5

DAILY LIFE IN THE ASYLUM

COMMUNAL MEALS

The women of the Asylum sat down to three simple, monotonous meals every day. Breakfast and supper consisted of dry bread and black tea, while the main dinner meal was served around 1 pm. This generally included boiled meat and a watery vegetable soup. The daily allowance for each woman was half a loaf of bread, one pound of beef or mutton and one pint of tea. Inmates could help themselves to dripping from the kitchen to spread on the bread, but only women in the hospital wards were permitted milk in their tea. The tea ration could also be supplemented by gifts, rewards or gratuities for daily work, or by purchasing or exchanging supplies with other inmates.

The women were organised into messes comprising 8 inmates and the strongest woman among the group was appointed the ‘captain’. These women carried in the loaves of bread, the boiled beef or mutton ‘hot in the joint’ and the pot of tea, for breaking, carving and pouring amongst the mess. According to Mrs Hicks, the women preferred boiled to roasted meat which was reserved for ‘special days’ when large legs of roast mutton were served20 (Q2321–2347, Public Charities Commission 1874:75).

The Asylum may have had the use of the large southern room on Level 1 as a dining room (Hughes 2004:57). A kitchen was located at the south-east corner of the main building, and this was replaced with a larger complex by 1870 (Spiers 1995:125; Varman 1993). The kitchen was thus convenient to the dining room for the Asylum women.

Large quantities of cutlery were found in the subfloor cavities on Level 3, including forks, spoons, teaspoons, serving spoons and bone- and wood-handled knives (Table 5.1). There was also an unusual concentration of 19 well preserved cutlery items found under the floor below a window in the large southern dormitory in the Asylum, the explanation for which remains uncertain (JG3 JS14). The presence of cutlery in the dormitories may indicate that some bed-ridden women ate their meals in bed. Only 15 cutlery items, however, were recovered under the floor on Level 2, which probably reflects the fact that the women from the Immigrant Depot took their meals in the large northern room down on Level 1.

| Cutlery | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fork | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Knife | 6 | 24 | 30 |

| Serving spoon | – | 7 | 7 |

| Spoon | 1 | 13 | 14 |

| Teaspoon | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| Unidentified | 4 | 16 | 20 |

| Total fragments | 15 | 75 | 90 |

Table 5.1: Distribution of cutlery items on Level 2 and Level 3.

It is very unlikely that the Applewhaite-Hicks family shared meals or utensils with the Asylum women. A kitchen range, for example, had been installed in 1848 in the Matron’s apartment on Level 2. The family shared this with the sub-matron and the immigrant ship’s matron before her departure. Its constant use over the years caused it to fall to pieces and it was replaced in 1866 (Hughes 2004:79). Mrs Hicks probably had her own china service and the family most likely ate in their quarters, or perhaps used the Asylum or Immigrants’ dining room off-schedule to the main meals. The Matron also kept her own animals, including three dozen chickens and several goats, which destroyed the small garden in front of the Hyde Park Barracks, while her cow was de-pastured in the Domain (Q3927, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:527). These animals may have been used to supplement Asylum rations and keep costs down.

The diet of the Asylum women remained basically unchanged for 24 years, except for ‘special days’ and the occasional feast (see following section). In 1885 Frederic King, the Manager of Government Asylums, defended the Asylum’s meals as:

… suitable food for old and worn out persons … it would be difficult to find a more health giving dietary … [I]t has not been attempted … to supply luxuries to people who, even in the days of their health and independence, were never accustomed to them. Sound, wholesome, and plenty of food has been given, and there is no fair ground for complaint by the inmates. (Government Asylums Board 1885:720)

48Surveys of dietary scales at other asylums in New South Wales and the other colonies, however, indicated that greater effort was made to provide more appetising food. At the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum, for example, inmates had porridge for breakfast along with bread and tea, with food such as pies and fish donated at times by local traders. Catholic meatless Fridays were also accommodated with rice pudding, while special diets were available to those under medical care, and included whisky and wine, milk, butter, eggs, and arrowroot (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:708; Kehoe 1998:43–45). Queensland destitute asylums served gruel two mornings a week, along with a variety of dishes including Irish stew, corned beef, and boiled or roast meat (Hughes 2004:89). Meals at New South Wales lunatic asylums were also more varied, with roast mutton or beef or meat pie or Irish stew, and a wide variety of vegetables such as pumpkin, tomatoes, artichokes, onions, leeks, carrots and cauliflower (Hughes 2004:89–90). Meals at the Adelaide Destitute Asylum, however, were much the same as those at Hyde Park, with boiled mutton, soup and tea served every day (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:710; Hill and Hill 1875:144).

Nevertheless the dining arrangements at the Hyde Park Barracks were far better than those at the Parramatta Asylum for men, where soup and boiled meat was intentionally served cold and the soup — reported to be made with rotten meat — was distributed from slop pails and served in cups that were reused for tea without washing (Q2332–2338, Public Charities Commission 1874:2, 75).

In her evidence to the 1873 Inquiry, Mrs Hicks reported that the women of the Asylum sat down to eat with tin plates (probably versatile soup plates) and cups, each with their own knives and forks, and soup was served from ‘nice soup-tureens’ — probably of the tin or enamel variety, although possibly from tureens of utilitarian whiteware china.

Asylums, orphanages and other institutions in the United Kingdom and the United States provided crockery for their inmates (Dawson 2000; Hughes 1992; De Cunzo 1995:50–74). In the 1870s, and in the cases of the Craiglockhart Poorhouse in Edinburgh, the Royal Edinburgh Asylum and the Wanstead Infant Orphan Asylum in London, crockery was made especially for, and marked with the names of, these institutions.

The Wanstead Asylum crockery was plain with matching copperplate script ‘Infant Orphan Asylum Hall’ on various plates, mugs and slop bowls that were dumped in Eagle Pond in north-east London in the 1940s — some 70 years after the vessels were first produced (Hughes 1992:386). The Craiglockhart Poorhouse and Royal Edinburgh Asylum crockery were designed in the typical form and decoration of later 19th-century ‘hotel ware’, having red and blue band-and-line borders at the rim and coats of arms. The Craiglockhart wares are also marked with a ribbon banner ‘CITY OF EDINBURGH POOR HOUSE’ and the mugs had reinforced handles typical of hard-wearing, cheap crockery of that period (Dawson 2000: section 3.3). The Royal Edinburgh Asylum vessels appear to be of slightly better quality — a key concern of the Asylum Board. In 1877, they approached W. T. Copeland & Sons to produce the Asylum’s crockery, ‘hitherto supplied with articles of a somewhat inferior kind’, for the ‘90 to 100 high class patients and … about 650 patients of a humbler rank’ (quoted in Dawson 2000 and Crook and Murray 2006:62).

It was not simply the presence of ‘high-class’ patients that compelled all of these institutions to supply china rather than tin or enamelled ware — the infant orphans and poorhouses too had crockery, albeit of a more roughly finished kind. In London and in Edinburgh, these boards of management were much closer to the source of crockery production (in the Midlands of England and also in Scotland) and could arrange orders with greater ease than colonial boards of management might have done. Factor in the cost of shipping and the difficulty a feeble inmate might have lifting heavy crockery, and the use of enamelled tin serving ware at the Hyde Park Barracks was quite reasonable.

The ceramic assemblage from Levels 2 and 3 of the main building is scant, comprising just 0.3% of the assemblage by fragment count. Of the recorded ceramic sherds from Levels 2 and 3, 38% are estimated to be less than 10% complete. This leaves us with a very small assemblage, too fragmented to pursue a substantial analysis of functional categories, or identify the kinds of ceramic vessels we might expect in institutional or infirmary accommodation, such as pap boats, sick feeders or bouillon cups (for drinking broth or beef tea), vessels which may well have been supplied in enamel and tin wares.

The remains of numerous glass condiment bottles suggest that various food additives were available to the women as well, including Worcestershire sauce and malt vinegar. A bottle preserved with a paper label from Crosse & Blackwell of London (UF2367) once held pickled onions. A total of 177 fragments from Level 2 represent a minimum of five condiment bottles, while 371 fragments from Level 3 represent a MNV of 11.

SMOKING

Smoking was another small treat enjoyed by many of the Asylum women, an activity permitted within the Asylum under certain conditions. The 1862 Regulations specified that small quantities of snuff and tobacco could be made available to the inmates by the surgeon or matron. Lucy Hicks provided four figs of tobacco each month to those inmates who wanted it, while clay pipes may have been donated by visiting City Missionaries. Tobacco was also 49traded for goods and favours within the Asylum. Mary Wright, for example, was an elderly blind inmate who exchanged ‘a box of matches or a bit of tobacco’ for someone to lead her around (Q2279, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:488).

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Rear yard | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay pipes | 2,090 | 302 | 1,006 | 516 | 3,914 |

| Matches | 17 | 2,070 | 3,320 | 5,407 | |

| Matchboxes | 1 | 25 | 417 | 433 | |

| Total fragments | 2,108 | 2,397 | 4,743 | 516 | 9,754 |

Table 5.2: Fragments of all smoking items from specific areas at the Hyde Park Barracks.

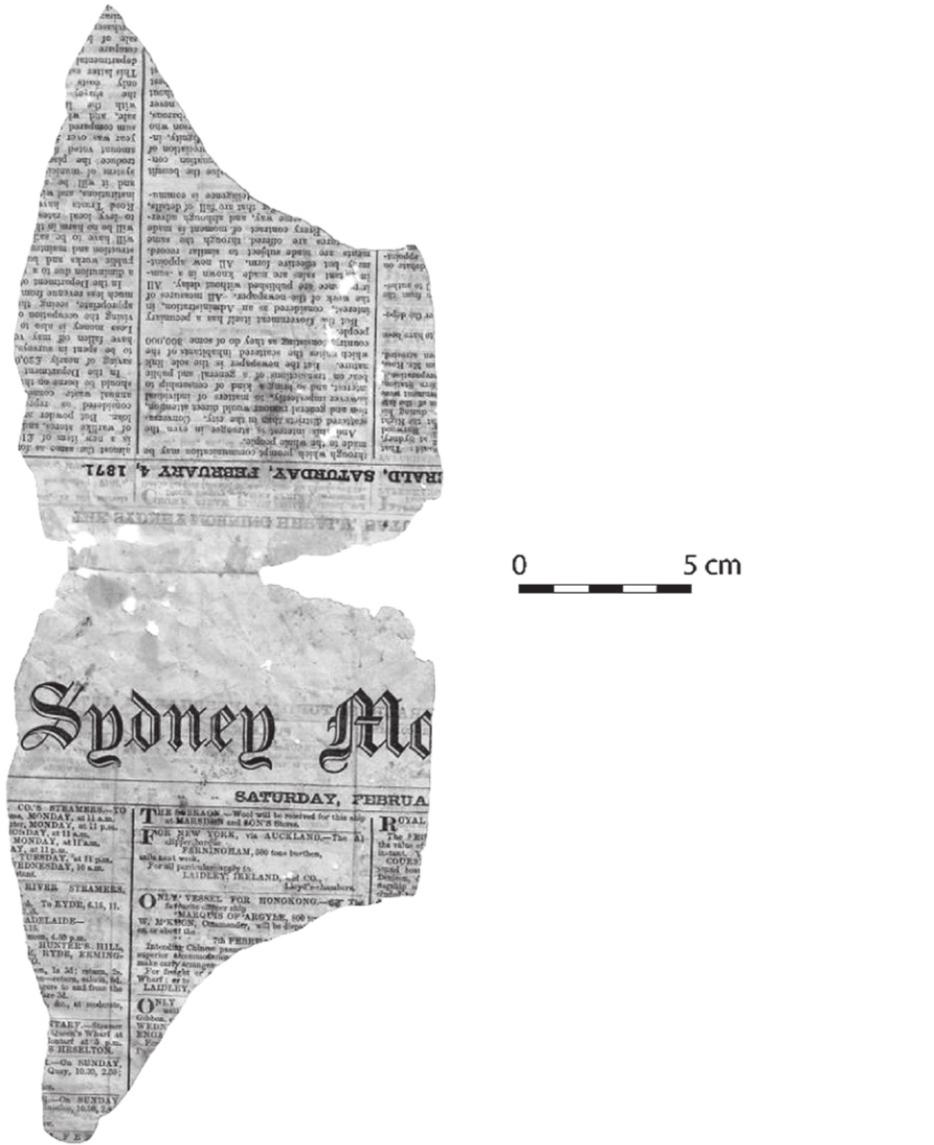

Due to the substantial risk of fire the Asylum women were supposed to smoke in designated areas. Inmates and officials had a front-row view when St Mary’s Cathedral, located only a short distance to the south of the barracks, burnt to the ground in 1865. Most of the internal architecture of the Barracks was timber and the roof was made of wooden shingles, while the clothing and bedding of several hundred women were also highly flammable, as were the cotton scraps they spent their days sewing. The underfloor spaces were a tinderbox of textiles, newsprint and other paper — it was fortunate that no major fire ever broke out.

The barracks’ large windows admitted good natural light during the day but there were only a few fireplaces to provide feeble light after dark. Authorities installed gas lighting in 1866, with padlocks fitted to each lantern, to prevent the women from lighting up at night and smoking their pipes in bed ‘after the hours of Midnight’ (Government Asylums Board, quoted in Hughes 2004:79). The recovery of thousands of used matches from the underfloor spaces, however, suggests that smoking persisted in the dormitories. In the absence of historical or archaeological evidence for the use of candles, many of the matches may have been struck simply to provide a few moments of light in the dark.

