Contribution 1

Mysteries of origin: early traders

and heroes in the Trans-Fly

Those who are familiar with traditional Australian mythology will know of the accounts of “travelling creators,” heroes or beings of the primeval era, or “dreamtime,” whose exploits in creating the landscape and its inhabitants are narrated in continuing episodes from one people to the next. Allowing for cultural and linguistic differences, the identity and very often the name of the creator is retained from one region to another. Usually the “track,” or route, followed by such a hero is likewise continuous from one people’s “country” to the next, so that knowledgeable people can tell a visiting ethnographer where their accounts leave off and those of the next people along the track begin. The result is a common “track” that coordinates the origin traditions of diverse cultures over many hundreds of miles of terrain.

Fewer people, perhaps, are aware that similar accounts of travelling creators, and of their routes, are found on the island of New Guinea. They occur, in fact, along the south coasts of the Western and Gulf Provinces, in adjoining areas of West Papua, in southern areas of the Simbu Province, and on the Torres Strait Islands – largely in regions that lie in near proximity to Australia. During my anthropological research among the Daribi people of Mt. Karimui,1 I was told, after considerable hesitation, several accounts of the creator Souw, and those who told me the stories were able to map out his route. But if I wished to know what had happened to Souw beyond a certain point, they added, I would have to ask the Pawaian speakers who live in the Sena River valley to the east of Mt. Karimui. I was able, subsequently, to collect accounts of the hero and his route from the Sena River Pawaians and from those of the Pio River, to the southeast of Mt. Karimui.2 During a visit to a population of Polopa (Foraba)-Daribi speakers living on the lower Erave, an additional account, linked closely with local landscape features, came to light, recounting the hero’s adventures before he entered the Karimui area. Most intriguing, however, was the name with which the Erave people identified their 286hero – Sido, the very name associated with the hero of a very similar myth by the people of Kiwai Island in the mouth of the Fly River.

The Polopa-Daribi speakers of the lower Erave had no knowledge, at that time, of the Kiwai people or their mythic tradition, and it seems certain that no single people within the 800 kilometre range of the complex was ever aware of its total extent. Yet there is a compelling similarity of imagery and thematic content, as well as a geographic continuity of the hero’s route and a linguistic cognacy in the names attributed to him, that argue powerfully for the unitary nature of the complex. Even more significant, perhaps, is the place that many of the myths occupy in the religious cosmologies of the respective cultures. Whereas they may or may not involve the creation of the earth and its landforms, as they do at Karimui, they almost invariably address crucial questions of human mortality, of fertility, and reproduction, and of how these are related to one another: how did it come about that man must die? How is death related to sexuality and human relationships? The myths are basic, epitomising articulations of these essential religious or philosophical issues, and as such they are often treated as repositories of revealed power, sacred mysteries, and secret knowledge. The Daribi withheld their accounts of Souw from Australian administration officials, missionaries, and linguistic missionaries, and disclosed them to me only after they had become certain of the nature of my work. In his book Dema, J. van Baal relates the amazing story of how some interior Marind-anim villagers suffered imprisonment and ritual discrediting (by showing their bullroarers to women and uninitiated children) rather than reveal their version of the myth of Sosom.3

Clearly there is more to a myth than a mere plot or story; on the level of the individual culture, it has a profound meaningful relationship to the people’s conception of the world and of the human place within it. On a broader, intercultural level, as a complex or tradition shared, knowingly or unknowingly, by a number of cultures with different languages and cosmologies, it can tell us something about the contacts and historical affinities among those cultures. Whether we choose to identify the unifying factor with a specific event or happening, with a widespread affinity in conceptual thinking, or with some combination of these, there is more to myth than mere story on this level too.

