3

Humerus

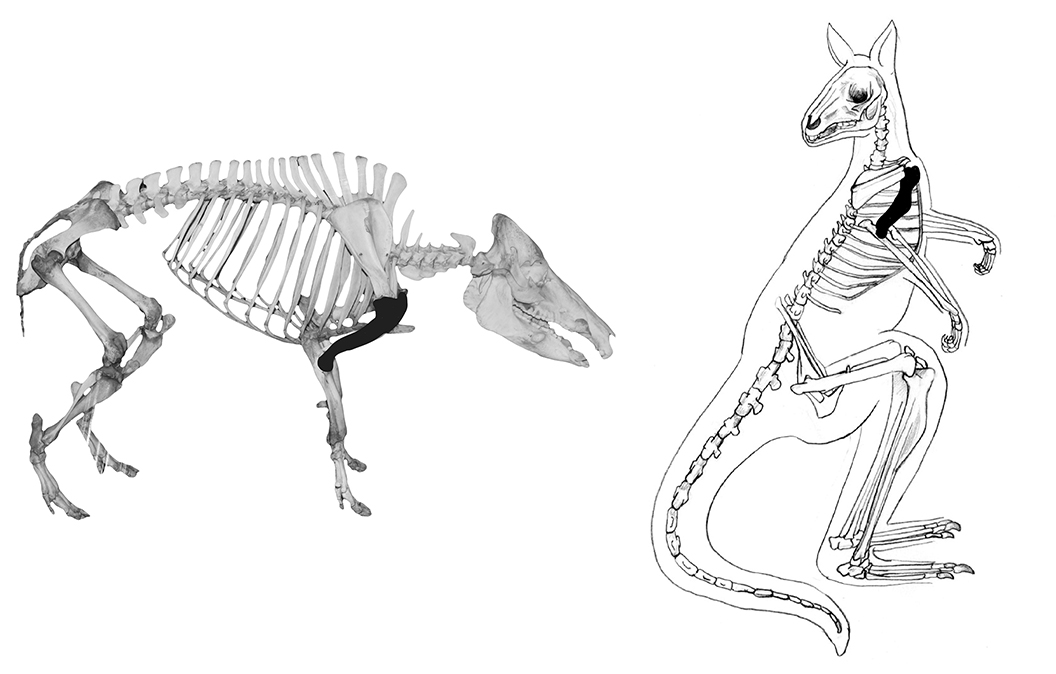

The humerus, or upper arm/fore leg bone, is commonly recovered in archaeological contexts. While it is often fragmented, the distal end which forms the elbow joint often remains intact, and is very useful in making positive species identifications.

