3

The plume trade: the demands of

Asian traders and the first birds

of paradise to reach Europe

The plume trade: the demands of Asian traders

Introduction

Plumes rather than spices appear to be the main product sought by the first specialist Asian traders. When the demand for plumes declined, spices became the most important product. The continued availability of trade plumes during the spice trade cycle attracted European interest. In time this gave rise to a demand for bird of paradise skins by natural history collectors as well as by fashion conscious women during the European plume boom.

Birds of paradise

New Guinea is famous for its variety of spectacular birds. Some eight per cent of the world’s bird species are found there,1 including some of the most beautiful, the birds of paradise (Paradisaeidae). No other group of birds has their diversity and splendour of plumage. Some birds of paradise have seasonal filamentous nuptial plumes which are brightly coloured and open on display into fans of colour (Plates 1 and 4). Others have wire-like accessory plumes that extend from the tail, head, back or shoulders. Many species feature brilliant metallic hues, whilst others are distinctive by their extremely long tail feathers.

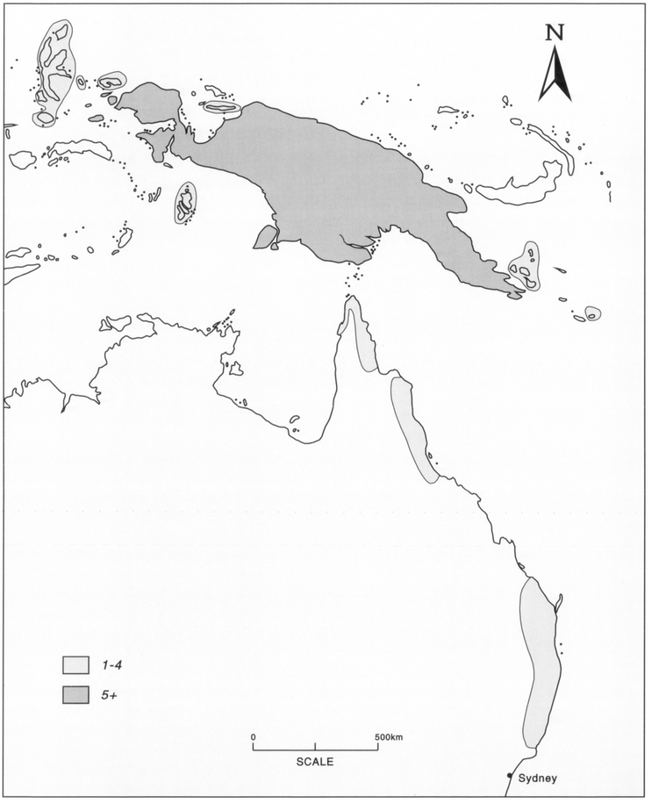

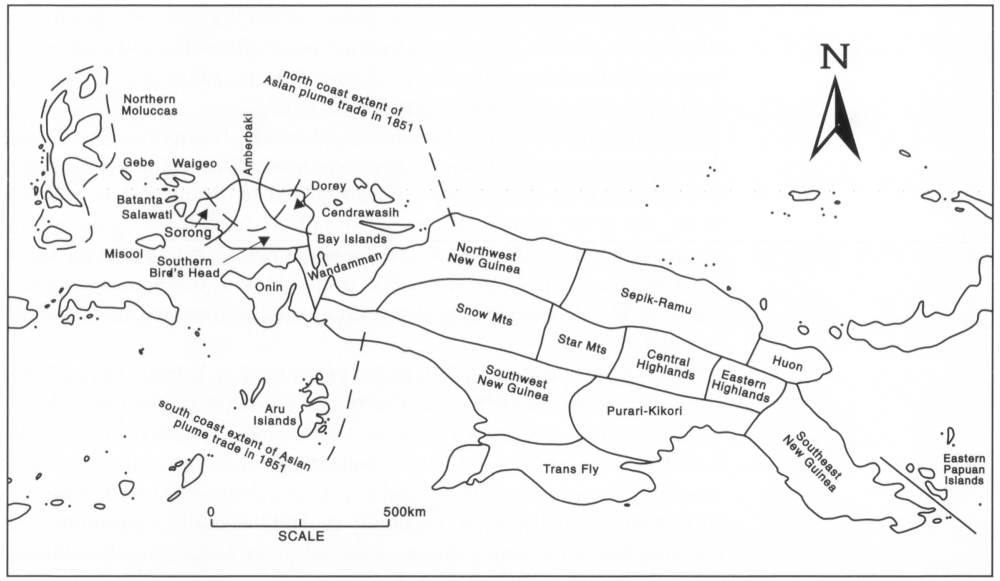

Thirty-eight of the known forty-two species of birds of paradise live in New Guinea and on its offshore islands (Figure 8). Two of these 38 species, the Magnificent Riflebird and Trumpet Manucode, also occur in Australia. Only four species are found beyond New Guinea and its immediate offshore islands. Of these the Paradise and Queen Victoria’s Riflebirds are found in Australia and the Wallace’s Standard Wing and the Paradise or Silky Crow in the Moluccas. Birds of paradise do not occur in the Admiralty Islands, Bismarck Archipelago or the Solomon Islands.

The great English naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace observed that New Guinea had a greater proportion of beautiful birds than the rest of 50the world.2 He was also so impressed by the birds of paradise that he subtitled his account of eight years’ travel in the Malay Archipelago (now Indonesia) from 1854–1862 as travels in the land of the orangutan and the bird of paradise.

Figure 8: The distribution of bird of paradise species.

Source: Based on Cooper and Forshaw 1977.

51The Asian plume trade

Many bird of paradise species have splendid plumes which quickly arouse human admiration and desire. My thesis is that leaders in island communities to the west of New Guinea have long known about these plumes.

Tracking such trade is difficult as plumes do not survive in the ground to be found in archaeological sites. Instead, the story about the plumes trade is initially dependent on the appearance of illustrated plumes/feathers on prehistoric artifacts and then in due course on their mention in historical records.

Some indication as to when the plume trade may have commenced can be based on the appearance of other introductions to Southeast Asia from New Guinea. While substantial trade connections existed in New Guinea by 5,000 years ago, less is known for this period in western Indonesia.

