IV

The Admiralty Islands

This group forms to some extent the northwestern end of that long, curved chain of islands and island groups which stretches roughly from south-east to north-west, and includes the New Hebrides, the Solomon Islands and New Ireland with New Hanover. The approximate position of the group is between 1º50’ and 2º50’S, and between 146º and 148ºE. It consists of a larger main island and numerous small islands and island groups. The former is about 50 nautical miles long and 10 to 15 nautical miles wide with a fairly mountainous surface whose highest points reach approximately 900 metres.

Just off the north coast of the island, on the offshore coral reef, lie a small number of islands. Far more numerous, however, are those situated off the south and south-east coasts, where they combine into several small groups situated in some instances at quite significant distances from the main island. The most important of these groups are San Gabriel and San Rafael to the east of the main island, the Jesus Maria group in the south-east, the groups St Andrew and St Patrick, Sugarloaf Island, Hayrick Island in the south, and even further south the Purdy Islands and the Elizabeth Islands, about 40 to 45 nautical miles from the main island.

The navigable waters between these islands are not without danger to shipping, because of the numerous coral reefs; the more so since the maps available are not very accurate. The main island offers quite good harbours and anchorages at various places, and also sheltered anchorages are available among the small islands of the offshore groups.

Because of its mountainous nature, the island does not seem to be of great significance for tropical agriculture. The total size, however, amounts to some 1,900 square kilometres (that is, the size of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha), but only a small part of this surface area would be suitable for cultivation. Possibly there are extensive valleys and plateaux in the interior of the island which would be suitable for agriculture, but for the moment we can only judge from the condition of the coast, as, up till now, no white man has ventured more than 3 nautical miles into the interior. The soil, so far as we can conclude from present tests, is of exceptional quality, The climate is humid, but not unhealthy, since malaria, which is widespread on the other islands of the archipelago, does not appear to be strong here.

Recently in the German press the usefulness of setting up a penal colony in these islands was discussed. It is to be hoped that this plan does not come to fruition. The experiences that England, France and other countries have had in this connection do not invite imitation. The system has proved to be costly everywhere, and the outcome, from their high hopes of making colonists out of the prisoners, remained far in arrear of the most widespread expectations.

Fig. 60 Part of Lou Island

The flora and fauna of the islands is essentially no different from that of the other islands of the Bismarck Archipelago. Pigs and dogs are present, the former even in a feral state. In the mangrove swamps the crocodile dwells in considerable numbers, a terror to the entire population; turtles, both Chelone midas and C. imbricata, are still quite numerous in places, and are eagerly hunted by the natives. The sea is rich in all kinds of fish and the dense forests ring with the continuous sound of 156numerous species of pigeon, of which Carpophaga oceanica is the most abundant.

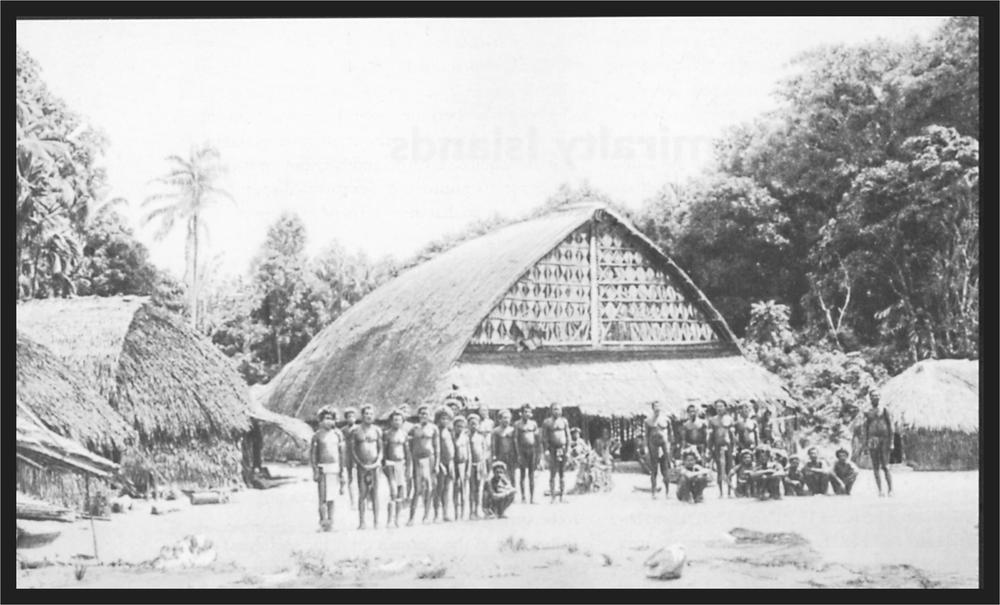

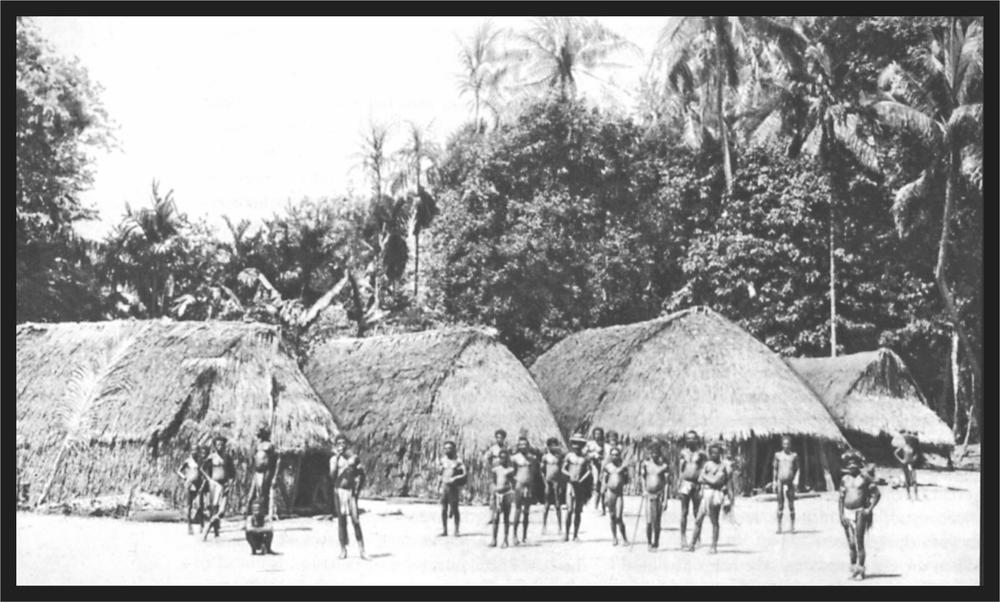

Plate 23 Men’s house in the village of the Matánkor on Lou

The discoverers of the islands had hostile encounters with the natives in those early times, and communication with them has not changed significantly since then. Attacks on ships and the murder of their crews is unfortunately an all too frequent occurrence even today, and in spite of repeated serious punishment on the part of the imperial administration no change has been brought about. Merchants and trading settlements can be maintained only on the small isolated islands, where the white people dwell as if in a fortress. In recent years a not inconsiderable quantity of trepang and mother-of-pearl has been obtained from there by trade; however, more recently these trade sources seem to be gradually drying up. The copra trade is not significant, through a lack of large stands of coconut palms.

The population of these islands reminds us in many ways of the Papuans of New Guinea, with whom there are many external similarities. However, we are not dealing with a pure race here either.

Very many indicate admixture with a paleskinned stock, although the Papuan characteristics are dominant. Communication with the islands on the New Guinea coast opposite still takes place today; whether this relationship is based on traditional knowledge of the location of these islands, or whether it was by chance, can still not be established with certainty. In 1897 I encountered two canoes from the Admiralty Islands on the small island of Jacquinot in the Schouten or Le Maire group. These vessels lay on the beach, carefully protected from the sun, and their crew were easily distinguishable from the Jacquinot people by their different hairstyle and their whole deportment. They were, as far as I could understand, from Sugarloaf Island, and on their journey had touched the Purdy Islands where they make frequent voyages, both to catch turtles and to collect oil from the stands of coconut palms there. They seemed to be on a friendly footing with the Jacquinot people, and gave me to understand that they had already been here for three months and contemplated making the return voyage only in a further three months. They occasionally stop over on New Hanover as well in order to regain their homeland at a favourable opportunity. In later discussion we will see how their influence is clearly recognisable on the western islands, such as Luf.

Their close relationship with the tribes on the New Guinea coast seems inter alia to be marked by the very frequent occurrence among them of the pronounced Semitic nose, which draws the attention of every visitor to this region of New Guinea, appearing again in the Bismarck Archipelago only on western New Britain, whose inhabitants are without doubt closely related to the Papuans of New Guinea. Otherwise they are well-proportioned and of medium height. The hair is frizzy but less thick than that of the Papuans; the spiral winding of the individual hairs which in New Britain (Gazelle Peninsula) and New Ireland, for example, produces the characteristic corkscrew tufts, is less prominent, and it is not uncommon 157to see islanders with curly, and even completely straight Polynesian hair. This feature, however, can probably be ascribed in great part to the customary piling up of the hair with a comb.