Diagnostic features

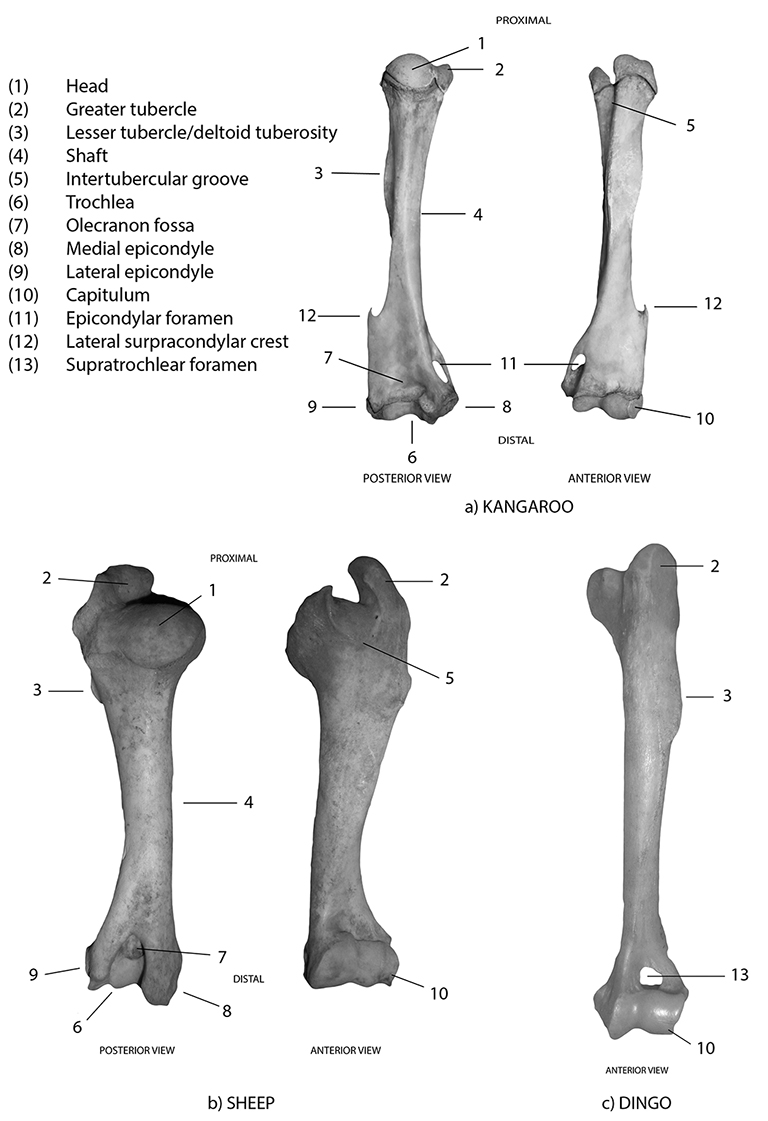

Diagnostic features of the humerus are shown in Figure 3.1. The humerus is the largest bone in the upper arm. It is a long bone distinguished by a rounded proximal end, the head (1), which articulates with the glenoid fossa of the scapula to form the shoulder joint. While all species have a rounded humeral head, the diagnostic features around the head vary considerably, largely due to differences in locomotion. For example, the greater tubercle (2), to which are attached the supra- and infra-spinatus muscles, is very large and pronounced in most quadrupeds. The lesser tubercle/deltoid tuberosity (3), which lies on the lateral upper humeral shaft (4) and is an attachment point for the subscapularis muscle, is also more pronounced in quadrupeds, as is the bicipital/intertubercular groove (5), which lies between the two and serves as an attachment point for the biceps muscle. The spool-shaped distal end, the trochlea (6), is an articular surface that has a pronounced notch on its posterior side, the olecranon fossa (7), for articulation with the ulna. The olecranon fossa divides the distal humerus into medial (8) and lateral (9) epicondylar areas. The capitulum (10) is a further articular surface on the distal end, located on the lateral side, where the radius joins the humerus.

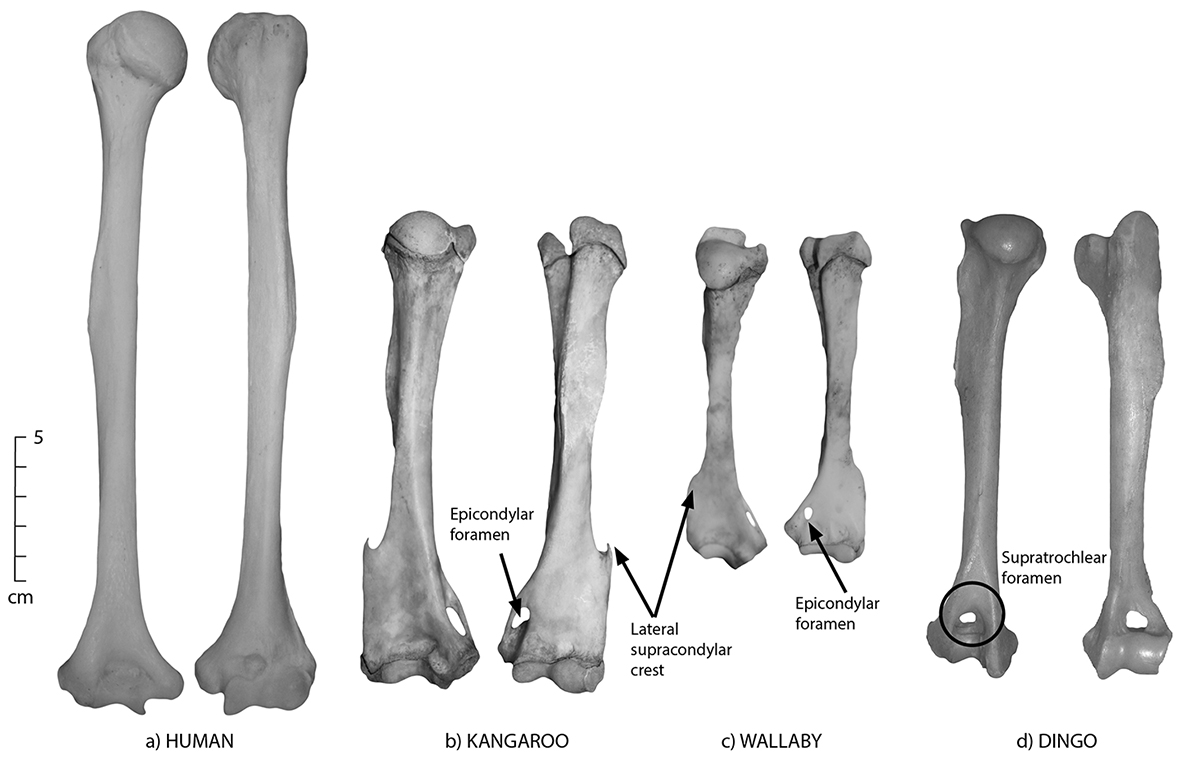

Macropods have two additional features that can often be used to help distinguish their bones. On the medial distal end, there is an epicondylar foramen (11), which is also found in felines, while on the distal lateral shaft, there is a pointed projection, called the lateral supracondylar or supinator crest (12). Several species also have a hole just above the trochlea, called a supratrochlear foramen (13). The humerus, radius and ulna form the elbow joint. The humerus is a highly diagnostic bone for species identification. If fragmentary, the humerus can still be distinguished from the femur, the element for which it is most commonly mistaken, by the following morphological characteristics:

- The head of the humerus is smooth and does not have a small hole in it (fovea capitum), unlike the head of the femur.

