4

THE WORKINGS OF AN INSTITUTION

The Destitute Asylum and Immigration Depot were two separate institutions, serving quite different purposes: one, the long-term care of aged, disabled and at times terminally ill women who could no longer support themselves; and the other, the short-term care of single women making a new life in the colony. Despite these different purposes, the aims of both institutions were very similar: providing shelter, food and medical care to women who, for the time they spent at the Hyde Park Barracks, were without support from the usual family and social networks.

It was perhaps these common needs that prompted the colonial government to manage both facilities from the same building, and under the same Superintendent: Matron Lucy Hicks. While each facility was financed from separate budgets, and the complex itself was compartmentalised with separate entrances, the line between Depot and Asylum was much harder to identify in the daily management of the institutions.

When the 150 or so inmates were transferred from the overcrowded Benevolent Asylum in 1862, they were allocated the third floor of the Hyde Park Barracks and a dedicated entrance was constructed at the eastern end of the building. Matron Hicks moved Asylum inmates into Immigration Depot wards when immigrant numbers were low (Q2306, Public Charities Commission 1874:74). During both the 1873 and 1886 parliamentary inquiries, Matron Hicks was adamant that immigrant and aged women were segregated, but in practice an absolute separation may not have been possible. In the 1886 Inquiry conducted after the Asylum had moved to Newington, it was reported that:

At Hyde Park, Mrs. Hicks states she superintended the Immigration Barracks, as well as the Infirm and Destitute Asylum. The institutions were practically merged as regards furniture and utensils — that is, if the Infirm and Destitute Asylum required anything the Immigration Barracks could spare it was taken, and vice versa. No inventory existed at Hyde Park. (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887, Appendix C, p.52)

It is likely also that the immigrant women relied on the Asylum dispensary from time to time. While partitions may have separated wards and parts of the building, the noises, chatter and moaning of aged women could not have been excluded from the floors below. In the 1860s, liquid matter could not be excluded from the floors below either. In 1865 there was a request to fit ceilings above the matron’s and sub-matron’s apartments, in the front rooms on Level 2, to prevent ‘the inconvenience arising from the leakage11 which occasionally takes place from the upper rooms’ (Immigration Agent to Undersecretary for Lands, 2 March 1865, quoted in Thorp 1980:VI.2).

The inmates nevertheless enjoyed a much healthier physical environment in the Barracks than in the old Benevolent Asylum. From the top floor windows they took in views to the east over the Domain to Woolloomooloo, while the sandstone spires of St Mary’s Cathedral rose to the south. Nearby was the expanse of Hyde Park, while directly across the road to the west were St James’ Church of England, the Supreme Court and the top of King Street which led down to Sydney’s busy retail district (Hughes 2004:57). By the mid-19th century, Macquarie Street had become one of Sydney’s most desirable residential locations (Mackaness and Butler-Bowdon 2005:53).

There are no internal floor plans of the Asylum when it was in the Barracks; and while the physical evidence of partitions and other room markings have been destroyed or superseded by later occupation, the struggle for, and negotiation of, space within the main and auxiliary buildings are apparent in the various government reports, special inquiries and general correspondence from 1862 to 1887.

The tug-of-war between the two main institutions, the Immigrant Depot and Offices and the Asylum, was often interrupted by other annoyances, such as the census calculations, the Master in Lunacy and other government departments which vied for corners of the ageing building (for evidence of their occupation, see ‘Official and Administrative Records’). The complex was subjected to shifting arrangements of wards, offices, hiring rooms, yards and hospital rooms at various times. The Colonial Architect was called in on many occasions to build a kitchen, a washhouse, a new entrance and water closets, and to make repairs such as removing lead pipes, cementing the yard and sheathing the shingled roof with corrugated iron (in 1880).

30The negotiation of space eventually favoured the Destitute Asylum and the pressing needs of ageing women over the fluctuating numbers of single immigrant women. By 1873, the Asylum had taken over about half of the main building and acquired the ancillary buildings of the NSW Volunteer Rifle Corp, although these were inadequate for use at the time.

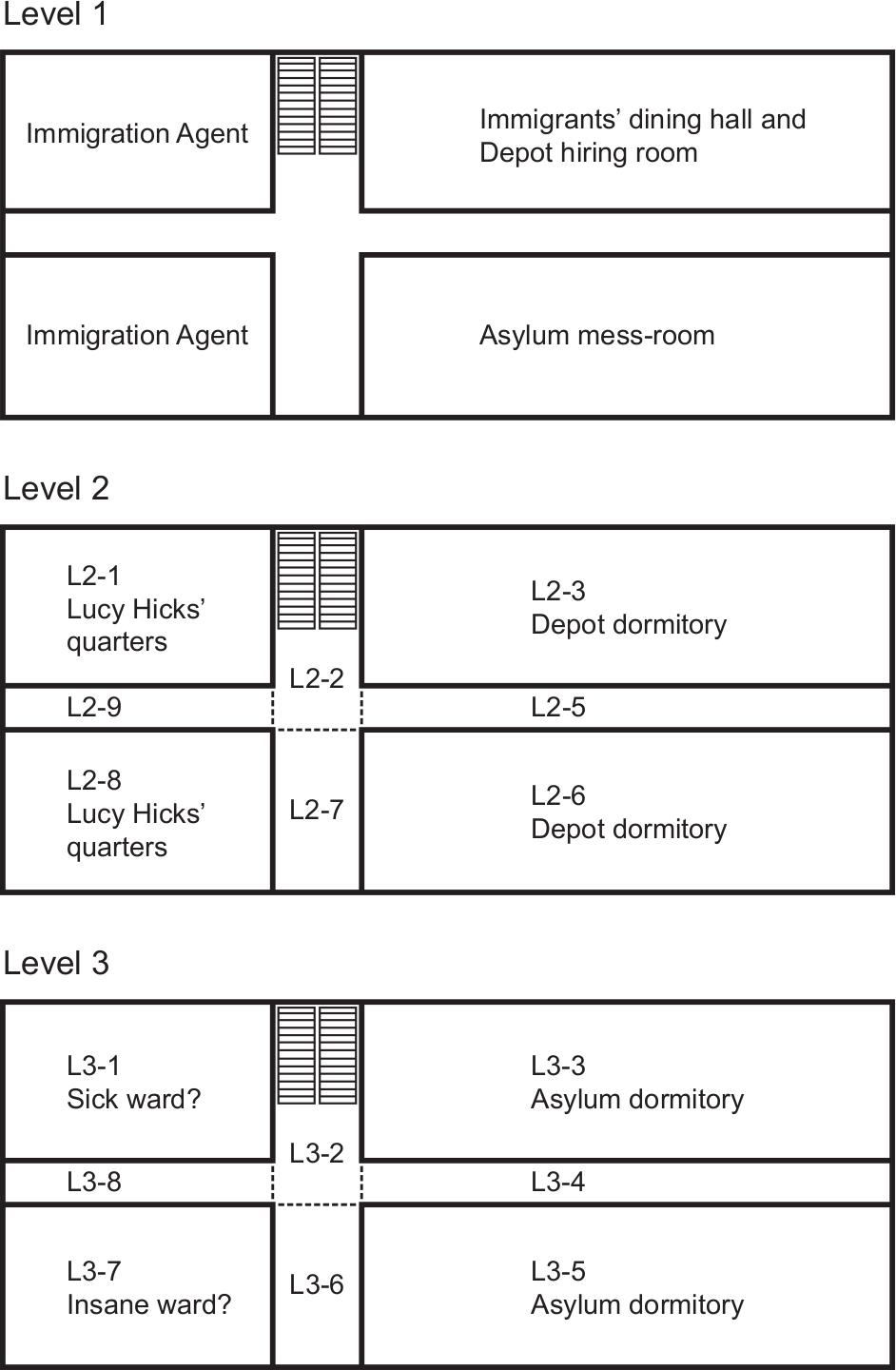

Owing to its physical dominance within the Barracks building, the following discussion of the operational concerns and daily activities at the Hyde Park Barracks during the period from 1848 to 1886 is focused more strongly upon the operation of the Asylum than on the Immigrants’ Depot. We work on the assumption that Level 3 was under the exclusive use of the Asylum from 1862 to 1886, and that the majority of the assemblage recovered from that level can be confidently attributed to the Asylum inmates. While inmates did occupy Level 2 from time to time, the assemblage on this level is more likely to be the result of use by the Immigration Depot, and the Matron’s family. We generalise an association of Level 3 with the Asylum and Level 2 (excluding the southern section) with the Depot.

ROOM USE

For the entire occupation of the Hyde Park Barracks as an Immigrants’ Depot and Destitute Asylum, we have no maps or diagrams of the internal layout of the main building. From evidence given at the 1873 Inquiry, however, along with various requests sent to the Colonial Architect for repairs, we can speculate on how the rooms may have been used. For example, Lucy Hicks reported:

The Government did speak of turning my apartments into two wards, and that would give accommodation within the building for forty more women; and they would build me a cottage at the gate. (Q2298, Public Charities Commission 1874:74)

This suggests that the matron’s apartments were in the main building and that they were equivalent to the size of a 40-woman ward, and probably in an area with two distinct parts. The likely place for such accommodation would have been the two smaller, western rooms on Level 2 at the front of the Barracks overlooking Queens Square (Figure 4.1). Being close to the stair, the matron had easy access to other parts of the building, and it is possible that the corridor was enclosed with a door and partition to give the family more privacy — although there is no physical evidence to suggest this either way.

