VI

The German Solomon Islands, together with Nissan and the Carteret Islands

Both of the northernmost islands of the Solomon group belong in the German region. The larger of these is Bougainville, to the north of which lies the much smaller island of Buka. Still further northwards lie the two small isolated groups of Nissan (Sir Charles Hardy Islands) and the Carteret Islands, which I include here because they are inhabited by Solomon Islanders.

Bougainville’s principal axis stretches from south-south-east to north-north-west. The southernmost tip of the island, Moila Point, lies approximately 6º53’S, and the northernmost point, King Albert Strait is about 5º24’S. A straight line between those points would measure roughly 266 kilometres. The average breadth is not more than 60 kilometres. The surface area of the entire island, together with the smaller offshore islands, is approximately 10,000 square kilometres, about the size of the grand-duchies of Oldenburg and Saxen-Weimar combined.

Although the coastline may be described as familiar, the interior remains as good as closed-off to us. Years ago I made a two-day excursion into the interior from Ernst-Gunther-Hafen (Mitteilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft in Hamburg, 1887–1888, vol. III) without noteworthy result. Traders from the Shortland Islands have made short trips from the south coast to the villages inland but similarly without real success. Recently the Catholic Marist mission has settled on the east coast of Bougainville not far from Toboroi, and has already attempted to make inroads into the interior. We can hope to obtain interesting information from this source quite soon. I need to mention here that the route into Bougainville of about 20 kilometres sketched out on a map by Herr Hugo Zoller, in his book Deutsche Neuguinea is a fantasy. The journey undertaken by him, in which I too took part, did not extend 1 kilometre inland.

During the night of 24 to 25 August 1767, the English navigator Carteret sighted the Carteret and the Nissan groups. Then early on the morning of the 25th, he observed the island of Buka, which he named Winchelsea Island. We owe to the Frenchman Bougainville the discovery of the large island named after him.

Bougainville mentions the high mountains that traverse the island from north to south; however, he gave no accurate report on their height, because the mountain peaks were covered in cloud. Only in 1875 did the expedition on the German warship Gazelle, under the command of Herr von Schleinitz, give more detailed information about this gigantic massif, which belongs among the highest in the South Seas.

From whichever direction you approach the island, from far off you can see the mighty mountain peaks rising above the horizon. As you approach the island you can easily distinguish the northern Emperor Range with the 3,100 metre high Mount Balbi, from the southern, somewhat lower, Crown Prince Range.

The Emperor Range occupies the whole northern half of the island; on the western side it approaches the shore, and from the region of Fois onwards small coastal flats appear only intermittently. The mountains rise rapidly to significant heights, transected by deep valleys that form clefts in the mountain in every direction. Over the steep mountain slopes, covered right up to the peaks with a rich, evergreen vegetation, waterfalls leap into the depths, several of them over 100 metres high, rising from the sea like shining silver strips between the dark green of the mountain walls. On the eastern side the Emperor Range falls away less steeply; here it forms many gently rising mountain slopes with steep cross-valleys and numerous streams. Along the shore there is a narrow plain, scarcely 2 kilometres wide in places, although at other places (for example, from Nehuss Point south to about Cape le Cras) it is 5 to 10 kilometres wide. Also falling gently away is the northern margin of the Emperor Range, which sends out a high, steep projection right to the shore only at Banniu, while forming splendid, gently rising slopes east and west of there. Such gently rising slopes are noticeable especially east of the grass-covered Cape Banniu, continuing to beyond the totally flat Cape l’Averdie. 200

Fig. 76 Banniu harbour. North coast of Bougainville

From the high Mount Balbi the Emperor Range sinks rapidly west to Cape Moltke and then runs southwards constantly flattening, apparently separated by a deep valley from the Crown Prince Range, the high northern spurs of which push themselves like coulisses in front of the flat southern spurs of the Emperor Range.

The Crown Prince Range, although not as high as the Emperor Range – the highest point is approximately 2,360 metres – with its multiple clefts, its numerous peaks and serrations and its bare, smoking volcanic cones, offers a far more interesting view than the Emperor Range. It stretches like a crescent moon, one horn turned to the north, the other to the east. In the centre of the crescent is the approximately 1,285-metre-tall volcano, Guinot.

The northern slopes of the Crown Prince Range to the Bay of Arava [sic], as well as the entire western and southern slopes from Empress Augusta Bay in the west, to Cape Friendship in the south-east, and north of the latter, are eminently suitable for establishing tropical plantations. This also applies to the abovementioned slopes of the Emperor Range, and one could say without exaggeration that on the island of Bougainville are to be found such extensive, fertile stretches of land as on none of the islands of the Bismarck Archipelago; at best, in this regard Kaiser Wilhelmsland is superior to the island of Bougainville. However, the latter offers advantages which are not available in Kaiser Wilhelmsland, namely the relative ease of accessibility of the coast, which not only provides good anchorages everywhere, but also has a number of splendid harbours protected in all directions from wind.

With the exception of the Marists nobody has attempted to settle permanently on Bougainville. Hopefully it will not be too long before we see the thick forests of the island making way for the light, flourishing plantations. At the end of 1905 the imperial administration established a police station on the eastern side of Bougainville, opposite the Martin Islands.

To get to know the coasts of the island better I want to make a round journey with the reader, setting out from the southern tip of the island, Moila Point (incorrectly named Komaileai Point on the maps). The entire southern end of the island is a plain, then the ground gradually ascends to the gently rising foothills of the Crown Prince Range. Out of the coastal plain rise several small isolated cones, apparently extinct volcanoes. Above the treetops a plume of smoke rises here and there, a sign that natives have their villages and gardens there. About 40 kilometres inland soars the highest point of the Crown Prince Range where it turns eastward. About 22 kilometres east of Moila Point there opens before us the approximately 10‑kilometre-deep culde-sac, Tonolaihafen. The shores of the harbour, particularly the eastern one, which seem to consist of a raised coral reef, are fairly high and enclosed by a wreath of mangroves, above which we see the broad tops of the virgin forest rising a short distance inland. Along the beach run coral reefs which seem here and there to make an end to further advance; but deep blue passes always open between them, and we are able to proceed right into the inner corner of the harbour, where ships find good anchorage in shallower water. We are now surrounded on all sides by high forested shores and could scarcely find a better harbour, for the high shores would also keep off the most severe storms. We see no settlement anywhere; the nearest natives live several kilometres inland and come to the harbour only occasionally to fish. In our mind we see the beautiful harbour occupied by numerous ships which from the storehouses erected on shore are taking on cargoes of all kinds of tropical items, produced on the German plantations stretching inland. Close at hand, however, we hear not the roar of mighty steamers but only the flapping wings of numerous rhinoceros birds which, startled by our visit, fly over the mirrorlike water; we hear not the cries of industrious, working men but the loud call of the flocks of pigeons which still live in the tops of the forest giants, undisturbed.

About 13 kilometres north of the entrance into Tonolaihafen lies Cape Friendship. The entire stretch of coast is rocky and steep; the sea crashes and foams against the coral rocks and in the work of many thousands of years it has wrought them into fantastic grottoes and chasms. A little north of Cape Friendship a bare, steep, rocky island named Rautan not far from shore, lies surrounded by coral reefs. A narrow, yet navigable channel passes between it and the main island. Sailing ships need to be particularly watchful here, for a strong current runs through the narrow strait, and during unfavourable wind and weather conditions it can prove disastrous.

With the narrow pass behind us we observe a flat, sandy coast which stretches to the north‑north‑west. 201Far out, about 15 to 18 kilometres, we see the foaming white crests of mighty breakers, a sign that there are extensive coral reefs. Actually, a mighty barrier reef stretches from Cape Friendship north as far as the Martin Islands, interrupted by several passes. Between the coast and the barrier reef the water is deep enough for larger ships. However, extreme care is advised when navigating this stretch, as precise soundings have not yet been made.

A few kilometres north of Rautan Strait is a fairly wide river, the mouth of which is blocked by a sandbar over which a heavy swell is usually breaking. Natives from the Shortland Islands maintain that this river is the outlet of a lake not far inland, which is fed by a number of mountain streams; both river and lake should be navigable by small vessels and large boats. The coast from here on consists of a 26-kilometre stretch of the same nature; it is flat and sandy and rises gently inland. On the barrier reef lies a small isolated coral island, Stalio Island (Otua), opposite the mouth of a fairly large river, blocked by a sandbar. However, with a good surf boat this can be crossed without difficulty and you find yourself in a fairly deep river that, for several kilometres upstream, is never less than 3 metres deep. The banks are flat at first and then gradually rise, and we make the observation that they consist of a deep layer of loam, rich in humus and intermixed with sand. Small canoes, which lie lonely and abandoned on the bank, indicate that natives are in the vicinity; we come to the same conclusion from the gardens along both banks. I followed this interesting river for about 10 kilometres, but did not have time to explore it further. But I would most urgently recommend later visitors to Bougainville to investigate this river. At its mouth you usually find numerous natives, armed of course with the inevitable bow and barbed arrows, but not as dangerous as they appear to foreigners. They usually come here to catch fish, but their home is somewhat further north in the Kaianu region.

