9

Trade with the Aru Islands and

Trans Fly Coast of New Guinea

Introduction

When the Portuguese arrived in eastern Indonesia at the beginning of the sixteenth century the Seram Laut were not involved in collecting or carrying products for Asian markets.1 When the Dutch captured and destroyed Banda in 1621, some Bandanese fled and settled in the Seram Laut Islands. These Bandanese settlers encouraged the Seram Laut to supply Asian markets. From this time on the Seram Laut sought goods for these markets as well as continued their traditional trade. For the next 20 years Seram Laut traders, including those from Gorong Island, were making regular trading expeditions to the Aru Islands.

Dutch vessels first visited the Aru Islands in 1636 and soon returned to carry out trade. By 1645 the Dutch East India Company had effectively closed these islands to other traders, including those from the Seram Laut Islands. They did this by inducing several local chiefs to give exclusive trade rights to the Company who in turn allocated these rights to the Dutch residents of the Banda Islands. At first, damar, pearls, turtle shell and bird of paradise skins were the main exports from the Aru Islands.2 Trepang did not become a major trade good until the 1720s.3

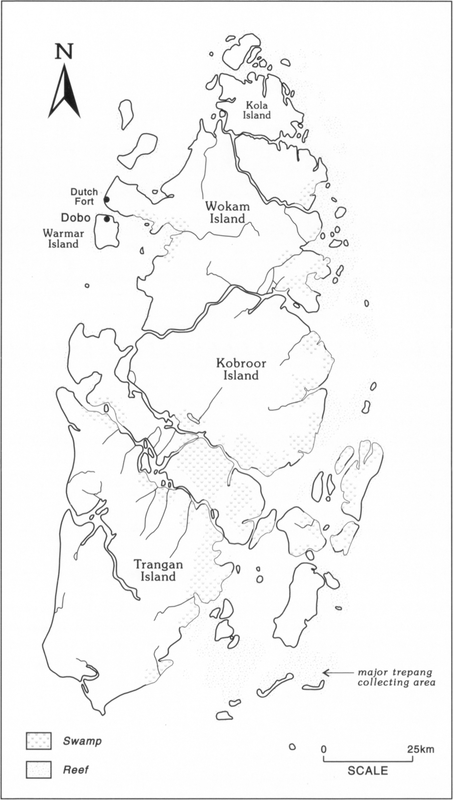

The Dutch consolidated their position by building a fort on Wokam Island (Figure 35) and establishing missions. In the early 1700s neat little stone churches with their construction dates inscribed over their doors were built in all the main villages in the western Aru Islands.4 These Dutch missionaries in the Aru Islands carried out the first mission activity in New Guinea and its offshore islands. Their work predates the Woodlark Island mission in what is now Papua New Guinea in 1847 and the Mansinam Island mission in Doreri Bay in Dutch New Guinea (now West Papua) in 1855.

When trepang became a profitable trade item in the 1720s the Dutch traders from the Banda Islands sought this product in the Aru Islands. 154The market was soon dominated by A. J. van Steenbergen, a resident of Banda, who had seven trading vessels. Smaller traders were unable to compete with his operation and his crews usually obtained most of the lucrative, and less bulky, black trepang. There was no profit in the plentiful, easily prepared white variety.5

Also available in the Aru Islands were long nutmegs, which were generally considered inferior to the round ones from Banda. Although previously sought by the Seram Laut and other traders, the Aru nutmegs were of little interest to the Dutch traders from Banda, the home of cultivated nutmegs. The Dutch also rejected the Aru nutmegs because most were worm-ridden and had been gathered before they were ripe.6

As a result of the exclusive trade rights given to Dutch traders from Banda by the Dutch East India Company, the Aru and Kei islanders were prohibited from supplying sago to Banda, because the Bandanese were required, in the interests of Dutch trade in the archipelago, to live on Javanese rice. When this proved unviable, steps were taken to revive the traditional Aru and Kei sago trade.7

Prior to 1645 when the Dutch East India Company gained a trade monopoly in the Aru Islands, Seram Laut traders were making regular trading expeditions to these islands. When the Seram Laut found that they were denied access to the Aru Islands, they sought alternative sources. It is proposed here that this is when the Seram Laut traders extended their trading sphere eastwards to the New Guinea coastline adjacent to Torres Strait. They subsequently withdrew from this coastline and reestablished their trade with Aru when the Dutch withdrew from the Dutch East Indies during the Napoleonic wars. The period of proposed Seramese influence on the Trans Fly coast of New Guinea thus dates from 1645 until the 1790s when the Dutch lost control of the East Indies.

When the British gained control of the East Indies during the Napoleonic wars, they took little interest in the Aru Islands. They just gave the Dutch businessmen from Banda time to collect their debts before destroying the fort on Wokam Island and removing the garrison.8

The treaty agreements signed in Europe in 1814 allowed the Dutch to regain control of the East Indies. When they returned, they abandoned the monopolistic practices of the disbanded Dutch East India Company which had restricted inter-island trading. This allowed the Seram Laut to resume trade with the Aru Islanders and, as a result, cease their trade with the distant Trans Fly coast of New Guinea.

There are enough tantalising indications of Seram Laut contact with the Trans Fly coast from about 1645 until 1790 to warrant serious oral testimony studies in the Seram Laut Islands and the Trans Fly coast of New Guinea. Archaeological surveys of sites dating to this period in this 155part of New Guinea should also be rewarding, but may not be possible because access to some of the known sites is restricted to initiated men. However, this restriction may change.

Indications of Seram Laut contact with the Trans Fly region from about 1645 until 1790

There are linguistic indications of contact between the Seram Laut Islands and the people of the Trans Fly region. It is only on the eastern tip of Seram and in the Seram Laut Islands that a knife is called turika, tari or other variants of this name.9 The use of comparable words to ask for iron by Torres Strait Islanders in 1792 indicates that they were then familiar with such names for knives. The parts of western New Guinea visited by Seram Laut traders before extensive European contact still use similar words for knives. They are known as turi in areas such as Lobo in Triton Bay, Namatote Island off Triton Bay and Wuaussirau in Etna Bay. At Onin a knife is known as tani, see Table 9 and Figure 28.