In some tribes the skin shade is paler than elsewhere in the Bismarck Archipelago; a lighter yellow is mixed in to some extent with the chocolate brown, sometimes dominating in such a way that the skin shade comes close to that of the pale Samoans. Such cases seem to allow a conclusion of immigration from Polynesia or Micronesia. However, the Moánus and Usiai have the colour of the Gazelle Peninsula inhabitants.

Intellectually the islanders seem to occupy a higher level than the other inhabitants of the Bismarck Archipelago. They are lively and highly excitable. They comprehend readily, and effortlessly learn a wide variety of accomplishments which seem an arduous task to other natives. Some of the boys who had spent time at the Catholic mission school learned to read and write with astonishing speed, and one of them on his return to his homeland wrote letters to the father who had taught him. When visiting a passing ship they examine everything most exhaustively and exchange observations among themselves with very great eloquence, supported by gesticulations with arms and hands. In contrast with the inhabitants of the Gazelle Peninsula or the Solomon Islands, for example, who observe everything with calm stoicism and without changing expression even though it may seem so amazing to them, the Moánus indulges in loud cries of astonishment; and if an object is not riveted or nailed down, you need to keep a sharp eye on him, for when he sees an opportunity he conjures away the marvellous, coveted item into his little baskets or into the canoe lying alongside, with great manual dexterity and the most astonishing coolness. This kleptomania often gets him into all kinds of trouble and strife, when he shows his courage by grasping his spear which is never far away and stubbornly defending the acquired loot. In this a further characteristic comes into view, which makes him very dangerous to the trader, namely his deceit and his hypocrisy. Surreptitiously holding his weapon ready he feigns the most charming expression, the most outgoing, friendly manner, in order to deliver a mortal blow to the unsuspecting person in an unguarded moment which he spots instantly and seizes without hesitation. Almost all attacks are put into operation with this system; first he succeeds in putting all suspicions to rest, which may often take days or weeks; the victim believes that he is surrounded by his best friends, until a blow on the head with a sharp axe causes him to realise his mistake, unfortunately too late. The great superiority and the big advantage of firearms, already long recognised, have motivated the islanders to acquire rifles, especially in the last five years. Since this was not possible by trading, they have attempted to meet their needs by the methods described above, on trading vessels calling in and at trading posts. With their success they have now become more dangerous than in earlier years, as they have shown themselves skilful with the acquired firearms and have put up strong resistance to punitive expeditions dispatched against them, so that these are generally unsuccessful.

The islanders divide themselves into three main tribes named Moánus, Matánkor and Usiai. The first of these live on the coast, build their villages on the shore or in shallow water on the reef, and their houses always stand on poles. The Usiai are inhabitants of the interior, and build their huts on level ground. The Matánkor form an intermediate group between the two; they are agriculturalists but also seafarers though not to the same extent as the Moánus. The Moánus designate with the word Usiai a native who stands in a certain state of dependency on them. From the beginning the Moánus have, through the possession of canoes, been rulers of the sea; they were superior to the inland dwellers by being more quick-witted and cunning, and indeed in many ways they still hold the power in their hands today, in that they compel the Usiai to grow food for them and to hand it over for very small payment or for no reimbursement at all, just as we find on the Gazelle Peninsula, for example, between the shore-dwellers and the Baining, or on Bougainville between the shore-dwellers and the inhabitants of the mountains.

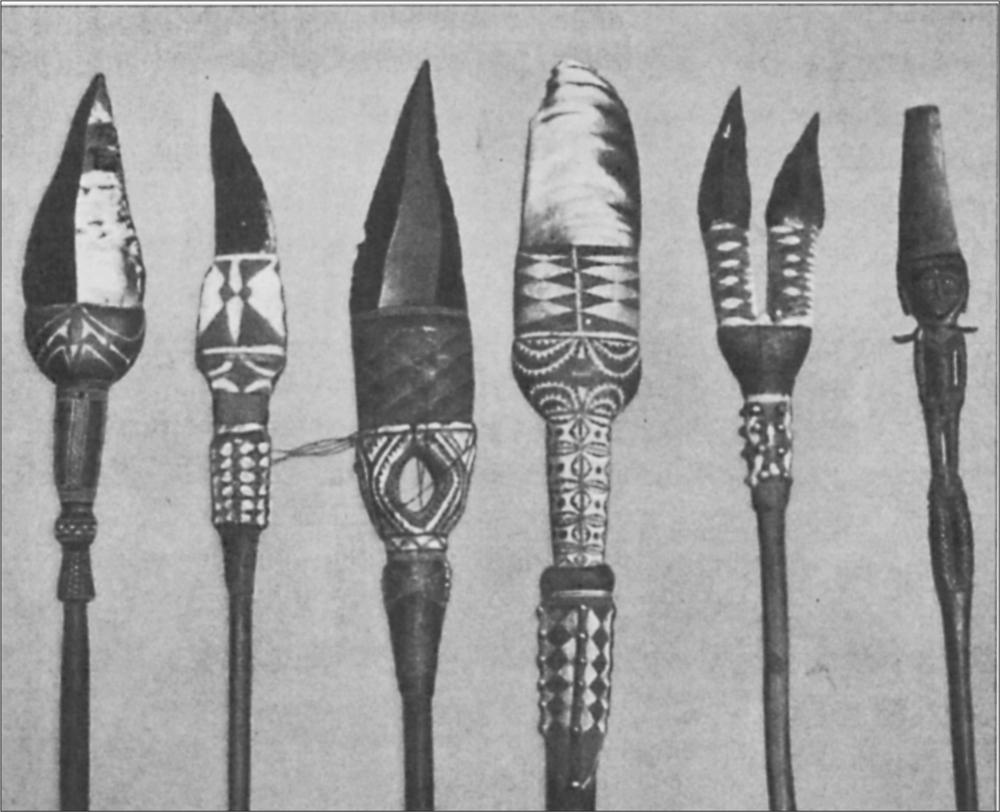

Fig. 61 Spears from the Admiralty Islands

In the ethnographic museums the products and implements of the natives are well represented, and the most striking among them are the spears with the razor-sharp obsidian tips (fig. 61). The latter come in all sizes up to a length of 25 centimetres. 158The tips, which like both edges are produced by knocking off small splinters, have the sharpness of an excellent steel blade. The broad end of the blade is set into a wooden shaft, partly by wrapping round, and partly by puttying with crushed nuts. The shaft is occasionally carved and otherwise decorated; the carving frequently has the human figure as a motif, or that of a crocodile which we find universally represented in various forms in native carvings. They produce dagger tips in exactly the same way as the tips of the spears. To some extent they could be described as spears with broken-off wooden shafts. However, the daggers are used only in rare cases as weapons and more often represent our knives. Since the raw material for spear and dagger tips is not available everywhere, or supply is not able to meet demand, wooden-tipped spears are found as well as those with obsidian tips, and also spears with the long spines of a ray attached.

Fig. 62 Wooden bowl from the Admiralty Islands

A type of battleaxe is found here and there, consisting of a carved, ornamented wooden shaft to which an obsidian blade is attached at right angles. However, I believe that we are dealing here with an item prepared by shipwrecked natives as a trade article. About twenty years ago these axes did not appear in the otherwise very extensive collections from there, and appeared on the scene only in more recent times. Dr Thilenius has reproduced such an axe on page 128 of volume II of his work and gives its origin as the island of Pidelo (more accurately Pitilu) on the northern coast of the main island, but he does not mention whether he had the opportunity of seeing this axe in use. In earlier years, on the island named Pitilu, I was able to observe a large number of armed natives, but none had such an axe as a weapon, and furthermore none was offered to me in spite of lively bartering in which anything and everything was offered.

Bows and arrows are found here and there, used exclusively for hunting; clubs are used in many places but always in very small numbers and of little significance in battle.

Stone axes were probably never used as weapons; today they are completely out of use; the collector rarely succeeds in acquiring blades without a holder. Two different axes were used; one was very primitively made – the blade produced from a hard, lava-like rock, simply being pushed into the thick end of a club-shaped piece of wood. It was, and still is, used by the Usiai. Another axe had the familiar knee-shaped wooden shaft to which the blade was firmly bound. These blades consisted sometimes of sharpened Terebra shells, sometimes of Tridacna shells, and sometimes again, of a grey-green stone. The form of this axe has still been retained, but the stone or shellfish blades have disappeared and given place to plane iron. The shafts are not infrequently carved and decorated. The Moánus and Matánkor possess this type of axe.

Tools are found in great numbers, in the most varied forms and serving the most varied purposes.

Pottery appears here also and is made over a considerable area, because the raw material is available almost everywhere. Yet here too, as in New Guinea, certain centres have built up where special care is bestowed on this art form, and consequently their products are more nearly perfect. The most common pot shape is spherical, the opening narrow or constricted and provided with a rim arching outward. However, there are also pots without rims, almost the shape of a deep bowl. Clay water jugs are used a great deal; they have two openings which are plugged by a stopper of banana leaves or a wooden stopper. Because of its porosity this type of water container is eminently suitable for keeping the contents cool. Pottery manufacture is the same as in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. The women gather the clay, dry it, pulverise and knead it, and produce a mass of plastic material in the form of great lumps or balls. The working tool is a small, flat, trowel-like piece of wood. First the base is formed from a lump of clay, beaten flat. Rolls of the same material are laid on this base and beaten flat with the trowel, while the inner surface is supported with the left hand. Decoration of the pot is not customary; now and again one sees a few simple lines incised with a fingernail.