Clay tobacco pipes from the Hyde Park Barracks represent one of the largest known archaeological collections from an institutional site in Australia. The assemblage of 4,111 clay pipe fragments includes 1,006 pieces from Level 3, 302 from Level 2, and 516 fragments from the rear (eastern) yard. More than 2,000 fragments came from excavated deposits on Level 1 of the main building and date from across the 19th century, including examples securely dated to the convict period. In addition there were more than 400 matchboxes and thousands of wooden matches, many of which may have been used for lighting lamps, candles or fires, as well as for smoking (Table 5.2). The distribution of this material provides important insights into the habits and recreation of the Asylum inmates, and their use of spaces within the institution.

Smoking was meant to be restricted to specific places within the complex to prevent fires. Although there is no formal record of where such places were located, the concentration of clay pipes on the Level 3 stair landing21 suggests this was a designated area. The overall distribution of pipes across the complex and in parts of the dormitories themselves reveals the scale of smoking within the Barracks and suggests that tobacco consumption was a pervasive element of everyday life in the institution.

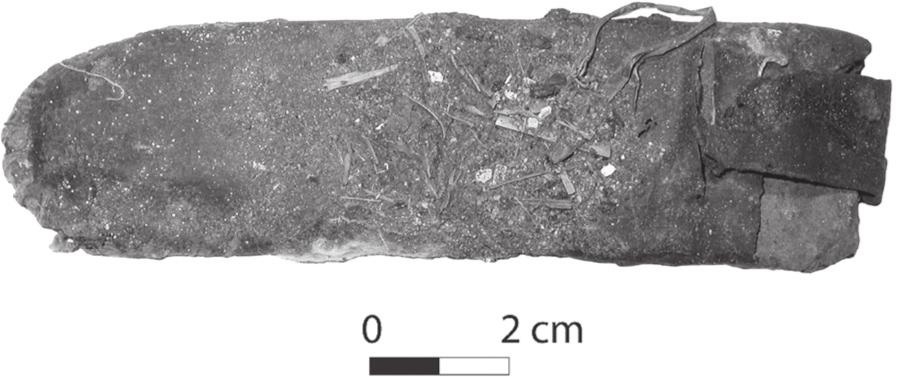

Figure 5.1: Well preserved and heavily stained clay pipe from Level 3 with wad of tobacco stuck in bowl (UF3269; P. Davies 2008).

The five most commonly stamped pipes of this period bore the marks of pipemakers Duncan McDougall and Thomas Davidson of Glasgow, Charles Crop of London and tobacconist Thomas Saywell and warehousemen Myers & Solomon of Sydney (Table 5.3). With the exception of Myers & Solomon, these and many other common pipes were also present in the archaeological record of the Sydney Night Refuge in Kent Street (Carney c.1991). The Night Refuge, run by the Sydney City

50Mission, relied entirely on subscription (Carney and Kelly 1991:25) and the donations of wealthy Sydney merchants. It is very likely that some of the pipes in that assemblage were donated in this way, and conceivable that similar donations were made to the female inmates of the Hyde Park Asylum, if not via Matron Hicks, then by regular visitors including City Missionaries.

| Maker/Distributor | Location | Date range | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Rear yard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *William Aldis | Sydney | 1839–1868 | 4 | |||

| [Desiree] Barth | London | 1855–1890 | 1 | |||

| William Christie | Glasgow | 1857–1891 | 3 | 1 | ||

| William Christie | Gallowgate, London | 1860–1876 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| William Cluer | Sydney | 1802–1846 | 11 | 4 | ||

| Charles Crop | London | 1856–1924 | 4 | 1 | 4 | |

| Thomas Davidson | Glasgow | 1862–1911 | 26 | 6 | 12 | 24 |

| William Davis | 1810–1840 | 1 | 1 | |||

| *Hugh Dixson | Sydney | 1839–1904 | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| Joseph Elliot | Sydney | 1828–1840 | 52 | 17 | 1 | |

| Samuel Elliott | Sydney | 1828–1840 | 25 | 8 | ||

| John Ford | Stepney | 1810–1909 | 1 | |||

| B Jacobs | London | 1 | ||||

| J[onathon] Leak | Sydney | 1822–1839 | 6 | 1 | ||

| *Thomas ‘Dan’ Lowrey | Dublin | 1879–1897 | 1 | |||

| MG | 1820–1860 | 7 | 3 | 4 | ||

| MPP | 1810–1840 | 28 | 14 | |||

| Duncan McDougall | Glasgow | 1846–1891 | 95 | 13 | 42 | 38 |

| P McLean | South Tay Street, Dundee | 1861–1883 | 2 | |||

| David Miller | Liverpool | 1870–1880 | 12 | 2 | 1 | |

| *Thomas Milo | Strand, London | 1852–1870 | 1 | |||

| Anson Moreton | Sydney | 1829–1840 | 1 | |||

| John Moreton | Sydney | 1822–1847 | 1 | |||

| William Murray | Glasgow | 1830–1861 | 1 | |||

| H N[athan] & Co | London | 1 | ||||

| *Myers & Solomon | Sydney | 1863–1927 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| *Edwin Penfold | Sydney | 1855–1890 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Thomas Reeve | Hampstead, London | 1828 | 2 | |||

| Reynolds & Blake | England | 1 | ||||

| *Thomas Saywell | Sydney | 1865–1905 | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| Sippel Brothers | Sydney | 1864–1901 | 1 | |||

| William Southern & Co | Broseley, Shropshire | 1850–1900 | 1 | |||

| F S Sparnaay & Son | Rotterdam | 1 | ||||

| Franz Verzjyl | Gouda | 1 | ||||

| Thomas White | Edinburgh | 1823–1876 | 15 | 1 | 7 | |

| William White | Glasgow | 1806–1891 | 6 | 1 | 4 | |

| Unidentified maker | Netherlands | 2 | 3 | |||

| Total Fragments | 317 | 24 | 129 | 98 |

*distributed by

Table 5.3: Clay pipe makers and distributors represented at the Hyde Park Barracks (dates from Davey 1987; Wilson 1999; Crook et al. 2005:65).51

| Level 2 | Hicks quarters north | Hicks quarters south | Depot ward north | Depot ward south | Stair landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay pipe fragments | 9 | 21 | 67 | 168 | 8 |

| Clay pipe MNV | 3 | 8 | 7 | 38 | 1 |

Table 5.4: Level 2 clay tobacco pipe minimum object count, based on mouthpiece and bowl/shank representation (after Bradley 2000:126).22

| Level 3 | Sick ward north | Sick ward south | Asylum ward north | Asylum ward south | Stair landing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay pipe fragments | 25 | 48 | 180 | 182 | 541 |

| Clay pipe MNV | 6 | 25 | 31 | 50 | 62 |

Table 5.5: Level 3 clay tobacco pipe minimum object count, based on mouthpiece and bowl/shank representation (after Bradley 2000:126).

The clay pipe assemblage from the Hyde Park Barracks is very similar to contemporary collections recorded elsewhere in Australia, including those from The Rocks in Sydney and from the Commonwealth Block in Melbourne, with a high degree of overlap in terms of makers and motifs with the Barracks material (Courtney 1998:98; Williamson 2004, 2006; Wilson 1999). By the 1860s and 1870s, the Australian market for pipes was increasingly dominated by a few large Scottish manufacturers, with smaller quantities deriving from English and European makers (Gojak and Stuart 1999:43). Consumer choice for pipe motifs decreased during the 19th century, as local pipe distribution was controlled by a small number of importers. In spite of the hundreds of motifs produced by pipe manufacturers (e.g. Gallagher 1987), only a limited range of these wares are found in Australian archaeological assemblages of the period. Motifs represented in the Hyde Park Barracks collection thus generally reflect what was available in local stores rather than the aspirations and values of the inmates and immigrants.

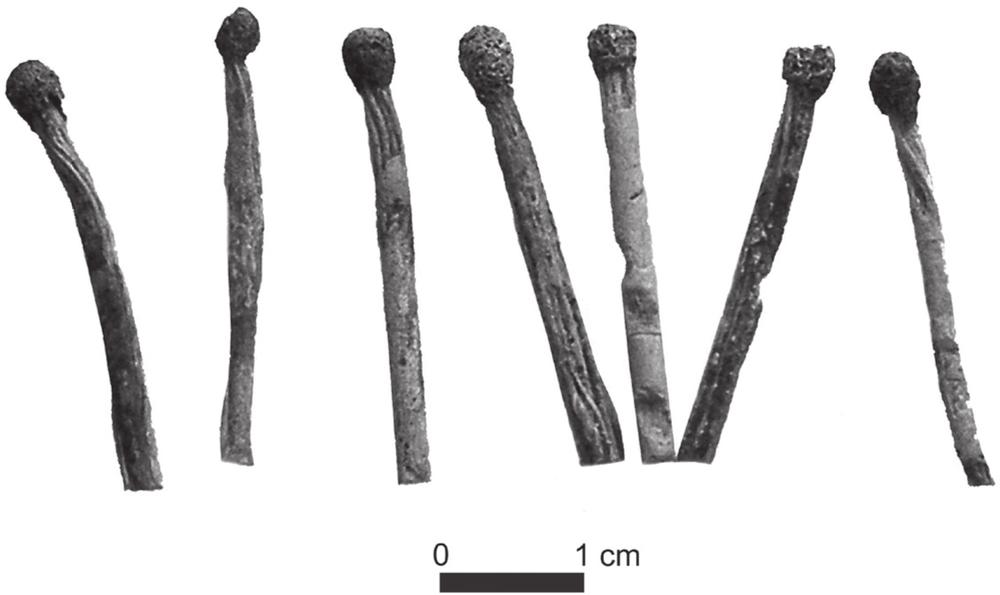

Figure 5.2: Hardened string matches from Level 3 (UF4404; P. Crook 2003).

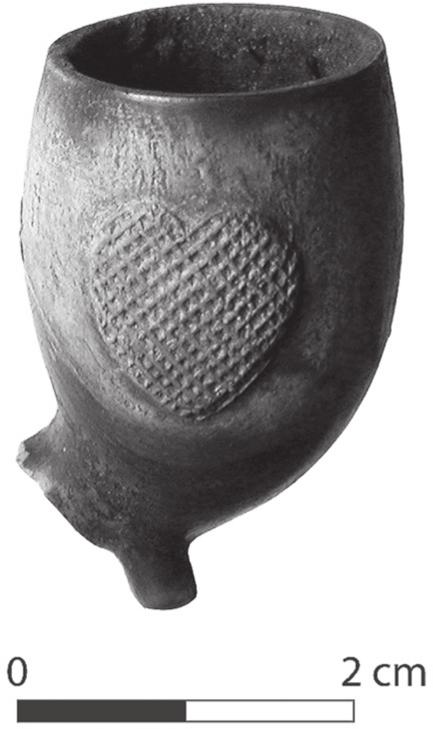

Figure 5.3: Heavily used pipe bowl made by P. McLean of Dundee. The cross-hatched heart served as a match strike (UF3132; P. Davies 2008).

The collection includes very few examples of Irish-themed pipes, such as the navvy-style Dudeen pipes with a short stem, thick bowl wall and rouletted bowl rim (Gojak and Stuart 1999:45). Numerous examples of these were found, however, at Cadmans Cottage and at the Cumberland/Gloucester Streets site in The Rocks (Gojak 1995; Wilson 1999:318–319). Two examples of Irish pipes were recovered from the rear yard at the Barracks, one marked ‘Cork’ on either side of the stem (UF3150), and another marked ‘Dan Lowreys / Music Hall’ (UF3330). Thomas ‘Dan’ Lowrey operated music halls in Dublin during the

521880s and 1890s, including the Star of Erin and the Empire Palace (O’Donnell 1987:156). This pipe may thus date from the judicial phase at the Hyde Park Barracks in the late 19th century. The paucity of Irish-style pipes from the Barracks may reflect the intention of the Matron or the Asylum’s Board not to supply pipes with national affiliations.

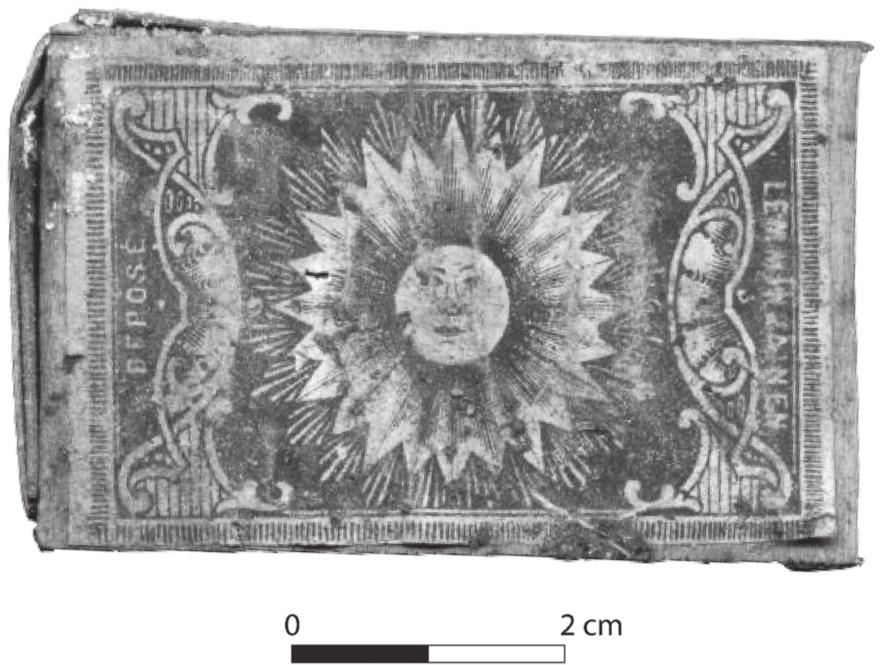

Figure 5.4: Matchbox from tobacconist Thomas Saywell of Park Street in Sydney (UF4286; P. Davies 2008).

