III

St Matthias and the Neighbouring Islands

About 50 nautical miles north-west from the island of New Hanover lies the island of St Matthias, and west of it the small island of Kerué or Emirau, and Squally Island.

Since Dampier discovered the island, apparently nobody visited it until 1864 when work recruiters from Viti sought to establish connections with the islanders. The seemingly harmless people drew back at the landing of the boat, and both white men in charge of the boat settled down on the shore to await further developments. The natives seemed gradually to gain confidence, and approached timidly, but then suddenly fell upon the whites and speared them, and also attacked the crew seated in the boat. The latter succeeded in escaping after a brief struggle, with the loss of two further men.

Frightened by the event, other ships kept away until 1896. In that year a schooner from the New Guinea Company again attempted to establish contact. The natives came alongside in their canoes; bartering developed but led to hostilities after a short time, and the whites went for their guns. In 1898 the steamer Johann Albrecht of the same company attempted once more to make an approach, but with the same result. At the beginning of 1900 a small trading schooner again attempted friendly associations with the people, bartering was begun, but after a short stay things became alarming to the owner of the vessel; he weighed anchor and left, so as not be drawn into a quarrel with the natives.

In May 1900, I had the opportunity to visit the island. The then governor of the colony, Herr von Bennigsen, made a journey there in the imperial warship Seeadler, and the ship’s captain, Lieutenant-Commander Schack, was kind enough to invite me as a participant. Our three-day stay was peaceful throughout; the natives were indeed very shy and always had their weapons in readiness, for which in view of the earlier events you could not blame them. The petty thefts that occurred, which had previously been the main cause for conflict, were allowed to pass over, especially as they concerned worthless small items, and we ourselves were for the most part guilty of their loss, because in our observations of the people and in our eagerness to trade we dropped our guard from our personal belongings, which represented desirable treasures in the eyes of the natives. Although we roamed often up to 10 nautical miles from the ship in the Seeadler’s boats, landing here and there, and were frequently surrounded by numerous natives, our interactions remained always peaceful and we came to the conclusion that a settlement of traders with a sufficiently strong troop of workers for exploiting the trepang on the reef would be possible. By taking the greatest care, drastic action against the islanders for paltry reasons might be avoided.

And so the Matupi-based firm of Hernsheim & Co. set up a fishery base on the small island of Kaléu in the same year.

Things went fairly well up until April 1901. The white traders were eager to establish friendly relations and the natives slowly got used to the presence of the foreigners. They began to fish for trepang and offer them for sale; in short it seemed as though future interaction would be peaceful. This situation was suddenly upset in an unforeseen way. The traveller Bruno Mencke had arrived in the Bismarck Archipelago. A steam yacht was at his disposal, fitted out to the degree of luxury of an imperial mail steamer, and with a very large crew of Europeans and coloureds. The intention of the owner was to carry out a scientific investigation of the numerous islands of the archipelago, and assistants appropriate to this purpose were on board the ship.

However, soon after their arrival in the Bismarck Archipelago, it became clear that science lay not so close to the heart of the owner of the ship as pleasure. Dedicated expeditions were not carried out. They visited particular areas of coast that had been well-known for years already, and then relaxed in the archipelago. Herr Mencke appeared to be weary of it already; malaria had almost totally banished the remaining interest in science, but nevertheless they decided on an undertaking in order to give at least relative justification to the proud name First German South Seas Expedition. The 140choice fell on the island of St Matthias, unquestionably one of the most interesting places in the protectorate. Ethnographically and anthropologically, many interesting things were anticipated here, also the zoological and botanical yields seemed very promising. However, virtually everyone not involved shook their heads sceptically after the goal of the expedition had become known, not because it was seen as unfeasible, but because they believed that none of the white men had the necessary attributes to lead such an expedition. The only one who could be considered so was the zoologist on board, Dr Heinroth, and that Herr Mencke would hand over the leadership to the latter was, as was generally known, out of the question.

Having arrived at the anchorage south of the main island, an expedition base was chosen at an apparently suitable site on the beach of the main island, and the workers began to set up camp. As soon as the undergrowth was thinned out and a limited space cleared, tents and huts were erected and food and trade goods were brought ashore. Meanwhile they had made the discovery that many essentials had been forgotten and the vessel Eberhard received the order to steam back to collect the missing items. Meanwhile, Herr Mencke, with his secretary, Herr Caro, and Dr Heinroth, as well as seaman Krebs and about forty well-armed natives, settled in to camp. Not much was seen of the natives of the island; a few dared to approach timidly, the majority kept a respectful distance, as was to be expected of such a ‘faint-hearted band’.

In the first few days everything still went well, and they lay down to sleep quite peacefully. Whether watches had been placed seems doubtful. On one of the following mornings the order was given to take all the Mauser carbines apart and clean them. Dr Heinroth was already busy, Herr Mencke and Herr Caro were still asleep. Natives were observed creeping through the undergrowth not far from the camp, but since they were regarded as harmless they were left unchallenged. But suddenly a number of them fell upon the camp. Herr Mencke and Herr Caro were mortally speared straight away and Dr Heinroth was slightly wounded. Seaman Krebs stood in front of the tent with a loaded repeater and attempted to open fire, but found that the cartridges were spoiled and would not explode; he too was put out of action temporarily by a severe wound and fell senseless to the ground. Fortunately he regained consciousness fairly quickly, and was able to get the wounded Mencke into the boat in the general confusion. At first glance resistance was unthinkable, but soon several of the crew succeeded in getting their rifles ready and opening fire, upon which the attackers rapidly withdrew with several losses. The severely wounded Mencke was taken to the station on Kaléu where he eventually succumbed to his wounds. The body of Herr Caro had been taken away by the attackers. Upon the return of the yacht Eberhard, Dr Heinroth went aboard with his group and the First German South Seas Expedition was disbanded.

When the imperial governor of the protectorate again visited the island in September 1903, he found Mencke’s grave opened and the bones removed. The only remains left of the unfortunate traveller was a piece of the upper jaw, recognisable by the gold fillings in the molar teeth.

After this outcome the natives became intrusive and killed several of the station workers, upon which the firm of Hernsheim & Co. dismantled their station and the natives were left to themselves once more.

A consequence of the renewed attacks on the part of the natives was that the imperial cruiser Kormoran was ordered to punish the islanders. A not insignificant number of St Matthias people were killed and several women and children as well as a teenage youth were taken to Herbertshöhe as prisoners.

