14

Trade cycles in outer Southeast Asia

and their impact on New Guinea

and nearby islands until 1920

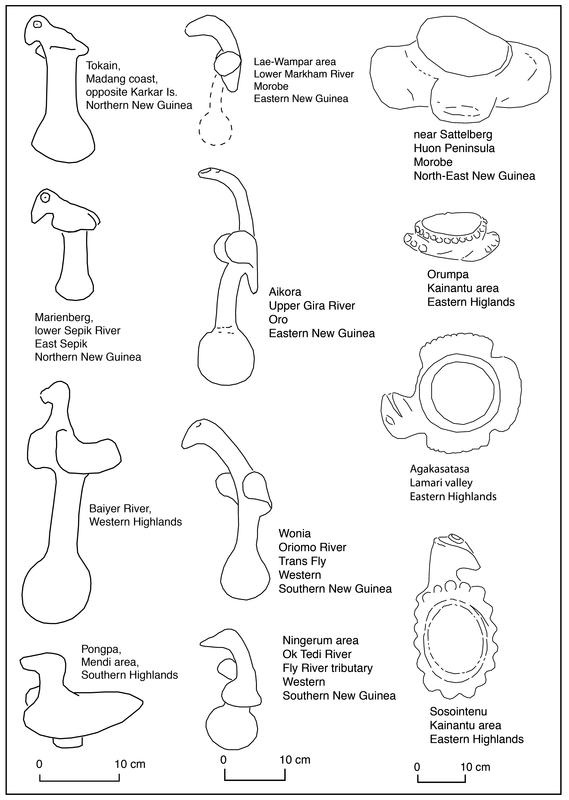

Birds have provided a focus for cultural expression in eastern New Guinea for 5,000 years, since bird heads and wings decorate some of the stone mortars and pestles from highland, lowland and coastal areas (Figure 56). These finds plus other stone mortars and pestles and stemmed obsidian artifacts indicate that substantial trade connections existed in New Guinea by this date (Figure 9). Bird of paradise plumes were presumably amongst the products that were traded.

Initially trade between Asia and outer Southeast Asia was achieved by inter-island trade networks. These interlocking group or community networks allowed goods to travel remarkable distances by means of a chain of trading transactions. Early domesticates of banana and sugarcane from New Guinea were traded to Asia and beyond by 4,000 years ago. The arrival of specialist traders just before 2,000 years ago changed this situation. Trade between Asia and outer Southeast Asia then became dominated by merchants, who at first came from Asia, but later also from Europe. When the Portuguese reached outer Southeast Asia in 1512 the Bandanese were the only group in this region who were transshipping produce to Asia.

The people of New Guinea and nearby islands have long considered their land and all its faunal, floral and mineral resources to be their property. When outsiders come to collect and export local products, resource owners not only reassess the value of their resources but also the nature of their relationships with foreigners. Problems arise when rich resources are exploited and the local inhabitants believe they are not participating in the decision making and receiving what they consider to be a fair share of the profits.

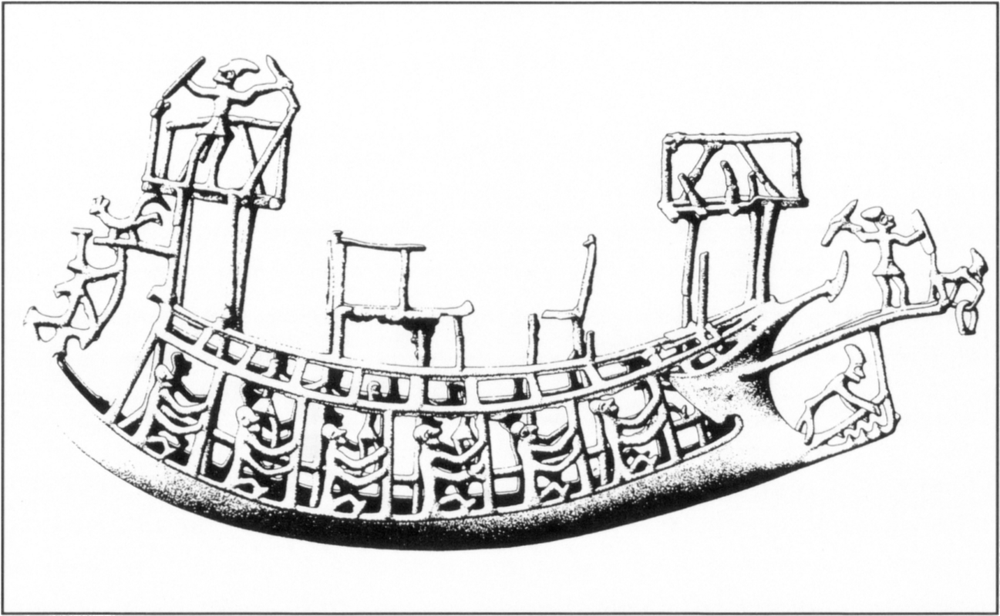

Disagreements of this nature date back to the beginning of specialist interactions with foreigners more than 2,000 years ago. The bronze spearheads and a dagger found in the Jayapura region (see Figure 45), as well as the militant nature of the bronze boat miniature found in Flores (see Figure 57), indicate that the first specialist traders faced confrontations. In historical times the first uprisings against the Portuguese in the Spice Islands occurred a little more than a decade after they had established a permanent settlement there in 1522. By 1574 the Portuguese had been driven from Ternate. The Bandanese managed to keep European merchants from establishing bases in their islands somewhat longer, only to be devastated by the Dutch in 1621 when they failed to uphold a trade agreement. This brought about the end of Banda as a regional trade entrepôt.

