11

Bronzes and plume hunting in the

Jayapura (Hollandia) region

Asian plume trade

Although there were links within mainland New Guinea 5,000 years ago, as shown by the distribution of stone mortars and pestles, archaeology has not revealed any with Southeast Asia. Even within New Guinea it is curious that so few mortars and pestles have been found in what is now West Papua (Figure 9), but the existence of interaction along the north coast of New Guinea is confirmed by the find of a stemmed obsidian artifact at Biak in Cendrawasih Bay. It is made from obsidian that originated from Manus in Papua New Guinea.1

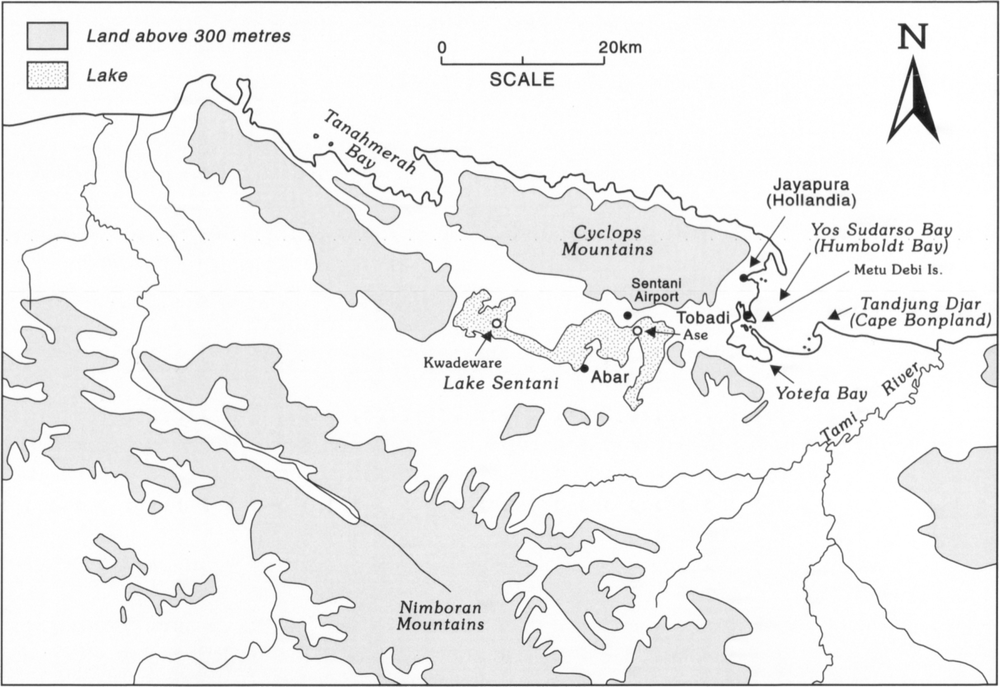

Three thousand years later the north coast gains archaeological prominence again. This time because of the large number of prehistoric bronze artifacts that have been reported at Lake Sentani inland of Jayapura (Figures 42 and 43).2 These artifacts date from just before 2,000 years ago until about 250 AD. During this period Asians are known to have keenly sought beautiful bird plumes. The occurrence of these artifacts at Lake Sentani is not so surprising, when it is known that Hollandia (now Jayapura), was a famous export port for bird of paradise plumes on the north coast of New Guinea during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

