8

The massoy, trepang and

plume trade of Onin, Kowiai and Mimika

(Southwest New Guinea)

Introduction

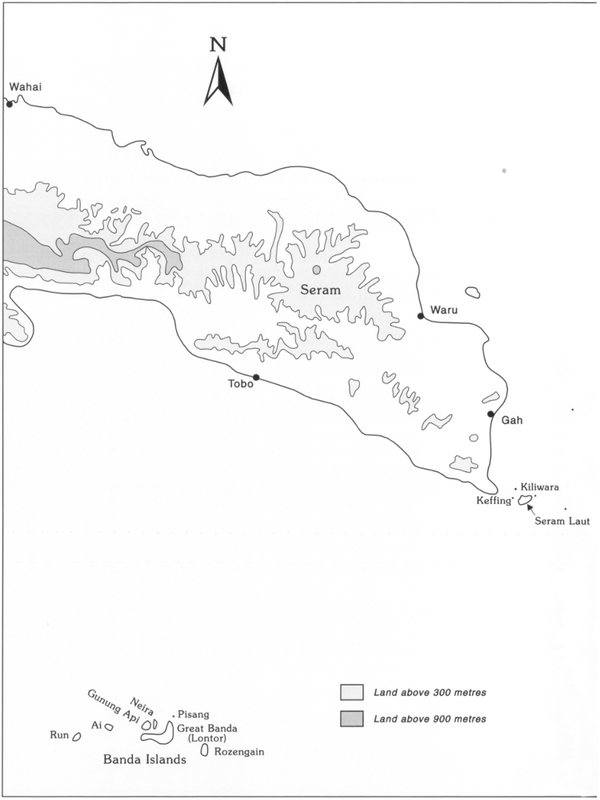

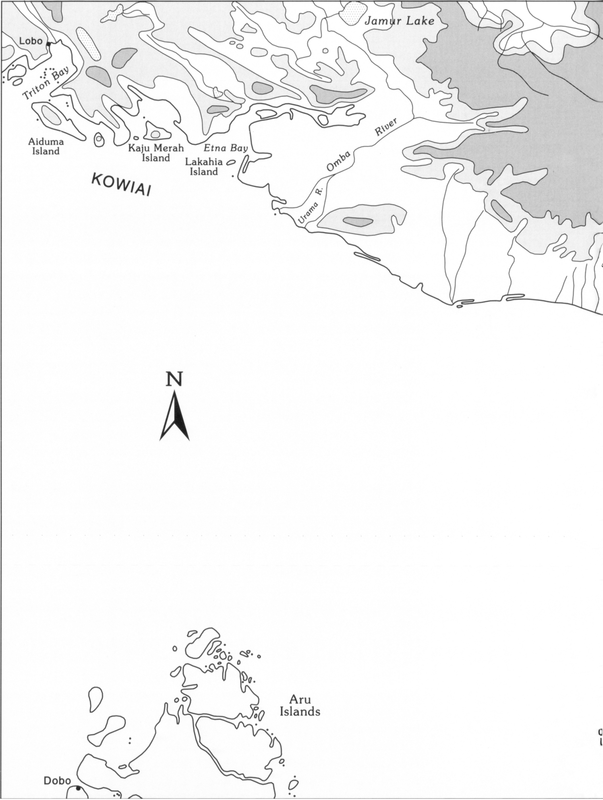

The presence of massoy trees attracted traders to the Onin peninsula (Figure 27) during the spice and aromatic woods trade cycle. As massoy stocks diminished, traders began to move progressively southeastwards seeking unexploited stands. In the seventeenth century the Dutch made a number of unsuccessful attempts to participate in this trade. Interest in massoy and bird of paradise skins continued when the trade emphasis changed to supplying marine products to China. At this time the Seram Laut dominated trade on the southwest coast. Attempts by the Sultan of Tidore to extend his influence over New Guinea in the 1850s did much to destabilise the Kowiai coast. Trading by the Seram Laut went into decline when the Dutch began establishing administrative posts on the southwest coast late last century.

The early massoy trade

Southwest New Guinea is renowned as a source of massoy, an aromatic bark, widely valued in the Indonesian archipelago, especially on Java where it does not grow. The bark of the massoy tree (Cryptocarya massoy) yields a volatile oil comparable to cinnamon. Massoy has a sharp taste, strong pleasant smell and gives a warm feeling when applied to the skin. In Southeast Asia massoy has many uses. It is used in medicines, cosmetics, perfumes, as a food flavour and in dye fixing. In some areas a solution of massoy oil and water used to be applied to the skin to ward off the spirit of a slain enemy.1 In herbal medicines it is taken as a tonic as well as used to treat stomach and intestinal problems, to prevent cramp during pregnancy and to assist recovery after childbirth. On Java a watery pulp made from ground massoy, cinnamon, cloves and sandalwood is smeared on the skin. This gives a pleasant warm feeling as well as an agreeable smell. Ground massoy is widely used in curries and other dishes. It is also used as a dye fixative by the Javanese batik industry.2134