Figure 5.5: Matchbox from Swedish manufacturer Björneborgs Tändsticksfabricks (UF17635; P. Crook 2003).

Figure 5.6: Matchbox made in Lidkoping in Sweden between 1880 and 1890. The original design dates from 1851–1860 and was made in Finland by Lemminkainen (pers. comm. Jerry Bell 26 October 2010; UF17636; P. Crook 2004).

| Manufacturer | Place | Date range | Quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bell & Black | London | 1849–1881 | 1 |

| Björneborgs Tändsticksfabricks | Stockholm | 1866– | 5 |

| Bryant & May | London | 1852– | 1 |

| Ellbo | Gothenburg | 1867–1895 | 1 |

| Lemminkainen23 | Finland/Sweden | 1880–1890 | 17 |

| H. Nathan & Co | London | 1876–1877 | 12 |

| T. Saywell | Sydney | 1865–1905 | 2 |

| S. N. H. | London | 1876–1877 | 1 |

| Strängnäs Tändsticksfabricks Aktiebolag | Stockholm | 1874–1881 | 1 |

| Wexiö Tändsticksfabricks | Sweden | 1868–1887 | 1 |

Table 5.6: Matchbox brands recovered from underfloor spaces.

There were also thousands of matches and several hundred matchboxes in the collection. Safety matches were readily available by the 1860s, and typically cost only a penny a box. Most of the matches were wooden, square-cut sticks, although there are also round wooden examples, and 13 matches made from wax-hardened string (Figure 5.2). Complete examples were typically either 1¾ inch (44 mm) or 2 inch (51 mm) long. Matchbox trays and covers were also recovered in large quantities. These were mostly made from folded wood panels with printed paper labels. Box-making machines for cutting, folding and assembling small packages were readily available by this period, making and filling thousands of boxes each day (Cadbury 2010:108). Both labels and striking panels

53(invented by 1855) were often preserved intact, while one example of a pipe bowl (UF3132) featured a match strike in the shape of a heart (Figure 5.3; Shaw-Smith 2003:206). The high representation of Swedish match makers reflects the dominance of Scandinavian manufacture and exports in the fire-lighting market in the 19th century, which was largely replaced by tariff-protected Australian production after Federation (Bell 2008; Figures 5.4, 5.5, 5.6; Table 5.6).

| Mouthpieces | Brown | Brown/yellow | Red | Yellow | Unglazed | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 2 | 7 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 60 | 87 |

| Level 3 | 14 | 34 | 7 | 4 | 89 | 148 |

| Total | 21 | 47 | 11 | 7 | 149 | 235 |

Table 5.7: Glazed clay pipe mouthpiece colours from Levels 2 and 3.

| No staining | Light staining | Heavy staining | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 4 (9%) | 38 (88%) | 1 (2%) | 43 |

| Level 3 | 4 (5%) | 27 (31%) | 56 (64%) | 87 |

Table 5.8: Staining and discoloration on clay pipe bowls from Levels 1 and 3.

The largest concentration of clay pipes on Level 2 was in the south-east dormitory, where 168 clay pipe fragments (MNV 38) were recovered. There were also 958 wooden matches, with most found within a few metres of the fireplace at the western end of the room. The light and warmth of the hearth was clearly a place for the women to congregate. Some of this material, of course, may have derived from the Asylum women, who often occupied Level 2 when numbers of immigrant women were low. Pipe fragments, recovered in small numbers from the Hicks’ family quarters, may relate to the private smoking of John Applewhaite, William Hicks (or any of the Applewhaite-Hicks women for that matter), or to the use of this area for Asylum wards after 1882.24

The main concentration of smoking, however, was clearly on the landing at the top of the stairs on Level 3. Among the 541 fragments found in the underfloor spaces from this area, were at least 43 complete or near-complete bowls. Women congregated at the top of the stairs and lost, discarded or stashed their pipes for later use. Over time, the pipes placed below the floorboards may have been forgotten (unsurprising given that many inmates probably suffered from memory loss and some were known to have senile dementia), or became obscured beneath later rubbish. Some elderly women died. The move to the new asylum at Newington in 1886 was abrupt, and small personal items, especially clay pipes hidden under the floor, may have been accidentally left behind. The popularity of smoking on the Level 3 landing is also evident from the 1,041 matches found in its underfloor spaces, along with 272 matchbox trays and covers.

The rear yard at the eastern end of the Barracks was enclosed in the 1860s to provide separate space for the Asylum women, with a kitchen, bathrooms and laundries. Of the manufacturers identified from 98 pipe fragments excavated in this area, only one was securely dateable to the convict period. The remainder dated broadly from the second half of the 19th century. It seems from the evidence of these artefacts that the Asylum women used the yard as a place to escape the confines of the dormitories and to spend time in the fresh air.

Many of the pipe mouthpieces showed evidence of glazing, applied during the manufacturing process, which kept the smoker’s lips from sticking to the pipe (Table 5.7). This involved dipping the pipe end into a glaze before firing, to produce a smooth finish over the porous clay surface (Bradley 2000:109). Brownish-yellow glazes were the most commonly recorded pipe mouthpiece colour at the Barracks, while examples using red sealing wax, common to the later 19th century, were also identified. No examples of green glazes, however, were recorded in the assemblage.

The intensity of pipe use can also be measured by comparing degrees of tobacco staining recorded on complete bowls from Level 3 and Level 1 (Table 5.8). Dark discoloration is caused by the tobacco oils and tars being absorbed by the clay during smoking. Bradley (2000:127) notes that on very heavily smoked pipes, the outer rim of the bowl can become black with use, and Stocks (2008:41) has recently noted the presence of badly stained (torrefied) pipes at Parramatta from the early 19th century. Burial in certain soil conditions, however, can also remove smoking stains (Nebergall 1996), while burning pipes in a fire can whiten them as well. On both Level 1 and Level 3, a small number of pipes were discarded with no evidence of staining, and thus little, or no apparent, use. The majority of bowls

54from Level 1 (88%), occupied initially by convicts, and later by visitors to the Immigration Depot, showed signs of light staining and thus moderate use. A large proportion of pipe bowls (64%) from Level 3, however, showed signs of blackening and discoloration on both the interior and exterior of the bowl (Figure 5.1). This suggests that the Asylum inmates used their pipes frequently and carefully, having limited access to replacement pipes in the event of loss or breakage. Alternatively, short, heavily blackened pipes have been considered a symbol of identification with the working classes in colonial Sydney in the mid-19th-century, and the inmates may have followed this preference (Gojak and Stuart 1999:40). A plain black pipe bowl (UF3247) from Level 3 appears to have been manufactured from ball clay with the addition of red clay which turned black after firing (K. Courtney pers. comm. 18 March 2011).

Figure 5.7: Heavily stained stem fragment ground down to form new mouthpiece, with tooth marks (UF14388; P. Crook 2003).

Some of the clay pipes provide evidence of modification and reuse. At least 20 stem fragments from Level 3, and 4 from Level 2, have been shortened and re-ground. Several of these examples also have heavy tooth marks on the shortened stem (Figures 5.7 and 5.8). A common pattern was for the original pipe stem to have been broken, either accidentally or deliberately, leaving a very short stem attached to the bowl. The tip was then ground smooth to form a new mouthpiece, with either a rounded or straight finish. These short stems are generally less than 40 mm in length, which meant holding and smoking the pipe fairly close to the face, or possibly gripping the shortened stem with the teeth to free the hands while working. The short pipe stem also increased the ‘hit’ of nicotine.

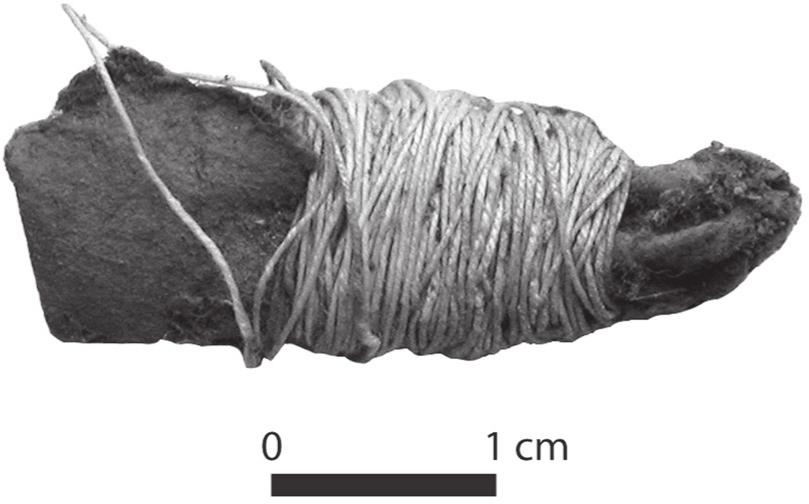

In addition there are 4 examples of repaired clay pipes with bandaged stems consisting of coarse thread wrapped around a layer of paper, cardboard or resin (UF175, UF176, UF177 and UF178; Figures 5.9, 5.10, 5.11, 5.12). Two of the pipes (UF176 and UF178) that came from under the floor boards of the landing on Level 3, may derive from convict phase of occupation, rather than from the later Asylum phase. In addition, 2 pipe stem fragments from the rear yard (UG3631 and UG3632) were reground leaving facets around one end of the stem (Figure 5.13). Wilson (1999:325) identified similar examples from the Cumberland/Gloucester Streets site, in The Rocks, and suggests that they may have been used as a durable kind of chalk, used for marking masonry or brickwork. Unusual examples of pipes include one with a curved stem and copper-alloy ferrule (UF3171; Figure 5.14), similar to an example found at the Victoria Hotel in Auckland (Brassey 1991:29) and the bone screw mouthpiece of a composite pipe (UF3360). A small piece of uncut tobacco (UF3960) from under the Level 3 landing suggests that tobacco may occasionally have been chewed as well.

Figure 5.8: Shortened and reworked stem with tooth marks around new mouthpiece (UF3216; P. Crook 2003).

The popularity of tobacco smoking in colonial Australia, especially among men, is well documented (Cunningham 1966[1827]:132; Gojak and Stuart 1999; Walker 1984). Among women, however, smoking seems to have been a habit primarily of convict and Aboriginal women, and this may have largely ceased by the second half of the 19th century, especially in the cities (Tyrrell 1999:6). Casella has used pipe fragments from the solitary cells at the Ross Female Factory in Tasmania, to identify the use of illicit tobacco among convict women within the Crime Class section of the institution in the early 1850s (Casella 2001a:33). It is probably that, for inmates at the Hyde Park Asylum, tobacco was a simple indulgence and comfort, a way of dulling the daily tedium.

The crowded conditions in the Asylum meant that personal space and privacy were very limited. It is uncertain whether the women kept boxes, bags or chests to hold their few personal possessions. Small items such as clay pipes and tobacco may have been kept in bedding, in an apron pocket, or even hidden under the floorboards as a way of tucking them out of sight and maintaining ownership of them. However, the smaller numbers of pipes recovered from the Depot on Level 2, may suggest that immigrant women, generally from a higher social class, brought with them an awareness of emerging notions of respectability and gentility, which increasingly frowned on female smoking. They may also not have been in the Depot long enough to break and lose tobacco pipes.

Matron Hicks and the Government Asylums Board not only tolerated, but also facilitated, smoking among the inmates by providing tobacco as part of their rations. Freedom to smoke at other institutions, however, varied considerably. Smoking was forbidden at the Sydney Benevolent Asylum, the 55predecessor of the Hyde Park Barracks institution (Cummins 1971:14). At the Melbourne Benevolent Asylum in the 1870s, a journalist noted that while smoking was forbidden inside, there was great consumption of tobacco in the garden outside (James 1969:157; Kehoe 1998:76). Permission to smoke at the Hyde Park Barracks helped with the smooth running of the Asylum. There is little to suggest that tobacco usage was linked to the personal morality of the inmates. Instead, it was made available as a simple indulgence, to comfort the lives of women beset by old age and infirmity. Tobacco provided relief from boredom, and a distraction for hands and minds. Sometimes it also served as a way of trading favours. Congregating in the stairwell or yard, or around the fireplace, or huddling in bed over a pipe, were probably opportunities for gossip and friendship for women who had few other comforts in their lives.

Figure 5.9: Fluted bowl with bandaged stem of dark woven fabric (UF175; P. Crook 2003).

Figure 5.10: Short pipe stem with bandage of coarse thread over hardened gum or resin (UF176; P. Crook 2003).

Figure 5.11: Pipe stem with bandage of coarse thread over cardboard (UF177; P. Crook 2003).

Figure 5.12: Stained pipe with bandaged stem (UF178; P. Crook 2003).

Figure 5.13: Clay pipe stem modified into possible chalk stick (UF3631; P. Crook 2003).

Figure 5.14: Curved pipe stem made by B. Jacobs of London, with mouthpiece edged with metal band (UF3171; P. Crook 2003).

SEWING, CRAFT AND FANCY WORK

Sewing tools and equipment, such as buttons, thimbles, needles and pins, are another substantial component of the archaeological assemblage that provides insights into the daily lives and activities of the Barracks’ women. These items are common to many historical archaeological assemblages, and are often interpreted as significant evidence of women’s work in the domestic sphere (Beaudry 2006; Lydon 1993; Parker 1984). The scale of the Barracks sewing-related assemblage, and the survival and analysis of so many textile pieces, provides an excellent opportunity to expand this area of research.