- The shaft of the humerus is ‘twisted’ as opposed to straight in nearly all animals (except humans).

- There is a nutrient foramen (small hole) on the shaft of the humerus, which points downward; it can be useful in distinguishing the humerus from other long bones.

Orientation and siding

In all species, the rounded head points cranially (toward the head), and the spool-shaped distal articulation points toward the feet. To side the humerus, hold it in anatomical position and orient the head so that it is medial/slightly posterior and the greater trochanter is anterior/slightly lateral – the olecranon fossa should be posterior. The lesser tubercle/deltoid tuberosity (if visible) will be lateral.

Figure 3.1: Humeri with diagnostic features labelled; a) kangaroo, b) sheep and c) dingo.

Species identification

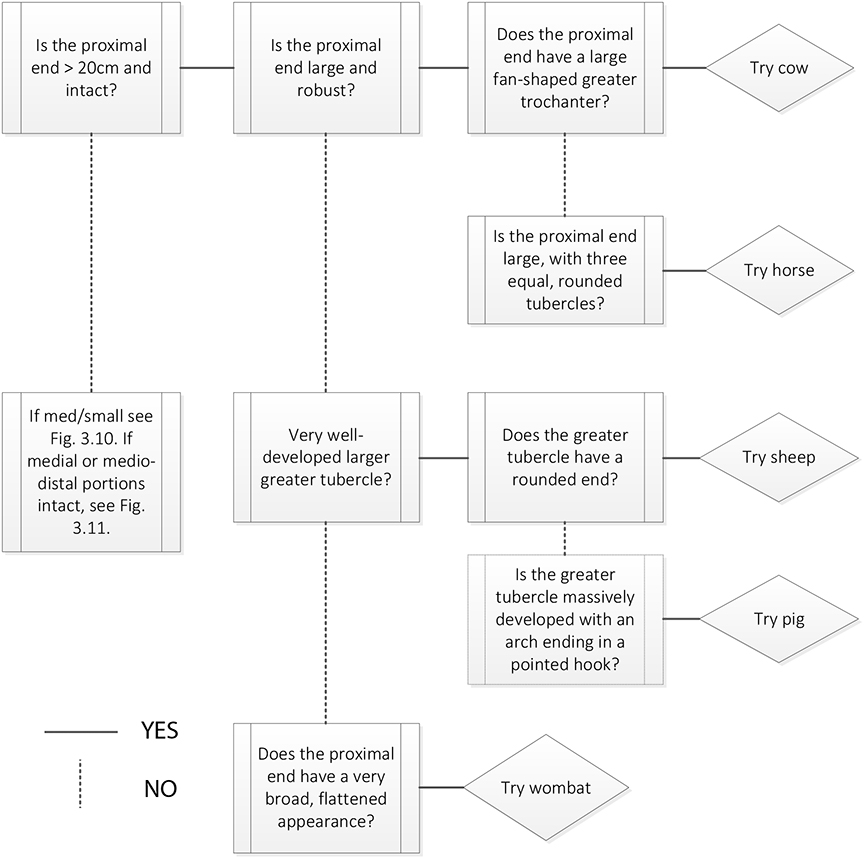

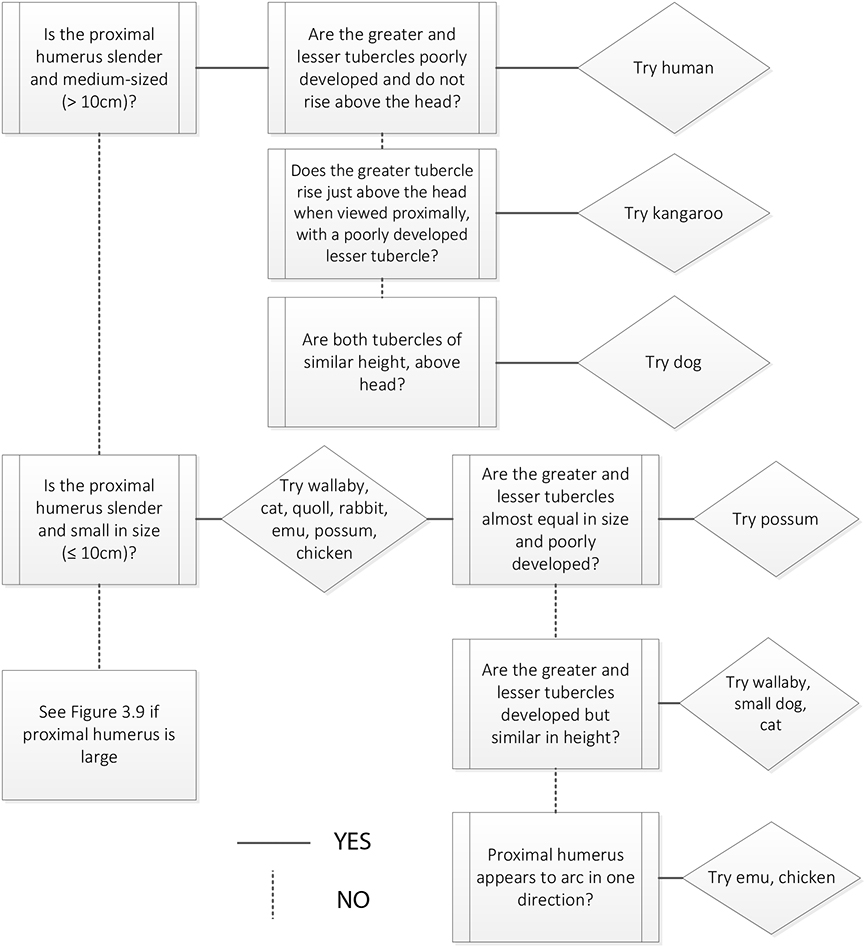

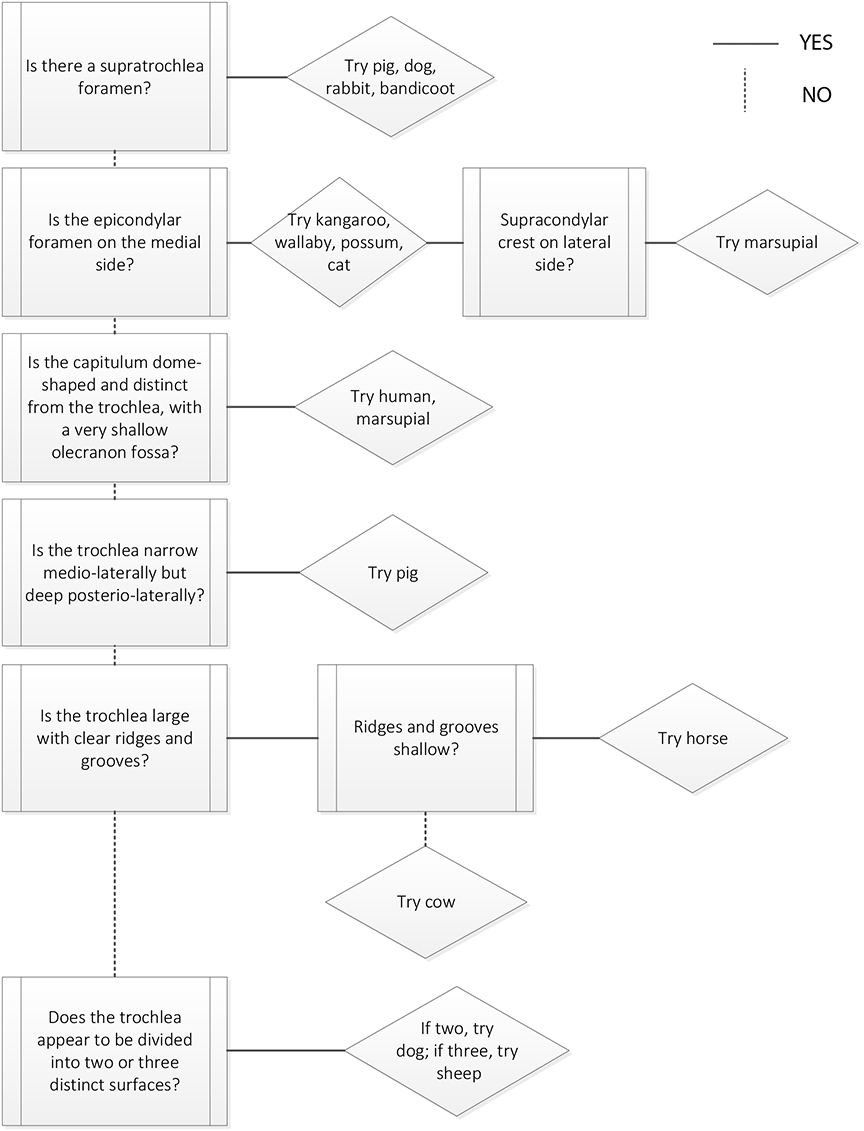

Refer to Figures 3.2–3.8 for species identification using the humerus.

If the humerus is complete, use the head and size of the greater tubercle on the proximal end, and the presence/absence of any of the following distinctive features on the distal end: supratrochlear foramen, supinator crest, epicondylar foramen, size of the lateral/medial epicondyles.