Figure 27: The Banda Islands, eastern Seram, the Seram Laut Islands and Onin.135

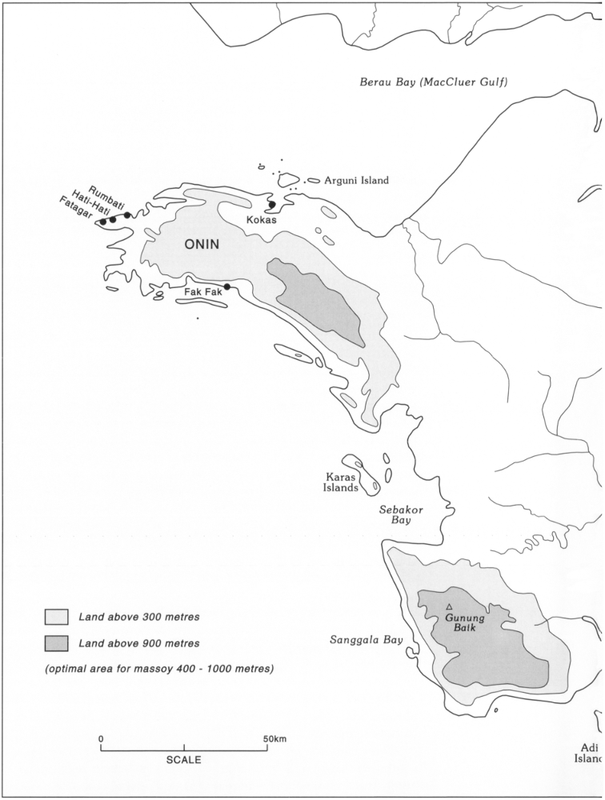

136The optimal conditions for massoy trees exist in foothill rainforest between 400 and 1,000 metres above sea level. The massoy tree has no buttress, a straight bole and grows to a maximum height of 25 metres. The bark is harvested by cutting a circular incision at the base of the tree by a bushknife or axe as low as possible. Other incisions are made at regular intervals up the trunk and along the larger branches. The bark is then peeled off the sapwood in as continuous a strip as possible. Freshly cut bark is easily removed, but it becomes more difficult to do so if left for several days.

After harvesting the massoy bark has to be dried. The way the bark is dried has a direct effect on the quality of the harvest. It is essential that the bark is dried without mould, fungi or rot infestations. The bark is placed in the sun innerside upwards and has to be protected from any rain.

Harvesting massoy bark kills the tree. Attempts by the Forest Products Research Centre in Papua New Guinea to take off partial strips were unsuccessful as the exposed trunk gave access to termites which ruined the tree. Sustained yields in an area are only possible if natural regeneration is encouraged.3

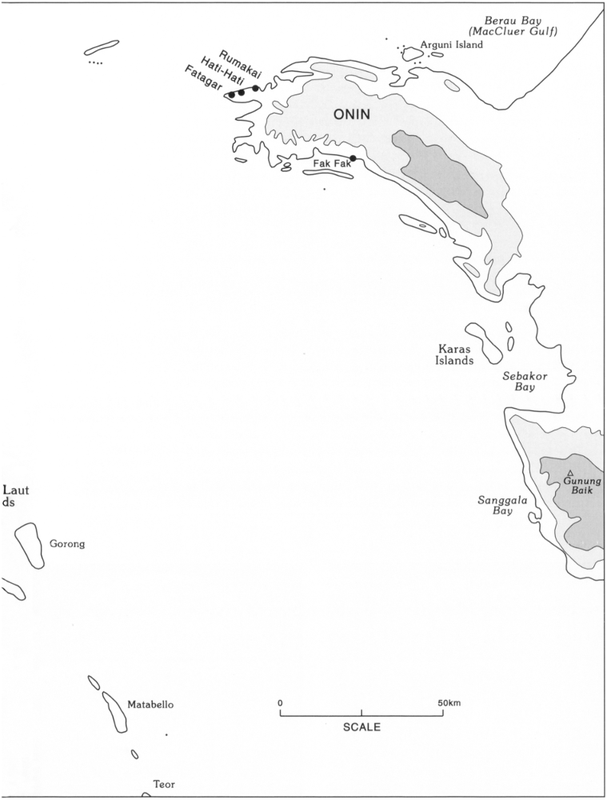

Early records indicate that Javanese traders were visiting southwest New Guinea in the fourteenth century, as Onin is mentioned in the ancient Javanese poem the Negarakertagama which dates from 1365 AD.4 By the fifteenth century Chinese traders were participating in this trade. South Chinese trade pottery from this period occurs in the Risatot burial site on Arguni Island on the north coast of Onin5 (Plate 23 and Figure 28).

