3

CHARITY AND IMMIGRATION IN 19TH-CENTURY NSW

Poverty and suffering were harsh realities for many people in colonial New South Wales. While there was generally a high demand for labour throughout the 19th century, accident and illness could bring destitution even in times of prosperity. Despite awareness of such problems, Australian authorities generally resisted poor laws and workhouses based on the English and Irish models, fearing that they could entrench a pauper class and undermine the moral fabric of society (Dickey 1992; Twomey 2002:56). Colonial authorities also believed that the high demand for labour in Australia meant that workhouses were not needed, and that their presence would undermine the reputation of the colonies as a place of opportunity and prosperity.

The result was a charity system that combined private philanthropy with public funding. Most charitable organisations depended on government subsidies to survive, and this gave colonial authorities considerable say in who received assistance and in what form it took. By the 1860s, governments were becoming increasingly involved in the provision of welfare services. While private charities mostly preferred to help (and reform) the ‘deserving poor’ such as ‘fallen’ women and orphan children, there was a growing need to help the sick, destitute, elderly and insane. Fear of and concern for ‘fallen women’ was at the heart of much charity and welfare in colonial society. The term applied not just to prostitutes but also to women who had conceived out of marriage, women guilty of ‘disorderly conduct’, as well as to female thieves, alcoholics and the ‘feeble minded’ (Kovesi 2006:50). The unemployed posed a particular problem as the able-bodied were traditionally denied assistance on the grounds that they were capable of supporting themselves. Such demands resulted in the creation of various government asylums for the aged and infirm, orphanages and industrial schools for children, and labour exchanges for the unemployed.

In the early years of settlement in Sydney various institutions were established to support the destitute. As early as 1796, Philip Gidley King, Commandant of the Norfolk Island penal station, founded two day schools, one for boys and one for girls, as well as a home for female orphans on the island, while a Female Orphan School was opened in Sydney in 1801 (Ramsland 1986:1–3). Relief was also provided by the New South Wales Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and Benevolence, formed in May 1813 by journalist Edward Smith Hall. Another organisation, the Colonial Auxiliary Bible Society, was formed in 1817. Both these groups relied on private patronage to support their religious and welfare efforts. The two societies merged in June 1818 to form the Benevolent Society of New South Wales. The objectives of the society were to:

relieve the poor, the distressed, the aged, and the infirm, and thereby to discountenance as much as possible mendacity and vagrancy, and to encourage industrious habits among the indigent poor, as well as to afford them religious instruction and consolation in their distresses. (Benevolent Society of New South Wales 1820:8 quoted in Cummins 1971:3)

Initially the society confined itself to outdoor relief, distributing cash, provisions or clothing on a weekly basis to the ‘deserving poor’. However, the need to provide some kind of lodging became apparent, and Governor Macquarie agreed to the construction of a building, at public expense, for accommodating the pensioners. It was located at the corner of Pitt and Devonshire Streets, where the Central Railway Station now stands. The two-storey brick building, which opened to receive inmates on 12 October 1821, was 97 feet long and 25 feet wide, with detached kitchen and outhouses. The simple internal design featured men’s and women’s quarters on different floors, each separated from dining areas by a central corridor containing the staircase. The inscription on the foundation stone read:

This Asylum for the Poor, Blind, Aged and Infirm, was erected in 1820, L. Macquarie Esq., being Governor

The asylum provided food and shelter to paupers, and able-bodied ones were expected to work. Inmates picked oakum, made clothes and shoes, baked bread and grew vegetables. The proportion of disabled, elderly and infirm inmates, however, made it necessary to provide medical assistance as well. By 1825 the building was already overcrowded, with 64 men and 29 women. This increased to 112 men and 32 women by 1830, with an average age of 65 years (Cummins 1971:5–6). By this stage a number of female paupers and pregnant women had also been admitted to the small hospital at the Female Factory in Parramatta (Salt 1984:111). Historian Anne O’Brien (2008:154) suggests that 24this early period of the society’s work saw a shift from paternalism and compassion for the victims of poverty to a desire to correct and reform them, a reflection of the influence of the new poor law movement at this time (Himmelfarb 1984:147–155).

