6

PRIVATE LIVES

Along with the official history and material culture of the institutions occupying the Hyde Park Barracks there are the family histories, private lives and the ephemera of long-term residents and transient individuals who lived or sought refuge there. In this chapter we will examine the archaeological evidence for private or personal activities within the broad machinery of the institution. We begin with a brief biography of the rise and fall of the most significant individual associated with the Hyde Park Barracks during the women’s phases of occupation: Matron Lucy Hicks. A great deal of research on the Applewhaite-Hicks family has been undertaken by Joy Hughes (2004:144–178) and we draw on that work here.

THE APPLEWHAITE-HICKS FAMILY

Matron Lucy Hannah Langdon, later Applewhaite and then Hicks, was born on 5 November 1833 in George Street North, The Rocks. She was the sixth child of English immigrants John and Mary Langdon (née Trinder), who had married in London c.1823 and migrated to New South Wales in 1828. They arrived with their three young sons, John and William (born in England) and Chadwick, born at sea on the voyage. Lucy was one of four children born in the colony; the others were Elizabeth (1831), Thomas (1832) and Emily Jane (1835) (Hughes 2004:144).

John Langdon was a merchant by trade and established a slaughterhouse on a grant of land at Darling Harbour. He also ran a butcher’s shop in George Street. The business prospered, and in 1831 he obtained a 1280-acre grant of good grazing land in the County of Murray, along with assigned convicts to work it. Two years later he purchased 1280 acres at East Bargo, south of Camden, and was granted one more assigned convict (Hughes 2004:145).

John Langdon died in 1835 at the age of 37, when Lucy was two years old. Her mother remarried 18 months later, on 29 March 1837, wedding Thomas Holmes. Also a butcher, Holmes invested in Sydney property, with allotments in George Street, Glebe and Burwood, along with holdings near Auckland in New Zealand. He also set up the three Langdon sons in business — John and Chadwick as butchers, and William in his other enterprises. The three Langdon daughters — Elizabeth, Lucy and Emily — received a good education that included music lessons (Hughes 2004:145–146).

Thomas Holmes was also a founder of the FitzRoy Iron Mining Company, which established Australia’s first blast-furnace for iron smelting near Mittagong (Jack and Cremin 1994:14–32). He sent specimens of iron to Bristol, where the iron was highly regarded (Askew 1857:312), for manufacture into knife-blades. One of his partners in the mining company was John Conrad Korff, who married the eldest Langdon daughter, Elizabeth, in 1847 (Hughes 2004:147).

At the age of 16, Lucy married the 30-year-old, Barbados-born English mariner, John Lithcot (also spelt Lythcote and Lythcot) Applewhaite on 12 September 1849, at the Anglican Christ Church St Laurence in George Street, Sydney. John Applewhaite was master of the William Hyde, a 532-ton barque built in 1841 that carried cargo and passengers. The couple spent the early years of their marriage at sea and in port in London and Adelaide, as well as in Lyttelton and New Plymouth in New Zealand. Their eldest daughter Mary was born aboard ship at Port Adelaide in 1850, and their son Phillip was also born on board in May 1852 (Hughes 2004:148; Askew 1857:310; NSW Death Certificate 1890/11629).

An account of one of their journeys from England to New Zealand was published in the Lyttelton Times by one of the passengers, and this gives a sense of what life was like for the family in the first years of their marriage:

The William Hyde weighed anchor at Deal on the morning of Tuesday, October 21, 1851, and having a favourable wind went at once down the English Channel, and across that terror of English landsmen, the Bay of Biscay, where the wind and sea were both somewhat rough. On October 31 we passed Madeira at midnight, bearing S.E. by E. On November 8 we caught a shark, from which some excellent steaks were cut. On the 14th we sighted San Antonio (Cape Verde), bearing E. by S. and distant by about 40 miles. From thence to the Line the N.E. trades were very light, and it was not until November 25, thirty-five days from Plymouth that we passed the Equator … From this point to about lat. S. 42.2 and E. long. 54.8 our course was slow and uninteresting, the S.E. trades entirely failing us. To beguile the time, however, the play of the “Merchant of Venice” was got up, and 80performed before the passengers and crew … On December 19, 47 days from Plymouth, we passed the meridian of Greenwich, lat. 34.19. On Xmas Day we were off the Cape, and the day was spent as nearly as possible after the Old English fashion. On New Year’s Day the children of the cuddy and the forecabin had an entertainment in the cuddy, and the children of the steerage passengers were regaled with fruit, tarts, cakes and wine on the quarter deck. On Saturday, January 3, we made our best run during the voyage, having gone over 281 miles in twenty four hours, and from this time a good pace was kept up to Stewart Island, which we sighted on Saturday January 30, at break of day, lying N.E. by E., passing it so close as not to see the “Traps”. At noon of the same day, we were off Otago where the wind headed us and kept us out till the 5th, when we safely anchored in Port Victoria, having accomplished our passage under the protection of a merciful Providence without a single casualty or serious disagreement and all in good health. (Lyttelton Times 14 February 1852, transcribed by Judy Clark; http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~nzbound/wmhyde.htm, retrieved 12 April 2011)

Another account of a voyage aboard the William Hyde was written by John Askew, a steerage passenger from Newcastle (NSW) to New Zealand in 1853. Askew noted that Captain Applewhaite was ‘a stout, broad-faced, good-looking Englishman, about 30 years of age, a thorough son of the sea, [and] as strong as two ordinary men’. He describes Lucy Applewhaite admiringly as:

… a pretty little woman, a native of Sydney, and about 22 years of age. She had in perfection the finely chiselled features so peculiar to the women of Sydney. Her hair was dark brown, and was shaded back in luxuriant tresses, fastened behind with a plain black ribbon. She generally wore a black satin dress, and a small white collar round her neck. Her name was Lucy, and she was as amiable as beautiful. (Askew 1857:311; see also Hughes 2004:148–149))

During heavy weather out of Auckland, pens for the sick sheep were set up in the ship’s cuddy, where Lucy ‘nursed them as carefully as ever Miss Nightingale nursed the wounded soldiers at Scutari; but all to no purpose, die they would and did, in spite of all her efforts to save them’ (Askew 1857:318).

The William Hyde left Auckland on 22 April 1853, bound for Melbourne, but the ship ran aground when approaching The Bluff on New Zealand’s south island. After a delay the ship docked in Melbourne on 28 May, but thereafter it disappears from shipping records for some years, suggesting that it had sustained sufficient damage to warrant substantial repairs. The Applewhaite family left the ship in Melbourne, and their lives at sea were now largely behind them (Hughes 2004:150). John continued to captain ships plying the inter-colonial trade and established an auctioneer’s business which became insolvent in September 1854 (The Argus 14 September 1854, p.8).

Over the next year or two John and Lucy shuttled back and forth between Sydney and Melbourne. Their third child, Elizabeth, was born in Glebe, Sydney, in April 1855, followed by two more daughters: Lucy Holmes, who died soon after birth in 1857, and Emily, born in 1858.29 By 1859, John and his brother Edward Applewhaite were keeping livery stables in Pitt Street when they were declared insolvent.30 The register of assets at the stables included a mail phaeton (carriage), 2 horse harnesses, a chaff cutter and wheel barrow, all which were the property of Mr Holmes, Lucy’s stepfather (Supreme Court, Insolvency Papers, SRNSW 4578; Hughes 2004:150).

When Lucy Applewhaite was appointed to the vacant position of Matron at the Hyde Park Immigration Depot in May 1861, with an annual salary of £70, it must have seemed like the best solution to the Applewhaite family’s financial worries. Her appointment appears to have had the support of the Colonial Secretary, Charles Cowper, who knew the family through Lucy’s stepfather, Thomas Holmes, and their shared interest in the FitzRoy Ironworks (Hughes 2004:151). The family moved into the Barracks, occupying quarters in the two western rooms on Level 2, overlooking the entrance on Macquarie Street. A few months later the family’s fortunes improved further when John Applewhaite was appointed as an ‘extra’ clerk at the Immigration Agent’s office at the Hyde Park Barracks, at a salary of 10 shillings per day (Hughes 2004:152).

The position of matron was one of the few ‘respectable’ options available to women of Lucy’s background who wanted or needed to work. Such appointments tended to be reserved for middle-class women of respectable upbringing and credentials, which meant married women or widows were preferred (Alford 1984:184). Lucy was only 27 years old at the time, and the mother of four children. Although she had no experience as a matron, her

81years as a ship captain’s wife had provided her with numerous challenges, including giving birth at sea, coping with extreme weather and emergencies, and living in cramped quarters, with small children, for extended periods. As a frequent visitor to foreign and British ports, she could empathise with the problems faced by young women migrating around the world to face the challenges of setting up a new life in Australia (Hughes 2004:152).

