6

What are the treatments for early stage prostate cancer?

If a prostate biopsy and staging tests reveal an early stage cancer, then a number of options are available to you. The first is active surveillance or “watchful waiting”. This is an option frequently offered to men with tumours which have a low Gleason score (e.g. 5 or 6). These cancers are often slow growing, and may never cause you harm. If you opt for watchful waiting, this basically means that for the time being, you and your doctor agree that you will have no treatment but instead, you will undergo regular check-ups (PSA, digital rectal examination, and probably further biopsies). Your doctor will thus know if there is evidence that the cancer is progressing and the risk of spread and further problems is increasing and warrants prostatectomy or radiation.

If you and your doctor decide to treat the cancer, then there are three main options: surgery to remove the cancer; radiation to eradicate the cancer; and hormonal treatment to try to get the cancer under control. Sometimes radiation and hormonal therapy are given in combination. Your doctor may recommend you have hormonal therapy before, during and/or after radiotherapy.

Radical prostatectomy is the complete surgical removal of your prostate. It will only be of potential benefit to men who have early stage prostate cancer which has not spread beyond the prostate. If your cancer has spread (metastasised) beyond the prostate and 71surrounding tissues, then surgery is unable to eradicate the cancer on its own. A radical prostatectomy is not a minor operation. It is conducted under general anaesthetic. General anaesthetics have their own risks. A radical prostatectomy can be performed “open” through one large incision (5–10 cm), or “laparoscopically”, using instruments passed through several smaller incisions.

Retropubic prostatectomy (open) is the most common procedure in Australia. Here, an incision of 8–10 cm is made between the navel and pubic bone through which the prostate and surrounding pelvic lymph nodes are removed. An open retropubic prostatectomy generally takes two and a half to three hours if nerves are not spared and three and a half to four hours if nerves are spared (see below). Removing the prostate means that the part of the urethra travelling through the prostate gland is also removed. The two ends of remaining urethra are then reattached in a connection called an anastomosis.

Perineal prostatectomy is an older open approach, where the prostate is removed through a 5 cm incision in the perineum – the skin and muscles between the scrotum and anus.

Nerve-sparing surgery is designed (as the name implies) to minimise the number of nerves adjacent to the prostate that are damaged during the operation. Bundles of nerves on either side of the prostate are responsible for erections and can be either removed or damaged by surgery. If they remain undamaged, men may have a higher chance of regaining erections after surgery, typically within two to 12 months.

Some may ask why all prostatectomies are not nerve sparing? Surely, good surgeons would always seek to minimise damage to nerves? The problem is that these nerves are small, difficult to identify, fragile, and run along the outer surface of the prostate. Attempts to spare these nerves increase the risk that some prostate cancer will 72be left behind, particularly if the cancer extends close to where the nerves pass.

Laparoscopic prostatectomy is a newer approach using a thin, tube-like instrument (laparoscope) which allows the surgeon to see inside the abdominal cavity and remove the prostate with other long thin instruments inserted through a series of small incisions. This operation is more demanding for surgeons than open prostatectomy because of the difficulty working through smaller incisions. Recovery times may be quicker because the incisions are smaller, however the operation often takes longer than an open prostatectomy and the risk of cancer recurrence may be higher.

Robotic prostatectomy is an even more recent surgical option that has received a lot of publicity. This involves the urologist using a machine to perform a laparoscopic prostatectomy. The surgeon operates instruments with a console rather than directly. Because it has received so much attention, we deal with this option in greater detail below at page 84.

A highly detailed account of what is involved in radical prostatectomy, including descriptions of problems that can arise can be found on Cornell University’s Department of Urology website (www.cornellurology.com/prostate/treatments/prostatectomy.shtml).

Radiotherapy is a potentially curative treatment option when cancer has not spread beyond the prostate. Radiotherapy can also be used to treat symptoms caused by cancer cells that have spread to other parts of the body (metastasised).

