V

The Western Islands

Under the designation ‘western islands’ I am including the little islets and island groups which lie west of the Admiralty Islands. Starting from the west they are as follows: Matty or Wuwulu, Durour or Aua, the l’Echiquier Islands or Ninigo, the Hermit Islands or Luf, also called Agomes, and the Anchorite Islands or Kaniet.

We begin with a description of the first two islands, which belong together geographically and ethnographically.

1. Wuwulu and Aua

Both these islands lie about 40 nautical miles apart, the first at 1º43.5’S latitude and 142º50’E longitude, the second at 1º26’S latitude and 143º10’E longitude. Both are low coral islands rising only a little above sea level but covered with fairly rich vegetation. Apart from the undemanding coconut palm which is present in significant stands, we find the characteristic beach flora of the South Sea islands and also the breadfruit tree and banana, as well as taro plants. As a result of this rich plant growth, a deep humus layer has built up over the years on the coral banks, so that the inhabitants are in a position to cultivate a sufficient number of food plants. Thus they are not, as on numerous other coral islands, totally dependent on the coconut palm and fishing. However, from time to time a noticeable lack of food occurs so that the daily rations have to be reduced to a minimum.

Neither island offers an anchorage; from the edge of the fringing coral reef the undersea walls of the island fall steeply into the depths, and just a few boat lengths from the reef no bottom is to be found at 200 metres.

Until several years ago the inhabitants of the islands were totally unknown to us. Since their discovery by Carteret they had only been visited occasionally by passing ships, and these left us no reports about contact. In the mid-1890s the steamer Ysabel called at the island, and the horticulturalist Kärnbach, who was on board, gathered a number of weapons and implements that were offered for sale, and these reached the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin. Professor von Luschan recognised immediately the uniqueness of the acquired items and drew attention to them for the first time in the International Archiv für Ethnographie. Consequently the island was visited more frequently and the firm Hernsheim & Co. set up a trading station on Matty in 1897. However, the trader posted there was killed after a short time. The reason for this is still not clear; however, one might only suspect that he had sealed his own fate.

In June 1899, I had the opportunity of visiting both islands for a few days and was able not only to make a number of observations on the spot, but also to take a series of photographs, some of which were published in Globus (vol. LXXVIII) and others in the Papua Album, volume II.

Since that time our knowledge has had no significant increase, in spite of the firm having stationed a trader on Matty again in 1901. From an approximately fourteen-year-old boy from Wuwulu who came to the Bismarck Archipelago in 1902, I was able to find out the names of the various ethnographical articles as well as obtaining more detailed information on their use. Other accounts of the items in question must be taken with circumspection on account of the lack of knowledge of the language by both parties.1

Before the decimation of the natives mentioned in the footnote, both islands were fairly densely populated. Aua had about 2,000 inhabitants, and Wuwulu about 1,500. Although contact took place between both islands, for the most part this was said to be hostile. The Aua people, because of their greater numbers, seemed to be a threat to the inhabitants of Wuwulu, whom they not infrequently attacked, especially when, on their own island, food supplies were fast becoming exhausted. Since the establishment of a trading station, the natives of Wuwulu have enjoyed greater security, because the Durour people have discontinued their raids for fear of the white trader. The natives of Ninigo, about 75 nautical miles to the east, communicate occasionally with both islands. The Ninigo people are very

184similar to the Matty islanders in many ways. Between Ninigo and Durour there is a smaller island, named Allison Island on the maps, which has been settled by a colony of Ninigo people.

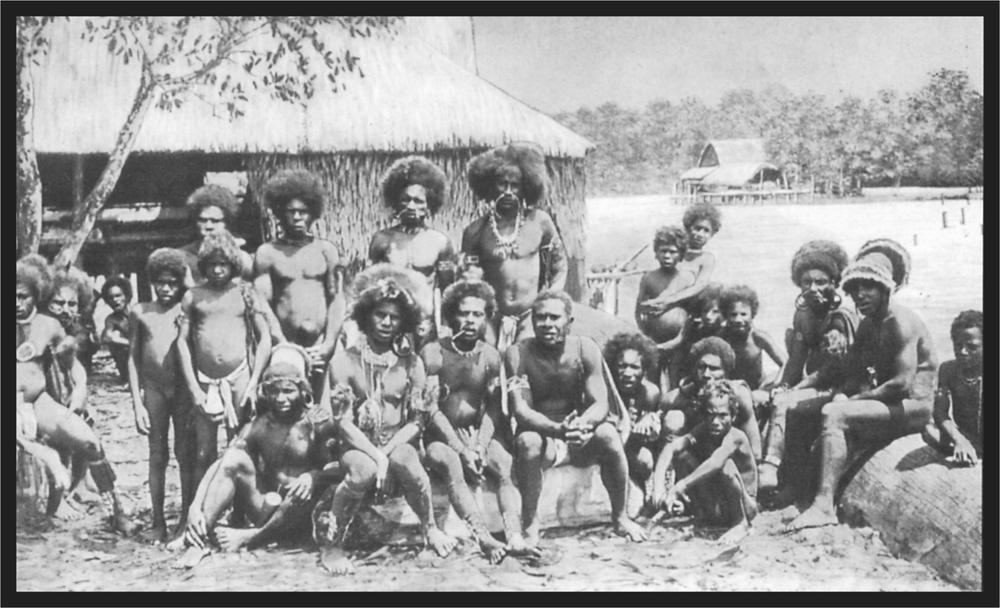

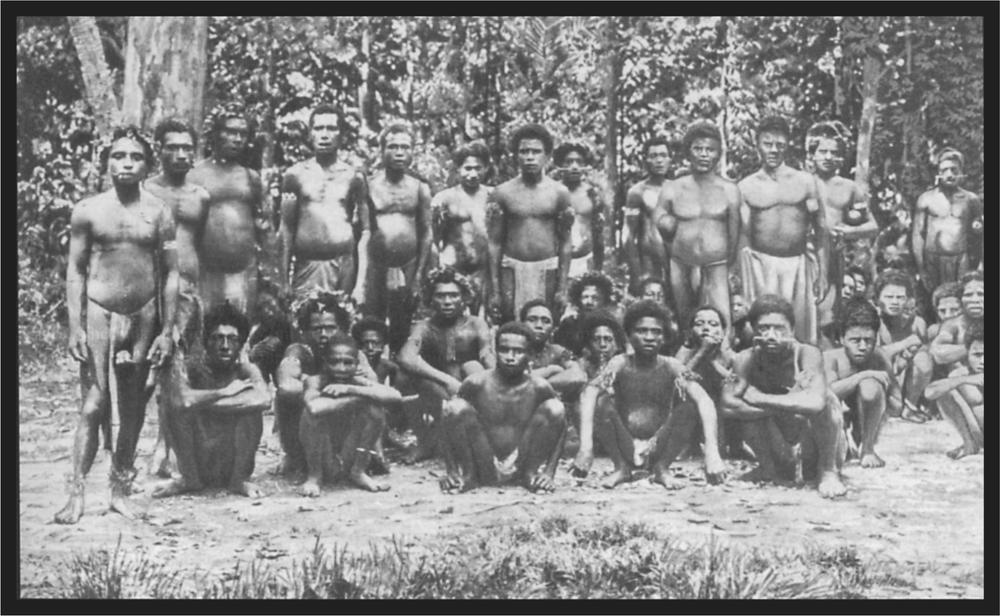

Plate 27 Men of the Moánus tribe from the village of Lalobé

The inhabitants of Aua are without doubt the stronger and healthier. On Wuwulu one is already aware of signs of an incipient tribal decay. Elephantiasis is quite common here, and also skin rashes and unpleasant wounds, especially on the face and the lower extremities. While painstaking cleanliness predominates on Aua, on Wuwulu they do not seem to value cleanliness particularly, neither with regard to their bodies nor their dwellings and surroundings.

Otherwise the population of both islands is probably one and the same. Bodily appearance, language, traditions and customs, dwellings, weapons and implements are the same, although, with regard to the latter, minor differences exist. In all that the islanders manufacture they show an extraordinarily well-developed technique; one must involuntarily be astonished at the very precise shapes of all items there, and at first glance be inclined to assume that their working tools must be highly developed. Yet this is not the case, as I shall point out later when describing them. Sadly there occurs here too, as everywhere else where the natives come into contact with the whites, a rapid decline in artistry. Already on Wuwulu, for example, items are being made which are only rough imitations of the earlier, accurately produced objects. They have sold the old things, the white man brings new and practical implements, and soon these replace all that was characteristic. The beautiful objects which are now the decorations of our domestic museums, will within a few years belong to the rarities and antiquities in their own homeland.

I would not be wrong if I present the population of both islands as a branch of the Malayo-Polynesian tree spread so widely over the South Seas, and standing right next to that division that we give the general designation ‘Micronesian’. The skin colour is that of the Samoans, a pale brown; the hair is smooth or wavy and curly; the facial features are agreeable, and in numerous individuals regularly formed and matching the claims of our European idea of beauty. The men are slenderly built and of medium size; the women as everywhere else are somewhat smaller but universally have, especially in their youth, elegant, well-rounded forms, well-built limbs and extraordinarily delicate hands and feet. In facial features a slight prominence of the cheekbone is noticeable, as well as slanting of the eyes. Several natives have these characteristic features strongly developed, to such an extent that one could quite easily mistake them for Malayans.