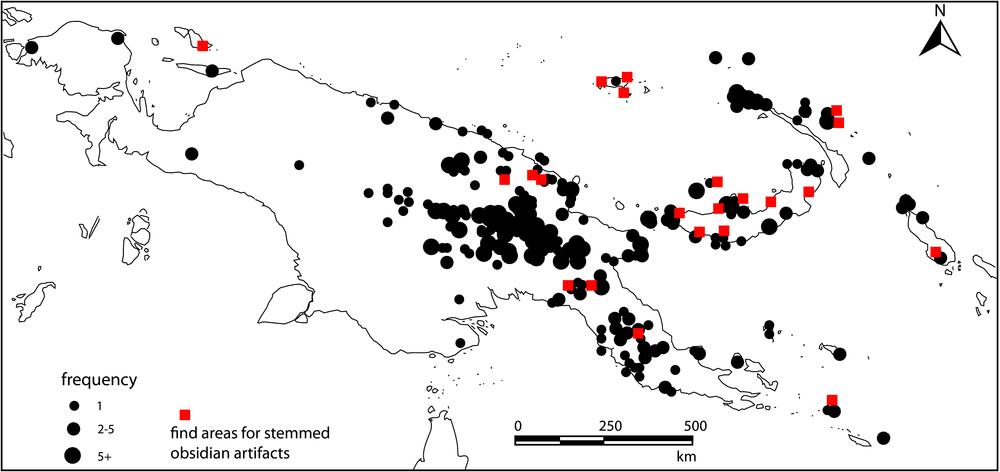

The distribution of certain ceremonial valuables, namely stone mortars and pestles3 and stemmed obsidian artifacts,4 indicates that substantial trade connections existed in New Guinea by 5,000 years ago (Figure 9). The obsidian (volcanic glass) artifacts were made from obsidian sources from Lou Island off southern Manus and on the Willaumez and Hoskins peninsulas of West New Britain.5

Less than 15 mortars and pestles have been found in West Papua, whereas some 2,000 come the region encompassing mainland Papua New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland and the island of Milne Bay. As mortars and pestles are found in areas suitable for taro agriculture it is likely that these artifacts were used to make ceremonial puddings comparable to those made in historical times by some communities in northern Papua New Guinea and offshore islands.6

There are stylistic similarities in the stone mortar and pestle varieties found in the highlands, also on the shores of the former Sepik-Ramu inland sea, the Madang-Morobe coastline and West New Britain. It is unlikely that these stylistic similarities shared between widely spaced regions arose from independent invention. Rather they indicate the presence of extensive exchange networks. These have allowed ideas and products, such as obsidian and crops, to be exchanged by the social contacts that linked these regions.

Figure 9: Distrbution of stone mortars and pestles and stemmed obsidian artefacts in New Guinea and nearby islands.

Sources:52 Based on Swadling database.

It may be significant in terms of an early plume trade that bird pestle and mortar varieties tend to have distributions that link coastal and highlands areas.7 This pattern is repeated again in the historical records on plume hunting when collectors sought exotic species.

The highest density of bird pestles, with wings folded against their body, extends from the East Sepik-Madang coast up into the western part of the central highlands of PNG whereas most bird mortars with wing features occur from the coastal areas of Vitiaz Strait up into the Eastern Highlands. The other pattern is for isolated finds of bird pestles, with raised wings, to occur along river valleys and their tributaries into the highlands; see Figure 56 in Chapter 14 for illustrated examples.

Isolated raised wing finds have been made in the Lae-Wampar area of the Middle Markam River in Morobe Province, Aikora on the upper Gira River in Oro Province and two finds associated with the Fly River in Western Province; one from Wonia in the Trans Fly and the other from Ningerum on an upper tributary of the Fly River. It is hard to explain the sole distribution of these pestles without seeking some explanation that relates to birds and inland access via major river systems.8

The initial domestication of bananas occurred in New Guinea and by about 4,000 years ago they had been dispersed westwards as far as Pakistan. A similar time frame seems the case for sugarcane with its initial domestication in New Guinea and then a subsequent down-the-line westward dispersal to Southeast Asia and beyond.

Other New Guinea products were also being traded westwards. Some of the obsidian (volcanic glass) excavated from 3,000 to 2,000 year old deposits in the Bukit Tengkorak rock shelter in Sabah (Borneo) comes from near Talasea on the Willaumez Peninsula in West New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea,9 a distance of more than 3,000 kilometres.53

There is no doubt that attractive birds and their plumes have long been valued in Asia. The earliest record is of peacocks from the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka being introduced to Greece via Persia and Turkey by 3,000 years ago.10

Chinese chronicles dating from over 2,000 years ago indicate that in China colourful bird feathers, cinnamon and scented woods, ivory, pearls and turtle shell were the main luxury imports.14 As feathers quickly decay in the ground we cannot expect to find direct evidence of their prehistoric use. However, indirect evidence of such use does survive as illustrations on artifacts from this period which have withstood the ravages of time. These artifacts are described in due course below.

The desire to accumulate rare and beautiful possessions in Southeast Asia increased during the period 2,500 to 2,000 years ago as autonomous villages located on the floodplains developed into centralised chiefdoms, and subsequently into small states. This profound change gave rise to an intensification of agriculture and production as well as ceremonial activities. The accumulation of rare and beautiful possessions became not an end in itself, but a means of demonstrating status. The possession of such goods, which were scarce because of the time required to manufacture or obtain them, ensured their owners respect in these new chiefdoms. Rare feathers became symbolic of high status. The best illustrated case of this transition in mainland Southeast Asia is the culture of the Dong Son warrior-aristocrats of North Vietnam. Their artwork has survived on drums and other artifacts and depicts a high use of feathers. Ranking behaviour in Southeast Asia was further encouraged by the increasing population size of settlements and the growing complexity of long-distance trade networks, especially the stimulation of the new products and novel ideas introduced by the expansion of Indian and Chinese civilization.15