270Dutch records for the Moluccas, which date from 1814, when they established a regular administration in these islands, document a history of constant litigation. This occurred not only between itinerant traders and local rulers, but also amongst local inhabitants as to who owned and had the right to exploit commercially valuable resources.1

Rebellions and litigation continue in outer Southeast Asia. In 1989 the Australian-owned copper mine on Bougainville was closed by rebels seeking to secede from Papua New Guinea. In addition to the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA), there are also the West Papuan Freedom Fighters (OPM) in West Papua and the Fretilin forces in former Portuguese Timor. Arrangements for the exploitation of mineral resources in Papua New Guinea by such multinational corporations as the major oil companies and Rio Tinto Zinc (and its subsidiaries CRA and Kennecott) remain contentious.

Figure 57: Bronze miniature boat found in Dobo village on Flores in eastern Indonesia. Parallels with Dong Son art suggest that it was made in the first century AD in North Vietnam. It was probably imported to Flores early in the second century AD.

Source: Spennemann 1985a. Reproduction courtesy of the Linden-Museum, Stuttgart.

272The first cycle: plumes and specialist Asian traders

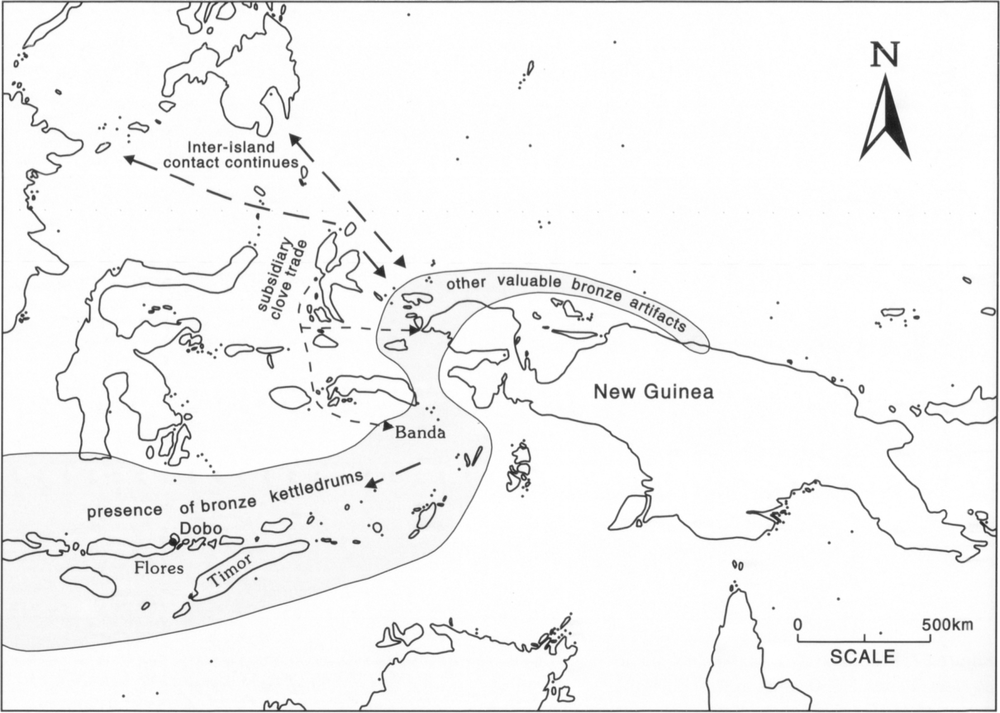

The plumes reaching Asia via inter-island trade brought bronze-using traders to New Guinea, just as spices subsequently attracted Asians and later Europeans to the Spice Islands. This Asian plume trade dates from just prior to 2,000 years ago to about 300 AD. The specialist traders were probably able to obtain the products and safe passage they sought by presenting exotic goods to local community leaders. These leaders in turn incorporated many of the goods they received into traditional exchange networks, thus establishing alliances and fostering peace within their own societies. Such exotic goods would have been keenly sought as their acquisition indicated social ascendancy, and by the same token inability to acquire them indicated failure in this regard.2 The militant nature of the bronze miniature boat (Figure 57) found at Dobo in Flores, eastern Indonesia, as well as bronze weapons found elsewhere, suggests that some early traders were also prepared to fight if the friendly relationships established on the basis of gift-giving failed to protect them.

