7

Femur

The femur (thigh bone) is the largest of the long bones. It is long relative to its diameter, with a fairly robust shaft.

Diagnostic features

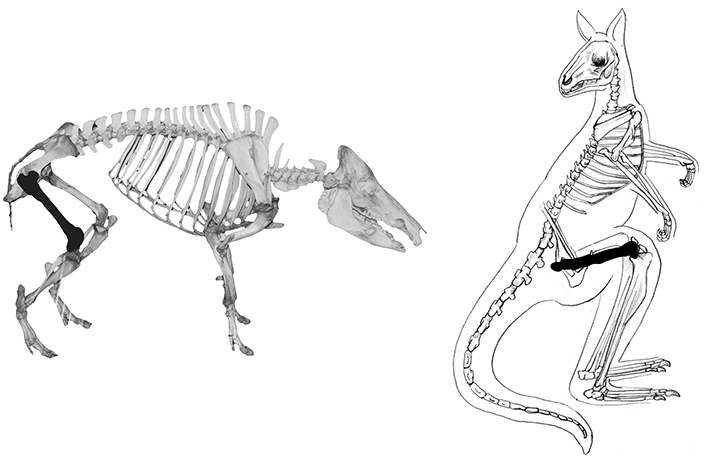

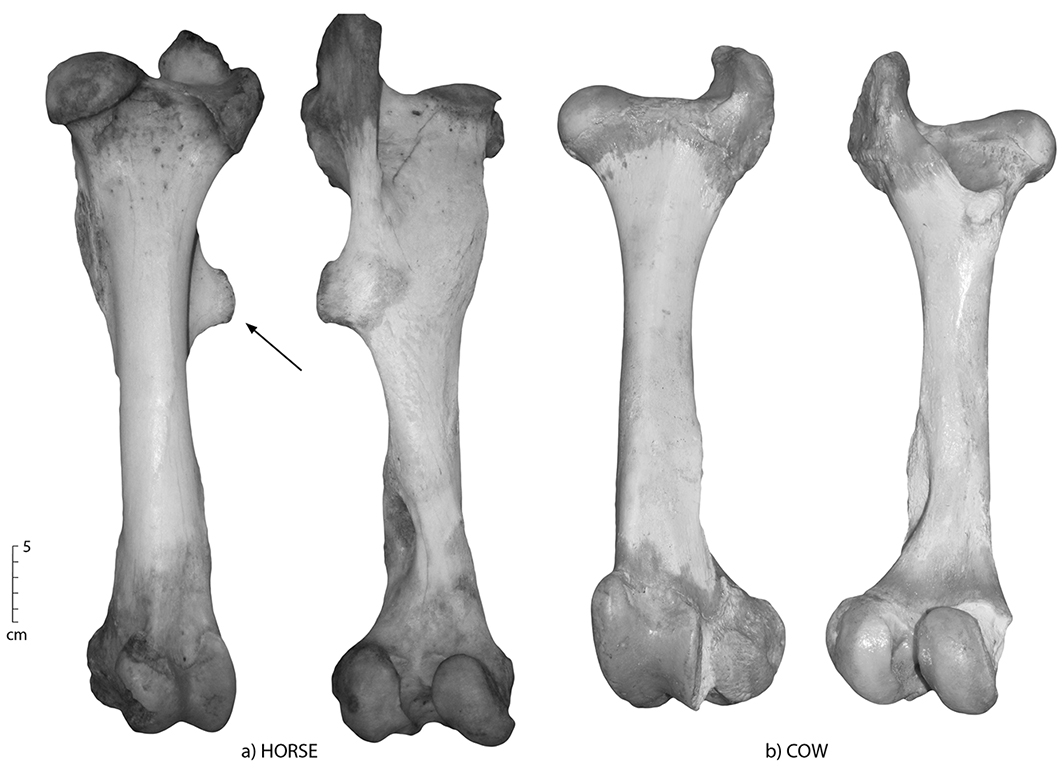

Diagnostic features of the femur are shown in Figures 7.1 and 7.2. The head (1) of the femur has a round, ball-like shape that articulates with the acetabulum of the pelvis proximally to form the hip joint. Distally, the medial (2) and lateral condyles (3) articulate with the tibia, and the patellar surface (4) articulates with the patella (knee cap), forming the knee joint. The curvature (or lack thereof) of the femoral shaft (5) can be used in species and element identification. The linea aspera (6), a prominent line that runs along the length of the shaft on the posterior side and branches as it nears the distal end, is also a diagnostic feature. At the proximal end, the greater trochanter (7) (most proximal), lesser trochanter (8) (medial), and in some species third trochanter (9) (lateral) is also useful for species identification. The trochanteric fossa (10) is a deep depression that lies just below the femoral head and neck (11) on the posterior side, and its depth is also useful in species identification.