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is an external radiation therapy used in the treatment of prostate cancer. It is administered by a radiation oncologist after carefully mapping the prostate gland. For early prostate cancer, a typical course of treatment would see you have daily sessions (with weekends off) for four to seven weeks. Each session lasts a few minutes and is painless. 73

There are two main types of externally delivered radiotherapy: conformal, and IMRT (Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy). With conformal radiotherapy, the radiotherapy device contours the radiation beams to match the prostate’s shape. This seeks to reduce the radiation received by healthy cells in adjacent organs such as the bladder and rectum, therefore reducing the side effects of radiotherapy.

IMRT is a newer, more complex type of conformal radiotherapy and allows the radiotherapist to vary the dose of radiation given to different parts of the tumour and surrounding tissue. It is not yet known whether IMRT is better than conformal radiotherapy.

A perfect session of external beam radiation therapy would affect only the targeted area without causing side effects in surrounding organs. Unfortunately, it is impossible to treat a tumour using external radiation therapy without affecting the surrounding tissues through which the radiation beams must pass.

Brachytherapy (from the Greek brachy, meaning “short distance”) is radiation therapy delivered directly to a tumour, or from within it, and also known as internal radiotherapy, implant therapy, seed implantation or sealed source radiotherapy. Brachytherapy is commonly used as a treatment for prostate and cervical cancers and can also be used to treat tumours in other parts of the body. Brachytherapy can be used alone or in combination with other therapies such as EBRT and hormonal therapy.

Brachytherapy requires the placement of radiatioactive sources within the tumour under a general or a spinal (epidural) anaesthetic. Around 80–100 small radioactive metal “seeds” can be inserted into the tumour allowing radiation to be released slowly over about six months, after which they are depleted. The seeds are left in the tumour and not surgically removed. They are inserted through the skin between the prostate and the anus, and guided into the 74prostate gland. Other methods involve the temporary placement of radiatioactive pellets in the tumour for shorter periods over a few days or weeks. As the procedures can cause some swelling of the prostate, which can lead to blockage of the urethra, a catheter is sometimes inserted into the bladder to drain urine. This may be removed after a couple of hours or left in place overnight.

The seeds are not removed and there is little risk of radiation from them affecting other people, although the UK’s Macmillan Cancer Support organisation does caution that:

women who are (or could be) pregnant and children should not stay very close to you for long periods of time. You should not let children sit on your lap, but can hold or cuddle them for a few minutes each day and it is safe for them to be in the same room. [84]

A major advantage of brachytherapy is that the irradiation only affects a very localised area around the radiation seed implants. Exposure to radiation of healthy tissues further away from the sources is therefore reduced. In addition, if the patient moves or if there is any movement of the tumour within the body during treatment, the radiation sources retain their correct position in relation to the tumour. These characteristics of brachytherapy provide advantages over EBRT – the tumour can be treated with very high doses of localised radiation, while reducing the probability of unnecessary damage to surrounding healthy tissues.

A course of brachytherapy can be completed in less time than other radiotherapy techniques. This can help reduce the chance of surviving cancer cells dividing and growing in the intervals between each radiotherapy dose. Patients typically have to make fewer visits to the radiotherapy clinic compared with EBRT, and the treatment 75is often performed on an outpatient basis. This makes treatment accessible and convenient for many patients.

No randomised trials comparing the efficacy of these various forms of radiotherapy are available.

Hormonal therapy, also known as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) aims to keep cancer cells from getting the male hormones they need to grow. It is called systemic therapy because it can affect cancer cells throughout the body. Systemic therapy is used to treat cancer that has spread. Sometimes this type of therapy is used to try to prevent the cancer from coming back after surgery or radiation treatment.

There are several forms of ADT. Orchiectomy is a form of surgery to remove the testicles, which are the main source of male hormones. This was introduced in 1942 as the first hormonal treatment for prostate cancer. Although it involves an operation, orchiectomy is considered a hormone therapy because it works by removing the main source of male hormones. Despite sounding drastic, this surgery is simple, quick, and has few risks.

