2

THE UNDERFLOOR ASSEMBLAGE OF THE HYDE PARK BARRACKS

The most outstanding component of the Hyde Park Barracks Archaeology Collection is the underfloor assemblage, concealed for up to 160 years in the cavities below the floors on Levels 2 and 3. The assemblage is significant because its survival in the dry cavity spaces has preserved a wide range of fragile materials such as paper, textiles and other organic products that rarely survive in regular, subsurface archaeological contexts.

In this section we review the history of architectural changes to the Hyde Park Barracks as the context in which the formation and characteristics of its archaeological collection and associated processes of deposition took place (Schiffer 1987:64–69).4

Figure 2.1: Cavity spaces between the joists below the floor on Level 3, looking east. Note the stack of floor boards on the scaffold at left (V. Pavlovic 1982).

ARCHITECTURAL CONTEXT: THE SUBFLOOR CAVITIES

When the Hyde Park Barracks was first constructed as a convict barracks, the floorboards were butted and fixed with machine-cut floor brads, which was typical for the time. Almost none of this original flooring has survived on the ground level, but the majority of boards on the first and second floors are original, although after decades of repairs and refits for various government departments, there were many areas of disturbance. The most affected areas were those around principal beams, near windows and under doorways (Figure 2.1). In other locations, boards were pulled up, buttressed with

12iron stirrups and then re-nailed (Varman 1981:11). Originally the boards ran across the width of the rooms but few had survived to their full length by the late 1970s (Varman 1981:7).

The original floorboards had been pit-sawn by convict workmen, with significant variations in width, thickness and evenness of cut caused by the different saws used, and the strength and skill of individual sawyers (Varman 1981:7). Later floorboards were cut by machine, and tongue-and-groove flooring became available by the 1840s. This means that as flooring was repaired and replaced over the years, a mix of boards was installed over the floor joists. As older timbers dried, shrank and split, gaps opened up between the boards and nails weakened their grip. By the Depot and Asylum years, it is probable that some sections of flooring were loose enough so that the floor boards could be lifted and items could be deposited in the subfloor spaces.

There is no clear evidence of the floor coverings used during the Asylum and Depot era, but it is likely that some areas of the building’s floors were covered, although not for their full length of occupation, as indicated by the large quantities of material deposited beneath the floor. Linoleum was first developed in the 1860s although it did not become ubiquitous until the 1890s (Townrow 1990), so it seems unlikely that this would have been used during the Asylum period. Oral histories revealed that in the 20th century most floor areas were covered with linoleum or carpet, at least on Level 3, and it is likely that the floors were systematically covered with linoleum from 1886 when the law courts moved in.

