VII

The Eastern Islands (Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu)

East of the large Melanesian islands extends a long chain of small islands, mostly raised coral reefs or atolls, belonging geographically to Melanesia, but occupying a quite special position ethnographically.

Three of these small atolls, Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu, have been annexed by the German protectorate. A fourth group, Liueniua or Ongtong Java, by far the most significant, was German for a time but then by treaty passed into English hands.

Although the three German groups are of no great interest commercially and probably never will be, ethnographically they are of no small importance because in spite of being in a Melanesian neighbourhood, they are inhabited by Polynesians.

In volumes X and XI of the Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie I have reported extensively on these islands. Later, in the Abhandlungen der Kaiserl. Leop.-Carol. Deutschen Akademie der Naturforscher, Dr Thilenius, based to some extent on my earlier work, examined the entire island chain and discussed the origin of its inhabitants in greater detail.

Nuguria (Abgarris or Fead Islands) consists of two atolls divided by a deep arm of the sea. The southern one is the real Nuguria while the northern is called Malum. Both atolls stretch more than about 25 nautical miles along a main northwest - south-east axis. The maximum breadth of the atoll is about 6 nautical miles. The islands on the coral reef, of which the main island, Nuguria, is by far the largest, together encompass about 1,000 hectares. The group lies fairly distant from the larger islands – about 120 nautical miles from New Ireland and about 100 nautical miles from the northern end of the Solomon Islands. According to the map the position of the main island is about 154º50’E longitude, and 3º30’S latitude. The islands are provided with coconut palms and the firm E.E. Forsayth is carrying out a regular plantation business here. The company has planted out entire islands with coconut palms and can expect a significant income in a few years’ time.

For years the population has been in the process of dying out. The current number is about fifteen. In 1902 alone, sixteen died, particularly as a result of influenza. The natives’ physical resistance seems to be very low, and it will not be many more years before none of the present population exists. In 1885 when I first visited this small group I estimated the population to be at least 160 people.

Tauu, pronounced Tau’u’u (Mortlock or Marqueen Islands; Dr Thilenius names it incorrectly as Taguu), is likewise an atoll structure. It lies at approximately 157ºE longitude and 4º50’S latitude, and the total land area of the islands is no greater than 200 hectares. The distance from Nuguria is about 150 nautical miles. The nearest point in the Solomon Islands, Cape le Cras, is about 120 nautical miles away. The island, like Nuguria, was taken over by a European planter, who is exploiting the stands of coconut and is bringing the previously unplanted areas into cultivation.

The population is in rapid decline and currently consists of about twenty people. In 1885 there were about fifty. Had the European owner of the island not looked after the small population, they might have already disappeared from the scene.

The Nukumanu atoll (Tasman Islands) lies at approximately 159º30’E longitude and 4º35’S latitude, about 135 nautical miles east of Tauu and only about 25 nautical miles north of the large atoll of Liueniua (Ongtong Java).

The surface area of all the islands amounts to 250 hectares. Here also the main product is coconut, but not much is exported because in proportion to size the population is fairly significant, actually around 300 according to a census that I took in 1900. That the mortality rate is less high here and the population more resistant is probably because new additions from the quite heavily populated Liueniua from time to time bring about a regeneration, which does not occur on the other islands because of their isolated positions.

All these islands are populated by Polynesians with a perceptible, though small, admixture of Melanesian blood. Now, all Polynesians have, to a 226great extent, the habit of preserving old traditions, and as it is recognised that almost without exception these have an historical basis, it is of great interest to gather the remnants of these traditions and draw further conclusions from them. In the case of Nuguria and Nukumanu, the latter of which shows great correspondence with Liueniua, a whole number of such traditions is available. For Tauu the material is most inadequate; the population in their steady decline has apparently lost all interest in earlier times, and from several old songs I was able to determine only that the names Sawaii (one of the Samoan Islands) and Tikopia were familiar to them. One of the aitu or godlike revered ancestors is called Lotuma. One of the islands on the reef bears the same name, a name that is without doubt identical to that of the island of Rotuma. The name Tauu also reflects Samoa. We could therefore assume that the present remainder of the population is a remnant of an immigrant tribe from Polynesia, probably from Samoa, which used the islands of Rotuma and Tikopia as intermediate stages. While we have quite extensive information from the other islands about religion, the names of the gods and their functions, the numerous spirits that inhabit reef, sea and air, Tauu lets us down. The current high priest, a Nukumanu native shipwrecked here, is not totally reliable about the old, original beliefs; in his accounts I have often been able to observe that he has not been able to free himself from the impressions of his youth. Nevertheless, I was able to monitor his information sufficiently from the stories from Nukumanu and Liueniua. However, to him too the old legends about immigration and origin have remained unknown, or if he has heard them they have long since disappeared from his memory.

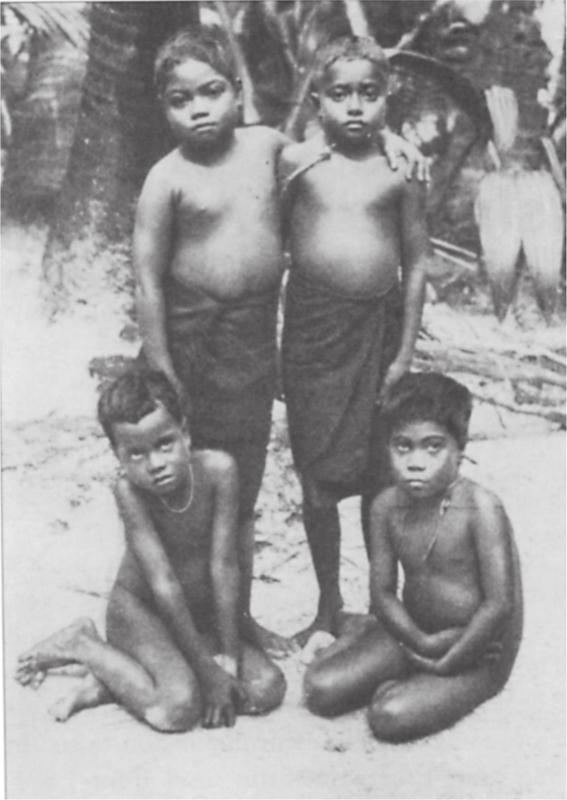

Fig. 83 Girls of Nukumanu (Tasman Islands)

Before I go further, I want to give a brief account of the legends of the various islands.

On Nuguria I was told:

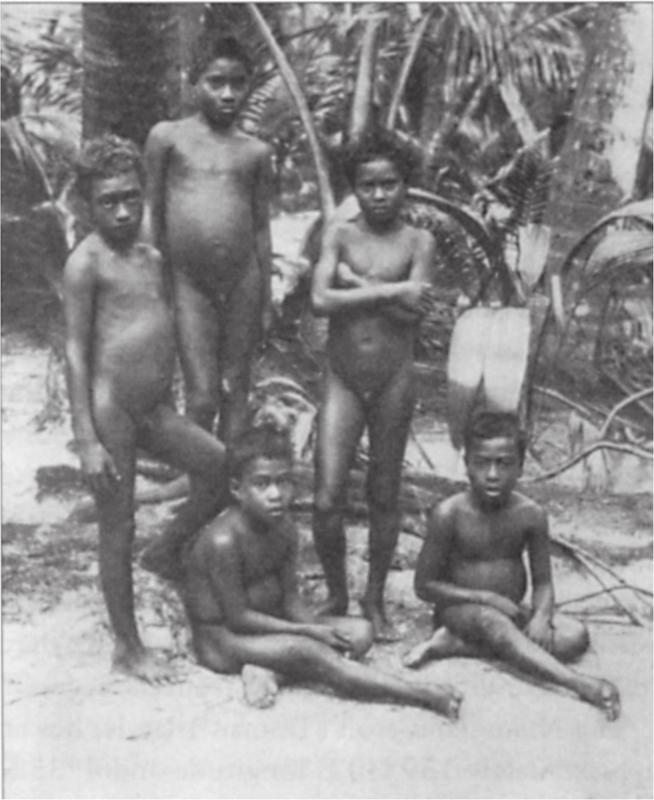

Fig. 84 Boys of Nukumanu (Tasman Islands)

In the beginning two gods came over the ocean in a canoe with three women. They came from Nukuoro and Taraua. The names of the gods were Katiariki and Haraparapa; the three women were called Lopi, Tefuai and Tupulelei. When the canoe reached the reef, Katiariki struck the water with his staff and from the deep arose a bubble that burst on reaching the surface and from it sprang a third god, named Loatu. At the same time a sandbank rose above the ocean surface, beneath the feet of the three gods. Katiariki and Haraparapa were great friends and took Loatu into their band as well. However, when they observed that the island was desolate and undeveloped, Katiariki and Haraparapa decided to make a journey to seek food; Loatu was delegated to guard the island. During the absence of the former two gods, another god appeared, named Tepu. He came from Nukumanu, drove out Loatu and took possession of the island. Meanwhile Katiariki and Haraparapa returned with food, and when they saw that Tepu had taken their possession they were incensed, and in their anger they threw away the food that they had brought with them. This is why a certain edible sea snail and the yam plant occur only on the Malum group and not on the Nuguria group. Katiariki and Haraparapa summoned the evicted Loatu and all settled on Nuguria. Tepu lived on the small hill Mauga (mountain) and right to the present day this is hallowed ground and soil, dedicated exclusively to the gods and their worship. Katiariki and Haraparapa settled to the right and Loatu to the left of the hill, Mauga, and today they are all still regarded as higher beings.

Dr Thilenius quotes the following accounts given to him, according to which eight different immigrations are named: 227

- Katiariki, Haraparapa and Haurua from Nukuoro (450 nautical miles northward);

- Loatu from Sikaiana (590 nautical miles south-eastwards);

- Tepu, Apua, Akati from Tarawa (1,110 nautical miles eastwards);

- Nuguria, Mahuike from Sikaiana;

- Arapi, Tupulelei (female), Tefuai (female) from Tarawa;

- Ranatau, Lopi (female) from Nukufetau (1,440 nautical miles eastwards);

- Hooti, Aitu, Arei, Atipu from Nukumanu (300 nautical miles south-eastwards).