The need for extensions and medical facilities resulted in the construction of a North Wing to the asylum in 1831 and a South Wing in 1839. The institution by now served increasingly as a hospital as well, supporting those with chronic diseases, while the Sydney Dispensary (formerly the Rum Hospital) handled acute cases. Sick and infirm patients at the asylum had separate accommodation from those in the workhouse. Chronic conditions included diarrhoea, dysentery and diseases of the lungs and eyes. Dr William Bland was the first of a number of visiting and resident surgeons and doctors, while nursing care was provided by the inmates in return for gratuities.

Limited outdoor relief continued to be available in this period via several ladies’ organisations, whose members visited pauper women in their homes. These included the Sydney Dorcas Society for Protestants (founded in 1830), the Strangers’ Friend Society for Catholics (1835), and the Ladies’ Dorcas Society for Distressed Jewish Mothers (from 1844), (Hughes 2004:20). A Female School of Industry opened in 1826 to accommodate girls who would be fed, clothed and trained as servants (Peyser 1939:119–120). Historian Christina Twomey suggests that despite colonial resistance to the English workhouse model of poor relief, the opening of benevolent asylums was often associated with civic pride, and regarded as a marker of a Christian community (Twomey 2002:56).

Figure 3.1: Sydney Benevolent Asylum, 1861 (source: Select Committee 1862: Appendix B).

The end of convict transportation to New South Wales in 1840 and the increase in free immigration meant growing demand for poor relief. A number of institutions were established in this period to accommodate vulnerable paupers. These included the Roman Catholic Orphan School (1836), the Sydney Female Refuge (1848), the House of the Good Shepherd (1848) and the Destitute Children’s Asylum, which opened in Paddington in 1852 and transferred to Randwick in 1858 (Austral/Godden Mackay 1997; Ramsland 1986:52–54). In 1867 an industrial training school for destitute children was established on the ship Vernon, moored in Sydney Harbour, which by 1891 had trained more than 2300 boys (Parkes 1892[1]:246).

The Sydney Female Refuge Society was established in 1848 with the explicit purpose of reclaiming ‘unfortunate and abandoned Females’, that is, ex-prostitutes (Godden 1987:292). About 300 females passed through the society’s refuge between 1849 and 1855, with numbers fluctuating between about 20 and 50 women. The society aimed to improve the prospects of the ‘fallen’ by training them in habits of good industry and set them back on the path of ‘rectitude and virtue’ (Sydney Female Refuge Society 1856:5). There was a heavy emphasis on Protestant religious instruction, moral training and industrial pursuits, which involved washing and needlework carried out on a commercial scale. The House of the Good Shepherd, a similar institution, was established by three Sisters of Charity in 1848, to provide refuge for former Catholic prostitutes (Godden 1987:292). Both institutions appear to have been granted accommodation in the former convict Carters’ 25Barracks, adjacent to the Benevolent Asylum at the south end of Pitt Street (Figure 3.1).

By 1849 there were almost 500 inmates in the Benevolent Asylum, half of whom were sick or infirm and in need of special accommodation. This included those who were blind, lame, ‘paralytic’ and ‘idiotic’8 (Cummins 1971:7). As a result of overcrowding, beds were laid on floors and dormitories reeked of body stench and excreta. The Asylum was described at this time as ‘little better than a huge charnel house’ (Rathbone 1994:33), but the Benevolent Society was also recognised as the ‘Government Almoner’, providing relief in place of an official poor law (Horsburgh 1977:77).

Relief from overcrowding came in 1851, when the male inmates were transferred to the Liverpool Hospital, which had been vacant for some years after it ceased to function as a convict hospital. At the time scrutiny of community-run charitable institutions such as the Benevolent Society increased (Hughes 2004:26–51; Select Committee 1862). As governments were forced to provide more support for such places, the concept of the relief of poverty as a moral option for the individual changed to that of collective responsibility for the welfare of the community as a whole. The ongoing debates culminated in the creation of the Board of Government Asylums for the Infirm and Destitute in 1862, with Frederic King appointed as Secretary. In addition to the acquisition of Liverpool Hospital, another asylum was established in 1862 in Macquarie Street, Parramatta, for blind and senile males. The mentally deranged were cared for by government lunatic asylums at Tarban Creek and Parramatta (Cummins 2003:33–41). In 1862, 150 women were also transferred to the newly established Hyde Park Barracks Asylum for the Infirm and Destitute, and the government became fully responsible for the management and operation of three colonial destitute asylums (Cummins 2003:53).