The eyes are lively and intelligent, and the whole attitude of the people indicates a high level of intellectual capacity. Their movements are quick and lively, and their speech is accompanied by gesticulations with hands and arms.

How long these islanders have occupied their present location is difficult to determine. We might certainly assume that they have emigrated 185from the Indonesian islands. Of course the New Guinea coast is only 87 nautical miles away, but the first glance by the most superficial observer shows that our islanders have not the slightest thing in common with the Papuans. Several weapons, especially the long, broadsword or halberd-like striking weapon recalls in a surprising way, as Herr von Luschan maintains, an old, Chinese, iron weapon. Possibly these forms are imitations of iron weapons that arrived here through shipwrecked Chinese seafarers; possibly they are copies of earlier weapons which were common in their original homeland, but because of a lack of the necessary material in the new land they were copied in wood. Imitations of modern axes and long knives are now very common since the islanders became familiar with these objects a few years ago, and they are copied so skilfully that even at a short distance they would deceive the most careful observer. Perhaps on closer acquaintance we will succeed in drawing a conclusion on the origin of this interesting little group of people, from legends perhaps, and on the basis of comparative language studies.

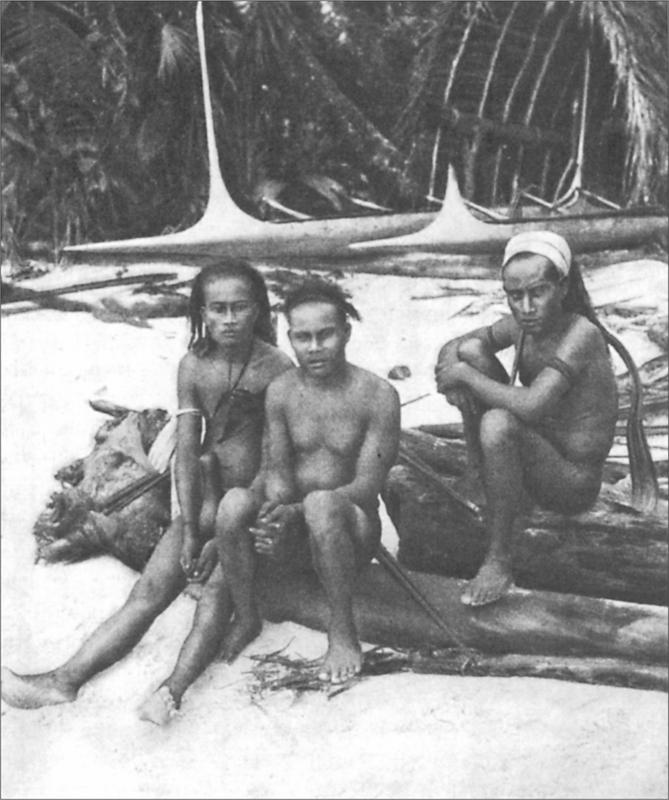

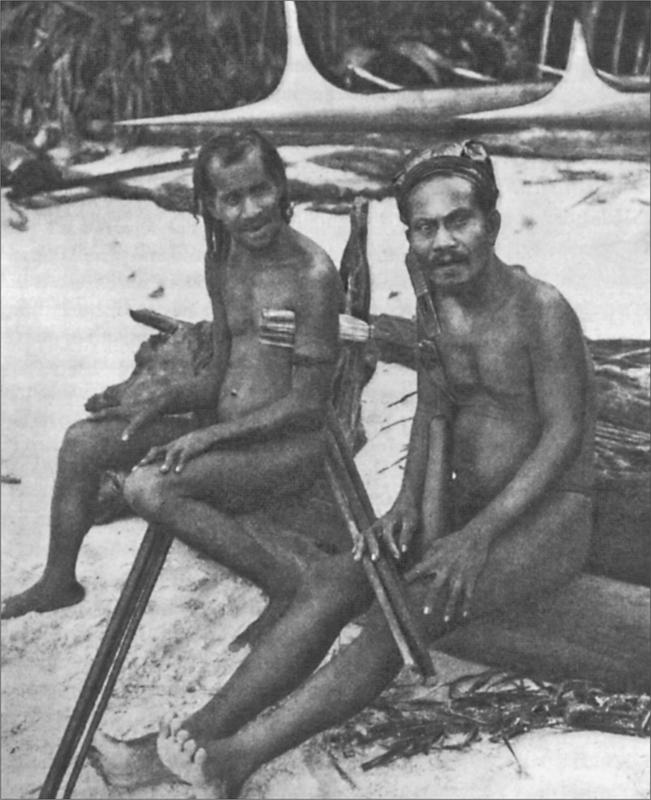

Fig. 69 Youths from Wuwulu

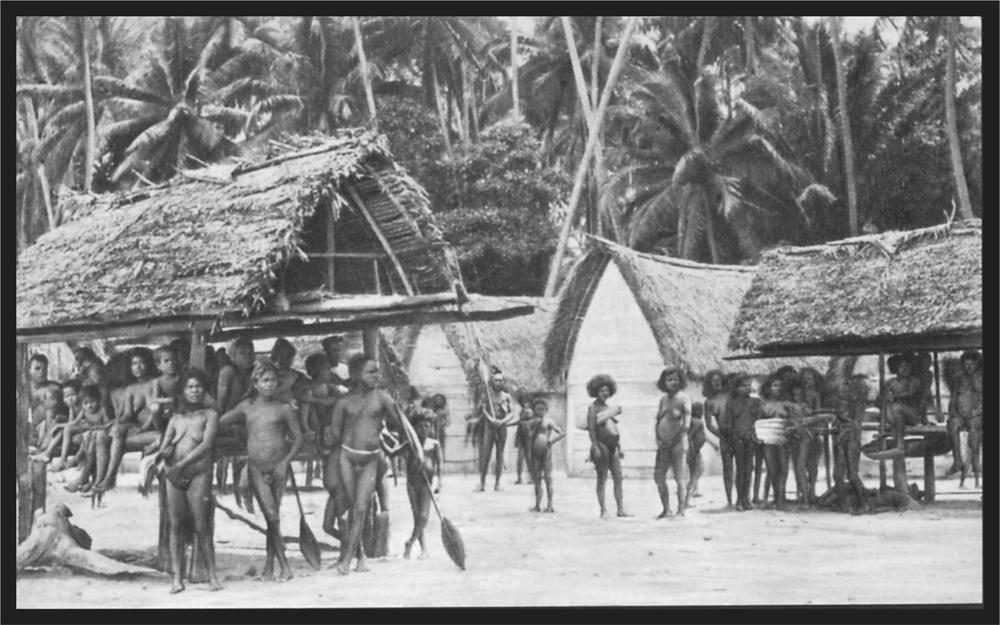

During the visit to both islands the carefully constructed houses of the natives (plate 29) stood out from a long way off. On Aua the entire population is settled in a large settlement which bears the same name as the island. On Wuwulu the houses are gathered into several separate villages. The dwelling houses, waloea, are rectangular wooden structures of varying size; the smallest are about 4 metres long and 2 metres wide, the larger 7 metres long by 3 to 3.5 metres wide. They are built directly onto the ground without an underframe or foundations. Construction is as follows. The four corners consist of four upright, cleanly cut and smoothed rectangular posts. The walls are built from wooden boards prepared with the stone axe to be about 20 to 30 centimetres wide and 5 to 6 centimetres thick. The walls are pushed into the grooves made in the corner posts, and are fashioned so precisely that the edges tightly abut one another. Hard wooden pegs serve for further fastening, connecting the ends of the wallboards to the corner posts. The walls are 2 to 2.5 metres high; the gable ends are raised further vertically in the same way as the side walls. The roof consists of plaited coconut palm leaves or Pandanus leaves, and rests on a framework of thin sticks. The roofing material is firmly attached to these sticks by coconut fibre cords. The hut entrance is at the gable end as a rule; it is a rectangular opening 50 to 70 centimetres square, just big enough to let a man through, and is closed by a board door carefully fitted to the opening. The door can be closed from the inside. This door hangs at the upper end by means of strong fibrous cords passing into two holes bored in projections on the inner edge of the gable plank. The interior of these dwelling houses is kept very clean; the floor is covered with a thick layer of snow-white coral sand. In the middle stands a rectangular hearth surrounded by thick, wooden planks with an under-layer of broken coral fragments, on which the fire is lit for cooking food.

In addition, the dwelling house has one or more beds for sleeping, made of smoothed boards neatly put together; and a frame for storing wooden bowls and other utensils.

Under the roof they stow weapons and other effects. Both the inside and outside of the dwelling houses are always whitewashed clean with lime.

