5

How is prostate cancer diagnosed?

The Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test first became available in 1987 and began to be widely used and promoted thereafter. The test is done by obtaining a blood sample which is then sent to a pathology laboratory for analysis. The test measures the level of Prostate Specific Antigen in the blood. Prostate Specific Antigen is a protein made mainly in the prostate gland and low levels of PSA are normally present in the blood. As a man ages, the prostate grows and the level of PSA also increases. A high PSA in the blood almost always means that something is wrong with the prostate, but not necessarily that it is prostate cancer. The causes of a high PSA include the benign (non-cancerous) growth that accompanies ageing (benign prostatic hyperplasia, BPH) (see p22), inflammation or infection of the prostate (prostatitis) (see p21) and, least commonly, prostate cancer.

What is the range of PSA levels?

PSA results are returned from the pathology lab expressed as nanograms of PSA per millilitre (ng/mL) of blood. Your PSA test will produce a number and your doctor should try to explain the meaning of that number to you. However this isn’t easy because the PSA test is not an accurate test for detecting prostate cancer and understanding what your number means is far from straightforward. It has been conventional to regard a PSA level of 4 ng/ml or higher as 59“abnormal”, and values less than 4 ng/ml as “normal”. Results over 4 ng/ml are likely to lead to a recommendation to have a biopsy of the prostate to see why the PSA level is “raised”. However, as described above, there are many reasons why PSA levels can rise, without any cancer being present. In fact most men with PSA levels of 4 ng/ml or more don’t have prostate cancer. In several studies, about 30% of men with PSA levels of 4 ng/ml or higher were found to have prostate cancer, meaning of course that the other 70% did not have cancer [71].

To complicate things further, having a PSA level less than 4 ng/ml does not mean a man does not have prostate cancer. In one large US study, prostate cancer was diagnosed in 15% of men with PSA less than 4 ng/ml [72]. Because of this, there has been a trend toward dropping the threshold for an “abnormal” PSA test result. In the large European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (more on this study later) the threshold for “abnormal” was dropped from 4 ng/ml to 3 ng/ml. Other experts have suggested different thresholds for “abnormal” according to age, because PSA levels tend to rise with age. According to this approach, a PSA level of up to 2.5 ng/ml is considered normal for a man in his 40s, but a PSA level of up to 6.5 ng/ml is considered normal for a man in his 70s (see Table 8). However there is no evidence to date that these age-adjusted thresholds result in better health outcomes, and there is still no consensus about which threshold(s) should be used to call a result abnormal. For example in 2009, the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand proposed PSA testing for men from the age of 40 and suggested a PSA level of 0.6 ng/ml be considered “higher risk” for a man aged 40 and a PSA of 0.7 ng/ml be considered “higher risk” for a man aged 50. 60

Table 8: Upper limits of “normal” for PSA at different age groups (ng/ml)

| Age range | Upper limit of normal |

|---|---|

| 40–49 | 2.5 |

| 50–59 | 3.5 |

| 60–69 | 4.5 |

| 70–79 | 6.5 |

Source: [73]

While using lower thresholds for an “abnormal” or “higher risk” result has the advantage of detecting more prostate cancers, there are two problems with this approach. The first is that, as we’ve seen, there is a big reservoir of indolent prostate cancer and there is no evidence that finding all these cancers will be beneficial or result in fewer deaths from prostate cancer. The second is that by dropping the threshold, many more men get caught up in the medical net of “abnormal” or “higher risk” and then have more tests including prostate biopsies. For example, in a community sample of men having PSA tests, using a threshold of 3.5 instead of 4 ng/ml for men aged 50–59 years, twice as many men (4% vs 2%) received an “abnormal” result. Dropping the threshold to 0.7 ng/ml could result in approximately half of all men in this age group receiving a “high risk” result, and being sent for more blood tests and/or biopsies with all the inconvenience, anxiety, risks and costs involved in these extra tests.