A complete femur is frequently confused with a humerus, due to the similarity of their rounded proximal ends. The femoral head, however, is a complete ball, whereas the humeral head has only a rounded articular surface. To identify a femur based solely on a shaft fragment, consider that the femoral shaft is generally quite round in cross-section, whereas the cross-section of the humeral shaft is irregular, and that of the tibial shaft is triangular.

Orientation and siding

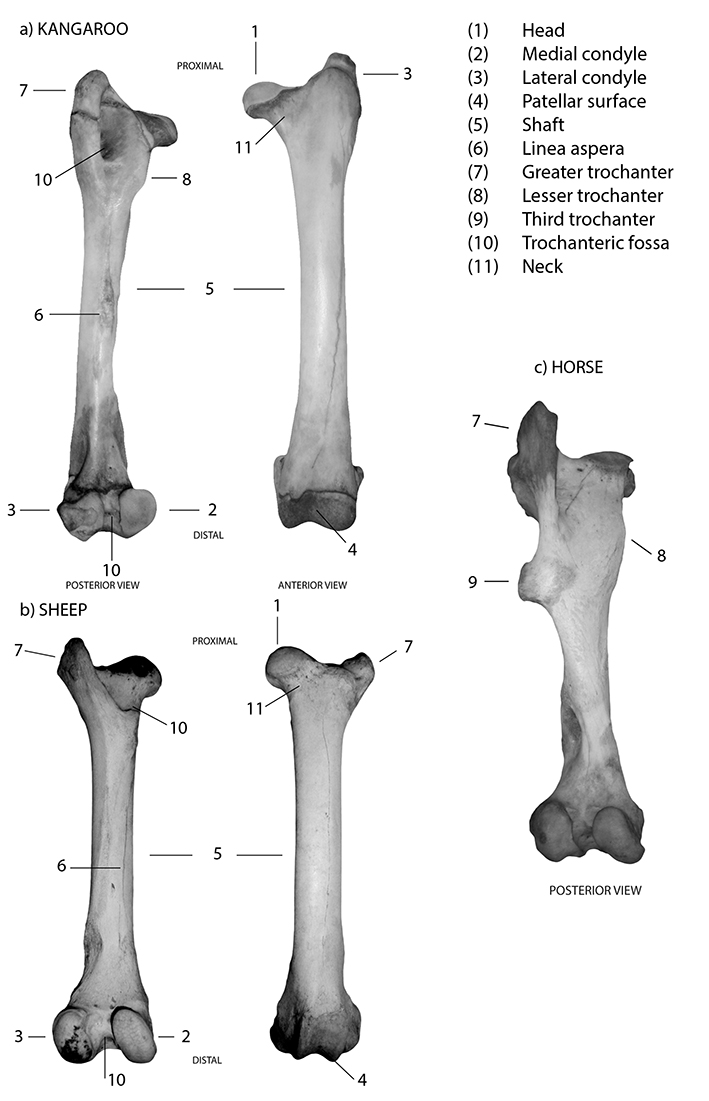

To side the femur, orient it by placing the head and neck proximally (up) and the condyles distally (down). The head is medial and the intertrochanteric fossa is posterior (anatomical position). If oriented using these criteria, the side from which the femur came should also be apparent, as the medial head will fit into the pelvis. If unclear, one trick that often works with complete femurs is to ‘stand’ them on their condyles on a flat surface (with the intertrochanteric fossa facing you). In quadrupeds (and most macropods), the femur will generally slant slightly away from the side from which it came. In humans the distal end will slant toward the side from which it came (due to the bicondylar angle, which facilitates bipedal locomotion).

