7

Collecting and trading in

the Raja Empat Islands,

the Bird’s Head and Cendrawasih Bay

Collecting and trading in the Raja Empat Islands

Introduction

The part played by the people of the Bird’s Head and the Raja Empat Islands in the Asian plume trade is covered in Chapter 3. This chapter covers early European acquisitions of bird of paradise skins as well as their subsequent interest in acquiring natural history specimens and plumes for the millinery trade. It also reports on the activities of Chinese and other traders supplying Chinese markets.

Bird of paradise skins

Local leaders in the Moluccas and New Guinea presented preserved birds of paradise to important people. The first Europeans to reach the Spice Islands in 1522 received gifts of Lesser Bird of Paradise from the Sultan of Bacan. This practice was to continue. For instance, in 1775 Thomas Forrest was given birds of paradise by three Papuan headmen, when they came out to his vessel off the Aiou (Ayu) islands northeast of Waigeo. Forrest was told that these particular skins had been obtained from the mainland of New Guinea.1 Europeans in return began to offer trade goods for bird of paradise skins; see Figure 24. As the number of European visitors increased and their natural history and millinery interests and demands grew, more became known about the best places to acquire the skins of birds of paradise.

G.E. Rumphius, the Dutch scholar who lived on Ambon from 1653 until his death in 1702, records the sources of the trade skins he obtained on Ambon in the seventeenth century. He was told that the Greater Bird of Paradise came from the Aru Islands, the Lesser from Misool and Salawati, the King from the Papuan and Aru Islands, the Glossy-mantled Manucode from Misool, the Arfak Astrapia from Sergile (the Sorong area of the Bird’s Head), the Black Sicklebill from Sergile and the rare Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise from the Papuan Islands and possibly Sergile.2 He also learnt that the plumes were traded for small metal axes and poor quality cloth.

122In view of what we now know about the distribution of these species, Salawati was clearly a trade centre for the Lesser Bird of Paradise, presumably obtained from the mainland; likewise the Sorong area was a trade centre for the Arfak Astrapia and Black Sicklebill which are only found in the Arfak Mountains and in the Arfak and Tamrau Mountains respectively. Rumphius also reports that he acquired the Glossy-mantled Manucode and the rare Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise through Tidore, which suggests that these plumes were in demand there at this time.

When the French naturalist Pierre Sonnerat was on Gebe Island in 1772 he was presented with skins of the Western Parotia and Crinkle-collared Manucode by the Raja of Salawati and the Raja of Patani, an east coast Halmahera village. We now know that the Western Parotia skin would have come from the Tamrau Range of the Bird’s Head.3

Chinese, Ternatian and other traders

In 1775 Chinese traders from Ternate, Tidore and Ambon were the only traders allowed by the Dutch East India Company to trade on the north coast of New Guinea, as they could be trusted not to trade in nutmegs. These traders wore Dutch colours and had passes issued by the Sultan of Tidore. This trade restriction was not lifted until the Dutch East India Company was disbanded in 1799.