In February 1862 the government established an Asylum for Infirm and Destitute Women at the Barracks, appointing John Applewhaite as master of the new institution and Lucy as Matron — a position held in conjunction with her role in the Immigration Depot. The master’s duties were mostly clerical and involved maintaining a register of inmates’ admissions and discharges, and recording the receipt and issue of all stores including food, clothing and medical comforts (Hughes 2004:152). From 1863 he received an annual salary of £100 for the role.

As Matron, however, Lucy Applewhaite was responsible for the everyday operation of the Asylum and the management of at least 150 inmates. For the Asylum, she supervised the preparation of meals, the personal hygiene of the inmates, and the cleanliness of the premises and utensils, and enforced discipline. The only paid employees were the head laundress, Nancy Bell, and a nurse, Julia Williams (noted in the Switson trial, SMH 29–31 August 1866), each paid 12s a week. In August 1862 Lucy gave birth to her sixth child, John, who died the following year, all the while caring for her other young children and supervising shiploads of immigrant women as they arrived in the Depot.

With the benefit and security of government positions, as well as having living quarters within the Barracks, John and Lucy Applewhaite ostensibly had the income to maintain a middle-class standard of living for their family, an opportunity they may have lacked during the previous few years.

The family, however, appear to have been living beyond their means, as John Applewhaite faced a range of debts and financial disputes during this period. In 1865 a claim against his estate was upheld in the Supreme Court for non-payment of several promissory notes totalling £65 8s. 4d.31 while in the following year the District Court granted writs against him totalling £36.

In January 1867, he filed for insolvency (his fourth in 13 years) with debts of over £500. His petition outlined the reason for his ‘pecuniary embarrassment’ as Hughes (2004:157) put it:

Firstly, when I originally obtained the Government Appointment which I now hold I was through previous business misfortunes in greatly involved circumstances and had then no immediate means of satisfying my Creditors. I was at time in the full belief that I was entitled to Considerable landed property at Canterbury in New Zealand of which I have since been fraudulently dispossessed and the value of which I estimated at between six and seven thousand pounds.

Secondly, From the date of such appointment until the present time I have been continually and unfortunately in the hands of money lenders to whom I was absolutely compelled to apply for loans at most exorbitant interest in order to satisfy their claims of the more clamorous of my old creditors beside which I have been put to very heavy law expenses both in the Supreme and District courts in causes arising from these claims.

Thirdly There are now several writs of Casa out against me and I am duly threatened that they will be put in force.

Fourthly I have had death and much sickness in my family and have been at great expenses arising from them.

It is quite impossible for me at this time simultaneously to pay off these pressing liability and I have no alternative but to sequestrate my estate and seek the protection of this honourable court.

J L Applewhaite

(4 January 1869, NSW Supreme Court, Insolvency Papers, SRNSW 2/9226, no. 8090)

Hughes (2004:156) notes that most of the debts on file were incurred since 1862, and reflect a relatively affluent consumption pattern appropriate for a middle-class family in a respectable position. Between 1861 and 1866 they spent £186 on childrens’ boots and shoes, gloves, hats, silk braids and trimmings, and mourning clothes32 from several Sydney retailers: David Jones, Thompson & Giles on George Street, McArthur’s on York Street, Farmer’s and Madame Ponder of Maison de Paris on George Street. This was alongside debts of £70 owed to grocers and butchers and £50 owed to a private doctor for medical attendance and Pinhey’s pharmacy for medicines. The fact that the Applewhaites were able to continue to accumulate and sustain relatively large accounts may well be

82an indicator of their public respectability, or their ability to reassure these shopkeepers that they had the means to meet their expenses. It may be that they were spending in the comforting expectation of £7,000 worth of property if John’s claim of being defrauded of a Canterbury estate are to be believed.33

The Applewhaites had no landed property and their assets totalled a paltry £26 (£16 in furniture, £10 in wearing apparel). We know this from a poorly written inventory taken in evidence for the court, and conducted at the Applewhaites’ quarters in the Barracks on 12 January 1867. The inventory lists a bird and cage, cruet stand, chiffonier and two dumb waiters, along with crockery and glassware. It identifies three rooms used by the family: one main ‘Room’, a Bedroom and Kitchen. It does not mention the children’s bed furnishings. Hughes argues that the inventory is probably an inadequate record of the family’s domestic possessions, and suggests that ‘valuable items had been sold or perhaps spirited away to another part of the building’ (2004:156). The taking of this inventory was part of the Applewhaites attempts at averting their own destitution. We will never know if the inmates of the Barracks were aware of the precarious financial position of the Master and Matron of their institution.

Applewhaite agreed to pay off his creditors at a monthly rate, but resisted and delayed payments until the matter disappears from the records (Hughes 2004:157). In 1868 Lucy gave birth to another son, William, and during the following year, on 27 May, John Applewhaite died of heart disease, at the age of 49, after almost 20 years of marriage to Lucy. His death certificate shows that he was suffering from ‘syncope’ (cardiac failure) and ‘fatty degeneration of the heart’ for a period of three months and that he was attended by the Asylum’s dispenser, Dr George Walker. Like most of the inmates, he was buried promptly, on the following day, 28 May. He left Lucy with six children, aged between 18 years and 11 months.

The Government Asylums Board acknowledged ‘the skill, energy, and tact, displayed by Mrs Applewhaite in the fulfilment of her duties’, and recommended the abolition of the master’s position. In June 1869, Lucy took charge of the Asylum as an independent matron, at a salary of £150 per annum, equal to the male masters in charge of the Liverpool and Parramatta asylums. This was offset by the reduction in salary for her duties as matron of the Immigration Depot, from £100 to £20, on account of the decline in immigrant arrivals (Hughes 2004:158).

Just over a year later, on 4 June 1870, Lucy married English-born William Henry Hicks at St James’s Anglican Church, opposite the Asylum. Hicks was a family friend, and had assisted the Applewhaites during their financial difficulties in 1867 by providing £150 surety for one of their debts. Their last child, William Henry Applewhaite, appears to have been named in Hicks’s honour (Hughes 2004:160).

William Hicks was born c.1827 in Caston, Norfolk, the son of John Raby Hicks. He described himself as a bachelor, but he had previously married a Charlotte Bailey in London around 1850 (Hughes 2004:159–160). In 1851 he was ordained a deacon at Salisbury and a priest the following year. From 1853 to 1855 he was curate of Ramsbury in Wiltshire. He graduated from Cambridge University in 1855 as Bachelor of Laws, and until 1864 served as vicar of Watton in Norfolk. Hicks was also the author of A Concise View of the Doctrine of the Baptismal Regeneration (1856) and numerous tracts (Hughes 2004:161; Venn 1947:360). Although his name appeared in the Clergy List until 1885, he migrated to Australia around 1861, and spent time in New Zealand on business. Hicks applied unsuccessfully for various government positions. In 1872, he embarked on a capitalist venture to operate a quartz-crushing operation on the goldfields of northwestern New South Wales, in Ironbarks (present-day Stuart Town), near Wellington (SMH 31 May 1872, p.5, 12 June 1872, p.7). He published reports about his trips there in the Australian Town and Country Journal in 1873, and in numerous letters to the Editor (e.g. SMH 22 June 1872, 21 August 1873).

Lucy was 37 at the time of her marriage to William, and together they had five children, only one of whom survived into old age: Lucy E. M. R. (b. Sydney 1871, d. 1892), John Raby (b. 1874, d. 1941), Claud A. R. (b. 1876, d. 1876), Kate R. (b. 1878, d. 1878) and Francis A. R. (b. 1879, d. 1896). All five were born at the Hyde Park Barracks while Lucy continued to run both the Asylum and Immigration Depot. She was 46 when she had her fourteenth and last child, Francis, in 1879. It was around this time that she may have begun employing a governess to look after the children so she could devote herself to the care of the Depot and Asylum (Hughes 2004:208).

On 1 January 1875, Lucy’s 24-year-old daughter Mary Applewhaite, who worked as her mother’s unpaid assistant, was appointed to the newly created position of sub-matron of the Asylum, with an annual salary of £50. There was discussion, at this time, about erecting new quarters for Matron Hicks and her growing family on the Macquarie Street frontage of the Barracks complex, but these plans did not eventuate. However, during 1882, the matron’s quarters on Level 2 were given over to provide additional accommodation for the inmates (Government Asylums Board 1882:2). By 1883 the Hicks family was living at 143 Phillip Street, just a block from the Asylum, but it is unknown whether this was a private or government-sponsored arrangement.

