2

The rise and decline of the Spice Islands

Introduction

Spice trading began in prehistoric times during the foundation period of inter-island trade and continued as a subsidiary activity in the first trade cycle when specialist Asian traders sought plumes from New Guinea. During the second trade cycle spices became the prime product acquired by Asian, and subsequently European traders. Unrealistic expectations, poor management of spice production and marketing, and greed brought about the economic decline of the Spice Islands. As a result the inhabitants of the Spice Islands found themselves forbidden from growing the spices their ancestors had domesticated. The declining prosperity of the region led to raiding and acts of retribution. Later some Spice Islanders participated in the supplying of marine products to China during the third trade cycle and plume trading during the fourth.

Clove and nutmeg production and use

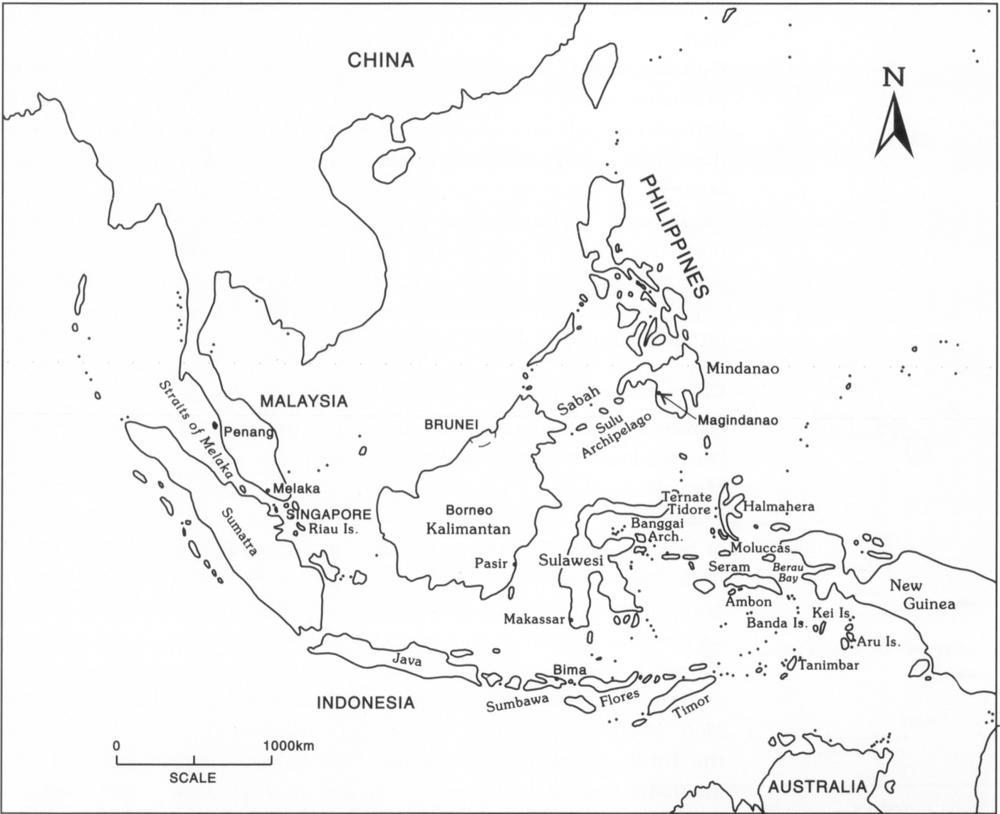

Cloves were first cultivated on the five small volcanic islands which became known as the Moluccas. Individually named Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian and Bacan (Figure 1), these islands are located off the western coast of Halmahera some 400 kilometres from the western tip of New Guinea. This is not that far, in fact closer than a direct flight from Port Moresby to Madang. Along with the islands in the Banda group (Figure 2) the five islands became known as the Spice Islands and remained the only source of cultivated cloves and nutmeg until the sixteenth century.

Today the people on Ternate and Tidore as well as many of those on Moti, Makian and Bacan speak languages related to those spoken on the Bird’s Head of New Guinea.1 Until detailed archaeological and linguistic studies have been made we can only ponder the extent to which this common linguistic heritage was brought about by trade. However, current information suggests that this is a likely explanation 22as the Bird’s Head and the Moluccas have been important trade centres respectively for plumes and cloves.

The use of cloves seems to have begun earlier and been more extensive than nutmegs and mace. By means of a chain of trading transactions cloves were traded to India and the Middle East2 long before they became important in China. Indian records indicate that cloves were traded to the Indian subcontinent before the birth of Christ. Somewhat later a Roman, Pliny the Elder, refers to cloves in 70 AD.3 23

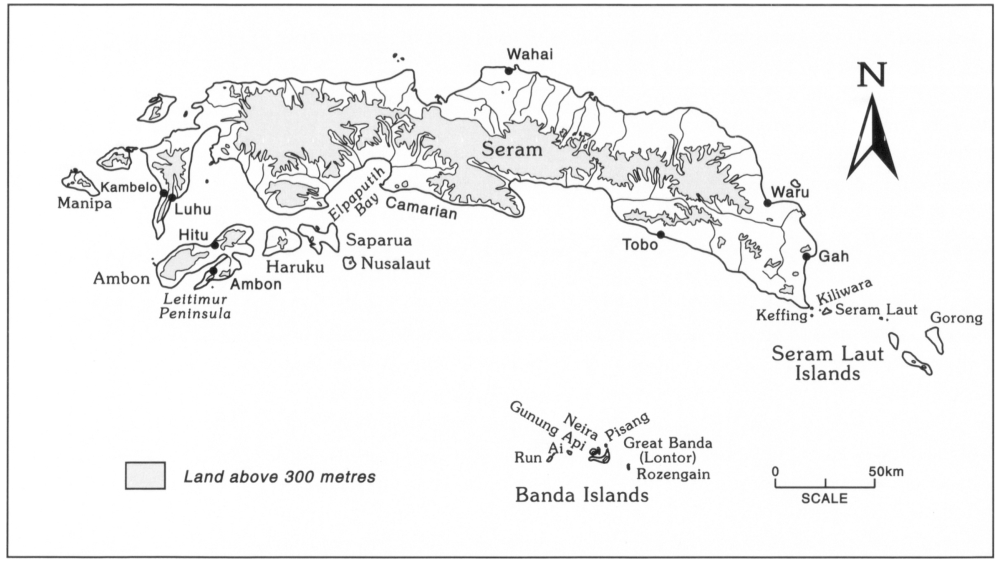

Figure 2: Southeast Asia

The introduction of Hindu-Buddhist cosmological ideas and the concept of a divine ruler to Southeast Asia from the Indian subcontinent about 300 AD led to a marked increase in the use of spices and aromatic woods. From this time the demand for spices and aromatic barks and woods in Asia grew whilst that for plumes declined.

The aristocracy in Europe were using cloves as a cooking ingredient by the Middle Ages (500–1500 AD). By the late Middle Ages nutmegs were also being used. The first reference to nutmegs in Europe occurs in the twelfth century. They were initially used as a fumigant as well as a spice.4

In the thirteenth century cloves were still a scarce luxury commodity in Europe and Asian traders operating west of Java were largely ignorant of their source. They generally assumed that these spices were a product of Java.

During the fourteenth century the Majapahit kingdom of Java extended its influence as far as the Moluccas in order to obtain a regular supply of spices. Majapahit maintained its authority by levying tribute until its decline in the fifteenth century. This contact with Java stimulated the development of a number of kingdoms (sultanates) in the Moluccas, such as Ternate, which became commercially and politically important. The sultans were able to provide traders with large quantities of cloves as they received a large part of each clove harvest as tribute. This gave them a dominant role in the spice trade. The spice traders, who mainly came from abroad, won favour and good terms by assisting the sultans to promote their own interests. The accumulating wealth and regal splendour of these sultans became widely known.

By the fifteenth century the Moluccas were known to Arab traders as jazirat-al-mulk, the land of many kings. The Portuguese pronunciation later gave us Moluco and Moluccas in its plural form.5 When cloves were grown on Ambon and Seram the name Moluccas came to refer to a larger area.

