2

Scapula

The scapula, or shoulder blade, is a flat bone with a raised ridge, readily identifiable when complete. When fragmented, the distal portion (neck and glenoid fossa) is commonly recovered from archaeological contexts, and is one of the easier bones to use in the identification of species.

Diagnostic features

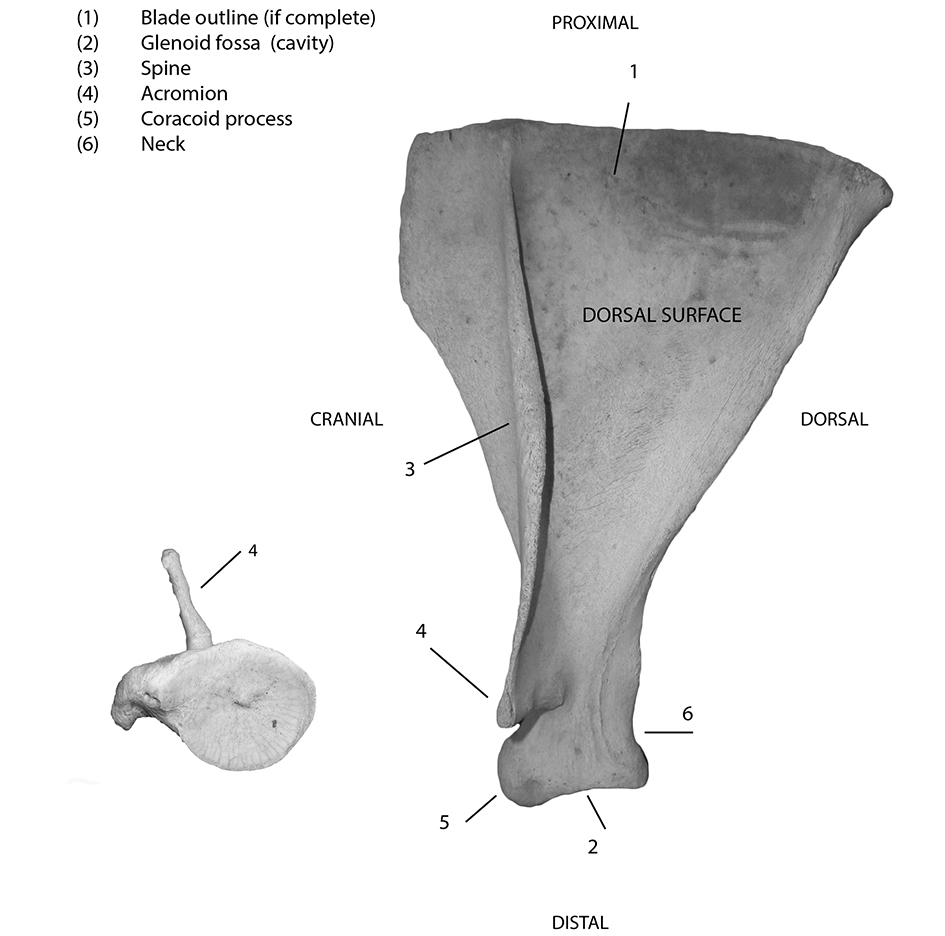

Diagnostic features of the scapula are shown in Figure 2.1. The scapula is distinguished by its triangular shape (1), which is often fragmented in archaeological assemblages. The distal articulation or glenoid fossa (2), articulates with the humerus to form the shoulder joint, and its morphology is diagnostic of species. The spine (3), which rises off the blade on the dorsal surface, is also a diagnostic feature of the scapula, as is the swollen process at its end, the acromion (4), which articulates with the clavicle. The coracoid process (5) extends out from the cranial side of the neck (6) on the dorsal side. The distal scapula is one of the most diagnostic bones for species identification.

Figure 2.1: Sheep scapula with orientations and diagnostic features labelled.