Besides these dwelling houses there are numerous small houses which are of the same construction as the dwelling house, but rest on four thin, round supports and have a plank floor. These little houses are far smaller than the dwelling houses although just as carefully constructed. I am not yet completely clear about their use. These always contained food items and their erection on four supports could have the purpose of protecting the food from rats and mice. However, they could also be little houses dedicated to the gods, similar to the dainty little houses on the Palau islands; the foods which they contain might then well be regarded as a sacrificial offering. These little houses are named lea. Huts of plaited coconut palm leaves erected without great care serve apparently only as resting places for the sick. I did not notice houses 186for meetings or discussions; although there are plank-covered seating frames raised on posts and covered over by a protective roof, but these seemed to be a favourite spot for young and old, men and women. Besides the previously mentioned buildings the canoe sheds (pale uá; fig. 69, right rear) should be described. They are simple sheds of two sloping, somewhat arched roof surfaces extending right to the ground, open at either end. They are built without special care or decoration, and are 5 to 20 metres long, according to the length of the canoe stored inside. These canoe sheds lie close together along the beach, the gable ends facing the sea, in many cases concealing the dwelling houses sheltering further behind them.

No particular plan seems to predominate in the layout of the villages. In fact, several dwelling houses form short streets, which are, however, just as often blocked by houses built across them. The house surroundings are kept scrupulously clean, and the spaces between are spread with fine sand and broken pieces of coral.

As careful as they are in construction of their houses, the islanders are just as careful in the building of their canoes, uá (figs 69 and 74, in the background). It is astonishing how splendid and carefully made canoes can be produced by people without iron tools. The typical canoe consists of a hollowed-out tree trunk, and tapers at both ends into a long, straight prow like the prolonged jaw of a swordfish. The upper edge of the ends of the canoe body is formed by a carefully added piece of wood, which tapers rapidly into an upwardly directed spike; these points are suitably lengthened by accurately fitting, long and very thinly worked extensions, na úna, which in turn are often decorated with bunches of human hair. When many canoes lie side by side, the two vertical extensions are removed as a rule and stored in the canoe, to avoid being broken off in the event of collision. The outrigger, tamáne, is attached to the body of the canoe in the usual way. The size of the canoes varies considerably. There are canoes 18 metres long which hold twenty men, and small ones 3.5 metres long which take one man; in between these are all possible sizes. The island of Durour in particular has a number of very large canoes, probably for their occasional raids on Wuwulu; on the latter island medium and small canoes dominate.

On both islands the canoes are treated with great care. This is shown not only in the workmanship but also by their habit of hauling the canoes over the reef and putting them under cover in the sheds immediately they return from sea, and whitewashing them inside and out with lime after every use.

The canoes are propelled with paddles, póre. These have a broad blade tapering to a point that, with the handle, is often made from a single piece of wood; frequently, however, the blade is attached to the handle by cords. In such a case, handle and blade are attached to each other so skilfully and accurately that it is hard to find the join. For bailing out water they use wooden bailing spoons, ázu, with an inward-curving grip, carved from a single piece of wood. Mat sails do not appear on the islands.

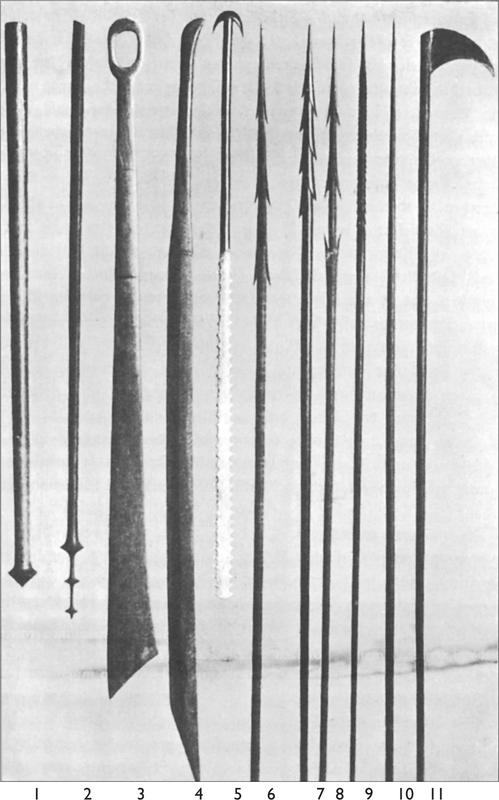

The weapons (fig. 70) of the islanders are, like everything they make, beautifully and neatly worked. At first glance one would be tempted to assume that they were made in a workshop equipped with modern tools. Everything is neatly rounded and smoothed; the individual parts are so carefully fitted together that the join can hardly be seen; the barbs of the spears are so symmetrical that their production would cause great trouble even to a practiced European woodworker.

The weapons can be divided into several main groups, namely wooden spears with or without barbs, close-quarter weapons whose ends are armed with sharks’ teeth or with sharpened turtle bones, clubs and wooden swords. Included among the weapons is the multi-pronged fishing spear which on suitable occasions is also used against men.

The wooden spears, both the completely smooth ones with a simple point (fig. 70, no. 10), and those armed with barbs (nos 6 to 9) have the group designation ogióge. The length varies between 2.5 and 4 metres. The shaft is carefully smoothed; the simple point is long, drawn-out and very fine and sharp. The barbs are either arranged in a simple row on one side, or are symmetrically opposed in two rows; besides these there are spears whose barbs are attached around the spear tip like overlapping scales.

The close-quarter weapons with sharks’ teeth are called paiwa – both the small, hand weapons with a short handgrip and a double row of three to five sharks’ teeth, and the long-shafted, lance-like weapons which have a shaft 1 to 2 metres long and are armed at the end with two opposing long rows of sharks’ teeth (fig. 70, no. 5). Both types are strongly reminiscent of similar weapons from the Gilbert Islands. The shaft ends of the long paiwa frequently end in a neatly carved crescent-shaped knob. To this group also belong the long weapons, one end of which is armed with a carefully sharpened piece of turtle bone (fig. 70, no. 11); this form is named au i á ue. The bone blade has the shape of a half crescent moon; the downward-curved point and the concave side are feathered off. They are used in pursuing the enemy, when the sharp, concave side of the blade is used as a hook, partly to cause severe wounds and partly to cause the enemy to fall. They have similar weapons, to which small barbs of turtle bones are attached in two opposing rows; these form a transition between the weapons just described and the shark-tooth spears. This type is designated au i á ue also.

Clubs are given the group name puleta. The basic 187form is a round baton with a sharp-edged, broad pommel (fig. 70, no. 1). The lower end of the club is slightly broadened and is oval in cross-section. However, there are characteristic variations in the shape of the pommel, which should not go unmentioned here. A simple knob is the general rule; there are, however, double knobs, and multiples placed one above the other in such a way that the adjacent knob which is connected with the one below by a thin shaft, is always made somewhat smaller (fig. 70, no. 2). These types of knobs are nothing but decoration. However, it is different when the knob ends in a long drawn-out point that can be either round and smooth or armed with barbs like the ogióge; the club can then be used occasionally as a spear. I have come across a similar connection between club and spear in Bougainville.

Quite unusual is the weapon that has the shape of a mighty, double-edged sword with a straight handle or that of a long-handled carving knife (fig. 70, nos 3 and 4). Both types have the name awuáwu. Herr von Luschan has already suggested earlier that these weapons are probably imitations of old Chinese iron weapons. Wherever the original example of this weapon may have had its origin, it is certain that the awuáwu are imitations of iron weapons. This is confirmed not only by the form of the blade but by many details of the shape, which although totally irrelevant, the natives have to some extent retained. Thus from time to time we find the iron or brass ring (which in the original weapon was attached at the point where the iron blade was inserted into the handle to prevent the latter from splitting), faithfully carved in wood; likewise small heads on both sides of the handle in imitation of the rivets or bolts whereby the blade of the original was attached to the handle. Several shafts have ornamented ends often in the shape of a crescent, as in the long-handled páiwa, but frequently in a totally different form. I possess a specimen in which the shaft end has a wooden ring carved out in one piece, which stands freely as a loop, and is without doubt the imitation of an iron ring.

I will follow with a description of the fishing spear nawa, because this is not only used for fishing but is also used as a weapon in battle. All these fishing spears have four prongs. The shaft is thickened at the end and contains four carefully made grooves into which the ends of the individual prongs fit exactly.

For inserting the prongs they use as glue a substance which bears great similarity to our gum arabic. The prongs, which rise a little obliquely from the spear shaft, are wrapped around and fastened to one another with cords for better stability. Only a few nawa have smooth points; by far the greatest number have barbs which follow one another more or less closely in a row. On Aua I saw fishing spears in which prongs and spear shaft were carved out of a single piece of wood; here the prongs were circular and smooth.

Fig. 70 Weapons fom Wuwulu and Aua

Before I leave the weapons I want to mention that Dr Karutz of Lübeck, in Globus 1903, volume 2, has attempted to demonstrate the relationship of a few Wuwulu weapons with weapons from the island of Engano, western Sumatra. The short, hand weapons from Engano have a surprising similarity with the short páiwa; and the relationship of the long weapons with two rows of bone blades (often replaced in recent times by brass handles), with similar weapons from Wuwulu and Aua, leaps out at us. A further proof is that foreign influences have made themselves felt on these remote islands, and these influences did not originate from the New Guinea coast opposite but have their origin far to the west. Perhaps the wooden swords have immigrated along the same path.