Finally, at the time of Tepu, Pakewa arrived from the high seas in the form of a fish.

No traditions are known to us from Tauu; however, in the holy house there an aitu is revered, bearing the name Loatu, a higher being that we also encounter on Nuguria, and on Nukumanu and Liueniua as well. Today in the hare aiku the following ancestors are venerated:

Loatu (from Sawaii?), Teporo and Lutuma, as well as the women Pukena, Tetuai and Hinepua.

In order to understand the legends from Nukumanu, we need to mention those from the neighbouring Ongtong Java. It was recounted to me in Liueniua:

Lolo lived on the sea floor and built up the coral reefs. When these had not yet climbed above the surface of the sea, a canoe came from afar with Siva in it. He saw Lolo’s head rising out of the sand and gripped it by the hair which was being moved to and fro by the waves, and pulled. Lolo called to him to pull very hard, and Siva succeeded in pulling him right out into the open. Lolo, however, indicated to Siva to go away again, for his island was not yet ready, and also it was for his own use and not for outsiders; upon which Siva went further on. Lolo now built busily and made the reef so high above the water that waves were unable to wash over it. He then began to cover the rock with grass and plants, then with bushes and undergrowth, and finally with large trees.

During this period another canoe arrived, with four people, three men and a woman. Lolo, with whom two comrades, Keui and Puapua, had previously been associated, did not want the strangers to land, and ordered them to remain on the beach with their canoe. But the new arrivals begged and pleaded, and promised Lolo that they would teach him many new things that would offer great advantages to him and his island, so that finally Lolo relented, and gave them permission to set foot on his island. The men who had come in the canoe were called Ame le lago, Sapu and Kau, the woman was called Keruahine. Their homeland was Makarama.

The new arrivals kept their promise. Kau taught how to make fire by rubbing two sticks together, which was previously unknown; he also showed how to prepare food with the aid of fire, which was not previously known either. Sapu brought coconuts out of the canoe, and planted them on the island, thus laying the ground for the present stands of coconut palms. Ame le lago had brought taro plants, and with Keruahine he established the first taro crops. Keruahine introduced tattooing; Lolo stretched out on a mat and was tattooed by her with the still-used patterns. Tattooing was thus universal, and to the present day it is a women’s task. Ame le lago also showed the people how to make mats on a weaving loom for clothing men and women, and consequently weaving is still done by men; only the highest chief and his relatives do not practise weaving.

After a while Lolo chose Keruahine as his wife, but in so doing incensed both his comrades, Keui and Puapua, who also had their eyes on Keruahine, and Puapua was so angry that he left the island group completely and settled on the neighbouring Kikumanu (Nukumanu, Tasman Islands), where today he is still venerated in the hare aiku. (On Nukumanu he is called Pau-Pau.) Keui remained on the island but moved to the uninhabited part on the far side of the Keave burial site, where he built a house on the site of Kelahu.

In Keruahine’s time Kapu lau lagi came from Nuguria in a canoe. Only after prolonged negotiations was he permitted to land, on condition that he remained living alone.

Lolo and Keruahine’s children were Poho uru moro, a daughter who died while a child (ulu mole mole is called ‘bald head’ in Samoan), and a son, Kemagia.

Dr Thilenius’s accounts begin first with Loatu, who, according to the accounts given to me, immigrated much later. According to Thilenius, Loatu and Laurumore and the woman Niua came in a boat from far across the high seas. They settled on Liueniua, but after some time had passed Loatu became jealous of Laurumore and caused the latter’s hair to fall out. He was thus harmless to women and actually had no offspring. All chiefs originated from Loatu. The people stemmed from Uila, who came from heaven with five wives.

The north-western end of the Ongtong Java group is named Pelau after the main island. The Pelau people, significantly smaller in number, and under an individual headman, maintain a certain independence from the headman on Liueniua. They likewise venerate their legendary ancestors as aitu. Tradition there has it that Kepu was the creator of the island of Pelau and its first inhabitant. Later, Apio, Loaku, and Waikahi arrived, and the women Ogäi, Kehä and Keania. These are still venerated as aitu today and have their own hare aiku.

The significance of these traditions is without doubt that immigrants from the earliest times enjoyed divine veneration by their successors, but that 228they were men of flesh and blood who, for whatever reason, landed on the tiny islands, whether on journeys to unknown regions, or because they were driven from their homeland by wind and wave, and after long meandering finally found haven. The traditions from time to time give the original homeland precisely; for example, Samoa, the Ellice group, Rotuma, Sikaiana, Tikopia, the Kingsmill Islands, and several islands of the Carolines. Thus we are justified in concluding that the population of all these islands has arisen from an intermingling of the most varied Polynesian tribes. We are still more justified in such a conclusion because even today, from time to time new arrivals appear on the islands, having been driven from their homelands by unfavourable weather conditions. In the previously mentioned works of the author, as in those by Dr Thilenius, there are numerous examples of such journeys.

Furthermore the great similarity of language and the general appearance of the islanders support their belonging to the Polynesians. Again, the specific racial features of the Polynesians, the characteristic blue-grey spot as large as a hand, that is seen on the upper margin of the buttocks (called ila in Samoa) of all pure Polynesian infants until about five months old, is found here in most cases. I say in most cases because children are also born without this feature. The absence of the ila reveals intermingling with another race. Offspring of Samoan women and white men do not have this feature, and it is also missing in cross-breeding between Polynesians and Melanesians, even when the latter, as, for example, in the New Hebrides or in the southern Solomon Islands, have a high content of Polynesian blood. On Liueniua there are very few exceptions. On Pelau and Nukumanu they are already somewhat more frequent. On Tauu I was able to observe only a single infant, and in this one the blue mark was clearly visible. On Nuguria island in an observation in 1888, there were two out of six infants, in 1893 three out of four, and in 1900 not one out of four without the mark. Absence of the mark, which moreover does not occur without exception in either Samoa or Tonga, seems to indicate that an intermingling with another, impure Polynesian group has occurred. In Samoa and Tonga this is explainable by mixing with the Viti islanders, partly also with Europeans and members of other races. In Nukumanu, Tauu and Nuguria and on Ongtong Java we must similarly explain the lack of the spot by interracial breeding, and indeed we can, with justification, draw a conclusion on the greater or lesser purity of the race from the regularity or irregularity of occurrence of this mark. Thus the population on Liueniua is the most purely preserved, probably because this island was settled by pure Polynesian migrants. On Nukumanu and Nuguria, especially the latter, interbreeding with a foreign race is the most noticeable, and this can be explained if we consider their proximity to the Melanesian island groups of the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands. Liueniua, by virtue of its larger population, was able to resist Melanesian immigration. The smaller groups were less fortunately placed. Thus on all of them we hear of immigration by Melanesians who sometimes moved on again after a long time, or sometimes settled there. The Carteret Islands have only in relatively recent times been settled by Buka people, and the latter encountered a pale people, whom they completely wiped out, and the sole trace of them is in the form of Tridacna axe blades found in the ground.

If we look more closely at the islanders, we become convinced that their outward appearance matches the Polynesians. The men are of medium build, although on Nukumanu and especially on Tauu tall men are quite common. On my first visit to Tauu I was quite astonished at the extraordinary height of the old men who received me at that time. On Nuguria a shorter type lives, probably because the principal immigration from the north came from the Caroline Islands, and the Caroline people, in spite of their close relationship with the central Polynesians, did not attain their height.

The skin shade may be regarded as pale brown. Darker and paler shades occur here as in Samoa, partly as a result of occupation, because some natives are more at the mercy of the sun’s rays than others. Fishermen and outdoor workers are therefore darker than, for example, the headman who for the most part remains in his hut, and the women, who do not come out into the open often either.

Sometimes the hair is completely straight, sometimes in ringlets or wavy. On Nuguria I have seen hair that one would call almost frizzy, even though the characteristic small curls in the shape of a closely wound corkscrew, so characteristic of Melanesians, do not appear. Beards on the whole are sparse, although quite heavy beards are seen on Liueniua and on Tauu; I do not remember ever having seen a single heavy full beard on Nukumanu, nor on Nuguria.

In older age the women especially are uncommonly fat and portly, and, in this regard, what I had occasion to observe during my first visit to Tauu exceeded everything that I had seen, for example, in Samoa and Tonga. Several of the old Tauu women at that time were so stout that they were not able to move round, and had not only to be carefully carried from place to place by their less stout compatriots but also fed as well. In this regard Nuguria takes second place to the other islands probably because of the poor health of the population; however, well-nourished and stout women are of the greatest beauty in the eyes of the islanders. 229

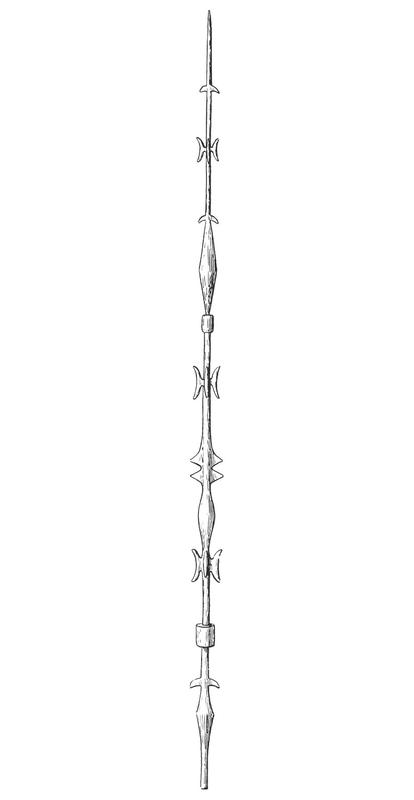

Fig. 85 Ancestral image of Pau-Pau. Nukumanu

I have already mentioned that the languages of these islands show a great similarity, and moreover are very closely related to the central Polynesian languages. Samoan is immediately and without great difficulty understood on the islands; however, closer investigation elicits the fact that many words originate from the north, particularly from the Carolines, proving once more that immigration occurred from there as well. Particularly on Nuguria immigration from the north, from all those islands that we recognise under the group name Micronesia, seems to be strongly represented.