The female immigrants, when in residence at the Barracks, mainly occupied the large northern room on Level 1 as a dining room and living area, and the large room above on Level 2, ‘plainly furnished but everything clean withal’ (SMH 24 May 1878, p.5). This is confirmed by Mrs. Hicks’ 1873 testimony. When asked how much of the main building was set apart for the immigrants, she replied:

Two large rooms, a large ward, and a dining hall. I had formerly three other rooms and an office, but Mr. Wise, at the time the Census was in preparation, applied and got these rooms, and his having them has put me to very great inconvenience. I have now no office or any other accommodation. (Q2302, Public Charities Commission 1874:74)

The office and very probably the ‘three other rooms’ would have been on the ground floor, a level always occupied by offices and semi-public functions such as the Hiring Room of the Immigrants’ Depot. This is reinforced by Matron Hicks’ later comments on cutting out calico in preparation for making the women’s clothing:

… I have felt greatly the loss of that office I used to have at the bottom of the stairs where I used to cut out … Many times I had an hour to cut out, and I could lock the room up and leave it; but now I am obliged to keep at it, and say I am not at home, for I cannot leave the material when once I begin to cut it out. (Q2368–2369, Public Charities Commission 1874:76)

Figure 4.1: Schematic plan of room functions and numbers.

31She went on to explain that the rooms had ceased to be used for preparing the census, but that she still did not have access to them. In another line of enquiry regarding the accommodation of disabled inmates:

Q2316 The room in which they [the ‘idiots’] were seemed very damp and dark? The room is dull, but I see them cheerful. I always make it my business to say, “Well, girls, are you comfortable here?” and I never have any complaints.

Q2317 How many are there there? I have eight in that room; one has St. Vitus’s dance12 very badly — cannot sit up from it. I cannot say that they are all idiots. There are eight very bad cases in that room.

(Public Charities Commission 1874:75)

It is likely that the ward to accommodate these eight cases was on Level 3, and was probably one of the smaller rooms at the western end of the building. The Asylum inmates used two large rooms at the eastern end of Level 3 as dormitories. The small room opposite the idiots’ ward may have accommodated women with acute or infectious diseases. In the absence of a dead house, this is probably also where bodies were washed and prepared for burial. Inmate nurse Ann Jeffreys (or Coffrey) advised Matron Hicks ‘not to come up’ following Priscilla Pritchard’s death by mortification (gangrene) because ‘it was a bad case’ (SMH 30 August 1866, p.5). Coffins were left in the lobby (which John Applewhaite noted was on the same floor as the hospital wards (ibid) which was probably on Level 2 (see ‘Death and Burial’ section below).

The dispensary was a small timber building attached to the rear, eastern side of the building, completed in April 1862 (Hughes 2004:74). The visiting doctor George Walker complained about the saturation of the building from water running off the roof, and later from the flow of excrement coming from the water closets above him (Hughes 2004:80).

In 1882 Matron Hicks and her family moved out of their quarters in the Barracks and took accommodation in Phillip Street. The Asylums Board used the rooms on Level 2 to accommodate 40 extra inmates, bringing the daily average to almost 300 (Government Asylums Board 1882:626).

THE MATRON

Editions of Cassell’s Household Guide in the 1880s outline the duties of matrons in English workhouses in a section entitled ‘Occupations Accessible to Women’:

The last occupation suitable to women under Local Government and other official Boards is that of matrons of workhouses. There seems no good reason why women from the middle and educated classes should not hold this situation. The one usually urged is that the positions of master and matron are generally held by a man and his wife, and that a superior woman could not hold a subordinate post under a master of the stamp at present employed. A recent authority writing on this subject says that, ‘as gentlemen of small means, military and naval officers on half-pay, and many others, have accepted the governorship of prisons, there can be no reason why they should not take charge of workhouses.’ The entire charge of a workhouse, containing from 500 to 700 souls, would seem as worthy of any man’s powers as any sphere of work that could be pointed out … In all workhouses the position of both master and matron is most important. Their authority is very great, and the post affords immense facilities for doing good …

Board, lodging, washing, and attendance, are all found; and the combined salaries of master and matron generally amount, in the larger workhouses, to over £200 per annum. Here, also, the work mainly consists in superintending their subordinates.

The general duties of the matron are to superintend the female inmates, to look after the cutting-out of clothes, &c., to visit the sick in the infirmaries once a day, to see that the kitchen and laundry-work are properly attended to, and the whole house scrupulously clean and tidy. She has also to give out the stores of linen and of provisions, and to see that the children are well, and to superintend the schoolmistress. Many, if not all, of these duties are such as every lady habitually undertakes in her own home; and when, in addition to this, we understand that the work of a matron is a real work of Christian charity, it is not too much to say that the post is a suitable one for any educated woman, with some force of character, and sound health. The classes of people who come under her charge are the old, and the sick, and orphans, and deserted children, who will look to the matron for all they will ever know of a mother’s loving care. In addition to this, to a good religious woman, there would be the opportunity of sometimes being able to hold out a hand of mercy to a lost and miserable sister; who, under her kindly ministrations, might yet aspire to a better life. (Cassell’s Household Guide c.1880:173)

While the Hyde Park Asylum had no young children in its care, this is a fairly accurate description of the duties that the Matron of the Immigration

32Depot, and later, the Matron of the Asylum, was expected to undertake, and the kind of woman she ought to be. She was responsible for maintaining discipline, enforcing personal hygiene, supervising the preparation of meals, ensuring the cleanliness of cooking and eating utensils, and airing the building and bedding (Hughes 2004:153).

When the Immigration Depot was established at the Hyde Park Barracks in 1848, quarters for a livein matron were provided. The first matron was a Mrs Capps (see section ‘Irish Female Orphans’) who served from 1848 to 1853, while Grace Tinckham was matron of the Depot in 1860 (Statistics of NSW 1860:21). Tinckham was followed by Hicks (then known as Lucy Applewhaite) who came to have the most enduring impact on the shape of the Immigration Depot and Destitute Asylum. She retained the position of matron until and shortly after the move to Newington in 1886.

Lucy was appointed matron on 13 May 1861 with an annual salary of £70, while her husband John commenced duties on 20 July 1861 as a clerk in the Hyde Park Immigration Office at a salary of 10 shillings per day (Hughes 2004:150–152). When the Government Benevolent Asylum was established at the Hyde Park Barracks in 1862, Lucy became matron of both the Immigration Depot and the Asylum, while John seems to have relinquished his position as clerk in the Immigration Office and become Master of the Asylum alone. His annual salary for the first year of setting up the Asylum was £200 and then it was reduced to £100 the following year. Lucy’s salary as matron of the Asylum was £100 and in 1863 her salary as the Immigration Depot matron increased from £70 to £100 (Hughes 2004:153).

When asked at the 1873 Inquiry about the wages she received in the early years of the Asylum, she replied:

Well, I held a double appointment in the Government Service previously. When Mr. Cowper — Sir Charles Cowper — placed me there, I was matron of the Immigrants’ Depôt, and Mr. Applewhaite was a clerk in the Immigration Department, with a salary of £285 per annum. We had a very good appointment then; and when the old people were brought there, Mr. Cowper wished us to undertake the duties connected with the Asylum, and promised us a salary of £300 per annum. When the other institution was formed our salaries for the Asylum duties were reduced to £200 per annum, and to make good the promise of the Government £100 each was given from immigration. (Q2273, Public Charities Commission 1874:74)

When her husband died in 1869, she took over his duties and eventually her income was reduced to ‘£200 a year from the Asylum, and … a nominal salary of £20 a year from the immigration’ (Q2274). In the 1870s, as the number of female immigrants fluctuated from year to year, her salary as Depot matron rose to £35 in 1872 and to £50 in 1877, so she was still earning £250 in her own right. For much of her time at the Barracks, Lucy was among the most highly paid matrons in New South Wales (Hughes 2004:158, 169). By way of comparison, Dr Robert Ward, the Surgeon and Dispenser at the Hyde Park Barracks, was paid £225 per year, although this was likely to be one of several salaries or income streams.

Initially Lucy was supported by a sub-matron, originally Alice Gorman13, and then by Mrs Kennedy, who resigned in August 1864. It is unknown whether there was some conflict between the two because it appears Mrs Kennedy gave notice on 30 March 1864, but then withdrew it. The Daily Reports written by Matron Hicks give little away. The entry for 1 August 1864 simply reads: ‘Mrs Kennedy Submatron has left the Institution today’ (Daily Reports SRNSW 9/6181b).

It is unclear who held this post thereafter but in the 1873 Inquiry, Matron Hicks indicated that her daughter, although ‘not an officer of the institution’, maintained the stock book (Q2281, p.73). Lucy’s 24-year-old daughter, Mary E. Applewhaite, was officially appointed sub-matron on 1 January 1875 with an annual salary of £50 (Hughes 2004:168). She held the post until her death in 1885, when Mrs. Cecilia J. Hyrons was appointed sub-matron (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:526). Another daughter, Miss Clara Applewhaite, also assisted Mrs Hicks as an unpaid officer in 1886 (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:446). This pattern of daughters helping their mothers to superintend welfare institutions was repeated elsewhere in the colony, and includes Mary Burnside and her daughter Jane at the Liverpool Asylum, and Catherine Dennis and one of her daughters at Parramatta (Hughes 2004:172).

THE INMATES

While the matron was responsible for the care of the inmates, she was not responsible for deciding who could be admitted to the Asylum. This was decided by the Board of Government Asylums for the Infirm and Destitute, a situation for which Matron Hicks was glad (Q2387, Public Charities Commission 1874:77). The sick and indigent must have waited anxiously during the Board’s sitting days to learn whether a bed could be found for them. Distinguishing between the urgency of needs within

33a population suffering the after-effects of half a century of convict transportation, mass migration, illness and economic downturns was a difficult task. Many deserving cases were turned away at the gate.

The prerequisites for admission to the Asylum were infirmity and inability to support oneself. Destitution alone was not enough, as Board members shared the prevailing view that the poor were to blame for their own misfortune. Cases for possible admission to the Asylum were brought to the attention of the Board by the Benevolent Society, other charities, clergy, well-meaning employers, the police, and the Sydney Infirmary, nearby on Macquarie Street. The cases referred by the Infirmary often caused the greatest disruption to the Asylum. These were patients deemed to have chronic conditions and long-term diseases, such as cancer and mental illness, which could not be cured by the medical resources of the dispensary.