Species identification

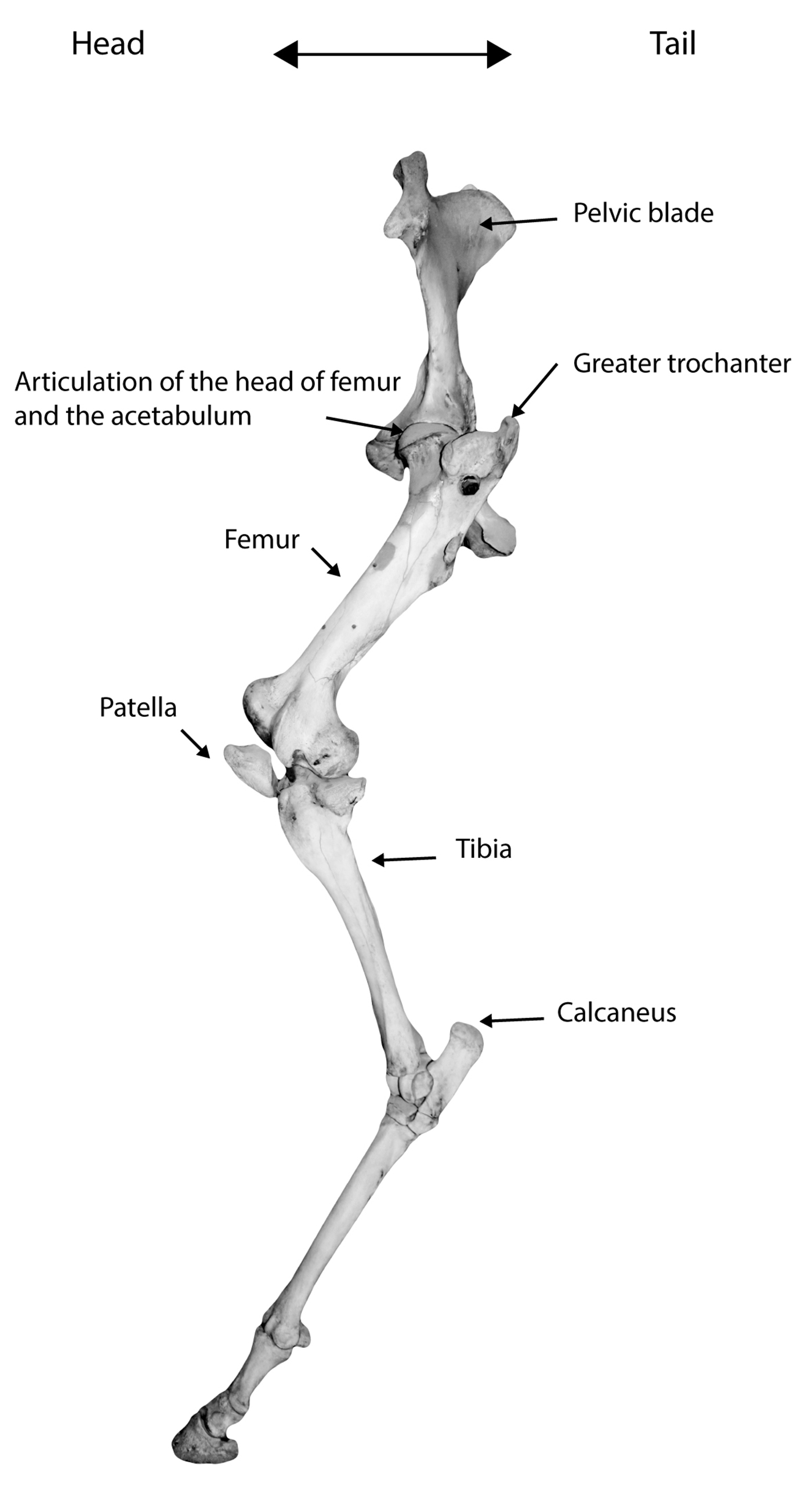

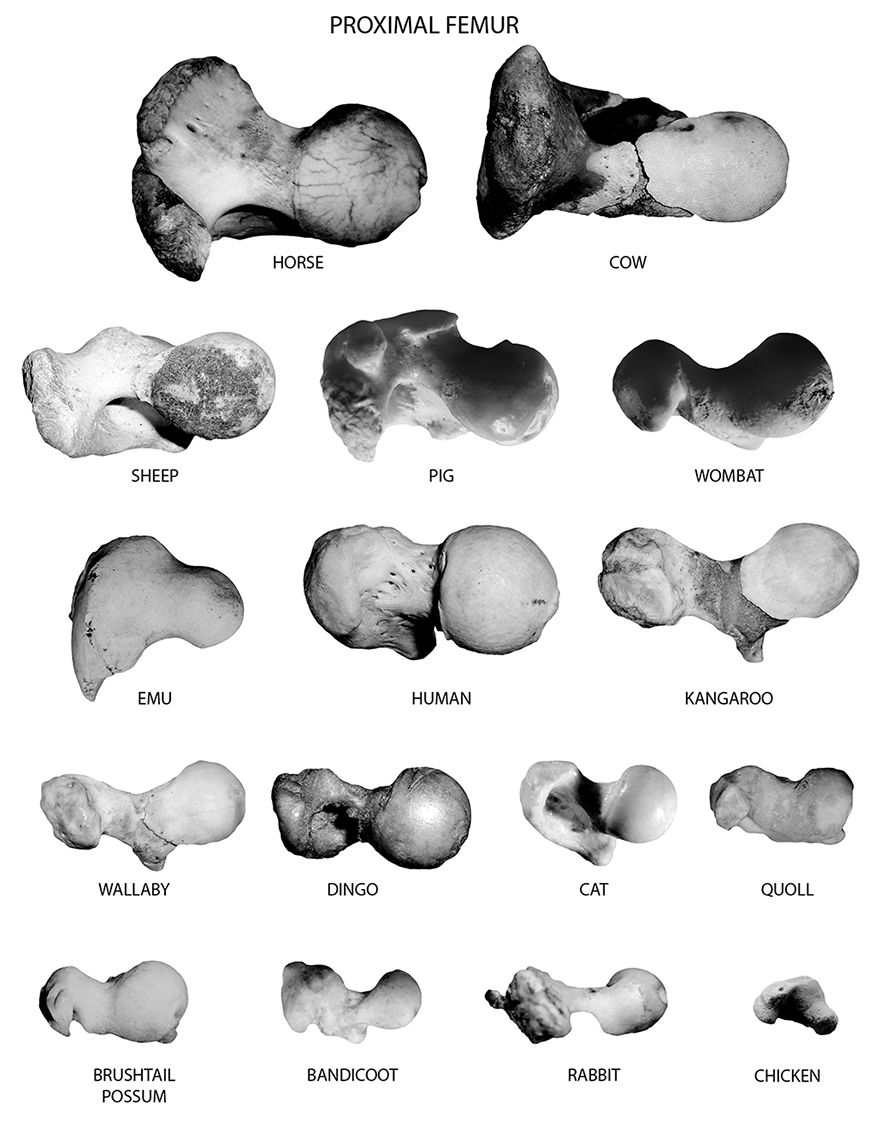

Refer to Figures 7.3–7.9 for species identification using the femur. If faced with a complete femur, identification to species is straightforward, and can be accomplished using a combination of the following morphological characteristics: a) size of the femoral neck, b) depth of the intertrochanteric fossa, c) height of the greater trochanter, d) size and position of the lesser trochanter, e) presence of a third trochanter, f) rugosity of the linea aspera, and g) general morphology of the distal articulation.

Figure 7.1: Femur with diagnostic features labelled; (a) kangaroo (b) sheep and (c) horse.

Figure 7.2: Horse hind limb (left, rear), illustrating joint articulation.

Inter-species distinctions

- Horses (Figure 7.3a) and rabbits have a third trochanter laterally.

- Marsupials and rabbits have well-developed lesser trochanters that give the proximal femur a fan-shaped appearance.

- The femoral shaft is straight in horses, cats, pigs, cattle, wombats and possums.

- The femoral shaft is curved convex anteriorly in rabbits, sheep, dingoes, wallabies, kangaroos and humans.