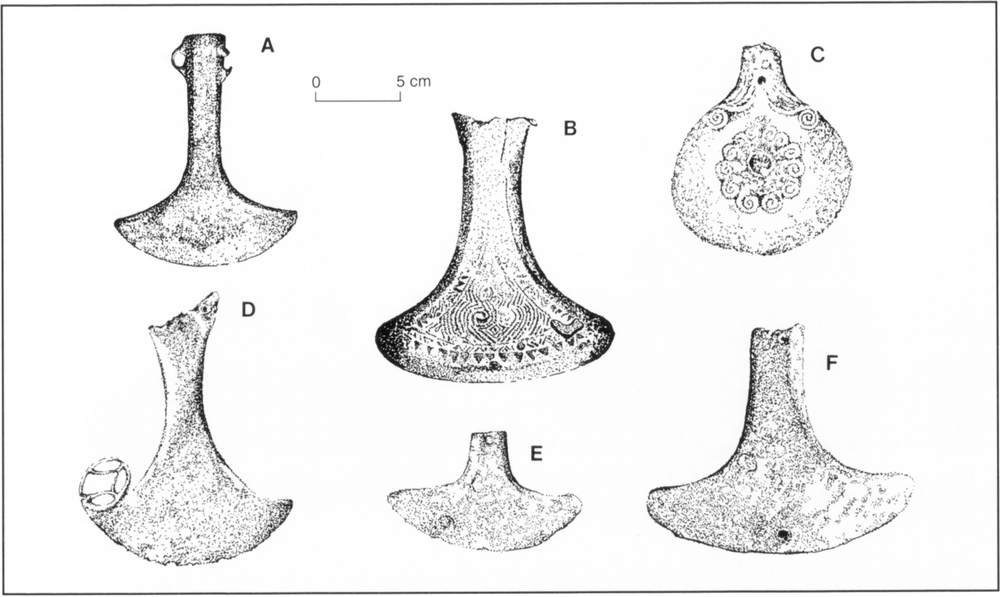

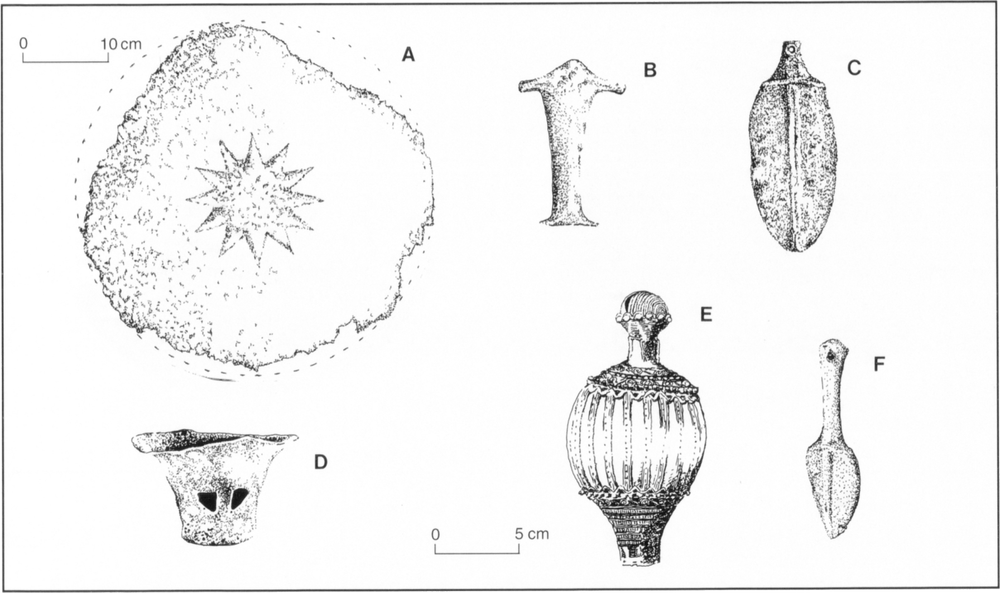

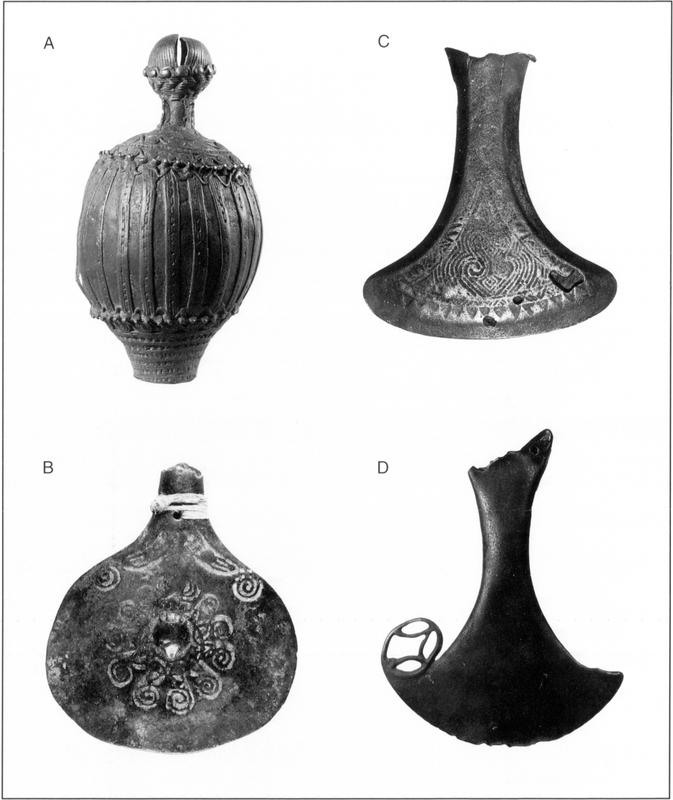

Some of the bronze artifacts were dug up by villagers in places where sacred objects used to be buried, others were held as heirlooms in men’s houses. While many bronzes are now in museums, some still remain in village ownership, such as the collection held at Kwadeware (Figure 43), and can be viewed by interested individuals after paying a viewing fee. The main finds are illustrated in Figures 44 and 45 and Plate 31.

As mentioned in Chapter 3 some of the Sentani bronzes are comparable to those found elsewhere in Indonesia, whereas others are unique to West Papua. The latter include three ceremonial axe forms, namely a, c and d illustrated in Figure 44 and the spearheads from Kwadeware (Figure 45: c and f).