Some of the mentally ill women were abusive or inclined to using obscenities, undressed and destroyed their clothing, or wandered around the wards at night and removed the bedclothes of other inmates. Some were also violent and attacked other inmates or inflicted injuries on themselves. Many suffered paranoid grievances such as fearing the matron or doctor sought to poison them or had stolen their children. Those with senile dementia were unaware of their surroundings and could not recall their names or other personal details (Hughes 2004:71). Mrs Hicks complained of receiving insane persons:

We have to keep them for ten days or a fortnight sometimes, and I have only a small room to put them in, and that one woman will perhaps keep 100 poor old souls awake night after night. (Q2373, Public Charities Commission 1874:76)

Such cases were the exception. These inmates should have been referred to the lunatic asylums at Tarban Creek or Newcastle. The more common chronic medical conditions affecting the inmates at Hyde Park were blindness, idiocy and crippled limbs. At least one case of St. Vitus’s Dance was recorded in the 1873 Inquiry.14 These inmates were lodged in the same small ward, and one of the able-bodied inmates was responsible for their care. The majority of inmates suffered from the effects of ageing and had no family networks to fall back on. The oldest recorded inmate at the Hyde Park Asylum was 106 in 1873 (Q2291, Public Charities Commission 1874:74). While her name is unknown, she was probably an ex-convict:

One who has attained the age 106 ‘goes,’ says Mrs. Hicks, ‘into a tub every Saturday morning like my own baby.’ This old woman, whom we saw in her bed, is doubtless an exconvict. She told us that she had come out in Governor —’s time (we could not catch the name), a genteel way of concealing the manner of her arrival (Hill and Hill 1875:336).

For many of these bed-ridden, chronically ill or elderly inmates, their admission to the Asylum was their final life transition, even though many survived for several years. Agnes Barr was the ‘oldest inmate’. She was transferred from the Benevolent Asylum on 15 February 1862, spent every day of the next 24 years at Hyde Park Barracks, before ending up at Newington in 1886 (Q4441, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:540). For the ablebodied inmates, however, the Asylum was more like a depot, where they stayed for short periods while their illnesses were at their worst, and were discharged as soon as they were well enough to work outside, or a new situation arose.15 This strategic, temporary use of the Asylum by many inmates suggests that the institution functioned not only as a place of refuge but also of respite, which the women used to help survive and endure life’s crises (see De Cunzo 1995:110–113).

Some of the women were acutely conscious of their fall in life. Hugh Robinson, the Inspector of Public Charities, reported in 1879 that many of the inmates at the Hyde Park Asylum were ‘of the most irreproachable character who once occupied highly respectable positions, and who are now destitute through no fault of their own’. These women felt uncomfortable at being forced into close and constant contact with other inmates of coarse habits and speech (Inspector of Public Charities 1879:856).

Some destitute women, however, refused to accept institutionalisation of any kind. In February 1876, for example, Sergeant Attwell of the Sydney Police took officers of the Sewage and Health Board to visit Sarah O’Neill. Sarah lived in a one-room brick house in Wattle Street near Blackwattle Swamp, where waste from the Colonial Sugar Refinery drained by. One window was boarded over with scraps of iron, while the other was used as a doorway for Sarah and her fowls, although according to a local shopkeeper she would often not leave the house for months on end. The room contained only a few mats and rags, and had no water. She lived there rent-free, kept alive by the produce of her chickens and scraps of food left by neighbours. When Attwell called out, in jest, that he had come to take her to the [Hyde Park] Asylum, ‘the wild looking uncombed elderly woman’ retorted that none of the O’Neills ever saw the inside of an asylum, and offered him some eggs. She had been born in Ireland and lived in the colony for 20 years, the last nine of them ‘in this hole

34(Suburban Sewage and Health Board 11 Progress Report 1875–76, quoted in Fitzgerald 1987:169).

Minnie Perks (or Perkins) is an example of the young women who could fall between the cracks of the charity system. She was a young Aboriginal girl, ‘apparently intelligent and of sound intellect’, but ‘quite blind’ (Hughes 2004:117). She was rejected by the Sydney Infirmary because she was not sick, from the Newcastle Asylum for Imbeciles because she was mentally competent, and from the Deaf, Dumb and Blind Institution because she was too old. Aged about 15 years, she was reluctantly admitted to the Hyde Park Asylum in 1874, as no one else would take her (Hughes 2004:118). She died there in 1877, aged 19, of chronic cerebritis (NSW Death Certificate 1878/80).

The vast majority of inmates at the Hyde Park Asylum remain anonymous, reduced to statistics in the Board’s annual reports. Joy Hughes (2004:58, n.29) has calculated that around 6000 women passed through the doors of the Hyde Park Asylum over its 24 years of operation, but we know the names of only a fraction, gleaned mostly from witness statements provided to parliamentary inquiries. The initial intake of around 150 women transferred from the Benevolent Society in 1862 included only 9 who were born in the colony. Of the remainder, half arrived as immigrants or the wives of soldiers, and the rest were convicts. A few had been in the Benevolent Asylum for more than 20 years (Empire 17 February 1862). Half were widows, while 20 were deserted and 4 had husbands in gaol. Fifteen of the women had some degree of blindness, 8 were physically handicapped and 5 were of unsound mind. Young mothers who were drunk or infirm were separated from their children, who were sent to orphanages (Hughes 2004:59–60). The following brief biographical notations for some of the inmates provide some insight into the misery confronting infirm and destitute women.

Alice Clifton

Admitted March 1862, aged 24

Worked as prostitute to survive; bore five children by at least four different fathers; died in 1879, aged about 41.

Hannah Dodds

Admitted 15 February 1862

Transported from Ireland on the Hooghly in 1831, she spent most of her adult life in and out of the Benevolent Asylum, Hyde Park, Tarban Creek and Gladesville Asylums.

Amelia Howe

Admitted 15 February 1862, aged 21, Jewish

Travelled from England to Melbourne on the Ballarat in 1854 under Caroline Chisholm’s Family Colonisation Loan Society. Her husband was in Cockatoo Gaol. Destitute, her ‘bad hands’ forced her to leave domestic service.

Bridget Cullen

Admitted 18 October 1884, aged 70, Roman Catholic Born Longford, Ireland. Came out as passenger with her father, a soldier. Mostly living about Sydney. Transferred from Hyde Park to Newington Asylum. Memory failing, blind, and almost totally deaf.

Ellen Howard

Admitted 27 May 1886, aged 36

Emigrant per Marlinsay 1864. Married. Has not seen her husband for 10 years. Used to do needlework in Sydney but has been paralysed for 3 years.

Joanna Hunt (née Brown)

Admitted 15 February 1862, aged 50, Roman Catholic

Arrived as convict in 1829 on Princess Royal; married Jonathon Hunt in 1840. Jailed more than 20 times for drunkenness; suffered alcoholic poisoning; died Darlinghurst Gaol in 1869.

Mary Ann Kennedy

Admitted 1862

Arrived from Ireland in 1849; spent 24 years in the Hyde Park Asylum, the last four bedridden as an invalid, before transfer to Newington in 1886. She died in 1887, aged 67.

Bridget Keys

Admitted 11 September 1868, aged 17, Roman Catholic

Born Yass NSW; partially blind and unable to work; no family to support her. Jailed repeatedly for vagrancy and her own protection.

Louisa King

Admitted 1 March 1862, aged 24

Arrived December 1858 aged 20 at Hyde Park Immigration Depot from the Forest Monarch. Epileptic; no friends or relatives in the colony. In and out of Sydney Infirmary and Benevolent Asylum suffering fits. Gave birth to son Samuel (out of wedlock) on 12 October 1861; infant died several weeks later; admitted to Benevolent Asylum ‘very ill’ and transferred to Hyde Park Asylum in March 1862.

Margaret McDonald (née Hogan)

Admitted 15 February 1862

Irish convict transported on Elizabeth in 1828; married emancipist Matthew McDonald (Earl St Vincent 1818) in 1831; After 30 years of marriage both were admitted, ill and destitute, to the Benevolent Society in January 1862. Matthew was sent to the Liverpool Asylum and Margaret to Hyde Park. It is not known but likely that they did not see each other again.

Mary Ann Murray

Admitted 18 November 1880, aged 70, Roman Catholic

Born Hull, Yorkshire. Came to colony as convict aboard Buffalo for theft. Husband deserted her 10 35years ago. Blind. Old inmate of Hyde Park Asylum. No relatives.

Ann Sheldrick

Admitted 13 March 1862, aged 18

Born in Hackney, London, arrived in NSW in 1858 with her parents and two brothers on the Stebonheath. Described as ‘idiotic and subject to fits’, she was probably the Ann Sheldrake who died in 1866 at Parramatta, aged 23.

(Source: SRNSW 7/3801, vol. C–D, p.283; vol. H–J, p.784; and vol. K–M, p.1203; Hughes 2004:60–85, 102–110; Smith 1988:111–115)

These sad stories were corroborated by City Missionary, Stephen Robins, who testified at the 1873 Inquiry. When questioned about whether the inmates were fit for work outside the Asylum (and thus undeserving of their place there), he responded:

… I could not see any women there who were able to do anything more than the work of the house. They are very old women there. There is one woman of the name Elizabeth Mills, who asked me to get her a situation. She is one of the nurses up-stairs, and she says that she does not like stopping there, and she does not know where to go to outside. She has no home, and would go for small wages if she could get them. It requires some one with strength to nurse these old women. That is the only woman whom I saw that could do anything. There was another woman of the name of Dawes. I do not think that any one could take her for a servant, because she is very deaf. They are all very old women, except the blind ones and a few that are paralyzed. It does not seem to be scarcely enough to do the work of the house. (Q2514, Public Charities Commission 1874:83)

Other women were rejected by their family members who were well able to care for them. Clara Morris was transferred from the Sydney Infirmary to the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum in 1865, and transferred to Hyde Park in 1872, around the age of 55. Although partially paralysed she was never considered insane, and attributed her long institutionalisation to the neglect of her family. She was briefly reunited with her son Frank in Queensland in 1874, but he sent her back to the Asylum in Sydney because ‘she is nothing but a drag on me … she should never have left your Institution which was & is quite good enough a home for her’ (quoted in Hughes 2004:88). The Asylums Board had no option but to exercise compassion and readmit her.