Religious ideas are basically the same everywhere.

Although the central Polynesian element is predominant, we find, however, only slight traces of the knowledge of a supreme god, which we certainly find elsewhere in Polynesia. The Polynesian gods Tagaloa and Maui seem to have passed into total oblivion. On Nukumanu they know higher spirits that live in Ba e lagi. Ba e lagi is an indefinite concept; it signifies both the residence of the spirit and the spirit itself. Ba e lagi has two children, namely Koko e lagi and Keagiva (the Milky Way). Koko e lagi is the guardian of the place Ba e lagi which the souls of the dead strive to reach, without sufficient protection from Keruahine, driven back under thunder and lightning onto the reef Muli a au. Keagiva sends the rainbow (umaka) and, if he is angry, the hurricane (sisio). The makua (see page 230) have the privilege of calling upon Keagiva, who then sends shooting stars (kagaloa) to cause disaster. Kagaloa is undoubtedly identical with the central Polynesian Tagaloa, but has gradually sunk from the idea of a supreme being into a subordinate position.

Spirits also dwell in the moon; the moon spirit, Makaga is clearly seen sitting in the moon twisting cords of coconut fibre.

Magu (on Nuguria te taro) lives in the evening star and makes wind and bad weather; Kauha (on Nuguria Atea) has his position in the morning star and makes the sunshine and good weather.

On Tauu they also know a dwelling place above the stars, where a higher spirit lives. His name is Taroa, which could be a distortion of the name Tagaloa.

On Nuguria they know a higher being, named i Luna te lagi, to whom all the living and lifeless are subject, also the ancestral godheads.

They do not make images of any of these higher beings for public veneration.

The whole religious cult is based on veneration of those first colonists, which are all revered as aitu or aiku. The cult of these ancestral gods is totally to the fore. Special dwellings, hare aiku, are erected for them, and many are built in all kinds of shapes.

On Nukumanu we find the god Pau-Pau (Pua-Pua from Liueniua) (fig. 85.) It is a roughly carved wooden figure about 5 metres tall and almost an exact replica of the images of Lolo and Keruahine 230set up in the hare aiku on Liueniua.

In their shape, the faces of these ancestral images strongly recall the large wooden masks from the Lukunor group (Museum Godeffroy, plate 29, fig. 1), which are called topánu there.

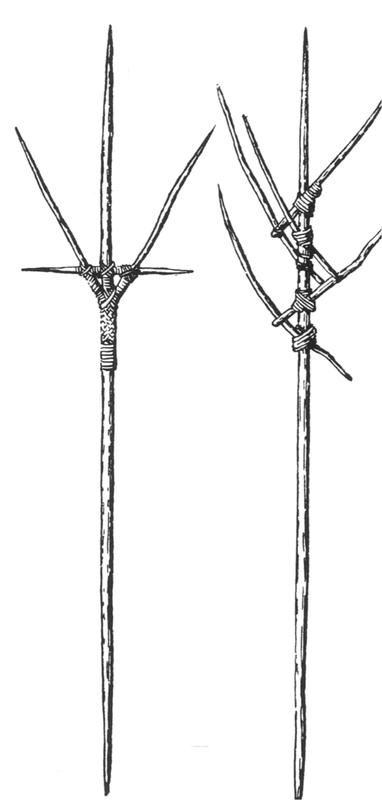

On Tauu the ancestors Loatu, Teporo and Hinepua are venerated in a hare aiku. The ancestral image of Loatu was a carved spear, of which the lower part of the shaft was broken off and set into a new piece of wood. The spear (fig. 86) could quite probably have been the personal property of the immigrant Loatu. I succeeded in acquiring this old item, and since that time a simple stick has been set up as a memorial to Loatu. Teporo’s memorial is a black piece of wood about 4 metres long and about 15 centimetres in diameter at the thickest end, painted red at one end; it appears to be a washedup fragment of a ship’s spar. Hinepua’s memorial is a simple rough wooden block without carving.

Fig. 86 Memorial of Loatu, Tauu

On Nuguria the memorial to Tepu consists of a rock. The hut erected over it was burned down a few years ago at the time of a punitive expedition, and as far as I know has not been replaced. Tepu’s memorial by its nature avoided destruction; but according to comments by the natives there were other wooden memorials which were destroyed by the fire.

Over the years the ancestors have taken on godlike functions, and are venerated and called upon on all occasions. As intermediaries between the aitu and the people, a special class of priests or sorcerers developed over time, and enjoys a special reputation. Some of these priests provide the service of a particular aitu; others combine in themselves the ability to conjure up all aitu. Some are created temporarily, others remain priests their whole life. In the latter the occupation is passed as a rule from father to son. A special jewel of these priests is two large ornaments of turtle shell that hang from the nostrils. A fan and a folded mat also belong among their attributes.

The sorcerers or priests also fulfill the role of healers and doctors. They do not seem to know real medications; all illnesses are banished by murmuring special spells, rubbing with oil, sprinkling with salt water, wrapping with special sacred mats, waving certain green twigs to and fro, and fanning with the priest’s fan. The evil spirits that cause all illnesses must then yield to the sorcerer; otherwise the illness is brought about by the anger of some aitu or other, and it must then be appeased by sacrifice and supplication until it changes its mind, whereupon recovery results; in the opposite situation death ensues.

As well as the ancestral gods, there is a large series of spirits which we can designate as spirits of nature, bearing the name tipoa (Nuguria), or kipua (Nukumanu). They inhabit the coral reef, the sea, the air, odd trees or certain rocky outcrops. They tease humans, cause illness and injury, and can be appeased by the mediation of certain priests or sorcerers. Their number is very great, and the designation of individual ones varies from island to island. Some of them have the property of becoming visible to the islanders at night; this always results in an illness or misfortune. Widely varying forms of sacrifice are brought to the tipoa or kipua just as to the aitu or aiku, to keep them on favourable terms.

The islanders split into several classes, which are the same everywhere. The chiefs and their male relatives form the highest class. On Liueniua and Nukumanu this class is called tu’u; but on Tauu, on the other hand, it is tui. (This is a still current Samoan word that is used for the highest chief or king, as, for example, Tui Aana, the highest chief of Aana, Tui Atua, the highest chief of Atua, and so on.) Following this class, in order, is the class of the makua or matua (in Samoa, matua = parents, the elders), with whom the priests rank equal. Then on the lowest rank follow the common people. The tu’u are the successors of the legendary ancestors; after death their souls remain on the island, sometimes in special houses, in the neighbourhood of the aitu, their ancestors. The souls of the makua or matua go after death to the legendary home that lies beyond the stars, when they have the necessary escort of the aiku. After death, the souls of the common folk go as a rule to a certain place on the coral reef.

The members of the highest class never marry women of their own class, but always from the lowest class. The women of this class must therefore always marry men of lower class. If, after marriage, men of a lower class had illicit intercourse with upper-class women, this would be punished by death in earlier times. It is possible that this custom still exists but is kept secret from fear of the whites. Women of an upper class, who, while not being married, have illegal intercourse with men from a lower class, were punished by female relatives biting off their noses and ears. I have seen such a mutilated person on Nukumanu and another on Liueniua.

Incidentally, before marriage the young women of all classes are quite unfettered in their way of life, but wisely remain within the confines of their own class.

The wives of deceased members of the highest class can never remarry. Widows or divorcees of the other two classes can seek a new husband.

Special marriage customs do not exist. The men of the upper class simply send their retinue to the house of the girl whom they desire and she calmly follows them. In the other two classes it is essential that the suitor brings the father of the girl a gift of mats, turtle shell and turmeric. Acceptance of this gift is tantamount to acceptance of the proposal, and without further ado the girl follows the suitor 231to his hut. Divorces occur, but not often, and are mostly the result of scenes of jealousy. Suicide by the wife also occurs for the same reason; it is more rare in the husbands.

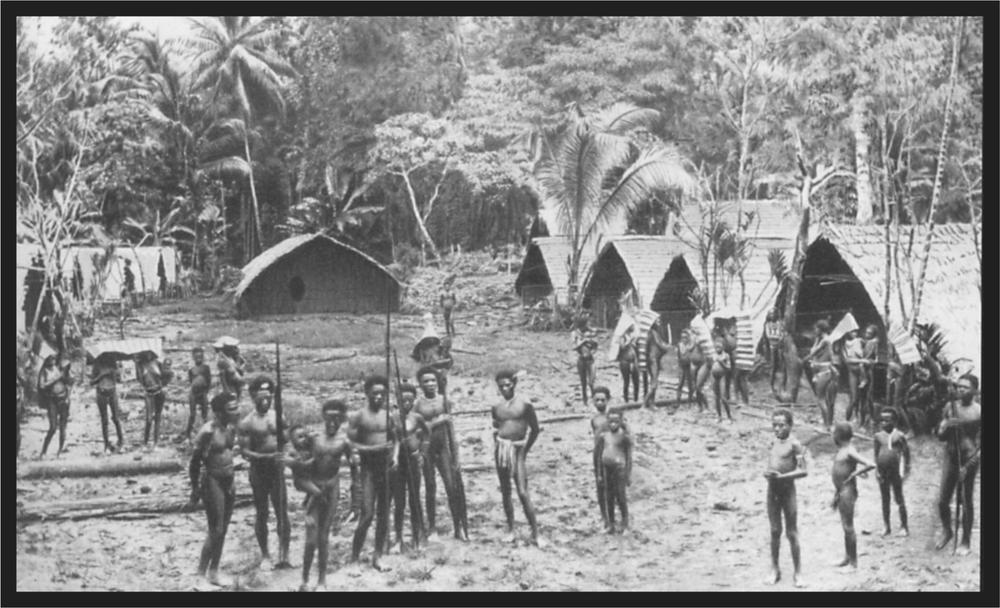

Plate 34 Village scene on Nissan

Birth celebrations and customs are likewise not of great significance. A type of feast is put on for the pregnant woman in the fifth month. The relatives bring food and a public meal is prepared; the sorcerer pronounces his charm over the pregnant woman. As a rule the child’s grandmother performs the midwife duties. If the pregnant woman is married to a native of either of the upper classes the birth takes place in the house of the family head of this class. The women of the lowest class give birth in their husband’s house.