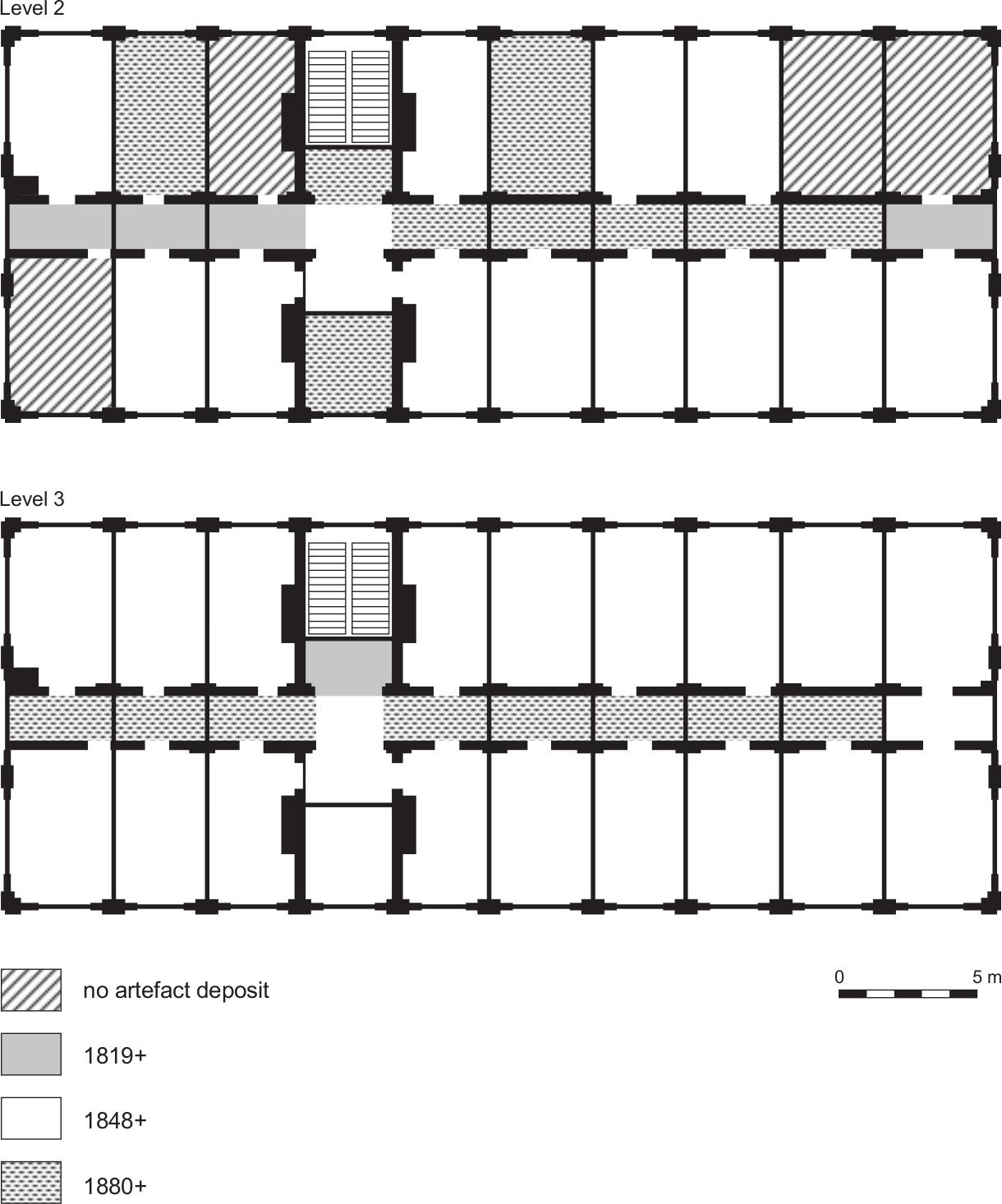

Figure 2.2: Minimum dates for joist groups on Levels 2 and 3 of the main building based on ceiling modifications (after Mider 1996 [1]:9–10; Varman 1981).

The original ceilings of the Hyde Park Barracks were a mix of lath-and-plaster and exposed white-washed beams (Varman 1981:22). Ceiling boards were introduced in most parts of the building with the establishment of the Immigration Depot in 1848 (Potter 1981:48). The floor over the Matron’s quarters on Level 2 was ceiled in 1865 ‘to prevent the inconvenience arising from the leakage which occasionally takes place from the upper rooms’ (quoted in Thorp 1980:6.2). Ceiling boards either sealed the formerly exposed beams or, where lath-and-plaster ceilings had been installed, these were removed and replaced with the new boards. Lath-and-plaster boards survived at the western end of the ground floor hallway and the stair landing on Level 1, with traces recorded in the clock weight case on Level 3 (Varman 1981:22). Large quantities of artefacts were recovered from the subfloor spaces created above these lath-and-plaster remnants (JG59, JG60, JG61 and JG62).

The new ceiling boards were joined by tongue-and-groove fittings which trapped many tiny artefacts that had fallen through the butted floorboards above. These were in turn sealed by lower lying ceiling boards which were installed during the 1886 legal phase renovations and which were removed during the 1979–80 conservation works (Varman 1981:22). In the few places where no ceiling boards had been installed in 1848, such as the corridors on Levels 1 and 2, the ceiling boards of the legal phase provided the first opportunity for deposits to accumulate below the floor boards.

This sequence of floor and ceiling construction and modification has important consequences for the underfloor assemblage (Figure 2.2). Despite the great importance of the convict origins of the Barracks, the underfloor areas that are potentially of convict origin comprise only 3.6% of the floor space on Levels 2 and 3. Those dating to the women’s phase, from 1848, comprise over 71% of the total area, and those dating from the legal phase, 16.2%. In four areas on the ground floor the ceiling boards collapsed during conservation 13works and all the deposit that had accumulated from below the boards on Level 2 was lost. This represented 8.8% of the floor space.

Examined in toto, the Hyde Park Barracks assemblage is a palimpsest deposit, containing a range of materials dating from 1819 up to the mid-20th century, and includes material from the legal phase of office occupation.

PROCESSES OF DEPOSITION: ACCIDENTAL LOSS, RATS AND CONCEALMENT

The underfloor assemblage comprises a range of materials lost, swept or placed beneath the floorboards over a long period of time. The majority of underfloor deposits include an accumulation of small items such as buttons, beads, pins and paper clips that fell through the gaps of the boards when accidentally dropped, or incidentally swept between the cracks, along skirting boards, in fallen-through timber knots or other holes such as old nail shafts. Fragments of larger items, such as glass bottles or ceramic vessels, may also have been lost this way if a vessel shattered when dropped. Many of these items probably fell through the boards unnoticed.

The old and warped butted floorboards on Levels 2 and 3 would have provided ample opportunities to lose small items in this way. Sweeping and cleaning may also have resulted in the deliberate deposition of refuse under the floor. Large quantities of textile fragments and torn paper, for example, which accumulated on the floor under beds and in corners, may have been swept up and pushed below a conveniently loose floorboard.

It is likely that most items fell, or were placed, within a metre or so of where they were last used or accumulated. Once under the floor, they were concealed between joists that run perpendicular to the boards and were subject to further taphonomic processes. The first of these was due to disturbance or refuse deposition when boards were pulled up for maintenance work. Such human traffic in the underfloor spaces is likely to have caused damage to fragile items and other items in the deposit may have been moved or removed and discarded to make way for cables or other fixtures. It is also common that when a few boards have been pulled up, other ‘above board’ rubbish was probably discarded beneath them, prior to their reinstallation.