I have dealt with the gradually developing interaction of the St Matthias inhabitants with the whites and the consequences rather extensively because the incidents on the whole give a genuine picture of the first approach of two races so basically different. Scarcely a single South Sea island can be named on which the same events have not taken place. However, we hope that the natives may be spared further nasty experiences. Trade does not lure any settlers to the islands in a hurry, for they are poor in profitable products, but the prisoners languishing in Herbertshöhe, who are enjoying humane and caring treatment will, on their return to their homeland, perhaps become the link to a peaceful approach. In the meantime, through the accounts of the three captive women it has become possible for the author to expand and correct his observations made in 1900 (Globus, vol. LXXIX, no. 15), although here, as everywhere else, there is still very much to learn.

The island of St Matthias lies about 1º37’S latitude and 149º40’E longitude and stretches from north-west to south-east over a length of 33 kilometres with an average breadth of about 11 kilometres. Off the southern side of the main island lie a number of raised, low coral islands, partially forming an atoll which is separated from the main island by a deep, navigable passage. In this strait ships find a secure anchorage.

The main island is mountainous and the widely visible high point, Mount Malakat, reaches approximately 520 metres. The shoreline is without exception steep, with a narrow offshore reef which expands up to 3 kilometres only on the south-western side. The north-eastern coast is flat and sandy on its southern half, and the mountains recede up to 1 kilometre from the beach. Here a number of 141villages lie scattered among the palms. According to the natives the mountains are uninhabited. The low coral islands in the south are likewise inhabited, but not populous. The small islands, like the main island, show clear signs of uplift over long intervals. The limestone cliffs are deeply undermined almost everywhere by the sea swells, and also at places where today the sea does not reach. The central part of the island consists, as far as I had opportunity to observe, of volcanic rock.

Fig. 51 Map of St Matthias

The soil appears to have little goodness on the south-western side; the mountain slopes show broad grass fields and extensive jungle with many pandanus trees. The north-eastern side of the island appears to be more fertile; here the mountain slopes are partially covered with thick forest and coconut palms occur in greater stands as well. The small group is therefore of little agricultural importance for the time being.

The two main districts on the south-eastern end of the island seem to be called Elemakunaur and Roitan; north of these the very well populated districts of Itasidl and Etalat lie on the east coast. The names of the small islands on the reef on the south-western side are: Noanaur, Kaléu and Vangalu. The islands on the atoll to the south-west are Emusaun, Eiongane and Emanaus. A general designation for the entire island group or for the main island, does not seem to exist.

It has always been my greatest desire to encounter such a population as we find on St Matthias – such ‘savage’ people; people who have not the slightest semblance of a civilisation in our sense of the word. Here we find ourselves abruptly set down in a piece of antiquity, an antiquity that extends much further back than the beginnings of the civilisation known to us, or of that which we usually call ‘history’. It was left up to modern times to come to realise that it was finally time to study the prehistory of humankind, and in museums and collections we find the creations of primitive people more or less totally lumped together, but the actual study of the children of nature themselves still contains great gaps. We investigate the depths of the sea, we attempt to reach the North or the South Pole and spend large sums of money for these purposes. Would that we could finally come to realise that for the foreseeable future the sea with its depths will be preserved for us in its present state, and likewise the North and South poles, but day by day the prehistory of our own kind is fading from the surface of the planet, and that we should make every effort to gather and preserve the remains of these primitive cultures, for modern civilisation, which is spreading further and further over the planet is acting like an eraser, irrevocably obliterating all the old signs and features.

St Matthias is one place where we are set down suddenly in the middle of a slice of human antiquity. Iron is totally unknown; knives and other iron tools are rejected in trade dealing. On the other hand they reach greedily for red beads or red scraps of material and at the sight of these treasures the thick lips draw back into a covetous grimace, so totally different from a real smile of satisfaction, which seems to light up the face from within in more sophisticated peoples.

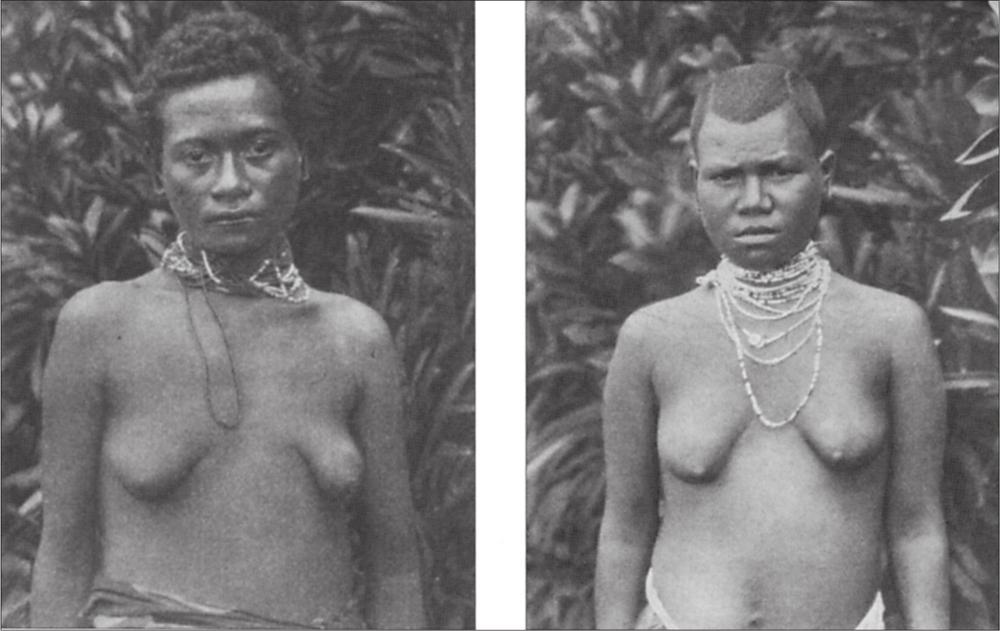

The islanders are of medium height and dark brown skin shade. I was previously inclined to regard them as pure Melanesians, but having been able to observe at close hand the prisoners brought to Herbertshöhe, I have, however, modified this opinion, coming to the conclusion that they are Melanesians with a fairly strong Polynesian admixture, probably originating from the Micronesian islands. A number of natives have crinkly hair with small ringlets, as on New Ireland and the Gazelle Peninsula; however, there are numerous individuals as well who have curly or even completely straight hair. The crinkly haired islanders are always darker than the islanders with curly or straight hair. The prisoners in Herbertshöhe show the various transitions quite clearly; in particular, observation of a girl born of a woman there, whom my wife adopted after the mother’s death, gives an indication that we are dealing with a mixed race, but one in which the Melanesian element is dominant. The hair on the child’s head was almost completely straight in the first months after birth; with increasing age the hair became curly, although it did not combine into the characteristic, corkscrew, thickly spiralled tufts of pure Melanesian children of the same age. The numerous pure Melanesian children in my neighbourhood provided good comparative material. Also, the skin colour differed from the chocolate brown of my neighbourhood children, in that 142she showed a tinge of grey that I have observed nowhere else.