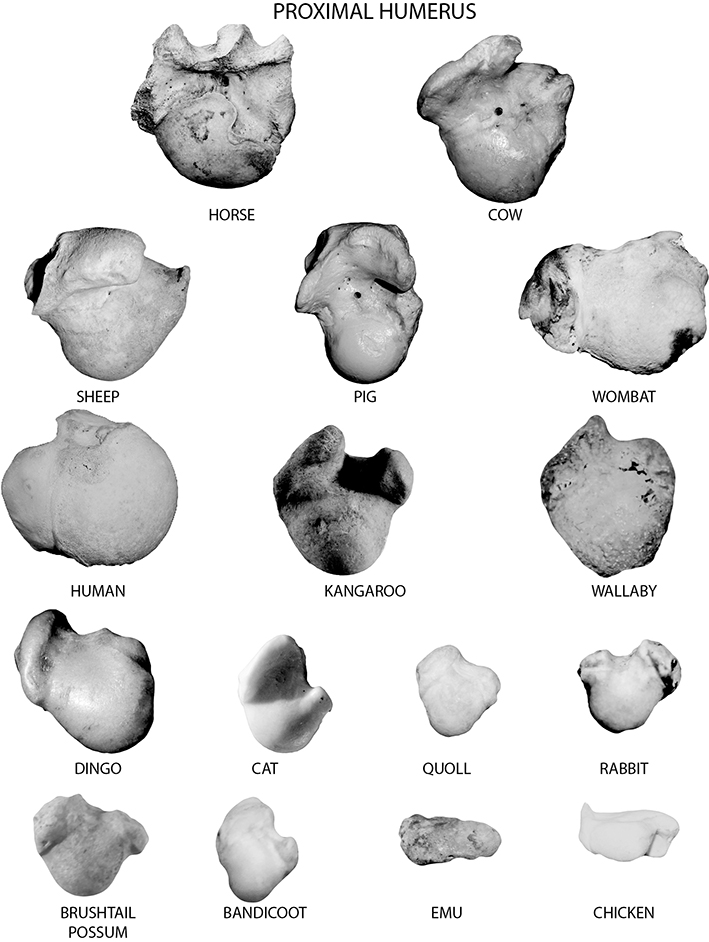

If just the proximal end of the humerus is extant, use the head and size of the greater tubercle for identification (see Figures 3.1 and 3.9).

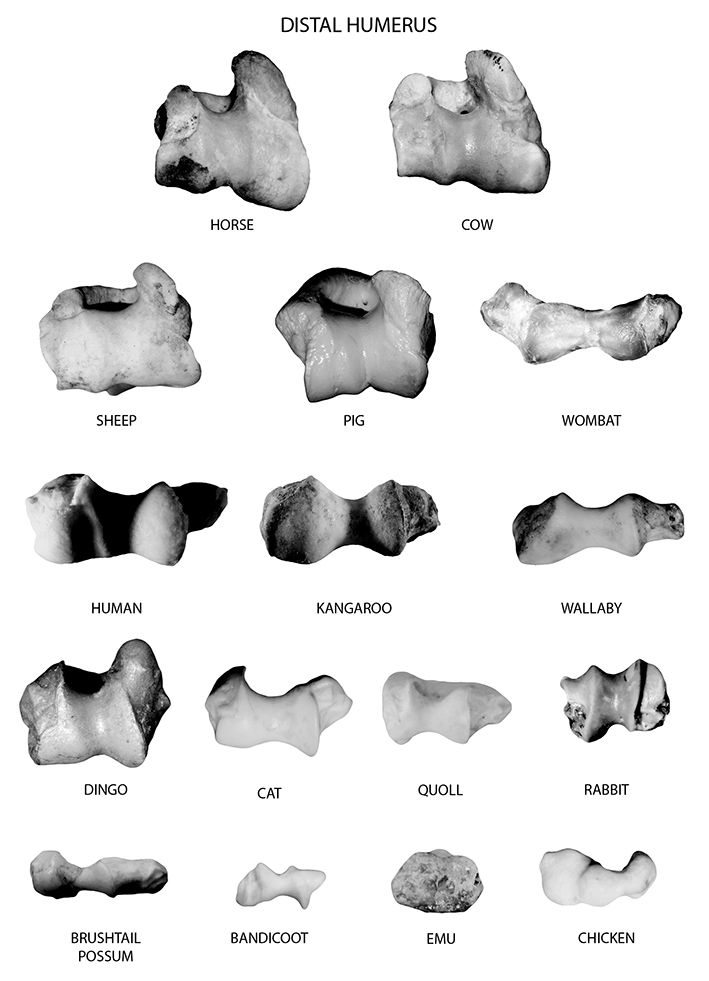

If just the distal end of the humerus is extant, use the presence/absence of any of the distinctive features on the distal end: supratrochlear foramen, supinator crest, epicondylar foramen, size of the lateral/medial epicondyles (see Figures 3.1 and 3.11).