The favoured route to the Spice Islands was via the Sunda chain which includes Timor. Merchants either obtained all the spices they wanted at the nutmeg and mace producing islands of Banda, which also served as an entrepôt for the Spice Islands as a whole, or continued on to the clove producing Moluccas. The established route to the Moluccas was via Ambon and western Seram.24

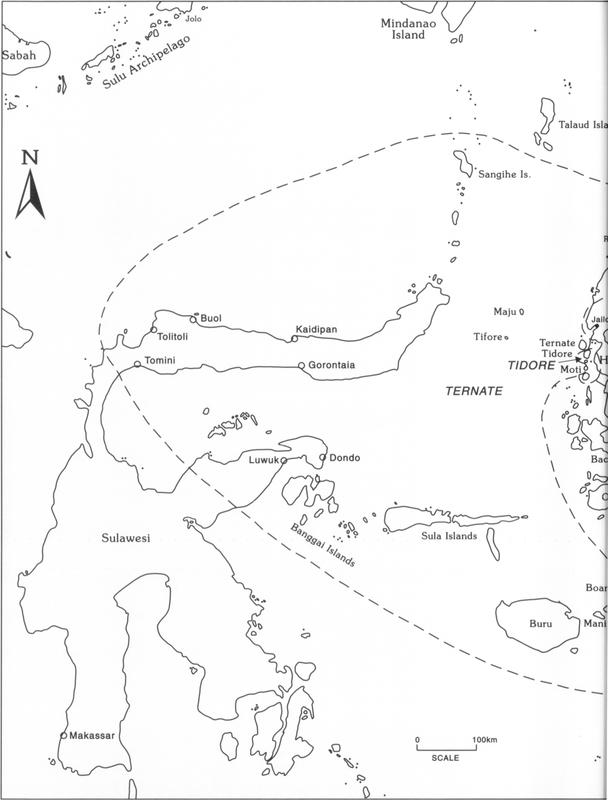

25Figure 3: The subjected territories of the Sultans of Ternate, Bacan, Tidore and Jailolo in the early sixteenth century.

In 1512 the Portuguese became the first Europeans to visit the Spice Islands. They reported that cultivated cloves were only produced on the five islands of Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian and Bacan. Portuguese estimates made in the early sixteenth century suggest that 600,000 to 1,200,000 kilograms of cloves were harvested each year.6 With current average yields of two kilograms per tree7 this would require stands of 300,000 to 600,000 trees.

26Moluccan traditions claim that cultivated cloves originated on Makian.8 Moti also seems to have been a long-term producer, whereas Tidore was more recent than Ternate, and Bacan had only begun ten years before the Portuguese arrived in 1512.9

Wild clove trees are common in the lower montane forests of many islands in the Moluccas and New Guinea. Unlike cultivated trees, wild trees have larger and less aromatic flower buds and leaves. Their essential oil content is also less and it has a different composition. They are also more variable, more vigorous as juveniles and more resistant to matibudjang disease than cultivated cloves.10

Many people can recognise cloves, nutmeg and mace on the spice rack, but know little about the way they are grown. Cloves are the unopened flower buds of Eugenia caryophyllus, a tree which grows from seed to a height of 7–12 metres under plantation conditions. In the Moluccas during the time of the Dutch clove monopoly, clove trees did not begin bearing until they were 15 years old;11 but under favourable plantation conditions they now bear after 6–8 years. They continue producing for as long as 50–60 years.

The flower buds are harvested by climbing the trees and picking the buds growing on the tips of the branches when they are fully grown but unopened. The bud is then green or beginning to turn red. Whole inflorescences are picked by hand and the buds rubbed off and dried in the sun as quickly as possible. This produces the hard, dark brown flower buds we know as cloves.12 Each tree yields about two kilograms of cloves a year with the peak harvest being from June until September.13

Nutmeg is the seed of Myristica fragrans and mace is its seed aril or covering. Nutmeg seeds are produced by the female trees of M. fragrans which are grown in the shade of kanari (Canarium commune) trees.14 In the Moluccas during the time of the Dutch spice monopoly, nutmegs usually took 10 years to come into bearing, earlier fruiting was considered to indicate an inferior tree.15 Today under favourable plantation conditions they begin bearing when 4–6 years old. They grow to a height of 8–12 metres. Some male trees are kept for fertilisation and the rest are usually felled.

The seeds are either gathered by hand from the trees or collected after they have fallen to the ground. The aril is removed from the seed, pressed and then dried in the sun to produce mace. The seeds also have to be dried.16 The cultivated nutmegs from Banda are described as being round, whereas the wild nutmegs collected from the Aru Islands, Halmahera, and Berau Bay (MacCluer Gulf) in New Guinea are long in shape.17

27At present any account of the spice trade in eastern Indonesia is solely dependent on historical records. Archaeology has yet to reveal its side of the story. An archaeological study of the history of exotic goods in the Spice Islands, particularly foreign ceramics, glass beads and other non-perishable goods, as the world demand for cloves and nutmegs grew will undoubtedly enhance what can be reconstructed from historical records.

The socioeconomic and political situation in the Spice Islands in 1512

The Moluccas: cloves

When the Portuguese arrived in the Spice Islands in 1512 there were four sultanates – Ternate, Tidore, Jailolo and Bacan.18 The political and economic infrastructure of these sultanates was hierarchical. Their nature was clearly influenced from Java, just as today Papua New Guinea has a largely Australian infrastructure and towns such as Jayapura in West Papua reflect the Indonesian way of life.

Unlike in the clove producing islands where power was in the hands of sultans, in 1512 Banda had no single ruler. Authority was autonomous. Decisions were made by councils of orang kaya (village elders). In each village they were responsible for organising ceremonies and allocating rights to the nutmeg groves.19