Orientation and siding

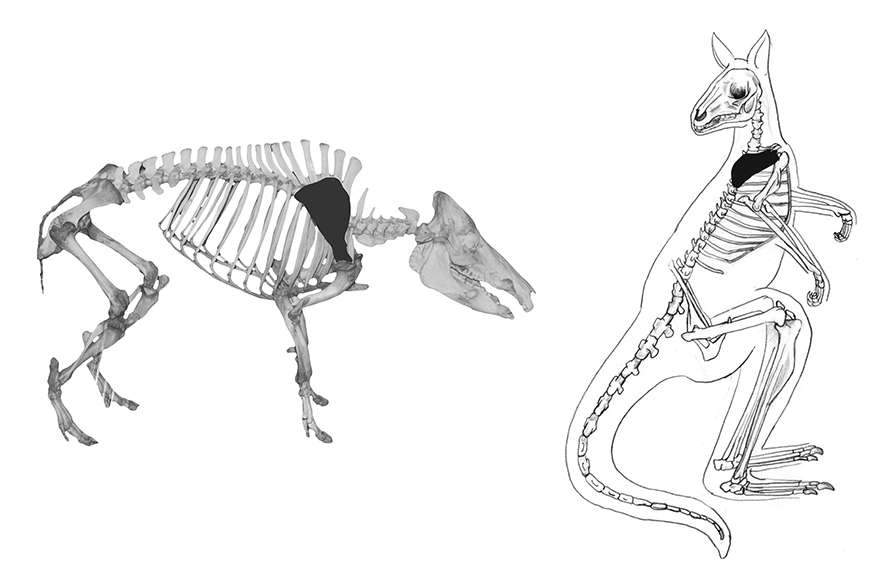

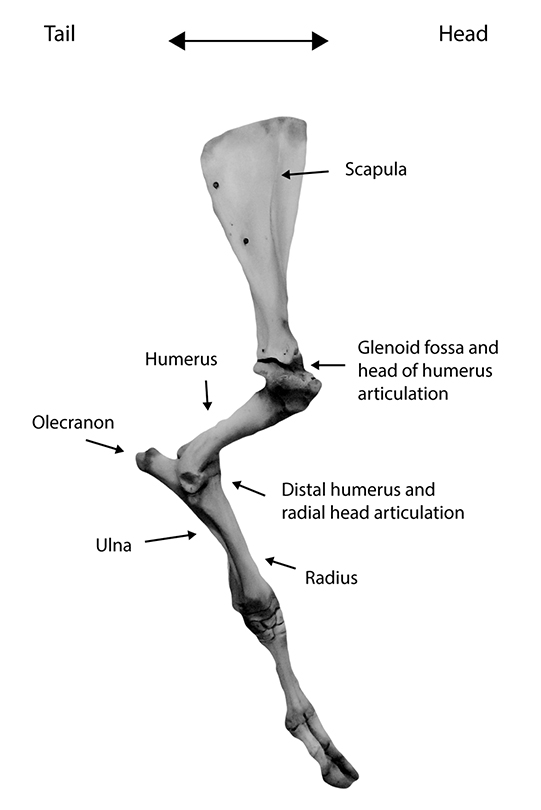

In both humans and animals, the spine points to the glenoid fossa. In quadrupeds, the scapula rests on the dorso-lateral surface of the trunk, and the spine and glenoid fossa point down when in anatomical position (see Figure 2.2). In humans and macropods (kangaroos and wallaby), however, the scapula rests on the upper back, and the spine appears horizontal when in anatomical position. To side the scapula in quadrupeds (Figure 2.2), orient the bone so the spine is lateral (to the side), the glenoid fossa points downward, the coracoid process is anterior (forward), and the more ‘rounded’ side of the blade is nearer the individual’s head. In bipeds, orient the bone so the glenoid fossa is lateral and the spine is horizontal.

Figure 2.2: Articulated cow fore leg (right) illustrating the articulation of the scapula and humerus.