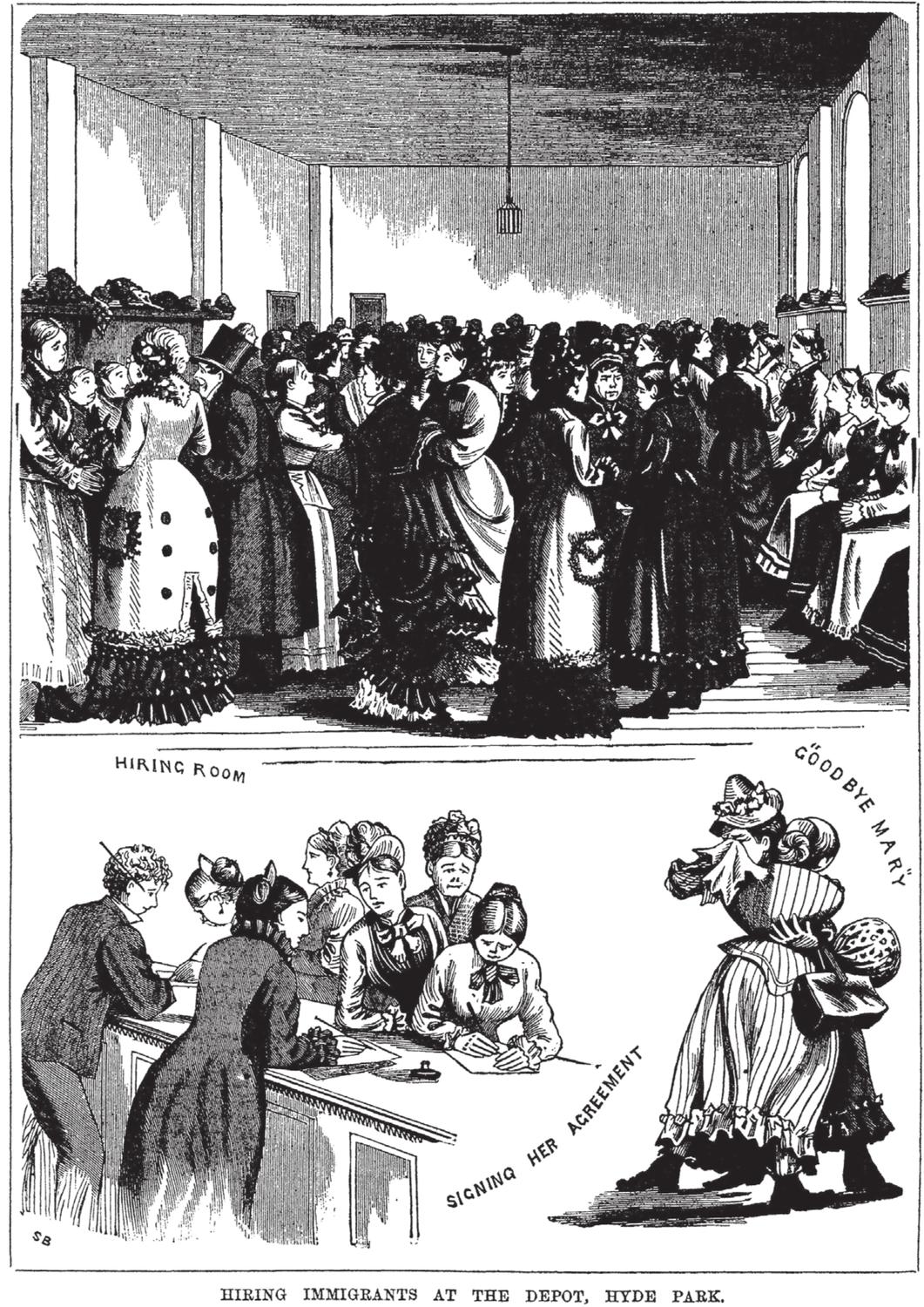

Immigrant ships continued to arrive regularly: 13 vessels in 1878 and 12 in 1879. The Australian Town and Country Journal of 19 July 1879 described 83the crowded scene in the hiring room, where ‘two hundred ladies in want of servants’ sought to claim one of the 50 female immigrants from the Nineveh, a process that apparently took less than a quarter of an hour. Lucy Hicks was shown, fashionably dressed, behind the counter talking to an employer. A few months later, on hiring day on 31 October for the single women off the Strathleven, the Evening News recorded that Mrs Hicks ‘was untiring in her exertions to satisfy all parties concerned’.

Figure 6.1: Scenes from the Hiring Room at the Hyde Park Barracks Immigration Depot (Town and Country Journal 19 July 1879).

Earlier in 1879 Lucy’s daughter, Helen Applewhaite had married Thomas William Garrett, a solicitor and prominent member of the Australian and New South Wales cricket teams. His father was Thomas Garrett, MLA for Camden, a former newspaper proprietor, who had been involved in Hicks’ gold mining venture in Ironbarks (SMH 31 May 1872). Between 1878 and 1881 William Hicks was joint proprietor and editor of the satirical political Sydney Punch (Hughes 2004:171).

Mary Applewhaite, Lucy’s daughter and the submatron, died of inflammation of the lungs on 21 September 1885, aged 34. She had spent the best part of 20 years — her entire working life — in the service of the Asylum and Depot. She never married or had children of her own, but instead answered to her mother as the matron, and to the needs of the inmates. While Matron Hicks received high praise during the peak of her own career, it is possible that much of the orderly management of the institution was due to Mary Applewhaite’s untiring efforts. We will never know if she was satisfied with her duties or resented them, but her contribution to the efficient and economic management of the institutions was substantial. Frederic King, Manager of the Government Asylums Board, lamented that ‘in her the inmates lost an ever kind and sympathising friend, and the Public Service has lost a most faithful and efficient officer’ (Government Asylums Board 1885:1). The inmates contributed to a marble plaque in her memory that was placed in St James’ Church where she worshipped. Memorials of this kind had been banned for many years, but one for Mary was permitted as a special case (SMH 7 84December 1886, p.7). It reads:

Mary Lucy Adelaide Applewhaite, who died 20th September, 1885, aged 34 years. Erected by the inmates of Hyde Park Asylum, in loving remembrance of their late sub-matron and sympathising friend. ‘Inasmuch as ye have done it to one of the least of these, my brethren, ye have done it unto Me.’ St. Matt. XXI., 40. (SMH 7 December 1886, p.7)

This suggests a different kind of relationship between staff and inmates than might be expected in an authoritarian institutional system. When Frederic King informed the Colonial Secretary of Mary’s death, he added that Matron Hicks was dangerously ill and not expected to recover (Hughes 2004:174). However, within a week or so Lucy’s health began to improve. She soon resumed her duties, and her daughter Clara took on the position of sub-matron.

The Hyde Park Asylum closed in February 1886. The inmates, together with Mrs Hicks and her family, moved to the new premises at Newington near Parramatta.

HICKS FAMILY QUARTERS AND ARTEFACT ASSEMBLAGE

Lucy Hicks and her family’s quarters on Level 2 comprised two rooms, each measuring 19 by 35 feet, separated by the western end of the hallway. In 1865 the Colonial Architect installed ceiling boards in the quarters to prevent ‘leakage’ from the hospital wards above. In the following year he replaced the kitchen range, installed in 1848, that was also used by ships’ matrons, and by female immigrants, when only a few were left in the Depot.34

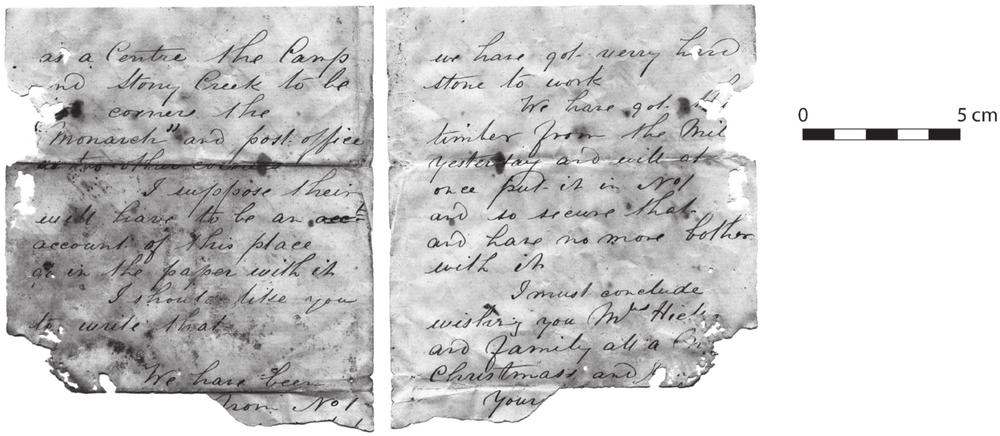

Figure 6.2: Remains of letter probably written to William Hicks (UF3312; P. Crook 2003).