In summary, there is no agreement about what constitutes a normal or abnormal PSA level: there is no “threshold” PSA score from which you can conclude that you are or are not highly likely to have prostate cancer. The above studies demonstrate that the PSA test has both poor “sensitivity” (ability to detect cancer if it’s there) and poor “specificity” (ability to give a true negative), leading to 61many false alarms or false positive results. All this means that many men are unnecessarily subjected to prostate biopsies because of the imprecision of the test. And a prostate biopsy is by no means a trivial and risk-free procedure (see p62). Perhaps the only clear thing we can say is that in general, the higher a man’s PSA level, the more likely it is that cancer is present.

Dr Richard Ablin, the scientist who discovered the Prostate Specific Antigen in 1970, wrote forcefully about it in March 2010 in The New York Times, describing the test’s popularity as “a hugely expensive public health disaster”. He continued

the test is hardly more effective than a coin toss. As I’ve been trying to make clear for many years now, P.S.A. testing can’t detect prostate cancer and, more important, it can’t distinguish between the two types of prostate cancer — the one that will kill you and the one that won’t.

Ablin pulled no punches.

So why is it still used? Because drug companies continue peddling the tests and advocacy groups push ‘prostate cancer awareness’ by encouraging men to get screened. Shamefully, the American Urological Association still recommends screening … Testing should absolutely not be deployed to screen the entire population of men over the age of 50, the outcome pushed by those who stand to profit. I never dreamed that my discovery four decades ago would lead to such a profit-driven public health disaster. The medical community must confront reality and stop the inappropriate use of P.S.A. screening. Doing so would save billions of dollars and rescue millions of men from unnecessary, debilitating treatments. [74]62

What happens if you have a high PSA score?

A high PSA score causes concern (and as we have seen, what is meant “high” is by no means clear – it can be in fact as low as 2.5, according to some [73]). But if your doctor interprets your PSA as “high” then two options are available. The first is known as early stage “active surveillance” or “expectant management”. Basically, active surveillance at this stage will involve urging you to have more regular PSA tests and probably digital rectal examinations to monitor your prostate.

But the second option is to refer you for a biopsy [75].

What happens when you have biopsy for prostate cancer?

A biopsy involves the extraction of body tissue via a needle so that the tissue can be then examined by a pathologist. The prostate is biopsied through the rectum and the procedure usually takes 10 to 15 minutes. The procedure is performed by a urologist. An ultrasound device is used to view the prostate on a monitor and guide the biopsy needles. A lubricated ultrasound sensor is passed into the rectum. For some this is uncomfortable, but not usually painful.

The biopsy needles are introduced through the shaft of the ultrasound sensor. The needles are then pushed through the rectal wall into the adjacent prostate gland. The needles collect at least 12 samples of prostate tissue which are then sent to a pathologist for testing. A sharp stinging sensation is sometimes experienced. Occasionally the biopsy is not successfully completed and may need to be repeated.

Common side effects of prostate biopsy include:

- pain or discomfort in the rectal area

- distress caused by the sound of the biopsy gun

- anxiety about the biopsy and its results 63

- blood-stained urine or faeces – this can last up to a week or two. One large Dutch study found blood-stained urine in 23.6% of men [76]

- blood-stained or discoloured semen – this may last for six weeks. The same large study found 45.3% of men had blood in their semen

- difficulty in passing urine – this usually improves quickly.

More serious complications can also arise, although less often. These can include urinary or bowel infection, and far more uncommonly, massive life-threatening rectal bleeding [77], septicaemia (infection of the bloodstream) and even death [78]. In the large Dutch study referred to above, 0.4% (67) of 1687 men who had undergone biopsy had complications serious enough to be admitted to hospital following the procedure. The biopsy needles have to pierce the rectal wall to get to the prostate and bacteria from the bowel may cause an infection. A dose of antibiotic is often given to reduce the risk of infection.

What are the downsides to being told “you have cancer”?

