4

Radius

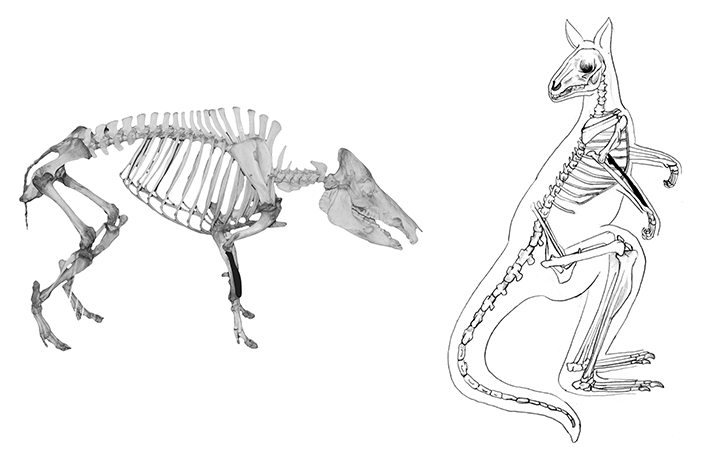

The radius is the larger of two paired bones that make up the fore limb (the other being the ulna). In bipeds (humans and many macropods), the radius moves over the ulna. This motion is reflected in the rounded proximal head that is generally characteristic of bipeds. Other species, particularly large ungulates (hoofed animals) like cows, horses, sheep and deer do not have a rotating radius, which often fuses with the ulna in adulthood. This results in a large ‘oversized’ radius, and an ulna that is greatly reduced in size. For this reason, some images found on the following pages will depict a fused radius/ulna. It is also important to note that in species with a fused radius/ulna, the two bones are generally separate in immature animals. In all of the other species presented in this manual, the two bones remain separate throughout life.

Diagnostic features

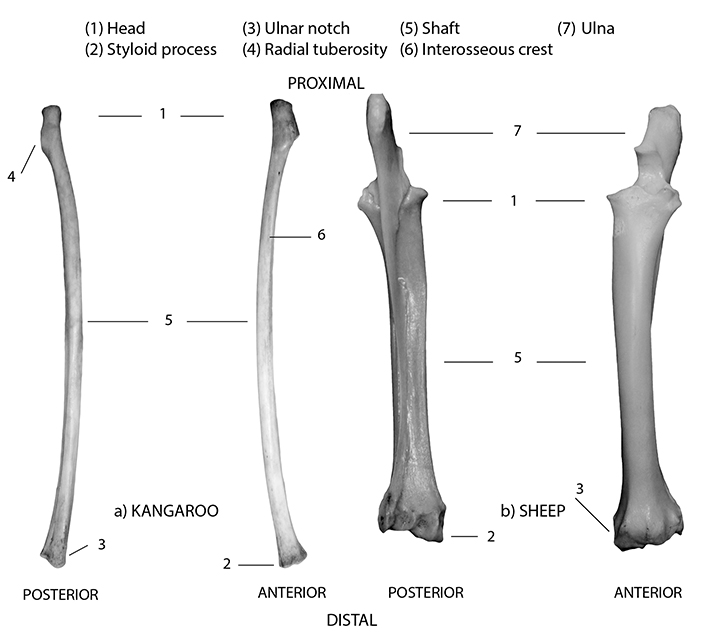

Diagnostic features of the radius are shown in Figure 4.1. The radial head (1) varies morphologically by species. In humans, macropods and carnivores, it is a ‘swollen’ articular area that articulates proximally with the capitulum of the distal humerus and trochlear notch of the ulna. In species with a separate radius and ulna, there is an articular facet on the radial head for articulation with the ulna. In species in which the radius and ulna are fused, the bone tends to be ‘flattened’ anterio-posteriorly (front to back) and convex anteriorly, with a wide proximal end onto which fits the ulna. Distally, the radius articulates with the ulna and carpals (depending on the species), and is distinguished by a styloid process (2) on the lateral side and an ulnar notch (3) on the medial side (in most species, except horse). The radius can be further distinguished by the radial tuberosity (4), located on the medial proximal shaft just below the head. The radial shaft (5) may also have a sharp interosseous crest (6) on its medial side.