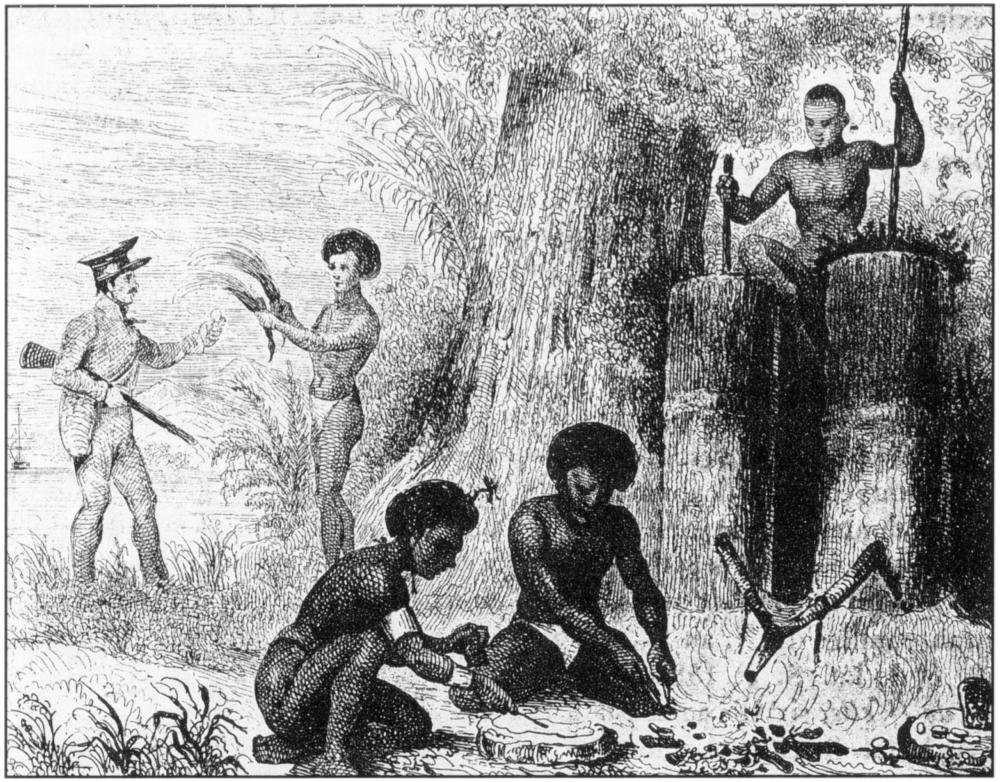

Figure 24: This scene of Doreri Bay in 1827 shows two activities. In the background a man is trading bird of paradise skins with a Frenchman. In the foreground two men are forging metal tools whilst another operates the bellows.

Source: Dumont d’Urville 1834 drawn by M. de Sainson.

123The Chinese sought massoy obtained from Warapine (Waropen) on the east coast of Cendrawasih Bay. This massoy bark was not a coastal product but came from inland forests. Inland groups harvested the massoy bark and traded it to the coastal Waropen4 for metal implements and cloth. In 1775 one picul (60.5 kilograms) of massoy was worth 30 dollars in Java. The Chinese also traded in slaves, ambergris, trepang, turtle shell, pearls, black and red lories and birds of paradise. In return they provided iron tools, chopping knives, axes, blue and red cloth, beads, plates and bowls.5 This trade probably led to Kurudu Island at the eastern end of Japen becoming an important trading centre.

The presence of Chinese ceramics in the Kumamba Islands (Figure 42) in 16166 suggests that Chinese traders have a long history of trade on the coastline extending from Waropen to the Kumamba Islands. This is not surprising as Chinese porcelain dating to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries has been found in Sulawesi and the Talaud Islands,7 and some from the fifteenth century in Berau Bay in West New Guinea (see Chapter 8).

By the 1840s the Chinese operating in the Bird’s Head and Cendrawasih Bay area had been joined by other traders. These included traders from Ternate, especially the employees of Renesse van Duivenboden, and some Bugis from Makassar. Only one European was involved. He was Captain Deighton, an Englishman, who was a longterm resident of the Moluccas.

Ternatian traders made annual visits by schooner to the shores of Berau and Bintuni Bays. This region produced large quantities of wild nutmegs. They usually returned with a full cargo of nutmegs, but this was not achieved without risk. In the late 1850s traders were still attacked on this coast.

Trading centres

In the 1850s Samati (Semeter), the largest village on Salawati Island, was the main trading centre at the western tip of the Bird’s Head (Figures 22 and 25). A Bugis trader was in permanent residence there. Traders were attracted not only by the rich turtle, pearl shell and trepang resources of the surrounding and nearby shores, but also by the great number and variety of birds of paradise to be obtained from the Cendrawasih Peninsula. Most of the trading praus and schooners which visited the western tip of New Guinea called at Salawati. Salawati villagers also supplied neighbouring groups with sago.