273The appearance of large valuable bronze artifacts in eastern Indonesia can be seen as marking the arrival of outsiders seeking rare natural products. Large ornamented bronze vessels, clearly intended to impress as display items, occur from the Asian mainland to Java and through the Sunda chain as far as New Guinea (Figure 58). In Soejono’s view,3 those found in eastern Indonesia are some of the finest examples of these bronzes. As we saw in Chapter 3, the infatuation with plumes in Asian kingdoms led to a high demand for bird of paradise skins. The trail of these large bronze artifacts to New Guinea and not the Spice Islands is the archaeological verification of this interest.

Bronze and glass artifacts themselves do not extend, with the exception of the Manus fragment, beyond the New Guinea mainland, but influences derived from contact with people using these artifacts did extend by means of local trade systems further east4. These influences are evident in stone skeuomorphs of bronze artifacts5 and certain design motifs which occur in Manus, Sepik, Oro and Milne 274Bay Provinces and the Bismarck Archipelago within what is now Papua New Guinea.6

The second cycle: forest products – spices and aromatic woods

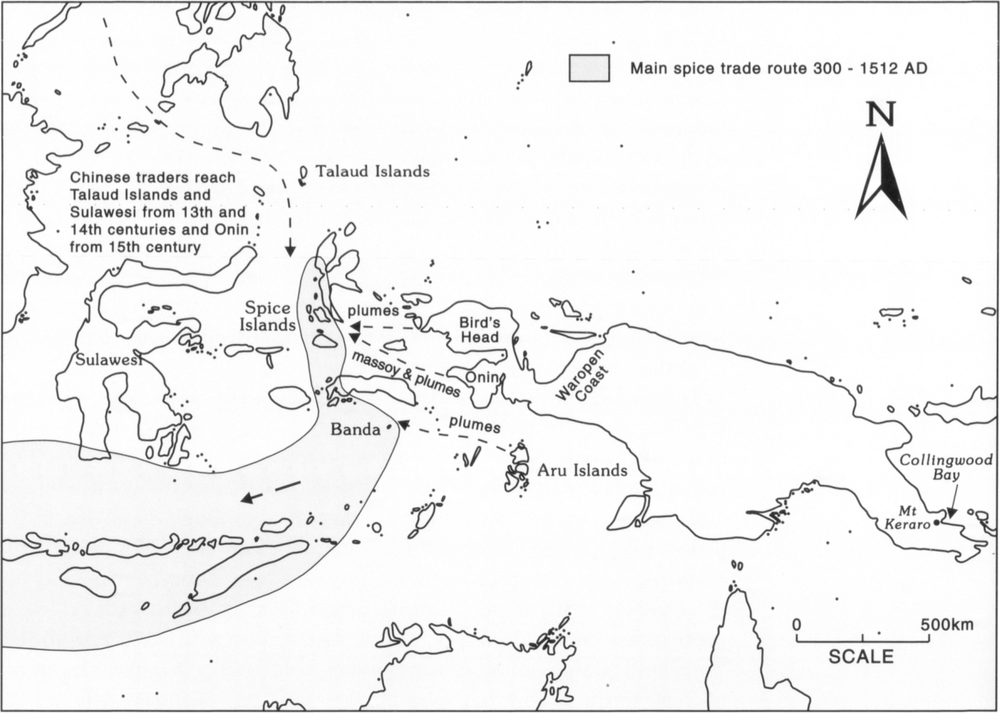

By 300 AD changing demands in Asia had led to a declining interest in plumes. Other forest products were sought instead, notably spices and aromatic woods and barks. Knowledge of their existence in eastern Indonesia would have been gained during the plume trade and it is likely that during this time there was some trade in these products. As the interest in plumes declined, the small islands off western Halmahera, as well as the Banda Islands and Timor, became important centres respectively for cloves, nutmegs and sandalwood. When these products had become the main products sought by traders, they went directly to their source and plumes then became a minor trade item, provided by local traders to these new centres (Figure 59).

The Spice Islands are located some 400 kilometres to the west of New Guinea. When the world demand for spices began to grow early in the first millennium, some Southeast Asians probably wondered whether volcanic islands rich in spices, like the Moluccas, existed at the eastern end of New Guinea. It is not known whether such investigations occurred in prehistoric times. The British did check out this possibility when they were seeking an alternative source of spices when the Moluccas were under Dutch control. That other islands rich in spices might be found at the eastern end of New Guinea was acted on when Captain John MacCluer found wild nutmegs on the west coast of New Guinea in 1791. A private expedition to the eastern end of New Guinea was financed by some merchants in Calcutta and made by Captain John Hayes. He investigated the Louisiade Archipelago but found nothing of economic interest. On his voyage back to India he decided to promote a spice growing venture on the Bird’s Head. This led to the establishment of the first European settlement on New Guinea at Doreri Bay, near modern day Manokwari, on the northwest coast of West Papua.7

Figure 59: Main spice trade route 300–1512 AD.

By 1400 AD the profits to be made from trading in cloves, nutmeg and mace had given rise to interlocking merchant networks which came to extend all the way from eastern Indonesia to medieval Europe. This caused a spice boom and increased trade in the Indonesian archipelago. Malay was the lingua franca of the traders in Indonesia and international contacts with the west led to Islam being spread along the trade routes. By 1500 Melaka had become the most important entrepot in Southeast Asia. Chinese, Indian, Malay, Javanese and other traders came to exchange goods there. Javanese traders supplied most of the cloves and nutmegs from the Spice 275Islands, as well as sandalwood from Timor.8 The Javanese came to the Spice Islands via the Sunda Islands. Chinese traders became active in the Talaud Islands, Sulawesi and presumably the Spice Islands in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, reaching Onin and possibly also the Waropen coast on the New Guinea mainland in the fifteenth century (Figure 59).