The artefact assemblages in the underfloor spaces of the family’s quarters differ in important ways from material in the other rooms of the Barracks. The large quantities of paper and textile offcuts, leather pieces, religious texts and clay tobacco pipes that characterise the spaces occupied by the Depot and Asylum are less evident in the Matron’s quarters. The smaller quantities of discarded or lost items in the quarters may relate to the presence of floor carpets. In 1867, for example, Lucy requested a new carpet to be laid in her ‘parlour’, on the chance that she would receive a visit from Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, who toured the Australian colonies in 1867–68 (McKinlay 1970). Henry Parkes, the Colonial Secretary, doubted the duke would visit Mrs Applewhaite’s parlour, but agreed to the request if a carpet could be found (Hughes 2004:157). This new carpet was presumably intended to replace an older one.

The underfloor material in the matron’s quarters included large numbers of small items such as beads, buttons and pins. The presence of 500 metal sewing pins, for example, indicates that the Applewhaite-Hicks daughters were frequently occupied with sewing and dress-making. Sixty-two buttons and more than 300 small glass beads in various colours were also found, especially in the southern room, which may relate to jewellery or clothing adornment. Slate pencils were also common, with 26 pencil fragments in the family’s quarters and adjacent hallway comprising more than half the Barracks total (n=46).

Some of the artefacts in the Hyde Park Barracks assemblage can be linked to specific members of the Hicks family. A hand-written letter (UF3312) that seems to have been written to William Hicks describes a camp at Stony Creek35 and concludes by wishing ‘you [i.e. William Hicks,] Mrs Hicks and family all a M[erry] Christmas’. Unfortunately, the

85writer’s name has been torn away, but the letter notes that an account of a place or building at Stony Creek ‘should go in the paper’ and probably relates to William Hicks’s article on the goldfields settlement of Ironbarks (near Wellington in northwestern NSW) in 1873 (Figure 6.2). It was probably written by the mine manager, or another associate, in Hicks’ quartz-crushing venture at Stony Creek.

Figure 6.3: Remains of letter probably written by Lucy Hicks (UF17784; P. Crook 2003).

Another, much smaller, scrap was probably written by Lucy herself (UF17784; Figure 6.3). While the bottom half of the signature has torn away, it resembles other documented examples of Lucy’s handwriting. The sentences cannot be fully strung together, but some phrases are identifiable:

… your … uld[have?] …

…

… I must ask yo[ur] …

… to excuse them …

… I never … which …

… I have … paper …

… [ock?] is still up at …

… Strony’s [sic], the Baby …

… [su]ch a dear little …

… and how dear …

… I must conclude …

… love [l… H…ks]

The paper has been folded many times and may have been a note returned to her. It was recovered from the northern ward on Level 2, and while only a few phrases can be made out, it presents a softer, more personal side to the Matron whom we only know from parliamentary inquiries, day books and third-party accounts.

LUCY HICKS

It is difficult to establish just what kind of matron and a person Lucy Hicks was because there are several conflicting reports of her manner and managerial capabilities. Surviving records such as the Day Books for the most part are dry and official, noting requests for ash pits to be cleared, coal to be ordered and other tasks necessary for the management of the institutions. Few remarks offer any glimpse of the personality beyond that of the ‘Matron’. Those that do, especially in her early years at the Barracks, suggest she had a staunch and judgemental attitude toward the women in her care. An entry in an 1862 Day Book by Matron Hicks regarding a sick child, John McMatton, reads:

Mrs McMatton’s child worse in consequence of the Mother’s neglect. She is a most disobedient woman refusing to do everything she is told. Dr Allengbe has just been with it. Inform her that she will be sent away from the Depot if her conduct is again unfavourably noticed. (SRNSW 9/6181a HPB daily reports 1862)

The child died, aged 3 years and 3 months on 2 August 1862 and was buried at 3 pm the same day.

On the other hand, we can see the Matron as her employers did: a competent and energetic woman who was clearly able to respond to the unexpected, such as the arrival, in early 1862, of 150 infirm and destitute women from the Benevolent Asylum, with only a day’s notice (Hughes 2004:152). She coped, it would seem, with her additional new role as matron, on top of her other responsibilities. We have no evidence of her personal response to the situation, but at the age of 29 or so she was capable of meeting the challenge.

The 1873 Inquiry presents Mrs Hicks as a competent, prudent and fair Matron, deftly managing the needs of the swelling numbers of inmates and, most importantly, keeping costs under tight control. While brisk and unsentimental, she also appears to have had some sympathy for ‘the poor old creatures’ under her care, recognising that sick, elderly women required special treatment, and that the increasingly crowded conditions were hardly conducive to the comfort of the inmates. When it was suggested that she was ‘too tender’ towards the women in her care, she responded ‘I think that in a town like Sydney you must have such a place [as the Asylum]’ (Q2382, Public Charities Commission 1874:77). Having been in the job for over a decade, and in full command of both the Depot and Asylum, she had the confidence to politely critique the decisions of the Board, in a manner appropriate to a woman in her position. She moralised about old women whose daughters were prostitutes and boasted about her efforts to prevent drunkards from drinking.

While Lucy Hicks was proudly middle-class, her colonial birth and lack of formal qualifications could have put her on her guard. When Lucy Osburn arrived to take up the position of Lady Superintendent at the Sydney Infirmary in 1868, her training at Florence Nightingale’s school of nursing in London may have been seen as an oblique threat to Lucy Hicks, even though Osburn’s salary was 86a little less than Hicks’ (Hughes 2004:158). Lucy Hicks soon came to resent Osburn’s assumption of superiority (Godden 2006:89; see also Barber and Shadbolt 1996:189).

A few years later, in 1878, Lucy Hicks still managed the controlled chaos of hiring days with vigour. Journalist John Stanley James noted ‘… the presiding genius was Mrs. Hicks, the matron, who bustled about directing everybody what to do’ (SMH 24 May 1878, p.5). When single women from the Samuel Plimsoll arrived at the Depot in July the following year, the Evening News reported that ‘no one … could possibly come away without having admired the business-like style and kindliness displayed by the matron, Mrs. Hicks’ (Evening News 3 July 1879). A few weeks later she was depicted by the Australian Town and Country Journal (19 July 1879; Figure 6.1) as firmly in command behind the counter during the chaos of a hiring day.

By 1886, however, a very different portrait of Matron Hicks was emerging. In January 1886, only a month or so before the move to Newington, a hiring day in the Immigration Depot was reported in the Sydney Morning Herald. Lady Carrington, wife of the Governor of New South Wales, had expressed a desire to witness the process, but she was initially dissuaded from attending by Mr Wise, the Immigration Agent, who feared she would be shocked by what she saw (SMH 21 January 1886, p.9). Matron Hicks was also accused by bystanders of favouring a politician with special treatment in securing a servant, while 400 members of the public fought to gain the services of 104 young women from the Parthia. In an ‘exciting dialogue’ with her accuser, Hicks responded that ‘I hope I may drop dead if that’s true’ (SMH 21 January 1886, p.7). Explanations followed that presumably smoothed things over, but the image of government officials barely in control of a hiring process that had been occurring, by then for decades, did not reflect well on Hicks’ capacity for managing the Depot.

Given her husband’s connections with the Sydney press, it is difficult to ascertain whether the flattering accounts from the 1870s were possibly the view of a trusted friend (or even Hicks himself?) which overlooked any problems or preferential treatment on hiring days. With regard to later accounts, and criticisms of her behaviour, was Matron Hicks caught off-guard, or was there a genuine decline in standards?

A few months later, during hearings of the Government Asylums Inquiry Board, Lucy Hicks was subjected to further sustained criticism:

There appears also ground for thinking that had the matron’s attention been less occupied in her family concerns she would have been at liberty to better attend to her official duties; also, had she been supported by a more efficient sub-matron, many defects in matters of detail would have been forced on her notice, and might have been quickly rectified.

Miss [Clara] Applewhaite, the daughter of Mrs. Hicks, occupies an unauthorised position in the Asylum, and her presence interferes with the responsibilities which properly fall on the matron and sub-matron. (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:445–446).

Hicks was accused of numerous improprieties by some of the inmates, and by members of the Ladies Board. She was accused of withholding basic provisions — rice, sago, arrowroot and gruel — from sick inmates, and a patient insinuated that Hicks had sold hundreds of nightgowns, chemises and dresses belonging to the Asylum (Q2837, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:501). In addition she was alleged to have fleeced dead inmates of their pocket change and savings, and to have impersonated one of the Ladies Board members, Lady Martin, to test the loyalty of the inmates or find out what their accusations against her would be (Q2786, Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:500). Most damagingly, she was also accused, not by the inmates but by the evangelical visitors, of being drunk.