Plate 23: Chinese plates from the Risatot burial site on Arguni Island in Berau Bay.

Source: Roder 1959. Reproduced by permission of the Frobenius lnstitute, Frankfurt (Main).

137The Sultan of Bacan, who claimed Onin as part of his territory in 1512, would have played a role in the massoy trade which was dominated by Javanese and Chinese traders. This all changed when Banda was sacked by the Dutch in 1621 (see Chapter 2). Following this sacking Banda ceased to be an important entrepôt for Asian traders. Apart from disrupting their trading operations the Dutch discouraged them from visiting the Spice Islands.

The Bandanese who escaped to the Seram Laut Islands (Figure 27) during the destruction of Banda were probably responsible for stimulating an interest amongst the Seram Laut in supplying Asian markets. With Bandanese expertise these islanders were able to extend their trading activities. In this way the Seram Laut Islands became an important trade centre for massoy and other products.

Before the arrival of the Bandanese migrants, the Seram Laut were part of a well-established inter-island trade network. Schouten learnt in 1602 that the Seram Laut traded over a vast area. He was told that they went as far as Papou (Papua, i.e., the Raja Empat group), New Guinea, Beura (Burn) and Tymar (Timor).6

The Dutch stopped the trading activities of the Seram Laut in the Aru Islands in 1645, but this did not restrict them from trading in areas where the Dutch had no trade interests. The volume of their trade between 1621–1800 rivalled that carried out by the Dutch in this part of the East Indies.7

After the sacking of Banda, the Seram Laut provided products from New Guinea to trade centres at Bali, Pasir (southeast Kalimantan) and east Java. They smuggled spices when they could obtain them and traded massoy, turtle shell, pearls, birds of paradise skins, damar, ambergris, Papuan slaves and from about 1750 trepang. Most of the smuggled spices went to China and India. The Seramese were well aware of the value of spices and their rebellions against the Dutch were largely inspired by talk about a free spice trade. In return for their produce they obtained rice, guns, cloth, pottery and utensils. Bugis and other traders also illicitly met these traders at Seram.8 Denied access to the Aru Islands by the Dutch in 1645, the Seram Laut apparently extended their activities to the Trans Fly coast of Torres Strait (see Chapter 9).

The Dutch East India Company also began to take an interest in the southwest coast of New Guinea when they realised that the Seram Laut were clearly carrying out a profitable trade there. They observed that traders from Seram Laut, including Gorong, traded on the Onin coast and further south. The trade consisted of textiles, beads, etc., in return for captured slaves and massoy. These traders established their own trade monopoly (sosolot) in certain areas by making agreements and 138intermarrying with the local people.9 The existence of these agreements explains why the Dutch East India Company was never successful in establishing trading ventures on this coast.