Orientation and siding

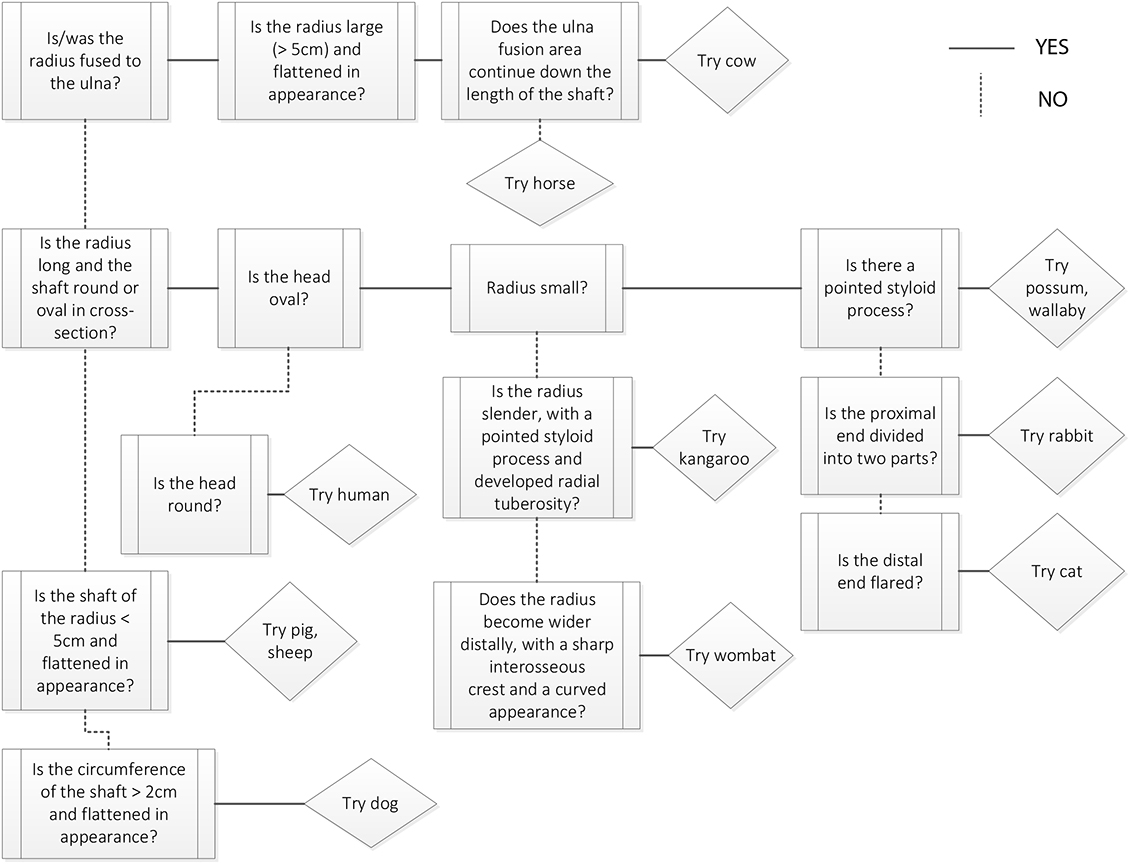

Refer to Figure 4.1 for orientation and siding, and for species identification use the Radius decision process (Figure 4.9). To side the radius, place the head proximally (up), with the radial tuberosity anterior (front) and medial. The shaft is generally concave on the anterior side. The styloid process should be on the lateral side of the distal end, while the ulnar notch will be on the medial side of the distal end (in species with unfused radii). In some species, the medial edge of the radius (interosseous crest) is sharp. If siding a human, remember to side the radius, when in anatomical position, with palms facing up (imagine Da Vinci’s famous man).

Figure 4.1: Radii with diagnostic features labelled; (a) kangaroo radius and (b) sheep fused radius/ulna.

Species identification

Refer to Figures 4.2–4.8 for species identification using the radius.

