5

The plume trade: the demands of

fashion-conscious European women and

the growth of the conservation movement

The history of fashionable feather wearing by Europeans

Although the Romans wore ostrich plumes, ornamental plumage did not become popular in Europe until the time of the Crusades (1096–1270). Crusaders reportedly returned with plumes amongst their spoils of war. In the thirteenth century the profession of trading and working in ornamental feathers was introduced into France from Italy. Initially plumes were used to decorate knights’ helmets and the hats of high ranking officials. Subsequently cavalier hats trimmed with ostrich plumes became popular in both Europe and Virginia.

Feather wearing remained a male activity in Europe until the late eighteenth century. In 1775 Marie Antoinette started a new fashion. It happened one evening when her husband, King Louis XVI of France, complimented her on the ostrich and peacock feathers she wore in her hair. Soon plume wearing became a fashion amongst the aristocratic ladies of France. It later spread to other European capitals. At royal courts or on other occasions more and more aristocratic women began wearing plumes set in jewelled brooches or in headdress clasps. Although the wearing of peacock feathers gained bad associations when Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI were executed during the French Revolution, plume wearing continued to be fashionable at royal courts in Europe and amongst the well-to-do.1

Village-prepared bird of paradise skins were initially used by European milliners. This was the case in the 1830s. When surplus natural history specimens became available to milliners they came to prefer these arsenic-cured skins because of their greater durability. This preference meant that the demand for village trade skins quickly declined. In the 1850s their price fell from two dollars to six pence each.2 As insufficient quantities were forthcoming from natural history collectors, specialist hunters had to be despatched to obtain and prepare arsenic-cured bird of paradise skins for the European plume trade. Ternate became an important centre supplying these skins to 84Europe. As mentioned in Chapter 4, Rennesse van Duivenboden and his son established the main plume firm; other plume merchants based in Ternate included A.A. Bruijn, who became Duivenboden’s son-in-law, and J. Bensbach.

The wearing of ornamental plumage in Europe was at first only within the means of people of high status. From the late nineteenth century improving economic circumstances allowed increasing numbers of women to follow the dictates of fashion, and milliners in turn began to gain access to an increasing range of species from all over the world. The demand for plumes increased in Europe and America as more and more fashion-conscious, middle-class, urban women wore the latest styles suggested by fashion houses in Berlin, London, New York and Paris. They were able to follow these fashion trends by subscribing to the growing number of fashion magazines and home journals.3 This demand by upper and increasing numbers of middle-class European women for hats with spectacular and beautiful plumes brought about the European plume boom of 1908.

Plate 11: A bonnet decorated with a bird of paradise in an 1882 English fashion magazine.

This Pifferano bonnet is made of fine black straw, lined with black velvet and trimmed with black satin strings and a bird of paradise.

Source: The Queen, 20 April 1882. By permission of the British Library.

85Although plume wearing by aristocratic women dates back to 1775, it was some time before bird of paradise plumes became available to milliners. Fashion magazines indicate that they were being worn by 1830 (Plate 10) and were also popular shortly after Queen Victoria was crowned in 1837. Export and import information indicate that the supply and demand for these plumes increased through the ensuing years and from time to time they featured in fashion magazines. In 1863 bird of paradise plumes were one of the favourite trims on the continent, and they decorated some of the French hats imported into New York in 1875. An English fashion magazine features a bonnet decorated with a bird of paradise in 1882 (Plate 11). Birds of paradise were also popular during the summer sales of bird feathers at Harpers Bazaar in New York in 1896.4 By 1908 they were one of the mainstays of the plume trade. Plates 12–15 show birds of paradise decorated hats and plume advertisements for 1911–12 and Plate 16 those being worn in 1921.

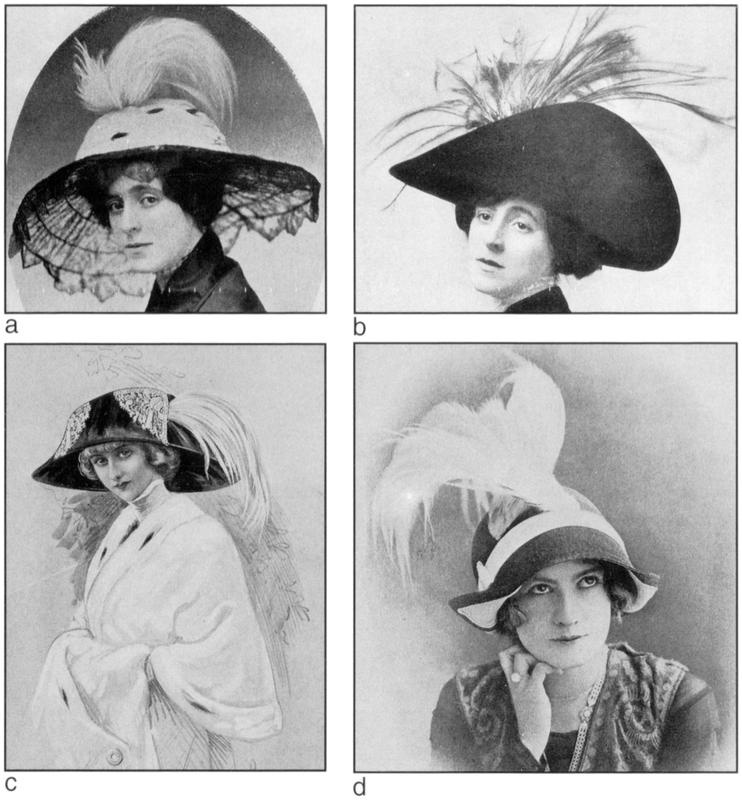

Plate 12: Hats decorated with birds of paradise appearing in 1911–12 fashion advertisements.

a. Dainty restaurant hat with black Chantilly lace, ermine (weasel) crown and bird of paradise mount.

b. Black velvet hat with large tomato coloured paradise.

c. Hat with silver lace corners and silver tassels with large white paradise plume.

d. French hat, navy in colour with white trim and natural paradise plumage.

Sources: Millinery, October, November, December 1911, June 1912. By permission of the British Library.86

![Black and white advertisements for paradise plumes. There are four photos; three of them are different plumes and the other is the ad itself with texts saying ‘Stuart Sons and Co. [line break] Old Change, London, E.C. [line break] Manufactories:-- London, Luton, Dunstable. [line break] Branches:-- Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle, Dublin, Sheffield.](i/page_86_1_online.jpg)