North of the river mouth the spurs of the Crown Prince Range come closer to the shore and at the same time become steeper and more rugged. Beyond Kaianu they come right down to the shore. The huts of the villages are beneath palms on the slopes; we observe plumes of smoke rising far inland, and on the mountain sides there are cleared patches of forest, prepared for gardens.

Following the Kaianu district is the Koromira region. It is reasonably populated, and according to the natives the hinterland is also well populated although, as they maintain, by very bad fellows against whom the shore-dwellers have to defend themselves. This is a customary assertion of all shore-dwellers when questioned on the character of their inland neighbours.

From Koromira northwards the coast maintains the same steep mountainous character; in places small shore plains have formed, wedged between rugged promontories. On the outer reef we see two small uninhabited islets, the Zeune Islands (Kobaiai and Baikai), and, further north, in the lagoon the small island of Sovie. As soon as we have passed the rocky corner opposite the island of Sovie, we notice a larger settlement under palms on the flat shore. This is the village of Toboroi.

The people of Toboroi are peaceful; a large proportion of them come from the Shortland Islands, and at the time when King Goroi was extending his domain from there out over the southern half of Bougainville, they formed the northernmost outpost.

North of Toboroi lies a group of smaller, forested islands, designated on the maps as the Martin Islands. Between the largest of them, called Batamma by the natives, and Bougainville passes a deep strait, navigable by larger ships. The landscape of the pass is one of great beauty; tall, steep, forested mountains, rent by deep gorges, rise on both sides. The Marist Catholic mission has had a station here since 1902 – the first such settlement on Bougainville.

Leaving the small island of Arrove in the west, we pass round a steep point, where there is now a police station, and there opens before us a bay, broad and deep, with several adjacent bays, forming splendid harbours. On the southern and southwestern sides of the bay are excellent, fertile, wellwatered stretches. Behind, the Crown Prince Range rises steeply, and when it is not enveloped in cloud we notice a peculiar geological formation. This consists of many sugar-loaf cones appearing to rise from a single base; the walls are almost vertical and often without vegetation; the peaks are covered in a thick green. The cones resemble gigantic termite mounds. When the cloud parts shortly after sunrise and the peaks of the cone become visible, while the mist still lies in the gorges and valleys like a white haze, the view of this peculiar mountain formation is particularly fine. The rock which forms these mountains appears to be a type of basalt.

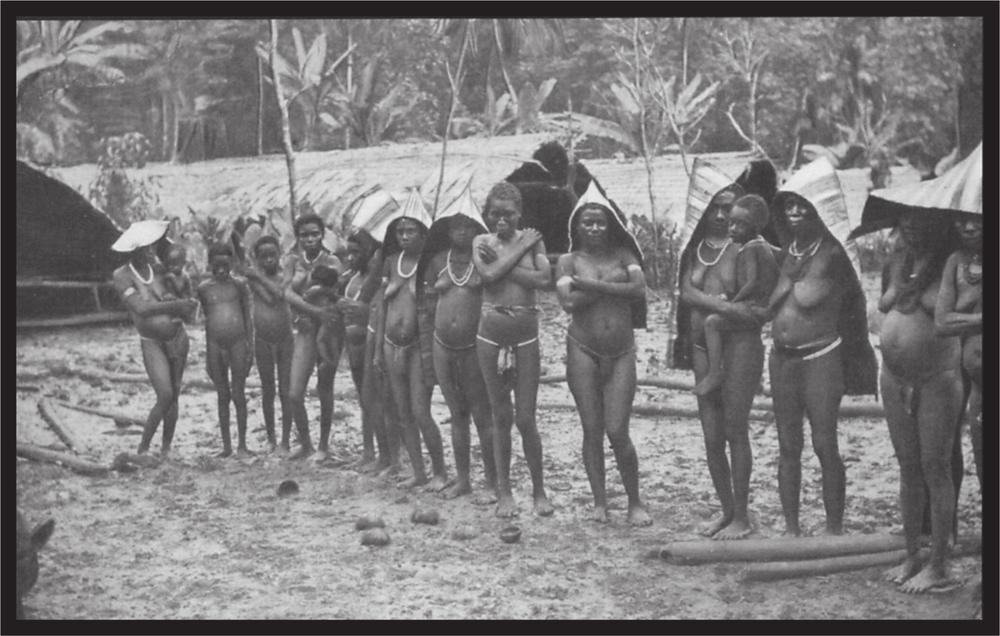

If we come ashore in this bay at the right time, we can see played out before our eyes a fragment of native life that is already a rarity in the South Sea islands. From time to time, either for fishing or attracted by the arrival of a ship, the mountaindwellers hurry to the beach. They do not come individually but in great crowds with the whole family, probably for mutual protection, and perhaps also because nobody wants to stay home in the village when the men are away, since the neighbouring tribes are not to be trusted. Completely naked, their black bodies painted with red or white stripes, holding bows and arrows as well as spears, the seemingly wild band with loud cries makes a dash at the visitors. The latter soon find that the people are on the whole quite harmless, and that the wild cries and incessant gesturing are a consequence 202of surprise and astonishment; for these mountain-dwellers have until now had little opportunity to see white people. Everything arouses their astonishment, their wonder: be it a bright length of cotton, sparkling glass beads, a lookingglass, knife, axe, fishhooks, and so on. They hand over their polished weapons as trade for a trinket, and behave like children when a long-hoped-for toy is given to them. Soon the women also lose their initial shyness, and throng around us to receive their share of the beautiful things. Among the young girls we see many slender, powerfully built forms with agreeable facial features from which the dazzling white teeth shine like ivory pearls; on the other hand the old women with wrinkled skin and deeply furrowed faces are the purest forms of the most ghastly Brocken-mountain witch. In recent years a certain number of these mountain-dwellers have been recruited successfully as workers in the plantations of the Bismarck Archipelago and, as a result of their hiring, it is expected that through them, once their time of service has expired, a greater number of their people will be persuaded to go overseas as well.

However, we want to look further round the bay. We soon find that the north-eastern part is pervaded by numerous coral reefs; however, there is deep water between them; and also the northern half of the bay has good anchorages. Outside the bay, between the Martin Islands and Cape le Cras lie the two small Dieterici Islands, uninhabited and surrounded by coral banks. Several similar small islets rise from the middle of the bay. The shores are flat with numerous rivers running into the bay. However, the land is swampy to a large extent, and is beset with flooding during the rainy season.

The promontory dominating the bay in the north-east is Cape le Cras (Mabirri). The land at the cape is flat, and gently rises inland; it has the same characteristics further north as well. From the cape the reef stretches further northwards once more, like a barrier; and about 14 kilometres north of Mabirri, a broad, deep pass bounded on right and left by jagged coral reefs leads into a quite spacious and completely safe harbour. Even the largest ships have space here. On the maps this place is designated as Numanuma; not quite an accurate name since the village of Numanuma lies to the north, outside the harbour. On a prominent point on the shore lies the village of Bagovegove which apparently has an exposed position, for I found in 1886 that it had just been rebuilt after the inhabitants had been driven out by enemy mountain tribes several years earlier. In 1889 it had disappeared again; the mountain tribes had destroyed it once more, but in 1894 it had again blossomed, only to be turned into a heap of ashes by the old enemy in 1895. Since 1898 it has arisen anew; this time the village inhabitants have been reinforced by a new influx from northern Bougainville and eastern Buka. On my visit in 1902 I counted 18 large war canoes and more than fifty ordinary vessels, which give the impression of a large population; it actually swarmed with men, women and children among the huts on the beach. In 1889, about 1 kilometre south of Bagovegove there was a small village called Sapiu. This too was destroyed by the mountain people.

The harbour surroundings are less interesting. Beyond Bagovegove lies a swampy depression that is impassable. South of the former village of Sapiu marshes extend far inland. The local people do not have a good reputation; they are inveterate cannibals, living in a constant state of enmity and war with their neighbours, and seeking to capture people both in open attack and by stealthy ambush. Whether the mountain-dwellers or the shoreline people are the aggressors I cannot say. However, I tend towards the opinion that the inhabitants of the coastal villages, mixed together from every district, are the real perpetrators, who settled here purely for love of fighting and plundering, and it serves them right when the mountain people frequently exact bloody vengeance.