The newborn baby is cared for by the grandmother; she shapes the infant’s head by gentle pressure and then bathes it in the sea. Then the child is wrapped in mats, and for the following two days the grandmother (kepuga) holds it by the fire so that it is kept quite warm. Then it is handed over into the mother’s care. After about four weeks the relatives bring coconuts and food and there is feasting again.

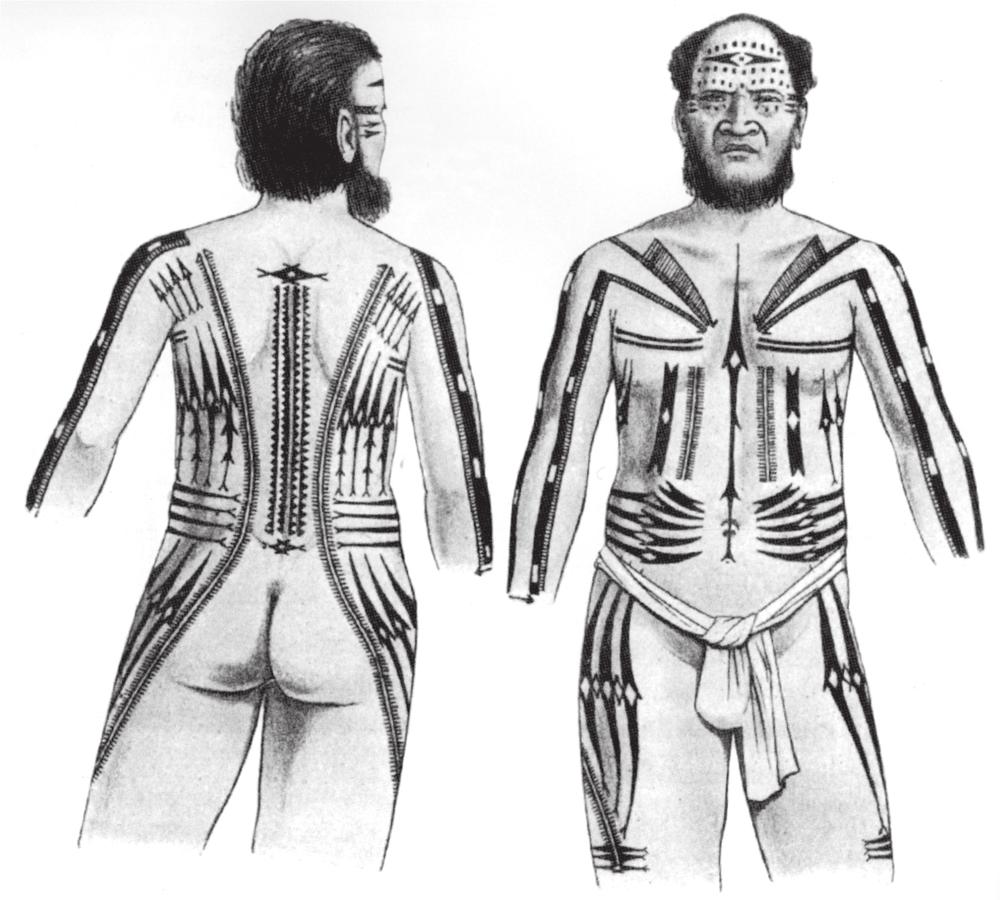

When the young boys are about ten to twelve years old the septum and wings of the nostrils are bored through, and clothing mats are donned. The ear lobes of girls of the same age are bored through, and at the same time they are dressed in clothing mats and tattooing is gradually carried out, from waist to knees. When this is complete the girls are ready for marriage. Boys are tattooed only after marriage. On Nuguria and Tauu, where tattooing is not customary, dressing in mats is regarded as a sign of readiness.

Funeral customs vary according to the class of the deceased. A dead person from the highest class is wrapped in mats and laid out on mats in the hut. A general wail of mourning begins, and continues uninterrupted for two days and nights. Then the corpse is buried in the burial ground set aside for the highest class, and the wailing continues for several more days, this time in the house where, in the people’s opinion, the souls of the members of this class remain. At the same time a great feast is prepared. The priests of the aitu have nothing to do here because the spirits of the dead return directly to their ancestors, the aitu, and need no intermediaries.

If a makua or someone of equal rank dies, the corpse is laid out on a scaffold about 2.5 metres tall and rubbed copiously with oil and turmeric; the relatives then cover the corpse with woven mats. The priest then approaches, beseeches the aitu, and ignites dry flower cases of the coconut palm, which he lays under the scaffold. For each individual case he names an ancestor of the deceased. Every male makua approaches the corpse and has to recite the responses to a particular song that those round about begin to sing. Two days later, the corpse is brought to the hare aiku, where the aitu are implored to guide the soul of the deceased to the home above the stars. Then the corpse is fastened to a wooden frame, wrapped in mats, and interred at the burial site of the makua. A coral block is erected 232at the head of the grave, anointed with oil and wrapped round with consecrated Pandanus leaves. The widows of the makua cover their heads with plaited coconut palm leaves and wander around, lost, on the beach or in the forest for days. Those chancing upon them hide at their approach.

Fig. 87 Tattooing on Nukumanu. (Man, posterior and anterior aspects)

The lowest classes, after a short wail of grief by the relatives, are buried without further ceremonial. The same applies for all dead women.

Annually, around March, there is a general feast in honour of the aitu, which continues for four to six weeks depending on the availability of a greater or lesser food supply. At these festivities the clothing of boys and girls in mats takes place; the images of the ancestors are carried into the open, crowned, and adorned with mats. Children and adults form a procession with loud singing in honour of the ancestors, and the young folk in particular lead an unfettered and unrestrained life.

Tattooing (tatau) of the body is common, especially on Nukumanu. The predominant design matches the Liueniua pattern completely. Both men and women are tattooed, and the procedure for the latter especially is very comprehensive and time-consuming, for almost the entire body is covered with tattooed designs. Dr Thilenius has explained clearly the significance of the individual designs, which represent stylised fish, sea creatures, caterpillars, birds and birds’ beaks, nets and replicas of occasionally washed-up decorated parts of canoes, and in no way come from any religious motives. The same tattooing had been fleetingly introduced into Nuguria, but had again passed into oblivion. On Tauu I certainly observed the same tattooing, but it transpired that the wearers of the tattoo had been shipwrecked from Nuguria and Liueniua. The Tauu people tell me that a long time ago tattooing was also customary on their island, and followed a completely different design.

Markings of a Samoan design brought contradictory comments, but I was able to conclude that they were similar, for they were all in agreement that the ancestors, not like on Nukumanu, covered the face, the arms and the chest with designs. The tattooing instruments were also known on Tauu, and I succeeded in acquiring several very old specimens.

The tattooing instruments are little wooden sticks about 15 centimetres long, into one end of which are stuck 2-centimetre-long fine-toothed blades of bone scraped thin, at right angles to the handle.

These blades are 2 to 6 millimetres wide. To use it, the instrument is held firmly in the left hand and, by gentle blows with a little baton held in the right hand, the fine points are driven through the outer 233surface of the skin, after the instrument has been moistened with black dye. Tattooing is exclusively a task of the women, who are recompensed with mats, turmeric, and so on.

Fig. 88 Tattooing on Nukumanu. (Woman, posterior and anterior aspects)

The name of the tattooing instrument with which the design, tatau, is made, is matau on Nukumanu and Liueniua; on Tauu the instrument is designated as taau; in Samoa it is called le au, and on Nukuoro te au. The similarity is so striking that a conclusion can well be drawn on the homogeneity of the islanders.

In earlier times the natives were not so peaceable as they are today. One can quite justifiably blame them by and large for falsehood and cunning, even though today out of fear of punishment they suppress these characteristics more than previously. On Tauu in the middle of the previous century, the entire crew of a whaling ship was slain and the vessel destroyed. In the 1880s and 1890s, the Nuguria people killed peaceful traders and concealed the fact for a long time by a show of apparent friendship. Surprise attacks and slayings of ships’ crews have taken place on Liueniua too. Even today they are not so particular about the truth, and the concept of yours and mine is not strongly developed. On the whole they are not very industrious and work only as much as is necessary to stay alive. Only the headmen accumulate property, at the expense of their subjects. In general one has to designate the islanders very much as having no wants. With fish and coconuts and the very small and poor-quality species of Arum that grow on the island, they satisfy their needs year in and year out. Recently the whites have introduced rice, 234which has very rapidly earned the general favour of the people.

The headmen rule their people fairly autocratically. On Tauu the headman’s family has totally died out. On Nuguria and Nukumanu the ruling chiefs can produce a long family tree of their ancestors, extending as far back as the fabled first settlers, or aitu. The headman’s office is inherited; however, the post passes first to the brother of the dead headman, if one is available, and only second to the son.

Although supremacy in all things belongs to the chief, he is not the sole possessor of land and soil. Of course, a certain not inconsiderable portion of this belongs in his possession, but by far the largest portion belongs to the matua class who have parcelled out the land among themselves. By gift or purchase, land and soil and all growing on it passes into the ownership of another matua. The third class of people have no ownership of land; they attach themselves to members of both upper classes, perform all types of service and form the following of the person in question, who thereby gives them a portion of his coconuts and other fruits, and allows them to fish on the reef and in the lagoon.