Few traders visited Waigeo which was sparsely populated. Waigeo villagers took their sago and pearl shell to trading centres on Salawati or Tidore. However they did provision some whaling crews and ships en 124route to China. When A.R. Wallace was passing through the passage between Waigeo and Batanta in March 1858, several canoes came out from both islands bringing produce for sale. They had some common shells, palm-leaf mats, coconuts and pumpkins. Wallace found them too extravagant in their demands. They were clearly accustomed to selling their trifles to the crews of whalers and China-bound ships. In Wallace’s view these crews lacked discrimination and purchased items at ten times their real value.8

Misool did not have an established trading centre, but each year a number of Gorong and Seram Laut praus came to load sago, which they took to Ternate. It was also rich in massoy bark, trepang, turtle shell, pearls and birds of paradise. As a result of Misool’s past associations with the Spice Islands, its coastal people were all Moslems and were governed by local rajas.

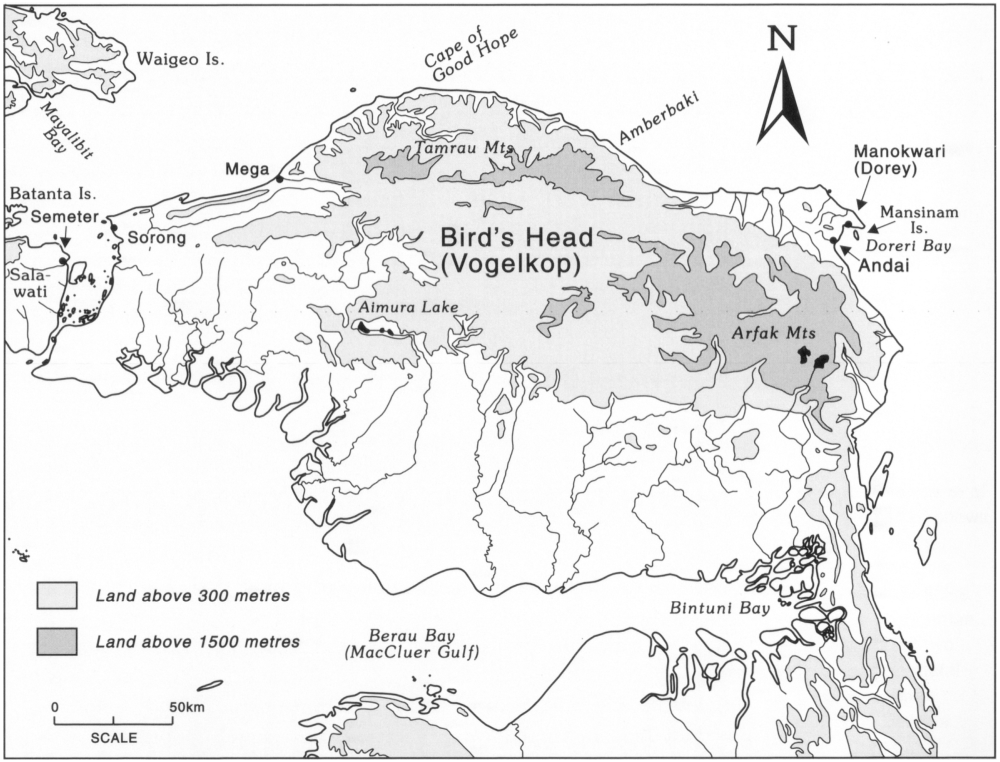

Figure 25: The Bird’s Head.125

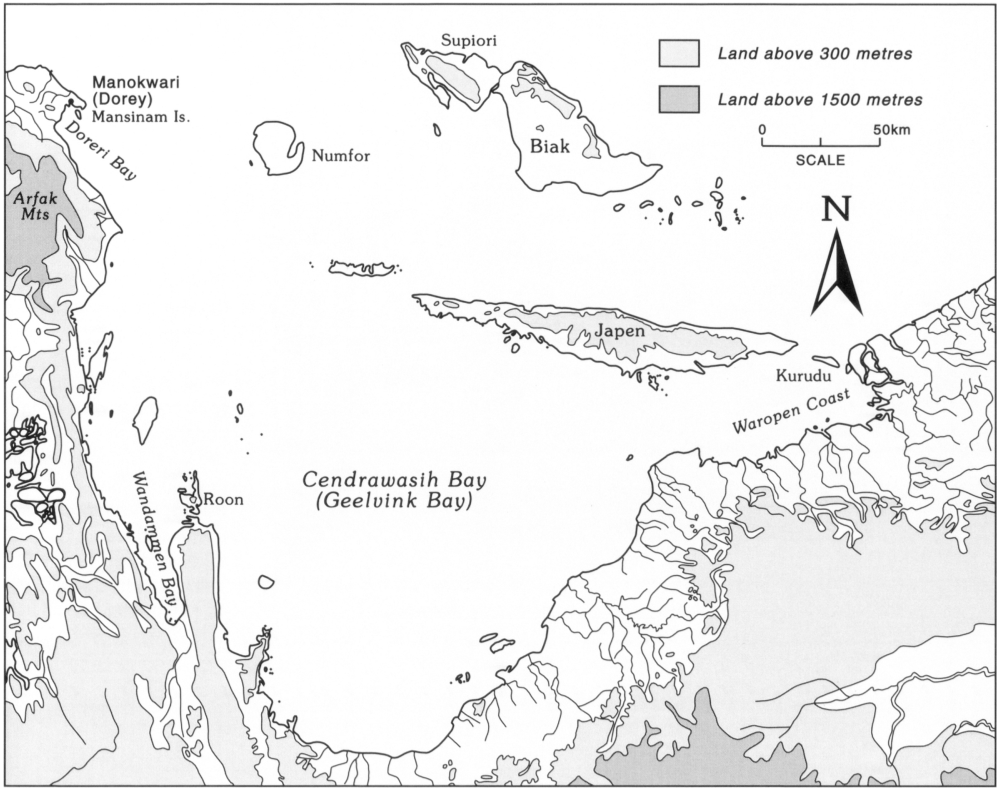

Figure 26: Cendrawasih Bay.

In the 1850s Dorey and Roon Island were the main trading centres in Cendrawasih Bay (Figure 26). Kurudu Island had formerly been an important trade centre, but this ended in the late 1840s when its people suffered repeatedly from hongi raids despatched by the Sultan of Tidore.9

By the 1850s Dorey10 had developed into a trading centre, but Wallace11 found its inhabitants too concerned with profits for his liking. He claims that they could not be trusted in anything where payment was concerned. They bought turtle shell, bird of paradise skins and goura (crowned pigeon) plumes from the people of Numfor, Supiori, Biak and the west end of Japen. These products were later sold to Ternatian traders when they came to Dorey.

Traders from Dorey made trading expeditions as far west as Salawati. There they exchanged their locally grown rice for sago. At Amberbaki (Figure 25), a village about 160 kilometres west of Dorey, they bought vegetables and bird of paradise skins. In addition to their coastal trade, Dorey villagers also traded with the inland Arfak Mountains people. In exchange for trade beads, knives and cloth they 126obtained rice, yams, bananas and breadfruit, as well as tame cockatoos and lories. The latter were then traded to Ternatian and Tidorese traders.