The second taphonomic process was disturbance from rats and other rodents. There is ample historical and archaeological evidence for rats at the Hyde Park Barracks. In 1864, Matron Hicks protested against Medical Officer Dr Walker’s plan to lay rat poison in the building, owing to the smell and the ‘injurious’ effects it may have had on the expected immigrants (Daily Reports, 25 June 1864, SRNSW 9/6181b). Two years later Dr Walker was still struggling with the rats in his dispensary, which had become so infested with rodents that ‘the destruction of Drugs and breakage of Glass is really very serious’ (Memo, 5 Sept 1866, SRNSW 2/642A, see ‘Medicine’ for full quote). Ellen Jane Purnell, an inmate of the Asylum, claimed in 1886 that while Newington had some rats, it was nothing to the Hyde Park Barracks, which was ‘a regular pig-stye’ (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:460).

At least six complete or near-complete rats’ nests and a considerable number of rat carcasses have been recorded in the Barracks assemblage. Rats and mice form nests from any soft, portable material they find in their immediate environment, with each nest at the Barracks comprising paper, straw, grasses and large quantities of cotton scraps (Barnett 1976:148). Rats are highly adaptive creatures, readily exploiting the material culture of humans, as well as being very social animals, creating separate nest areas for sleeping, eating and disposing of wastes. The black rat (Ratus ratus) typically lives in the higher parts of a building, including walls and ceilings, whereas the brown rat (Ratus norvegicus) prefers ground burrows (Barnett 1976:4). Rats will range up to 50 metres from their nest to find food, often returning to the nest to eat in safety or to hoard the food (Hendrickson 1983:86; McDonald 2005). They can also climb vertical surfaces and squeeze into narrow spaces. Higginbotham considered that mice could easily have squeezed through mortise and tenon joins between the principal beams and joists on the upper floors, giving them ‘free access throughout the underfloor spaces’, but that rats, being larger rodents, may have been confined to joists along the window bays, where much gnawing was observed (Higginbotham 1981:32). Rats spend much of their waking time gnawing to keep their front incisors from growing too long, and can cut through wood, bone, concrete and even sheet metal (Hendrickson 1983:86). This behaviour is evident at the Barracks in the form of numerous gnawed books, buttons, textiles and wood offcuts.

Rodent activities have impact on the formation of the archaeological assemblage. Some items, especially lightweight and portable material such as fabric scraps, may have been ‘stolen’ by rats from above the floorboards during the night, and other items, lost below the boards, may have been relocated by rats within the underfloor space between rooms and even levels.

Mice skeletons were also recorded in the Barracks. Several were contained within a matchbox deposited below the floor at the eastern end of the corridor on Level 3 (UF17967). The skeletal material includes the remains of at least three individuals, represented by two well preserved skulls and segments of vertebral columns with articulated ribs. Further details of this item are provided in Davies and Garvey (2013).

In addition to accidental loss and rodent disturbance, another means of deposition below the floor was intentional discard or concealment. Notwithstanding the large gaps between the 14butted floorboards on Levels 2 and 3, many of the items recovered simply could not have been lost accidentally, or dragged by rats below the boards. Matchboxes and clay pipe bowls, for example, are too large to fall through the widest cracks or even large knots in floorboards, but may easily slip through or be placed in a small disused cut in a board. Larger objects, such as the complete pharmaceutical and schnapps bottles, can only have been deposited by lifting a board. Given that these large items were mostly found near windows and door frames where Varman (1981:7) notes that boards were shortened for repairs, the opportunities for lifting boards would have been greater. The possibility remains that the boards were lifted during renovation works (Figure 2.3), rather than by the inmates themselves.

In summary, the majority of the Hyde Park Barracks underfloor assemblage is likely to derive from accidental loss and incidental sweepings, most of which will survive in the general locale of where they were lost. A small but unquantifiable percentage of the assemblage probably derives from refuse following maintenance work, and a small number of items were probably deliberately concealed beneath the floorboards. Similarly, a small percentage of the assemblage was probably dragged beneath the floorboards by rats and mice, and a much greater proportion of the remaining deposit is likely to have been disturbed or relocated by rodents. It is also possible that some items were dragged from room to room, or even from floor to floor, for nest-building.

Figure 2.3: Floor cavity on Level 3 (P. Davies 2009).