As the use of spices increased in Europe, ships were launched into the unknown to seek their source. Once this was discovered, mercantile powers from Europe sought to dominate the spice trade by their military might. They soon found that conquests of trading centres did not always give them the financial rewards they sought. For instance, the Portuguese took Melaka in 1511, thinking it would give them control over trading transactions in the region. They were mistaken. Instead, this Portuguese takeover led to the dispersal of trade to other parts of the archipelago. Asian merchants and traders moved into eastern Indonesia and established new trading centres, particularly Makassar in the state of Gowa in southern Sulawesi.

In eastern Indonesia Dutch intervention was far more disruptive than that imposed by the Portuguese, as the Dutch attempted to gain a full monopoly of the spice trade for themselves through their Dutch East India Company.

During the early phase of European contact, the growing world demand for spices – pepper from western Indonesia, cloves, nutmeg and mace from eastern Indonesia – not only stimulated trade in these commodities, but also led to increased production. The inhabitants of the Spice Islands and nearby islands responded to what they envisaged to be an insatiable demand by Asians and Europeans for cloves and nutmegs by planting more trees. In the long term this was not sustainable, as the world demand for these products did not continue to grow, so painful structural adjustments by producers and suppliers were required. The spice glut came in the 1630s. From 1632 the price for cloves began to decline.9 The Dutch tried to ease the clove and nutmeg glut by not only destroying cultivated trees to reduce the supply but also by introducing trade restrictions. From 1653 the Company started paying annual subsidies to the Sultans of Ternate and Bacan, and from 1657 the Sultan of Tidore, in lieu of their foregone spice profits. By this time the trade monopoly and extirpation activities of the Dutch East India Company had seriously disrupted economic ventures in the Moluccas and it ceased to be a prosperous region.

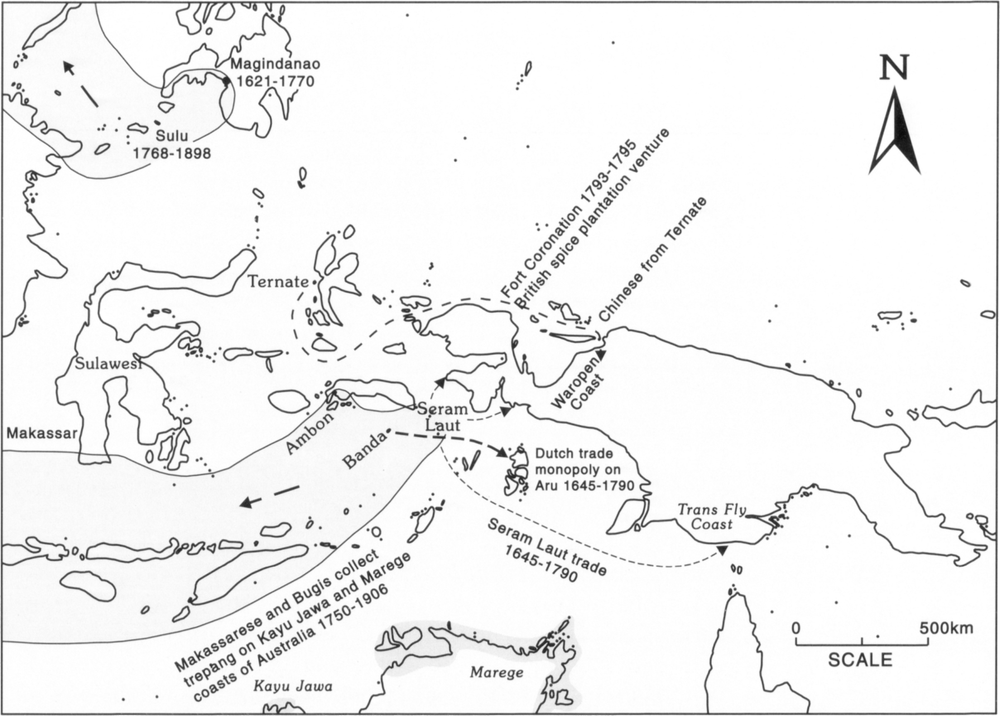

Largely as a consequence of the trade disruptions brought about by the Dutch, the Seram Laut Islands emerged as the new trade centre in outer Southeast Asia (Figure 60). They collected massoy from the Onin and Kowiai coasts, as well as damar from the Trans Fly coast from 276about 1645 until 1790. A similar forest trade developed at Magindanao on Mindanao from 1621 to 1770.10

Following the spice price collapse, the prices for aromatic barks and woods also began to decline. By about 1670 the price for massoy had fallen11 and by the eighteenth century the sandalwood trade was in decline.12 The era of forest products was at a close. Changing needs, tastes and industry were impacting on world and regional trade. In the western world new products were in demand. These included coffee, tea, sugar and tobacco, as well as minerals, in particular tin. In Southeast Asia the growing of coffee, sugar and tobacco became centred on Java, the northern Philippines and the shores of the Straits of Melaka.13 Outer Southeast Asia no longer attracted European investment capital as its spices were produced now more cheaply elsewhere. By 1770 the Dutch East India Company faced bankruptcy.