206When George Agogino3 investigated two Bronze Age archaeological sites on the north side of Lake Sentani during World War II he found the bronzes to be associated with glass beads. This suggests that many of the antique glass beads,4 earrings and bracelets found in the Jayapura region could have a comparable antiquity to the bronzes. These glass artifacts (Plate 32) have also become traditional valuables for the people of the Vanimo region, who continue to obtain them from Jayapura. In the Vanimo region in 1980 a single blue bead was worth K100, whereas bracelets were valued at K400 to K700 each.5 Observations of similar artifacts were made before 1656 at Biak and on Seram. They were so highly valued in the eastern Indonesian archipelago that Dutch traders requested that green glass bracelets be manufactured in the Netherlands in the eighteenth century (Plate 32B). The Dutch replicas were not a success.6

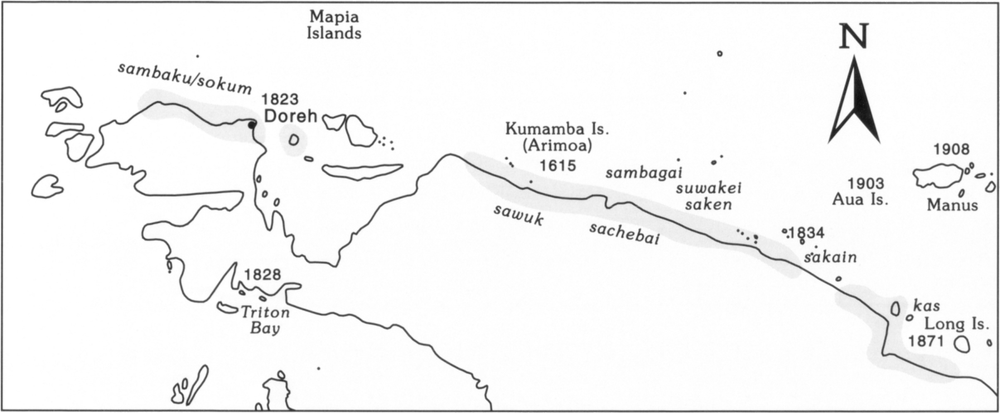

Figure 43: The Jayapura region.207

Figure 44: Some of the bronze axes found at Lake Sentani A. axe from Kwadeware B. ceremonial axe from Ase C. ceremonial axe from Abar D. ceremonial axe from Ase E. axe from Kwadeware F. axe from Kwadeware.

Sources: de Bruyn 1959; de Bruyn 1962; van der Sande 1907; Soejono 1963. Drawings by Anton Gideon.

Figure 45: Some of the bronze artifacts other than axes found at Lake Sentani and the Bird’s Head. (larger scale only applies to the drum top). A. drum top from Aimura Lake B. dagger handle from Kwadeware C. spearhead from Kwadeware D. lamp from Kwadeware E. bell from Ase F. spearhead from Kwadeware.

Sources: de Bruyn 1959; de Bruyn 1962; van de Sande 1907; Soejono 1963. Drawings by Anton Gideon.208

Plate 31: Bronze bell and ceremonial axes from Lake Sentani villages, Jayapura region (for scale see Figures 44 and 45).

A. bell from Ase B. ceremonial axe from Abar C & D. ceremonial axes from Ase.

Photos: Courtesy Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, The Netherlands.209

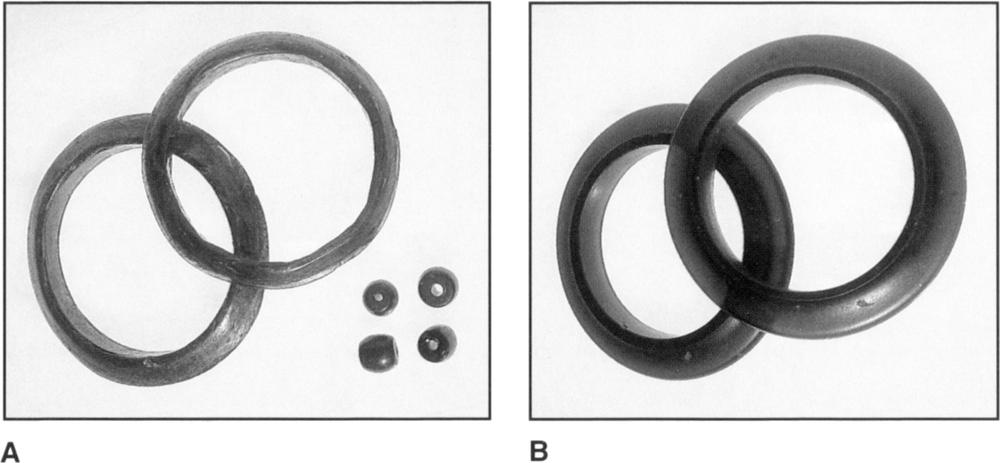

Plate 32: Prehistoric and historic glass bracelets and beads from the north coast of New Guinea.

A. The prehistoric bracelets are from Ase and the beads from Tobadi. Width of rings 8 and 10 centimetres. The Vanimo people have similar artifacts. Today these artifacts are prohibited exports from Papua New Guinea.

B. Glass bracelets manufactured in the Netherlands in the eighteenth century. Width of each bracelet 10cm.

Photos: By Rocky Roe for PNG National Museum.