To counter such reports by these ‘stooges’ or ‘halfwits’ as Matron Hicks called many of them, there were several accounts by witnesses of her devoted efforts, including Elizabeth Cross, inmate of 10 years: ‘She is a good matron, God bless her!’ (Q3050, p.505). Frederic King, Manager of Government Asylums and Lucy Hicks’ superior, denied ever having seen her intoxicated, and generally endorsed her performance as matron:

… she is competent, especially from the aptitude with which she deals with those old women. It requires a peculiar person to deal with these old women, and although Mrs. Hicks might not be suitable in all respects for the position, her tact is valuable. (Q3643, p.519)

Hicks was also unconcerned that poisonous medicines — including morphia — stood on open shelves on wards, and that they were dispensed by inmates who could not read: ‘You could not get educated people to do filthy dirty work’ (p.528). She rarely accompanied the doctor on rounds, and she had no idea of the treatment individual women received or what he prescribed for them (Q3792–3796, pp.523–524). Nevertheless, her long-standing insistence on sanitation and hygiene had helped shield the inmates from the epidemics of scarlet fever, smallpox and typhoid that had swept Sydney from time to time.

The glowing approval of Mrs Hicks in 1873 seems genuine enough — just as legitimate as the criticisms brought against her 13 years later. Lucy Hicks may have been physically and emotionally 87worn out by the time she arrived at Newington. She was in her early fifties, had suffered an unknown illness in 1885 that brought her close to death, and in addition to giving birth to 14 children, she had endured the sadness of burying six of them, and a husband of 20 years, while at Hyde Park Barracks.

The death of her daughter, Mary Lucy Applewhaite, was not only a personal loss to Lucy, but also it would be a great loss to the Asylum. Mary had been sub-matron at the Asylum for at least seven years in an official capacity, but had been assisting her mother with its management for many years prior. It is likely that while Matron Hicks was on the stand answering questions during the first inquiry, it was in fact her daughter (or the efforts of all her older children) that had maintained the excellent state of the Asylum up until that time.

The emotional difficulty endured by Mrs Hicks at this time was also exacerbated by Supreme Court proceedings in 1885 concerning the distribution of her late step-father’s estate. The following year, after the exhausting relocation to Newington, the last of her siblings, John Langdon, died. At Newington, in addition to six of her children in residence, she often cared for her three grandchildren and the son of her late sister (Hughes 2004:210).

At the Hyde Park Asylum, Lucy Hicks had the support of a diligent medical officer and her daughter Mary as a dedicated and competent sub-matron, but at Newington she had neither of these. The Board lambasted the efforts of the medical officer at Newington, Dr Rowling, as ‘irregular, careless, perfunctory’ (Government Asylums Inquiry Board 1887:430), while Clara Applewhaite seems to have lacked the competence of her late sister. At Hyde Park Barracks everyone was under the same roof (until 1883) and Mrs Hicks could maintain effective oversight, but at Newington the matron’s quarters were too far removed from the wards and dormitories to ensure effective supervision.

Matron Lucy Hicks was also the victim of changing circumstances in public relief. The Hyde Park Asylum had been established as a temporary refuge for infirm and destitute women, but it evolved into a convalescent hospital where half the inmates were bedridden with a range of diseases and terminal illnesses requiring professional nursing care. The number of inmates increased inexorably over the years, as the condition of the building declined. The government ignored the changing nature of the Asylum, and it was thanks to Mrs Hicks and her family that the system kept going for as long as it did. It took the move to Newington and an official inquiry to make the collapse of the system publicly known.

In 1888, the Colonial Secretary, acting on the findings of the Government Asylums Inquiry Board, forcibly retired Lucy Hicks from her position as matron of the Newington Asylum. She received a substantial pension of £145 per annum in recognition of her long and devoted service. The family moved to Strathfield, where her husband, William Hicks, died in 1894 following months of illness. Lucy died on 14 July 1909, aged 75, survived by only five of her fourteen children (NSW Death Registration 1909/8648).

MARKED GOODS: OWNERSHIP AND IDENTIFICATION

While Matron Hicks and her family had the most enduring impact on the Asylum and Immigration Depot, thousands of individual women passed through the doors of both institutions. As we discussed in ‘The Inmates’, we know the names of only one hundred or so of these women from historical records, and the archaeological record offers the names of a few more.

Artefacts marked with individuals’ names are very rare finds in archaeological contexts. Two have been identified in the Cumberland and Gloucester Streets assemblage of 375,000 sherds in The Rocks (a name stamp for Charles Carlson [CUGL52811] and a tin measure owned by ‘G. Briggs’ [CUGL52720], see also Iacono 1999:85) and others are known (Crook 2008:228). More than a dozen examples were recovered from the underfloor assemblage at the Hyde Park Barracks (Table 6.1).

Names that appeared on medicinal vessels were noted previously, but other unique examples have also been identified. These include a name stamp marked ‘T Brown’ and a lace-edge handkerchief with ‘M Probert’ hand-written in ink on one corner. Owners’ names were also hand-written on the inside of 3 religious pocket books, all of which were found close together in the north-eastern dormitory on Level 2 (UF28, UF8225 and UF8226). Two pre-date the establishment of the Asylum and these may represent second-hand donations or possessions brought into the institution, rather than representing the names of asylum or immigrant women. They may also have belonged to the institution’s library of religious tracts.

A strip of wood from the landing on Level 2 adjacent to the Matron’s quarters is marked with the handwritten name ‘… [indeterminate] Hicks’ (UF4282), while another artefact marked with an individual’s name is a luggage tag with the inscription ‘Francis H[…re]ll’.

88

| Item | Individual | Artefact | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| UG1058 | T Brown | Name stamp marked ‘T Brown’. | L3 |

| UF11500 | M Probert | Lace edged handkerchief with ‘M Probert’ handwritten in ink on one corner. | L3-3: JG10 JS1 |

| UF6624 | F Cunningham | Pharmaceutical bottle marked: ‘HYDE PARK ASYLUM / Name F Cunningham / Age [blank] / Date of Admission 21 May / The Lotion / … Cunningham’. | L3-1: JG16 JS10 |

| UF26 | Alice Fry | Gin bottle re-used for medicinal purposes: ‘Hyde Park Asylum / Name … Alice Fry / Age … [nil] / Date of Admission … [nil / … [unid]’. | L2-6: JG36 JS13 |

| UF5479 | Alice Peacock | Rectangular cotton fragment (52x38mm) with ‘Alice Peacock’ handwritten in cursive style. Possibly part of a name tag or a marker on a larger piece of fabric. | L2-2: JG51 JS3 |

| UF8226 | Ann Sarran | Small leather-bound, hard cover religious book, with brown cursive script on inside front cover ‘Ann Sarran [indeterminate]. | L2-3: JG27 JS4 |

| UF8225 | William and Betty Scott? | Hardcover leather-bound pocket companion by the Society of Promoting Christian Knowledge, with lead pencil and ink on the lining of the back cover: ‘William [surname indet]’ & ‘[Betty Scott?]’; and dates 1830, 1836 [twice] and 1837. | L2-3: JG27 JS3 |

| UF4372 | Francis | Cardboard tag with handwritten script ‘Francis H… [re?]ll’. | L3-5: JG3 JS2 |

| UF6718 | Hanna, Catherine, Alice | Scrap of blue paper with handwritten list of names, no surnames preserved. | L3-7: JG13 JS1 |