Figure 60: Following the regional trade disruptions brought about by the Dutch the Seram Laut Islands emerged as the new trade centre in far eastern Indonesia from 1621 until after 1814.

The third cycle: marine products for China

At much the same time as the world prices for spices fell, another major change occurred which had repercussions for outer Southeast Asia. This concerned events in China. In the 1640s China was thrown into turmoil by the Manchu invasion of the southern Ming-controlled provinces. As a result of this struggle coastal towns were devastated 277and trade disrupted for more than 40 years. When the Manchu (Ch’ing/Qing dynasty) gained control of southern China in 1684, ports were reopened and trading links with Southeast Asia reestablished. The Chinese found that they needed new trade goods, as many of the commodities they had freely obtained forty years previously were now subject to European monopolies. They began to concentrate on marine and jungle goods, such as mother-of-pearl, bird’s nests and trepang, which were easy to acquire in outer Southeast Asia as no one else used them. In this way China became the main market for goods from this region from the late seventeenth century.

The demand for these new products in China encouraged a great diaspora of Makassarese and Bugis throughout the archipelago in the late seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries. Campaigns by the ruler of the Bugis state of Bone, who was a strong ally of the Dutch, against Gowa and other neighbouring states also encouraged many Makassarese and Bugis to leave Sulawesi. They founded new settlements and trading centres throughout the archipelago at the same time as the Chinese expanded their trade there.

China’s tea exports also had an impact on outer Southeast Asia. This beverage had replaced ale as the national drink in England and was in high demand. Until alternative goods acceptable to the Chinese were found, tea had to be obtained in exchange for silver. In 1740 British traders realised that by trading Indian goods, such as cotton, for marine and jungle products from outer Southeast Asia, they obtained trade goods which allowed them to acquire the tea they sought in China. British traders thus began to seek mother-of-pearl, edible bird’s nest and trepang for this expanding trade. For example, the export of mother-of-pearl from Sulu increased from some 121 tons in 1760 to some 726 tons in 1835.14

The interchange of trade goods between India, outer Southeast Asia and China led to the need for a major entrepôt for this trade. The obvious location was somewhere in the western Indonesian archipelago. Riau, established by the Bugis, nearly became such a centre, but was destroyed by the Dutch in 1784; the harbour fees at Melaka were too expensive; and Penang was too far north. In 1819 the British founded Singapore on the edge of Dutch territory.

A number of trade centres developed to supply marine products to China (Figure 60). Sulu became such a centre and a regional power from 1768 until 1898.15 Makassar was another centre. From about 1720 to 1906 Makassarese (Macassans) went trepang collecting on the north coast of Australia.16 In the vicinity of New Guinea, the Seram Laut Islands and subsequently Dobo in the Aru Islands developed into important trade centres.278

The trepang collectors who visited Australia were mainly Makassarese and Bugis. They sailed to northern Australia on prau which tended to be owned by Chinese merchants in Makassar. Their voyages utilised the northwest monsoon on their outward leg to Australia and the southeast trade winds on their return to Makassar. Each leg took about ten days. They collected trepang from two stretches of coastline. The main area they visited they called Marege. This extended from Bathurst Island in the west to the Wellesley Islands in the east. The second area was the Kimberley coast, which they called Kayu Jawa. In 1803 Matthew Flinders learnt that there were some 60 praus crewed by over a thousand men working in the Marege area.17