- Marsupials and horses have a long, 90-degree slit-shaped intertrochanteric fossa posteriorly.

- The lesser trochanter of marsupials begins as a rounded knob and terminates in a lipped trough.

- The lesser trochanter of horses is long and stretched in appearance.

- The lesser trochanter of wombats is triangular proximally when viewed from an anterior perspective; when viewed posteriorly, it appears as a distinctive knob that protrudes medially (Figure 7.4c).

- The femoral head has a triangular notch (fovea) in horses.

- Dingo and cat femurs are similar in form (but not in size) to human femurs, but can be distinguished from human femurs by their shorter necks.

Differentiating between humans and macropods

Large kangaroo femurs are frequently mistaken for human femurs. However, closer inspection of the proximal end reveals several key differences.

- In macropods the intertrochanteric fossa is deep, slit-like and angled at 90 degrees, while in humans it is shallow and angled (Figures 7.5b and c).

- In macropods, the knob-like lesser trochanter is followed distally by a lipped trough, whereas in humans there is no trough.

- Macropods have a greater trochanter that extends higher than the femoral head, whereas in humans the femoral head is higher and the greater trochanter is reduced.

- Medially, the human femoral shafts are slender with a long, thread-like, raised linea aspera.

- The linea aspera of kangaroos is very knobby and rugose and is found on the posterior mid-shaft.

- Distally, when viewed posteriorly, human femurs have a shallow patellar groove, whereas in kangaroos the patellar groove is quite deep.

Common state in archaeological assemblages

The femur is frequently encountered in many different types of faunal assemblages across time and space. Its high economic utility as a prime meat-bearing bone in food species is one contributing factor in its frequency (and popularity). Another factor leading to its increased survivability is the femur’s general robustness and density compared with other bones of the body. The femur is often found complete or as shaft fragments. Cut marks are frequently found on the femoral head and neck, resulting from the disarticulation of the leg from the pelvis (hip joint). Similarly, cut marks may be visible on the distal condyles resulting from the disarticulation from the lower leg at the knee joint. When fragmented in historical assemblages, femoral shafts often bear cut marks from butcher’s band saws. In prehistoric assemblages, the shaft may be smashed and broken open for marrow extraction. In the presence of carnivores, the femoral head is often missing (having been chewed), and the distal condyles are frequently gnawed.

Figure 7.3: Anterior and posterior views of the femur; (a) horse and (b) cow. The third trochanter is visible on the horse (arrowed).