In 1792 Captains Bligh and Portlock of the Providence and Assistant, and crew member Matthew Flinders, observed that Erub and Damut Islanders in the eastern part of Torres Strait were demanding iron from passing ships. Flinders visited the area again in 1802 and experienced the same demands.10 The names for iron being used by these islanders were toore-tooree, tureeke or toorik. Other early nineteenth century visitors also report that iron was commonly called turik or tulik. Table 9 and Figure 30 indicate where these names and their variants are used in Torres Strait and the New Guinea mainland.

The Gizra, Agób and Idi people of the Trans Fly claim that they possessed metal implements long before the London Missionary Society established a mission on Dauan Island in 1871.11,12 While it is possible that many of these implements were obtained as trade items from trepangers or pearlers who began working in Torres Strait in the 1830s and 1860s respectively,13 this does not explain how Torres Strait Islanders were demanding iron as early as 1792.

The Seramese names for iron include mamóle and other cognates. Mammoosee and malil are other words used to refer to iron by the Gizra of the Trans Fly and the Mabuiag and Erub Islanders of Torres Strait. They may also have a Seramese origin.14

The proposed activities of Seram Laut traders in the Trans Fly region from 1645 until 1790, along with local trade routes, would also explain how glass beads dating to this period came to be present in archaeological sites found upriver of Kikori in the Gulf of Papua. The best dated of these finds is a bead identified as having been manufactured at Murano in Italy between 1650–1750. It was excavated from archaeological deposits which have a general date of 1630–1770 156at Kulupuari, an old village site on the banks of the Kikori River, some 16 kilometres upriver from Kikori.15

The presence of these beads at Kulupuari is not so surprising when it is known that this site is situated on the main trade route by which pearl shells from Torres Strait were traded inland to the highlands. The route was from Torres Strait to the Papuan Gulf, thence up the Kikori River, taking an eastern tributary called the Sirebi, over the slopes of Mount Murray to Samberighi, on to the Erave area of the Southern Highlands, and thence to the Wahgi valley of the Western Highlands (Figure 34).16

Table 9: Words for knife and iron used in eastern Seram, the Seram Laut Islands, the Torres Strait Islands and New Guinea.

| word | Seram and NW New Guinea |

Torres Strait Islands | Trans Fly and adjacent mainland areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| toerik | Warn, Seram | ||

| toolick | Erub & Mer Is. | ||

| toore -toore | Erub Is. | ||

| toori | Massid Is. | ||

| toorik | E. Torres Strait Islands |

||

| toorree | Damut, Erub & Mer Islands |

||

| tuka | Gah, Seram | ||

| tulik | Erub & M er Is. E. Torres Strait Islands |

||

| tuni | Onin | ||

| tureeke | E. Torres Strait Islands |

||

| turi | Seram, Namatote Is., Lobo, Etna Bay |

Bine | |

| turika | Seram | Saibai Island | Buji, Mawatta, Kiwai |

| turikata | Dabu | ||

| turiko | Mabudauan, Tureture, Mawatta | ||

| turito | Keffing Island Seram Laut Islands |

||

| turuko | Tirio (lower bank of Fly River), Sisiami (Bamu River) |

Notes:

1. Marind-anim (Tugeri) knew the word turik, but it meant woman. They therefore had their own word wokerike, see Haddon (1912 (4): 129).

2. The Malay and Javanese words for knife and iron are pisau and busi respectively for Malay and lading and wusi for Javanese (Wallace 1986: 616).

3. Stokes (1846) reports meeting Torres Strait Islanders on Restoration Island, on the eastern coast of Cape York Peninsula, in June 1841 who kept asking for toolic (Moore 1978: 323).

4. The word for knife throughout the Lake Murray-Middle Fly area is suki. This is also the origin of the group name Suki. Suki could be a cognate of the Seram Laut words (Mark Busse personal communication 1991).

Sources:

Flinders 1814 (1): xxii, xxiv; Flinders 1814 (2): 109; Hughes 1977: 24; Jukes 1847 (1): 133; Laba in Contribution 2; Ray in Wollaston 1912: 332–333; Stokhof 1982a: 62; Wallace 1986: 616.157

Impact of the Seram Laut traders

More than three decades before the Seram Laut trade commenced, Torres passed through Torres Strait in 1606 and reported no local interest in knives or iron. It is proposed here that the Seram Laut traders who came from 1645 to 1790 sought damar from the people of the Trans Fly. Their interest in the south coast of New Guinea, rather than the Torres Strait Islands or northern Australia, would explain why Cook and Banks found no indication of Seram Laut activity or knowledge of metal at Cape York in 1766.17