RECOVERY OF THE UNDERFLOOR ASSEMBLAGE

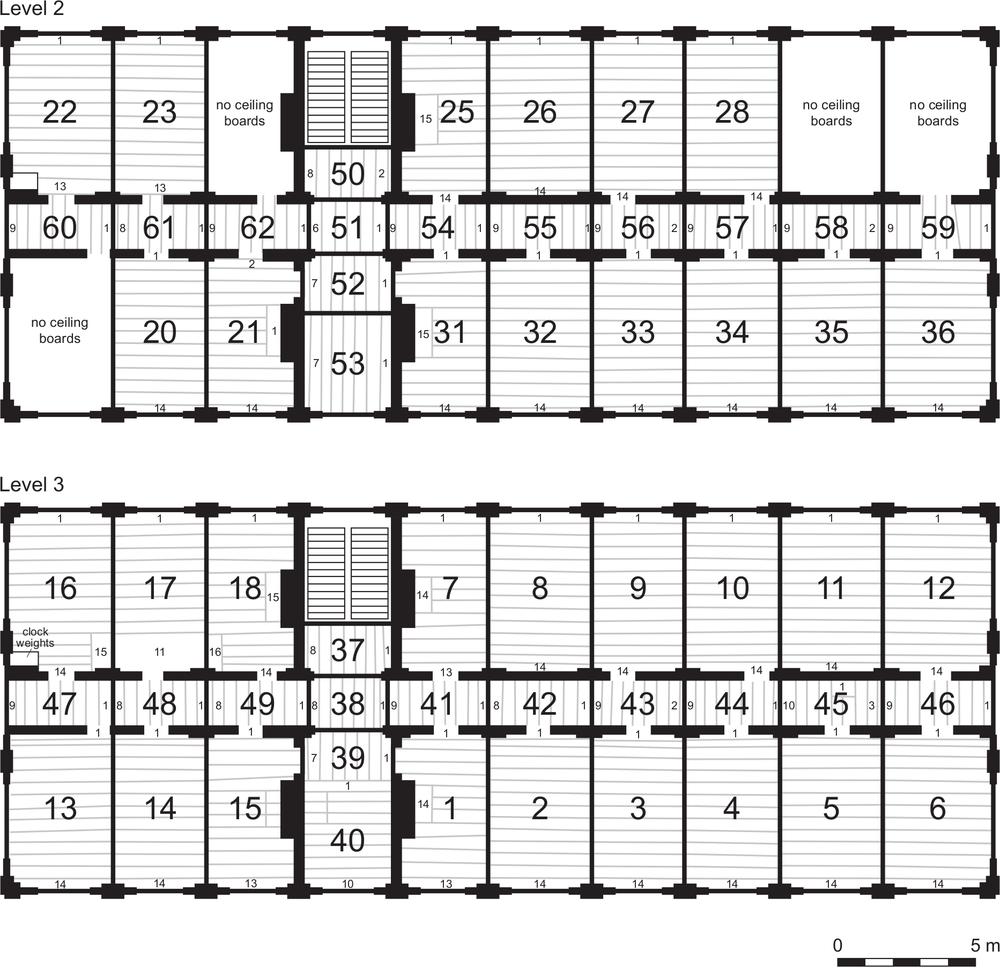

The archaeological collection at the Hyde Park Barracks is primarily the result of archaeological excavation and artefact recovery in the main building and grounds in 1980–1981. This process is described below in more detail in ‘History of the Collection’. The underfloor assemblage was recovered from discrete spatial units on Levels 2 and 3. The spaces between each joist (‘Joist Space’ or JS) were grouped into areas partitioned by principal beams (‘Joist Groups’ or JG). All JGs were numbered from 1 to 62 (Figure 2.4). The JSs within each group were numbered from 1 to 14, running north to south in the main rooms and east to west in the corridor and stair-landing spaces (Figure 2.4).

Joist Spaces varied a little in size over the full extent of Levels 2 and 3. Generally, however, each subfloor JS measured about 400 mm in width, 200 mm in depth, and up to 3.70 m in length. The size of the underfloor area from which the artefacts were recovered included approximately 340 m2 on Level 2 and 430 m2 on Level 3, or about 770 m2 as a whole. This represents a considerable scale of archaeological ‘excavation’, and one that yielded a substantial collection of material refuse.

Floorboards were removed to allow the recovery of the underlying deposit, and were returned to their original location in the later stages of the restoration (Potter 1981:30). Larger items, including what appeared to be intact rats’ nests, were removed manually while the remainder was recovered with industrial vacuum cleaners and bulk bagged for later analysis. Mider (1996 [1]:5) notes that the corridor areas were not vacuumed ‘due to the high level of perceived disturbance from later building works (the installation of services)’, which reduced the quantity of material recovered from these underfloor spaces. 15

Figure 2.4: Plan of Level 2 and Level 3 showing joist groups (in large figures) and joist spaces.

SUMMARY OF THE UNDERFLOOR ASSEMBLAGE

The Hyde Park Barracks underfloor assemblage is characterised by both the diversity and the quantity of artefact forms represented, including large numbers of well preserved organic items (Table 2.1 and Table 2.3). While most conventionally excavated assemblages are, typically, dominated by glass, ceramics and ferrous items, the Hyde Park Barracks material includes thousands of paper, textile, leather and other organic artefacts, along with large quantities of nails and other building debris. For some items, such as clay pipes, matches and matchboxes, pen nibs and textile offcuts, the underfloor collection includes some of the largest quantities of such material recorded from archaeological sites in Australia.

16

| Level 2 | Level 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Room | Joist group | Fragments | Room | Joist group | Fragments |

