonition. Perhaps the Christian missions could bring about change, but the Christianity of the natives consists of outward appearance for the time being, the spirit of the 121people still clings to the past and is subject to old established practices.

Polygamy is universally permitted. From what has been said above, however, it is understandable that it is practised only in isolated cases. Married life is far from ideal; the wife is to a great extent the workhorse. For the most part she attends to the work in the garden, but still has much free time to relax, of which she also makes abundant use. Obedience to the spouse is a virtue that she does not know, or practises only to a limited extent, and marital discord is the order of the day. The lord and master, when finally his patience is exhausted, resorts to a stick or his fists and this results in the wife, if she can manage, rushing to her sib and enlisting the help of her relatives. Thus marital quarrels frequently lead to conflicts and bloody feuds of long duration.

The birth of the first child is always celebrated with great feasts. It is a curious practice that on this occasion mock battles occur between the men and the women. The former arm themselves with short, but quite solid sticks, the latter grab stones, clods of earth, hard fruit, and so on, and, apparently incensed, both parties fly at each other. After a short struggle in which quite effective blows can land, they separate amidst laughter and banter and sit down joyfully to the meal. Pigs must not be missing from these festivities on New Ireland. The greater the number of pigs and the bigger the specimens, the greater the renown earned by the host. At one feast in honour of a dead person in a village on the north-east coast, I counted thirty-seven pigs weighing 80 to 200 pounds; besides this, around 5,000 to 6,000 pounds of taro tubers were stacked next to them, about 300 bunches of bananas and a similar quantity of the round, cheese-shaped packets of sago. The feasting on such an occasion goes on for several days and the participants devour enormous quantities that would command the greatest astonishment from a European observer. An individual would, without apparent effort, devour portions of 4 to 5 pounds of pork, a similar amount of taro, several handfuls of banana and a number of sago cakes.

Special customs do not take place for the onset of puberty. The boy practises spear-throwing with his peers, and when he is bigger goes fishing with the older people. When he is big enough, he goes into battle with them. Girls stay with their mother, go with her to the garden, and are instructed in dancing at an early age. When they are bigger they enter into a love affair, secretly or openly, until they happen to get married and come under the hood. This is no metaphorical expression, since all married women, after their wedding put on a hood, gogo, made from pandanus leaves, which bears a distant resemblance to the old Prussian grenadier cap. This cap is always worn in the presence of men, and is taken off only when the woman knows that she is not observed. They are not very careful in the presence of boys and striplings, but etiquette requires that on the approach of an older, married man the gogo is immediately donned. This practice was introduced from New Hanover and has spread over a large part of northern New Ireland. In the wood carvings mentioned later, we find the female figures frequently wearing the gogo, a sign that that carving had been produced in honour of a dead wife.

With the exception of the gogo the woman does not bother very much with clothing. A bundle of fibrous material, sometimes in natural shade and sometimes dyed red, hangs front and back from a cord laid around the stomach. Young girls present themselves as God has created them, and likewise without exception the men go in Adamitic costume. In recent times both genders cover themselves with bright calico material; the men strut about in trousers, jacket and hat, and appear awkward in this civilised attire and often quite unclean. The unclothed brown figures of earlier times without doubt created a significantly more favourable impression on the foreign viewer.

The sight of these clothed men makes it quite clear to us that men’s clothing came originally from the endeavour to decorate themselves; since dressing for protection against the effects of weather is not necessary anywhere in the Bismarck Archipelago. That is why one occasionally sees an islander proudly wrapped in an old winter overcoat, a present from some settler for whom keeping this moth-eaten thing is not worth the effort. That the native does not feel comfortable in the foreign feathers can be observed on many occasions, but the quest for imitation and the thought of now appearing significantly more elegant, in short fashionable, causes him to make a sacrifice. In many cases, I regard dressing in European materials as directly unfavourable to health. A naked native gets washed by rain and feels no ill effects from it; the clothed native does not take off the clinging cotton materials, wet through from the rain; they dry on his body and cause lung problems, to which he is particularly susceptible. We should not regard the nakedness of the natives as a cause of the (probably to our eyes) immoral lifestyle. Nakedness, of itself, evokes no sensual arousal in a native, and the prudishness of a totally naked New Ireland girl is just as great if not greater than that of the majority of our fashionable European ladies. To the European, the native in Adam’s costume actually does not appear as naked; the brown skin in itself to some extent substitutes for a suit. I have frequently been able to observe how itinerant European women have, in a very short time, learnt to regard the appearance of a naked native as not offensive a sight, whereas a naked European would undoubtedly have aroused their disgust or their anger. Even for a white man who has lived for many years 122among the natives, a naked fellow countryman would not be a feast for the eyes; the native in the unclothed state appears less uncovered than a naked European who makes a helpless, angular and awkward impression when he sees himself deprived of his protective shell; he does not know whether he should go or stay, the whole freedom and ease of movement has become lost to him with the removal of his clothes, and he arouses a feeling of offence, whereas with the native the exact opposite is the case.