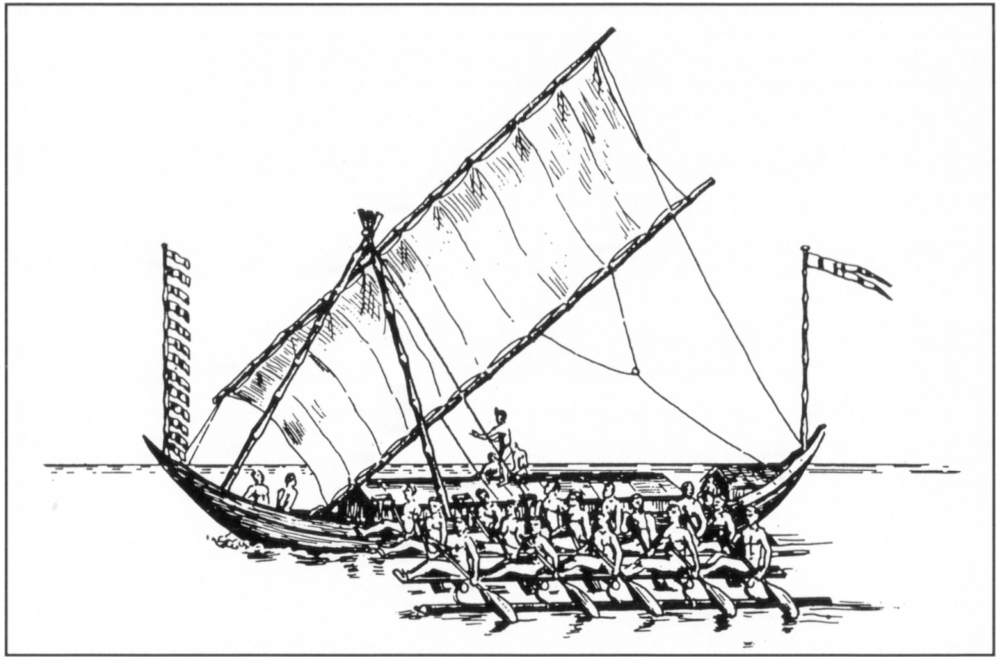

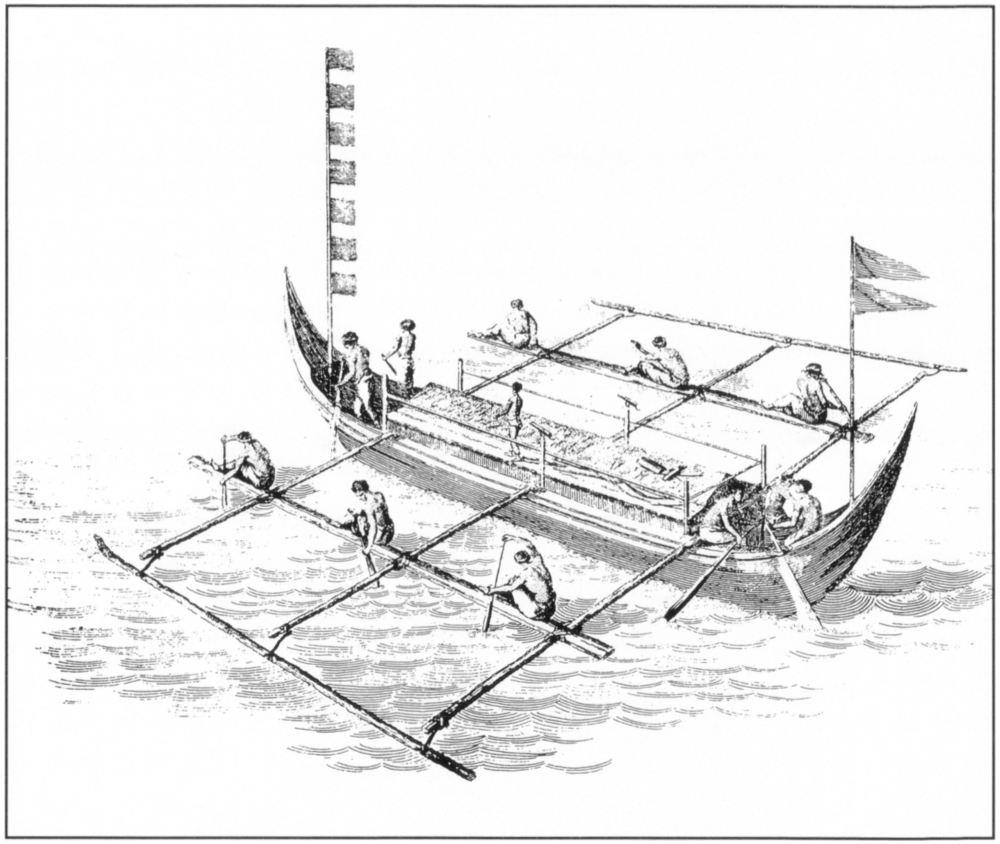

Figure 4: A korakora. Raiding korakora were crewed by 100–300 men.

Source: Röding 1798 reproduced in Horridge 1981.

28In the sixteenth century most of the islands between Sulawesi20 and New Guinea were subjugated by the Sultan of Ternate or the Sultan of Bacan, who was aligned with him (see Table 1 and Figure 3). The number of men the Sultan of Ternate is reputed to have been able to summon at this time is quite astounding. His authority was maintained by keeping a large fleet of paddle-propelled vessels (korakora) in the waters between Sulawesi and New Guinea (Figures 4 and 5).21 These were crewed by slaves. The Sultan obtained these men either as tribute willingly or unwillingly given. When villages failed to pay tribute they were raided and men were seized to work as slaves for the Sultan.

Table 1: The subjected territories of the Sultan of Ternate that provided him with militia at the beginning of the sixteenth century.

| militia available | |

| Ternate | 3,000 |

| Moti (Motir) [part of Moti was also under Tidore] | 300 |

| Maju and Tifore (Myo and Tyfory) | 400 |

| Bao and Jaquita (northern Halmahera) | 1,000 |

| Bata China (northern Halmahera) | 10,000 |

| Veranulla (near Ambon, Amboina) | 15,000 |

| Boana (Buana) and Manipa | 3,000 |

| Buru (Bouro) | 4,000 |

| Sula (Xula) | 4,000 |

| Luwuk (Labaque), Sulawesi | 1,000 |

| Dondo, Sulawesi | 700 |

| Tomini (Tornine), Sulawesi | 12,000 |

| Gorontalu and llboto, Sulawesi | 10,000 |

| Kaidipan (Kydipan), Sulawesi | 7,000 |

| Tolitoli (Tetoli) and Buoi (Bohol), Sulawesi | 6,000 |

| Sangihe (Sangir) | 3,000 |

| Gazia (? location) | 300 |

| Japua (? location) | 10,000 |

Total |

90,700 |

Source: Forrest 1969: 34 (first published 1779).

29The use of paddles more than sails allowed surprise attacks when seasonal and available winds were unfavourable for a chosen destination. In contrary winds the use of paddles made korakora much swifter than European sailing boats. Their speed in these circumstances meant that they frequently outperformed European shipping until the 1850s when steam vessels came into use.22

The korakora ranged in size from small vessels to large ones of up to 10 tons.23 The paddlers sat on platforms stretched across the outrigger booms as shown in Figures 4 and 5. Large raiding vessels had four platforms with fifty paddlers on each side of the korakora. Fighting men rode on a superstructure of platforms raised over the hull.24 Korakora were so well suited for Moluccan conditions that they were used also by European visitors such as Forrest and by Dutch naval patrols based at Ambon.

Figure 5: A Moluccan korakora.

Source: Forrest 1969: Plate 4 (first published 1779).

Tidore’s jurisdiction was small at this time. It consisted of part of Moti and Halmahera and the important clove island of Makian. This island had the best harbour in the Moluccas. Makian was a major export centre exporting not only its own cloves but those from other islands as well. Despite all these geographical advantages, the people of Makian were subordinate to the Sultan of Tidore, whose island had no harbour suitable for long distance vessels.25

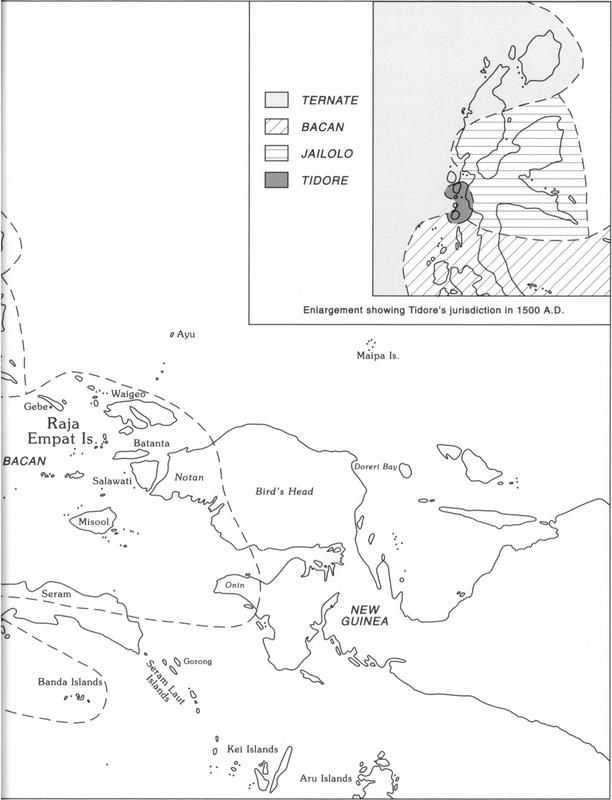

30Early Portuguese accounts report that Bacan first started cultivating cloves about 1500. They also mention that this sultanate had good ports and was active in trade.26 The nature of this trade is not stipulated, but probably involved massoy bark from Onin, as well as bird of paradise skins from the Raja Empat Islands, Bird’s Head and Onin (Figure 3). This would explain why it was the Sultan of Bacan who presented five Lesser Bird of Paradise skins to the Spanish expedition in the Moluccas in 1521.27