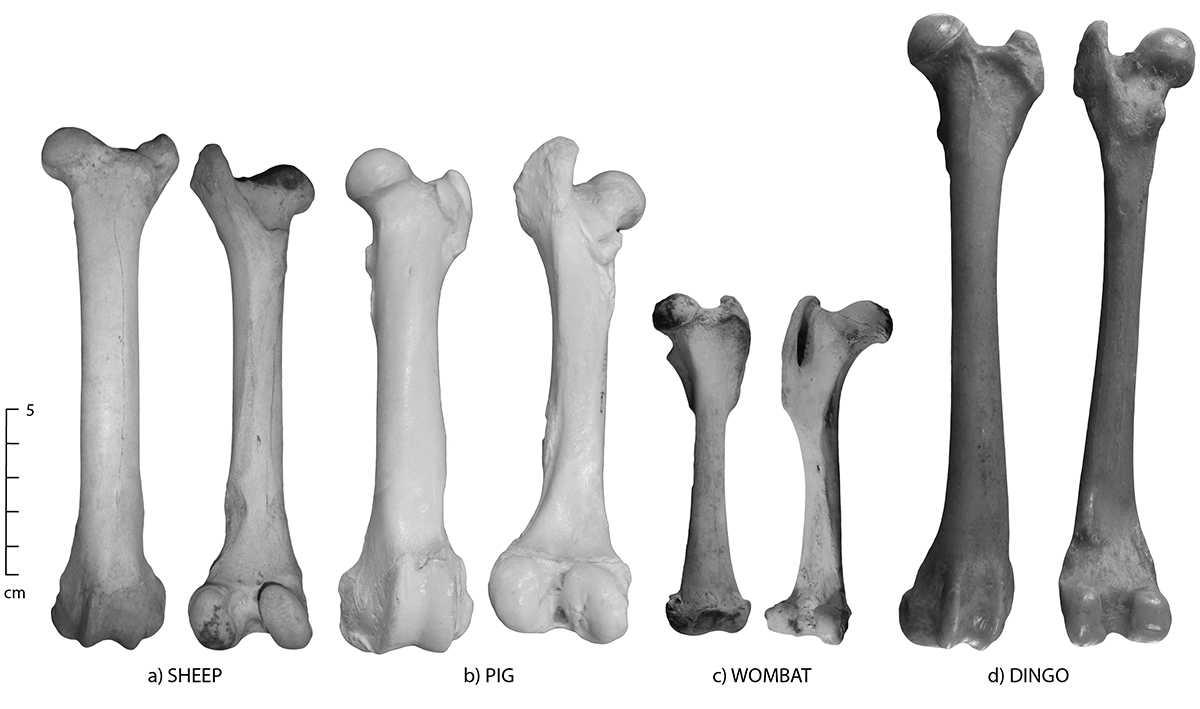

Figure 7.4: Anterior and posterior views of the femur; (a) sheep, (b) pig, and (c) wombat and (d) dingo.

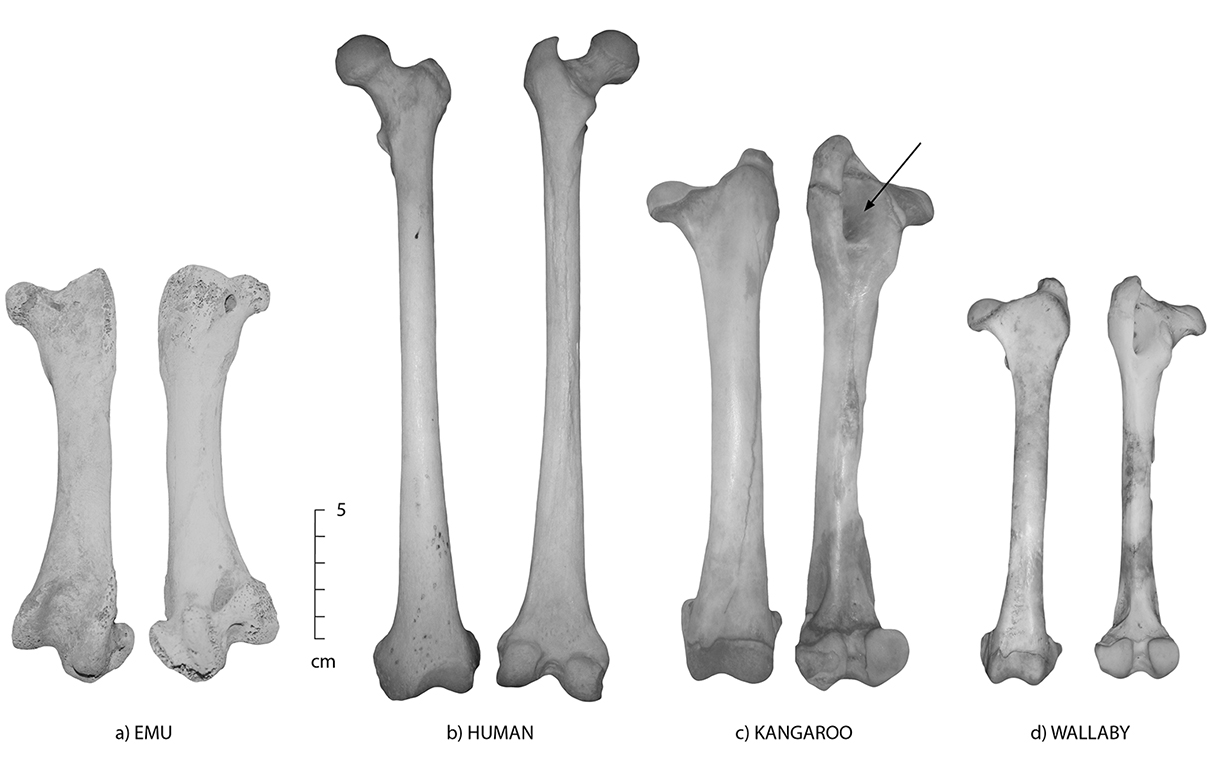

Figure 7.5: Anterior and posterior views of the femur; (a) emu, (b) human, (c) kangaroo and (d) wallaby. Note the ‘slit’ on posterior kangaroo femur, arrowed.