| L2-1 | JG22 | 1,577 | L3-1 | JG16 | 1,033 |

| JG23 | 1,462 | JG17 | 586 | ||

| Total | 3,039 | JG18 | 1,862 | ||

| L2-2 | JG50 | 81 | Total | 3,481 | |

| JG51 | 481 | L3-2 | JG37 | 7,011 | |

| Total | 562 | JG38 | 90 | ||

| L2-3 | JG25 | 578 | Total | 7,101 | |

| JG26 | 509 | L3-3 | JG7 | 2,086 | |

| JG27 | 1,794 | JG8 | 844 | ||

| JG28 | 1,040 | JG9 | 2,425 | ||

| Total | 3,921 | JG10 | 2,524 | ||

| L2-57 | JG54 | 305 | JG11 | 2,238 | |

| JG55 | 196 | JG12 | 2,684 | ||

| JG56 | 266 | Total | 12,801 | ||

| JG57 | 69 | L3-4 | JG41 | 218 | |

| JG58 | 23 | JG42 | 59 | ||

| JG59 | 2,722 | JG43 | 118 | ||

| Total | 3,581 | JG44 | 97 | ||

| L2-6 | JG31 | 2,124 | JG45 | 102 | |

| JG32 | 2,583 | JG46 | 1,363 | ||

| JG33 | 3,255 | Total | 1,957 | ||

| JG34 | 1,951 | L3-5 | JG1 | 1,765 | |

| JG35 | 1,689 | JG2 | 2,880 | ||

| JG36 | 1,810 | JG3 | 955 | ||

| Total | 13,412 | JG4 | 487 | ||

| L2-7 | JG52 | 36 | JG5 | 1,329 | |

| JG53 | 0 | JG6 | 1,981 | ||

| Total | 36 | Total | 9,397 | ||

| L2-8 | JG20 | 1,371 | L3-6 | JG39 | 4,620 |

| JG21 | 1,034 | JG40 | 1,353 | ||

| Total | 2,405 | Total | 5,973 | ||

| L2-9 | JG60 | 912 | L3-7 | JG13 | 3,936 |

| JG61 | 368 | JG14 | 2,467 | ||

| JG62 | 365 | JG15 | 1,800 | ||

| Total | 1,645 | Total | 8,203 | ||

| L3-8 | JG47 | 305 | |||

| JG48 | 54 | ||||

| JG49 | 179 | ||||

| Total | 538 |

Table 2.2: Summary count of artefact fragments by joist group and room number.

17

| Item | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ammunition | 16 | 31 | 3 | 50 |

| Bead | 71 | 452 | 368 | 891 |

| Bone | 6,084 | 2,057 | 4,709 | 12,850 |

| Bottle glass | 1,284 | 831 | 3,002 | 5,117 |

| Building materials | 768 | 2,053 | 2,250 | 5,071 |

| Button | 355 | 193 | 396 | 944 |

| Ceramic (table) | 817 | 46 | 205 | 1,068 |

| Cigar/ette | 2 | 65 | 69 | 136 |

| Clay tobacco pipe | 2,090 | 302 | 1,006 | 3,398 |

| Clerical fastener | 134 | 150 | 694 | 978 |

| Clothing accessory | 28 | 45 | 51 | 124 |

| Coal (fuel) | 69 | 49 | 6 | 124 |

| Coin/token | 29 | 14 | 15 | 58 |

| Comb | 15 | 20 | 23 | 58 |

| Cotton reel | 4 | 20 | 72 | 96 |

| Cutlery | 135 | 15 | 75 | 225 |

| Document | 405 | 408 | 813 | |

| Electrical | 95 | 506 | 250 | 851 |

| Furnishing | 103 | 86 | 39 | 228 |

| Game piece | 6 | 13 | 2 | 21 |

| Garment | 27 | 106 | 133 | |

| Hardware | 144 | 694 | 308 | 1,146 |

| Hook and eye | 817 | 341 | 409 | 1,567 |

| Hat (straw) | 24 | 90 | 114 | |

| Jewellery | 9 | 9 | 14 | 32 |

| Jute rope | 35 | 113 | 148 | |

| Leather | 299 | 204 | 476 | 979 |

| Lighting (lamp) | 61 | 62 | 70 | 193 |

| Match | 17 | 2,070 | 3,320 | 5,407 |

| Matchbox | 1 | 25 | 417 | 443 |

| Medicinal | 48 | 37 | 379 | 464 |

| Nail | 2,431 | 7,357 | 7,042 | 16,830 |

| Newspaper | 22 | 422 | 321 | 765 |

| Organic | 1 | 262 | 646 | 909 |

| Other | 107 | 274 | 475 | 856 |

| Packaging | 193 | 63 | 102 | 358 |

| Paper | 23 | 2,349 | 8,214 | 10,586 |

| Pen | 71 | 99 | 302 | 472 |

| Pencil (graphite) | 3 | 37 | 20 | 60 |

| Personal item | 54 | 42 | 88 | 184 |

| Pin | 2,820 | 1,937 | 2,779 | 7,536 |

| Printer’s type | 1 | 1 | ||

| Religious item | 1 | 16 | 229 | 246 |

| Seed | 468 | 1,206 | 2,730 | 4,404 |

| Sewing tool | 32 | 56 | 44 | 132 |

| Shell | 385 | 99 | 201 | 685 |

| Slate pencil/board | 22 | 44 | 9 | 75 |

| Soap | 13 | 14 | 27 | |

| Stoneware | 87 | 5 | 80 | 172 |

| String/cord | 186 | 149 | 335 | |

| Table glass | 8 | 12 | 21 | 41 |

| Textile | 352 | 2,882 | 7,120 | 10,354 |

| Tool | 13 | 27 | 47 | 87 |

| Toy | 28 | 36 | 16 | 80 |

| Unidentified | 638 | 611 | 613 | 1,862 |

| Total | 21,260 | 28,917 | 50,607 | 100,784 |

Table 2.3: Artefact fragment counts in the main building of the Hyde Park Barracks.

18The deposition of artefact fragments across Levels 2 and 3 is relatively even, allowing for the loss of material from four joist groups (19, 24, 29 and 30) during conservation work. There is, however, a distinct concentration of material from the stair landing on Level 3 (discussed below) and in certain floor areas (Level 2: JG33, JG59; Level 3: JG13, 9–12; see Table 2.2). This may be the result of increased rodent activity, or the consequence of damaged floor boards allowing greater accumulation or lifting to dispose of refuse. The corridor areas generally have much less material because they were mostly ceiled later during the legal phase of occupation of the building.