Curiously the Portuguese also report that Bacan along with Tidore and Ternate were net importers of foodstuffs. Rice had been supplied from at least the twelfth century.28 In Bacan’s case this was probably a luxury, presumably paid for by massoy bark and bird of paradise skin exports, as early Dutch accounts indicate that food was plentiful there.29 In the early fifteenth century most rice imports came from Java and Sumbawa. Ternate obtained its sago from Moti, the Morotai and Rau Islands of northern Halmahera as well as Seram and Ambon.30

Banda Islands: nutmeg and mace

The Banda Islands were the sole suppliers of cultivated nutmeg and mace when the Portuguese arrived in eastern Indonesia in 1512. Nutmegs were cultivated on Great Banda (Lontor), Neira, Ai, Run and Rozengain (Figure 6). The women of these islands did most of the cultivation.31

Intermarriage with Javanese and Malay merchants established on the coasts of Great Banda and Neira was accepted by the Bandanese.32 A Dutch source reports as many as 1,500 Javanese in the Banda Islands in 1609, with the total Bandanese population being 15,000 people.33 Islam had been introduced some thirty years prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in 1512, but is reported to have been limited to those involved in trade, most likely individuals with Javanese and Malay connections.34

The Bandanese grew only nutmegs, coconuts and some fruit on their tiny islands. They were dependent on trade, mainly with the Aru and Kei Islands, for sago which was their staple food. In exchange for sago they gave coarse textiles from the Sunda Islands brought to Banda by Javanese and Malay traders. The Bandanese also obtained bird of paradise skins from the Aru Islands as well as parrot skins from a wider range of localities. These dried birds were sought by Bengali merchants in Melaka (Malacca) who supplied them to other Indians, as well as Persian and Turkish traders (see Chapter 3 below). 31

The spice trade: merchants, transactions and shipping

The Asian clove trade was based entirely on barter. In addition to foodstuffs, favoured imports in the Moluccas and Banda in 1512 were cloth, metalwork and porcelain. Since the possession of these items was a matter of considerable prestige, they also became incorporated into ceremonial exchanges.

The Javanese and Malays provided a number of products in exchange for cloves, nutmeg and mace. These included rice, cummin, Javanese and Cambaya cloth,35 porcelain, copper, quicksilver, silver, vermilion and Javanese metal gongs. The Chinese provided blue Chinese porcelain dishes and cups, silver, iron, Chinese coins, ivory and beads. Other goods included iron axes, swords and knives from the Banggai Archipelago traded at Ternate, gold from northern Sulawesi and from other places coarse native cloth and bird skins.36 The Portuguese maintained the barter trade in which cloves were exchanged for goods, whereas the Dutch introduced payment in money.

Figure 6: Seram, Banda and Seram Laut Islands.

At the time of Portuguese contact, it is reported that at least eight junks a year visited Banda and the Spice Islands. A wholesale trade was carried out by the captains and supercargoes of these vessels. Other merchants travelling as passengers or crew members carried out their own transactions. Large profits could be made as the prices obtained for spices in Melaka were almost ten times their cost in the Spice Islands.37

32The wealth of the Sultan of Ternate clearly indicates that he carried out a lucrative trade with these merchants. It is likely that the patronage he gave to each ship’s captain and supercargo was comparable to that later recorded as given to the Sultan of Sulu. This sultan and his prestigious datu (notables) usually imposed a customs duty of up to 10 percent of a cargo’s value. In addition to this customs duty the sultan and his datu expected to receive trade goods on credit. These were often repaid in goods with highly inflated prices. This brought the overall presents and exactions received by the Sultan and his datu to at least 30 percent of the total value of a ship’s cargo.38 With such returns, there was no incentive for the Sultan of Sulu and his datu, nor presumably the Sultans of Ternate and Tidore, to contemplate the risk of shipping products to markets themselves. It was easier to let the merchants do the work and receive the material largesse they brought. By this means the sultans accumulated considerable wealth.

When the Portuguese reached Banda early in 1512 they found that this small group of islands served as the entrepôt for the spice trade in eastern Indonesia. In Banda they were able to obtain not only locally produced nutmegs and mace, but also cloves imported by Bandanese and other regional traders. The inhabitants of Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian and Bacan harvested the cultivated cloves growing on their islands, but left the task of exporting them to others.

The Bandanese were the only group in the Spice Islands with vessels large enough to take profitable cargoes to Java and Melaka. These boats were built in Banda for this long distance trade. Pires, a Portuguese scholar who visited Melaka in 1511–1515, reports that there was a shahbandar (harbourmaster) in Melaka who looked after Bandanese interests.39

The Kei Islanders were also known for their boat building, but they only made prau suitable for regional use. The largest vessel they built was the paddle-propelled korakora used in local trade and warfare.

It seems curious that the Bandanese developed long-distance craft, but had no kingdoms; whereas islands such as Ternate, Tidore and Bacan developed kingdoms, but had no long-distance merchant fleets. It has been suggested above that the quantity of presents and exactions the sultans and their notables were able to obtain, from the captain and supercargo of each vessel, played a part in discouraging them from contemplating shipping their own spices.

33However there was probably another factor behind Banda’s development as an entrepôt. This was the ability to sail and return from Banda via the Sunda chain to Melaka in six months, compared with a year to go to and return from the Moluccas. Such a time advantage would have encouraged the development of Banda as an entrepôt and further discouraged the Moluccan sultans from undertaking such voyages. Traders could leave Melaka in January or February, return from Banda in early July and be back in Melaka by August. If they continued on to the Moluccas, they had to leave Banda in May and wait in the Moluccas until January when suitable winds allowed them to return to Melaka. It was also possible to reach the Moluccas by way of Brunei in only 40 days. This route was less profitable than the southern route which also allowed stops in Java and the Lesser Sundas, especially Timor, for sandalwood.40

Local inter-island trade

Within eastern Indonesia there was also inter-island trade. Specialised goods were traded by means of local prau (korakora). In New Guinea pottery was produced in the Jayapura and Sentani region; at Dorey, and on Roon and Japen in Cendrawasih Bay; on Mare Island near Tidore; probably on the Misool and Waigeo Islands; at Arguni, Sekar and elsewhere in Onin; as well as in the Banda, Kei and Aru Islands; and in the Ambon, Haruku and Saparua Islands off southern Seram.41 Shell bracelets were made in Gorong (Goram), cloth in west Seram and prau in the Kei Islands. In addition many island groups were dependent on imported food. For instance, sago, the staple of the Bandanese, was imported from the Kei and Aru Islands.

Relations between the Spice Islanders and ‘New Guinea’

The Moluccan sultans appointed rajas in their domains. Four raja became renowned in the islands off the western tip of New Guinea, hence the name Raja Empat (four rajas). These rajas were resident on the four main islands of Misool, Salawati, Waigeo and Batanta (or ?Gebe).42 The Raja Empat Islands were also referred to as the Papuan Islands. In 1602 a clear difference was made between Papua, namely the Raja Empat group, and the mainland of New Guinea.43, 44 By 1684 stretches of coastline south of Berau Bay (MacCluer Gulf) were known respectively as Papua Onin and Papua Kowiai.

The Sultan of Bacan was aligned with Ternate and reigned over the Obi Islands, northern Seram, the Raja Empat group (the Papuan Islands) and Onin. He also had contact with Notan, the western part of the Bird’s Head.45

34Relations between the Spice Islanders and Europeans until 1599

As soon as the Portuguese captured the Malaysian port of Melaka in 1511, they despatched three ships to the fabled Spice Islands. With the assistance of Malay pilots, these Portuguese ships reached Banda in 1512 having travelled via Java and the Lesser Sundas. Two ships returned to Melaka laden with cloves and nutmegs obtained from Banda. The crew of the third vessel continued on to Ambon and the Moluccas in a local vessel after their ship was wrecked. They then returned to Melaka, except one member, Francisco Serrao, who remained on Ternate until his death in 1521.

When the crews of the first Portuguese ships to visit the Spice Islands returned to Portugal, they obtained huge profits on the cloves and nutmegs they had purchased. By acquiring them directly, they had cut out all the middlemen who would have profited each time the spices changed hands on their long route to Europe. At that time merchants returning to Melaka from the Moluccas were able to sell their cloves at an almost tenfold profit. In times of scarcity, profits of one hundred and two hundred and forty times were obtained in India and Lisbon respectively.46 This profit margin was irresistible to the Portuguese and other European powers.