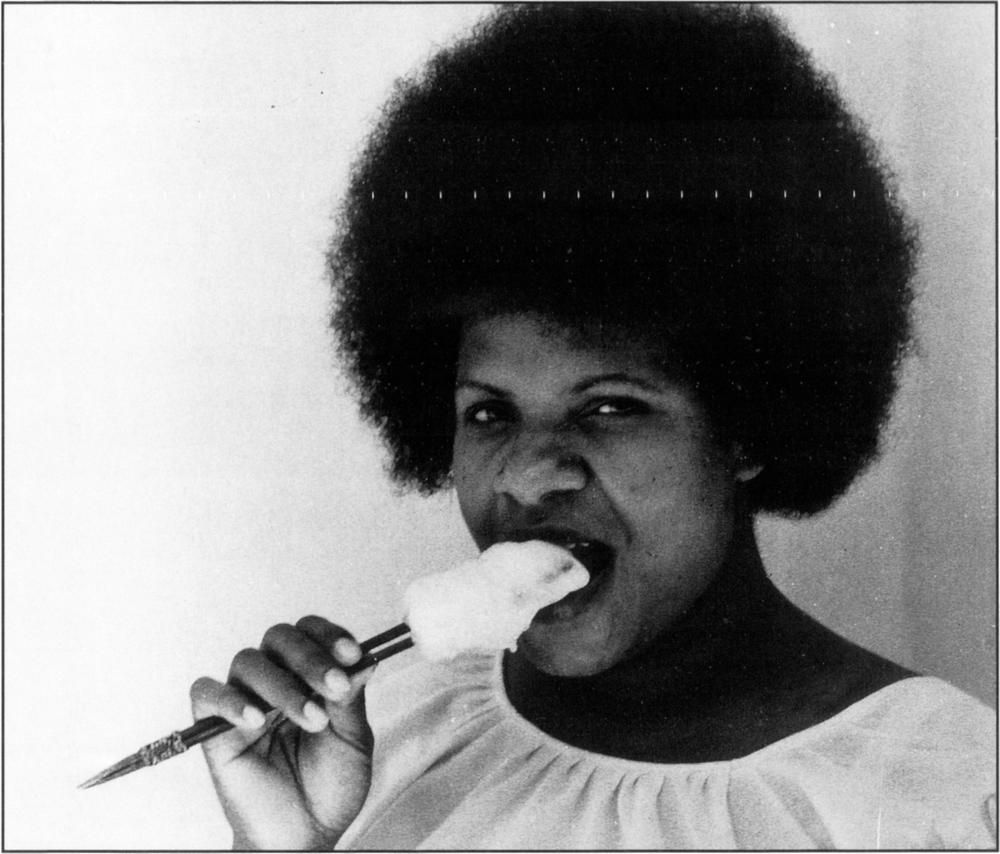

Plate 33: Frances Deklin from Wanimo village demonstrates how heai (tongs) are used to eat stirred sago.

Photo: By Pou Toivita for PNG National Museum.

Other cultural practices of the people in the Jayapura and Vanimo regions may date back to 250 AD and before. For instance, they use a special implement to cook and eat sago. These were also traditionally used on Seram and in the Moluccas (Figure 46).7 Many of the Vanimo implements look like tied chopsticks. The small ones (heai) are used to eat stirred sago (Plate 33), whereas larger tongs are called heai pilo. The latter are used to get the sago out of big saucepans. Mothers with newborn babies use these tongs for all food consumption, as they cannot touch food by hand for a period of about three months after giving birth. The tongs are made from palm stem.8

The withdrawal of Asian interest from the Jayapura region and the Bird’s Head occurred with the downturn in the Asian plume trade about 300 AD. There was then a long hiatus before traders again brought metal implements to the Jayapura region.9210

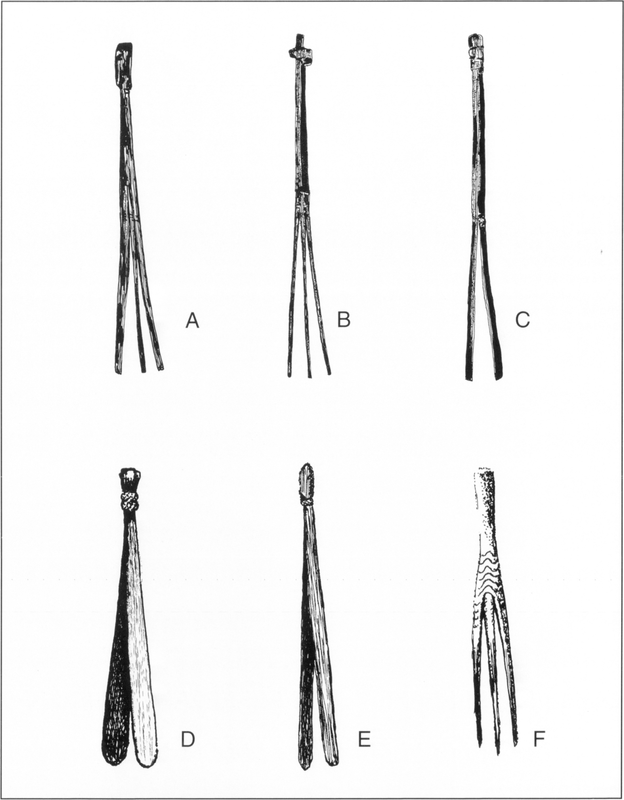

Figure 46: Tongs and forks used in the Moluccas and Jayapura region.

A. Moluccas B. Moluccas C. Moluccas D. Humboldt Bay E. Lake Sentani F. Ase, Lake Sentani Similar tongs to D and E are used in the Vanimo region of Papua New Guinea. A–C are 26–27 centimetres and D–F about 22 centimetres in length.