Species identification

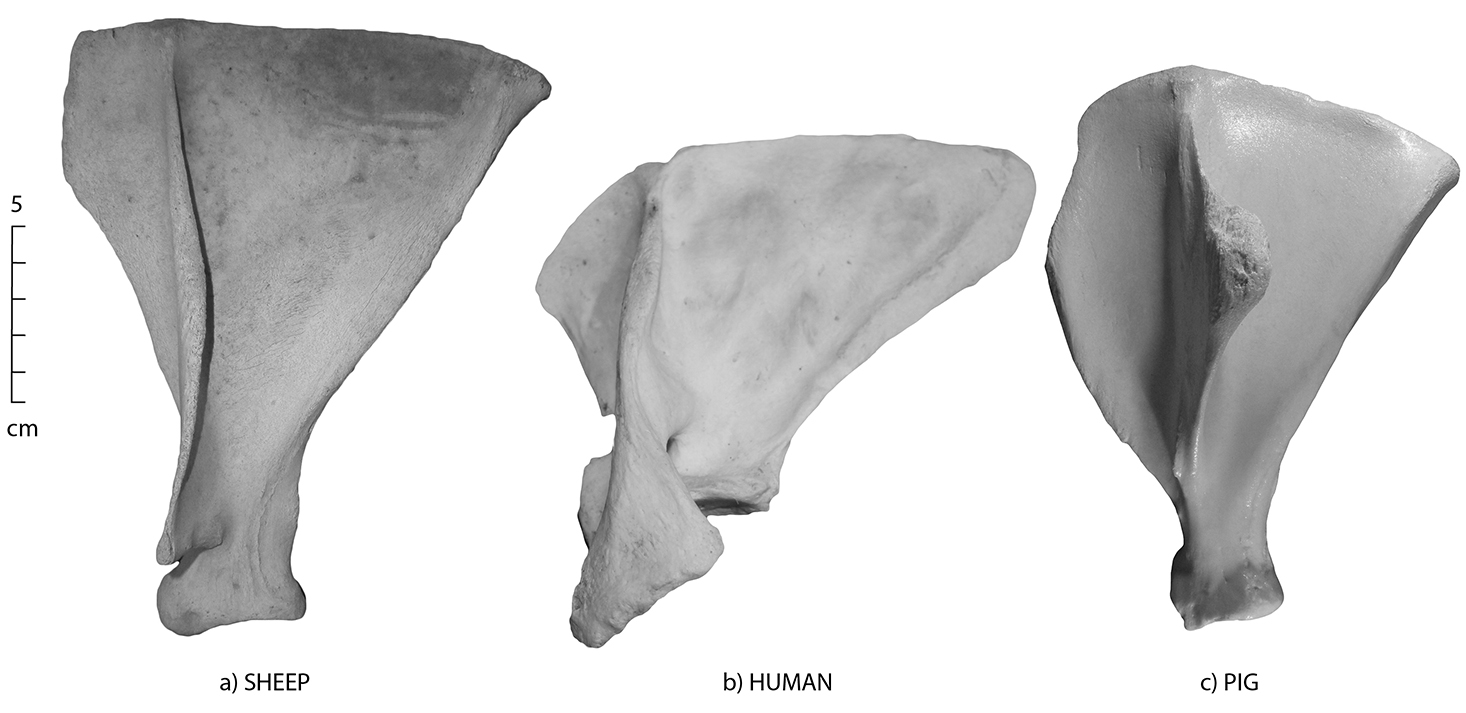

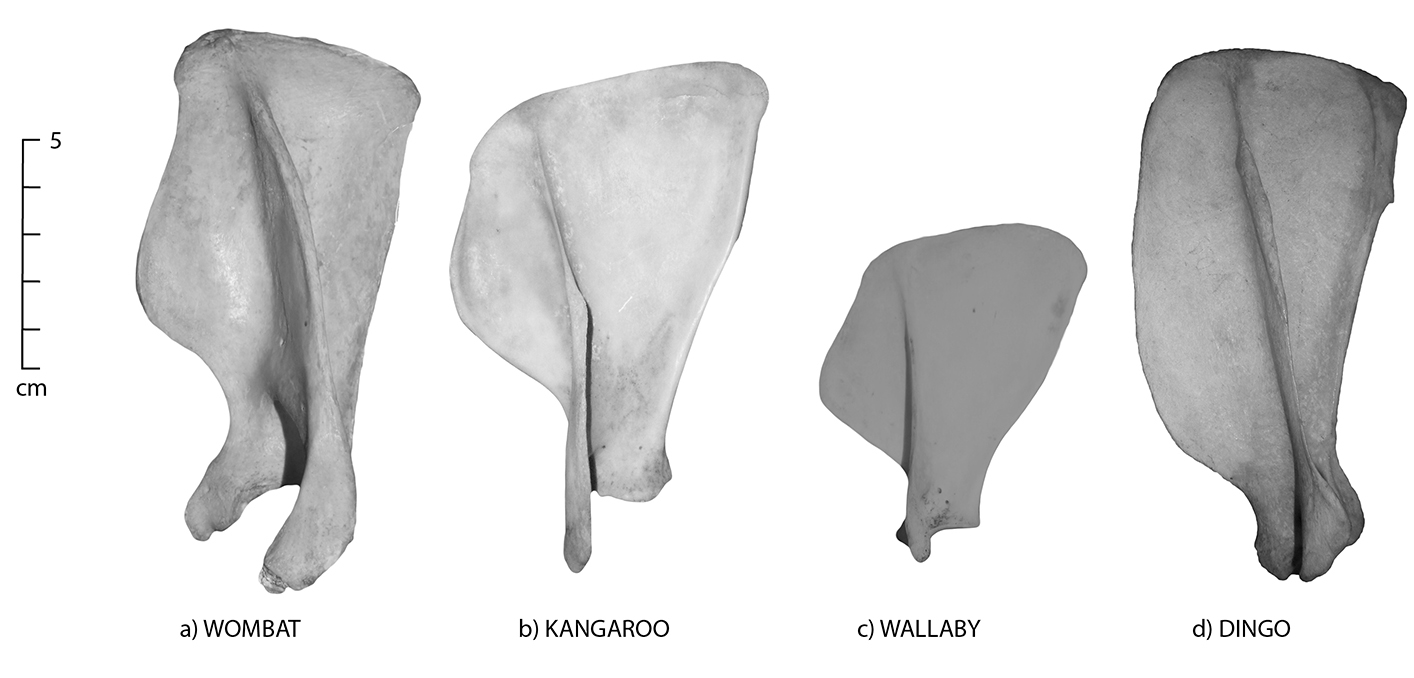

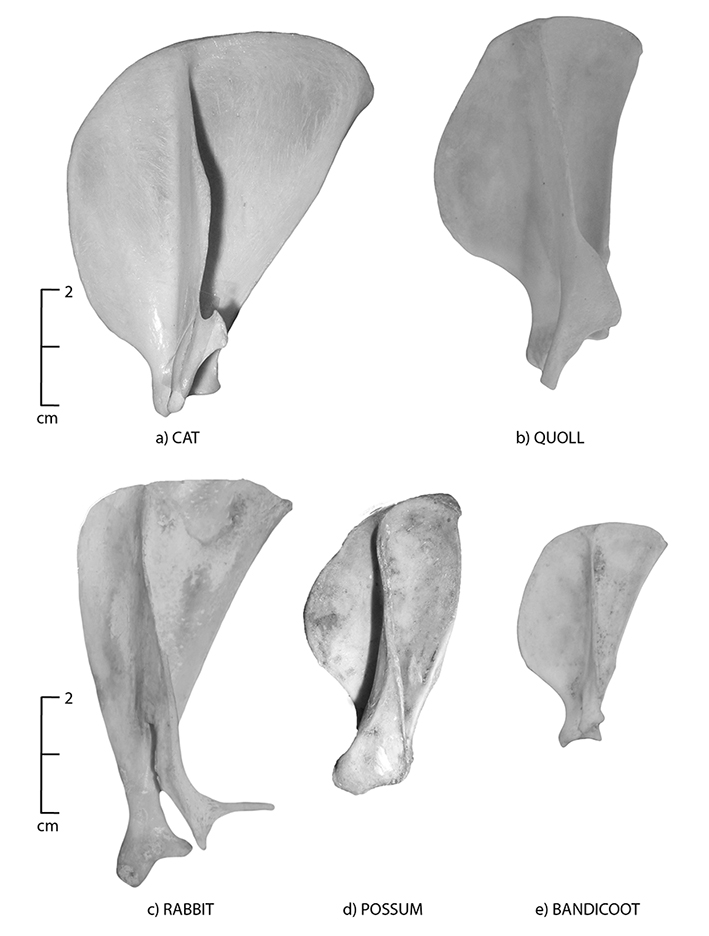

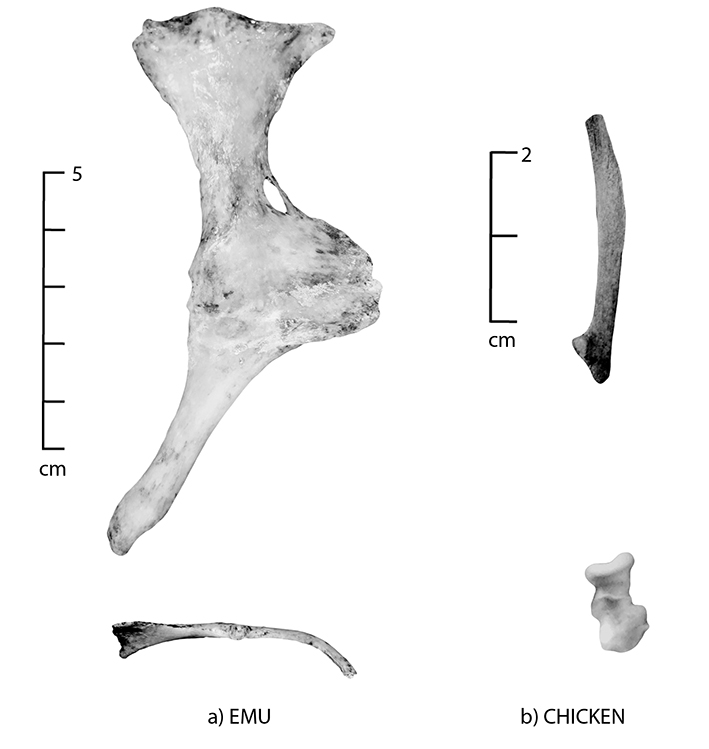

Refer to Figures 2.3–2.8 for species identification using the scapula.

Distinguishing between humans and animals

- The shape of the scapula is elongated in most non-human animals.

- The shape is triangular in humans (Figure 2.4b).

Blade outline

- If the scapula is complete, use the blade outline and the length of the spine and acromion for species identification.

- The blade outline is an elongated triangle in cattle (Figure 2.3b), sheep (Figure 2.4a), and pigs (Figure 2.4c).