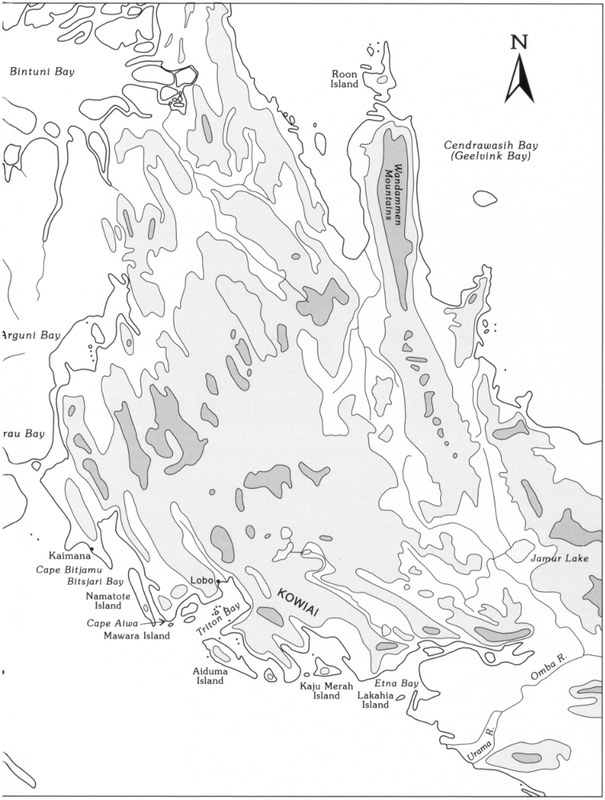

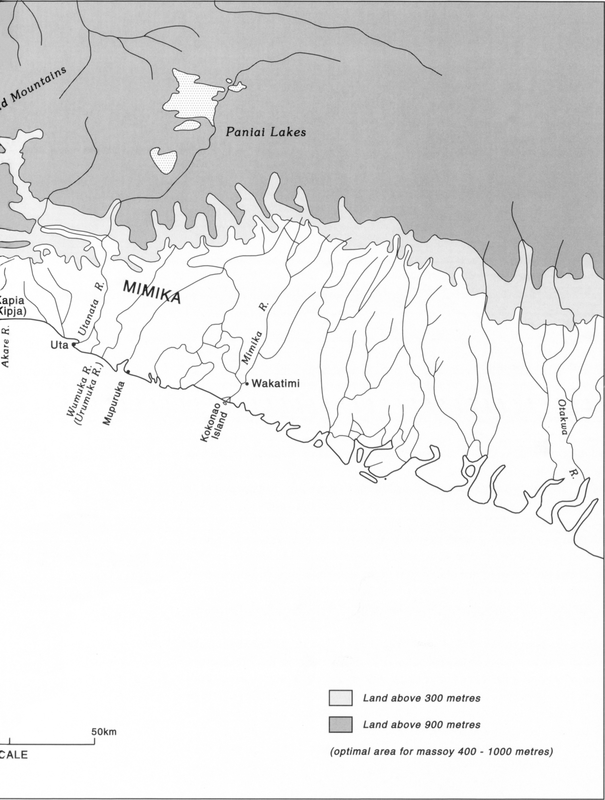

In 1623 the Governor of Amboina (Ambon) sent Jan Carstensz with the yachts Pera and Arnhem to investigate how the Dutch could gain control of the massoy trade on the southwest coast of New Guinea. This investigation ceased when the captain of the Arnhem was killed on the Mimika coast near Mupuruka (Figure 29). In 1636 Gerit Pool made a second attempt to take over the massoy trade. He was also instructed to investigate the brown (smithing) coal reported by Seram Laut traders at Lakahia (Figure 27). Pool was killed soon after his two ships reached Namatote. His successor continued on to the east Mimika coast, but did not go ashore.

After 1650 there were a number of generally unsuccessful Dutch attempts to purchase slaves on the Onin coast. During one of these trips in 1663 Nicolass Vinck sailed the Garnaal and Walingen into Berau and Bintuni Bays (Figure 27), but failed to find a passage. Before these ships found their way out their crews had several fights with the local people.

Despite these set-backs, and the fact that the price of massoy had begun to decline, the Dutch East India Company decided to persevere in its efforts to take over the massoy trade. Observations that the Seram Laut were still profitably trading on the Onin coast encouraged them in this endeavour. Johannes Keyts was sent to try again. In 1678 he visited the Onin and Kowiai areas. Keyts distributed Dutch East India Company flags with great solemnity during this voyage. Trade contracts were made on the Onin coast at Fatagar and Karas. They also visited Sebakor Bay, Sanggala Bay, Adi Island, Cape Bitjanu (?Bitsjari Bay) and Namatote Island (Figure 28).

In the Kowiai area Keyts made a trade contract with the Namatote islanders for massoy and other products, as well as smithing coal from the then uninhabited island of Lakahia. The Seram Laut soon put an end to this agreement by turning the people of Namatote against the Dutch. In an ensuing incident six of Keyt’s men were killed. Following these deaths the Dutch East India Company’s interest in the massoy trade came to an end.

After Keyts the only regular trips to western New Guinea were made by Dutch planters on Banda. These voyages were risky undertakings and Gorong islanders in particular resented their competition. Many of the planters lost their lives as a result of sickness, bad weather and inter-village fights.10139

The Seram Laut massoy trade

The Dutch scholar George Eberhard Rumphius documented that Seramese traders went to the coastline south of Berau Bay in 1684. Most of these traders came from the Seram Laut Islands, including Gorong, situated at the eastern tip of Seram. They called the western part of the New Guinea coast they visited Papua Onin and the eastern part Papua Kowiai.11

Rumphius collected a considerable amount of information about where and how massoy bark was obtained in the late seventeenth century. The trees were known to grow on the alkaline soils of the coastal mountains as far east as the Omba (Opa) River. It took 2 to 3 days to walk from the coast to where they grew. In addition to massoy, slaves were also obtained in this area and traded.12

Recorded observations indicate that massoy bark was gathered in Onin with no concern for sustained harvesting; any massoy tree found was chopped down and its bark peeled off; young trees were not excluded. This caused the massoy trade to be relocated as local supplies were exhausted. By the first half of the seventeenth century the main source of supply had moved south from Onin to the Karas Islands (Figure 28). These islanders assisted traders who settled in their islands to obtain massoy from the mainland between Gunung Baik and Arguni Bay. By 1670 the centre of trade had shifted eastwards again, this time to Namatote Island on the Kowiai coast. In addition to Namatote, other islands, namely Mawara, Aiduma, Kaju Merah and Lakahia became trading centres and some traders settled on them.