Sources: Avé 1977; van der Sande 1907.

211Subsequent foreign trade on the north coast of New Guinea

The presence of Chinese ceramics in the Kumamba Islands in 1616 and T. Forrest’s observation that Chinese traders were visiting the Waropen coast for massoy in 1775 suggest a history of Chinese trade along the coastline from Waropen to the Kumamba Islands (Figures 26 and 42). These Chinese traders may have been responsible for introducing tobacco, as tobacco was offered by Kumamba (Arimoa) Islanders to the crew of Schouten’s ship in 1616. They also had Chinese porcelain in their canoes.10 Coastal trade would have led to the distribution of tobacco seeds and explains the chain of related words for tobacco found from Amberbaki on the Bird’s Head to just west of the Sepik River mouth,11 see Figure 47.

Until the Tidorese hongi raids, the Kumamba Islanders had a long record of welcoming visitors. Abel Tasman in 1642 reports obtaining 6,000 coconuts and 100 bags of bananas in exchange for knives made from hoop iron on Jamna Island in 1642.12 Likewise, in 1840 E. Belcher reports that Jamna Islanders in the Kumamba group were interested in trading coconuts for hoop iron and beads. Curiously, although the Jamna Islanders wore bird of paradise plumes in 1840, they did not offer them as trade goods.13

In 1848 the Sultan of Tidore began asserting his authority over New Guinea. Hongi raids on this coast had the same devastating impact as in the Kowiai area (see Chapter 8). When B.G.F. de Kops visited Kurudu Island off the Waropen coast (Figure 26) in 1849, he learnt that the Singaji from Gebe, who was appointed by and answered to the Sultan of Tidore, had recently ransacked the island and seized 200 men as slaves. Kops also reports that this same Singaji claimed that his hongi fleets had already been to Kurudu six times.14

The coastline east of Kurudu was also subjected to Tidorese hongi attacks. In 1848 a fleet was sent by the Sultan of Tidore to subjugate the mainland near the Kumamba Islands (Figure 42). It appears they were expected, as their crews were attacked and they were compelled to retreat with six dead and many wounded.15 Retaliation by Tidore probably took place.

The chief objective of the voyage of the Circe in 1849 and an accompanying Tidorese hongi fleet was to assess the potential of Humboldt Bay (now Yos-Sudarso Bay) for settlement and to mark the north coast as far east as the 141st meridian for the Sultan of Tidore (Figure 42).16 The Circe became separated from the hongi fleet and had to return to Ambon without landing at Humboldt Bay because of strong southeast winds and a lee current.

On the north coast west of Humboldt Bay but east of the Kumamba Islands, Kops reports in 1849 that some men came out in canoes to the 212Circe with bundles of bows and arrows, bird beaks, leaves and empty coconuts. For the bows and arrows they received some empty bottles and beads. What they really wanted were knives, but their trade items were considered useless by those on the Circe.17

Early in 1852 a garrison was established at Humboldt Bay consisting of a party of burghers, or native militia from Ternate.18 This garrison must have been short-lived as there is no further mention of their activities. Their presence probably antagonised the local people and made them less receptive to visitors, as the Prince of Tidore and Resident of Banda who visited Humboldt Bay in 1858 onboard the Etna, a Dutch war steamer, initially received a hostile reception. The local people indicated that they would fire their arrows if any attempt was made to land, but after the Captain threw some presents ashore, they permitted those who wished to do so to go ashore. Fruits and vegetables were provided for the visitors and they were free to wander around. As the Dorey interpreter was unable to communicate with the people, all communication was by sign language.19

The Tidorese raids which occurred in the 1840s clearly had a devastating impact on the Kumamba Islands and nearby coast. There is no doubt that the belligerent response it brought about slowed the extension of foreign trade along this coast. Even in the 1870s most visitors avoided the Kuramba Islands and the nearby mainland coast. Those traders that did try to make contact received a hostile reception. This was the case in the early 1870s with Captain Deighton who was highly respected in Cendrawasih Bay.20

When the steamship Dossoon visited Humboldt Bay in October 1875, the people were keen to trade but had little to offer. All they had was some smoked fish and unripe fruit.21 Traders and bird of paradise hunters did not become active in the area until the early 1880s and the first trade store was established in the 1890s. When the missionary G.L. Bink visited Lake Sentani in 1893, he found that the people there still did not have metal and used stone tools and shells for woodworking.22 This quickly changed. By 1903 iron was widely available, but some village men at Lake Sentani continued to make stone axes.23

Bird of paradise collectors and hunters

The first bird of paradise collectors to work in the Jayapura region were probably participants of the 1858 Dutch border expedition. Rosenberg, a German naturalist and draughtsman, was a member of the survey team who sailed on the Etna in 1858. He took two assistants with him. They were delegated the task of shooting and skinning birds. Rosenberg also purchased a few rare skins from the local people.24213

Figure 47: The distribution of cognate names for tobacco and the earliest reports of its presence on the north coast of West Papua and Papua New Guinea.

Source: Based on Riesenfeld 1951.