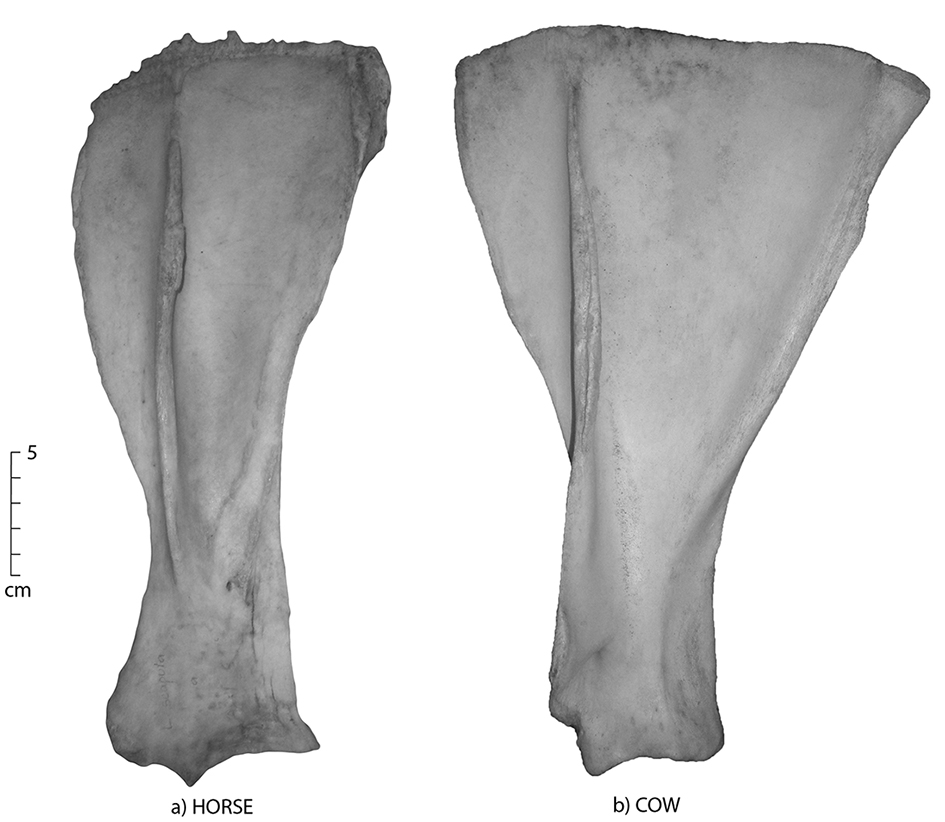

- The blade outline is tall and narrow in horses (Figure 2.3a).

- The blade is almost rectangular in shape in dingoes (Figure 2.5d).

- The blade outline is a rounded triangle in macropods (Figures 2.5b and c).

Acromion

- The acromion extends beyond the glenoid fossa in kangaroos, wallabies, possums, wombats, and humans.

- It is nearly even with the glenoid fossa in dingoes, cats and quolls.

- It flares posteriorly in rabbits.

- The distal acromion is flared and triangular in shape in humans.

- There is no acromion in horses or pigs.

Neck

- If only the medio-distal portion of the scapula is extant, with a missing and/or broken spine, use the neck for species identification.

- The neck is long and flattened in horses.

- The neck is long but less flattened in cattle.

- Sheep and pigs have a distinct, short neck.

- Macropods, dingoes and cats have a short neck which is barely visible.

- Rabbits have a very slender, narrow and distinct neck.

- Humans have a neck barely recognisable as a distinct feature. It is very broad, and flattened dorso-ventrally.

Glenoid fossa/coracoid process

- If the distal portion of the scapula is extant, but the neck is missing, use the shape of the glenoid fossa and/or coracoid process for species identification (Figure 2.8).

- The glenoid fossa is rounded in cattle, sheep, horses, pigs and cats.

- The glenoid fossa is teardrop-shaped in kangaroos, wallabies, humans and possums.

- The glenoid fossa is oval-shaped in wombats.

- The glenoid fossa is almost rectangular in dingoes.

- The coracoid process is curved and projecting in rabbits, dingoes and humans.

- The coracoid process is strongly developed in horses, and visible in cattle, sheep and pigs.

As in all elements, general size is a good way in which to differentiate between species. When following the decision processes, always use size as both an initial and final determining factor in species identification.

Common state in archaeological assemblages

The distal end of the scapula (neck and glenoid fossa) is commonly intact, but the blade is often missing and/or broken; the spine and acromion are commonly broken, especially in humans, cats, dingoes, kangaroos, wallabies, possums and rabbits. Cut marks are commonly found around the neck and glenoid fossa, resulting from disarticulation of the joint, and may also be found on the blade as a result of skinning.

Figure 2.3: Scapula in dorsal view; (a) horse and (b) cow.

Figure 2.4: Scapula in dorsal view; (a) sheep, (b) human and (c) pig.

Figure 2.5: Scapula in dorsal view; (a) wombat, (b) kangaroo, (c) wallaby and (d) dingo.

Figure 2.6: Scapula in dorsal view; (a) cat, (b) quoll, (c) rabbit, (d) brushtail possum and (e) bandicoot.

Figure 2.7: Scapula in dorsal view and detail of glenoid fossa; (a) emu and (b) chicken.