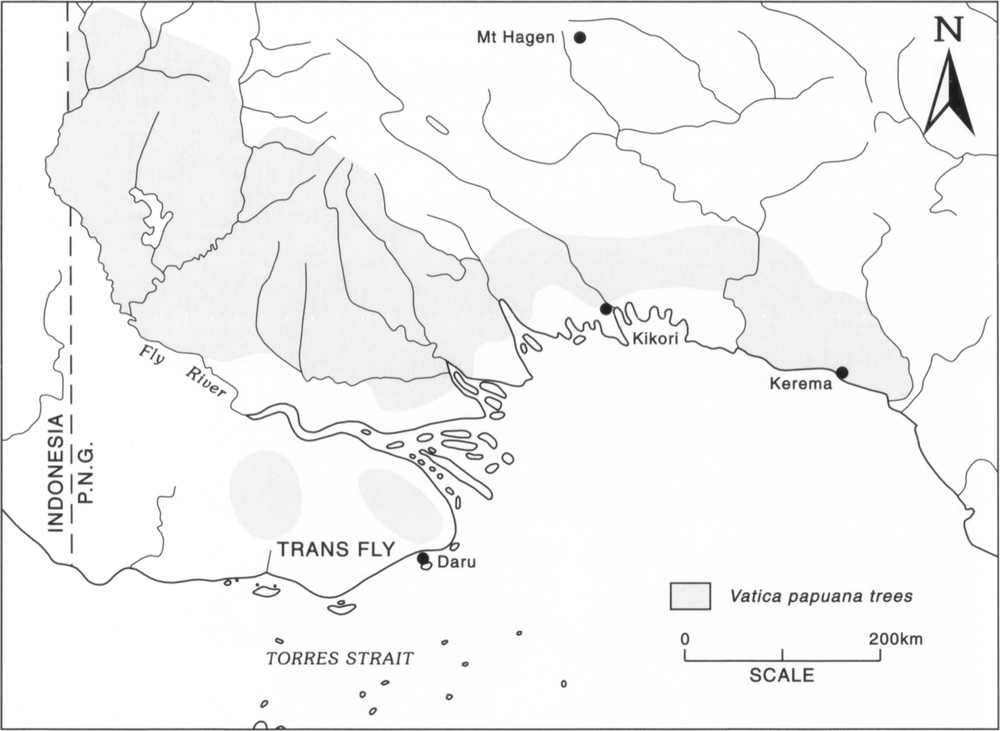

Trepang, which gave rise to a subsequent eastern Indonesian interest in the northern Australian coastline, from Wellesley Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria to Melville Island, as well as the Kimberley Coast, did not become an important trade good until the 1720s,18 some 70 years before the Seram Laut interest in the Trans Fly lowlands ceased. Although there is a time overlap, there is no indication that Asian trepang collectors were ever active in Torres Strait. Certainly no sites comparable to the Makassarese sites found in northern Australia were discovered during an archaeological survey of the Torres Strait Islands.19 In the seventeenth century damar was an important Indonesian trade good, as it was the main means of illumination used throughout the archipelago. In fact the word damar means torch in Malay. Torches were made by placing pounded resin in palm leaf tubes. The use of damar for lighting continued until mineral oil became available. Other uses of damar included coating and sealing pottery.20 The resins used 158originated from the bark of Agathis species (kauri pine/Manila copal) or the sapwood of dipterocarps, especially Vatica papuana.21 The distribution of Vatica papuana trees in southwest Papua New Guinea is shown in Figure 31.

The Seram Laut contact provides an historical origin for the Sido-Hido hero traditions of southwest Papua. Roy Wagner examines these and related traditions in Contribution 1 of this volume.

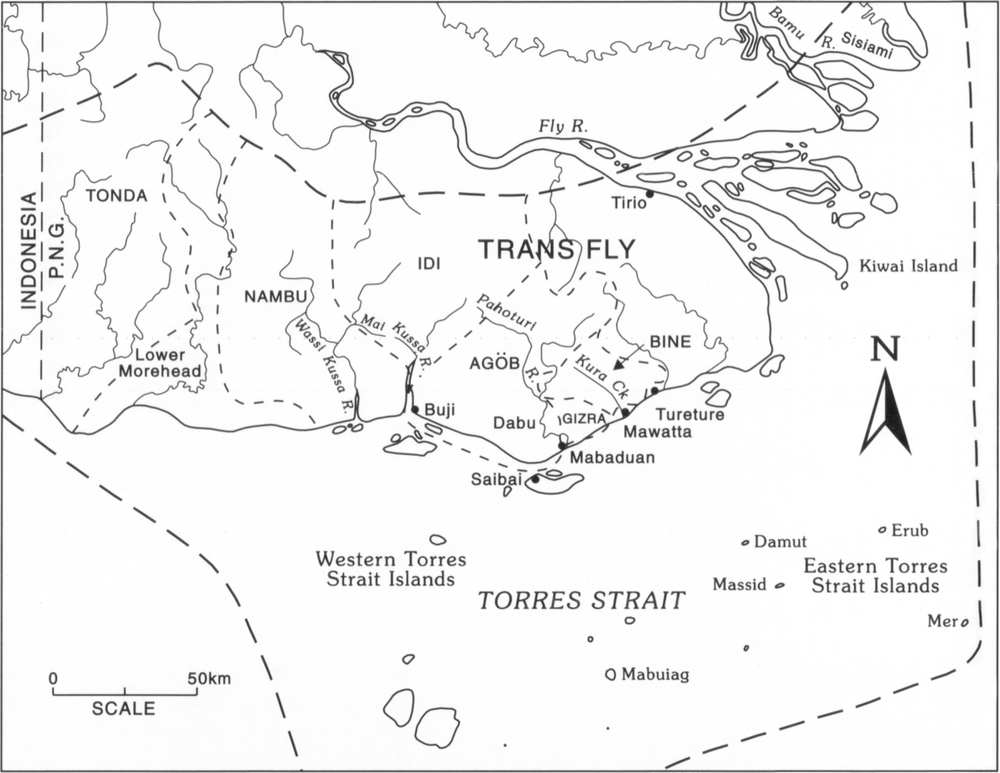

Figure 30: Where turik, tulik, tuni and other variants are used or known as words for knife and iron in Torres Strait and the Trans Fly.

The Trans Fly people claim that they had books before the arrival of Europeans (see Billai Laba in Contribution 2 of this volume). This could be explained by the Indonesian trade practice of giving documents to appointed headmen in the main villages where they traded. For instance, P. Drabbe22 reports that amongst the Mimika these were called surat, a Malay word meaning letter. These surat may have served 159the same function as the village books used during the Australian administration of Papua New Guinea. The traders could have recorded useful information, including the local people who were trustworthy and those who had failed to fulfil agreed contracts made with the traders.

The people living in the Wassi Kussa River mouth area as far east as Kura Creek (Figure 30) claim that their ancestors had books (buk) which had not been obtained from Europeans. Here it should be noted that buku is the Malay word for book. These books are reputed to have been held at Basir Puerk, near Mabudauan at the mouth of the Pahoturi River, and other depositories (see Billai Laba in Contribution 2).

Figure 31: The distribution of Vatica papuana trees in southwest Papua New Guinea.

Source: Zieck 1975, 1978.