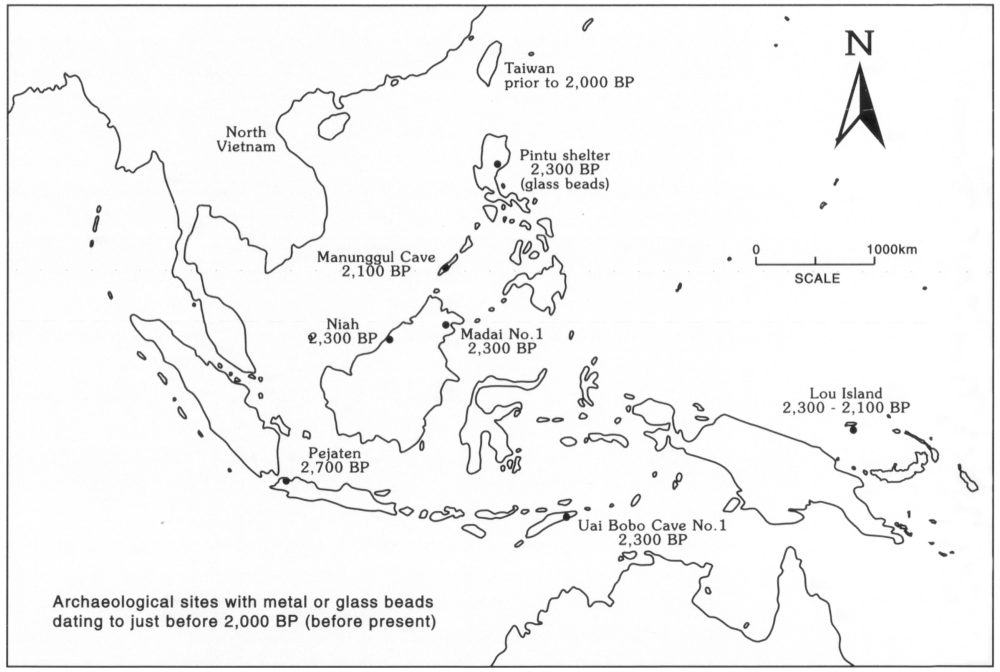

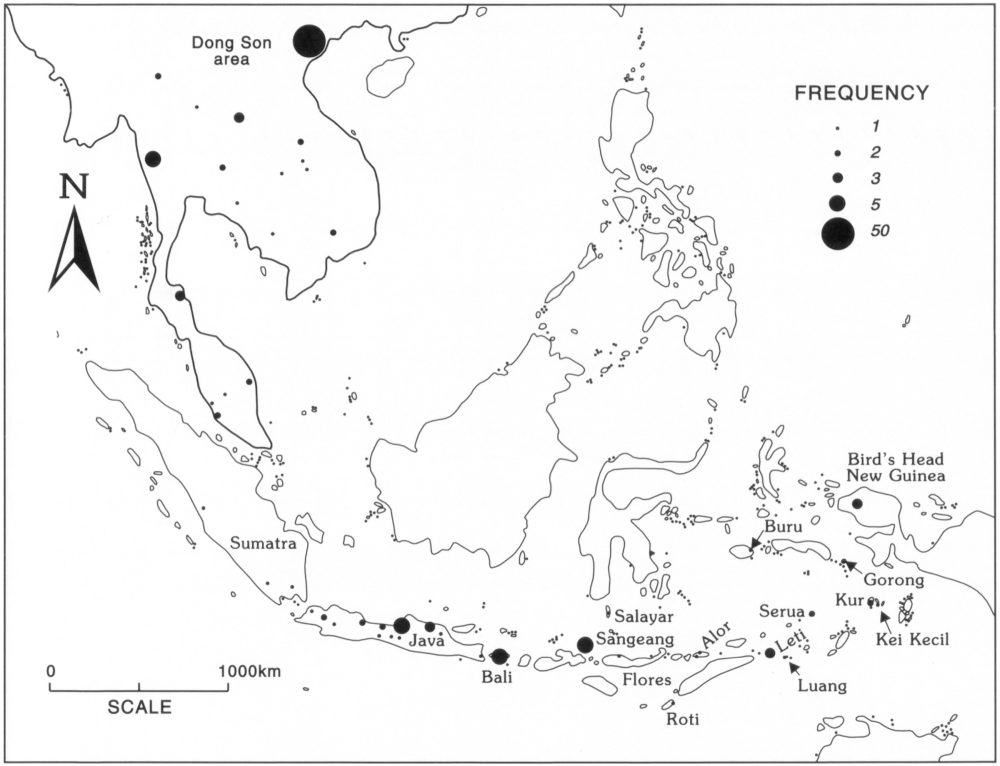

These new developments are also reflected in outer Southeast Asia. Just before 2,000 years ago there was an almost simultaneous 54appearance of metal and glass artefacts (Figure 10) in island Southeast Asia as far as New Guinea. Some bronze artifacts from this period have a specific distribution in this region. These are the Heger type 1 kettle drums and other bronze artifacts with Dong Son motifs. They occur in the island arc extending from Sumatra, Java and the Lesser Sundas to New Guinea (Figure 11). This trade route has a long antiquity and clearly commenced before written records began. It is proposed here that these artifacts were imported by specialist traders seeking feather and other forest products in outer Southeast Asia. The presentation of these exotic bronze valuables to leaders of important local communities would have assisted in establishing alliances ensuring the traders safe passage and assistance in acquiring the products they sought.

Figure 10: There was a simultaneous introduction in archaeological terms of metal and glass beads from Southeast Asia as far as New Guinea just before 2,000 years ago.

Source: Based on Spriggs 1989.