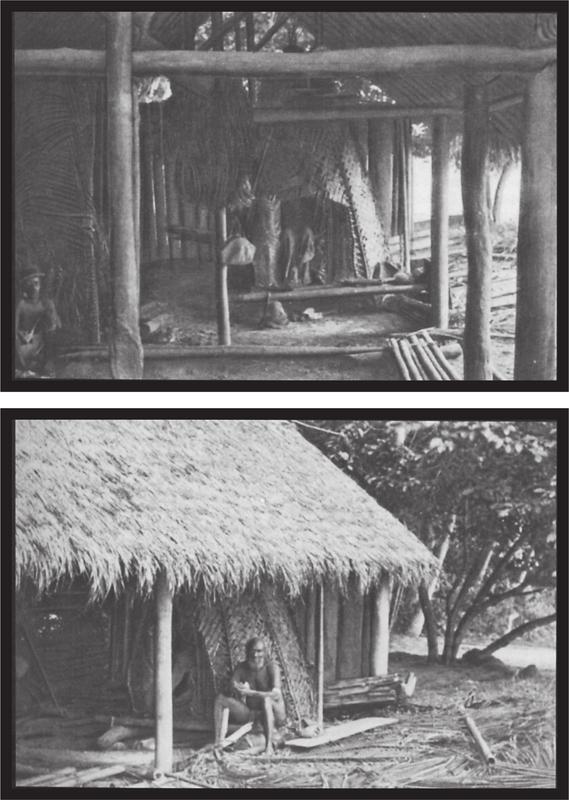

In places in southern New Ireland where, as on the Gazelle Peninsula, they practise marriage purchase, a peculiar practice predominates which has often been regarded as a traveller’s tale, but which is, however, based on fact: namely the temporary barricading of the young girl before marriage. Inside a tightly enclosed hut they erect a smaller chamber made from several light poles covered with coconut matting (plate 18). The young girl settles down inside, and for a long time is seen only by the parents, who feed her very well with choice food, and escort her outside in the evening to answer the call of nature. According to comment by the natives, this seclusion lasts from twelve to twenty months. During this period the young woman attains a noticeable girth, and her skin is markedly bleached, so that after a basic wash one might imagine that one is confronted by a somewhat dark Samoan woman. Both the plump shape and the pallor of the skin are regarded as special marks of beauty. A fattened beauty of this kind came to my notice only once; she had been released from imprisonment just two days previously and been given a basic wash, which may well have been very necessary, since during the enclosure washing is regarded as unnecessary. She was apparently subjected to a public exhibition, for many people sat round about, marvelling; and I too was fetched specially in order to express my admiration.

The fattening had proceeded well in this case. The little one, who might have been about fourteen years old was in reality as ‘fat as a pig’, and the women sitting nearby caressed the fat arms and thighs with admiration or patted the thick cheeks in delight.

Burial customs in northern New Ireland have many peculiarities. When somebody dies, a bier is made out of spears, the decorated corpse is laid on it and then carried from house to house by the relatives. All those present begin a loud weeping and wailing: men as well as women and children. Relatives elsewhere are summoned immediately, and assemble in the house of mourning; friends and acquaintances of the dead person also hasten along.

On the second day a catafalque resting on four stakes is erected in front of the house and the corpse is laid on it. The greater the status of the dead person, or the greater the influence he had had, the higher are the posts of the structure, yet seldom more than 2 metres high. A wood funeral pyre is now set up beneath the structure. It consists of the usual wooden billets but also of carvings that have been used in earlier funerals; in recent times they also break up boxes and crates brought by workers and add the wood to the pyre. The carefully arranged wood pile is then set alight and at the same time a close male relative climbs onto the catafalque, holding a spear in his hand. From time to time he touches the head of the corpse with the spear while singing a monotonous song; this continues until the flames of the funeral pyre necessitate his leaving the structure. The fuel for the fire is constantly replenished until finally the flames have destroyed the structure and the corpse topples onto the glowing embers. The same man who had earlier stood on the structure now steps forward and removes the liver from the corpse with his spear; he shares it out in small pieces among the young men present, together with ginger root. After this ceremony more fuel is thrown onto the fire until the corpse is completely burnt to ashes, and when the embers have gone out a simple protective roof is erected over the site.

During the cremation there sounds a steady, deafening wail of grief, voiced by all present. After the cremation an opulent feast is partaken. That for the relatives is set up beside the funeral pyre; a similarly rich meal is prepared for the friends and acquaintances of the dead man, a short distance away.

Several weeks later the ashes at the cremation site are mixed with coconut milk, and the mourners smear themselves from head to foot with the paste. On this occasion a feast is set up again for all those assembled. For the present the funeral rites are at an end until they reach their conclusion with the annual malengene.

The actual mourning lasts from the day of death until the day on which the mourners sprinkle themselves with the ash (karong) of the funeral pyre. During the period of mourning the men are not permitted to rub powdered lime or lime paste into their hair.