Fig. 52 Men of St Matthias

The prisoners in Herbertshöhe have shown that they are not without intelligence. They very quickly learned the pidgin English used in the archipelago, showed great preference for ornaments and bright clothes, and would not put up with anything from the station workers, with whom they mixed, in spite of being the minority. I have come to the conclusion that they are quite highly endowed mentally, but are, unfortunately, irritable and hot-tempered.

The hairstyles of the islanders are nothing out of the ordinary. The women wear their hair cut short as a rule, the men let it grow somewhat longer, but not so long that it completely covers the neck.

Actual clothing for the men is out of the question. They are without exception circumcised and occasionally cover the glans with a Cypraea ovula just as in the Admiralty Islands. The local name of this snail is bule (in Samoa the same snail is called pule). Many of these shells whose internal windings are broken away, have a smooth, naturally white outer surface, others are decorated with a pattern of straight lines, triangles and zigzags, which are accentuated as black against the white background by layers of dirt.

Figs 53 and 54 Women of St Matthias

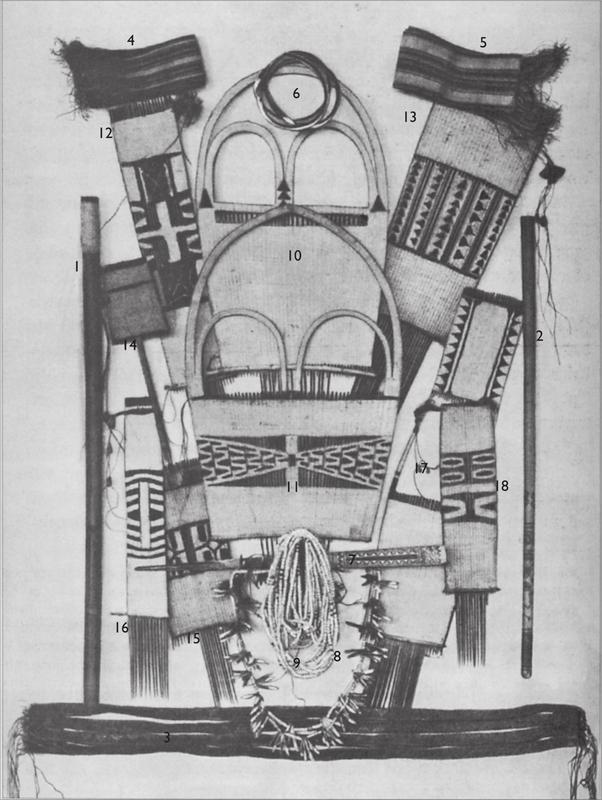

The men wear large, carefully made combs (zili) of various shapes as head ornaments. These combs are made from ribs of small coconut palm fronds laid side by side, overlaid with a weave of threads like a dense fabric; they belong to the finest products of the islanders, and can be regarded as typical of St Matthias (fig. 55, nos 10 to 18). They do not serve as combs in the true sense of the word but as head ornaments; the densely packed teeth of the comb are pushed into the dense mass of hair, and serve simply as a means of fastening the characteristic 143hair decoration; the upper, free section forms a rectangle painted white and russet with bigger and smaller rectangles, semi-circles and trapezes attached. These swing to and fro with every movement of the head. This head ornament is fixed behind the ear either on the left side or the right.

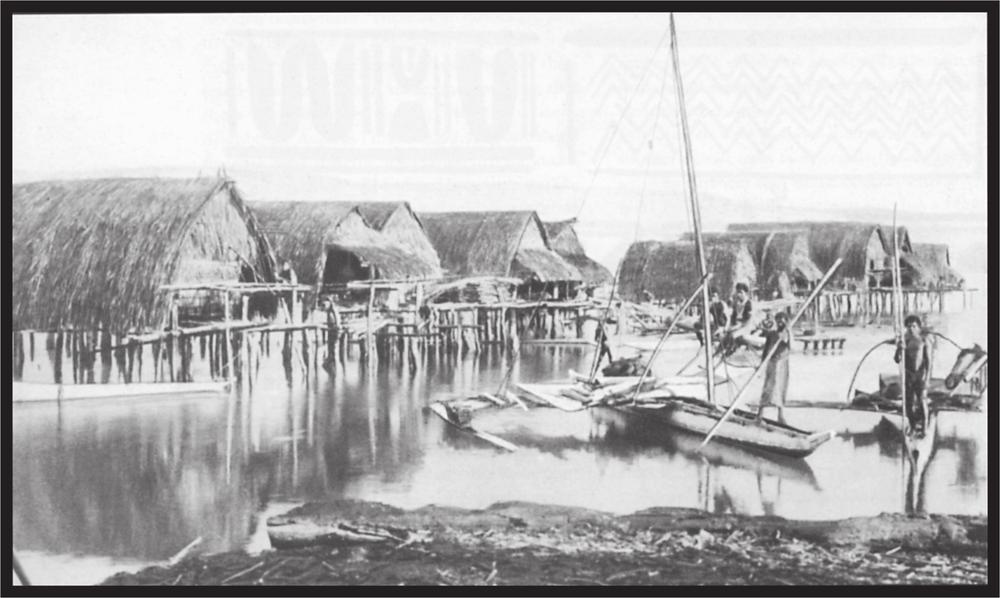

Plate 21 Village scene on Squally Island

Furthermore, the men wear a loincloth (aili) about 2 centimetres wide, woven from black and golden-yellow strips of fibre so that alternating black and yellow triangles are formed; three or four of these girdles are often attached side by side, forming a broad-banded girdle (fig. 55, no. 3).

Around the neck both men and women wear long strings of circular shell discs named wungoos; the pale grey discs are interrupted at greater or lesser intervals by one or more black discs (fig. 55, no. 9).

Both this type of girdle and the string of shell discs are found also on the Admiralty Islands. On a walk I found the material from which the strings of shells are made: a small Conus snail about 1 centimetre long, from the thick upper end of which the discs are made. They are made from the same Conus snail on the Admiralty Islands.