The natives at Numanumahafen have had brief hostile encounters with whites as well. In the 1870s the small steamer Ripple was surprised by the natives. Captain Ferguson and several of his crew were killed, the rest were more or less seriously wounded. However, the few survivors succeeded in freeing the anchor cable and getting the steamer under way, which in view of the situation was a task bordering on the miraculous. Vengeance was not long in coming. The then mighty king Goroi on the Shortland Islands was a friend of Captain Ferguson. He assembled his warriors and launched a vendetta which lasted for several months during which the entire population of the Numanuma settlement was wiped out. Since that time the people have become more peaceable, but they are still the least trustworthy on Bougainville.

Almost due west of the harbour rises the mighty Mount Balbi (Toiupu), which caused such terrible disappointment for Herr Hugo Zöller because, ‘after long observation and precise measurement’, he found that it was only 6,000 to 8,000 English feet high. The ‘precise’ measurements by Herr Zöller allow, as we see, a range of at least 2,000 feet. I tend to give more credence to the older, ‘imprecise’ measurements.

It is not often that one beholds Mount Balbi with its entire surroundings clear and distinct; often it is concealed by clouds for days or weeks on end. At sunrise it is occasionally visible for one or two hours, then the mist rising from the valleys and gorges gradually closes round the peak and finally hides it completely.

The view from Numanuma when the mountain 203is cloudless at sunset, is incomparable. Scarcely has the sun sunk behind the giant peak, concealing the entire eastern slope in deep shadows, than the highest peaks and the rims of the still active volcano Mologoviu, not far from the Balbi peak, shine as if surrounded by a silver halo. The sun’s rays penetrate the crater and illuminate the yellow sulphur deposits so that the whole thing shines like a giant golden shell from which a plume of smoke rises which, illuminated by sunlight, passes gradually from deepest brown to dark yellow, then into a shining sulphur yellow, and finally spreads out high above the peak as a silver-white cloud which is slowly driven away by the wind. Such a view is a rarity, but whoever has enjoyed it once never forgets it during his lifetime.

A narrow strait close to Bagovegove between reef and shore, and suitable only for smaller vessels of shallow draught, leads back out to sea. The coast, stretching northwards, has a narrow coastal plain behind which the Emperor Range rises, with its splendid wooded slopes and valleys grooved by mountain torrents. Many small embayments with flat sandy beaches seem eminently suitable as sites for native settlements; actually, up until 1888 there were a number of villages here, of which the only evidence of their existence is the coconut palms planted by the villagers. The further north we go, the broader is the coastal flat and at Nehuss Point it is quite extensive. The barrier reef stops above Numanuma harbour and from there to Nehuss Point there are only shoreline reefs. Then a barrier reef reappears extending, with gaps, almost as far as the north-east corner of Bougainville.

North of Nehuss Point the beach recedes so that even the biggest ships can find safe anchorage between it and the barrier reef. On the reef are two small islands, the southern one named Hohn and the northern Tekareu. They are named Torututa and Torubea by other natives. A navigable passage between Hohn and Nehuss Point leads into the harbour beyond. The opening in the reef between the islands of Hohn and Tekareu, however, offers a wider opening, better in every respect. The coastal flat narrows here and the mountains rise fairly steeply from it. The population gradually becomes more dense; high above on the mountain slopes and ridges we see the carefully constructed huts, side by side in rows after the local custom. Beyond Cape l’Averdie the coastal flat widens and the outcrops of the mountain range are less steep. Numerous canoes filled with the almost black natives are nearly always seen here, some going fishing, others negotiating trade with neighbouring tribes.

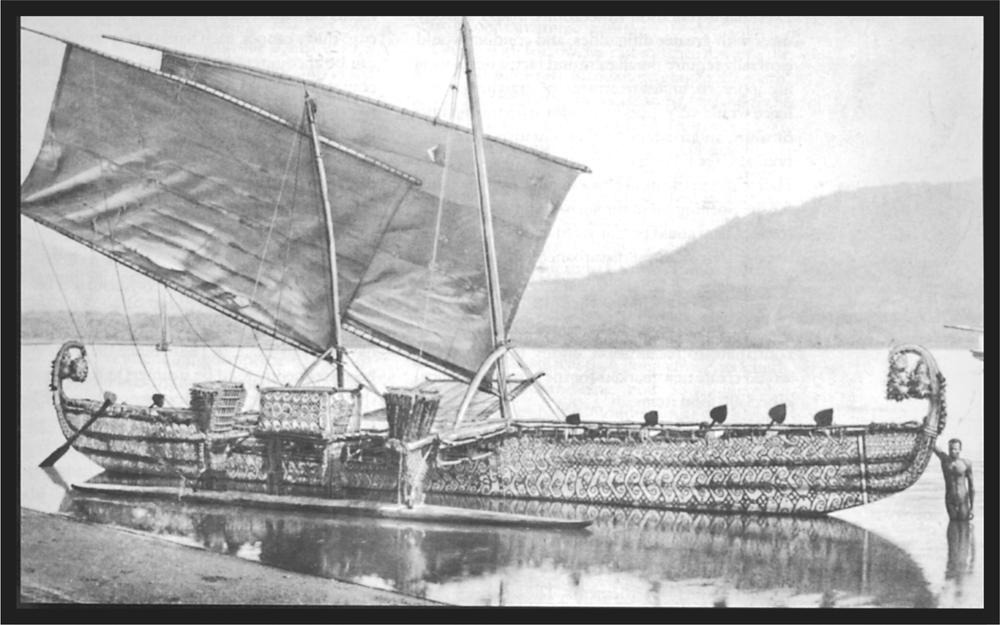

Plate 30 Sailing canoe from the Hermit Islands

The point designated by Bougainville as Cape l’Averdie is not precisely established. He sailed past at a fair distance from shore and could not distinguish that several small islands lay off the north-eastern end of the island. Once past these small islands we observe that the coastline bends to the west almost at right angles, and that on the corner that we indicate as Cape l’Averdie there is quite a good harbour, formed by the main island, the two small offshore islands, and the coral reef. 204The outer, uninhabited island is called Teworran, and the larger inhabited one closer inshore is Keaop. The entrance into the harbour is broad and deep, and marked on both sides by reefs. The outer harbour is very deep but the inner, which is protected by a reef running out from the main island, is a very good anchorage. Separated from the inner harbour and close to Keaop is a second reef harbour, which is excellent for smaller ships. A great advantage is that a stream, full throughout the year, opens into the inner harbour.

Since the people of Keaop are almost constantly in conflict with the mountain-dwellers, the stretches of shore opposite the island are uninhabited. The first inland villages are fairly far away from the beach. The inhabitants are industrious agriculturalists, and usually bring great quantities of produce, especially taro, to the shore. On the other hand, they are also extremely warlike, and only rarely does one see an unarmed male. I have sought them out at various times in their mountain villages and always found them to be friendly and forthcoming. Great friendship does not appear to exist between the neighbours, since in every village spears, bows and arrows lean against every hut, to be instantly at hand should anything arouse suspicion. Thus, should a visitor arrive in the village unannounced, he must not regard it as a sign of hostile intent when everyone immediately goes for their weapons and he suddenly finds himself opposed by a crowd of natives waving spears or armed with bows; after recognition the general joy is so much greater. Eventual exploration expeditions would scarcely meet with greater difficulties, and conduct would generally require much calm and tact; a domineering approach, unjust treatment, or straight-out violence would very quickly transform friendship into hostility, and frustrate further initiatives. The harbour at Cape l’Averdie, also named Ernst-Gunther-Hafen, will in the future be a suitable starting point for the opening up of the surrounding land. Great tracts of land could be cultivated here without causing even the slightest disturbance to the natives. I believe that organised plantations with strict work divisions for the natives would be welcomed throughout Bougainville, because these would contribute to pacification among the tribes and would create new markets for the surplus produce, especially food items.

About 4 kilometres west of Ernst-Gunther-Hafen lies another small harbour with good anchorage. It is named Tinputs, after the local village. A further 12 kilometres west lies small, safe Lauá harbour, on the eastern slope of the Banniu foothills. The entire stretch of shore between the two harbours is uninhabited, and only far inland do we encounter the first settlements. The land rises gently, and is intersected by numerous watercourses; many thousands of hectares of excellent generally fertile soil are available. In the north of Bougainville there is no other excellent agricultural area that is so extensive. All the advantages unite here to favour setting up plantations on a grand scale: splendid harbours, numerous watercourses that never dry up, regular rainfall, fertile soil, and no natives to be disturbed in their dwellings. Besides, in the interior and in neighbouring districts, there is quite a dense population, which for many years has been accustomed to sending their young people abroad as plantation workers.