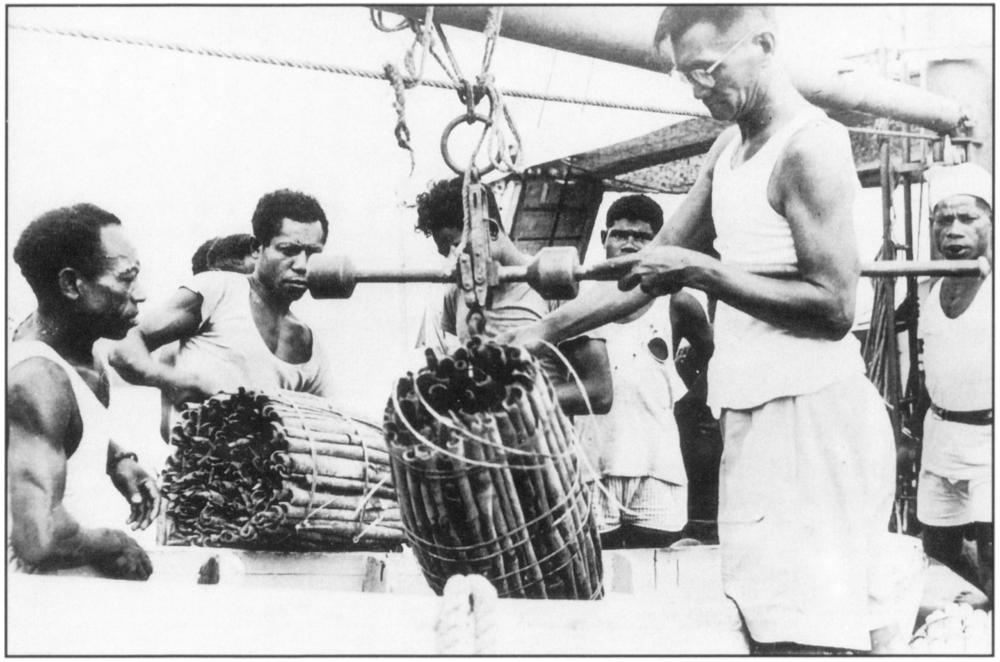

Plate 22: Go Siang Kie, the leading Chinese businessman in Cendrawasih Bay in 1954, weighing massoy bark on board one of the coastal vessels which regularly call at the small ports in the bay.

Photo: Courtesy of Photo Archives Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Captain Deighton began his annual visits to certain villages in Cendrawasih Bay in the 1820s. He was well regarded by the local people as his presence restrained the activities of Tidorese tribute collectors. All the parties concerned knew that he would report any excesses to the Dutch government. Over the years he extended the area he visited. He began visiting Roon Island in the late 1840s. In addition to massoy, Deighton sought other barks, trepang, turtle shell and mother of pearl in return for blue and red calicos, sarongs, brass wire (used to make fishhooks) and other hardware, chopping knives (parang), china cups and basins.12

Ternatian traders also went to Roon Island at the head of Wandammen Bay to load massoy. This small island became the main centre for massoy in the bay and was still active in the 1960s; see Plate 22.

Known sources of trade skins

By the second half of the nineteenth century, three coastal areas became known as the most productive outlets for birds of paradise in New Guinea. These were Sorong and Amberbaki on the Bird’s Head and the area from Tanah Merah to Mount Bougainville on the north coast, see Figures 25 and 42. The latter area became known as Saprop Mani, land of birds.13 As mentioned elsewhere, see Chapters 3 and 11, the 127Bird’s Head and Lake Sentani area are also where most of the early bronzes have been found.

The occupants of these coastal areas obtained bird of paradise skins from inland villages. Birds of paradise, as well as massoy, nutmegs and other products, were traded by inland groups to friendly neighbours who in turn traded them to the coast. In return the inland communities received cloth and iron tools which replaced tapa cloth and stone tools. The cloth (kain timur) was keenly sought by groups in the interior on the Bird’s Head and it became a central component of their ceremonies. This was the case with the Maibrat (Mejprat) people in the vicinity of Aimura Lake (Figure 25).14

Amberbaki was not only visited by Ternatian and Bugis traders, but also, as mentioned above, by Dorey villagers who travelled some 160 kilometres along the coast to trade there for plumes.

Sorong was where the people of Muka village on Waigeo went to obtain the bird of paradise skins they had to pay as tribute to the Sultan of Tidore. This was done by obtaining goods on credit from the Seram Laut or Bugis traders on Salawati. Then during the dry season they made a trading voyage to the Bird’s Head. After some hard bargaining with the local people they obtained enough bird skins to pay their tribute as well as make a small profit for themselves.15

Seeking birds of paradise in their natural habitats

Prior to 1850, most traders and collectors of bird of paradise skins were happy to acquire them from coastal villagers. This meant that they did not have to deal with reputedly hostile inland tribes. Some natural history collectors such as the Leiden Museum collector H. von Rosenberg continued this practice. In 1860 he stayed with a raja on Waigeo Island at the entrance to Mayalibit Bay whilst he bought skins from the local people.16