On New Hanover the funeral procedure is similar; unfortunately, however, I have never had the opportunity of being present at a burial. If we go along the east coast of New Ireland the funeral customs gradually change as we go further south. Cremation is retained but the preceding ceremonies are different. For example, at several places the corpse lies in state in a hut, sitting in a small canoe; the whole body is sprinkled with a mixture of red ochre and burnt lime, and the hands of the corpse, in a sitting position on the bier, are pulled into the air by thin cords tied to both thumbs, so that the arms rise up with elbows bent and hands raised, as if in a position of supplication. In this position the corpse is then buried, or cremated on a funeral pyre. 123

Plate 18 The house in which a young girl is incarcerated before marriage

Above: The small hut where the girl spends her time is visible in the background

Below: Side wall of the hut removed

In some areas the prevailing practice at cremation is the setting up of a figure to represent the deceased. The figure is life-sized and plaited from a certain liana, or more accurately the body, fashioned from foliage and grass, is plaited over with a thick liana. The face is represented by a wooden mask. These figures are displayed on a scaffolding during the mourning period and are, as a rule, burnt with the corpse at the conclusion of mourning.

In certain districts in the Rossel Mountains they have a quite characteristic burial or, more correctly, preparation of the body, although one which I have never had the opportunity to see personally, but which has been reported to me by one of the Methodist missionaries stationed there. The corpse is first placed in a sitting position, then it is not only rubbed with coral lime but is packed, in the true sense of the word, in powdered lime and the whole thing is then tied up in leaves. This bundle is placed on the cross beams under the hut roof and stored. My informant, Mr Pierson, tells me that he has seen such bundles that were only a few days old yet spread no cadaverous smell; he had seen them in multiples in 124the huts of the natives, among them some which had apparently already been stored for a number of years and were coated with a thick crust of dust and soot.

Often, however, the dead are interred in the normal way, although in the districts where this is practised, they bury bodies at sea as well. The choice of burial method is not left to the discretion of the bereaved; however, I have been unsuccessful in obtaining exact information on the nature and manner of regulating this decision. This much is sure: that certain people are buried exclusively at sea after their death, while others are buried in the ground. In any case the former method is the more fashionable, as it appears to be the privilege of chiefs; however, it is possible that totem customs are taken into account here, since the children of those women who have been buried in the ground after death, are interred in the same way, even when the husband and father had been buried at sea. Yet this is not an irreversible rule, for upon questioning, natives declared that after their death they would be buried as their fathers were. Perhaps we are dealing here, as is so often the case, with customs that have been introduced from other regions and been reserved by the immigrant generations, while being partially adopted by the original population and combined with previously existing customs, or modified by them. Doubt over the burial method does not exist and, at my instigation, those in the villages who would have their graves in the sea and those who would have theirs in the ground arranged themselves into two distinct groups without further ado.

In general, when I had the opportunity to observe interments of various kinds, the corpses were decorated with bunches of feathers and items of adornment, and in many places they were provided with shell money or weapons, betel nuts and eating utensils, as on the Gazelle Peninsula.

Dancing and singing are not fostered on any island in the archipelago as much as by the people of New Ireland, probably because the daily work leaves extensive free time for this pleasure. Nowhere else in the archipelago do we find such a variety of dances with such varied figures. Here too the dances are mimic presentations, and each individual movement is precisely deliberated and rehearsed, so that, in precision of movement, a group of experienced dancers could confidently be a match for a European ballet. To describe the individual dances in detail would be far too broad a task; it may suffice to introduce several of the main dances, which are divided into different groups. Dance presentations that I have witnessed can be divided into erotic dances, war and battle dances, pantomime representations of certain events, and dances that are dedicated to the totem or the tribal emblem. This division is valid only for the men’s dances; in spite of all my efforts I have not been able to place the women’s dances into a precise system.

Erotic dances are very popular, and are presented mainly at festivities to honour the dead. On this occasion the dancers wear the tatanua masks mentioned elsewhere (Section VIII), which make the wearer unrecognisable. Besides the mask the dancer wears a cloth of fern and other foliage round the waist, extending from the girdle to the knees. At the presentation the spectators form a circle within which the orchestra takes its place. The latter consists of wooden drums and boards and pieces of bamboo, which are beaten in rhythm. The band is supported by a choir which puts as much effort as possible into drowning out the droning drums. First the orchestra plays a kind of overture. Then from the side, usually from out of the bush, one sees a number of masked dancers approaching; slow, deliberate steps bring them closer to the dance place, now stopping, now looking about on every side, before finally uniting as a group at the predetermined spot. The group then presents, with orchestral accompaniment, a number of measured movements that can hardly be called a dance, since they consist of the masked people slowly circling one another as if one wants to ferret out who the other might be. This lasts for about ten minutes. Then suddenly there approaches, likewise from out of the bush, a single masked figure who moves toward the group in the manner previously described. As soon as the masks perceive this new mask, they apparently fly into great excitement, trot towards it with rapid steps, then draw back, while the newly arrived mask gradually closes with the group. Then begins a very comical presentation which depicts the approach of a man towards a woman, since it quickly becomes clear to the spectators that the recently arrived mask is a female, while the first masks represent men. The men now seek to make the woman receptive, by each endeavouring to supplant the others. Meanwhile the beautiful one remains apparently cold towards all love-suits, pushing one of the flatterers back firmly, turning her back on another, or demonstrating her displeasure through other unmistakable signs. But finally she declares that she has been conquered, and acknowledges one of the masked men as her lover. The latter is now full of joy, which he expresses by all manner of leaps around the beloved. The rejected suitors now withdraw to one side of the dance place, and hand the stage over to the two lovers who now portray an intimate approach, not without initial resistance from the beautiful one, who finally lends an ear to the declarations of love from her chosen one. Even though the representation does not lack earthy realism, especially in the final scene, it cannot be said that the dance is obscene. The comic and the grotesque are predominant 125in the production, and are even further elevated by the carved and painted tatuana masks with their dyed crests, which call to mind the old Bavarian helmets. I need not comment that the natives find nothing disgusting; old and young, men and women, boys as well as girls, gaze on the hustle and bustle quite calmly, and at the end acknowledge their appreciation to the participants with loud shouts.