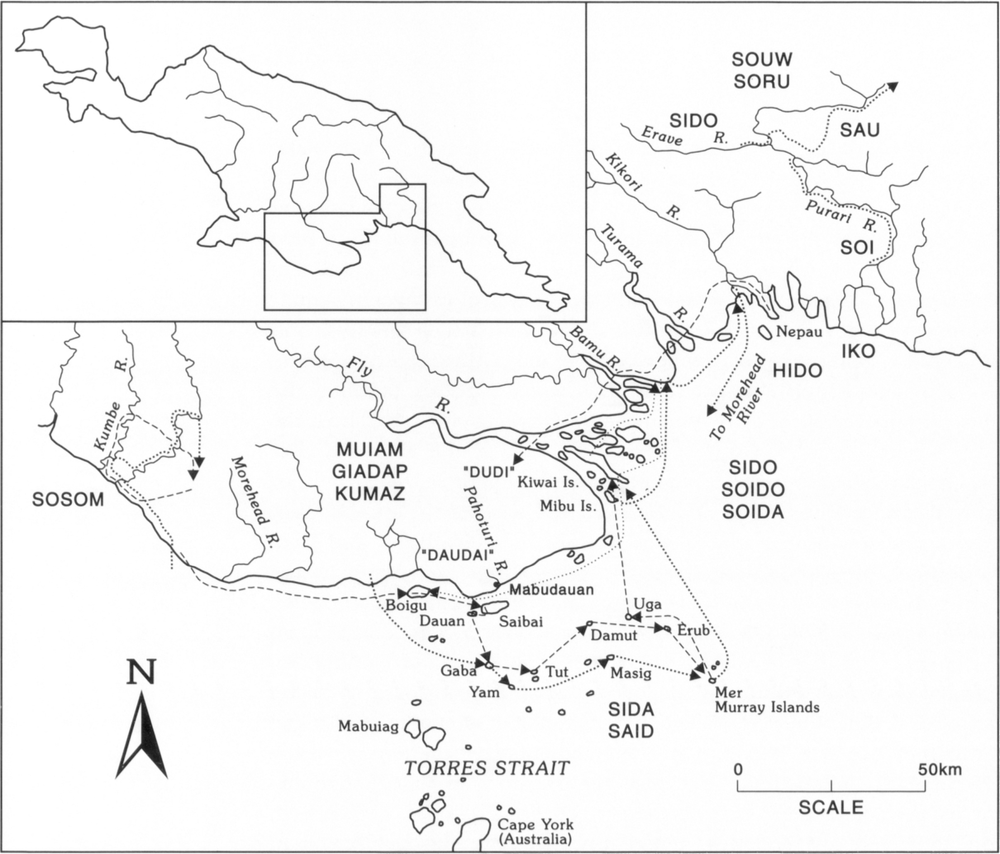

The known extent of what have been called “Papuan Hero Tales,” the tradition with which we are concerned here, is from the Marind-anim of West Papua to the southern part of the Simbu Province of Papua New Guinea, at Karimui (Figure 63). The stories, and reported travels of the hero, are more or less continuous between these points. Traditions of a travelling creator are found elsewhere beyond these points, 287particularly in the eastern highlands of Papua New Guinea, but only within the area designated do the names and stories appear to be clearly cognate. From Torres Strait eastward and northward, the hero is said to have come from the west, initially, and moved eastward (“from Sadoa where the Togeri [Tugeri] men come from” in a Torres Strait version).4 West of Torres Strait, however, among the Marind-anim (the so-called “Togeri men”), the tradition is that Sosom, the hero, came from the east, and indeed, according to van Baal, the Dema (creative spirit) Sosom is said to return yearly from the east during the east monsoon as a presence during initiation rites.5

Figure 63: Routes of heroes and creators in southern New Guinea.

The reversal in direction here suggests a centering of the tradition somewhere roughly in the Trans-Fly-Torres Strait region. It is, moreover, in this area that we find, in some cases, alternate versions of the story co-existing, and mention of certain place-names far beyond their local areas. This is not surprising, as the peoples of this region are great travellers; not only did the Marind-anim themselves conduct their famous raiding expeditions far to the east along the coast, but the 288Kiwai people of the Fly estuary knew the coast intimately as canoeists, and maintained a far western settlement at Mabudauan,6 at the mouth of the Pahoturi River, opposite Torres Strait. Adding to this the fact that Austen collected the legends of Hido, clearly variants of the Kiwai Sido story, among the Gope, a people (one of several between the mouths of the Bamu and Kikori Rivers) he identifies as being “of Kiwai extraction,”7 it appears likely that the Kiwai and those with whom they were in immediate contact carried the tales over much of their central range.