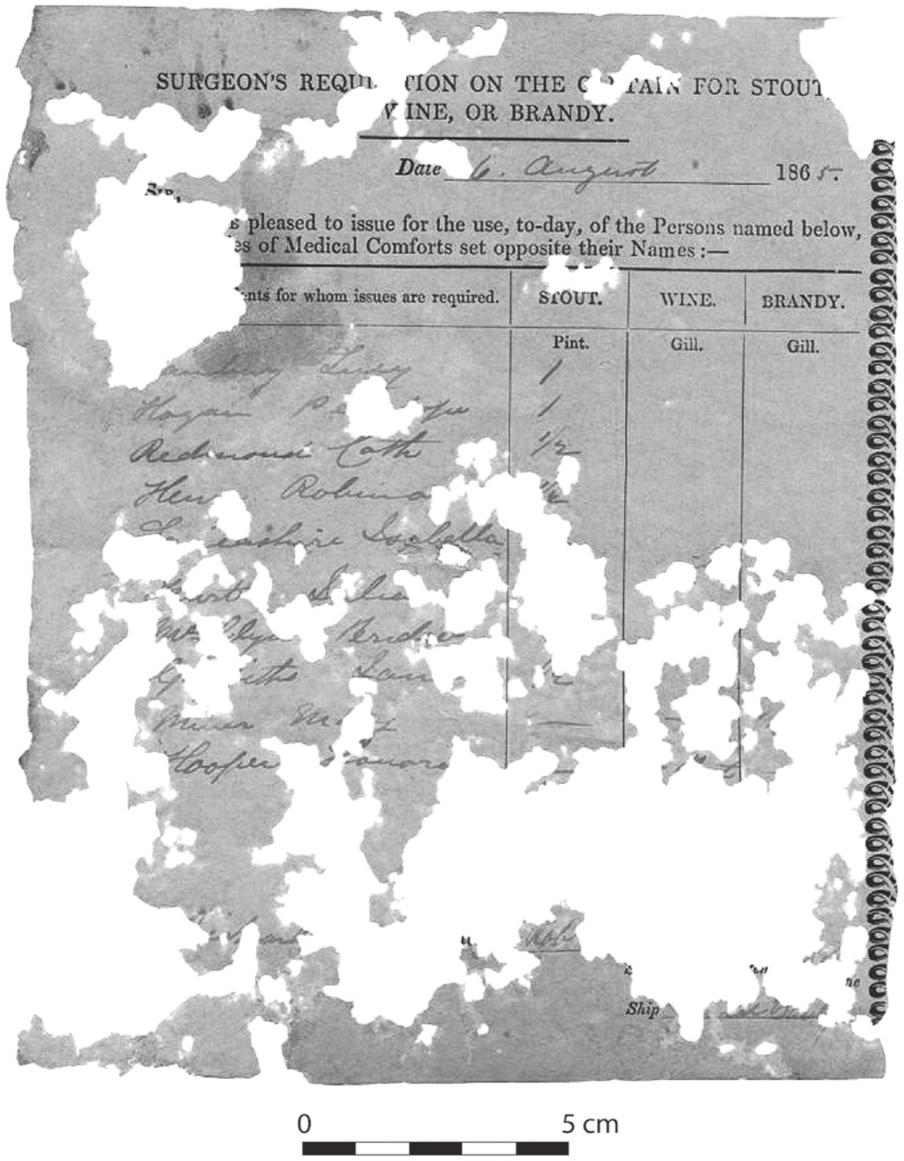

| UF207 | Cath[erine] Redmond, Isabella Lancashire | Printed form ‘Surgeon’s Requisition on the C[ap]tain for Stout, Wine, or Brandy / Date 6 August 1865 / [indet] Lucy / Hagan? [indet] / Redmond Cath[erine] / Hew? Robina / Lancashire Isabella / …t Julia? / … / G[riff]iths Jane / Miner M[ar]y / Hooper Honora …’. | Unstrat. |

| UF28 | Thomas Bagnall | Book with embossed leather cover from British and Foreign Bible Society, and handwritten on inside cover: ‘Thomas Bagnalls Book 1837’. | L2-3: JG27 JS3 |

| UF17391 | Francis? Grace Bishop | Two fragments of pale blue paper with handwritten brown ink: ‘… is Grace / Fl[?]ancis / …ishop / Bishop. | L3-6: JG39 JS3 |

| UF17601 | Mrs Harris | Circular wooden disk with handwritten brown ink: ‘The Ointment Mrs Harris’. | L3-6: JG39 JS4 |

| UF17946 | R D Ward | Printed form for rations to inmates, including arrowroot and sago, porter, wine, brandy, rum and milk, dated 1875, with handwritten ‘yesterday’ and signed by R D Ward (Surgeon). | L3-3: JG9 JS11 |

| UF4282 | … Hicks | Strip of wood with handwritten ink ‘[indeterminate] Hicks’. | L2-2: JG51 JS3 |

| UF7405 | Blanche Ellis | Scrap of paper with name and address on both sides: ‘Miss Blanche Ellis / No 41 / Cedron / Regent St / Paddington’. | L2-1: JG22 JS10 |

Table 6.1: Artefacts marked with the names individual inmates, immigrants and other unknown persons.

Two of the women could be identified from medicinal bottles as inmates of the Asylum. Francis Cunningham is on the list of inmates transferred from the Benevolent Asylum in 1862, but no more is known of her life. Alice Fry was not recorded on any of the inmate lists, but her death certificate lists her address as Hyde Park Asylum. She died on 5 February 1868 of a uterine tumour, aged 56 years.36

The remains of several official blue forms reveal the names of a number of immigrant women who arrived on the General Caulfield in August 1865 (UF131, UF132 and UF207; Figure 6.4). The ‘Surgeon’s Requisition on the Captain for Stout, 89Wine, or Brandy’ allowed for 1 pint or ½ pint of stout to women including Cath[erine] Redmond, Isabella Lancashire, Jane Griffiths, Mary Miner and Honora Hooper.

Figure 6.4: Government form regarding medical comforts to immigrants arriving on the General Caulfield in August 1865 (UF207; P. Crook 2003).

EPHEMERA AND KEEPSAKES

In addition to evidence of the daily activities of the institution as a whole, a small number of artefacts from the Hyde Park Barracks assemblage provide insight into the private lives or personal mementoes of the inmates and immigrants. This class of artefacts goes beyond the typical classification of ‘personal’ artefacts in a regular archaeological assemblage — such as perfume bottles and hair care — although these were also present, and includes items revealing unique, individual behaviours.

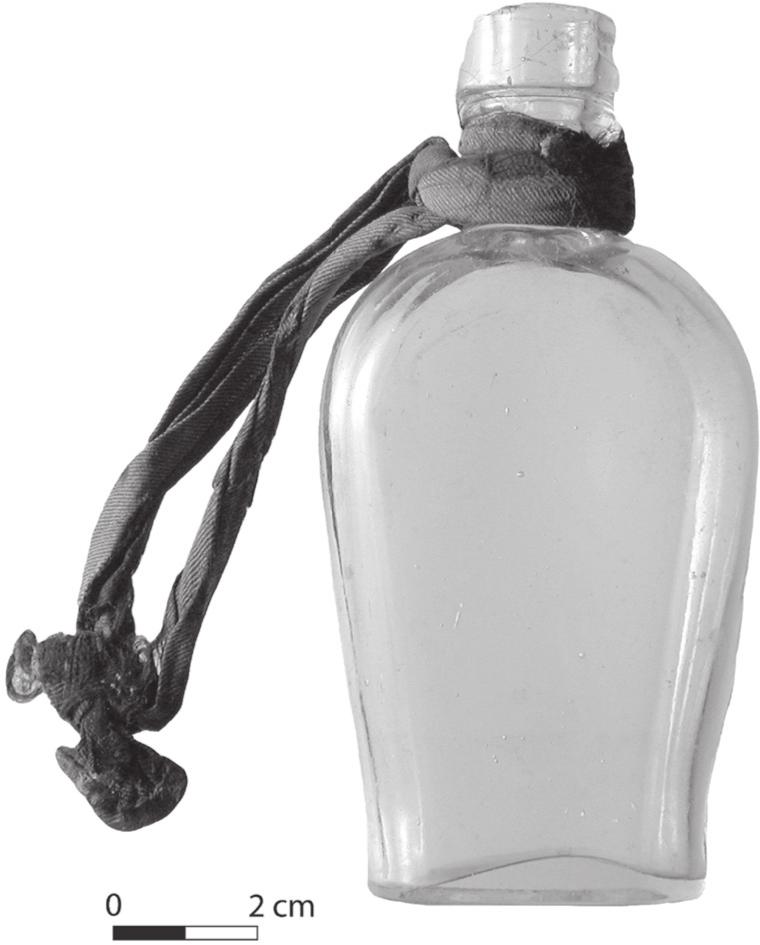

Figure 6.5: Flask bottle with silk strap (UF4321; P. Davies 2009).

The survival of paper and fabric from the assemblage has offered a number of extraordinary finds, objects discarded or lost and preserved as they were in use: a white square cotton handkerchief with an 1869 sixpence tied in one corner (UF160); a flask with a hemmed silk strap (UF4321; Figure 6.5); and a cherry liqueur bottle with a hessian stopper in place of a cork (UF6626).

It is unknown what precise function the coin tied in the hanky served. While it may have been used to weigh down a cover for a jar or bowl, the presence of only one weight suggests the purpose was probably to secure the coin, and then tie it, chatelaine-style, to a skirt or apron. Similarly, it is unknown who may have required a strap to carry the flask, but it too was probably tied to a skirt or worn around the wrist.

The Hessian-stoppered liqueur bottle presents another mystery. While initially made as a container for Danish liqueur and cordial maker, P. F. Heering, the bottle may well have been reused for medicinal tonics or lotions. However, the presence of a makeshift stopper in place of a cork — easily obtained from the Dispensary — and its survival under the floor boards alongside the window in the south-eastern ward on Level 3 (where repaired boards may have been easy to lift) does suggest deliberate concealment of contraband liquor. This area was also used to hide or store a cache of complete tobacco pipes.