GOVERNMENT WELFARE

With the establishment of the Board of Government Asylums, the colonial government assumed substantial responsibility for the funding and care of destitute paupers. In addition to managing the Hyde Park Asylum for women, and Liverpool and George Street, Parramatta, for men, the Board opened an asylum in 1866 at Port Macquarie, in the former convict quarters, for both men and women. Lucy Applewhaite was opposed to the move, claiming ‘There was never a more cruel thing than moving the institution to Port Macquarie’, and that for the inmates ‘It would be a great misery to them … they would rather starve in the streets of Sydney’ (Q2379, 2391, Public Charities Commission 1874:77). By May of the following year, however, there were 47 women in residence, but the asylum was abandoned in 1869 owing to the cost of maintenance and difficulties in supervising its management (Government Asylums Board 1870:1; Hughes 2004:77). The closure led to the return of 55 of its inmates to the Hyde Park Asylum, pushing numbers there to over 200 women. Another asylum was established in Macquarie Street, Parramatta in 1875 as an erysipelas hospital for male and female paupers, and later it accommodated indigent inmates. At the same time, private charities flourished, with many devoted to assisting unemployed domestic servants and unmarried pregnant women, while government remained the main provider of support to aged and infirm women.

The Board met twice weekly in a boardroom set up in the Hyde Park Barracks. Members decided on applications for admission based on genuine physical infirmity and true destitution, for people without relatives or friends who could take them in and support them. Although the Board was responsible for deciding the merits of each applicant, it was frequently over-ruled by the Colonial Secretary, the courts, and other government agencies. The asylums, including Hyde Park Barracks, became dumping grounds for society’s outcasts, including the blind, epileptics, the physically and intellectually disabled, and the chronically and terminally ill — there was nowhere else for them to go (Hughes 2004:96). The inevitable result was over-crowding and constant pressure to find room for the growing numbers of impoverished invalids. At the 1873 Inquiry it was claimed that some inmates at Hyde Park Asylum were sleeping in its corridors (Q1272, Public Charities Commission 1874).

Accommodation at the Hyde Park Asylum was much cheaper for the government, however, than providing room for the sick poor in hospitals, thanks largely to Lucy Hicks’ economical management and her constant striving ‘to make the institution as self-supporting as possible’ (Public Charities Commission 1874, Special Appendix 4). The average cost per head at Hyde Park in 1862 was £15 8s 4d (Hughes 2004:217). Twenty-three years later this figure had decreased to £15 3s 2d, while hospital accommodation could cost three times as much (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1885:2).

During this time the government introduced legislation to help manage the growing problem of poverty and infirmity. A Workhouse Act, for example, was introduced in 1866 to control social deviants and paupers. Its aim was to get vagrants and ‘irreclaimable’ drunks off the streets and into a nominated workhouse. Charles Cowper objected to the bill on the basis that it allowed for the indefinite imprisonment of paupers by the government (Dickey 1966:16). The legislation was repealed in 1869,

26without ever being brought into use. The Public Institutions Inspection Act of 1866 provided for the appointment of an Inspector of Public Charities to inspect all hospitals, orphan schools and asylums funded wholly or partially from public revenue. From 1869 Frederic King took up the new role of Inspector, while continuing to serve as Secretary to the Government Asylums Board (Hughes 2004:107).

The need for welfare services expanded as the population grew. The City Night Refuge and Soup Kitchen, for example, was established in Kent Street in June 1868 to provide a meal or a bed for the night to the destitute. It was the initiative of Police Magistrate D. C. F. Scott, and combined with a pre-existing soup kitchen in Dixon Street in the Haymarket neighbourhood. The Refuge provided temporary support for individuals until they could gain admission to one of the government asylums (Dickey 1966:15; Peyser 1939:196–198). In 1870 there was a proposal to convert the Victoria Barracks in Paddington into a hospital for the treatment of ‘chronic and incurable cases of disease’ (Victoria Barracks 1870–71, p.150). This was intended to relieve pressure on the Sydney Infirmary and the destitute asylums, but the proposal was not acted on.

The Government Asylums Board was abolished in 1876, and replaced with a new Department of Government Asylums for the Infirm and Destitute, with Frederic King appointed as Manager. In response to suggestions that inmates should be forced to do useful work, King stressed, in his annual report, that ‘the Asylums are not poorhouses’, and that if inmates recovered their health and strength sufficiently to earn a living they left the asylum or were put out (Government Asylums Board 1876:930).