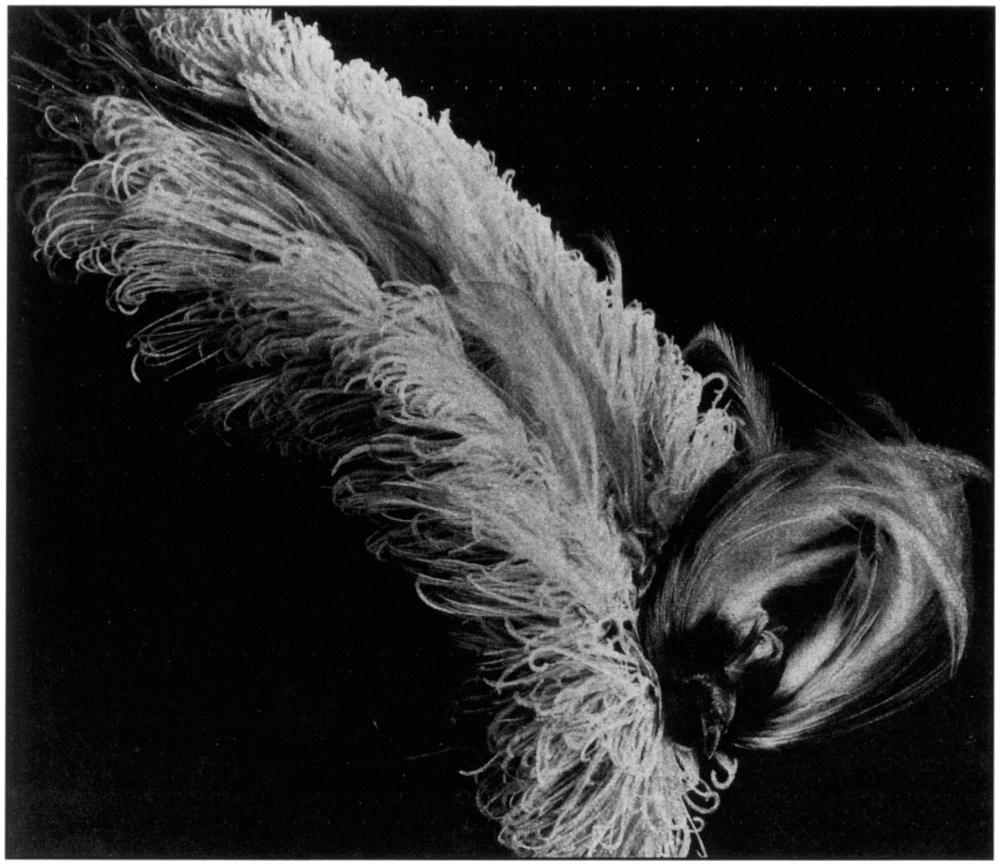

Plate 13: Advertisement for paradise plumes by Stuart Sons Company, London, 1912.

a. Dark paradise plumes 260 shillings each.

b. Light paradise plumes 247 shillings each.

c. Light paradise plumes 140 shillings each.

Source: Ladies wear Trade Journal, 1912, Vol. 2, No. 12. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 14: Blue ostrich headwear with paradise in centre and mounted bird of paradise.

Source: Millinery, January 1912. By permission of the British Library.87

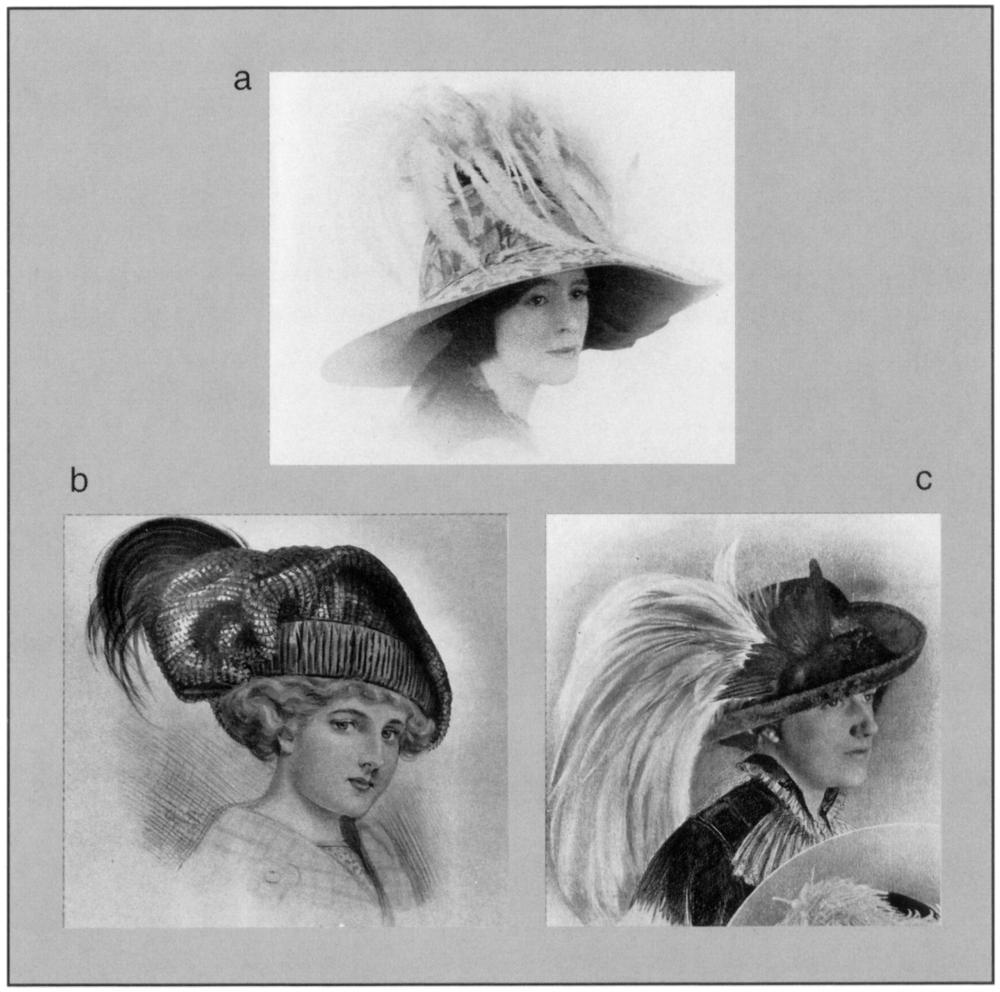

Plate 15: Hats decorated with birds of paradise appearing in 1912 fashion advertisements.

a. Painted silk picture hat, lined with olive crepe, with silk ribbon and imitation paradise plume.

b. Dark green tam with folded silk brim and large black paradise.

c. Black hat with rich yellow paradise mount.

Sources: Millinery, 1912, Vol. 2, No. 4; Millinery, 1912, Vol. 1, No. 11. Ladies Wear Trade Journal, London, 1912, Vol. 2, No. 9. By permission of the British Library.

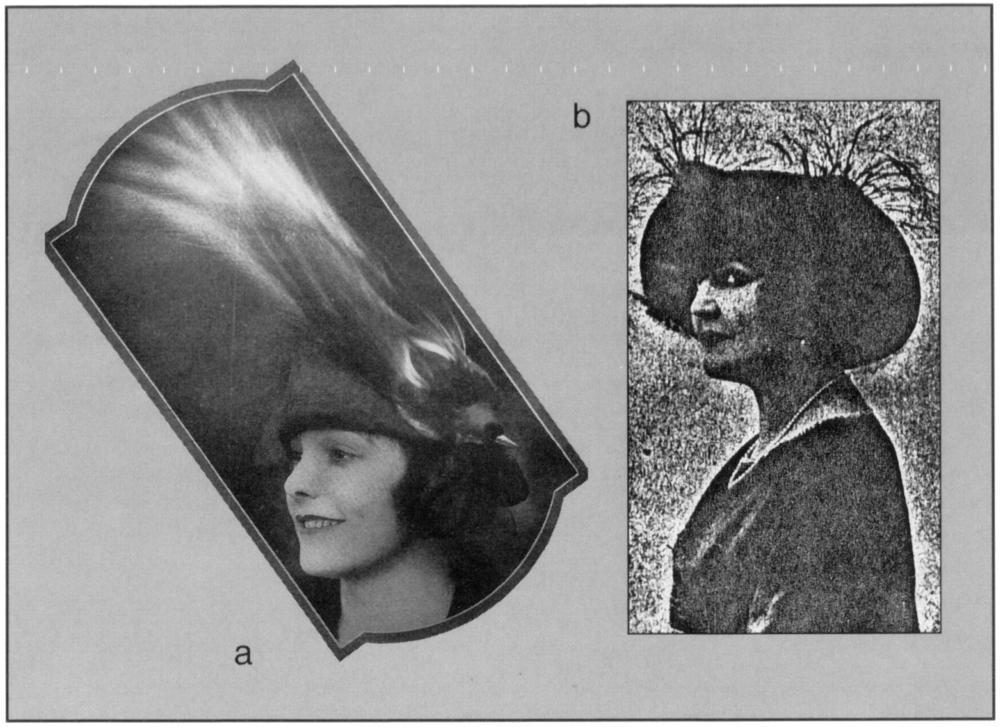

Plate 16: Hats decorated with birds of paradise appearing in 1921 fashion advertisements.

a. Spring wear hat trimmed with a natural bird of paradise.

b. A soft, black fabric hat with sprays of bird of paradise plumes set in tuffs.