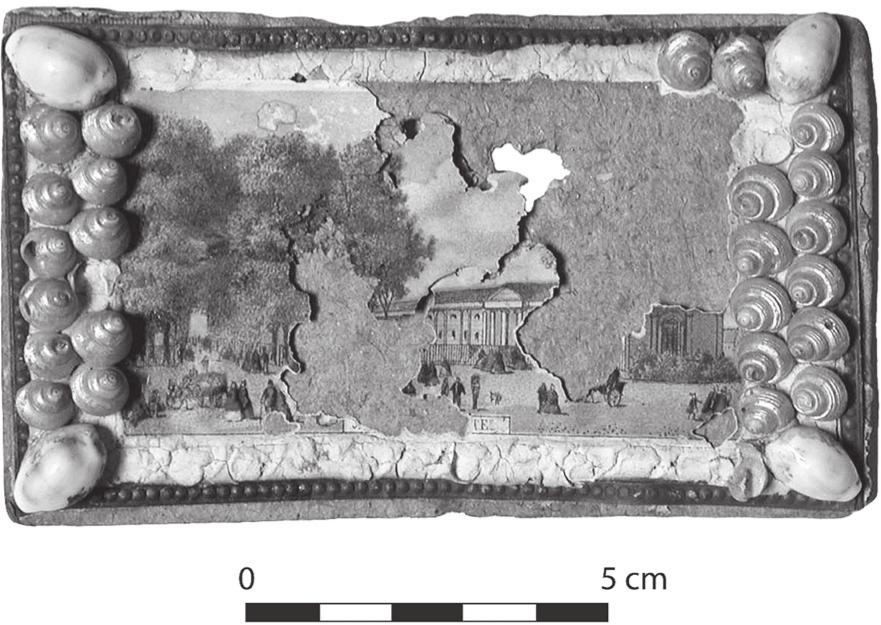

Figure 6.6: Shellcraft cover of a pocket album, possibly of photographs or postcards. The spine (UF3339) is marked ‘FORGET ME NOT’ (UF29; P. Crook 2004).

Another remarkable item is the shellcraft cover of a pocket album, possibly of photographs or postcards (UF29; Figure 6.6), found beneath the floor of the northern dormitory on Level 2. The 90spine is marked ‘FORGET ME NOT’, and the remains of the colour lithograph on the cover depict a park-like scene with strolling figures, bordered with a double row of shells. The item appears to be a keepsake in the Victorian sentimental tradition, and probably belonged to one of the young immigrant women.

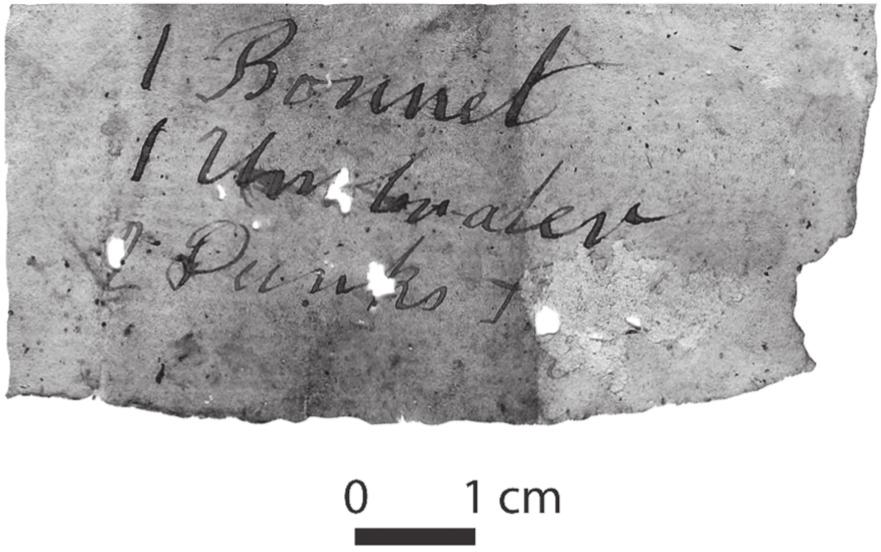

Figure 6.7: Remains of handwritten list, possibly a list of personal possessions (UF6716; P. Davies 2009).

There is also a paper fragment in the collection which appears to be a list of personal possessions (UF6716; Figure 6.7). The handwritten document includes some apparently phonetic spelling: ‘Umbraler’, probably meaning ‘Umbrella’ — particularly if pronounced in a broad Irish or Scots brogue. The ‘2 Punks’ may be old terms for a shoemaker’s punch or awl.

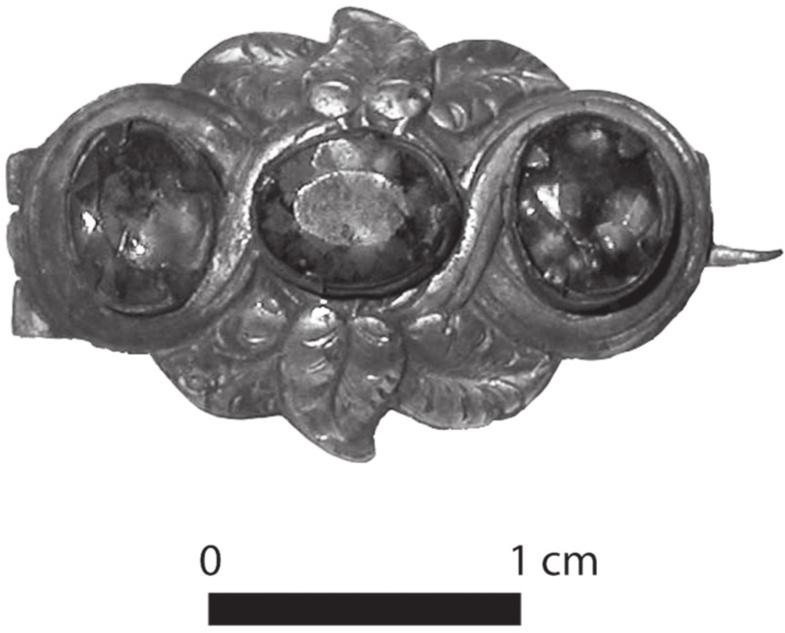

Figure 6.8: Gilt-brass brooch with three pink glass gems (UF64; P. Davies 2010).

Small personal items and jewellery were also found in the underfloor spaces, including brooches (n=5) and gems (n=12). Costume jewellery was popular in the 19th century as a clothing accessory, as friendship mementoes and for mourning (Mezey 2005:30). Brooches from Level 3 include a copper alloy wire wound into an S-shaped double spiral (UF11544) and a gilt-brass brooch with three pink oval-facetted glass gems set within delicately incised leaves (UF64; Figure 6.8). From Level 2 there was a small decorative pin with a waratahshaped shield (UF1608) and a leather brooch in the shape of a butterfly with flowers embroidered on each wing (UF17868). Imitation or paste gems were also found in small numbers on both Level 2 (n=5) and Level 3 (n=7).

| Beads | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | – | 1 | 1 |

| Carnelian | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| Ceramic | – | 14 | 14 |

| Copper alloy | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Glass | 413 | 264 | 677 |

| Wood/seed | 9 | 53 | 62 |

| Unidentified | 19 | 34 | 53 |

| Total | 452 | 368 | 820 |

Table 6.2: Bead materials.

There were large quantities of beads found on both Levels 2 and 3 (Table 6.2), which may have served as cheap jewellery items or decorative flourishes to clothing. Most beads were made of glass and represent a wide range of colours, but there are also examples in wood and ceramic. Some of the wooden beads appear to be modified seeds linked with ferrous chains, while others may derive from lace bobbins or rosaries (see ‘Religious Instruction and Devotion’).

CHILDREN AT THE HYDE PARK BARRACKS

Children were a small but constant presence in the Hyde Park Barracks over the years. The family of Matron Hicks lived in quarters on Level 2, and between 1849 and 1855 the Depot also housed the wives and children of convicts brought out to the colony to be reunited with their husbands and fathers. In addition, the female children of newly arrived immigrant families were often brought to the Barracks to provide relief from the crowded conditions on ship while their parents remained on board in Sydney Harbour (SMH 24 May 1878, p.5). The sojourn of these children in the Barracks, however, was unlikely to have been more than a few days. Several thousand Irish female orphans also passed through the Barracks between 1848 and 1852, but they were unlikely to have possessed much in the way of toys (see ‘Charity and Immigration in 19th-Century NSW’).

Lucy Hicks had 14 children between 1850 and 1879 (Table 6.3), five of whom died at young ages. The family lived at the Barracks from 1861 to 1882 before moving to premises nearby in Phillip Street. During the years of her tenure as Matron of the Depot and Asylum, the Applewhaite-Hicks children knew the Barracks as their home.