As the government expanded its management of institutional welfare during this period, philanthropy and charity continued to provide significant support to the poor and infirm. In 1878 the Sydney branch of the Charity Organisation Society (COS) was established, based on the British organisation founded in 1869. The society functioned as a charity referral service, aiming to co-ordinate assistance provided by different agencies and improve the efficiency of delivering aid to the ‘deserving poor’ by centralised record keeping and investigation of individual cases. The main philosophy of the COS was that indiscriminate charity was debasing to all concerned (Cage 1992:93).

By 1880 the government’s asylums were increasingly functioning as convalescent hospitals, as patients discharged from the Sydney Infirmary often lacked the health and strength to earn a living and ended up in one of the destitute asylums. The expansion of railway lines also brought the metropolitan asylums within reach of paupers from country areas. The death toll also increased at Hyde Park Barracks, as patients unable gain entry to a hospital were admitted to the Asylum in the last stage of illness. As inmate numbers at Hyde Park approached 300, work began on new facilities at Newington in 1884 (Government Asylums Board 1883:631). Construction had not been completed when the first inmates arrived in February 1886.

Female Immigrants

When the last convicts had been removed from the Hyde Park Barracks in 1848, the main building was largely given over to the use of an Immigration Depot. The protection of single women migrating to Australia was a matter of significant concern for the authorities, arguably more so than the need to provide for the aged, infirm and destitute. The colony’s future was dependent on its reputation as a place of security and opportunity. Young Irish, English, Scottish and Welsh women were to be the domestic servants and future wives of the colony, and their safe, healthy and uncorrupted arrival was considered a vital element in the economic and social development of New South Wales. Concern for their welfare was motivated by the colonial authority’s determination to ensure that the female immigrants did not join the colony’s destitute.

British campaigns to assist women emigrants to travel to the Australian colonies began in the 1830s (Chilton 2005; Gothard 2001:10; Rushen 2003). In the 1840s, the end of convict transportation to New South Wales sparked renewed interest in securing migrant labour, and hundreds of thousands of refugees were fleeing from the consequences of the Great Famine in Ireland. Under a new scheme, orphans from Irish poorhouses and industrious single women were brought to Australia under free passage, and from 1848 they were received at the Hyde Park Barracks where they remained — protected from unscrupulous employers and vagabonds — until suitable work could be found. While making a new home in Australia was a goal for most of the arrivals, others clung to the possibility of further migration and a return ‘home’ as an important assertion of belonging and identity (Fitzpatrick 1995:534).

Single women migrants were supposed to be between the ages of 18 and 35, but at times older women and girls as young as 15 could apply. Immigration assistance was restricted to the healthy and those of good moral character. In the 1870s and 1880s, single women migrating to New South Wales arrived under selection (advertised) or nomination schemes, and involved the payment of £2 by the young women themselves, or by nominating friends or relatives (Berry 2005a; Gothard 2001:182).

Regulations specified that unmarried women arriving in New South Wales were to be received into an immigrants’ home and provided with accommodation for up to eight days, under the authority of the Agent for Immigration. This was often extended to include young female children, who were brought to the Barracks while their 27parents remained on ship, with the aim of freeing the girls from the cramped conditions on board (SMH 24 May 1878, p.5). In the period from 1860 to 1886, more than 7000 government-assisted single female immigrants were hired from the Hyde Park Depot (Gothard 2001:220–221). While they waited for employment or reunion with family, the young women spent their time writing letters, reading, sewing and receiving religious instruction.

On hiring days, the immigrant women were usually quickly assigned to eager employers. Journalist John Stanley James (writing as ‘The Vagabond’) reported on the scene in 1878:

In ten minutes every servant was engaged. There was little preliminary bargaining, the hirers knew too well that they must not let a chance slip of obtaining a “help”, and as a rule the first girl on whom a lady fastened was engaged. The wages were from eight to fifteen shillings a week … (SMH 24 May 1878, p.5)9

James also thought, however, that the semi-public hiring rooms at the Barracks were totally unsuited to their purpose. He described the Depot as:

… one of those ugly public buildings ranging along Macquarie-street, remnants of the bad old times, and which would be better if burnt down … the accommodation [for immigrants] is most inadequate, although everything possible appears to be done by Mrs. Hicks to make the girls comfortable and happy … There is not half enough accommodation, nor anything like a sufficient staff to work this properly … (SMH 24 May 1878, p.5)