On the western slope of the Banniu Range a deep pocket stretches inland, usually known as the harbour of Banniu. However, it is of less value as a harbour, partly because of its high shores and mountainous hinterland, and partly also because due to the north wind the sea drives in strongly, and does not allow ships to anchor. During southerly winds Banniu harbour is an excellent anchorage.

It is not improbable that the high Banniu Range is the same headland as that designated as Cape l’Averdie by Bougainville. He sailed with his ships far offshore and would barely have been able to see the low point that today we call Cape l’Averdie. The tall, thrusting Banniu Range, overgrown with palegreen grass, is visible from a fairly great distance offshore, and then appears to be the north-eastern tip of the island. Further description of the coast by Bougainville also corroborates our suggestion.

Beyond Banniu Bay the shore is high and steep, but from time to time small bays open out with flat sandy beaches. Here we generally find big settlements with quite large populations. Fleets of twenty to thirty canoes, each with twenty to thirty crew, can be encountered quite often as there is regular contact with Buka from here. We see large villages not only on the shore, but also on the heights the brown roofs peep out of the green foliage. For years the coast has been a principal recruiting spot for plantation workers, and so the people are less shy than elsewhere, and one can communicate with them through pidgin English.

We now approach the southern tip of Buka, sailing along the steep coast of Bougainville, now in the narrow, yet deep, King Albert Strait, which separates the two islands. I was the first white person to navigate this strait, in 1886. Since that time it has been frequently used by steamers as well as sailing ships. Of course an accurate knowledge of local conditions is essential for navigating the strait; in particular, the navigator must have a precise knowledge of the tide conditions, which change every six hours. Inside the strait itself lies the small island of Sohanna, dividing it into two arms, one going to the west, passing north of Sohanna, while the other passes the east coast of Sohanna, going south. Both are navigable, but the arm going southwards is preferable because the tide race is less strong.

When we have finally passed the strait fringed 205by coral reefs, we find ourselves in a broad basin, bordered in the east by the island of Bougainville, in the north by the island of Buka and its offshore reefs, in the west by the mountainous islands of Matehes, Toioch, and Katitj, and in the south by a number of small islands. Also, on the side towards Bougainville there lie a number of small uninhabited islands. The current maps, which are drawn up mainly from Hugo Zöller’s sketches, give a completely false picture of this area; for example, the large island indicated south of Sohanna does not exist. The broad basin forms an excellent harbour; ships have it in their power to choose the most favourable anchorage according to the prevailing wind direction.

The basin cuts deeply into the main island towards the south-west, thus forming a fairly long peninsula at the north-western end. This is steep and high to seaward, but towards the south sinks gradually down to the shore, and is enclosed here by a sometimes wider, sometimes more narrow border of mangrove swamp. If we come through the strait by ship and anchor in the large basin, we are met by the same natives whom we have greeted outside the entrance. This time they visit us not in their large war or ocean-going canoes but in small dugouts with outriggers, often also on simple rafts of thin wooden battens lashed together. They have come across the peninsula, which is not very wide, and are now in the vessels used for fishing in calm water. The entire peninsula is cultivated by the natives; the paths lead through large banana plantations and fields of taro.

The western coast of Bougainville is, first of all, a narrow coastal flat which widens significantly at the southern corner of the basin. The Emperor Range rises from the coastal flat firstly as a gently rising mountain slope, but soon loses this character and forms steep, almost vertical walls. The small islands in the basin are agriculturally of little value; but on the other hand, the coast and the hinterland of Bougainville, which border this splendid harbour, will gain dominant significance over time, because the soil is generally good, and numerous streams from the mountains ensure sufficient irrigation.

The further we follow the western coast southwards, the more the mighty Emperor Range unfolds before our eyes. As a rule its spurs come right to the beach, and enclose valleys that would be suitable for small plantations. In the valley floors, copious streams hurry to the sea; however, none of them is navigable. The range is well populated here, but the population does not have a very good reputation. Beyond Cape Moltke, the mountains become lower and the slopes more gentle, and the coastline forms a broad flat indentation with a well-watered coastal flat of fairly large extent. This is the Empress Augusta Bay, with the small Gazelle Harbour in the southern corner. HIMS Gazelle anchored here in 1875 during her circumnavigation of the world. During the south-easterly season the little harbour, protected to seawards by the flat Cape Hüsker, offers quite a good anchorage; on the other hand, during the time of the north-westers it cannot be used.

In earlier years, at the time of uncontrolled recruiting for plantations in Australia and Viti, Empress Augusta Bay was a region of bad repute. Recruiting boats were attacked from time to time by the natives, and their entire crews were slain. Since that time a lot has changed; the mountain-dwellers have vigorously oppressed the coastal villages while these were numerically weakened by population outflow; today in previously heavily populated districts we find barely one-quarter of the original number of inhabitants; several large villages have completely disappeared. The natives, so grossly vilified in earlier times, are in any case less hostile today. On several occasions I have visited the villages still in existence, and always found a friendly welcome; traders from the Shortland Islands come here in their boats to buy produce, and no attacks on white people have occurred for years.

From Cape Hüsker the coast stretches in a south-easterly direction to where we started, Moila Point. Several fairly large rivers draining the high Crown Prince Range enter the sea along this stretch; they are impeded to seaward by a sandbar, but are navigable to larger vessels for a fair distance inland. The land is flat and rises gently towards the range, forming part of that great plain that I mentioned at the start of our circumnavigation.

Finally, with sorrow, we cast a glance towards the Shortland and Fauro islands emerging in the south. Until quite recently the German flag waved there also, and the little groups took part in trade with their fellow German islands of Choiseul and Ysabel. Today these islands are under English sovereignty, and the blossoming trade established by German firms in the Bismarck Archipelago has turned towards the Australian colonies.

It still remains for us to become acquainted with the northernmost of the Solomon Islands, the island of Buka. It has already been mentioned that it is separated from Bougainville by the King Albert Strait. It is significantly smaller than Bougainville, its length from north to south being about 55 kilometres. The southern half is mountainous; the highest point around 350 metres. The islanders call both this mountainous part and its natives Zolloss.

These heights drop away fairly steeply to the north, and the northern part of the island consists of a plain, gently sloping from east to west. The whole island consists of coral limestone and repeated random uplifting is clearly recognisable here as in so many places in the Bismarck Archipelago. The entire eastern side of the island falls away steeply to the sea, and has an insignificant beach front 206only at the southern end. The western side is flat, partially bordered with extensive mangrove cover; the island’s few insignificant watercourses all empty out on this side.

On the western coast, a series of coral reefs topped by islands stretches from Dungenun Point southwards, almost parallel with the coast. A lagoon is thus formed between reef and island, offering excellent anchorages.

The northernmost corner of the lagoon, Carola Harbour, is absolutely splendid. It is formed by the island in the north and east, and the coral reef topped by the three islands, Malulu (Entrance Island), Hetau and Parroran in the west. A wide, deep entrance leads into Carola Harbour from the west, between Malulu and Dungenun Point. Other entrances exist between Malulu and Hetau, as well as south of Parroran, between it and the island of Yaming. This latter island and the island of Betaz lie on the same reef; south of it, a pass leads into the lagoon, and to good anchorages behind Betaz, between it and Buka. On the reef stretching further south lie the islands of Matzungan and Sal, both similarly separated by passes. The island of Sal was uninhabited until a short time ago; the reason given by the natives was that on the surrounding reef a gigantic octopus dragged fishermen into the depths; even canoes and their occupants were attacked. Consequently the earlier inhabitants moved to Matzungan. However, the sea monster has not made its presence felt for several years. Many islanders staunchly declare that they have seen the beast in earlier years; one man still living on Matzungan saved his life by swimming, while his companions were seized by the tentacles and dragged into the depths.

Beyond Sal a series of small uninhabited islands extends in a southerly direction, to some extent a continuation of the previously described series. The gaps steadily increase and the chain ends with the small Phoon group south of Emperor Island. The high islands Matehe, Toioch and Katitj (both the latter are designated on maps as one island, Emperor Island) form to some extent a continuation of the mountainous south of the island of Buka.

At the southern end of Buka a small safe harbour must be mentioned, cutting into the southern part of the island and protected against all wind directions. A pass leads into the harbour from the west, between the southern point of Buka and the island of Matehe; a second runs through King Albert Strait between Buka and the southern offshore reefs with their small islands.

The western side of Buka, like the southern end, has a number of splendid harbours and anchorages; while on the steep east coast, with its great depths of water directly off the fringing reef, they are totally absent.