A total of 4,899 items in the underfloor collection can be directly linked to sewing activities, comprising 6.1% of the collection as a whole (Table 5.9). This includes over 4,700 pins, as well as dozens of needles, cotton reels and other needlework tools. In addition, 10,002 fabric scraps have been recorded, mainly comprising cotton, wool and linen offcuts, along with a number of more or less complete clothing items. These are discussed further in ‘Textiles’ and ‘Clothing’ (below). While most of the sewing was done by hand, the Asylum acquired a second-hand treadle sewing machine in 1878 and another in 1880 (Hughes 2004:84).

Most pins were straight, copper-alloy forms with a simple conical head, ranging in length from 21 to 40 mm. Almost 500 pins were lost beneath the floor of the rooms occupied by the Matron and her family on Level 2, suggesting that Lucy Hicks’ daughters 56spent considerable time on needlework, while Hicks herself may have used the rooms for ‘cutting out’ when she lost access to the lockable room below the stairs. Although pins in historical contexts are normally associated with sewing, and thus women’s work, Mary Beaudry notes that they have also been used to fix hairstyles and secure hats, to fasten nappies, and as ‘poor man’s buttons’. She also points out that pins were rarely used by professional tailors and dressmakers, but they were common in domestic contexts (Beaudry 2006:10–15). During the legal phase of occupation at the Barracks, pins may have been used to fasten papers together. The frequent use (and apparently careless loss) of large quantities of pins at Hyde Park Barracks coincided with the mass-production of pins from the 1830s onwards, especially in England, which reduced the cost of a pound of pins (containing about 10,000 pins) to only one or two shillings (Beaudry 2006:21; Petroski 1993:54–57).

| Item | Level 1 (UG) | Level 2 (UF) | Level 3 (UF) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pins | 2,820 | 1,937 | 2,779 | 7,536 |

| Needles | 2 | 26 | 14 | 42 |

| Pin cushion | – | – | 2 | 2 |

| Packets | – | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Knitting needles | – | 3 | – | 3 |

| Cotton reels and labels | 4 | 20 | 72 | 96 |

| Thimbles | 9 | 2 | 10 | 21 |

| Scissors | 4 | 1 | 4 | 9 |

| Needlework tools (Bobbins, crochet hooks, etc) | 15 | 12 | 10 | 37 |

| Total | 2,854 | 2,005 | 2,894 | 7,753 |

Table 5.9: Sewing equipment from all three levels of the main Barracks building (fragment count).

Thimbles from the Asylum were mostly made of plain copper-alloy with a rolled rim — one example was marked ‘FROM A FRIEND’ (UF8919; Figure 5.15). Two finer thimbles were recovered from the Depot, one decorated with a floral motif (UF11168) and another which was silver plated (UF76).

Figure 5.15: Small copper alloy thimble inscribed ‘FROM A FRIEND’ (UF8919; P. Crook 2003).

Needles were another common item found, including a paper packet containing 22 needles manufactured by H. Milward & Sons (Figure 5.16). There was also a single needle pinned to a small piece of cloth, which survived under the floor for at least a century after it had been put down following the day’s work. Two hand-sewn pin-cushions were also found under the floor in the Asylum on Level 3 (Figure 5.17).

Figure 5.16: Needle packet from H. Milward & Sons (UF75; P. Davies 2010).

Dozens of wooden cotton reels with paper labels were also recovered from the Depot and Asylum deposits. Several are preserved with skeins of thread, usually coloured black, red or brown. Surviving paper labels indicate that the most common thread manufacturer represented in the Barracks material is J. Brook and Sons of Meltham Mills in West 57Yorkshire (n=14). Other makers include I. and W. Taylor of Leicester, Griffith and Son of London and Clark and Co. of Paisley/Glasgow, along with Geary, Carlile, Alexander, and Clapperton. The number of Brook reels reflects the prominence of the firm among Yorkshire thread makers in the 19th century (Giles and Goodall 1992:176). Most reels contained either 100 or 200 yards of thread, with yarns of various grades or weights. Cotton thread was generally thicker than lace thread, twisted from three or more yarns into one (Ure 1970[1836]:226–227; Figures 5.18 and 5.19).

Figure 5.17: Handmade pin cushion (UF10763; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 5.18: Three wooden cotton reels from the northern dormitory on Level 3 (UF8285; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 5.19: Wooden cotton reel with remnant brown thread (UF193; P. Crook 2003).

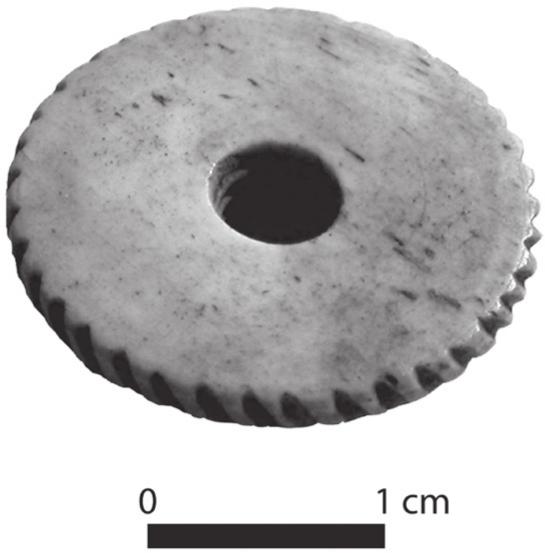

The bone lid from a cotton barrel (UF8842) was also recovered from the Asylum level (Figure 5.20). Prior to the mass-production of wooden cotton reels, from the 1840s onwards, cotton thread was wound on a reel attached to a spindle, and placed in a hollow container. A flat screw-on lid had a central hole through which the top of the spindle protruded. The cotton thread was drawn out through a small hole in the side of the barrel, and was wound back by turning the spindle (Groves 1973:33; Taunton 1997:85). When the barrel was empty the lid was unscrewed and the spindle was sent back to the makers for refilling. Cotton barrels were extremely practical devices, as the enclosed thread was kept clear and clean and did not get tangled up with other objects in the sewing box. The presence of such an item in the Barracks material, among all the conventional wooden reels, suggests that this object may have been a special tool, possibly part of one of the immigrant women’s sewing boxes.

Figure 5.20: Lid from bone cotton barrel (UF8842; P. Davies 2009).

However, other familiar sewing items were much less common in the assemblage. For example, the remains of only 4 pairs of scissors were found in the Asylum level, which may relate to their greater cost, since scissors’ mass-production did not begin until late in the 19th century (Beaudry 2006:122). Only 3 knitting needles were found, and all from Matron Hicks’ quarters on Level 2. This is surprising given that hand knitting is an ancient craft practice which would be consistent with the kinds of ‘women’s work’ normally done in the Asylum. The inmates did a great deal of sewing, but the archaeological evidence suggests they did little, or no, hand knitting.

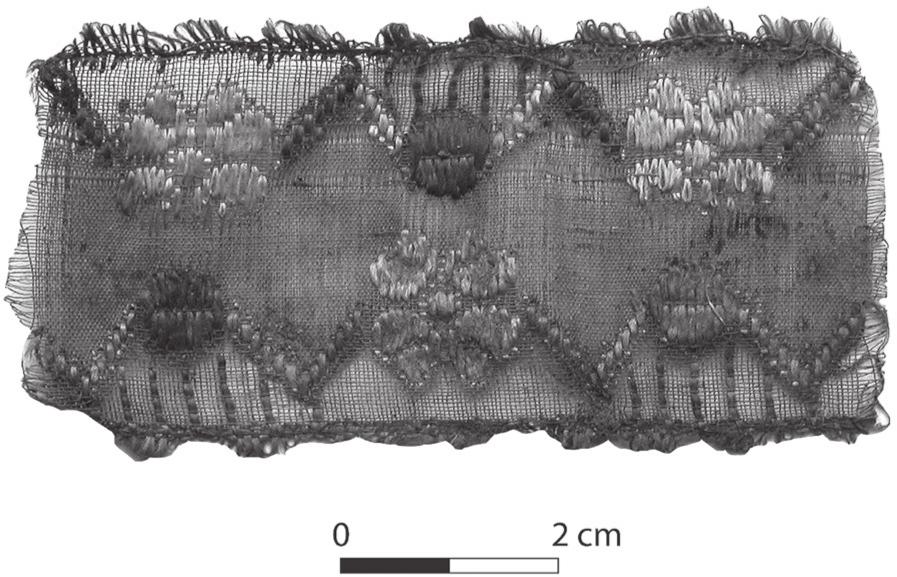

Fancy Work

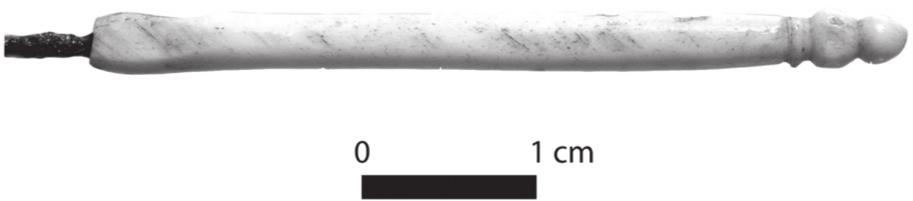

Along with the pins, needles and cotton reels associated with practical, everyday sewing, there were also items in the collection that demonstrate more specialised needlework. These include 19 bone bobbins, 2 bodkins, 2 crochet hooks and 7 unidentified bone tools probably associated with needlework (Figure 5.21; Table 5.10). 58

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodkins | 2 | – | – | 2 |

| Lace Bobbins | 3 | 8 | 8 | 19 |

| Crochet hooks | – | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Tatting shuttles | – | 2 | – | 2 |

| Unidentified bone tools | 5 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

Table 5.10: Needlework tools.

Figure 5.21: Bone handle of needlework tool (UF66; P. Crook 2003).

Bobbins were associated with lace-making, an ancient craft that had become a popular drawing room pastime by the late 18th century. Most lace produced in domestic settings was known as bobbin or pillow-lace. This kind of work involved the use of a pattern drawn on paper affixed to a pillow, along with pins, long threads and bobbins made of wood or bone. Simple lace patterns required up to 50 threads, while complex designs needed hundreds of threads, each attached to a pin and bobbin (Groves 1973:115). English bobbins often had a loop of wire strung with glass or stone beads to provide weight and maintain the necessary tension, a decoration known as a spangle (Deagan 2002:210–211). The pillow allowed the work to be rested on the lap.

During the 19th century the manufacture, display and wearing of fine or fancy needlework pieces by women in Australian colonial society (and elsewhere) helped to distinguish their social class, and degree of gentility within it. The fact that these women had not only the inclination, but also the time, to do such delicate and fine needlework, and consequently employ servants to do the everyday and hard manual work around the house, defined them as middle class. Such pursuits were part of a wider suite of middle-class and aspiring middle-class behaviours and ideology, that were often expressed through material possessions, such as table settings (linen, glass, silver, china) and domestic furnishings and clothing details etc. Lace-making was also, however, a cottage industry in Britain that kept large numbers of women and children working in arduous conditions (Beaudry 2006:151–152; Spenceley 1976). Historians and archaeologists have identified numerous examples of middle-class women engaged in fine needlework to decorate their homes and clothes, and to keep their hands busy (e.g. Beaudry 2006:45, 169–170; Corbin 2000:29–41; Fletcher 1989:3–9; Hayes 2008:318–320; Quirk 2007:184–186; Russell 1994:97–98; Young 2003:73), while convict women were often equipped with patchwork and quilting materials to keep them busy on the long sea voyage (Gero 2008:14–17). Immigrant women were also equipped with sewing materials on the voyage out to Australia (Gothard 2001:119), which they were encouraged to work on further in the Depot. The Hyde Park Barracks Daily Report of Wednesday 3 February 1864 noted:

The work box belonging to the Serocco was opened today the work which was exceedingly good was distributed.

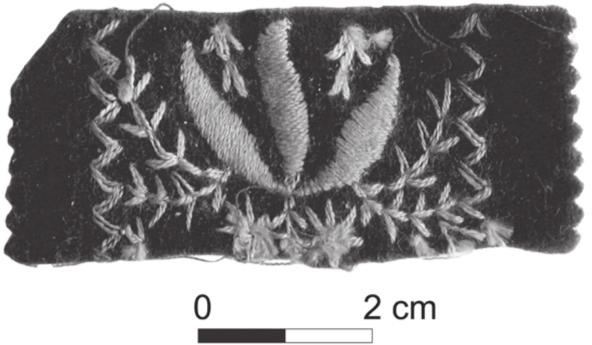

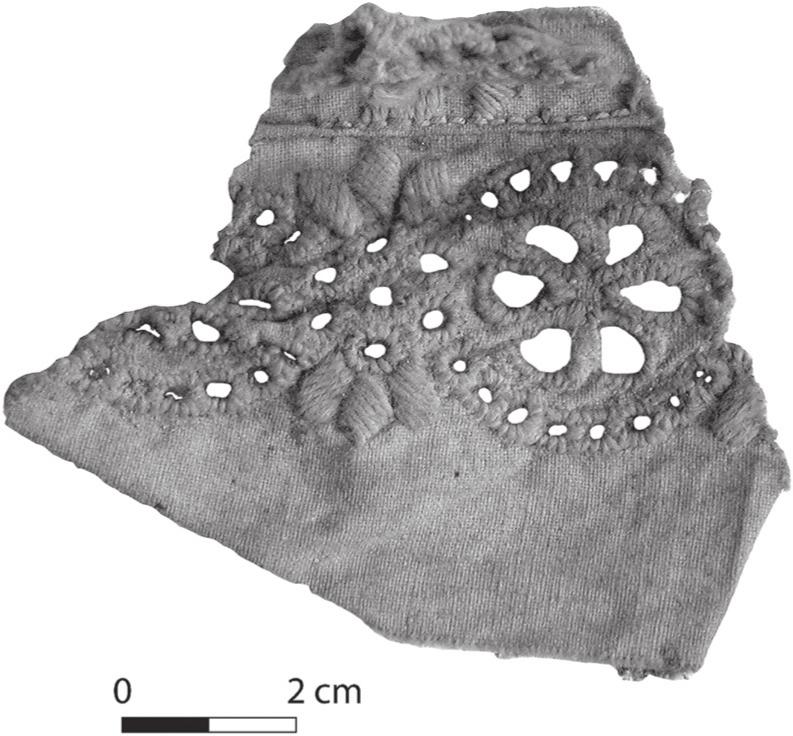

Figure 5.22: Brown velvet embroidered with flower and leaf design (UF978; P. Davies 2009).