After the Portuguese captured Melaka in 1511 there was a short-term decline in the number of Javanese and other Asian traders coming to the Moluccas. This was a matter of concern to the Sultans as they were dependent on foreign traders to export their cloves and obtain goods and foodstuffs in return.

Portuguese squadrons visited the Moluccas in 1513 and 1518, but established no settlements. In 1521 two ships of Magellan’s Spanish expedition stopped at Tidore for six weeks. In 1522 the Portuguese returned to establish a permanent settlement. They built a fort on Ternate with the Sultan’s blessing. The Sultan expected that these new traders would interact with him in the same way as Asian traders. He did not comprehend that their intentions were to obtain a monopoly over the spice trade and proselytise Christianity.47 His perception was that the Portuguese would assist him in his local struggle for power.48

Although the Bandanese village elders resisted all attempts by the Portuguese to establish a base in their islands, they did agree in 1522 to conclude a treaty with the Portuguese government. This aimed to control the inflation in nutmeg prices resulting from the trading activities of independent rather than official Portuguese traders.49

Soon afterwards the Spanish established friendly relations with Tidore. This led to the Portuguese making a treaty with Ternate which gave the Ternatians a higher price than they received from other traders. It became a requirement that Portuguese ships had to be filled 35before other traders could be supplied with cloves. This led to a competitive struggle between the Portuguese and the Spanish and their associated Moluccan protégés.

To offset these Portuguese requirements the Spanish offered producers on Tidore and elsewhere eight times as much as the Portuguese. This was not well received by the Portuguese. Unlike the Portuguese, the Spanish had lower costs in the Moluccas as they did not maintain a permanent presence.50

Spanish–Portuguese competition for spices in the first half of the sixteenth century sent clove prices up. Asian traders continued to come for spices and the Sultan of Ternate and his notables continued to provide a large share of their cargoes.

Attempts by Portuguese government officials to stop private trading by Asians and independent Portuguese traders were unsuccessful. The Ternatians blocked such proposals by refusing to provide the Portuguese government officials with food unless they were free to sell cloves to whomsoever they wished.51

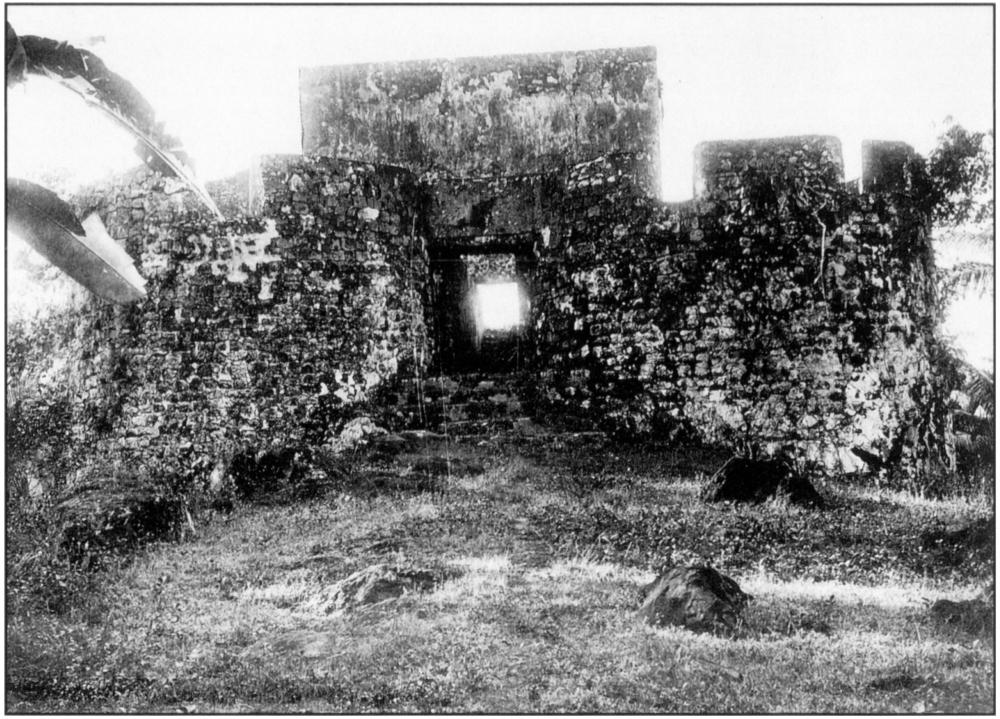

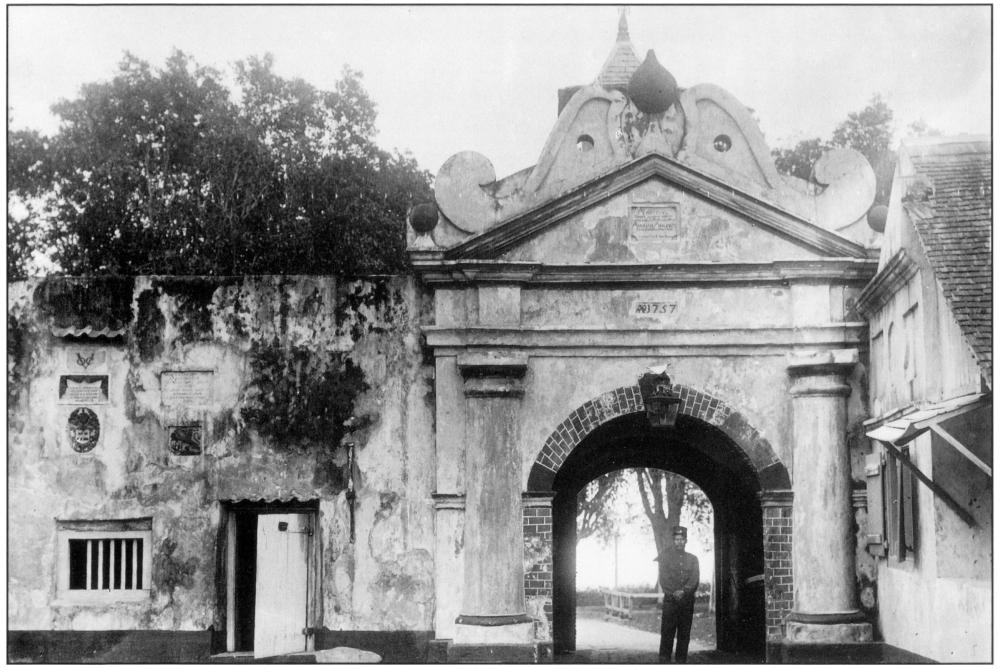

Plate 2: The ruins of the old Portuguese fort called Tololo on Ternate. It was built in the sixteenth century.

Photo: Courtesy of Fotobureau, Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, Amsterdam.

Despite the presence of Europeans and the efforts of the Portuguese to impose a monopoly, the Bandanese continued to obtain spices from the Moluccas. When Ternate came under Portuguese control they obtained their cloves from Tidore. The Portuguese soon found themselves in conflict with Tidore when they tried to examine the cargoes of Bandanese ships, as part of the enforcement of their spice monopoly.

36The increased prices offered by the Portuguese and Spanish resulted in more people tending wild stands and establishing cultivated stands. The high returns to be obtained from cloves encouraged their introduction to other islands. On Seram and Ambon they were planted where vessels stopped for water and provisions on their way to and from the Spice Islands. As with cloves, the increased prices for nutmegs resulted in people establishing new cultivated stands as well as collecting nuts from wild stands. Nutmegs were introduced to Gorong, Seram and other islands. There was no appreciation by producers that the market could not continue to grow and that over-production would ultimately produce a glut.

In addition relations between the Portuguese and the Moluccans were not turning out as each party had expected. The Portuguese established a number of bases (the ruins of one of their forts are shown in Plate 2). They also introduced changes to the Moluccan way of life and others arose because of their presence. Some of these changes were unacceptable to the Moluccans. This caused resentment and led to uprisings against the Portuguese. Between 1534 and 1574 there were three uprisings.