Although bird of paradise collecting had begun in the Jayapura region in 1858, Ternatian hunters were not active on this part of the north coast and its immediate hinterland until the 1880s. This was when Cape Djar (Cape Bonpland) became known as Cape Saprop Mani (land of birds) (Figure 43).25 In the 1890s a number of Chinese, Ternatians and Tidorese established a trading station on Metu Debi Island at the entrance between Yotefa Bay and Humboldt Bay (Figure 43). Bird of paradise hunting and trading was their main source of income. A European trader, J.M. Dumas, also established a trading post on this island. Their activities not only supplied the plume trade but also scientific specimens for European museums.26

Apart from establishing coastal bases Ternatian bird hunters began to venture inland. The sale of three specimens of the Golden-Fronted Bowerbird (Amblyornis flavifrons) to the British zoologist Lord Rothschild in 1895 indicates that Ternatian hunters had penetrated inland to the Foja Mountains by the early 1890s (Figure 42). These trade skins made the species known to the scientific world in 1895, but it remained a mystery until recently as to where in New Guinea the Indonesian bird hunters had obtained this bird. It was not until 1981 that the natural habitat of the species was discovered in the Foja Mountains.27

Hollandia was established in 1909–10 as the base camp for the expedition which had the task of determining the boundary between Dutch and German New Guinea. Its leader condemned the Hollandia (Jayapura) region as being unhealthy when one member of the expedition died and others became ill with malaria, beriberi and sleeping sickness. The people of the Humboldt Bay region also became renowned for killing bird hunters. Scarcely a month passed during the boom years when there was not some conflict between the local people and bird hunters.

214This reputation played a part in discouraging European traders and planters. Even in the 1930s Chinese traders owned and ran most of the trade stores at Hollandia and other centres on the north coast of Dutch New Guinea. Their success owed much to their ability to obtain a wide range of cheap goods from China and Japan and have lower overheads than any Dutchman could achieve. These Chinese traders were not discouraged by the Dutch colonial government as they made a considerable contribution to the colonial revenue by means of the taxes and import and export duties they paid.28

In 1900 bird of paradise skins were worth about 15–20 guilders (about 1 pound 10 shillings to £2) and goura pigeons 2 guilders. Hunters brought the skins to traders who exchanged them for goods.29 Prior to 1907 two Chinese traders are reported to have exported 12,000 birds every three months.30 Chinese businessmen in Hollandia also advanced large sums of money to Ternatian (Plate 34) and Tidorese bird hunters. In 1911, for instance, some 60 hunters owed traders the sum of 20,000 guilders.31

These hunters covered large areas in their search for plumes. They travelled over the border into German New Guinea (see Chapter 12), and also covered vast distances in Dutch New Guinea. For instance, H.J. Lam, a Dutch naturalist, was impressed by a party of two Chinese and nineteen New Guinean bird hunters who visited his camp at Prauwen-bivak (Figure 42) during his 1920 expedition (Plate 35). They had travelled overland from Hollandia to the headwaters of the Idenburg River, living off the land, in order to hunt birds of paradise and goura pigeons. Near the coast they had been able to obtain food from villages through which they passed, but in uninhabited areas they had to live off the land. Each day part of their group either made sago, fished or hunted for food, whilst the others hunted birds of paradise and goura pigeons. Travelling in this way they reached the banks of the Idenburg in just over 70 days. There they made four praus and after seven days reached Prauwen-bivak. The hunters stayed with Lam’s party for some time while they sought birds nearby.32

Hollandia was the main centre on the north coast of Dutch New Guinea for trading in bird of paradise skins (Plate 36). When the Australians occupied German New Guinea during the First World War, some German planters crossed the border and settled in Hollandia in Dutch New Guinea. One of these Germans was Herr Stuber. He continued his plume-hunting trade,33 whereas other Germans either established coconut plantations near Hollandia and Sarmi (Figure 42) or became active in the copal (tree resin) industry.34215

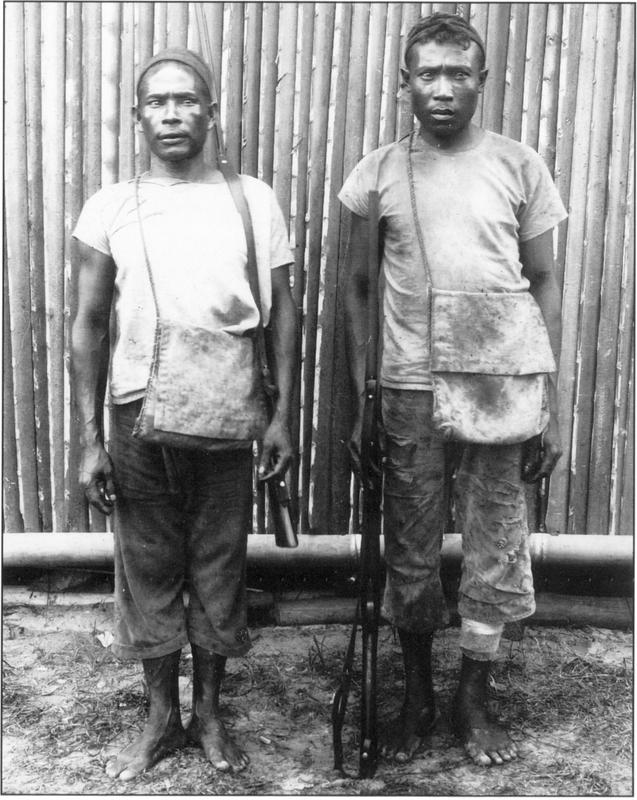

Plate 34: Rassip and Marinki, bird hunters from Ternate.