Figure 5.23: Plain cotton fragment decorated in broderie anglaise from the Hicks apartments on Level 2. This technique was widely used for baby clothes, dolls’ clothes and underwear in the 19th century (UF18059; P. Davies 2009).

Asylum women appear to have undertaken little in the way of fancy sewing, lacemaking or embroidery, and they were not allowed to undertake paid or contract sewing outside of the institution because the demands of routine sewing for Asylum needs were considered too great (Q2368, Public Charities 59 Commission 1873:76). Examples of fine needlework (Figures 5.22 and 5.23) were confined to Level 2, and are one of the few archaeological patterns where class-based differences are apparent between the Asylum-occupied Level 3 and the predominantly Depot-occupied Level 2.

Hat-Making

Another task performed at times by the women was hat-making. There is no historical record of this work and the only evidence available derives from the archaeological material. At least 114 strands of plaited straw have been identified in the underfloor collection, including 24 pieces from Level 2 and 90 from Level 3 (Figure 5.24). A palm leaf shredding tool (UF11648) was also found beneath the floor of the Asylum. It features eight small metal teeth inserted into a wooden handle, and was used to slice fibre into strips which were woven into plaits for hat or basket-making.

Figure 5.24: Band of plaited palm fibre (UF11636; P. Davies 2010).

Hat-making from the leaves of the cabbage-tree palm Livistonia australis probably began among convicts during the early settlement of Sydney (Ritchie 1971 [1]:16). By the mid-19th century hats had become very popular among both men and women, especially in urban areas, and fine examples could cost up to 10 shillings each (Maynard 1994:170). Straw strips were plaited into narrow braids, and doubled over at each side, creating a serrated edge along each side of the braids. These were sewn into hats with a flat brim up to 15 cm wide (Ollif and Crosthwaite 1977:35). The work was fairly simple and required few tools and inexpensive materials, and it became a cottage industry as well as a common form of institutional labour in the 19th century (Rathbone 1994:33). There is no evidence that the hats were made for sale outside the Asylum and it appears from the location of the remains on Levels 2 and 3 that the work provided hats (and repairs to hats) for women in both the Asylum and Immigration Depot. Photographic evidence from the Newington Asylum around 1890 shows several women in the yard wearing straw hats (Figure 5.43).

Leather-Working and Shoe Repair

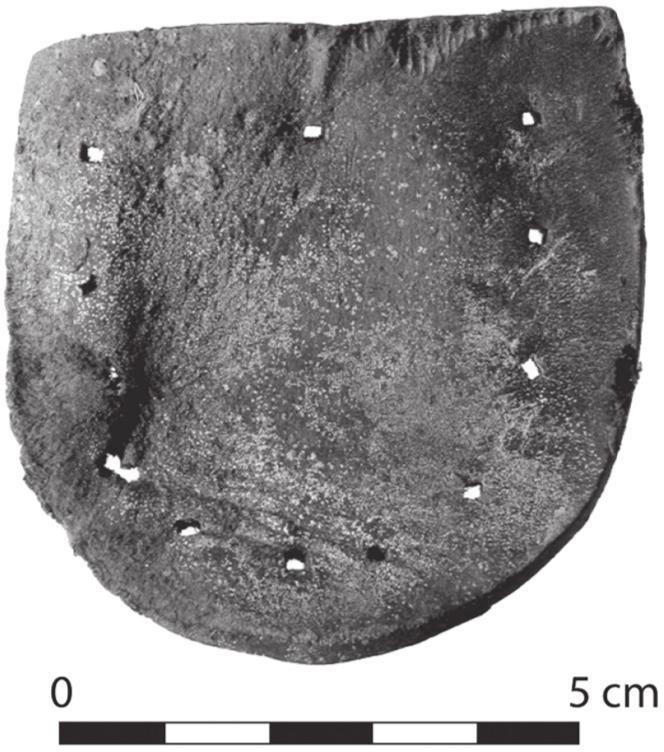

The underfloor collection also offers abundant evidence for leather-working and shoe repair in the Asylum. While the women sewed their own clothing and bedding, boots and shoes were provided by outside contractors (Q2354–2355, Public Charities Commission 1874:76). Mary Applewhaite kept a stock book of such items given to each inmate ‘lest they should require them a little too often’ (Q2281, Public Charities Commission 1874:73). Evidence in the form of hundreds of shoe components and leather offcuts, suggests that in some cases the women themselves repaired shoes and boots (Table 5.11).

| Level 2 | Level 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shoe or slipper | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Shoe lace | 17 | 2 | 19 |

| Heel | 2 | 12 | 14 |

| Sole | 12 | 13 | 25 |

| Welt | – | 2 | 2 |

| Upper | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Unidentified offcuts | 166 | 443 | 609 |

| Total | 204 | 476 | 680 |

Table 5.11: Shoe pieces and leather offcuts.

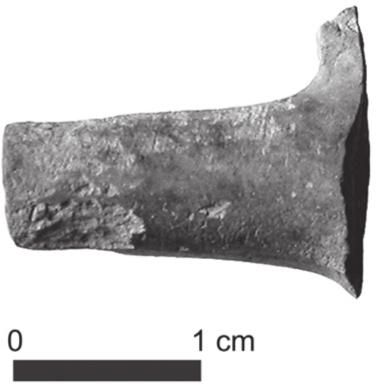

Figure 5.25: Leather shoe heel with square nail holes (UF7490; P. Crook 2003).

The boot trade was well established in Sydney by the 1870s, and it was a largely male-dominated industry, although historian Margaret Maynard notes that women in town and country areas commonly mended boots and shoes as well (Maynard 1994:127; SMH 1 October 1878, p.6; 8 October 1878, p.7). Evidence for shoe repair in the Barracks consists of numerous curved offcut scraps, along with heels and sole pieces (Figure 5.25). A rolled bundle of leather bound with a thong (UF7559) appears to be related to the repair or even manufacture of shoes (Figure 5.26). The leather is 1.5 mm thick and 139 mm (exactly 5½ inches) in width. A strip of leather hand-sewn into a simple loop (UF4374) may have functioned as a finger guard, while a roughly sewn leather knife sheath (UF17347; Figure 5.33) 60may have been associated with leather working and shoe repair as well.

Figure 5.26: Roll of leather for shoe repair (UF7559; P. Davies 2009).

Figure 5.27: Shoe repaired with cotton insert (UF7568; P. Davies 2009).

A well preserved leather shoe (UF7568) from the north-east dormitory on Level 3 reveals something of the style of footwear worn in the Asylum (Figure 5.27). The boot appears to have been rebuilt using a cotton canvas lining to re-attach the leather toe, the suede vamp (upper) and the leather back stay. It is not clear if this repair was done in the Asylum, or by a tradesman cobbler. Wear patterns at the toe indicate that the shoe was worn on the right foot. A hole has also been worn in the canvas lining at the toe, and part of the back stay has broken off. The shoe was fastened with 10 pairs of lace holes extending from the inside ankle to just above the sole. Each lace hole was reinforced with hand stitching, rather than with metal eyes.

Mending and Makeshift Tooling

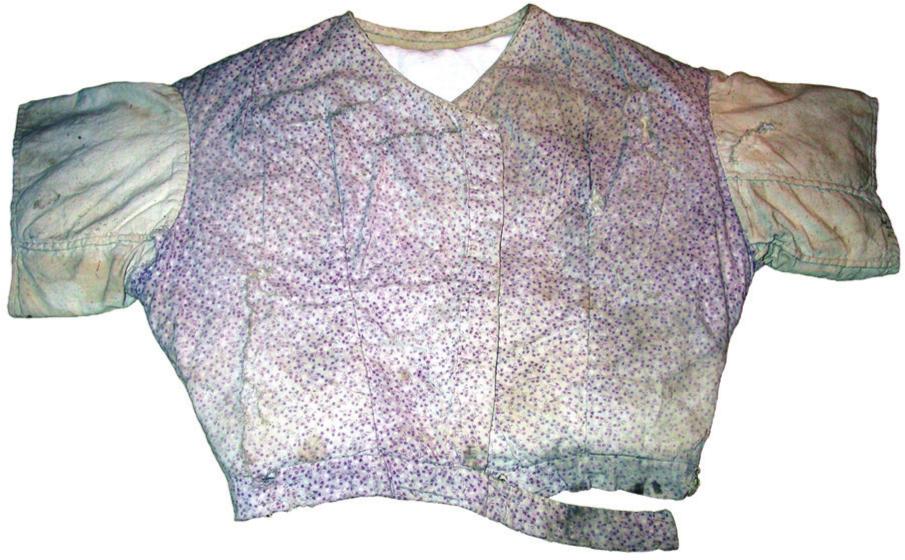

Numerous artefacts were modified and reused by the Asylum women, evidence of their thrifty existence and the necessity of making-do in the institution. Textile offcuts, for example, provide insight into the processes of repairing and recycling clothes. Hundreds of pieces were cut or torn into specific shapes, presumably intended for re-sewing into a garment or other fabric item (see ‘Textiles’, below). These include at least 647 rectangular offcuts identified on Level 3 (Table 5.12). Several clothing items, including the remains of two plain cotton bodices or chemises (UF5534, UF18870) were hand-stitched in segments using these offcut pieces. In addition, a beautifully preserved purple floral bodice (UF52) was cut down to form a bodice with short calico sleeves (see ‘Clothing’).

| Shape | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular | – | 5 | 5 |

| Hexagonal | – | 1 | 1 |

| Irregular | 40 | 1,742 | 1,782 |

| Octagonal | – | 1 | 1 |

| Rectangular | 47 | 647 | 694 |

| Square | 13 | 49 | 62 |

| Triangular | 16 | 32 | 48 |

| Unidentified | 2,491 | 4,702 | 7,193 |

| Total textile offcuts | 2,607 | 7,179 | 9,786 |

Table 5.12: Shape of textile offcuts from Levels 2 and 3.

In addition to these flat offcuts, at least 324 textile pieces were carefully cut or torn along the seams or hems of former garments to maximise the area of unstitched sheet fabric with which to make a new garment. As this process left behind only the spine or structure of the former garment, we have called them ‘structural offcuts’ (Figure 5.28). While they comprise just 3.3% of all fabric scraps, they are compelling evidence of the regular recycling of garments at the end of their life-cycle within the Asylum.

Figure 5.28: Plain cotton structural offcut hem (UF18778; P. Davies 2010).