Drugs known as luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists (LHRHA) prevent the testicles from producing testosterone. These drugs are injected or placed as small implants under the skin every one, three or four months. Examples are leuprolide, goserelin and buserelin. All are equally effective. They work by stopping the pituitary gland from releasing hormones that stimulate testosterone production [85].

Drugs known as peripheral anti-androgens block the effects of testosterone in the blood stream on cells in the prostate and elsewhere. These drugs include the “utamides” (bicalutamide, flutamide, nilutamide) and cyproterone. These drugs are usually used to boost the effects of LHRHA or orchidectomy. 76

So which treatment is best?

There is a shortage of high-level evidence to answer this very obvious and reasonable question. The US Preventive Task Force’s 2008 review concluded that “Two recent systematic reviews of the comparative effectiveness and harms of therapies for localized prostate cancer concluded that no single therapy is superior to all others in all situations” [86, 87]. This means that if you decide to be treated for prostate cancer, you and your doctor will need to consider any pre-existing problems that you might have which might be relevant to the treatment you have.

For example, men with urinary problems might be advised against brachytherapy because it can make these symptoms worse. Men with bowel problems would likely be discouraged from external beam radiation therapy because it can affect the rectum as well as the prostate. Nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy is typically selected where high importance is placed on the preservation of sexual function.

Unfortunately, there is no treatment which comes with any assurance or even high probability of avoiding serious unwanted side effects.

Will having a radical prostatectomy save your life?

Let us now assume that you have had a biopsy and staging tests that indicate an “early stage” prostate cancer (T1 or T2, N0, M0). Should you have your prostate removed or should you “watchfully wait” under your doctor’s supervision to see if things progress, and then consider medical intervention?

In 2005, The New England Journal of Medicine published a study of what happened to 695 men diagnosed with early stage prostate cancer with an average age of 65 years who were randomised to prostatectomy (347 men) or watchful waiting (348 men) [82]. As 77the men were recruited into the study over several years, the follow-up periods differed, with an average period of eight years. At the time the study reported its results, 83 (23.9%) of the men who had had surgery had died from any cause, compared with 106 (30.5%) of the watchful waiting group. Thirty (8.6%) of the men allocated prostatectomy died from prostate cancer, while 50 (14.4%) of the men allocated to the watchful waiting group died from prostate cancer. We can put this another way: if 1000 similar men with early stage prostate cancer had prostatectomies, then 86 of them will have died from the prostate cancer within the next eight years, while if 1000 similar men were managed with “watchfully waiting” then 144 will have died from prostate cancer. Radical prostatectomy would therefore prevent 58 deaths per 1000 men (an absolute reduction in prostate cancer death of 5.8%, but a 40% reduction if you choose to emphasise the relative risk reduction – see p17).

In 2008, the authors of this study reported results from three more years of follow-up of the men (when the men had been followed for an average of nearly 11 years). By then a total of 137 men in the surgery (radical prostatectomy) group had died compared to 156 of the men in the watchful waiting group. Forty-seven (13.5%) of all the men in the surgery group, compared with 68 (19.5%) of the men in the watchful waiting group had died of prostate cancer [83]. In other words, men who had radical prostatectomy were less likely to die from prostate cancer in the subsequent eleven years than men managed with “watchful waiting.” The study also found that men who had radical prostatectomy were less likely to progress to advanced prostate cancer (involving spread of the cancer beyond the prostate gland itself).

What are typical side effects of being treated for prostate cancer?

There is a bewildering range of claims and counterclaims made about adverse side effects of being treated for prostate cancer. When 78reading websites set up by specialists offering prostate surgery and other treatments, you should note the oblique wording and the use of heavily qualified language (“may”, “might”, “should”, “often”, “usually”, “commonly”) concerning the lack of problems about the treatment that the urologist is offering. Such words are chosen wisely by the owners of such websites because no definite or absolute claims can be made in advance of treatment as the outcome can vary enormously.