If all that survives of the humerus is the medial shaft, it is likely that identification of the element will be difficult enough. If you are able to identify the shaft fragment as a humerus, then the morphology of the humeral shaft may be used to narrow down the range of possible animals, as it varies by species. The following generalisations use a combination of the cross-sectional morphology and location/size of the deltoid tuberosity as clues to identification, and are divided by size of species (i.e. large, medium and small). However, species identification must be finalised by comparison with a physical reference collection.

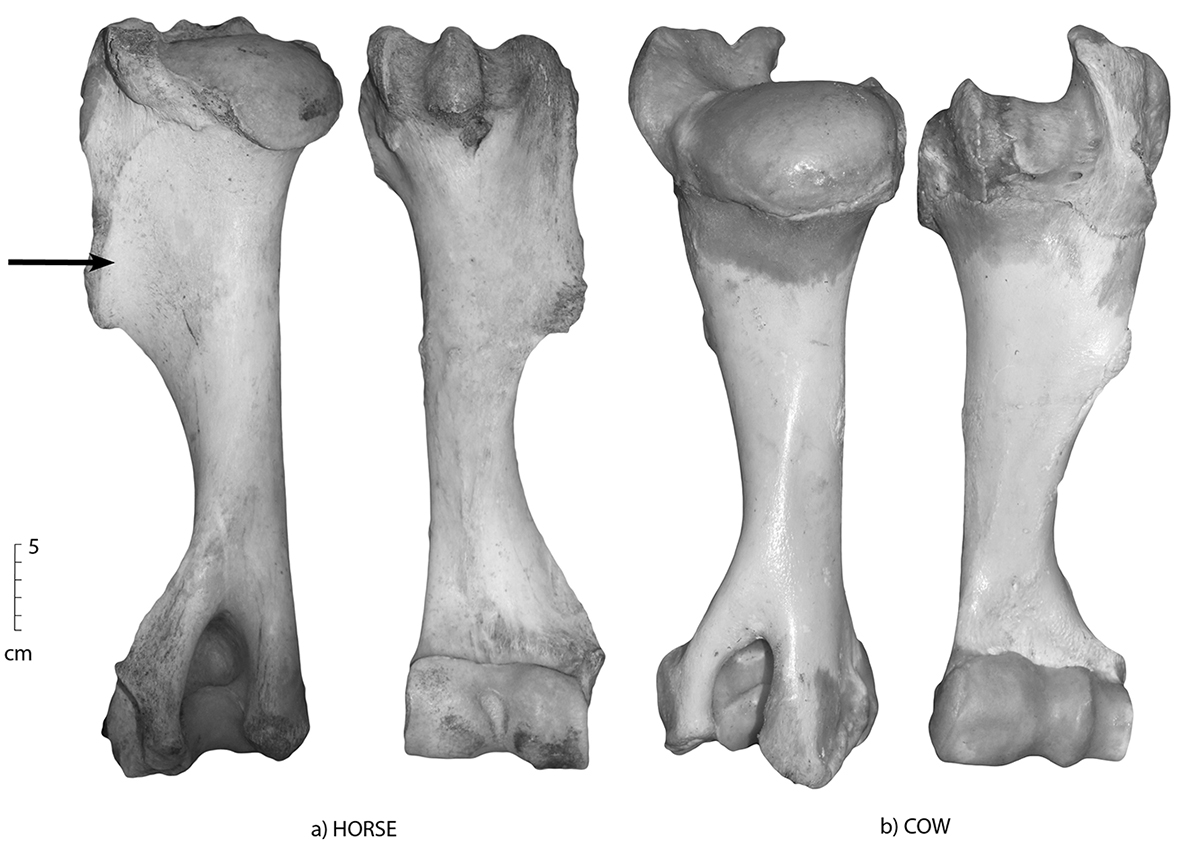

Large animals

- Cows and horses have a round- to oval-shaped humerus shaft cross-section that is variable along the length of the shaft.

- Horses have a very prominent deltoid tuberosity that is located on the upper third of the proximal shaft (Figure 3.2a).

- Cows have a deltoid tuberosity that is moderately prominent and located on the upper third of the proximal shaft (Figure 3.2b).

Medium animals

- Humans have a square-shaped humerus shaft cross-section that is uniform in size along the length of the shaft.

- Large dogs, sheep, pigs and kangaroos have an oval cross-section that varies along the length of the shaft.

- Wombats have a cross-section that is twisted and irregularly shaped, with a very prominent deltoid tuberosity located on the mid-shaft (Figure 3.3c).

- In humans the deltoid tuberosity is only visible as a slight roughening or swelling on the proximal half of the shaft.

- Dingoes and kangaroos have a deltoid tuberosity marked by a slight ridge on the upper shaft.