In his monograph The Folk-Tales of the Kiwai Papuans, probably the most extensive collection of Melanesian mythology ever published, the Finnish ethnographer Gunnar Landtman8 records the Kiwai myth of Sido in 22 episodes, most of them followed by a long list of variant, or alternative, versions. The text is followed by a section of “songs of Sido” and an Addendum of related stories from the Kiwai area and from various of the islands in and around Torres Strait.9 Interestingly, the name of the hero varies in the accounts quoted from the Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to the Torres Straits from Sida on Saibai and Mabuiag to Soida on Kiwai Island itself.10 Landtman follows his discussion of Sido with the tale of what he considers to be an altogether different hero, Soido, “the promoter of agriculture,” and provides a list of related stories.11 He comments that the Reports of the Torres Straits Expedition mix together the tales of Sido and Soido under the name of Sida, the Bestower of Vegetable Food, and indeed, the Cambridge expedition’s “Soido” tales include episodes found in Landtman’s “Sido” epic.12

It is clear that Landtman wishes to distinguish the motif of Sido, as “the first man who died,” from that of Soido as a “promoter of agriculture,” and tends to regard any association of these motifs within a single story as a result of confusion or misidentification. But it is also true that the final episode (43) of Landtman’s (main) Sido text, recounting Sido’s adventures in Adiri (“at the extreme western border off the world”), is virtually identical in its content with the Soido stories. Sido, the first man who died, brings agriculture to Adiri, located far to the west, in exactly the same way (e.g. by ejaculating food plants through his large penis) as Soido, in Landtman’s own account, brings agriculture to the Torres Strait Islands.

Whether we are dealing with a confusion of two myths here, or a diffusion of one, is less important than the implications of the issue itself for our interest. The name of the hero (Sido, Sida, Soido, Soida) is interchangeable, but the location of the Soido episode (sexual introduction of food plants) is invariably to the west of Kiwai - at Adiri or on the Torres Strait Islands. Thus the far-ranging Kiwai would appear to have incorporated two separate versions of the hero myth 289within their extensive mythology. One of these, the “Kiwai” version, is that of Sido, who brought death into the world. The other version, identifiable with the Torres Strait Islands, that of the sexual introduction of food production, has both been incorporated within the Sido epic, as an episode recounting the hero’s adventures far to the west, and presented as a separate tale, that of Soido.

Landtman’s distinction between the two versions is, nevertheless, significant in that the shift in thematic emphasis from one to the other corresponds to the reversal in the direction of the hero’s route discussed above. In the Torres Strait tales collected by Rivers and Haddon,13 and in van Baal’s accounts of the Dema Sosom among the Marind-Anim,14 the hero is a bringer of food plants and of human fertility and growth, all mediated through the agency of his large penis. To the north and east of the Trans-Fly-Torres Strait juncture, beginning with the Kiwai tale of Sido, the hero’s adventures, and even his often prodigious sexuality, have the opposite implication – that of the origin of death rather than life. From Kiwai northward and eastward, across the Papuan Gulf and up the Purari watershed, this emphasis on the origin of human mortality is consistent, suggesting that the myth itself moved thence.

The implication here is that the successive regional variations of the myth were in some sense derived from, or based upon, an original model corresponding to something like the Kiwai story of Sido. Recurrence of the name “Sido” on the lower Erave River would tend to confirm this, though the name “Soi,” recorded in association with a similar myth by Egloff and Kaiku on the lower Purari,15 points rather to “Soido.” There is, nevertheless, a further consideration here, one that reconstructions based on straightforward word-of-mouth transmission or diffusion might fail to take into account. This is that mortality, reproduction, and food production are powerful themes, and are likely to be central to any people’s ideas and values and they relate to the interpretation of life and human action. Their origin is the origin of the human condition as this is made sense of in the symbolisations of a particular culture, and so the way in which the account of their origin is articulated will necessarily reflect the indigenous ideas and values. To the extent that these “hero tales” have been accepted as vital and secret knowledge by a range of diverse cultures, they have been diversified on the model of those cultures’ differences.