The women wear rather more clothing. Two carefully made, quite fine mats are attached to a girdle in such a way that one of the mats hangs down in front and the other behind, extending from the waist to the knees. The local name for this item of clothing is urungarang. The girdle is about 5 to 6 centimetres wide and about 1 metre long. All girdles, bais, are produced from fine, yellow-grey, red and black woven fibres in such a way that red, white and black long strips appear in varying sequences of rows and breadths. At both ends the longitudinal fibres form a fringe about 8 to 10 centimetres long (fig. 55, nos. 4 and 5). These girdles bear an astonishing similarity to examples from Kusaie called tol; such girdles also occur on the Banks and Santa Cruz islands. In Kusaie the girdles are woven, likewise on Santa Cruz, where the loom has been introduced from the Carolines. I already had no doubt on my first visit that on St Matthias also, these girdles, like the previously mentioned mats of the women, were woven. However, I was not able to catch sight of a loom. Only on a second visit in 1905 did I succeed in establishing that a loom did exist, and that it did not differ significantly from that used on various Micronesian islands (see page 148 below).

Furthermore, both sexes wear fairly roughly polished armrings (mare) made from Trochus, as well as small turtle-shell rings (puatil) about 7 millimetres in diameter, in the nasal septum. The ear lobes are pierced and greatly enlarged, often decorated with numerous turtle-shell rings of the type previously described, just as on Ninigo, Aua and Wuwulu, where, however, the rings are significantly larger. As characteristic ear ornaments I also observed thin, circular discs of turtle shell about 2.5 to 3 centimetres in diameter; the surfaces were pierced by small, triangular openings forming a regular pattern. From the centre to the edge ran a slit, by means of which the disc was pinched onto the ear lobe.

The huts (ale, Samoan = fale) are very primitive and extremely dirty inside. A pandanus roof rests on low posts, just high enough to be able to stand upright beneath it. I did not notice sleeping places 144anywhere; the inhabitants appeared to sleep on the bare ground without anything to lie on. I found a fireplace in every hut and beside it a small heap of fist-sized stones which were obviously used in a glowing state for cooking food.

Fig. 55 Objects from St Matthias and Emirau

Household utensils were not available in a wide range nor in great numbers. Small wooden bowls 25 centimetres long and 12 centimetres wide were seen here and there, too small to be used for preparation or presentation of food; they were probably used for mixing ochre with oil, which both men and women rubbed into their hair and bodies.

Coconut shells (teo; the ripe coconut bears the Polynesian name niu) usually surrounded in a mesh net of fibrous cord and attached together in pairs, serve as water containers. Little baskets, closely woven and conical or elliptical in shape, were also used. They usually contained all kinds of small items, sharp pieces of shell, little bundles of leaves, sea snails and so on; the weave of these little baskets was the same as those similar objects that we know from the Admiralty Islands or from the Baining. Small net purses (zeri) with circular wooden rims, as well as small pouches (tess) prepared undoubtedly from woven material, were also used for storing small items.

Coconut scrapers (aisamsap) of a unique shape were found in the huts. A piece of thin trunk or 145tree branch was prepared in such a way that four lateral branches formed two front limbs and two hind limbs; a shell (Cardium?) was attached to the end, projecting somewhat over the front limbs, for scraping the coconut. To use this, the natives sat crosswise over the trunk section in order to give the necessary firmness to the instrument. This rough form of coconut scraper recalls the carefully prepared instrument of the Tauu islanders.

Among the less common household utensils belongs a short pounder of Tridacna shell; such pounders were about 12 centimetres high, and 7 centimetres in diameter at the lower, circular end, and 6 centimetres at the upper end. The lateral surfaces and the lower end were smoothed by polishing.

In and around the huts we also found fishing nets of various sizes. Several were very long – I estimated them to be about 100 metres long with a width of 1.5 metres; the lower edge was weighted with sinkers, sometimes stones and sometimes lumps of coral and sea snails. Small, pierced pieces of wood and the cork-like fruit of the Barringtonia served as floats. The big nets were called ubén (Samoan = ‘upega, pronounced upenga). Besides this, small hand nets, kea, were used on knee-shaped wooden frames. Fishing seems generally to be a principal source of food to the natives. Hand tools for the preparation of nets consisted of wooden needles with a slit at each end to take the thread. The net needles, aisiel, vary in length from 25 to 50 centimetres; both ends were bowed outwards like a lyre to take the thread. The shank itself was circular and the whole thing was polished smooth. To regulate the mesh size, they used a short, smooth little wooden board or a piece of turtle shell of varying width.

I was not able to acquire fishhooks, uos, on my visit; the iron fishhooks that we offered the natives were scornfully rejected. The prisoners at Herbertshöhe tell me, however, that fishhooks, some of shell material, others of turtle shell, are known.

Hand tools were present in the form of sharpened mother-of-pearl shell, used for cutting and scraping. In addition there were axes, iama, which I will describe in more detail. All specimens offered to us had a blade of Terebra shell, the thick end of which was ground obliquely to produce a semicircular cutting edge. Blades of stone or Tridacna were not seen. A knee-shaped piece of wood served as an axe handle and for holding the blade. Blade attachment is twofold; they are either firmly attached to the short arm of the knee-shaped wooden haft by means of rattan strips, or the blade is firmly stuck into a conical wooden sheath, which is bound to the haft in such a way that the blade can be turned in different directions.

The foodstuffs of the natives consisted, as far as we had opportunity to observe, of taro (ási), bananas (uri), breadfruit (ulu; Samoan ‘ulu) and several items from the plant kingdom unknown to us. Everywhere taro and bananas were cultivated beside the villages in quite extensive stands. Coconut palms were characteristically only sparse; extensive stands were not present on the small low islands. Small isolated stands occurred on the south-east side of the main island as well as on the northern end. Most frequently, however, the coconut palm appeared on the southern half of the north-eastern coast since there appeared to be a denser population, with whom we unfortunately did not come into contact. There are no dogs or chickens; a necklace of shell discs also contained a number of cuscus teeth, and this easily caught animal provided a food source here as on New Hanover and New Ireland. Pigs are not numerous on the small islands but should be present in great numbers on the main island. The coral reef and the sea seem to offer the natives a rich contribution to their nourishment; we saw canoes going out fishing every day, and fish (koko) were frequently offered to us for trade.