Figure 7.6: Anterior and posterior views of the femur; (a) cat , (b) chicken, (c) quoll and (d) rabbit.

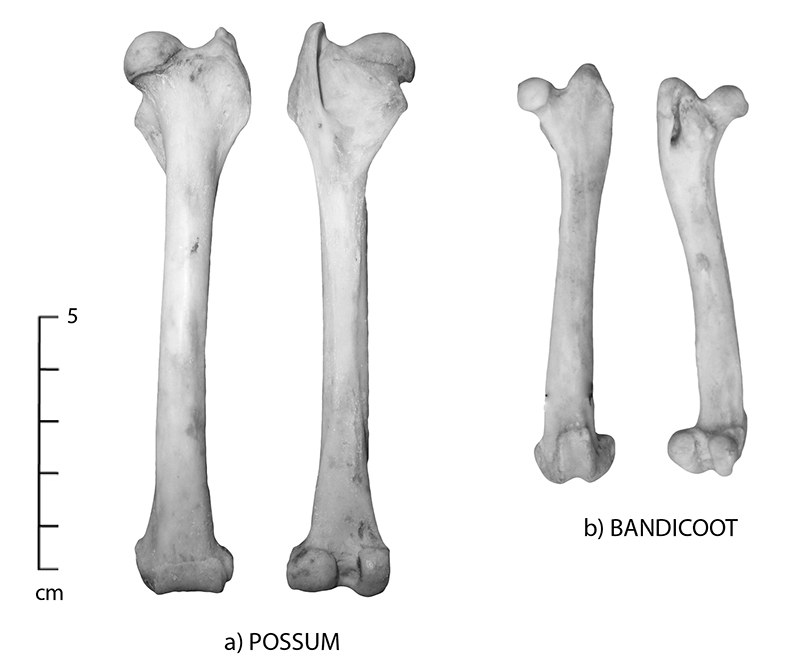

Figure 7.7: Anterior and posterior views of the femur; (a) brushtail possum and (b) bandicoot.

Figure 7.8: Proximal femur for all species (in order of decreasing size). Smaller species are exaggerated in size to show detail.