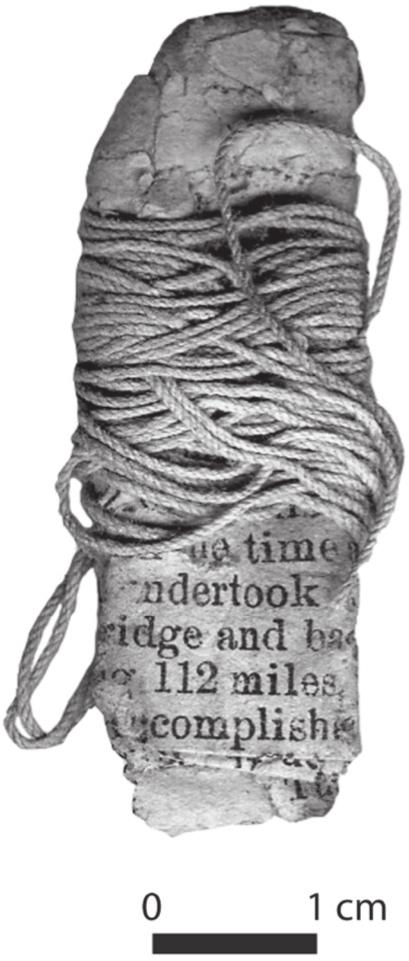

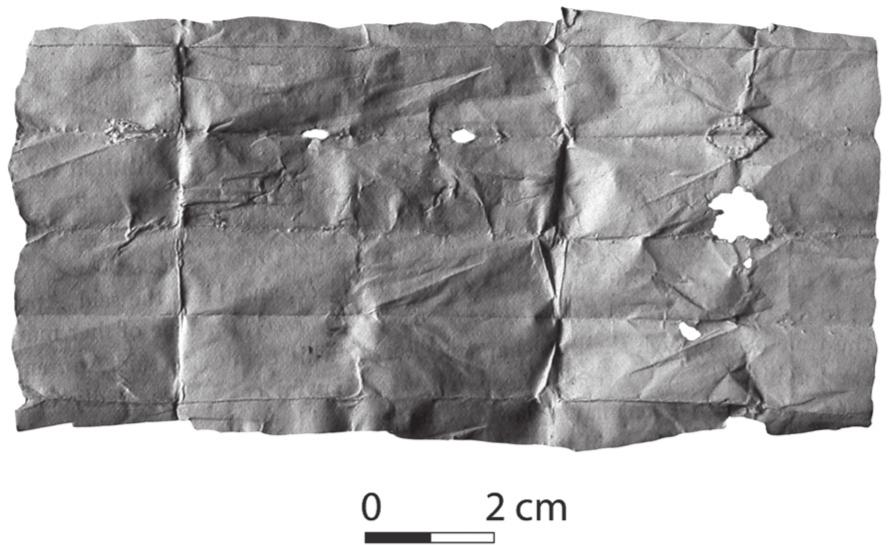

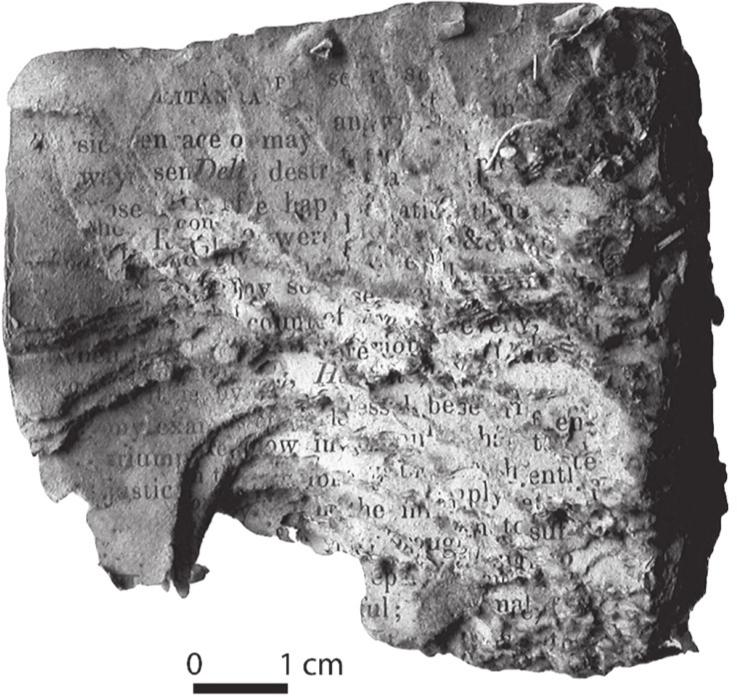

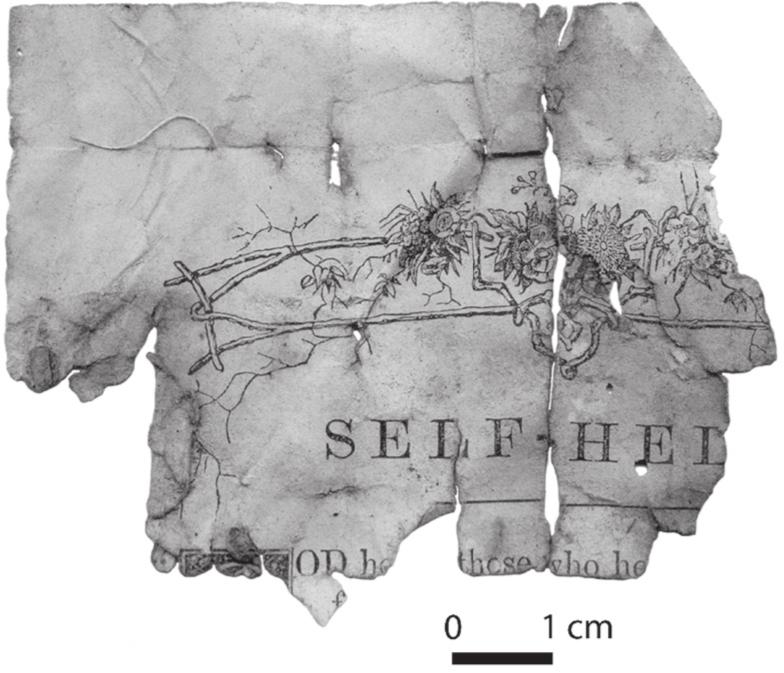

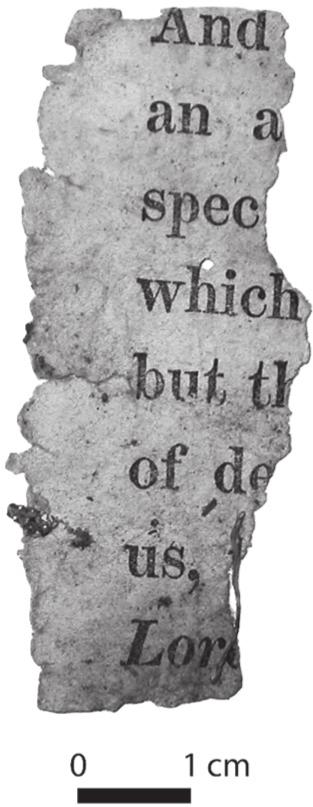

Further examples of ‘making-do’ are found with sewing tools and other domestic items. A tatting shuttle (UF33), for example, was crafted from woodsheet covered with blue paper and joined with rough stitching (Figure 5.29). Temporary cotton reels were made by winding threads around a piece of bone (UF6965), paper (UF2775, UF4712; Figure 5.30), and a twist of newsprint (UF11305; Figure 5.31). A makeshift pin packet (UF4398) consisted of a rectangle of paper carefully torn and cut into 61shape, with rust stains from the pins originally folded inside (Figure 5.32). Four roughly whittled wooden sticks with a point at one end were also found, which may have been used for splitting thick palm fronds into smaller pieces for hat-making. A complete circular pin cushion (UF10763; Figure 5.17) from the southern dormitory on Level 3 was hand made from fabric scraps which included several lines of illegible print.

Figure 5.29: Makeshift tatting shuttle, possibly crafted from a discarded matchbox (UF33; P. Crook 2003).

Figure 5.30: Makeshift thread reel made from piece of folded cardboard (UF4712; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 5.31: Makeshift thread reel made from folded newspaper (UF11305; P. Crook 2003).

Other items include a small pouch that was roughly made from cardboard backing stitched to a leather cover and protective flap (UF17347), possibly to hold a penknife or other tool (Figure 5.33). At least 2 clothes pegs were hand carved (UF37 and UF14414; Figure 5.34), along with 4 wooden stoppers (UF3485, UF4433, UF8998 and UF12576).

Figure 5.32: Paper offcut used as pin packet (UF4398; P. Davies 2009).

Figure 5.33: Hand sewn leather knife sheath from the stair landing on Level 3 (UF17347; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 5.34: Roughly made wooden clothes peg (UF37; P. Crook 2003).

The inmates were not alone in their careful use of materials. Matron Hicks explained to the 1873 Inquiry that ‘There are sheets to be patched — because when a sheet goes into holes I do not throw it away; I turn the sides to the middle, and make it do again’ (Q2368, Public Charities Commission 1874:76). The Matron’s additional comment, ‘the old women are celebrated for patching’, is demonstrated by numerous examples of patched clothes and darned stockings in the collection.

Additional evidence for thrift among the women is found in the repair of broken clay tobacco pipes (see ‘Smoking’) and the reuse of alcohol bottles to contain medicines (see ‘Medicines’).

TEXTILES

Textiles are a significant part of the Barracks assemblage, with 10,002 scraps and offcuts comprising 12.5% of the underfloor collection. The 62majority of the fabrics were cotton pieces, with smaller quantities of linen, silk, wool and composite materials (Table 5.13). Textiles range in size from large offcuts torn from clothing to tiny scraps only a few millimetres wide. There were also dozens of clothing items and components identified in the collection, described further in ‘Clothing’. The ‘Unidentified/Mixed’ category includes various pieces of thick, heavily woven wool, cotton and jute fibres probably used for furniture and floor coverings.

| Textile | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite | 10 | 29 | 39 |

| Cotton | 1,789 | 5,056 | 6,845 |

| Damask | 1 | – | 1 |

| Linen | 35 | 302 | 337 |

| Silk | 61 | 89 | 150 |

| Velvet | 10 | 19 | 29 |

| Wool | 163 | 195 | 348 |

| Unidentified/Mixed | 823 | 1,430 | 2,253 |

| Total | 2,882 | 7,120 | 10,002 |

Table 5.13: Textile types from Levels 2 and 3.

As textiles rarely survive in most archaeological contexts, we generally lack well developed methods of analysis and research for this class of artefact. Textiles do, however, have significant analytical potential, in terms of garments and clothing components versus cut pieces and rags; outer wear and underwear; women’s and men’s clothing; hand stitches and machine sewing; and changes in styles and fashion. In addition, textile manufacturing technologies, weave patterns, and dyes and colours are important expressions of changing industrial technologies and consumer behaviours (LaRoche and McGowan 2000:275; see also Barber 1991). We address a number of these issues below and in the following section on ‘Clothing’.

The sheer quantity of textiles recovered from the Barracks has no known parallels in historical archaeology from around the world. A smaller assemblage, comprising around 1000 wool fragments, was recovered from cesspits at Block 160 in the Five Points site in New York City, and analysed in terms of textile technology and the beginnings of the garment industry in New York in the 19th century (LaRoche and McGowan 2000). Many of the pieces had been torn into strips, and were interpreted as evidence for domestic rug making. Cotton strips are also very common at the Barracks, but there is no evidence they were used in rugs, although they may have been used to stuff pillows and mattresses. Around 4000 textile fragments were recovered from sub-floor deposits in 3 adjoining houses in Kempten in southern Germany, dating between 1470 and 1530, representing a range of textiles and woven products (Atzbach 2013:266). Over 300 fragments of wool and cotton were also found on goldmining sites at Otago in New Zealand, probably representing European garments worn by Chinese miners (Ritchie 1986:551).

The Hyde Park Barracks collection includes more than 23 kg of textile and clothing fragments. Some textile offcuts were probably sold by weight to the ragmen who provided scrap fabric to the local paper industry,25 but many smaller pieces were clearly swept under the floorboards. Some of these rags may have been used as sanitary napkins (e.g. UF11602) or as toilet paper, especially among bedridden old women. Rolls of toilet paper did not come into popular use until late in the 19th century, and until this time most people used cotton waste or old newspapers instead (Eveleigh 2002:136). Further examination and chemical analysis of stained textile fragments may be necessary to determine such uses.

The large amount of cotton in the collection reflects the dominant position this textile had secured in the international textile industry by the 19th century. While wool and linen were the traditional garment textiles of northern Europe, by the late 18th century cotton factories in England were producing huge quantities of cotton fabric, known generically as ‘calicoes’, using raw material imported from India, the United States and the West Indies (Yafa 2006:59). Small-scale textile production had occurred sporadically in Australia during the first half of the 19th century, but most operations lapsed due to lack of raw materials and skilled workers (Liston 2008; Maynard 1994:34–36; Stenning 1993). Historian Deborah Oxley (1996:16) noted that there were few textile workers among female convicts sent to New South Wales. Instead, most textiles for clothing were imported in bulk from Great Britain — a scrap of fine cotton from Level 2 was marked ‘Thos. Hoyle & Sons; Manchester; British Cambric’ (UF4713; Figure 5.35).

Figure 5.35: Scrap of fine cotton with manufacturer’s stamp in black ink (UF4713; P. Davies 2010).

Silk pieces came in a range of colours, with black and brown the most common hues, along with shades of pink, green and purple. Silk clothing

63and accessories were associated with fashion and style in 19th-century Australia (Fletcher 1984:121–122; Maynard 1994:113), with working-class men and women’s love of wearing silk clothing often making it difficult for new arrivals from England to distinguish between convicts, emancipists and free settlers (Elliott 1995). Most of the identifiable silk fragments from the Barracks were from ribbons, although there were also the remains of a silk scarf from below the landing on Level 3 (UF16754) and a brown silk sleeve cuff (UF10820) also from the Asylum.

When the Immigration Depot opened in 1848, the old convict hammocks were replaced with folding iron beds, which were later used by the Asylum women as well. Mattresses and pillows were generally made from ‘ticking’, a thick linen or cotton fabric usually woven in blue stripes or checks. Hundreds of pieces of this material were represented in the collection, and it may also have been used for bath towels and dishcloths, as looped cotton (terry towelling) only became used for bathing towards the end of the 19th century (Young 2003:98). In some cases this bedding material was used for garments as well, with the remains of an apron (UF18607) made from this fabric found on Level 3.

Cotton Prints

Cotton prints at the Barracks included a wide range of colours and patterns (Table 5.14). The most common print colours were blue and mauve or purple, generally used for clothing items. Undergarments in this period were normally white, rather than printed, as coloured underwear was considered slightly debauched (Baines 1966:254; Flanders 2003:270). In the 18th and 19th centuries whiteness was often associated with physical cleanliness and moral propriety, and the uncoloured remains of underclothing at the Barracks may reflect this preference, or else a simple concern with economy (Tarlow 2007:170). Outer clothes, however, along with drapery and furniture fabrics, were typically printed with colours and patterns. Women in both the Asylum and the Depot appear to have worn clothing from a variety of fabrics, designs and colours.

| Print Colour | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqua | – | 10 | 10 |

| Black | 17 | 18 | 35 |

| Blue | 52 | 387 | 424 |

| Brown | 52 | 95 | 147 |

| Composite | 62 | 83 | 145 |

| Green | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Orange | – | 2 | 2 |

| Pink | 6 | 13 | 19 |

| Purple | 112 | 212 | 324 |

| Red | 12 | 40 | 52 |

| White/Cream | 51 | 205 | 256 |

| Yellow | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Unidentified | 1,437 | 3,980 | 5,417 |

| Total | 1,789 | 5,056 | 6,845 |

Table 5.14: Cotton textile print colours.