Extraordinarily characteristic are the large containers prepared for storage of coconut oil, frequently seen in the big canoes as transport containers for which, on account of their sturdiness, they are better suited than the transitory earthenware. A close weave of leaf ribs of a particular fern species forms the framework of these containers. Once the shape of the container is formed, it is coated inside and out with a layer of crushed Parinarium nut and then hung up to dry. After a few days the coat 159is dry and the container ready. Any kind of liquid can be stored in it. These pots serve especially as containers for coconut oil, which is used in many ways in food preparation. The indestructability of these containers gives them a great advantage over earthenware; empty containers are thrown roughly on top of one another in a corner without being damaged; they resist a rough blow without bursting, and if the Parinarium coat comes off the damage can easily be repaired. The shape of these containers varies a lot, as does the size. Some contain about 1 litre of oil, others on the other hand two to three bucketsful. The base is flat for standing on the ground. Often an outward-directed, broad rim is attached round the base; the bulbous shape of the container frequently ends in a narrow neck with a wide, sloping upper rim; others are broad below and narrow upwards; again others have the bulbous shape of the cooking pots. In order to hang the pots in the huts, the lower rim is surrounded with a rolled, thick ring of woven rattan in which the base of the vessel fits. Three or four rattan cords come off this ring, up around the sides and uniting in a loop above the opening.

Fig. 63 Wooden bowl in the shape of a bird. Admiralty Islands

The performance of the natives in the production of large and small wooden bowls is quite outstanding.

The most common form is circular, and the diameter varies from 15 to 125 centimetres. These bowls rest on four round feet carved out of the bulb, which are long or short depending on the curvature of the base. The upper rim is circular and carefully smoothed both inside and out. The outer rim is, as a rule, adorned with a band-like decoration; but the most carefully carved are the large handles protruding out over the rim, which are added to most of these bowls; they serve exclusively as ornaments, since by virtue of their attachment they are not suitable for lifting the often very heavy bowls (fig. 62).

Human, crocodile and bird figures serve as motifs for these handles, in conjunction with a decorative spiral. Other bowls resemble the shape of a bird (fig. 63) or a turtle, the head, tail and bowl-shaped body of which are carved from a single piece of wood. Shallow, oblong bowls frequently have fine, carved handles representing a crocodile; sometimes also an animal shape such as a pig or a dog in a realistic pose is shaped into a bowl, in which the body of the animal is hollowed out from the back (fig. 64).

Fig. 64 Wooden bowl in the form of a four-footed animal. Admiralty Islands

Since these bowls are produced as a rule from hardwood, they demonstrate no small level of skill, the more so when the earlier hand tool could be regarded as the most imperfect of its kind. The acquisition of modern metal tools here as everywhere has not increased the old skill but led to a reduction in it.

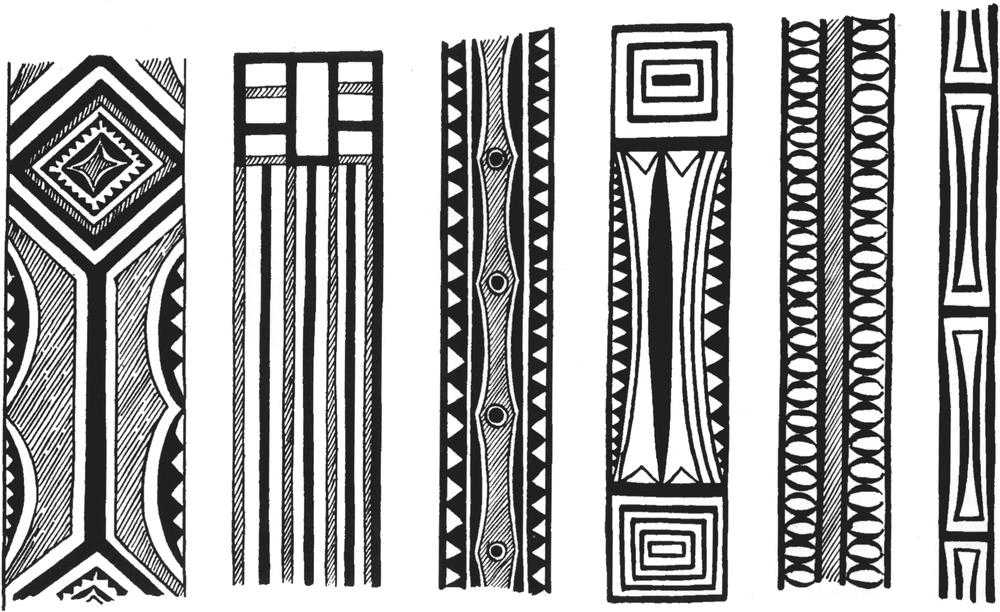

The wooden bowls are used for the presentation and carriage of the most varied dishes. As a ladle, when necessary, they use a decorated instrument made from a half-coconut with a finely carved handle. The many shapes of this ladle handle may be divided into three main groups. The first of these is a flat board, carved in open-work and decorated with grooves and small triangles; the shapes are angular and more or less square or rectangular; these handles always have the broad surface turned inwards toward the container. The second form has a shaft in which the spiral predominates; they are always at right angles to the spoon.

The third form shows various animal motifs in its decoration, also human figures in conjunction with the two previously described forms. The extremely great variety of decoration is characteristic (fig. 65). The power of imagination of the carver always introduces new forms.

A characteristic instrument, the significance of which was unrecognised for a long time, is a type of hook made from a club-shaped piece of wood about 20 centimetres long, into whose thick end a fairly long, curved boar’s tusk is driven at right angles and wedged. For a long time it was regarded 160as a shark-hook because of its size, although by its shape it could scarcely serve as an instrument of capture. Further inquiries in later years revealed that this hook attached to a pole serves to bring certain fruit down from the trees.

Fig. 65 Decorations of ladles, water containers, and so on, of the Admiralty Islanders

Besides the previously described water pots, the natives also produce water flasks from the shells of coconuts. There are two kinds: one consists of a nut rubbed smooth, with a small opening, not infrequently decorated with raised ornaments by carving in relief. To the other a short neck is attached, made from a bamboo tube. Crushed Parinarium nut serves as a means of binding, and before the thick coating has dried all kinds of decoration are carved into it.

Obsidian flakes and sharply honed mother-of-pearl shell serve as knives, the latter particularly in food preparation, the former more in carving. The barb of a ray serves as an awl, used in various ways.

Hooks are used as fishing equipment; these were formerly made from Trochus shell, but these have been replaced by modern fishhooks. As well as these, they use a multi-pronged fishing spear, although not very often, while the main equipment is nets of various shapes and sizes, as well as draw-nets. The natives, especially the Usiai, even today, prepare the material for making the nets. This consists of a coarse or fine thread made from a fibrous plant, of great strength and durability. The individual fibres are intertwined, not woven. The plant that provides this material is the same as that used on the Gazelle Peninsula.

Both Moseley, from the Challenger Expedition, and Professor Thilenius have given comprehensive descriptions with detailed drawings of the islanders’ canoes. They are seaworthy vessels, capable, as we have seen, of long voyages as far as New Hanover and the Schouten Islands. The body consists of a hollowed-out tree trunk; both sides are raised by a plank. Both ends are lengthened by stem and stern pieces which are built onto the body of the canoe. These pieces are frequently decorated, sometimes by carving in the form of a crocodile head, and sometimes by white Ovula shells which are fastened on with strong bindings. The outrigger bears a platform made from battens laid against one another, and another one is attached on the opposite side, rising somewhat obliquely in the air. The people crouch on these superstructures when sailing, or stow their spears or whatever items are being transported. A mast is erected on the bottom of the vessels, forward of the outrigger struts, and held in position by a pole fastened to the outrigger and by ropes stretched fore and aft. The mast has a fork at the upper end, through which runs the rope used for hauling aloft the four-sided matting sail; this sail is made fast between two poles. Large canoes often have double masts and sails. The paddles are of the usual form, with broad, lancet-like blades which are either carved with the shaft from one single stick, or else fastened to the shaft by strong bindings. No canoe lacks a bailer, with an inwardly curving handle. As with both ends of the vessel, so too the fork of the mast is decorated with 161carving, consisting of diamond-shaped grooves and stylised crocodile heads.

The village layout, as I have already mentioned, differs among the three tribes. However, there is little difference in house construction, although the houses of the Moánus are always erected on poles, while those of the Usiai and Matánkor stand on level ground. A further difference is that the Matánkor take greater care in construction, and the village site is cleaner and more tastefully laid out.