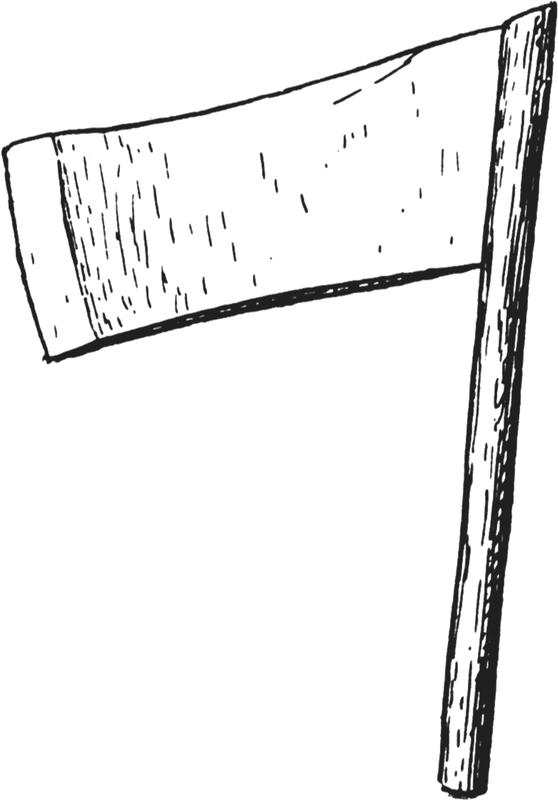

The axe blades, poa, produced from Tridacna 188shell are distinguished by careful workmanship. Both the shape and type of attachment vary. We mainly find the widespread attachment where the blade is tied firmly with a knee-shaped hand grip, so that the cutting edge of the axe is at right angles to the handle. A second form has a straight handle and a hollow wooden intermediate piece into which the blade is pushed. The handle is up to 80 centimetres long, the outer end is somewhat thicker and has an elliptical hole bored through it which is about 35 millimetres long and 15 millimetres wide, and somewhat oblique to the long axis of the handle. The handle is wrapped with fibrous cord both above and below the hole, to prevent splitting. The intermediate piece is pushed into this opening. This is often one piece, but frequently also of two exactly fitting halves pushed together. One tapering end of the casing is pushed into the hole in the handle. The axe blade is bedded into the other, broad end, and the rim of the casing is woven over with cords or strips of fibre as reinforcement. At the outer edge the wooden case has a small, hooklike projection which serves to fix the position of a bast loop which passes round this hook and on to a projection on the axe handle somewhat beyond the hole, in order to hold the case and handle together better and more firmly.

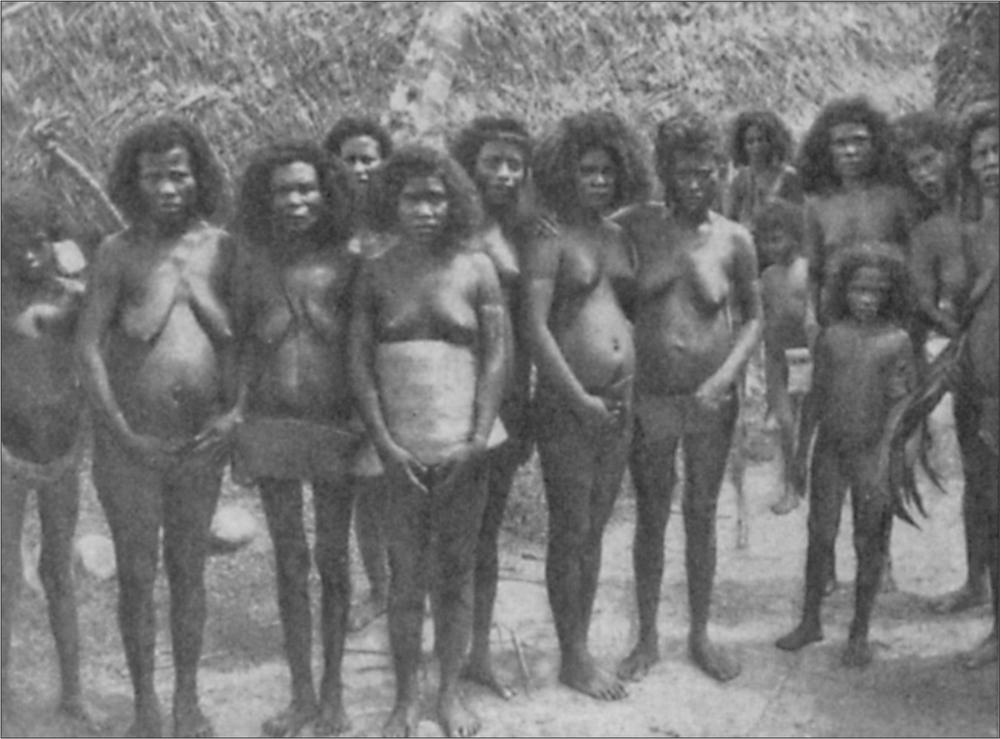

Fig. 71 Women from Aua

The Tridacna blades are of different sorts; several have a regular triangular shape, and a straight cutting edge ground off one side running parallel with the axe handle; in such axes the casing usually has two hooks, so that the blade can be turned round as required; then the ground surface of the cutting edge lies to right or to left as is most convenient to the worker. Another type of blade is very long, up to 35 centimetres, and equally broad along the entire length. These are ground in such a way that the long sides are rotated a little towards the long axis, giving a tilted position to the cutting edge. The blade of these axes is semicircular and the faces of the sharpened blade are somewhat concave. The wooden casing has only one hook and therefore cannot be reversed. Thus one finds this axe form with the concave faces both to right and to left, so that the carpenter can preferentially select the most suitable axe according to whether the surface being worked on lies to his left or his right. This latter type of axe is used especially for hollowing out canoes; while with the first-described axe the side walls of the canoe and also the posts and planks in house construction are cut out and smoothed.

Domestic utensils are present in fair numbers and in the most varied form. To begin with, the great quantity of daintily worked wooden bowls is astonishing. The finest, uniquely shaped, are the rectangular dishes with an arched bottom and curved sides (fig. 72). This is called apia. As well as these, there are oblong bowls with rounded ends, hollow-shaped bowls with two small rectangular projections as handles, and also small, very fine double bowls with round ends, táli, and with pointed ends, tábe. Small, bucket-shaped containers holding one or two buckets are also found. For pounding taro tubers, patilo, and breadfruit, mamá, they use a wooden pounder, pane. These pounders, like all the other items of the islanders, are very neatly made: quadrangular or triangular in shape with stained decoration. The pounded fruit pulp is divided up with axe-shaped spatulas, tigo (fig. 73); for some time these were regarded as a type of axe. There are also wooden spatulas without handles, with a straight edge, called tutuene piapia. It is self-evident that they do not lack an implement for scraping coconuts, águ. This coconut scraper, á-i, consists of a quadrangular little board with an obliquely protruding blade-like attachment; at the end of this attachment is a Cardium shell as a scraper. To use it the worker kneels with one knee on the board, which gives the implement the necessary stability.

Included among the domestic utensils are woven baskets, raba, of coconut palm leaves. These baskets are frequently fixed to a cord, and these in turn to a broad hook, tauia raba, which is clasped round the neck or the shoulders for carrying the basket. Also included are the large chests constructed from wooden planks, with tight-fitting lids, frequently found hanging from cords in the huts. These chests are 50 to 70 centimetres long, wide and equally high. These serve as storage for all kinds of domestic implements.

As a stimulant the islanders have betel nuts, tawuai, which, as everywhere else, are enjoyed with betel pepper and burnt lime. Lime calabashes, pulele, are made from an oblong, gourd-like fruit constricted in the middle; brown decorations are branded onto the yellow surface, most commonly fish and fishhooks.

That such a bright and lively people as the islanders are given over to dancing and amusement comes 189as no surprise. During my visit, one needed only to make the gestures of dancing for everyone there to start dance steps and leaps. As far as I was able to see these did not differ significantly from the dances of most Micronesians. Unfortunately the singing remained incomprehensible to me. I observed a long spear, split above into two or three rounded tips about 75 centimetres long, being used as a special dance accessory. These dance spears, which I can best describe by the term ‘spear-rattle’ are held in the women’s hands in certain dances; the rhythmic thumps or shaking of these spear-rattles, ko, creates a rattling noise.

Fig. 72 Wooden bowl from Wuwulu

As an accompaniment to the dancing they use hour-glass-shaped drums, aiwai or aipa, which use the stretched skin of a large species of lizard, uaki, which runs about the island in a tame state. These sorts of drums come in various sizes. I have seen small ones about 20 centimetres high; the largest measured approximately 1.5 metres, with all possible sizes in between. At the intermediate constriction a small wooden loop is fashioned, through which the cord that fastens the drum skin is pulled.