A small number of items from the underfloor collection can be directly related to children, including marbles, dolls, game pieces and other 91objects (Table 6.4; Figures 6.9, 6.10, 6.11, 6.12). The most likely source of toys and child-related items is Matron Hicks’ family. Eighteen of the 20 marbles from Level 2, for example, came from the short corridor between the family’s rooms. All but one of the gaming tokens, however, came from the underground collection and may relate more to earlier convict activity.

| Name | Born | Died | Age at death |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mary Lucy Adelaide Applewhaite | 28 Oct. 1850 | 21 Sept. 1885 | 34 years |

| Philip L. Applewhaite | 1852 | 1890 | 38 years |

| Elizabeth J. M. Applewhaite | 1855 | 1931 | 76 years |

| Lucy Holmes Applewhaite | 1857 | 1857 | 4 days |

| Emily A. Applewhaite | 1858 | 1865 | 7 years |

| Helen Alice Maud Applewhaite | c. 1861 | 1944 | 83 years |

| John Charles Benyon Applewhaite | 1862 | 14 Sept. 1863 | 18 months |

| Clara Ann Applewhaite | 1865 | 1939 | 74 years |

| William H. Applewhaite | 1868 | 1940 | 72 years |

| Lucy E. M. R. Hicks | 1871 | 1892 | 20 years |

| John Raby Hicks | 1874 | 1941 | 67 years |

| Claud Arthur Raby Hicks | 15 Feb. 1876 | 16 Feb. 1876 | 1 day |

| Kate R. Hicks | 19 Apr. 1878 | 20 Apr. 1878 | 1 day |

| Francis A. R. Hicks | 1879 | 1896 | 19 years |

Table 6.3: The children of Matron Lucy Hicks, formerly Lucy Applewhaite (Crook and Murray 2006:87–88; Hughes 2004:148–168; NSW Death registration 1909/8648).

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolls and tea sets | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Marbles | 23 | 20 | 12 | 55 |

| Game pieces | 6 | 13 | 2 | 21 |

| Blocks | – | 2 | – | 2 |

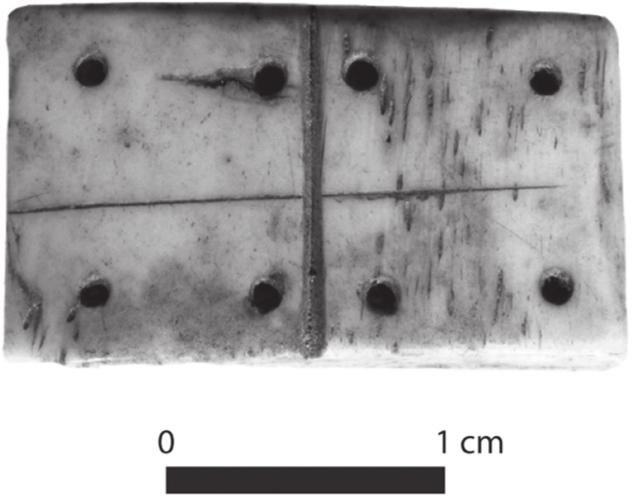

| Dominoes | 2 | 1 | – | 3 |

| Cards | 1 | 6 | 1 | 8 |

| Toys | – | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| Unidentified | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 34 | 49 | 18 | 101 |

Table 6.4: Child-related artefacts.

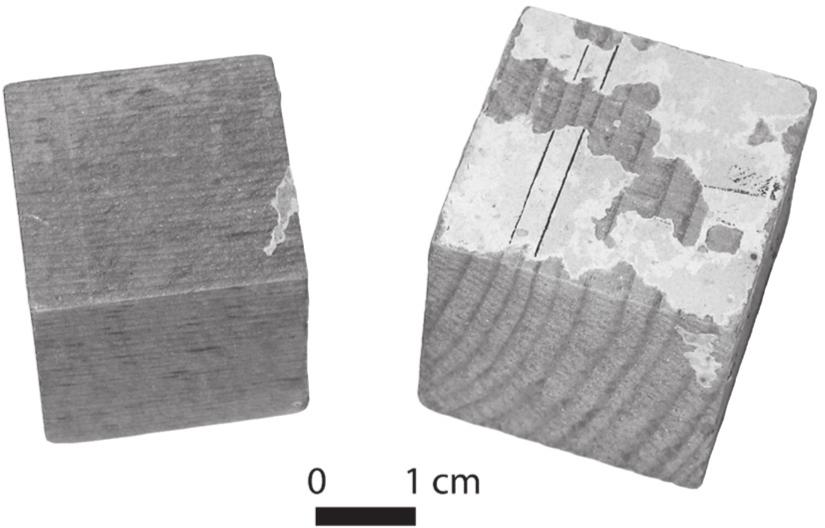

Figure 6.9: Wooden toy blocks with traces of illustrated paper (UF88; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 6.10: Miniature pedestal fruit bowl from doll house set (UF10123; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 6.11:92 Printed cardboard toy figure (UF4285; P. Davies 2010).

Figure 6.12: Small bone domino, probably handmade (UF89; P. Crook 2004).

Figure 6.13: Infant cotton bodice with decorated bands at sleeves, waist and neck (UF930; P. Davies 2009).

A beautifully preserved infant’s bodice was found beneath the Level 3 landing (UF930; Figure 6.13). The garment is hand-sewn in white cotton, with drawstrings at the waist and neck, and embroidered decoration at the neck, sleeves and waist. It may have been worn by several of the Applewhaite-Hicks children, although it is also about the right size for a large doll (White 1966:81–82).

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slate boards | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| Slate pencils | 19 | 40 | 8 | 67 |

| Total | 22 | 44 | 9 | 75 |

Table 6.5: Slate writing equipment.

Slates and slate pencils are also well represented in the underfloor collection. Although these items were used in a wide array of domestic, commercial and educational contexts through the 19th century and beyond, they are most often associated with children and schooling (Davies 2005; Davies and Ellis 2005). The distribution of slates includes 20 pencils and 2 slate board fragments from Matron Hicks’ quarters, suggesting that the Applewhaite-Hicks children used and lost slates in the course of their lessons. It is unclear, however, if they attended a local school or if the older children taught the younger ones, although state elementary education was well established in New South Wales by the 1860s (Barcan 1965:142). Lucy Hicks also employed a governess in the early 1880s to help care for, and possibly teach, her younger children (Hughes 2004:208). Examples of slate pencils from the collection were mostly 4–5.5mm in diameter, typical of standard, mass-produced slate pencils of the period. Only 9 fragments were recovered from Level 3 (Table 6.5), supporting the hypothesis that in the Hyde Park Asylum, slate writing equipment was used by the children in educational activities, rather than writing or record keeping by or for the Asylum women.

29 The birth certificates of Clara and Helen Applewhaite have not been located. Their birth dates have been estimated from death and marriage records.

30 Edward also held the license for the South Head Family Hotel in South Head (SMH 23 May 1859, p.3). It is unknown if John assisted him in this enterprise, but the assets of the hotel are listed in the insolvency register for both the Applewhaite brothers (Supreme Court, Insolvency Papers, SRNSW 4578).

31 Applewhaite was subject to a compulsory sequestration in May 1865 filed by Thomas Gregan and Thomas Brown (NSW Supreme Court, Insolvency Papers, SRNSW 2/9147, no. 7116).

32 The mourning clothes were needed for the deaths of their infant son John in 1863, Lucy’s brother William Langdon and her stepfather Thomas Holmes in 1864, along with the death of their seven-year-old daughter Emily in 1865 (Hughes 2004:156).

33 It is unknown how or by whom John was ‘swindled’ from such a large estate. His brother Edward died in 1864 (SMH 21 Jun 1864, p.9). Given Edward’s diverse business interests, it is possible he owned land in New Zealand and it may be that John had expectations of inheritance.

34 The Colonial Architect declined, however, to partition off one of three baths in the new bath house for the exclusive use of the Applewhaites, as it would substantially reduce the bathing facilities for the inmates (Hughes 2004:154).

35 Crook and Murray mis-speculated the letter referred to Stony Creek in Victoria. Hughes’ (2004:161) detailed investigation of Hicks’s private letters revealed the publication of the settlement at Ironbarks described in this letter.

36 An Alice Fry came to NSW as a bounty migrant in 1841 at the age of 28. She was listed as a cook who could read and write and a native of Liverpool. She was travelling with Ansom Fry, 24, a labourer native of County Cavan, Ireland. Both could read and write and both were Protestant. (SRNSW 4/4788 & 4/4863, Reels 2134, 1321, 07/08/1841 [NRS 5316, 5314]). This may be the same Alice Fry, future inmate of Hyde Park Asylum.