The houses of the Moánus are built in rows along the beach, and often out on the reef also, and the village lies completely free and open to the sea. The Matánkor build their villages in the forest, and if at all possible, on steep, near-inaccessible heights and ridges, for greater security. The solid fences surrounding the villages serve the same purpose. This is frequently a double fence constructed in such a way that the inner one surrounds the village proper and the site; the second fence, some distance from the first, encloses a belt densely planted with coconut and betel palms, and bananas. Here the natives’ pigs roam about and they can as little bother the village as they can escape into the surrounding forest. Holes which do not extend to the ground enable entry. The normal dwellings are undecorated huts about 5 to 6 metres long, 3 to 4 metres wide, and seldom more than 3 metres high. The roof consists of sago palm leaves which are bent over rods about 2 metres long and pierced by a thin stick close to the rod to hold them in position. Woven coconut leaves also serve this purpose. The furnishings differ inside the huts depending on whether they serve as dwellings for the women or the men. Common to all are the low, table-like plank beds on four, often artistically carved legs that serve the inhabitants not only as beds but also act as a table. In the women’s house the space is reduced by a frame taking up the entire central space, on which pots, water and oil containers, baskets of food, and all kinds of utensils are piled up, while the taro tubers gathered from the garden, and other kinds of food lie on the floor. The men’s houses are somewhat more roomy because the previously mentioned frame is missing, but hanging shelves or a structure in the middle hold pouches, betel utensils and suchlike and, above all, a great number of spears.

Much greater care is taken in the construction of the bachelors’ houses or, as they should more accurately be named, the men’s assembly houses. The native carpenters have employed their greatest skill on posts, timberwork and roof frame, and individual parts are decorated with incised ornaments and the recurring crocodile head. Bird figures like grotesque, full-sized human shapes or human heads, also occur. These spacious houses, often 40 metres long, 12 metres wide and 8 metres high, up to the ridge beam, contain the trophies of past feasts in the form of lower jaws of pig or cuscus, as well as the finely carved plank beds and a great number of weapons. The property of the tribe is also set out on poles and trestles: bright, glass beads, ironware, looking-glasses, and so on.

It is understandable that the natives, who in their appearance wear so much frippery for show, also place high value on ornaments of all kinds. They vividly remind us of the inhabitants of New Guinea. By laying stress on cleanliness of the body they demonstrate that their outsides are not a matter of indifference to them. The most common decoration is daubing the body with red dye, or painting the face with red, black or white lines and dots over forehead, eyes, nose and cheeks. Necklaces of local white shell discs, replaced in recent times by multiple strings of white beads, are indispensable, as are carefully polished Trochus armrings with incised patterns on the outer side. The youth takes extraordinary care over his hairstyle. The crinkly hair is combed up and curled by a comb that is always close at hand, until it lies like a cloud over the entire head, sometimes carefully parted in the middle. These combs are made with great care. They consist of the ribs of coconut palm leaves laid side by side, their ends stuck into a network of fibres coated with Parinarium glue. This end section is decorated in various ways and brightly painted.

The pierced ear lobes are tightly wrapped with cords of white beads or decorated with discs of coconut; the nose too is not forgotten, for a cylindrical rod ground from Tridacna shell, 18 to 20 centimetres long, pointed below and with incised decoration, hangs from the pierced nasal septum on a string of beads. They also wear an almost complete ring of coconut shell, about 1 centimetre wide in the middle and tapering at both ends, stuck through the nasal septum. Also, the peculiar pattern of tartar on the upper front teeth is regarded as beautification of the face. This tartar deposit is sometimes so thick that it pushes the upper lip upwards and juts out beyond it. The deposit is carefully tended and given a regular shape by grinding and scraping. Chewing of betel seems to favour the formation of this peculiar ornamentation, which is, moreover, apparently a designation of chiefs and influential men.

Besides the already mentioned neckbands we find in conjunction with them a chest ornament, similar to those known on New Ireland in the form of the kapkap. As on New Ireland the ornament consists of a Tridacna disc, but seldom as thin; the rims are always decorated with a triangular ornamentation consisting of fine lines which, because of gathered dirt, stand out black against the white disc surface. The open-work turtle-shell plate that lies on the Tridacna disc is never as finely worked as on New Ireland. The pattern on the turtle-shell plate is occasionally completely irregular. Figure 46, which depicts a number of from both New Ireland 162and the Admiralty Islands, clearly shows the great difference in presentation.

In his dancing the native reveals himself in his full splendour. Not only is the body painting very painstaking, but ornaments are displayed that are never seen in daily life. Particularly outstanding are the armrings, kneebands, girdles and aprons that deserve a more detailed description. Small discs 4 to 6 millimetres in diameter and about 1 millimetre thick, produced from the upper, thick end of a particular small Conus shell, serve as the principal material in the manufacture of these items. They are expert at processing these small discs into armrings and girdles which one has to admit are very tasteful. The aprons made from these discs are quite outstanding. Thousands of these discs are used in the production of such an apron, and consequently they have a not insignificant value in their homeland, so that only rich people or chiefs are able to afford such a luxury. The size of these dance aprons (fig. 66a) varies greatly. They range in width from 15 to 40 centimetres, and in length from 20 to 60 centimetres. The upper end consists firstly of a close bast weave which is in part decked out with bright, parrot feathers; upon this weaving the actual apron is aligned, consisting of rows of shell discs on which supplementary black shell discs, a particular species of coir seed, and various other seed kernels form patterns. Figure 66 will give an idea, better than any description, of the extraordinary care devoted to the manufacture, as well as showing the beauty of the work.

The women too wear an apron in dancing, far less carefully worked than the men’s apron. The women’s apron (fig. 66b), consists of a soft, pliable piece of bark to the upper surface of which tassels of shell discs, coir and other seed kernels and birds’ feathers are sewn at short intervals.

Fig. 66 Aprons from the Admiralty Islands

a. men’s apron; b. women’s apron

The lower edge consists of a row of pendant shell discs with seed kernels on the end. In dancing, one of these aprons is worn in front and another behind, both being held on by a girdle. The young girls and women are expert at performing dainty body movements which set the embroidered apron in a swinging motion, and this seems actually to be the main purpose of the dance, for when the aprons sway gracefully and picturesquely after a particularly successful step, loud cheers break out.

Today this type of apron is rarely found, if not made with imported European material, especially glass beads and bright rags – I might say adulterated and thereby significantly diminished in beauty. The natives do not seem to understand that the blending of European articles reduces the value of their original decorative items; here, too, this preference for European industrial items has arisen from the feeling that all things new are to be preferred to the old, a situation that we can often observe among civilised nations as well.

Finally, the curious penis shell must also be reckoned among the decorative items; covering the glans of the male member in battle or in dancing. This shell is always a medium-sized Ovula ovum, with cross-hatched patterns incised on the outer, white surface. The internal spiral is partially excavated, and the glans and foreskin are squeezed into the fissure thereby formed. This shell is always carried in a small, woven pouch on a cord around the neck or under the arm, by the adult natives able to bear weapons, so that it is always in readiness. Analogous items of adornment are known to us only from St Matthias in the Bismarck Archipelago; on the other hand we find a similar penis covering in New Guinea, although made not from a shell but from a small species of gourd as in Angriff Harbour.

Probably the tufts of hair and other ornaments also belong among the decoration. These are worn on a cord around the neck during war expeditions so that they hang down the back. The tufts of hair are of varying length and have a loop above, through which the cord is pulled. The thick, hanging plait is wrapped round, and the wrapping is daubed with bright patterns; the lower end forms an almost fist-sized tuft of hair. Other neck ornaments are carved out of wood and represent stylised human figures, also crocodiles and crocodile heads, turtles and fish; but the most characteristic is the neck ornament of human upper arm bones or thigh bones, to which the trimmed wing feathers of the frigate bird are tightly bound to one another along the shaft, so that only the joint head of the bone shows. A replica of this ornament is made from a wooden batten similarly wrapped in frigate bird feathers with the protruding end, corresponding to the head of the joint, carved in the form of a human head. I know of neck ornaments that are similar, although in other shapes, only from 163the Solomon Islands, where they are regarded as amulets that protect the wearer against wounding in battle. Perhaps those from the Admiralty Islands are based on a similar idea as well.

Also, mention must be made of the implements used for chewing betel. The lime containers are made as a rule from a species of long pumpkin constricted in the middle, with dark, symmetrical drawings burned on to the yellow upper surface. However, besides these pumpkin flasks one also sees vessels made of bamboo cane, the sides of which are similarly decorated with burnt-on designs. Quite extraordinary care is exercised on the manufacture of the long wooden trowels with which the burnt lime is taken out of the lime containers. These trowels are made from a dark wood with the lower end flattened like a spatula, while the upper end is ornamented with a carefully carved decoration. Here we find the human figure and the crocodile head as the principal motif.

As a sign of mourning for the dead, the closest relatives, both men and women, wear a peculiar head covering, still rarely found among our collections. This head covering, called la, consists of a stiff yet pliable piece of tree bark with a shiny, black resinous coat on both sides. This rectangle is about 25 to 30 centimetres long and about 14 centimetres wide; at each end three black-lacquered, woven bands are attached, with cords at the ends bound together at the wearer’s neck. This headband is frequently decorated on the black surfaces with beads and shell discs in various arrangements. I have come across this sign of mourning only in villages of the Matánkor, and I believe that it is unique to this tribe.

Plate 24 Moánus women from Lalobé with their children

The Matánkor, or as they call themselves in their own language, the Marankol, are, particularly in the manufacture of ornaments of all kinds and in the production of all kinds of carpentry and carving, far superior to the Moánus and the Usiai. They are the people who decorate their huts with carved poles and roof frames, they prepare the large and small wooden spoons, indeed even canoe construction rests mainly in their hands.