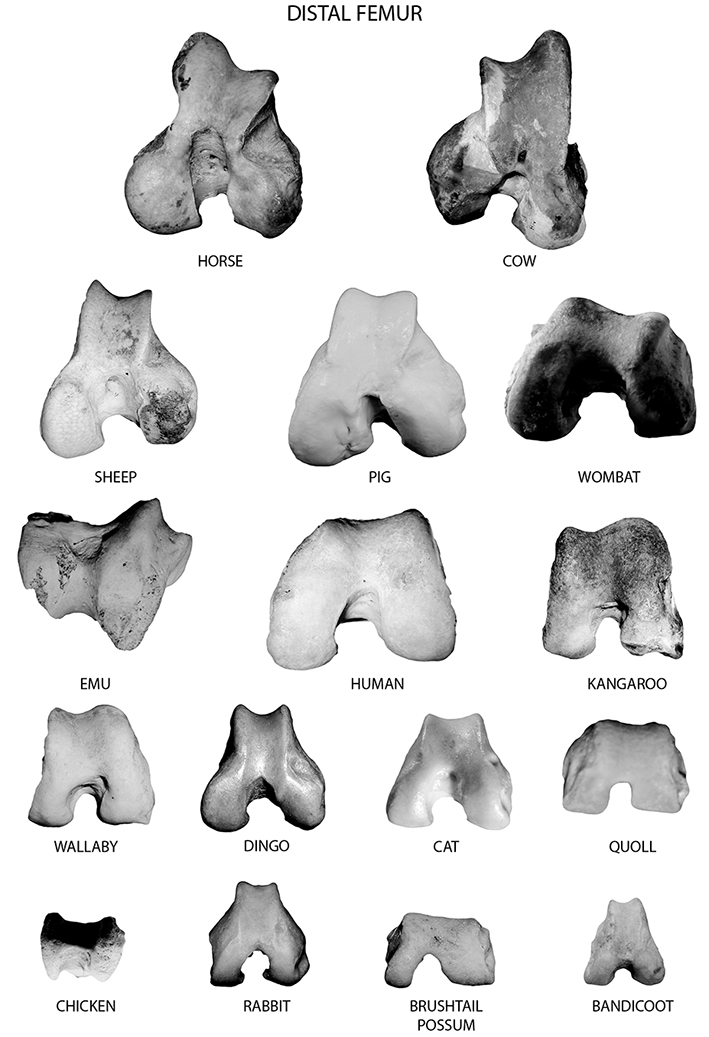

Figure 7.9: Distal femur for all species (in order of decreasing size). Smaller species are exaggerated in size to show detail.

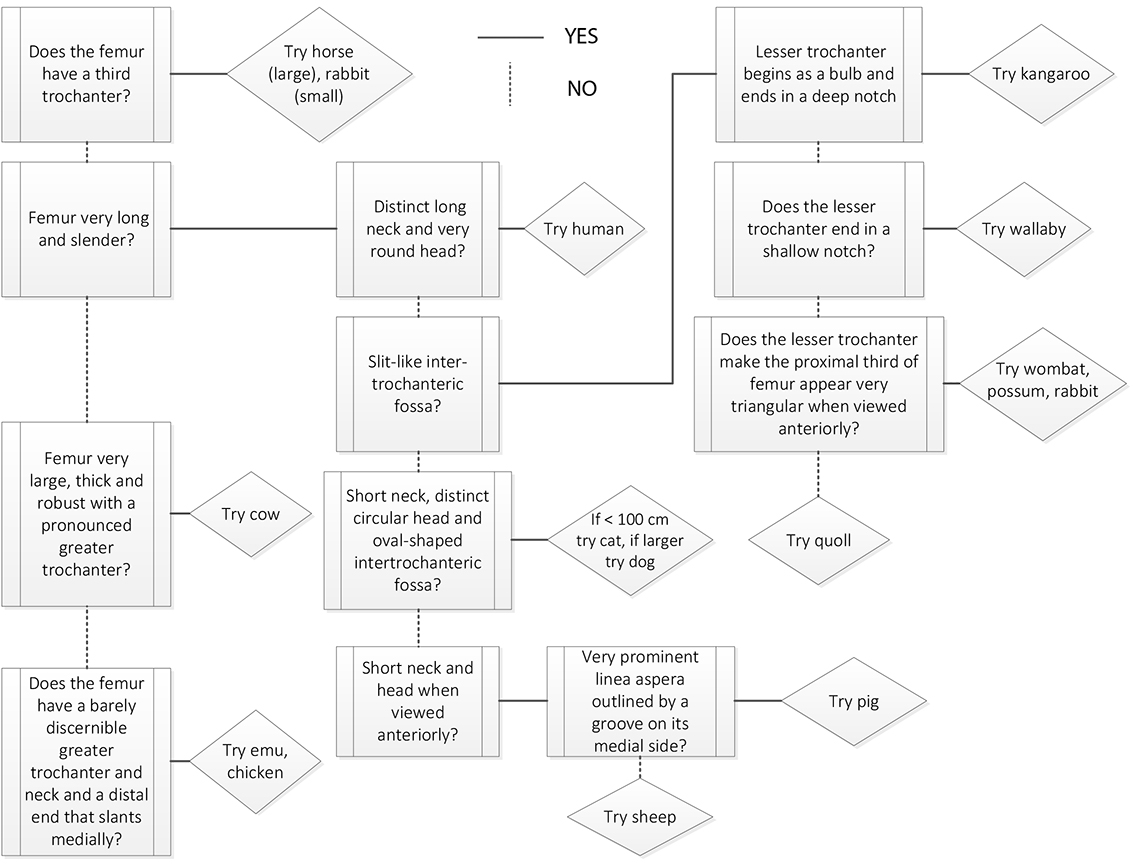

Figure 7.10: Femur decision process. |