On the whole, the women lead quite a comfortable life and work outside only occasionally. The headman’s wives lead a distinctly lazy life, lie on mats most of the time, allowing themselves to be pampered and waited on. They are always rubbed copiously with oil and turmeric, and spend much time on this toileting. They go only seldom into the open air, in order not to be burned by the sun, for a pale skin colour, which allows the tattoo design to appear sharply and strongly, is regarded as a particular beauty. If they travel from one island to another, a special shelter from the sun’s rays is built for them in the canoe. At home they have a lot to say, and the husbands, right up to the highest chief, fear their malicious tongue which now and again leads to marital disputes where the husband exercises his authority with the stick. If a wife pushes the quarrel too strongly, this is sufficient grounds for divorce.

Wars do not occur among the small groups, although on the other hand there are disputes now and again, in which the individual families take part. These disputes can degenerate into brawls in which the women also take part. A few years ago on Nukumanu the then chief received a fatal stab wound on such an occasion.

Fishing forms the main occupation of the islanders. To a far lesser degree they take up farming, if it can be called that.

Everything that lives in the sea or on the reef is hunted; the islanders do not easily let go of anything edible. Single- and multi-pronged spears are common everywhere, and are used on the reef and in shallow water in the lagoon. Besides this they use smaller draw-nets, throw-nets and longer sinking nets, the latter being the common property of the whole population or of individual families. Small, cunningly constructed nets, fastened on cords between two cross-bound sticks, are set up in such a way that in diving the fish pulls the net over itself. These are used here as on the island of Apolima in Samoa. They fish also with hooks, some of which resemble those of central Polynesia, while others resemble hooks from the Micronesian islands. The material is mother-of-pearl, turtle shell and pieces of Trochus shell as well as a certain species of Pinna. The most interesting is a large hook made of wood, generally known as a shark-hook, although not used to capture this marauding creature but for catching a species of Ruvettus that is found outside the reef. This Ruvettus is spread far across the South Seas; it is caught here with exactly the same hooks as on the Gilbert and Ellice islands where the fish is called ika na peke. In several of the Carolines the fish and the hooks are not unfamiliar, and on Liueniua and Nukumanu we find the hooks in general use. On Tauu I found the hooks but the catching is no longer carried out; on Nuguria the hooks are likewise present, but Ruvettus fishing is dying out. The Ruvettus lives in deep water outside the reef and never comes into the lagoon. They fish for it only on dark nights and must go out on the high seas in their canoes for this purpose. These Ruvettus fishing expeditions are often the reason why canoes and their crews lose the island from sight in sudden squalls, and are shipwrecked in other regions. The Ruvettus hook or auu is made of hardwood, the longer shank is 20 to 30 centimetres long, the shorter 15 to 25 centimetres. At the upper end of the short shank the hook is fastened by coconut fibre cords at an angle of 45˚ to 50˚ in such a way that the tip of the longer shank is only 1 centimetre away. The long shank has a projection at the end for better fastening of the cord. This consists of a number of thin cords wrapped round with another, similar, one so that they form a fat rope 7 to 10 centimetres long which hangs from a 45- to 55-centimetre-long bar. From the end of the stick rises an open loop. Use of this hook is depicted in figure 89: a. is the line with which the hook is sunk; b. is a heavy coral block which pulls the end of the bar under water, so that the end of the stick is horizontal in the water and the attached hook swims freely.

Ruvettus fishing is a very popular sport since it requires not only the utmost skill in sailing and steering but also includes many dangers. It is a sign of maturity when the boy is permitted to join these night-time fishing expeditions.

The fish itself is an universal favourite food and a real delicacy, although the pleasure has strongly purgative effects, which is why in other places it is called ika na peke, the purging fish. On the small islands mentioned here it is known by the 235name lavenga.

The raw material for nets and ropes is supplied by the coconut palm in the form of coconut fibres, and a species of hibiscus with fibres that give a strong, long-lasting twine when twisted together. The coconut fibre cords are not twisted but plaited.

When fishing on the reef the people protect the soles of the feet, and more particularly the balls of the feet, by wearing firm sandals, kaa, plaited from coconut fibre.

Fig. 89 Ruvettus hook from Nukumanu

One cannot talk of farming on a small coral island. Everywhere the coconut palms grow luxuriantly and require no special care; the smaller islands are almost exclusively occupied by this useful tree. The larger islands are forested in the interior; among the trees are the type of breadfruit with the big kernel, and on the seaward side of the islands a circlet of Pandanus trees, the fruits of which are enjoyed by the islanders as a source of nourishment. In the middle of the islands, protected against onshore winds by a dense stand of trees, the people conduct small-scale agriculture, which is characteristic of these islands. The islanders have dug flat pits out of the upper surface of the coral reef for probably hundreds of years. These are up to 2 metres deep and 100 to 500 square metres in area. In the bottom of the pit over the course of time they have built up a scanty layer of humus by throwing in all kinds of plant material, and here they grow a small species of taro and a considerably robust species of Alocasia, the latter cultivated in preference since the yield is more abundant and the cultivation less difficult. Bananas have been introduced only in recent times, but are still regarded as a luxury item.

The canoes of the islanders are hollowed-out tree trunks with an outrigger. Driftwood is frequently, I would almost say usually, used since the trees growing on the island yield a wood too hard and difficult for this purpose. They are very skilled at improving damaged sections of the trunks floating ashore by inlaying pieces of wood.

Years ago, on my first visit to Tauu, I saw big canoes lying in separate huts on the beach. Even at that time they could no longer be used by the diminished population because they were too heavy to be launched into the water, even with the combined strength of all the men. These canoes were up to 14 metres long and 1.5 metres deep, and were built from the keel upwards from planks laid side by side. Both fore and aft they had long steeply rising end pieces, carefully carved, and also at both ends a canopy which depicted roughly carved relief figures. Unfortunately, on this first visit I did not have enough time to take a photograph, but I was able to throw together rapidly the following drawing of one of the end pieces (fig. 90). When I paid a visit to Tauu several years later wind and weather had destroyed the canoes to such an extent that only small fragments remained. The natives said to me that earlier, people had sailed in these vessels far out to sea to catch lavenga (Ruvettus), and that large triangular mat sails were used. The drawing shows an oval plate at the upper end, hollowed out a little, like a dish; this served as a seat according to the headman.

Fig. 90 Canoe prow from Tauu

In our small island groups the population lives on the main island of the atoll; the smaller islands are inhabited only temporarily during fishing expeditions or coconut harvesting; it may be that the headman exiled this one or that one who had made themselves unpopular in the village, to one of the islands.

The villages are laid out according to a particular system; wider streets run between the huts, and where the population is still numerous, as, for example, on Nukumanu, they take care that the streets are always swept clean and strewn with sand. On Nuguria, and especially on Tauu, this is not the case, because of the reduced population, and the latter island shows a sad decline.

The huts are constructed universally according to the same plan, about 6 to 8 metres long and 3 to 4 metres wide. The side walls are 1.5 to 2 metres tall; the roof rests on two to three posts about 6 metres tall, and projects about 1.5 metres beyond the vertical walls at the gable ends. Roof and side walls are, as a rule, covered with woven coconut palm leaves. The longer-lasting Pandanus are also used as roof cladding. The floor is pounded earth covered with coral sand. A shallow circular pit serves as a hearth. Implements hang on the side walls; on one end wall an open cupboard is often attached, mainly for storing coconuts. For sleeping or sitting down, they spread out woven Pandanus mats on the floor. The dwelling house, hare or hale, is far less carefully constructed than the houses of the ancestors, the hare aiku or hale aiku (or aitu). These are 236considerably larger, and the roof construction in particular is carried out with much care. The floor of the ancestor house or temple is always covered with coconut mats and is only walked upon by the priests, the other people sit along the walls.

The open space by the hare aiku is called marae (Samoan: malae); around which are the open huts that are regarded as dwellings of the spirits of the dead chiefs. Not far from the hare aitu is the sorcerer’s dwelling, likewise a more carefully constructed house than the ordinary dwellings.

Every village has several wells; that is, deep holes dug into the coral base, where water gathers, especially when it rains. At the time of prolonged drought the water available, for the most part sea water seepage, is very brackish and undrinkable to Europeans; the natives, however, seem to relish it.

Above all, it is characteristic of these islanders that they are also able to quench their thirst with salt water without experiencing any after effects. This is a circumstance that must be considered when we hear of week-long wanderings of those adrift from their island. Europeans would succumb after a few days because of a lack of drinking water.

Not far from the village is a common burial ground. The individual graves are marked by headstones, and are always kept clean and tidy. Very often villagers are seen here, pulling up weeds, sprinkling a grave with fresh white coral sand, or garlanding the upright headstones or sprinkling them with oil.

Since the population of these islands consists of a mixture of many surrounding, mainly Polynesian groups, most of the ethnographic items bear a relationship with items from their homeland.

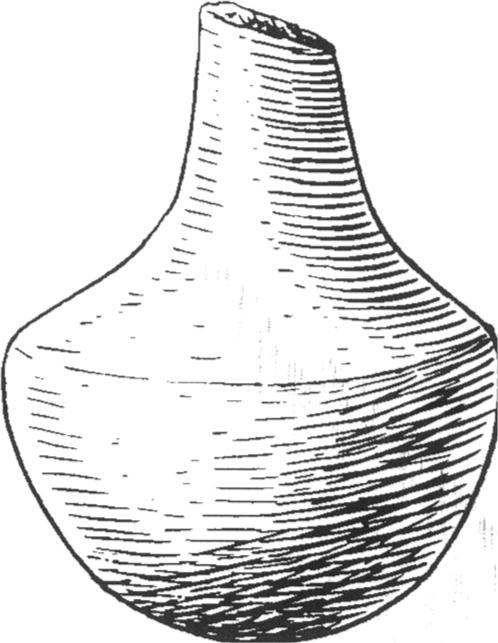

Domestic utensils are sparse. But everywhere we find one-piece carved wooden seats, aluna or nahoa, wooden bowls, kumate, haufa or umette (fig. 91), and coconut bowls plaited round with a network of fibrous cord, for storing oil or drinking water.