Areca nut (búa) together with betel pepper and burnt coral lime (sangina) serve as an enjoyment and a stimulant. The lime containers (raba or gaba) had the same shape as those on the Admiralty Islands, and were decorated on the outside with burned-on patterns which were also reminiscent of that island group in their design and shape. The lime spatulae (rama) were mostly simple, little sticks; however, odd, black hardwood ones, whose upper end was decorated with carved zigzags and parallel lines, were also bartered.

Triton snail shells (kaúe), with a circular hole bored through the side, serve as signal horns. Flutes of bamboo canes (tukutaue) with engraved burn patterns, and of the shape familiar on the Gazelle Peninsula, were offered as barter items. I did not see wooden drums during my visit, but the slit drums familiar everywhere in Melanesia ought to occur here as well.

As a result of the very primitive tools, canoe building is not at a high level. The canoes (olimo) consist of hollowed-out tree trunks with outriggers and float attached. The size varied; there were small specimens for one or at most two passengers, while others held eight to ten natives. No ornamentation, either in the form of painting or carving, was observed on the examples that we saw. The vessels were propelled by paddles (hose) with a broad, lance-like blade and a shaft about 1.5 metres long.

The islanders’ weapons occupy a far higher level of accomplishment; the spear (walau) is one which by its entire finish belongs among the most superior products of Melanesia. Both the careful carving and the extraordinarily tasteful and rich decoration of both ends of the spear give this weapon of the St Matthias Islanders the right to be placed in the front rank of artistic carving from Melanesia. Therefore the spears certainly deserve to be described in detail.146

Fig. 56 Decoration on spears and dance sticks

147The material consists either of palm wood or a tough, dark brown type of wood of medium weight. The length of the spear is about 2.5 metres on average. Two different types can be distinguished; those with their entire length produced from a single piece of wood, and those with a shaft consisting of an attached piece of bamboo tube. This piece of bamboo, about 0.5 metres long and about 10 centimetres in diameter at the thickest end, is pared very thin over a 10 centimetre length at one end; this pared end is split many times, and the shaft end of the spear is set into it. The lamellae of the pared cane are bound firmly to the shaft of the spear with fine, twisted fibrous cord, so that the spear and cane form a single tightly bound unit. This binding of the spear shaft to a bamboo cane is very reminiscent of similar binding of both parts on New Hanover and northern New Ireland.

The spears made from a single piece of wood are without decoration at the butt end. Those with shafts inserted into a section of bamboo are for the most part richly decorated at the end of the shaft, while the bamboo tube tied on is only rarely, or only very little, decorated with carvings. About 50 centimetres of the shaft, above the bamboo tube, are most carefully decorated in this type of spear, partly by carved parallel lines running round the shaft arranged in different ways, and partly by various ornaments in relief, which in my opinion are based mostly on leaf and flower motifs (figs. 56 and 57).

There follows a 50 to 70 centimetre portion of the shaft which is completely smooth, mostly circular in cross-section, and 2.5 to 3 centimetres thick. This part of the spear is held in the hand when the spear-thrower holds his weapon in readiness for battle; in old specimens it seems as though it is polished, as a result of use.

Following this smooth part comes the real tip of the spear, which is most carefully and richly decorated from the 70 to 80 centimetre mark to the very tip. The design of the decoration is similar to the shaft, but figures by far predominate and line motifs diminish.

The extreme point of the spear is smooth, circular in cross-section and about 15 to 18 centimetres long, then follows a row of barbs, on one side as a rule, although those with two opposing rows are not infrequently found. The barbs and their arrangement recall in many cases those from Wuwulu and Aua.

Individual spears have a number of notches, which may be regarded as a stunted form of barb, below the actual point with the sharply protruding barbs. This actual spear point is bordered by one or more bunches of fibrous material about 5 centimetres long. The subsequent portion up to the smooth middle section is beautifully decorated.

The spear points, and the inner side of the barbs in particular, are almost always painted red and black. By rubbing with burnt lime into the deepened grooves and surfaces, the surface relief decorations appear, and in the dark wood colour they stand out effectively against the white background. Around the bamboo tube, which is almost always painted white with lime, run narrower or wider lines in red or black at the shaft end.

As well as the previously described battle spears, the islanders use a multi-pronged spear for fishing. This is completely without decoration and consists of a thin pole about 3 metres long, to the end of which six to ten tips of hardwood are attached en masse.

At the time of my visit to St Matthias in 1900 we obtained a few sword-shaped objects of blackstained woods, about which it was not possible to ascertain precise details of their use. Through the punitive expedition of HIMS Kormoran, a larger number of these objects came to the Gazelle Peninsula, and the prisoners at Herbertshöhe said these objects were dance batons that the women held in their hands in certain dances. The local name for these dance batons is rama. They call to mind similar objects from the Rook group in the Carolines.

These batons are between 1 and 1.5 metres long. The lower end is sharply tapered like a spear, mostly circular in cross-section, but partly elliptical too. The upper third of the baton is broader, often widened up to 5 centimetres and strongly elliptical in cross-section; it terminates in a type of handle, often in the shape of a sword hilt from the Middle Ages. This entire upper part is most carefully decorated on both sides; the grooves and indentations are rubbed with lime, like the spears. Also, the decorations are on the whole the same that we see on the battle spears, but others occur as well, which find no place on the spears because of their shape.

After the preceding had already been written, in April 1905 I again had the opportunity of visiting the island and, in particular, of observing the people of the east coast of the main island. These, as might be expected, are completely identical with the population on the southern offshore islands, although somewhat more powerful, probably as a consequence of better nourishment. The huts of these villages are more roomy and are kept in a better and cleaner condition. In many cases they appear to be inhabited by several families together and have low plank beds for the inhabitants. However, besides this there are also bachelors’ or men’s houses which are never entered by women, and which are always recognisable by a great quantity of weapons. After the earlier events I did not expect a very friendly reception, but was pleasantly surprised to find that the natives were friendly and trusting everywhere and bore no ill-feeling. The rebuke given them may have had much to do 148with this; however, I believe that the friendly visits made by the imperial governor and the sojourn of several islanders in Herbertshöhe had far greater effect. I brought a few of them back to their home, and through them I was able to make myself understood to some extent to the islanders, via the frightful pidgin English, the lingua franca of the South Seas, which of necessity they had had to learn during their stay on New Britain.