Fig. 73 Axeshaped spatula, Wuwulu

It is quite interesting that the same form of drum reappears on the island of Ponape. The governor, Dr Hahl, told me that such drums are used at special large celebrations on Kitti. F.W. Christian says in his book, The Caroline Islands, page 138: ‘The local drum is named aip … I saw one in Palik, now in the British Museum, which was about 5 feet high.’ This reports makes it probable that a relationship exists between Wuwulu and Aua on the one hand and Ponape on the other. Also, the names point this out: aiwa or aipa on Wuwulu and aip on Ponape are undoubtedly the same word.

Fig. 74 Men of Wuwulu are sitting on logs today

There are still other points of connection, which lead us as far as the Polynesian islands. Here belongs a smooth spear-like stick about 1 metre long, made from tough, hard wood. One end is finely pointed, the other end is about 1 centimetre in diameter and carefully rounded. From butt to tip the stick is painstakingly polished. This stick, punéne, is a plaything for the male population, used by young and old. In using it, different groups are formed; each individual member takes hold of a punéne and flings it with the thick end forwards in such a way that it touches the ground about ten paces away and then shoots further in a broad, flat arc. Whoever throws furthest has won. Long, constant practice and great skill are attached to this stick throwing. In Samoa and Tonga we find exactly the same game, here named tanga-tia, except that they do not use such carefully made staves, but simple straight sticks, tia, from a particular wood whose bark is removed. We find the same game on Rotuma, where the staves are of a soft, white wood, and a rather egg-shaped piece of wood about 7 centimetres long and 2.5 centimetres in diameter is firmly attached to the throwing end. Wooden 190tops, puélo, which they spin in a bowl, seem to be a favourite plaything.

Fishing equipment is the usual kind. I have already described the multi-pronged fishing spear, nawa. On Aua they use long spears, up to 8 metres long, with smooth points for catching those sea creatures that live in deeper water at the edge of the reef. Otherwise they use fishhooks, áwui, ground from shell, and also nets of different kinds – the large sunken nets with sinkers and floats, smaller hand nets stretched on a wooden frame, and drawnets with a long wooden handle.

As far as the islanders’ clothing goes, there is not much to speak of. The men go about completely naked; at most they cover their heads with an artistically fashioned hat, tao, made out of Pandanus leaves or with a wrap-round of green banana leaves. These hats which were made from bleached Pandanus leaves and decorated with characteristic wing-like extensions, seemed rare even during my visit; today they will have totally disappeared. The women wear a thin cord round their abdomen with a single green leaf attached in front to cover the genitalia, and a short bunch of coconut palm leaves behind. Most young girls go about completely naked. From strips of Pandanus leaves sewn together they made large squares of 1.5 metres. These were called rauada, and served partly as protection against rain or sunburn, and partly for wrapping up smaller items. In the huts the plank beds were covered with these as underlay.

I observed only a small amount of jewellery. There were roughly worked armrings of Trochus; Pandanus leaves with long, free-swinging ends were attached to the upper arm or below the knee. Occasionally I observed a woven armband with natural-coloured and black-stained Pandanus leaf strips. The women’s ear lobes were pierced and enlarged to an enormous size so that they hung down as far as the shoulders. These pendulous ear lobes were adorned with round, turtle-shell discs, alia, so that disc lies on disc. To round it, a rib of a coconut palm leaf is laid along the ear lobe. The same ear decoration occurs on Ninigo and Kaniet, and also on St Matthias where the rings are smaller, however. Both men and women now and again wear simple necklaces of small Oliva snail shells about 1.5 centimetres long, strung together.

Boys and small girls wear their hair about 3 to 4 centimetres long. Youths and adults as a rule have it arranged in long locks, rubbed with a white paste; in some islanders these locks hang down the back as far as the waist; older men often wear their hair cut short. Youths plait long narrow strips of Pandanus leaf into their locks, and these flutter in the wind when running or paddling. As a head ornament they use, in many cases, a bleached strip of Pandanus leaf which is laid round the forehead and knotted at the back in such a way that two long tails hang down the back. The women appear to look after their hair carefully; dirty hair was not seen. The hairstyles were carefully piled up; I did not observe combs. In many cases the hair was parted in the middle and fell over the ears down to the neck. Hair colour is a deep, dark brown. The hair of the albinos, who seemed relatively common, was flaxen. A few albinos had a pale red skin over their whole body, others were patchy pale red and brown, and made an unfavourable impression with their squinting eyes surrounded by flaxen eyelids and brows.

I did not observe tattooing and decorative scars although I looked carefully.

As food they use coconuts (ripe = águ, unripe = up), which are sometimes eaten without further preparation, and are sometimes grated and mixed with other foodstuffs. Then there is taro, patilo, and a species of Alocasia, and breadfruit, mamáa, and to a small extent bananas, parawu. Taro and breadfruit are roasted between glowing stones and ash, and sometimes eaten in this state or sometimes crushed and mixed with grated coconut. The pulp is then baked again and is quite tasty. In specially arranged plant pits, as on Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu and also on many of the low, coral islands of the South Seas, they grow a species of Alocasia, whose rhizome is edible, like the taro tuber. Here it is called fula, on Nuguria and Nukumanu paluka, in Samoa pulā. Fish, nia, serve in great measure as a foodstuff, the more so since there are no dogs, pigs or domestic fowls available on the islands. The large, well-nourished species of monitor lizard which runs around among the houses in a tame state, is not eaten. Drinking water, rano, is available in shallow, dug wells; salt water from the sea is called ári.

The language is the same on both islands. Although only little is known of it, it seems from the small amount of information yielded that we are dealing with a Malayo-Polynesian language. Of the few words that are known to us, they very much have the greatest similarity to central-Polynesian words.

Breadfruit is called mama’a on Wuwulu; in Samoa a certain species of breadfruit is called ulu ma’a (ulu = common name for breadfruit). Fish is called nia; in Samoan i’a. Ear is ali’a; in Samoan talinga. Tooth is liwo; in Samoan nifo. Woman is piwine; in Samoan fafine. Fire is avi; in Samoan afi. Canoe house is called pale uá, a combination of the words pale (Samoan fale = house) and uá, Samoan va’a = canoe). The flying fox is bea; Samoan pea. The tree Terminalia catappa is called ![]() Samoan talie. This is an extract from a small list of about fifty words, about 20 per cent.

Samoan talie. This is an extract from a small list of about fifty words, about 20 per cent.

The word structure by its richness in vowels also appears to indicate a central Polynesian relationship.

From this we could perhaps conclude that the Wuwulu and Aua islanders are a branch of the great 191Malayo-Polynesian tree which, originating from the west, spread over the South Seas. Since settlement on both islands, foreign tribes have occasionally settled there in passing, or have at least made temporary contact with the islanders, and from these visitors new implements have been adopted, such as the sword-like awuáwu which is certainly an imitation of iron weapons. The similarity of several weapons from Engano could indicate where the Wuwulu people originally migrated from; the occurrence of the large, hour-glass-shaped drums on Ponape might perhaps give us a hint which route the migrants chose.

Plate 28 Natives of the Matánkor tribe on the island of Lou

I was not able to observe any Melanesian influences during my visit, although the islands lie only about 87 nautical miles from the coast of New Guinea. Yet, according to Hellwig’s reports, many Melanesian references should be found in the language.

2. Ninigo, Luf and Kaniet

Between the Matty group and the Admiralty Islands lie several island groups and isolated islets; firstly the small coral island of Manus (Allison Island) about 20 nautical miles east of Aua, and settled from Ninigo. The latter group, called l’Echiquier or Chessboard Islands by its discoverers, whose outliers are about 40 nautical miles east of Manus, consist of about forty or fifty rubble islands. Almost all lie within sight of one another, with the exception of several of the northernmost islets.

The approximate spread of the whole group from south-west to north-east is about 35 nautical miles. Seven nautical miles south of the southern limit of the group, several smaller, uninhabited islands lie on an isolated reef, as does the small island of Ufe or Liot, which lies about 15 miles east of the eastern limit. These small islands were settled from Ninigo; however, the population is not permanent, but appears to visit only occasionally.

About 40 nautical miles east of Ninigo lies the small Luf group which consists of a coral reef on which a number of larger and smaller rubble islands have formed. The reef is roughly oval with a longer diameter of about 15 nautical miles from east to west, and a shorter north-south diameter of about 10 nautical miles. Several passes lead through the reef into a deeper basin which is intersected in part by coral banks; however, in the middle a number of higher islands rise up, formed partly from basalt rock. These in turn are surrounded by shoreline reefs and are dry at low tide. The largest of these central islands is Luf, a name which has been extended to the entire group, probably incorrectly. On the maps the group carries the name Hermit Islands. The designation of Agomes for this group is based on an error. The natives do not recognise the name, either as a common designation for the whole group or as the name of one of the individual islands. The name is a distortion of the name ‘Hermit’ which in the mouth of the natives becomes ‘Aramis’ or ‘Agomis’ and had been incorrectly understood by Europeans. Accordingly, the name should be removed from the maps. A general designation for 192the whole group is not known to the natives. The highest peak on the central islands is about 160 metres. Recently the group passed into the ownership of a European who settled on one of the smaller central islands, Maron, and attempted to make the rubble islands and the central islands, as far as they were not already covered in coconut palms, profitable from new plantings. The vegetation of the islands is relatively luxuriant, and bananas, taro and yams, apart from undemanding coconut palms, grow excellently, so that the inhabitants need suffer no lack of food resources.