Fig. 91 Wooden vessels. Eastern islands

Wooden pounders, kuhi or tuki (fig. 92), of various shapes for pounding different foodstuffs, and coconut scrapers, tutuai, are found in all the huts. Coconut scrapers from Tauu are prepared particularly carefully; on the other islands they consist of a simple board or stick to which a shell scraper is attached. Baskets, both of coconut palms leaves and strips of Pandanus leaves, serve widely varying purposes.

Fig. 92 Pounders. Eastern islands

As well as these household utensils, variously shaped scrapers and knives are found in the huts, some made of turtle shell, some of turtle bones, and also bone needles for sewing mat sails, but year by year they become more rare, and are in places already no longer in use, replaced by European items.

Fig. 93 Multi-pronged spears from Nukumanu

It is even more so with old weapons and implements. On Nuguria the principal weapon was a club about a metre long, made of mangrove wood; we 237find it on the other islands as well. Long smooth spears were also present, but seldom used. On Nukumanu we find spears used that in their multipronged shape resemble the lances of the Gilbert Islands; these occur also on Liueniua from where they were probably introduced (fig. 93).

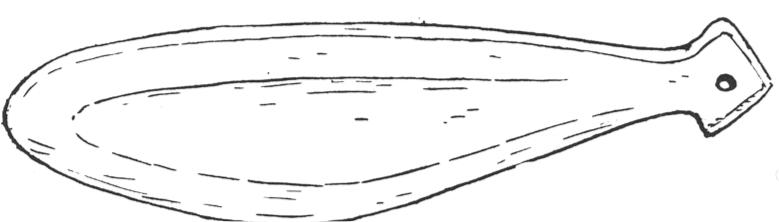

As a close-quarters weapon in hand-to-hand combat they use a club-shaped piece of whalebone, called paramoa on Nukumanu (fig. 94). I have not seen this on Tauu and Nuguria. Axes and other instruments have totally disappeared today. At most they still have the blades. I have a few blades from Tauu and Nuguria (still in the original binding), which I was able to obtain years ago as last remnants. The raw material is mostly Tridacna shell; on Tauu there occurs a blade made from the Terebra snail shell as well. All blades are attached in the same way, namely to a knee-shaped piece of wood by means of firm wrapping with fibre. The Tridacna blades from Tauu stand out through their extraordinary length and their careful manufacture (see the illustration in Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, vol. X, page 144).

Fig. 94 Whalebone club from Nukumanu

I also obtained a very old wooden club from Tauu. The striking end is broad, thicker in the middle, tapering towards both edges; the handgrip carries an incised pommel at the upper end. From the same island I have several quadrangular blades with sharp cutting edges, and with two circular holes at the opposite end; the raw material is turtle bone. Fastening is achieved by fibrous cords; the edge of the blade is inset into the handgrip. The object very much resembles the spatula from Matty, used in food preparation (see fig. 73).

On Nuguria in earlier times a shovel was used, especially for preparing taro beds, and was not found on the other islands. The implement, called kapa, is no longer used (fig. 95).

Fig. 95 Shovel from Nuguria

On Nukumanu a characteristic weapon is still found, called gipugipu. It is a throwing weapon, made from a heavy piece of mangrove wood. Short conical sharp knobs are carved in, towards both ends of the actual body of the weapon which is about twice as big as a fist. When thrown by a powerful arm the instument would be capable of inflicting serious injury.

Ornaments are found only to a slight degree. In ordinary life they are not used as a rule; they appear at festivities, but one cannot say that they are an everyday item. Massaging with oil which is dyed intensively yellow by grated turmeric, is the main decoration. Its use is so extensive at celebrations that the people are literally dripping oil; the women especially seem to prefer such massaging, for it gives the skin a paler shade, a sign of beauty in the eyes of the men. The sorcerers or priests of the ancestors wear a characteristic turtle-shell ornament in both wings of the nose, consisting of two discs which hang down over the mouth. The priests never remove this item of jewellery; the old men wear it only at the annually recurring festivities.

Ear ornaments in the form of rings pushed into one another, and fish-like turtle-shell or marineshell discs are not infrequent; plaited armbands are seen here and there, but all these items are now superseded by introduced glass beads.

An early, very special ornament on Nukumanu, probably introduced from Liueniua, was a series of worked whale teeth. These did not occur on Tauu and Nuguria.

At festivities women wear a wide belt to fasten the mat skirt, moso on Nuguria, moro on Nukumanu. This belt consists of about ten rows of about 65-centimetre-long cords of beads. The individual beads are made out of coconut shells about 5 millimetres in diameter and 1.5 to 3 millimetres thick; the outer rim is polished. The black coconut beads are interrupted at intervals from about 8 to 10 centimetres by one or two small white shell discs. This belt strongly resembles similar items from several of the Carolines. On Tauu this belt consists of two to four adjacent rows of white snail shells, each as large as a small hazel nut; these snail shells are firmly sewn onto a strong binding of plaited fibre.

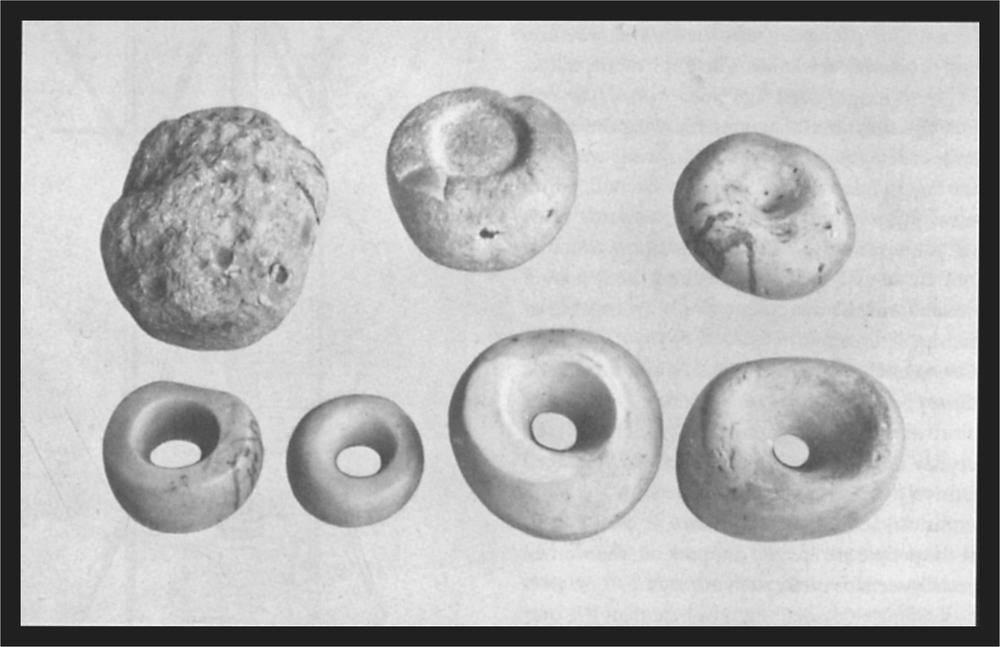

On Nukumanu money cords are still made, called kua, common earlier also on Tauu and Nuguria. They consist of small discs of coconut shell, 7 to 2388 millimetres in diameter, the centre of which is bored out with the drill, fao. These discs are strung onto cords about 1 metre long, and five of these cords comprise a whole item. The manufacture is the women’s task. We find the same cords again on the Gilbert Islands.

Clothing consists of woven mats, made from the fibres of a species of Hibiscus. Besides this, on Nuguria a finer weave is produced from banana fibres. The women’s mat, marau or mehau, is about 175 centimetres long and 80 centimetres wide, and after manufacture it is dyed dark brown with a brown dye and oil. The men’s mat is only about 22 centimetres wide, folded together and wrapped round the waist with one end passing between the legs and fastened behind.

Preparation of these mats forms a characteristic industry, which I will consider somewhat more closely because a weaving apparatus is used, enabling us to draw a conclusion on the origin of the population of these islands.

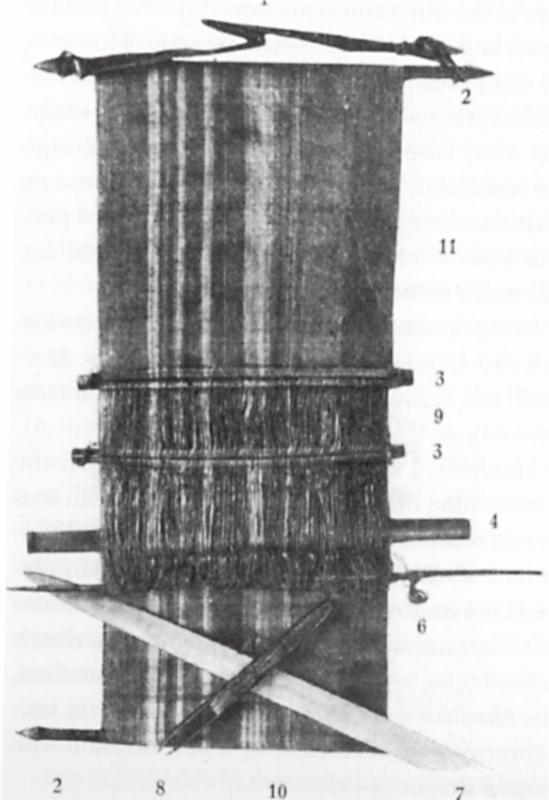

The weaving looms from Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu show no difference from the Liueniua and Sikaiana apparatus of which I hold examples. According to a description that I have, the loom on Tikopia ought to correspond with those from the previously mentioned islands. In his album (page 160), Edge Partington depicts a Santa Cruz weaving loom that is not significantly different. To my knowledge, the island is the southernmost point for finding a weaving loom. North of our islands we come across the apparatus again in the same form on Kapingamarangi or Pikiram. Further north, we find it on almost all of the Carolines, on Nukuor, Lukunor, Kuschaie, Ponape (now totally unused), Ruk, and further remnants on Yap, Sonsol and Mafia. When we see the apparatus that the weaving shepherdess from Milam in the Himalayan region (depicted in K. Boeck, Indische Gletscherfahrten, and reproduced in Lampert’s Völker der Erde, vol. I, page 221) has spread out before her, then one might be tempted to regard it as an implement from Nukumanu that has ended up in the Himalayas, so closely do the individual parts match, and also the manner of using the apparatus. On Celebes Island we find it again, albeit improved upon, and in its main features it revisits not only the African continent and Madagascar, but also America. Ratzel, in his Völkerkunde, volume I, page 668, depicts a loom of the Bakuba (Congo region) as an example that ‘where the older African cultural possession points outside, it points eastwards’, and with regard to the loom he adds: ‘The loom is significantly the same on both sides of the Indian Ocean.’