Cotton printing was used in India for several thousand years prior to the development of the industry in Europe in the 17th century. Prints were originally made with wood blocks, but the development of cylinder printing in the 1780s in England and France transformed the industry (Baines 1966:266). A polished copper cylinder was engraved with a pattern around its circumference and then rolled horizontally through a coloured dye. The excess was scraped off with a steel blade, leaving the colour only in the engraved pattern. The calico was rolled around the drum and drawn tightly over the engraved pattern, printing onto the cloth. By the early 19th century, multiple cylinders were used to print complex, multi-coloured pieces at high volume. By 1851 production had reached 600 million yards of printed textile, and by 1889 there were almost 2 billion yards printed annually, and brightly coloured cottons were cheaply available for mass-market consumption (Turnbull 1951:81, 114).

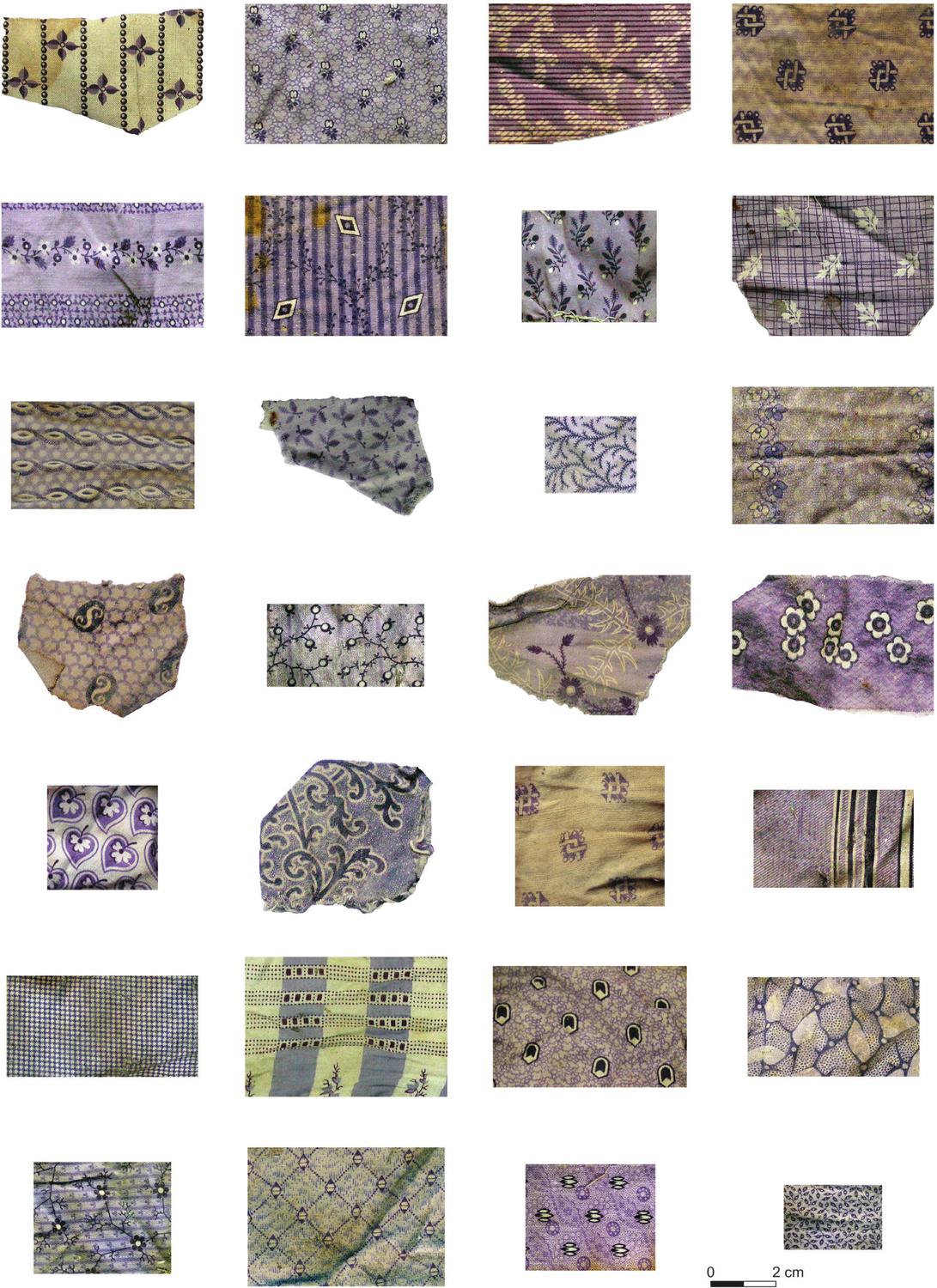

Dyes and mordants were also improved during this period. Until the middle of the 19th century, textile dyes were based on traditional plant and metallic substances. In 1856, however, the first commercially successful synthetic dye was accidentally discovered by 18-year-old William Henry Perkin at the Royal College of Chemistry (Tordoff 1984:20). His creation of a purple dye (known as mauveine) from coal tar prompted a rush of research into the manufacture of synthetic dyes, resulting in new, cheap colours for the textile industry (Garfield 2000:64–70).

Within a year of its discovery purple had become a highly fashionable colour for women’s clothing, stimulated in part by the Empress Eugénie of France who wore it often. Technical refinements in the next few years improved printing on silk and cotton, and purple was all the rage until about 1861, when fashion moved on. Mauve soon shifted from the colour of fashion and display to a colour of mourning, when Queen Victoria graduated from black to mauve several years after the death of Prince Albert in 1861. By the late 1860s, mauve was all but forgotten as a fashionable colour.

Purple print designs at the Barracks were mostly two-tone mauve, stylised floral and foliate patterns, with simple lines and flattened colour (Figure 5.36). At least 76 different patterns in purple have been identified in the underfloor assemblage, along with others in red and blue. Such textiles became very common at the Asylum in the 1870s, just as the general price of printed calicoes in England steadily declined (Turnbull 1951:112). The women wore clothing made from a mix of cheap, colourful prints and plain, undecorated cottons. 64

Figure 5.36: Purple cotton prints from Levels 2 and 3; Row 1: UF46430, UF9286, UF10818, UF11537; Row 2: UF11561, UF11656, UF18260, UF18268; Row 3: UF18341, UF18389, UF18399, UF18455; Row 4: UF18463, UF18473, UF18486, UF18496; Row 5: UF18497, UF18542, UF18548, UF18577; Row 6: UF18614, UF18711, UF18765, UF18768; Row 7: UF18830, UF18881, UF18899, UF18954 (P. Davies 2011).65

CLOTHING

Fashionable dress and convict clothing in 19th-century Australia has been reasonably well documented over the years (e.g. Elliott 1995; Fletcher 1984; Flower 1968; Maynard 1987, 1994; Sanders 1992; Scandrett 1978; Whitty 2000; Young 1988). The clothing worn by working Australians, however, as well as the uniforms of those in institutions, is much less well known, as items were often worn until they were threadbare, and few survived to have found their way into museum collections. Numerous clothing pieces from the Hyde Park Barracks thus provide an important source of information about how the inmates dressed, the accessories they wore, and how uniforms functioned in a context of institutional refuge. Most of the women wore simple cotton or woollen garments, including petticoats, a chemise (shift or undershirt) and dress (bodice and skirt), along with an apron and bonnet, and a nightgown for bed.

Several items of clothing identified in the Barracks underfloor collection probably relate to convicts. The most notable example is a complete blue striped cotton shirt found on Level 3 (UF51). This neatly sewn garment includes a simple upright collar with two bone buttons, a narrow v-neck, and gathered cuffs on the sleeves. A small broad arrow stamp on the tail marks the garment as government property, although this style of shirt was worn by both convicts and free workers. Another patched and poorly preserved shirt (UF8114) was also found on Level 3, while a set of hand-sewn linen braces (UF53) includes remnants of yellow wool (Parramatta) cloth. This item may have been made from the lining of a convict jacket. Several historians have pointed out that convicts in Australia did not necessarily dress differently from other colonists, which, as we note above, often made it difficult for new arrivals from England to distinguish between convicts and other groups (Elliott 1995; Maynard 1994:14–23). Margaret Maynard (1994:21) has also argued that coarse yellow clothing was synonymous with convicts in the 1820s and 1830s, and that the Hyde Park Barracks (HPB) shirt (UF51) could actually have belonged to a soldier.

Clothing was available from various suppliers in colonial Australia. Local tailors made garments for men, but they struggled to compete against cheaper imports from England. There was little in the way of readymade clothing for women and children, however, until the 1880s. Public auction and the second-hand market thus remained important sources of clothing for many people, while tailors and dressmakers made clothing to order (Maynard 1994:39–40). Most women, however, made their own clothing, as well as clothing for their husbands and children. From the 1850s onwards this became easier with the introduction of self-acting sewing machines, and the production of dress patterns and pattern books for use in the home (Arnold 1977:3; Godley 1996; Knox 1995:77–78).

Figure 5.37: Blue woollen sock (UF10760; P. Davies 2010).

Many of the Asylum women wore thick, machine-knitted stockings made from cotton or wool, either calf or knee length. Knitted fabric is more elastic than woven fabric because it is composed of interlocking loops made from one continuous piece of thread, providing a flexible, smooth fit for items worn close to the body such as socks or stockings (Palmer 1984:3). Numerous examples of stockings have been found in the underfloor collection, including one that bore the HPB laundry stamp (UF11734). Most of the stockings had been darned or repaired at some stage, with most wear at the toes and heels. A pair of pale blue, knee-high socks from Level 3 may have been worn in bed by invalids (UF10760; Figure 5.37), while an intact stocking made from silk and fine cotton featured an embroidered flower above the ankle (UF948). Two much-worn slippers were also found on Level 3, with leather soles and heels, chamois sides and cotton lining (UF127).

Figure 5.38: Remains of cotton cuff and sleeve with blue geometric prints (UF11546; P. Davies 2010).

Pieces of fabric from garments for upper parts of the body, and bodices were also recovered from the Asylum rooms on Level 3, including handsewn sleeves made in segments from various plain cotton offcuts (UF5534, UF11629). Most sleeves were long (shoulder to hand) and several still had wrist buttons attached (Figure 5.38). A remarkably well preserved cotton bodice was found in the large southern dormitory of the Asylum. It was made from purple-printed cotton with short calico sleeves and metal hooks-and-eyes (UF52; Figure 5.39). The item features a shallow V-neck and pleats to gather the garment at the waist, and it has a HPB 66laundry stamp at the rear. The mix of fabrics used in the bodice is evidence of a highly individual manufacture or alteration, perhaps made by one of the Asylum women for herself or a friend. Another complete cotton bodice, for a child or infant, was found under the stair landing on Level 3 (UF930; See ‘Children at the Hyde Park Barracks’).

Figure 5.39: Cotton bodice in purple print and modified with plain calico sleeves (UF52; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 5.40: Cotton apron with hand-made lace trim; button and tie remnant preserved at waist (UF54; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 5.41: Hand sewn bonnet with ruffle around face (UF55; P. Davies 2010).

Other clothing items include the remains of 5 aprons from the Asylum, with examples in a brown and white check pattern (UF11638), red polka dots (UF9284), and blue and white stripes (UF18607; Figure 5.40). Aprons were important emblems of women’s work, providing protection from dirt in manual labour and thus serving as visible signs of industry. They were commonly worn both in the home and in institutions (Cunningham 1974:148; De Marly 1986:118). Examples of headwear worn by the Asylum women were also found in the collection. These include the remains of 9 cotton bonnets, all found on Level 3. One was marked with the HPB laundry stamp and was sewn with a ruffle around the face and a cotton tape tie (Figure 5.41). Photographs of inmates in the dining room and the yard of the Newington Asylum, taken around 1890, show most of the women wearing aprons and head coverings such as bonnets (Figures 5.42 and 5.43).