Small animals

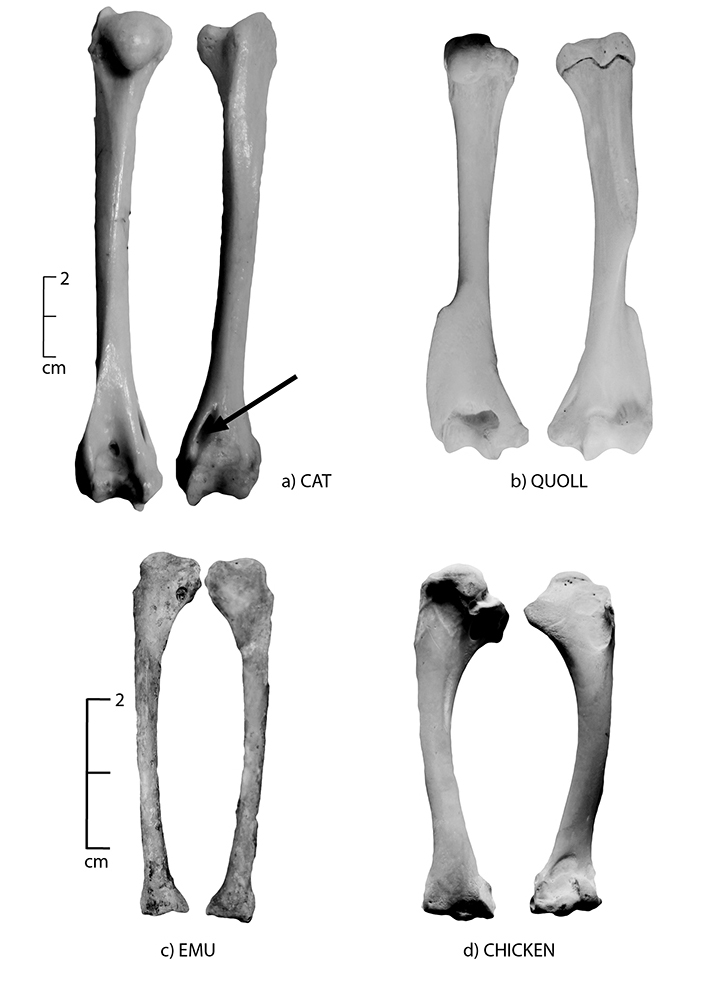

- In cats and rabbits the humerus shaft cross-section is very round in shape and fairly uniform along the length of shaft.

- In possums and chickens, the cross-section shape is oval and varies in size along the length of shaft.

- Both rabbits and chickens have no marked deltoid tuberosities (Figures 3.6a and 3.4d).

- Wallabies have deltoid tuberosities that are small and slightly raised.

- Possums have a prominent, pointed deltoid tuberosity just above the mid-shaft.

As in all elements, general size and robustness of the humerus are good measures to differentiate between species. Of the species included in this manual, horse and cow are the largest and most robust, while emu, kangaroo and wallaby are the slightest; smallest are cat, possum, rabbit, chicken and emu. When following the decision processes, always use size as a final determining factor in species identification.

Distinguishing between humans and animals

- In humans, the humerus is long, slender and fairly uniform in shape and size along its shaft.

- In quadrupeds, the humerus is robust, stout and has a variable shaft cross-section morphology (narrowest at the mid-shaft and becoming slightly wider at both ends).

- In quadrupeds, the greater tubercle is generally well developed, while in humans it is less developed and difficult to see.

- In humans and marsupials, the medial epicondyle is pronounced, while in introduced quadrupeds it is generally larger.

Macropods can be identified by the presence of both a supracondylar/supinator crest on the lateral side of the medio-distal humerus and an epicondylar foramen on the medial side. Most carnivores (dogs, pigs), and often rabbits, have a supratrochlear foramen.

Distinguishing between dogs and cats

- Cats have a epicondylar foramen and no supratrochlear foramen (Figure 3.4a).

- Dogs have a supratrochlear foramen and no epicondylar foramen (Figure 3.5d).

Distinguishing between marsupials

- Kangaroos, wallabies, (Figures 3.5b and c) and possums (Figure 3.6b) all have nutrient foramina on the anterior surface of the medio-distal shaft, while in wombats the nutrient foramen is located proximal-medially on the posterior surface of the shaft.