The buk held at Basir Puerk near Mabudauan has not survived. This is not surprising. Who could have preserved them under the conditions that the Gizra, Agob, Idi and other mainland people faced at the time of European contact? At that time their main concern was to avoid 160being found and killed by the Tugeri (Marind-anim) raiders. The coastal stretch had been abandoned and people were hiding inland. The first European visitors to the mainland saw more of the Tugeri raiders than the traditional inhabitants of the area. This explains why the government initially thought the unoccupied land at Mabudauan had no local owner.23

In the early 1890s, Sir William MacGregor visited an inland Dabu (Gizra) camp where one group was living in hiding from the Tugeri. He found some 200 people living in four temporary shelters.24 These were made of tree bark which was tied onto a framework of curved wooden poles. The continuous use of temporary shelters would not have ensured the preservation of any sacred possessions.

Knowledge about pre-European metal, the buk and the remains of boats located at the headwaters of the Mai Kussa and Pahoturi River is considered sacred lore by the Gizra, Agob and Idi people of the Trans Fly (Figure 63). The planks, chain and anchor of a boat located on the banks of a creek flowing into the Mai Kussa are probably not those of an Indonesian prau, but rather the remains of Captain Strachan’s vessel abandoned during an attack by the Tugeri in 1884.25 The local inhabitants were probably mystified as to how it appeared during their absence and it is not surprising that the remains are locally referred to as Noah’s Ark. A similar mysticism has built up around the buk and these are often called Bibles.

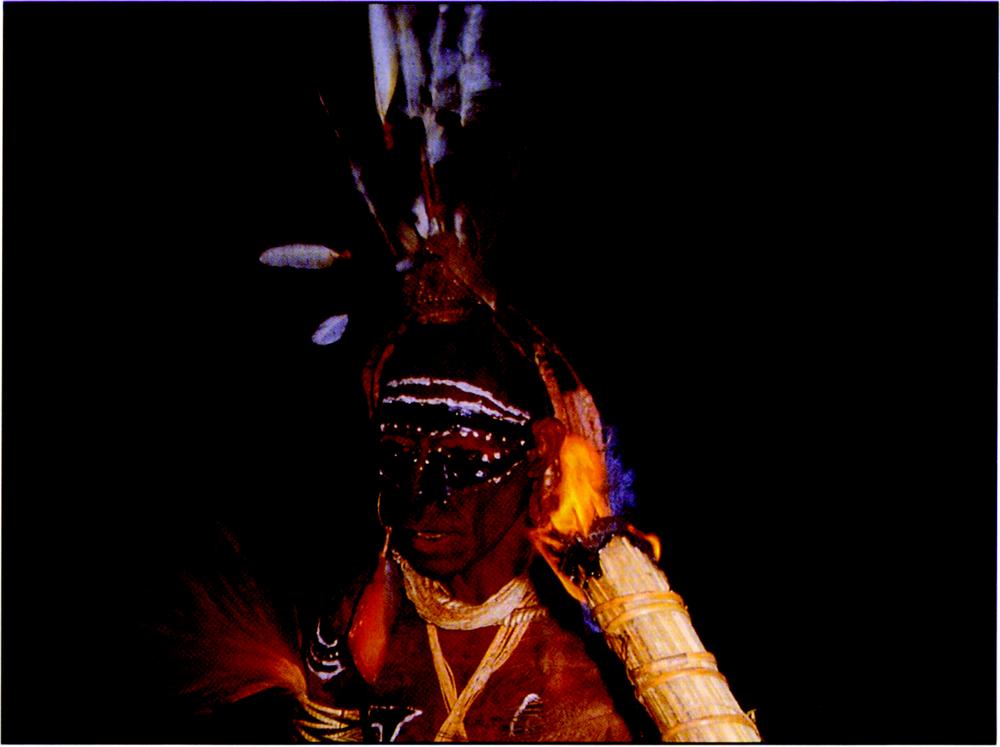

Plate 24: A resin torch illuminating a Kamula dancer wearing Raggiana plumes at Wasapepa village in Western Province.

Photo: Courtesy of A.L. Crawford.

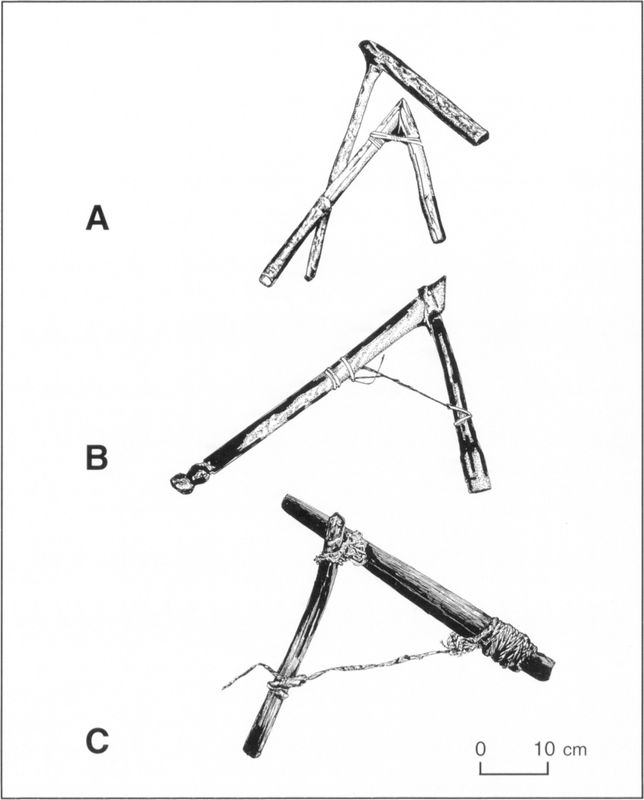

161Contact with the Seram Laut would have led to the introduction of new crops, such as tobacco and sweet potatoes, as well as new technologies. The use of damar (tree resin) to make light and a new tool for working sago pith are examples of technological changes which were probably introduced by this contact. Plate 24 shows a resin torch being used by a Kamula dancer at Wasapea village in Western Province. Figure 32 shows examples of the special tool used to scrape sago pith which is found in Borneo, the Moluccas and the western part of New Guinea. Figure 33 indicates where this tool is used in New Guinea.

Tobacco is an American plant introduced by the Portuguese to the Moluccas. Tobacco seeds and the practice of smoking were taken from the Moluccas to New Guinea through contacts resulting from tribute payments or trade. In the Raja Empat Islands, Onin, Kowiai and Mimika areas of West Papua most of the words used for tobacco are clearly derived from tambaku, tambako or tabako.