Thus, for example, the hero’s large penis serves as a conduit for plant domesticates and a device linking these to human sexuality in the Torres Strait stories, but is an immoderate and stealthy implement of violation in the Karimui and Purari tales. Among the Marind-anim, where the hero Sosom is associated with a boy’s initiatory cult 290involving sodomizing practices, the story involves the severing of the long penis following its entrapment in heterosexual intercourse, leaving a remnant useful only in sodomy.16 In effect, Sosom’s enlarged penis becomes an ideologically justifying foil for non-heterosexual insemination practices.

It is through a series of such selective re-interpretations that the Kiwai conception of Sido, the son “of everyone” born of his father’s connection with the earth, the “first man who died,” who nevertheless arose from his grave as a light,17 and thus seemed to Landtman’s informants as being “all same Jesus Christ,”18 undergoes a transformation into the being of which my informants at Karimui said “you call him God, we call him Souw.”19 Souw is the to nigare bidi, creator of the land, who cursed mankind with death, but is himself immortal. Thus in addition to the life/death inversion that we encounter in moving from Torres Strait to Kiwai, there is an additional inversion of the hero from the victim of mortality to its perpetrator. The process of reinterpretive adaptation would seem, as Lévi-Strauss might suggest, to rely heavily upon inversion.

The continuities are no less apparent for all of this. The Daribi name “Souw” is a contraction of “Sorouw,” given as an alternative name for the hero. “Sorouw,” also the specific for a kind of grass, seems in turn to represent a phonetic approximation of the Polopa name Sido, in that Daribi phonology tends toward a kind of “harmonising” of vowels and avoids the combination of extreme front and back vowels within a single word. Thus the sequence of names, moving from Kiwai through Gope to Polopa, and finally, Daribi, is Sido-Hido-Sido-Sorouw (Souw), by no means an unnatural or unexpected phonological transition by Melanesian standards. There are also fairly explicit similarities between the Kiwai and the Karimui peoples, including the basic longhouse frame (shared also by the Gope and Polopa); a report on blood groups among the Karimui peoples cites impressive statistical evidence to the effect that “in particular, the Kiwai have ABO, P and MNS gene frequencies strikingly similar to those of Karimui.”20

It is as difficult, perhaps, to distinguish historical from adaptive or accidental connections in population genetics as it is in myth; we know little about gene frequencies in the populations between Karimui and the Fly River estuary, and the possibility of accidental similarities always exists between peoples with a similar general genetic makeup. In the present case, however, there is something of a progressive change, or tendency, in the construction of the plot itself as we move from Kiwai to Karimui, and this tendency complements both continuities of the myth and the hero’s names, and the inversions noted above. The basic heterosexual relationship in the Kiwai Sido tale 291is conjugal – Sido meets his death in a conflict arising from a separation with his wife. In the Gope tale, however, Hido (or Waea) is seduced by his sister, and in his shame he embarks on a journey to the land of the dead, followed by the sister, Hiwabu.21 (From this point eastward the woman, a blood relative, follows the hero, rather than vice-versa as in the Kiwai story). On the lower Erave and at Karimui the hero is shamed through his attempts to copulate with a (virgin) woman who is clearly much younger (perhaps generationally) than he is, and in all cases it is the hero’s daughter, not involved in the sexual attempt, who sentimentally follows her departing father.22 In the tale of Soi recorded by Egloff and Kaiku on the middle Purari, Beri, the victim of the sexual attempt, addresses Soi as “grandfather,”23 though it is Soi’s nephew, Hoa, who accompanies him afterwards. The sequence of transformations here is a most intriguing one: from the conjugal relationship as the moral and motivational fulcrum of the story we proceed to the sibling relationship, thence to the father-daughter bond, and finally, at least in formal terms, to that between grandfather and granddaughter. As we pass from a conception of the hero as “all same Jesus Christ” to one more nearly suggestive of Jehova, the connection between the hero and the significant female protagonist becomes more intense and, often, forbidden, and the hero’s status becomes increasingly enhanced in contradistinction to an increasingly dependent woman. Whatever else might be said of this tendency, the very fact that the transition is a regular and systematic one argues for the integrity of the mythic tradition itself, and supports the likelihood of a common derivation.