ASYLUM WORK

The Hyde Park Asylum was a place of work as well as a place of refuge. It was largely self-supporting and able-bodied inmates were responsible for ‘… all the work of the institution, including cooking, laundry, hospitals, wards, cleaning, making and repairing all clothes and house linen, &c.’ (Public Charities Commission 1874:109). According to the official reports, the only paid officers of the Asylum were the matron, the visiting medical officer, a head laundress and, in the early 1860s and (as mentioned) after 1875, a sub-matron. In 1866, Julia Williams was also on the payroll as a nurse at 12s. per week (SMH 30 August 1866, p.5).

All the remaining chores relating to feeding, cleaning, clothing and caring for up to 310 women. were undertaken by the inmates themselves, for small wages. In 1873, 21 inmates earned between tuppence and one shilling for a day’s work, as set out in the following schedule of workers at the Hyde Park Asylum:

Officers employed at the Hyde Park Asylum —

| Surgeon, Dr Ward | £122 per annum |

| Matron, L. H. Hicks | £190 per annum |

| Servants — | |

| Head laundress, Nancy Bell | 12s. per week |

| Servants selected from inmates — | |

| Head cook, Ann Bertha | 1s. per diem |

| 2nd cook | 6d. |

| 3rd cook | 4d. |

| Assistant laundress | 6d. |

| 4 assistant laundresses at | 4d. |

| Head wardswoman, M. Haggerty | 1s. |

| Assistant wardswoman, 1 at | 6d. |

| Assistant wardswoman, 3 at | 4d. |

| Assistant wardswoman, 2 at | 3d. |

| Head hospital nurses, 2 at | 6d. |

| Assistant hospital nurses, 2 at | 4d. |

| Care-taker of needlework | 2d. |

| Messenger, M. Jackson | 4d. |

(Source: Public Charities Commission 1874, Special Appendix 4, p.109)

The Hyde Park Asylum was thus comparatively cheap to run, a fact the Government Asylums Board was always keen to point out in its annual reports. In 1873, for example, the average cost per inmate was £11 16s (Government Asylums Board 1873:222). This compared very favourably to the Magdalen Asylum in Melbourne, where inmates ‘cost’ almost £25 each per annum, although they experienced similar living and work conditions (James 1969:242).

By the time of the 1886 Inquiry, and after the move to Newington, many more inmates were paid gratuities for their labour as bathwomen, dairymaids and wardswomen in the new wards. At Newington there were four bathwomen to assist inmates who could not bathe themselves, and to change the water between baths (two women shared a tub of fresh water). They worked from 9 am until 2 pm each Saturday to bathe all the women, 20 at a time in ten 36tubs (Q1246–1257, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:471).

With the possible exception of hat-making, the women were not engaged in the production or manufacture of goods for sale outside of the Asylum, unlike their male counterparts at the Liverpool Asylum. The women did not operate a commercial laundry, nor were they permitted to undertake ‘out-door needlework’, even on an individual basis (Public Charities Commission 1874:109). All their efforts were funnelled into the operation of the institution.

CONTROL

In 1862, when the colonial government assumed responsibility for providing indoor relief to the infirm and destitute, Chairman Chris Rolleston published eight pages of ‘Regulations for the Internal Management of the Government Asylums for the Infirm and Destitute’ to be hung up in each dormitory, and to be read aloud to assembled inmates once a month. These rules provided guidelines for the daily routine, meal times, procedures for handling misconduct and so on, and were similar to those found in hundreds of other almshouses and poorhouses in major towns and cities across the western world.

Such explicit rules, however, appear to have been of little use at the Hyde Park Asylum, and by 1886 there were no printed rules. This was a cause of great concern to the Government Asylums Inquiry Board investigating the operation of the Newington Asylum six months after the move from Hyde Park, but Mrs Hicks insisted that rules were unnecessary in the aged-care facility that she managed. When asked whether rules had been issued to her, she replied:

Regulations for the Internal Management of the Government Asylums for the Infirm and Destitute16

Provisions

1. The daily ration of each inmate shall be in accordance with a scale to be fixed from time to time by the Board.

2. Snuff and tobacco in small quantities may, on recommendation of the Surgeon or Matron, be allowed to such of the inmates as use tobacco, or withheld from such as misconduct themselves.

Clothing

3. Each inmate shall be provided with a complete change of suitable clothing, upon entrance, if required.

Bedding

4. Each inmate shall, upon entrance, be supplied with a stretcher, a bed, and suitable bedding.

Stores

5. Each mess shall be provided with suitable mess utensils, including a table, forms, soup vessel, dishes, plates, pannikins, knives, forks, spoons, and salts.

6. No person discharged for misconduct shall take away anything belonging to the Institution, except clothing in wear at the time; and any person absconding may be prosecuted as for a theft of anything belonging to the Institution which such person may have absconded with.

Presents

7. No present is to be made to any inmate, except through the Master or Matron.

Drink

8. No present shall consist of or include drink of any kind; and the Master and Matron are strictly charged by every means in their power to prevent the inmates from being supplied with drink, otherwise than as may be ordered by the surgeon, and are authorised, in their discretion, to search for and seize any that may have been smuggled, or may be attempted to be smuggled into the buildings, taking care to report the same at the next Meeting of the Board.

Classification

9. The sick shall be separated from the healthy, and treated in all respects as the Surgeon may direct, irrespective of these Regulations.

10. The healthy shall be divided into messes, of from eight to ten in each, and the persons appointed by the Matron to be heads of Messes shall aid at all times in keeping those associated with them to a due observance of the Regulations of the Asylum. 37

Gratuity to Heads of Messes

11. The heads of messes shall be allowed a gratuity in tea, sugar, butter, tobacco, snuff, or some article of dress, as they may individually prefer, not exceeding one shilling in value weekly.

Rising

12. The hour of rising shall be in Spring and Summer six, and in Autumn and Winter seven a.m.

Washing, Dressing, &c.

13. Half an hour shall be allowed for washing and dressing.

Airing

14. After being dressed, if the weather permit, the inmates shall, in the order of their messes, take three quarters of an hour’s airing in the Outer Domain, under care of the Master, assisted by the heads of messes.

Meals

15. Breakfast shall be on the table in Spring and Summer at half-past seven, and in Autumn and Winter at half-past eight o’clock a.m.; and Dinner at one, and Tea at half-past five o’clock p.m., throughout the year.

16. The heads of messes shall be responsible to the Matron for the becoming conduct of those associated with them at the respective Tables throughout the hour allowed for each meal.

Occupation

17. The inmates shall do all the needlework, washing, tidying, and cleansing required in the Institution; and the Matron shall apportion these several employments, as well as any other she may think conducive to health and comfort, according to the ability and aptitude of the several inmates for the work to be done; and the head of each mess shall be responsible to the Matron for the faithful performance of the labour allotted to those associated with her.

Recreation

18. The times for recreation shall be — half an hour after breakfast, three quarters of an hour after dinner, and half an hour after tea, which may be taken within the building, or in the yard, as the Matron shall direct.

Smoking

19. Smoking shall be allowed only in the place appointed by the Matron to be used for that purpose.

Bath

20. The inmates shall take the bath in messes, once in every week, and oftener if needful, generally, or in particular cases; and such bath may be hot or cold, as the Matron may think fit; and the heads of messes shall assist the Matron in seeing that this regulation is properly carried out.

Rest

21. The hour for retiring to rest shall be — in Spring and Summer, half-past Seven; and in Autumn and Winter, half-past Six p.m.

Sundays and Other Public Holidays

22. The inmates of the several denominations may attend Divine Service on Sundays and other holidays, under the care of persons appointed by the Clergymen of their respective Churches, who shall be responsible for their return to the Institution immediately after the close of the Service, and that they bring with them nothing contrary to the regulations of the Institution.

23. No work that can, in the opinion of the Matron, be dispensed with, shall be required of inmates on Sunday or any other public holiday; and ministers of religion, or members of any religious order, shall have every facility for the religious instruction of those of their own faith, within the Institution, care being taken by the Master or Matron that, in case of any visit for such purpose at the same time from persons of different persuasions, separate accommodation be provided for each.

Misconduct

24. The Master shall report to the Board any infraction of these Regulations, or any other misconduct on the part of any of the inmates, that ought to be made known to the Board. 38

Regulations to be Read Monthly

25. The Master shall keep a copy of these Regulations hung up in each dormitory, and shall read them to the assembled inmates once in each month. Application of Regulations

26. These Regulations shall apply, so far as applicable, as well to the Asylums at Liverpool and Parramatta as to the Asylum at Hyde Park.

Not for years. We had some, but they were absurd for these old people. You have to give way to them a little, and sometimes you have to punish. I was called up last night to the cancer ward [at Newington], and found two old women fighting like tigers. One said she would see the other weltering in her gore. I had to take one and put her in the Roman Catholic hospital. (Q38, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:448)

Hicks argued that routines of the Asylum were well enough understood, particularly by the wardswomen. Her position of authority was also clear: ‘I say, “Come, girls, do so and so,” and they do it, and do it well’ (Q47, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:418).

While mostly confined within the Asylum walls, inmates were permitted excursions, but as only three women were permitted leave on any given day, they had to ‘wait for their turn’ (Q2290, Public Charities Commission 1874:74). Leave was also granted under special circumstances, such as the death of a family member or friend. During the smallpox outbreak of 1881, the Hyde Park Asylum was quarantined to protect the inmates and these excursions were suspended.