Forty-five nautical miles north-east of Luf lies the small group of Kaniët or the Anchorite Islands. It consists of several rubble islands situated on a common coral reef. The largest of these islands is Suf, the easternmost of the group; the other five small islands are of lesser importance. Kubary, who visited these islands years ago, gives the presumed origin of the name Kaniet, which according to him is a designation of the Luf people, with which they describe the ugly, enlarged, pierced ear lobes of the women there. Kahenien (ear) and heis (ugly) is combined into Kachiniesi and abbreviated to Kaeniesi (Kaniet?) by the natives of the group. The islands are low, the vegetation poor, and the population in the process of dying out. About 18 miles north-west lies the small atoll of Sae or Commerson Island. It is uninhabited and is visited by the merchant stationed on Kaniet for the purpose of exploiting the stands of coconut there. Sixty nautical miles north-east below the equator lies the small group of Utan, two islands on the map; they should be well populated, but I do not know whether they have ever been visited by Europeans.

On all the above islands the population is rapidly dying out. On Kaniet there are still about sixty natives, and on Luf about eighty. The Ninigo group comprises 400 natives but a significant decline is occurring here too. Elephantiasis, syphilis, yaws, and so on, are the main causes of the decline. In earlier years, numerous workers were taken to the Carolines from here, for harvesting trepang, but only few ever returned.

We are grateful to Herr Kubary for quite an extensive sketch of the ethnographic situation on Kaniet, which is the more interesting since in his time the population was still numerous, and possessed many characteristics which have totally disappeared today.2

The present population is quite harmless. However, it is not long since they were still insidious and treacherous in their dealings with white people. In 1883 the imperial corvette Carola had to undertake a punitive expedition against Luf, because the natives there had murdered Hernsheim’s traders and boatmen. The Ninigo population is still the most enterprising; they maintain southern connections with Aua and Wuwulu and to the east and north-east with Luf and Kaniet, although the presence of traders on the latter islands has gradually scared away the visitors.

Both Kubary and Thilenius agree that there is an interbred population on the islands, showing Polynesian and Micronesian characteristics but also Melanesian, the latter alluding particularly to the Admiralty Islands. Besides this, influences are evident which could be designated as Malayan and are probably of more recent date. This should not puzzle us, for where in the entire South Seas do we find an island where we can assert that the population is not the end result of multiple interbreeding and admixture of different races? In predominantly Melanesian populations we find many traces of a Polynesian admixture, and vice versa in predominantly Polynesian populations, as in the New Zealanders, the Samoans, and so on, clear traces of a dark, frizzy-haired race which could possibly be Melanesian.

In the following description of traditions and customs, weapons and implements, and so on, I am following the accounts of Messrs Kubary and Thilenius.

At the birth of a child, on Kaniet the baby was laid in a wooden dish (finola) and bathed with fresh water; after the bath all the hair was singed off the head with a glowing stick of wood and the little body was rubbed with coconut oil. Then the women brought their good wishes, and at the feast following in the evening the newborn baby was shown around, clad in a girdle of coconut fibre and a little chest ornament of turtle shell.

The child belonged to the father. Daughters remained indoors even after weaning, learned weaving while growing up, and helped in the preparation of meals, and household tasks. Sons were almost always passed over to another family for raising, and learned to fish, how to set up a garden, and so on.

As the time of sexual maturity approached, both the boys and the girls had to undergo a series of preparations and ceremonies.

After completion of the ceremonies the boys entered the company of the adult islanders. During these they were ‘tabún’; that is, totally excluded from society.

The headman determined the onset time of the tabún, when his son or those of his dependants reached the age of about ten to twelve years. On the reef far from land, or in the uninhabited tabún-covered region of the island of Suf a large house was built. The boys were brought here under the supervision of an old man, who bore the title ‘úta’, and a limited number of male relatives. From the instant of entering the amahei tabún (amahei = house) the boys were tabún, and ate certain meals prepared specially for them, which their companions were not allowed to eat. The food was prepared by the natives in the villages and sent by the headman.

193As long as the boys still wore their hair upa upá – that is, hanging down loosely – they dared not eat any food cooked on hot stones, but only taro cooked on the open fire; they were likewise restricted from enjoying fresh breadfruit, coconut milk or old nuts with a spongy kernel; fish was only in dried or smoked form. Only when the hair had reached a length when it could be designated as faosi, did they dare touch food cooked with hot stones; however, they still did not dare to chew betel. Besides this there were still other stipulations of the tabún to be observed. It was forbidden for a boy to wet his hair with salt water, to catch any fish, look upon a woman, nor show himself to his father who might in an exception come to the amahei tabún. Should the father or headman come there, the residents hid in their sleeping area and stayed there until the others had departed. During their seclusion the boys learned the traditions and customs of their people from the úta, and also decorated the house for the moment of their release, and gathered in supplies for the feast to take place then. These supplies consisted of smoked taro which were cultivated in their own gardens. Under the supervision of the older men the boys went to the taro gardens in the early morning, taking a path stipulated by the úta, which was situated in such a location that they ran no danger of encountering the island inhabitants, especially the women, on the way. Yet, should the latter appear, the boys had to run away and hide immediately. The ripe taro were taken to the house, peeled, and arranged on long sticks to dry in the smoke; prepared in this way they could last for years. Decoration of the house consisted of festooning the interior with long, coloured coconut palm leaves, which were packed so closely together that you had to force your way through using your arms. If the hair had already reached such a length that the úta could to some extent calculate the precise point when a worthy hairstyle can be fashioned from it, then preparations began for the actual initiation. Banana plantations were set up and when after a while the fruit was ripe they were brought to the house which was then hung with bananas. When this had been done, the boys gave the village dwellers a sign, by singing and noise, that the time of the initiation had now come. The following day the fathers went to the house to see their boys now grown into youths, and displayed great joy at the reunion. The bananas were given to the headman, who distributed them among the other fathers. From then on the boys wore their hair bound up, and the tabún was lifted with regard to food.

Then follows a repeated complete isolation of the youths until the hair has become so long that the real men’s hairstyle, lubún, can be produced from it. When this time is reached the boys are collected by their relatives, together with all their gathered supplies, and a general great feast is prepared; however, in the evening the novitiates always turn back to their house.

When all the preparations are complete, each youth receives a patakom – that is, a heart-shaped, bound wooden frame of sticks – the end of which, the free ends of the bent stick, are crammed down into his belt, while his head hair, separated out as far as possible, is attached to the upper end. The whole frame has a height of about 2 metres; the greater the surface covered with hair, the more respected is the wearer.

With this load, and in the head position this entails, the youth goes around his home island and under no circumstances dares support or hold the patakom with his hand. The headman’s house meanwhile has been densely festooned with coconut palm fronds and banana leaves, and towards evening the youth enters with the patakom which has not been allowed to be set aside; all the relatives and a few friends are present. As soon as the youths have entered, a designated man reports by singing accompanied by drums, what has happened during the confinement. A festive meal takes place and the youth may chew betel for the first time. The headman then plaits the hair of the initiates. They now become his subordinates and go about with one another in a firm friendship.

From that time on, the man’s head is sacred and no woman’s hand dare touch it. It is therefore also no wonder that the islanders take great care of their hair; it should not be wet with salt water and is washed only infrequently with fresh water but is richly oiled with coconut oil so that it appears shiny black. The hairstyle called lubún consists of the shock of hair tied off over the shoulder, being laid forwards and bound crosswise one to seven times. Hibiscus and other blooms, red beans, and small turtle-shell rings are used for decorating the hair. Also the turtle-shell nose ornament is often stuck forwards in the hair, or long pieces of turtle shell hang down the back.

Naturally these preparations for the acceptance of youths into the society of the adults take a long time, often up to two years. Before that time the hair of the boy’s head is uku diáko – that is, no hair – and women may touch it; only at the time of the tabún-e uk (úku = head hair, tabuni = sacred, forbidden) – that is, immediately the initial preparations for the initiation have started – does the state of sacredness of the hair come into force. At the onset of menstruation the girls are likewise taken to the isolated house and are then tabún. After a stay from one and a half to two years they leave; richly adorned they walk round the island and, depending on the capacity of the parents, a larger or smaller feast ensues.

During their childhood, somewhere between the fourth and sixth year, they must, however, undergo 194a very painful operation, slitting the ears, apiteni kahinien fifen. First of all, the evening before the operation, tabún is imposed on the girl; that is, the house where the women and the girl are staying cannot be entered by a man.