The island of Buka is densely populated, and for that reason alone might not be suitable for plantations to any great extent. The inhabitants belong to the same tribe that inhabits the island of Bougainville, and have for many years been accustomed to hiring themselves out as workers.

Both Bougainville and Buka yield little in products. The ships arriving to recruit workers as a rule take part in the small trade. The southern end of Bougainville is favourably placed, but trade there is drawn to the English Shortland Islands, and little benefit comes to the German settlers.

About 60 kilometres north-west of the north cape of Buka lies the Nissan group, or Sir Charles Hardy Islands. It is an atoll running east to west and surrounds a fairly large and spacious lagoon. The eastern walls are up to 15 metres high in places and drop away steeply. The island is interrupted by several passes at the north-western end; the southernmost of these, 4.5 metres wide, allows passage for smaller vessels into the lagoon, which forms a totally safe haven. In the middle of the lagoon, the inner rim of which is almost completely covered by mangroves, lies the small island of Lehon. As well as the passes mentioned, two others lead into the lagoon. These are navigable by boats only, and separate the two smaller islands of Varahun and Sirot from the main island.

North of the group and separated by a strait about 3 kilometres long, lies a smaller group, the island of Pinepil with the smaller island of Esow. This group too is a raised coral atoll, lying east to west with a pass at the northern edge leading into a small lagoon and navigable only by smaller ships.

On current maps the Nissan group is shown too large; actually it is about 15 kilometres long from north to south and about 10 kilometres wide from east to west.

The inhabitants of the island are emigrated Buka islanders, who still undertake annual journeys there. However, on the Pinepil group a strong admixture of paler Melanesians is noticeable, which is accounted for by a long-term, regular annual interchange between Pinepil and wuneram (St John). Both island groups are therefore most interesting because they form the bridge between the black Melanesians of the Solomon Islands and the paler Melanesians of the Bismarck Archipelago.

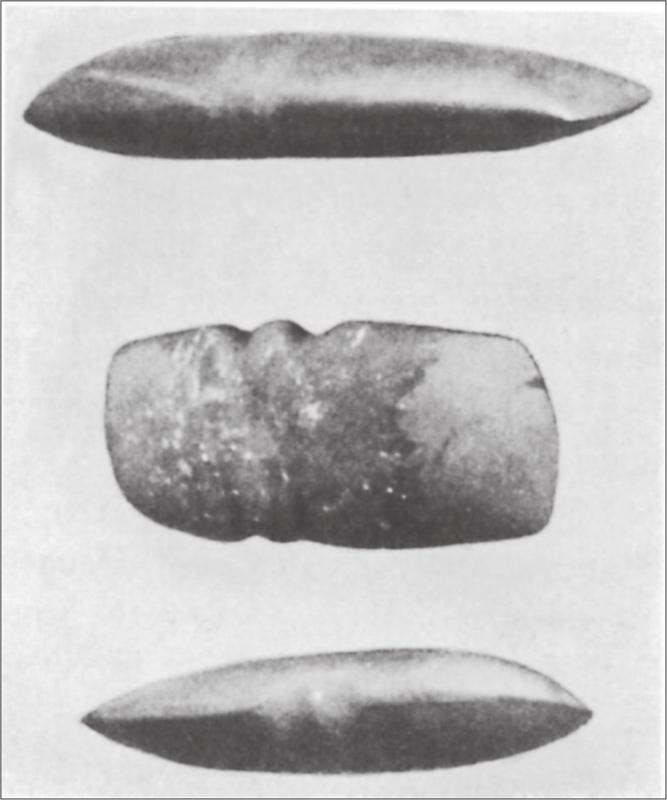

Finally, the Carteret Islands consist of an almost circular atoll on which are scattered the seven islands comprising the group. In the west and south, passes lead into the lagoon. Beginning from the southern pass, and proceeding through east to north the sequence of islets is as follows: Yelaule (uninhabited), Epiül, Ehánu, Ehüene (uninhabited), Yolása, Yésele and Yangaine (on the extreme western border of the atoll). The group is inhabited by about 250 natives, immigrants from Buka, who were driven out of the Hanahan district years ago. Their tradition teaches that the group was 207inhabited at that time by pale-skinned people who were gradually subjugated, and who left behind as isolated traces polished axe blades of Tridacna shell which are occasionally found in the ground today, and which match similar items from Mortlock and Ongtong Java. The population might probably, therefore, have been a tribe of Polynesians, since they occupy the abovementioned neighbouring islands even today.

Both groups, Nissan and Carteret, yield about 120 tons of copra and a small amount of trepang annually. The small Carteret Islands with their relatively dense population are of no agricultural significance. The bulk of export falls on the Nissan group and could be increased significantly if the natives would work the land and plant coconut palms, which would do extremely well here. Because of the great laziness of the natives, whose needs are abundantly met, this cannot be expected. The firm of Forsayth in the Bismarck Archipelago, which has maintained a station here for twenty years, has recently begun cutting down trees on the island and planting coconut palms.

The population1 from time immemorial had the reputation of being savage and bloodthirsty. The earliest discoverers reported bloody conflicts, and this was still by and large the general rule until not many years ago. Not behind the back and by indirect means but openly and courageously do the Solomon Islanders attack white visitors. Although frequently driven back with bloodied heads by superior weapons, they always renewed their attack. It is difficult to determine who caused these hostile encounters first. The seafarers of old in their dealings with the natives were probably not always at pains to respect the peculiarities of the natives; they may often unwittingly have caused offence and thus, given the warlike and contentious spirit of the natives, who moreover could not communicate with the foreigners, a confrontation was unavoidable.

About the middle of the 19th century, a further element came into consideration which had not contributed to pacification of the natives anywhere in the South Seas, at least where, as on the Solomon Islands, a brave and warlike population lived. This element was the whalers, sandalwood harvesters and work recruiters. For the Solomon Islands only the whalers and recruiters came into consideration. At that time, the former found a lucrative field both west and east of the islands, and thus frequently came into contact with the Solomon Islanders. They soon realised that the latter could in a short period of time be trained into competent seamen, and that they were useful in other ways on board ship during the voyages. Many were compelled to take part in the long voyages, often being finally put ashore on a foreign island with foreign people. Such an experience would have caused bad blood; whalers, even had they not intended to augment their crew in the usual way, but landed after a long voyage to replenish their stores, were regarded as enemies in those regions, and were treated as such.

Worker recruitment was even worse. Whalers had always stolen only a small number of natives, and as the whales had soon almost totally disappeared from these regions, the hunters moved on to new hunting grounds. Work recruiters were far more intent on filling their quotas. They went from place to place, scouring the entire coast with their boats and, for good or evil, had to come into conflict with the natives, with whom they were not able to communicate, and who, from experience or from hearsay about the ways and means of recruiting, knew and regarded them as kidnappers. Sadly, it cannot be disputed that worker recruitment was for many years very often done by no other means, until the European administration succeeded in putting an end to this disgraceful conduct. But basically it was only cleared up when the authorities had annexed the islands, and they became governed by administrators. We should not be surprised that in those times murders of white people were recorded every year. These may have been brought about through their own fault or, as was sadly also the case, it may have been revenge for previous encroachments by other recruiters. At that time every white person was regarded as an enemy, whether he was a recruiter, trader, traveller, or missionary; the crime of the one has frequently been the cause of the death of another, completely harmless, friendly man.

Today worker recruitment is supervised by the authorities, and transgression on the part of white people belongs among the exceptions; consequently hostile encounters and attacks by the natives have become less frequent year by year. Recruiting has, over the course of time, become an institution known by all natives; they know that they will be taken to a foreign place, have to work there, and after a certain time transported back home, enriched by the sum paid to them. Many hundreds of their people before them have been taken to foreign parts and returned well looked after. They have learnt from the latter what goes on, and not only the attractive earnings but also a type of yearning to get to know this distant land with the wonderful things that those returned talk about, encourages them to go. Over the course of time, the natives have become familiar with the various work sites and, according to whether their reputation is favourable or unfavourable, the recruiter’s task is made easier or more difficult. The good reputation of a place depends on several factors. First, the prevailing health conditions come into consideration; if only a few natives return, and report the death of many of their people, then the good reputation of a place is lost once and for

208all; neither the most humanitarian treatment, the most extensive care, nor the richest payment can persuade the natives to go there. Inhumane treatment, especially insufficient or unacceptable food and payment, are secondary as far as the reputation of a work site is concerned. If a bad reputation precedes a place, it becomes very difficult to recruit labourers for it; if the opposite is true, then the recruiter has a full ship in a short time.