Photo: Courtesy of Fotobureau, Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, Amsterdam.

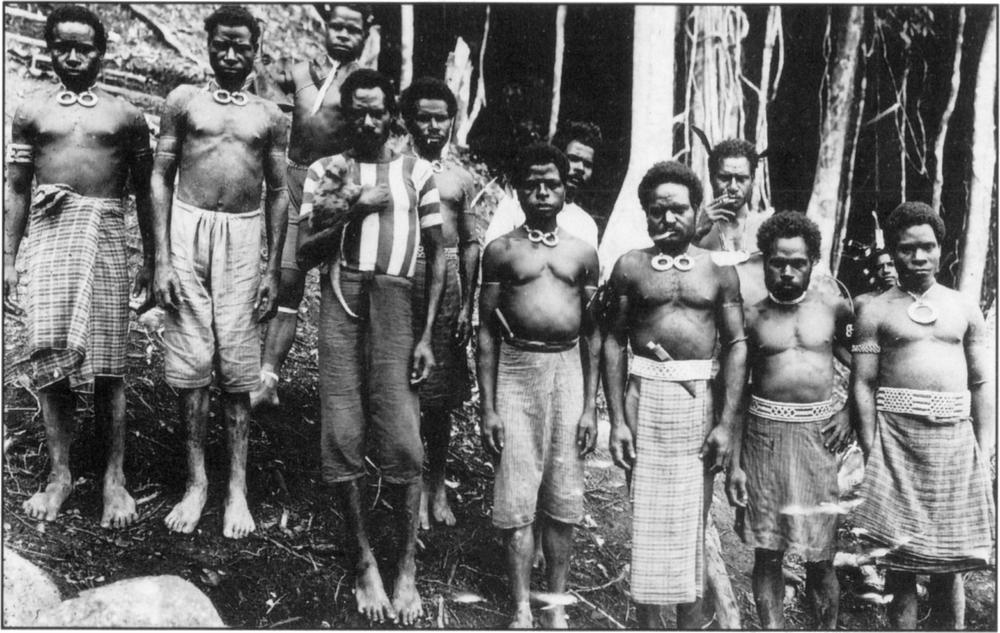

Plate 35: Some of the nineteen New Guineans employed by two Chinese bird hunters who visited Prauwen-bivak on the lower Idenburg River in 1920. To reach Prauwen-bivak they had travelled for 70 days overland and 7 days by river since leaving Hollandia.216

Photo: Courtesy of Fotobureau, Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, Amsterdam.

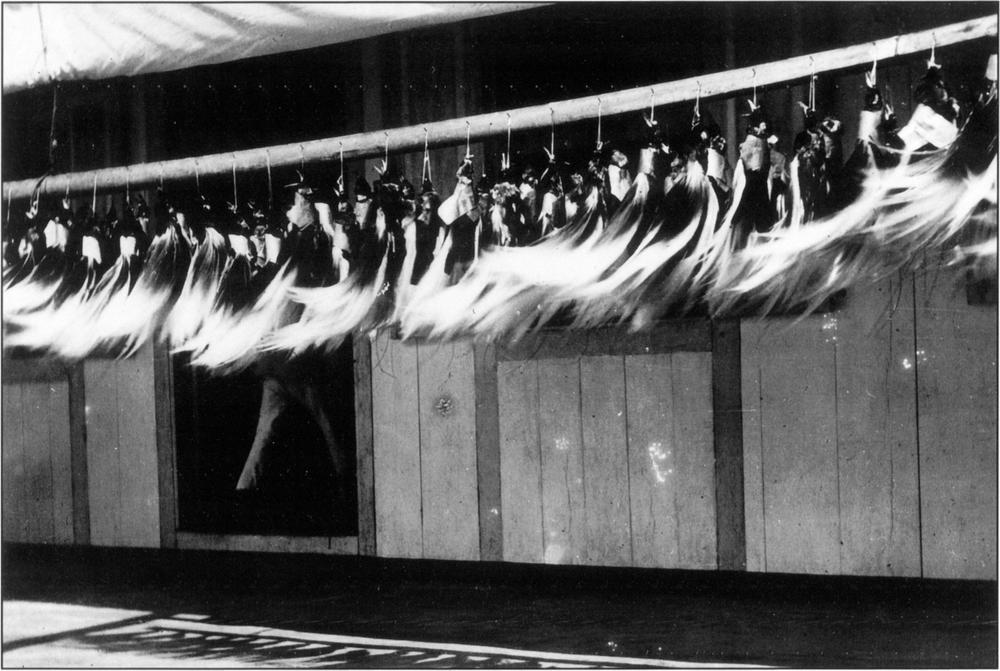

Plate 36: Lesser Bird of Paradise skins hanging in front of a trade store, probably in Hollandia.

Photo: Courtesy of Fotobureau, Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, Amsterdam.