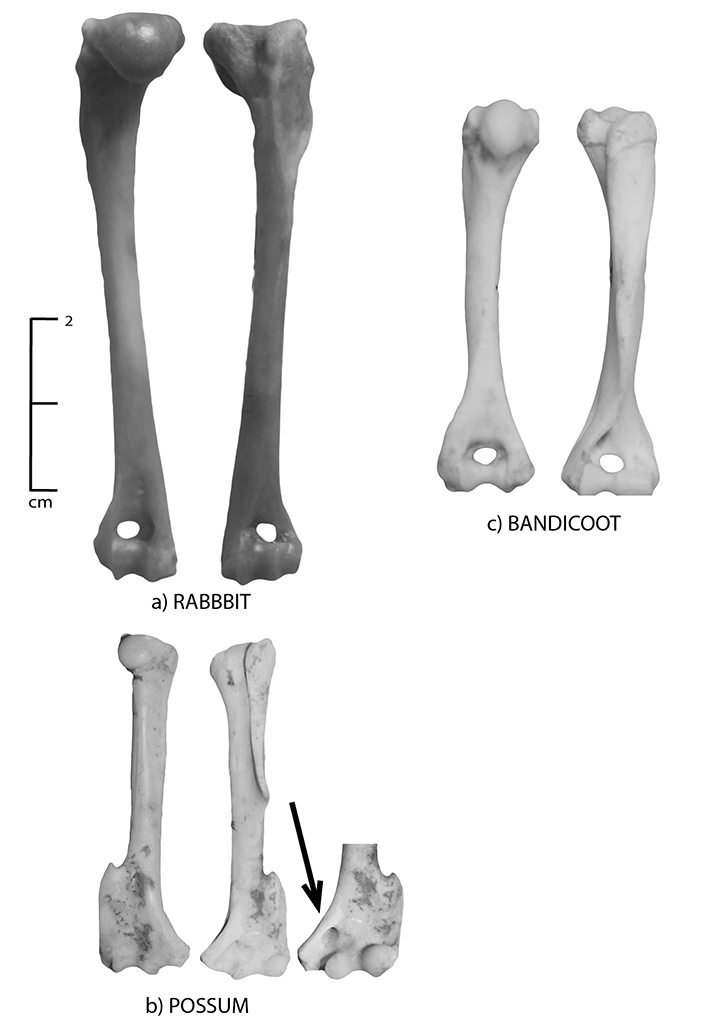

- Kangaroos, wallabies and possums all have very similar humerus morphology, so use size as an initial criterion to differentiate between them (Figures 3.7 and 3.8).

- To differentiate kangaroos from wallabies: the proximal epiphysis is the same shape in both; the only difference is size (e.g. in an average grey kangaroo, the proximal epiphysis is twice the size than that of a Bennet’s wallaby).

- To differentiate wallabies from possums (both similar in size): the wallaby has a well-developed, larger trochanter than the possum. The possum has a well-developed deltoid tuberosity, while in the wallaby it is not well developed.

- The wombat humerus has a rather broad proximal end with a deep bicipital groove anteriorly and poorly developed greater and lesser trochanters.

Figure 3.2: Posterior and anterior views of the humerus; (a) horse and (b) cow. The deltoid tuberosity is most prominent on the horse (arrowed), and is also present on the cow, though not as prominent and located on the upper third of the proximal shaft.

Figure 3.3: Posterior and anterior views of the humerus; (a) sheep, (b) pig and (c) wombat.

Figure 3.4: Posterior and anterior views of the humerus; (a) cat, (b) quoll, (c) emu and (d) chicken. The chicken and emu have no marked deltoid tuberosity, while cats have an epicondylar foramen (arrowed).

Figure 3.5: Posterior and anterior views of the humerus; (a) human, (b) kangaroo, (c) wallaby and (d) dingo. Dingoes have a supratrochlear foramen (circled). These views have been angled slightly to illustrate the lateral supracondylar crest and the epicondylar foramen.

Figure 3.6: Posterior and anterior views of the humerus; (a) rabbit, (b) brushtail possum and (c) bandicoot. Note the nutrient foramen on the brushtail possum; an extra view is provided to show its location (arrow).

Figure 3.7: Proximal humerus of all species (in order of decreasing size). Those of smaller species are shown at an exaggerated size to show details.

Figure 3.8: Distal humerus of all species (in order of decreasing size). Those of smaller species are shown at an exaggerated size to show details.

Common state in archaeological assemblages

The distal humerus of many quadrupeds is a delicacy for carnivores who love to chew, and is therefore commonly missing from many historic assemblages. The proximal and medial humerus often fare better, and are frequently intact in older animals. However, many species (especially sheep, goats, pigs and cattle) are slaughtered at an age before the proximal and distal epiphyses fuse, and these are therefore commonly missing in assemblages where these animals were slaughtered at a younger age. The humeri of macropods and emus are rather small, compared to the other skeletal elements, and are also frequently absent from archaeological assemblages. The humerus is a bone that frequently bears traces of butchery on quadrupedal animals, especially in assemblages that date after the introduction of the band saw. Marks from butchery are commonly found just above the distal articulation with the radius/ulna to form a shoulder/forequarter meat cut. The humeral mid-shaft is also commonly found in many archaeological assemblages and its cross-sectional morphology can be used as an indicator of species.

Figure 3.9: Humerus decision process 1. Use this decision process to identify species when the proximal end of the humerus is extant and large. |

Figure 3.10: Humerus decision process 2. Use this decision process to identify species when the proximal end of the humerus is extant and medium or small. |

|