In southwest Papua New Guinea the names used for tobacco appear to be derived from sukuba, see Table 10 and Figure 34. Sukuba and its variants seem to be derived from the word tobacco, with the replacement of t by s and interchangeable b’s, p’s, g’s and k’s. There is a set of words derived from sukuba between the mouth of the Fly and the international border, and then a distribution of related words in the languages spoken in the Strickland River, Palmer River and Ok Tedi areas to the north.26

Tobacco was probably introduced to the Torres Strait Islands and adjacent New Guinea mainland when the area was visited by Seram Laut traders from 1645 to the 1790s. The earliest observation of tobacco being used in this area was in the Torres Strait Islands in 1836.27

Table 10: List of names for tobacco derived from sukuba used in southwest Papua New Guinea and Torres Strait.

(Place names are given in lowercase, languages in capitals)

| name | location/language |

|---|---|

| choka | Cape York, Australia |

| kuku | ELEMA; KOIARI; KOITA; MOTU; Purari Delta |

| sakaba | Dabu, AGÖB |

| sakoba | GOGODALA |

| sakop | Yende, AGÖB; Eastern Torres Straits Islands, MIRIAM |

| sakopa | Domori, KIWAI; GOGODALA; Tagota, SUKI; TIRIO; WABUDA KIWAI |

| sakpa | AGÖB; IDI; TONDA |

| sakup | Jibu, GIDRA |

| sakupa | Buji, AGÖB; KIWAI |

| sauk | Bolivip, FAIWOL |

| saukabata | Strickland River162 |

| sekupe | Palmer River |

| sikube | Anmat, Ok Tedi; AWIN |

| sikupa | Eastern Torres Straits Islands, MIRIAM |

| sogob | Eastern Torres Straits Islands, MIRIAM |

| soguba | KIWAI |

| sok | Ok Tedi; Star Mountains |

| sokoba | Moie (? Goi), NAMBU; Suki Creek, SUKI |

| sokop | Yende, AGÖB |

| sokopa | Dorro, IDI; Kibuli, AGOB; Eastern Torres Straits Islands, MIRIAM |

| soga | Lake Kutubu; lower Waga River |

| sogu | Lake Kutubu; lower Waga River |

| soku | Samberighi |

| suguba | GIDRA; Kunini, BINE; GIZRA; Saibai, MABUIAG; Western Torres Straits Islands, MABUIAG; KIWAI; Tureture, SOUTHERN KIWA; |

| sugub | Western Torres Straits Islands, MABUIAG |

| suk | Star Mountains |

| sukoba | Suki Creek, SUKI |

| suku | BAMU KIWAI; Foraba district, upper Purari; Goaribari Island; Mount Murray; Omati River; Paibuna River; Sisiame, BAMU KIWAI; Umaida Turama River; upper Kikori River |

| sukub | Eastern Torres Straits Islands, MIRIAM; Western Torres Straits Islands, MABUIAG |

| sukuba | above Everill Junction; Daudai, GIDRA; Karigara, IDI; KIWAI; Kunini, BINE; Mawatta, SOUTHERN KIWAI; Saibai, MABUIAG; Semariji, TONDA; Eastern Torres Straits Islands, MIRIAM; Western Torres Straits Islands, MABUIAG |

| sukufa | GOGODALA; NAMBU |

| sukup | GOGODALA |

| sukupa | Dibolug, Wassi Kussa R., NAMBU; Warubi, IDI |

| sukuva | Keriaki, NAMBU |

Sources: Laba in Contribution 2; Riesenfeld 1951.163

Figure 32: A special tool is used in Borneo, the Moluccas and the western part of New Guinea to scrape sago pith. In the eastern part of New Guinea wood-working tools are used for both sago scraping and wood working. Examples from Seram, New Guinea and its offshore islands are shown here.

A. South Seram, collected before 1889.

B. Aru Islands, collected before 1913.

C. Waira village, Kikori area, PNG.

Sources: Höpfner 1977: Plate 10; Rhoads 1980: Plate 111–9). Drawings by Anton Gideon.

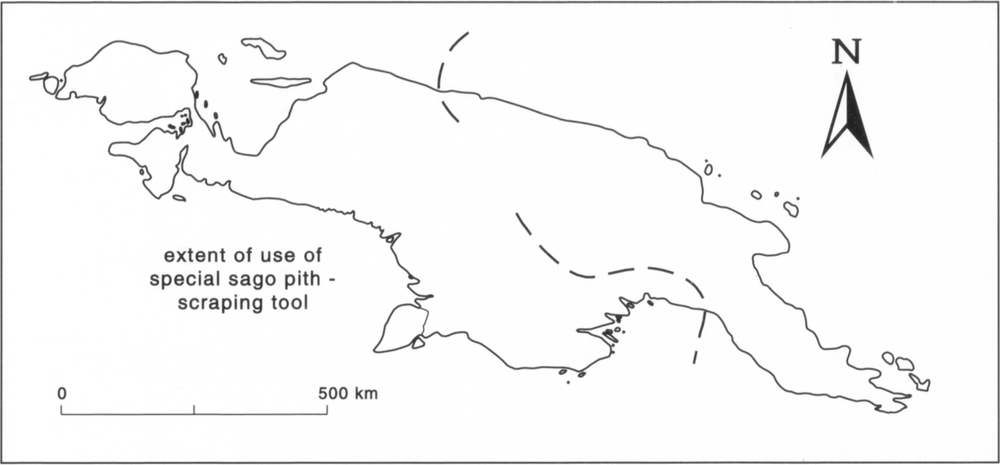

Figure 33: Where the special sago pith-scraping tool is used in New Guinea.

Source: Crosby 1976. Reproduction courtesy of Archaeology in Oceania.