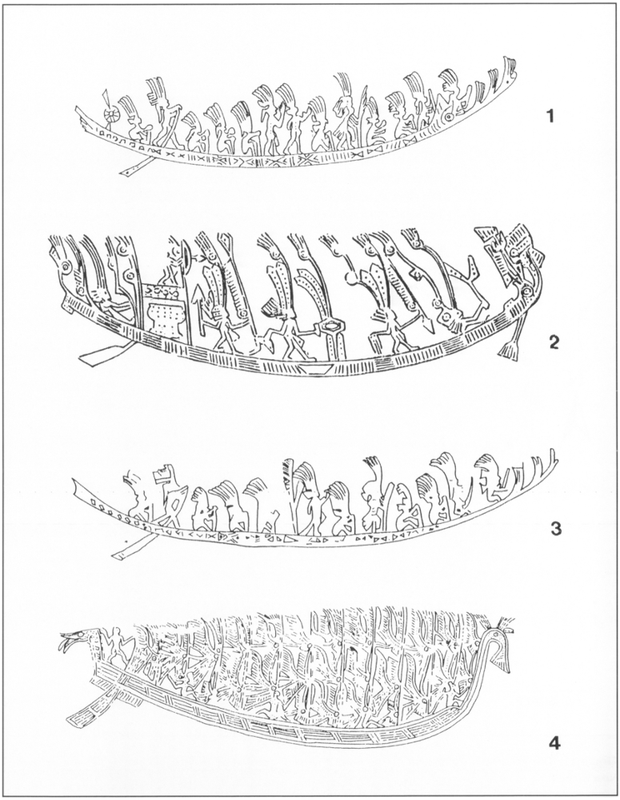

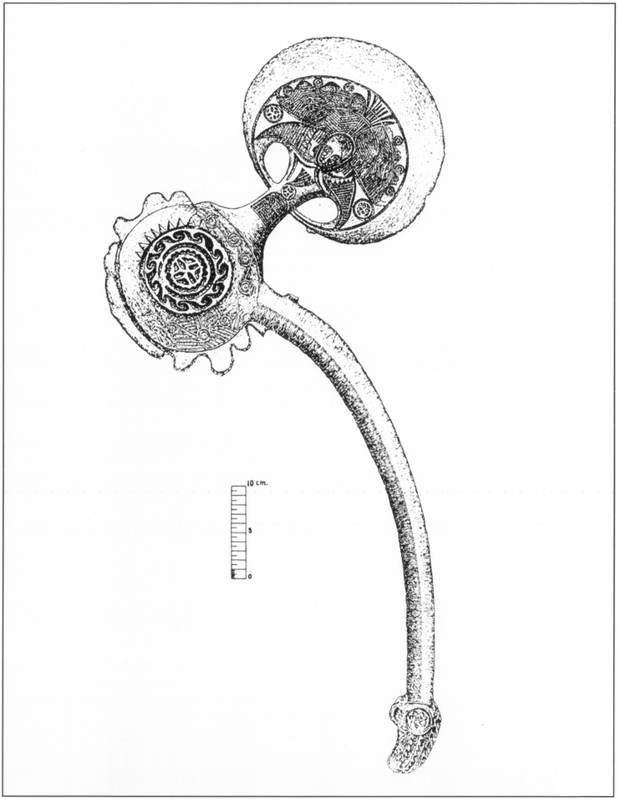

Drawings of people wearing feather headdresses commonly occur on the oldest bronze drums recovered in Southeast Asia, including eastern 55Indonesia. Boats and their occupants are frequently depicted. Most of the warriors and crews of the boats shown on these drums wear feather headdresses (Figure 12). In addition the boats generally have bird-head prows and tail-feather sterns.16 Plumed headdresses also occur on other artifacts. One of the most striking is a ceremonial axe found on Roti Island in eastern Indonesia. The circlets at the perimeter of the headdress shown on this axe could be interpreted to represent the green feathered discs of King Birds of Paradise (Figure 13).

Figure 11: The schematic distribution of early bronze kettle drums (Heger type I) from the Asian mainland to New Guinea.

Source: Based on Bellwood 1978a; Kempers 1988; Spriggs and Miller 1988.

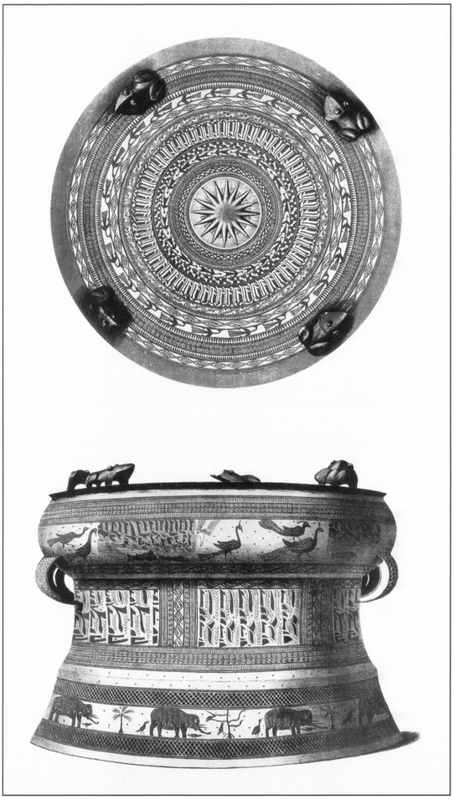

Other decorations on the bronze kettle drums found in outer Southeast Asia indicate that the makers of these drums had links with both China and India. One panel of a drum from Sangeang Island, near Sumbawa east of Bali, shows a raised-floor dwelling with a saddle-roof. 56Inside this building are people who appear to be in costumes worn during the Chinese Han dynasty (221 BC to 220 AD). Another panel of the same drum shows two men in costumes from northwest India; one is sitting astride a horse whilst the other stands in front holding a spear and what may be a mace.17 Two other remarkable drums are clearly imports from the west. The Salayar drum depicts elephants and peacocks (Plate 5), and a Kei Islands drum not only has elephants, but tigers as well. The natural distribution of elephants, tigers and peacocks does not extend to eastern Indonesia.

Figure 12: Feathers dominate the attire of the warriors and crew of boats depicted on Dong Son bronze kettle drums. The boats are also decorated with plumes. These illustrations are from drums from the following locations:

1. Yunnan or northwest Vietnam.

2. Ngoc Lu, Vietnam

3. U’bong, northwest Thailand.

4. Sangeang Island, Sumbawa, eastern Indonesia.

Sources: 1–3 from Goloubew 1929; 4 from van Heekeren 1958.

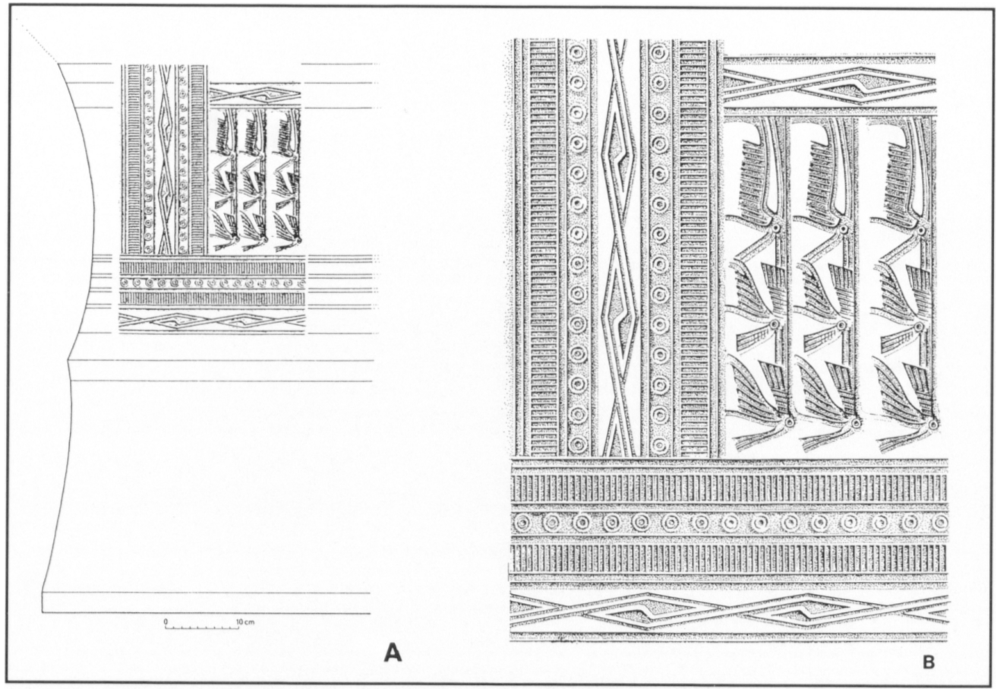

57The bronze kettle drums found in eastern Indonesia date after the first appearance of these artifacts on the Asian mainland. The motifs depicted on eastern Indonesian Heger type I drums are less naturalistic and more stylised than the oldest drums found on the mainland (see Figures 12 and 14). The available information suggests that those found in eastern Indonesia were made in North Vietnam before 250 AD.18

Three large bronze tops from Heger type 1 drums19 have been found near Aimura Lake in the interior of the Bird’s Head of West Papua; see Plate 6. Bronze from one of these drums has been tested. Its composition matches Dong Son alloys rather than later products.20 Further support for such an antiquity for bronze artifacts in New Guinea comes from the dating of a small tabular bronze artifact found in 2,300 to 2,100 year old deposits on Lou Island in the Manus Province of Papua New Guinea.21

The bronze artifacts found in New Guinea with the exception of the small artifact from Manus and one from the Waropen coast of Cendrawasih Bay22 are restricted to the Bird’s Head and Jayapura region. These two areas of western New Guinea have mountainous country where many bird of paradise species are found close to the coast. This is also why the Bird’s Head and Jayapura region became important centres for exporting birds of paradise during the European plume boom.