The items described above stem in the largest part from the Moánus and Matánkor, particularly the latter, who hand over their articles to the former. We have as yet had little contact with the Usiai. Insofar as I have seen them, during a visit to the pole village of Lalobé, north of the island of Ndruval, where several of them were staying on a visit, they seemed little different in body form from the Moánus, although the physiognomy of a mountain people was strongly pronounced, particularly in the more powerful musculature of the legs and in the broader, more developed chest. In facial features they differed in no way from the Moánus, while their clothing was the same and consisted of a narrow loincloth drawn between their legs. However, this costume is not universal; the Moánus apparently take it off 164in their canoes, and are not always clothed in the villages either.

On the other hand the Matánkor always wear a girdle with a strip drawn between the legs to cover the genitals. Chiefs or people of high rank wear a strip of bark a hand’s breadth wide both in front and at the back, extending from the girdle almost to the ground, a distinction that we also know from several of the Carolines (see, for example, The Caroline Islands page 136, the diagram of a chief from Rúl). In body form there is, at least as far as the Matánkor of the southern islands are concerned, a notable difference between them and the Moánus. Their skin colour is significantly paler, stature is smaller and more slender, the head hair is frequently vigorously curly, in the odd individual even totally straight, and the nose is less broad than in the Moánus and the Usiai. Indeed one also finds the pronounced Semitic nose among them. The Matánkor, who live on the northern islands of the group, are less pronounced in these bodily characteristics, and resemble the Moánus more closely, probably as a result of close intermixing through marriage with them and with the Usiai.

Women’s clothing is basically the same in the Moánus and the Matánkor, and consists of a woven grass apron, uo, rough on the outside, or more accurately two such aprons that hang down in front and behind, and are held together by a girdle. For the Moánus these girdles are made from thin cords that are wound round and round the body, similar to those of the women on Ninigo. Among the Moánus the women’s heads are shaved completely bald; among the Matánkor only partly so. Among the latter, one also finds women with short hair or with a hairstyle in the shape of a cloud, like the men.

The women everywhere are richly adorned with ornaments; their ears are full of the most varied earrings, wrists and ankles are covered by broad cuffs made earlier from discs of local shell, and today from red, blue and white glass beads. Neckbands and necklaces as well as strings laid crosswise over the chest appear to be particularly favoured by the fair sex. The women’s figures are really dainty; the small, delicate hands, which show only slight traces of work, are quite striking. The skin tone is significantly paler than the men’s, probably because the women stay in the huts a lot, while the men roam about in the sunshine at sea. It was not without great difficulty that I succeeded in photographing several groups of women, and for this I am grateful to the influence of my friend Max Thiel of Matupi, who used his full, charming amiability on the native women, aided by copious distribution of tobacco, in order to banish the earlier shyness and withdrawal. However, I am also indebted to the headmen who finally put an end to the resistance of several beauties by a command, although in a less charming manner than my friend Thiel.

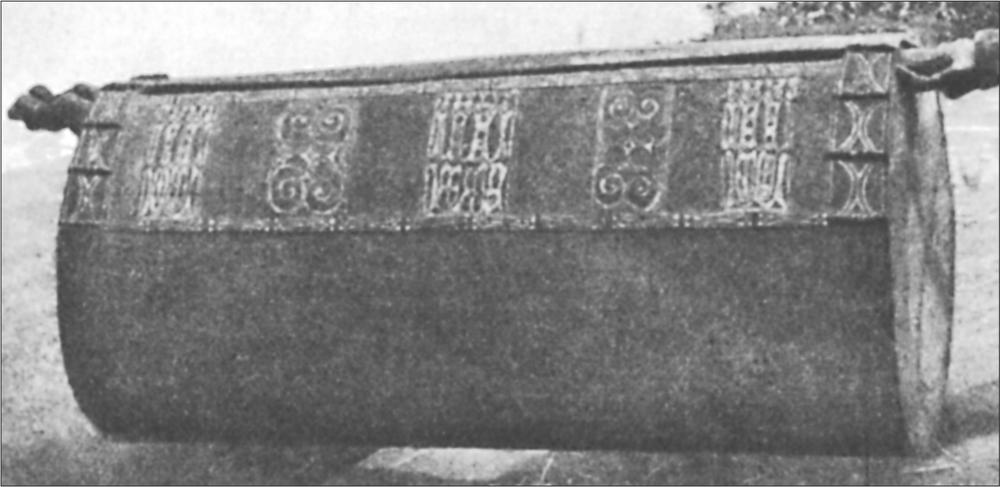

Fig. 67 Drum from the Admiralty Islands

Finally, I must describe in greater detail the large wooden drums (fig. 67), which are found in great numbers in the houses of the chiefs and in the men’s houses. The size varies: one finds small drums 0.5 metres long and monstrous examples 3 to 3.5 metres long with corresponding circumferences. All consist of a single piece of wood, a complete section of a tree trunk which is hollowed out through a long, narrow slit on the upper side. To facilitate this work a circular hole is also made at both ends in the very big specimens, and the inside is hollowed out through these holes. When the hollowing is completed, both holes are closed up through tight-fitting wooden plugs. These drums are decorated, almost without exception, by dainty relief carving, both along the slit and on the side walls; however, characteristically a human figure is attached at both ends as an extension of the slit, in such a way that at one end the head and chest are visible and the legs at the other, while the body of the drum represents to some extent the abdomen of the figure. These figures are either those of a man or a woman. From the explanation given to me in the village of Punro on Lou Island I could gather only that the natives (Matánkor) actually regard the drum body as the belly of a man; unfortunately the sentence relating to this remained unintelligible to me. The tone of the drums, audible over a great distance, is not produced by blows with a stick against the side as in other parts of the archipelago, but by striking with a bent piece of wood about 40 centimetres long. The drummer holds such a stick in each hand, and beats the sides of the drum with great rapidity and skill just below the slit. A drum or signal language is known to the natives. These instruments are also used for dances, and when eight or ten drummers are using all their energy on such occasions, one needs strong nerves to put up with the deafening din.

Some of the photographs accompanying this section were taken in the villages of Punro and Sali on the island of Lou, the same villages visited also by Dr Thilenius. This island is known as the source of the best-quality obsidian (bailo) for the manufacture of spear points. Obsidian is also obtained from both the Poam Islands. It is obtained by mining, when 165deep shafts are dug and blocks are brought up to the surface, from where they are traded to other parts of the archipelago. Blade manufacture is a skill practised by only a few of the natives. On Poam there was only one man skilled in manufacture; in both the abovementioned villages on Lou there was nobody, and we were told that a certain man from a neighbouring village was acknowledged as the craftsman. The blade-maker on Poam gave us a demonstration of his art. After a small block of obsidian had been carefully selected, he gripped it in his left hand and knocked small slivers off one side with a stone weighing about half a pound in his right hand. Then he closed his hand firmly round the block so that the side rested against his palm while his fingers gripped both ends. He gave a sudden, gentle tap with the stone against the outside of the block, and immediately a long sliver sprang off the opposite, free side. With gentle taps this sliver was fashioned completely into a spear tip. Apparently obsidian has a definite fracture plane which the manufacturer knows how to find and to exploit in his work.

It was extremely interesting for me to see a growing kava plant (Piper methysticum), in the village of Lou. The natives appear to regard the plant, designated by the name Ká, as something quite special, and reported that the roots are crushed between stones and the expressed juice is drunk by the men. Thus preparation of the drink is exactly the same as, for example, on the island of Ponape in the Carolines.

With regard to the designations of the various tribes which will be characterised in greater detail in the following passage, I should point out that these are ascribable to the Moánus, who designate all members of their own tribe by this name. The significance of the name is not clear to me. On the other hand, the designation Usiai, which is used by both the Moánus and the Matánkor for the inhabitants of the interior of the large island, seems to be synonymous with ‘tribe’; I draw this conclusion from a remark by the chief of Ndruval, who accompanied us in our boat, and, in response to a question about who might the fishermen be, who were fishing on the reef, answered that they were ‘Usiai Lalobé’ – men or tribe from Lalobé, a large Moánus village on the main island opposite. The word Matánkor means face of the land (mata = face, nkor = land) and might have arisen from this tribe inhabiting especially the islands offshore from the main island. So much is certain, that the Usiai are the original inhabitants, and that the Matánkor immigrated later, perhaps from New Guinea, but more probably from the north, from the Carolines. On the other hand I cannot accurately place the Moánus. In my opinion they are a later migration which, through their intelligence and their battle lust, rose to a dominant position, especially over the much earlier Usiai, while the Matánkor were for a large part in a position to preserve their independence. Then, through marriage and other kinds of intermingling over time, a partial blending took place, particularly of Matánkor and Moánus, although in many cases both have retained their original traditions and customs.

The preceding, as well as the following notes, may well contain a lot of new material. Yet it can give us only a very incomplete picture of one of the most interesting peoples of the archipelago. Only when mission stations have been established in the group and a basic knowledge of the various languages has been obtained, can we hope to make comprehensive conclusions about this part of the archipelago. However, there is no immediate prospect of this. The warlike attitude of the islanders and their hatred of all settlers, who are regarded as awkward intruders, and also the punitive expeditions that often have had to be mounted against the islanders in recent years, will still bear their evil fruit for a long time to come, so that even missionaries are not in a position to establish a firm foothold. A police station for the group is indeed planned, and would contribute much to the pacification of the islanders; however, the economic interests in the group are so small that other areas of the protectorate justifiably deserve preference in this regard.