Rumphius describes the nature of the contact between the traders and the people of the Kowiai coast. The latter obtained poor quality swords and hacking knives from the traders to use in the far-off mountains to gather enough massoy bark to load one or two boats, that is 60 to 100 piculs of bark (a picul is 60.5 kilograms). When they returned to the beach they piled the bark in heaps as high as a sword. The Kowiai leader then indicated by sign language what they wanted in return for the bark. The Seram Laut traders were far from generous and gave as little as they could. In addition to the poor quality swords and hacking knives, they also gave cloth. Black sugar and rice had already been given in advance to make the Kowiai willing to go and gather the massoy.13

Seram Laut traders continued to expand their operations on the southwest coast until the Sultan of Tidore instigated hongi raids in 1850. These punitive raids discouraged trading and had a devastating impact.140

Figure 28: The Onin and Kowiai areas of southwest New Guinea.141

142Fort Du Bus and Dutch interest in New Guinea

Political upheavals in Europe from 1795–1814 resulted in alternating Dutch and British control of the East Indies (see Chapter 6). After this experience, both the Dutch and English recognised that a successful entrepôt in eastern Indonesia would be a profitable venture. The Dutch were prompted to proclaim their interest in New Guinea after the British established a settlement on Melville Island in northern Australia in 1824.

As mentioned in Chapter 6, in 1828 Dutch soldiers were landed near Lobo in Triton Bay (Figure 28) and established Fort Du Bus on the swampy shore of a sheltered inlet. From this fort on 24 August 1828 the Dutch proclaimed all the land on the south coast of New Guinea as far as 141° east longitude (a few kilometres west of the current south coast border between PNG and West Papua) and northwards as far as the Cape of Good Hope on the Bird’s Head. During the next eight difficult years over 100 personnel stationed at this fort died. It was clearly a project gone wrong. The Dutch decided to demolish the fort in 1836 and relocated the soldiers who had been garrisoned there to Wahai, a small port on the north coast of Seram which at that time was frequently visited by English and American whalers.14

The Seram Laut traders

The main trade centre in the Seram Laut Islands off eastern Seram in 1860 was Kiliwara (Figure 27). This small island, which is some 45 metres across and little more than a metre high, had excellent ground water and good anchorages in both monsoons. When Wallace visited Kiliwara in 1860, it was the main Bugis trade centre for New Guinea. Bugis who traded in New Guinea called there to refit for their home voyage as well as sort and dry their cargoes. In New Guinea they had obtained trepang, massoy bark, wild nutmegs, turtle shell, pearls and bird of paradise skins.

Gorong and other Seram Laut traders also brought their trade produce from New Guinea to Kiliwara and obtained cloth, sago cakes and opium in exchange. The opium was smoked by the Gorong and also by chiefs and wealthy men on Misool and Waigeo, who had been introduced to opium by the Gorong. Villagers from the mainland of Seram provided Kiliwara and the other islands with sago. Rice from Bali and Makassar was also available at a reasonable price. Bugis arrived at Kiliwara from Singapore in their lumbering praus bringing produce from China and Southeast Asia and cloth from Lancashire and Massachusetts. Schooners also came from Bali to buy Papuan slaves.

143Every year Gorong traders visited the southwest coast of New Guinea from Utanata (Figure 29) in the south to Salawati in the north. They also travelled to the Aru, Kei, Tanimbar and Banda Islands (Figure 2) as well as the islands of Ambon, Waigeo, Misool, Tidore and Ternate. All their praus were made by Kei Islanders. Their chief trade interests were massoy bark and trepang, followed by wild nutmegs, turtle shell, bird of paradise skins and pearls. They sold these to the Bugis traders at Kiliwara or Aru; few Gorong took their produce westwards themselves.15

The traders appointed raja where they operated, and these rajas in turn appointed their own representatives as a means of extending and maintaining their sphere of influence. These representatives were given the title of kapitan, orang tua, major, hakim, etc., by the raja who appointed them. In line with this practice the Raja of Namatote appointed trading agents, whom he called rajas, at Aiduma and Lakahia in 1828 and at irregular intervals collected taxes from these representatives. The taxes consisted of cups, bowls, copper rings and cloth.16

Seram Laut traders had begun trading as far east as Utanata before 1828. They built temporary houses to stay in during their annual visit. The traders sometimes took local dignitaries on visits to Seram. Modera describes the appearance of a chief living at the mouth of the Utanata River who was invited aboard the Triton in 1828. He wore a loose Malayan coat and a handkerchief tied round his head. Modera also reports that the Uta (Utanata) people were good-natured and did not steal articles left unattended on shore. They also traded papaya and oranges as well as other produce.17

When villagers promised to supply traders with a certain quantity of forest and/or marine products, the traders gave them goods on credit. In the majority of cases the promised products were supplied in the agreed time. Usually this was several months, the time required to gather the products, but sometimes the traders had to wait many years; in some cases promises were never fulfilled. Those villagers who failed to keep a promise hid in the mountains when the traders they had dealings with came back seeking their goods. In May 1874 Miklouho-Maclay met the anakoda of a prau from Makassar near Namatote Island. He had been waiting six years for products he had been promised.18