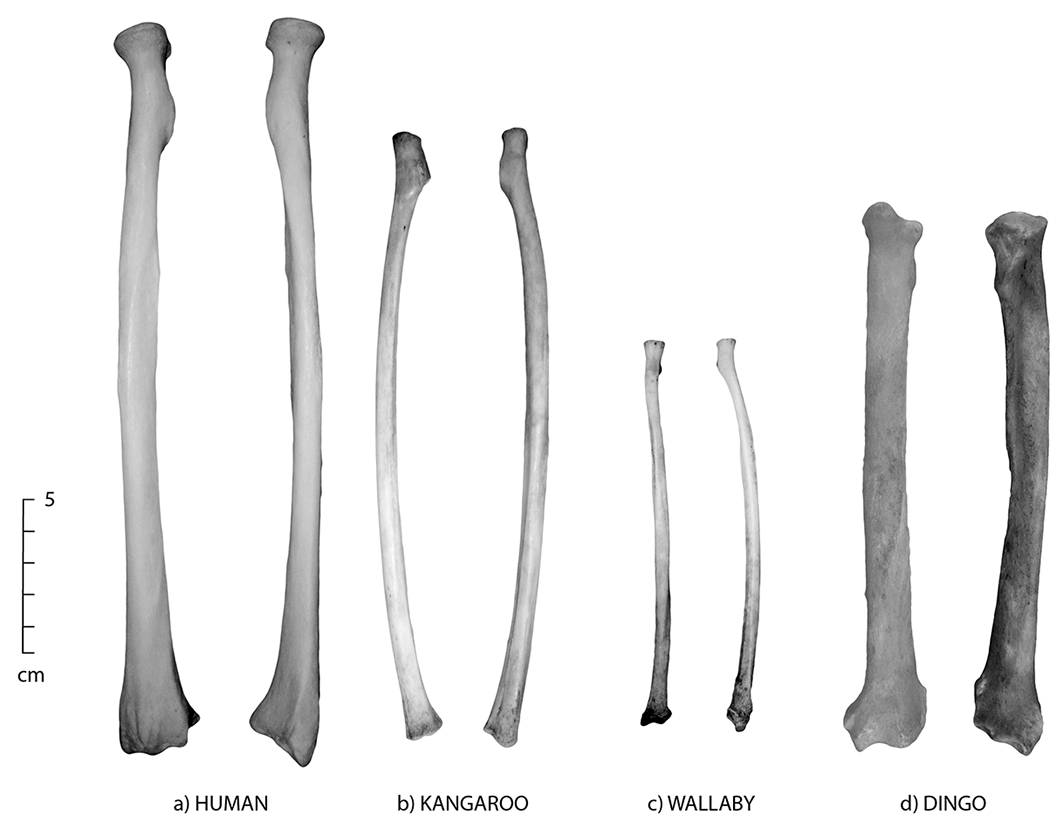

Humans, kangaroos, wallabies, cats, rabbits and possums have a long and slender radius with a rounded proximal end, and a round to oval cross-section. The radii of dingoes and cats are also long and slender, but have a D-shaped cross-section.

Distinguishing between human and kangaroo

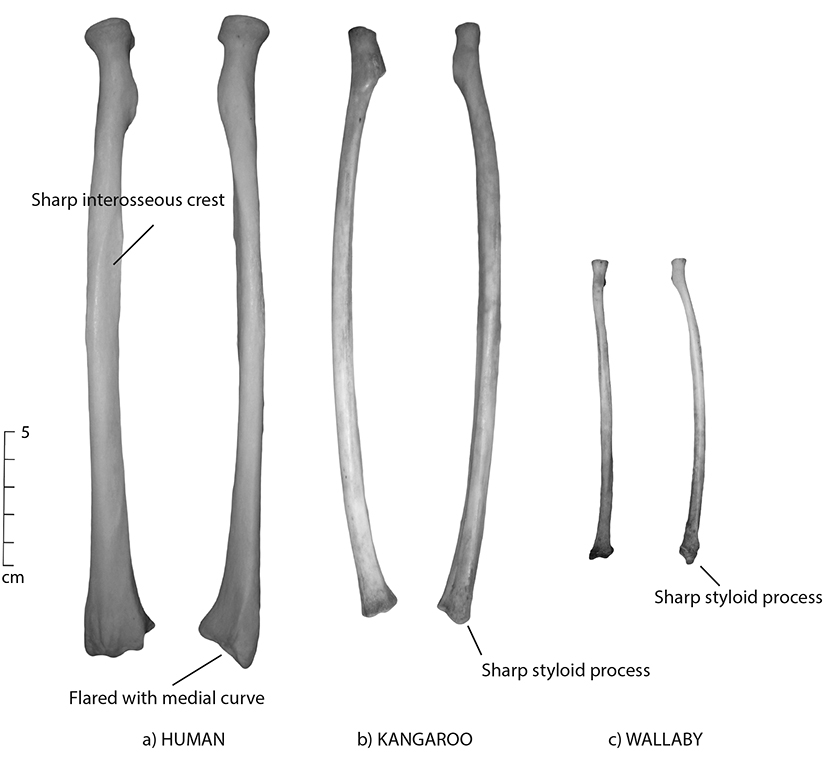

To an inexperienced eye, human and kangaroo radii can appear quite similar. To differentiate between the two, consider the following (see Figure 4.2):