Some of Bird’s Head and Lake Sentani bronze finds have Dong Son affinities, namely the decorated ceremonial axe from Ase Island in Lake Sentani and the three drum tops from Aimura Lake on the Bird’s Head. Certain finds have parallels elsewhere in Indonesia, whereas others are unique,23 presumably because they have been produced locally by smelting down disused and broken bronze artifacts. Traders may have smelted down their broken implements in order to make replacements or other needed items while waiting for favourable trade winds to allow them to return westwards. In this respect the undated Jembakaki site on Batanta Island, off the Bird’s Head,24 deserves an archaeological investigation to determine the age of the bronze moulds and remnant raw materials found there.58

Figure 13: One of the three ceremonial bronze axes from Roti Island in eastern Indonesia with Dong Son motifs showing a human figure wearing a feather headdress.

Source: Van Heekeren 1958.

59The green, blue and brown glass bracelets found in the burials excavated at Gilimanuk, an early Metal Age site on Bali,25 are very similar to those used as traditional valuables by the people of Biak Island in Cendrawasih Bay, and on the north coast of New Guinea from Lake Sentani to east of Vanimo. Moreover, George Agogino26 reports finding bronze artifacts in association with glass beads in two archaeological sites on the north side of Lake Sentani (see Chapter 11 below).

Metal using did not continue in New Guinea, presumably because contact ceased once the Southeast Asian interest in plumes abated. By 250 AD the demise of the culture of the Dong Son warrior-aristocrats and other related groups was occurring as the Chinese state of Wu expanded southeastwards into their territory. The resulting decline of these groups led to a downturn in the Asian plume trade.

In addition, by about 300 AD Indians had not only introduced Hindu-Buddhist cosmological ideas which linked god, ruler and realm, but also a new range of exotic goods. By adopting this cosmological world view, overlords came to claim divine qualities and began to vie with each other for status, followers and supplies of the exotic goods currently in vogue.27 Forest products such as spices and aromatic barks and woods were now more in demand than plumes.

By 300 AD cloves, nutmegs and sandalwood28 had replaced feathers as the main outer Southeast Asian trade items sought in Asia and the Middle East. Consequently the Spice Islands and the Onin area of the New Guinea mainland became the new centres supplying these markets, as they were respectively the sources of cloves and nutmegs and massoy bark.

As mentioned above spices appear to have been traded to India and the Middle East long before they were in demand in China. Cloves, nutmegs and sandalwood from eastern Indonesia were probably first traded as subsidiary products of the plume trade. When the demand for these products grew they became more important than plumes. Just as there was a change in products sought from eastern Indonesia, there was also a change in the products supplied in return. For instance, large drums were now out of fashion in Asia and were no longer presented to important leaders in eastern Indonesia.

Although the Asian trade in plumes declined, it did not cease. In Southeast Asia feathers continued to be sought as status items. For instance, they were supplied to the Indonesian kingdom of Srivijaya which existed from the seventh to eleventh centuries and controlled the Straits of Melaka. In the eighth century it is recorded that the Maharaja of Srivijaya, Sri Indrawarman, carried bird of paradise plumes to the Chinese Emperor as tribute.29 60

Plate 5: The Salayar drum from eastern Indonesia depicts elephants and peacocks, which do not actually occur there. Height of drum 92 cm.

Photo: Courtesy of Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm.61

Figure 14: Most of the feathers depicted on bronze drums in eastern Indonesia have more stylised versions of feather headdresses than those on the oldest Heger type I drums found on the Asian mainland. Shown here is the Fam drum from the Kei Islands. Part A shows the schematic section of the drum whereas B shows the detail of one of the feather panels.

Source: Spriggs and Miller 1988. Reproduction courtesy of Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association.

Plate 6: One of the bronze drum tops found at Aimura Lake on the Bird’s Head of West Papua. Photo by J.E. Elmberg in article by K.W. Galis (1964).

Source: Reproduction courtesy of Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde.

62The sphere of influence and dominance of trade claimed by the Indonesian kingdom of Majapahit in 1365 is given in an ancient poem, known as the Negarakertagama, dating from that year and written in old Javanese by the poet Prapanca. The islands and areas mentioned in eastern Indonesia include Timur (Timor), Seran (Seram), Wandan (Banda), Ambwan (Ambon), Moloko (Moluccas) and Wwanin (Onin) in western New Guinea.30 At that time it is likely that the massoy producing area of Onin was already a subjected territory of one of the Moluccan sultans, namely the Sultan of Bacan.

Early Portuguese records report that bird of paradise skins were being traded to Persia and Turkey in 1500 AD. The inhabitants of the Kei and Aru Islands in eastern Indonesia brought sago, as well as bird of paradise and parrot skins, to Banda. The bird skins were bartered by the Bandanese for textiles. From Banda they went to Melaka where they were acquired by Bengali merchants, who in turn traded them to Turks and Persians31 who used them to decorate the headdresses of important officials. In 1546 the plumes worn by the Janissaries of the Ottoman Empire, an elite corps of Turkish troops guarding the Sultan, were described by Belon. His description best fits plumes from birds of paradise.32 In 1772 M.P. Sonnerat observed that the Dutch also participated in this trade. He reports that they supplied bird of paradise skins to the rich inhabitants of Persia, Surat (in the Cambay Gulf area of Gujarat, India) and the Indies. In these areas the plumes were used to decorate turbans and helmets as well as horses.33 Beliefs combining the beauty of the birds of paradise with special sacred powers were and remain common in Asia. When the Spaniards reached Tidore in 1521 they learnt that birds of paradise were highly prized by the Moluccans, because the plumes made their men invulnerable and invincible in battle.34

It was probably through the activities of Bengali merchants that bird of paradise plumes first reached Nepal. The flank plumes of the Greater Bird of Paradise are a symbol of royalty in Nepal. They are only worn by the King and his senior officials (Plates 7–9). The supply of Greater Bird of Paradise skins declined when hunting became illegal throughout New Guinea in 1931. This was recognised as a real problem prior to the coronation of King Mahendra of Nepal in 1957. It was overcome when the United States of America made a state gift to Nepal of Greater Bird of Paradise skins which had been confiscated by customs officials and handed over to the American Museum of Natural History.35

On Bali, bird of paradise skins are still used during certain funerary rites. For the Balinese people feathers represent the transformation of the departing soul as a bird and its departure for paradise.36 63