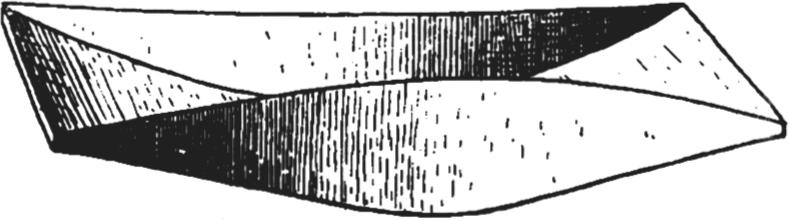

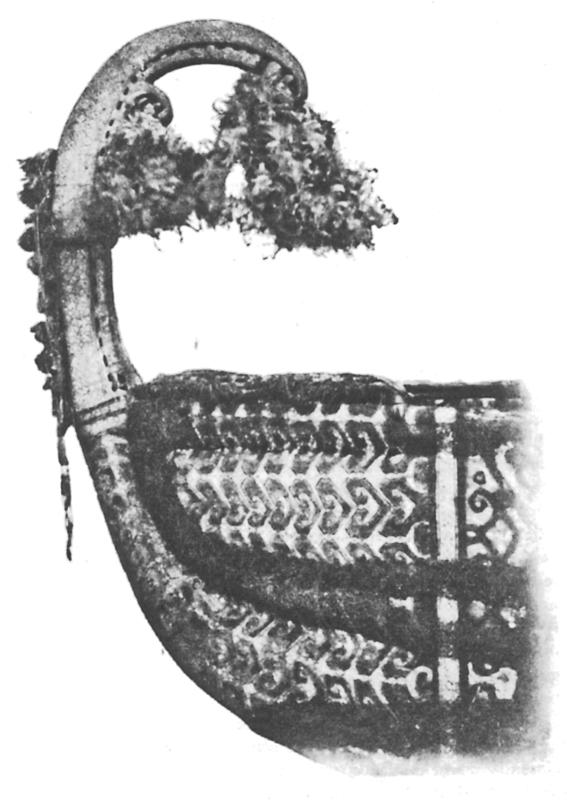

Fig. 75 Canoe prow. Hermit Islands

The small girl’s right hand, corresponding to the first ear to be operated on, is wrapped in a lágu-lágu to promote the rapid healing of the wound made. The lágu-lágu consists of a loop from the vein of a small coconut palm which is fastened to the wrist with two long feathers from the frigate bird. The women stay awake all night and begin the operation in the early morning. The mother holds the child in her lap and other women stretch the pinna of the ear. The woman operating makes an incision with a sharp sliver of obsidian on the floor of the scaphoid fossa from mid-length first downwards to the level of the antitragus then with the child in another position, upwards to the triangular fossa. A roll of dried Pandanus leaves is inserted into the incision, the wound is washed with salt water and the divided border of the helix is protected with small Pandanus leaves. Two days later the binding is removed, and if the wound seems satisfactory the lágu-lágu is taken off thereby lifting the tabún, which also included a prohibition on the family from eating fresh fish or food baked between hot stones. About two months later the left ear is treated in exactly the same way. As soon as the ears have completely healed, the separated margins are densely garnished with turtle-shell rings, and elastic, springy veins of coconut palm are pulled through the rings, so that the separated edge stands out stiff and circular. The ear loop is still further enlarged by these springy leaf veins, and sometimes extend to the chest, which is regarded as a particular accomplishment by the woman.

The boring of the nasal septum is undertaken at an earlier or later age, and without special ceremony. For this process they use a sharpened piece of hardwood.

Upon completion of the celebration of attaining maturity, the young men and women take part in all the tasks of the adults, and especially from now on they are regarded as the equals of the latter in all things.

After death the corpse is either laid in a canoe, taken to sea and sunk, or buried in a shallow grave not far from the house, with face and chest downwards. All movable possessions of the deceased are laid on the grave and burned after about three weeks. Soon thereafter the skull is exhumed, at which time a funeral feast takes place; the skull is placed in a basket, hung up in the house and smoked. Bunches of leaves are fastened to the zygomatic arch; the orbital part of the frontal bone is bored through from near the zygomatic process to the orbit of the eye, and into both holes they push a bunch of leaves or small sticks, the latter bearing bunches of white feathers on the ends jutting over the forehead. The skull prepared in this way is not only a memorial, it is also used in numerous invocations to turn away the spirits (pafe) of the dead, which in general bring everything nasty and horrible, from their evil intent.

On Luf, ceremonies like those described on Kaniet are no longer mentioned. No records of them exist from earlier years; therefore we cannot judge whether similar customs were ever known there. Newborn babies are washed in the sea, and the afterbirth is buried in the forest. Any form of ceremony for the arrival of maturity is unknown today. The body of a man is interred in the canoe shed; that of somebody who died as a result of illness is buried in the forest. All movable possessions are laid on the grave, as on Kaniet. Here, too, the belief is firmly rooted that the spirits of the dead roam about and attract illnesses and all misfortune. They are supposed to roam about particularly at night, and food is left out for them so that they will leave the residents in peace.

We do not know much more about Ninigo than we do about Luf. The treatment of newborn babies 195is the same; the burial is the same as on Kaniet. The souls (amal) of the dead also roam about, live in trees, practise all kinds of mischief and are banished by invocation.

It is obvious that in a population in decline, social behaviour will also show signs of the decline. What we see here is not to be regarded as the standard of what existed previously, when the population was flourishing. There are of course still headmen today; they seem to have been originally, according to their rank, leaders in battle; possibly they were also people who, because of their wealth, exercised a dominant influence.

The position of women is a subordinate one. On Ninigo monogamy prevails, the husband buys the woman from her father; it is the same on Kaniet, and on Luf it was the same in earlier days. However, on the last-named island, with the population decline and because of the scarcity of women, the custom has arisen in recent times of a married man giving his wife to another as a gift or surrendering her from time to time. The wife is, to a certain extent, the common property of all men.

A fairly active trade existed earlier between the various islands; in addition the Ninigo people traded with both Wuwulu and Aua. Even though peaceful conditions reigned for the time being, qualified by bartering from island to island, hostile encounters were also not infrequent, on account of the custom of taking natives of one island as slaves to the others. Whether the natives extended their voyages as far as the Admiralty Islands, about 100 nautical miles further east, is not established; on the other hand, it is certain that not infrequently boats arrived here from the Admiralty Islands.

Great care is taken in the construction of canoes. Dr Thilenius gives true-to-life illustrations of the Kaniet canoe in plates 19 and 20 and a detailed description. Since no suitably strong trees grow on the island, they resorted to driftwood. The size of the trunks driven ashore determines whether they will build a fishing canoe, oai, or a voyaging canoe, muaij. The oai is decorated at both ends by a projecting prow, which carries the same decoration as the wooden bowls called finola. Both sides of the canoe are raised as necessary by narrow planks, which are lashed to the edges of the single tree trunk by coconut fibre cords. To prevent the canoe tipping, outriggers and floats are attached to one side of the boat. The float is about two-thirds the length of the canoe, and is made from a light wood. The outriggers, four to five in number, are fixed to battens which are firmly driven into the body of the float. On the upper surface of the outrigger, beginning at the gunwale and covering half the outriggers, staves are laid side by side and firmly tied to the outriggers. They form a platform on which all kinds of equipment are loaded while fishing or during a voyage, since in the canoe itself there is little room. The mast is erected in the bottom of the vessel and is held in place by one of the long mouldings which run fore and aft, and by two hawsers which stretch from the masthead to the front and rear outriggers. The quadrangular mat sail is fixed between two spars; the lower spar bears a fork which is placed against the lower part of the mast; at about a third of the distance from the end of the upper spar is a hawser, which is placed over the fork-shaped upper end of the mast. By means of this hawser the sail is pulled high up the mast. Several guide hawsers then serve for further positioning of the sail.

On Luf the shape, on the whole, is similar, although the attachment of the outriggers to the battens driven into the float is somewhat different. Dr Thilenius mentions a large voyaging canoe that he saw lying on the beach during his visit to Luf but was unfortunately not able to examine closely because of a lack of time. Herr Thiel on Matupi, at great effort and cost, had this splendid item transported to his main station in the Bismarck Archipelago, at which site I was able to take a number of photographs of this rare piece – the last of its kind still in existence.3 The substructure of this canoe, forming to some extent the base, is a single giant trunk. Both sides are raised by several planks and the ends of the canoe are made of special pieces. A superstructure is added to the strong outriggers, which bring to mind similar ones from Berlinhafen in New Guinea. On the opposite gunwale are smaller, steeply rising platforms which serve for stowing loads. Characteristic of these large voyaging canoes is the extension attached at each end, by which the prows obtain an increase in height. This is curved upwards and inwards, and is completely decorated with a carved diamond-shaped pattern. Shorter bunches of coconut fibres and knotted cords decorate both outer prow sides, and the curved ends of the prow are decorated with two gigantic bunches of feathers. The entire outer body from gunwale to keel is extremely carefully painted with several rows of regular figures in russet and white. The canoe has two masts with quadrangular sails.