Of course many other factors are involved in influencing the success of recruitment. Perhaps a major feast is in progress or is planned in the district; in this case success can hardly be counted on. To leave a feast in the lurch cannot cross the mind of a native; the recruiting ship will come again, and the opportunity will be offered often enough to go abroad. Or if the village is at war with the neighbouring tribe, as is not infrequently the case; then the young men are needed for the defence of their homeland, and even though they want so much to go away, they are held back by the elders and the family heads by power and persuasion. In such cases it is advisable to leave the natives to themselves; for the departure of one or other of them not infequently arouses bad blood in those staying home and causes conflict and enmity.

Worker recruitment of the present day should therefore not be confused with the atrocities of earlier times. One can maintain with complete justification that the increased contact between natives and white people which is caused by recruiting, exercises a not insignificant civilising influence on the former. They have learnt to recognise that the white man is not to be regarded absolutely as an enemy whom one must guard against, and whom at best one attacks with spear and club without further preliminaries; they have experienced that attacks on whites are punished in the same way as their initial attack; and although no great friendship has developed, a certain trust has arisen over the course of time.

In communal contact on the plantations and other work sites, the natives have let many old tribal prejudices drop, and the labour recruiting has undoubtedly effected forgiveness in the minds of the natives. Natives who earlier opposed one another as mortal enemies, interact in a friendly way after recruiting. Meanwhile they get to know one another; the old enmity, the traditional tribal hatred pass away while abroad, and when they return to their own villages when their time of service is completed, they mediate the initial approaches and frequently a lasting peace. On my numerous excursions to the various islands I have often had the opportunity of observing the gradually expanding peaceful contact of the natives with each other, and the benefits arising from this are also useful to the white visitor.

I have discussed labour recruiting here because many incorrect views prevail even today, brought about by people who know nothing about the whole business, or who know only the old recruiting methods and believe that nothing has changed since that time. Many years ago I fought with the pen about the then evil situation; today I would not actually know how one could make a reproach against the current recruiting situation.

The inhabitants of the German Solomon Islands belong to the great Melanesian stock. Nowhere else do we find this stock more pure and unmixed, probably purest on the large island of Bougainville, although here and there especially in the coastal villages, traces of a foreign interbreeding make themselves noticed, probably a result of immigration of pale-skinned Polynesians. The reason for the racial purity is probably found in the warlike ways of the inhabitants, in their hostility to everything foreign and the therefore inhospitable reception of all newcomers. By their location the northern Solomon Islands were not so heavily exposed to immigration from the east as were the other islands, further south-east. On the southern Solomon Islands, the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and Fiji the Polynesian influence is obvious; on the other hand, on both our German Solomon Islands, Bougainville and Buka, it is concealed, and is only detected after careful observation. Natives from the small island groups of Sikaiana, Ongtong Java, Tasman, Marqueen and Abgarris in the north and east were occasionally shipwrecked on Buka and Bougainville; also the Gilbert Islands left their contribution, and demonstrably a few of the Carolines.

The mountain-dwellers on the island of Bougainville have a dull black skin shade and generally have crinkled hair, although not a small number of natives were sighted who, besides the black skin shade had straight, or less wavy hair. On the coasts but especially on Buka, Carteret and Nissan as well as the dull black natives, some who must be called dark brown are also encountered. Occasional light brown individuals are found here and there among the coastal-dwellers. They are interbred, with the Polynesian element predominant.

On the plantations in New Britain I have often had the opportunity of observing the interbreeding of various Melanesians, as well as with light Polynesians. A fixed rule for the appearance of the offspring of these marriages can hardly be established; in some cases the mother’s characteristics were dominant, in others those of the father, while occasionally characteristic features of both parents appeared unmistakably side by side in the offspring. It is understandable that on the islands of Buka and Bougainville, where at least the influx of Polynesians must be regarded as smaller, the Polynesian characteristics are gradually almost totally blended in. However, the occurrence of such interbreeding 209is verified by a case that was brought before me years ago on Buka. I met a pale brown woman with curly hair and Polynesian facial features who, according to the villagers was the daughter of a Buka couple. Her parents were no longer living, but I was able to establish that the mother had been paler than a Buka woman should have been. She had therefore probably been interbred, the offspring of a relationship between a Buka man and a pale-skinned Polynesian woman.

Among the numerous mountain-dwellers that I have seen, I have never come across such a light skin shade. The dull black is by far the dominant one; besides this, an intensive dark brown also occurs, probably a result of interbreeding with the coastal tribes. The appearance of straight or slightly wavy hair here would hardly have occurred through interbreeding with straight-haired Polynesians. I was told at Arawa Bay on the east coast of Bougainville, and it was affirmed by the mountain-dwellers, that in the interior live a few tribes in whom straight hair is predominant and whose body size is smaller. I could not tell whether this is one of the many fables that the natives love to tell when asked about the inland tribes.

The language of the northern Solomon Islanders is not uniform. On Nissan and Carteret, which were originally settled from Buka, they speak the same language as on the latter island. The Buka language is also spoken along the whole north coast of Bougainville, and it is understood along the coast about as far as Cape Moltke on the western side and Numanuma on the east coast. The inhabitants of the Emperor Range have an unique language, as do the inhabitants of the Crown Prince Range, whose language is different again from that of the neighbouring coastal tribes. On the Shortland Islands south of Bougainville the Polynesian element is already clearly evident in the language. I give the numerals from one to ten as an example (Table 1).

Table 1

| Buka | Emperor Range | Crown Prince Range | Shortland Islands | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | atoa | paäs | monumoi | kala | |||||||

| 2 | a huel | bák | kikako | elua | |||||||

| 3 | topisa | kukán | páigami | epissa | |||||||

| 4 | tohazi | tánan | korégami | efati | |||||||

| 5 | tolima | tónim | uvugami | lima | |||||||

| 6 | monom | tunom | tugigami | onómo | |||||||

| 7 | tohetu | towut | paigamituo | fitu | |||||||

| 8 | towali | towal | kitakotuo | álu | |||||||

| 9 | tosíe | tosie | kámburo | ul’a | |||||||

| 10 | maloto | sawun | kuvúro | láfulu | |||||||

The villages are each governed by one chief; however, powerful and enterprising chiefs exert influence over weaker neighbours so that the latter conclude defensive and offensive alliances with them. Such alliances are not uncommon, and unite whole districts near and far under one nominal overlord. The position of chief is inherited, the successor is named by the father, and is not always the eldest son. But if the chief makes himself unpopular within the tribe it can happen that he is relieved of his position, slain or driven out. Thus the chief Zikan of Lundis on the west coast of Buka was driven out by his people and found refuge with the chief Takis in Hanahan on the east coast of the island, where he remains at present. The Lundis people chose another person from their midst as leader.

The individual districts are in an almost constant state of war among themselves, although, in more recent times as I have already mentioned, through the communal labour of members of the different tribes, a more peaceful contact has got under way, expanding from year to year. This is the case especially in the coastal districts; the shore-dwellers are still on a war footing with the mountain-dwellers almost everywhere, and when the latter make their way down to the shore it is always in large numbers, for security against hostile attack. This goes so far that, even when the mountain-dwellers are trading with the shore-dwellers, mutual security is always established by a certain display of power. In 1902 I was an eyewitness to such an event on Bougainville. About 6 kilometres south of Keaop (Cape l’Averdie) the local natives met the mountaindwellers, to trade. As a rule the mountain-dwellers obtain fish in exchange for taro tubers. The Keaop people, mostly women with their loads of fresh and baked fish, arrived; some in canoes, others on foot along the beach. Armed men formed a sort of advance guard. Soon after, the mountain-dwellers arrived; first the armed men, then the women with their loads of taro. Both groups settled down about 500 metres from each other on the beach and began loud singing. Meanwhile a group of men separated from both groups; an older man from each group stepped forward, holding a bamboo cane of water in his hand, and about a dozen armed warriors followed him. As both groups approached each other, the two old men met, exchanged a few words, and then sprinkled the water out of the container in all directions. Their followers then joined them, and 210both parties exchanged betel nuts and ate them. Immediately the women recommenced their song, which lasted only briefly this time. After their singing, the women came up with their loads of taro, laid them in small heaps and then retreated. In turn the Keaop women brought up their fish, laid them beside the taro heaps and then stood aside while both old men looked over the trade goods, probably to check whether anyone had been cheated. Once the examination was completed, the Keaop women gathered up the taro tubers, and then the women of the mountain people gathered up their fish. Then, a further short song followed, and the women departed with the exchanged items. The men chatted for a little while then moved off after their women.