I found that my earlier observations were confirmed, and had the opportunity of seeing the major part of the population. I have come to the conclusion that the total population amounts to not much more than 1,000. The men seem to be decidedly in the majority. The women, contrary to the Melanesian style, mixed unceremoniously among the men and were not at all shy or reticent. They showed fewer signs of hard work, and apparently enjoyed much more freedom than is customary among Melanesian tribes.

Although the islanders are not true seafarers and very rarely leave their coasts, on the eastern shore, there were large, carefully constructed canoes which I had not observed earlier. These stately barques are up to 24 metres long and are carefully carved and painted at both ends, not without artistry. The wooden uprights to which the outrigger is attached are carved and daubed with bright colours. The open-work carving vividly recalled similar productions found on the canoes on Kaniet, but particularly on both ends of the boat-shaped wooden bowls there. These large canoes are able to take thirty to forty full-grown passengers.

On the island of Emusaun I was shown a shattered Admiralty Island spear, thus proving that there is occasionally contact with the western neighbours. As far as I understood, they calculated five such visits, with the observation that the guests were not regarded well because they were warlike and quarrelsome. This matches the familiar attitude of the Admiralty Islanders. Also, even today they tell me at Papitálai on the Admiralty Islands that the now-dead chief Po Sing had been driven ashore on Emusaun years ago and stayed there for a short time but, because of the hostility shown towards him, travelled to New Hanover and returned home from there. It may not have gone so well for all visitors. This information is nevertheless interesting, as it shows that intermittent immigration took place from the west, and we can probably assume that the real settlement took place from there years ago, which is why even today there is great agreement in many ethnographic characteristics with the western neighbours. In Itasidl there are traditions of an immigration from the north, but this immigration must have been a long time ago, and furthermore it was not possible for me to ascertain where the immigrants came from, although the north was indicated with great assurance. However, that an immigration has also taken place from there seems beyond doubt to me and demonstrated especially by finding the Micronesian weaving loom on both St Matthias and Kerué (Emirau). This cannot have been imported from the Admiralty Islands, where it is unknown. The apparatus called solo or solu, is only somewhat smaller than the Micronesian weaving loom, so that one is unable to weave broad material. Weaving is the task of the women who, in a sitting position, keep the apparatus under tension by holding one stretching stick firmly with the feet, and the other by a girdle laid round the waist. Through weaving they make the narrow loincloth named bais, which is worn both by men and women, as well as clothing mats for the women. These are 20 to 25 centimetres wide and, like the girdles, are produced from naturally coloured and russet-dyed banana fibres. These mats were worn in various ways, either as aprons hanging down in front and at the back, or as three lengths sewn together and worn as a loincloth extending round the body.

About 17 nautical miles south-east of St Matthias, at 150º3’E longitude and 1º48’S latitude, lies the island, or more accurately the island group, of Kerué. Its main direction stretches from west to east, and consists of three individual islands, the middle or main island of Emirau and two small islets at the eastern and western ends, Elemusoa and Ealusau. The island is a raised coral reef, like the offshore islands of St Matthias, and is surrounded by reefs on all sides; the narrow arms of the sea which divide the smaller islands from the main island at eastern and western ends, are barely navigable to boats at low water. The entire length from east to west is about 8 nautical miles. The southern coast runs fairly regularly, and forms a small embayment only in the middle, with several islets on the reef; the northern side has a bigger indentation at the eastern end. The island is completely wooded and carries a fairly large number of coconut palms, particularly on the south coast and at the western end. Here dwells the population, which might not be more than 500 in all.

The population does not differ from that of the St Matthias group, although as a result of more abundant food resources they appear better nourished and more robust than the latter.

The language is exactly the same as on St Matthias and reciprocal trade exists, especially for the trading of spears, which are made in great numbers on Emirau.

On my visit I found the islanders friendly and forthcoming, although inclined to theft if they thought they could get away with it unnoticed; but in this regard they did not exceed the other South Sea islanders, and it was almost entertaining with what shrewdness they made all kinds of desirable small items disappear. The houses, as on St Matthias, are better constructed and lie on the beach, grouped into several small villages. Each such village is governed by a headman, who was always the first introduced to me on my visit. This man seemed to exert a very significant influence on his village, and I could observe that his decisions were carried out without discussion. The women had, if possible, greater freedom than on St Matthias, and did not take much advice from the men.149

Fig. 57 Decorations on spears and dance sticks (plant motifs, derived especially from coconut palm leaves)

150As a unique peculiarity, I noticed here that besides the white Cypraea snail shell, the men also used a small yellow Kürbis species as a penis cover, but this is not bored through laterally as on Angriff Harbour in New Guinea, but provided with an opening in the end.

I had the opportunity of observing a festive gathering on the western end of the island. In front of a big, new hut a rectangular site was enclosed with brushwood and undergrowth; women apparently were not allowed to enter, although they were assembled in great numbers outside the place of festivity and were busy preparing food. About a dozen boys aged from six to ten years sat inside the house and I could assume with certainty that the people were in the process of celebrating a circumcision ceremony, although an evasive answer was given to my inquiry. The boys were adorned with girdles and necklaces and still uncircumcised; the feast was therefore probably a customary pre-celebration on such occasions. In the middle of the rectangular site sat a group of about thirty men and youths who intermittently intoned a loud song. This, heard at some distance, bore a great similarity to the fervent celebratory singing of a Catholic church service, and always ended in a drawn-out, gradually fading tone. They were in no way disturbed by my presence, which must have appeared the more noteworthy, since I was probably the first white person ever to have visited the island, and outside the place of celebration they gathered round and gazed at me in astonishment. Beyond the enclosure they were engaged in all kinds of pastimes; the women left their task and surrounded me, laughing and gesticulating, extremely pleased when I placed a few bright glass beads in their tiny outstretched hands. The men looked on laughing and for their part were just as happy when I handed over a fishhook, a scrap of red cloth or a 2-inch nail.

They were undoubtedly informed on the island of the earlier events on St Matthias, as the headmen were keen on signifying to me that the people of their island were good people, while on the other hand the people of St Matthias were bad. However, the St Matthias interpreters accompanying me laughed quite disbelievingly at this assertion, and recounted that the Emirau people began fights not infrequently during their visits to Elemakunaur and behaved in a very unruly way.

Plate 22 Pole village of the Moánus on Ndruval

I was able to ascertain here that on both island groups various classes existed, which had certain totem signs and for whom marriage within the class was not permitted. Unfortunately my interpreters were not able to explain to me in greater detail. However, since I was successful in recruiting a large number of youths from both St Matthias and Emirau 151as workers, I will in time be able to obtain from them extensive accounts on customs and ways of life of these groups of people.