Even though the native maintains a certain decency in the large, public gatherings, there are other dances in which he recognises absolutely no limits. However, these sorts of presentation take place on fenced-off, densely enclosed places where the gaze of the curious, to whom attendance at such dances is not permitted, cannot penetrate. These types of dances are not suitable for a detailed description.

War and battle dances are presented with the same musical accompaniment as the dances previously described. The dancers take care of the singing themselves. They assemble in a double row or in several rows, each man holding an ordinary battle spear in his hand. The whole body is in ceaseless movement from beginning to end of the dance; legs and feet make rapid trotting movements or bend at the knee, they are thrown to right and left, forwards and backwards, the arms flourish the spear, make feigned thrusts that stretch the enemy on the ground in pantomime, after which the spear is withdrawn with a solid tug. Meanwhile the head and trunk bend and sway in all directions, yet each movement is studied so precisely that even when a hundred dancers are performing the various complicated movements simultaneously, rapidly following one another, all perform in unison. The turns and figures of these dances vary to the greatest extent because first one then another finds a new figure, and when this finds appreciation it is practised by the dancers and is presented perfectly on the next occasion.

The pantomime dances that represent a particular event are equally abundant. They do not differ significantly from similar presentations on the Gazelle Peninsula; it may be that the northern New Ireland people are more outgoing in humour than the calmer, more self-contained Gazelle inhabitants, and accentuate the comical moments more in their dances.

Those dances that for want of a better description are called totem dances, are extremely characteristic. Here they portray the movements of that particular animal which serves a particular group as a tribal designation. In northern New Ireland, certain birds serve as totem signs. The performers are always the owners of the totem sign in question. Here is demonstrated what an acute observer the native is, how minutely he knows his totem bird and its habits, and can imitate them. By way of example I want to introduce the dance of the rhinoceros bird people, whose totem is the rhinoceros bird (Rhytidoceros plicatus Forst.). The dancers arrange themselves in pairs one behind the other in long rows. Each person holds a carved, painted rhinoceros bird’s head in his mouth; hands are mostly folded behind the back. The rhinoceros bird is recognised as a very shy fellow that feeds in great tranquillity on suitable fruits in the treetops, while never dropping his guard, continually turning his head in all directions to reassure himself that no enemy is in the vicinity. Should one appear, he lets out a characteristic cry and flies off loudly beating his wings. All of this is given a very realistic interpretation by the dancers. Their heads turn to right and left, forwards and backwards; one eye is half closed, the other glances sharply in a particular direction; each movement is performed unhurriedly, in circumspect calm, just as the real bird does it. Finally the cry is sounded and the noisy wing-beats imitated.

In another dance of this sort the pigeon is represented as the totem bird, and is pursued by the snake; that is, the evil spirit that is the totem’s enemy. The dancers arrange themselves in two long rows, one behind the other; the front pair represent two pigeons. First a communal dance is performed; then gradually the front pair assume a leading role, dancing individually or as a pair along the line of the other dancers until reaching the far end, then returning to the front. These movements represent the hopping of the pigeon from branch to branch in the treetops. Meanwhile the other dancers form a peculiar figure that represents the snake. This is done as follows. The back pair of dancers step back a little; one steps in front of the other; the one behind bends his left leg forwards somewhat and his right leg sideways; the second dancer then sits on the bent left leg of the first dancer, in turn placing both his legs in the same position; the other dancers gradually close up in the same way as this pair, so that there was finally a long line in which each dancer sat on the knee of the dancer behind. This line, awkward in its combined movement, represents the snake, which tries to encircle the pair of pigeons, which are meanwhile performing a lively dance. From time to time, when the snake’s intention is noticed the pigeons fly off; that is, both dancers immediately separate, and then reunite for a combined dance. This goes on until all the dancers, especially those representing the snake are totally exhausted, since in the position described each dancer has to use his utmost strength to follow the combined movements without the connection being broken. This figure is seen in other dance productions as well, and then it has different meanings; in one instance it represents seagulls which alight on a floating tree trunk. The corresponding head and arm movements are different in this case.126