Sources: The Millinery Trades Journal, London, 1921, March–April. The Queen, 1921, 29 January, 1921. By permission of the British Library.

88The number of birds killed to supply the Western world

It is difficult to compile meaningful figures and compare plume sales with season to season changes in fashion recorded in the fashion magazines due to the lack of consistency in the statistics on plumage imported into the United Kingdom and the United States during the plume boom. Insufficient categories were recorded, usually only ostrich and other ornamental plumage. The categories used also changed from time to time and included products other than plumes.5

Ostrich, egret and bird of paradise were the mainstays of the international feather trade. Before breeding programmes were established ostrich plumes came from Aden, Cape Colony, Egypt, Morocco, Natal and Tripoli. Egret plumes were mainly obtained from Venezuela, Brazil and Columbia, and bird of paradise plumes came from Dutch and German New Guinea as well as from Papua until 1908. Other species became fashionable for certain periods. For instance, in the 1880s and 1890s owl heads, small birds and hummingbirds perched on artificial flowers, and fragile goura sprays on dress hats became popular.6

Out of all the plume birds, birds of paradise fetched the highest prices. Table 5 gives the prices of the top twenty bird species on offer in London in 1913.

Table 5: The lower and upper prices of the top twenty bird species on offer in London in 1913.

| prices US $ | ||

| Greater Bird of Paradise1 | lower | upper |

| Light plumes: medium to large | 10.32 | 21.00 |

| medium to long, worn | 7.20 | 13.80 |

| slightly damaged, plucked | 2.40 | 6.72 |

| Dark plumes: medium to good, long | 7.20 | 24.60 |

| King Bird of Paradise | 2.40 | |

| Magnificent Riflebird | 1.14 | 1.38 |

| Rubra (Red) Bird of Paradise | 2.50 | |

| Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise | 1.44 | 1.80 |

| African Golden Cuckoo | 1.68 | |

| Cassowary plumes, per ounce | 3.48 | |

| Condor skins | 3.50 | 5.75 |

| Crown Pigeon heads, Coronatus | .84 | 1.20 |

| 89Crown Pigeon heads, Victoria | 1.68 | 2.50 |

| Egret (Osprey) skins2 | 1.08 | 2.78 |

| Emu skins | 4.56 | 4.80 |

| Argus Pheasant | 3.60 | 3.85 |

| Impeyan Pheasant | 2.50 | |

| Silver Pheasant | 3.50 | |

| Tragopan Pheasant | 2.70 | |

| Swan skins | .72 | .74 |

| Peacock necks, gold and blue | .24 | .66 |

| Golden Pheasant | .34 | .46 |

| ‘Green’ Bird of Paradise | .38 | .44 |

Notes:

1. The absence of Lesser Bird of Paradise skins seems an anomaly; perhaps they were grouped with the Greater Bird of Paradise by feather merchants as no one would want to buy something less than the best.

2. By 1913 the wearing of egret/heron plumes was no longer socially correct and this had led to a decline in the prices paid for these plumes.

Source: Hornaday 1913: 124–125.