164East of the Fly River mouth the name sukuba becomes shortened to suku. The distribution of this name suggests that tobacco was traded up tributaries of the Kikori River to Samberighi and Lake Kutubu in the Southern Highlands. In the Papuan Gulf, coastal villagers probably gave gifts of tobacco to the Motu of the Port Moresby area to take back on their return hiri (trading voyages). This would explain the distribution of tobacco and the name kuku (derived from suku with an interchange of s to t then k) as far east as Suau.28

Figure 34: The distribution of names for tobacco derived from sukuba, sokoba and sakob in southwestern Papua New Guinea and Torres Strait.

165In addition to tobacco, it is likely that sweet potatoes were introduced to southern New Guinea at this time. During the seventeenth century these tubers became a popular food in the Moluccas.29 Tom Dutton30 has produced a fascinating set of related words not only spoken on the Bird’s Head but also in the area inland from Kikori to the Southern Highlands; see Table 11. In view of the ensuing impact that this high-yielding crop had on highland societies, the possibility of this as a route of introduction deserves further study.

Table 11: Set of names for sweet potato used in the Bird’s Head and region inland from the Kikori area in Papua New Guinea

(Place names are given in lowercase, languages in capitals)

| name | location/language |

|---|---|

| West Papua | |

| sesiayuro | Iria, W. Kamarau Bay |

| sersiabura | Asienara, W. Kamarau Bay |

| sie | lha, E. Bintuni Bay |

| sibu | lha, E. Bintuni Bay |

| sijapido | Inanwatan, W. Bintuni Bay |

| siäp | Borai, NW. Cendrawasih Bay |

| Papua New Guinea | |

| siyofulu | SAMO, EAST STRICKLAND |

| siyafuu | KUBO, EAST STRICKLAND |

| siyobulu | TOMU, EAST STRICKLAND |

| siyabul | HONIBO, EAST STRICKLAND |

| siapuru/siabulu | BIAMI, BOSAVI |

| siapuru/siabulu | KALULI, BOSAVI |

| siapuru/siabulu | KASUA, BOSAVI |

| siapuru/siabulu | FASU, WEST KUTUBU |

| siyabulu | BIAMI, BOSAVI |

| siapuri | BAIAPI |

| supuru | FASU, WEST KUTUBU |

| tia | SAU, WEST CENTRAL |

| dia | POLOPA, TEBERAN |

| diani | Barika, TURAMA |

Source: Dutton 1973: 439.

166Dobo, Aru Islands

When the Dutch regained the East Indies from the British in 1814 the monopolistic trade practices of the disbanded Dutch East India Company were abandoned. Dobo (Dobbo) on the small island of Warmar in the Aru Islands (Figure 35) quickly became the largest trading centre in the New Guinea region. By the 1830s traders mainly from Seram Laut and Makassar were carrying out a profitable trade there. The low prices of their goods excluded Dutch competition.31 Alfred Russel Wallace visited Dobo in 1857.32 His observations provide an interesting account of the trading activities taking place at this time.

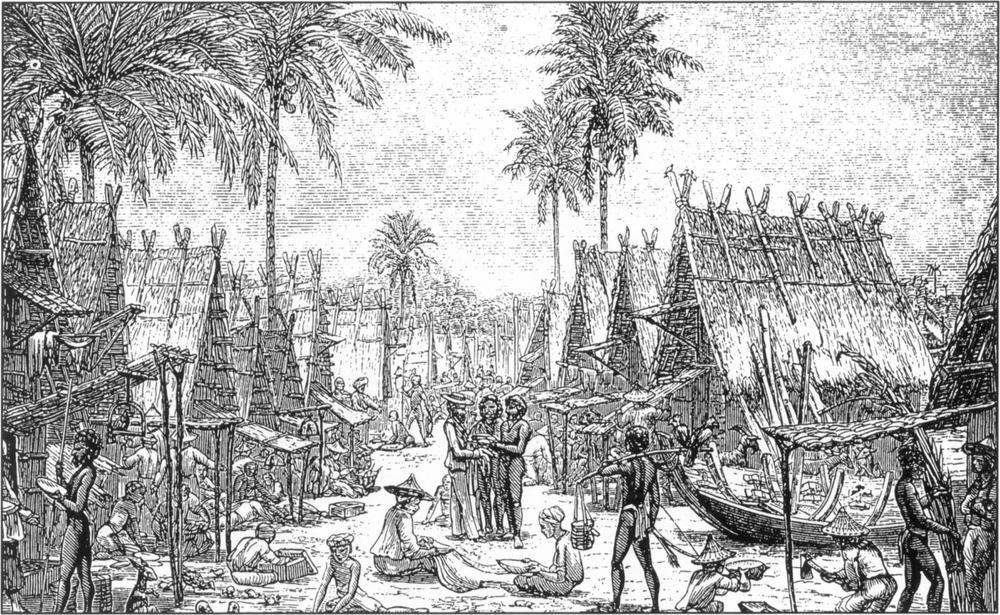

For part of each year Dobo was a flourishing trading settlement with a population of some 500 people; see Figure 36. The Indonesian traders came once a year. They arrived in January with the west monsoon and departed in July with the east monsoon. In 1857 there were about 100 small praus, mostly from Gorong, but also some from Seram and Kei. In addition there were 15 large praus from Makassar, a few Chinese traders and one Dutchman. Wallace travelled from Dobo to Makassar by prau; the journey of more than 1,600 kilometres took nine and a half days.33

Dobo was established on a sandspit at the entrance to a channel. Its three rows of houses were exposed to healthy sea breezes. Instead of establishing a house, some traders preferred to live on their boats or camp on the beach. The traders anchored their praus on the sheltered side of the sandspit. Some pulled their praus up on the beach. There they were safe from worm damage and could be prepared for the homeward journey. Apart from trading at Dobo, the traders also sent small vessels to trade on the eastern side of the Aru Islands.34

Some 20 people died at Dobo in 1857. Among the traders there was a Moslem priest who superintended the funerals and called the faithful to prayer at a small mosque on Friday. The Chinese showed their superior wealth by erecting granite tombstones, imported from Singapore, for their dead.35

Some traders married Aru Island women. Wallace36 reports that men from Makassar, Java and Ambon had each married an Aru wife and that a few traders had decided to become permanent residents.