In 1855 the plume merchant Duivenboden accompanied Prince Ali from Tidore on an expedition to collect birds of paradise for the feather trade. They walked from Mega village on the coast of the Bird’s Head inland into the northern foothills of the Tamrau Mountains (Figure 25).17

Collecting specimens of birds of paradise was one of the main objectives of Alfred Russel Wallace’s travels in the Aru Islands, Waigeo, New Guinea and the Moluccas from 1856–1860. His assistant, Mr Allen, also visited Misool, but this did not add to the number of species they collected during their expedition. Wallace personally collected fully plumed male specimens of the Greater Bird of Paradise (Paradisaea apoda) and the King (Cicinnurus regius) in the Aru Islands, the Lesser (Paradisaea minor) near Dorey, the Red (Paradisaea rubra) on Waigeo18 128and Wallace’s Standard Wing (Semioptera wallacei) on Bacan. Allen also collected specimens of the Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise (Seleucidis melanoleuca) on Salawati and inland of Sorong.19

Wallace spent over three months in Dorey in 1858 from 11 April to 29 July waiting for the Ternatian schooner owned by Duivenboden to return from trading in Cendrawasih Bay. He went to Dorey because Lesson had been successful in obtaining a number of rare bird of paradise skins there in July 1824. Wallace hoped to find the source of these skins and to obtain birds that could be prepared as scientific specimens. He was surprised to find 34 years later that comparable trade skins were no longer available.20 Wallace only acquired the Lesser, some female King Birds of Paradise and a young male Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise, whereas he understood Lesson had obtained the Arfak Astrapia, Black Sicklebill, King, Lesser, Magnificent, Superb, Western Parotia and Flame Bowerbird.21 Wallace was unfortunate to be at Dorey when the Prince of Tidore and the Dutch Resident of Banda arrived on board the Dutch surveying steamer the Etna. Like Wallace they sought birds of paradise and other natural history specimens. Men were sent out in every direction, and all the bird skins, insects and animals the Dorey people had to offer were taken to the Etna. Wallace’s trade articles proved to be poor competition for the range of items offered by the Prince, the Dutch Resident and other passengers. He could only watch in frustration whilst an amateur ornithologist on board bought two Arfak Astrapia skins from a Bugis trader.22

Dorey residents told Wallace that if he wanted different kinds of birds of paradise then he should go to Amberbaki on the Bird’s Head, which was famous for the variety of skins one could acquire there. In an attempt to obtain specimens Wallace sent two of his best assistants and ten men from Dorey to Amberbaki for a fortnight. They were well provisioned and were instructed to buy and shoot whatever they saw. To Wallace’s dismay they returned empty handed. The only skins available for purchase were common Lesser Birds of Paradise and the only species seen in the surrounding forest was one King Bird of Paradise.

His assistants were told that the variety of bird of paradise trade skins that had made Amberbaki famous were currently out of supply. They learnt that the birds were not shot in the coastal forests, but were obtained from mountain forests two or three days’ walk inland over several mountain ridges. The Amberbaki people did not acquire the skins directly from the mountaineers, but from villagers living in the foothills. This meant that by the time a skin reached the coast it had already passed through two or three hands. The Amberbaki villagers then sold the skins to traders.