- Human radial shafts bear a sharp interosseous crest along their length, while in macropods this crest is very subtle and is only present on the upper third of the shaft (near the proximal end).

- Proximally, human radial heads are very round, while in macropods these are oval in shape. An unfused kangaroo radius may be easily confused with an unfused human radius. The head of the macropod radius is flush with the shaft, while the head of a human radius protrudes outward at the epiphyseal line. It is especially important that an expert be consulted if there is a possibility the bone could be human (see also the comparison of the proximal human and macropod radii given in Figure 4.8).

- The distal human radius is flared and curves medially, with the appearance of an askew triangle, while a straighter shaft and a sharp, distinct styloid process characterise the distal macropod radius.

Figure 4.2: Human and macropod radius compared; (a) human, (b) kangaroo and (c) wallaby.

Distinguishing between humans and others

- A human radius has a very prominent, sharp crest along its shaft.

- A human radius can be differentiated from that of a carnivore by the kidney bean‒shaped proximal articulation of the latter.

Other comparisons

- The radius and ulna are fused in adult horses, cattle and sheep (Figures 4.3 and 4.4a).

- Ungulate (hoofed animals) radial shaft fragments are characterised by a long appearance that is ‘flattened’ anterio-posteriorly, often with traces of an ulna shaft remnant on the posterior surface.

- When fragmentary, the proximal and distal portions of the radius of large ungulates are commonly mistaken for the distal tibia.

- The distal radius of quadrupeds is characterised by a set of ‘ridges’ (which may be canted) for articulation with the carpals.

- A dingo’s radius (Figure 4.5d) is flatter than a cat’s radius.

- The radius of a wombat is curved with a sharp interosseous crest that begins half-way down the shaft and creates a flattened distal half (Figure 4.4c).

- The radius of small macropods (e.g. wallabies, Figure 4.5c) is nearly indistinguishable from the radius of possums (Figure 4.6f). Use a comparative collection for differentiation.

Common state in archaeological assemblages

The radius of many quadrupeds, especially cows, horses, sheep and pigs, is one of the few long bones that is frequently found intact in archaeological contexts. Since the radius is commonly a robust bone for its size in these species, it tends to preserve quite well. In large species utilised for meat (e.g. cattle), primary butchery of a carcass tends to make an initial cut just above, or at, the articulation of the radius and humerus to disarticulate the upper from the lower leg. In smaller European ‘food’ animals (e.g. sheep or pigs), the radius and ulna are often left articulated with the humerus to form a leg cut (e.g. ham or lamb) that may be cooked with the bone intact. Rabbit radii are commonly intact, as rabbits were commonly cooked whole. These European cultural patterns of meat consumption generally result in relatively complete radii in good state of preservation in historical archaeological contexts. The radii of other species are subject to different preservation. For example, emu radii are rarely found intact, as the wing is either one of the first body parts to be scavenged or is left behind by hunters who take the meatier leg and torso back for consumption. In kangaroos, wallabies, and wombats there is little meat on this element, and it may also be left behind by hunters interested in higher meat-bearing elements. In naturally accumulated assemblages, macropod radii are commonly found articulated with the entire hand or wrist (ulna, radius, carpals, metacarpals and phalanges), as even scavengers tend to ignore this element. The same pattern is commonly encountered in dingoes, cats, rabbits, wombats, possums and similar small species.

Figure 4.3: Posterior and anterior views of the fused radius and ulna of (a) horse and (b) cow.

Figure 4.4: Posterior and anterior views of radii; (a) sheep radius with a fused ulna, (b) pig radius and (c) wombat radius. In quadrupeds the radius is more robust, and the set of ridges at the distal end that articulate with the metacarpal bones are visible on the pig and sheep.