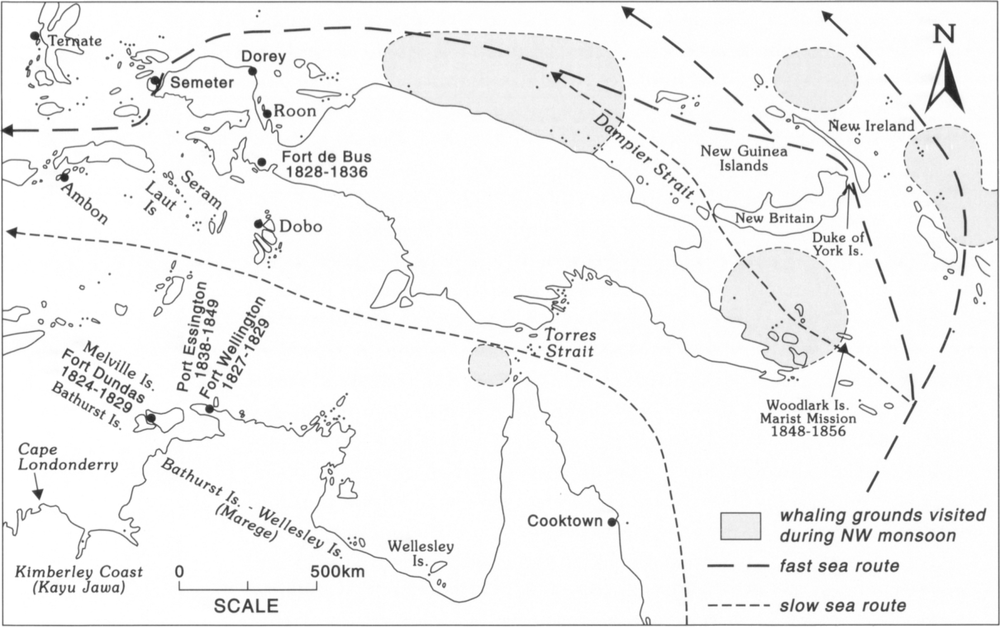

The annual visits by Makassarese to collect trepang on the north coast of Australia led some British investors to propose that a similar entrepôt to Singapore could be established in northern Australia to serve outer Southeast Asia. Both the Dutch and the British recognised that a successful entrepôt in the region would be a profitable venture. It would allow them to despatch large quantities of local products to foreign markets and to sell their own products to the producers. With this intention in mind, the British founded a number of settlements on the north coast of Australia, these were Fort Dundas in 1824–29 on Melville Island, Fort Wellington in 1827–29 at Raffles Bay and Port Essington in 1838–49 (Figure 61). The Dutch countered these attempts by their own settlement at Triton Bay in 1828–1836 and by proclaiming the southwestern coastline of New Guinea from the northern tip of the Bird’s Head to the vicinity of the present international border on the south coast to be under Tidore’s suzerainty. All the British and Dutch settlements were sorry failures. Meanwhile, the Seram Laut Islands flourished as an eastern entrepôt for goods mainly destined for China, as local traders disregarded British and Dutch efforts to control trade in the region. However, like other marine-orientated centres in Southeast Asia, the Seram Laut Islands went into decline in the late 1890s.

The fourth cycle – new European interests: copra, plumes, pearls and minerals

To counter increasing European interest, the Dutch in 1848 extended the area of New Guinea claimed to be under the control of the Sultan of Tidore to the vicinity of the current international border on the north coast of New Guinea. By 1850 traders from Ternate and Tidore were starting to trade on the Bird’s Head and north coast of New Guinea, whereas Seram Laut and Bugis traders were more active in the Raja Empat Islands and south coast of New Guinea (Figure 61). In practice Tidore had no real influence in Dutch New Guinea and the Dutch 279increasingly assumed direct rule of the region. By the 1890s a trading post was operating in Humboldt Bay and government stations were established at Manokwari, Fakfak and Selerika. The latter was unsuccessful and was replaced by Merauke in 1902. In 1905 the legal fiction of Tidore’s rule ceased when the Sultanate of Tidore lost its independence and was for the most part incorporated within the Dutch colonial state.

The resources of eastern New Guinea became known in Europe and Australia as a result of observations made by whalers and travellers using shipping routes that passed through the area (Figure 61). This led to interest in the New Guinea Islands, especially New Ireland and the Duke of York Islands as these lay on the fast ship routes from eastern Australia to Asia and Europe. These fast routes passed either north or south of New Ireland. Slower, smaller vessels took the rougher Dampier Strait, whereas Torres Strait was generally avoided until reliable maps were available to navigators after the reef surveys of Captain Blackwood in 1842–46 and Captain Owen Stanley in 1848– 49.18 In 1847 the Marists established the first mission in what is now Papua New Guinea on Woodlark Island on the basis of advice from the captain of a whaler.19

Figure 61: Whaling grounds as well as trade centres and sea routes from 1814-1850.

280The increased attention paid to eastern New Guinea was part of a general European interest in undeveloped areas. For instance, the Northern Territory was annexed by South Australia in 1863 on the basis of plans for pastoral development and dreams of mineral discoveries. This affected the eastern Indonesian trepang collectors as the South Australian government soon introduced licences and customs duty on food and other items they used. This reduced the profit margins of a declining industry and by 1902 fewer and fewer Indonesians were coming in search of trepang. The industry ceased when the South Australian government prohibited the entry of Indonesian trepang collectors into Australia in 1906.20

The marine resources of Torres Strait and its increasing importance for navigation attracted investors and settlers. Trepang collecting began in Torres Strait in the 1830s, a few years after the first exports from the Queensland coast in 1827.21 In 1862 the Governor of Queensland established a coaling and refuge station on Somerset Island in Torres Strait. Pearling began in the Strait in the 1860s. By 1870 the London Missionary Society had established a base there. In 1878 the Torres Strait Islands were annexed by Queensland and a government post was established on Thursday Island.

The Duke of York Islands and nearby areas had become known to the outside world as a result of being on a major sea passage. In the 1870s copra traders became active in the Duke of Yorks and nearby areas. The Hernsheim brothers and Queen Emma were pioneers in this trade. The large number of established coconut palms in the villages of New Britain and New Ireland allowed copra trading, which in turn provided the capital to establish large plantations. This was how Rabaul quickly became the financial capital and in due course the administrative capital of German New Guinea.