The Hyde Park Barracks assemblage includes, in total, well over 100,000 artefact fragments (Table 2.1). The underground assemblage includes artefacts recovered from excavations in courtyards and peripheral buildings of the Hyde Park complex, as well as from Level 1. These represent approximately 29% of the total collection, with the remainder coming from the underfloor areas on Levels 2 and 3.

THE STAIRWELL LANDING ON LEVEL 3

One of the greatest concentrations of artefacts across the upper two floors of the main Barracks building comes from the stairway landing on Level 3, in Joist Groups 37, 38, 39 and 40. This includes an area of flooring in place of the original southern stairway (a mirror image of the one that survives today) that was probably installed in 1862 when the Asylum moved in, to create additional floor space on all three levels (Figure 2.5). We discuss the Level 3 landing here because of the large quantities of artefacts recovered from this area and their implications for the activities of the Asylum women.

A total of 13,074 artefact fragments were recorded in the landing spaces on each side of the corridor, including large quantities of clay pipes, textile offcuts, newsprint and religious texts. These represent 16.2% of the total underfloor assemblage in an area that comprises about 2.6% of the available floor space. In contrast, the floor spaces below the landing on Level 2 (JG 50, 51, 52 and 53) yielded only 598 artefact fragments, or 0.7% of the total underfloor assemblage. This relates in part to the removal of the staircase around 1862 and the removal of JG53. Nevertheless, the density of material below the Level 3 landing in comparison with the remainder of Levels 2 and 3 suggests that the deposits relate to specific activities on the landing itself.

Figure 2.5: The surviving landing on Level 3 (P. Crook 2004).

The material from this small area is also interesting for the high integrity of the artefacts recovered from these deposits. There were 39 complete matchbox sets (with tray and cover), many with labels still attached and others with matches (mostly burnt) still inside. In addition to these there were 22 complete covers that found their way under 19the floor. There were also more than 40 complete or near-complete clay pipe bowls. While it might be easy to lose a fragment of a bowl or stem, dropping the whole bowl (usually 2 cm across and 3 cm high) through the floor cracks is far less likely. This is also the case for matchboxes, which measure roughly 6 x 4 x 2 cm, suggesting that they were deliberately stashed or trashed.

Most of the paper fragments date to the 1870s and 1880s, with 111 newspaper fragments dating from 1870 to 1886. There were also 39 datable matchboxes, most with tight date ranges within the 1870s and 1880s. These two independent means of dating — one being printed dates on newspapers or the mention of known, datable events, and matchboxes with known manufacturing dates — are rarely available to archaeologists and support the broad dating of this deposit to the 1870s and 1880s.

The stairwell landing deposit thus largely represents the last 10 or 15 years of the Asylum’s life. The deposition of large quantities of material beneath the floorboards in this area may relate to a range of factors. Numbers of inmates increased relentlessly over the years, exacerbated by the closure of the Port Macquarie Asylum in 1869, and occasions when women were forced to sleep in the corridors, resulting in more women gathering in the few available communal spaces. The physical decay of the building may also be implicated, with areas of heavy traffic leading to loosening of old butted floorboards. Newspapers from the 1870s may well have come from William Hicks following his marriage to Lucy Applewhaite in 1870. It is also possible that the accumulating pressure of inmate numbers and other responsibilities weighed on the Matron such that it gradually undermined the workings of the institution, and undesirable behaviours developed beyond her watchful gaze.

HISTORY OF THE COLLECTION

The record of the collection, the artefact catalogue, has been in the making from 1981 to the present day. Until 1998, the collection was divided into separate ‘Underfloor’ and ‘Underground’ collections, and each component had been organised, analysed, recorded and assessed by several project teams. Curators of the Hyde Park Barracks Museum developed a single database of the entire collection in 1998 by combining the ‘Underground’ and ‘Underfloor’ assemblages into a unified catalogue. In this section we briefly outline the history of excavation, assemblage formation and catalogue development at the Hyde Park Barracks over the last 30 years (Table 2.4).

Initial restorative work was carried out at the Hyde Park Barracks in the last years of the Attorney General’s occupation during the late 1970s. The Public Works Department (PWD) then began more substantial construction work in 1979 to restore the Barracks to its convict phase in advance of its conversion to a history museum. The warren of ‘sub-standard accretions’ that cluttered Greenway’s original court was demolished and the many structures that had enclosed the main barrack building were removed (Proust 1996).

| Year/s | Project |

|---|---|

| 1980 | Excavation and analysis by Carol Powell |

| 1980 | Test-trenching by Wendy Thorp and team in the main building, north range and yard |

| 1981 | Excavation by Patricia Burritt and team of underfloor and underground deposits |

| 1981–1983 | Salvage excavation by Elizabeth Pinder |

| 1981–1984 | Salvage excavation by Graham Wilson at Bakehouse, Southern Gatehouse and Northern Gatehouse |

| 1982 | Artefact conservation by Glennda Marsh |

| 1985–c.1994 | Sydney University research design and preparation for catalogue of underfloor artefacts |

| 1991 | HPB Museum opened with display of artefacts |

| 1994 | Wendy Thorp Artefact Review and Management Recommendations: completed underground catalogue |

| 1995 | Finalisation and reporting of the catalogue of underfloor artefacts by Dana Mider |

| 1996 | Wendy Thorp unstratified artefacts report |

| 1997 | Peter Tonkin artefact ‘stock-take’ of underfloor and underground collections |

| 1998–2001 | The Hyde Park Barracks database |

| 2001–2006 | ‘Exploring the Archaeology of the Modern City’ project by Tim Murray, Penny Crook, Laila Ellmoos and Sophie Pullar |

| 2006–2011 | ‘An Archaeology Institutional Refuge’ project by Tim Murray, Penny Crook and Peter Davies |

Table 2.4:20 Outline of projects affecting the Hyde Park Barracks collection and its catalogue.