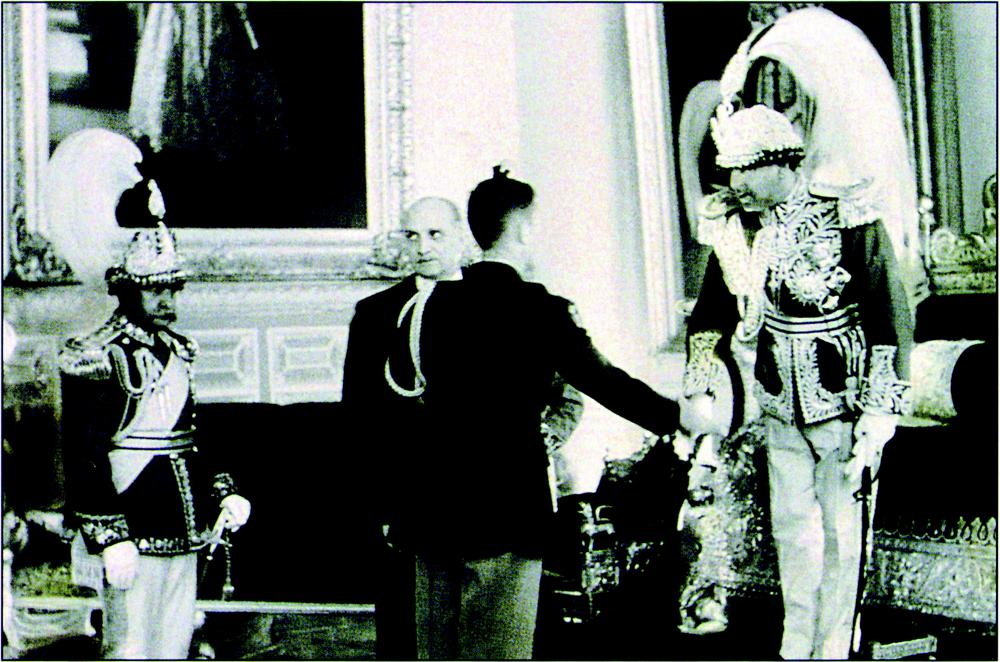

Plate 7: Bird of Paradise plumes were treasured like jewels in Nepal and only worn by the King and his senior officials. Here the American Ambassador is presenting a member of his staff to the King in the late 1940s. Both the King and his Prime Minister wear crowns adorned with the interwoven flank plumes of the Greater Bird of Paradise. These plumes reached Nepal by a long established trade network which only declined when hunting became illegal throughout Dutch New Guinea in 1931.

Plate 7

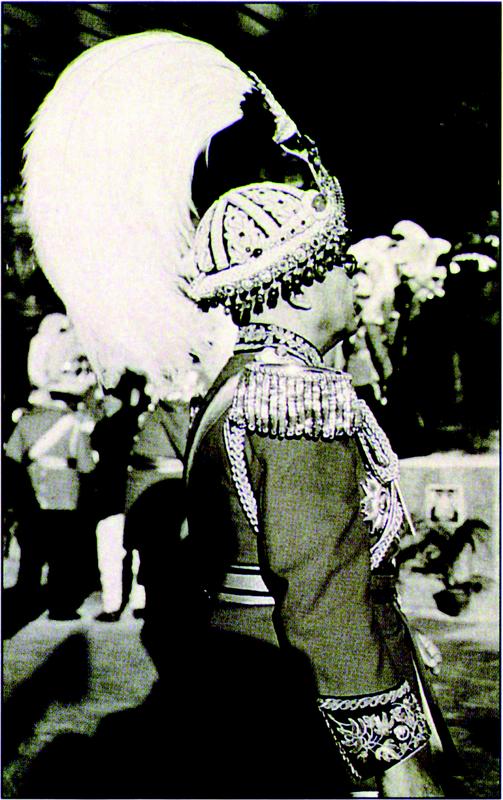

Plate 8: Commanding General Kaiser Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana wears four or more interwoven flank plumes of the Greater Bird of Paradise. At the same ceremony, see Plate 6, the King’s crown is adorned with at least six plumes. Plate 8 |

Plate 9: King Mahendra of Nepal wearing four or more interwoven flank plumes of the Greater Bird of Paradise at his coronation in 1957. Plate 9 |

64The first birds of paradise to reach Europe were trade skins

Birds of paradise were unknown in Europe until the sixteenth century. In 1522 bird of paradise skins were carried back to the King of Spain by Magellan’s circumglobal expedition. Although the Portuguese had reached the Spice Islands in 1512 there is no report that their crews took bird of paradise skins to Europe. The crew of the 1512 expedition were probably too elated with the rewards they would reap from being the first Europeans to discover the location of the fabled Spice Islands to be concerned with attractive feathers, no matter how splendid they were.

The crew of the Victoria, the only one of Magellan’s ships to survive the first circumnavigation of the world, took five skins of the Lesser Bird of Paradise back to Europe in 1522. These were obtained from the Sultan of Bacan in the Moluccas in November 1521.37 The crew reported that the Moluccans called the birds bolon diuata (birds of God) and claimed that they came from an earthly paradise.38 This was the beginning of wild speculations and misconceptions about birds of paradise in Europe.

Since trade skins had no feet or wings the Portuguese called them Passaros de Sol meaning birds of the sun, whereas the later arriving Dutch gave them the Latin name Avis paradiseus or paradise bird. It was initially assumed by many Europeans, since none had seen any live specimens, that the birds lived in the air, always turning towards the sun and never landing on earth until they died, for they had neither feet nor wings. These scholarly speculations caught the imagination of the general public. As a result birds of paradise were painted by artists, sung about by poets and became the topic of edifying contemplation by theologians.

By 1600 ships’ crews were bringing Greater, Lesser and King Birds of Paradise skins to Europe. In 1605 Carolus Clusius of Leiden University was able to describe these three species from skins obtained in Europe. This trade did not involve large numbers of skins. For instance, in 1652 it was said that it was as rare to see a shop open on Christmas Day, as to see birds of paradise. They were still rare in England in 1670, but less so in Holland and Germany where collections were being established.39

The confusion about the feet and wings arose because of the way New Guineans preserve birds of paradise. As mentioned above, the entire bird is skinned in order to accentuate the beautiful plumes. During this process the legs, skull and coarse wing feathers are usually removed during skinning.40 Ash is applied to the inside of the skin and a stick is inserted through the mouth into the body cavity. The skin is then smoke dried. As the skin dries it collapses onto the stick which 65protrudes beyond the bill. Mounted in this way it is easy to incorporate the bird skin into a headdress. When not being worn the skins are usually stored in sealed bamboo tubes or palm leaf wrappings in the rafters so that fireplace smoke protects them from insects.