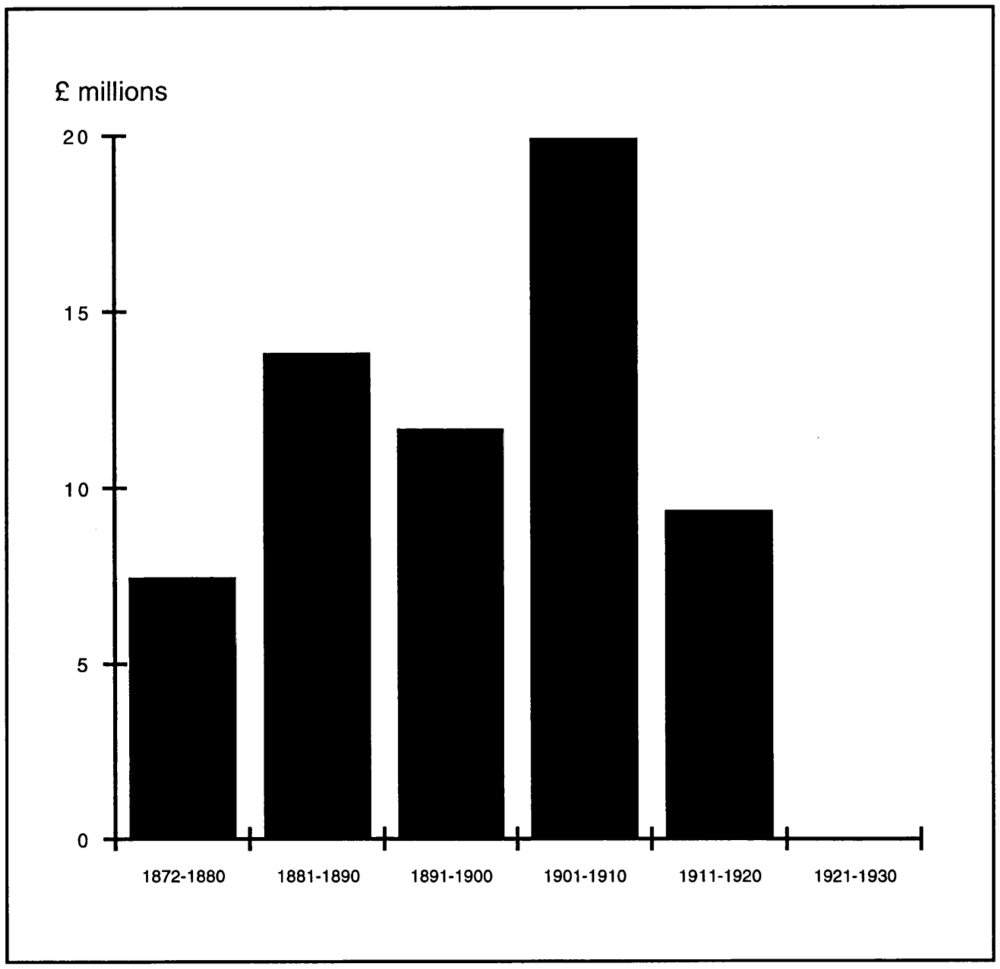

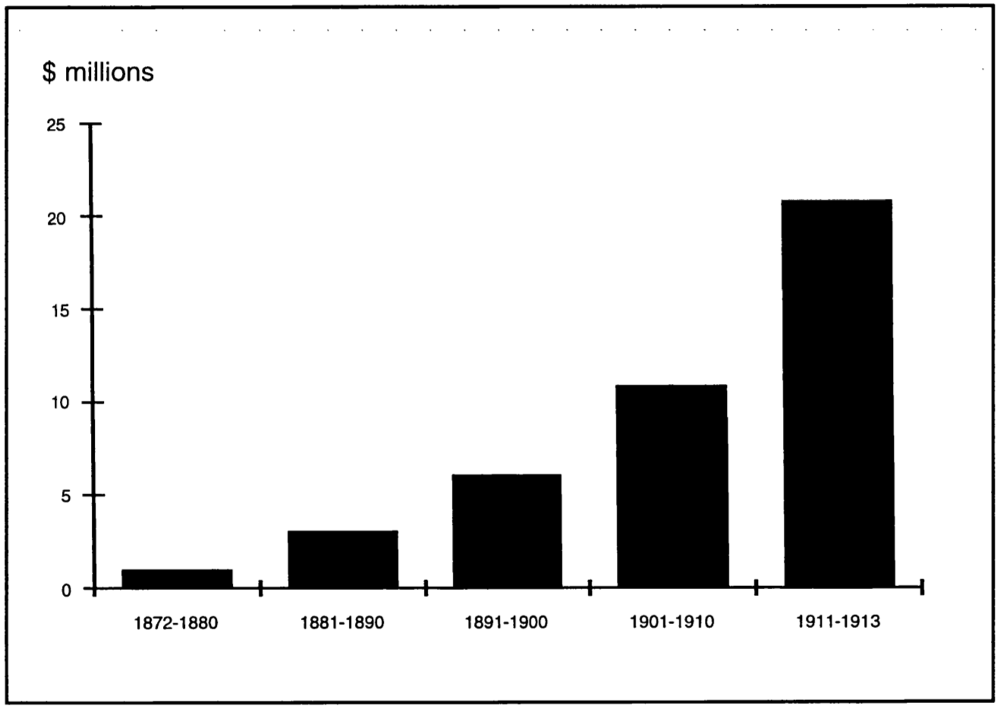

The feather imports into the United Kingdom from 1872 until 1921 show that there was a considerable demand for feathers in Europe by 1872 (Figure 18). The 1872–1913 figures for feather imports into the United States (Figure 19) illustrate that the fashion of feather wearing commenced earlier in the United Kingdom and Europe than it did in the United States. The feather exports from German and later the Mandated Territory of New Guinea from 1909–1922 (Figure 49) clearly illustrate the initial boom, the intervention of World War I and the resumption of the plume trade until it was outlawed.

Enormous numbers of birds were slaughtered for the feather trade. When one remembers the saying as light as a feather, 50,300 tons of feathers seems an incredible amount. This was the quantity of plumage to enter France between 1890 and 1929.7

Conservative estimates calculated from the weight of plumage sold indicate that some 155,000 birds of paradise were sold at London auctions between 1904–8.8 This is an average of more than 30,000 birds a year reaching London alone. Increasing quantities of plumes were purchased until the outbreak of the First World War. In 1912 one British firm received 28,300 skins in a single shipment. Ernst Mayr, the Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology at Harvard University, estimated that in a peak year some 80,000 skins were exported from New Guinea.9 Mayr’s estimate seems reasonable on the basis of the available statistics shown in Table 6. This table gives known figures for 1913. Better statistics will no doubt become available as more records are located.90

Figure 18: Feather imports into the United Kingdom from 1872 until they were prohibited in 1921.

Source: Based on Doughty 1975: Table 2.

Figure 19: Feather imports into the United States from 1872 until they were prohibited in 1913.

Source: Based on Doughty 1975: Table 3.91

Table 6: Estimated number of birds of paradise exported from New Guinea in 1913.

| region | value £ | number of skins |

estimated number of skins |

|---|---|---|---|

| German New Guinea | 50,277 | 16,691 | |

| Fakfak & Kokas | 40,000 | 8,000 | |

| Merauke | 25,000 | ||

| Hollandia | ?20,000 | ||

| Manokwari | 40,000 | 8,000 | |

| Sorong | ?5,000 | ||

| Estimated total about 80,000 | |||

Note

Nielsen (1930) states Merauke exported 25,000 birds valued at 2–2,500,000 kronen in the year before World War I. The Historic Section of the Foreign Office, London (1920) gives the export value of plumes from Merauke as 36,108 florins, using the 1918 exchange rate (see Figure 40 below), the sum of £3,610 for 25,000 birds seems far too low.

Sources: Historical Section of the Foreign Office, London 1920: 26; Cheesman 1938a: 41; Nielsen 1930: 228; Sack and Clark 1980: 156.

Although feather wearing has a long tradition in some parts of the world, never before in human history had so many birds and different species been slaughtered for plumage. The slaughter of some 300,000 albatrosses, gulls, terns and other birds on Laysan Island over several months in 1909 stands out as one of the fastest acts of carnage that occurred, but this was only one such case in the North Pacific. Laysan 92Island lies some 600 kilometres east of Midway Island in the Hawaiian Islands. The massacre was the work of twenty-three Japanese hunters hired by Max Schlemmer. They would have killed all the birds on the island if they had not been arrested by officers of the United States government. It was Schlemmer’s plan to ship the birds to Japan, thence to Paris which was the main market for seabirds from the North Pacific.10

The development of the conservation movement

From the early sixteenth century onwards, laws had been introduced in feudal England to protect certain game birds. This was done because guns were killing more of these birds than the old practice of falconry. Guns also had a marked effect on wildlife in other parts of the world. For example, the use of guns in the United States had by 1850 devastated the bison herds on the prairies and was leading to the extinction of the passenger pigeon.

After 1850, the sight of waving sprays of feathers and the use of wings and stuffed birds on hats upset sufficient members of the public in Europe and America to generate an outcry of outrage and disgust. The plight of many birds was also brought to the attention of the public by ornithologists, scientists, writers and church leaders who used both aesthetic and economic arguments against the plume trade. This opposition to the practice of feather wearing aroused sentiments which are still with us today.11

Activists aroused considerable sympathy for their cause by showing how some plumes were obtained by slaughtering parent birds at nesting colonies. They also explained how some of the birds being slaughtered ate insects which otherwise destroyed crops, whilst others, such as robins, were familiar to children from an early age as part of their cultural heritage. Middle-class urban Britons and Americans learnt about the unpleasant aspects of the feather trade from articles about these topics in local and national newspapers. This generated an interest in wildlife, especially birds, and was part of the ‘back to nature’ movement of the late nineteenth century.

Partly in response to this outrage, and also as a means of providing a regular supply, steps were taken to breed commercially some of the favoured plumage birds. In 1860–1900 the French Société d’Acclimatisation established breeding colonies of pheasants in France and similar projects were undertaken in England and the United States. Ostrich breeding colonies were established before the mid-1860s in the Cape Colony and North Africa and spread in the late 1860s to the United States, Europe, Australia and New Zealand.12 Ostrich breeding began in Australia in 1869.13

93In the late nineteenth century prizes were offered to those who could establish a successful egret farm. Some egrets/herons were reared in enclosures. Bird numbers were controlled and their plumage was clipped or plucked regularly. The French Société d’Acclimatisation successfully raised egrets in Tunisia in 1895. Other successes were reported from Argentina, Brittany, Ceylon, India and Madagascar. Despite such efforts the carnage of these birds in their breeding colonies continued.

By the 1880s the mass slaughter of wildlife as well as the widespread destruction of significant natural landscape and cultural monuments was causing concern. In an attempt to address this issue conservation movements were established in Europe and the United States. For instance in 1885 the Plumage League, which later became the Society for the Protection of Birds, was established in England and the Audubon Society was founded in the United States in 1886.