The daily routine of the Asylum was flexible. Assuming it changed little following the transfer to Newington, the inmates rose at 6.30 a.m. in summer and 7 a.m. in winter — ‘It is the greatest difficulty to keep these old people in bed’ — the water was boiled for tea and sugar, dinner was served at 1 p.m. or later if the butcher was untimely, tea at 5 p.m. and then to bed shortly after. The doors to the wards were not locked; musters were taken when the matron thought it ‘necessary’, certainly not on a weekly basis — ‘you see it is a long job’ (Q88, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:448–449).

Even if the regulations were followed loosely, it is apparent that many of the women were required to work less than seven hours per day during the week, with only essential work required on Sundays.

Matron Hicks’ resistance to formal strictures was clearly out of step with some of the contemporary approaches to institutional control, as indicated by the following exchange:

92. Chairman.] Do you make any classification of the inmates? No; decidedly not.

93. Dr. Ashburton Thompson.] You mean ordinary social classification? No.

94. Chairman.] But you do classify the blind and ill? Of course; there is a classification of them and of gouty cases.

95. Mr. Robison.] What about the blind people? I find some of these the worst class we have here.

96. But you mix them among the others? Always. I find the old people very good to each other; always ready to help a blind person.

97. Chairman.] You have already said that you discharge inmates. Have you any means of keeping them in? No; they are not prisoners. A lawyer told me years ago I had not power to keep a woman in if she wished to leave.

(Evidence of Mrs. Hicks, 19 August 1886, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:449)

Ultimately this liberal view of institutional management contributed to her downfall. She was condemned by the Board as negligent in her duties to detect and prevent abuses within the Asylum and responsible for the untimely death of several inmates on their transfer to Newington in 1886. After 25 years of managing the provision of indoor relief, the government demanded a more controlled and restrictive regime. While this did not bode well for the Matron in the end, her approach that left the Institution ‘free from control or inspection’ (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:419) may have been to the liking of the inmates. While it is difficult to generalise the experience of the thousands of women admitted to the Asylum from the testimony of the few dozen who gave evidence at the 1873 and 1886 inquiries, the majority had no complaint with the matron’s management of the institution. Their criticisms were primarily directed at the state of the facilities at both Hyde Park and Newington. 39

SANITATION

Since the days of the convict occupation, ablution facilities were provided in outbuildings along the eastern wall of the Hyde Park Barracks complex, but the main building had no water or drainage facilities. At the time of its construction in 1817, indoor plumbing was a luxury for the wealthy, and certainly not a necessity for the convict inmates. While chamber pots would have been used in the main building in the evenings, outside privies would have worked sufficiently well for the 600-plus able-bodied men who lived in the Barracks.

When the last convicts were removed in 1848 the building was made ready for the reception of female immigrants and Irish female orphans. General repairs to the main building included lime-washing of much of the interior (Thorp 1980:IV:2). Several additional measures were undertaken in 1862 to improve sanitary conditions for the Asylum women. Grated apertures were installed in the walls under the windows, with openings near the ceilings in the opposite walls to ensure cross-ventilation. The walls were ‘roughly whitewashed’, and folding iron beds from the Immigration Depot were brought upstairs for the Destitute Asylum. In addition, a pump was supplied to provide fresh water for washing on Level 3 (Sydney Mail 15 March 1862, p.2).

The sanitary facilities of the Barracks, however, became a source of bitter complaint within just two years of the establishment of the Asylum on the third floor. In February 1864, the Asylum’s Medical Officer, George Walker, raised concerns about ‘the means adopted for getting rid of night soil — refuse water and other impurities from the Establishment … [and the] non Existence of proper Water Closets to the sick Wards’ (SRNSW 2/642A quoted in Berry 2001:14). He suggested that only an ‘intervention of special mercy’ had spared the inmates from ‘severe and fatal epidemics’ and noted also that visitors to the Hiring Room of the Immigration Depot complained ‘loudly of the stench and nausea’ that he described as an ‘Atmospheric Poison’. He also urged the Board to punish those inmates who were not incapacitated but who ‘from actual laziness or the baser motive of giving trouble — are in the habit of soiling their beds ‘(SRNSW 2/642A quoted in Hughes 2004:74).

A report on the drainage of the Hyde Park Asylum in April 1864 described the problem in more detail:

Another complaint is the heavy and unwholsome [sic] air in the building this must arise in a great measure from the necessity of carrying down all the night tubs in through the stair case which is in the very centre of the Building the effect of which will take some hours to allow the fetid air to be carried off.

It is proposed to erect a verandah on the end facing the east with four water closets one convenient to each dormitory, a door in [the] end of each dormitory to lead to the closet and as it is probable night tubs would still have to be used [in] a stair erected from those balconys [sic] to the ground as shown by the Plan accompanying the stair in the centre of the Building would not be required for those purposes and the Patients would have all the benefit of the fresh air on those Balconys when they would not be able to descend the stair … (SRNSW 2/642A quoted in Berry 2001:14).

In following the miasmatic theory of disease, Walker blamed the stench and foul air for causing the death of Mary Tracy in February 1864, who died from diarrhoea while afflicted with purpurea (SRNSW 2/642A, quoted in Hughes 2004:75). In 1865, George Walker again complained that:

No drainage exists in the Institution … the means of carrying off refuse Water … [from] the building seems to be very limited and imperfect. This is manifest from the Accumulation of stagnant liquid to be found in every place in the Yards …

[There is] A Cart load of Bones and a full Ash-pit within a few yards of the Cooking Aparatus … I have to suggest that these Accumulations should be cleared Away Every Week.

I am informed by the Emigration Agent that in upwards of four thousand Emigrants may be Expected this Year as on a former occasion — more than three hundred were housed on the premises in Addition to the inmates of your Institution, it is desirable to improve the means for Conducting to their health and safety before warmer weather sets in. (SRNSW 2/642A, letter dated 6 August 1865 from George Walker MD Hyde Park Asylum Medical Officer to the Chairman of the Board of the Hyde Park Asylum, quoted in Berry 2001:15).

Walker was also concerned about other aspects of the Barracks environment. He complained about the excessive noise generated by the band rehearsals of the Volunteers’ Brigade. He urged the Asylums Board to deal with the disturbance, so that the sick outcasts ‘should have some fair play and not be drummed into their coffins’ (Walker to Government Asylums Board 24 Nov 1862, quoted in Hughes 2004:69). Two weeks later the Brigade Adjutant advised that the nightly drumming would cease.

Ashpits had previously been cleared on request from the Matron in her daily book, along with other routine maintenance tasks such as chimney sweeping. In 1864 it was agreed to construct a three-storey verandah with four ‘patent valve’ water closets on the eastern face of the main Barracks building at a cost of £326 (Berry 2001:15).

40In 1865 there were further modifications, when the Colonial Architect installed ceilings in the matron’s quarters to prevent ‘leakage’ from the hospital wards above, although it is uncertain if this came from incontinent inmates or a leaking roof. The modifications were regarded as ‘very necessary’ and were estimated to cost around £60 (Thorp 1980:VI:2). In addition, a block of water closets was finally installed in 1867 behind the kitchen in the south-eastern corner of the yard, along with a separate privy for the Matron (Hughes 2004:80).

Historian Joy Hughes describes the likely scene in the Barracks compound that would have greeted a visitor at this time:

There was the cacophony of the Volunteer Rifles and band parading in their yard, the excited chatter of young female immigrants, infirm pauper applicants at the asylum door on board days or the crowds of prospective employers on hiring day, the general public awaiting hearings at the district court, smoke belching from the asylum’s kitchen and laundry, cooking smells emanating from the kitchen and the cartload of bones outside, rats amok, stagnant surface water, fetid privies, the pervasive odour of night pails indoors, washing flapping on clotheslines, the incessant clucking of the matron’s thirty-five chooks and the pathetic garden plot devoured by her goats (Hughes 2004:81).

It is evident from the historical and archaeological evidence that Matron Hicks regarded hygiene very seriously. When a new inmate was admitted, the matron insisted she take a bath, even a sponge bath if arriving late at night. Her clothing was soaked and washed, and replaced with a complete change of Asylum clothes. If the new arrival had the ‘itch’ (scabies) or some infectious skin condition, her old clothing was burnt (Q2373–2376, Public Charities Commission 1874:76). There is no evidence, however, that the women’s hair was cut short, either as a hygienic measure or as part of institutional austerity (Ignatieff 1978:144).

When the Abyssinian arrived in Sydney in 1862, Matron Applewhaite reported:

I found this Morning upon inspecting the Blankets in the Dormitories that they were much covered with vermin the [shipboard] Matron informs me that for at least six weeks the girls have not been able to wash any of there [sic] clothes consequently have scarcely a clean article to put on. (Hyde Park Daily Reports, 1 June 1862, 9/6181, SRNSW, quoted in Gothard 2001:116).

During the 19th century, taking a bath became more common and was associated with improved sanitation, good health and personal cleanliness (Eveleigh 2002:64). As late as 1880 in Sydney, most homes had little or no fixtures for indoor bathing, and piped hot water remained a rarity (Cannon 1988:238). The Asylum inmates, however, enjoyed the benefit of ‘hot and cold taps’ for their Saturday morning bath (Q2367: Public Charities Commission 1874:76). In 1865 the bathroom was fitted with three six-foot baths served with hot water supplied by a copper from the adjoining laundry (Hughes 2004:78).

Along with the inmates themselves, the inmates’ clothing was washed every week in the Asylum laundry. Nancy Bell was the Head laundress and, as noted, worked at the Asylum for more than 20 years. She was in charge of washing (and drying) not only the inmates’ clothing, but also all of the bed sheets, towels and other items as well. She used ‘soap and soda, blue and starch’ for the washing, and went through 20–30 pounds each week (Q1209–1212, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:470). In the 1870s she earned 12 shillings per week (about £31 per year), well above the wages of many female domestic servants of the era (Gothard 2001:221). She had up to 10 women helping her each day, and her status as an employee, rather than an inmate, reinforced the value placed on sanitation and hygiene within the institution.