The first consequence of being told that you have cancer in your body is that you henceforth will think of yourself as a man who has cancer. This may seem so obvious as to be hardly worth mentioning, but it bears careful reflection. Knowing that one has cancer can often be an emotionally traumatic experience which can preoccupy some men, causing anxiety and particularly prolonged and repeated periods of depression [6].

But as we have been saying throughout the book, the prostate cancer that you have stands a high chance of being a cancer that may never harm you.

As well, the knowledge that you now have cancer may impact on lives in subtle ways. For example knowing you have prostate cancer may 64affect your health insurance or life insurance. It can also reverberate around families because it means everyone else now has a relative affected by prostate cancer. That knowledge in turn affects the way doctors and insurance companies will perceive your male relatives as being at higher risk of prostate cancer.

A recent study from Sweden adds important evidence to the debate that getting a prostate cancer diagnosis can increase your risk of having a cardiovascular event or taking your own life. The editors of the highly regarded medical research journal which published the study (PLoS Medicine) summarised the study this way:

The researchers identified nearly 170,000 men diagnosed with prostate cancer between 1961 and 2004 among Swedish men aged 30 years or older by searching the Swedish Cancer Register. They obtained information on subsequent fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events and suicides from the Causes of Death Register and the Inpatient Register (in Sweden, everyone has a unique national registration number that facilitates searches of different health-related Registers). Before 1987, men with prostate cancer were about 11 times as likely to have a fatal cardiovascular event during the first week after their diagnosis as men without prostate cancer; during the first year after their diagnosis, men with prostate cancer were nearly twice as likely to have a cardiovascular event as men without prostate cancer (a relative risk of 1.9). From 1987, the relative risk of combined fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events associated with a diagnosis of prostate cancer was 2.8 during the first week and 1.3 during the first year after diagnosis. The relative risk of suicide associated with a diagnosis of prostate cancer was 8.4 during the first week and 2.6 during the first year after diagnosis throughout the study period. [This means that compared with men 65not diagnosed with prostate cancer, men given a diagnosis were 8.4 times more likely to commit suicide in the week after being given the news, and 2.6 times more likely in the year after diagnosis.] Finally, men younger than 54 years at diagnosis had higher relative risks of both cardiovascular events and suicide.

These findings suggest that men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer have an increased risk of cardiovascular events and suicide … these findings strongly suggest that the stress of the diagnosis itself rather than any subsequent treatment has deleterious effects on the health of men receiving a diagnosis of prostate cancer … this new information should be considered in the ongoing debate about the risks and benefits of PSA screening. [79]

However, another very recent Swedish study which compared men who had had prostate cancer detected after a PSA test with age-matched men without prostate cancer in the general population and also with men with advanced or metastatic prostate cancer found that there was no increased risk of suicide in the newly diagnosed men, whereas the risk was twice as high among men with locally advanced or metastatic disease, compared with the age-matched male population [80].

What do stage, grade and Gleason score mean?

Prostate cancers are often described by their stage, grade, or Gleason score [81].

A cancer’s stage refers to its extent at diagnosis, in other words, the parts affected by the cancer when it first became evident. Staging is important to both estimating prognosis and selecting treatment. The most common staging system is the TNM system which summarises 66the extent of the primary tumour (T), spread to local lymph nodes (N), and spread to other parts of the body (M) by assigning numbers to each of these letters.

The most important distinction in staging a prostate cancer is whether or not it appears confined to the prostate. In T1 and T2 cancers, the primary tumour is confined to the prostate, whereas in T3 and T4 cancers, the primary tumour has grown beyond the prostate into adjacent tissues. T1 and T2 cancers are often referred to as “early stage cancers” and have the best outlook, with or without treatment. T3 and T4 are more serious and are often referred to as “locally advanced cancers”. N1 cancers have evidence of spread to local lymph nodes, N0 cancers do not. M1 cancers have evidence of spread to other parts of the body, M0 cancers do not. Prostate cancers that have spread to local lymph nodes or beyond are incurable and are referred to as metastatic cancers.