When the plume trade was prohibited in the Mandated Territory of New Guinea in 1922, bird skins continued to be smuggled across the border into Dutch New Guinea and exported from Hollandia. In 1924 bird of paradise trading was prohibited in much of Dutch New Guinea,35 but was allowed to continue in the Hollandia area until 1931.36 Even so the boom was over.

As described in Chapter 5, the passing of the Plumage (Prohibition) Bill in 1921 by the United Kingdom played a major role in the trade’s decline. It meant that Britain had now joined the United States and Australia in banning the importation of birds of paradise. The demand for plumes by the European fashion market slumped. Although the Asian market remained, it could not absorb the large numbers of bird skins previously destined for European markets. This allowed fully plumed male birds of paradise to be seen displaying on the outskirts of Hollandia in 1929.37 When bird of paradise hunting was prohibited in the Hollandia area in 1931, most hunters left.

In the 1930s Evelyn Cheesman found Hollandia to be a small village, most of the inhabitants being Indonesian or Chinese. A few old Indonesian down-and-outers, who not so long ago had been making 217fortunes as bird hunters, still remained. The large number of Chinese stores in the small settlement were another indication of the past boom.38 These Chinese traders continued to import all sorts of foreign goods, including rice, textiles, metalware, fuel and beads.39

When bird hunting was prohibited, the main products exported from Hollandia became massoy bark at 100 guilders (ca £9) a pikul (60.5 kilograms), lawang bark at 60–70 guilders a pikul, trepang at 100 guilders per pikul, trochus shell at 50 cents each, mother of pearl shell at 25 cents each and, after 1930, coffee and cotton in small quantities.40

The Dutch Controller at Hollandia in the 1930s was responsible to the Assistant Resident based at Manokwari, who in turn reported to the Resident at Ambon. The Dutch had made a good road from Humboldt Bay to Tanah Merah Bay (Figure 43). Villagers near this road were taxed, but the Dutch had no control at that time over inland groups. Cheesman was surprised to find how few planters were established in the vicinity of Hollandia. Most plantations were run by local men with foreign fathers. Of the seven European planters, three were Germans who had crossed the border after the First World War.41

Notes

1. Torrence and Swadling 2008; Torrence, R., Swadling, P., Kononenko, N., Ambrose, W., Rath, P. and Glascock, M.D. 2009.

2. Bintarti 1985; de Bruyn 1959; de Bruyn 1962; Galis 1956; Galis 1964; van der Sande 1907; Soejono 1963; Tichelman 1963.

3. Agogino 1979, 1986. These references were kindly brought to my attention by Chris Ballard.

4. Other beads are recognised as having recently come into circulation.

5. Frances Deklin personal communication 1980.

6. van der Sande 1907: 224.

7. van der Sande 1907: 7; Ave 1977: 24.

8. Tony Deklin personal communication 1979.

9. The lack of regular trade between eastern Indonesia and the Madang coastline suggests that the sixteenth century Malay kris (dagger), reputedly dug up on Long Island in association with a human skull (Egloff and Specht 1982: 444), may have reached Long Island as an heirloom or curio on board a European ship.

10. Dumont d’Urville 1853 cited by Riesenfeld 1951: 76.

11. The use of tobacco was not known in the 1890s on Wuvulu or Aua, nor on any of the other Manus islands (Riesenfeld 1951: 72–3). On the Madang coast the name kas and its derivatives (kash, kast) are dominant. When Miklouho-Maclay went to the Rai coast in 1871 people were cultivating and smoking tobacco. The old men said that their fathers had obtained tobacco seeds and had adopted the practice of smoking from the west. Miklouho-Maclay 218observed that smoking and cultivating tobacco was not known to some villagers living in the inland mountains when he was resident on the Rai Coast (Riesenfeld 1951).

12. Forrest 1969: ix.

13. Belcher 1843 cited by Hughes 1977: 28.

14. Kops 1852: 338.

15. Kops 1852: 323.

16. Kops 1852: 323, 348.

17. Kops 1852: 342.

18. Earl 1853: 91.

19. Wallace 1986: 511.

20. van der Crab 1879 cited by Whittaker et al 1975: 237.

21. van der Crab 1879 cited by Whittaker et al 1975: 237–8.

22. Kooijman 1959: 16.

23. van der Sande 1907: 174–5.

24. Wallace 1986: 508.

25. Cheesman 1949: 25, 126: Prescott et al 1977: 84.

26. Galis 1955: 14; Gilliard 1969: 430–1.

27. Aschenbach 1982; Diamond 1982a, 1982b.

28. Cheesman 1938a: 24–6, 35.

29. Galis 1955: 210–1.

30. Goodfellow 1907 cited by Buckland 1909: 161 (in German New Guinea colonial documents)

31. Galis 1955: 211.

32. Lam 1945: 65.

33. Cheesman 1938a: 30.

34. van der Veur 1972: 281.

35. Schultze-Westrum 1969: 300.

36. Cheesman 1938a: 40–4.

37. E. Mayr cited by Mary LeCroy personal communication 1991.

38. Cheesman 1938a: 36

39. Galis 1955: 210.

40. Galis 1955: 211.

41. Cheesman 1938b: 25.