Women’s dances are of course different as well, but no pantomime presentations are found here; rather, the dancers endeavour to give expression to the daintiness and grace of the female body through strongly measured movements. The series of dancers, arranged in pairs, strike up a song in the highest soprano register. Their bodies are tastefully decorated, particularly with flowers and bright leaves, and each dancer holds a pretty, bright posy of flowers in her hands. Graceful and often very complicated movements are performed with hands and feet, and when such a dance is carried out by a number of young girls, it is actually a beautiful sight. The slender brown figures, in the adornment of youth, turn very gracefully in slow movements, take small steps forwards or backwards, treading as carefully and lightly as though they were treading on eggs, bend their hips, raise and lower their hands and arms, and now and then cast their gaze on the spectators as if asking: see how attractive I am? All obscenity is strenuously avoided.

After what has been said, it is obvious that these dances require lengthy practice. In the event, a lot of time is spent on practice and both boys and girls are instructed by their elders from early childhood. The mothers watch very proudly and happily as their barely two-year-old daughters attempt to imitate the movements of the dancers with greater or lesser skill.

The singing that accompanies the dance is provided in part by the dancers themselves and in part by the drummers, and is a continuous repetition of certain phrases which apparently have no connection with the dance and seem nonsense to a European listener. Incidentally, what I have said in discussing the songs of the Admiralty Islanders (Section IV) is valid for this part of the archipelago as well. While the songs sound nonsensical to an uninitiated person, they are understandable to the natives. They express the highpoints in a concise form by certain key words, whereby the full significance of the song becomes clear.

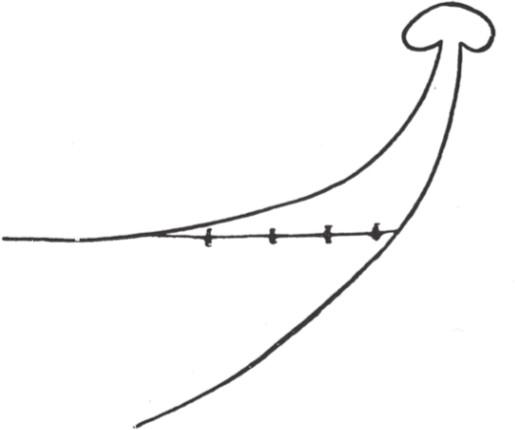

Fig. 43 Musical instrument from New Ireland

A part of the musical instruments has already been named in the preceding paragraph. Here too, the drum is a hollowed-out tree trunk with a narrow slit as a sound-hole; the widely audible tone is produced by hitting the side wall with a stick. The hour-glass-shaped striking drum so widespread on the island of New Britain was unknown anywhere on New Ireland until a few years ago. Recently, returning islanders who had been in the service of settlers in New Guinea and on the Gazelle Peninsula brought the instrument to their homeland, and it is now found here and there. Whoever is familiar with the decoration and shape of these drums can establish without difficulty whether a certain specimen has been imported from the Gazelle Peninsula or from Kaiser Wilhelmsland. A signal language as on the Gazelle Peninsula exists only in southern New Ireland, not in the north nor on New Hanover.

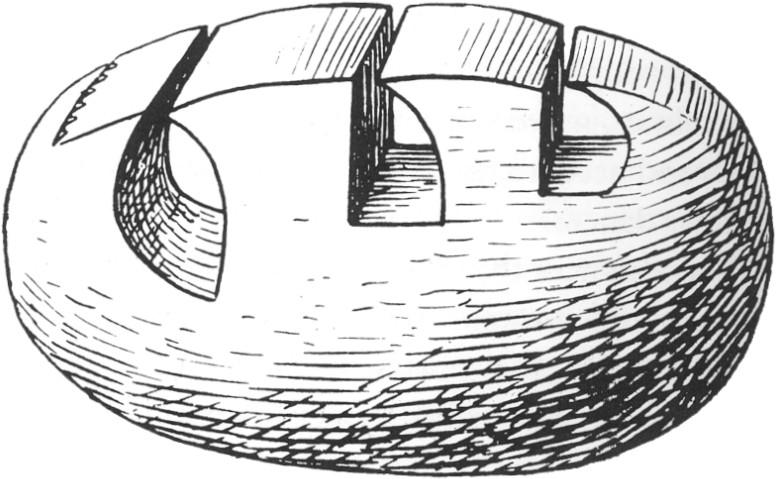

Very characteristic and typical of northern New Ireland, is the instrument depicted in figure 43, which must be ranked among the stringed instruments, although it bears not the remotest similarity to European instruments of this type. It consists of a wooden block 35 to 45 centimetres long, 20 to 25 centimetres wide and 13 to 17 centimetres thick. The upper side is formed into three separate tongues by narrow slits. Both central tongues are about 7 to 10 centimetres square and slightly convex. To use it, the native holds the instrument between his knees and strokes across the convex side of the wood with the flat of both hands, which have been previously lightly rubbed with the resin of the breadfruit tree.