Various items used for personal cleaning were identified in the underfloor assemblage material. These included 14 worn pieces of soap from the Asylum on Level 3, and 13 pieces from the Immigration Depot on Level 2. Hard soap was made by boiling oil or fat with a lye of caustic soda. All of the pieces preserved are small and worn, and may have been discarded as too small for further convenient use. It is probable that these fragments are the result of the bed-side sponge bathing of women unable to make it to the bath house.

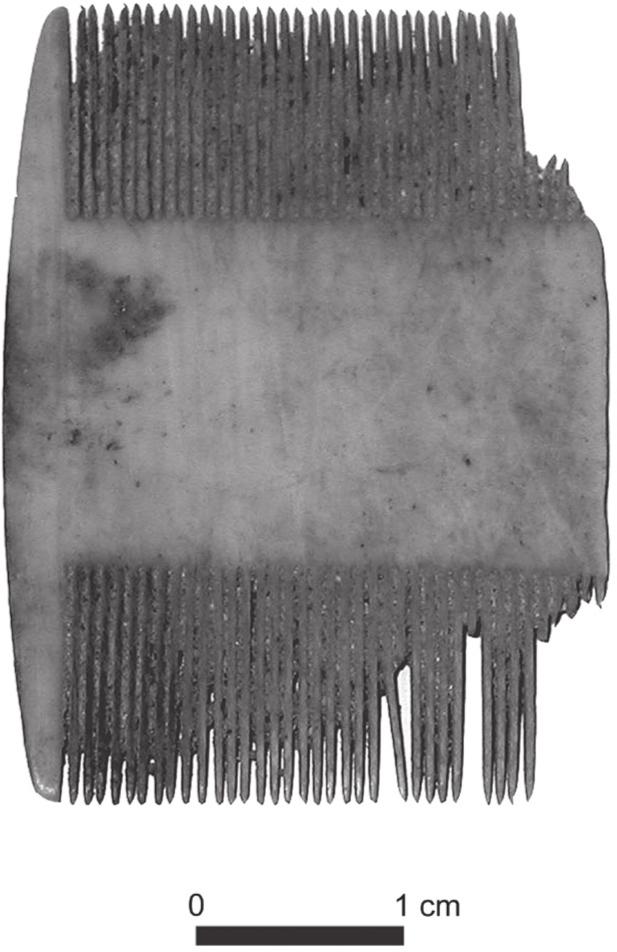

The remains of eight lice-combs were found on Level 3 and two from Level 2 (Figure 4.2). Two toothbrushes were found on Level 2 (UF27, UF8534) but none on Level 3, which is a small number and may suggest that dental hygiene was less important than bodily and hair cleanliness among the inmates, or toothbrushes were in shorter supply.17 One of the toothbrushes (UF27) was marked ‘S. Maw & Son, London, for W T Pinhey, Chemist, Sydney’. The Maw firm was the largest drug wholesaler in Britain in the 19th century, and this mark dates the brush to the 1860s (Mattick 2010:70). Pinhey was a major figure in NSW pharmacy from the 1860s to the 1880s, building up a substantial business in George Street, Sydney, from the early 1850s (Haines 1976:35, 55–57). The Applewhaites purchased medicines for

41their family from Pinhey between the years 1861 and 1864 (NSW Supreme Court, Insolvency Papers, SRNSW 2/9226, no. 8090). He may have supplied the Hyde Park Asylum and other institutions on a regular basis. A bottle of ‘Floriline’ (UF7006) for the teeth and breath came from the northern ward on Level 2.

Figure 4.2: Bone lice-comb from the Hyde Park Asylum (UF7560; P. Davies 2009).

Inmates were also active in keeping the premises clean. In 1865 the Asylums Board asked the Colonial Architect to pave the shed in which the women sat during the day as their continuous sweeping of the gravel floor had created dangerous potholes. In the same year the Colonial Architect was also requested to supply a load of ‘soft sand stone’ for scrubbing the floors — the women took great pride in their ‘snowy boards’ (Hughes 2004:78–79). A wooden scrubbing brush with intact bristles (UF34) from the southern dormitory on Level 3 may be a remnant of this activity.

MEDICINE

At the Hyde Park Barracks all pharmaceutical items and medical comforts were administered by the visiting doctor. A dispensary attached to the rear of the building was completed in April 1862, but the small timber building was to be a source of frequent complaint. In 1866, the serving Medical Officer, Dr George Walker, complained bitterly about its position and condition, barely four years after its construction:

I am compelled to request attention to the present state of the Dispensary attached to this institution. It is so much infested by rats that the destruction of Drugs and breakage of Glass is really very serious. The Animals eat the corks and upset the Bottles and the place is continually covered with their Dung. To this source of annoyance must be added that of damp which is so great that during rainy weather the walls are teaming with moisture, they are also so saturated with fluid excrement from the water closet above as to be perfectly pestilential. A Gentleman from the Colonial Architect’s Office recently inspected the place and [told] me he would recommend its being lined with Galvanized iron. But it is already sufficiently and frequently unbearably hot and means must be taken to render it water tight. The Drug Bill of this Institution need never be a very serious item if care is taken to preserve the Stock from deterioration by Moisture or Vermin. At present the destruction is considerable. Many drugs are moulded and unserviceable and not a day passes without my finding something thrown down and broken by the Rats which even eat the Ointments and Pill Mass.

George Walker MD

Medical Officer

(SRNSW 2/642A — memo dated 5 September 1866 from Dr George Walker, Hyde Park Asylum, Medical Officer, to the Colonial Architect)

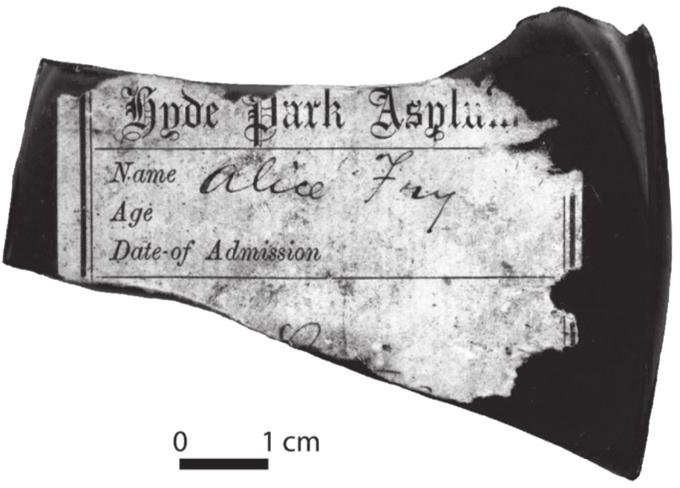

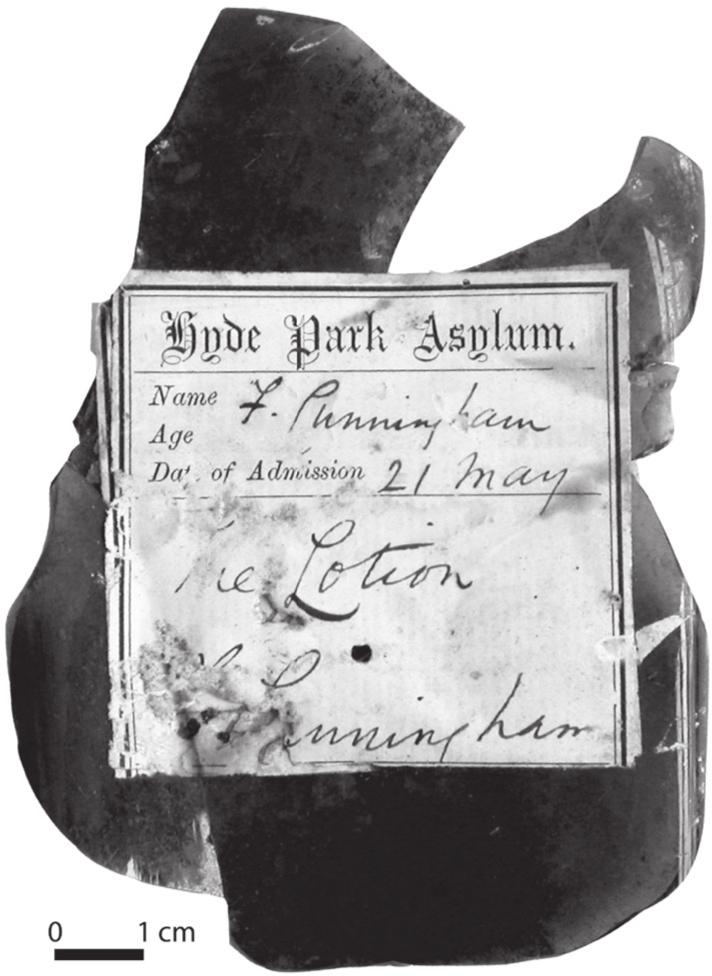

Several pharmaceutical bottles issued from the dispensary were recovered from Levels 2 and 3 of the main dormitory building, and because of the unique preservation conditions of the underfloor deposits, several have survived with their labels intact. The names of patients can still be read: Alice Fry (UF26), [Margaret?] Jackson (UF25) and F. [probably Francis] Cunningham (UF6624). Two of the bottles (UF6624 and UF3059) have two layers of labels. In the context of the institution, this is an unsurprising indication of the reuse of bottles, but one that raises questions about the hygiene standards of recycling medicinal vessels in this period. If the bottle had been sterilised by boiling, for example, the underlying label ought to have peeled off or boiled away (Figures 4.3 and 4.4).

There are several other examples of bottles with non-Asylum paper labels marked ‘Raspberry Vinegar’ (a cordial used for sore throats and coughs; UF4574), ‘Tinct[ure of] Digitalis’ (for regulating the heartbeat, treating dropsy and as a topical treatment for wounds; UF395), ‘Aconit’ (pain relief for various conditions including neuralgia, rheumatism and arthritis; UF11600) and ‘Chloroform’ (anaesthetic; UF377, UF413 and UF8351).