Successive versions of the tale, as we move eastward, also tend to intensify the relationship between the sexual motivation of the hero’s journey and the loss of human immortality. In the Kiwai story of Sido, the relationship is almost incidental: Sido is killed by Meuri, a rival lover of his wife, and his soul follows his body toward the land of the dead. Along the way, in a seemingly unconnected episode, Sido attempts to shed his old body and regain life, but he is disturbed by some boys and is thus unable to achieve rejuvenation.24 Among the Gope, however, Hido flees to the land of the dead after being ashamed in incest with his sister, and sheds his skin en route in an effort to escape detection. Farther to the east, on the lower Erave, at Karimui, and on the lower Purari, the curse of human mortality follows directly upon the frustration and sexual anger of the hero, thus culminating the resonance between the two dialectically related themes.

Thus the eastern versions can be understood as a result of a process of condensation or distillation of the dialectical polarity in the course of the tale’s transmission. This would, again, point to the possibility of 292an origin farther to the west, perhaps among the Kiwai. But the association of sexuality and mortality in these stories also seems to be involved with another motif that is only vaguely suggested in the Kiwai and Gope tales, and is absent from the Torres Strait and Marind-anim versions. This is the identification of the hero, in various ways, with a snake, and the association of the snake with a bird. Since the association of a bird and a snake with accounts of human origin or mortality occurs elsewhere, in Melanesia, as well as Australia, it is possible that the “eastern,” or interior Gulf versions of the hero tales represent a blending together of two traditions. This would certainly not deny or controvert the evidences noted above for derivation of the tales from the west, but it does deserve consideration.

Heider reports an origin myth episode among the Dani, a large people inhabiting the Baliem Valley in the highlands of West Papua, in which a python and a bird symbolise contrasting immortal and mortal destinies; man chooses to be like to a bird, and thus foregoes the ability to rejuvenate himself by shedding his skin.25 Among the Polopa and Daribi, the huge penis of Souw is identified by a bird as a “snake” as it becomes erect in the bush, and the bird gives its characteristic cry, thus signalling women to come and look for the reptile. (Identification of the hero with a snake is strengthened at the end of these tales when he sheds and “throws down” his skin for men to take up). Interestingly, the bird, kaueri, that cries out in these stories is either the same species as, or closely related to, the Black Cuckoo or Koel (Eudynamis orientalis) that saves the creator-python Kunukban,26 the hero of a series of Australian “travelling creator” myths.

A mythic tradition as widely and diffusely ramified as this is doubtless an old one indeed. But there is a persistent strain of symbolic or ideological interpretation among the Daribi people of Mt. Karimui that corresponds to its general premises. This is a contrast between human beings and birds based on the fact that the Daribi language uses a single word, ge, with reference both to the pearl shells used traditionally as the major item in bridewealth and the eggs of birds (and of other creatures, including snakes). In effect, then, both human beings and birds, for instance, reproduce themselves through ge. But human beings do so by passing their “eggs” around from one group to another and never hatching them, while birds and reptiles retain their “pearl shells” and transform them into their young. A whole complex of Daribi origin myths relating to pearl shells, various birds, and hairless creatures generally, has been developed around this theme.27

Whether or not the Daribi share any sort of historical connection, via their mythology, with the Dani people of the Baliem Valley or with any aboriginal Australian peoples is difficult to determine. Such 293similarities may simply be based on the practice (widespread in Melanesia, and not unknown elsewhere in the world) of using radically different kinds of animals to symbolise different mortal states. It is likely, for instance, that any new origin account, or even any new factual material relating to human existence, introduced to the Daribi would have been interpreted in terms of such a contrasting symbolism, and adapted to it. In discussing Dani totemism, in fact, Heider28 cites evidence that just such an interpretation was made of Europeans by the Dani. Dani, who symbolise themselves as “birds,” often speak of Europeans as “snake people,” and considered them, in many cases, to be immortal (this was still a widespread assumption among older Daribi - possibly for the same reason – in 1968).

In any case, the bird/snake/human contrast amounts virtually to an abstract cosmological principle when compared with the highly explicit details of plot and motif that can be traced in virtual contiguity from the Trans-Fly region up through Karimui on one hand, and into the Marind-anim area on the other. Moreover, all of the evidence we have reviewed here indicates the likelihood of a specific point of origin for the complex of “Papuan hero tales” somewhere in the region of the junction of the Torres Strait Island complex and the Trans-Fly.