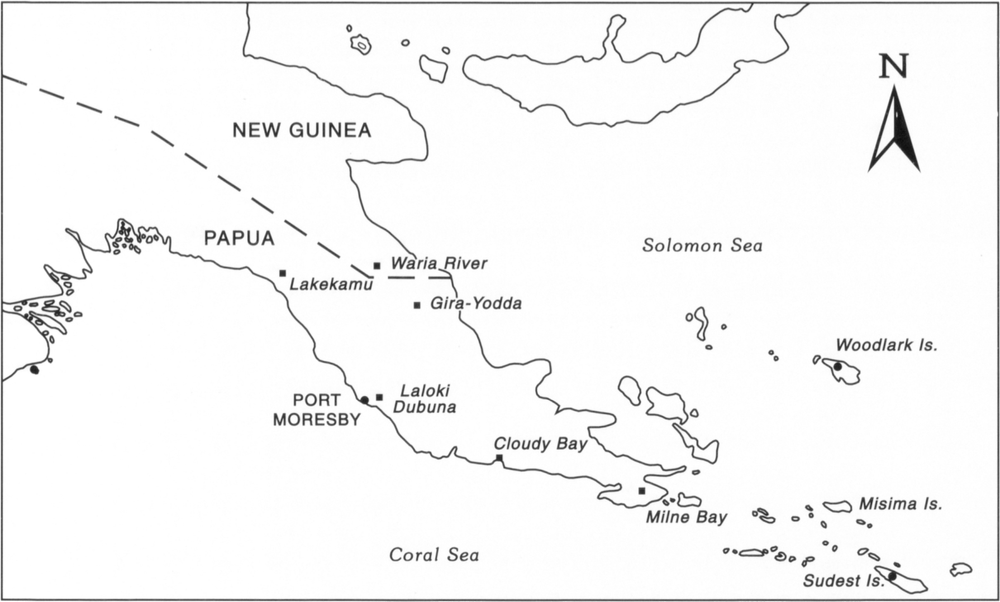

By the 1870s businessmen in both Australia and Germany believed that New Guinea was a profitable area for investment. By 1884 both the British and German governments were persuaded to annex parts of eastern New Guinea, and the border which established the extent of their claims was agreed on in 1885. The main income earners in German New Guinea prior to World War I were copra in the Islands and bird of paradise skins in Kaiser Wilhelmsland. The economy of the north coast of Dutch New Guinea was also dependent on plume hunting.22 After the war copra was the main income earner in what then became the Mandated Territory of New Guinea. In Papua mining, mainly of gold but some copper, became the main economic pursuit. A large number of projects were established before 1920 (Figure 62). They were Sudest Island (1888–98), Misima Island (1889–1942), Woodlark Island (1895–1920), Gira River (1899–1910), Yodda River (1899–1910), 281Milne Bay (1899–1909), Cloudy Bay (1901–07), Waria River (1906–09), upper Lakekamu (1909–20) and the Astrolabe Mineral Field at Laloki and Dubuna (1910–26).23

Figure 62: Mining ventures established in Papua and New Guinea prior to 1920. (Also showing colonial divisions).

On the periphery of the Spice Islands

The success and wealth of the Spice Islands had an impact on western New Guinea, as many of the innovations and goods brought to these islands were also introduced to western New Guinea. These introductions included sociopolitical practices such as bestowing titles and paying tribute; a new religion, as some New Guineans were converted to Islam; a new language, as some New Guineans learnt trade Malay; new crops such as rice, sweet potatoes and tobacco; and new products such as metal tools, cloth, fine porcelain and metal gongs.

The early role of Melaka as the major trading centre for the Indonesian archipelago had led to the rapid spread of Malay and Islam. By the fifteenth century Malay was the dominant trade language in the Indonesian archipelago. The inhabitants of the Javanese seaports had been converted by proselytizers from Melaka and the Javanese in turn carried the faith to the Spice Islands.24 When the Portuguese arrived there, they found that the coastal merchants, probably Javanese and 282Malays, were practising Moslems and that this had been the case for the last 50 to 80 years. Proselytizers from the Moluccas later introduced their faith to western New Guinea. For instance, a Moslem missionary was observed at Triton Bay in 1826.25

In 1528 the Spaniard Alvaro Saavedra Ceron found that the people on an island called Harney in western New Guinea were already acquainted with iron tools.26 Once familiar with metal tools, some New Guineans learnt how to forge them. In 1606 Captain Don Diego de Prado y Tovar observed New Guineans using a bellows to work harpoons and other iron implements in Triton Bay.27 By the beginning of the nineteenth century New Guinean smiths were established at Dorey in Cendrawasih Bay, as well as at Triton Bay and most likely Berau Bay. The work of these smiths was limited to the forging or reforging of imported iron using bamboo bellows (Figure 24).28 European visitors found that iron bars were highly desired trade goods and used them in payment for goods and services. For instance, Thomas Forrest paid Captain (kapitan) Mareca from Tomoguy Island off the west coast of Waigeo, whom he had employed as a translator on his trip to New Guinea in 1775, with iron bars.29 Beccari and D’Albertis in 1872 also used iron bars to pay for the hire of a prau to travel from Cendrawasih Bay to Sorong.30

In areas receiving a constant supply of these goods, such as the Bird’s Head, metal tools and cloth quickly superceded stone tools and tapa cloth. They also replaced these items in traditional trade and exchange networks.31 The possession and display of these new artifacts, like the bronze artifacts before them, indicated their owner’s ascendancy within his community.