Studies looking at the outcomes of medical interventions, including adverse events like serious side effects, should ideally be conducted by researchers who have no competing interests in the results of such studies. For example, a surgeon evaluating his or her own surgical results would always be mindful of the impact of publicity that might follow from results that showed high levels of adverse outcomes. Also patients may be reluctant to complain, or may have little opportunity to complain of side effects to their surgeon, but may feel more able to give an accurate picture of adverse effects to impartial research staff.

This factor is something that all men should keep very much in mind when reading websites or other material that hint that the surgeon being described has a strong success record. It is rare for surgeons to have independently conducted studies evaluating the history of their surgical performance. Many such studies exist but they are almost always without identification so that readers are unable to know to which surgical practice or surgeon they refer. Surgeons are not like musicians or architects whose work can be easily accessed on recordings or by looking at buildings.

When a surgeon advises you on the probabilities of various outcomes occurring, it is always sensible to compare what you are told to the results obtained by independent studies, particularly those which 79pool together individual studies to provide a synthesis of what a whole range of single studies show when considered together.

The New South Wales study

One very recent study was published by researchers from New South Wales. The researchers approached all men aged less than 70 years living in NSW, who had been diagnosed with histopathologically (laboratory) confirmed prostate cancer, clinical stage T1a to T2c with no evidence of lymph node or distant metastases, between October 2000 and October 2002, and notified to the NSW Central Cancer Registry by May 2003 (or no more than 12 months after their diagnosis). In Australia, all pathology companies, hospitals, radiotherapy centres, day therapy centres, and the registrar of births, deaths and marriages are legally required to notify all cancer cases to the cancer registry in their state. So this is an excellent way of obtaining information about all cases of prostate cancer. It is what we call “population data” as distinct from data obtained from a particular hospital, set of hospitals or individual doctor. The latter are not generally publicly available, and even if such data are available, they may be biased if not all a surgeon’s cases are included in the statistics.

In the NSW study, 3195 men were identified as eligible to take part in the study. The 245 doctors treating these men were approached to grant permission for the men to be contacted by the researchers. Eight doctors refused to allow any of their 366 patients to be contacted, and many doctors also declined permission for particular patients to be contacted. Of the 2658 men whose doctors gave permission for contact, 2031 agreed to participate in the study, representing 76.4% of those who were invited. 80

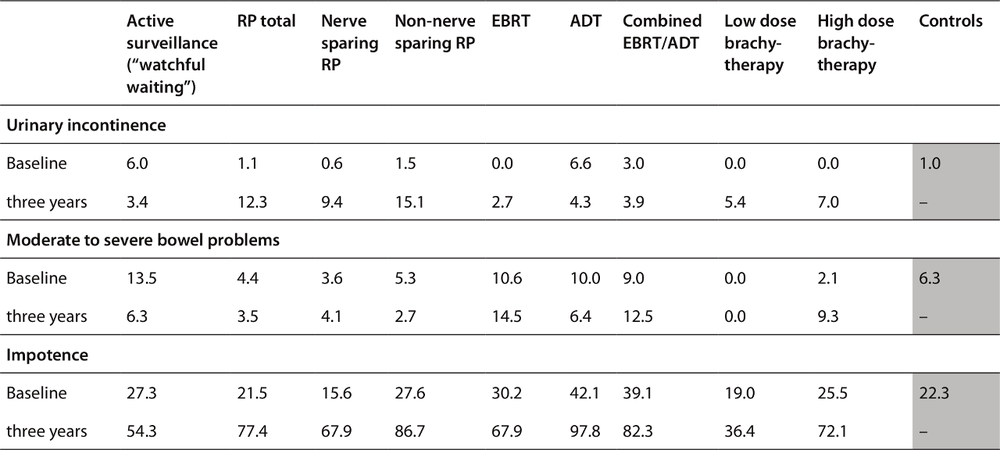

Table 9: Prevalence of urinary incontinence, bowel problems and sexual impotence, three years after treatment and in untreated controls (percentages). EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy.