In 1534–5 the Moluccan sultans sought the assistance of four Papuan rajas to chase away the Portuguese. These were the raja of Vaigama (Waigama on Misool), Vaigue (Waigeo), Quibibi (Gebe) and Mincimbo (?Misool). Their resistance failed and the Papuan Islanders concerned were subjected to a Portuguese show of strength when the Portuguese Governor sent Joao Fogaço there in 1538. Fogaço returned to Ternate with a large quantity of food to supplement the limited quantities they had been able to obtain during the Moluccan resistance to Portuguese domination.52

By 1538 considerable quantities of cloves were being exported from Seram (Figure 6). The first clove trees on this island had been planted at Kambelo. The cloves produced were traded to Javanese merchants who supplied foodstuffs and cloth in return. Hitu, a Moslem trade village on Ambon, soon became the export centre. The people of Hitu and their Javanese and Bandanese allies came into conflict with the Portuguese over this clove trade in the 1550s.

In another uprising Tidore and Jailolo with Spanish assistance tried to oust the Portuguese. The Ternatian and Portuguese forces retaliated and in 1551 finally overwhelmed Jailolo. This kingdom played no further part in Moluccan affairs until 1789.

When the Portuguese murdered Sultan Hairun of Ternate in 1570, the Ternatians became determined to rid themselves of the Portuguese. 37Led by the Sultan’s son, Bab Ullah, and assisted by both Tidore and Bacan, the Moluccan forces overwhelmed the Portuguese who surrendered their fort on Ternate and withdrew to Ambon in 1574.53 This victory gave Sultan Bab Ullah great prestige and consolidated his influence in the islands between Sulawesi and New Guinea.54 Meanwhile the Portuguese concentrated their commercial activities on Ambon.55

Following an attack by Sultan Bab Ullah, Tidore invited the Portuguese to establish a military post on their island as the Spanish did not maintain a permanent presence. They saw this as a way of not only avoiding political and military domination by the Ternatians but also a means of becoming the centre of the clove trade. Although the Portuguese did establish a fort on Tidore in 1578, Ternate remained the main trading centre.56

Drake visited Ternate in 1579. He gives a glowing description of the Sultan of Ternate. The Sultan’s entourage consisted of twelve guards with lances and eight or ten notables who walked behind him. The Sultan was sheltered from the sun by a canopy embossed with gold. He wore a gold cloth laplap and a pair of red shoes. On his head was a crown formed from inch-wide plaited gold rings and around his neck there was a gold chain necklace. The fingers of his left hand wore diamond, emerald, ruby and turquoise rings, and on his right hand there was another turquoise ring as well as a ring set with many diamonds. Both Drake and his crew were impressed by the Sultan’s demeanour and wealth.57 The gold, jewels and other luxuries had been obtained in return for cloves. These spices soon attracted other Europeans to the Spice Islands.

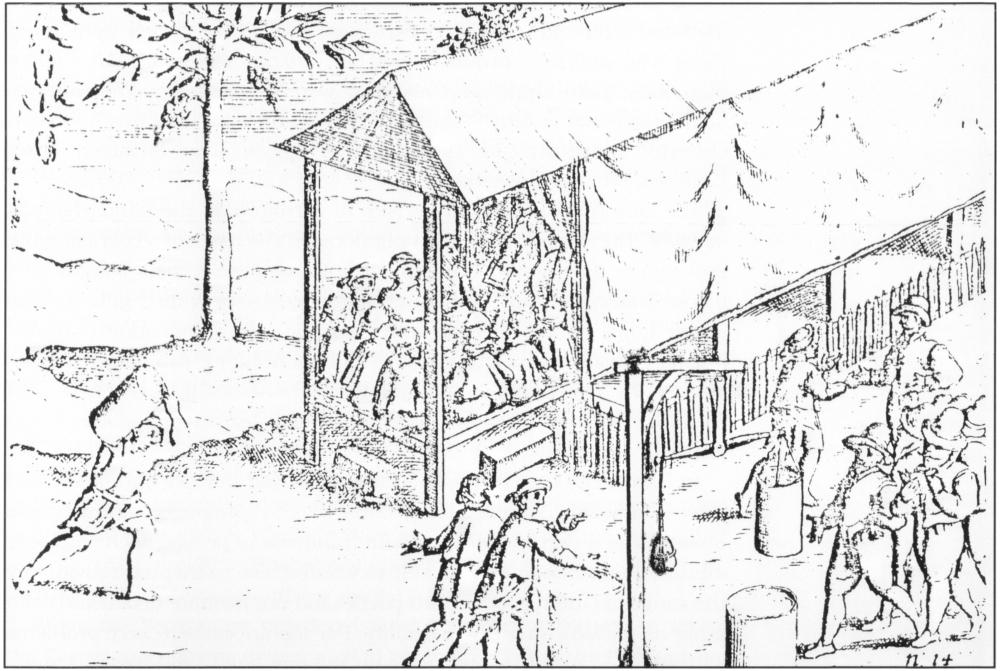

The Dutch made their first visits to Ternate and the Banda Islands in 1599. They established good relations on the basis of recognising the Portuguese as a common enemy. The Bandanese leaders sought gifts before trading began. The Dutch complied by providing gifts for the orang kaya (village elders) and fees for the sjahbandar (harbour master). Even when transactions commenced at two hired houses (Figure 7), the orang kaya had to be periodically regratified with tribute – knives, mirrors, kegs of gunpowder, crystal goblets and lengths of red velvet.

In Banda the Dutch sought locally produced nutmeg and mace, and cloves imported from Ambon. This was a prolonged and tedious business as it required dealing with hundreds of people, each with only minute quantities to sell. All sellers wanted also to inspect individually the range of Dutch goods. Both parties did not hesitate to defraud each other as regards quantity or quality. For instance, there were problems with decayed nutmegs and mace on the one hand, and rusted knives, 38broken mirrors and mildewed textiles on the other.58 This give and take did not last for long.

Relations between the Spice Islanders and Europeans from 1600 until the 1650s

By 1600 cloves, nutmeg and mace were being overproduced, with large quantities being wasted.59 The Dutch recognised that the surplus of supply over demand would in time produce a glut. They thus took steps to control production. The steps they took had tragic consequences for the people of the Spice Islands.

In 1602 some Bandanese elders signed a contract which gave the Dutch a trade monopoly in their islands. The Bandanese apparently signed this document because they feared reprisals if they refused. They were horrified when the Dutch began to enforce the agreement.60 In 1609 the Dutch occupied Neira (Figure 7) and established a fort there, despite strong resistance from the Bandanese.61

Figure 7: Sketch of the first Dutch trading post in the Banda Islands which was on Neira Island.

Source: Hana 1978:15 from Commelin 1646.

One consequence of this monopoly was that the Bandanese no longer obtained adequate supplies of rice and sago. Dutch merchants were unwilling to provide sufficient quantities, since they were interested only in more profitable, less bulky and non-perishable cargoes. To the dismay of the Bandanese, Javanese batik, Indian calicoes, Chinese porcelains and metalwares, etc., were not matched by the heavy velvets, woollens and other products manufactured in the Netherlands.62

39When the Dutch captured the Portuguese forts in the Moluccas in 1605, they did not consolidate their victory by immediately establishing a settlement. On their return in 1607 they were surprised to find that a joint Spanish–Portuguese63 fleet from Manila had recaptured one of the old Portuguese forts on Ternate. This gave the Spanish control over south and west Ternate. The Dutch then built with Ternatian help a fort (Plate 3) in east Ternate and a new Ternatian capital was established nearby. In 1608–9 Moti and Makian came under joint Dutch–Ternatian control and the Dutch established a permanent garrison on Bacan in 1609.64

Plate 3: Gate of the Dutch fort Oranje in Ternate town. The fort dates from 1607.

Photo: Courtesy of Fotobureau, Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, Amsterdam.

This military presence allowed the Dutch East India Company to enforce their policy of a spice monopoly in the Moluccas. They 40instigated a ruthless military campaign against trading vessels from other European trading countries and discouraged Asian traders.