The tone arising, or more accurately the three tones arising, bear a great similarity to the bray of a donkey. This characteristic instrument is called nunut by the natives, and the tone that it produces is regarded by the uninitiated as spirit voices.

A very widespread instrument, but especially common in northern New Ireland, is the pan flute, assembled from five to eight pipes about 5 to 6 millimetres in diameter, fixed side by side and gradually shortening. The instrument is not used with the dances; it is used by both young and old to establish their musical genius.

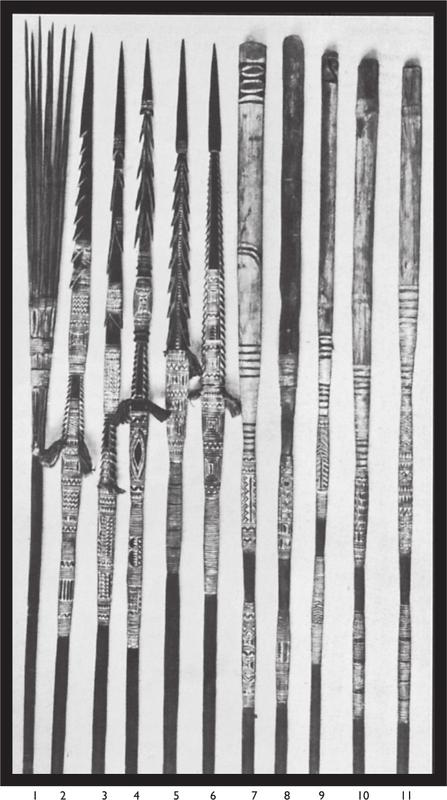

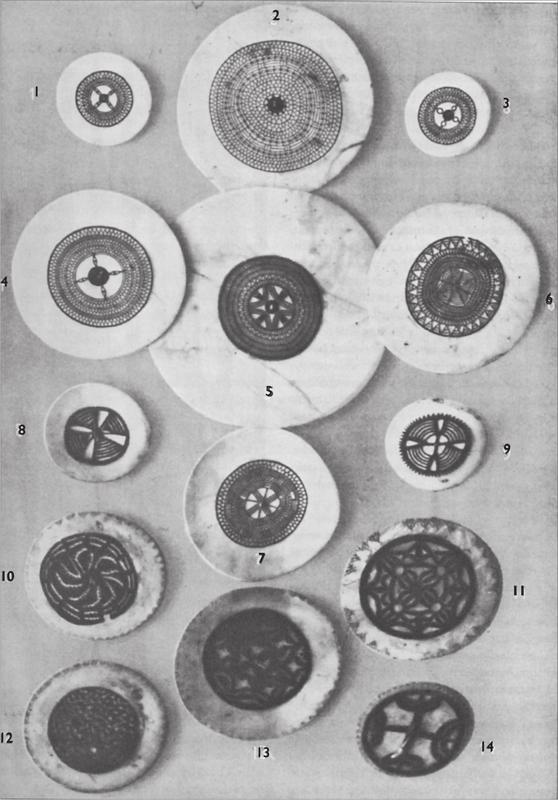

The weapons of the New Ireland people are not significantly different from those of the other inhabitants of the archipelago, and consist of clubs, spears, and slingshots with slingshot stones. Spears and slingshots are by far the most customary. Since the introduction of iron, the club has been joined by the axe as a weapon for close combat and, like everywhere else, has been provided with a very long handle when a weapon, as on the Gazelle Peninsula. The free handle end is more or less transformed into a broad, decorated blade. Firearms are very popular, but since the declaration of the German protectorate, providing them to the natives is forbidden. Very many of the earlier attacks and slayings of white people were caused by efforts to get hold of firearms, partly in order to act against the punitive sorties of the administration better 127armed, but mainly to wrest any advantage from the less favourably placed neighbouring tribes by having superior weapons. On none of the islands of the archipelago have so many successful attacks on whites been recorded as on New Ireland, and from time to time it has taken great effort to bring the disturbers of the peace to order or to administer exemplary punishment. Today this situation is disappearing; the establishment of police stations and the development of a network of roads have broken the previously warlike, rapacious spirit. White visitors can now wander undisturbed from village to village on good roads, greeted in a friendly manner by young and old.