Source: [102]

81A control group was randomly selected from the electoral roll to enable comparisons with the prevalence of incontinence and impotence problems in men in the community of the same age profile who had not had prostate cancer treatment. The table below summarises the prevalence of sexual and continence problems in the men at follow-up three years later, showing comparisons between the rates experienced by those who had different treatments and the control group, who had had no prostate cancer in that time.

Death

As with many surgical operations, the risk of death from prostate cancer surgery is small but real. The risk is about 0.5% or one in 200 [88, 89]. This risk would be influenced by the older age of many men undergoing surgery. Advanced age is an important independent risk factor for surgical death. A US study of the patient records of 11,522 men who underwent prostatectomy between 1992 and 1996 found that “neither hospital volume nor surgeon volume [i.e. the number of patients the hospital/surgeon has operated on] was significantly associated with surgery-related death” [90]. So if your surgeon ever tries to reassure you about his or her vast experience in performing prostatectomies, or assures you that the hospital where the operation is to be carried out does a high volume of these operations, you should know that the evidence suggests that when it comes to death in the operating theatre as an adverse outcome, these volumes appear to be unrelated to the chance of death being reduced.

Urinary incontinence

The Cochrane Collaboration is an international project designed to synthesise high quality research evidence from all over the world. A Cochrane review allows people to assess the “take-home” messages derived from considering a large number of well-conducted studies, instead of just relying on individual studies, which can differ greatly 82in what they find. If your surgeon or doctor offers you reassurance about the improbability of incontinence or sexual problems, it would be very wise for you to take note of what the results of all studies combined show, and if there is a large difference between what you are told and what the combined research results show, then you would be wise to be circumspect and ask more questions. The Cochrane Library’s 2007 updated review of post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence summarised the data on the prevalence of this problem as follows:

It is not uncommon for men to be incontinent after prostatectomy. The reported frequency varies depending on the type of surgery and surgical technique, the definition and quantification of incontinence, the timing of the evaluation relative to the surgery, and who evaluates the presence or absence of incontinence (physician or patient). Reported prevalence rates of urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer vary from 5% to over 60%. For example, in one study at three months after radical prostatectomy, 51% were subjectively wet (self-report) but 36% were wet on pad testing (objective). By 12 months, 20% were subjectively still wet, but only 16% were classed as wet using objective criteria. After transurethral resection for benign prostate disease, urinary incontinence is less common at three months after operation (eg 10% needing to wear pads), but longer term data are not available. After both types of operation, the problem tends to improve with time: it declines and plateaus within one to two years postoperatively. However, some men are left with incontinence that persists for years afterwards.[91]

Table 9 showed that in NSW, compared to the control group, men who had been treated for prostate cancer, regardless of the type of 83treatment, had higher rates of urinary incontinence three years later. Twelve per cent of men who had had a radical prostatectomy were experiencing urinary incontinence three years later, while rates were lower in those who received various forms of radiation.

According to an August 2008 review by the US Preventive Services Taskforce [92], one year after surgically removing the prostate gland, 15–50% of men have persisting urinary problems. Given that prostate cancer would not have harmed many of these men – i.e., they would have later died from other causes with prostate cancer, but not from it – then this widespread burden of unnecessary surgical side effects is a major downside of the whole push to have men screened [93].

Bowel problems

In the 2009 NSW study which examined men three years after diagnosis and treatment, bowel problems were defined in terms of response to the question, “Overall, how big a problem have your bowel habits been?” with either “moderate” or “big” counting as meaning that the person had a bowel problem. Three years after the treatment, bowel function was consistently worse for all treated men than for men in the control group, but the effect was greatest among men treated with radiation therapy (especially external beam radiation therapy). Table 9 shows that the percentage of men bothered by bowel problems was higher (about double) among men treated with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) compared to controls.