Billai Laba’s account (Contribution 2) of “Oral Traditions about Early Trade by Indonesians in Southwest Papua New Guinea” is highly significant in the context of these evidences, for it provides specific information about foreign contacts at an early period in just the area where the mythic differentiation seems to have taken place. At the very least, Laba’s account offers a highly likely historical source for the continuities of the “Papuan hero tales”; beyond this, however, it furnishes an ethnohistorically strategic and plausible means for the introduction of a basically Middle-Eastern set of mythic motifs into a Melanesian region. Unless some sort of diffusion from Malayan, Indonesian, or other nearby Islamic traditions can be shown to be a likelihood, many would be tempted to ascribe these motifs and their introduction to the message of recent Christian missionising activity – a very unlikely source, considering the likely time-depth of the Papuan tales and the degree to which they have been incorporated into local religions and cosmologies.29

In this regard, it is most intriguing to speculate on the nature of the buk mentioned in Laba’s discussion, and also on the school established at Waidoro and on what the content of its lessons might have been. (The suggestion that rituals and secrets of the fertility of coconuts were taught, and the school ceased operation because of a young girl’s pregnancy brings the whole matter very close to the content of the Papuan hero tales themselves). It seems most probable that the buk 294amounted, as Laba suggests, to trade diaries, though the possibility that they were copies of the Koran or some other religious book should not be ruled out. Either the buk, or, more probably, the siikull, could have provided vehicles for the introduction of Islamic or other, related Middle Eastern mythic motifs.

The complex account involving a first man and woman, the original instance of sexual “knowledge,” man’s loss of immortality, and, very often, a snake or serpent, is widespread in the mythologies and religious traditions of the Middle East, and is part of the religious beliefs of many sects and traditions originating there. A version has been incorporated into the Book of Genesis of the Christian Bible, and is also known in Islam. The myth itself, however, seems to predate the founding of these religions. It is difficult in a cursory account to do justice to the philosophical profundity of the mythos, which involves not only man’s differentiation from other creatures, but also the deep, dialectical relationship between sexuality, reproduction, and death – that reproduction implies death just as death necessitates reproduction. In my work I have found that the Melanesian tales are no less profound in this regard than the Middle Eastern ones – in some cases they seem more so.

I have been circumspect here regarding the mythic elements that might have been brought across in an Indonesian contact largely because – although this may not be generally known – any of the great old-world religions is surrounded by an extensive unofficial or semiofficial apocryphal literature. Thus it would be very difficult to predict what variants or versions of a proliferate kaleidoscope of mythology might have been introduced, and through what local mythic traditions they may have been perfused or varied along the way: of what syncretisms were the Papuan hero tales a synthesis, and themselves a syncretism? In fact, the Middle Eastern myth that the Papuan hero tales, and in particular, the Kiwai tale of Sido, most resemble, is neither Christian nor Islamic, but the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, known from the empires of Sumer and Akkad in the third and second millenia BC. The Gilgamesh Epic is either the original version of a myth that was later incorporated into other religions and other texts, or else it was merely an earlier adaptation of a myth that was already old by the time of Sumer and Akkad. Gilgamesh was a kind of superhuman, gigantic in his abilities and appetites – a dominator of men and seducer of women. To control him the gods create a wild man, Enkidu, whom Gilgamesh succeeds in overcoming and befriending. After Gilgamesh refuses to marry Ishtar, the goddess of love, she sends a bull to destroy him. Gilgamesh and Enkidu subdue the bull, but the gods decided that Enkidu must die. He falls 295ill, and dreams of the “house of dust” that he must enter; when Enkidu dies, Gilgamesh is overcome, and sets out on a journey across the world to find the secret of immortality. Guided by Utnapishtim, survivor of the deluge, he finds a plant that restores youth, but this is stolen from him by a snake while he is at a waterhole. Saddened and resigned, he returns to tell humanity of the land of the dead.