By 1605 bird of paradise skins with feet had been brought to Europe. The first illustration of a bird of paradise with feet was published in Europe in 1655. Some theologians ignored all this and persisted with the theory that the birds did not have feet. It took time to convert these stubborn doubters. Such views only ceased in 1660 when sufficient numbers of specimens with feet could be viewed in collections.

European scholars continued to conjecture wildly about birds of paradise, unaware that Dutch scholars based in the Dutch East Indies had learnt much about the birds by interviewing Indonesian traders. In the late 1670s many details about birds of paradise were published by Johann Otto Helwig who worked as a doctor and naturalist in Batavia. In 1682 Herbert de Jager, Chief Merchant with the East Indies Company in Batavia, published a description of how birds of paradise were hunted and how their skins were prepared.41

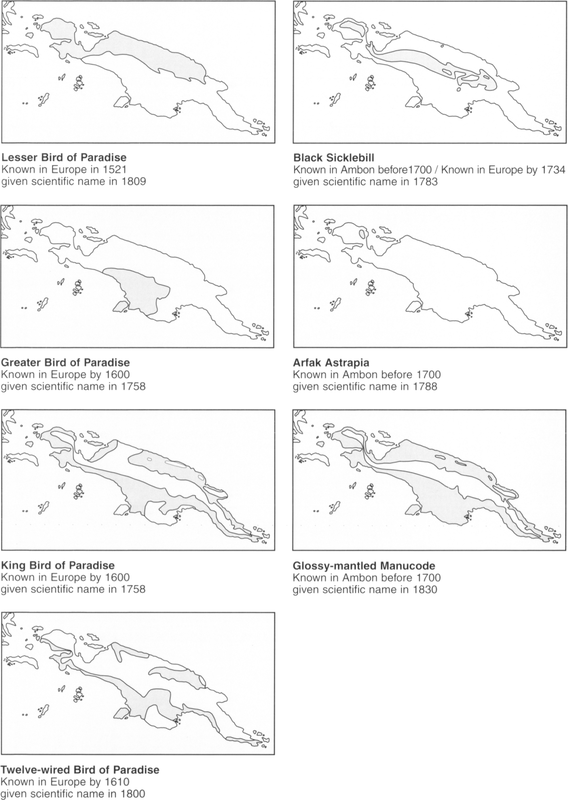

The history of how the different species of birds of paradise reached Europe provides an indication of their availability as trade products. The Greater, Lesser, King and Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise were the first to gain the attention of naturalists in Europe. All four were painted from trade skins by Jacob Hoefnagel in 1610.42

The great Dutch naturalist George Eberhard Rumphius illustrated three birds of paradise while he lived on Ambon from 1653–1702. These illustrations were later found and published by François Valentijn in 1726. The three species drawn by Rumphius from trade skins before he went blind in 1670 were the Greater, Lesser and King Birds of Paradise. Rumphius also described trade skins of the Arfak Astrapia, Black Sicklebill, Glossy-mantled Manucode and Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise.43

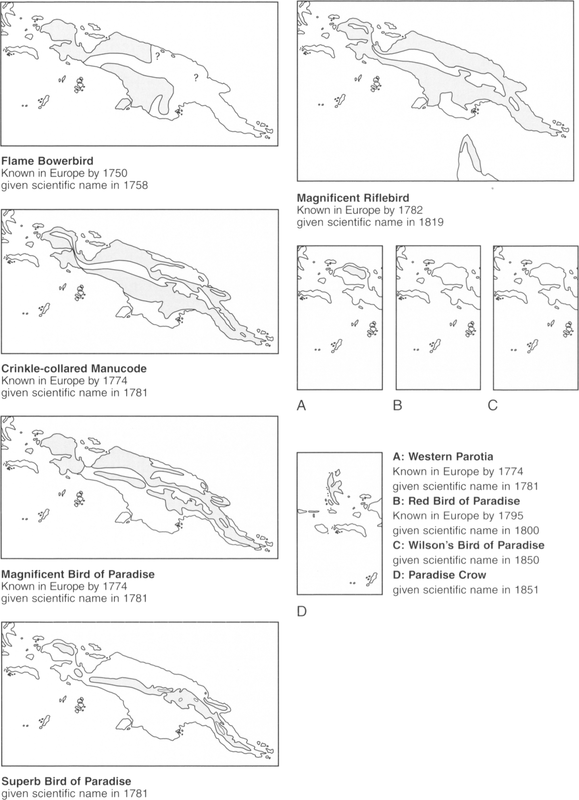

Other trade skins were illustrated or painted in Europe from 1734–1782. The Black Sicklebill was illustrated by Albertus Seba in 1734 in his Thesaurus and the Flame Bowerbird was painted by George Edwards in 1750. In 1774 the Magnificent Bird of Paradise, the Black Sicklebill (both sexes), the Crinkle-collared Manucode and Western Parotia were illustrated by Le Comte de Buffon in the 25th edition of the Planches enluminées. Some years later, in 1782, the Magnificent Riflebird was illustrated by François Levaillant.44

A trade skin of the Red Bird of Paradise was among the birds of paradise obtained as battle spoils from The Hague in 1795 and subsequently deposited in the Paris Museum.45 It was probably also in 66Paris in 1850 that Edward Wilson purchased a trade skin of the Wilson’s Bird of Paradise.46

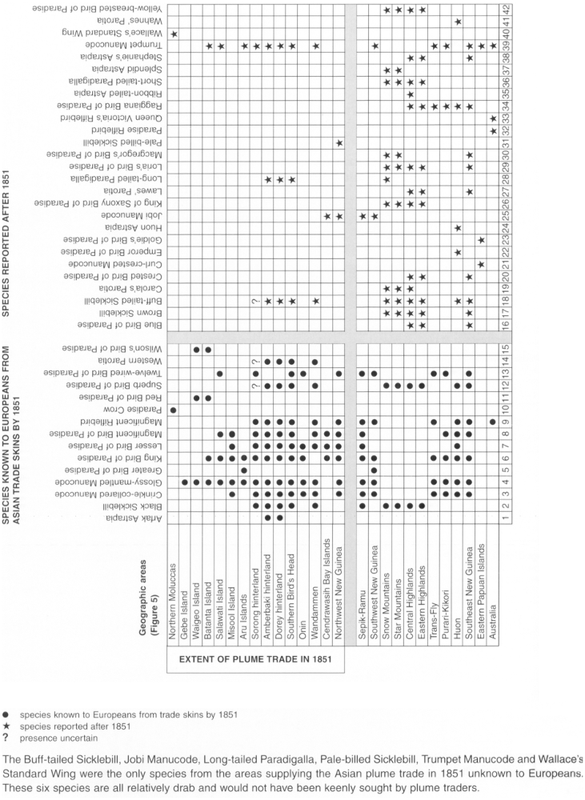

All the brilliantly coloured species found in the area where Asian traders were active (Figure 15) were known to Europeans from Asian trade skins by 1851; see Tables 2 and 3 and Figures 16 and 17. The only birds of paradise which occur in this area and were not obtained by Europeans as trade skins are relatively drab and would not have been sought for their plumes. These species are the Long-tailed Paradigalla, Wallace’s Standard Wing, the Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Palebilled Sicklebill, Trumpet Manucode and Jobi Manucode. Judging from the history of their availability as trade skins it would seem that the Greater, Lesser, King and Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise were the main species sought by Asian plume traders.