Initially the anti-plumage movement in the United Kingdom was restricted to socially prominent ladies and well-educated people and focused on the propriety of feather wearing. Three duchesses, three earls, a marquess, a viscount and three bishops were vice-presidents of the Society for the Protection of Birds. Servants and friends were discouraged from wearing plumes on moral and religious grounds. In this way the royal family came to support the Society for the Protection of Birds and King Edward VII gave it a royal charter in 1904. The support of Edward VII and Queen Alexandra for the Society meant that its members could no longer be viewed as a faddist minority.14

In 1881 protests had commenced in India over the killing of green parrots and other insect-eating birds for their plumes. This led to local governments being given some control over the possession and sale of plumage in the breeding season by the Wild Birds Protection Act of 1887. This proved to be an inadequate measure to control their slaughter. In 1900 a branch of the Society for the Protection of Birds was established in India. The growing outrage over the killing of birds which helped control insect pests resulted in the enactment of legislation prohibiting the shipment of wild birds from British India for the millinery trade in 1902. Despite this legislation, plume smuggling, especially of heron and kingfisher plumage, continued for many years.15

When the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire was founded in 1903, similar laws to those enforced in India were also implemented in many other British colonies, including Papua and the West Indies. In Papua it became illegal to hunt and deal in birds of paradise, goura pigeons and egrets/herons in 1908 (see Chapter 13). The hummingbird was the main species protected in the West Indies.16

94As well as establishing agencies to protect wildlife and preserve natural and cultural heritage, steps were taken to protect and preserve significant conservation areas. This led to National Parks being established. The first two National Parks to be declared were Yellowstone in 1872 in the United States and Tongariro in 1894 in New Zealand.17

Legislation was introduced when local species were threatened

In the 1860s there was public outcry over the slaughter of sea birds on Flamborough Head in Yorkshire in England. This led to the passing of an Act for the Preservation of Sea Birds. Despite this early legislation there was never again the same public concern in Britain over the slaughtering of wild birds for millinery purposes.

In England and France, the feather trade lobby successfully delayed the enactment of protective legislation because in each case the local populace was well removed from the slaughter. The London feather trade depended mainly on imported plumes. Some ornithologists thought that if British birds such as robins and swallows had been at stake, the British reaction might have been different. They concluded that the lack of response by the British public reflected their inability to become personally concerned about the brightly coloured birds they had never seen alive.18

The interests of the long established and lucrative Paris feather market held sway in France. This meant that the French government was willing to protect endangered species, but was not willing to ban hunting. In accordance with this policy, the millinery industry erected posters in their workshops prohibiting the processing of indigenous French birds and endangered overseas species.19

In the United States and Australia increasing publicity was given to the slaughter of sea birds and herons. Personal accounts of the havoc wrought by hunters in heron-breeding colonies in these countries greatly assisted the early passage of protective legislation. Moulted plumes obtained only one fifth to one sixth the price of ‘fresh’ feathers from slaughtered birds. Most heron ospreys and aigrettes were obtained by killing adult birds during the breeding season when the plumes were in their best condition. When it became known that adult herons were being slaughtered for their plumes even before their chicks could fend for themselves the public was outraged.

The following description of the destruction observed in a breeding colony in Florida after it had been visited by plume hunters in 1897 is one of many:95

… our party came one day upon a little swamp where we had been told Herons bred in numbers. Upon approaching the place the screams of young birds reached our ears. The cause of this soon became apparent by the buzzing of green-flies and the heaps of dead Herons festering in the sun, with the back of each bird raw and bleeding … Young Herons had been left by scores in the nests to perish from exposure and starvation.20

A disturbing photographic sequence prepared by A.H. Mattingley in 1906 of egret killing in the Murray Basin of New South Wales received widespread publicity in Australia, England and the United States (Plate 17). The photographs showed an undisturbed nesting colony and then the impact of plume hunters on these birds.21

The enormity of the slaughter became evident when it was recognised that this was happening in many other countries as well. Between 1899 and 1912 some 15,000 kilos of heron plumes were exported from Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela. More than 80 per cent of this amount came from Venezuela. In order to obtain one kilo of plumes some 800–1,000 small herons as well as 200–300 larger ones had to be slaughtered. These figures indicate that some 12–15 million small herons and 3 to 4.5 million large ones were killed for the plume trade in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela. Large numbers of herons were also killed in Florida. The growing outrage at this slaughter provided the political climate for the introduction of protective legislation. In the United Kingdom in 1899 Queen Victoria confirmed an order requiring British army officers to replace egret/heron plumes worn on regimental uniforms with ostrich plumes.22

Plate 17: Photographs of egrets killed for the plume trade being displayed on the streets of London in 1911. The placard carriers were employed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

Source: Hornaday 1913. Courtesy of Wildlife Conservation Society, New York.

96In Florida, herons were given some protection by the Florida Sea and Plume Bird Law of 1877, and this was strengthened in 1891 and 1901. In 1903 the first national bird reservation was set up on Pelican Island in Florida by Presidential Executive Order. Despite such measures it was widely apparent by 1910 that heron populations in Florida were continuing to decline. It was also recognised that this situation would not change as long as hunters could get as much as $80 an ounce for these plumes.23

The slaughter of herons in Florida and sea birds on the Atlantic coast was not easily ignored. In 1889 Senator Hoar of Massachusetts introduced a bill which restricted the trade in millinery plumes. It failed to pass. In 1900 the Lacey Act was passed. This legislation made bird protection a concern of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and prohibited interstate traffic in birds killed in violation of state laws. In 1910 the Shea-White Plumage Bill was passed in the State of New York and by 1911 this had curtailed millinery activities in New York city. The importing of wild plumage into the United States ceased when the Federal Tariff Act which included plumage import prohibitions became law on the 3rd of October 1913.24 This made the United States the second major feather importing country to prohibit such imports. Australia had done so by a proclamation issued under the Commonwealth Customs Act earlier that same year.25

The bird of paradise trade

In England members of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds believed that the fortnightly auctions of plumage in Mincing Lane spelt the end for many species, especially birds of paradise. Considerable publicity was given to Walter Goodfellow’s 1907 and subsequent descriptions of the slaughter of birds of paradise in Dutch New Guinea. He believed that the extinction of the Greater, Lesser, Red and Raggiana Birds of Paradise was imminent because hunters were beginning to hunt out the restricted ranges of these species.26 Sir William Ingram, an English newspaper man and bird enthusiast, decided to ensure the survival of the Greater Bird of Paradise by establishing a colony in the West Indies (see Chapter 9).

Fears about the imminent extinction of birds of paradise were offset by statements that the hunters only shot fully plumaged males and were not interested in drab females or sub-adult males who had the capacity to mate. This was the viewpoint expressed by the Dutch Minister in London when questioned about the wholesale slaughter of birds of paradise in Dutch New Guinea.27 97

Resistance by millinery trade interests

In Britain support from the upper classes for legislation to halt the importation of wild bird plumage for millinery purposes met organised resistance from British trade interests. Until 1921 every bill brought forward was blocked. The first bill aimed at controlling plume imports was introduced into the House of Lords by Lord Avebury in 1908, but it died in the Commons. A number of arguments were advanced as to why a plumage importation bill should not be passed. These included the loss of British jobs and trade for Britain, particularly if the feather trade was required to relocate on the continent. The British plume trade, like the administration of German New Guinea, requested that the industry should be retained as long as plumes were in fashion and in demand.

The feather trade stressed that it was concerned only with common birds and would do all in its power to save rare birds from extinction. Claims that birds were declining and disappearing from their old homes was in their view not the result of plume hunting but the impact of urban growth and agricultural development. It was also claimed by the trade that the bulk of hat trimmings was made up of artificial feathers, especially in the case of egrets/herons, but also in the case of birds of paradise. Plate 15a shows an advertisement for an imitation bird of paradise plume.

In 1917 the United Kingdom Board of Trade passed an importation of plumage regulation. This became the Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Bill in 1921. The failed 1908 Bill had proposed an end to feather sales. The 1921 Act only prohibited the importation of wild bird feathers; it did not prohibit their possession or sale.28 Consequently bird protection groups continued to seek restrictions which would prohibit the possession and sale of such feathers. The protectionists believed that customs seizures, and the ensuing small number of prosecutions, represented only a small proportion of the plumes entering Britain.