By 1610 Luhu and Kambelo were two of many villages growing cloves on Seram (Figure 6) and clove cultivation and trade was extending eastwards on Seram to Elpaputih Bay. In the same period clove cultivation on the original five clove producing islands had dropped dramatically and by 1623 they were no longer significant suppliers of cloves.65 This was of no concern to the Dutch as the quantity of cloves grown on Ambon and Seram was double world consumption. Ambon’s harvest alone was sufficient to meet the demands of Europe and Asia.

In 1622 the Dutch realised that there was a clove glut and made greater efforts to enforce their trade monopoly. The Dutch trade monopoly brought hardship and despair to the Spice Islands. The rice or sago provided by the Dutch East India Company in exchange for cloves was expensive because Dutch transportation costs were far higher than those of Asian traders. To overcome their food shortages Ambonese and other Moluccans began to harvest local sago palms and fetch sago from distant islands, as well as grow their own rice. This did not please the Dutch East India Company. Any groups caught importing food supplies were punished by the Company, usually by cutting down their spice trees. This led to insurrections, first on Banda and then on Ambon.66

The food shortages induced by the Dutch trade monopoly led to fights and population dispersals. Men also left their settlements to avoid military service to their rulers. Conditions were so bad that infanticide was widely practised. By 1620 Bacan’s population was a fraction of its former size. This was partly because of epidemics, but also because its menfolk wished to avoid military service. In 1618 Bacan could barely raise enough men to crew two korakora with 100–200 men per vessel, whereas formerly this island could raise 6,000 able-bodied men.67

The inadequate supplies of food provided by the Dutch resulted in famine. In return for a regular supply of rice the Run Islanders in the Banda Islands (Figure 6) agreed in 1617 that the British could settle on their island.68 At the beginning of the seventeenth century the British were still endeavouring to participate in the spice trade. They had a number of factories on the shores of India, but had yet to establish fortified trading enclaves. The presence of the British on Run upset the Dutch. Efforts to enforce their supremacy in the Banda Islands resulted in the horrifying conquest of the islands by Jan Pieterszoon Coen in 1621. W.A. Hanna in his book on Banda describes the events that took place as follows:

41Coen … sent out party after party, not only on Lonthor (Great Banda) but on the other islands as well, to burn and raze the almost deserted villages and to harass the refugees wherever they may have taken shelter. Those who did surrender were frequently herded together with those who had been captured. They were then loaded onto troop transports to be shipped off to Batavia, where they were sold as slaves. One consignment totalled 883 persons (287 men, 356 women, and 240 children, of whom 176 died on shipboard). Others died by the hundreds and thousands of exposure, starvation, and disease. When forced onto the heights from which there was no escape, many leaped to their death from the sheer sea cliffs. Coen eventually shortened the period of retribution by ordering a blockade which effectively interrupted the import of vital foodstuffs and prevented the escape by sea of those who still had strength enough to seek sanctuary in distant islands. Some few Bandanese reached Ceram (Seram), Kai (Kei), and Aru, but of the original population of perhaps fifteen thousand persons, no more than a thousand seem to have survived within the archipelago, mainly on Pulau Run and Pulau Ai, where the English presence provided not active protection but some meagre deterrence to atrocities. Another 530 homesick, indigent, and troublesome Bandanese were eventually shipped back from Batavia, where thirteen of their orang kaya had been executed when implicated along with certain Javanese in an alleged conspiracy to kill Coen, burn the city, and flee to Banda.69

Asian trade with the Moluccas collapsed when Banda was captured and destroyed by the Dutch in 1621. In 1623 the Dutch captured and massacred the staff working in a British factory on Ambon. This resulted in British and other merchants withdrawing from the Spice Islands to Makassar. There the British obtained considerable quantities of cloves, often smuggled from Seram, which they traded in India to their commercial advantage.70 Some Asian traders continued to operate in clove producing areas not actively patrolled by the Dutch East India Company, but this was a risky undertaking for both traders and suppliers.

Although there were huge stocks, the price of cloves continued to rise until 1632. After this date the price went into continuous decline.71 In order to reduce production the Dutch East India Company began to destroy clove and nutmeg trees in 1647. They decided to restrict clove cultivation to Ambon and the nearby small islands of Haruku, Saparua and Nusalaut (Figure 6). Nutmegs were only permitted to be grown on the European managed plantations staffed by slaves established in the Banda Islands. The overproduction of nutmeg and mace was no longer a problem as the European planters had to follow Company policy.72 The cultivation of cloves and nutmeg outside permitted areas was forbidden, and any spice trees found were destroyed and their owners punished.73 42These restrictions gave rise to resentment and an uprising occurred when the Dutch intervened in the ascent of Sultan Mandar Syah to the throne of Ternate in 1648. The Dutch East India Company not only suppressed this uprising, but decreed in contracts with Ternate and Bacan drawn up in 1653, that cloves could not be cultivated in their territories.74 Clove growing was prohibited in Tidore in 1657. It is ironic that after 150 years of European contact the descendants of the people who had domesticated cloves were prohibited from growing them.

In 1652 a treaty granted the Dutch East India Company the right to destroy as many clove trees as it thought desirable. Nutmeg plantations and sago palms were also felled during these operations and as a result many islands became depopulated. For instance, in 1654 Buru was devastated and parts of Seram were abandoned.75

By these ruthless methods the Dutch East India Company obtained a monopoly over the spice trade, but at great expense to the people of the region and to themselves. One of the Company expenses arising from this monopoly was compensation payments to the Sultans for their loss of income. These were paid as annual subsidies, the so-called recognitiepenningen.76 The destruction by the Dutch of large numbers of established clove and nutmeg stands may also have reduced the surviving genetic diversity of these crops.77

The failure of the Dutch spice monopoly and the growing China trade

The Dutch East India Company did not make a profit on its Spice Island ventures. Their expenditure on forts and monopoly enforcement activities, such as extirpation, was greater than their profits. By 1650 their policies and activities had transformed the formerly prosperous Moluccas into an economic wilderness and instability quickly became the norm.78 Raiding and retribution became common until Dutch steam-powered ships made an impact in the 1850s.

When Asian and local trade in eastern Indonesia collapsed after the destruction of the Banda Islands in 1621, Asian and local traders in the Moluccas relocated to Magindanao on Mindanao Island. This port lay midway between the Spanish based at Manila and the Dutch at Ternate.79

Ternatians subsequently became involved in the development of Sulu either as slaves or freemen from the mid 1700s until the late 1800s. Sulu depended on a supply of slaves to maintain the workforce collecting trepang, mother-of-pearl and other products for the China trade. Captives were obtained from the Philippines as well as from 43Sulawesi and the Moluccas.80 Alfred Russel Wallace reports a Sulu raid as far south as the Aru Islands in 1857, see Chapter 9 below.

The Bandanese who had escaped to east Seram after the events of 1621 became prominent in obtaining commodities for despatch to China. Initially massoy, bird of paradise skins, pearls and damar were the main commodities obtained. After 1720 trepang became important as well.

In 1750 cloves gave only a profit of three times their cost price. This was a big difference from the huge profits obtained by the first Portuguese ships. Faced with diminishing returns, the Dutch East India Company tried to diversify its interests, while still maintaining a monopoly over the spice trade.81 The Company was not successful in either endeavour and by the 1770s it faced bankruptcy.