The whole business ran so calmly and in such an orderly fashion, without haggling, and without unnecessary gossip that one might believe that the greatest harmony reigned between both parties; yet the old people assured me that both parties in everyday life regarded each other as bitter enemies, but that the trading of foodstuffs produced a momentary peace. The purpose of this peace is not only the unimpeded exchange of foodstuffs but also the security of the women. As soon as the latter have left, it ends often enough in a battle between the men when one or other party finds itself in a majority.

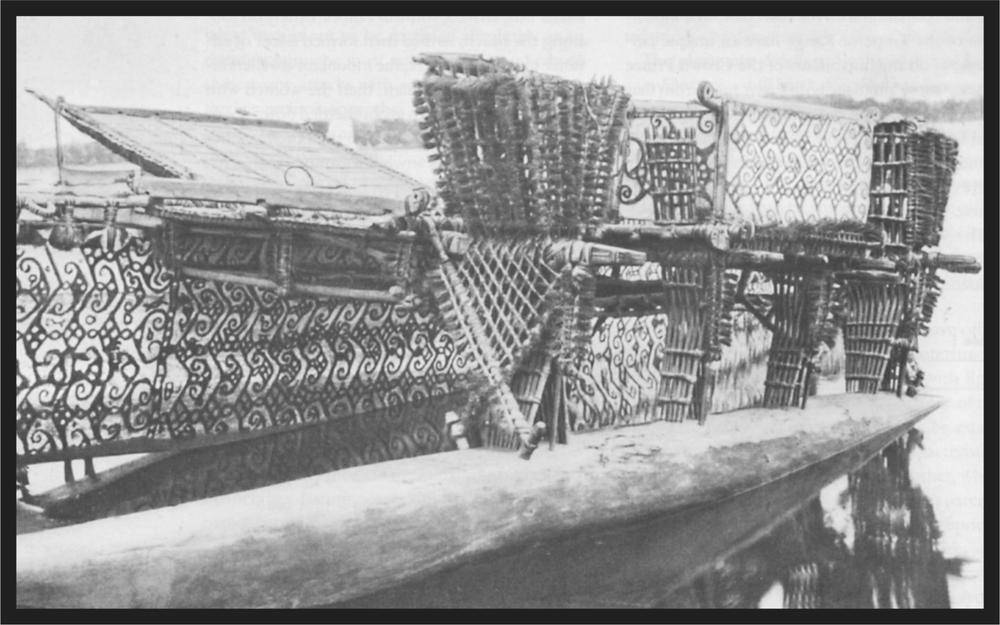

Plate 31 Outrigger of a canoe. Hermit Islands

The entire population divides into several totem groups, which have various bird species as their signs. On Buka the hen (kereu) and the frigate bird (manu) are the signs; not to mention the pigeon (báolo), the rhinoceros hornbill (popo), the cockatoo (ána), and several other birds on southern Bougainville. Male and female natives who have the same bird as a tribal sign cannot marry. Marriages can only be entered into when both parties have different signs; children from the marriage always have the sign of the mother.

Women are sold in most cases by their relatives, but it can also happen that captured women may be taken as wives if the tribal sign permits. The various types of shell and tooth money in circulation there serve especially for buying wives.

Payment of the usual bride price makes the woman the property of the purchaser, and as a rule no further formalities take place; at most a small feast which is given by the relatives in honour of the married couple, and is repeated in the same way a few days later by the new pair. At the marriage of chiefs there is somewhat more celebration. Dances are presented, and on these occasions brightly painted, carved clubs (kaisa) of soft wood are used. Polygamy is universal; whoever can afford it, has several wives; I know several chiefs who have more than fifty. It follows that there are numerous young men who have no wives, or at most one; the older a native becomes and the more wealth and esteem he accumulates, the number of his wives increases proportionately. On the whole the latter lead a quite bearable existence; they must work of course 211but the men also take part in this, and in the village they conduct important discussions, join in during the discussion and business of the men without taking a back seat, and not infrequently convince them to accept their points of view. It is therefore always a good policy during a visit to the villages to make friends with the old women first; once these have been won over, the men do not resist for very long. On the small island of Saposá I know an old, quite influential chief whom I visit regularly on my excursions. He is the fortunate possessor of about fifteen wives, among them two old women whom I have made special friends. During one such visit I discovered in the chief’s hut an extraordinarily finely carved club that had probably smashed many skulls, which he did not want to sell me in spite of a tempting price. Suddenly one of my gracious lady friends got up, grasped the club, hobbled to my boat with it and in silence placed the expensive item in it. Neither the owner nor anyone else raised the slightest protest, and the club is still in my collection to this day. The old chief had a sullen expression but was delighted when I later paid him the original price offered.

Celebrations do not take place for the birth of children. On southern Bougainville, during pregnancy, a feast (marromarro) is held in which only the women participate. If a son is born to a chief, both mother and child must remain in the hut for one and a half to two years and only then are they allowed to show themselves publicly, when dancing and feasting take place. On Buka such cloistering does not occur and a feast as described takes place only when the boy is seven to eight years old.

Child murder does indeed occur on the German islands but much less than in the south-eastern group. In the villages one is able to see numerous children of all ages, and I know families with five or six children, apart from the chief’s families where, according to the number of wives, offspring are found which would cause many headaches for a European father.

The population of the German Solomon Islands is therefore not in the process of dying out as are so many other South Seas populations. Even though they are not increasing particularly, at least there is no decline. Since their seizure by Germany, nothing has been done for them at all, even though they are the most fruitful area for labour recruitment; one might calmly assert that if in the Bismarck Archipelago we had to dispense with the islands of Buka and Bougainville as recruiting grounds, the plantation structure on the Gazelle Peninsula would be very questionable. Hopefully the German administration will soon find ways and means to create an orderly situation there, and of suppressing successfully the ongoing wars and feuds among the population. The powerful islanders would then multiply rapidly and the islands would be counted among the most eminent of Germany’s possessions.

The islands would achieve the greatest yields if the extensive fertile stretches of land, which lie totally unused at present, were transformed into plantations by capital-rich undertakings. On the Gazelle Peninsula in New Britain the establishment of plantations, has in large measure, contributed quite considerably to the pacification of the natives and thereby advanced the development of the population. The same would be the case if similar establishments were brought to fruition on Bougainville; the conditions are so favourable there that, as I have already mentioned in the geographical description of the island, this island could be transformed into one of the most flourishing and productive of all Germany’s South Seas possessions.

The death of a native gives occasion for many feasts. In the north – that is, on Nissan, Carteret, Buka and northern Bougainville – two methods of burial are known: burial in the ground (ha zérokere deakui) and burial at sea (ahäree kuerre); the latter method is the one most frequently used. Feasts and dances take place, and the mourners paint their faces with a type of white clay.2 In southern Bougainville, as well as the previously described methods, there is a third, cremation (kasivei). Cremation is a privilege of prominent people, chiefs and the wealthy. The funeral pyre is set up between four poles, often carved and painted on the upper ends; the corpse is laid on top and burned during howls and wails of grief. The remains are gathered up and placed in an earthenware pot, then a grave is dug between the four poles (kakalo), and the pot is buried in it. During the entire ceremony, loud lamentations sound, only ending when the meal that has meanwhile been prepared is presented. About one month later, there is a second feast, which concludes the real solemnisation. The burial site is, as a rule, surrounded by a carved and painted board fence3 and decorated with plants with bright leaves. On the death of a prominent person a slave is killed; the corpse remains unburied but is not eaten. On our German Solomon Islands we find, as virtually throughout the islands of Melanesia, the institution of men’s secret societies, connected with masking the face and concealing the body.

On Nissan and Buka we find head masks that are not dissimilar to those on New Ireland; on Bougainville masking seems to be less essential, but, on the other hand, secret societies are in full flourish there. In the section on secret societies (Section VIII), the Buka and Bougainville connections will be discussed in detail.

The idea that the Solomon Islanders are, without exception, cannibals is generally widespread. On Nissan, cannibalism is universal; on Carteret, this frightful custom does not prevail, probably because on the small islands the small population is many times more closely related. On Buka and

212on northern Bougainville cannibalism is universal, while it is totally absent on the southern half of Bougainville, whose inhabitants look on their northern neighbours with disgust. If a line is drawn across Bougainville roughly from Arawa Bay in the east to Empress Augusta Bay in the west, this approximately forms the southern border of anthropophagy. In my opinion the coastal-dwellers are the worst cannibals, uniting in communal manhunts, especially to surprise the inland people in their villages and gardens.

Fig. 77 Cremation of a corpse in Kieta on Bougainville

On my travels in the Solomon Islands I have encountered various such expeditions, whose participants assert, of course, that they are going to a feast or are returning from one. The feast was without doubt a cannibal feast. In a few villages on the eastern coast of Bougainville I know for certain that regular manhunts into the interior are undertaken, and the proceeds that are brought home, both dead and alive, are sold to distant regions.