The Hyde Park Barracks was not, however, the first or only depot established to receive single immigrant females arriving in the Australian colonies during the 19th century. Caroline Chisholm, for example, who had arrived in Australia in 1838, established the ‘Female Immigrants’ Home’ in 1841 to help distressed single females who lacked employment due to the drought and economic depression of the period. The Home was located in part of the old wooden Immigration Barracks in Bent Street,10 behind the First Government House, and soon provided shelter for more than 90 women (Hughes 1994:145; Kiddle 1972:39). Chisholm also established depots in numerous country towns, where immigrant women were supported until they found work with local employers. When the Sydney Immigrants’ Home closed in 1842, Chisholm had helped more than 2000 people, including finding employment for more than 1400 single women, many of whom would otherwise have become paupers (Hoban 1973:94).

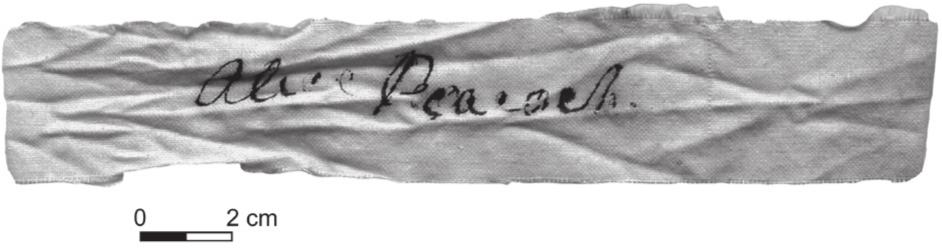

Figure 3.2: White cotton fragment with ink hand-writing, possibly part of a name-tag (UF5479; P. Davies 2010).

Immigration facilities were also set up in other colonies, cities and towns to protect (and control) young women, who needed food, shelter and time to adjust from shipboard life, prior to taking employment (Pescod 2003). Single men were regarded as competent to arrange their own employment, but single women were thought to be vulnerable to ‘immorality’, as well as needing instruction in local conditions, and in some cases, domestic work skills. Facilities for those accommodated varied considerably, and were often designed as temporary shelters of minimal comfort, so as to discourage the women from lingering.

Irish Female Orphans

Between 1848 and 1852 the Hyde Park Barracks was also used to accommodate Irish female orphans. The traumatic consequences of the Irish famine coincided with the growing demand for labour in the Australian colonies in the late 1840s. Earl Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies, tried to alleviate the labour shortage and imbalance in the sexes in Australia, by introducing assisted immigration for Irish orphans, especially females. Between October 1848 and August 1850, over 4000 female orphans were brought to Australia from the workhouses of famine Ireland, most of them between 14 and 17 years of age. Numbers included 2253 sent to NSW, 1255 to Victoria and 606 to Adelaide. There were also 61 sent to the Cape of Good Hope (O’Connor 1995:257–258; O’Farrell 1987:74). The first group arrived at the Barracks from the ship Earl Grey in October 1848. The girls were indentured for 12 months, with committees of ‘Gentlemen’ responsible for their distribution. Many girls took positions as domestic servants in rural areas, although some resented being sent into the countryside (Hamilton 2001:458).

Alice Peacock, aged 14, arrived with 104 single women on the Samuel Plimsoll from Plymouth in June 1879. As she was over 12, Alice travelled in the single women’s compartment rather than with her parents. Her father David, a labourer from Cornwall, was a constable for the single women on the voyage. Her mother Elizabeth, like Alice, came from London.

After three weeks at the Quarantine Station (there was typhoid & typhus fever on the ship), Alice came with the single women to the Hyde Park Barracks. Her parents remained on the ship until her father found work. They then collected Alice from the Barracks for the long journey to Adelong near Tumut, in southern New South Wales, where they were to live.