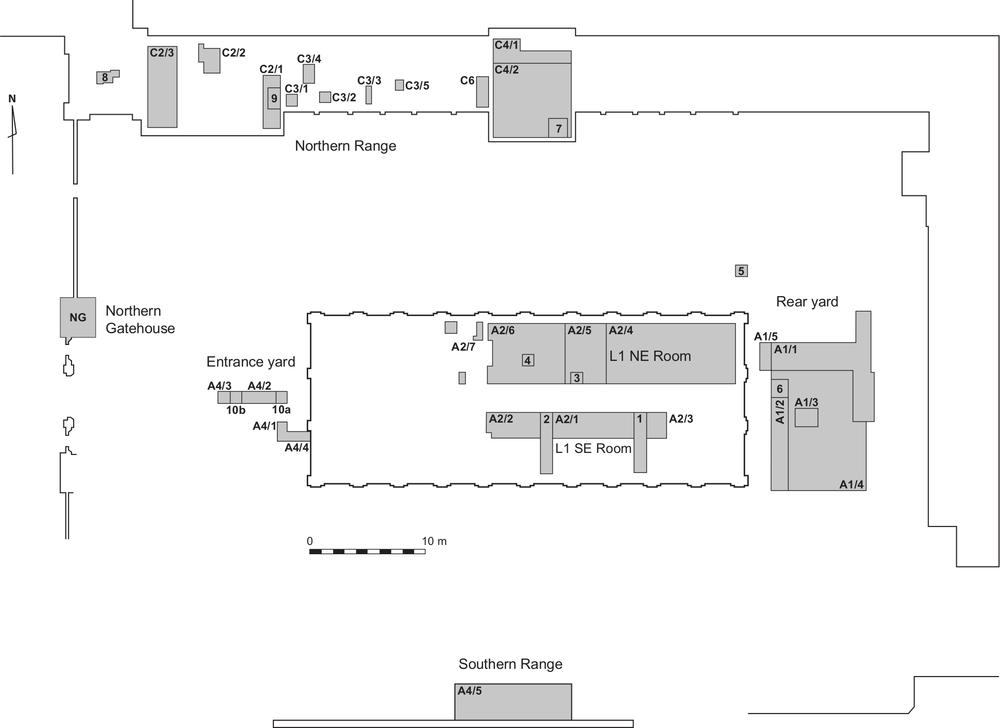

Figure 2.6: Location of excavation trenches; ‘4’ = Stage 1 excavations (1980); ‘A2/6’ = Stage 2 excavations (1981).

As restoration and construction work was underway, Carol Powell undertook archival research on the Hyde Park Barracks and the neighbouring buildings of the Sydney Mint, which were also being restored at the time. Powell also recorded important artefacts exposed during the conservation work (Potter 1981:1). It became apparent that the quantity of archaeological material at both complexes was extensive and archaeologist Wendy Thorp was commissioned in September 1980 to undertake a test-trenching program to better identify the nature and extent of the archaeological resource. These ‘Stage 1’ excavations took place beneath the floor of Level 1 and at several locations around the courtyard and within the buildings of the northern range (Figure 2.6).

At Thorp’s recommendation, an additional and larger-scale excavation program was proposed, and Patricia Burritt was commissioned to undertake the work while the PWD’s restoration project continued. This phase of the work came to be known as the ‘Stage II’ excavations and was conducted in 14 working weeks over an 11-month period from 23 December 1980, with 11 archaeologists, a conservator, a photographer and 250 volunteers (Burritt 1981:12, 31; Potter 1981:12, 31).

Both programs revealed archaeological material in trenches dug across the buildings and courtyards of the Hyde Park Barracks complex, and in the underfloor cavities of the main dormitory building. Many smaller excavations were undertaken as work continued in preparation for the opening of the museum in 1984. These were the result of the installation of pipes or the building of the Australian Monument to the Great Irish Famine (e.g. Wilson 1983). All disturbances to the ground surface since then have been supervised by an archaeologist.

The underground collection thus comprises artefacts retrieved from soil-based contexts in the grounds of the Hyde Park Barracks, distinct from the material retrieved from the underfloor spaces of the main building. The latter survives in superior condition to the former, and with a greater range of materials, hence the original division of the catalogue. The underground material comprises artefacts recovered during test-trenching by Wendy Thorp, excavation by Patricia Burritt in the main building and elsewhere, and salvage work undertaken by Graham Wilson at the Northern and Southern Gatehouses (Wilson 1983) and within the courtyard (Wilson 1986). Artefacts retrieved from 21other monitoring work (e.g. Pinder 1983; Graves 1994 and 1995; Tonkin 1997) do not appear in the database, while material from Tonkin’s (1997) monitoring work is waiting for cataloguing and database entry.