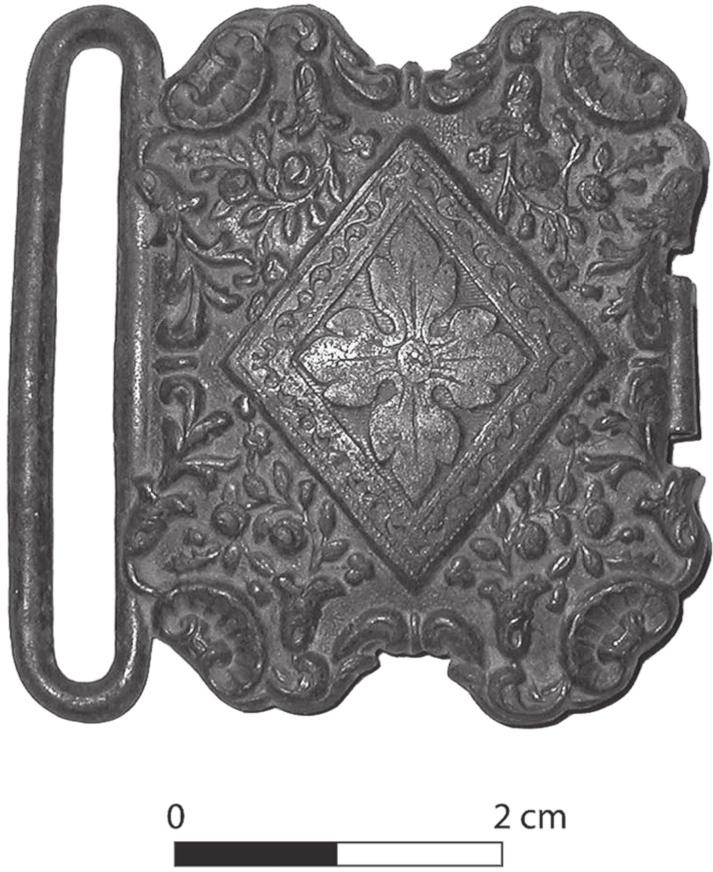

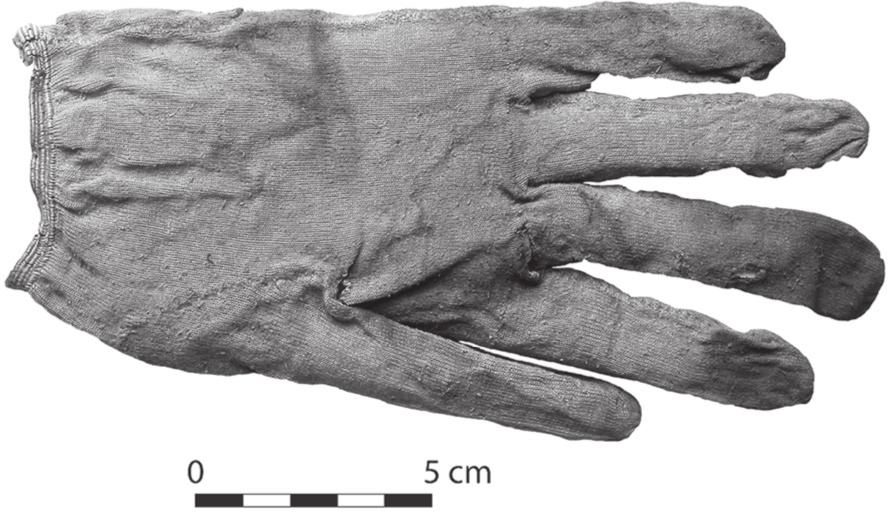

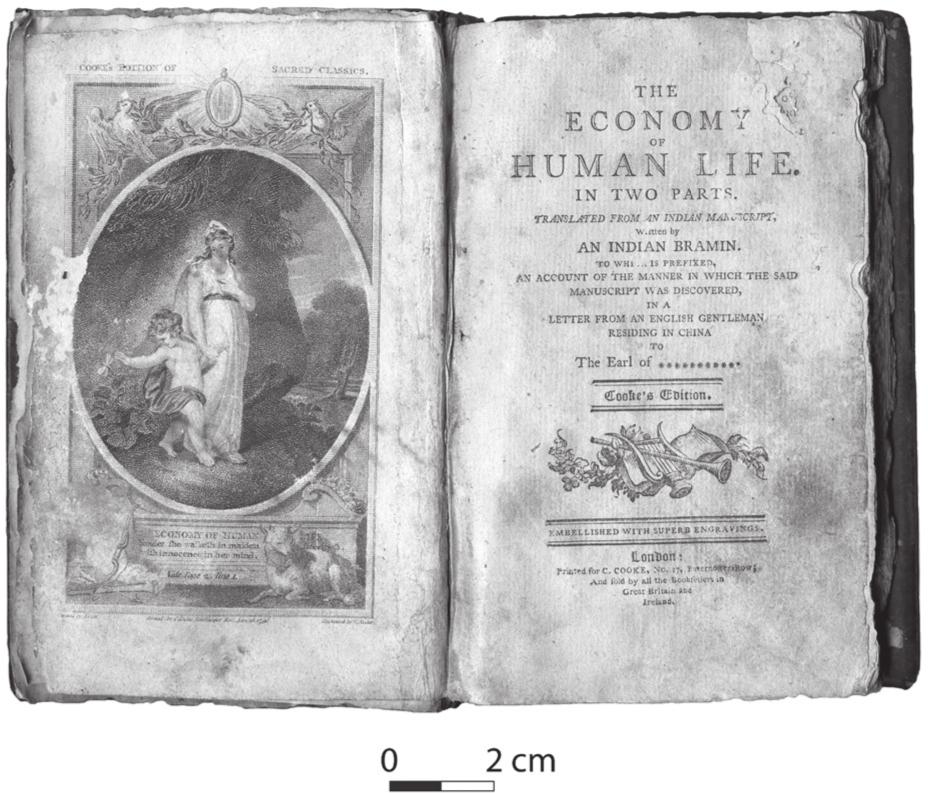

Various clothing accessories were also identified in the collection (Table 5.15). These include the remains of 7 handkerchiefs from Level 3, including several examples in fine woven linen. There were also various leather belts and clothing buckles made from ferrous metal and copper alloy (Figure 5.44). The remains of gloves were also identified, including three complete cotton gloves from the Asylum (Figure 5.45) and 4 finger pieces from leather gloves in the Immigration Depot. Wearing kid leather gloves denoted affluence and class in the 19th century, marking the divide between those who worked and those who did not. Gloves were often worn very tight, restricting the manual activity of the wearer (Levitt 1986:130). The fragments of leather gloves derive mostly from Level 2, occupied at various times, both by the immigrant women, who came to Australia to work in domestic service, and by the Applewhaite-Hicks daughters and their friends. Even among the Asylum women, however, there were a few who kept the cheaper cotton gloves as a sign of personal respectability, even though cotton gloves were considered vulgar in some quarters (Beaujot 2012:44; Flanders 2003:256).

| Clothing items | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apron | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Belt | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| Bodice | – | 9 | 9 |

| Bonnet | – | 9 | 9 |

| Braces | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Buckle | 6 | 13 | 19 |

| Collar | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Cuff | 5 | 18 | 23 |

| Glove | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Handkerchief | – | 7 | 7 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Ribbon | 41 | 40 | 81 |

| Skirt | – | 2 | 2 |

| Sleeve | – | 8 | 8 |

| Sock/Stocking | 9 | 38 | 47 |

| Total | 75 | 172 | 247 |

Table 5.15:67 Garment remains, components and accessories recovered from the underfloor collection.

Figure 5.42: Dining room at Newington Women’s Asylum, around 1890 (Small Picture File, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW).

Figure 5.43:68 Inmates in yard at Newington Women’s Asylum, around 1890 (Small Picture File, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW).

Figure 5.44: Copper alloy belt buckle with central lozenge and four leaf motif (UF67; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 5.45: Plain cotton glove with elastic wrist band (UF10793; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 5.46: Open weave brown ribbon with blue loops on selvage and hand sewn floral motif (UF11521; P. Davies 2010).

There were also dozens of ribbons and ribbon fragments in silk and silk-like fabrics, in a variety of colours (Figure 5.46). These were often used as dress accessories to update and refresh an old outfit (Fletcher 1984:120–121). Ribbons were found in almost the same quantities in the Asylum as in the Depot, and suggest that the inmates may have taken the opportunity to trim their clothing or bonnets with a little colour.

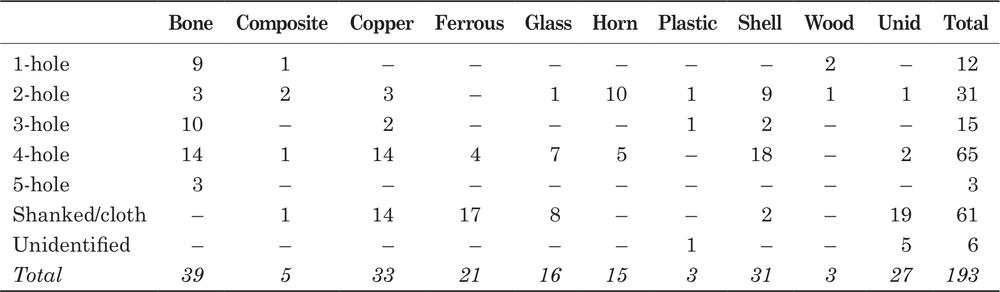

Clothing fasteners were also found in large numbers in the underfloor spaces. These included 193 buttons from Level 2 and 396 from Level 3, along with 750 ferrous and copper alloy hooks-and-eyes (Figure 5.47). Button materials included shell, bone, copper alloy and rolled iron, along with smaller numbers of horn, wood and glass. Button styles included sew-through examples with one, two, three, four and five holes, along with various shanked and cloth-covered (dorset) types. Bone buttons with a single hole were used either with a pinshank or as a blank for thread or fabric-covered buttons (Lindbergh 1999:51). Button manufacturers identified include Harris & Son, McGowan, and Boggett & Co, all of London.

Figure 5.47: Card backing for a packet of hooks-and-eyes (UF17508; P. Crook 2003).

Buttons and hooks were used to fasten various items of clothing, including bodices and sleeve cuffs (Lindbergh 1999:51). They were distributed fairly evenly throughout the underfloor spaces on both levels, suggesting that the sewing of buttons on clothing, and their accidental loss, were widespread in the Asylum and Immigration Depot. The large numbers reinforce the amount of sewing and 69clothing repair that the women were engaged in, with most hooks and buttons small enough to fall between the floorboards. The buttons were not, however, a standard type, as might be expected in an institutional context. Instead, the collection is distinctive for the sheer diversity of forms and materials (Tables 5.16 and 5.17). Buttons entered the Barracks on many different garments and were then reused before their eventual discard or loss.

Table 5.16: Button forms and materials from Level 2.

Table 5.17: Button forms and materials from Level 3.

Women at the Hyde Park Asylum each wore a similar set of garments, issued to them on their arrival. These generally comprised a long-sleeved cotton chemise or undershirt, one or more petticoats of plain or printed calico, a cotton or wincey26 dress (skirt and bodice), and machine-knit cotton or wool stockings. In addition they wore cotton aprons of various colours and patterns, leather shoes or slippers, and a bonnet or woven-straw hat for outside use. This was very similar to the clothing worn by women at the Port Macquarie Asylum in the 1860s. Frederic King, Secretary of the Government Asylums Board, reported that the women were provided with ‘one dress, one shawl, one apron, one flannel petticoat, one chemise, one cap, one pair shoes, and one pair plain woollen stockings’ (Government Asylums Board 1867:108). King also noted that the recent establishment of the Port Macquarie Asylum (in 1866) meant that there was little in the way of old clothing to supplement supplies and keep the women warm in winter. At Hyde Park, in contrast, the women were in the habit of wearing second-hand skirts as warm petticoats. The evidence thus suggests that the inmates wore lighter cotton prints in the warmer months and wool blends in the winter.27 This echoes historian Margaret Maynard’s view that climate and environmental conditions in Australia had an important impact on the way people dressed, and that most people made practical choices in what to wear, rather than slavishly following English cool-weather models (Maynard 1994:151).

The clothing and textile remains also indicate considerable diversity in the cotton print patterns worn by the women. With more than 70 different purple prints identified in the collection, the fabric from which the women made their clothing was not identical and standardised but varied subtly according to the textiles available from local distributors, or from low cost purchase of end-of-line bolts of fabric, or from recut second hand clothing. While inmates generally wore the same array of garments, each woman’s appearance varied slightly,

70in terms of the different fabric patterns used in their clothing, and probably, in shapes and styles.

The unimportance of a strict institutional uniform at the Hyde Park Asylum is also evident in testimony given by Matron Hicks to the Public Charities Commission in 1873. She acknowledged that while the women dressed ‘as nearly as possible’ in a uniform, some preferred ‘to keep their own clothing — for instance, if a woman is in mourning’ (Q2359, Public Charities Commission 1874:76). Others were ‘too proud’ to wear a uniform and continued wearing their own clothes (Q618, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:459). Hicks was flexible in her management of the inmates, recognising that the women were not prisoners but ‘poor old creatures’ for whom clothing was a matter of comfort and convenience rather than discipline and control.

Lucy Hicks was also involved in both the manufacture and the distribution of clothing. As noted, the Asylum received large bolts of cloth, such as 1000 yards of calico, supplied by tenders issued by the Government Asylums Board (Q2368, Public Charities Commission 1874:76). One thousand yards of calico provided fabric for up to several hundred chemises and night dresses (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887, Appendix C:51). Mrs Hicks used a room on Level 1 to cut the fabric into pieces for sewing into dresses and underclothing, although she appears to have lost the use of this room in 1871 when the Census office claimed it. Her willingness to undertake such work created financial savings for the institution, and ensured that she exercised considerable control over the work of the inmates and the basic form and size of garments that they made and wore.

Mrs Hicks kept a store of nightgowns, chemises and other garments sewn by the inmates, to be handed out as required. Old clothes that were beyond repair or recycling were taken away by the rag-man, or ended up beneath the floor (Q3215, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:509). New clothes, including dresses and aprons, were also handed out on special occasions such as Christmas and the Queen’s Birthday ‘to those who wanted them’ (Q3213, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:508).

The sewing and repair of garments by the Asylum inmates is also significant in terms of variations to uniform clothing. The women spent their days sewing and patching, and were often in a position to sew or modify their own clothes, or the clothing of friends within the Asylum. They could also personalise garments in small ways, such as with buttons, and make clothes to fit the individual more comfortably. Numerous examples of hand sewing preserved in the collection indicate widely varying skill levels, from very fine and regular stitches to unevenly sewn hems, seams and patches, and the crude darning of stockings. Some of the work was made easier by 1878, when a second-hand treadle sewing machine was purchased, with another in 1880 (Hughes 2004:84). It is probable that the women exercised some control over the clothing they wore, and that they need not have been limited to wearing shapeless, poorly fitting institutional garments.