Figure 4.5: Posterior and anterior views of the radius; (a) human, (b) kangaroo, (c) wallaby and (d) dingo.

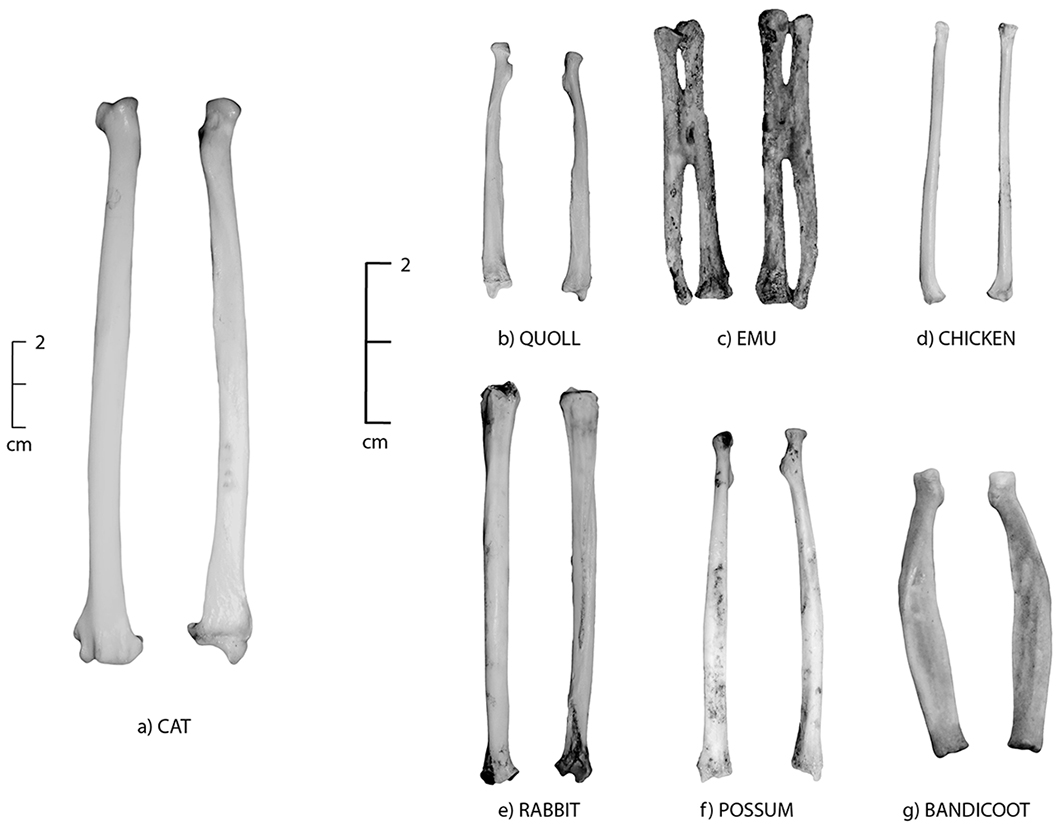

Figure 4.6: Posterior and anterior views of the radius; (a) cat, (b) quoll, (c) emu, (d) chicken, (e) rabbit, (f) brushtail possum and (g) bandicoot (unfused).