During his second visit to the Onin coast in 1828 Kolff observed that every year the Onin coast was visited by two to three traders from the Seram Laut Islands. They stayed in houses built for them at established trading stations. Among the goods they brought to Onin were elephant tusks and large porcelain dishes.19144

Figure 29: The Kowiai and Mimika coasts of southwest New Guinea.145

146The Seram Laut traders working in the Triton Bay area in 1828 usually stayed 4 to 5 months. They sought massoy and other barks (belishary, rosamala) which were used in Bali and Java as medicine and cosmetics. They also obtained nutmegs, dye woods, edible bird’s nest, bird of paradise skins, live cockatoos, lories and crowned pigeons.20

Contact with the Seram Laut led to some Moslem converts. A Moslem missionary was resident at Triton Bay in 1826. He and other notables lived in Malay-style houses and dressed in Malay fashion. Two years later an abandoned Malay-style house was all that remained following a raid from the Karas Islands.21

The impact of the Sultan of Tidore

In 1850 the Sultan of Tidore, with Dutch encouragement, began to assert his authority over a greater area of Dutch New Guinea. He did this by issuing levies, which included the procurement of a certain number of slaves. If these levies were not met, punitive hongi expeditions were made to ensure that all future demands would be.

The Onin people were subject to Tidorese hongi expeditions, but seem to have fared better in the last half of the nineteenth century than those along the Kowiai coast. The hongi fleets avoided the Karas Islands and other places frequented by traders. In 1874 a hongi expedition made on behalf of the Sultan of Tidore was led by Sebiar, the Raja of Rumasol on Misool Island. He imposed heavy taxes on villages such as HatiHati and Rumbati on the Onin Coast (Figure 28). Rumbati had to supply 15 slaves of both sexes or their value equivalent in massoy, nutmeg, turtle shell and other goods.22

Hongi expeditions were viewed with considerable dread by traders. Although their own vessels were rarely if ever attacked, the news that a hongi flotilla was out drove the coastal people into hiding and all hopes of trade during the season were put to an end.23

In the 1850s only small quantities of massoy bark and wild nutmegs were available from the Onin coast, although it produced the usual turtle shell and trepang. There were a few Moslem villages along the coast, but these were subject to constant attacks from interior groups. The Gorong were the only traders who regularly visited Onin. They suffered frequent attacks which often resulted in fatalities. These incidents sometimes occurred when the local people were not satisfied with the trade transactions taking place.24

The Sultan of Tidore’s efforts to extend his influence over New Guinea destablised the Kowiai coast. In 1850 ‘Prince’ Ali25 of Tidore raided Lakahia Island and levelled all the huts and the few coconuts to the ground. About a hundred Papuans were enslaved during this attack. The terrified survivors fled and settled on the mainland. The 147island still appeared to be deserted in 1852. When Miklouho-Maclay visited the area in 1874, the survivors recalled with terror the devastation perpetrated by this hongi.26

The Sultan of Tidore’s 1850 raid had a major impact on the Kowiai region. It not only caused a deterioration in relations between coastal communities, but also problems between coastal and inland communities. Confrontations between these groups were also exacerbated by the increased fatalities resulting from the gunpowder, lead and guns now readily available as trade goods.

The deteriorating situation on the Kowiai coast also affected Seram Laut trading ventures. When Wallace was in a village on Gorong in May 1860, two praus from this island were attacked on the Kowiai coast. They had been bargaining for trepang in broad daylight. The incident was not a chance encounter, as the traders had established themselves ashore and had anchored their praus in a small river nearby. The fourteen men on shore who were trading were killed. The six men remaining on the two praus were able to escape in one prau and bring the news. Once known, shrieks and lamentations were heard throughout the village as almost every house had either lost a relative or a slave. Scarcely a year passed without some lives being lost. About 50 Gorong traders lost their lives on the Kowiai Coast in 1856.27

The Onin coast was still being visited in the 1870s by Bugis traders in their paduakan and by the inhabitants of the Seram Laut Islands in their smaller praus.28 They traded for massoy, wild nutmegs, trepang, turtle shell, mother-of-pearl and pearls. Some slaving still existed.

When Miklouho-Maclay visited the Kowiai coast in 1874, he found that traders avoided this coast. When asked for an explanation as to why they had ceased visiting the Kowiai coast, they claimed that it was no longer worthwhile going there as they were usually assaulted and their praus plundered.29 The lives of the local people were also disrupted. Miklouho-Maclay observed the nomadic life they lived. He describes how they constantly moved from bay to bay in their small praus –

The traces of destroyed and deserted settlements scattered in various places as well as the abandoned plantations show that the Papuan can lead a settled 148life. Papuans often told me of their desire to have a permanent dwelling-place, and they even demonstrated this in deed, settling near my cabin at Aiwa [Figure 28] from the very moment I built it and even cultivating plantations, assuming that it would be safer for them in my proximity.