Most of the fragments of dispensary-issued labels were found on light-blue, oval-sectioned bottles made for pharmaceutical use that were common in colonial Australia at this time. Others, such as the Alice Fry label, were found on dark olive green, square-sectioned bottles typically associated by historical 42archaeologists with gin or schnapps. Square case bottles were a standard part of the ‘kit’ of military surgeons in the early 19th century (Starr 2001:43–44), and the Barracks examples may be a holdover from this practice. Whether Fry’s prescription happened to be spirits or, when short of bottles the Medical Officer used whatever vessels were available at short notice, or ‘Gin/Schnapps’ bottles were commonly used for pharmaceutical concoctions, is uncertain. It is known, however, that some brands of schnapps including Udolpho Wolfe’s popular ‘Aromatic Schnapps’ (4 examples of which were found on Level 3), were promoted at this time for its medicinal properties (Vader and Murray 1975:39–40).

Figure 4.3: Hyde Park Asylum Dispensary Label for Alice Fry on a dark olive-green gin or schnapps bottle. Alice Fry died on 5 February 1868, aged 56 years, of a uterine tumour (UF26; P. Davies 2009).

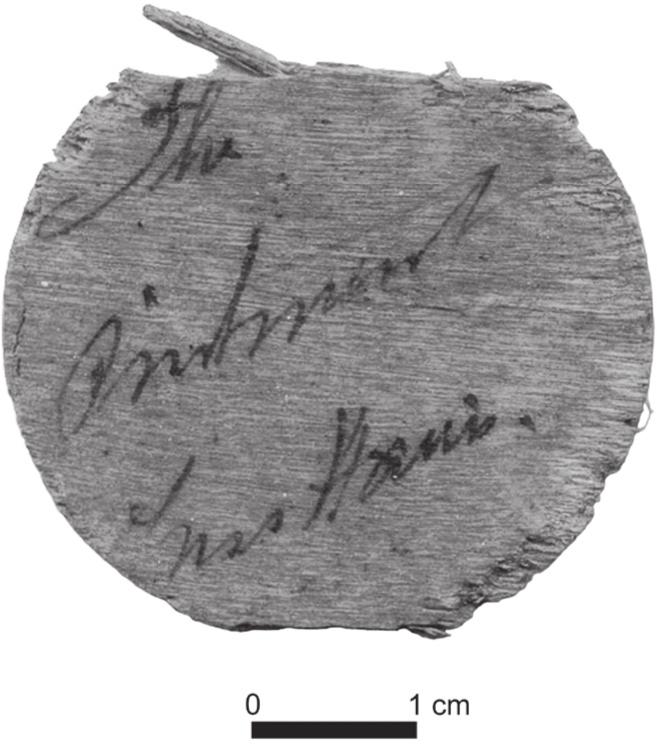

There is, however, other more concrete evidence for ‘making-do’ when it comes to dispensing medicines. A small wooden disk, 40 mm across, is marked ‘The Ointment / Mrs Harris’ in brown ink (UF17601; Figure 4.5). It was probably from a circular matchbox or some other small, light, disposable box, and seems to have been used as a label in the absence of a paper one, possibly tied or glued to the bottle.

In addition to the medicines issued by the Dispensary, there was evidence of prepared, commercial remedies including a laxative tonic, ‘Dinneford’s Solution of Magnesia’ (UF4520) and, among the paper fragments, two packets of ‘Cockle’s Antibilious Pills’ for settling the stomach (UF4233, UF17281). A bottle of ‘Barry’s Tricopherous’ skin and hair ointment came from the large southern dormitory on Level 3.

It is known from the parliamentary inquiries and the Daily Reports that sick inmates were prescribed alcohol and nourishing meals in addition to medicinal treatments. ‘Grog’, for example, was an alcoholic mixture of rum and water. Women and children in the Immigration Depot were given arrowroot, milk and rice. Traditional treatments were arranged by Matron Hicks. The Day Book entry for 8 July 1864 reported that a mustard poultice had been applied to immigrant Margaret Dailby who complained of a sore throat.

Figure 4.4: Hyde Park Asylum Dispensary Label for ‘F Cunningham’ on a gin or schnapps bottle. Francis Cunningham was part of the first intake of inmates in 1862 (UF6624; P. Davies 2009).

The parliamentary inquiry of 1886 revealed that inmates too were responsible for dispensing medicines in the sick wards, and to the great dismay of the Board of Inquiry, some of these women were illiterate or had limited reading skills. In the cancer ward, for example, Annie Mack could read ‘printing’ but not the hand-written dosage instructions, while Ann Simpson could not read or write at all (Q2014, Q1616, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:484, 477). Both relied on the recall of instructions given to them on the doctor’s weekly visits, or the assistance of literate staff such as Miss Applewhaite.

Figure 4.5: Wooden disc with hand-written identification: ‘The Ointment / Mrs Harris’ (UF17601; P. Crook 2003).

The medicines were stored on the mantelpiece in each ward and some patients were able to take their own dosage when required, sometimes with serious consequences. Ellen Purnell, who could read but not write, mistakenly took a poisonous lotion instead of medicine, apparently by accident rather 43than inability to read the label (Q2403, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:493).

| Level 2 | Level 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bottle fragment | 116 | 335 | 451 |

| Bottle label | 7 | 38 | 45 |

| Medicinal packet | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Vial | 5 | 12 | 17 |

| Total fragments | 130 | 387 | 517 |

Table 4.1: Fragments of pharmaceutical items in the main building.

The distribution of pharmaceutical items across Levels 2 and 3 suggests that sick wards probably operated on both floors at one time, with a greater use of Level 3 for remedial purposes (Table 4.1).

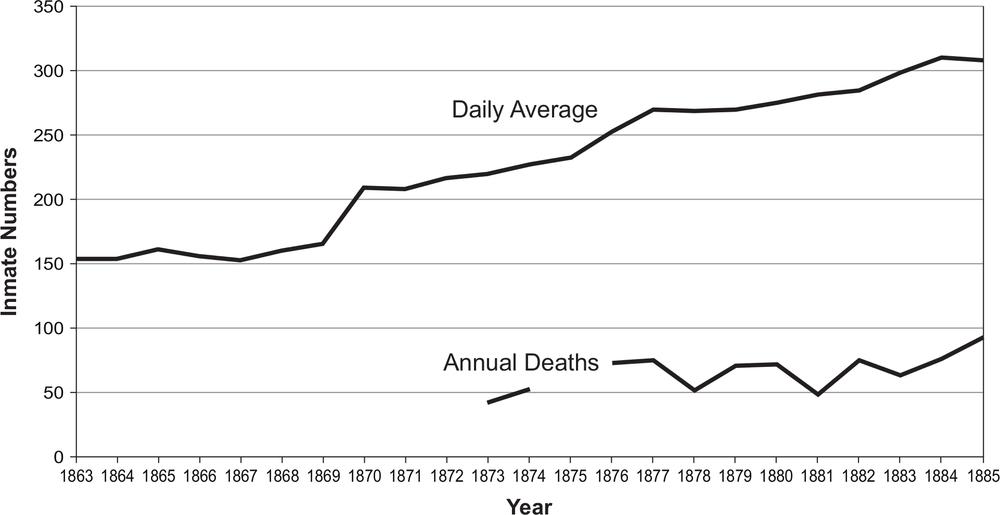

DEATH AND BURIAL

As expected in an institution of its kind, many women died while they were inmates at Hyde Park Asylum (Figure 4.6). Annual Reports of the Government Asylums Board from 1873 included summary information on the number of deaths, while from 1875 the causes of death were also reported. Conditions such as ‘Brain disease’, ‘Senile decay’, ‘Diarrhoea’ and Phthisis (tuberculosis) claimed the most lives, revealing the limits of medical diagnosis in this period, and the suffering that many of the women endured.

Mrs Hicks found the inmates ‘very good to the dying and the dead’. Every corpse was bathed and dressed in a clean chemise and nightcap, for which the oldest clothes were specially put aside. There was no dead house, and the deceased were placed in coffins in the hospital ward and carried out by an undertaker. They were buried quickly, sometimes on the same day as their death — particularly in the case of infectious diseases. Some remained at the Asylum in their coffins or laid out behind screens for several hours or sometimes overnight (SMH 30 August 1866, p.5; Hughes 2004:197). If unclaimed by relatives, the women were buried in pauper graves at government cost.

In 1866, Richard Switson, the undertaker paid to provide coffins to the Asylum and carry them to their respective places of burial, was found guilty of fraudulently burying two Roman Catholic inmates in one coffin (with the corpse of an unknown infant) and ‘charging for two’. He was also accused of failing to bury three Protestant inmates having claimed they were buried at Camperdown, although no record of their burial was known. The evidence presented at trial (SMH 29–31 August 1866, pp.5) provides yet another sad tale of the ill-treatment and mismanagement of pauper women, even in death. It also provides some interesting detail about the operations of the Hyde Park Asylum:

Figure 4.6: Daily average of inmate numbers at the Hyde Park Asylum, and annual death-rate (source: Hughes 2004:218).