Wallace was sorely disappointed when his assistants returned from 129Amberbaki without a single specimen. His stay at Dorey had not been a pleasant one. Not only had he failed to acquire the bird of paradise specimens he sought, but one of his men had died from dysentery. In addition Wallace had suffered from ill health which was exacerbated by inadequate food supplies.23 From subsequent travels in the Raja Empat Islands Wallace learnt that Sorong, Mega and Amberbaki were the main outlets for bird of paradise trade skins on the Bird’s Head. His assistants had already visited Amberbaki without success. Sorong seemed the best location to visit next, as Wallace was told that it only took one day by foot from Sorong to reach where the birds were obtained, whereas it took three days from Mega. The area inland of Mega village was called Maas by the Biaks as this was where maas, the Black Sicklebill, was found. Its plumes were the most highly prized on Biak and were worn as a sign of authority.24 Mr Allen, who had not been with Wallace at Dorey, also independently learnt of Sorong’s reputation as one of the most productive outlets for bird of paradise skins on the Bird’s Head. They decided that Allen should visit Sorong and journey inland to where the birds were hunted. The Dutch Resident at Ternate arranged on their behalf for the Sultan of Tidore to provide a lieutenant and two soldiers to travel with Allen to assist him in this task.

Allen found that obtaining birds of paradise at Sorong was not a simple matter. In 1860 the coastal chiefs had a monopoly on the bird of paradise trade. They obtained the prepared birds cheaply from inland communities, sold most of them to Bugis traders and paid a portion of their plumes each year as tribute to the Sultan of Tidore. The coastal chiefs did not want a European interfering in this trade, especially one who wanted to visit the inland communities who hunted the birds. They were also concerned that the number of rare birds they were acquiring should not come to the Sultan’s notice, as this would cause the Sultan to raise their tribute requirements. The coastal chiefs themselves valued the common yellow Lesser Bird of Paradise. They knew this could be easily obtained at markets in Ternate, Makassar and Singapore. Why a European should go to such trouble to get other species did not make much sense to them.

When Allen arrived in Sorong and explained his intention of travelling inland to seek birds of paradise, the coastal chiefs replied that this was impossible, as no one was willing to guide him on this three to four day journey through swamps and mountains occupied by hostile tribes. Allen, however, insisted and stressed that the Sultan of Tidore expected them to assist him. Reluctantly the coastal chiefs provided him with a boat to take him as far as possible upstream. At the same time, they sent instructions to the inland villages to refuse him food so that he would be forced to return to the coast.

130The coastal men landed Allen and his Tidorese assistants upstream and left them to fend for themselves. Allen asked the Tidorese lieutenant to seek out some guides and carriers. The lieutenant demanded assistance and soon found himself and his soldiers facing angry villagers armed with knives and spears. The situation was saved by Allen who managed to restore the peace by distributing some presents and displaying the knives, hatchets and beads which would be given to those who worked for him.

After travelling through rugged country for a day they came to the villages of the mountain dwellers. Allen stayed there a month. Lacking an interpreter, all communication was by sign-language and barter. Each day some village men accompanied Allen into the forest. He rewarded them with a small present every time they brought him a natural history specimen. The Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise (Seleucidis melanoleuca) was the only bird of paradise shot; it did not add to Wallace’s species collection as Allen had already obtained a specimen of this species on Salawati.

When Allen showed the mountain people drawings of rare birds of paradise they recognised them and indicated that these birds could be obtained another two to three days’ walk further inland. When told about this, Wallace remarked that the Dorey men he had sent to Amberbaki came back with the same story. Rare varieties were always another two to three days’ journey away in rugged country inhabited by hostile tribes.

Wallace found it extraordinary that after five years’ residence in Sulawesi, the Moluccas and New Guinea, he had acquired only half the number of bird of paradise species that Lesson had obtained in a few weeks in Doreri Bay in 1824. Only the common trade species were readily available during Wallace’s visit. He also notes that the Prince of Tidore had to be satisfied with a few common Lesser Birds of Paradise when he visited Amberbaki as no rare species were available. Indeed it was said that none had been obtained there that year, despite the fact that 5–6 species had been procured there in the past.25 Wallace attributed this scarcity of rare species to the instructions the villagers were under to supply rare species to the Sultan of Tidore as tribute. He also thought that coastal villagers were themselves discouraging such trade by refusing to buy rare species from the mountain traders and seeking only the more profitable common species.26 The activities of traders such as Duivenboden and their willingness to pay more for good specimens may also explain the scarcity of rare species during the time of Wallace’s residence in the region.