The land designated on the maps as Squally Island does not exist in this form. According to the coordinates the island lies at 150º38’E and 1º48’S, and is a small, raised coral island, no larger than 150 hectares; it is surrounded on all sides by reefs and covered in forest in which here and there a few coconut palms are visible. As we approached the small island, several small, very primitive canoes came towards us, but we were unable to persuade the people to come alongside. However, their greed allowed them to forget their fear, to the extent that they approached close enough to pass us a plaited basket on a long pole with the aim of receiving any gifts. Meanwhile their entire bodies were trembling and they seemed to want to conceal their fear by loud talking and shouting. Unfortunately we could not understand a word; neither could the St Matthias people nor the New Ireland and New Hanover natives on board understand a single syllable of the language. This was very rich in vowels, and almost every sentence ended in a long, drawn-out ma or ha, which seemed to be a source of great amusement to my native companions. We had to heave-to off the island during the night and could land only the following morning. Numerous torches on the offshore reef during the night revealed that the natives were keen fishermen. The following morning the canoes approached again; however, as I lowered both boats into the water and steered for the shore, they followed at a distance. The entire population had gathered on the beach, about 150 in all, and it was evident that they had hostile intentions. On the reef stood a whole line of especially battle-spirited heroes, who held long lances in their hands, ready to throw. The rest of the population had placed themselves behind, some armed with wooden clubs, others holding lumps of rock in their hands; even women and children were armed. Since it was up to me to avoid a hostile encounter at all costs, I applied myself first of all to talking. Now this is not an easy task when neither party has the slightest knowledge of the other’s language, but a knife displayed, a bright string of beads, or a strip of red cotton material replaces language in such cases. This attempt at approach lasted for over an hour. Soon greed drove first one then another to my boat, and each time he went back with a gift, which aroused general amazement. Finally I was able to assume that they were convinced of our harmlessness, and allowed both boats to pass through the breakers to the beach.

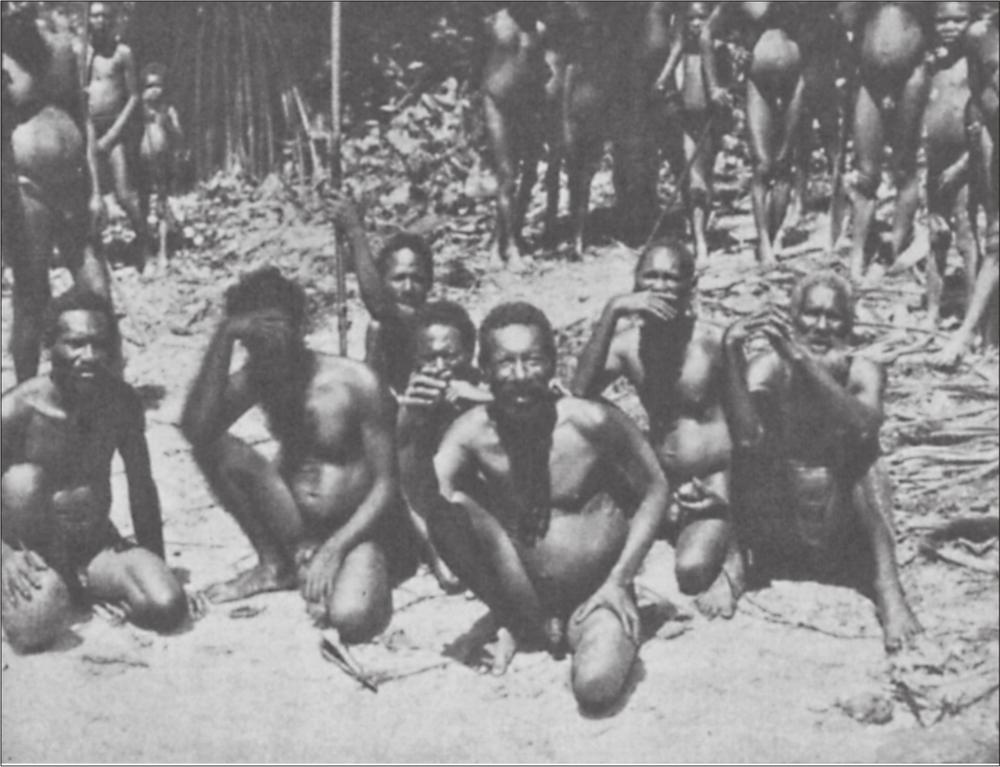

Fig. 58 Group of men from Squally Island

Immediately we were surrounded and the greed of the individuals had to be gratified. This apparently pacified them; the bolder lance-bearers laid down their arms, I took the missiles from the stone-throwers, and gradually a state of armed neutrality developed. With an armed guard of four natives and one white man, I was now able to take a further venture. That morning I had observed that the natives all came from one direction, and anticipating the village there, I set about finding it. However, first of all I thought it advisable to 152give the islanders a small firing demonstration, and I fired several shots at a tree trunk washed up on the beach. At each shot the entire population ducked, as if on command; the demonstration, however, was a success, since as I broke off for the village the whole crowd followed me at a respectful distance. After a walk of about ten minutes I reached the village. This lay behind a strip of bushes and trees right by the beach and formed a long street with the huts of the natives on both sides. The huts were very primitive, and consisted of leaf-covered roofs resting on the ground, with the owners’ plank-beds fixed below. Besides these dwelling huts numerous smaller buildings were also present, serving as food storehouses. These were erected on four man-sized pandanus poles, about 2 to 3 metres long and 1 to 1.5 metres wide. The roofs consisted of pandanus mats. The poles were wrapped with pandanus leaves, whose smoothness prevented the island’s numerous rats from visiting the storage space. Similar huts are known on Matty and Durour and on the Palau islands. A fair amount of fishing equipment, submersible nets, hand-nets and draw-nets were present in great quantity, otherwise the houses contained nothing of consequence. Having wandered through the village I set about taking a few photographs. The setting up of the camera was regarded with great mistrust each time, my guard covered my back and my revolver lay on the camera so that I was covered on all sides, and after distributing small gifts I was able to take a few useful photographs. The open, although not to the point of active, hostility of the natives persuaded me to cut my visit short. The firing of my gun had undoubtedly intimidated the people; however, I might assume that they did not know the deadly effect of firearms, and I knew from experience how easily, in this case, natives were led into undertaking an attack as soon as their initial shyness has dissipated. We therefore withdrew in good order back to the landing place, and I had already climbed into the boat when the natives who had followed us attacked the boatman, who still wanted to distribute a few beads on the beach, with clubs. One of my coloured men immediately fired a warning shot, which had the desired effect, as the crowd promptly dispersed. However, I had yet another unexpected delay as one of the St Matthias people accompanying me, armed with a spear, suddenly let out a loud war cry and in long bounds, brandishing his spear, set off after the islanders. The boatman and two of my people then had to be sent in pursuit to bring back the bold warrior. The latter had chased the whole crowd right to the village; however, here the natives made a stand, and a veritable hail of stones dampened the courage of the pursuer to such an extent that he promptly retreated. This again emboldened the islanders to a full-scale attack, and I was happy when I finally had all the people in the boats and could go back out through the breakers. Several shots held the attackers at a respectful distance; nevertheless a number of their missiles reached us, fortunately without causing injury. After we had passed through the breakers the whole crowd sat down peacefully on the shore and watched our re-embarkation on the schooner.