The Greater Bird of Paradise was the first bird of paradise described scientifically; see Table 2. This was done from a trade skin in 1758. The King and the Flame Bowerbird were also described in that year. Ironically the first bird of paradise to reach Europe, in 1522, the Lesser Bird of Paradise, was not described scientifically until 1809.

Figure 15: The geographic areas used in Table 3. The hinterlands of Sorong, Amberbaki and Dorey are shown to overlap as it is not known how far plumes were traded in these areas.

Source: Based on Beehler et al 1986: 4.67

Table 2: Birds of paradise and bowerbirds identified from trade skins by 1851. They are grouped by distinguishing features.

| Birds of Paradise | |

| iridescent throat, upper breast and crown plumes | |

| Magnificent Riflebird | Ptiloris magnificus (Vieillot, 1819) |

| flag-tipped wires from tufts on each side of nape | |

| Western Parotia | Parotia sefilata (Pennant, 1781) |

| erectile cape of feathers springing from nape | |

| Superb Bird of Paradise | Lophorina superba (Pennant, 1781) |

| filamentous display plumes | |

| Greater Bird of Paradise | Paradisaea apoda (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Lesser Bird of Paradise | Paradisaea minor (Shaw, 1809) |

| Red Bird of Paradise | Paradisaea rubra (Daudin,1800) |

| thread-like tail wires | |

| King Bird of Paradise | Cicinnurus regus (Linnaeus, 1758) |

| Magnificent Bird of Paradise | Cicinnurus magnificus (Pennant, 1781) |

| Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise | Seleucidis melanoleuca (Daudin, 1800) |

| Wilson’s Bird of Paradise | Cicinnurus respublica (Bonaparte, 1850) |

| tail long and step-like | |

| Arfak Astrapia | Astrapia nigra (Gmelin, 1788) |

| tail long and graduated | |

| Black Sicklebill | Epimachus fastuosus (Hermann, 1783) |

| plumage black glossed purple to green | |

| Crinkle-collared Manucode | Manucodia chalybata (Pennant, 1781) |

| Glossy-mantled Manucode | Manucodia atra (Lesson, 1830) |

| crow-like | |

| Paradise or Silky Crow | Lycocorax pyrrhopterus (Bonaparte, 1851 ) |

| Bowerbirds | |

| Flame Bowerbird | Sericulus aureus (Linnaeus, 1758)68 |

Figure 16: The natural distribution of birds of paradise which become known to Europeans from trade skins by 1700.

Source: Based on Coates 1990; Cooper and Forshaw 1977.69

Figure 17: The natural distribution of birds of paradise which became known to Europeans from trade skins between 1700 and 1851.

Source: Based on Coates 1990; Cooper and Forshaw 1977.70

Table 3: Distribution of birds of paradise showing species known to Europeans before and after 1851.71

Notes

1. Ian Craven (personal communication 1989) obtained this figure by calculating what percentage the 725 known bird species found in New Guinea (Beehler et al 1986) were of the total world population of just over 8,600 (Scott 1989).

2. Wallace 1879: 425–6.

3. Torrence and Swadling 2008; Swadling and Hide 2005; Swadling 2005; Swadling, Weissner and Tumu 2008; Swadling 2013; Swadling 2016; Swadling 2017.

4. Araho, Torrence and White 2002.

5. Torrence and Swadling 2008; Torrence, Swadling, Kononenko, Ambrose, Rath and Glascock 2009.

6. Swadling 1981, 1986.

7. Swadling 2005; Swadling, Weissner and Tumu 2008.

8. There is no reason to doubt the find locations for the Lae-Wampar, Aikora, Wonia and Ningerum bird pestles. The Lae-Wampar (Lae-womba) lived about 20 km upstream from the mouth of the Markham River. It was the first reported by Holtker 1951: 240–241. The Aikora bird pestle was found by gold prospectors in an alluvial terrace of the Aikora River, an upper tributary of the Gira River. It was first reported by Barton 1908. The Wonia bird pestle was collected by C.W. Marshall in 1927 (Specht 1988) and the Ningerum find was collected by the late Herman Mandui of the Papua New Guinea National Museum.

9. Denham 2011.

10. Denham 2011.

11. Bellwood 1989: 149.

12. Unlike peacocks birds of paradise are not easily bred. This means that a regular supply of bird of paradise plumes could not be obtained by breeding, instead the plumes had to be imported. Live birds of paradise were traded, but these were rare and expensive. In 1862 Alfred Russel Wallace paid £100 for two live male specimens of the Lesser Bird of Paradise in Singapore. One bird died after a year, the other survived for two years at the Zoological Gardens in London (Wallace 1986: 557; Preswich 1945).

13. Doughty 1975: 7.

14. Wang 1958: 4.

15. Glover 1990; Higham 1989.

16. Bellwood 1978a: 185.

17. Bellwood 1978a: 222.

18. Kempers 1988; Spriggs and Miller 1988; Spennemann 1985a, 1987.

19. Bellwood 1978a: 222.

20. Elmberg 1968: 125–6.

21. Ambrose 1988.

22. Bintarti 1985.

23. Soejono 1963.

24. Galis 1964.

25. Soejono 1979: 194.

26. Agogino 1979; Agogino 1986.

27. Higham 1989: 357, 361.

28. The sandalwood came from Timor. The best quality white sandalwood supplied to western Indonesia and India still comes from this island.

29. Bachtiar 1963: 55.

30. Rouffaer 1915 cited by Galis 1953–4: 6; O’Hare 1986.72

31. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 65.

32. Doughty 1975: 10.

33. Sonnerat 1781: 42.

34. Stresemann 1954: 263.

35. Gilliard and Riboud 1957: 146; LeCroy 1985: Ripley 1950.

36. Anthony Forge personal communication 1984.

37. Stresemann 1954: 263.

38. Stresemann 1954: 264; Cooper and Forshaw 1977: 17.

39. Stresemann 1954: 272: Trend 1988: 30.

40. Wallace (1857: 412) reports that the flesh of the Greater Bird of Paradise is dry, tasteless and tough.

41. Helwig 1678, 1679 and Jager ca. 1682, published in 1704 cited by Stresemann 1954: 273.

42. Stresemann 1954: 270.

43. Stresemann 1954: 274–5: Gilliard 1969: 22.

44. Stresemann 1954: 275–6.

45. Stresemann 1954: 277.

46. Gilliard 1969: 211.