On the small island of Pinepil, north of Nissan, the head is separated from the torso, and after the roasted meat has been gnawed off, an artistic face is fashioned on the facial bones from the crushed kernels of Parinarium laurinum. Such skulls are stored in the huts as trophies. On Buka and Bougainville the lower jaw of the victim is kept as a trophy. In the chiefs’ huts one not infrequently sees whole rows of these trophies stacked side by side on one of the rafters. Almost every chief has an unique feasting place for these frightful meals, not far from his dwelling. Bone remains and fractured skulls in great numbers show only too clearly that the feasts are not a rare event. Women and children eat their portion just like the men; however, it is forbidden for them to enter the area where the bodies are dismembered.

Cannibalism here, as little as in other regions of the world, has its origins in the absence of other animal food. Religious concepts are just as little the reason among the Solomon Islanders. I have frequently heard the cry used by islanders who had flown into a dispute, ‘I have eaten your father (mother, brother, sister)!’ This ‘compliment’ always led to a renewed violent outbreak of the quarrel, because the assertion contained an expression of the deepest contempt. Therefore, originally, eating the slain enemy was probably regarded as an expression of the most abusive humiliation that could have been rendered to him or to his entire sib. However, the old saying, ‘Appetite comes with the meal!’ does not prove to be so well founded anywhere else as here, since, for many, human flesh forms a much sought-after delicacy, and the slain, from far afield, unknown people with whom there has been no contact, either peaceful or hostile, are bought for flesh and eaten.

European influences have so far not been able to achieve anything against the cannibalism of the Solomon Islanders. I have known cases where youths who had served three years as diligent and reliable workers on the plantations in New Britain, had already arranged prior to their return home to undertake an expedition for the purpose of obtaining this long-missed luxury food. Years ago I interrupted a cannibal feast in a village on the Gazelle Peninsula. The natives had fled at my approach; the Buka people accompanying me scented the roast meat and were highly indignant when I would not allow them to eat the delicacies on the spot, but made them wrap them in coconut palm leaves and bury them out of the way in the forest. I am firmly convinced that they never understood this unnecessary waste, and have never entirely forgiven me.

Cannibalism is understandably one of the main causes of the continual reciprocal hostilities; white settlements would quickly bring about a change for the better, as has actually been going on for years already on a large part of the Gazelle Peninsula.

On southern Bougainville one or more skulls are stored in the public meeting houses. These are skulls of slain enemies and a remembrance of a victory won, not of a cannibal feast. The bodies of slain enemies are brought to the village in triumph, publicly displayed for several days and then buried.

A tattoo would leave no visible trace on the black or brown-black skin of the Solomon Islanders; they have therefore developed the custom of scarring the skin – that is, the skin is ripped with a sharp instrument, so that upon healing there are visible scars, forming various patterns. Boys are scarred between the ages of seven to eleven, and the pattern stretches across the face, neck and shoulder blades (Meyer and Parkinson, Album von Papuatypen, vol. 1, plates 26 and 27). Scarring in women stretches over the entire back as well, across parts of the breast, stomach and loins. The procedure is carried out with a sharp shell and 213must be very painful. The scarring of the wounds not infrequently proceeds irregularly; suppuration occurs, destroying the pattern, so that after healing unsightly bulges and irregular scars are produced. A well-healed scarring which shows the lines of the pattern clearly and distinctly is the greatest adornment of both men and women; the latter increase in value according to the beauty of the pattern. In plate 10 in the album of Philippino types by A.B. Meyer there are depicted two scarred negritos from Casiguran in east Luzon. The admittedly not very distinct scarring of the woman resembles surprisingly that of the Buka women.

Music, singing, and dancing of the Solomon Islanders belong in part to the characteristics encountered in this type of Melanesian. In comparison with the performances of other South Seas folk, the music must be set apart on a higher level; on the other hand, in many cases singing and dancing are very primitive, although one also finds performances which show a significant musical talent, and demonstrate a developed ear for rhythm and beat. First, I will briefly describe the musical instruments; they consist of drums of the usual type; that is, hollowed-out sections of tree trunk with a slit on the upper side. The sound is produced by light or heavy blows against the side, somewhat below the slit, by means of one or more rattan sticks tied together into a bundle. This drum, tui, produces a booming sound that carries a long way and, as in other districts, serves for signalling. The hourglass-shaped drum with a monitor skin stretched over one end, so widespread in other parts of Melanesia, does not occur here. Pan flutes, kohe, of bamboo cane, are used as well as drums. A pan flute concert can be regarded as a fairly high musical achievement for a primitive people. The flutes are not only tuned in octaves but have a tonal range from four to six completely tuned tones. (Meyer and Parkinson, Papuatypen, vol. 1, plate 29, presents such a choir.)

I will mention elsewhere the instruments used in the secret societies and regarded as sacred (Section VIII).

As well as very finely vocalised melodic songs which have a particular text as their basis, there are also favourite songs of the people; I could almost regard them as national songs: musical productions which, since they are not based on articulated words, might best be designated as a type of melodic howl. A melody cannot be recognised, and certain multi-voiced harmonies recur, but I doubt whether it would be possible to reproduce the whole thing in our musical notation. It is just the same with the dances: besides those with an excellent rhythm and a fixed beat from which every movement is measured, there are also those which consist basically only of a series of eccentric irregular leaps without a beat. This dance, and the corresponding howling song, have something so indescribably wild that often goose pimples are felt by the spectator; especially when it is seen, presented in the natives’ homeland, possibly as the sole white spectator.

Imagine an open village square, surrounded by the low huts of the natives, the darkness enhanced by palms and other mighty, leafy trees. Naked forms crouch and lie in a wide circle, lit up by the flickering glow of a fire. Without a sound four or five older men, armed with spears, bows and arrows, walk into the centre; then the younger men join them, lining up in rows radiating out from the centre formed by the older men, and the youths arrange themselves on the outer periphery. Then the old ones in the centre begin a monotonous howl, and gradually the young men and boys join in, in harmony, and at the same time the entire group slowly begins to move round the centre point. Soon the tempo quickens, and the dancers on the outer rim have to make giant leaps to keep up. Right in the midst, shrill whistles sound, the dancers clatter their weapons, spring high in the air, and the excitement gradually rises to a point where odd dancers, bathed in perspiration, pitch out of the dense mass of dancers and throw themselves round in wild ecstasy on the ground.

The dance grows still more wild when the pan flutes and wooden drums take part. The musicians, with the deep-toned flutes over a metre long, form the centre round which the dancers are grouped, as previously described, some with smaller pan flutes in their hands. Then the flute music joins in with the ear-splitting howl, then a drum joins in, then several, and the noise rapidly rises to an indescribable din of the wildest kind.

Years ago I was witness to such a night-time dance on one of the small, densely populated islands in Carola Harbour, and the impression will ever remain, unforgotten. With tautened nerves and breath held I enjoyed the wild spectacle, and at the conclusion of the presentation my nerves gradually calmed with long, deep breaths. During long years’ sojourn on the various South Sea islands, I have had the opportunity of observing the most varied dances, but none of them had anything even approximately as wild and spine-chilling as this Solomons dance.

I can be brief about house construction. On northern Bougainville and the smaller islands, the huts stand on level ground; they are 3 to 4 metres wide and correspondingly three to four times as long. The walls are about 1 metre high and above them curves the slightly arched roof made from the leaves of a species of palm (Phytelephas) or from coconut palm fronds (plate 34). The interior is partitioned off by two or more cross-walls. In southern Bougainville, the usual type of construction on the coast was probably adopted from the 214islands further south. Here the huts stand on high poles which between them leave an open space below. Besides this, the so-called tabu houses also occur on this part of Bougainville (illustration by Hugo Zöller, Deutsche Neuguinea, page 368, after a photograph taken by me). These tabu houses are assembly places for men; here visitors are received, here celebrations and feasts take place from which the women are excluded, as entering these houses is expressly forbidden them. The houses do not guard any kinds of secrets; they have probably developed from the need to keep the often quite burdensome female society at a distance. These assembly houses are constructed with great care; in particular the pillars which carry the roof, and the crossbeams, are frequently carved and painted. In places where there are no tabu houses, the great canoe sheds serve the same purpose.

One can scarcely speak of a costume; in the shoreline villages today one sees the loincloths introduced by whites, but they are by no means universal. The inland-dwellers all go totally naked, and we might wonder how they can, in this state, endure the low temperature, which is bitterly cold, particularly at night, in their huts often 1,500 metres above sea level.