Fig. 59 Group of men from Squally Island

Although my stay on the island had lasted barely two hours, I was still able to get quite a good picture of the natives.

The type is without doubt pronounced Melanesian, but the relatively large number of individuals with curly, almost bristly hair reveals the Micronesian influence here too. The men are of medium size, dark brown and quite powerfully built. Circumcision was found in all of them, even in relatively small boys, so that the procedure must take place right in early childhood. The hair was worn medium length or short; the style of beard is characteristic, in that the men let the goatee beard grow long and arrange it in two to four long, twisted plaits which hang down as far as the navel. So that the long curls of the beard are not in the way when working, the ends are bound together with a cord and the latter is fastened round the neck so that the tips of the beard lie under the chin. Several old men had unkempt, bushy full beards, grey-brown in colour without curls, about which they seemed otherwise quite proud. Hair and beard, if not grey by virtue of age, is jet black in colour, and demonstrates that treatment with burnt lime does not occur. Likewise, the teeth were dazzling white; evidence that the enjoyment of betel is unknown to the people. All the men are completely naked, and the penis shell is also unknown. The women are smaller than the men and somewhat paler; the head hair was cut short in all of them; I saw young women who had scarcely outgrown childhood who were already 153mothers, and I believe that it might be subscribed to this circumstance that the entire female sex gave the impression of being aged excessively early. The women, according to Melanesian custom, wore a woven bark apron which extended round the lower body. I was successful in acquiring some parts of a weaving loom, unfortunately without any weaving started; sadly this find was lost in the later uproar. Such an apron is about 125 centimetres long and 50 centimetres wide and made from two pieces sewn together. They are very roughly prepared from naturally coloured pandanus leaf fibres, and resemble coarsely woven jute material. Moreover the aprons, after having been woven, are processed again by the women pushing thick fibre cords through the long threads with an awl, so that it appears as if the admixture consists of alternating thin, twisted threads and thicker untwisted strands. I was able to acquire such an apron clearly showing this further processing. Very young girls run around totally naked.

The islanders seem to have been cut off from all outside influences for a long time. I observed no ornamentation, and apart from a few elongated wooden bowls, no household equipment. As tools, there were roughly worked Tridacna axes with a barely usable cutting edge. The blades were fastened to a knee-shaped handle by means of a woven bark ring.

The spears, or more accurately lances, are 5 to 6 metres long, roughly made out of the hard wood of the coconut palm, scantily smoothed and of great weight, so that they most definitely would not be reckoned amongst the fear-invoking weapons. Because of their weight they were not thrown, but were used only as stabbing weapons in close combat. Each club being presented was on the other hand used as a weapon, and the coral rocks were above all the most effective means of defence. Both men and women knew how to throw fist-sized lumps with great precision over long distances, and I was heartily grateful, at the later attack, when we got out of range. Reminders of St Matthias were given by several of the lances having their lower ends pushed into a bamboo tube. The canoes are simple tree trunks, pointed both front and back and with the usual outrigger and float; most canoes were reckoned to be for two or three passengers; however, on the beach lay a large canoe which might have held ten men. At both pointed ends it was provided with a decoration consisting of a prominent knob, which bore a distant resemblance to a fish head with wide open mouth, although I do not want to assert that it should actually represent this.

Besides the previously mentioned fishing equipment there were also fishing rods about 3 metres long with a 5 to 6 metre line. For deep sea fishing they had an apparatus which I first took as an abnormal head ornament of the men in the canoes approaching us, as they had attached them to their locks in such a way that it hung down the back. However, I later found out that the apparatus was for fishing. It consisted of two bent canes fastened to each other in such a way that they formed an ellipse with fairly sharp ends. The longest diameter was about 50 centimetres, the shorter about 25 centimetres. The elliptical space between the canes was covered with a brown, paper-thin substance. The fishing cord was wrapped lengthwise around this apparatus. Neither on this apparatus nor on the fishing rods did I notice hooks; instead at the end of the cord two thin, sharpened little sticks were bound into a cross, probably replacing the fishhooks. They called to mind a similar apparatus in the Gilbert Islands which was used especially for catching flying fish.

That trade with whites probably occurred only quite rarely, mostly with passing ships, was revealed by the situation that no examples of modern industry were present. The only indicative item was an iron ship’s nail which was fixed into an axe handle and fashioned into a narrow blade. The items that I distributed, such as plane iron, knives, beads, looking-glasses and armrings, aroused universal, long-lasting amazement.

Because of the total impossibility of oral understanding I did not succeed in learning the name of the island; the map designation Squally Island must be discarded unconditionally. This name, which originates from Dampier, refers probably to Emirau and not to this island which absolutely does not match Dampier’s description. The sole discoverer is the Englishman Lieutenant King who, on his voyage from Sydney to Batavia in the ship Supply, sighted the island on 19 May 1790. His coordinates 150º31’E and 1º39’S are approximately correct. He named the island after Watkin Tench, the commander of the marines, and so all other names should disappear without further ado, and the name Tench Island be retained. From the individuals who came into view in their canoes, King gives a fairly good description of the islanders; on the other hand his assessment of the population, which he gives as 1,000 individuals, is much too high even for that time. The small island would not be in a position to sustain such a population, for coconut palms are only sparsely found and bear exceptionally small nuts; also the island is wooded, and the stands of trees show that large gardens have never existed. A few taro tubers no larger than a child’s fist were present; however, as well as this the fruit of the pandanus tree and that of Inocarpus edulis appeared to form a main food source. In any case fishing is the principal source from which the islanders take their nourishment.154