When I write a description of the intellectual life of these islanders, I have to confess that I am entering quite an unknown area. On my brief visits it was not possible to make detailed studies, although I was successful in carrying out worthwhile observations here and there and gathering a wealth of material. There is always a lingering doubt whether what I recorded was not based on an error on my part, or whether they had not, as is not infrequent in such cases, parcelled up a fairytale to get rid of the troublesome questioner as quickly as possible.

A few years ago the then governor, Herr von Bennigsen made an expedition to the Admiralty Islands on the warship Kormoran, and brought back several of their youths, who were handed over to Father P.J. Meier. One of these youths, the chief’s son Po Minis of the Moánus tribe, showed himself to be exceptionally quick-witted and intelligent. Through him the reverend father obtained very valuable information especially about the Moánus tribe. These reports, which were put at my disposal with the greatest willingness by the recorder, confirmed not only my own observations but offered a great wealth of new and previously unknown material. It is to be regretted that after about two years Po Minis was sent back to his homeland, where he soon relapsed into old habits and finally came back into the hands of the administration, who for punishment exiled him to the government station of Kavieng on New Ireland. I have been able to check parts of Po Minis’s accounts on the spot, and to establish them as in accordance with the truth throughout, so that his collective reports can indeed be regarded as valid.166167

Map 4 The Admiralty Islands

168Po Minis characterised the individual tribes as follows (I present his accounts in word-for-word translation as well as in the original text):

The Moánus build their houses over the sea. The Moánus are expert in canoes, they are expert at paddling, they are expert at propelling the canoes forwards with poles, they are expert at swimming, they are expert with the wind, they are expert at sailing. They are expert with stars, they are expert with the moon. They are expert with the large fishing net. They are expert on spirits, they are expert at sorcery with the pepper leaf, they are expert at sorcery with lime. The expertness of the Moánus is great; their language is only one and the same.

(In the Moánus language this is: ‘Ala Moanus ala asi um cala clati ndras. Ala Moanus ala pas e ndrol, ala pas e pos, ala pas e tone, ala pas e kauënai, ala pas e kanu, ala pas e paleï. Ala pas e piui, ala pas e mbul. Ala pas e kapet. Ala pas e palit, ala pas e kau, ala pas e nga. Ala Moanus pas eala, maudrean; augan eala ndro arai.’)

The Usiai live in the bush. The Usiai are not expert on the sea, they are not expert at paddling, they are not expert at propelling the canoes forwards with poles, they are not expert at swimming, they do not skilfully avoid obsidian spears in canoes. The Usiai are taro growers, they are sago scrapers. The Usiai are snake eaters, they are cannibals, they drink seawater. The Usiai’s bodies are dirty, they have foul breath, their teeth are encrusted with dirt. Their language is different the whole time.

(In the Moánus language: ‘Ala Usiai ala lati lonau. Ala Usiai ala kakau e ndras, ala kakau e pos, ala kakau e tone, ala kakau e kauënai, ala uetaraui pitilou uiau e ndrol poën. Ala Usiai ala mangasawu, ala taiauapi. Ala Usiai ala kauiamoat, ala kauiarawat, ala kauiaüati, ala kulumuandrus. Ala Usiai tjangiala pukaün, puaala porauin, popou i taui liaala. Augan wala ndre arai.’)

The houses of the Matánkor stand on the beach. The Matánkor are expert with the canoe, they are expert at sailing, they are expert at swimming, they are expert with the large fishing net. The knowledge of the Matánkor is not great. They do not know the stars, they do not know the moon, they do not know sorcery with the local pepper leaf, they do not know sorcery with lime dust.

(In the Moánus language: ‘Ala Matankor um eala iti mat. Ala Matankor ala pas e ndrol, ala pas e palei, ala pas e kauënai, ala pas e kapet. Ala Matankor pas eala maudreau poën. Ala ue pasani pitui poën, ala ue pasani mbul poën, ala ne pasanis kau poën, ala ne pasani nga poën.’)

I will add further explanatory comments to this characterisation of the individual tribes.

The Moánus. They navigate both on land and sea by the stars. Also, the time of the arrival of both predominant winds, the north-wester and the south-east wind, is recognised by star positions. When the Pleiades, tjasa, appears on the horizon at nightfall, this is a sign for the beginning of the north-west wind. On the other hand, when the Scorpion, pei (= stingray), and Altair, peü (= shark), rise into view at the beginning of twilight, this is an unerring sign for the imminent arrival of the south-east wind.

The headmen especially, are informed in star knowledge, by tradition.

The three stars which make up Orion’s belt are called: Ndril en kou (= line fishing canoe), because they resemble the three men who are usually occupied with line fishing in a Moánus canoe. (The canoe used for fishing with the large nets is called ndril en kapet, and the war canoe is called ndril en paün.) When this star pattern disappears on the horizon in the evening, the south-east wind sets in strongly; this is also the case when the same star pattern is visible on the horizon in the morning. This time of the year bears the name kup tjulan tjasa. When the ‘line fishing canoe’ rises in the evening, the rainy season and the north-west wind are not far off. The star pattern of Canis major is called manuai (= bird). When this star pattern is aligned so that one wing points north while the opposite one is still not visible, the time has come when the turtles lay their eggs in the sand, and many natives set out for the Los Reyes group, three uninhabited islands that are particularly sought-after by turtles. The western island is called Towi, the centre one is named Mbutmanda, while the eastern one is Putuli.

The Milky Way is named sauarang (= daylight). The evening star is called pitui an kilit (= steering star). At sea they can navigate easily by this star.

The three stars of Aquila, with Altair in the centre, are called pitui an kor (= land star). The Corona is called pitui an njam (= mosquito star). When this star pattern is sinking, mosquitoes enter the houses in swarms. The two largest stars of the Sextant are called pitui and papai. When this star pattern is visible in the early morning, the time is favourable for catching the fish called papai.

Dorado is called kailou (= a species of fish); the Aurora Australis has the name kapet (= net).

The Moánus name the seasons of the year according to the position of the sun. If the sun is north of the equator, the season is called morai im paün (= war sun); war is conducted against enemies especially during this time. When the sun stands over the equator the period is called morai im kauas (= friendship sun); this is the time of peace and reciprocal visits. When the sun turns to the south the colder season begins, morai im unonou. 169

They observe the moon especially for catching fish, since at the arrival of the different phases of the moon particular fish species predominate, and they set about catching them.

Compass directions are known to the Moánus, and they differentiate kup (= east), ai (= west), lan (= south) and tolau (= north). It is astonishing to see the confidence with which they are able to orientate themselves at any time of the day; the sun serves as their reference point, and after observing it for a short time they give the various compass points precisely.

The above may be sufficient to demonstrate that the Moánus do not boast gratuitously: ‘They are expert on stars, they are expert on the moon.’

But the Moánus also assert: ‘They are expert at witchcraft!’ They believe in numerous spirits and say that with their help they can do all kinds of things. A benevolent spirit plays a major role in the life of the Moánus, and he is called upon in all kinds of danger, distress at sea, during battle, in sickness and calamity. The following invocation at a time of war will serve as an example. The chief sticks a pole into the ground and takes up a position a short distance away, holding a sago loaf in his hand.

Papu! Abulukau coi ito! Ko njak kiene ndrita mbulukau oïo! Ko taui mbulukal eïo ki ta on e kei ito, konowa io, io u ta on e ala rawat! Mbulukal eïo i ne ta on e kei poën, ioia lau oio, ioia ne la ta on poën.

Translation:

Father! See here the sago loaf belonging to you. Come here to my sago loaf! Let it be that as my sago loaf strikes this pole, I, I will strike men in the same way! If my sago loaf does not strike this pole, then I and my people will not be struck either.

Sorcery, called kau, is practised before a battle, to ascertain whether an attack is in fact advisable. A betel leaf is rolled up, a piece bitten off and chewed with Areca nut. The spittle is allowed to flow in the roll, which is then opened. According to the path of the spittle they decide either for or against a battle. If the spittle flows over the middle of the leaf the battle takes place immediately; if it flows to the right it is also a favourable sign, only they must wait a while; should it flow to the left, this signifies a disastrous outcome.

Another means is the sniffing of a pinch of lime dust (nga). If this causes an urge to sneeze, battle commences; if not, the warlike undertaking is dropped.

The Moánus say that the Usiai are far superior to them in number, but they are without cohesion among themselves, compared with the Moánus, who unite at least in critical moments. Their fragmentation is the reason why they are always held in subservience to the Moánus. However, the state of war is not permanent but restricted, as we have seen earlier, to a certain time of the year. Outside this period they trade and visit reciprocally for dances. Both Moánus and Matánkor marry Usiai maidens, and this situation of relatedness has the effect that certain Usiai become permanent allies of the Moánus and Matánkor. The Usiai are skilled warriors, but they always fight from ambush, and do not love the open, front-on attack like the Moánus.

The war ends when either party has at least one dead and the defeated party offers gifts of friendship. Should the gifts be rejected this is a sign that revenge is sought, and the battle becomes prolonged. This situation lasts until either party runs short of food, for obviously the gardens cannot be cultivated during war.

Prisoners can buy their freedom; however, if they do not have the means, they are made slaves (tapo).

The Usiai live in isolated tribes, frequently in enmity among themselves. This fragmentation consequently gives rise to a great difference in Usiai languages.