On completion of the main excavations in 1981, the artefact assemblage was cleaned, sorted, inventoried and rebagged. The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS), which became manager of the Hyde Park Barracks Museum and its collection at the same time, undertook conservation work on several items. The collection was stored on site for some time and then moved to the MAAS store at Redfern. At the MAAS store, the material was physically affected by flood waters and its archaeological integrity diminished. Some objects, including items selected for display, were separated from their context numbers. Parts of the Mint and the Hyde Park Barracks collections were also mixed together (Wilson 1985:20).

In 1985, with funding from a National Estate Grant, Andrew Wilson (then of the MAAS) began a major review, re-catalogue and reassessment of the underfloor collection, which was moved to the University of Sydney for that purpose. The project involved the preparation of a ‘research design’ for the analysis, specifying elements of the catalogue and fields required, and tested the use of the proposed database system, Minark, on a bibliographic inventory of reports and references (Wilson 1985, 1989). Artefact recording was undertaken at the Centre for Historical Archaeology at the University of Sydney by Dana Mider, Andrew Wilson, Julie Dinsmoor and Tony English between 1990 and 1996 (Mider 1996). No analytical or interpretive work was undertaken in the scope of this project and no final report was produced.

Management of the Hyde Park Barracks and its collection was transferred to the Historic Houses Trust (HHT) of New South Wales in 1990. In the following year the majority of the collection was moved to its new home in the Archaeology Store and Study Room on Level 2 of the central dormitory building. This room was the first such dedicated archaeological research facility of its kind in Australia and its system for accessing artefacts in the boxes was established by consultant curator Margot Riley.

In the late 1980s the Department of Planning commissioned Wendy Thorp and Campbell Conservation Pty Ltd to review the Hyde Park Barracks, Royal Mint and First Government House archaeological collections and provide recommendations for their management (Thorp & Campbell Conservation 1990, 1994). The project, completed in 1994, required the ‘sorting and consolidation’ of the Hyde Park Barracks assemblage and was the first project to provide a comprehensive catalogue of the material, albeit only of the underground component. Artefacts were re-examined and re-bagged, with artefact recording information written directly on stamped paper bags in which the artefacts were kept.

In 1996 Dana Mider completed the catalogue of the underfloor collection for the Historic Houses Trust (Mider 1996). Her report, commissioned by the HHT in 1995, was the culmination of the work originally proposed under the National Estate Grant in 1985 and 1989. Mider, assisted by Claire Everett, also undertook an audit of the artefacts and their records, rematching several objects dissociated from their provenance with their original identification number. Although they remained in separate and somewhat incompatible databases, a detailed record of both parts of the Hyde Park Barracks collection was now complete.

In 1997 the HHT commissioned Peter Tonkin to undertake a ‘stock take’ of the collection held on site and at the HHT’s Ultimo store. Tonkin identified several groups of provenanced artefacts that previously had not been gathered for cataloguing. These were catalogued by a small team of specialists and entered into the database.

In 1998 the Hyde Park Barracks began developing a database for public viewing of the archaeological collection. The two databases of underfloor and underground material were exported from Minark into Access, and reorganised into a new database structure that facilitated simple search mechanisms for broad categories of artefacts. Brian Robson undertook this work in consultation with assistant curators Gary Crockett and Samantha Fabry. By April 2001 the database was largely complete.

In 2001 the EAMC team, with funding from the Australian Research Council, began to utilise the data in this new Hyde Park Barracks database, which was customised with fields compatible with the EAMC Archaeology Database and designed to meet the project’s analytical requirements (Crook et al. 2006). This project included a systematic reassessment of the artefact catalogue, site records and the collection itself to examine the surviving archaeological resources and determine the potential for future work (Crook et al. 2003). The assessment identified a wide range of problems, from data errors and incomplete records to missing labels and lost items, and a general lack of reliable information. This established the need for substantial further work on the collection, which involved upgrading the catalogue of artefacts recovered from the underfloor spaces, with a particular emphasis on splitting ‘mixed bags’ containing bulk accumulations of paper, textiles and ‘mixed media’. Sophie Pullar carried out this work between October 2002 and January 2003, with additional research conducted between December 2003 and March 2004.

The result of this work included publication of a substantial volume (Crook and Murray 2006) presenting the results of the EAMC team’s re-examination 22of the historical and archaeological resources from the Hyde Park Barracks. With support from the Australian Research Council, Peter Davies and Tim Murray, from La Trobe University in Melbourne, conducted a further stage of analysis between April 2008 and February 2011. This project continued the re-cataloguing of bulk bags, especially of ‘mixed media’ and textiles. It resulted in the correction of 4885 database records and the addition of 1225 new records. At the conclusion of the project, 85 per cent of records relating to the Underfloor collection had been revised. The remaining uncatalogued material is predominantly bone, seed and shell.

4 Artefacts from the ‘Underground’ collection, recovered from excavations below the floor of Level 1 and elsewhere at the Barracks, are summarised in Appendix 3.

5 Underfloor total includes 513 artefact fragments from unrecorded locations.

6 Underground total includes artefacts from all excavations in courtyards and peripheral buildings of the HPB complex.

7 Room ‘L2-4’ was not assigned in PWD plans.