I can state myself that the fear of sudden raids was quite justified, for during my short sojourn of approximately two months on the Papua Kowiai Coast there were three devastating raids. The first of these raids was led by the inhabitants of Kamrau Bay against the Papuans of Kayu Mera Island, only a few of whom managed to escape. Most of them were killed or taken prisoner. When I visited Kayu Mera Island in March 1874, I did not find a single person there. Those who had managed to escape with their lives, fled into the mountains.

The second raid was directed against the inhabitants of Aiduma who settled near my cabin at Aiwa. The wife of the radya [raja] of Aiduma was speared to death, and his six-year-old daughter was cut into pieces with a parang; many women and several men were wounded; two girls and one man were taken prisoner. That was the time when my hut was looted by the plunderers, who pillaged almost all my things and provisions. The plunders and murders were perpetrated by the mountain dwellers of Bicaru [Bitsjari] Bay and the inhabitants of Namatote and Mawara.

The third raid was undertaken by the mountain people of Kamaka, called the wuousirau, allies of the defeated inhabitants of Aiduma; they attacked the mountain dwellers of Bicaru Bay and the men of Namatote to avenge the death of the radya [raja] of Aiduma’s wife and daughter. The outcome of this raid remained unknown to me, but, as punishment for the plunder of my house, I took the captain, or chief, of the Archipelago of Mawara prisoner, wishing to hand him over to the resident of Amboina (Ambon).30

Miklouho-Maclay was so perturbed by the plight of the people on the Kowiai coast in 1874 that he wrote to the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies offering to spend a year pacifying the area. He proposed to do this by founding a settlement with the assistance of several dozen Javanese soldiers and a gunboat. For his own services he sought no remuneration from the Dutch Government. His offer was rejected by the Governor-General on the grounds that the Dutch had no intention of extending their colonies.31

When the marine paddle steamer Soerabaja visited Etna Bay in 1876, the Raja of Lakahia was found living on the shore of this bay. He spoke Seramese and some words of Malay and had visited Seram, Banda and Makassar.32

The fighting on this coast was not over. At the end of the nineteenth century the Etna Bay people were attacked by people from the upper Omba (Opa) River and Jamur Lake (Figure 28). They had obtained guns from Ternatian bird hunters who had presumably entered their area 149from Cendrawasih Bay. When the inland people came to make peace in 1903, they were attacked in turn. The Etna Bay people then fled to the lower reaches of the Urama near Buru southeast of Etna Bay. There the Raja of Lakahia and 11 others were killed and 10 women and children were captured.

These and other incidents resulted in a marked decline of the Etna Bay population. Observers on the Soerabaja estimated in 1876 that about 300 people lived there in four settlements. By 1900 the population living in Etna Bay at Urama village was only 100. A further decline occurred as a result of alcohol abuse and the 1918–9 influenza epidemic.33 Such a history does not allow the decline in the Etna Bay population to be primarily attributed to attacks by inland communities moving to the coast.34 Hongi expeditions, influenza and alcohol abuse were also significant factors in this decline.

An administrative post was established at Fakfak (Figure 28) in 1898.35 The presence of Seram Laut traders and their Islamic influence declined with the coming of the Dutch administration. They were replaced by increasing numbers of Chinese traders and Christian missionaries. Bird of paradise hunters remained active in the region. In 1913 it is reported that traders in Fakfak and Kokas (Figure 28) bought 8,000 skins worth £40,000.36

Mimika Coast

As mentioned above, Seram Laut traders were trading as far east as Utanata (Figure 29) by the mid 1820s. The Raja of Namatote appointed a raja at Kapia (Kipja) for the area east of Lakahia in 1850. In addition to Seram Laut traders, traders from the Aru Islands visited the Mimika coast.

Some Mimika have a legend about their first contact with foreign traders. It tells how two fishermen got off course and finally ended up in the Aru Islands and how the Aru Islanders took the fishermen home. In retrospect, it seems likely that these Aru Islanders seized this incident as an opportunity to establish trading ties with the Mimika.

For the Aru Islanders it was an opportunity to gain access to unexploited resources which they could obtain at low cost. The Mimika were delighted to see the trade goods (tobacco, choppers and sarongs) the Aru men brought. The Aru selected one Mimika man to be the chief (kepala) and he was given a paper (surat).37 Before the Aru men travelled inland to gather massoy bark, they made a part payment of some choppers. On their return they bartered more choppers and sarongs to complete the payment for the massoy bark.38 Curiously the Aru men gathered their own massoy bark, unlike the Seram Laut reported above.