In their gardens the Usiai cultivate taro, sugar cane, bananas and sago. Yams are grown by the Usiai only on Palual (St Patrick Island) and Rambutjo (Jesus Maria Island).

The Usiai make carrying baskets or pouches, girdles and armlets out of plant fibres, and trade them to the Moánus. They also prepare the large, unbreakable oil containers out of wickerwork, but do not know pottery, which is made only by the Moánus.

For currency all tribes use shell money made from small, round shell discs that are prepared particularly by the women on Sóri (Wild Island). Recently women have introduced the manufacture on Haréngan (D’Entrecasteaux Island) too, and on Papitálai.

The dances of the Usiai do not have great variety. The two principal ones are the following.

If an Usiai presents another with a pig, he takes ten lances, nine in the left hand and one in the right or should they be heavy, four in the left and one in the right. The dancer capers on the spot in an increasingly rapid rhythm, to the sound of the wooden drum and when he stops he hands over the lances to the presenter of the pig.

Besides this solo dance they also perform a group dance, in which many people take part. All trip round in a circle holding lances in their hands. In the centre stand two lead singers who accompany their song with drumbeats. When the dance has ended, all the lances are laid together as a gift for the organiser of the feast. The women hold mother-of-pearl shells in their hands instead of lances.

For the dance the Usiai twist their long hair together into a plait at the back, and decorate it with bright feathers. Like the Moánus, they also put on the penis shell.

The method of burial among the Usiai is, briefly, 170as follows. The body is placed in a sitting position and decorated. When this is completed it is laid out in the hut until putrefaction occurs. About three days after death the body is buried inside the hut, and the women keep a vigil on the grave for months, wailing loudly for the dead person.

The Matánkor are, as we have seen in their characterisation, a link between the Moánus and Usiai. The word Matánkor means: face of the land, beginning of the land; the opposite is kaleüiankor – that is, tail of the land, land’s end. Similar juxtapositions with kor (land, village), are found in palankor, head of the land, tongue of land; kinkor, receptacle of the land; ndruankor, back, reverse side of the land, which looks out on the open sea; londriankor, midland; mburunkor, end of the inhabited land, and so on. The Matánkor mainly inhabit the islands that are off the main island in the north, as well as several islands in the south. Their villages are situated sometimes on the beach, and sometimes on steep mountain slopes for security.

The Moánus inhabit the following islands and locations. A crown of Moánus villages extends along the southern side of the main island. Dr Schnee, in two papers entitled Beitrag zur Kenntis der Sprachen im Bismarckarchipel and Über Ortsnamen im Bismarckarchipel, has given valuable contributions to the knowledge of the land. It is excusable if minor errors, which can creep in all too easily, appear, especially in the case of language and place names. According to this the main island is called Tschebamu by the Moánus (that is, bush, forest); actually the word is Tjawómu and is the designation of a mountain ridge visible from a great distance (see later, in the stories and legends). In a Moánus song the main island is called Patánkor; that is, tribal land. The designation is pictorial, and indicates a tree trunk; the main island is regarded as the trunk of the tree and all the surrounding islands are accordingly called ngaronkor = root lands, roots of the land. Often the Matankor name the main island simply kor. The word taui is a misinterpreted Moánus word, and means: to lay down, to bring, to give, and is not a designation of the main island.

Moánus settlements on the south coast are:

Fig. 68 Lalobé pole village of the Moánus tribe

Lómpoa (lon, interior, centre, poa, hollowedout coral rock), not Lomba. The Lómpoa coast is occupied by mangroves and is not suitable for agriculture. There are no coconut palms there; the people live exclusively from fishing, and barter for their other necessities with fish.

Mbúnai or Ponai – that is, sea cucumber; similar to Lómpoa.

Tjawompitou = land source of the pitou (Calophyllum) which grows here in great numbers. The soil is better, and coconut palms occur.

Pére; that is, ‘my brain’. The name is based on the inhabitants’ custom of bringing home the heads of fallen enemies. They are smashed on stones and the brain removed. The Pére are a strong tribe and have numerous warriors.

Patúsi (solitary rock, pat = rock, si = one), not Pedussi. The name comes from a single, soaring rock. The coast is covered with mangroves, and the inhabitants obtain food by catching fish. Since fishing is almost the sole source of income for all these villages, this has led to a precise delimitation of the fishing grounds. Trespassing on neighbouring grounds not infrequently leads to hostilities.

Lótja (middle of the mangroves) a small tribe who likewise live by fishing.

Poauárei = mouth of the Uarei river (poan = its mouth, uarei = the name of the river; the word uarei is compounded from uai = water and rei = a freshwater fish). The designation Páure is based on misinterpretation.

Tjápale; that is, what kind of sail (tja = what, pale or palei = sail), not Tschábe˘le˘. The inhabitants of Mbúke have introduced pottery here and this, besides fishing, is the source of income for the inhabitants.

On the north coast of the main island are the following Moánus settlements:

Papitálai = sand of the eel (papei = sand, talai = eel). This was earlier a Matánkor settlement called Teng. The tribe was almost wiped out by war and sickness, and the Moánus from Mbunai finally bought the site and settled on it.

They intermingled with the survivors of the original inhabitants and the result is their somewhat different language. The Moánus cultivated the site, so that today it is fairly important and the chief, Po Sing, had a widespread influence until his death not long after. Papitálai’s enemies are the Matánkor who live in Loniu, Lomboerun and Pitilu. Dr Schnee believes he has heard the name Kalobössen used for Papitálai. This might have arisen through misunderstanding; he probably means: Kor e Po Sing = village of Po Sing.

The islands inhabited by the Moánus are:

Siwisa (not Sepessa), the middle Fedarb island. It is rich in betel palms and also has stands of coconut; the inhabitants are disinclined to gardening, but catch fish and have a vocation as canoe builders. The uninhabited rocky island, Tjókua, with its few coconut palms and good fishing grounds also belongs to the Siwisa people.

Lólau = surreptitious, because the Moánus of 171Siwisa attacked the Matánkor there at night time, killed them and drove them out. The island has good stands of coconuts and the Siwisa exploit them.

Kéa = a species of tree; this is the fourth of the Fedarb islands and is separated from Lólau only by a reef. The four Fedarb islands have the group name Ulu = spring tide, in memory of one that inundated the islands years ago and caused many drownings.

Ngówui (Violet Island). The name is a pictorial representation of the word Mopui = citronel grass, which grows here in great abundance; otherwise the island is completely covered in coconut palms.

Paláia = landspit where people bathe, so named for a favourite bathing spot.

Ndréü = a shoreline tree; on this island (Berry Island) signs of the abovementioned flood are clearly visible because it destroyed almost the entire stand of coconut palms.

Uainkatou = water of Katou (uai = water; Katou was the name of the last chief of this island). The island is also called Polot, lot = ulcer; this is an abusive name for Po Katou, who was covered completely with sores.

Kumúli (Broadmead Island); the word is derived from ku = a fragrant ornamental plant, mari or mali = to spit. The plant in question is chewed and spat out for the purposes of sorcery.

Móuk = a species of tree; the designation Mokmandrian is a European invention.

Takúmal. The name Mok-lin is likewise an erroneous designation by Europeans. Both these islands are inhabited by a single tribe. The population is numerous, and there are a large number of children. The men of Móuk are skilful fishermen and warriors; they were the people who killed the trader Maetzge years ago. They conduct warfare with Siwisa, Ndriol, Polótjal and with Pálamot (the latter three are on Rambutjo (Jesus-Maria Island), and also with Lóu (St George Island) and Mbúke (Sugarloaf Island). Earlier, the island of Alim (Elizabeth Island) belonged to the Móuk people. This island was taken from them as punishment and given to trader Molde. It is densely covered in coconut palms.

On Rambútjo the Moánus have two colonies: Ndriol on the eastern side and Pálamot on the southern. Ndriol was earlier a large settlement but was heavily attacked by the people of Pak (San Gabriel) and lost many people; a remnant sought refuge on Patúam, the outermost of the Horne Islands, but were taken by surprise and killed there too. Pálamot, situated in a mangrove swamp like Ndriol, has a large population. Pálamot people settled years ago at Limondrol on Papitálai. Their chief Kámau was the instigator of the attack on the sailing ship Nukumanu, the crew of which was murdered. The Pálamot people are competent fishermen; the women are skilful at making canoe sails. The island of Tiliánu (San Miguel) also belongs to the Pálamot people.

Plate 25 Matánkor women of the island of Lou. A number have mourning bands round their heads

The Moánus from Papitálai claim the three uninhabited Los Reyes Islands: Towi, Putúli and 172Mbutmanda.

Mbúke = Mbúkei = the Tridacna shellfish. Besides Móuk this is the most populous of the Moánus colonies. The island is rich in coconut palms and is named Sugarloaf Island by the whites, on account of the mountain which rises to a considerable height in the middle of the island. The mountain provides clay for pottery. Mbúke is on a war footing with Móuk, Ndrúwal and Haréngan (D’Entrecasteaux Island). The inhabitants of Sisi are their allies. In recent times, out of fear of the whites, many Mbúke people have settled at Malai Bay on the main island.