Supplies of rice were imported by the Spice Islands from Java to feed the ruling elite. The high prices paid for rice32 probably encouraged its local production. Rice is reported to have been grown on Motir (Moti) Island at the beginning of the sixteenth century.33 It was being grown on Gebe in 1849.34 In the 1850s Alfred Russel Wallace observed rice being grown on Halmahera at Galela and Gilolo, Kaioa Island and Bacan off the west coast of Halmahera, as well as Dorey in New Guinea.35 By the late nineteenth century rice was a prestige food.36 Although infrequent in daily meals, upland rice has become the most desired food and is a feast food at Galela on Halmahera.37

The Portuguese introduced the sweet potato, tobacco and other crops from South America to the Spice Islands, from where they were introduced to other parts of outer Southeast Asia. As described in Chapter 9, the Seram Laut contact with the Trans Fly coast from 1645–1790 probably led eventually to the introduction of the sweet potato into the highlands of what is now Papua New Guinea. The sweet potato 283had a revolutionary impact on life in the New Guinea highlands, as its high yields from poor and cold soils allowed more people to live in this region than ever before. Both the sweet potato and tobacco were quickly adopted in many parts of New Guinea.

There was also an impact on the local flora and fauna. For example, early records indicate that the massoy trade was not sustainable and had a serious impact on the local flora (see Chapter 8). The extent to which massoy trees have recovered in the heavily exploited areas of western New Guinea is not known. Fears about the overfishing of trepang in northern Australia led to the closure of an area of the Cobourg Peninsula from Cape Don to De Courcy Head from 1903–5.38 Although there were fears of extermination, the European bird of paradise trade, which declined in the 1920s, did not have a long term impact on the local fauna of New Guinea. Today diminishing habitats and the widespread use of guns are having an impact and the survival of some species is threatened.39

Conclusion

Initially the goods obtained by specialist traders from New Guinea and nearby islands were only known to the rich and powerful of Asia and the Middle East. They subsequently became known in Europe and other parts of the world. All the goods obtained by specialist traders went through boom and bust cycles. For forest resources this is demonstrated by the trade histories of products such as plumes, spices, aromatic barks and damar and for marine resources by trepang and pearls. Today’s commercial crops, as well as minerals and oil, are also not immune to these cycles, nor are the main forest and marine products harvested today, namely timber, mackeral, tuna and prawns. The latter range of products are very different from those sought in the 1920s, and this difference raises the question as to what will be the main natural resources of New Guinea in another 70 years time. For instance, will the rich biodiversity of this island region be providing marine or forest products for food, medication or other purposes of which today we can only dream? Or will tourists be paying large sums just to have the pleasure of ballooning over or walking through some of the world’s few remaining natural wilderness areas? Time will tell.

Notes

1. Holleman 1925 cited by Ellen 1987: 51.

2. Dalton 1977 cited in Higham 1989: 186.

2843. Soejono 1963

4. Likewise during the period of European contact in New Guinea, trade goods and knowledge of Europeans travelled far in advance of their actual presence (May 1989: 130).

5. For example Bulmer and Tomasetti 1970: Golson 1972.

6. For example Badner 1972.

7. Galis 1953–4: 19; Kamma 1972: 217; Roe 1966; See also Chapter 6.

8. Schrieke 1955; Meilink-Roelofsz 1962.

9. Chaudhuri 1965: 169.

10. Laarhoven 1990.

11. Galis 1953–4: 14.

12. Glover 1986: 11.

13. Steinberg 1985.

14. Urry n.d.; Warren 1990: 197.

15. Laarhoven 1990; Warren 1990.

16. Macknight 1986.

17. Macknight 1976: 27–9; Mulvaney 1989: 22–3.

18. Whittaker et al 1975: 314–16.

19. Nelson 1976: 50.

20. Macknight 1976.

21. Macknight 1976: 40.

22. Wichmann 1917: 389.

23. McKillop 1974; Nelson 1976; Waiko 1993.

24. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 34.

25. Earl 1853: 55.

26. Galis 1953–4: 8.

27. Stevens and Barwick 1930.

28. Kamma and Kooijman 1973.

29. Forrest 1969: 55, 88.

30. Goode 1977: 47.

31. Elmberg 1968.

32. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 287.

33. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 352, footnote 73.

34. Kops 1852: 306.

35. Wallace 1986: 323, 331, 348. 498.

36. de Clercq 1890 cited by Ellen 1979: 61.

37. Ishige 1980: 334–40.

38. Macknight 1976: 122.

39. Kwapena 1985: 154–5; Peckover 1978. Beehler (1993: 119) lists the most threatened birds of paradise as the Black Sicklebill, the Blue Bird of Paradise and the Macgregor’s Bird of Paradise. Navu Kwapena (personal communication 1994) also considers that the King of Saxony Bird of Paradise should be added to this list.