There are several ways of determining evidence of spread beyond the prostate. These include computed tomography (CT or CAT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to assess spread within the pelvic region, and radio-isotope bone scans to assess spread into bones. These scans are often called staging tests.

The problem with staging tests is that they are not 100% reliable. The main limitation is that no test is sensitive enough to detect cancer spread at its earliest stages, so a normal result does not rule out the possibility of cancer spread. So while these tests and staging are a helpful guide, they are not conclusive.

Cancers that appear confined to the prostate (T1–2 and N0 and M0) are potentially curable, whereas those that have spread beyond the prostate and its related lymph nodes (M1) are not curable with current treatments. Many prostate cancers involve adjacent tissues (T3–4) or related lymph nodes (N1) at diagnosis; these locally 67advanced cancers are amenable to treatment, but their curability is controversial.

A cancer’s grade refers to how aggressive its cells look under a microscope. The Gleason score is the standard way of classifying a prostate cancer’s grade. It is named after Dr Donald Gleason, a pathologist at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Hospital who developed it with other colleagues in the 1960s. The Gleason score reflects how different the tumour looks from normal prostate tissue and suggests how aggressively it is likely to behave.

To calculate the Gleason score for a prostate cancer, the pathologist looks at all available specimens and assigns a score from 1 (least aggressive looking, or low grade) to 5 (most aggressive looking or high grade) to the most common pattern and second most common pattern they see. Adding these numbers together gives the cancer’s Gleason score from a minimum of 2 (1+1 = least aggressive, lowest grade) to a maximum of 10 (5+5 = most aggressive, highest grade). In practice, it is unusual for pathologists to report a Gleason score of less than 4 (2+2). Most cancers have Gleason scores between 5 and 10.

A lower Gleason score (5 or less) suggests that the cancer is growing slower, less likely to spread beyond the prostate, and therefore behaving less aggressively. Such cancers are often referred to as “low grade”. A higher Gleason score (8 to 10) suggests that the cancer is growing faster, more likely to spread beyond the prostate, and therefore behaving more aggressively. Such cancers are often referred to as “high grade”. Most men with prostate cancer have a Gleason score in the middle (6 or 7). These cancers are often referred to as “intermediate grade”.