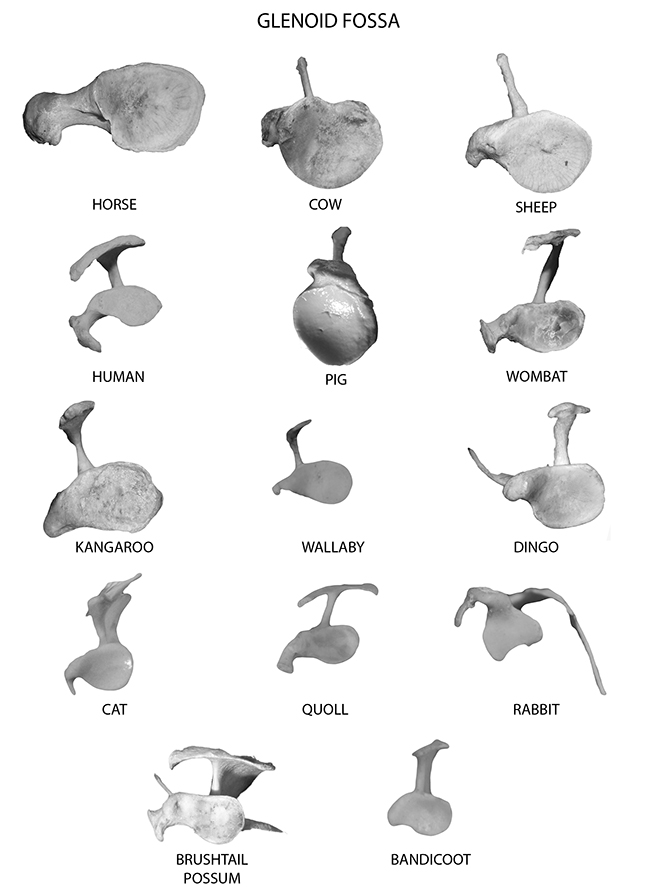

Figure 2.8: Distal views of the glenoid fossa of all species. Those of smaller species are shown at an exaggerated size to show detail.