28The Orphan Committees dictated the terms on which the young women could be hired out. Fourteen-year-olds, for example, were to earn seven pounds per annum, 15-year-olds eight pounds and so on (Hoban 1973:223). These wages were below market rates, partly to defend the class system in place, and partly to compensate for the low skill levels of the orphan girls. In return they were to receive instruction in the craft of service, and suitable food, lodging and medical assistance. They were also to be free to attend the divine service of their choice on Sundays (McClaughlin 1991:15–16). The Irish Poor Law Unions had already provided each young woman with clothing, which included six shifts, two flannel petticoats, six pairs of stockings, two pairs of shoes, two gowns, and a shawl and bonnet, perhaps the first such outfit most had ever owned. Each was also provided with a bible and prayer book, soap, needles and thread, all to be stored in a stout, locked wooden box (McClaughlin 1991:89).

Irish newspapers condemned the practice of transporting helpless and pure Irish orphans to the distant cesspool of the Australian colonies, but the girls themselves were eager to go, and the first arrivals were quickly employed on good wages (O’Farrell 1987:74). Some young women deliberately entered workhouses to secure assisted passage to Australia (Hammerton 2004:162).

Irish orphans sent to Sydney were accommodated in the Hyde Park Barracks, where wards on the upper floors were fitted up as quarters for the ‘comfort and protection’ of these young women (Pescod 2003:19; SMH 30 September 1848). The Immigration Agent, Francis Merewether, emphasised that the Barracks possessed ‘every advantage which could be desired, with reference to the health, the seclusion, and the moral and religious instruction of the inmates, and the convenience of persons coming to hire them’ (quoted in McClaughlin 1991:15).

Another 4000 ‘orphan’ girls were brought to New South Wales between 1850 and 1852. Although not all of them were orphans, or children, or Irish, they came to be known as such, and single Irish women came to be regarded as a ‘servant’ class, with all the faults of an uneducated, semi-savage people (Higman 2002:75–76). Improving economic conditions in Ireland by the mid-1850s, however, meant good positions were becoming available for increasing numbers of domestic servants there, and the rate of emigration by young females to Australia began to slow (Gothard 2001:42). In subsequent years, child migration from the United Kingdom increased again, and many thousands were sent to Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand (Kershaw and Sacks 2008).

The Irish orphan scheme was a mixed success. In 1858 it was found that hundreds of girls had been returned to the Barracks as incompetent. There was considerable debate as to whether the girls themselves, mostly young and with little or no training in domestic service, were to blame, or if their employers had been ‘very hard upon them’, objecting to the ‘dirty Irish, and ignorant Irish papists’ (Select Committee 1858:403). In 1849 alone, more than 200 of the orphans had their Indentures cancelled by the Court of Petty Sessions. Reasons included bad conduct, being absent without permission, disobedience, insolence, idleness, neglect of duties, and several charges of assault (Select Committee 1858: Appendix J). Another cause for complaint was the desire of the Irish girls to attend Mass on Sunday mornings, when their employers much preferred to allow them out on Sunday evenings as being less disruptive to households.

Some of the girls returned to the Barracks were punished as virtual prisoners. Up to 50 at a time were confined in a separate building in the complex, under the supervision of a sergeant of police, and made to pick oakum ‘to keep them employed’ (Select Committee 1858:403). The room was known as The Penitentiary, and the girls worked, ate and slept here, allowed only a little exercise in an adjoining yard. When the Sisters of Charity visited and complained at the ‘unwholesome’ nature of the room, the orphan girls were sent to work in country areas and prevented from being hired in town again.

These cases, however, were in the minority, and most Irish orphan girls achieved modest success in their new lives in Australia. Mrs Capps, Matron of the Hyde Park Barracks from 1848 to 1853, admitted that for the most part she had very little trouble with them, even when there were 600 in the building and she had no assistant to help. Based on her own experience, Mrs Capps believed that the Irish girls were the best behaved, followed by ‘the Scotch’ and lastly the English. She was also impressed at the hard work and industriousness shown by the Irish orphan girls, and their willingness to send home money saved from the ‘pittance’ of their salaries (Select Committee 1858:402).

8 ‘Idiocy’ was a 19th-century scientific term indicating extreme mental retardation, with a mental age of two or less. ‘Imbecility’ was the term for intellectual disability less severe than idiocy, while ‘lunacy’ referred to mental illness or legal insanity.

9 Eight shillings per week converted to £20 16s per annum; fifteen shillings equalled £39 0s per annum. Wages for female domestic servants included board and lodging (Gothard 2001:212).

10 The building was erected by Governor Bourke in the early 1830s to accommodate celebrations for the Royal Birthday (Hughes 1994:145). By 1837 it was being used as temporary housing for immigrants.