With regard to America, I refer to a diagram in the Annual Report of Field Columb. Museum, Chicago 1897-98. In plate 18 the typical home of a Hopi Indian family is depicted, and on the wall to the right we see a loom which, although not clearly visible, appears to have the main features of the Polynesian loom.

The old Egyptian pictures of the loom correspond reasonably with the apparatus that is used today on Nuguria and Nukumanu, and on page 248 of E.B. Tylor’s Anthropologie, based on an Aztec picture, a Mexican weaver is depicted holding her apparatus exactly as they do today on the previously mentioned islands, although from the picture it emerges that the Aztecs did not know about the weaver’s shuttle, but pushed the weft-yarn between the lengthwise fibres by means of a little rod.

Plate 35 Shell money (kuamanu) from the island of Nissan. Various stages of preparation

239There can be little doubt that this loom has its homeland in Asia and spread from there to all parts of the world, with the exception of Australia.

Its spread across Oceania extends through the Carolines as far as the island of Kuschaie; we do not find it further eastwards in the Marshall Islands, and there is no evidence that it has ever been there. South of the Marshall group, in the Gilbert Islands, and on the isolated islands of Paanopa and Nauru settled from the Gilberts, it is similarly unknown; and also on the Ellice Islands, Samoa and Tonga.

If we go westward from here we likewise do not find the loom in the Viti group inhabited by Melanesians, nor in New Caledonia, and this does not surprise us because the apparatus is a Malayo-Polynesian device, not a Melanesian one. On Santa Cruz where a strong Malayo-Polynesian immigration has made itself felt, the loom reappears, but we do not find it anywhere in the Solomon group. Thus it may be that the primitive apparatus which we encounter on Bougainville, Buka and Nissan, and which Dr Danneil has described in the Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie, volume 14, and drawn on plate 19, is not an initial stage of weaving, or to some extent a transition between plaiting and weaving as the author believes, but an atrophied form of the loom. In the Bismarck Archipelago and on the western islands south of the equator, the apparatus is also unknown. Recently, from the island of St Matthias north-west of New Ireland, belts and mats have become familiar; these are undoubtedly woven (see pages 143 and 148).

However, we find in places where the loom and woven material existed earlier, that the apparatus is no longer in existence. On Pelau, Kubary maintains that the art of weaving existed in ancient times. On the small islands of Mafia and Sonsol the art has vanished into oblivion, although remains of the apparatus and descriptions of the individual parts are familiar. It is the same on Yap, and on Ponape they still remember that ‘in olden times’ the art of weaving was practised. However, in 1901 I could not find an islander who knew the names of the individual parts.

The fact that the art of weaving has been maintained for a long time on the small islands like Nuguria, Tauu and Nukumanu is probably because new disruptive elements which wiped out traditions, did not occur. While it is unquestioned that these islands were populated in part from central Polynesia, to a large extent by involuntary immigration, these migrations were never in a position to replace the predominant north Polynesian element which had emigrated from those islands of Micronesia north of the equator, the Carolines. Although current traditions treat the immigrations from central Polynesia as the more important, this may well be because the central Polynesians retain far more the tradition of their roots than is the case with the Micronesians. Also, it is not improbable that the immigrated central Polynesians, as a consequence of their greater intellectual gift, acquired a dominant position in the social life of the small islands without damaging the traditional industry.

Outside central Polynesia the art of weaving is not known anywhere; and at the time of first discovery we find no mention of it. The Malayo-Polynesian group, which settled in central Polynesia undoubtedly never knew the art of weaving, and we can probably assume that this art was also unknown in the Asiatic homeland at the time of the emigration. Only later people who expanded out of Asia across the east Asiatic island groups, brought the skill with them. A section of these people poured over the Carolines, and from there southwards as a weaker stream, still carrying the loom with them and introducing it into Melanesian regions, where they were sufficiently strong in numbers to maintain their own customs and avoid absorption by the greater numbers of the Melanesian population.

Fig. 96 Women of the Greenwich Islands

If we look at the fabrics produced from the looms, we observe that the central Polynesian influence intruded in the bestowing of names. On Nuguria, for example, they weave great lengths of material of wider-meshed texture than the weaving used for clothing, and sew several of these widths together to make a protective net against mosquitoes. Here as on Tauu it is called tainamu. Tainamu is the Samoan designation for the tent-shaped 240device produced from tapa, which is never absent from any house, and is spread out in the evenings to protect the sleepers from mosquitoes. The central Polynesians arriving on the islands did not find the customary material in their new homeland for making the tainamu, but found woven mats from which they could make them, and the old term was retained. On Nukumanu we find the designation tainamu for a completely different mat. Here a tainamu is a narrow, very long, roughly woven mat which is laid on the ancestral image Pau-Pau (fig. 85) as a belt, and in which sick people are wrapped amidst all kinds of incantations by the sorcerer. The woven material on Nuguria and Tauu which is used as tainamu (mosquito netting) is about three times as long as the clothing mats. If the same name is used on Nukumanu for other mats, it is possible that there they learned to weave long mats, weaving with long chains, from the islands to the west, and that the name given there to the item made by this weaving, was transferred to the style of weaving.

Fig. 97 Weaver at work

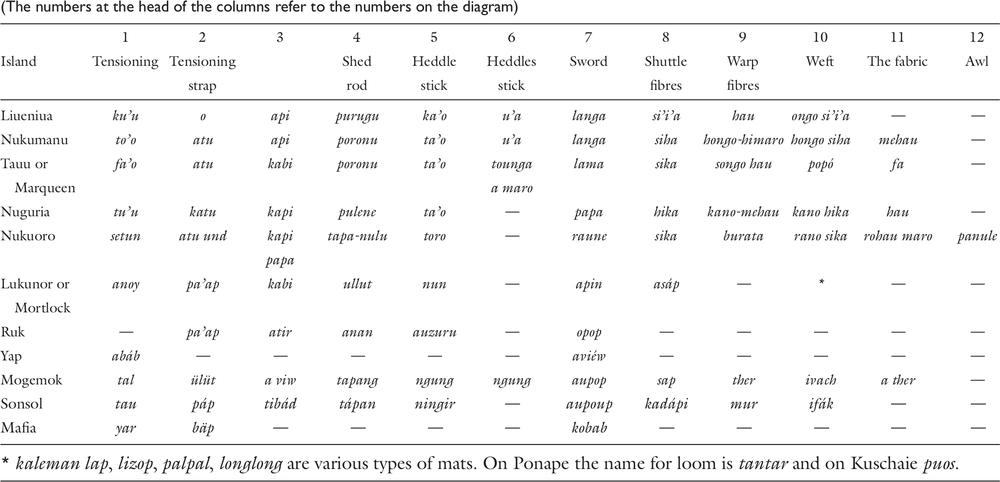

In the summary given on the opposite page, I have listed in table form the names of the parts of the loom on the individual islands, as far as I know them.

The wanderings of the Polynesians from their Asiatic homeland to the east form, on the whole, a still very dim chapter in the history of this people spread so far across the South Seas. Just as we are unable to show the location of their homeland with anything approaching certainty, we cannot indicate with any accuracy the intermediate stops which the wanderers made on their way to the east. If we look at the map of the Pacific Ocean, there are two main routes of migration. The southern route passes via the Sunda Islands, New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, Solomon Islands, New Hebrides, New Caledonia and Fiji; the northern via the Pelau Islands or the Marianas to the Carolines, the Marshall and the Gilbert islands and on from there.

The further we go on the former route from west to east, the more the signs of Polynesian influence accumulate. On the eastern end of New Guinea, in the Bismarck Archipelago, on the Solomon Islands (particularly the southern islands of the group), in the New Hebrides and in Fiji, the Polynesian influence is universally noticeable. It is expressed not only in language but also in the institutions, in the life and customs of the islanders, indeed even in their physical characteristics.

It might, after all, have been possible that a portion of the Polynesians took this route from west to east. They would first have gone along the inhospitable coast of New Guinea, but everywhere they would have found not only a hostile reception from the warlike Papuans, but also a climate that would not have agreed with them because of the prevalent malaria. Both of these factors would have urged them on further, until they finally settled on the island groups to the east of New Guinea, while the majority finally found a permanent home on the islands that are to this day called, in the narrower sense, the central Polynesian islands.

However, I do not believe that this was the route the migrants took. The Polynesian elements that we find today on most of the Melanesian islands are the result of later Polynesian migrations, after they had already firmly established themselves in Polynesia; migrations which, favoured by wind and tide, went mainly from east to west.

These migrations were in part voluntary and conscious expeditions to legendary regions, and Polynesian tradition can tell much about them even today. However, in part, they were involuntary and by chance, when Polynesian seafarers were driven far from their homeland by wind and current, and finally landed on Melanesian islands. This explains why the Melanesian island groups adjacent to the central Polynesian islands, like Fiji, the New Hebrides and the southern Solomon Islands show the most Polynesian influences. These migrations took place since the time of settlement in central Polynesia and extended over a time span of several centuries, since they lasted until recent times; for not a year passes that a Polynesian is not washed ashore on Melanesian islands.

I believe that by the following observation I can demonstrate that the Polynesians came into little if any contact with the Papuans on their migrations from west to east.