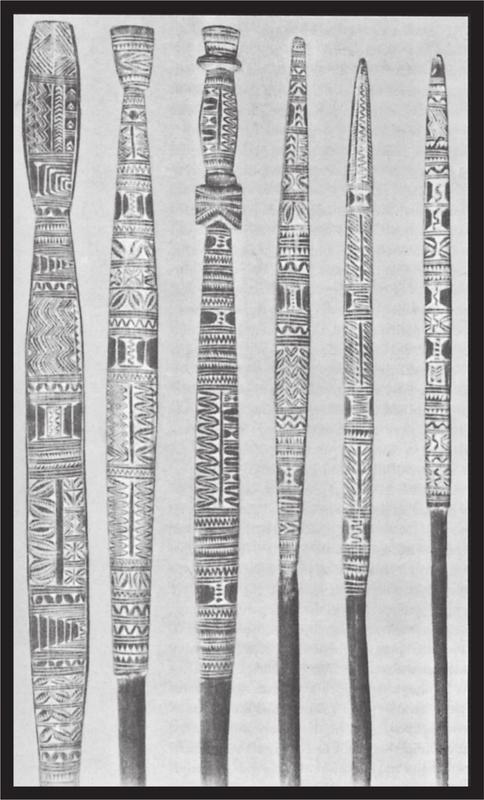

The club has spread from New Hanover to Cape George. In New Hanover two forms in particular are encountered: a round and a flat form; their length is from 80 to 130 centimetres. The round form has a diameter of about 4 centimetres at the striking end, while the flat form is about 7 centimetres broad at the striking end, tapered off to both sides. Both forms are decorated with carved and notched ornaments, very similar to the ornamentation of the spears. I will discuss in detail the significance of the ornamentation when I talk about the spears. The New Hanover clubs have spread as far as New Ireland, and occasionally they are found southwards as far as the coast opposite the Gardner Islands. In the southern half of New Ireland quite different forms occur, similar to the clubs of the Gazelle Peninsula. For example, we find the forms illustrated in figures 1 and 8 on plate 8 at Cape Strauch, and it is not improbable that they were introduced to the Gazelle Peninsula from there; the form in figure 10 is predominant in southern New Ireland, and was evidently transplanted from there to the Gazelle Peninsula. Then again, in the Rossel Mountains we meet another club, similar to the New Hanover flat form, whose extreme striking end is decorated with a characteristic eye ornament. According to comments from the older people, this represents the face of a spirit that gives strength and courage to the wielder of the weapon. In the villages inland from Cape Giori I was impressed by flat clubs with a characteristic form; they had no pronounced striking end, but both ends were expanded into a broad, fan-like blade, and in order to hold it in their hand they had to grasp it by the thin mid-section about 4 centimetres in diameter. This implement was difficult to use as a weapon and according to reports given to me it was used in dancing. For years I have tried in vain to get hold of these types of implements; however, like so many other things, they seem to be no longer used today. Indeed clubs were never used very much anyway, and today we would find more specimens in European museums than on the whole of New Ireland and New Hanover.

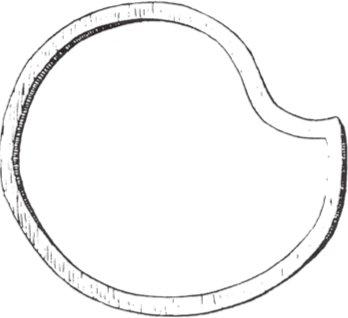

Slingshots and stones are still used everywhere in the southern half of New Ireland and also on the offshore islands. However, they had a far greater spread in earlier times, since during road construction in areas near the northern end of New Ireland, numerous carefully worked slingshot stones have been found, different in shape from the missiles that are still used in the south. During his voyage along the east coast of New Ireland, Dampier found slingshots in an area where they no longer exist today, which he named Slinger’s Bay. The slingshot stones found are on average 5 centimetres long and 2.5 centimetres in diameter at their thickest part. The ends are tapered. Because of a lack of suitably shaped gravel, they worked a dense, almost crystalline coral stone into slingshot stones. In the south, stream beds and beach yield satisfactory, readily available material in the form of rounded stones, and these are used just as nature provided them, as is also the case on New Britain. The slingshot appears never to have been used on New Hanover.

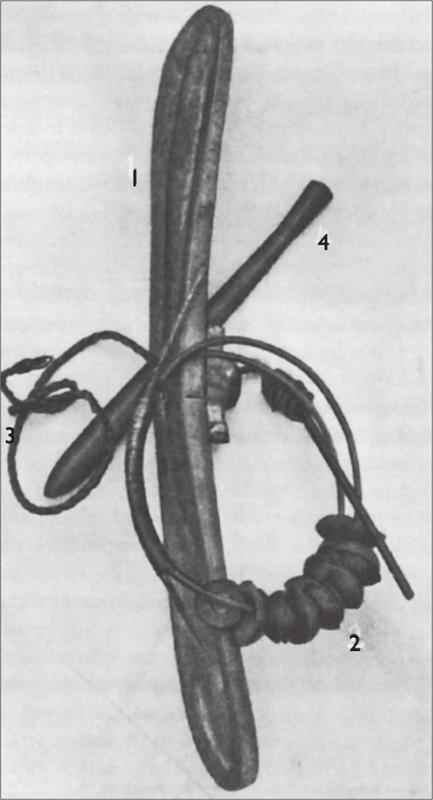

Fig. 44 Ornamented part of a spear from New Hanover

Of far greater significance is the spear, both on New Hanover and New Ireland. From New Hanover two different forms of spear seem to have spread to the north of New Ireland, as well as to Sandwich Island. Both forms are the same in that they consist of two particular parts – a bamboo shaft and a spear blade or spear point of hard palm wood, which is tied firmly to the shaft by careful wrapping with fine, strong fibre. The most widespread form has a circular cross-section gradually tapering to a long, needle-sharp point. The second form has a flat, lancet-like, more expanded point; in older examples from New Hanover this frequently follows an intermediate section (between point and shaft), decorated with incised hooks and ornaments. This form often has no shaft end of bamboo and is frequently made from a single piece of wood. The fissures in the carved decoration, as well as the inside of the hooks, are as a rule filled with red ochre or burnt lime, so that the dark pattern of the carving is clearly enhanced (fig. 44). These spears are now a great rarity.