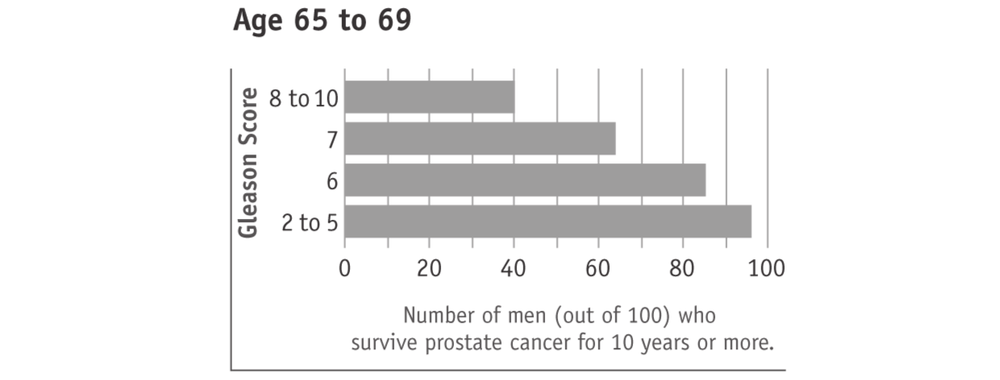

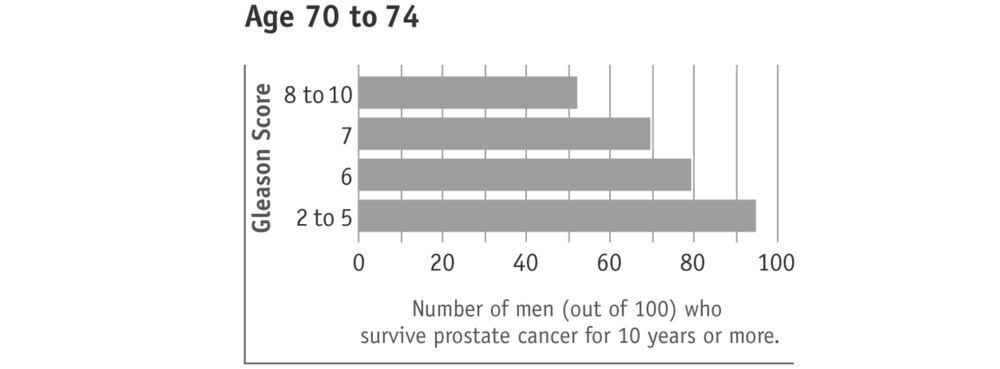

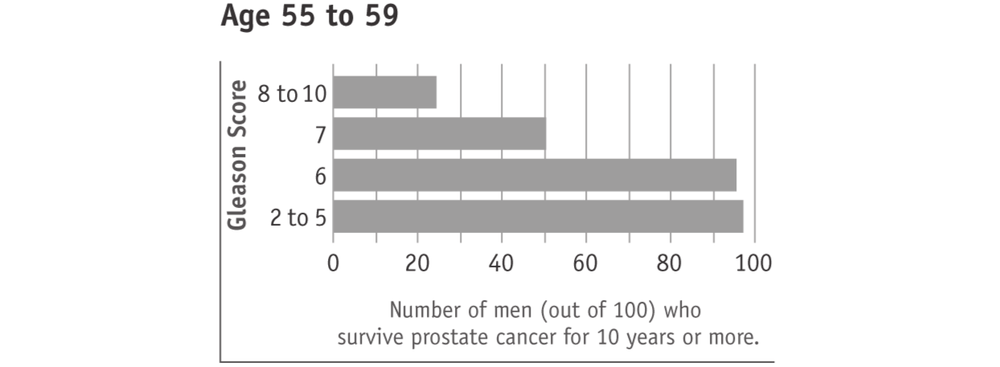

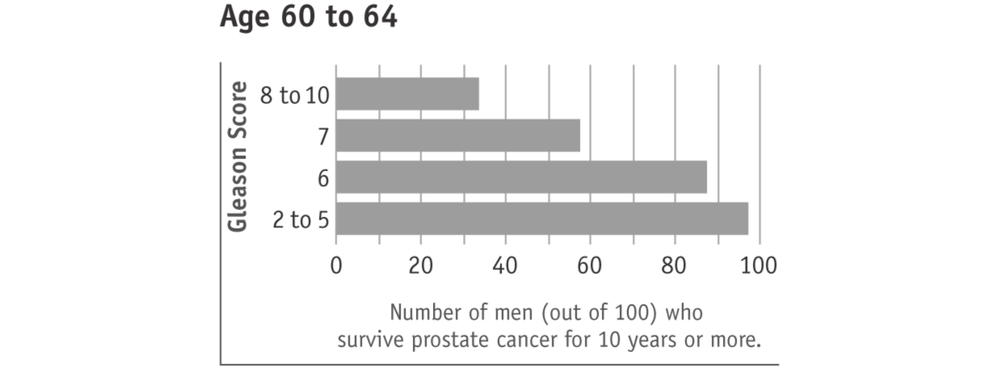

Surviving prostate cancer is more likely with lower Gleason scores (see charts below). This is true with any prostate cancer treatment 68or watchful waiting. In the charts, “age” means the man’s age when the cancer was found. The men in this research study used watchful waiting or hormone treatment. It should also be kept in mind that most men who survived prostate cancer died of other causes.

Tumours with higher Gleason scores (8 to 10) are described as aggressive. They are likely to grow and spread beyond the prostate within five years. Men with higher Gleason score prostate cancers therefore have potentially more to gain from active treatment. However, prostate cancers with higher Gleason scores are also more likely to have spread beyond the prostate and are therefore more difficult to cure.

69

69