Lucy Ann [sic] Applewhaite, being sworn, deposed: I am matron in the Hyde Park Asylum, the following paupers were inmates — Ann Miller, Ann Terry, Priscilla Pritchard, Mary Coffee, and Margaret Williams, persons of that name died in the asylum; I saw their dead bodies there; the nurses, as usual, placed them in coffins, and the defendant, to the best of my belief, brought the coffins; … when the body of Pritchard was put into the coffin, she having died of mortification18, I stood at the bottom of the stairs whilst the coffin was being nailed down; … there were two women lying dead at the same time — Rose Kelly and Priscilla Pritchard; Kelly was in her coffin, and defendant promised to come back with another coffin for Pritchard; … going up-stairs I told defendant to be very particular about them, one being a Roman Catholic and the other a Protestant, and said, “Mind you mark the coffins”, he said, “all right”; we put a cross in black lead pencil on the coffin of the Roman Catholic, some short time after he returned and brought a coffin for Pritchard; I made the mark on the coffin of Kelly with a little pencil mark, and the defendant said there would be no fear of burying them together …

44Somewhat gruesomely, the testimony of inmate and nurse Ann Jeffreys regarding the exhumation of Mary Coffee and Margaret Williams from the Roman Catholic Burial ground, Devonshire Street, on 12 August 1866 (one month after their burial) provides rare evidence of the medical afflictions and personal appearance of these inmates:

I was present at the exhumation of a coffin at the Roman Catholic Cemetery a fortnight last Sunday; I saw the coffin taken from the ground, and when the lid was raised I saw the bodies of two women and there was a bundle at the foot of the coffin … I recognised the two women, the top body was that of Mary Coffee, and the lower one that of Margaret Williams; one body was laid above the other; I recognised Coffee, because she had quite a moustache and beard; and Williams because she was buried with her arm across her stomach, and she had one knee bent up; I saw their faces distinctly; I should not know it was Coffee except for the beard and moustache; I recognised the clothes she had on; I put her in the coffin myself in the same clothes; I had known Coffee for about three years in the Asylum, or it might be more; she was a very old woman, I do not think she was quite 100, but upwards of 90; I cannot say exactly; she was a shortish woman, and stout, but not very heavy, I have not the slightest doubt this was the body of Mary Coffee; I saw the face of the body I recognised as Williams; I have no doubt it was Williams’ body; I have known her six years, I believe Coffee died of old age, she did not die of dropsy; she was two years under my charge and care. (SMH 31 August 1866, p.5)

Mary Coffee is registered as 101 years on her birth certificate. She was a short, stout woman with ‘quite a moustache and beard’. Williams had suffered as a cripple for many years and in death, her coffin had to be ‘made large’ to accommodate her bent knee, which is probably why the undertaker, Switson (or his ‘man’ as Switson argued), saw fit to bury three paupers in it.

Switson was sentenced to eighteen months hard labour in Sydney Gaol. After 1867, deceased inmates from the Asylum were interred in the Rookwood Necropolis in consecrated grounds of the various denominations (Hughes 2004:90).

VISITORS AND SPECIAL OCCASIONS

Women in the Asylum and Immigration Depot were generally confined within its walls, unless they were granted permission to leave or were sent on errands. They were not, however, entirely cut off from the outside world. The Hyde Park Asylum was accessible for visits by friends and relatives of the inmates, and there were many visits by well-meaning individuals and organisations, including the Ladies Evangelical Association, the Sisters of Mercy and the Flower Mission Ladies (SMH 1 February 1882). While the motivations for these visits were largely religious, and arguably political advocacy, they also provided an important distraction from the daily routine for the Asylum inmates.

At the 1886 Inquiry, one of the visitors on the Ladies’ Board, Miss Eleanor Bedford reported that many inmates disliked the isolation of the new Newington Asylum:

They said they had never been so wretched at Hyde Park; that Hyde Park was a paradise to this; there the old women had friends who could visit them easily. (Q2322, Government Asylum Inquiry Board 1887:490)

Eliza Pottie was also a member of the Ladies’ Board, and from the 1870s onwards she undertook charity work for destitute women and children in Sydney. By the 1880s she was one of Sydney’s leading evangelicals, distributing religious tracts to children and working for the welfare of women, girls and animals (Dickey 1994:312–313). She often visited the Hyde Park Barracks Asylum, and her testimony to the Newington Inquiry was highly critical of conditions at the institution (Q2354, Government Asylum Inquiry Board 1887:491–492).

Distinguished travellers also visited the institution. The sisters Rosamond and Florence Hill, for example, published an account of their visit in their book What We Saw in Australia, published in London in 1875. They described the Hyde Park Asylum as:

… standing on high ground in a beautiful situation, and in one of the fashionable quarters of the town … It contains more than two hundred inmates, the greater proportion of whom are old or sick. The few young women are either blind, cripple, or idiots, for whom there is no other refuge. As the asylum is in the metropolis, it does not require a resident medical officer, but is managed by the matron, Mrs. Hicks, whose qualifications 45are as remarkable as those of Mrs. Burnside [Matron of the Parramatta Asylum]. She and one laundress are the only [paid] officers in the institution, the whole of the work, nursing included, being performed by the inmates, who also make all their own clothing, with the exception of boots and shoes.

The house affords good bathing accommodation, and the old women have their warm baths regularly … At meals the old women are divided into messes of eight, the strongest being chosen captain of the mess. She fetches the dinner, and, we conclude, carves for her mess-mates; but every woman pours her own tea. Small gratuities are given for the work performed, as at Liverpool, and the women looked as cheerful and happy as the old men there. Their annual cost per head is only 10l. 16s. 11½d. (Hill and Hill 1875:336–337)

It is also possible that Marie Rye, who promoted female emigration from England, visited the Hyde Park Barracks in 1865 during her trip to Australia and New Zealand. Rye wrote to Florence Nightingale about conditions in Sydney’s institutions, including the Infirmary and Gladesville Lunatic Asylum, and she is unlikely to have missed an opportunity to inspect the Immigration Depot as well (Godden 2004:52).

Another well known visitor to the Hyde Park Asylum was the prominent local merchant and philanthropist Quong Tart. In later years his wife recalled:

On one occasion, in the year 1885, he was asked, along with others, to speak at a treat given to the inmates of the Asylum for Women at the head of King Street. Speaking of that address a daily paper of that day said, “Mr. Tart’s speech differed from that of others in that while they spoke high-sounding words, he determined to make the treat an annual affair,” and this he afterwards attempted to do, not only for the unfortunates of that asylum alone, but for the indigent poor in the benevolent asylums of the State. How far he succeeded in this attempt may be seen by casually scanning the large list of institutions where every year such festivals were held. (Tart 1911:25)

Tart maintained his relationship with the Asylum after its move to Newington:

“When nearing the wharf on the day of the feast of the inmates of the Newington Asylum,” says “The Echo” of 16th October, 1888, “Mr. Tart seemed suddenly seized with a fit; he waved his arms and rushed about the deck, shouting out to the old women how glad he was to see them. The moment they recognised who it was, the look of joyous gratitude that came over those wrinkled faces was worth going over from Sydney to see. The moment he reached the enclosure he was surrounded by the poor old creatures, who danced round and clapped their hands like children in a pantomime. ‘Ah! God bless you for a good ‘un Mr. Tart!’ ‘The Lord preserve you and yours, dear Mr. Tart!’ ‘Have you brought Mrs. Tart?’ and dozens of similar ejaculations, and when he told them Mrs. Tart would be there directly with the little ‘Tart,’ which they mustn’t eat, their enthusiasm knew no bounds.”

“Long time since I saw you!” “Now, you have a good bit of fun to-day, but don’t flirt with the gentlemen from Sydney!” “How are you, Mary? I must have a dance with you when Mrs. Tart goes away,” and similar expressions, with a kindly word for all, as he wended his way amongst them, raising his hat each time he shook hands with one of them, with as much grace as he would have done to his own wife.

It was no unusual sight on feast day at the asylums for his name to be blazoned forth with mottoes expressing welcome and thankfulness — “A Glorious Welcome to Quong Tart and His Friends!” “Vive Quong Tart le Grand!” “Will ye nae come back again?” were among the decorative mottoes at the Parramatta Asylum in 1886. (Tart 1911:26)

On such occasions the women were issued with ‘new dresses and aprons and the like’ (Q3213, Governments Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:508). Religious and public holidays were also honoured in the Asylum with special feasts:

QUEEN’S BIRTHDAY was celebrated at the Hyde Park Asylum on Wednesday with the usual tokens of re-joicing. The old ladies were regaled with a bountiful dinner of roast beef and plum pudding, washed down with a glass of ale. A harper and violinist were afterwards introduced, to whose music some of the old girls danced jigs as merrily as they would have done some 50 or 60 years ago. The whole party seemed to enjoy themselves greatly, and were loud in their praises to the matron (Mrs. Hicks) and the Government, to whom they were indebted for the treat. (SMH 29 May 1882, p.5)

These banquets were important events for the inmates of the overcrowded Hyde Park Asylum which Frederic King described, in 1886, as unsuitable for the care of the old women, there being:

Little room for recreation, and the wards are badly adapted for the healthy accommodation of large numbers of aged, and in many cases bed-ridden paupers. (Government Asylums Board 1876:928)

The overcrowding of the inmates was also observed by Lady Carrington, wife of the Governor of New South Wales, who visited the Asylum in 1886, a few 46weeks before the move to Newington. The vice-regal couple displayed an interest in helping the poor during their five-year term in Sydney, banqueting a thousand poor boys and establishing the Jubilee Fund in 1887 to help to provide relief for distressed women (Hughes 2004:177; Martin 1969). Lady Carrington:

… [visited] some of the old women; with some of these she shook hands, and said a few kindly words. Amongst the poor creatures seen were a few who were so enfeebled that they were unable to leave their beds, and in these Lady Carrington seemed to be particularly interested. The inmates of the asylum, who were ranged in the yard, manifested their pleasure at seeing the lady of the Governor by giving hearty cheers. (SMH 21 January 1886, p.9)

OFFICIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE RECORDS

Documentary evidence of government administration was found among the artefact assemblage, and included items from other institutions that shared the Hyde Park Barracks with the Asylum and Immigration Depot, or occupied the main building after its conversion to government and legal offices. The latter category includes documents from the NSW Parliamentary Library (UF4279), fragments from the Government Gazette, and numerous fragments of blue forms from the 1871 Census. The Census Office is known to have occupied rooms in the main building (probably on the ground floor), much to the annoyance of Matron Hicks.19

Several documents derive from the Master in Lunacy’s office, including scraps of notepaper and part of a file for ‘Isabella Hughes, Lunatic’, dated 1891, relating to monies owed to the government (UF135). Judicial stationery included an envelope from the District Court of NSW (UF8315) and miscellaneous papers from the Supreme Court, along with a typed document addressed to the Equity Court (UF4303). A pink paper fragment (UF17749) from the City Coroner related to ‘children’, while two legal documents dated 1890 concern an Eliza Skinner (UF208 and UF209).