Like the Kiwai Sido, who was conceived of the ground by his father, Enkidu in the epic is made of mud. Sido’s troubles, and fate, like those of Gilgamesh, arise from his spurning a woman - not the goddess Ishtar but the lovely Sagaru, his wife, to whom he refuses sex. When Sido is killed in a fight with her next lover, Meuri, it is the latter who grieves over him, much as Gilgamesh grieves over his friend and rival Enkidu. Sido then journeys over the earth to find a means of rejuvenating himself, but is finally frustrated at a famous waterhole on Boigu Island, where he is offered a drink from his own skull30 (the Daribi story of Souw is even closer to the Gilgamesh epic in this respect, for in it the snakes and other hairless creatures appropriate Souw’s immortal skin, thus cheating mankind of immortality). Finally, too, Sido, like Gilgamesh, becomes resigned to his (and humanity’s) fate, and prepares the land of the dead for the many who are to follow him. (The similarity in name between the barmaid Siduri in the epic and the protagonist in the Papuan tales is interesting, but probably accidental.)31

Pointed similarities with the ancient Mesopotamian epic relate rather specifically to the tale of Sido and the other “eastern” stories seemingly derived from, or associated with it, rather than those of Torres Strait or the Marind-anim. There are, of course, themes and details shared by all of these stories. In the Gizra origin myth discussed by Laba, for instance, it is stated that all peoples, including Australian Aborigines, Torres Strait Islanders, the Gizra, and other Papuan peoples, originated at the place called Basir Puerk. Many of the Daribi Souw texts name a similar legendary or ancestral place, the kunai grass plain on the Tua River called Bumaru, associated with Souw in the stories, as the place of origin of all peoples.32 As the Gizra account names Giadap as ancestor of dark-skinned peoples, and Muiam of those with lighter skins, so some of the Souw tales name Souw’s daughter Yaro as ancestress of all light-skinned peoples, and her friend (or stepsister) Karoba as ancestress of dark-skinned peoples.33

Despite these similarities, the names of the Gizra protagonists, Giadap, his younger brother Muiam, and the single woman Kumaz (originator of death and musical instruments) do not seem to share cognacy with the Sosom-Soido-Hido-Iko-Souw series. Interestingly, however, the notion of a woman who was the originator of death and 296the founder of cultural practices is shared among the peoples of the Fly-Sepik Divide, around Telefolmin, in their common tradition of “The Old Woman”. She is called Afek (by Telefolmin), Afekan (by Tifalmin), and Karigan (among the Faiwol). In many of the mythical accounts, including specifically those involving the origin of death, she interacts with her younger brother, who is portrayed as very clever, and who becomes the first man to die. This brother, quite similar to Muiam, the “younger brother” of the Gizra account, bears a name - Umoim at Telefolmin,34 Wolmoiin among the Faiwol - that could easily be a cognate of “Muiam.”

Is there yet another mythic “track,” additional to the Sosom tales to the west, the Soido stories of Torres Strait, and Sido-Souw series to the northeast, radiating northward from the Trans-Fly and into the Star Mountains? The possibility bears exciting historical implications, but more will have to be known of the likelihood of intervening links before it can be entertained seriously.

Were such an interior connection of the Gizra myth to be established, we would have solid evidence of the radiation of mythic traditions in all directions from a focal centre (Basir Puerk?) of Indonesian trade connections in the southwest of Papua New Guinea. The possibility of ethnohistoric links to the “Mountain Ok” peoples of the Fly-Sepik divide recalls, however, the caveat discussed above. Peoples like the Telefol and the Faiwol have become famous recently in the ethnographic literature35 for the epistemological sophistication of their conceptual orientation and ritual life. Since this conceptual and ritual world centres on the ban, or male cult-initiation system, which is, in turn, based on the mythic corpus of the “Old Woman” complex, it is evident that the use that these peoples have made of what may be a very widespread historical legacy is very much a product of their own creativity. This is no less true, of course, for peoples like the Kiwai, the Daribi, and the Gizra, but what it implies is that the historical source of such a complex is perhaps less important, in terms of the significance of the myths for the peoples themselves, than the ways in which this source has been interpreted and elaborated upon in each particular case.

Nonetheless, the likelihood that the origin traditions and even the secret knowledge of a number of Melanesian peoples owe their own origin to an early epoch of cultural contact is a matter of prime ethnohistorical importance. Whether the interconnecting routes of the heroes map out actual journeys in the past, or just simply the journeying of the stories themselves, they trace out a sphere of religious and conceptual communication. Whether the tales deal, like those of Sido, Souw, Soi, and Gilgamesh, with the loss of human 297immortality, or whether they concern the bringing of life and fertility like the stories of Soido and Sosom, they concern the central truths of life and death that can be found to animate the core symbolisations of most or all Papua New Guinea cultures.