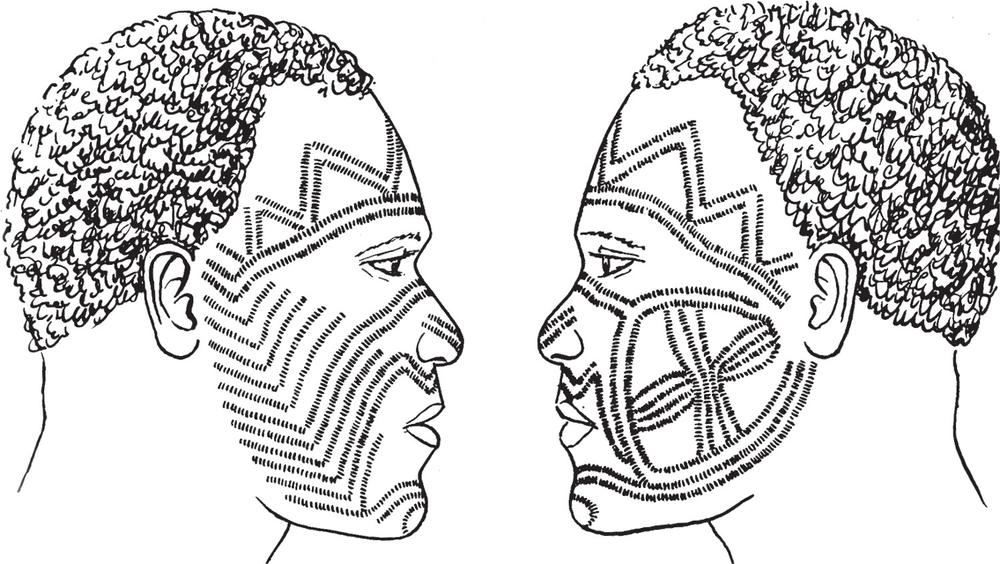

On the shafts there is almost always ornamentation, always of the same type. Professor von Luschan in his book Beiträge zur Völkerkunde has given a number of good illustrations of the unrolled decoration (plates 36 and 37), and is of the opinion that this is a case of the remnants of a stylised human figure. The natives admittedly have other ideas. Of course the majority have nothing to say about it. The sum total knowledge is: it belongs like that! or: it has always been made like that! However, several older men from New Hanover have advised me that the figure represents a snake or, more accurately, a spirit in the form of a snake, news that was apparently just as unfamiliar to the younger people sitting round as it was to me. On New Hanover the snake plays a major role as an 128evil spirit, just as on New Ireland, where we see it depicted in various ways as the enemy of the totem animal on the familiar carvings. As mentioned earlier we find the same stylised decoration on the clubs and, as on the spear shafts, in such a barely recognisable form that one can hardly talk about any interpretation. However, in my possession is a very old, carefully carved club with a flat striking end, one side of which is adorned with a figure in surface relief that is fairly clearly recognisable as the form of a snake. The fissures are filled with burnt lime and the decoration stands out clearly, as depicted in figure 45, as a dark carving on a white background.

Fig. 45 Decoration of a club from New Ireland

On clubs of recent date the ornamentation is just as carelessly presented as on the spear shafts; however, one can almost always recognise a head, which is depicted in the same style as the heads and faces in von Luschan’s reproductions. In recent years enterprising natives have resorted to manufacturing clubs for trade. These are recognisable by their enormous weight and their decoration with triangular notches in varying order, with the old, original, stylised decoration still recognisable even though it has attained a completely different character through altered technique.

Further to the south is found another type of spear, which can certainly be regarded as the original form for this area, until partially supplanted by the New Hanover spear. It is seldom more than 130 centimetres long, about 1.2 centimetres in diameter at its thickest point, and made from a single piece of wood. The point is about 30 centimetres long and sharpened; below this, at the thickest part of the spear, there is a wrapping of fine fibres, about 4 centimetres wide, and, as a rule, coated with lime. The shaft slowly tapers right up to the butt where it is about 6 millimetres thick, and is partially decorated by incised notches and longitudinal lines. This light spear is a very dangerous weapon in the hands of the natives; a high level of throwing ability is attained through repetitious practice, and I have seen life-threatening wounds imparted over 40 metres. Because of the lightness of this spear, it is possible for the natives to carry a large number of them, usually a bundle of ten to fifteen, whereas only two or three of the previously mentioned heavier spears could be carried, with the warrior running the risk of becoming unarmed after a short battle.