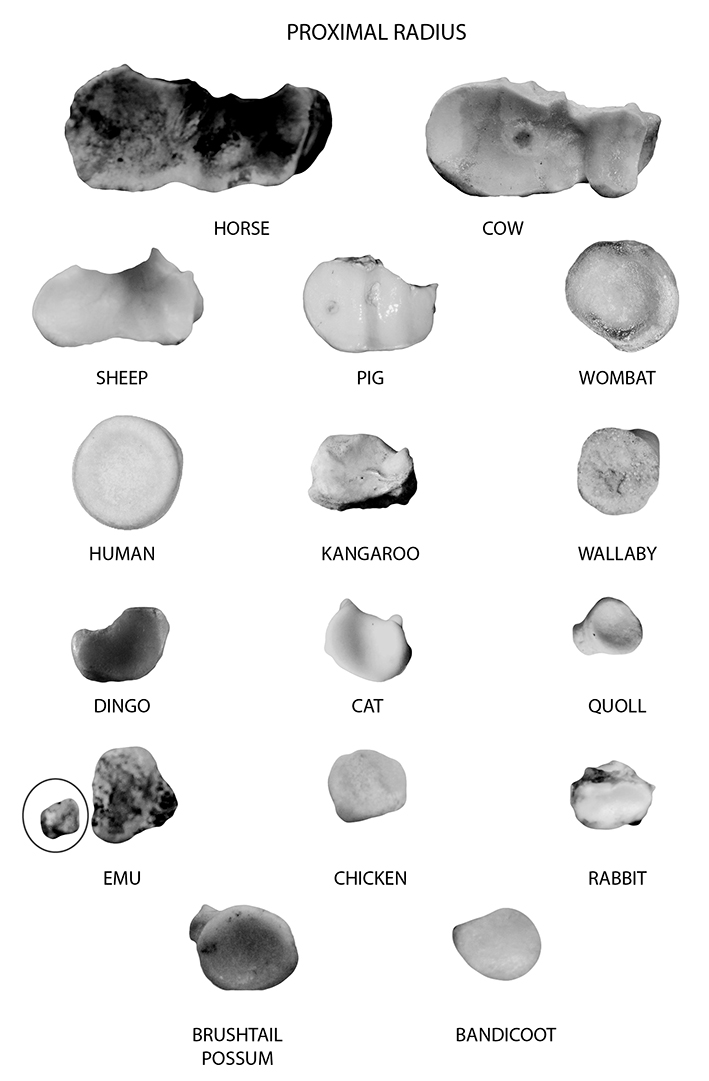

Figure 4.7: Proximal radius of all species (in order of decreasing size). The emu radius is circled.

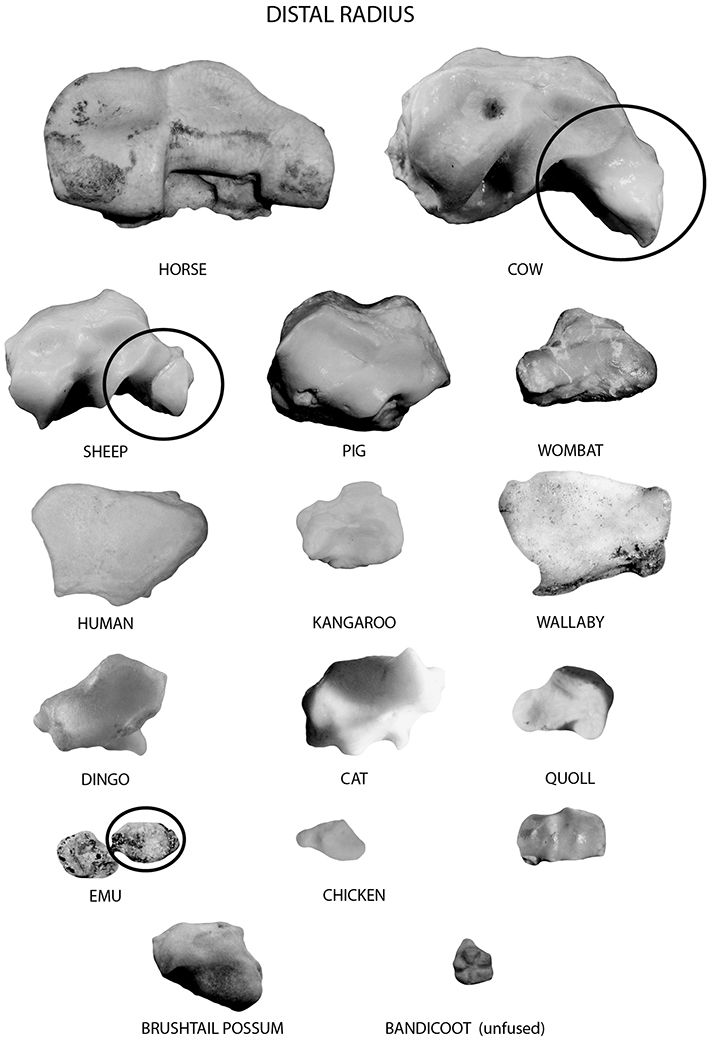

Figure 4.8: Distal radius of all species (in order of decreasing size). Those of smaller species are shown at an exaggerated size to show detail. The cow and sheep ulna remain attached and are circled. The emu radius is also circled.

Figure 4.9: Radius decision process. |