Whether they actually communicate something to the indigenous peoples, or whether, as I suspect, they merely reveal to them aspects and implications of their thought (through the shock of alienation and the consequent self-consciousness) that would never otherwise have been realised, cultural contacts like the one that is in evidence here are extra-processual events. They are unusual impingements, and carry their own momentum. But this is no reason to conclude that such events were necessarily few in number, over long historical periods.

In his monograph on the Waropen people of Cendrawasih Bay, G.J. Held lists a number of honorific titles in use there that clearly and obviously derive from Moluccan originals,36 and he notes that in Waropen mythology, a famous trader from Ternate, Raja Amos, was brought to the area by the culture-hero Kuru Pasai.37 The Waropen possessed also large, whole specimens of what is apparently ancient Chinese porcelain,38 used as brideweath. Granted that an area as far west as this fell well within the nominal domain and trading and tax-collecting ambit of the Sultan of Tidore,39 and hence in a region of known contact with Indonesians, the parallels between this known instance of contact and those reported in Laba’s account are intriguing.

Notes

1. Anthropological field research was carried out among the Daribi people of Mt. Karimui from November, 1963 to February, 1965, funded by the Bollingen Foundation and the University of Washington, and from July, 1968 to May, 1969, funded by the Social Science Research Council of New York and Northwestern University.

2. The texts and the routes, as well as those collected among the Polopa-Daribi of the Erave (identified there as Foraba), are published in R. Wagner 1972: 24–32.

3. van Baal 1966: 491–3.

4. Rivers 1904: 31.

5. van Baal 1966: 267

6. Landtman 1927: 1 01502.

7. Austen 1932: 468.

8. Landtman 1917: 95–116.

9. Landtman 1917: 116–9.

10. Landtman 1917: 118.

11. Landtman 1917: 119–24.

29812. Landtman 1917: 123, variants G and H.

13. Rivers 1904 and Haddon 1908.

14. van Baal 1966.

15. Egloff and Kaiku 1978.

16. Wagner 1972: 21.

17. Landtman 1917: 110, variant B.

18. Landtman 1917: 116.

19. Wagner 1972: 19.

20. Russell et al 1971: 87.

21. Another Gope version is closer to the Kiwai tale than this, see Austen 1932: 474.

22. At Karimui she is called Yaro among the Daribi, and Yuaro by the Pawaian speakers.

23. Egloff and Kaiku 1978: 48.

24. Landtman 1917: 109–10, Episode 36.

25. Heider 1970: 144.

26. Arndt 1965: 242–3.

27. Wagner 1978: 65–90.

28. Heider 1970: 69.

29. In the 1960s, when I first became aware of the relationships among the Papuan Hero Tales, a former colleague, Dr. Phil Weigand, suggested that they might all have their source in epics dating from the conversion of Indonesians to Islam.

30. A photograph of the waterhole is published in Landtman 1917: 111.

31. Beardmore cited in Landtman 1917: 118, G. names the hero as Sidor. Perhaps more to the point of a discussion of the possible introduction of Middle-Eastern mythic themes is the Miriam Island name for the hero: Said.

32. Wagner 1972: 28. An aerial photograph of Bumaru appears in Wagner 1978: 122. c

33. Wagner 1967: 41.

34. Textual material and the source for these comments is contained in an unpublished paper by Dan Jorgensen, “Revelation and Transformation in Telefolmin,” which was presented in the symposium on dynamism in Oceanic cultures at the annual Meetings of the American Anthropological Association, Washington, D.C., in December, 1982.

35. Jorgensen 1981 as yet unpublished, records the exegesis of the Telefol “mother house” at Telefolip. Some implications of the complex are articulated in Fredrik Barth 1980. See also Barbara Jones 1980.

36. Held 1957: 82.

37. Held 1957: 83.

38. Held 1957 depicted in plates 26 and 27, opposite page 98.

39. Given the well-known Melanesian tendency to reproduce an aspirated “t” as “s” (e.g. tobago-sobago), the resemblance between Tidore and Sido (Sidor) should not pass our notice.