The plume boom

Less than ten years after Wallace left New Guinea, there was a rapid rise in bird of paradise skin exports; see Table 7.131

Table 7: Value of bird of paradise exports from New Guinea to Ternate 1865–1869.

| Value of bird of paradise exports | ||

| Year | Guilders/florins | £ |

| 1865 | 200 | 17 |

| 1867 | 100 | 8 |

| 1869 | 1,680 | 140 |

Source: Rosenberg 1875 cited by Whittaker et al 1975: 209. Pounds estimated on 1840 rate. (In 1840 a guilder was worth 1 shilling and 8 pence sterling. Translator’s note in Kolff 1840: 34).

From 1875 to 1885 the plume merchant, A.A. Bruijn, sent teams of collectors to the western Papuan Islands and western New Guinea to hunt birds of paradise in their natural habitats for sale as scientific specimens and millinery plumes. His collectors were instructed to make a special effort to locate and obtain unknown species.27

In 1883 W.H. Woelders reports that there are now thirty Ternatian bird hunters operating out of Andai (Figure 25). He also notes that they are paying twelve times the price paid for carriers 10–12 years ago.28

In 1895 Manokwari became a government station. The export figures available for February 1905 (Table 8) indicate that, as in Kaiser Wilhelmsland, bird skins were the main export from the north coast of Dutch New Guinea.

Table 8: Export figures for Manokwari in February 1905

| Florins | £ | |

| Bird skins | 10,000 | 1,000 |

| Damar (4,000 kg) | 7,700 | 770 |

| Massoy bark (5,400 kg) | 1,950 | 195 |

| Copra (6,900 kg) | 950 | 95 |

| Trepang (500 kg) | 185 | 18 |

| Pearl shell (600 kg) | 115 | 12 |

| Total | 20,900 | 2,090 |

Source: Wichmann 1917: 387. Pounds estimated on 1918 rate.

(In 1918, 30–35 guilders or florins was equivalent to 3 pounds sterling. Historical Section of the Foreign Office, London 1920: 27).

132There is no doubt that an astounding number of bird of paradise skins were exported from the Bird’s Head, mainly by Ternatian and Chinese traders, until the Dutch prohibited such trade in this part of Dutch New Guinea in 1924.

Notes

1. Forrest 1969: 83.

2. Stresemann 1954: 274–5.

3. Stresemann 1954: 276.

4. Held 1957: 351.

5. Forrest 1969: 87, 106.

6. Dumont d’Urville 1853 (2) cited by Riesenfeld 1951: 76.

7. Bellwood 1980: 69: Bulbeck 1986–7: 46.

8. Wallace 1986: 497.

9. Kops 1852: 335.

10. Dorey is the collective name of three small adjacent villages (Kouave, Raoudi and Monoukouari/ Manokwari) on the shore of Doreri Bay (Raffray 1878 cited by Whittaker et al 1975: 238).

11. Wallace 1860: 173–4.

12. Kops 1852: 325; Earl 1853: 78–79.

13. Cheesman 1949: 25, 126.

14. By the 1950s the Dutch administration considered the Maibrat preoccupation with obtaining cloth to be detrimental to agricultural development and the establishment of permanent settlements. In 1954 they began abolishing its use by confiscating large quantities (Elmberg 1968: 22).

15. Wallace 1986: 533.

16. Cheesman 1940: 211, 213.

17. Gilliard 1969: 424 citing Mayr and de Schauensee 1939: 101.

18. Whilst on Waigeo, Wallace observed an unusual method of trapping the Red Bird of Paradise by means of a noose. This technique was used only by eight to ten men from Bessir village. The birds were attracted to step into the noose by the red fruit of an Arum (Wallace 1986: 537).

19. Wallace 1986: 574.

20. Wallace 1860:175.

21. Wallace 1862a: 154–5.

22. Wallace 1862a: 155: 1986: 507.

23. Wallace 1862a: 155.

24. Cheesman 1949: 126–7.

25. Wallace 1986: 510.

26. Wallace 1862a: 159.

27. Gilliard 1969: 418, 421

28. Wichmann 1917: 390.