The plumage laws of the United States were more comprehensive than those of the United Kingdom. Anyone caught smuggling plumes in the United States faced heavy fines.29 One of the largest seizures of bird of paradise skins occurred at Larendo in Texas in January 1916. Abraham Kallman was caught smuggling 527 skins of the Greater Bird of Paradise into the United States valued at $52,700. He was fined $2,500 and spent six months in jail. The seized skins were donated to museums.30 98

Legislation in New Guinea prohibiting commercial hunting and exporting to supply the European plume industry

Internationally expressed conservation concerns have had both direct and indirect impacts on the protection of birds of paradise in New Guinea. When the market prices for birds of paradise increased during the late nineteenth century and boomed in 1908 different responses were made by the governments of Papua, German New Guinea and Dutch New Guinea. The government of Papua introduced legislation which prohibited commercial bird hunting in 1908 (see Chapter 13). This was the result of the efforts of the Society for the Preservation of the Wild Fauna of the Empire. It was the first legislation to prohibit the commercial hunting and export of birds of paradise plumes in any part of the island.

Hunting was permitted in German New Guinea, but profits were funnelled into the economic development of mainland New Guinea (Kaiser Wilhelmsland). A number of conservation measures including hunting permits, closed seasons and conservation areas were introduced as a means of ensuring not only the survival of birds of paradise, but also the continuation of hunting as long as it was profitable. The profits gained from the sale of bird skins were used to finance the establishment of a number of plantations in Kaiser Wilhelmsland (see Chapter 12). However the German public became outraged over the slaughtering of wild birds, and the introduction of legislation prohibiting the importation of wild bird feathers into both Australia and the United States in 1913 probably encouraged the German government to succumb to conservationist demands and introduce a one year ban on bird of paradise hunting in German New Guinea on a trial basis in 1914. Hunting resumed in the Mandated Territory of New Guinea after the war. It ceased in 1922 when the Australian government brought in legislation prohibiting the export of bird of paradise skins and other plumes.

By the mid 1890s concern was being expressed in the Netherlands about the number of birds of paradise being slaughtered in Dutch New Guinea.31 The complete ban on hunting imposed in Papua in 1908 may have influenced the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies to impose a hunting season, from the 1 April to 1 November each year. Hunters were also required to obtain an annual hunting licence costing 25 florins. This decree was made on 14 October 1909.32 On 16 August 1911 these restrictions were extended to the Sultanate of Tidore and areas under its jurisdiction.33 This move was probably to cover some legal loophole, as by then this sultanate was largely incorporated within the colonial state (see Chapter 6). The 1911 decree came into force on 1 May 1912.34 As in German 99New Guinea, the hunting season coincided with the time the birds were in plumage. This is not surprising as the economy of much of Dutch New Guinea, like that of German New Guinea, was dependent on plume hunting.35 In Dutch New Guinea, the Marind-Anim region near Merauke was the first area to be closed in 1922. When Britain passed its Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Bill in 1921, the plume trade went into decline. By the mid 1920s the prices paid for plumes had fallen and the boom was clearly over.36 Hunting in the rest of Dutch New Guinea was prohibited in 1924, with the exceptions of the western Muyu area which was closed in 1926, Digul in 1928 and Hollandia in 1931 (see Chapters 10 and 11).

The new plume trade in New Guinea

Although there was no longer a European market for plumes after the 1920s, an Asian market remained and a more extensive plume trade developed in Papua New Guinea. For example in the Fly River region of Papua New Guinea the buyers consisted of people from other parts of the country who had been brought into the region to work on government, prospecting and other projects. The local people were keen plume traders. R. Archbold and A.L. Rand report, whilst in the Fly River region in 1936, that their workers exchanged tobacco for plumes on several occasions. Plumes of those species not found at home were keenly sought by these workers. Such acquisitions were considered by their purchasers to be almost as important as the pay they would receive.37

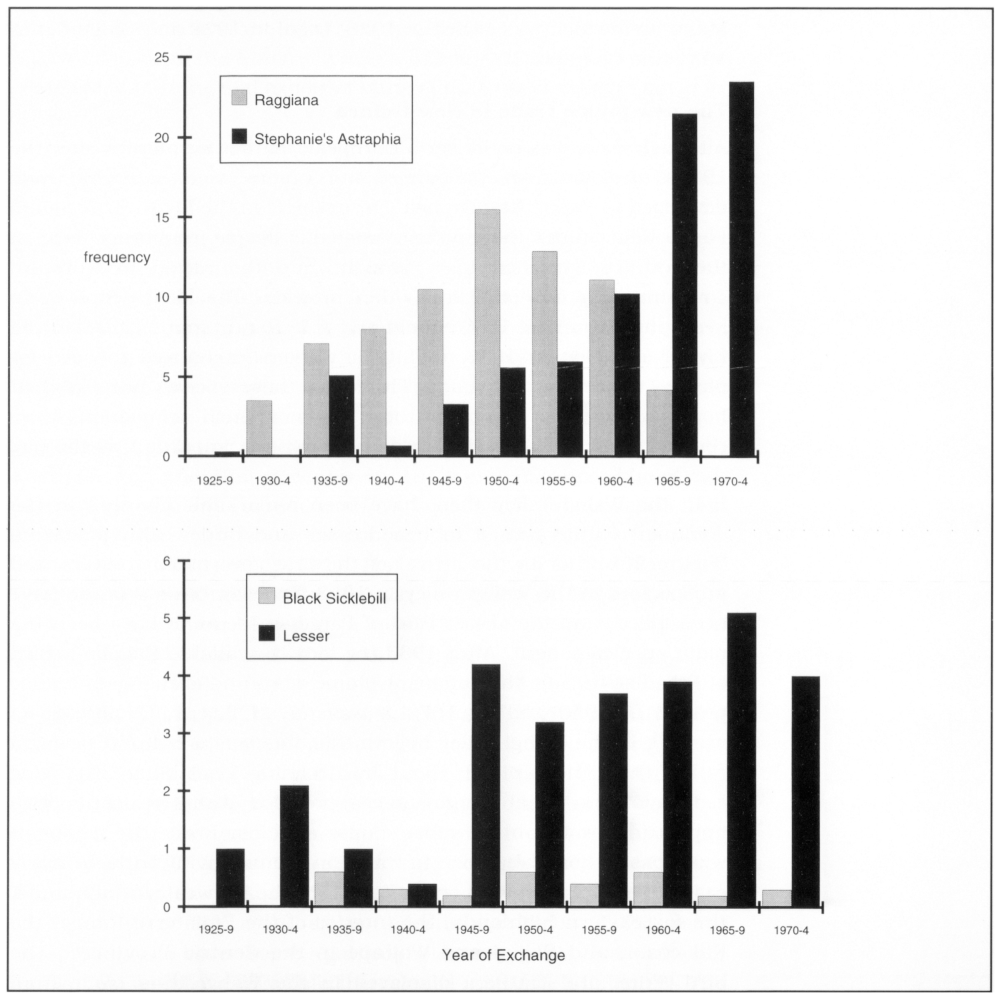

In the Wahgi valley there have been remarkable changes in the dominant feathers used in headdresses and bridewealth payments (Figure 20). Prior to the arrival of the first government officers and prospectors in the Wahgi valley in 1933 far fewer birds seem to have been killed, and the Lesser Bird of Paradise seems to have been the main species sought. After 1933 the locally available Raggiana Bird of Paradise became the dominant plume worn and exchanged. Its use peaked in 1950 and by 1970 it was out of favour. Ornithologists working in the Wahgi valley believe that this was a cultural decision rather than one brought about by declining availability. Changing economic and social circumstances provided Wahgi residents with opportunities to obtain more exotic species. From the 1950s it was possible for Wahgi men to travel on plume-buying trips, in many cases in association with employment, to the far western highlands, the far eastern highlands, the interior of the Finisterre Range, the Rai coast, and Sogeri and Woitape in the Central Province.38 The bird skins and feathers displayed in the Wahgi thus came from distant areas.