Traders who used houses either built a new house or repaired their old one.37 Once the traders were established, the inhabitants of the Aru Islands brought their wares. These were displayed at each house. They brought bundles of smoked trepang, dried shark’s fins, pearl shells, turtle shell, edible bird’s nest, pearls, ornamental woods, timber and birds of paradise. All these products had been collected throughout the Aru Islands during the preceding six months. The trepang and pearl shell provided the bulk of the Aru exports. Damar was no longer a major export. Some foodstuffs such as fish, turtle and vegetables were also traded. 167The Greater Bird of Paradise (Paradisaea apoda) and the King Bird of Paradise (Cicinnurus regius) were the first birds of paradise described by natural historians. The Greater Bird of Paradise skins would have come from the Aru Islands (see Figures 15 and 16). There was also some transshipment of products obtained in New Guinea by Seram Laut traders through Dobo. In this way Wallace obtained skins of the Lesser Bird of Paradise in the Aru Islands.38

Figure 35: The Aru Islands.

168In return the Aru Islanders desired German knives,39 choppers, swords, muskets, gunpowder, tobacco, gambier,40 plates, basins, crockery, cutlery, handkerchiefs, sarongs, cloth from Sulawesi, white English calico, American unbleached cottons, arack, gongs, small brass cannons and elephant tusks. If the particular item desired was not forthcoming, the Aru Islander would move on to display his wares at the next house. Some stores contained tea, coffee, sugar, wine, biscuits, and the like for the supply of the traders, and others were full of fancy goods, china ornaments, mirrors, razors, umbrellas, pipes and purses with which to take the fancy of the wealthier Aru.41 Some 3,000 boxes each containing 15 half-gallon bottles of arack, comparable in strength to West Indian rum, were consumed annually in the Aru Islands.42

Figure 36: Dobo on Warmar Island in the Aru Islands during the height of the trading season in 1857.

Source: Wallace 1986 (first published 1869).

The availability of these imported goods led to socioeconomic changes. For instance, by 1826 bridewealth payments in the Aru Islands always included imported gongs, elephant tusks, crockery and cloth, plus other items, and this was still the case when Wallace was there in 1857.43

169That year the bulk of the exports from the Aru Islands went out on 15 Makassarese praus. The cargo of one of these was worth about £1,000, whereas other small praus from Seram, Gorong and Kei together took goods worth about £3,000. The total exports from Dobo in 1857 were some £18,000.44 Some of the pearls, mother-of-pearl shell and turtle shell ultimately reached Europe, whereas the trepang and edible bird’s nest were solely destined for China.45

This trade attracted pirates. In February 1857 Wallace46 reports that a prau arrived at Dobo which had been attacked. One man on board had been wounded. Everyone was alarmed. The Aru Islanders feared attacks on their villages and the capture of their women and children as slaves. The Indonesian traders were concerned that their small praus trading on the eastern side of the islands would be plundered. Although the pirates were not expected to attack Dobo, sentries were posted and fires were lit on the beach to guard against a surprise night attack.

The pirates were said to be from Soolo (Sulu)47 and had some Bugis amongst them. The Indonesian traders were justified in their fears, as the pirates on this occasion did plunder some of the small praus trading on the eastern side of the Aru Islands. A crewman of one of these praus was killed. Pirates had last visited the Aru Islands eleven years previously.

In 1857 Dutch influence was minimal in eastern Indonesia. Makassar was guarded by a 42-gun Dutch frigate but this vessel, together with a small war steamer and 3 or 4 tiny cutters, was insufficient to deter piracy in the region.48 The Aru Islands only received a visit from a commissioner based in Ambon about once a year. He toured the islands, hearing complaints, settling disputes and taking prisoner any serious offenders.49

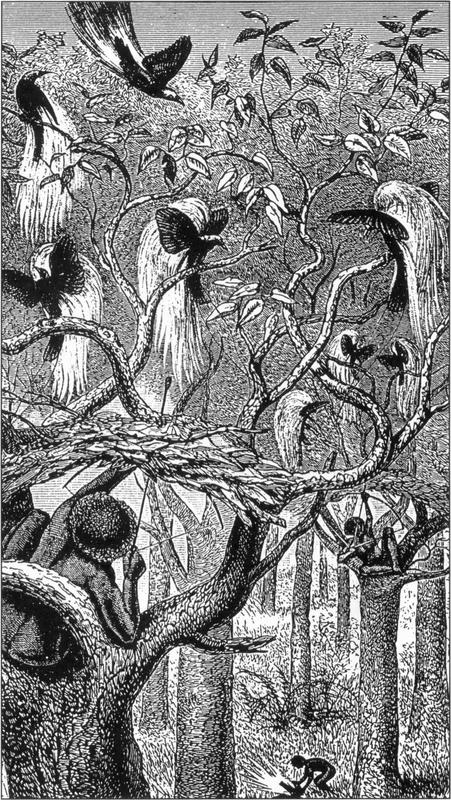

Bird of paradise hunting and trade on the Aru Islands

Each year the Aru Islanders killed large numbers of fully plumed adult males of the Greater Bird of Paradise (Paradisaea apoda) and traded them at Dobo. Some of these skins were taken home by Europeans as curiosities, making this species the second bird of paradise to be taken to Europe. The first was the Lesser Bird of Paradise obtained by the Spanish in the Moluccas in 1521. The trade skins of the Greater Bird of Paradise described by Linnaeus lacked feet, hence his tongue-in-cheek name, Paradisaea apoda, ‘the footless bird of paradise’.

Although J.O. Helwig and Herbert de Jager50 had described the courtship behaviour of the Greater Bird of Paradise and the hunting methods of the Aru Islanders in the seventeenth century, their work was not widely known. Wallace was the first naturalist to observe and make known the courtship behaviour of this bird.51

170 Wallace was disappointed that the Greater Bird of Paradise was not in full plumage when he was in the Aru Islands for six weeks (March to May) in 1857. The trade skins he was offered were clearly last year’s rejects; Wallace was dismayed that fresh skins were not available as those remaining from last year were all dirty and poorly preserved.52 The islanders told him that the birds would be at their best from September to October.53 Although he dearly wanted to observe and obtain specimens when the birds were in full plumage, Wallace was unable to delay his departure as the last prau returned in July. To be present in September to October would require him to spend a full year in the Aru Islands.