Sexual impotence

According to the 2008 review by the US Preventive Services Taskforce [92], one year after surgically removing the prostate gland, 20–70% of men have reduced erectile function. As we said above in the case of urinary incontinence, given that prostate cancer would not have harmed many of these men, these widespread side 84effects of unnecessary surgical treatment are a major weakness of the campaign to have men screened.

Can side effects be reduced if a man is treated by an experienced specialist?

There is evidence that the risk of the side effects (but not risk of death from surgery, see above) of prostatectomy are somewhat lower if the surgery is performed in an institution in which more such operations are performed and by a surgeon who does relatively more operations [90]. The problem here is that consumers are unable to easily find out this information, beyond the assurances that they might be given by their doctor. It is doubtful that many doctors would have access to data on how a given hospital compared to another.

What is the “da Vinci” robotic surgery machine?

The da Vinci robotic surgery machine, used sometimes in prostate cancer surgery, is manufactured by US company, Intuitive Surgical. Like other laparoscopic approaches, it allows a surgeon to perform a prostatectomy through a small incision rather than via the traditional “open surgery” approach. In addition, instead of directly manipulating the instruments, a surgeon using a da Vinci machine sits at a computer console and directs the machine to perform the surgery. The machines cost about $3.5m to buy and $300,000 a year to maintain [94]. Depending on the surgeon and institution involved, robotic surgery prostatectomy can cost in the vicinity of $14,000, which is currently not covered by private health insurance (although the operation could attract the standard Medicare rebate for a radical prostatectomy, which is a small proportion of the cost). In 2006/2007, the average cost for hospital and medical services for a da Vinci prostatectomy was $14,274, of which Medicare pays $2396 (see healthtopics.hcf.com.au/Prostatectomy.aspx). 85

What is the state of the evidence that robotic surgery is associated with better outcomes for patients? As we will see below, there is currently poor evidence that robotic surgery is demonstrably better.

Even if it were true that robotic assisted surgery was demonstrably better for men than regular surgery, these machines are not widely available in Australia, and because of the costs involved, they will be therefore difficult for some men to access or afford. As of 9 August 2010, the da Vinci website shows there to be just eight da Vinci machines in Australia (three in Victoria at Epworth Eastern and Epworth Richmond private hospitals and one at the Peter McCallum Cancer Centre); two in Brisbane (Greenslopes Private Hospital and Royal Brisbane); and one each in Perth (St John of God, Subiaco); Sydney (St Vincent’s Private); and Adelaide (Royal Adelaide Hospital). According to a prostate cancer support group website [95], there are just 26 doctors trained in using da Vinci machines in Australia (12 in Melbourne, six in Brisbane, three in Adelaide, three in Sydney and two in Perth).

With the costs involved in the acquisition and maintenance of the machines, there are obvious incentives for those who have invested so heavily in them to promote their use. In May 2006, one Sydney surgeon using the machine made what today can be seen as an astonishingly heroic prediction “I’m convinced that in five years time all prostate operations will be done robotically” [96]. Three years after that prediction, an unknown but certainly a small proportion of men who have had a prostatectomy, have had it done with robotic assistance.

One thing we do know is that the numbers of radical prostatectomies being performed in Australia are rapidly increasing. According to Medicare claims data, the number of radical prostatectomies per year increased approximately fivefold between 1999 and 2009. In 1999, there were 1142 claims for the operation under Medicare 86(Item numbers 37210 and 37211) and in 2009 there were 6470. These data are based on services that qualify for a Medicare benefit and for which a claim was processed by Medicare Australia. They do not include services provided by hospital doctors to public patients in public hospital, or services that qualify for a benefit under the Department of Veterans’ Affairs National Treatment Account. Medicare statistics are publicly available at www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.shtml.

Does robotic-assisted surgery produce less adverse outcomes?

The da Vinci corporate website states “studies have shown ‘most patients’ have a rapid return of sexual function and urinary continence” [97]. “Most” could of course mean as low as 51%. Australian urologists using the machine also allude to better surgical outcomes in their website advertising. Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital’s Dr Raji Kooner’s website states: “For the patient, da Vinci Prostatectomy may result in more complete eradication of cancer, retention of bladder control and potency” [98]. The Australian Institute for Robotic Surgery website states:

Robotic-assisted minimally invasive surgery represents an extraordinary technological advance for a broad range of procedures traditionally requiring open surgery. By enabling surgeons to perform complex operations through small incisions, it diminishes the level of patient trauma and helps dramatically improve patient outcomes. [99]

And another: “The potential for an improved and more accurate nerve sparing procedure and preservation of continence”. Melbourne’s Professor Tony Costello is one of Australia’s highest profile prostate surgeons. His personal website (www.tonycostello.com.au/benefits/default.asp?source=cmailer) states that the benefits 87of robotic surgery “may include reduced risk of incontinence and impotence”. But then again, they may not.

It is important to note the highly qualified language in these statements (“more complete” [than what?], “may result”, “the potential for”). So what is the evidence that robotic assisted surgery produces less adverse outcomes? In October 2009, the prostate cancer debate took yet another interesting turn with a major study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) [100] throwing a spanner in the works of those who try to play down the extent of adverse outcomes from prostate surgery.

The JAMA study of 1938 men followed for five years reported that, compared to routine “retropubic” radical prostatectomy, minimally invasive prostatectomy performed via robotic surgery “was associated with an increased risk of genitourinary complications (4.7% versus 2.1%) and diagnoses of incontinence (15.9% versus 12.2%) and erectile dysfunction (26.8 versus 19.2 per 100 person-years)”.

In other words, robotic nerve-sparing surgery being promoted by the handful of surgeons who have invested heavily in it actually appears to make things worse. Doctors outlaying such investments plainly have a massive incentive to keep up a healthy throughput of patients using the equipment and one of the ways of doing this is to promote the advantages of better surgical outcomes to their patients.

Dr Phillip Stricker set up the robotic surgery program at Sydney’s St Vincent’s Hospital. Following the release of the JAMA study, in an October 2009 issue of the online medical newsletter 6 Minutes, he stated that he had performed more robotic prostatectomies than anyone else in NSW, and argued that the JAMA results reflected inexperience in the use of the technology, stating that: “it takes time, experience and technique to achieve equal oncological and potency 88results” and “many of the surgeons who adopt this perform few surgeries and therefore never get off their learning curve”.

So what are Australian men to make of such a statement? Dr Stricker seems to be implying that the outcomes in Australia, particularly those obtained by very experienced surgeons like himself, would be different to the results found in the US study.

In fact, Dr Stricker was an author on a very recent paper which compared the results of 502 retropubic radical prostatectomies (RRP) with the results of 212 robot-assisted laproscopic radical prostatectomies (RALP) performed by him between 2006 and the end of 2008 [101]. Stricker and his co-authors reported that when it came to urinary incontinence, it took 200 RALP operations “to achieve equivalent early continence rates to RRP”. In other words, it wasn’t until Dr Stricker (who had performed more than 2000 RRPs) had performed 200 RALP operations, that the incontinence rates he was achieving were equivalent to those obtained by the RRP approach.

And what about impotency rates? Interestingly, no results were reported. The paper states

One of the limitations of this study is the short follow-up of 11.2 and 17.2 months for RALP and RRP, respectively. As a result we have not reported any long-term continence outcomes or erectile function in the present study.

With the NSW-wide data showing two thirds of all men undergoing nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy being impotent at three years [102], it is reasonable to assume that one-year rates of impotency will be substantial.