Ndrúwal = pole of the cousin (ndru = pole, wal or walwal = cousin, relative). Two cousins settled there and built their houses. Strife developed between them and in a rage one demolished the poles of the other’s house. The island has few coconut palms, but on the other hand many pandanus, from which excellent canoe sails are produced. The name Rubal (Green Island) is incorrect. Alongside Ndrúwal, from which it is separated by a narrow strait, lies the island of Tjovondra, where a Moánus settlement also existed earlier.

Ndrówa = only rock (ndro = only, wa = pat = stone, rock); the Ndrówa people only catch fish, but they had to flee from the people of Pere and Pak to Mbúnai. On the map it is named Dover Island.

I now come to the dwelling places of the Usiai. They inhabit the whole interior of the main island. On the south side they live near the beach, and a sign is given to them by a canoe sail, upon which they hurry down to the shore. On the north side they are further inland, from where they are summoned by the Triton horn and the big drum. The land of the Usiai is the abode of spirits, and two places in particular are well known in this connection. One place is the uninhabited gorge Ndrótjun (tjun = a species of tree, ndro = only, exclusively) and lies inland from the island of Réta. The other site is called Latjeï and lies inland from Sanders Point. The Usiai also inhabit the large island of Palúal or Paluar (St Patrick’s Island). They are known as yam cultivators and for the manufacture of hair combs. They are almost always at war among themselves but are on a trade footing with Móuk.

Rambútjo is also inhabited for the most part by Usiai who cultivate bananas and yams. In their district lies the spirit home Limbúndrel = end of the ladder (lin = his end, mbundrel = ladder), because steps hewn into the rock lead down into the gorge.

Ndrótjun, Látjei and Limbúndrel are therefore the three dwelling places of the spirits, to which is added Tjawórum in the vicinity of Lóniu where, however, only benevolent spirits stay.

The first three places are gruesome beyond imagination. They are situated in the mountain solitude – yawning abysses whose perpetual darkness cannot be penetrated by the sun. Here live the evil spirits. The foremost of these is called kot, distinguished from the other spirits, ala palit. It does not wander on the ground but flies through the air and spreads a fire glow around itself. The kot is eternal and unchanging; the only one of its kind. The ala palit are recruited from the spirits of dead Moánus, Usiai and Matánkor. Chiefs and rich men and all the bad people as well, come to these gruesome places after their death. The chiefs and rich men are taken by the evil spirits because they envy them their wealth. Now their revenge comes after death; they set before them only the excrement of men and pigs as food, and they must be happy with this if they do not want to be completely destroyed by the spirits.

The bad people, the liars and murderers, are taken by the spirits for punishment for their evil deeds.

If a chief becomes ill, it means that the kot or palit has kidnapped his spirit. In fantasy the kot is seen during the night, wrapped in firelight. They then summon the sorcerer, who has to bring the spirit of the sick man out of hiding; the fire in the house is put out and the spirit is attracted with gentle piping. The sorcerer now attempts to interrogate the kidnapper of the spirit, and if this succeeds the illness is cured. However, if the evil spirit has irretrievably kidnapped the spirit of the sick person so that even the sorcerer cannot bring it back, then the sick person is got rid of by the neighbours. Whoever acquires the evil spirits has an uncertain chance of survival, for they can completely destroy him and eat him; or they may tolerate him. The Moánus experiences the latter when he hears the spirit of the dead person gently piping in the house of a relative, especially a son; the spirit is thereby proclaiming himself as a protective spirit of the son or relative, they too can rely on this protection should they be taken by evil spirits after death.

Whoever comes to the benevolent spirits in Tjawórum is not subjected to the danger of annihilation. The spirits in Tjawórum must claim the spirit of the dead man; if they do not come quickly enough, the evil spirits step in and eat up the spirit of the dead man. Thus, during an illness a rivalry develops between good and evil spirits; a relative of the sick person strikes the wooden drum and summons the benevolent spirits.

When the kot flies through the air laden with the souls of men he is heard clearly when he hurls them into the ravines, for a noise like thunder arises. When many souls are thrown down, the noise lasts a long time.

The dwelling places of the Matánkor on the main island are:

Teng, merged into one with Papitálai, but built on the shore while Papitálai stands on the reef.

Lóniu = middle of the coconut palms. The Lóniu call their site Bárakou; the population is very large and they own many coconut palms, besides being 173keen gardeners. Polygamy is in their blood, and the number of children is great. The name Kaloboubou is an incorrect interpretation and should be called Kore e Po Pau (Po Pau is the local chief). The island of Potomo (Bird Island) in the Matánkor language, or Popapu in the Moánus language, belongs to Lóniu. In the bay lie several small, uninhabited islands visited when catching fish; they are called Ndrúwiu and Tjuándral.

Pongópou, in the Moánus language Pongopong, a species of sea grass. The number of inhabitants is small; agriculture is their main occupation. The people are connected with Papitálai. In Pongópou is found a grove of the forest spirits, kasi. They live in trees, and are not well-intentioned towards men, entering their bellies to eat the entrails. The site Kintjáwon belongs to this settlement.

The Los Negros Islands belong, with one exception, to the Matánkor. They inhabit the following islands:

Korónjat = land of the njat tree (kor = land, njat = an apple-like fruit).

Ndrilo = noise, produced by coconut palm leaves being dragged through the water.

Háuai in the Moánus language, Hóneï in the Matánkor language. A few years ago the population retreated to Pitilu, driven out by the people from Hus, who had recruited assistance from Sisi and Haréngan. At this time the stands of coconut were for the most part destroyed.

Pitilu in the Moánus language, Pitjilu in the Matánkor language. The population is large but is split into two warring factions. The people from Lúhuan (the western part) and Poekálas (in the centre) fight with both the eastern sites of Pahakáreng and Ndrel; they only come together during the time of dances. Fishing is the main occupation and they barter for their other needs from the Usiai with both fresh and smoked fish. Shark-catching is a specialty of the Pitilu people. The period of shark-catching is called morai im peü = time of the shark, or morai in kup = sun in the east, sunrise. The wind is then strong, and tree trunks that had come ashore in the north-west wind, are driven back into the sea. Many small fish gather round these rotting tree trunks, a dainty morsel for the sharks, which swim close to the surface following these drifting tree trunks. Numerous canoes then set off on the hunt. The smaller sharks are simply caught by hand, the larger ones on a hook. Like the Pitilu people, the people of Hus, Andra, Ponam and Sori also catch sharks.

The Pitilu are recognisable because they paddle noisily; that is they strike the paddle against the side when dipping it into the water. The Moánus paddle noiselessly, dipping their paddles into the water without touching the canoe.

Burial is roughly as follows. The body is buried the day after death has occurred. The corpse’s forehead is painted red, and a red stripe runs across the cheeks; the hair is powdered red. Armrings decorate the arms and shell money is laid on both sides of the corpse, to be distributed among those present at the burial. Then the body is wrapped in pandanus mats and buried in the hut.

The Moánus are the middlemen for the Pitilu, and procure canoes for them as necessary, particularly from Polótjal on Rambútjo. Similarly they procure blocks of obsidian from Lóu. As a separate product the Moánus sell their earthenware pots to the Pitilu. The Moánus buy nothing from the Pitilu, nor do they buy any wives who do not have the greatest reputation; on the other hand, Pitilu and Usiai intermarry. On the whole the Moánus look down on the Pitilu with a certain contempt. They throw at them their everlasting bartering and lazy lifestyle which does not lead to establishing gardens. They also make fun of them because of their cannibalism. The Pitilu retort that they do not regard the flesh of the Moánus as succulent, and taunt them that they have bald heads, whose hair has been burnt by the sun and that they are lovers of the cadaverous smell.

The following islands belong to the Pitilu:

Mándrindr = a species of tree with edible fruit; the island is uninhabited and is avoided by the Moánus because of its many snakes.

Réta = Moreta, in the Moánus language the betel pepper leaf. The island is very rich in betel pepper and also in wild pigeons.

Mbutjoruo (mbutjo = small, uninhabited island; ruo = two), two small mangrove islands that are used as fishing grounds.

Hanita is the island between Pitilu and Hus. It is uninhabited and belongs to the latter.

Hus has a dense population of fisherfolk. The inhabitants are also potters, and collect their clay requirements from the main island. Their trade with the Usiai is very active.

Andra is also heavily populated. They fish and make shell money. The small island of Papimbutj to the east, which is covered with casuarinas, also belongs to Andra.

Pónam in the Moánus language and Poném in the Matánkor language; this is the dwelling place of a kind of forest spirit named ngam, which are very similar to the kasi, and behave towards men in the same way as the latter. The Pónam, Hus and Andra people are deeply involved in ngam sorcery. In the centre of Pónam stands a large house from the roof of which hangs a big wooden basin and with Dracaena bushes around. If the Pónam want a stranger slain, they lead him into this house and entertain him, but surreptitiously add ngam potion to the meal. On his return to his home territory, death ensues. The ngam usually live in trees, and are only called into the house occasionally, when the sorcerer wants to use them. 174

Sori (Wild Island) in the Moánus language, Sóhi in the Matánkor language, is well populated. Here, in particular, manufacture of shell money is carried out, a principal task of the women. The Moánus trade the shell money for the following items:

- Ready-made obsidian spears. They pay

- fathoms of shell money for ten spears.

- Coconut oil. A large container of coconut oil costs 30.5 fathoms.