It is known that the central Polynesians are a talented folk, very advanced in development. We can assume that the present culture, or more precisely the culture that was found by the European discoverers, was the remnant of an earlier higher culture that had sunk progressively lower during a century of wandering, under countless tribulations and privations and influenced by inferior tribes. The 241intellectual abilities had, however, remained, and so we see with astonishment how Polynesians with careful education quickly reveal themselves to be the equal of the whites. During their wanderings these talented people would undoubtedly have adopted such arrangements as afforded obvious advantages. I want to present two of them here, which the Polynesians must have grasped as advantageous novelties during their wanderings along the coast of New Guinea, in the event that they took this route.

Table 2: Comparative summary of the names of individual parts of the loom on different islands

Fig. 98 Loom from Nukumanu. (The numbers refer to Table 2, above)

The first is pottery. Along the entire previously described southern route the Polynesians would have encountered people who were expert at pottery and who used the clay vessels for their food preparation. I want to mention also that such a migratory journey originally would probably have consisted predominantly of men, and that during their wanderings they would often have taken native (that is, Papuan) women as wives or slaves. It is known that in New Guinea and on several Melanesian islands the manufacture of pottery is a task of the women. On their wanderings the latter would certainly have continued to practise their skills, the more so since the raw material was found everywhere and the preparation of food in earthen cooking vessels is far quicker than the Polynesian style of cooking with glowing stones. Nevertheless pottery has remained totally foreign to the central Polynesians; nor did the earliest discoverers report anything about this art. We must therefore assume that the central Polynesians did not know pottery in their original homeland, nor did they come into contact with people who were familiar with this craft. It seems beyond doubt that on grounds of expediency the Polynesians would have adopted cooking in earthenware containers had this method been shown to them. Their wanderings were not overland but by sea in more or less seaworthy canoes. Now, it is obvious that the cooking of food in pots on extended sea voyages would have afforded significant advantages over the original method with hot stones. Firstly, they would not need to weigh the canoes down by transporting stones, and they would need far smaller quantities of flammable material, two items that would need to be taken into great consideration on long voyages in small canoes. Even today on the New Guinea coast we see small mud fireplaces on the vessels, serving as hearths for the cooking pots; how enlightening would the 242advantage of such an arrangement have been to the ancient Polynesians, had they had the opportunity of becoming acquainted with it. On these grounds I conclude that they did not take the southern route via New Guinea and the Melanesian islands.

A second point, which would have been adopted as an important innovation by such a talented and also warlike people as the Polynesians, is the use of bows and arrows as weapons. On the journey along the New Guinea coast and further eastwards, the Polynesians would have been dealing almost continually with tribes who used bows and arrows as weapons. Since contact between the travellers and the local population was as a rule hostile, one can regard this as certain. In my opinion the Polynesians would very quickly have grasped the advantage of the bows and arrows over the club and the spear, and adopted the better weapon. However, we can produce no case among the central Polynesians where bow and arrows are used as weapons. They have stuck to the weapons of their original homeland, the spear and the club, because on their wanderings they have not encountered peoples from whom they could have learned the use of a more consummate weapon.1

In my opinion, only the northern route remains as a path of migration, via the Carolines, the Marshall and Gilbert islands, and the available facts corroborate this route.

However, I want to premise here that I set the immigration of the Polynesians into the South Seas in two completely separate periods, which I differentiate as the immigration of the original Polynesians whose remnants are the central Polynesians of today, and the far later immigration of a closely related tribe, who expanded through the Carolines, the Marshall and Gilbert islands, and then in later centuries were succeeded by a new invasion with central Polynesian elements.

The migration of the central Polynesians most probably took place much further back in time than one usually believes, although there is no possibility of fixing the time precisely. Percy Smith, in his book Hawaiki, the Original Home of the Maori, specifies a genealogical tree of the rulers of Rarotonga that extends back to 450 BC. However, such traditions are to be treated with caution and should not be regarded as absolute historical documents.

We can hardly err if we assume that the migrations did not begin suddenly, like a downpour, and then stop. They probably extended over longer periods; the tribes set out on their migration to the east at a favourable time each year, and gradually reached the place where they finally settled in present-day central Polynesia.

On the other hand, somebody will introduce the direction of the ocean currents and the prevailing wind as evidence that the original Polynesians would not have been able to take this route. I must object to this, for after many years in the South Seas and supported by numerous observations, neither currents nor wind would have been an obstacle. Admittedly the direction of both these factors is predominantly east-west, but there are times of the year when both are not only very weak but even take the opposite direction. On many occasions between the equator and the Carolines I have encountered currents setting from north-west to south-east, and many sea captains have had the same experience, whereas handbooks give an east-west direction. Knowledge of the oceanography of the Pacific Ocean is still far from precise; so much is certain, that the currents in particular do not repeat constantly, from year to year. Where one encountered an easterly flow one year, the following year at the same time one often rode into a strong westerly current. A people who were skilful seafarers, certainly found no difficulty in pushing on from east Asia towards the east, especially when they were driven by boundless expectations of the beauties and bounties that the east seemed to promise.

Of course the journeys scarcely ran precisely along the same route. Storms occurred, adverse currents set and the travellers wandered here and there. Many would have been sacrificed, paying for their daring with their lives, and finding their death in the depths of the ocean.

In spite of all the difficulties, we see that the wanderers finally attained a goal and settled on the islands that they still inhabit today. Even today, through numerous small traits and habits of the central Polynesians, the remnants of characteristics that were adopted during the years of migration are revealed to the observer. Having, for the most part, to rely on the sea, the wanderers became superb fishermen; but when driven by hunger they also learned to value all other sea and reef inhabitants as food as well as the tastier fish; and in Samoa, for example, we still find today that scarcely a creature exists in the sea or on the coral reef, that does not serve wholly or in part as a source of food, no matter how unappetising the outward form might be. The far inferior Melanesians still look today with disgust and shuddering at how the Samoans, for example, consume with great relish reef animals that they themselves would only touch reluctantly, let alone use as food, although they otherwise enjoy their food.

The inconstancy in the character of most Polynesians, their restlessness and the littledeveloped sense for steady methodical work, is, in my opinion, a consequence of long years of wandering. Accumulating property, sacrificing oneself for one’s neighbours, were hardly possible on their journeying. Everyone looked after themselves, provided for the current day; it was uncertain what tomorrow might bring. Whoever

243had something, shared it with his friends as far as it would go. If there was a surplus it was indulged to the utmost squandering, even when one could expect the most severe want the following day. We still find all of these characteristics in many central Polynesians.

After the arrival of the central Polynesians at their present home, a second, much later, great stream of migration from the west poured over the equatorial islands, the Carolines, the Gilbert Islands, and so on. These migrants mingled with the earlier arrivals and from this mixture arose the group recognised today as Micronesians. This later migration brought to the east a people who were far more closely related to the present Malayans and Tagals than to the original Polynesians. Even today on many of the Carolines we are astounded to find almost pure Tagalish or Malayan types. Natives of Amboina and natives of the Ruk Islands, for example, are similar to the point that they are very easily mistaken. This migration stretched eastwards but not beyond the Gilbert Islands; to the south, one branch found its way to the Greenwich Islands (Kapingamarangi), Nuguria, Tauu, Nukumanu, Liueniua, Sikaiana, as far as the New Hebrides. This branch brought the loom with it and the art of weaving.

This southern migration also reached the coast of the current New Ireland2 as well as the outer islands offshore, and the many traces of Micronesian elements that we still find there today can therefore be explained. Of course the wanderers encountered a very large Papuan population on these large islands, on whom they were unable to impose their characteristics to such a great degree as on the small islands; for the most part they lost their characteristic features and attributes in the gradual intermingling, and adopted the characteristics of the people in their new homeland. On the small islands further to the west, Luf, Kaniet, Ninigo, Wuwulu and Aua, they remained closer to the original state. On Wuwulu and Aua we find the group maintained in its purest form, but on the other islands strong Melanesian influences have, over time, become important. That a continued migration southwards was not able to leave significant traces, I ascribe above all to the climate. Further southwards lay New Guinea, New Britain, the Solomon Islands, all areas where malaria is endemic, and since even today a Caroline Islander who goes to this region is quickly laid low by malaria, the same would certainly occur in that distant past.

On their wanderings to the south-east this Polynesian group was held up by the centra or original Polynesians, who had decamped once more, from their barely chosen homeland, and undertaken new migrations. The reason for these new migrations is unknown to us. Possibly they were a consequence of the inbuilt wanderlust of the central Polynesians. However, it is not impossible that natural events of extraordinary extent, especially volcanic eruptions, had caused the migrations. Even today on the Gilbert Islands there are legendary traditions3 which establish that an initial immigration took place from Samoa, and that these immigrants maintained connections with their home island until a mighty volcanic catastrophe lead to settlement of all the Gilbert Islands. Likewise on Ponape they have traditions of invasions by central Polynesian people who followed a route via the Gilbert Islands and overthrew the old dynasty on Ponape, established new rulers and brought in new customs and institutions.

This latter, intentional emigration of the original Polynesians, sending its waves as far as Ponape, probably coincides with the emigrations that found their goal in New Zealand.

That powerful volcanic eruptions of relatively recent date have taken place in the Samoan Islands, are witnessed by the mighty, bare lava flows on the island of Sawaii, stretching from the centre of the island, as far as the north coast. Many years ago, not without great effort, I traversed this huge lava flow to its source; during a strenuous excursion taking several days. Everywhere one strides over a field of solid lava, which gives the impression that it had only just assumed a solid form. Numerous large and small craters, just as bald and naked as the laval fields, indicated the source of the latter. In many places I could clearly trace, for long stretches, the parallel lava flows of individual craters. The small eruption on the island of Sawaii in 1902 demonstrated that the volcanic activity has still not been extinguished.

Many things previously unclear to us, can in my opinion be explained by the preceding hypothesis. Let us reach back, for example, to the genesis of the mighty stone structures at Matalanim on Ponape.