100By 1965 Stephanie’s Astrapia had become the most frequently worn and exchanged plume and this remains the case. Stephanie’s Astrapia are not common in the Wahgi valley forests. They are obtained by trade from other areas, especially the Jimi valley, as well as from parts of the Central, Enga and Morobe Provinces.39

Figure 20: In the period 1924–1974 there was a change in the main species of birds of paradise exchanged in Wahgi bridewealth payments.

Source: Based on Heaney 1982: 228.

The use of Black Sicklebill and Lesser Bird of Paradise plumes also increased after 1933 in the Wahgi valley (Figure 20B). The limited 101availability of the Black Sicklebill has made it the most valuable plume worn in the Waghi valley. By 1990 it was being sold for 40–100 kina a feather whereas Stephanie’s Astrapia was only worth 6–50 kina each. These expensive feathers are carefully stored in sealed containers to keep out insects and rats when not being worn on ceremonial occasions (Plate 21). The long tail feathers of the Black Sicklebill and Stephanie’s Astrapia are stored in bamboo tubes, whereas smaller plumes are kept in suitcases or other containers.41

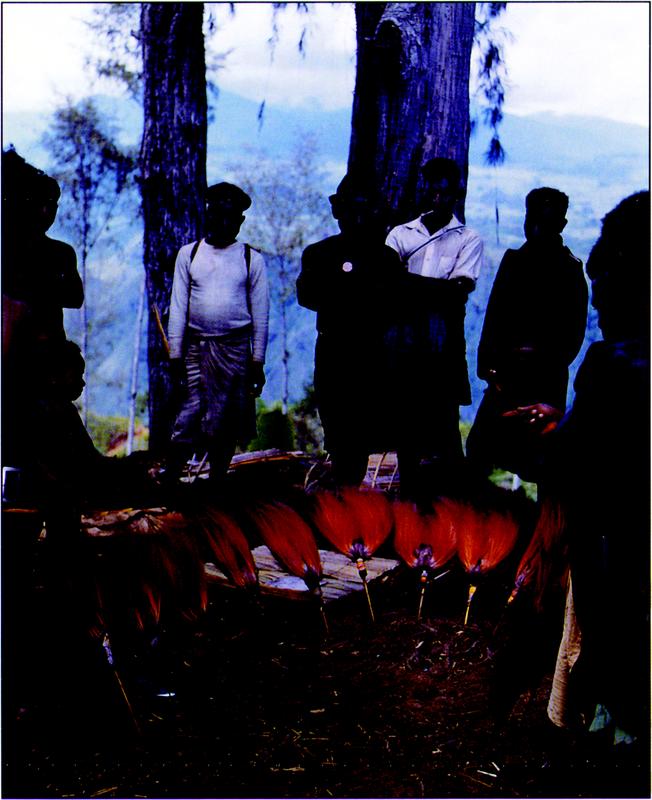

When the Raggiana began to decline in value in the Wahgi and Simbu valleys the plumes possessed by the people living in these valleys were traded to outlying areas. Plates 18–19 show Simbu plume traders at Yaramanda, a Kyaka Engan village on the northern slopes of Mount Hagen, trading Raggiana plumes in 1959. They had come to Yaramanda because they had heard that its residents were preparing to take part in a ceremonial exchange festival which would require them to wear Raggiana plumes. The traders assumed that they would find people there interested in buying their plumes.40 Plate 20 shows Engan men mainly wearing Raggiana plumes at a dancing ground in about 1970.

As a result of this new plume trade, and the increasing use of guns in Papua New Guinea, some plume supply areas have now been overexploited. For instance, prior to the time villagers began illegally using shotguns the Greater Bird of Paradise and Raggiana Bird of Paradise were common in the Ok Tedi area. By the late 1970s the Greater Bird of Paradise was still common in localities where shotguns had not been used, but the Raggiana appeared to have declined.42

In West Papua, A.M. Rumbiak43 estimates that between 150 and 200 Greater Bird of Paradise were caught in the Bomakia area inland of Merauke each year in the early 1980s. The rapidly inflating prices suggest that the numbers caught were declining. In 1972 a hunter obtained about 1,000 rupiah for a Greater Bird of Paradise skin in the Bomakia area, by 1973–78 the price had risen to 3,000–5,000 rupiah, by 1979–81 it was 5,000–7,000 rupiah and by 1982–3 the price was set at 10,000 rupiah (about 5 US dollars). The Greater Bird of Paradise (Paradisaea apoda) commanded the best price, but 1,000–2,000 rupiah were also paid for the more difficult-to-hunt King Bird of Paradise (Cicinnurus regius) and Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise (Seleucidis melanoleuca). The birds were bought by resident and itinerant traders and government officials in Merauke and Kouh. Some policemen also hunted as well as confiscated birds. In the early 1980s birds were illegally taken out of West Papua by traders, government officials, military personnel, boat crews and pilots.102

Plate 18: Simbu plume traders at Yaramanda on the northern slopes of Mount Hagen in Enga Province In 1959.

Plate 19: The Simbu plume traders (shown In Plate 18) display their Raggiana skins. Both photos by Ralph Bulmer, courtesy of Andrew Pawley.103

Plate 20: Raggiana are the dominant plumes worn by these Engan men at a dancing ground.

Photo: Courtesy of George Holten. Taken in about 1970.

Plate 21: Men from the Wahgi valley. The main bird of paradise plumes worn are those from Stephanie’s Astrapia and the Lesser Bird of Paradise. Also present are Black Sicklebill, Ribbon-tailed Astrapia and the King of Saxony Bird of Paradise.

Photo: Courtesy of George Holten. Taken in about 1970.

104Protective legislation in New Guinea

In the late 1920s, Ernst Mayr made a number of ornithological expeditions to New Guinea. He observed that no bird of paradise species seemed to have suffered any permanent harm, despite the slaughter of an appalling number of adult males during the European plume boom. This lack of impact had come about because only fully plumed, adult males were killed for the millinery trade.44

Their resilience was high because only a few mature males are needed in each generation for mating. This is possible as there are no pair bonds and males do not assist with nesting or the rearing of young. Males do not acquire full plumage until four to five years old and are capable of mating before it develops.45 Consequently the killing of fully plumed, adult male birds of paradise did not have the same devastating impact as the slaughtering of nesting herons.

This is also why birds of paradise have survived despite being hunted by New Guineans for thousands of years. The species most commonly used in headdresses in the Wahgi valley of Papua New Guinea were considered by ornithologists to be still common in surrounding forests in the 1960s. For this reason Thomas Gilliard recommended that traditional methods of hunting be permitted to continue.46 An attempt by a member of the House of Assembly to introduce legislation in 1965 that would allow the commercialisation of the bird of paradise plume trade was rejected.47

In 1966 the Fauna Protection Ordinance of Papua and New Guinea prohibited the killing of protected fauna, including all members of the family Paradisaeidae, namely birds of paradise, bowerbirds, manucodes, riilebirds and trumpetbirds. In 1968 the Ordinance was amended to stipulate that only Papua New Guineans can hunt or keep protected wildlife, and then only if they hunt them for traditional purposes using traditional weapons. The selling, buying or exporting of their skins was prohibited. An amendment in 1974 made it possible for anyone wishing to hunt these species for scientific purposes to do so after they had obtained written government permission. Further legislation was passed in 1976 to control the use of shotguns. The penalty for shooting birds of paradise with shotguns became 500 kina per bird. In 1979 Papua New Guinea became party to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This convention controls and regulates the international exportation and importation of all endangered fauna, including all Paradisaeidae.48

In Papua New Guinea the visual representation of birds of paradise is widespread in daily life. They feature on the national crest and flag, as well as on coins, stamps and business logos. Moreover, on 105ceremonial occasions and at singsing, traditional dancers continue to wear their gorgeous plumes. Few people are not moved by the splendour these plumes bring to such performances. On the basis of their beauty, as well as the part they have played in the country’s traditional ceremonies, birds of paradise have gained a symbolic role in expressing Papua New Guinea’s national identity. Today the illegal use of guns, the sale of plumes to other Papua New Guineans and habitat destruction threatens their long-term survival.49