150According to P. Drabbe, who was a missionary, the Mimika never learnt Malay. Instead the traders learnt a certain number of words from Kamoro (the language spoken by the Mimika) and only used Malay words for newly introduced and previously unknown objects. The Mimika incorporated these words into their own language, in a form suited to it, and avoided the intricate verbal conjugations of Malay.39 This would explain why the explorer A.F.R. Wollaston, who was a member of the 1910 expedition, found Malay no use as a means of talking with the Mimika.40

Seram Laut traders along the with the Raja of Namatote and his assistants kept control of the trade and contact between the Kowiai and foreigners until 1898. By appointing officials they established the non-traditional role of the raja. This person was appointed because the traders wanted someone through whom they could give orders. Some of these rajas became quite powerful. For example, the Raja of Kapia (Kipja) once controlled the entire Taija district, which included the people living along the Poraoka, Kipja, Maparpe, Akare and Wumuka Rivers.41

When a Dutch administrative post was opened at Fakfak on the Onin coast in 1898, Seram Laut traders and the Raja of Namatote had to reduce their slave and weapon trade in the Kowiai area. The Raja of Namatote counteracted this by strengthening his influence at Kapia in west Mimika.

The arrival of Chinese traders in about 1915, as well as the Dutch administration and the Roman Catholic Mission, brought an end to the presence of the Seram Laut and their Islamic influence amongst the Mimika. The Chinese traders sought sandalwood, damar, massoy and sago. They came every month bringing cloth, axes, knives, tobacco and betel nut (pinang). Some Arguni Bay people (Figure 28) came to the Mimika area to work for the Chinese traders, married locally and stayed on. Bird of paradise hunters also came to Mimika. The activities of Chinese traders resulted in the Dutch establishing a government post some hours up the Mimika river near Wakatimi in 1926. It was soon transferred to Kokonao at the delta mouth.42

By the time they came under government control imported goods such as Chinese dishes and gongs had become important bridewealth items amongst the western Mimika.43 Some crops such as papaya, sweet potatoes, cassava, cucumbers and pumpkins were probably introduced by Seram Laut traders.44 The traders may also have taught the Mimika how to make toddy from the Segero palm which thrives in the upriver areas.45151

Notes

1. Muller 1990b: 66.

2. Zieck 1973: 14.

3. Zieck 1973: 15, 17.

4. Rouffaer 1915 cited by Galis 1953–4: 6; O’Hare 1986.

5. Roder 1959.

6. Galis 1953–4: 12.

7. Lerissa 1981 cited by Ellen 1987: 46.

8. Wright 1958: 6–7.

9. Galis 1953–4: 16.

10. Galis 1953–4: 13-4; Pouwer 1955: 215–8.

11. The eastern boundary of the Kowiai area changed over time. Initially it extended no further than the Omba (Opa) River (Figure 28). By 1828 it had been extended along the coast as far east as Utanata (Figure 29) (Pouwer 1955: 218). Except for those along the Mimika River, the people along this coast initially adopted the name Kowiai or Koviai (Drabbe 1947–8: 157–8), but in post World War II literature the people who occupy the swampy lowlands from Etna Bay in the west to the Otokwa River in the east are generally referred to as the Mimika or Kamoro speakers (Figure 29). Before the late 1920s they lived in semi-permanent settlements from where they made regular trips to sago areas and gardens, as well as fishing grounds located at river mouths downstream. A cycle of large and small feasts were associated with these movements. Their eastern neighbours are the Asmat, who are related to the Mimika (Pouwer 1970: 24–5; Kooijman 1966: 54).

12. Pouwer 1955: 215.

13. Pouwer 1955: 215–6.

14. Earl 1853: 56; Galis 1953–4: 21.

15. Wallace 1986: 380–1.

16. Pouwer 1955: 216, 218.

17. Earl 1853: 43, 49, 52.

18. Miklouho-Maclay 1982: 441.

19. Earl 1853: 59–60.

20. Earl 1853: 58.

21. Earl 1853: 55, 57–58.

22. Miklouho-Maclay 1982: 443.

23. Earl 1853: 54

24. Wallace 1986: 379.

25. Pouwer (1955: 218) refers to this Prince by the name Ali; Miklouho-Maclay (1982: 443) calls him Amir.

26. Miklouho-Maclay 1982: 443.

27. Wallace 1986: 378–9.

28. Miklouho-Maclay 1982: 439.

29. Miklouho-Maclay 1875: 1982: 439.

30. Miklouho-Maclay 1982: 440–1.

31. Miklouho-Maclay 1982: 444–5.152

32. Pouwer 1955: 219.

33. Pouwer 1955: 219–20.

34. see van Baal et al 1984: 25.

35. Galis 1953–4: 27.

36. Historical Section of the Foreign Office, London 1920: 26.

37. Kepala and surat are both Malay words.

38. Drabbe 1947–8: 256–7.

39. Drabbe 1947–8: 158.

40. Wollaston 1912: 102.

41. Drabbe 1947–8: 257.

42. Pouwer 1955: 224, 230–1.

43. Trenkenschuh 1970: 124.

44. Pouwer 1955: 43.

45. Trenkenschuh 1970: 129.