Despite declining profits, the British and French were keen to break the Dutch spice monopoly. Captain Thomas Forrest in 1774–76 made a voyage through the northern Moluccas and to west New Guinea on behalf of the British East India Company. He was looking for opportunities for British settlement in the area and a means of breaking the Dutch East India Company’s monopoly on the spice trade.82

Some years earlier in 1770–72 several hundred young plants had been collected from remote locations in the northern Moluccas by a French expedition. Sufficient plants survived to allow clove plantations to be established in Mauritius and Réunion. From these islands they were subsequently introduced to Zanzibar in 1818 and Madagascar in 1820. In about 1800 whilst the East Indies were under British control during the Napoleonic wars clove and nutmeg plants from the Moluccas were also established in Malaya and Sumatra.83

In 1788 the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies reported that 2.7 million kilograms of cloves were already stored at Batavia and that it was expected that 750,000 kilograms would be stored at Ambon by the end of the year. He understood there were 1.5 million kilograms stored in Holland and annual sales were only 250,000 kilograms as demand was diminishing rather than increasing.84

Spice planting in the Moluccas remained restricted until 1824 and the required delivery of cloves was not finally abolished until 1864.85 By then the clove market was dominated by non-Indonesian centres. Today the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba off the coast of Africa are the world’s largest producers of cloves and most nutmeg and mace comes from Sumatra in western Indonesia and Granada in the West Indies.86 This trade relocation brings to an end the remarkable story of the rise and decline of the spice trade in the Spice Islands.44

New roles for Tidore and Ternate

In 1660 the Sultan of Tidore signed a treaty with the Dutch East India Company which led to him playing a new role as suzerain of ‘Papua’. As time passed, and as the Dutch perceived a growing interest in New Guinea by other metropolitan powers, they increased the area designated to be under his control. The role that the Sultan of Tidore played in the political history of this region is the main topic of Chapter 6.

During the colonial period Ternate became economically important as a major plume export centre. In their search for plumes hunters and traders from Ternate and Tidore travelled vast distances within New Guinea. One of the longest documented trips is described in Chapter 11. The next chapter is concerned with when and how plumes were first traded to Southeast Asia.

Notes

1. Collins and Voorhoeve 1981.

2. Giorgio Buccellati, an archaeologist working in Terqa, a site on the middle Euphrates in Syria, claims to have recovered a handful of cloves from a partly overturned jar in a middle-class house dated to the period 1750–1600 BC (Buccellati 1983a: 54; 1983b: 19). Palaeobotanists have not confirmed that this find consists of cloves, but instead view his discovery as some unrelated species (Spriggs 1998).

3. Innes Miller 1969: 50–1.

4. About 4% of the essential oils found in both nutmeg and mace consists of the poison myristicin, so they are toxic at high levels and must be used sparingly (Cobley 1976: 245).

5. Ambary 1980:1.

6. Ellen 1979: Figure 4.

7. Muller (1990a: 18). Further information is needed on yields as an early Portuguese account claims that as much as 70 pounds (35 kilograms) was obtained from each tree after a favourable monsoon (Villiers 1990:95). Once this is clarified and the density of clove trees per hectare is known, it should be possible to assess the reliability of early harvest estimates in terms of the area of suitable clove growing land in these islands amended by observations as to the area under cultivation at the time.

8. Ellen 1979: 54.

9. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 98, 155.

10. Wit 1976: 216.

11. Wright 1958: 57.

12. Cobley 1976: 242–3: Wit 1976: 216–7.

13. Muller (1990a: 18)

14. Muller 1990a: 93.

15. Wright 1958: 57.

16. Cobley 1976: 244–5; Smith 1976: 316–7.45

17. Wright 1958:19–20; Galis 1953–4: 37.

18. van Fraassen 1981: 2.

19. Ellen 1979: 67.

20. Although the most fertile soils in Indonesia, outside Java and Bali, occur in the Minahasa region of northern Sulawesi (Babcock 1990: 189), the agricultural potential of this area did not give rise to a powerful kingdom. At the time of European contact the area was under the influence of Ternate.

21. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 97.

22. Kolff 1840: 4.

23. Forrest 1969: 23.

24. Horridge 1981: 5.

25. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 97–8.

26. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 98.

27. Stresemann 1954: 263.

28. Ellen 1979: 54.

29. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 352, footnote 78.

30. Villiers 1990: 94.

31. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 161.

32. Ellen 1979: 67.

33. Villiers 1990: 87.

34. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 96–7.

35. From the Gulf of Cambay, Gujarat, India.

36. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 99; Ellen 1979: 56–7.

37. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 83–4.

38. Warren 1981: 6–7. By comparison merchants had to pay 20 to 30 percent on the value of their cargo as duty (gifts and formal charges) in Canton, but in Melaka it was only 3 to 6 percent (Curtin 1984: 130).

39. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 96.

40. Villiers 1981: 733; Villiers 1990: 93. The obsidian from West New Britain in Papua New Guinea found in Sabah was probably traded via the so-called Brunei route (see Chapter 3).

41. Ellen 1979: 53: Ellen and Glover 1974; Schurig 1930; Solheim and Ap 1977; Solheim and Mansoben 1977; Spriggs and Miller 1979.

42. The passage between Gebe and the small island of Fau (Figure 1) was considered to be one of the best and safest anchorages in the Indonesian archipelago. It was frequently visited by whalers and ships using the eastern passage to China in order to obtain water and wood (Earl 1853:66; Kops 1852: 305). In the mid 1850s whalers visited Doreri Bay (Figure 3) once a year (Wallace 1862a: 155). Wahai on the north coast of Seram (Figure 6) was also visited by American and English whalers (Earl 1853: 56).

43. The first European to see New Guinea was Dom Jorge de Meneses, the Portuguese Governor-elect of the Moluccas in 1526. Driven eastwards from Halmahera during a voyage from Melaka to Ternate he sheltered in the Bird’s Head area. He learnt that the Moluccans called these islands ‘Ilhas dos Papuas’. This was confirmed in 1529, when a Spaniard, Alvaro de Saavedra, reports that the Moluccans called the people of New Guinea 46Papuas because they are black and have frizzled hair. He also mentions that the same name has been adopted by the Portuguese (Whittaker et al 1975: 183–4).

44. Early navigators were amazed by the similarity between the people of this large island and those of the Guinea coast of West Africa and began to call the island New Guinea. This officially dates back to when De Retes landed at the mouth of the Mamberamo River in 1545 and claimed the land for Spain naming it Nueva Guinea (Whittaker et al 1975: 186–7).

45. Galis 1953–4: 9: Miklouho-Maclay 1982: 439.

46. Villiers 1990: 93.

47. van Fraassen 1981: 3.

48. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 154.

49. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 161.

50. van Fraassen 1981: 3–4; Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 154–5.

51. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 155–7.

52. Galis 1953-4: 9.

53. van Fraassen 1981: 4.

54. As soon as the Portuguese were driven out of Ternate in 1574, the Bandanese were once again able to obtain their supplies directly from Ternate and the islands under its influence (Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 162).

55. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 160: Ellen 1979: 59.

56. van Fraassen 1981: 4.

57. Drake 1966: 91.

58. Hanna 1978: 14.

59. Ellen 1979: 67.

60. Hanna 1978: 19.

61. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 184.

62. Hanna 1978: 19.

63. The treaty of Zargossa (1529) officially ended Portuguese–Spanish conflict in the Moluccas, but problems continued until 1546. It was not until Portugal became part of the Spanish empire in 1580 that the Spanish and Portuguese collaborated in the Spice Islands (Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 155). They were finally ousted from the Spice Islands by the Dutch in 1660.

64. van Fraassen 1981: 10-11; Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 183–4.

65. Ellen 1979: 58–60.

66. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 215; Ellen 1979: 65–6.

67. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 216–7.

68. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 201.

69. Hanna 1978: 54–5.

70. Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 219–221; Ellen 1979: 65; Curtin 1984: 155.

71. Chaudhuri 1965: 169.

72. Wright 1958: 1.

73. Ellen 1979: 66; Ellen 1987: 42: Meilink-Roelofsz 1962: 218–220.

74. van Fraassen 1981: 11–12.

75. Ellen 1979: 66; 1987: 42.

76. van Fraassen 1981: 11–12.47

77. Wit 1976: 216.

78. Ellen 1979: 66.

79. Laarhoven 1990: 165–6,180.

80. Warren 1990.

81. Ellen 1979: 66.

82. Forrest 1969: van Fraassen 1981: 16–17.

83. Wit 1976: 216–7: Wright 1958: 48–9.

84. Wright 1958: 22.

85. Ellen 1979: 67

86. Cobley 1976: 241; Wit 1976: 216–7.