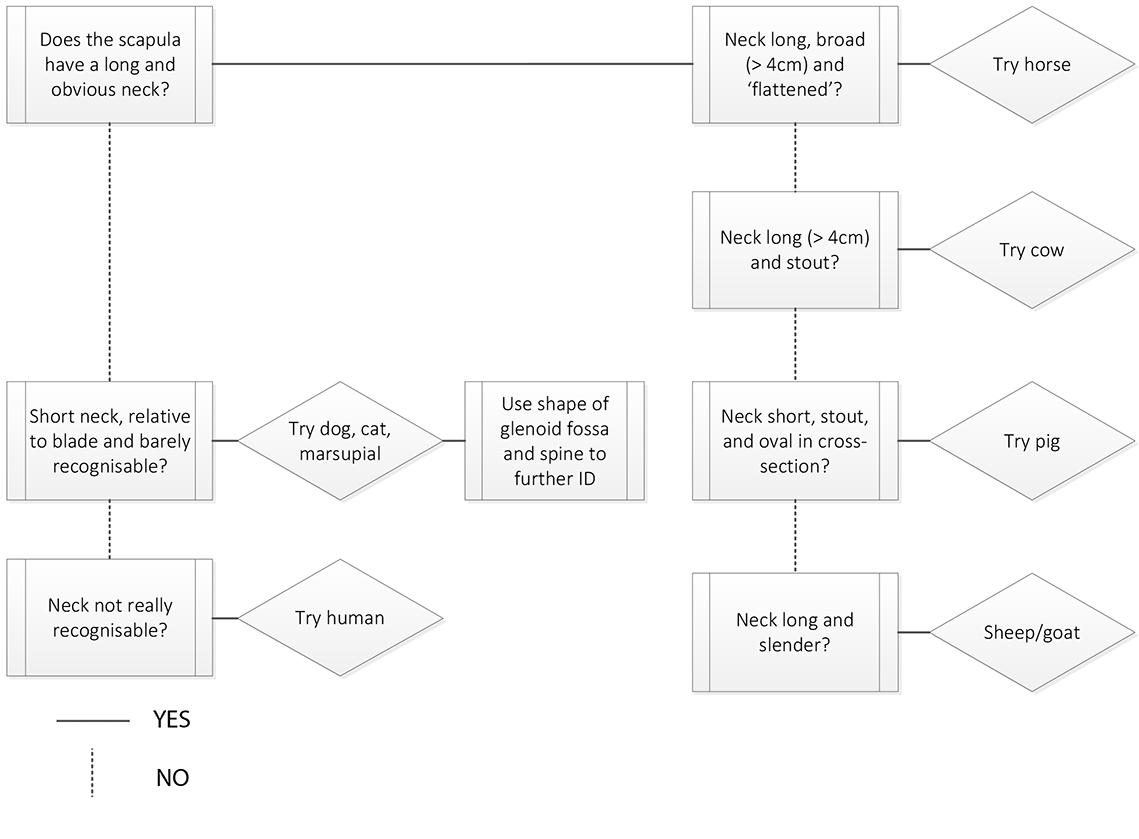

Figure 2.9: Scapula decision process 1. Use this decision process if the scapula is complete or if the medio-distal end is extant (using the neck, glenoid fossa, acromion and/or coracoid process). |

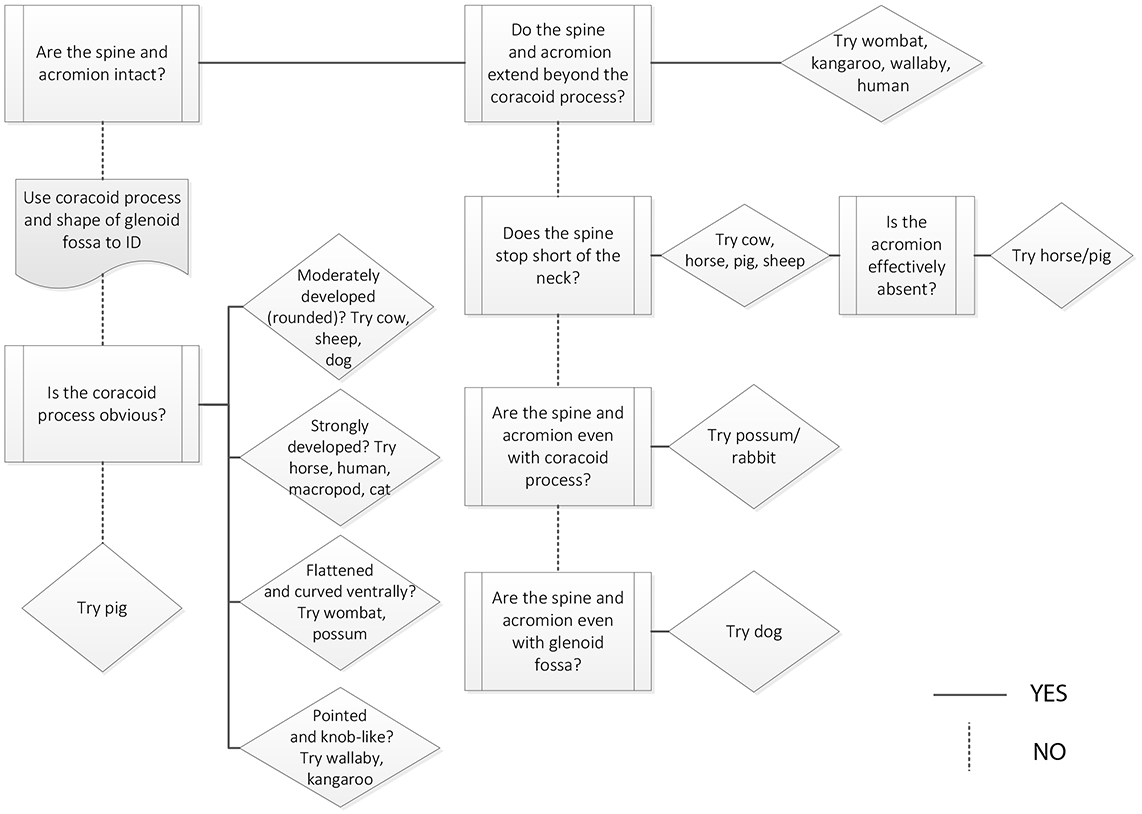

Figure 2.10: Scapula decision process 2. Use this decision process if you only have the acromion and coracoid process |