In Dutch New Guinea the whole family of the Paradisaeidae was protected in 1931 by a decree proclaimed by the Governor-General.50 This legislation has been retained by the Republic of Indonesia and is still used to prosecute people caught trading in birds of paradise. This was the case, for instance, on the 16th of January 1992 when a man was caught in Jayapura trying to despatch birds to Java.51 Likewise in February 1985 a director of a local company was jailed for four and a half years for attempting to smuggle 163 bird of paradise skins out of West Papua through Sorong Airport.52

By 1963 the survival of the Greater Bird of Paradise in the Aru Islands was a matter of concern, as they were being threatened not only by hunting for a thriving plume trade, but also by a diminishing habitat.53 It is now illegal to export bird of paradise skins from the Aru Islands, but a clandestine trade continues. Wildlife officers now fear for the survival of birds of paradise in these islands as their numbers have dropped so low that they doubt whether the populations are viable. Kobroor Island has now been proposed as a nature reserve in order to protect the birds of paradise and other wildlife found in the islands.54

While some smugglers are caught others continue to flout the law, encouraged by the large profits to be made by despatching birds to Java.55 In the 1980s one skin was reported to be worth at least US$30 in Jakarta. Hunting for this trade on the more densely settled south coast of Japen has reduced the numbers of birds of paradise to be found there. Today tourists visiting West Papua wishing to see birds of paradise in their natural habitat are advised to visit the Raja Empat Islands, especially Waigeo and Batanta, and the sparsely settled north coast of Japen.56

In 1990 the Republic of Indonesia passed an Act concerned with the conservation of living resources and their ecosystems. This Act prohibits anyone from hunting and trading in birds of paradise. It also stipulates that protected species cannot be transferred from one part of Indonesia to another.57 The appropriate regulations governing the implementation of this Act are currently being prepared and these should remove any uncertainty about the use of protected species.106

Notes

1. Doughty 1975: 1–3, 8.

2. Wallace 1857: 414.

3. Doughty 1975: 3, 6–7,14.

4. Doughty 1975: 22, Table 1. In addition, P. Bleeker in 1856 reports figures for plume exports from Ternate for 1832–54. These are high for the 1830s, low for the 1840s and non-existent for the 1850s. Wichmann (1917: 389) doubts Bleeker’s figures. He suspects that many plumes were not registered, as M.D. and R. van Duivenboden was actively trading in plumes in the 1850s. It is possible that these figures relate to the export of village-prepared trade skins, which Alfred Russel Wallace reports declined in value from two dollars to sixpence in the 1850s (Wallace 1857: 414), and do not include arsenic-cured skins obtained by specialist hunters.

5. Doughty 1975: 24.

6. Doughty 1975: 18–22.

7. Doughty 1975: 124.

8. Doughty 1975: 30.

9. Gilliard 1969: 30.

10. Doughty 1975: 85; Hornaday 1913: 137–142.

11. Doughty 1975: 13, 31–156.

12. Doughty 1975: 7, 9, 18.

13. Scott-Norman 1992: 16.

14. Doughty 1975: 103, 116.

15. Doughty 1975: 61, 158.

16. Downham 1911: 103.

17. Nicholson 1987: 194, 221.

18. Doughty 1975: 80.

19. Brass in Vohsen et al 1913: 236 (German New Guinea colonial document).

20. Pearson 1897 cited by Doughty 1975: 64–5.

21. Anon 1910b: Doughty 1975: 65.

22. Doughty 1975: 12, 74.

23. Doughty 1975: 69–83.

24. Doughty 1975: 158.

25. Mackenzie 1934: 314; Osborn 1913.

26. Doughty 1975: 86.

27. Anon 1910a: 16.

28. Doughty 1975: 117.

29. Doughty 1975: 51–2.

30. Hornaday 1917.

31. Wichmann 1917: 388.

32. Staatsblad van Nederlandsch-Indie 1909, No. 497.

33. Staatsblad van Nederlandsch-Indie 191, No. 473.

34. Wichmann 1917: 388–90.

35. Wichmann 1917: 389.107

36. Cheesman 1938a: 40–44; Schoorl 1957.

37. Archbold and Rand 1940: 52-3, 143.

38. Bulmer 1962; Downes 1977; Gilliard 1969: 35–39; Healey 1980: 263; Hughes 1973.

39. Healey 1980. 1986, 1990; Heaney 1982; O’Hanlon 1989: 123; 1993.

40. Bulmer 1962: 16–19.

41. Bulmer 1962: 16; Deck 1990.

42. Bell 1969: 208: Coates and Lindgren 1978: 68–9.

43. Rumbiak 1984.

44. Gilliard 1969: 30.

45. Gilliard 1969: 31–2.

46. Gilliard 1969: 38–39.

47. Gellibrand et al 1966; Schultze-Westrum 1969: 302.

48. Fauna Protection Ordinance of 1966 and 1968 amendment; Fauna (Protection and Control) Amendment Act 1974; Fauna (Protection and Control) Amendment Act 1976; International Trade (Fauna and Flora) Act 1979; Spring 1977: 2.

49. Beehler 1993: Kwapena 1985: 154–5; Peckover 1978. The use of guns to shoot females and immature males also means that traditional conservation measures are being ignored (see Bulmer 1961: 6, 9).

50. Staatsblad van Nederlandsch-lndie 1931, No. 266.

51. Michele Bowe personal communication 1993.

52. Anon 1985.

53. Pfeffer 1963 cited by Cooper and Forshaw 1977: 176.

54. Muller 1990a: 133–4.

55. Anon 1990: Petocz 1989.

56. Muller 1990b: 51. 67. 71. 90–1.

57. Act of the Republic of Indonesia, No. 5 of 1990.108

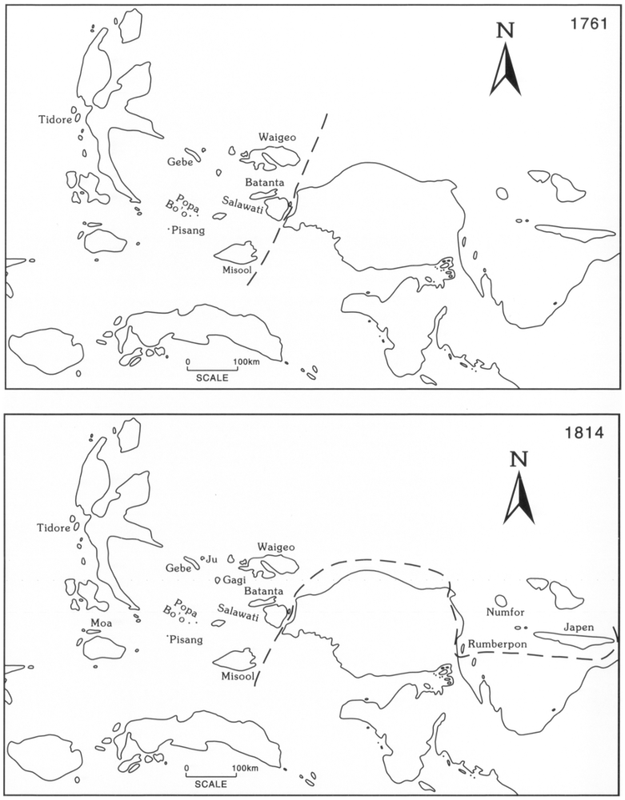

Figure 21: The respective areas of New Guinea designated under Tidore by the Dutch in 1761 and by the English in 1814 (designated areas are named).