The Greater Bird of Paradise did start to display whilst Wallace was there, so he was able to observe their display and the hunting methods of the Aru Islanders on Kobru (Kobroor) Island; see Figure 37. The male birds congregated and displayed at favoured trees. The same trees were used for generations. The islanders used bows and arrows to shoot the birds from hides in the tree tops. Some hunters used arrows which had large blunt conical caps which killed the birds without damaging their plumes and skins;54 others preferred pointed arrows. When the birds fell to the ground, they were collected by a boy who accompanied the hunters.55

When O. Beccari, an Italian naturalist who was collecting birds of paradise, visited Dobo from February to July in 1873, he obtained only seven specimens of the Greater Bird of Paradise in full plumage. All of these had been prepared in the local way, which smoked and deformed the specimens. Beccari wanted freshly killed birds which he could prepare as natural history specimens. He was dismayed to observe that many of the skins offered were in various stages of moulting and that a high price was paid for each skin. The Makassarese traders were then paying 15 half-gallon, square bottles of arack (an actual case of arack), worth 16 to 18 shillings, for each skin. He was told that at least 3,000 bird of paradise skins had been exported from Dobo in 1873.56,57

By the turn of the century Dobo was no longer a great market place; pearling was now the main activity. However, the export of bird of paradise skins continued and Sir William Ingram, the founder and first editor of the Illustrated London News, became so concerned about the extinction of the Greater Bird of Paradise that he set about establishing a colony of 44 of these birds on Little Tobago Island in the West Indies in 1909. The birds survived and in 1958 there were about 35 birds on the island.58171

Figure 37: Aru Islanders shooting the Greater Bird of Paradise (Paradisea apoda) in 1857.

Source: Wallace 1986 (first published 1869).172

Notes

1. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 100.

2. Earl 1840: x.

3. Macknight 1986: 69.

4. Earl 1853: 110; Kolff 1840: 180, 189.

5. Wright 1958: 18–20.

6. ibid.

7. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 219, 222; Ellen 1979: 69.

8. Wright 1958: 45.

9. Stokhof 1980, 1981, 1982a: 62, 1982b.

10. Flinders 1814 (1) xxii, xxiv; Flinders 1814 (2): 109.

11. See Billai Laba’s Contribution 2 in this volume.

12. The first London Missionary Society teachers were established on Darnley (Masig) and Dauan Islands in 1871–2 (Whittaker et al. 1975: 347).

13. Haddon 1912 (1): 15: Hughes 1977: 32; Macknight 1976: 40; Yonge 1930: 165–7.

14. Wallace 1986: 616; Billai Laba in Contribution 2 this volume; Flinders 1814 (2): 109.

15. Rhoads 1984.

16. Crittenden 1982; Hughes 1977.

17. Beaglehole 1962 cited by Hughes 1977: 21.

18. Macknight 1986: 69.

19. Vanderwal 1973.

20. Ellen and Glover 1974: 357, 375.

21. Jack Zieck personal communication 1979.

22. Drabbe 1947–8: 256–7.

23. Later the Mowatta (Mawatta, Kiwai) claimed the land, but when the Dabu(lai) (Gizra) tribe was discovered, they declared themselves to be the real owners. Both groups were brought to Mabudauan and the government ended their claims (MacGregor 1892: 42). However, recent events indicate that the Gizra are still dissatisfied with the outcome (Mark Busse personal communication 1990).

24. MacGregor 1892: 43.

25. Strachan 1888: 47.

26. The sukuba set was noted by Tom Dutton in 1974 when preparing a manuscript on tobacco in New Guinea. He remarks (Dutton n.d.) that the most satisfactory explanation of this set would require contact between Indonesians and the Trans Fly, something hitherto undocumented.

27. Brockett 1936 cited by Riesenfeld 1951: 80.

28. Riesenfeld 1951.

29. Ellen 1987: 38.

30. Dutton 1973: 439.

31. Kolff 1840: 155, 196; Brumund 1853.

32. Wallace 1986: 432–6, 442–3.

33. Wallace 1986: 485–6.173

34. Wallace 1862b: 131; 1986: 476.

35. Wallace 1986: 483.

36. Wallace 1986: 454.

37. In 1826 the traders had new houses built each year. This was necessary as the old ones were burnt at the end of each season by the Aru Islanders so that they would be paid to build new ones the following year (Kolff 1840: 197).

38. Wallace 1857: 415.

39. One German knife was worth 3 half-pence (Wallace 1986: 433).

40. Gambier is a yellowish catechu obtained from a woody vine, Uncaria gambir, and is used for chewing with betel nut or tanning and dyeing.

41. Wallace 1986: 435, 442.

42. Wallace 1986: 485.

43. Kolff 1840: 162; Wallace 1986: 485.

44. Wallace 1986: 485.

45. Wallace 1986: 409.

46. Wallace 1986: 440–2.

47. Wallace (1862a: 154) states they were from Magindano. This was a general term for such raiders used by the Sulawesi (Warren 1981: 160–1). Their presence upset Wallace’s plans as it meant that no one ventured far from home until they were sure the raiders had left. This situation required Wallace to spend two months in Dobo without seeing a bird of paradise.

48. Wallace 1986: 219, 455.

49. Wallace 1986: 444.

50. Stresemann 1954: 273.

51. Gilliard 1969: 216; Stresemann 1954: 281.

52. Wallace 1986: 435.

53. In the Mapi River area of West Papua (Figure 38), the male Greater Bird of Paradise moults at this time (Rumbiak 1984: 8).

54. The use of blunt-ended arrows, which stun rather than pierce the flesh, remains a widespread way of shooting birds of paradise in New Guinea (see e.g. Barth 1975: 40).

55. Wallace 1857: 413–4; 1986: 446–7.

56. Whittaker et al 1975: 232.

57. In the 1850s Wallace reports that village-prepared trade skins fell in value from two dollars to six pence (see Chapter 5). Subsequently these skins must have regained some of their former value, as in 1873 Makassarese traders, presumably supplying Asian markets, were willing to pay 16–18 shillings per skin.

58. Gilliard 1969: 401, 413.