However, better than the most detailed description, the accompanying plates 30 and 31 and figure 75 will give the reader an idea of this unique vessel, which could carry up to fifty people. One cannot doubt the seaworthiness of this mighty canoe, the less so when one remembers with what small, fragile vessels the Polynesians used to undertake long voyages.

On Ninigo the shape of the canoe is somewhat different. Here as well there are single tree trunks with outriggers and floats, masts and mat sails, but whereas on Luf and Kaniet the round form of the single trunk, corresponding to the natural shape of the tree, was observed, on Ninigo trimming of

196the tree trunk gave its specific shape.

Plate 29 Village scene on Aua

The bottom is flat and the bulwarks stand outwards a little steeply, and have flat, hewn outer walls. A long prow of separate pieces is fixed at both ends, deviating not far from the horizontal and tending only slightly upwards. The canoe, although it shows no similarity in form with the Aua or Wuwulu vessels, nevertheless gives the impression that in its production the neat carpentry of the Aua people has found an imitation, although of course in a deviant form.

House construction has been dealt with in detail by Dr Thilenius in his work. In this regard great artistic skill does not appear on the islands. All the huts are low; on Kaniet the lateral surfaces of the roof are flat; on the other islands they are curved and reach almost to the ground. Young people’s houses or meeting houses are not present, and are substituted by the canoe sheds, where these exist. Weapons consist of spears. On Ninigo a surprising similarity to the weapons of Wuwula and Aua is noticeable; on the other islands similar forms are present in a less complete presentation. They are long, thin wooden spears provided at one end with a more or less finely tapering point and a number of barbs arranged in rows. A special production technique is not noticeable; they give much more the impression of the rough and superficial, no doubt a consequence of the gradual decline of the islanders.

Betel chewing is common on all the islands. In older times on Kaniet and Luf they used an egg‑shaped species of gourd as a lime container; however, today this has been replaced by a species of gourd introduced from the Admiralty Islands, constricted in the middle and decorated with black designs as in its homeland. Originally these had been a simple imitation of the ornamentation there, but, over time, differences have developed, to some extent creating an unique style. The lime spatulas from Luf are of special interest. Herr Grabowsky has dealt with these extensively, as more recently Dr Thilenius and Edge Partington. Originally these were decorated at the upper end with a pattern on one side, which goes back to the human figure. Years ago, as a consequence of the artistic skill of a single islander, a particular spatula shape developed, in the decoration of which the spiral played the main role. The decorated part in these implements is flat and done very splendidly in fine open-work. These spatulas are now found only in museums; they are no longer available on the islands themselves, because the artist died several years ago and had no successor to continue the developed style. On Kaniet the human figure is also used to decorate the lime spatula, but here the arrangement of the decoration is in double rows. Very rarely is the whole male figure produced; as a rule the decoration consists of a double row of heads one above the other.

The traditional costume on Kaniet differs in both sexes. The men wear a girdle of coconut cords which are wound numerous times round the waist; the women wear a broad girdle wound several times 197round the abdomen, and made from bleached strips of Pandanus leaf lined on the inside with bark from Ficus indica. These girdles are sometimes decorated on the outside with strips of bark and Pandanus leaves. The usual women’s clothing is a broad piece of bark that is hung over the hips and extends as far as the knees. Another costume, which is only worn at celebrations, consists of an apron, or more accurately a double apron, the two parts of which are worn in front and behind. The front apron consists of a firm woven sheet about 20 centimetres long and 25 centimetres wide whose lower edge has rows of fringe-like strips of leaves in many layers. The rear piece consists similarly of a woven sheet which is, however, more narrow and up to 50 centimetres long; the fringe addition is likewise considerably longer. The sheets are patterned by interwoven bright fibres in diamond shapes. To hold both these pieces firmly, after they have been placed in the proper position, the body is wound round with long cords of coconut fibres, forming a thick girdle. The woven sheets project beyond the tied girdle both in front and behind; the leaf fringes cover the genitalia and the buttocks. On Luf a similar costume prevails, allegedly introduced from Kaniet, but here the fringed apron is decorated with bright feathers and down. On Ninigo the dress is the same, but according to comments from the natives it was only fairly recently imported from Kaniet and Luf. Originally both men and women went around naked, as the inhabitants of Aua and Wuwulu still do today.

Items of jewellery are scarce. On Kaniet we find the previously mentioned turtle-shell earrings and the nasal stick; the latter is made from either turtle shell or Tridacna shell. The comb, carved from soft wood, with an ornamented plate, should be included here. Leaves, coloured fruits, and white feathers in various arrangements also serve as further body decorations. On Luf even fewer ornaments exist. As ear ornaments they wear small turtle-shell discs, besides which they push little sticks of wood or shell through the perforated nasal septum and through the ear lobes. On Ninigo we find somewhat more characteristic ornaments. Worthy of particular note is a quite beautiful neckband of vertebrae from a small shark, to which are added at certain intervals sticks of polished red shell. Besides these, one sees simple turtle-shell rings as ear ornaments, and armrings of plaited fibres of a yellow-grey colour patterned with a dotted design of black fibres. The wooden hair comb is not lacking here either; the long teeth extend from a carved blade, the decoration of which sometimes represents a human figure and sometimes an open-work zigzag design in various patterns.

A particular ornament of men, especially headmen and prominent people, probably an imitation of the usage on the Admiralty Islands, is the artistic design of dental tartar on the anterior teeth of the upper jaw. From the closed mouth a broad black strip projects between the lips and covers a part of the lower lip.

Wooden bowls are prominent among the less numerous household utensils. On Kaniet a characteristic wooden bowl is customary. This is carried round by the men and serves for storing all kinds of small items. These bowls, finola, are neatly and regularly made, bulbous in the middle, and sharply tapering at the ends into open-work carving. Coconut fibre cords stretching from end to end and wound round one another serve partly as handles and partly to prevent small items from falling out. On Ninigo they use pouches woven from strips of Pandanus for the same purpose, made in such a way that one is pushed inside the other like our cigar pouches; from Ninigo these have reached the other islands. On Kaniet, where they are expert at producing a flexible product from the bark of various species of Ficus, they use a pounder for this purpose, about 30 centimetres long, club-shaped and inlaid on one side of the club-shaped end with a piece of shark jaw. On the same island a wooden drum is used, but not of the customary hour-glass shape. The upper end is approximately double the width of the lower end and the sides are not constricted. A monitor skin is stretched over the wider opening.

Fishing equipment consists of larger and smaller throwing- and sinking nets as well as fishhooks of Trochus shell which are reminiscent of the shape on Aua.

Stone axes no longer exist today. The axe from Kaniet calls to mind a similar instrument from the Admiralty Islands; the blade was inserted into a club-shaped piece of wood so that the cutting edge was parallel to the handgrip. 198

1. Since this was written the firm Hernsheim & Co. revisited both islands in 1903 in the person of Herr Hellwig, to plunder the field with regard to ethnographic items to such an extent that the beautiful old objects are no longer available. What they make there now is of poor quality compared with their earlier items. As far as I could gather from Herr Hellwig he was unsuccessful in gathering many new items; on the other hand he had made comprehensive, detailed studies on the use of the items and their manufacture, which he hoped to publish. He also found out several things about traditions and customs; however, as is easily understandable, there are many gaps in this.

The noticeable reduction in population numbers since 1902 is very unfortunate. Currently the population on Matty has been halved, and when Herr Hellwig left Durour at the end of 1903, the mortality rate was abnormally high. Malaria is said to be the cause. Whether malaria reigned there before the arrival of the whites is difficult to say. It has been established that the islands are teeming with Anopheles, and since this species of mosquito is known to transmit malaria to humans, one could assume that the illness was introduced there by infected traders or their workers, and then transmitted by the Anopheles to the less resistant islanders. Islanders who were taken to Agomes as workers quickly went down. It might be hoped that the administration would take prompt steps to combat the malaria and thereby save such an interesting little tribal group from dying out. If this does not happen, then these islanders will go the same way as their neighbours on Agomes and Kaniet.

The quite extensive oral material gathered by Herr Hellwig will, after study by a linguist, probably give us significant conclusions on the position of the Matty islanders in the colourful mixture of peoples of the South Seas.

In 1904 the already greatly reduced population on Durour was further decimated. In the spring of that year the local natives murdered a merchant settler and two Chinese. In fear of vengeance on the arrival of a trading schooner, numerous natives fled in their canoes. Shortly after their escape stormy weather set in; not suited to high seas most of the canoes went down, and their crews with them. In June of that year the imperial governor was able to determine that on that occasion approximately 500 islanders found their graves beneath the waves.

The information and accounts given above relate to the time before this catastrophe.

2. Recently Professor G. Thilenius visited the islands, and published an interesting survey of his observations in the Abh. der Kaiserl. Leop.‑Carol. Deutschen Akademie der Naturforscher, vol. LXXX, no. 2, entitled, Ethnographische Ergebnisse aus Melanesien, Part II.

3. Since then, this canoe has been housed in the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin.