1

INTRODUCTION

The Hyde Park Barracks is a landmark building of early colonial Sydney. Best known for its fine Georgian architecture and its association with convicts, the Barracks has a complex history of occupation and modification, and a rich archaeological legacy. It is the Barracks’ archaeological collection that is the focus of this book. When the last convicts were removed in 1848, the building entered a new phase, becoming, among other things, an Immigration Depot for young female migrants arriving from the United Kingdom, and from 1862, an Asylum for infirm and destitute women. These two groups of women occupied the Barracks until 1886, and over the years they lost, discarded and sometimes concealed large quantities of debris and personal items in subfloor cavities. This material includes an extensive array of sewing equipment, clothing pieces, religious items, medicinal bottles, and literally thousands of textile offcuts and paper scraps, along with numerous other objects. These artefacts provide a unique opportunity to explore the lives of these women and their place in Australian society.

The assemblage recovered from the Hyde Park Barracks is significant as one of the largest, most comprehensive and best preserved archaeological assemblages derived from any 19th-century institution anywhere in the world. The bulk of the collection was excavated in 1980 and 1981, with around 70% coming from underfloor spaces of the main building and dating to the Depot and Asylum period (1848–1886). The collection has the capacity to tell us much about the history of women in the 19th century, specifically in relation to destitute asylums and their English counterparts — the workhouse — and, to a lesser extent, the experience of female immigration in the mid-19th century.

The collection has been the focus of dozens of archaeological studies since its recovery three decades ago, but many of these have struggled to come to terms with the size, complexity and meanings of the material. In 2001 the underfloor collection became the focus of a detailed archaeological assessment as part of the Exploring the Archaeology of the Modern City (EAMC) project, a joint investigation between the Historic Houses Trust (HHT) of New South Wales, the Archaeology Program at La Trobe University and the Australian Research Council (Crook et al. 2003). This work identified the great potential of the collection, and an adjunct project was launched in partnership with the Historic Houses Trust to expand and upgrade the original artefact catalogues. The result was the first substantive monograph on the Barracks to describe the archaeology of the underfloor collection and place it within the context of archaeologies of the 19th century, institutionalisation, consumption and migration (Crook and Murray 2006). In 2008 Davies and Murray began further work to complete the re-cataloguing and contextual analysis of artefacts, and create a consistent database for the underfloor collection.

Our aim in this book is to build on Crook and Murray’s previous work and to present a detailed account of the archaeological material and its many meanings within the context of an archaeology of refuge. The unusual nature of the assemblage, however, requires a novel approach, with large quantities of items rarely encountered in conventional archaeological contexts here taking centre stage. For this reason our approach is a holistic one, integrating empirical data about the artefacts with interpretations of spatial context and historical evidence about the Barracks complex and its various occupants. Our focus is primarily on the underfloor collection, that is, material recovered from subfloor cavities on Levels 2 and 3 of the main building, for what it reveals about the lives, relationships and experiences of institutional women in 19th-century Sydney.

THE HYDE PARK BARRACKS: A BRIEF HISTORY

The Hyde Park Barracks was built under instruction from Governor Lachlan Macquarie between 1817 and 1819 to provide secure accommodation for male government-assigned convicts who, until that time, roamed Sydney’s streets after their day’s work and were responsible for their own lodgings.1 Macquarie

2believed that the convicts had too much free time, which they abused in robbery and drunkenness. He wanted convicts on government service subject to tighter discipline and easier mustering, so more work could be obtained from them. His response was to create a large barracks where the men would be confined every night during the week, but allowed to work on their own account on weekends (Hirst 1983:41–44).

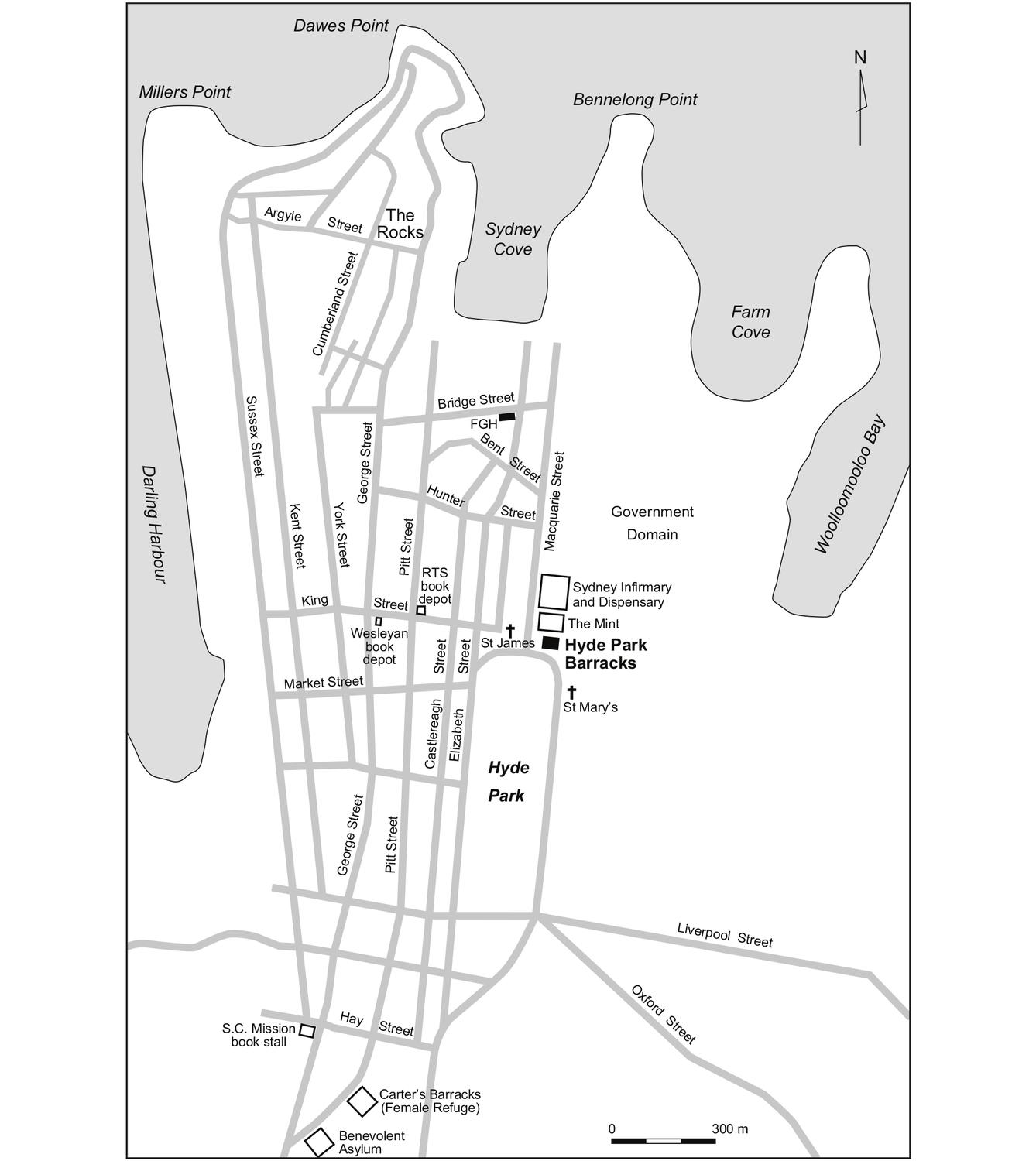

Figure 1.1: Plan of Hyde Park Barracks, adapted from Freycinet’s 1819 plan (Historic Houses Trust 2003:5), Commissioner Bigge’s 1822 plan (in Baker 1965:16), and S. L. Harris’ 1824 plan (in Baker 1965:30).

The Barracks complex was constructed by skilled convict labour to a design specified by the convict architect, Francis Greenway (Figure 1.1). In Greenway’s original Georgian design, the compound comprised a central dormitory building, enclosed by perimeter walls with corner pavilions that contained both cells and guard houses. Two ranges of additional buildings flanked the northern and southern perimeter walls, comprising a kitchen, bakery and mess, in addition to residential quarters for the Deputy Superintendent and his family. Open sheds were later built against the eastern and western compound walls to provide additional shelter. As a reward for services, Francis Greenway’s conditional pardon was made absolute.

The Barracks was intended to house 600 convicts, but up to 1400 may have been accommodated there in later years (Cozens 1848). With more than 9000 male convicts in the colony by 1819, however, only a fraction were held at Hyde Park (Shaw 1966:96). In the wards they slept in hammocks slung from wooden rails and beams. The work day extended more or less from dawn to dusk, with an hour’s break for lunch. Supervision within the wards was minimal, and thieving, gambling and nocturnal escapes were reported as chronic problems (Ritchie 1971:17; Select Committee 1844).

The Hyde Park Barracks was built to provide accommodation for convicts, not as a prison. In Britain, during the later 18th and early 19th centuries, there was significant debate about crime, laws, punishment and gaols. Penal reformers such as John Howard and Jeremy Bentham promoted a new regime of punishment, directed not at the physical chastisement of the criminal, but at reforming ‘the heart, the thoughts, the will, the inclinations’ of the prisoner (Foucault 1977:16). The new way to discourage criminal behaviour was through punishment by confinement in prison, rather than by the infliction of bodily pain. The British government responded by building two new prisons, one at Millbank, which opened in 1816, and Pentonville, which opened in 1842, while continuing with the use of hulks as floating prisons, and transportation (Brodie et al. 2002:60, 94; Ignatieff 1978:93–95).

While convict transportation to Australia continued throughout this period of shifting ideas about the punishment and reform of criminals, the 3Hyde Park Barracks, however, was constructed with little apparent awareness of these changing penal philosophies. There were no facilities to separate or isolate convicts, for example, and internal surveillance and control were also limited. Architectural historian James Semple Kerr argues that Greenway’s barracks adapted a form used in the 18th century for a variety of domestic, agricultural and urban buildings and institutions (Kerr 1988:24). He also suggests that the composition and style of the Barracks was meant to embellish the urban environment, and that its function as a place of confinement was incidental (Kerr 1988:40). J. M. Freeland (1968:40) writes that the Hyde Park Barracks was ‘just a barn — but a very handsome barn’.

Figure 1.2: Location of Hyde Park Barracks in relation to Sydney streets and landmarks.

Although the Hyde Park Barracks did not, and could not, function effectively as a prison, increasingly, in the 1830s and 1840s, it was used as a place of secondary punishment for refractory prisoners. Governor George Gipps observed in 1844 that the convicts in the Barracks ‘are for the most part those, who in consequence of their misbehaviour have failed to receive indulgences … 4they are in fact the refuse of the Convict system in New South Wales’ (Gipps 1925[1844]:84). Well-behaved convicts continued to be rewarded with permission to live outside the Barracks, on their path to a ticket-of-leave (or conditional pardon), leaving the complex increasingly as an option for the punishment of secondary offenders.

The Court of General Sessions was established in the northern range of the Barracks complex in 1830, beginning a long occupation of the complex by the colonial courts. Magistrates dealt mostly with offences against the labour code (which mostly applied to convicts), including drunkenness, disobedience, neglect of work, absconding and insolence. Physical punishment for convict misdemeanours increased in severity during this period. The range of penalties magistrates could impose comprised flogging, or work in irons on road gangs, to fines, extensions of sentence, or being sent to Norfolk Island (Molesworth 1967 [1838]:24–25). A convict was appointed as an official scourger at the Barracks in 1822. The flogging triangle ‘squatted obscenely’ in the south-east corner of the Barracks yard, with flogging carried out in the presence of all the convicts, with 25–50 lashes being the norm.

Following the end of convict transportation to New South Wales in 1840, the continued presence of convicts in the Hyde Park Barracks became an embarrassing anomaly in the heart of Sydney (Figure 1.2). Surrounded by public buildings and churches, offices and businesses, the hundreds of convicts marching in and out were a daily reminder of the colony’s convict origins. There were around 800 convicts occupying the Barracks at this time, many transported to the colony from Great Britain, and others, expiree convicts from Norfolk Island completing the residue of their sentence. Much of the public antagonism towards convicts was due to the fact that while transportation to New South Wales had ceased, the NSW government was still required to spend large sums accommodating the convicts, and to pay for a substantial police and court system to prosecute the crimes they committed. There was public resentment at the ongoing cost of paying for the ‘criminal outcasts’ of Great Britain, when colonial society was trying to leave the dark stain of convictism behind.

In 1848 the remaining 19 convicts still living at the Hyde Park Barracks were moved to Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour, and the main Barracks building was refitted to accommodate orphans and a new kind of mobile workforce: the single, female migrant:

The building known as Hyde Park Barracks having survived the system of supplying this colony with Labour, to which it so long ministered, has been appropriated as a place in which the [Irish] Orphan Immigrants will be lodged until provided their places. Situated at the corner of Hyde Park [it] is an open place, which, though in immediate proximity to the business thoroughfares of Sydney, is not one itself, with the Government Domain behind it stretching to the Waters of Harbour, and an uninterrupted view to the Heads of Port Jackson, surrounded by a spacious yard enclosed by high walls, and close to the principal Church of England and Roman Catholic churches, and to the residences of the clergymen who officiate there, this building appears to possess every advantage that could be desired, with reference to the health, the seclusion and the moral and religious instruction of the inmates, and the convenience of persons coming to hire them. It consists of three stories, divided into large airy wards, and affords convenient accommodation for about 300 persons. The females are under the immediate superintendence of an experienced resident matron, who was appointed by the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners to the charge of the children who arrived last year in the “Sir Edward Parry”, and where efficiency in that situation caused her appointment to the office which she now fills. (Annual Report of Immigration in NSW 1848, page 5, SRNSW 4/4708 in HPB Research Folder: ‘AONSW Immigration and Government Asylum Records’)

The offices of the Agent for Immigration and the hiring rooms of the Female Immigration Depot were located on the ground floor, with temporary accommodation for new arrivals transferred from the Quarantine Station at North Head in Sydney Harbour provided on Levels 2 and 3. From 1849 to 1855 the Immigration Depot also accommodated the wives and children of convicts brought out to the colony at government expense to be reunited with their husbands and fathers (McIntyre 2011:25). Convicts had petitioned authorities to have their families sent out from Britain since at least the 1830s (Hirst 1983:129). The poor families of Irish emancipists dominated the scheme, with around 85 per cent of the almost one thousand family members sent out coming from Ireland (Berry 2005a).

The arrival of young female immigrants was part of the much wider movement of people during the 19th century from Britain to far-flung parts of the Empire. Governments sought to attract the labour they needed through assisted fares and cheap passages. Single women were in high demand as domestic servants, with the expectation that in time they would also become the wives and mothers of colonial Australians (Chilton 2007; Gothard 2001; Hammerton 1979; Rushen 2003).

In addition to the Female Immigration Depot and Immigration Office, the Hyde Park Barracks briefly accommodated several thousand Irish female orphans between 1848 and 1852 (McClaughlin 51991). Other government agencies resident in the northern and southern parts of the complex included the Government Printing Office (1848–1856), the Vaccine Institute (1857–1886), the NSW Volunteer Rifle Corps (1861–1870), the City Coroner (1862–1907), the Sydney District Court (1858–1978) and the Court of Requests (1856–1859). Cases in the District Court mostly involved the recovery of small amounts of money, property disputes, defamation, and breaches of contract, providing much work for barristers and solicitors filing in and out of the Hyde Park Barracks compound (Holt 1976:59).

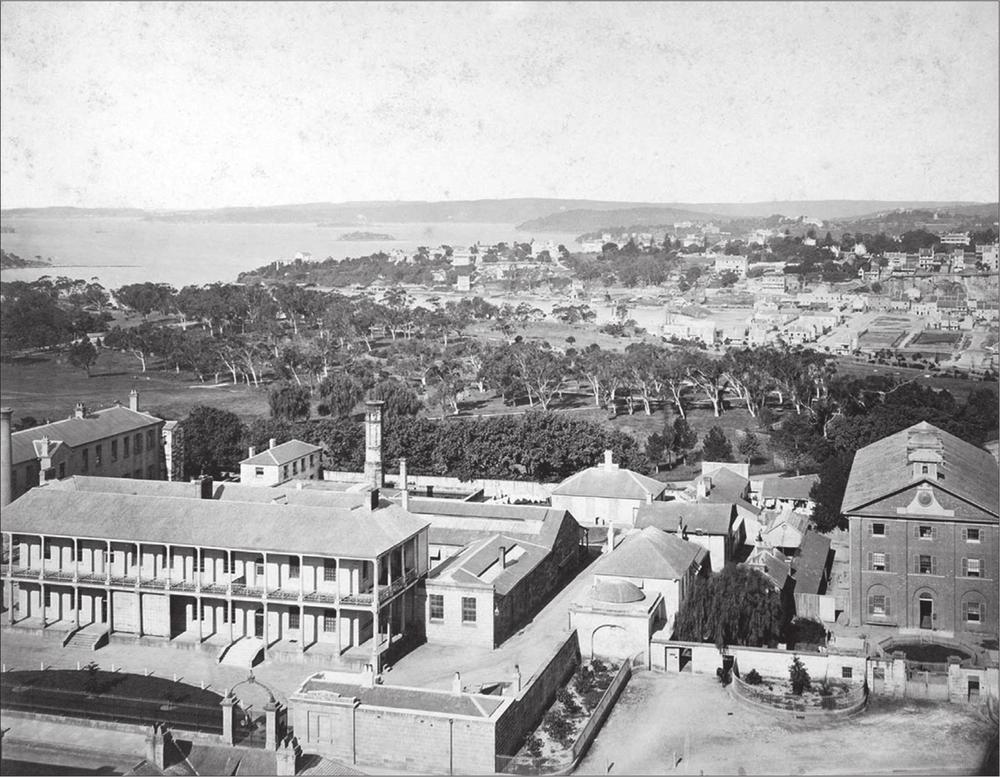

Figure 1.3: View of the Royal Mint and Hyde Park Barracks taken from the steeple of St James’ Church c.1871, with The Domain, Woolloomooloo and Potts Point in the distance (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, SPF/322).

In 1862, the top floor of the main building was given over for the use of the Government Asylum for Infirm and Destitute Women, following the colonial government’s assumption of responsibility for the care of the aged and infirm. Over 150 women were transferred from the overcrowded Benevolent Asylum at the south end of Pitt Street. Transported in horse-drawn omnibuses, 101 women arrived on 15 February, 36 women on 1 March and 14 more women on 13 March (Hughes 2004:58). Matron of the Immigration Depot and from February 1862, of the Asylum, Lucy Applewhaite (later Hicks) also lived at the Hyde Park Barracks along with her husband John Applewhaite, Master of the Asylum, and their family. The presence of the Asylum for the care of aged and infirm women placed many demands on the old convict barracks, and many modifications were required over the next two decades (Figure 1.3).

Overcrowding was an ongoing problem, with almost 300 inmates at the Asylum by the 1880s. In 1886 the women were moved to a new purpose-built facility at Newington on the Parramatta River, and the Immigration Depot was relocated.

Thus began the third major phase of the Hyde Park Barracks’ history: the judicial period. At this time, the area became known as Chancery Square, and buildings within the Hyde Park Barracks complex were extensively remodelled for use by the Department of Attorney General and Justice. Level 1 of the main building was occupied by the Land Evaluation Office, a small court, and judges’, jury and witness rooms. The Clerk of the Peace and rooms of the Industrial Court took up much of Level 2, while the Master in Lunacy took over Level 3 with his clerks, reporters and records (Lucas 1990:25; Street et al. 1993). Two large courtrooms (Equity and Bankruptcy) were attached to the eastern end of the main building after the 1860s verandah was removed. Internal partitions were installed in the main building to divide up the large rooms into smaller spaces, while a number of doors were cut through the central corridor to provide access to 6these new offices (Davies 1990:8; Varman 1981:37). Around this time there was a proposal to replace the Barracks with a new building to house a public library. The Colonial Architect, James Barnet, sketched designs based on the style of the British Museum, but nothing further came of it (Chanin 2011:14).

By the turn of the century the entire complex was renamed Queen’s Square, and comprised the main building and a jumble of makeshift structures that filled the courtyard. Government offices located at the complex at that time included the Metropolitan District Court, Coroners Court and Equity Court, the Master in Lunacy, the Clerk of Peace Office, the Registrar of Probates and the Estates Office. In the following decades numerous additions and alterations were made to the buildings, and there was a suggestion in 1935 to convert the central building into a museum (Thorp 1980:9:1). In 1946 a report recommended that the building be demolished (Baker 1965:42). The complex continued, however, to be used primarily for judicial purposes until 1979.

In 1975, under the auspices of the Public Works Department, restoration of the Hyde Park Barracks buildings began while still being occupied by the Department of Attorney General and Justice, and ancillary police departments. The Barracks was placed on the Register of the National Estate in 1978, and three years later was granted one of Australia’s first Permanent Conservation Orders (PCO) under the New South Wales Heritage Act 1977.

In 1980 the NSW government announced that the Hyde Park Barracks would be converted to a museum of Sydney’s history and that the physical fabric of the building complex would be restored to its original convict phase. When restoration work began, artefacts were revealed in the underfloor spaces of the central dormitory building as well as in service trenches within the grounds of the compound. Following test trenching, the Public Works Department embarked on Sydney’s first large-scale public excavation, which attracted media attention and was assisted by the work of many volunteers.

The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS) opened the Hyde Park Barracks to the public in 1984, as the first museum of its kind to focus on the history of Sydney. In 1990, the Barracks was transferred to the Historic Houses Trust (HHT), and after refurbishment, was reopened as a ‘museum of itself’ with permanent displays on the second and third floors and temporary exhibitions in the Greenway Gallery on the first floor. By 2001 the Parole Courts, which had occupied the north-eastern perimeter structures of the Barracks, became the final portion of the complex to come under the management of the HHT.

In 2008, the Commonwealth Government included the Hyde Park Barracks as part of a serial listing of eleven convict places for World Heritage nomination (Australian Government 2008). The UNESCO World Heritage Committee accepted the listing in July 2010. The Trust’s Hyde Park Barracks Museum continues to operate successfully today as a museum depicting its own history, especially its convict phase.

ARCHITECTURE OF THE HYDE PARK BARRACKS

Governor Macquarie formally reserved the area of Hyde Park in 1810, an area known as the Cricket Ground or the Racecourse, renaming the area in tribute to its far grander namesake in London. In 1816 he initiated construction of the Hyde Park Barracks without approval from the Home Office, later telling Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for the Colonies, that it would be ‘productive of many Good Consequences, as to the personal Comfort and Improvement of the Morals of the Male Convicts, in the immediate Service of Government at Sydney’ (Macquarie 1925 [1817]:720). Ground was marked out for the building in November 1816, and work by skilled convict labour began in March 1817. On 20 May 1819 the first batch of 130 convicts moved in, a precursor to the official opening on 4 June 1819, when 589 convicts sat down to a special meal to mark the occasion. Macquarie enjoyed the spectacle of so many felons treated to an abundance of ‘good beef and bread, plum pudding and punch’, followed by official speeches (Broadbent and Hughes 1997:56; Ellis 1973:116).

Francis Greenway’s simple, elegant design was a familiar 18th-century arrangement, with a dominant central building set in a rectangular walled compound and aligned on an east-west axis (Kerr 1984:39). Commissioner Bigge described the internal fittings of the Barracks in detail:

… the principal barrack … is a handsome brick structure 130 ft in length and 50 ft in breadth, and contains 3 stories, that are divided by a lofty passage, separating one range of sleeping rooms from the other. There are 4 rooms on each floor, and of these 6 are 35 ft by 19 and 6 others are 65 ft by 19. In each room rows of hammocks are slung to strong wooden rails, supported by upright staunchions fixed to the floor and roofs. 20 inches or 2 ft in breadth and 7 ft in length are allowed for each hammock; and the 2 rows are separated from each other by a small passage of 3 ft. 70 men sleep in each of the long rooms and 35 in the small ones. Access to each floor is afforded by 2 staircases, placed in the centre of the building; and the ventilation even in the warmest seasons is well maintained. The doors of the sleeping rooms, and those communicating with the courtyard, are not locked during the night. One wardsman [a convict] is appointed to each room, who is responsible for the conduct of the others … Another dormitory is provided 7in one of the long buildings on the north side of the yard, 80 ft in length by 17, in which the convicts lately arrived, and those returned into barrack by order of the magistrate are lodged. They sleep on the matrasses [sic] that are brought from the convict ships, and spread them upon raised and sloping platforms of wood similar to those used in military guard rooms. The convicts employed in the kitchens and bakehouse are allowed to hang their hammocks there. (Quoted in Kerr 1984:40–41)

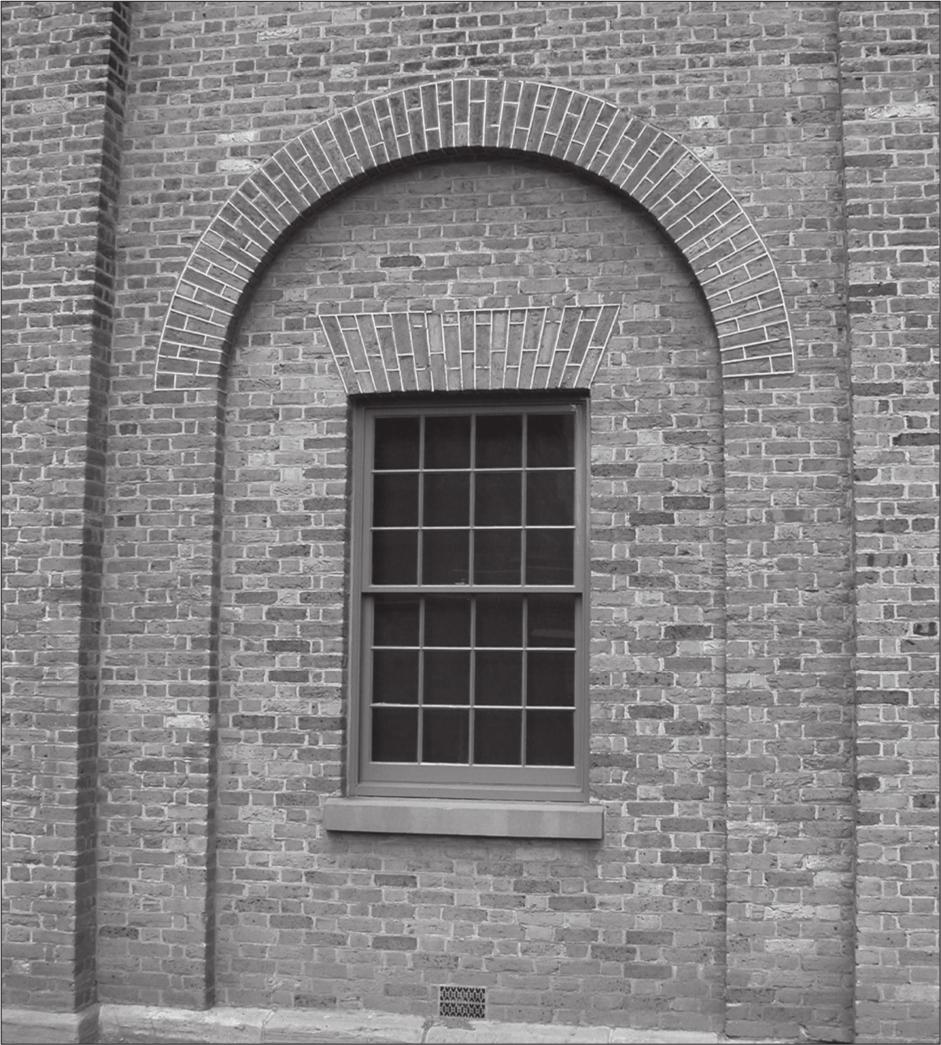

Figure 1.4: General view of Hyde Park Barracks main building (P. Davies 2008).

Greenway used soft red sandstock bricks set in lime mortar for the main building, and stone for the compound walls and gate piers (Figure 1.4). The base course and string courses were of sandstone. Pilasters in the main building served as load-bearing elements for the large floor beams and ceiling members, while the low hipped roof was covered in wooden shingles. A domed ventilator was placed in the centre of the roof, with a bell suspended from the centre. A clock was placed in the pediment over the main entrance, below which was inscribed:

L MACQUARIE ESQ GOVERNOR 1817

Figure 1.5: Detail of Level 1 window (P. Davies 2008).

Large glass windows were set in each of the three levels. These included rectangular windows set in semi-circular arched niches on the first level, rectangular windows in the second level, and square windows on the third level (Figure 1.5). Window glass was expensive in the early 19th century due to stiff British excise laws, and 8technical limitations on the production of Crown glass meant that panes were generally less than 16 inches (400 mm) in size (Boow 1991:100–101). The generous use of glass in the Barracks provided a practical way of admitting natural light into the interior of the large building, and may also have been a subtle statement by Macquarie and Greenway about the kind of settlement and society they wanted to build.

The perimeter wall of the Barracks compound was only 10½ feet high and, over the years, proved little obstacle for convicts wanting to escape. Its elevation may have been determined in part by Greenway’s reluctance to obscure views of his building.

The buildings ranged along the northern wall included a prominent central building, connected on either side to a long, low single storey wing, each terminating in a small square pavilion containing five small punishment cells, 7 ft by 4 ft, for the solitary confinement of refractory convicts. The buildings ranged along the southern wall included two long mess rooms, each 100 ft in length, with the large kitchen in between. Privies were built adjacent to the eastern wall of the compound, while wash houses and a drying shed were later constructed nearby. On the east side of the Barracks a brick wall enclosed a four acre garden, cleared and stumped by the convicts, with a gardener’s lodge in the centre (Thorpe 1980:2.2). At the main western entrance there were two square lodges used by a clerk and a constable overseeing the movement of convicts.

Responses to the construction varied. A detailed and positive account, probably written by Greenway himself, appeared in the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser for 17 July 1819. The building was described as ‘a noble structure of admired architecture … The aspect of the building is beautiful at a distance, but at a near approach conveys an idea of towering grandeur.’ Others objected, however, that its function was subordinated to its form. Commissioner Bigge, for example, acknowledged that the style was ‘simple and handsome’, but complained that the external walls were too low. He was concerned that the need for security had been sacrificed to the building’s ornamentation.

Joseph Fowles was the last person to describe the building as a convict barracks, in 1848. He referred to ‘the pile of building called Hyde Park Barracks’, and argued that ‘none of these edifices have much architectural pretension, being constructed entirely of brick and devoid of ornament, yet, the proportions being good, the masses broad, and the lines bold and unbroken, they form an imposing and dignified whole’ (Fowles 1962 [1848]:28). He also acknowledged that the Barracks was ‘very well adapted for the purpose for which it was designed’ (Fowles 1962 [1848]:81).

Modifications and Renovations

A range of modifications and repairs were made to the Hyde Park Barracks over the years. In 1821, for example, only two years after its opening, the entire roof of the main building was re-shingled, because the initial selection and laying of [Casuarina] shingles had been inadequate (Thorp 1980:2.2). ‘Squint’ or spy holes were made in the walls of the dormitories on the second and third levels, to permit the wardsmen to keep a closer watch on the inmates. In 1824 it was reported that the water closets were ‘in a most offensive state, for want of Proper Sewers round the Building to carry off the Soil’ (quoted in Baker 1965:30). The perimeter wall was also undergoing repair at this time. During the early 1840s, reticulation pipes were laid from Busby’s Bore to various points in the city, and it is likely that the Barracks was connected for the first time to a permanent water supply (Spiers 1995:50; Thorp 1980:4.2; Varman 1993: phase V). In 1847 the roof was re-shingled again, and the walls were repainted.

The departure of the remaining convicts in 1848 and the arrival of immigrant women necessitated further changes to the fabric and appearance of the building. The hammock rails and supports were removed and replaced with iron-framed beds, which were held in place by ‘bed battens’ nailed to the floor (Varman 1981:13). The battens indicate that beds were arranged in two east-west rows in the dormitory rooms. Lime-washing of ‘walls, ceiling and inside of roof’ was also carried out as a hygienic measure (Thorp 1980:4.2). Four new external water closets were installed, along with a pump to convey water to the second floor. A 260-foot-long stonewall fence, 11 feet high, was also built to separate the Immigration Depot from the Government Printing Office in the north of the compound. Shutters were installed on the windows of the central dormitory building around 1856.

Around 1862 the southern stair was removed, leaving only the northern stair for access to the upper levels. This was done to create extra floor space on all three levels of the main building, with new landings built on Levels 2 and 3. The landings were removed during renovations in the 1980s, and reinterpreted with a ‘ghost’ hand railing.

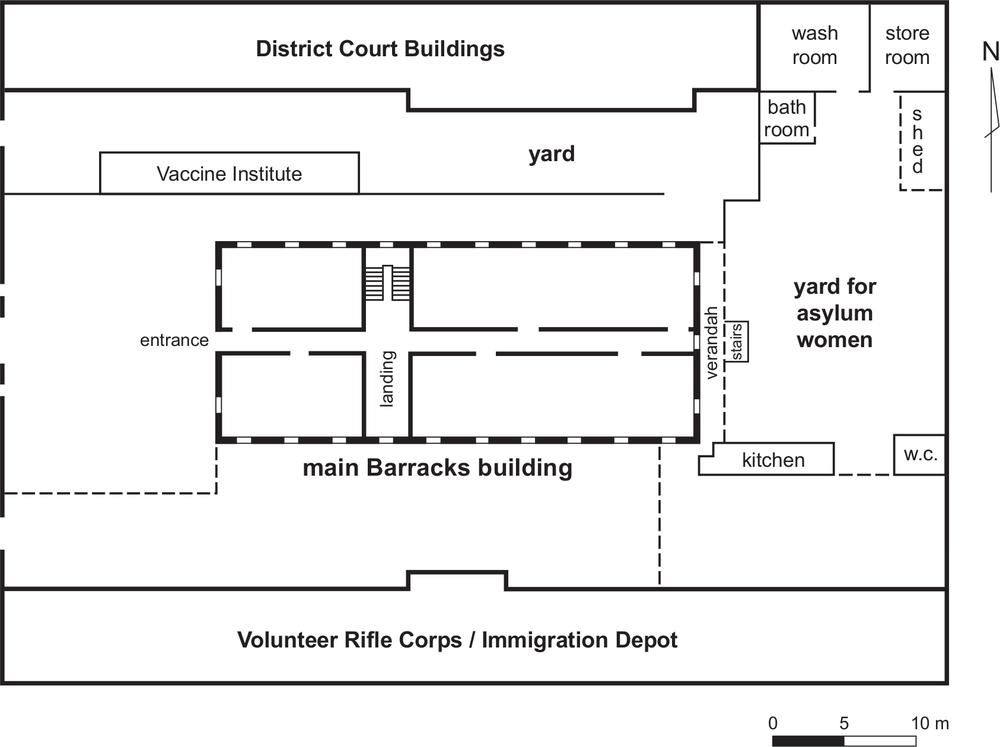

In 1863 a section of yard at the rear of the main building was fenced off for the use of the recently arrived Asylum women (Figure 1.6). A new kitchen was also built at the south-east corner of the Barracks. By 1864 the dining room of the Depot, on the ground floor of the Barracks, had become so overcrowded that a shed was erected by the screening wall between the Depot and law courts (Spiers 1995:63). A balcony and staircase were also built at the eastern end of Level 3, to allow separate access for the aged and infirm women to their yard, privies and washhouse, without having to go through the Immigration Depot. A bell-cot was 9added to the roof of the Barracks in the late 1860s (Thorp 1980:6.2).

Figure 1.6: Simplified plan of Hyde Park Barracks, about 1870 (P. Davies 2011).

Modifications to the internal ceilings at this time were critical for the accumulation of underfloor archaeological deposits. Ceiling boards were introduced in most parts of the building with the arrival of the Immigration Depot in 1848. These were joined by tongue-and-groove fittings, which trapped many small artefacts that fell through the butted floorboards above. These were in turn replaced by lower lying ceiling boards which were installed during renovations at the beginning of the 1886 legal phase. In the few places where no ceiling boards had been installed in 1848 (e.g. the corridors on Levels 1 and 2) the ceiling boards of the legal phase provided the first opportunity for deposit to be accumulated below the floor boards. This change effectively sealed the cavities created by the introduction of ceiling boards in 1848 and the artefact assemblages which had accumulated within them for 38 years.

WRITING ABOUT THE BARRACKS

Although the Hyde Park Barracks is a well-known part of Australia’s convict and colonial heritage, the historiography of the complex is very uneven. References to the building and its various occupants have appeared regularly over the years in books, articles and other publications, along with dozens of consultants’ technical reports (Crook et al. 2003:15–17), however, there is no single comprehensive account of the Barracks and its occupant groups, and the associated archaeological material.

Convictism has been a popular theme in accounts of the Barracks, an emphasis reinforced by the inclusion of the site in 2010 on the World Heritage List as part of a serial nomination of convict places in Australia (Australian Government 2008; see Baker 1965; Bogle 1999; Emmett 1994; Irving and Cahill 2010:21–24; Moorhouse 1999:171–173; Robbins 2005). The museology of the Barracks, as a ‘museum of itself’, has also claimed critical attention (e.g. De Silvey 2006:334; Eggert 2009:31–40; Kelso 1995; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998:168; Lydon 1996; Young 1992). The history and archaeology of the Immigration Depot2 and the Destitute Asylum, however, and the century of civil and judicial administration that followed, are usually ignored in scholarly literature. Stephen Garton (1990), for example, described the government male destitute asylums at Parramatta and Liverpool, but not the

10Hyde Park Asylum for women. Historian Brian Dickey has written extensively about charity and welfare in colonial Australia, with a particular emphasis on New South Wales and South Australia, although much of his work on the former focused on the Benevolent Society of NSW and largely ignored the Hyde Park Asylum (Dickey 1966, 1973, 1976, 1987). Judith Godden’s doctoral thesis on female philanthropy and charity in New South Wales from 1870 to 1900 mentions the Hyde Park Asylum only in passing (Godden 1983:66). The Asylum is also overlooked in many standard historical analyses of poverty in colonial NSW (e.g. Fitzgerald 1987; Kelly 1978; Mayne 1982; O’Brien 1988), while Kingston (1988:51) wrongly claims that only South Australia and Western Australia had state-subsidised benevolent asylums (Hughes 2004:3). A biography of Charles Cowper, the Colonial Secretary primarily responsible for establishing the Hyde Park Asylum, fails to mention this major achievement (Powell 1977). Joy Hughes (2004:1) describes the asylum as ‘invisible’.

This silence may be due in part to the lack of readily accessible primary documents, with almost none of the Hyde Park Asylum’s official records, including admission and discharge registers, ration returns, store books, letter books and other papers, having survived. Unlike its predecessor, the Benevolent Asylum, the Hyde Park institution was largely free of complaint and thus did not attract adverse newspaper attention — notwithstanding some public scrutiny in its later years (Hughes 2004:8). Primary historical material is available, however, scattered through archives from the Colonial Secretary, the Government Architect and the Public Works Department. Hughes’ (2004) MA (Honours) thesis draws on this documentary archive to describe the Hyde Park Asylum in relation to the development of NSW colonial government policy on charity and welfare, placing the Asylum in a historical trajectory between the Sydney Benevolent Asylum and the Newington Asylum. Her work offers a valuable revision to the usual focus on convicts and immigrants, and illuminates in particular the life of Matron Lucy Hicks.3

In addition, two important sources of primary information about the Asylum emerged from official government inquiries. The 1874 Public Charities Commission reported on the workings and management of numerous charity institutions operating in the colony at the time. Matron Hicks gave evidence to the Commission on 24 September, which reveals her at the height of her control and influence. The Report of the Government Asylums Inquiry Board, which sat from August 1886 to March 1887, also casts important retrospective light on the operations at Hyde Park, and reveals a sharp decline in the standards of care. In total, Hicks gave evidence to the Board on nine separate occasions. Annual reports published by the Government Asylums Board, and the Inspector of Public Charities, also provide useful summary information about the costs and operations of the four institutions for the destitute under government control.

1 The first convict barracks in Australia was the Castle Hill Government Farm, built at Baulkham Hills near Parramatta in 1803. Excavation of the site in 2005 revealed the foundations of a large stone building, but little in the way of associated artefacts (Wilson and Douglas 2005). Following the Castle Hill uprising in 1804, when a group of mainly Irish convicts rebelled unsuccessfully against the authorities, no further convict barracks were built until 1817, when construction of the Hyde Park Barracks commenced. Around 1819, the Carters’ Barracks, at the south end of George Street, were also built to lodge convicts, with up to 180 men employed at making and hauling bricks. Two treadmills were installed in the complex by 1824 (Evans 1983:96–97; Hirst 1983:63; Kerr 1984:53; Macquarie 1925 [1822]:686).

2 Several historians have wrongly linked Caroline Chisholm with the Hyde Park Barracks, mistaking the short-lived Immigrants’ Home she established in Bent Street (1841–1842) with the HPB Immigration Depot (e.g. Gothard 2001:167–168; Hamilton 2001:458). Chisholm was in fact in England from 1846–1854, when the Depot at the Barracks was established (Kiddle 1972:80, 182).

3 For convenience, the Matron is referred to by her second and final name, Lucy Hicks, except when making reference to her life and work when she was known as Lucy Applewhaite, prior to 1870 when she married William Hicks.